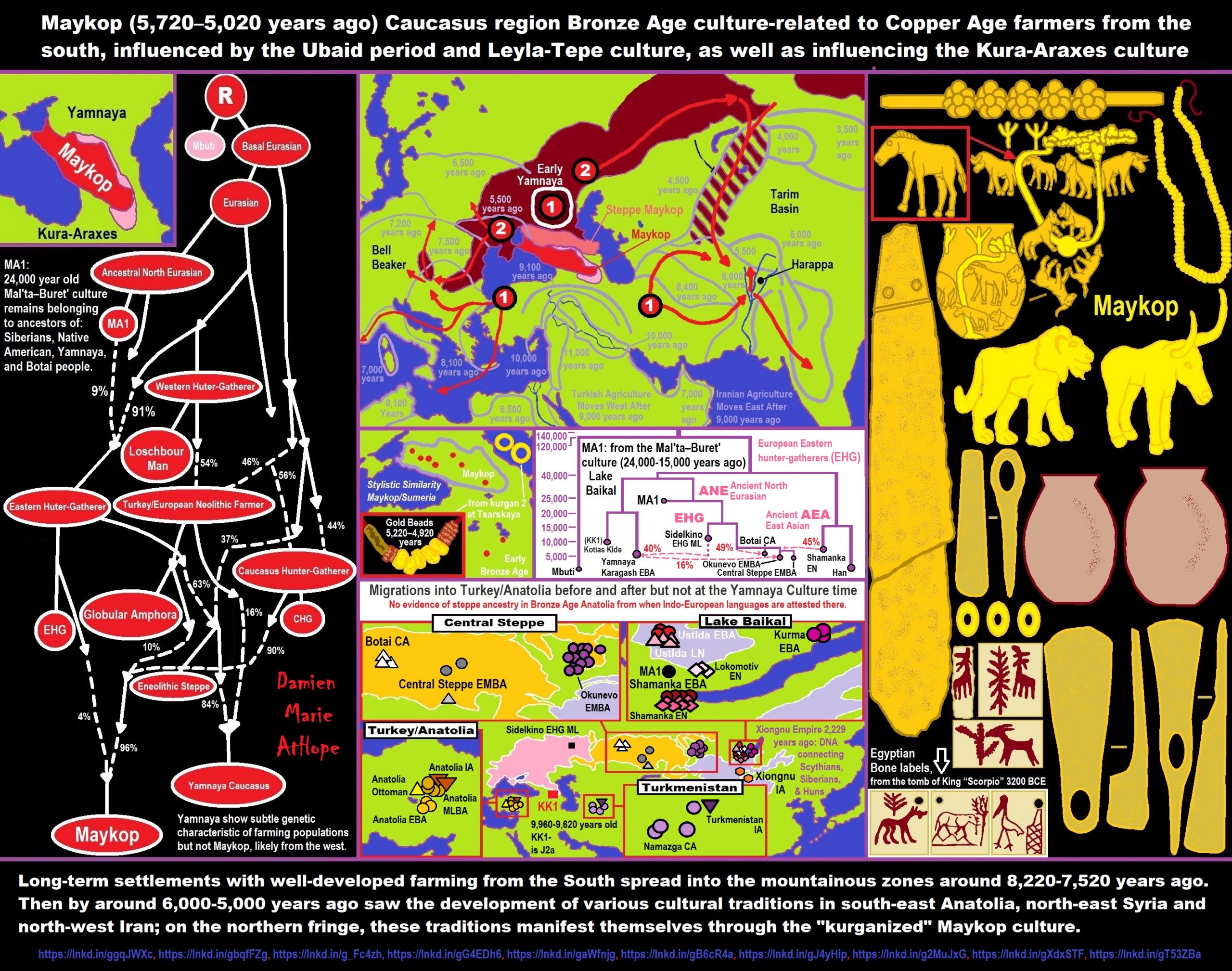

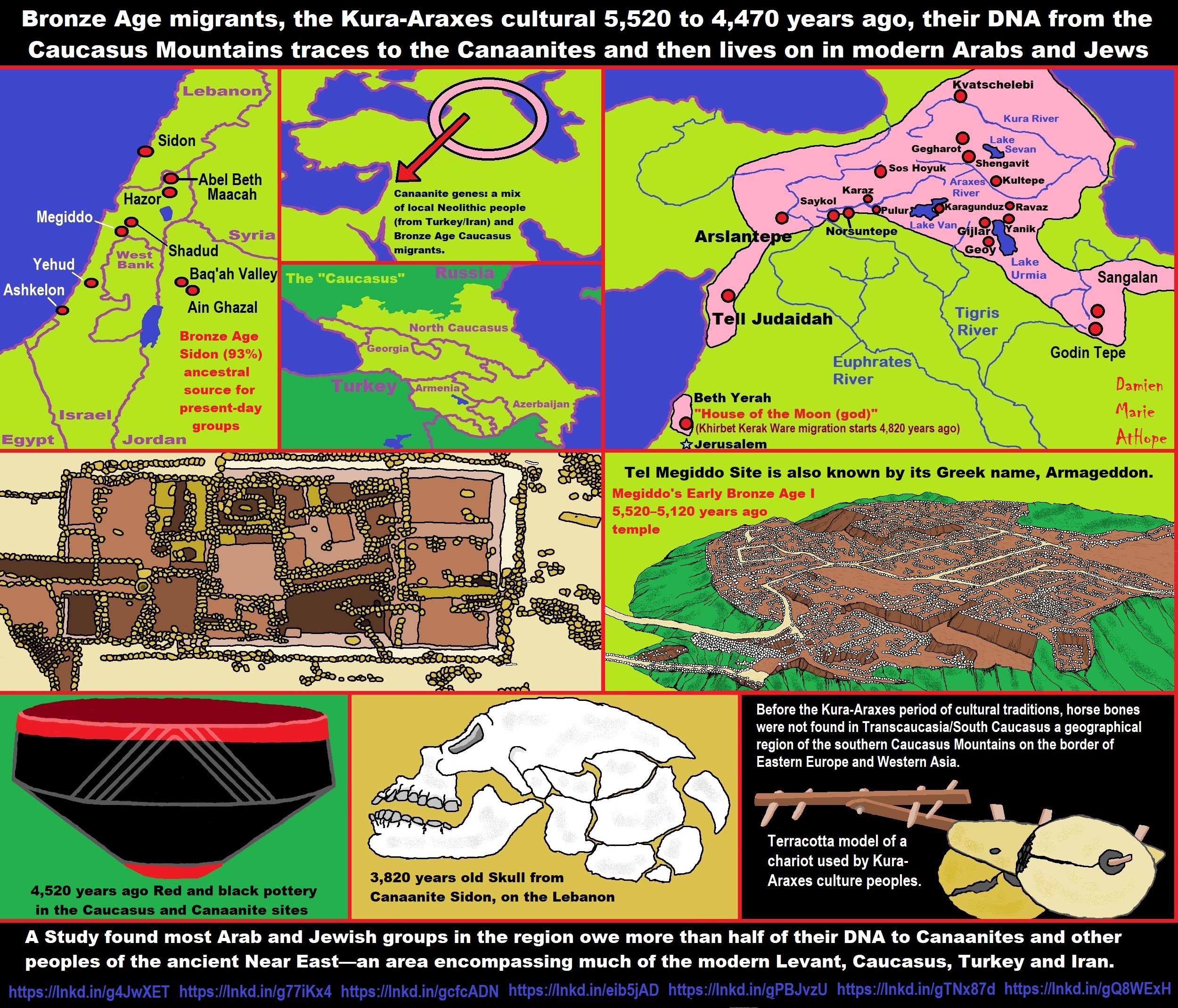

Maykop (5,720–5,020 years ago) Caucasus region Bronze Age culture-related to Copper Age farmers from the south, influenced by the Ubaid period and Leyla-Tepe culture, as well as influencing the Kura-Araxes culture. Long-term settlements with well-developed farming from the South spread into the mountainous zones around 8,220-7,520 years ago. Then by around 6,000-5,000 years ago saw the development of various cultural traditions in south-east Anatolia, north-east Syria, and north-west Iran; on the northern fringe, these traditions manifest themselves through the “kurganized” Maykop culture.

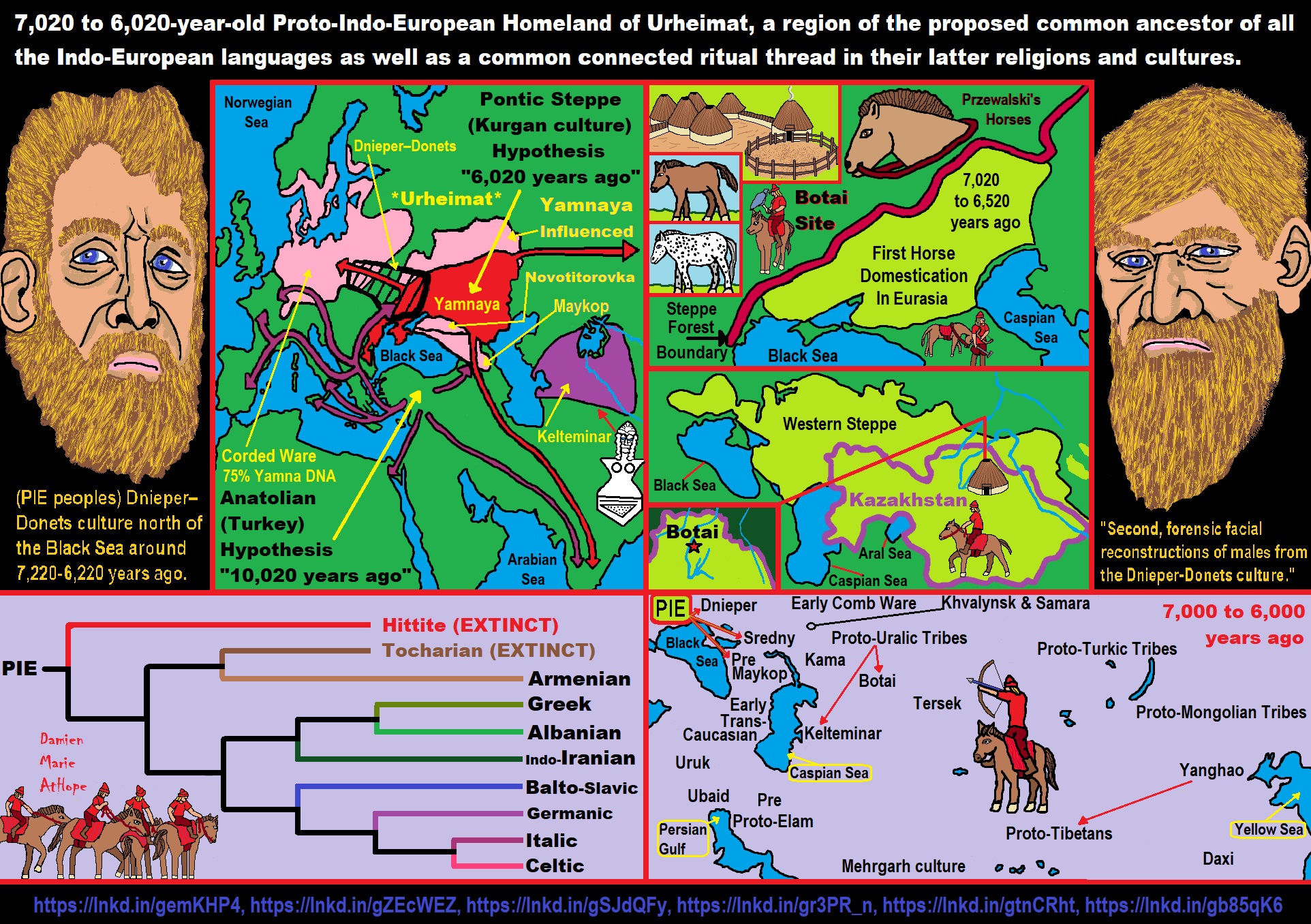

Overview of the Kurgan hypothesis:

Gimbutas’s original suggestion identifies four successive stages of the Kurgan culture:

· Kurgan I, Dnieper/Volga region, earlier half of the 4th millennium BC. Apparently evolving from cultures of the Volga basin, subgroups include the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures. ref

· Kurgan II–III, the latter half of the 4th millennium BC. Includes the Sredny Stog culture and the Maykop culture of the northern Caucasus. Stone circles, anthropomorphic stone stelae of deities. ref

· Kurgan IV or Pit Grave (Yamnaya) culture, the first half of the 3rd millennium BC, encompassing the entire steppe region from the Ural to Romania. ref

In other publications she proposes three successive “waves” of expansion:

· Wave 1, predating Kurgan I, expansion from the lower Volga to the Dnieper, leading to the coexistence of Kurgan I and the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture. Repercussions of the migrations extend as far as the Balkans and along the Danube to the Vinča culture in Serbia and Lengyel culture in Hungary. ref

