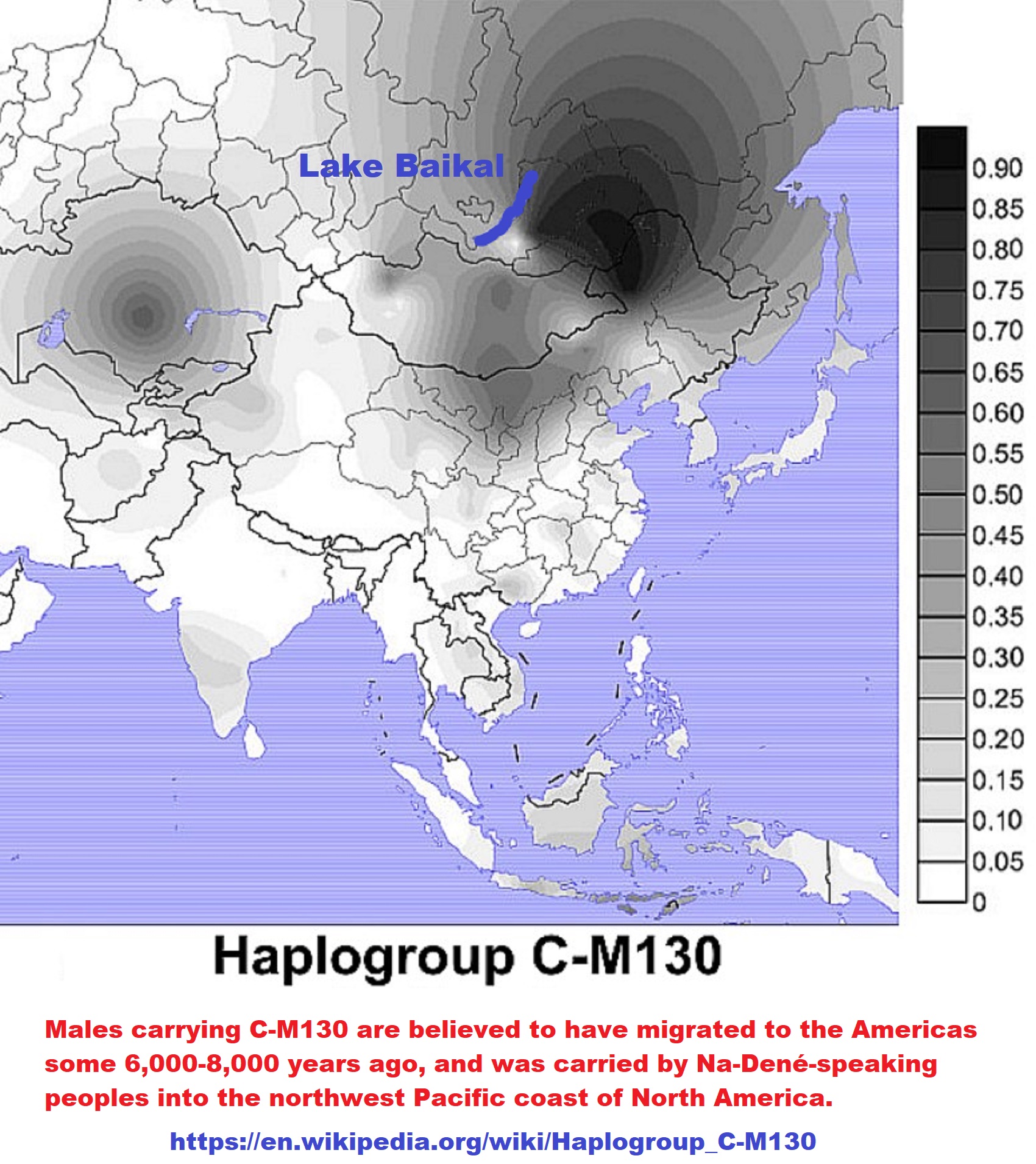

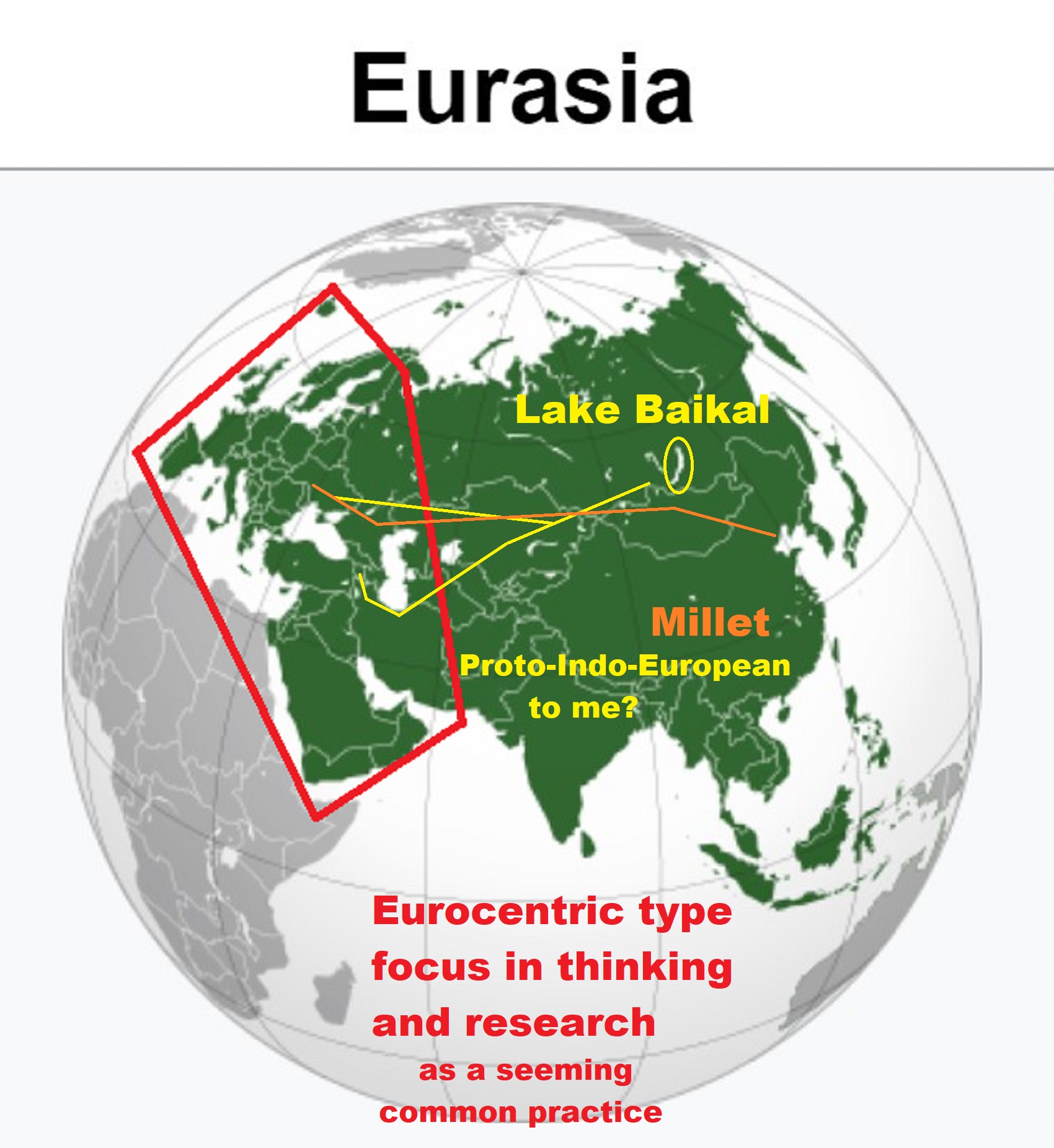

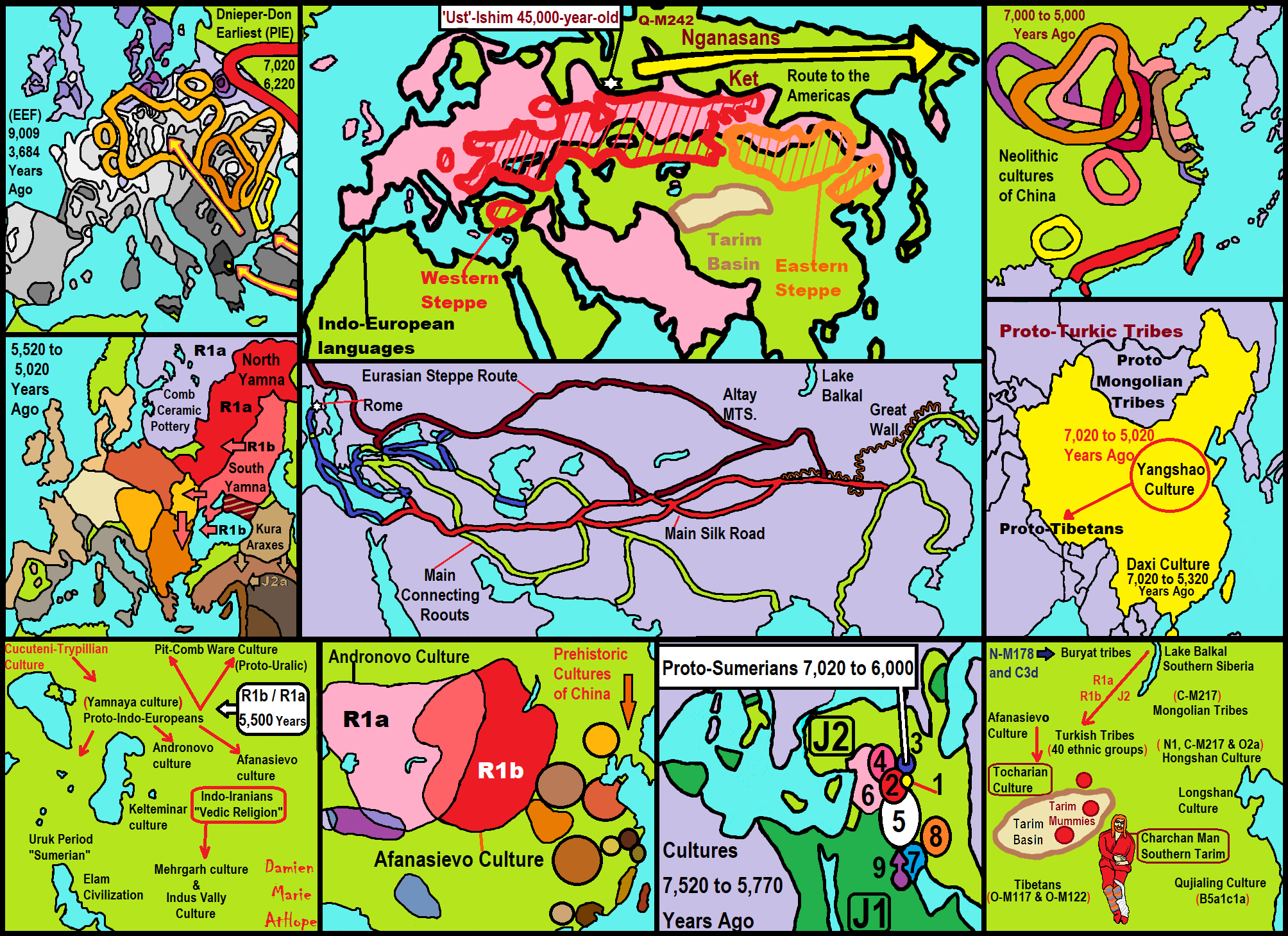

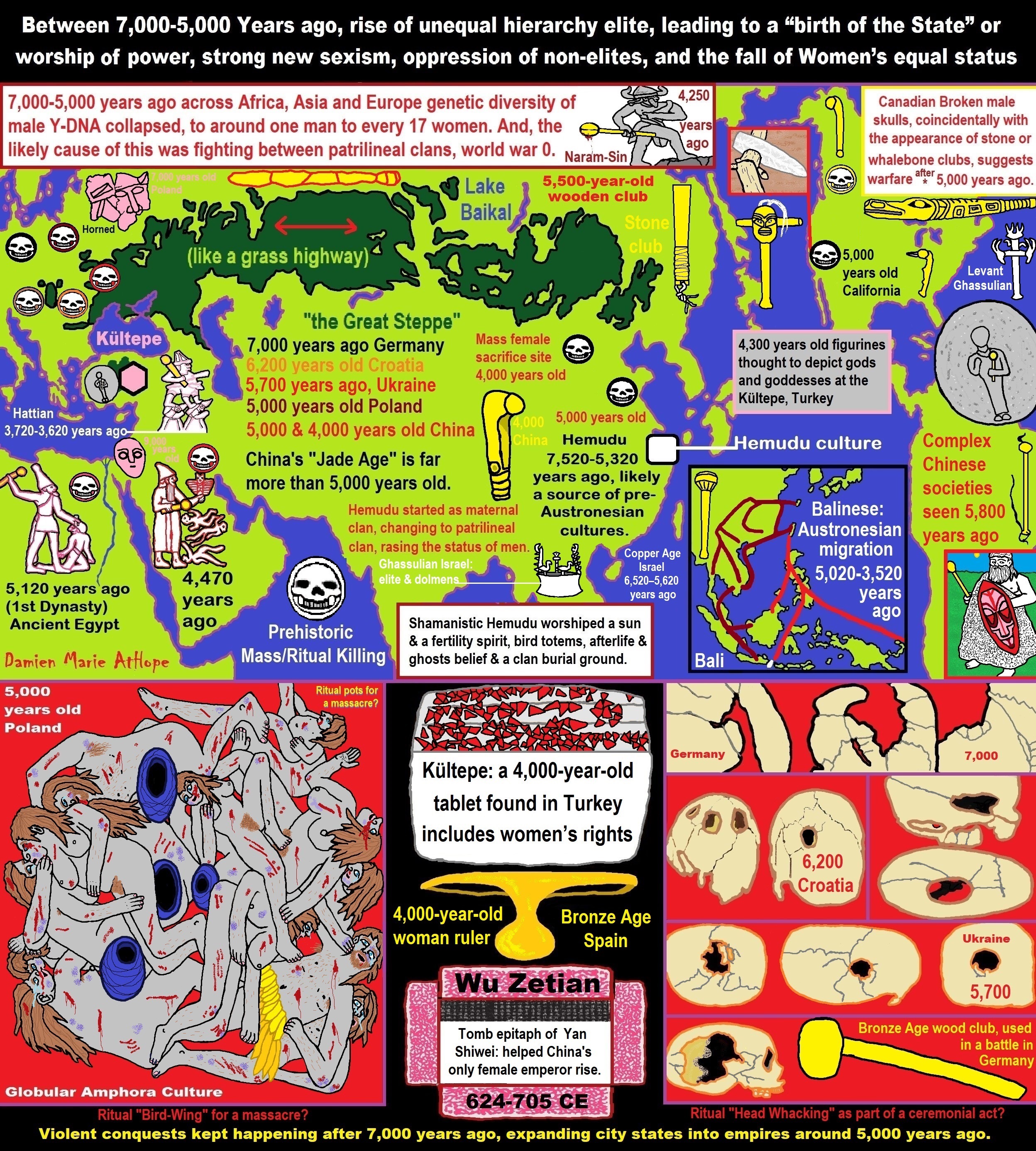

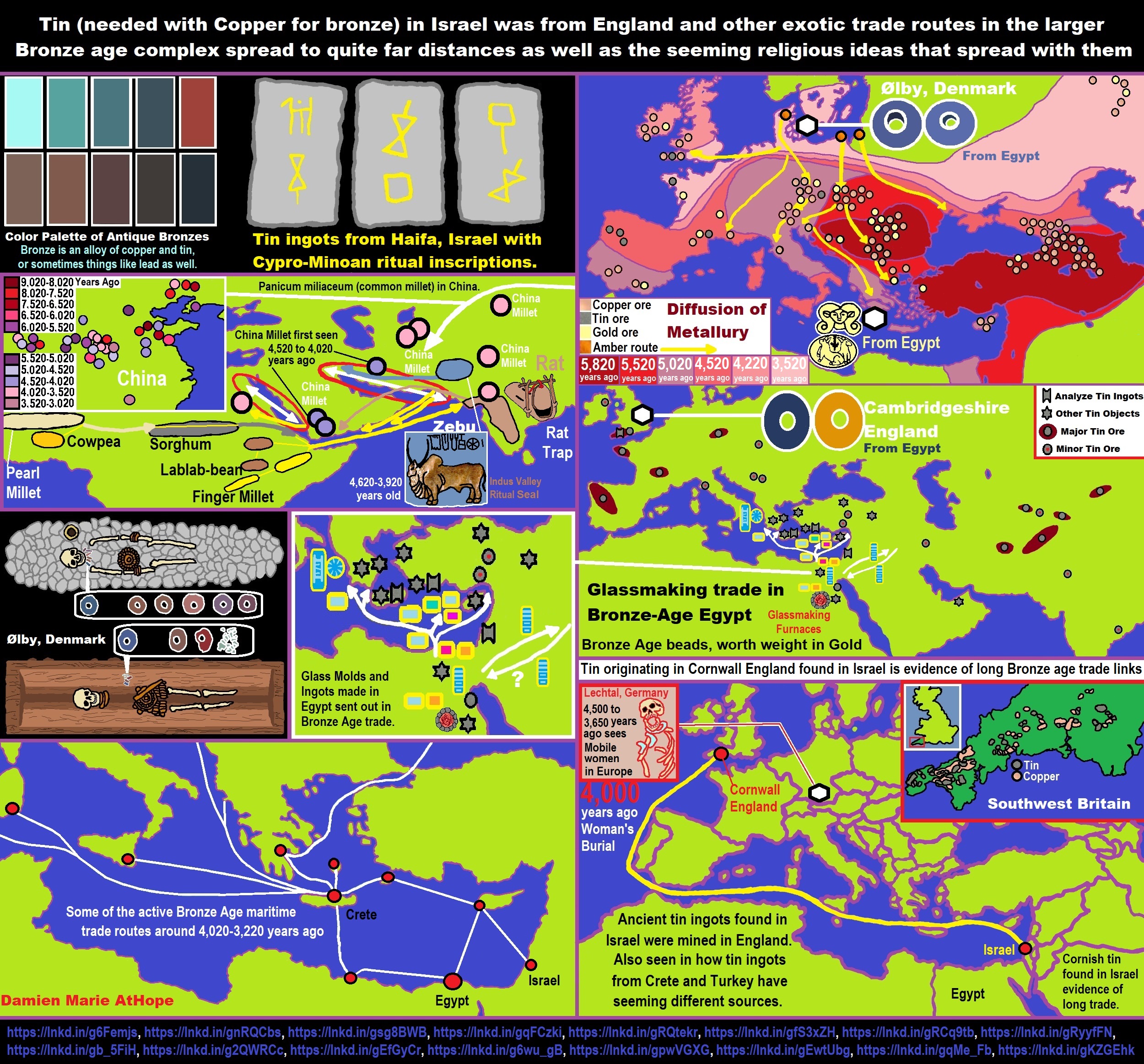

“Asian varieties of millet made their way from China to the Black Sea region of Europe by 5000 BCE or 7,000 years ago.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Millet

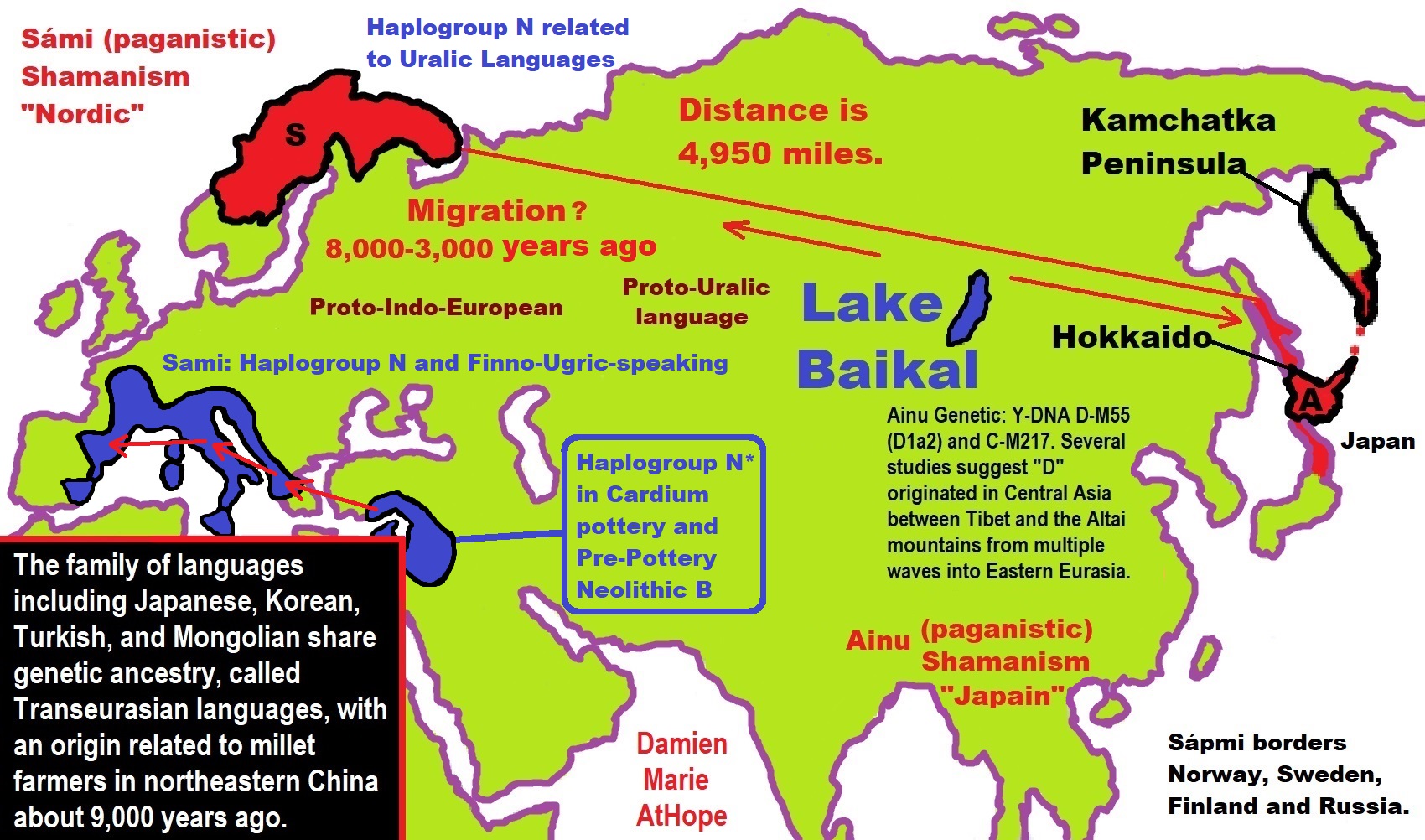

Origins of ‘Transeurasian’ languages traced to Neolithic millet farmers in north-eastern China about 9,000 years ago

“A study combining linguistic, genetic, and archaeological evidence has traced the origins of a family of languages including modern Japanese, Korean, Turkish and Mongolian and the people who speak them to millet farmers who inhabited a region in north-eastern China about 9,000 years ago. The findings outlined on Wednesday document a shared genetic ancestry for the hundreds of millions of people who speak what the researchers call Transeurasian languages across an area stretching more than 5,000 miles (8,000km).” ref

“Millet was an important early crop as hunter-gatherers transitioned to an agricultural lifestyle. There are 98 Transeurasian languages, including Korean, Japanese, and various Turkic languages in parts of Europe, Anatolia, Central Asia, and Siberia, various Mongolic languages, and various Tungusic languages in Manchuria and Siberia. This language family’s beginnings were traced to Neolithic millet farmers in the Liao River valley, an area encompassing parts of the Chinese provinces of Liaoning and Jilin and the region of Inner Mongolia. As these farmers moved across north-eastern Asia over thousands of years, the descendant languages spread north and west into Siberia and the steppes and east into the Korean peninsula and over the sea to the Japanese archipelago.” ref