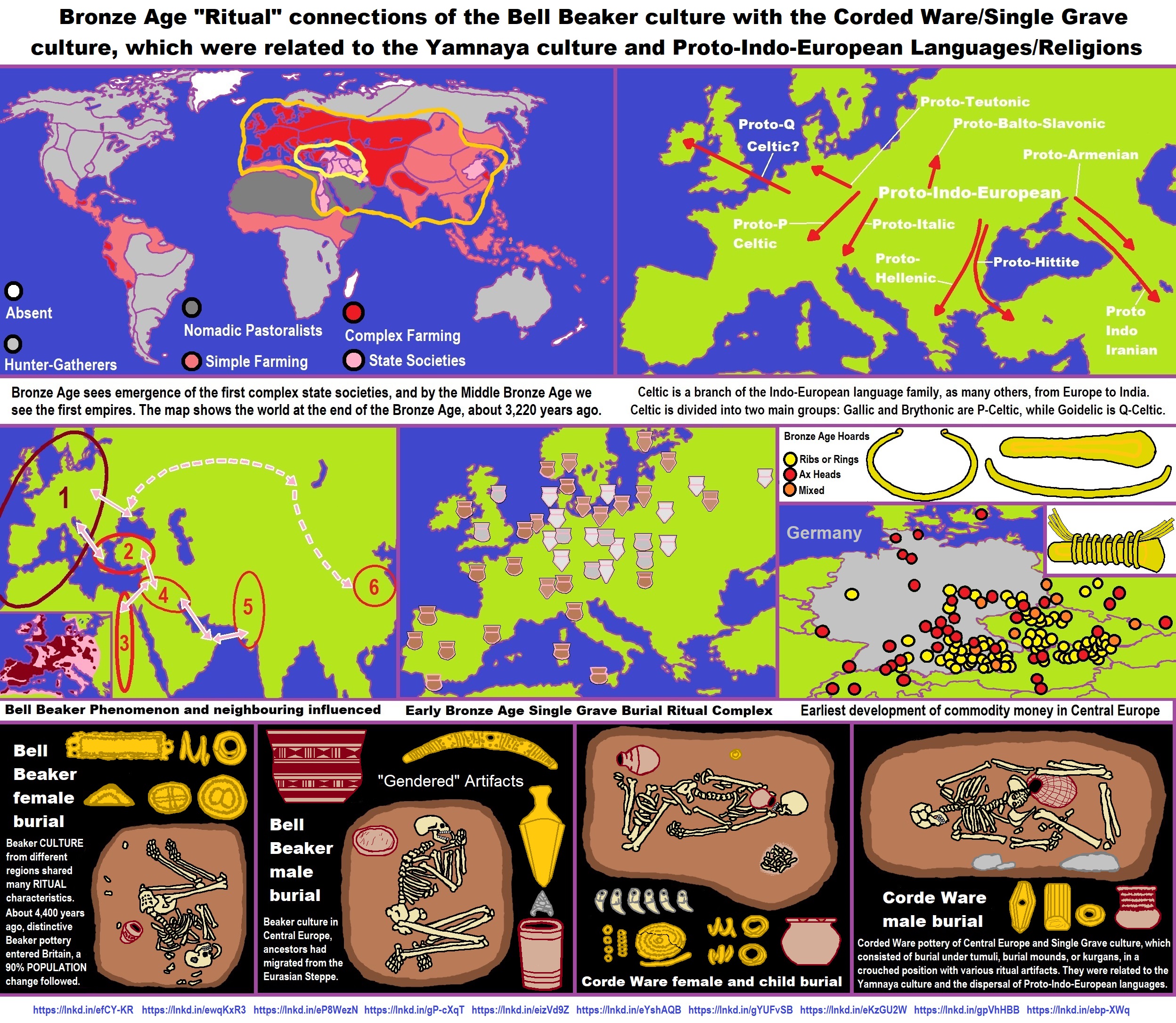

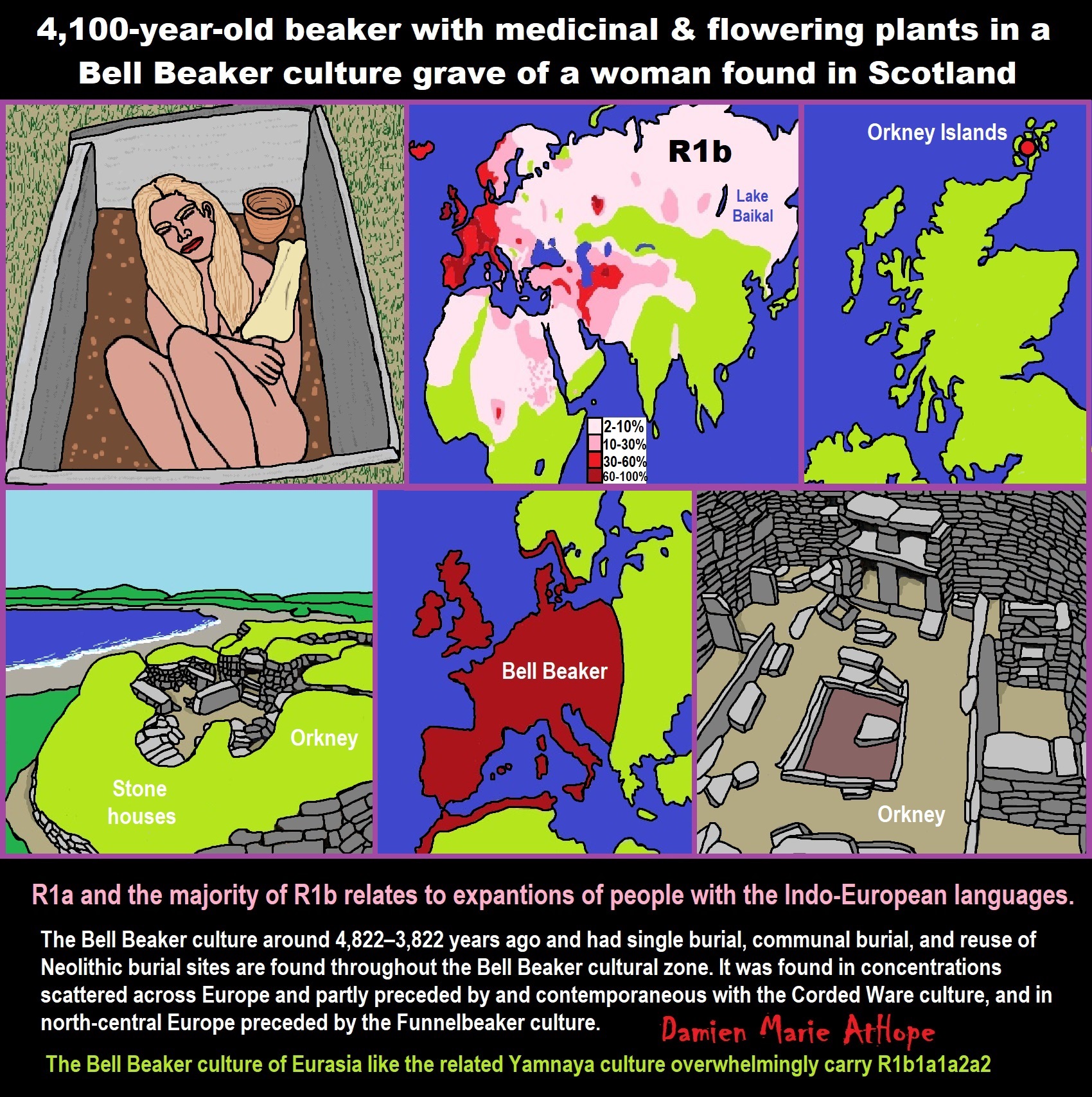

· Wave 2, mid 4th millennium BC, originating in the Maykop culture and resulting in advances of “kurganized” hybrid cultures into northern Europe around 3000 BC (Globular Amphora culture, Baden culture, and ultimately Corded Ware culture). According to Gimbutas, this corresponds to the first intrusion of Indo-European languages into western and northern Europe. ref

· Wave 3, 3000–2800 BC, expansion of the Pit Grave culture beyond the steppes, with the appearance of the characteristic pit graves as far as the areas of modern Romania, Bulgaria, eastern Hungary, and Georgia, coincident with the end of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture and Trialeti culture in Georgia (c. 2750 BC). ref

Timeline

· 4500–4000: Early PIE. Sredny Stog, Dnieper–Donets and Samara cultures, domestication of the horse (Wave 1). ref

· 4000–3500: The Pit Grave culture (a.k.a. Yamnaya culture), the prototypical kurgan builders, emerges in the steppe, and the Maykop culture in the northern Caucasus. Indo-Hittite models postulate the separation of Proto-Anatolian before this time. ref

· 3500–3000: Middle PIE. The Pit Grave culture is at its peak, representing the classical reconstructed Proto-Indo-European society with stone idols, predominantly practicing animal husbandry in permanent settlements protected by hillforts, subsisting on agriculture, and fishing along rivers. Contact of the Pit Grave culture with late Neolithic Europe cultures results in the “kurganized” Globular Amphora and Baden cultures (Wave 2). The Maykop culture shows the earliest evidence of the beginning Bronze Age, and Bronze weapons and artifacts are introduced to Pit Grave territory. Probable early Satemization. ref

· 3000–2500: Late PIE. The Pit Grave culture extends over the entire Pontic steppe (Wave 3). The Corded Ware culture extends from the Rhine to the Volga, corresponding to the latest phase of Indo-European unity, the vast “kurganized” area disintegrating into various independent languages and cultures, still in loose contact enabling the spread of technology and early loans between the groups, except for the Anatolian and Tocharian branches, which are already isolated from these processes. The centum–satem break is probably complete, but the phonetic trends of Satemization remain active. ref

Further expansion during the Bronze Age

Main article: Indo-European migrations

“The Kurgan hypothesis describes the initial spread of Proto-Indo-European during the 5th and 4th millennia BC. As used by Gimbutas, the term “kurganized” implied that the culture could have been spread by no more than small bands who imposed themselves on local people as an elite. This idea of the PIE language and its daughter-languages diffusing east and west without mass movement proved popular with archaeologists in the 1970s (the pots-not-people paradigm). The question of further Indo-Europeanization of Central and Western Europe, Central Asia, and Northern India during the Bronze Age is beyond its scope, far more uncertain than the events of the Copper Age, and subject to some controversy. The rapidly developing field of archaeogenetics and genetic genealogy since the late 1990s has not only confirmed a migratory pattern out of the Pontic Steppe at the relevant time, it also suggests the possibility that the population movement involved was more substantial than anticipated.” ref

Kurgan hypothesis Revisions:

Invasion versus diffusion scenarios

“Gimbutas believed that the expansions of the Kurgan culture were a series of essentially hostile military incursions where a new warrior culture imposed itself on the peaceful, matrilinear (hereditary through the female line), matrifocal, though egalitarian cultures of “Old Europe“, replacing it with a patriarchal warrior society, a process visible in the appearance of fortified settlements and hillforts and the graves of warrior-chieftains: The process of Indo-Europeanization was a cultural, not a physical, transformation. It must be understood as a military victory in terms of successfully imposing a new administrative system, language, and religion upon the indigenous groups. In her later life, Gimbutas increasingly emphasized the authoritarian nature of this transition from the egalitarian process of the nature/earth mother goddess (Gaia) to a patriarchal society and the worship of the father/sun/weather god (Zeus, Dyaus). This supposed egalitarian, mother-goddess-worshipping society is not the same as a matriarchy in Gimbutas’s view. Matriarchal hierarchy structures in Gimbutas’s opinion are the same as a patriarchal society, not the actual opposite: an egalitarian society without hierarchy. J. P. Mallory accepted the Kurgan hypothesis as the de facto standard theory of Indo-European origins, but he recognized criticism of any alleged, but not actually stated, “radical” scenario of military invasion; the slow accumulation of influence through coercion or extortion – Gimbutas’s actual main scenario – was often taken as general and immediate raiding and then conquest: One might at first imagine that the economy of argument involved with the Kurgan solution should oblige us to accept it outright. But critics do exist and their objections can be summarized quite simply: Almost all of the arguments for invasion and cultural transformations are far better explained without reference to Kurgan expansions, and most of the evidence so far presented is either totally contradicted by other evidence, or is the result of the gross misinterpretation of the cultural history of Eastern, Central, and Northern Europe.” ref

Alignment with the Anatolian hypothesis

Main article: Anatolian hypothesis

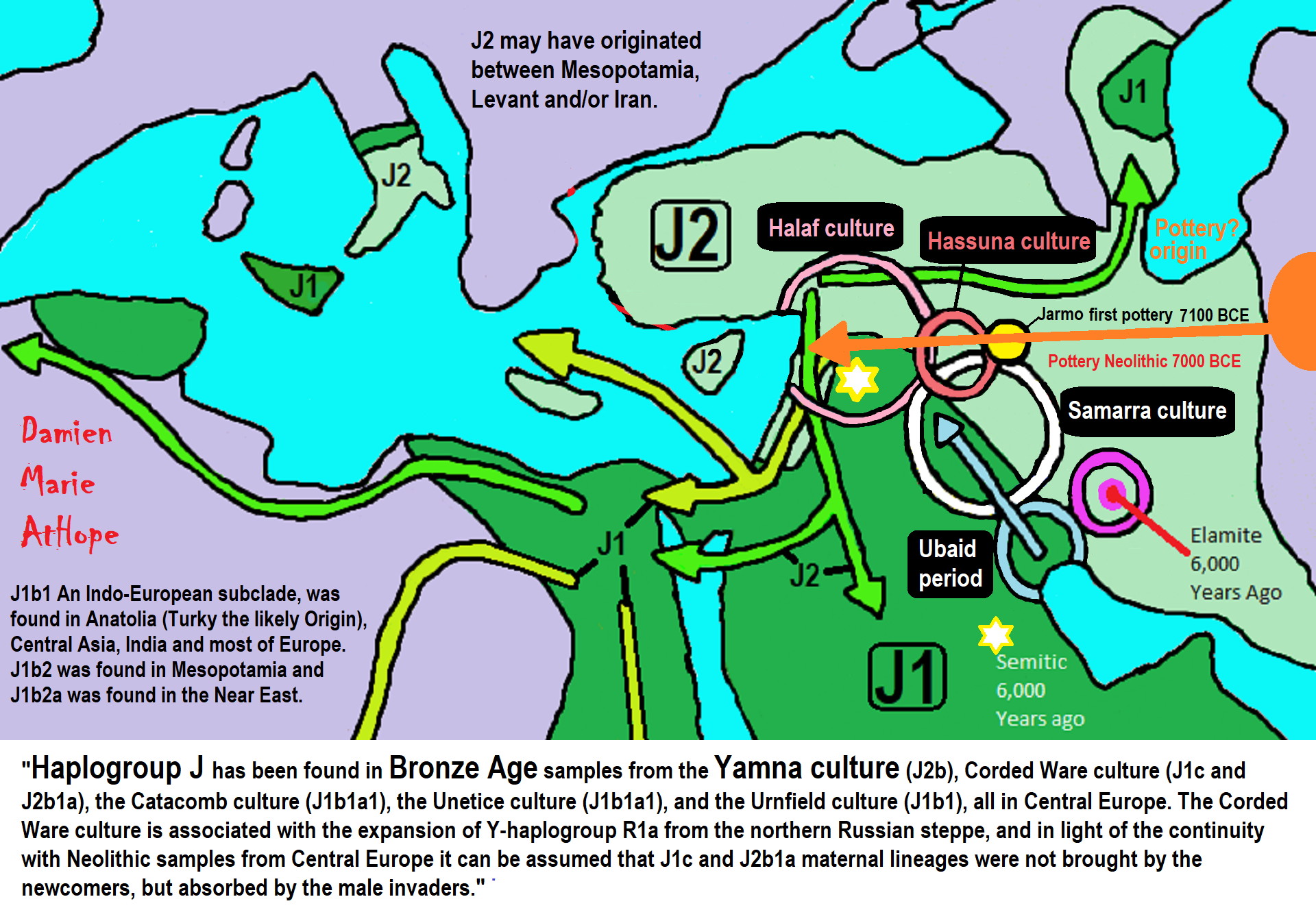

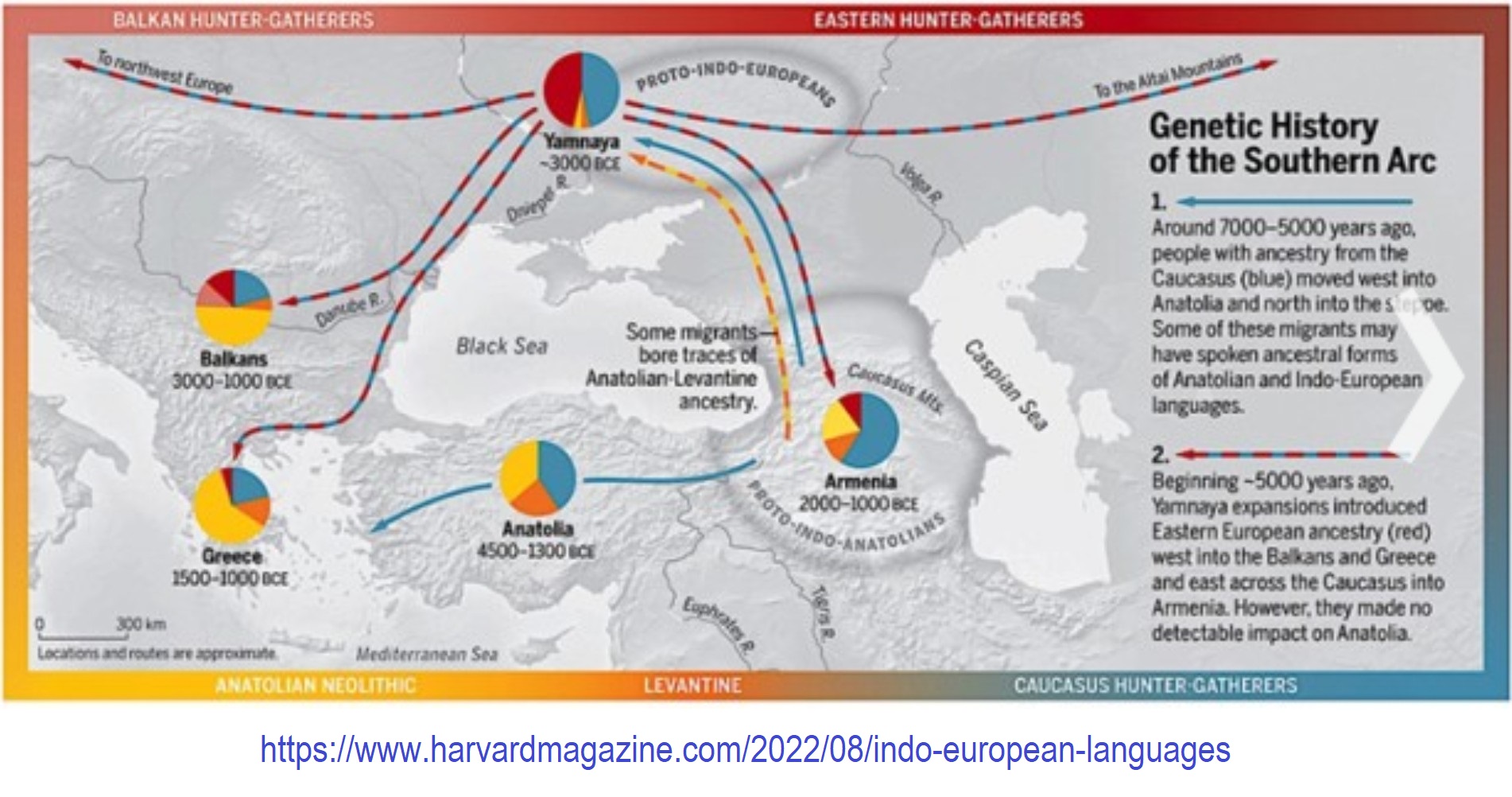

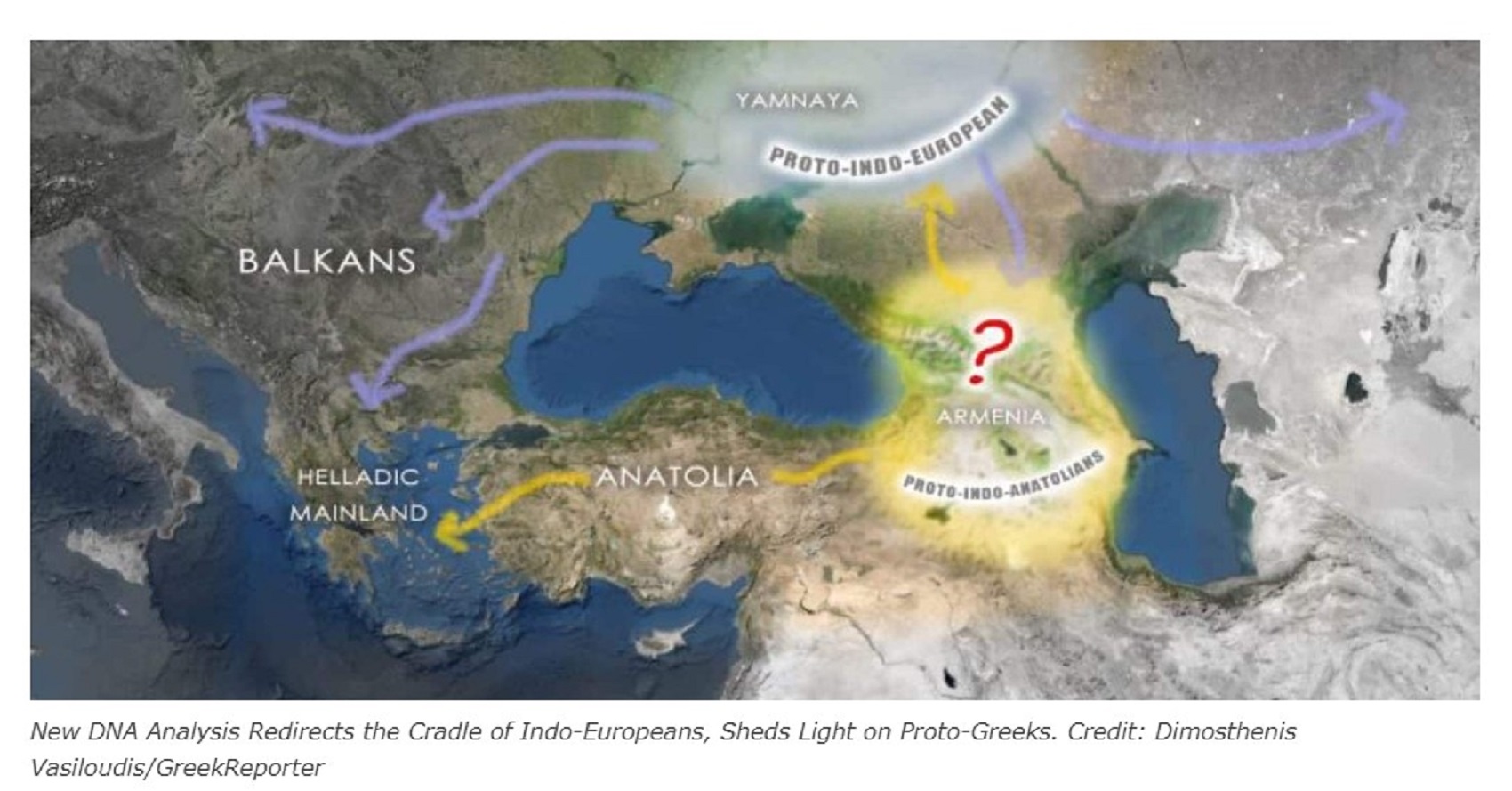

“Alberto Piazza and Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza have tried to align the Anatolian hypothesis with the steppe theory. According to Alberto Piazza, “[i]t is clear that, genetically speaking, peoples of the Kurgan steppe descended at least in part from people of the Middle Eastern Neolithic who immigrated there from Turkey.” According to Piazza and Cavalli-Sforza, the Yamna-culture may have been derived from Middle Eastern Neolithic farmers who migrated to the Pontic steppe and developed pastoral nomadism. Wells agrees with Cavalli-Sforza that there is “some genetic evidence for a migration from the Middle East.” Nevertheless, the Anatolian hypothesis is incompatible with the linguistic evidence.” ref

Anthony’s revised steppe theory

“David Anthony‘s The Horse, the Wheel and Language describes his “revised steppe theory”. David Anthony considers the term “Kurgan culture” so lacking in precision as to be useless, instead of using the core Yamnaya culture and its relationship with other cultures as a point of reference. He points out that the Kurgan culture was so broadly defined that almost any culture with burial mounds, or even (like the Baden culture) without them could be included. He does not include the Maykop culture among those that he considers to be IE-speaking, presuming instead that they spoke a Caucasian language.” ref

“The Anatolian hypothesis, also known as the Anatolian theory or the sedentary farmer theory, first developed by British archaeologist Colin Renfrew, proposes that the dispersal of Proto-Indo-Europeans originated in Neolithic Anatolia. It is the main competitor to the Kurgan hypothesis, or steppe theory, the more favored view academically. The Anatolian hypothesis suggests that the speakers of Proto-Indo-European (PIE) lived in Anatolia during the Neolithic era, and it associates the distribution of historical Indo-European languages with the expansion during the Neolithic revolution of the 7th and the 6th millennia BC. This hypothesis states that Indo-European languages began to spread peacefully, by demic diffusion, into Europe from Asia Minor from around 7000 BC with the Neolithic advance of farming (wave of advance). Accordingly, most inhabitants of Neolithic Europe would have spoken Indo-European languages, and later migrations would have replaced the Indo-European varieties with other Indo-European varieties.” ref

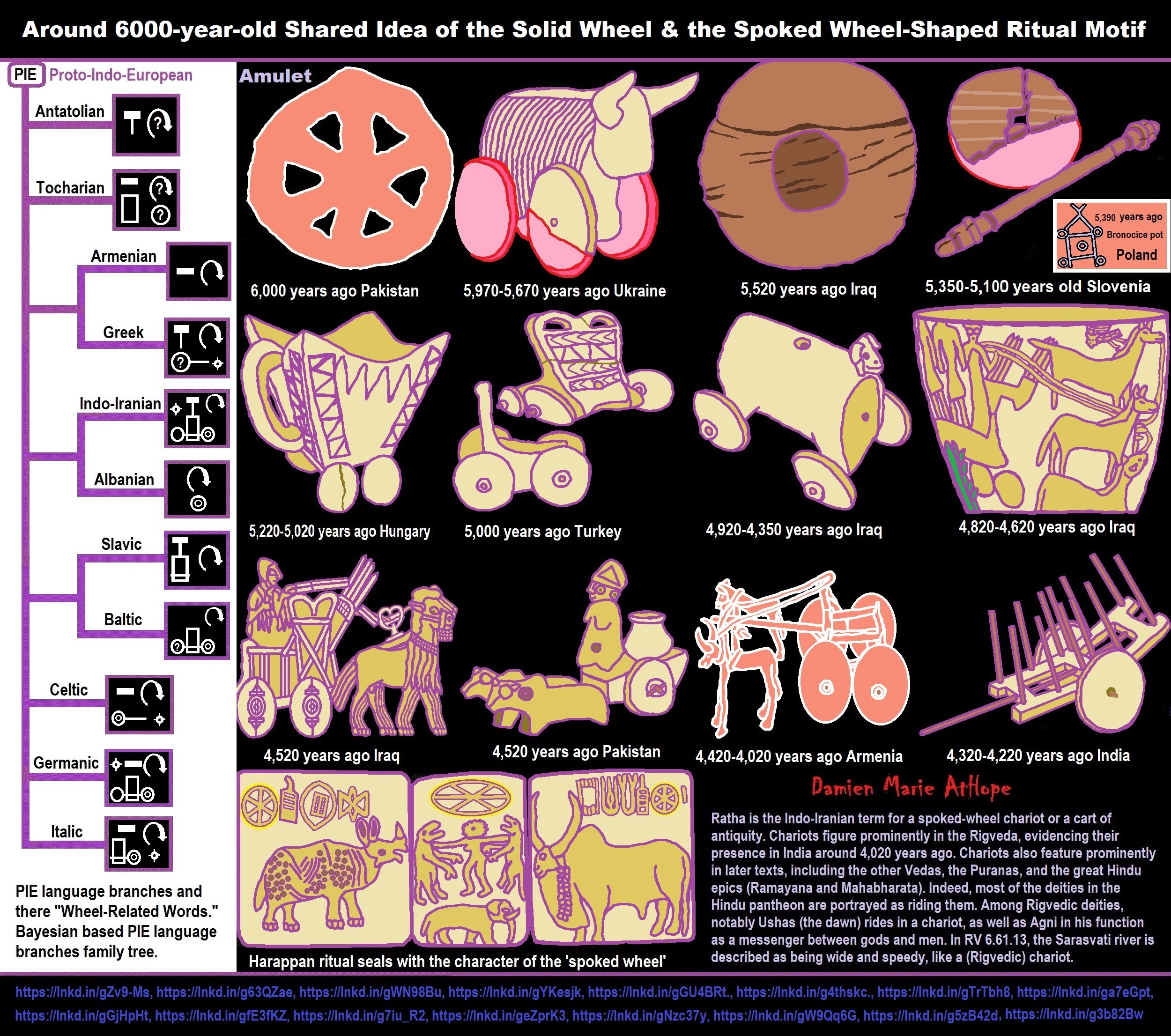

“The expansion of agriculture from the Middle East would have diffused three language families: Indo-European languages toward Europe, Dravidian languages toward Pakistan and India, and Afroasiatic languages toward the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa. Reacting to criticism, Renfrew revised his proposal to the effect of taking a pronounced Indo-Hittite position. Renfrew’s revised views place only Pre-Proto-Indo-European in the 7th millennium BC in Anatolia, proposing as the homeland of Proto-Indo-European proper the Balkans around 5000 BC, which he explicitly identified as the “Old European culture“, proposed by Marija Gimbutas. He thus still locates the original source of the Indo-European languages in Anatolia around 7000 BC. Reconstructions of a Bronze Age PIE society, based on vocabulary items like “wheel”, do not necessarily hold for the Anatolian branch, which appears to have separated at an early stage, prior to the invention of wheeled vehicles.” ref

According to Renfrew, the spread of Indo-European proceeded in the following steps:

- Around 6500 BC: Pre-Proto-Indo-European, in Anatolia, splits into Anatolian and Archaic Proto-Indo-European, the language of the Pre-Proto-Indo-European farmers who migrate to Europe in the initial farming dispersal. Archaic Proto-Indo-European languages occur in the Balkans (Starčevo–Körös culture), in the Danube valley (Linear Pottery culture), and possibly in the Bug-Dniestr area (Eastern Linear Pottery culture).

- Around 5000 BC: Archaic Proto-Indo-European splits into Northwestern Indo-European (the ancestor of Italic, Celtic, and Germanic), in the Danube valley, Balkan Proto-Indo-European (corresponding to Gimbutas’ Old European culture), and Early Steppe Proto-Indo-European (the ancestor of Tocharian). ref

“The main strength of the farming hypothesis lies in its linking of the spread of Indo-European languages with an archaeologically-known event, the spread of farming, which scholars often assume involved significant population shifts. Research of “87 languages with 2,449 lexical items” by Russell Gray and Quentin Atkinson found an age range for the “initial Indo-European divergence” of 7800 to 9800 years, which was found to be consistent with the Anatolian hypothesis. Using stochastic models to evaluate the presence or absence of different words across Indo-European, Gray & Atkinson (2003) concluded that the origin of Indo-European goes back about 8500 years, the first split being that of Hittite from the rest (Indo-Hittite hypothesis). In 2006, the authors of the paper responded to their critics, authors and S. Greenhill found that two different datasets were also consistent with their theory. An analysis by Ryder and Nicholls found support for the Anatolian hypothesis: Our main result is a unimodal posterior distribution for the age of Proto-Indo-European centered at 8400 years before Present with 95% highest posterior density interval equal to 7100–9800 years ago.” ref

“Bouckaert et al., including Gray and Atkinson, conducted a computerized phylogeographic study, using methods drawn from the modeling of the spatial diffusion of infectious diseases; it also showed strong support for the Anatolian hypothesis despite having undergone corrections and revisions. Colin Renfrew commented on this study, stating that “[f]inally we have a clear spatial picture.” A genetic study from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona favors Gimbutas’s Kurgan hypothesis over Renfrew’s Anatolian hypothesis but “does not reveal the precise origin of PIE, nor does it clarify the impact Kurgan migrations had on different parts of Europe”. Lazaridis et al. (2016) noted on the origins of Ancestral North Indians: “Nonetheless, the fact that we can reject West Eurasian population sources from Anatolia, mainland Europe, and the Levant diminishes the likelihood that these areas were sources of Indo-European (or other) languages in South Asia.” However, Lazaridis et al. previously admitted being unsure “if the steppe is the ultimate source” of the Indo-European languages and believe that more data is needed.” ref

Maykop culture (5,720–5,020 years ago)

“The Maykop culture, c. 3700 BC–3000 BC, was a major Bronze Age archaeological culture in the western Caucasus region. It extends along the area from the Taman Peninsula at the Kerch Strait to near the modern border of Dagestan and southwards to the Kura River. The culture takes its name from a royal burial found in Maykop kurgan in the Kuban River valley. According to genetic studies on ancient DNA published in 2018, the Maikop population came from the south, probably from western Georgia and Abkhazia, and was descended from the Eneolithic farmers who first colonized the north side of the Caucasus. Maykop is, therefore, the “ideal archaeological candidate for the founders of the Northwest Caucasian language family“.” ref

“In the south, the Maykop culture bordered the approximately contemporaneous Kura-Araxes culture (3500—2200 BC), which extends into the Armenian Plateau and apparently influenced it. To the north is the Yamna culture, including the Novotitorovka culture (3300—2700), which it overlaps in territorial extent. It is contemporaneous with the late Uruk period in Mesopotamia. The Kuban River is navigable for much of its length and provides an easy water-passage via the Sea of Azov to the territory of the Yamna culture, along the Don and Donets River systems. The Maykop culture was thus well-situated to exploit the trading possibilities with the central Ukraine area. Radiocarbon dates for various monuments of the Maykop culture are from 3950 – 3650 – 3610 – 2980 cal BCE. After the discovery of the Leyla-Tepe culture, some links were noted with the Maykop culture.” ref

“The Leyla-Tepe culture is a culture of archaeological interest from the Chalcolithic era. Its population was distributed on the southern slopes of the Central Caucasus (modern Azerbaijan, Agdam District), from 4350 until 4000 B.C. Similar amphora burials in the South Caucasus are found in the Western Georgian Jar-Burial Culture. The culture has also been linked to the north Ubaid period monuments, in particular, with the settlements in the Eastern Anatolia Region. The settlement is of a typical Western-Asian variety, with the dwellings packed closely together and made of mud bricks with smoke outlets. It has been suggested that the Leyla-Tepe were the founders of the Maykop culture. An expedition to Syria by the Russian Academy of Sciences revealed the similarity of the Maykop and Leyla-Tepe artifacts with those found recently while excavating the ancient city of Tel Khazneh I, from the 4th millennium BC. Nearly 200 Bronze Age sites were reported stretching over 60 miles from the Kuban River to Nalchik, at an altitude of between 4,620 feet and 7,920 feet. They were all “visibly constructed according to the same architectural plan, with an oval courtyard in the center, and connected by roads.” ref