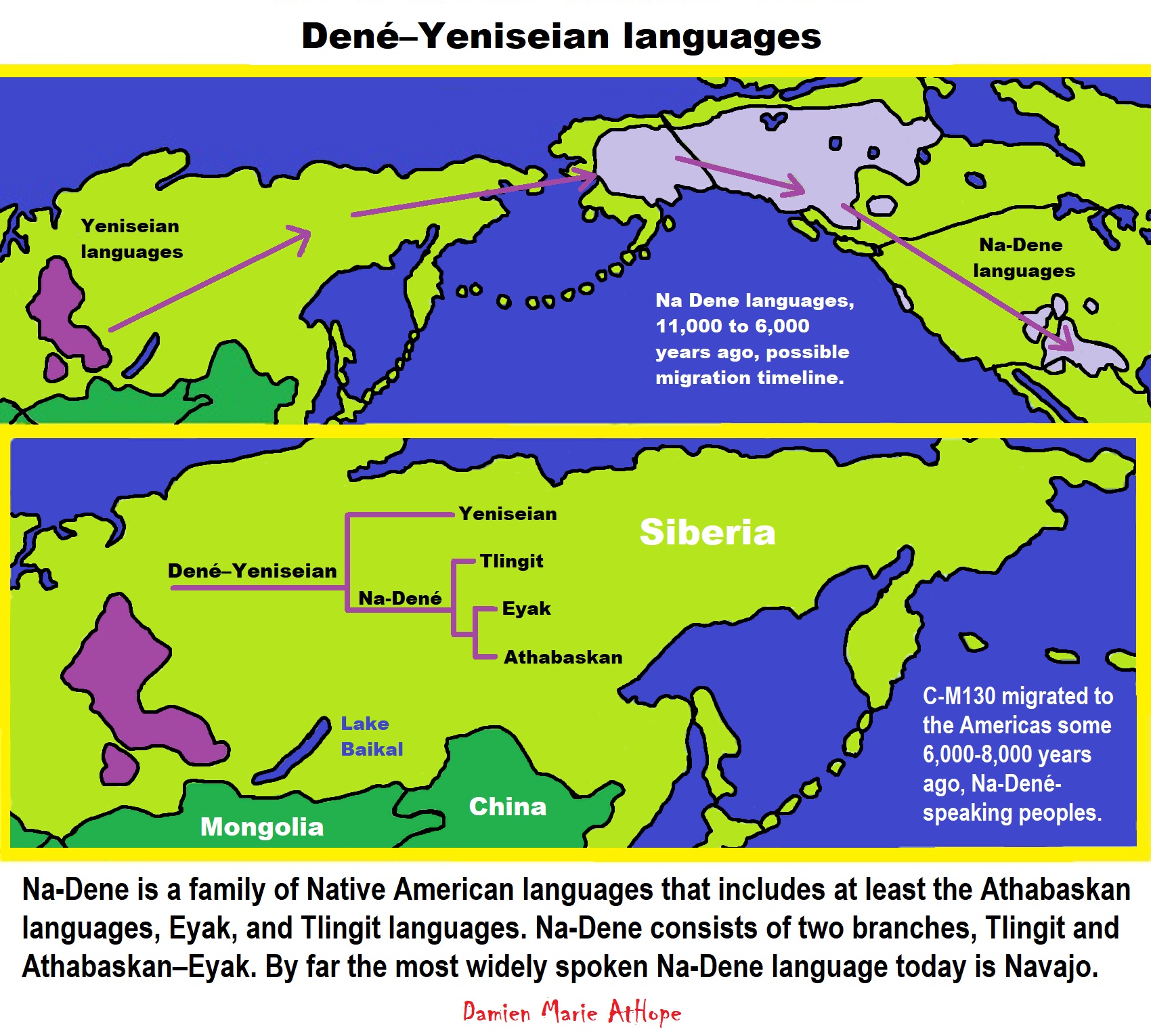

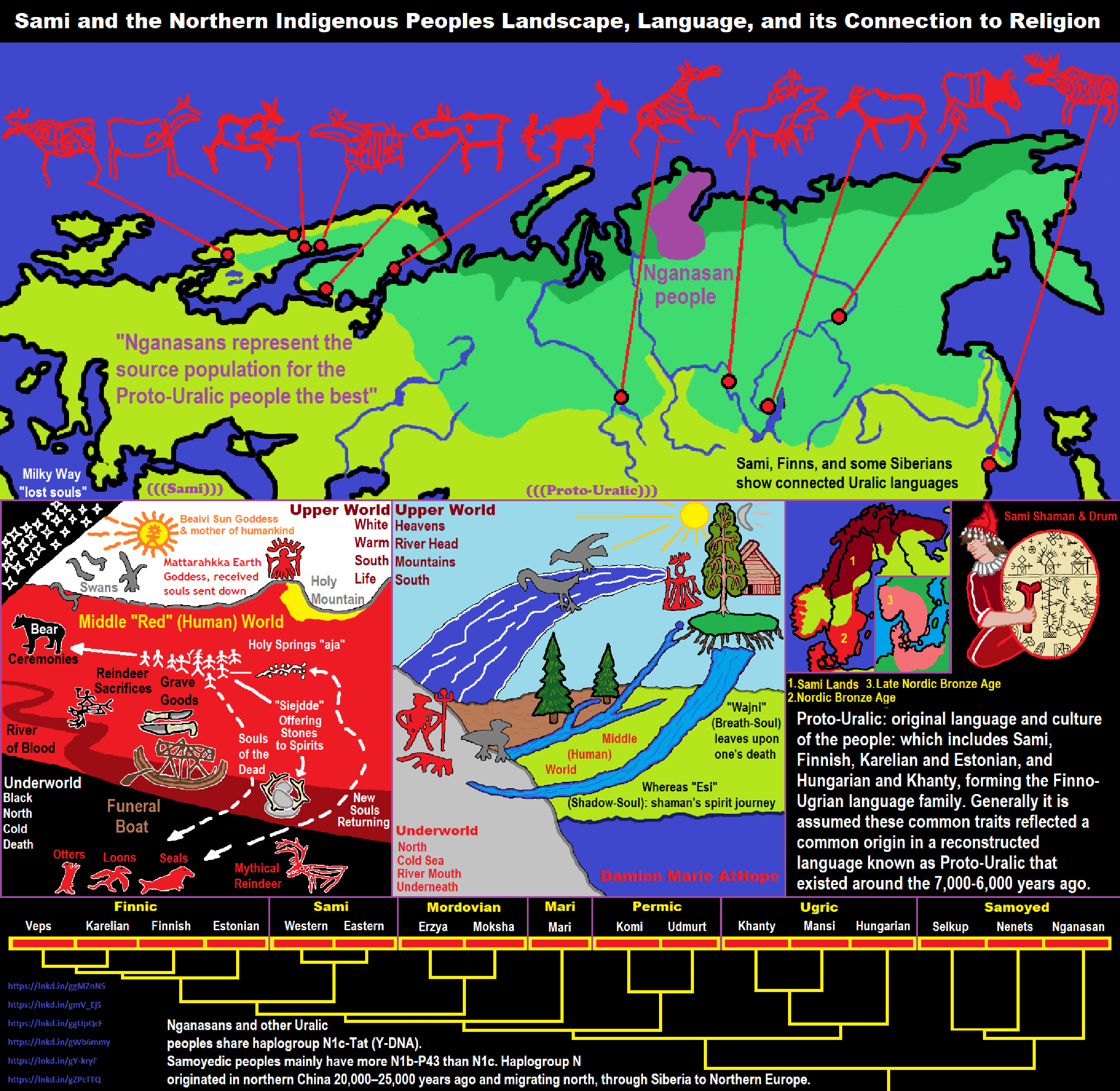

“Eurasiatic is a proposed language with many language families historically spoken in northern, western, and southern Eurasia; which typically include Altaic (Mongolic, Tungusic, and Turkic), Chukchi-Kamchatkan, Eskimo–Aleut, Indo-European, and Uralic.” ref

“Voiced stops such as /d/ occur in the Indo-European, Yeniseian, Turkic, Mongolian, Tungusic, Japonic and Sino-Tibetan languages. They have also later arisen in several branches of Uralic.” ref

“Uralo-Siberian is a hypothetical language family of Uralic, Yukaghir, Eskimo–Aleut and besides linguistic evidence, several genetic studies, support a common origin in Northeast Asia.” ref

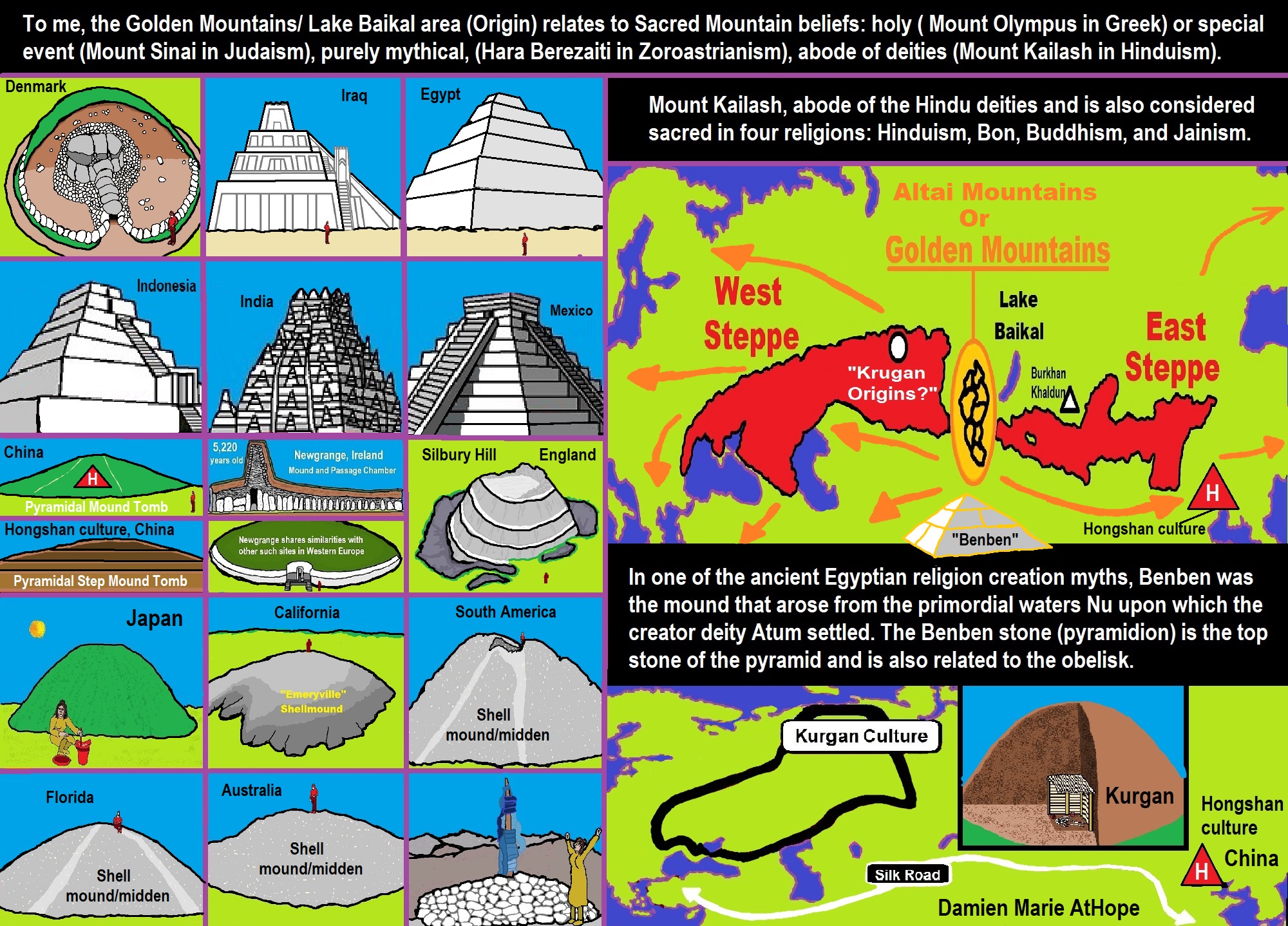

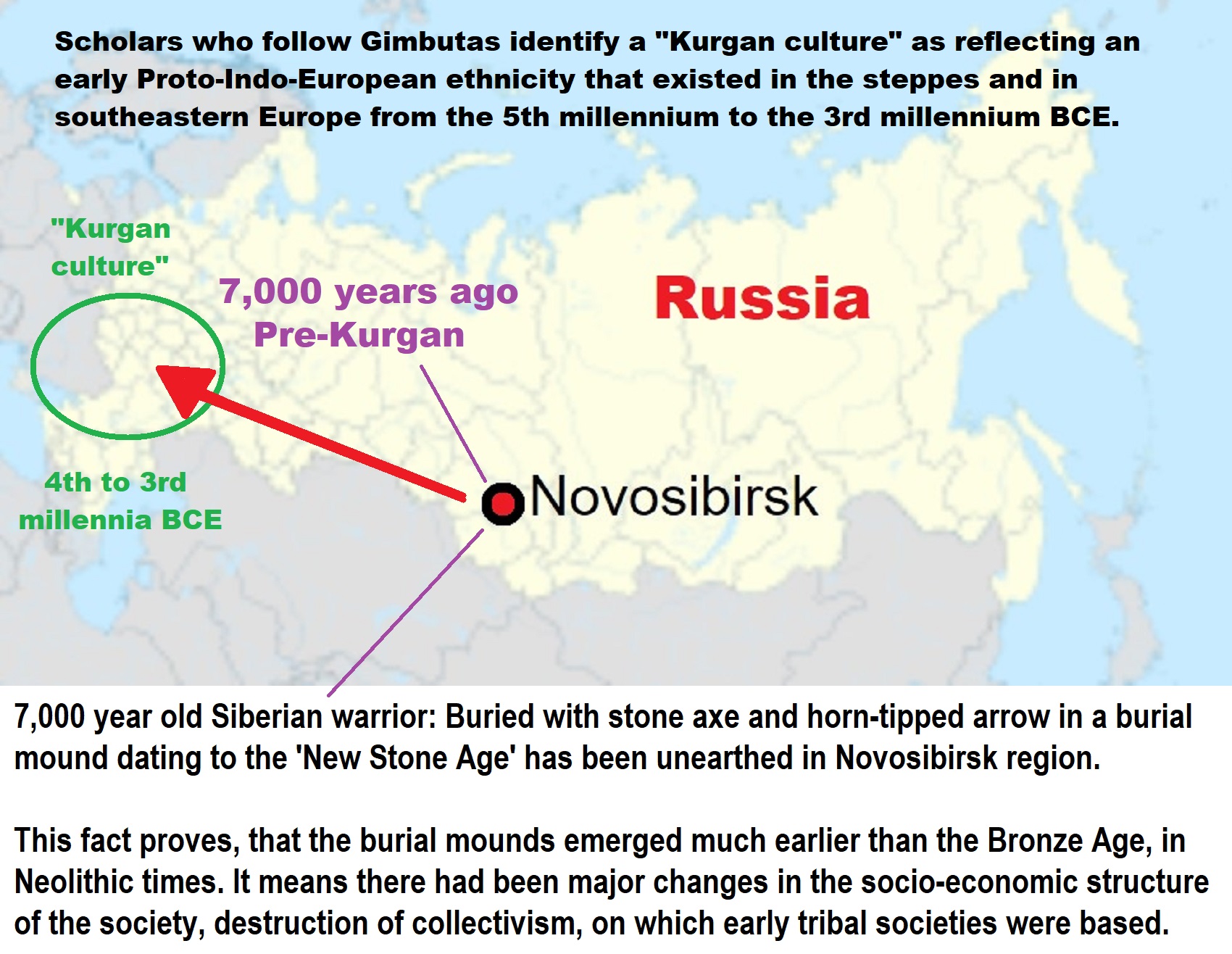

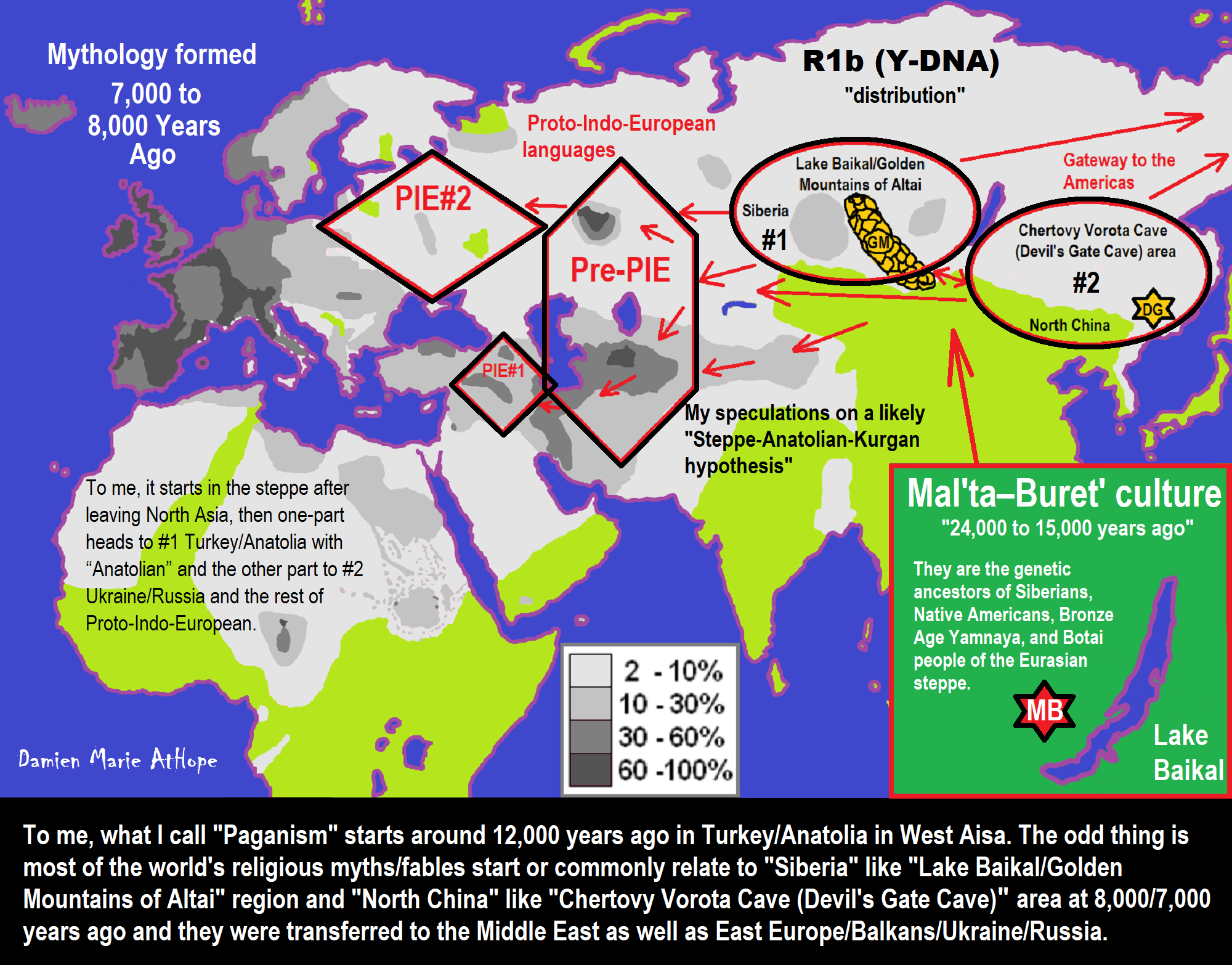

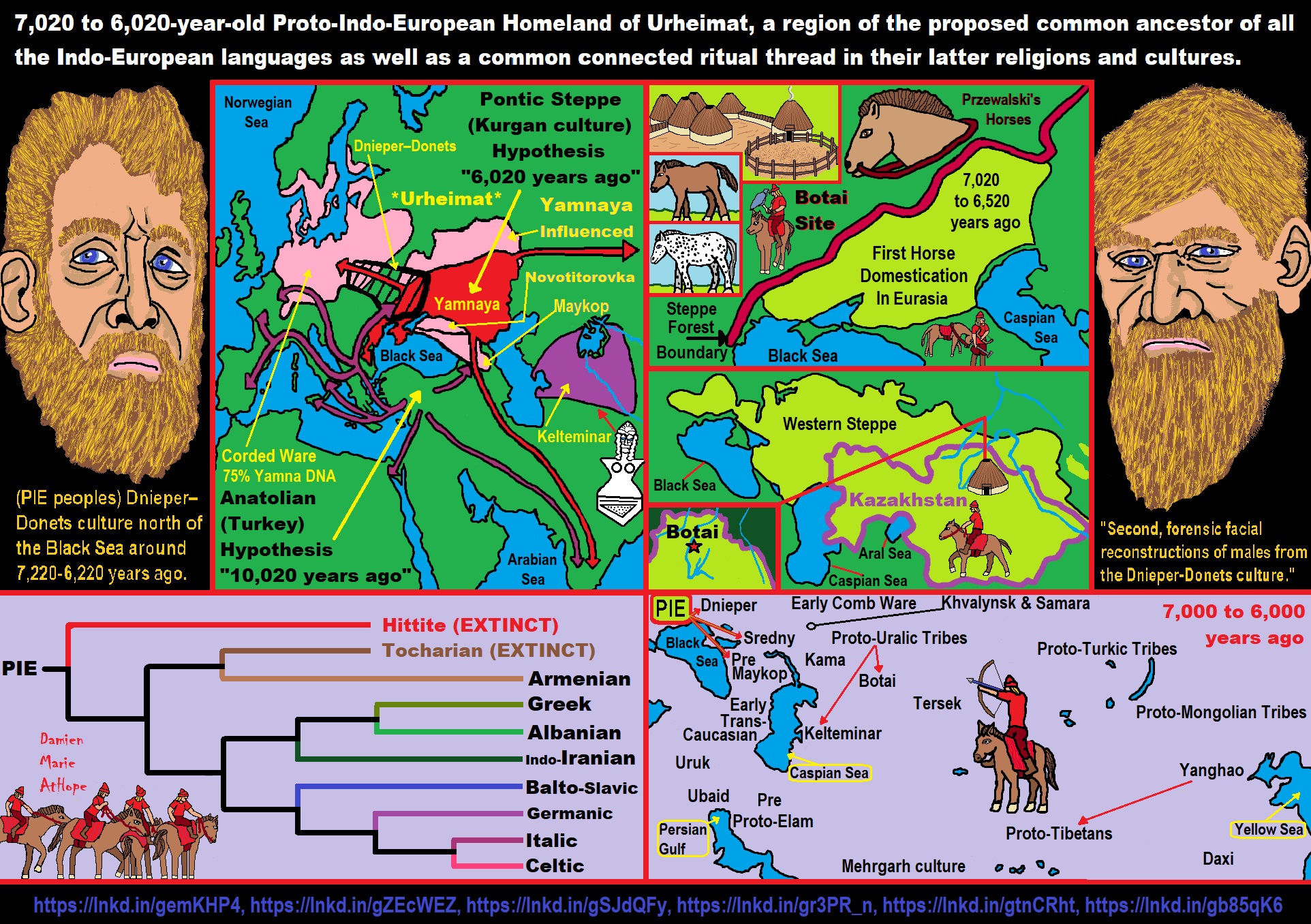

Kurgan Hypothesis

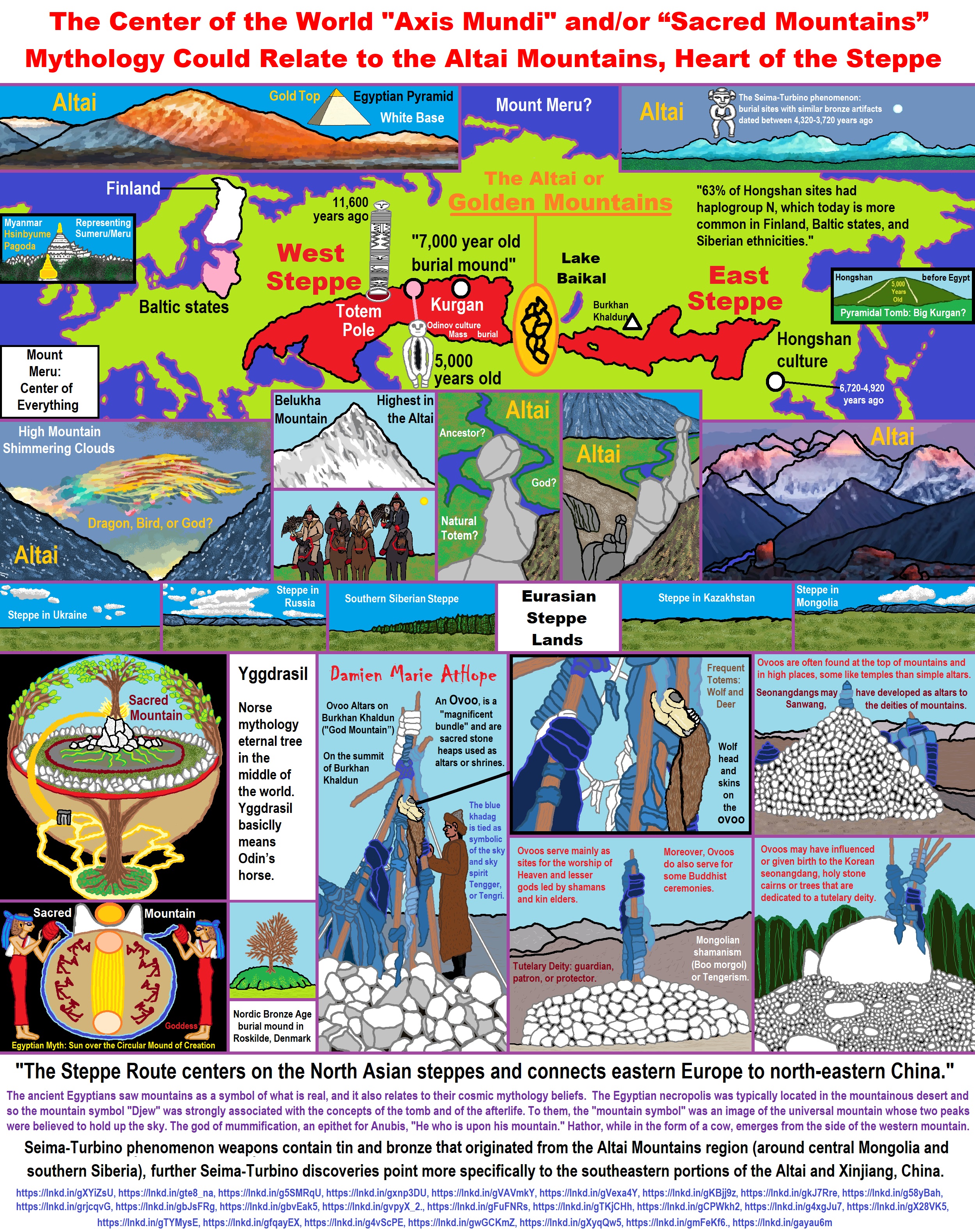

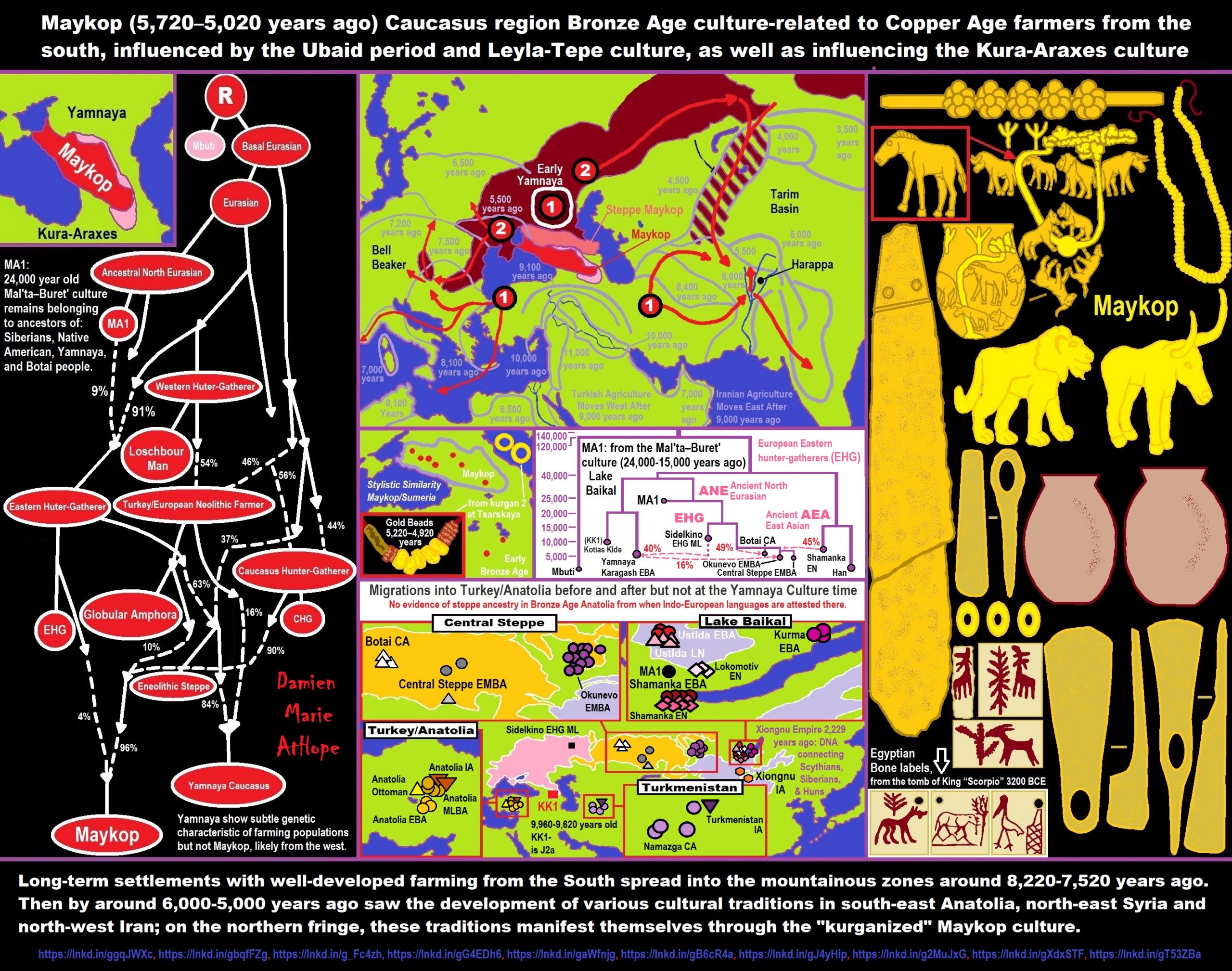

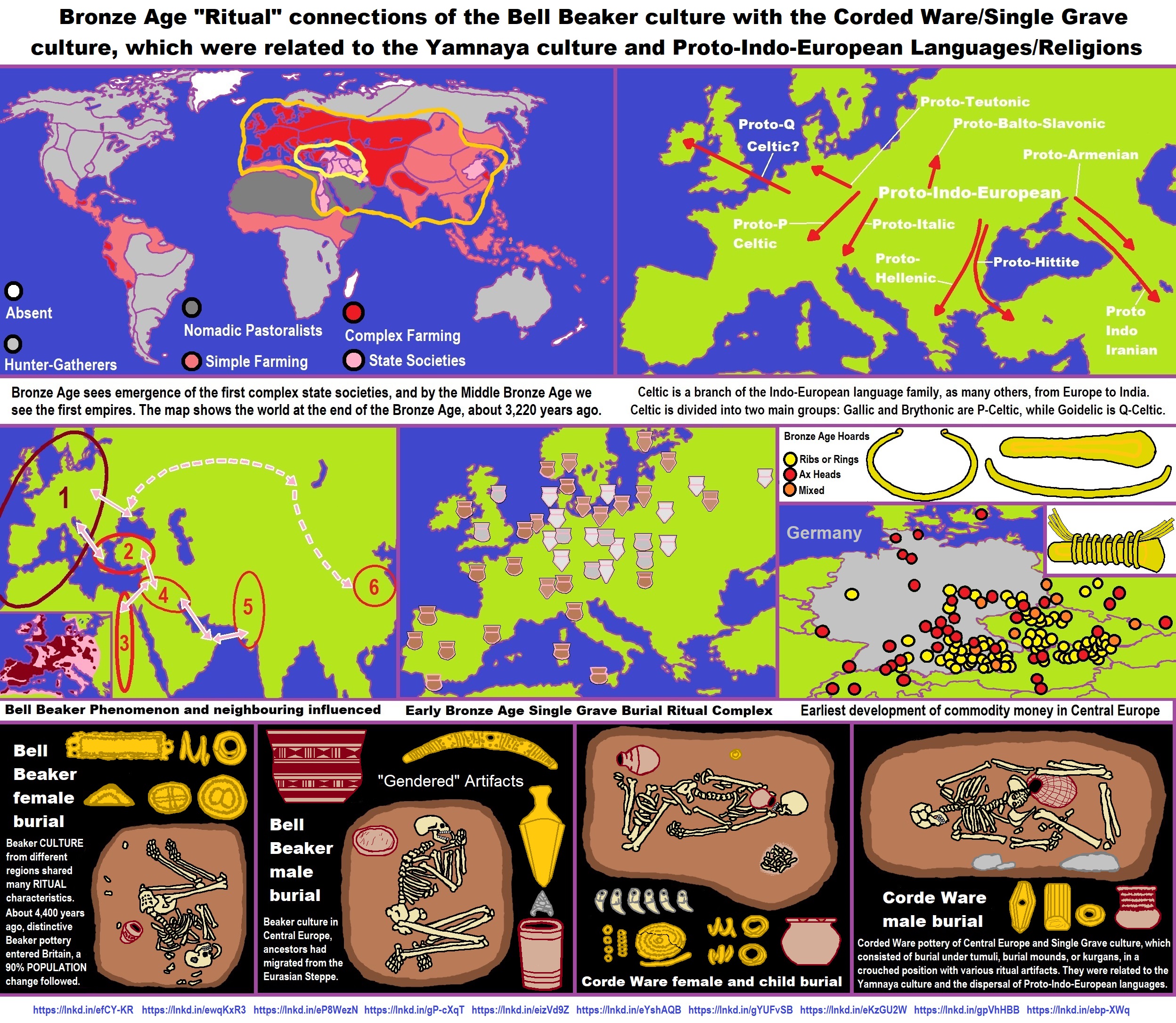

“The Kurgan hypothesis (also known as the Kurgan theory or Kurgan model) or Steppe theory is the most widely accepted proposal to identify the Proto-Indo-European homeland from which the Indo-European languages spread out throughout Europe and parts of Asia. It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). The term is derived from the Russian kurgan (курга́н), meaning tumulus or burial mound. The Steppe theory was first formulated by Otto Schrader (1883) and V. Gordon Childe (1926), then systematized in the 1950s by Marija Gimbutas, who used the term to group various prehistoric cultures, including the Yamnaya (or Pit Grave) culture and its predecessors. In the 2000s, David Anthony instead used the core Yamnaya culture and its relationship with other cultures as a point of reference.” ref

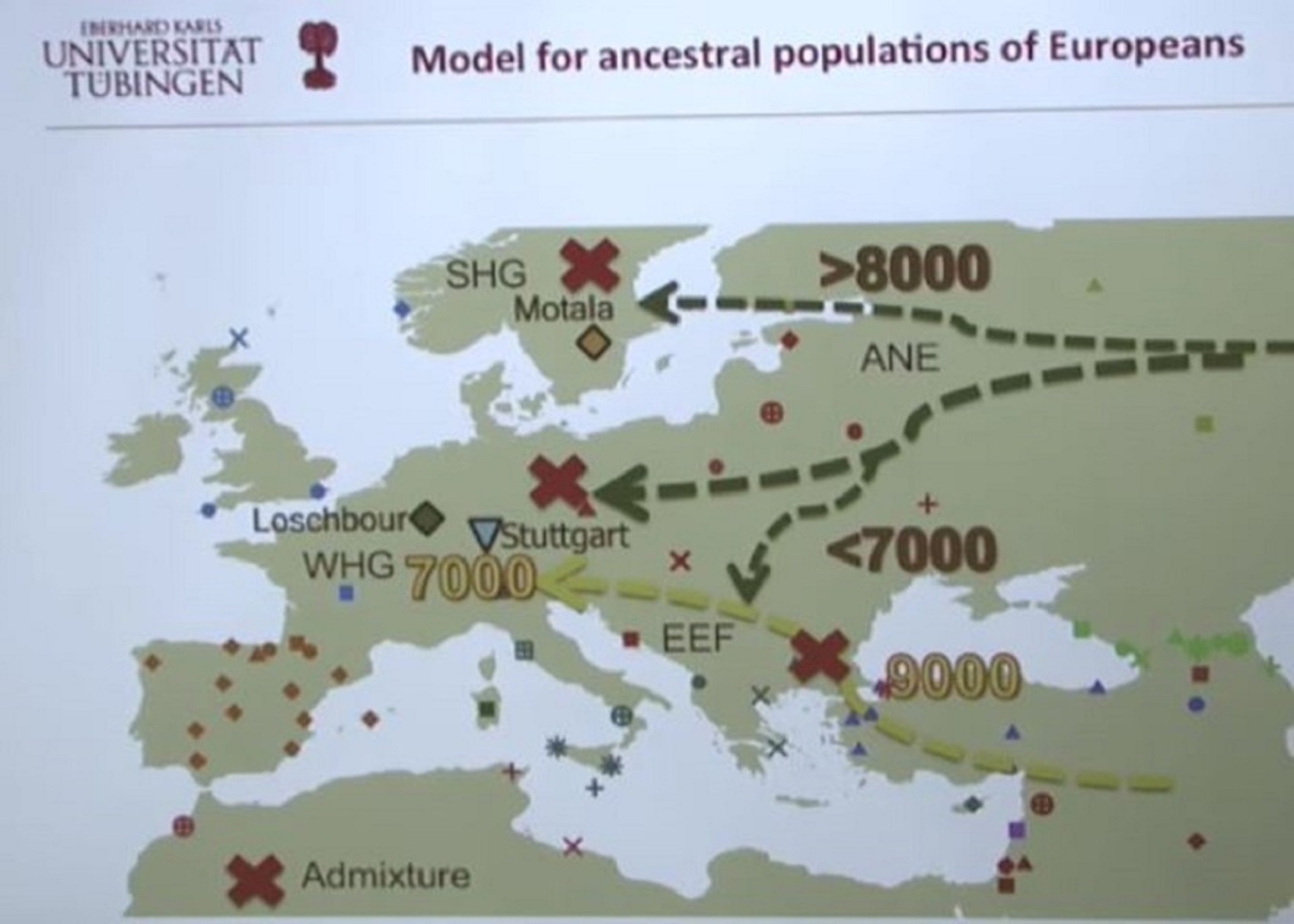

“Gimbutas defined the Kurgan culture as composed of four successive periods, with the earliest (Kurgan I) including the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures of the Dnieper–Volga region in the Copper Age (early 4th millennium BCE). The people of these cultures were nomadic pastoralists, who, according to the model, by the early 3rd millennium BCE had expanded throughout the Pontic–Caspian steppe and into Eastern Europe. Recent genetics studies have demonstrated that populations bearing specific Y-DNA haplogroups and a distinct genetic signature expanded into Europe and South Asia from the Pontic-Caspian steppe during the third and second millennia BCE. These migrations provide a plausible explanation for the spread of at least some of the Indo-European languages, and suggest that the alternative Anatolian hypothesis, which places the Proto-Indo-European homeland in Neolithic Anatolia, is less likely to be correct.” ref