“Maykop inhumation practices were characteristically Indo-European, typically in a pit, sometimes stone-lined, topped with a kurgan (or tumulus). Stone cairns replace kurgans in later interments. The Maykop kurgan was extremely rich in gold and silver artifacts; unusual for the time. Researchers established the existence of a local Maykop animal style in the artifacts found. This style was seen as the prototype for animal styles of later archaeological cultures: the Maykop animal style is more than a thousand years older than the Scythian, Sarmatian, and Celtic animal styles. Attributed to the Maykop culture are petroglyphs which have yet to be deciphered. The Maykop people lived sedentary lives, and horses formed a very low percentage of their livestock, which mostly consisted of pigs and cattle. Archaeologists have discovered a unique form of bronze cheek-piece, which consists of a bronze rod with a twisted loop in the middle that threads through the nodes and connects to the bridle, halter strap, and headband. Notches and bumps on the edges of the cheek-pieces were, apparently, to attach nose and under-lip straps. Some of the earliest wagon wheels in the world are found in the Maykop culture area. The two solid wooden wheels from the kurgan of Novokorsunskaya in the Kuban region have been dated to the second half of the fourth millennium.” ref

“The construction of artificial terrace complexes in the mountains is evidence of their sedentary living, high population density, and high levels of agricultural and technical skills. The terraces were built around the fourth millennium BC. and all subsequent cultures used them for agricultural purposes. The vast majority of pottery found on the terraces are from the Maykop period, the rest from the Scythian and Alan period. The Maykop terraces are among the most ancient in the world, but they are little studied. The longevity of the terraces (more than 5000 years) allows us to consider their builders’ unsurpassed engineers and craftsmen. Recent discoveries by archaeologist Alexei Rezepkin include (in his view): 1# The most ancient bronze sword on record, dating from the second or third century of the 4th millennium BC. It was found in a stone tomb near Novosvobodnaya, and is now on display in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. It has a total length of 63 cm and a hilt length of 11 cm. 2# The most ancient column. 3# The most ancient stringed instrument, resembling the modern Adyghian shichepshin, dating from the late 4th-millennium BCE.” ref

Origins?

Pontic steppe Influences

“Its burial practices resemble the burial practices described in the Kurgan hypothesis of Marija Gimbutas, which has been regarded by some as an Indo-European intrusion from the Pontic steppe into the Caucasus. However, according to J.P. Mallory, … where the evidence for barrows is found, it is precisely in regions that later demonstrate the presence of non-Indo-European populations. The culture has been described as, at the very least, a “kurganized” local culture with strong ethnic and linguistic links to the descendants of the Proto-Indo-Europeans. It has been linked to the Lower Mikhaylovka group and Kemi Oba culture, and more distantly, to the Globular Amphora and Corded Ware cultures, if only in an economic sense. Yet, according to Mallory, Such a theory, it must be emphasized, is highly speculative and controversial although there is a recognition that this culture may be a product of at least two traditions: the local steppe tradition embraced in the Novosvobodna culture and foreign elements from south of the Caucasus which can be charted through imports in both regions.” ref

Iranian Influences

“According to Mariya Ivanova, the Maikop origins were on the Iranian Plateau: Graves and settlements of the 5th millennium BC in North Caucasus attest to a material culture that was related to contemporaneous archaeological complexes in the northern and western Black Sea region. Yet it was replaced, suddenly as it seems, around the middle of the 4th millennium BC by a “high culture” whose origin is still quite unclear. This archaeological culture named after the great Maikop kurgan showed innovations in all areas which have no local archetypes and which cannot be assigned to the tradition of the Balkan-Anatolian Copper Age. The favored theory of Russian researchers is a migration from the south originating in the Syro-Anatolian area, which is often mentioned in connection with the so-called “Uruk expansion”. However, serious doubts have arisen about a connection between Maikop and the Syro-Anatolian region. The foreign objects in the North Caucasus reveal no connection to the upper reaches of the Euphrates and Tigris or to the floodplains of Mesopotamia, but rather seem to have ties to the Iranian plateau and to South Central Asia. Recent excavations in the Southwest Caspian Sea region are enabling a new perspective about the interactions between the “Orient” and Continental Europe. On the one hand, it is becoming gradually apparent that a gigantic area of interaction evolved already in the early 4th millennium BC which extended far beyond Mesopotamia; on the other hand, these findings relativise the traditional importance given to Mesopotamia, because innovations originating in Iran and Central Asia obviously spread throughout the Syro-Anatolian region independently thereof.” ref

Azerbaijan Influences

More recently, some very ancient kurgans have been discovered at Soyuqbulaq in Azerbaijan. These kurgans date to the beginning of the 4th millennium BC, and belong to Leylatepe Culture. According to the excavators of these kurgans, there are some significant parallels between Soyugbulaq kurgans and the Maikop kurgans: “Discovery of Soyugbulaq in 2004 and subsequent excavations provided substantial proof that the practice of kurgan burial was well established in the South Caucasus during the late Eneolithic/Copper Age […] The Leylatepe Culture tribes migrated to the north in the mid-fourth millennium, B.C. and played an important part in the rise of the Maikop Culture of the North Caucasus.” ref

Leyla-Tepe Culture

“The Leyla-Tepe culture of ancient Caucasian Albania belongs to the Chalcolithic era. It got its name from the site in the Agdam district of modern-day Azerbaijan. Its settlements were distributed on the southern slopes of Central Caucasus, from 4350 until 4000 B.C. Monuments of the Leyla-Tepe were first located by I. G. Narimanov, a Soviet archaeologist. Recent attention to the monuments has been inspired by the risk of their damage due to the construction of the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline and the South Caucasus pipeline.” ref

Leyla-Tepe Culture Characteristics and influences

“The Leyla-Tepe culture is also attested at Boyuk Kesik in the lower layers of this settlement. The inhabitants apparently buried their dead in ceramic vessels. Similar amphora burials in the South Caucasus are found in the Western Georgian Jar-Burial Culture, which is mostly of a much later date. The ancient Poylu II settlement was discovered in the Agstafa District of modern-day Azerbaijan during the construction of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline. The lowermost layer dates to the early fourth millennium BC, attesting a multilayer settlement of Leyla-Tepe culture. Among the sites associated with this culture, the Soyugbulag kurgans or barrows are of special importance. The excavation of these kurgans, located in Kaspi Municipality, in central Georgia, demonstrated an unexpectedly early date of such structures on the territory of Azerbaijan. They were dated to the beginning of the 4th millennium BC. The culture has also been linked to the north Ubaid period monuments, in particular, with the settlements in the Eastern Anatolia Region (Arslantepe, Coruchu-tepe, Tepechik, etc.). It has been suggested that the Leyla-Tepe were the founders of the Maykop culture. An expedition to Syria by the Russian Academy of Sciences revealed the similarity of the Maykop and Leyla-Tepe artifacts with those found recently while excavating the ancient city of Tel Khazneh I, from the 4th millennium BC. Leyla-Tepe pottery is very similar to the ‘Chaff-Faced Ware’ of northern Syria and Mesopotamia. It is especially well attested at Amuq F phase. Similar pottery is also found at Kultepe, Azerbaijan.” ref

Galayeri

“The important site of Galayeri, belonging to the Leyla-Tepe archaeological culture, was investigated. It is located in the Qabala District of Azerbaijan. Galayeri is closely connected to early civilizations of the Near East. Structures consisting of clay layers are typical; no mud-brick walls have been detected at Galayeri. Almost all findings have Eastern Anatolian Chalcolithic characteristics. The closest analogs of the Galayeri clay constructions are found at Arslantepe/Melid VII in Temple C.” ref

Leyla-Tepe Culture Metalwork

“The appearance of Leyla-Tepe tradition’s carriers in the Caucasus marked the appearance of the first local Caucasian metallurgy. This is perhaps but not entirely attributed to migrants from Uruk, arriving around 4500 BCE. Recent research indicates the connections rather to the pre-Uruk traditions, such as the late Ubaid period, and Ubaid-Uruk phases. Leyla-Tepe metalwork tradition was very sophisticated right from the beginning, and featured many bronze items. Later, the quality of metallurgy increased in both sophistication & quality with the advent of the Kura–Araxes culture.” ref

Infant Burials of the Leila-tepe Culture of the Chalcolithic Age on the Settlement Galaeri in Azerbaijan: an effort of bioarchaeological study

“A study of the Chalcolithic Leila-Tepe culture discovered in Azerbaijan gave strong evidence for Caucasian migration of ancient agriculturists from the Northern Mesopotamia starting from the end of the 5th mill. BC. Burial sites of the culture were mainly connected with infant burials in vessels inside multilayered settlements (tells). Our study was devoted to the description of three burials from excavations of the settlement Galaeri (Beta 330265: 5060±30 BP or 3940—3800 BCE). All infants were buried in vessels of the same type made of rough ceramics. Studying skeletons, we estimated biological age, as well as parameters of physical development and palaeopathological features. A digital microfocus X-ray was used. A pilot study of strontium isotopes ratio by mass-spectrometry was provided (values 0.708618—0.708785), which indicated the growth of infants in common geochemical conditions. It should be stressed that the only control sample of soil from Galaeri settlement shows a little different signal (0.709389). That means, further research of control samples could support the hypothesis of local/non-local origin of infants buried in these vessels. Two youngest infants (##3 and 6) died at 4—6 months. But their sizes were close to modern newborns. The third child, who demonstrated dental age about 4—5 years, was also retarded by 2—3,5 years. All infants from the Galaeri site showed symptoms of chronical vitamin C deficiency. The data indicates the absence of fresh fruits and vegetables in the diet of little children and their mothers.” ref

Transcaucasia

“Recent research in Transcaucasia has revealed the existence of several Late Chalcolithic, often single-period sites, characterized by “Chaff-Faced Ware” (CFW) mostly of Amuq F type. CFW was first described by the Braidwoods after their excavations in the Amuq Plain to the north of Antakya (Antioch) and was attributed to Phase F in their chronological sequence. The geographic extension of CFW is usually associated, explicitly or not, with Northern Syria and Upper Mesopotamia; it is deemed to typify the “indigenous” Late Chalcolithic faciès in contrast to “foreign” Uruk pottery assemblages. Both repertoires are indeed attested along the northern Fertile Crescent during the LC3-LC4 period, either together or on separate sites but research carried out at Arslantepe (Phase VII) over the last two decades has shown that the Amuq F horizon probably developed at an earlier date, at least from the beginning of the 4th millennium onwards, thus spanning part of theLC2 period as well. CFW has thus become one of the key elements in any discussion of the origins and mechanisms at work in the rise of early complex societies in Upper Mesopotamia and beyond, as it occurs in a context of incipient urbanisation and administrative development. Therefore, its presence, at times exclusive, on a number of settlements in the South Caucasus, especially in the Araxes or the Kura Basins, raises important questions: if the distribution of CFW is not restricted to Northwest Syria and North Mesopotamia, where is the focus of the CFW province? How and where did it originate? Not only are these issues essential to our understanding of the significance of CFW sites in Transcaucasia but they also call in question current assumptions about the broad interregional dynamics in the Near East at the time of the Uruk expansion. In a previous paper, I put forward several hypotheses suggesting that the occurrence of “Mesopotamian” sites in Transcaucasia probably indicated that the highlands were actually part of the North Mesopotamian oikoumene. After a brief presentation of the evidence from the Kura and Araxes Basins, I will now take advantage of the new data yielded by the current excavations of Ovçular Tepesi in Nakhchivan, and survey results from Eastern Anatolia, to proceed further with this analysis.” ref

DEFINITION OF THE CFW ASSEMBLAGE

“Before proceeding to any comparison between the CFW repertoire of North Syro-Mesopotamia and the pottery retrieved from Transcaucasia, it seems important to recall the main features of the CFW that has been found in the vicinity of the Fertile Crescent. This repertoire is divided into several regional assemblages, which possess common concepts and technological features in spite of morphological and sometimes decorative specificities. According to the description given by the Braidwoods, the CFW from the Amuq Plain, here called “Amuq F,” is mostly hand-made and orange-buff in color. Technologically, it is characterized by the chaff imprints left all over the vessel’s surface by the disintegration of the temper during the process of firing. The surface of most vessels is left plain, but a significant number of them bear traces of burnishing. Sometimes the vessel’s surface is covered by a thin paint or a slip, usually orange or red in color and often burnished. The paste is usually incompletely oxidized as is shown by the grey-black core visible in the break. The morphological repertoire mainly consists of wide necked-jars with short, everted collars and coarse, mass-produced bowls. The bowls may be hemispherical with simple or beaded rims, or more open without-flaring walls, also ending with simple or beaded rims.9 The jars may be angle-necked, sometimes with modeled or channeled rims, which constitute one of the hallmarks of the Amuq F repertoire. The CFW assemblage found at Arslantepe (Phase VII) appears as a somewhat richer version, in terms of diversity, of the Amuq corpus; but we must remember that the occupation levels corresponding to the Amuq F period at Arslantepe have been excavated over a much wider area (630 m2 in 2000) than any of the Amuq sites. Among the most striking pottery finds evidenced at Arslantepe that are seemingly rare in the Amuq Plain, is a wide range of “potter’s marks” occurring on different types of jars and bowls. In the earliest levels of Period VII, these bowls tend to have round, fl int-scraped bases, with the potter’s marks placed near or on the bottom; while in the later levels, the potter’s marks are usually located inside the bowls.” ref

“In fact, the variety of bowls at Arslantepe seems to be greater than in the Amuq Region or any other site: bowls may have hemispherical, out-flaring, or carinated walls with simple, beaded, hammer-head or beveled rims. While small red or orange-slipped beakers with carinated bodies, usually burnished, are seemingly specific to Arslantepe. As in the Amuq Region, the CFW assemblage at Arslantepe is rarely decorated. According to M. Frangipane, the CFW repertoire attested at Arslantepe and in the Amuq Plain is typical of Northwestern Syria, even if some of its elements may occasionally be found East of the Euphrates River.15 A second regional assemblage is more at home in the Middle Euphrates Valley and further east in the Khabur Region. It is typified by the repertoires of Kurban Höyük VI (Area C01), Hacınebi A/B1, Tell Kosaq Shamali Levels 4-3 (Sector B) as well as Tell Leilan V-IV and Tell Brak TW 19-14: this assemblage, which will be referred to henceforth as “Hacınebi A/B1,” is characterized by the so-called “casseroles,” hammerhead bowls and the presence of “grey ware.” Red-slipped ware is attested but seems much rarer than in the Amuq F repertoire. Pottery types common to the Amuq F and the Hacınebi A/B1 assemblages comprise potter’s marks, which are fairly frequent at Tell Brak, and several series of bowls without-flaring or carinated bodies, with simple or beaded rims. The potter’s marks from Brak display a range of motifs that are strikingly similar to those retrieved from Arslantepe VII. Technologically, the CFW from the Amuq and Hacınebi are also clearly akin, with similar paste colors, grey cores, and the use of chaff as the main source of temper. A third CFW assemblage illustrated by the pottery from Hammam et-Turkman V in the Balikh Region offers an intriguing case. This assemblage is divided into two main phases, Hammam VA and VB. If most of the Hammam V pottery is chaff-faced and chaff-tempered, the proportion of CFW decreases from 96,6% to 60,3% from Hammam VA to VB. According to P.M.M.G. Akkermans, however, Phase A is considered to be earlier than the Amuq F period, while morphological links are perceptible between the Hammam VB and the Amuq F repertoires. It should be stressed that the common traits between the Amuq F/Arslantepe VII and the Hammam VB assemblages usually concern rather plain, generic shapes with neither decorative nor morphological specificities. Mention should be made however of a potter’s mark attested on the outer surface of a deep bowl, which has its exact counterpart at Arslantepe VII. Red-slipped and orange burnished ware is attested in Hammam VA but seems to be absent from Phase B; in any case, carinated beakers seem to be unknown.” ref

Specific Amuq F types such as jars with channeled or modeled rims are also conspicuous by their absence. Similarly, none of the diagnostic types typical of the Hacınebi A/B1 repertoire, such as casseroles or hammer-headed bowls, are attested at Hammam VB. Interestingly enough, many of the shapes and decoration types that seem specific to Hammam VB actually come in calcite-tempered, cream, or grey-black burnished ware, which is alien to the CFW sequence. The general pattern of the Hammam VB repertoire nevertheless shows that it is no doubt related to the other CFW regional assemblages reviewed so far. The fact that the proportion of CFW only amounts to ca 60% in Phase VB could be linked to the archaeological context: it has to be kept in mind that most of Period V have been excavated only over a limited exposure (2 x 10 m). There are probably many regional assemblages waiting to be defined other than the three reviewed so far. The latter are linked by a common technological background and organizational concepts (potter’s marks), which point to specific social and economic requirements: the main concern in pottery-making during the CFW period was obviously to reduce time-consuming production processes, while artistic or symbolical expression ranked far behind. In this respect, Tepe Gawra may appear as an interesting case: this reference-site, which is located in the Upper Tigris area, stands out in the CFW horizon by its specificity. If CFW is an important component of Gawran pottery, this repertoire, unlike the corpus from Amuq F, Hammam V, or Hacınebi A/B1, is not dominated by CFW. Two other types of temper are also commonly used in the pottery production, creating different surfaces with no “chaff-faced” effect. Unfortunately, very little technological information is available for each vessel type, so that hardly any comparisons may be drawn between different productions, in particular between decorated and undecorated trends. This is all the more regrettable as, unlike other SyroMesopotamian assemblages, the Gawran repertoire is characterized by a rich variety of decoration processes.” ref

“What is more, several ceramic types that were first discovered at Tepe Gawra have attracted the attention of scholars over the years because of their far-reaching interregional comparanda. Pottery stamped with triangles and rosettes for instance, or blob-painted ware, starting respectively in Gawra XIIA and XA, have close parallels in the Upper Euphrates (Norşuntepe Phase III, Korucutepe Phase B); whereas double-mouthed jars are attested as far as Eridu (Early Uruk levels) in South Mesopotamia, the Amuq (Phase F) in the Northern Levant and Pkhagugape in the North Caucasus. At Norşuntepe and Korucutepe, most “Gawran” vessels turn up in CFW, but judging from the brief descriptions given in the pottery catalog, the technological span of similar vessels at Gawra itself seems to be more complex. At all events, it appears as if the Gawra culture stood partly outside the CFW structural system. Whatever the situation at Tepe Gawra, CFW clearly predominates over most of Upper-Mesopotamia, including the Amuq Plain and the Upper-Euphrates Basin, during the LC2-LC4 time span. Judging by its technological specificities, the spread of CFW over the Fertile Crescent suggests the development of new organization processes in the pottery production, promoting rapidity and standardization. The reasons for this reorganization are still unknown and their analysis beyond the scope of the present article. But it is all the more interesting that this system should extend as far as the South Caucasus.” ref

THE CFW IN TRANSCAUCASIA

“Ever since our first assessment of TranscaucasianMesopotamian relationships, information on the Late Chalcolithic period in the Caucasus has greatly increased with the publication of several excavation reports. These data, together with the results from the renewed excavations of Ovçular Tepesi, open new perspectives for analyzing the cultural context leading to the emergence of CFW in the South Caucasus. At least six sites yielding CFW pottery of SyroMesopotamian type have now been excavated in several parts of Transcaucasia: Berikldeebi in Georgia, Böyük Kesik, Leyla Tepe, Poylu, and Soyuq Bulaq in Azerbaijan, and Tekhut in Armenia. Apart from Tekhut, which is located in the Middle Araxes Basin near Erevan, all these sites are located in the Kura Basin. A small settlement (Alxan Tepe) characterized by Amuq F material, was also found by T. Akhundov in the Lower Araxes Basin (Mugan steppe), but this site has not been excavated yet. It is interesting to note that most of the parallels between the Transcaucasian and the Syro-Mesopotamian CFW relate to the Amuq F repertoire. The best-published evidence comes from Böyük Kesik and Leyla Tepe.” ref

“As in the North Syro-Mesopotamian assemblages, the pottery from these sites mostly comprises chaff-tempered, chaff-faced bowls and jars, pinkish or buff in color, which are described as wheel-thrown. The paste is generally fully oxidized at Leyla Tepe, but the case is different with Böyük Kesik, where many sherds are reported to have a dark core. Yellowish, pinkish, or greenish slip is said to be frequent; but cases of red slip as well as burnishing are also reported for Böyük Kesik. Just as in the Amuq, wide-necked jars with modeled or channeled rims are fairly common. Typically, all the illustrated CFW jars have a sharp inner angle at the junction between the body and the collar. Bowls without flaring walls and beaded-rims strongly recalling Arslantepe VII examples are also attested, together with a series of small carinated bowls. As the carinated bowls are not described, however, it is not clear whether these vessels are red-slipped and burnished like their Arslantepe VII counterparts. Lastly, a series of potter’s marks, some of which are strikingly similar to examples from Arslantepe VII or Tell Brak, have been found at Böyük Kesik, but also on the nearby site of Poylu, as well as in Tekhut in Armenia.” ref

“Judging by the published material, these potter’s marks are equally distributed on jars and bowls, usually on the outside surface. As in Arslantepe VII and Tell Brak, they often appear as complex motives combining impressed dots and incised lines. All examples but one have been applied on a wet paste. Apart from the CFW pottery of Amuq F type, we should also note the presence at both Leyla Tepe and Böyük Kesik of a few types that recall the Upper Tigris Region rather than the Amuq or the Malatya areas. A few “casseroles” reminiscent of North Mesopotamian assemblages have been found both at Böyük Kesik and Leyla Tepe. Curiously enough these “casseroles” are made in « céramique grossière », which is described as mostly grit-tempered, and not in CFW. Similar vessels are documented in the Middle Euphrates Basin at Kurban Höyük and Hacınebi, where they belong to the earlier part of the sequence (Hacınebi A and Kurban VI—Area C01). Two sherds, one from Böyük Kesik and the other from Leyla Tepe, obviously come from “double-mouthed” jars, a vessel type that is also attested in the Amuq F assemblage.” ref

“It is important to note in passing that the similarities between the “Leyla Tepe culture” and North Syro-Mesopotamian sites are not restricted to pottery: parallels have also been drawn between building techniques, architectural plans, stamp seals, and funerary customs. Lastly, to the wealth of information now available for Transcaucasia, we can also add some new data retrieved from the Northern Caucasus, where a series of sites belonging to the Maykop culture are described as having links with UpperMesopotamia and Anatolia. With the exception of a few seals, however, comparisons only apply to the pottery. Analogies are mostly based on shape similarities and the presence of potter’s marks. Yet, if some morphological parallels may be drawn between the Maykop pottery and a few isolated vessels from different sites of the Fertile Crescent, the Maykop repertoire as a whole does not really compare with any of the UpperMesopotamian assemblages, except possibly that from Hammam et-Turkman V. What is more, it has to be stressed that except for a series of large pithoi, most of the Maykop pottery retrieved from the Kuban Basin is neither chaff-tempered nor chaff-faced.” ref

“The Maykop assemblage thus stands outside our scope here, even if comparisons between the Maykop and the CFW repertoires may indirectly be useful for understanding cultural dynamics at an interregional level. To conclude, the CFW technological province no doubt includes Transcaucasia, but the case with the Northern Caucasus is more ambiguous. The Maykop culture is probably related to the dynamics at work south of the Caucasus range although in some way it stands outside the main cultural stream. On the other hand, close cultural links between Transcaucasia, Eastern Anatolia, and Northern Syro-Mesopotamia are evident, questioning again the processes at work in the emergence of the CFW horizon in the Fertile Crescent and beyond. Where did the CFW originate? Are we faced with the migration of North Mesopotamian groups into Transcaucasia, as suggested by a number of authors or should our interpretation of the Late Chalcolithic highland culture(s) be entirely reconsidered?” ref

INTERPRETATION THE MIGRATION HYPOTHESIS

“Ever since their discovery at the beginning of the eighties’, CFW sites in the Kura Basin have been interpreted as the result of migrations from Mesopotamia. In a famous note, I. Narimanov made comparisons between the CFW from Leyla Tepe and the evidence from Yarim Tepe III in Northern Iraq: he explained the parallels between the two assemblages by the migration of “Ubaidian tribes” into Transcaucasia, which he dated to the first half of the 4th millennium BC. This interpretation was endorsed by N. Museyibli as well as T. Akhundov, albeit with minor changes: according to Akhundov, Leyla Tepe should be dated to the second quarter of the 4th millennium, whereas he dates the foundation of Böyük Kesik and Soyuq Bulak to the third quarter of the 4th millennium. Both Akhundov and Museyibli agree that the appearance of Mesopotamian-related sites in the Kura Basin preceded the development of the “Maykop culture” in the North Caucasus: to support this hypothesis, they postulate a chronological time-lag between the foundation of Leyla Tepe sites in Transcaucasia (Berikldeebi, Böyük Kesik, and Leyla Tepe), and the appearance of Maykop sites in the North Caucasus.” ref

“However, according to Akhundov, this time-lag corresponds to two or three centuries, as he dates the Chalcolithic occupation from Maykop to the end of the 4th millennium, whereas Museyibli estimates this time-lag to be “rather short” and dates the rise of the Maykop culture just after the foundation of the Leyla Tepe and the Böyük Kesik settlements, that is to the first half of the 4th millennium. Whatever the date attributed to the Majkop culture, migration groups coming from Mesopotamia would have, according to this scenario, gradually settled the area north of the Zagros and the oriental Taurus ranges, first reaching the Kura Basin and then the North Caucasus. The idea lying behind this scenario is that “Mesopotamian” cultural elements first mingle with local traditions before moving further north, thus creating distinct cultural trends that succeed each other in time, from South to North along the Kura Basin. This scenario is interesting because it acknowledges the existence of regional specificities between different CFW assemblages, at the same time as emphasizing their similarities. But it rests on false assumptions as concerns the relative date of Berikldeebi and Böyük Kesik, which has turned out to be contemporary with or even possibly earlier than Leyla Tepe, although the latter is located further south.” ref

“Thus, the existence, as put forward by Akhundov, of a time-lag linked to migration processes between sites located up (Berikldeebi, Böyük Kesik, Soyuq Bulak) and down (Leyla Tepe) the Kura Basin seems unlikely. The scenario advocated by B. Lyonnet also postulates migrations as the main explanation for the foundation of “alien” sites such as Berikldeebi and Leyla Tepe in Caucasian land. However, feeling that the permanence of “local” features, for instance, the circular architecture attested at Tekhut and Böyük Kesik, does not fit in with the migration model, she draws a distinction between “Mesopotamian” sites, resulting from migrations and “local” sites in contact with Mesopotamian communities, on which “Mesopotamian” artifacts would be the result of interaction or exchange. This scenario, which strongly recalls the models set up for analyzing the “Uruk expansion” in later Upper Mesopotamia, rests on shaky grounds, as the definition of “local” as opposed to “alien” for the Caucasian Late Chalcolithic is even more questionable than in the Uruk case. In point of fact, these questions open onto totally different vistas if the problem is viewed from another angle: what if the close relationships observed between Transcaucasia and Upper Mesopotamia did not result from migrations from South to North but instead from cultural dynamics anchored in the North? As already pointed out in a previous article, the view that the “Amuq F culture” basically belongs to Northern Syria is probably simplistic. The Leyla Tepe assemblage, which from many points of view appears as the northern extension of the Amuq F culture, maybe both Mesopotamian-related and locally rooted in the cultural substratum. In the following sections, I will argue that the Late Chalcolithic CFW in both Transcaucasia and Upper Mesopotamia developed from a local cultural genesis; for this purpose, I would like to marshal the evidence from Ovçular Tepesi and a few East Anatolian sites.” ref

OVÇULAR TEPESI: A PRE-AMUQ F (OR PRE-LEYLA TEPE) CULTURE?

“Research carried out in the Araxes Basin over the last few years has given significant information on the period immediately preceding the Amuq F/Leyla Tepe culture. This period had so far been known mostly through a series of surveys in the region of Lake Van in Turkey and the recent excavations of Aratashen in Armenia (“Level 0”), but unfortunately, the occupation layers from Aratashen 0 being badly damaged, knowledge of this period had remained rather scanty. It is only very recently that this gap has been filled thanks to the data retrieved from Ovçular Tepesi in Nakhchivan. Work at Ovçular Tepesi has revealed an extensive Late Chalcolithic occupation extending over a natural hill for more than 1.3 ha. Two main architectural phases have been brought to light: according to a series of radiocarbon dates, they span the 4350-4000 BC period. In Upper-Mesopotamian terms, this would correspond to LC1 and the very beginnings of LC2. The first architectural phase (Phase I) is characterized by semi-subterranean huts, more or less rectangular in shape, that are usually bordered with one or two rudimentary stone walls on the slope side of the hut: these terrace walls are designed to prevent the virgin soil from crumbling into the huts. In the second phase (Phase II), the latter are replaced by multicellular, rectangular mudbrick houses sometimes built on stone foundations: most interestingly, the pottery associated with both architectural phases remains basically the same throughout the period, with only minor morphological and decorative changes.” ref

“Technologically, the Late Chalcolithic pottery from Ovçular Tepesi is all chaff-tempered and chaff-faced, often with grey to black cores resulting from brief firing. Exterior surface colors are usually beige to buff, sometimes with a cream or a red slip; in this case, the vessel’s surface is often burnished. Most of the repertoire is divided into wide-necked jars with straight or everted collars; and simple bowls with straight or out-flaring walls. A series of impressed or incised, isolated, motifs recalling potter’s marks are located inside some of the bowls: as with the potter’s marks from Arslantepe, Böyük Kesik, or Tell Brak, they were applied on a wet paste. One potsherd bears a triangular combination of dots that is typical of the Amuq F/Leyla Tepe repertoire; incidentally, its exact counterpart is also attested at Tell Brak. But the most frequent “potter’s marks” from Ovçular are formed of parallel lines, often shaped as two “V” set inside each other. It could be argued that the location of the double “V” inside the bowls and their large size precludes their function as “potter’s marks,” but in fact, this function has not been demonstrated with later examples either. In any case, is seems clear that these marks represent some kind of “sign.” ref

“To come back to the vessels: the bowls from Ovçular Tepesi, which make up some 25% of the total assemblage, show interesting characteristics that may be comparable with their later counterparts from the Amuq F horizon. Apart from the shapes, which are of course very basic, it is interesting to note the presence of a few technological traits in common with the Amuq vessels. For instance, the bowls from Ovçular Tepesi are roughly made with plain exterior surfaces that have often been smoothed with a dented tool, creating a comb-scraped effect. Sometimes this tool seems to have been a piece of wood or a flat stone, leaving scraping traces of a slightly different kind. All these techniques strongly recall the fl int-scraping treatment applied to the Coba-bowls commonly found in LC1 on North Syrian sites, but they are also akin to some of the surface treatments attested in LC2-3 along the Fertile Crescent, from the Amuq Plain to Niniveh. In short, the comb-scraping technique, which is widely used at Ovçular on bowls and jars alike, is clearly but one variation from an array of scraping techniques that are used throughout the CFW horizon from LC1 onwards. The second major component of the Ovçular assemblage are jars, 30% of the total bulk), most of which are wide-necked vessels with a short collar. Some of them (about 5% of the total bulk and 28% of the jar assemblage) are characterized by a sharp angle at the junction of the body and the collar, which heralds the characteristic angle necked jars of the Amuq F/Leyla Tepe repertoire. Lastly should be mentioned a few decorative devices shared by the Amuq F/Leyla Tepe and the Ovçular assemblages: bitumen paint, usually applied as a simple band along bowl rims, or as a festoon under the rim; as well as coarse geometric incisions or impressions, that sometimes combine series of dots and lines.” ref

Overall?