“Cultures that Gimbutas considered as part of the “Kurgan culture”:

- Bug–Dniester (6th millennium)

- Samara (5th millennium)

- Khvalynsk (5th millennium)

- Dnieper–Donets (5th to 4th millennia)

- Sredny Stog (mid-5th to mid-4th millennia)

- Maikop–Dereivka (mid-4th to mid-3rd millennia)

- Yamnaya (Pit Grave): This is itself a varied cultural horizon, spanning the entire Pontic–Caspian steppe from the mid-4th to the 3rd millennium.

- Usatovo culture (late 4th millennium)” ref

Pic ref

Ancient Women Found in a Russian Cave Turn Out to Be Closely Related to The Modern Population https://www.sciencealert.com/ancient-women-found-in-a-russian-cave-turn-out-to-be-closely-related-to-the-modern-population

Abstract

“Ancient genomes have revolutionized our understanding of Holocene prehistory and, particularly, the Neolithic transition in western Eurasia. In contrast, East Asia has so far received little attention, despite representing a core region at which the Neolithic transition took place independently ~3 millennia after its onset in the Near East. We report genome-wide data from two hunter-gatherers from Devil’s Gate, an early Neolithic cave site (dated to ~7.7 thousand years ago) located in East Asia, on the border between Russia and Korea. Both of these individuals are genetically most similar to geographically close modern populations from the Amur Basin, all speaking Tungusic languages, and, in particular, to the Ulchi. The similarity to nearby modern populations and the low levels of additional genetic material in the Ulchi imply a high level of genetic continuity in this region during the Holocene, a pattern that markedly contrasts with that reported for Europe.” ref