“Following the publication of considerable data relating to the Late Chalcolithic period in the Caucasus over the last few years, a number of assumptions concerning the relationships between the Caucasus and Upper Mesopotamia must now be revised. In particular, it has become clear that the various CFW sites recently discovered in the Kura or Araxes Basins should not be considered as “alien” within their Caucasian environment. They are part of a local evolution, together with other cultural components, since the settlement pattern of the highlands during the 4500-3500 BC period is characterized by cultural duality or probably even by multiculturality; a pattern which is also attested in Upper Mesopotamia during most of the 4th millennium BC. According to the present interpretation, the Amuq F/Leyla Tepe culture in the South Caucasus is indeed related to Mesopotamia but it is not a Mesopotamian culture per se. Rather, the center of gravity of this culture probably lies somewhere in the highlands between the Upper Euphrates and the Kura Rivers. The CFW cultural horizon encompasses the highlands and Upper Mesopotamia, which are thus part of the same oikou mene. However, it should be stressed that the CFW sites attested over this vast territory probably had different functions and were constituents of a complex economic system. This territory was also pervious to other cultural elements (DFBW, Late Sioni, Kuro-Araxes), which somehow interacted with the local CFW communities. The implications of this model are far-reaching: first, it puts the emergence of the first urban societies from the Tigris to the Euphrates Basins into a new perspective, as the highlands from Eastern Anatolia and the South Caucasus should now be included in the analysis of the urban development at work in Upper Mesopotamia and beyond. What is more, it follows from the above that the cultural entity that confronted the Uruk expansion from ca 3600 BC onward, was a wide and complex territory extending from the Caucasus down to the Mesopotamian lowlands. It may thus seem remarkable that very few remains clearly identifiable with the Uruk culture have been found north of the Upper Euphrates Basin. This fact may be explained by the simultaneous expansion of the Kura-Araxes cultures from the South Caucasus into Eastern Anatolia and the Levant, which, according to recent data from the excavations of Ovçular Tepesi, began as early as the end of the 5th millennium BCE. In any case, it seems clear that the demise of the CFW culture, which in each region started at a different time throughout the 4th millennium, is concurrent with the development of the Kuro-Araxes phenomenon. To sum up, the emerging picture suggests that the CFW system, whose focus was the highlands, was progressively challenged during the 4th millennium in the North as in the South, respectively by the Kuro-Araxes and the Uruk expansions. After a period of coexistence with both, the CFW culture was superseded in the highlands by the Kuro-Araxes phenomenon, whose driving forces probably had some decisive advantage over its regional neighbors: judging by the importance of metallurgy and mining activities in the Kuro-Araxes world, this advantage could be technology.” ref

North Caucasian Maykop culture (3,700–3,000 BCE) and Pontic-Caspian steppe Proto-Indo-European society

“Proto-Indo-European society is the reconstructed culture of Proto-Indo-Europeans, the ancient speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language, ancestor of all modern Indo-European languages. Archaeologist David W. Anthony and linguist Donald Ringe distinguish three different cultural stages in the evolution of the Proto-Indo-European language:

- Early (4500–4000), the common ancestor of all attested Indo-European languages, before the Anatolian split (Cernavodă culture; 4000 BCE); associated with the early Khvalynsk culture,

- Classic, or “post-Anatolian” (4000–3500), the last common ancestor of the non-Anatolian languages, including Tocharian; associated with the late Khvalynsk and Repin cultures,

- Late (3500–2500), in its dialectal period due to the spread of the Yamnaya horizon over a large area.” ref

“Proto Khvalynsk culture had domesticated cattle introduced around 4700 BCE from the Danube valley to the Volga–Ural steppes where the Early Khvalynsk culture (4900–3900 BCE) had emerged, associated by Anthony with the Early Proto-Indo-European language. Cattle and sheep were more important in ritual sacrifices than in diet, suggesting that a new set of cults and rituals had spread eastward across the Pontic-Caspian steppes, with domesticated animals at the root of the Proto-Indo-European conception of the universe. Anthony attributes the first and progressive domestication of horses, from taming to actually working with the animal, to this period. Between 4500 and 4200 BCE, copper, exotic ornamental shells, and polished stone maces were exchanged across the Pontic–Caspian steppes from Varna, in the eastern Balkans, to Khvalynsk, near the Volga river.” ref

“Around 4500 BCE, a minority of richly decorated single graves, partly enriched by imported copper items, began to appear in the steppes, contrasting with the remaining outfitted graves. The Anatolian distinctive sub-family may have emerged from a first wave of Indo-European migration into southeastern Europe around 4200–4000 BCE, coinciding with the Suvorovo–to–Cernavoda I migration, in the context of a progression of the Khvalynsk culture westwards towards the Danube area, from which had also emerged the Novodanilovka (4400–3800 BCE) and Late Sredny Stog (4000–3500 BCE) cultures.” ref

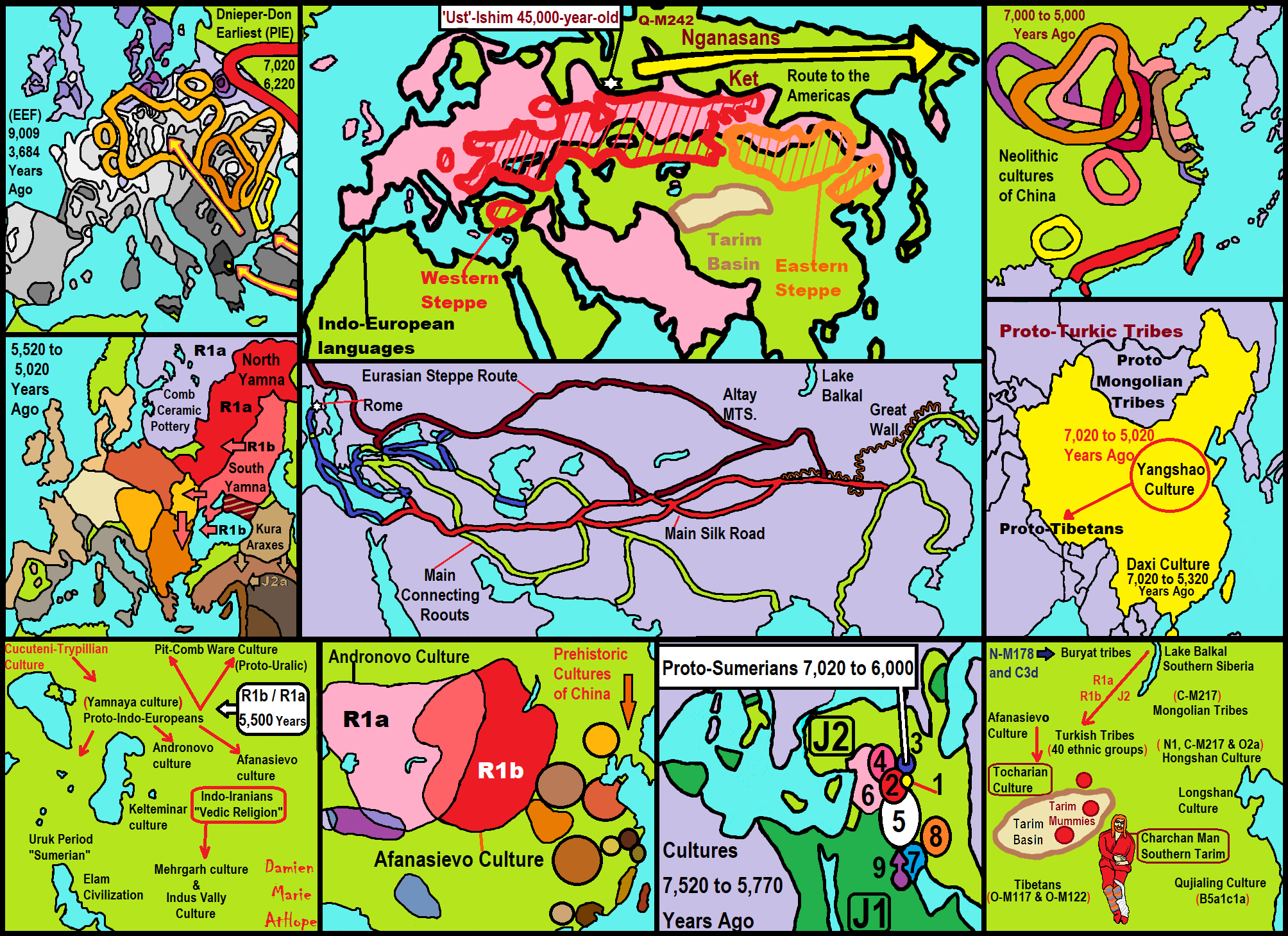

“Steppe economies underwent a revolutionary change between 4200 and 3300 BCE, in a shift from a partial reliance on herding, when domesticated animals were probably used principally as a ritual currency for public sacrifices, to a later regular dietary dependence on cattle, and either sheep or goat meat and dairy products. The Late Khvalynsk and Repin cultures (3900–3300 BCE), associated with the classic (post-Anatolian) Proto-Indo-European language, showed the first traces of cereal cultivation after 4000 BCE, in the context of a slow and partial diffusion of farming from the western parts of the steppes to the east. Around 3700–3300 BCE, a second migration wave of proto-Tocharian speakers towards South Siberia led to the emergence of the Afanasievo culture (3300–2500 BCE).” ref

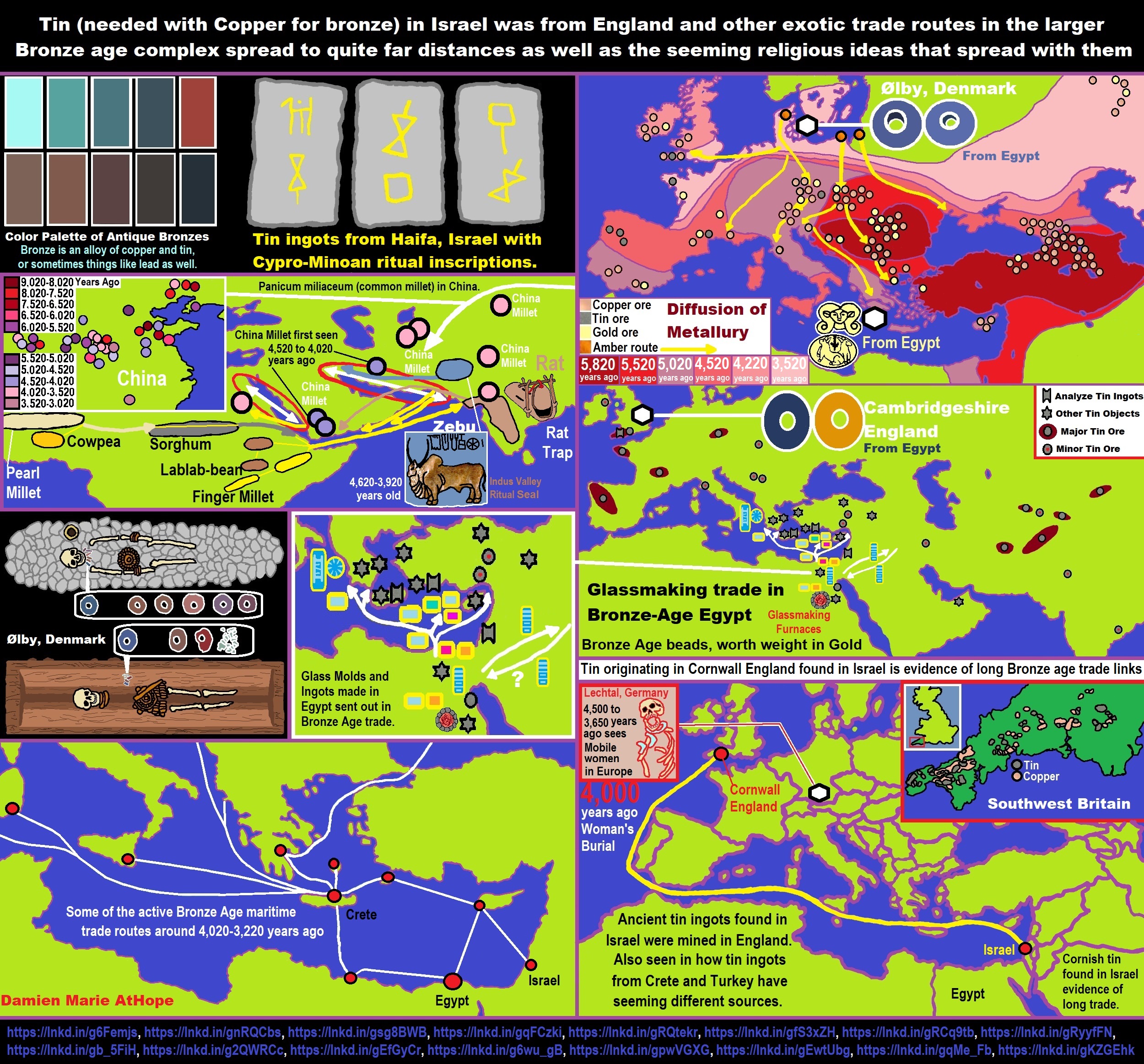

“The spoke-less wheeled wagon was introduced to the Pontic-Caspian steppe around 3500 BCE from the neighboring North Caucasian Maykop culture (3700–3000 BCE), with which Proto-Indo-Europeans traded wool and horses. Interactions with the hierarchical Maykop culture, itself influenced by the Mesopotamian Uruk culture, had notable social effects on the Proto-Indo-European way of life. Meanwhile, the Khvalynsk-influenced cultures that had emerged in the Danube-Donets region after the first migration gave way to the Cernavodă (4000–3200 BCE), Usatovo (3500–2500 BCE), Mikhaylovka (3600–3000 BCE) and Kemi Oba (3700—2200 BCE) cultures, from west to east respectively.” ref

Yamnaya period (3300–2600 BCE)

“The Yamnaya horizon, associated with the Late Proto-Indo-European language (following both the Anatolian and Tocharian splits), originated in the Don–Volga region before spreading westwards after 3300 BCE, establishing a cultural horizon founded on kurgan funerals that stretched over a vast steppic area between the Dnieper and Volga rivers. It was initially a herding-based society, with limited crop cultivation in the eastern part of the steppes, while the Dnieper–Donets region was more influenced by the agricultural Tripolye culture. Paleolinguistics likewise postulates Proto-Indo-European speakers as a semi-nomadic and pastoral population with subsidiary agriculture.” ref

“Bronze was introduced to the Pontic-Caspian steppes during this period. Following the Yamnaya expansion, long-distance trade in metals and other valuables, such as salt in the hinterlands, probably brought prestige and power to Proto-Indo-European societies. However, the native tradition of pottery making was weakly developed. The Yamnaya funeral sacrifice of wagons, carts, sheep, cattle, and horse was likely related to a cult of ancestors requiring specific rituals and prayers, a connection between language and cult that introduced the Late Proto-Indo-European language to new speakers. Yamnaya chiefdoms had institutionalized differences in prestige and power, and their society was organized along patron-client reciprocity, a mutual exchange of gifts and favors between their patrons, the gods, and human clients.” ref

“The average life expectancy was fairly high, with many individuals living to 50–60 years old. The language itself appeared as a dialect continuum during this period, meaning that neighboring dialects differed only slightly between each other, whereas distant language varieties were probably no longer mutually intelligible due to accumulated divergences over space and time. As the steppe became dryer and colder between 3500 and 3000 BCE, herds needed to be moved more frequently in order to feed them sufficiently. Yamnaya distinctive identity was thus founded on mobile pastoralism, permitted by two earlier innovations: the introduction of the wheeled wagon and the domestication of the horse. Yamnaya herders likely watched over their cattle and raided on horseback, while they drove wagons for the bulk transport of water or food. Light-framework dwellings could be easily assembled and disassembled to be transported on pack animals.” ref