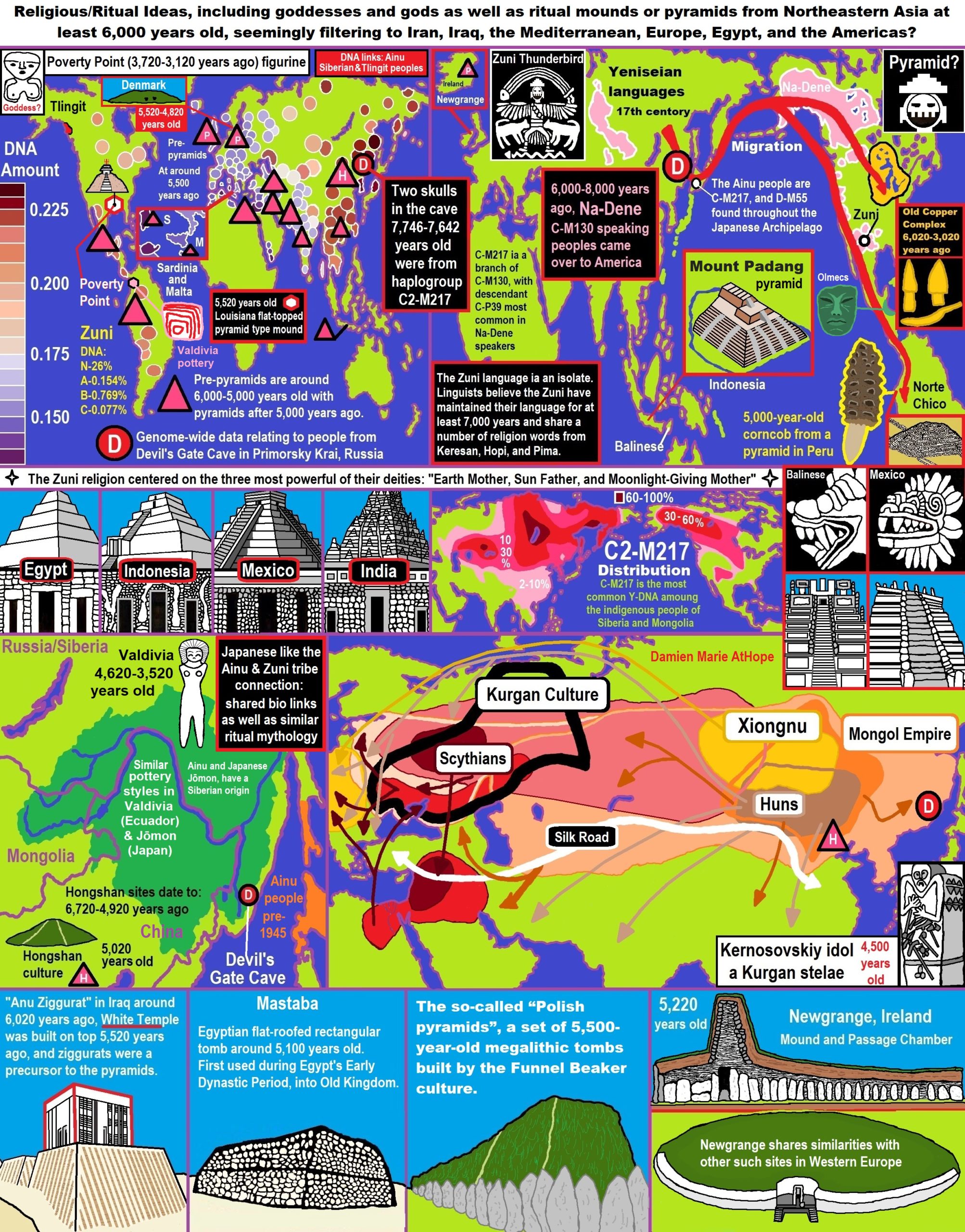

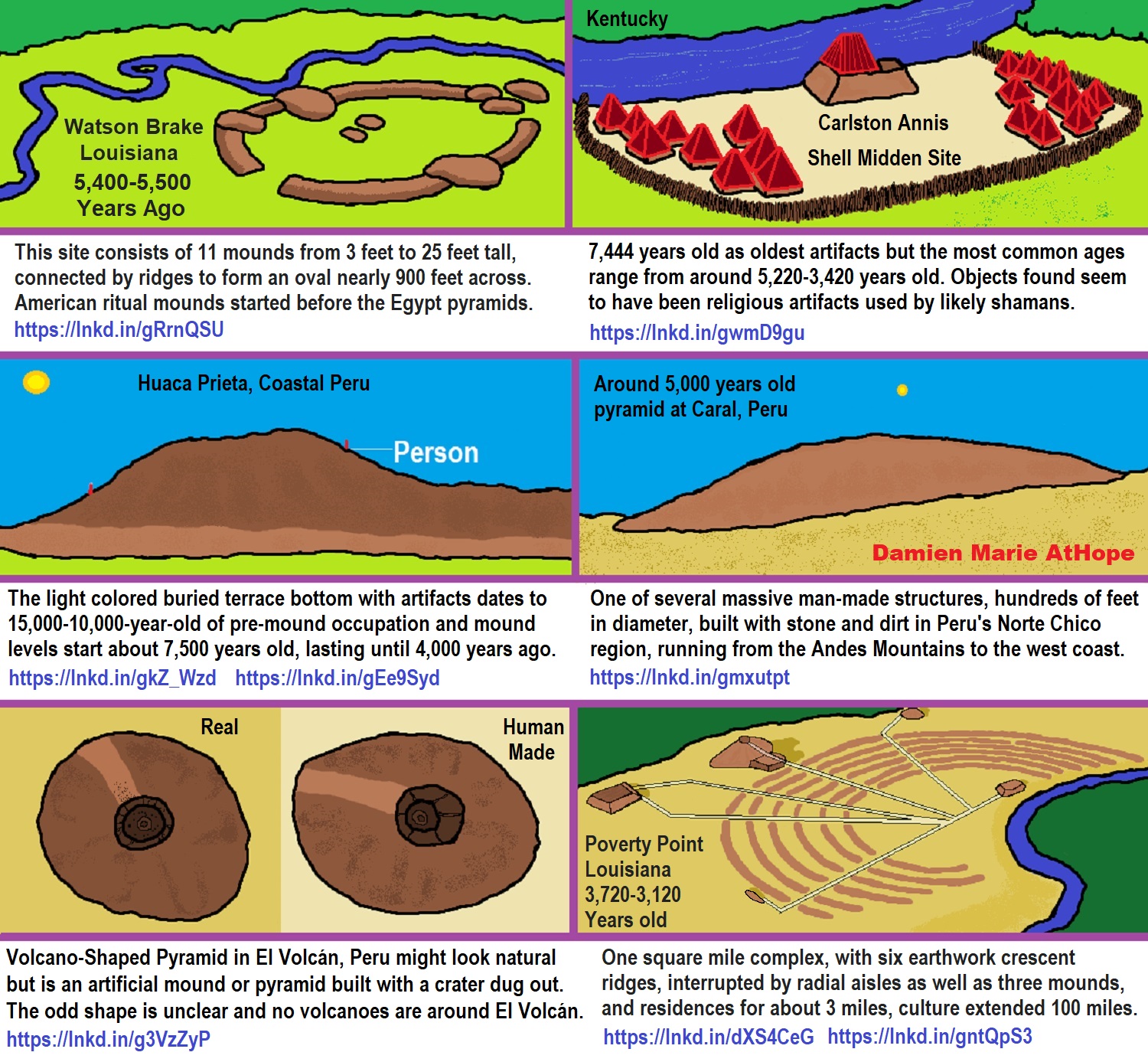

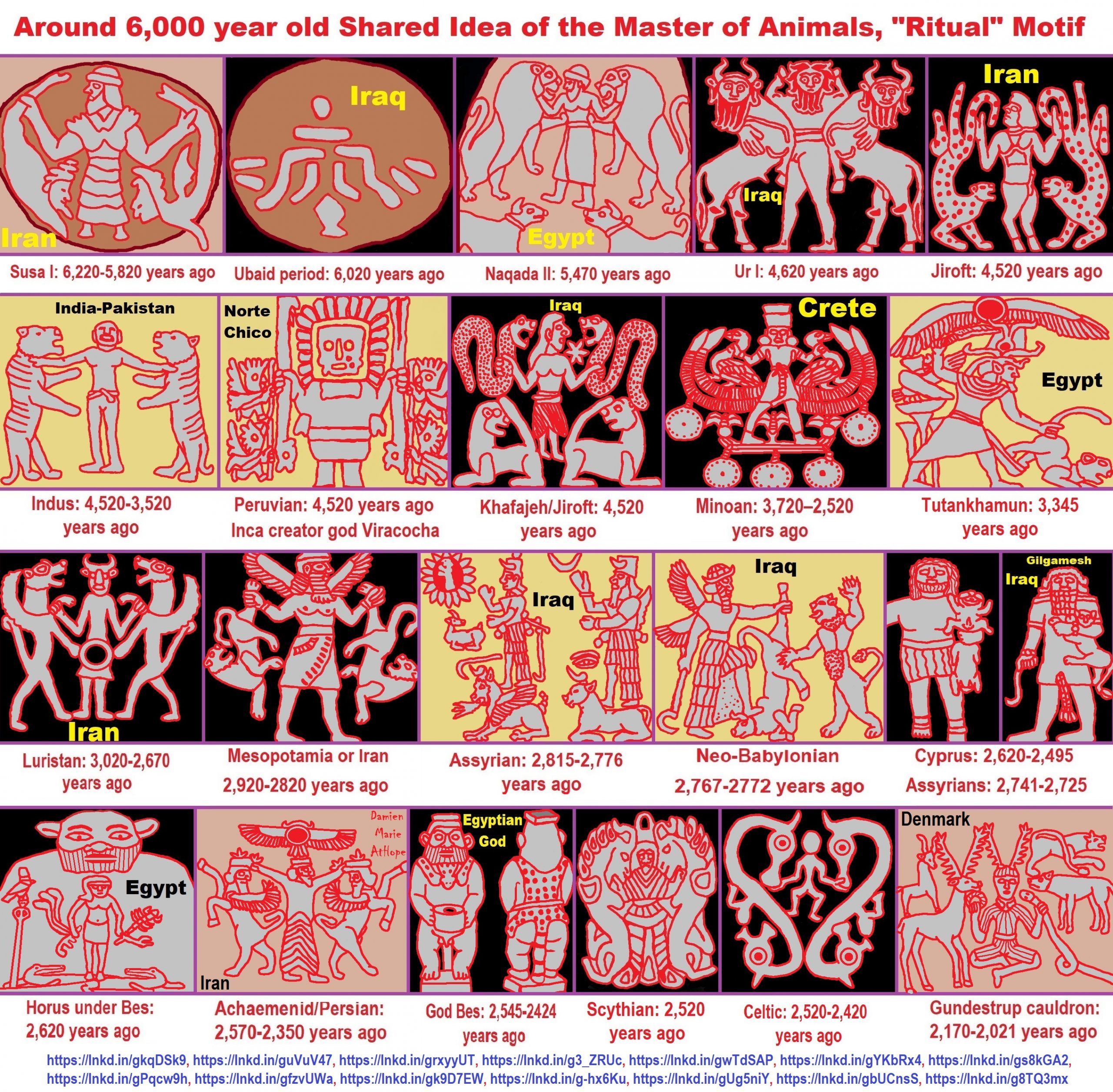

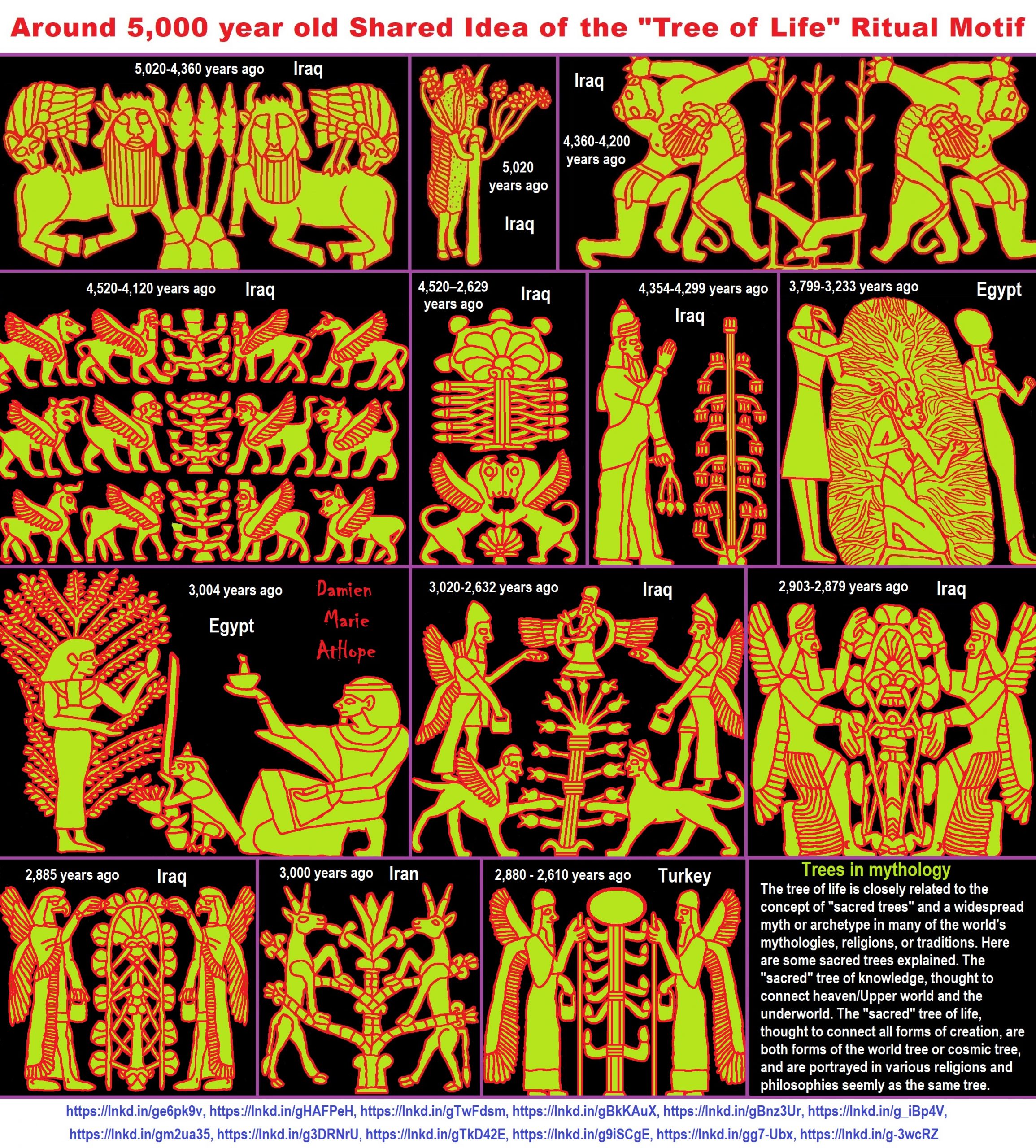

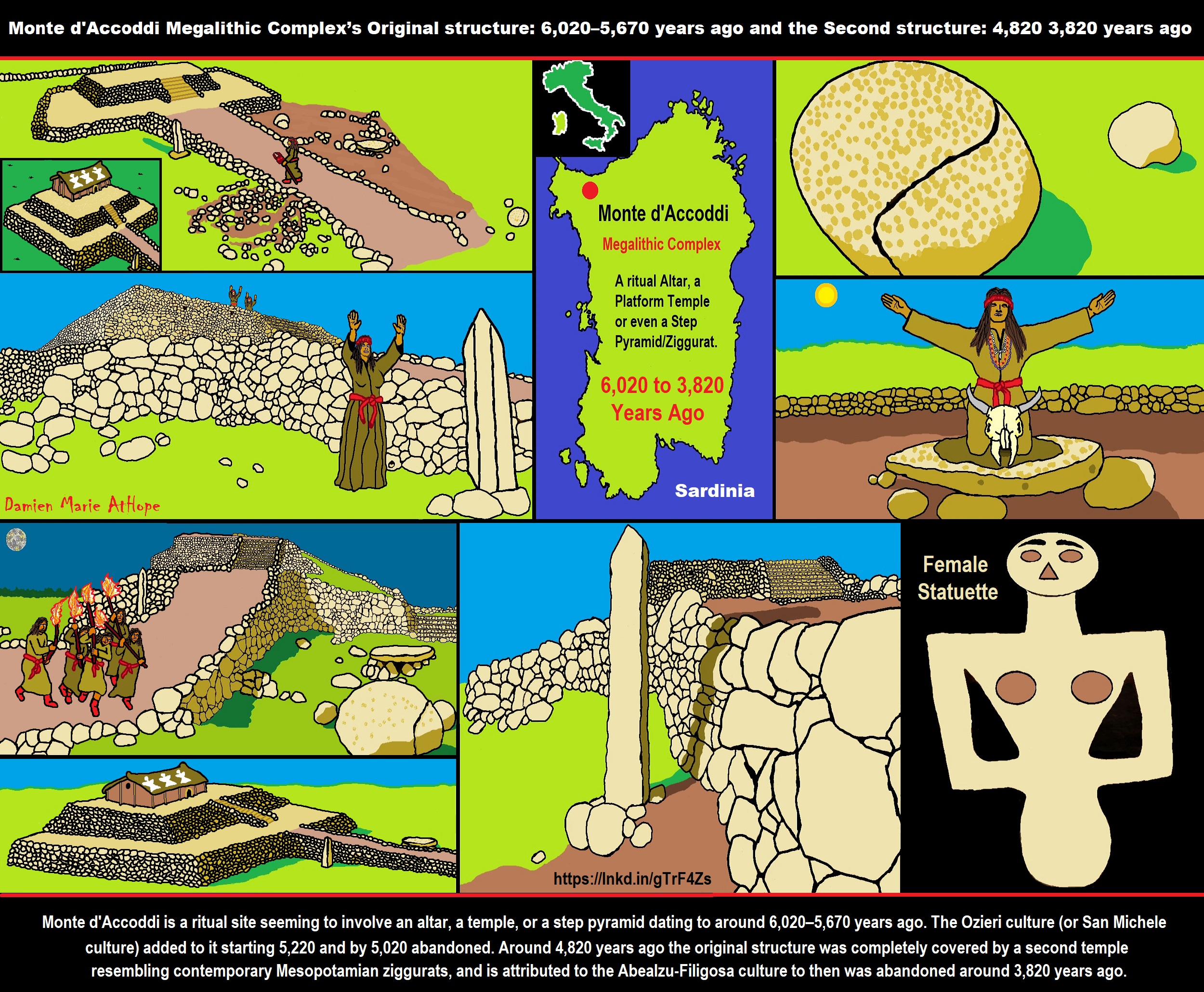

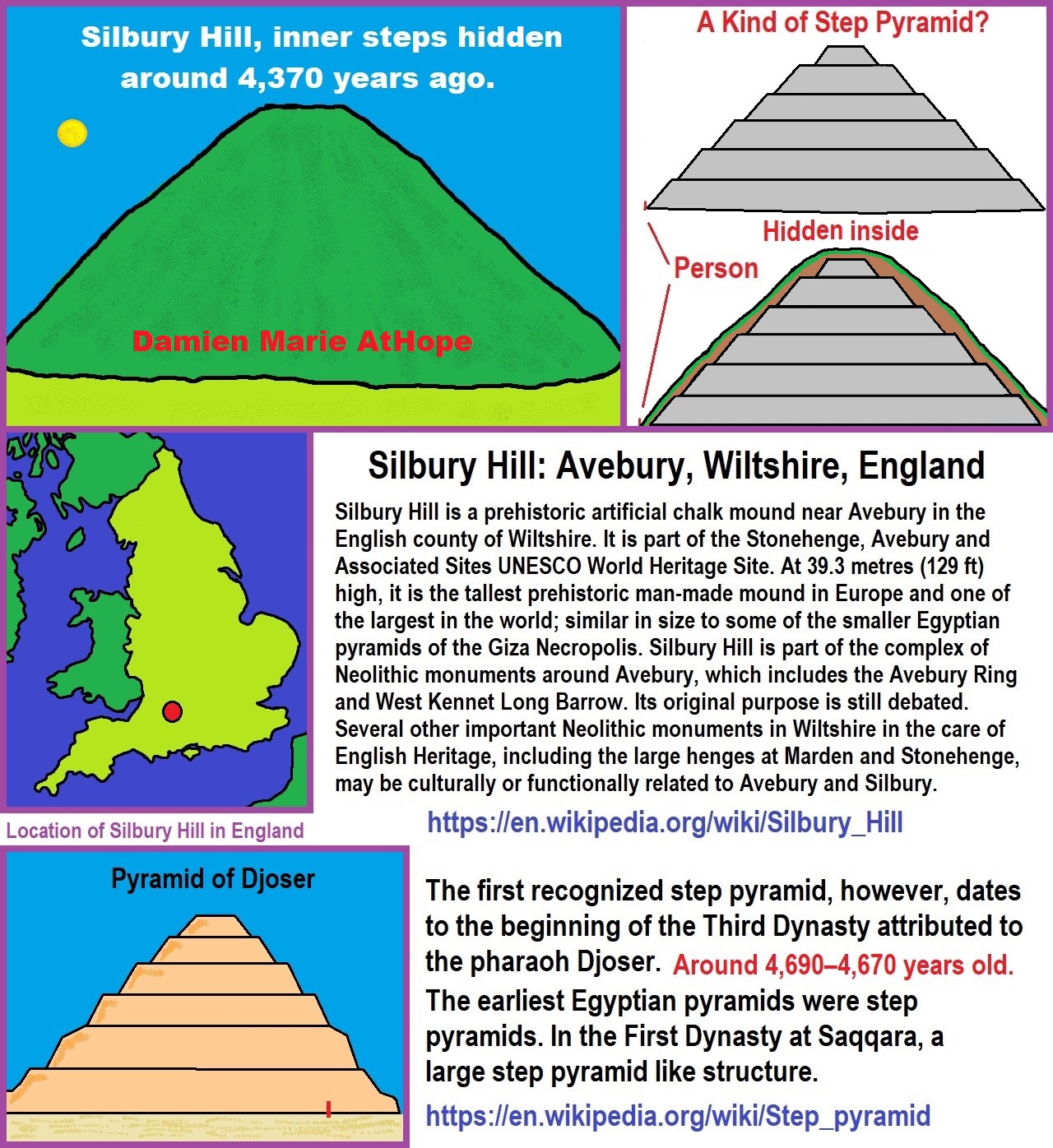

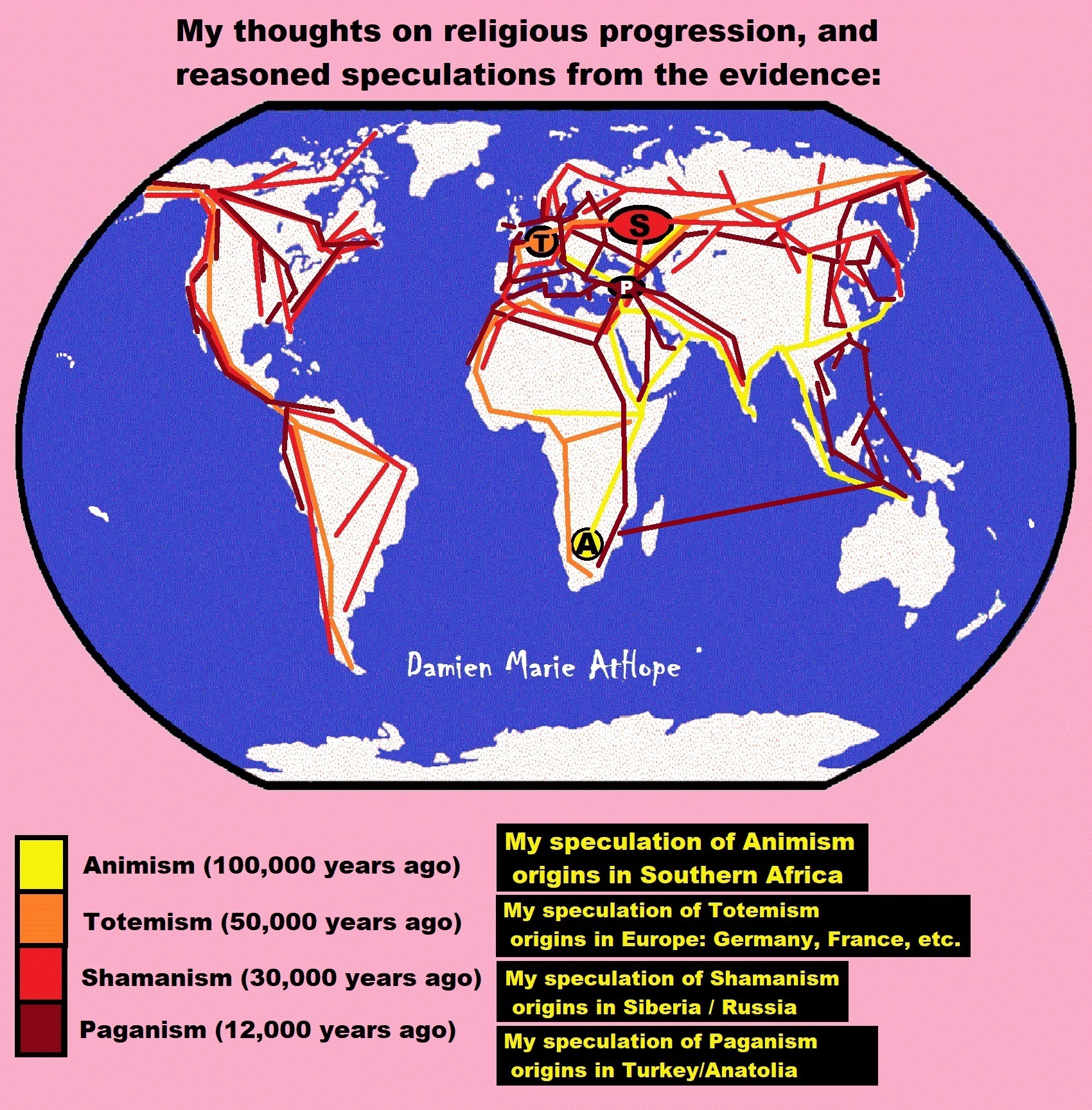

This info connects in a way to sort of my main point, that religions are a cultural product and were spread by people migrating and by transfer to were many crossed the globe. And one may wonder why this was not all realized before? I can offer one of many possible answers or reasons, when you are focusing hard on one specific areas, it is easy to miss the big picture, and thus lack an accurate assessment. Pre-pyramids are around 6,000-5,000 years old with pyramids after 5,000 years ago. “Anu Ziggurat” in Iraq around 6,020 years ago, White Temple was built ontop 5,520 years ago, and ziggurats were a precursor to the pyramids. ref, ref

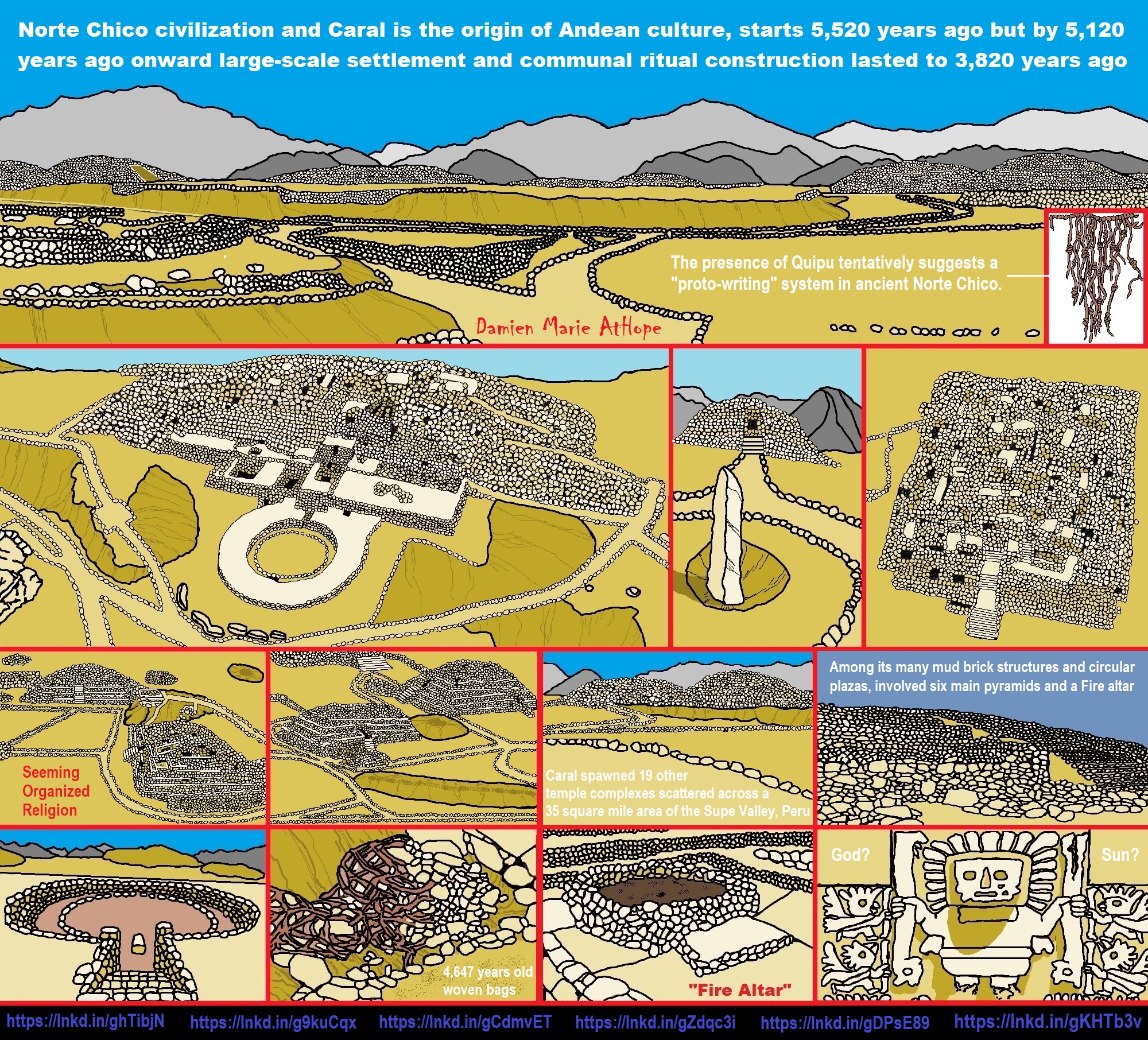

5,000-Year-Old Pyramid-Like Structure Found In Northern Peru

“A pyramid-like structure at least 5,000 years old, allegedly devoted to ceremonial purposes, was unveiled thanks to excavation works conducted at Sechin archaeological complex in Casma Province of Ancash Region in northern Peru. It is a stepped structure, at least 3.20 meters high and 5 meters wide. Sechin Archaeological Project archaeologists and workers had to excavate some 6 meters of soil and remove stones in order to unearth it.” ref

Archaeologist Monica Suarez, the coordinator at Sechin Archaeological Project, commented that the pyramid is located within the south-central part of the main building. It is believed that it was used for ceremonial purposes. Additionally, the team of researchers discovered two skulls —one of an adult and one of a child— and a dismembered body on the side, which makes the theory of ceremonial practices gain traction. The researcher stressed the possibility that the stepped, pyramid-shaped structure served as a ladder to get to a higher level.