“Another climate change that occurred after around 3000 BCE led to a more favorable environment allowing for grassland productivity. Yamnaya new pastoral economy then experienced a third wave of rapid demographic expansion, that time towards Central and Northern Europe. Migrations of Usatovo people towards southeastern Poland, crossing through the Old European Tripolye culture from around 3300 BCE, followed by Yamnya migrations towards the Pannonian Basin between 3100 and 2800 BCE, are interpreted by some scholars as movements of pre-Italic, pre-Celtic and pre-Germanic speakers. The Proto-Indo-European language probably ceased to be spoken after 2500 BCE as its various dialects had already evolved into non-mutually intelligible languages that began to spread across most of western Eurasia during the third wave of Indo-European migrations (3300–1500 BCE). Indo-Iranian languages were introduced to Central Asia, present-day Iran, and South Asia after 2000 BCE.” ref

Yamnaya culture and influence from the Maikop culture

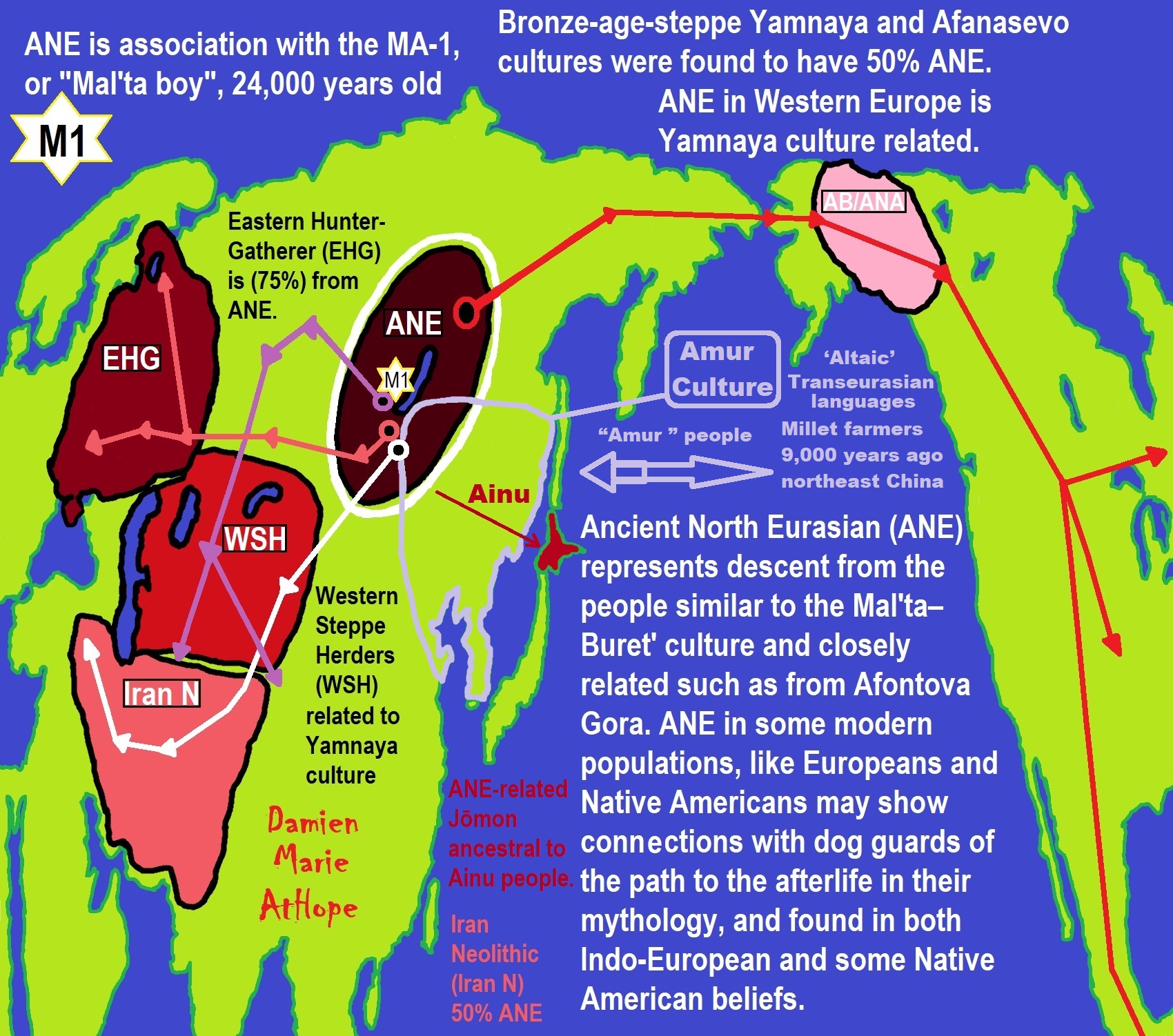

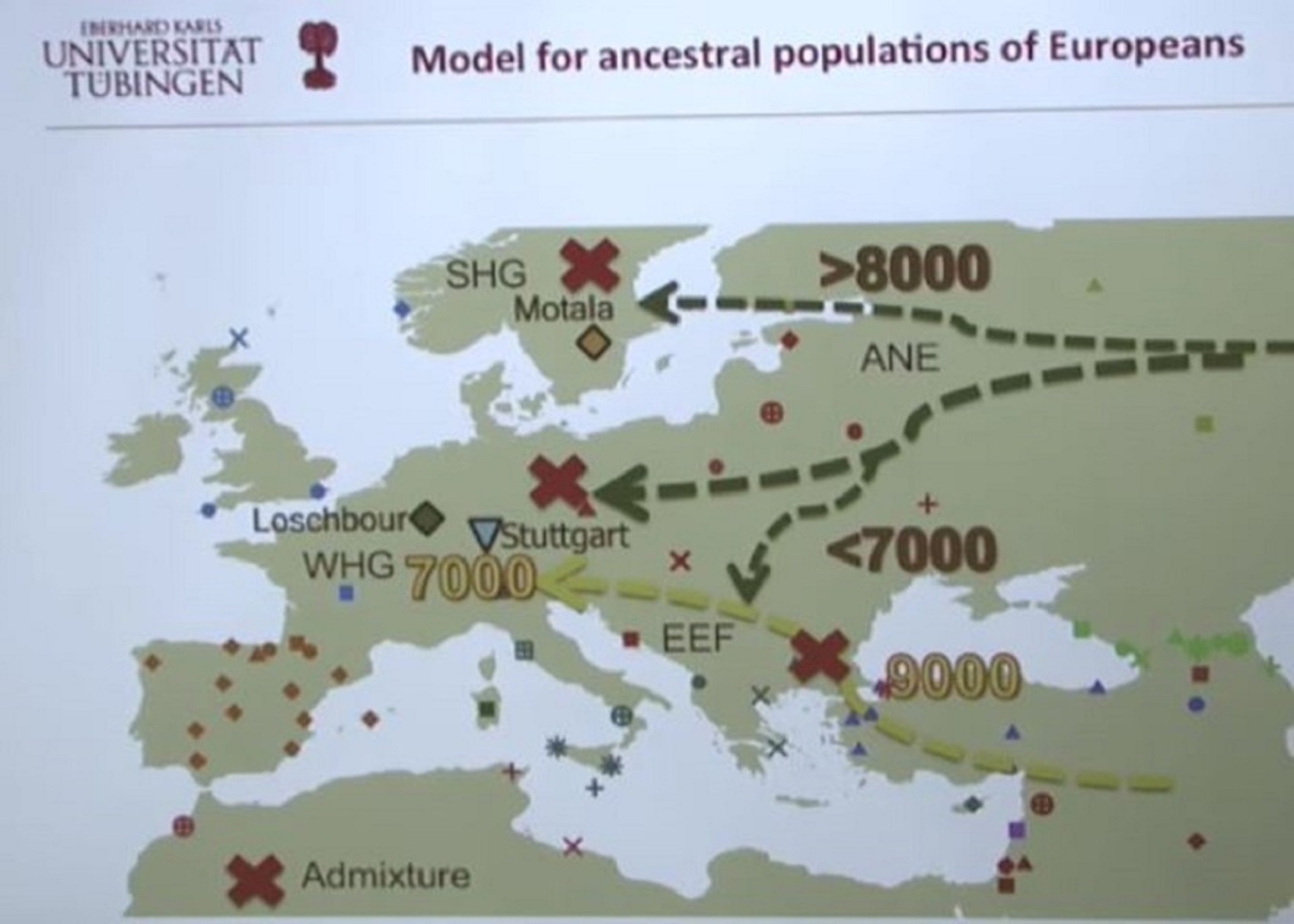

“According to Jones et al. (2015) and Haak et al. (2015), autosomal tests indicate that the Yamnaya-people were the result of admixture between “Eastern Hunter-Gatherers” from eastern Europe (EHG) and “Caucasus hunter-gatherers” (CHG). Each of those two populations contributed about half the Yamnaya DNA. According to co-author Dr. Andrea Manica of the University of Cambridge:

The question of where the Yamnaya come from has been something of a mystery up to now […] we can now answer that, as we’ve found that their genetic make-up is a mix of Eastern European hunter-gatherers and a population from this pocket of Caucasus hunter-gatherers who weathered much of the last Ice Age in apparent isolation. All Yamnaya individuals sampled by Haak et al. (2015) belonged to the Y-haplogroup R1b.” ref

“Based on these findings and by equating the people of the Yamnaya culture with the Proto-Indo-Europeans, David W. Anthony (2019) suggests that the Proto-Indo-European language formed mainly from a base of languages spoken by Eastern European hunter-gathers with influences from languages of northern Caucasus hunter-gatherers, in addition to a possible later influence from the language of the Maikop culture to the south (which is hypothesized to have belonged to the North Caucasian family) in the later neolithic or Bronze Age involving little genetic impact.” ref

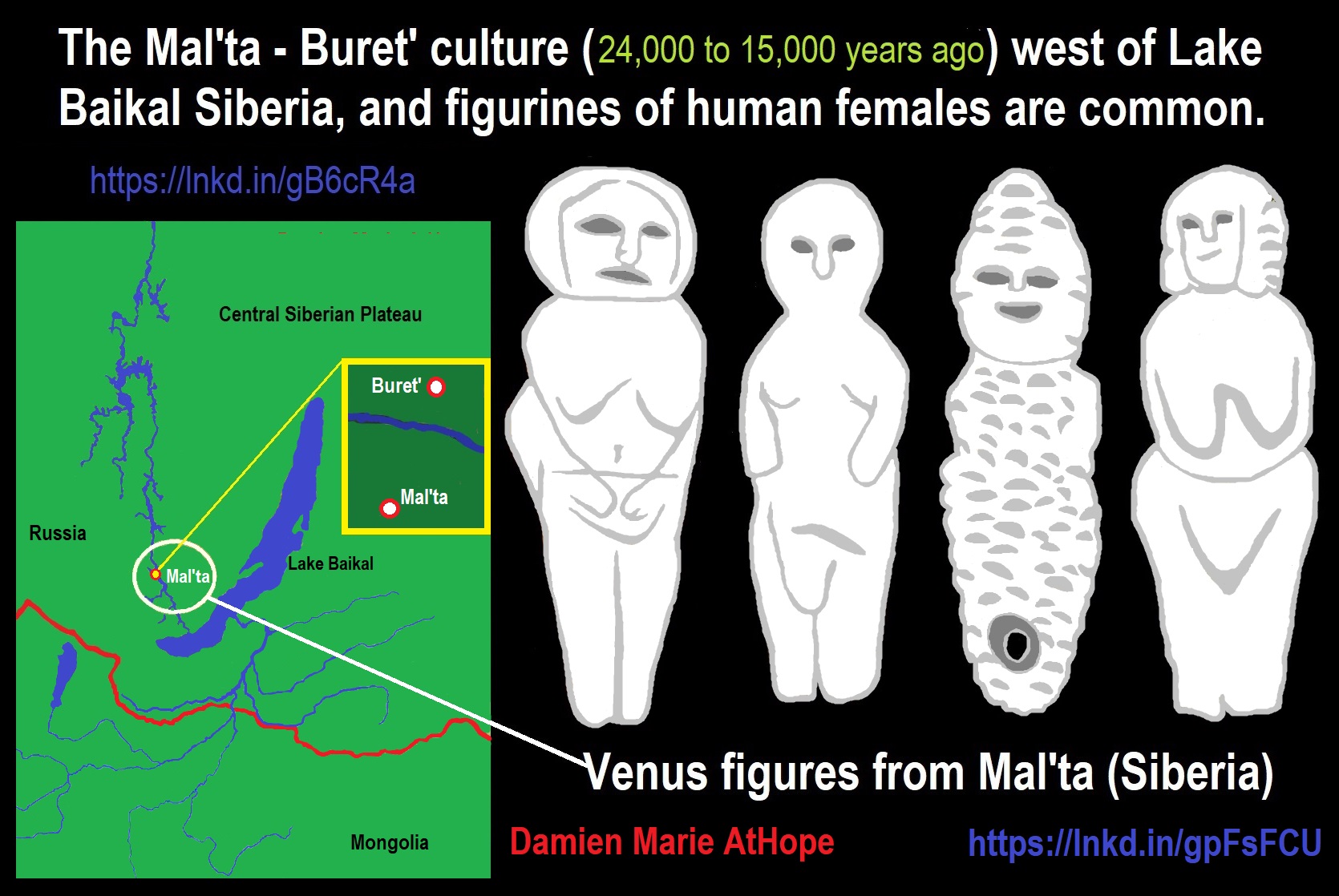

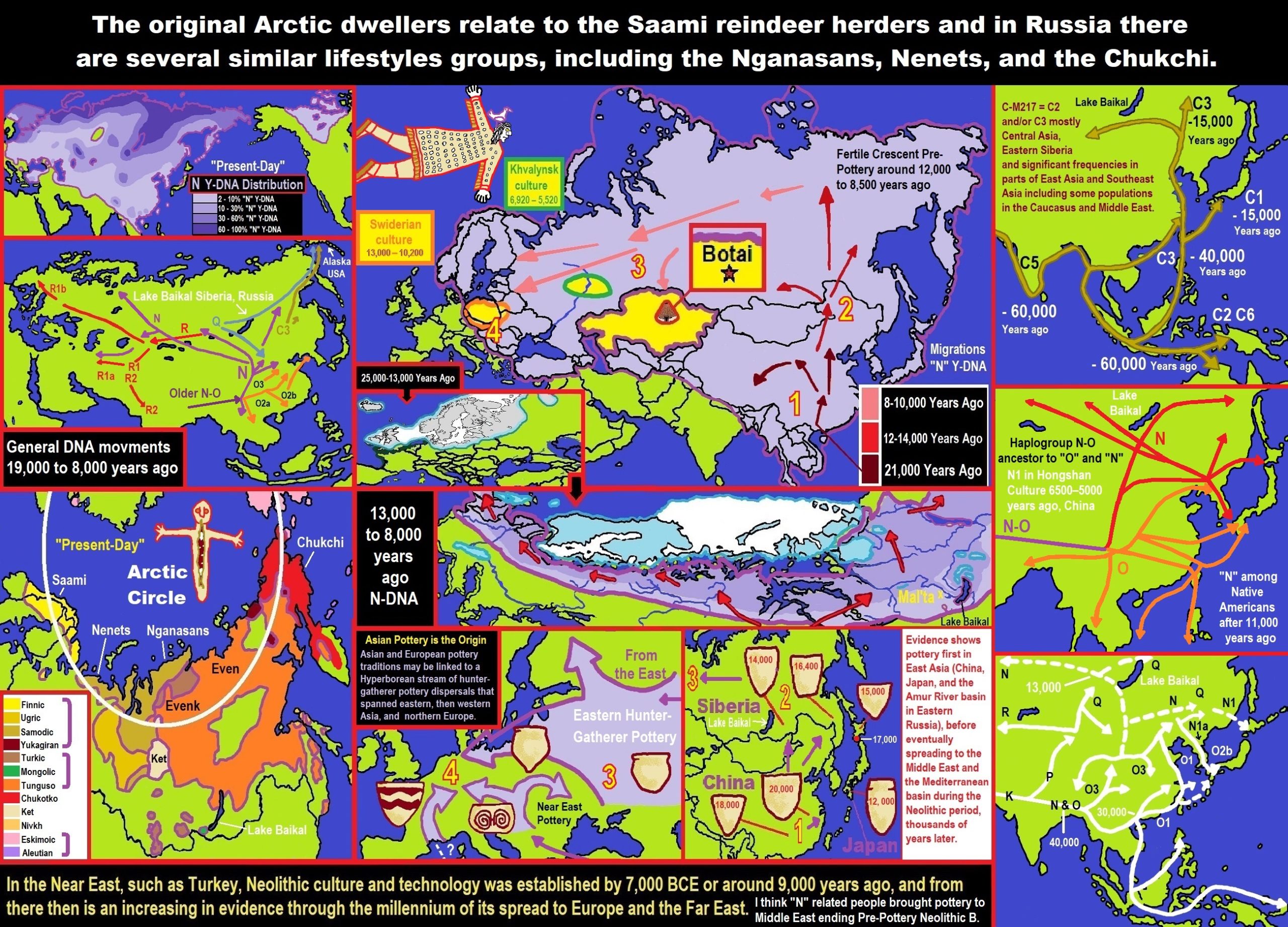

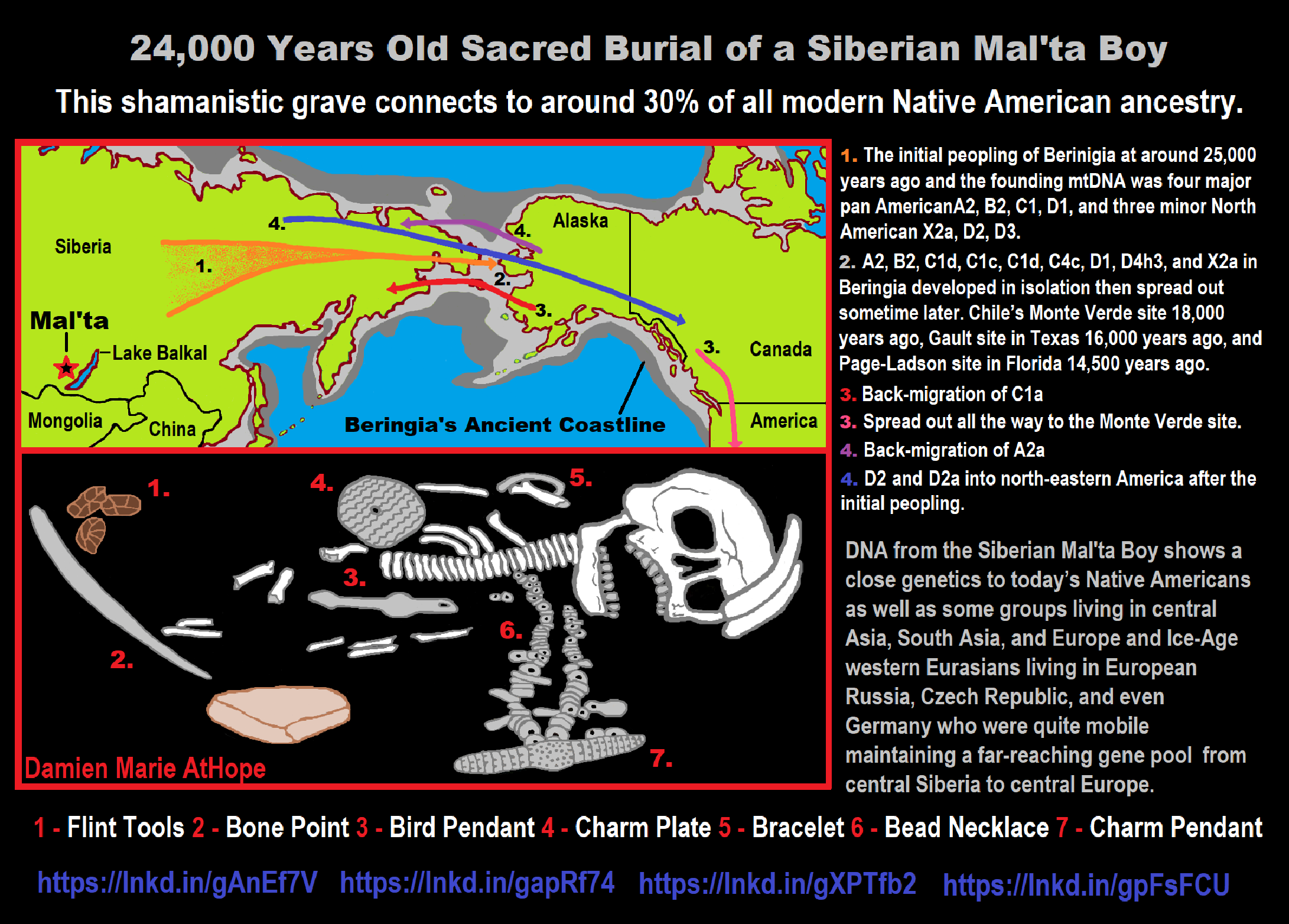

“According to Haak et al. (2015), “Eastern European hunter-gatherers” who inhabited Russia were a distinctive population of hunter-gatherers with high affinity to a ~24,000-year-old Siberian from the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture, or other, closely related Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) people from Siberia and to the Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG). Remains of the “Eastern European hunter-gatherers” have been found in Mesolithic or early Neolithic sites in Karelia and Samara Oblast, Russia, and put under analysis. Three such hunter-gathering individuals of the male sex have had their DNA results published. Each was found to belong to a different Y-DNA haplogroup: R1a, R1b, and J. R1b is also the most common Y-DNA haplogroup found among both the Yamnaya and modern-day Western Europeans. R1a is more common in Eastern Europeans and in the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent.” ref

“The Near East population were most likely hunter-gatherers from the Caucasus (CHG) c.q. Iran Chalcolithic related people with a major CHG-component. Jones et al. (2015) analyzed genomes from males from western Georgia, in the Caucasus, from the Late Upper Palaeolithic (13,300 years old) and the Mesolithic (9,700 years old). These two males carried Y-DNA haplogroup: J* and J2a. The researchers found that these Caucasus hunters were probably the source of the farmer-like DNA in the Yamnaya, as the Caucasians were distantly related to the Middle Eastern people who introduced farming in Europe. Their genomes showed that a continued mixture of the Caucasians with Middle Eastern took place up to 25,000 years ago, when the coldest period in the last Ice Age started.” ref

“According to Lazaridis et al. (2016), “a population related to the people of the Iran Chalcolithic contributed ~43% of the ancestry of early Bronze Age populations of the steppe.” According to Lazaridis et al. (2016), these Iranian Chalcolithic people were a mixture of “the Neolithic people of western Iran, the Levant, and Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers.” Lazaridis et al. (2016) also note that farming spread at two places in the Near East, namely the Levant and Iran, from where it spread, Iranian people spreading to the steppe and south Asia.” ref

Where did Late Chalcolithic Chaff-Faced Ware originate? Cultural Dynamics in Anatolia and Transcaucasia at the Dawn of Urban Civilization (ca 4500-3500 BC)

Abstract

“Following the discovery of ceramic assemblages related to “Chaff-Faced Ware” (CFW) in Transcaucasia, this article questions the origins of this ware production, which is often implicitly associated with Upper Mesopotamia and Northern Syria. After a thorough comparison of CFW assemblages attested from the Caucasus down to the Fertile Crescent, it is argued that the presence of CFW over this wide territory does not result, counter to a frequent opinion, from the migrations of Mesopotamian groups into Transcaucasia: rather, it developed from a local evolution dating back at least to 4500 BC. The territory spanned by CFW thus constitutes some kind oikoumene, whose center of gravity is probably located in the Highlands, between the Euphrates and the Kura Basins, but not in the Fertile Crescent. This analysis opens new perspectives, as the study of the processes at work in the development of the first urban societies of the Fertile Crescent should now be focussed on this oikoumene as a whole, and not only on Northern Syro-Mesopotamia, in order to understand this fundamental evolution in all its complexity. The discovery of ceramic assemblages linked to the “Chaff-Faced Ware” (CFW) at several sites in Transcaucasia, notably in the Kura basin, raises the question of the origin of this particular production, generally implicitly associated with North Syria and Upper Mesopotamia. Through a comparative morphological and technological analysis of numerous certified CFW productions from the Caucasus to the Fertile Crescent, this article demonstrates that the presence of CFW in this vast territory is not, Contrary to a frequently advanced idea, the result of migrations from Mesopotamia but rather the fruit of a local evolution, which Von can trace back at least to around 4500 BC. The territory occupied by CFW ceramics thus constitutes a form of “oikouménè”, whose center of gravity is probably located in the Highlands, between the Euphrates basin and that of the Kura, and not on the Syro-Mesopotamian rim. This new perspective makes it possible to considerably broaden the analysis of the processes leading to the emergence of the first urban societies in the Fertile Crescent, since it is the whole of this “oikouménè”, and not the only Syro-Mesopotamia of the North, which must now be taken into account in order to understand this fundamental development in all its complexity.” ref

The Caucasus: Complex interplay of genes and cultures

“In the Bronze Age, the Caucasus Mountains region was a cultural and genetic contact zone. Here, cultures that originated in Mesopotamia interacted with local hunter-gatherers, Anatolian farmers, and steppe populations from just north of the mountain ranges. Here, pastoralism was developed and technologies such as the wheeled wagon and advanced metal weapons were spread to neighboring cultures. A new study, examines new genetic evidence in concert with archaeological evidence to paint a more complete picture of the region. An international research team, coordinated by the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (MPI-SHH) and the Eurasia Department of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) in Berlin, is the first to carry out systematic genetic investigations in the Caucasus region. The study, published in Nature Communications, is based on analyses of genome-wide data from 45 individuals in the steppe and mountainous areas of the North Caucasus. The skeletal remains, which are between 6,500 and 3,500 years old, show that the groups living throughout the Caucasus region were genetically similar, despite the harsh mountain terrain, but that there was a sharp genetic boundary to the adjacent steppe areas in the north.” ref

“The Caucasus, an area that today includes parts of Russia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, Iran, and Turkey, is a crucial intersection for the history of Europe, both genetically and culturally. Today it is one of the regions of the world with the highest linguistic diversity, and in the past, populations from the Caucasus were instrumental in shaping the genetic components of today’s Europeans. During the Bronze Age, important technological innovations, developed in the Caucasus and beyond, were transported to Europe through this region, such as the first highly effective metal weapons and the wheel and wagon. Researchers assume that in the wake of the Neolithic period, sometime before 5,000 BC when a more sedentary lifestyle with domesticated animals and plants was established, populations from the southern Caucasus spread over the mountains to the north and there met with nomadic populations from the Eurasian steppe,” says Dr. Wolfgang Haak, group leader for molecular anthropology at the MPI-SHH and leader of the study. “The genetic boundary corresponds in principle to the ecological and geographical regions: the mountains and the steppe. Today, on the other hand, the Caucasus mountains themselves are more of a barrier to gene flow. Over the centuries, an interaction zone was formed, where the traditions of the Mesopotamian civilization and those of the Caucasus met with the cultures of the steppe. This intertwining is evident in the cultural exchange and transfer of technological and social innovations, as well as the occasional exchange of genes, which the study shows also took place between groups of quite distinct genetic backgrounds.” ref

Cultural contact zone, the genetic border region

“The skeletal remains studied come from different Bronze Age cultures. The Maykop culture in particular, based on its spectacular grave goods, which had close parallels in the south, was long regarded as a population that had migrated to the North Caucasus from Mesopotamia. The current paleogenetic study paints a more nuanced picture of mobility during the Bronze Age. People with a distinct southern Caucasus ancestry were already north of the mountain ridges by the 5th millennium BC. It is highly likely that these groups formed the basis for the local Early Bronze Age Maykop culture of the 4th millennium BC. Intriguingly, the Maykop individuals tested are genetically distinct from the groups in the adjacent steppes to the north. The genetic results do not support scenarios of large-scale migrations from the south during the Maykop period, or even from the northwest, as was postulated by some archaeologists. These findings have major implications for our understanding of the local development of North Caucasus cultures in the 4th millennium BC,” explains Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Svend Hansen, Director of the DAI’s Eurasia-Department. By the 3rd millennium BC, pastoralist groups from the steppe were bringing about a fundamental change in the population of Europe. The current study confirms parallel changes in the Caucasus along the southern border of the steppe zone. “During the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC, however, the people living in the Northern Caucasus all shared a similar genetic makeup even though they can be recognized (archaeologically) as different cultural groups,” says Sabine Reinhold, co-director of the archaeological team. “Individuals belonging to Yamnaya or Catacomb cultural complexes, according to archaeological analyses of their graves, are genetically indistinguishable from individuals from the North Caucasian culture in the foothills and in the mountains. Local or global cultural attributions were apparently more important than common biological roots.” ref

Subtle gene flow from the west contributed to the formation of early Yamnaya groups

The massive population shifts in the 3rd millennium BC, in connection with the expansion of the groups from the steppe who were part of what is known as the Yamnaya culture, have long been associated with the transfer of significant technological innovations from Mesopotamia to Europe. Recent studies at the DAI’s Eurasia department on the spread of early wagons or metal weapons have shown, however, that an intensive exchange between Europe, the Caucasus, and Mesopotamia began much earlier. However, can evidence of these technological exchanges also be provided by the genetic interactions revealed in the current study? And if so, in which direction do they point? The genomes of the Yamnaya individuals from the steppe bordering the Caucasus indeed show subtle genetic traces that are also characteristic of the neighboring farming populations of south-eastern Europe. Detailed analysis now shows that this subtle gene flow cannot be linked to the Maykop population, but must have come from the west.” ref

“These are exciting and surprising findings, which highlight the complexity of the processes that lead to the formation of Bronze Age steppe pastoralists,” says Chuan-Chao Wang, population geneticist postdoc at the MPI-SHH and first author of the study, now a professor at Xiamen University in China. Hansen adds, “These subtle genetic traces from the west are indeed remarkable and suggest contact between people in the steppes and western groups, such as the Globular Amphora culture, between the 4th and the 3rd millennium BC.” It appears that the world of the 4th millennium BC was well-connected long before the major expansion of steppe pastoralists and related groups. In this wide-ranging network of contacts, people not only spread and exchanged know-how and technological innovations, but occasionally also exchanged genes, and not only in one direction. Indeed, individuals from the north-eastern dry steppes of the North Caucasus region show genetic traces that hint at a deep and far-reaching connection to people in Siberia, Northeast Asia, and the Americas. “This shows that Eurasia was the site of many exciting chapters in human prehistory that are still shrouded in mystery. Our aim is to investigate these in close collaboration with archaeologists and anthropologists,” says Prof. Johannes Krause, Director of the MPI Archaeogenetics Department and co-leader of the study.” ref

The Production of Thin‐Walled Jointless Gold Beads from the Maykop Culture Megalithic Tomb of the Early Bronze Age at Tsarskaya in the North Caucasus: Results of Analytical and Experimental Research

Abstract

“This study, the first of this kind, reconstructs the technical chaîne operatoire of thin‐walled jointless gold bead production in the Maykop culture on the basis of trace‐wear analysis, experimental research and comparative analysis, using gold beads from the Early Bronze Age dolmen (c. 3200–2900 bc) in kurgan 2 at Tsarskaya (discovered in 1898). The results of the study demonstrate that such beads were produced from a perforated disc‐shaped blank by pressure (with intermittent annealing) within a hemispherical depression in a shaping block (presumably made from stone or bone) and subsequent abrasive treatment of the surface. Most probably, this technique was a regional expression of Near Eastern jewelry traditions that emerged within the urbanized centers of Upper Mesopotamia in the early fourth-millennium bc and spread out, through the Caucasus, into the southern boundaries of the Eurasian steppe.” ref

Analysis of the Mitochondrial Genome of a Novosvobodnaya Culture Representative using Next-Generation Sequencing and Its Relation to the Funnel Beaker Culture

Abstract