“There is an adobe wall at the top, with fingerprints of Sechin inhabitants visible in the mud. They are believed to be a symbol of their work,” she said.” ref

Unearthing the ancient ‘pharaohs’ of the Emerald Isle

“From elaborate burials to family affairs, new DNA analysis suggests that Irish kings may have had more in common with their Egyptian counterparts, writes James Gorman Newgrange, a prehistoric monument built during the Neolithic period. The vast Stone Age tomb mounds in the valley of the River Boyne, about 25 miles north of Dublin, are so impressive that the area has been called the Irish Valley of the Kings. And a new analysis of ancient human DNA from Newgrange, the most famous of the mounds in Ireland, suggests that the ancient Irish may have had more than monumental grave markers in common with the pharaohs.” ref

“A team of Irish geneticists and archaeologists reported last week that a man whose cremated remains were interred at the heart of Newgrange was the product of a first-degree incestuous union, either between parent and child or brother and sister. The finding, combined with other genetic and archaeological evidence, suggests that the people who built these mounds lived in a hierarchical society with a ruling elite that considered themselves so close to divine that, like the Egyptian pharaohs, they could break the ultimate taboos.” ref

“In Ireland, more than 5,000 years ago people farmed and raised cattle. But they were also moved, like their contemporaries throughout Europe, to create stunning monuments to the dead, some with precise astronomical orientations. Stonehenge, a later megalith in the same broad tradition as Newgrange, is famous for its alignment to the summer and winter solstice. The central underground room at Newgrange is built so that as the sun rises around the time of the winter solstice it illuminates the whole chamber through what is called a roof box.” ref

“Archaeologists have long wondered what kind of society built such a structure, which they think must have had ritual or spiritual significance. If, as the findings indicate, it was a society that honored the product of an incestuous union by interring his remains at the most sacred spot in a sacred place, then the ancient Irish may have had a ruling religious hierarchy, perhaps similar to those in ancient societies in Egypt, Peru, and Hawaii, which also allowed marriages between brother and sister. In a broad survey of ancient DNA from bone samples previously collected at Irish burial sites thousands of years old, the researchers also found genetic connections among people interred in other Irish passage tombs, named for their underground chambers or passages. That suggests that the ruling elite were related to one another.” ref

“Of the site’s tombs, Bradley says, “Newgrange is the apogee”. It is not just that it incorporates 200,000 tons of earth and stone, some brought from kilometers away. It also has the precise orientation to the winter sun. On any day, “when you go into the chamber, it’s a sort of numinous space, it’s a liminal space, a place that inspires a sort of awe”, Bradley says. That a bone recovered from this spot produced such a genomic shocker seemed beyond coincidence. This had to be a prominent person, the researchers reasoned. He wasn’t placed there by accident, and his parentage was unlikely to be an accident. “Whole chunks of the genome that he inherited from his mother and father, whole chunks of those were just identical,” Bradley says. The conclusion was unavoidable: “It’s a pharaoh, I said, it’s an Irish pharaoh.” ref

I think it’s part of the wave of the future about how ancient DNA will shed light on social structure, which is really one of its most exciting promises

“He and his colleagues had not gone looking for children of incest. They were analyzing ancient bones to sequence 42 genomes of Neolithic Irish farmers as part of a project to reconstruct the entire genetic history of Ireland. The researchers sampled DNA from human remains from the four kinds of burial in Ireland, from the simplest to the most elaborate. They used techniques similar to those that for-profit companies now use to help people discover unknown relatives and ancestral connections. This involves looking for extended chunks of DNA that are common to different samples, rather than comparing the average differences in individual genes. “It’s like looking at the sentences rather than the letters,” Bradley says. The researchers sequenced four full genomes. The others, as is common in this kind of research, were partial.” ref

Signs of a Hierarchical Society

“David Reich of Harvard University, one of the ancient DNA specialists who has tracked the grand sweep of prehistoric human migration around the globe, and was not involved in the research, called the journal article “amazing”. “I think it’s part of the wave of the future about how ancient DNA will shed light on social structure, which is really one of its most exciting promises,” he says, although he had some reservations about evidence that the elite were genetically separate from the common people, a kind of royal family.” ref

A Holy Place

“Daniel G Bradley, a specialist in ancient DNA at Trinity College, who leads the team with Lara M Cassidy, a specialist in population genetics and Irish prehistory also at the college, says the genome of the man who was a product of incest was a complete surprise. They and their colleagues have reported their findings in the journal Nature. Newgrange is part of a necropolis called Bru na Boinne, or the palace of the Boyne, dating to around 5,000 years ago that includes three large passage tombs and many other monuments. It is one of the most remarkable of Neolithic monumental sites in all of Europe. Bettina Schulz Paulsson, a prehistoric archaeologist at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, says the researchers’ findings that suggest a religious hierarchy is a “very attractive hypothesis”.” ref

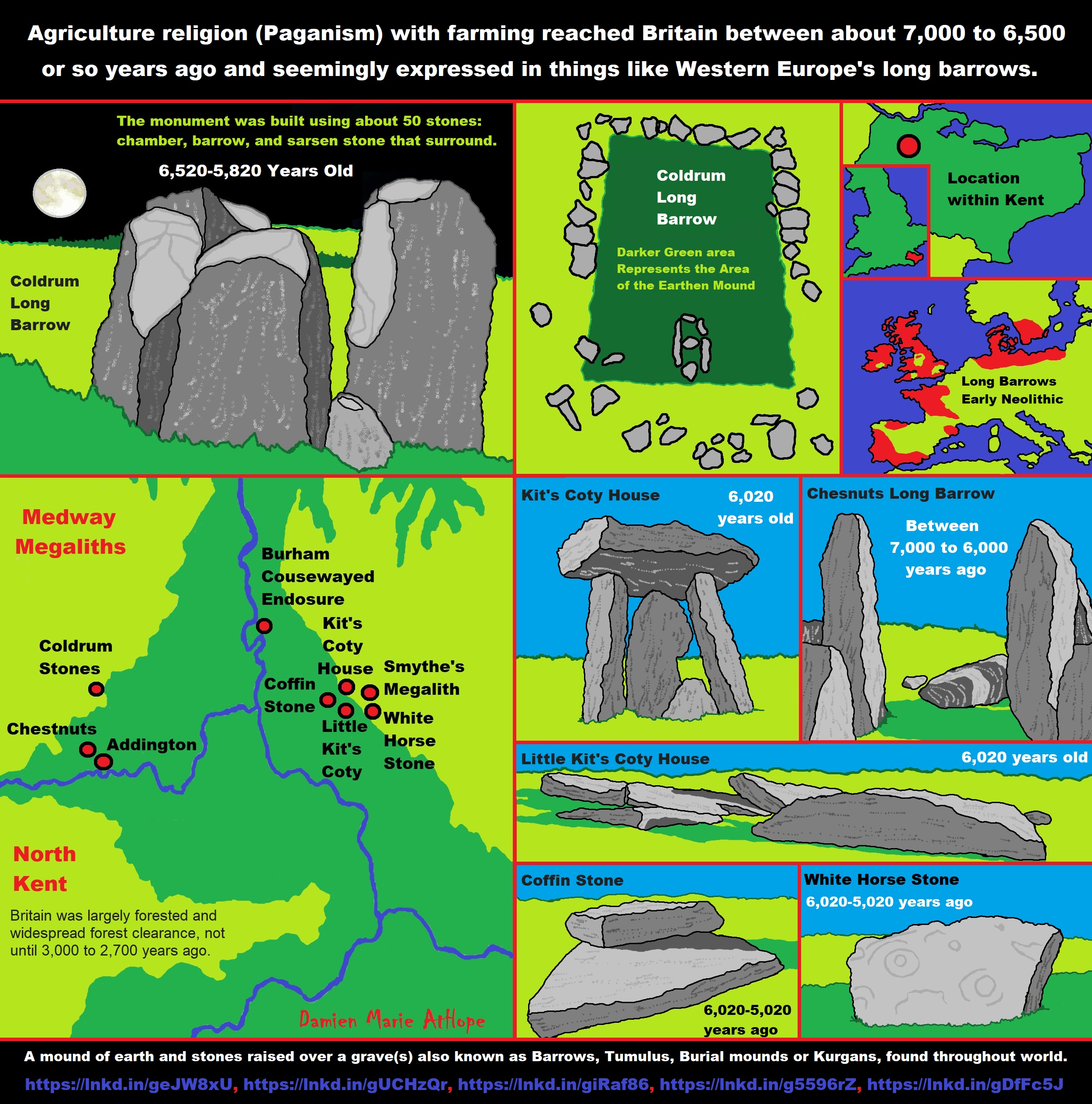

“Schulz Paulsson proposed that megalithic technology, which first appeared in Europe about 6,500 years ago, originated in Brittany and spread by maritime means along the coasts of the Atlantic and thus to England and Ireland. About 35,000 of these monuments are known, and the most famous draw crowds – sometimes for the history and archaeology, and sometimes for the spiritual power attributed to them. Schulz Paulsson says that essentially nothing is known about the structure of the societies that built the early megaliths. But the technology and the societies that used it developed over time. Newgrange dates to about 5,500 years ago, around 1,500 years after the first European megaliths appeared.” ref

“The creation of these monuments occurred after agriculture appeared in Europe, brought by a vast migration of Anatolian farmers, starting about 9,000 years ago. Reich is one of the researchers who has documented how these farmers, whose genetic profile is distinct from European hunter-gatherers, gradually settled Europe. What exactly happened between them and Indigenous hunter-gatherers is not known, but gradually, judging by modern and ancient DNA, those hunter-gatherers disappeared. Today, after many waves of migration, their DNA is found only as a faint remnant in modern populations.” ref

Genetic data may help delineate social structures of specific communities so lost in deep time that they have been almost impossible to decipher

“The Irish genomes show that the people in these tombs were descendants of Anatolian farmers. The researchers found a trace of the Indigenous population of Ireland in two individuals, Bradley says. Though this is a small amount, it does show, Bradley says, that there was an interaction between the farmers and hunter-gatherers. The paper is rich with other detail, including the discovery that an infant had Down syndrome.” ref

“The authors believe this is the oldest record of Down syndrome. Chemical tests of the bone also showed that the infant had been breastfed, and that he was placed in an important tomb. Both of those facts suggest that he was well cared for, in keeping with numerous other archaeological finds of children and adults with illnesses or disabilities who were supported by their cultures. Cassidy says they also found DNA in other remains that indicated relatives of the man who was a child of royal incest were placed in other significant tombs. “This man seemed to form a distinct genetic cluster with other individuals from passage tombs across the island,” she says.” ref

“She says “we also found a few direct kinship links”, ancient genomes of individuals who were distant cousins. That contributed to the idea that there was an elite who directed the building of the mounds. In that context, it made sense that the incest was intentional. That’s not something that can be proved, of course, but other societies have encouraged brother-sister incest, and not only the Egyptians. Brothers married sisters in ancient Hawaii, and in Peru among the Incas. “The few examples where it is socially accepted,” she says, are “extremely stratified societies with an elite class who are able to break rules.” ref

Relying on Folklore

“Reich says the research has implications beyond the specific findings. He says it signifies a new direction in ancient DNA studies, moving beyond discoveries of broad patterns of prehistoric human migration. Now, genetic data may help delineate social structures of specific communities, like that in Ireland, so lost in deep time that they have been almost impossible to decipher.” ref

“Reich says he has reservations about one of the paper’s conclusions. The researchers reported that members of the elite, those found in the most elaborate tombs, were closer to one another genetically than they were to people found in simpler burials. But, Reich says, the simpler burials and the higher-status burials were separated by hundreds of years, so the comparison wasn’t contemporaneous. Perhaps the genetic makeup of the society, which was small in number, changed over a few centuries. Bradley acknowledges that this was an alternative explanation.” ref

“The final piece of the puzzle that the researchers report is neither archaeological nor genetic, but folkloric. An account of Irish place names written around 1100, the authors write, tells a tale of a King Bressal, who slept with his sister. The result was that Dowth, the burial mound next to Newgrange, was called Fertae Chuile, or the Mound of Sin.” ref

“The idea that a folk memory could preserve history 4,000 years old may seem preposterous, but there were also folk tales that gods built the passage tombs to affect the solar cycle. And yet Newgrange, with its solar alignment, was covered by earth during the Middle Ages. It was excavated, and the orientation to the winter solstice discovered at the beginning of the 20th century. The myths may be muddled, but the tale of the solar cycle had some basis in fact, and so, it may be, did the story of royal incest.” ref

Claims of contact with Ecuador (South America)

“Similar pottery styles in Valdivia (Ecuador) & Jōmon (Japan)”

“A 2013 genetic study suggests the possibility of contact between Ecuador and East Asia. The study suggests that the contact could have been trans-oceanic or a late-stage coastal migration that did not leave genetic imprints in North America.” ref

Claims of Chinese contact with the Americas

“A jade Olmec mask from Central America. Gordon Ekholm, an archaeologist, and curator at the American Museum of Natural History, suggested that the Olmec art style might have originated in Bronze Age China. Other researchers have argued that the Olmec civilization came into existence with the help of Chinese refugees, particularly at the end of the Shang dynasty. In 1975, Betty Meggers of the Smithsonian Institution argued that the Olmec civilization originated around 1200 BCE due to Shang Chinese influences. In a 1996 book, Mike Xu, with the aid of Chen Hanping, claimed that celts from La Venta bear Chinese characters. These claims are unsupported by mainstream Mesoamerican researchers. Other claims have been made for early Chinese contact with North America. In 1882 approximately 30 brass coins, perhaps strung together, were reportedly found in the area of the Cassiar Gold Rush, apparently near Dease Creek, an area which was dominated by Chinese gold miners.” ref

A contemporary account states:

“In the summer of 1882 a miner found on De Foe (Deorse?) creek, Cassiar district, Br. Columbia, thirty Chinese coins in the auriferous sand, twenty-five feet below the surface. They appeared to have been strung, but on taking them up the miner let them drop apart. The earth above and around them was as compact as any in the neighborhood. One of these coins I examined at the store of Chu Chong in Victoria. Neither in metal nor markings did it resemble the modern coins, but in its figures looked more like an Aztec calendar. So far as I can make out the markings, this is a Chinese chronological cycle of sixty years, invented by Emperor Huungti, 2637 BCE or 4,657 years ago, and circulated in this form to make his people remember it.” ref

“Grant Keddie, Curator of Archeology at the Royal B.C. Museum identified these as good luck temple tokens minted in the 19th century. He believed that claims that these were very old made them notorious and that “The temple coins were shown to many people and different versions of stories pertaining to their discovery and age spread around the province to be put into print and changed frequently by many authors in the last 100 years.” A group of Chinese Buddhist missionaries led by Hui Shen before 500 CE claimed to have visited a location called Fusang. Although Chinese mapmakers placed this territory on the Asian coast, others have suggested as early as the 1800s that Fusang might have been in North America, due to perceived similarities between portions of the California coast and Fusang as depicted by Asian sources.” ref

“In his book 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, British author Gavin Menzies made the groundless claim that the fleet of Zheng He arrived in America in 1421. Professional historians contend that Zheng He reached the eastern coast of Africa, and dismiss Menzies’ hypothesis as entirely without proof. In 1973 and 1975, doughnut-shaped stones which resembled stone anchors which were used by Chinese fishermen were discovered off the coast of California. These stones (sometimes called the Palos Verdes stones) were initially thought to be up to 1,500 years old and therefore proof of pre-Columbian contact by Chinese sailors. Later geological investigations showed them to be made of a local rock which is known as Monterey shale, and they are thought to have been used by Chinese settlers who fished off the coast during the 19th century.” ref

Did China discover AMERICA?

Ancient Chinese script carved into rocks may prove Asians lived in New World 3,300 years ago

- Author and researcher John Ruskamp claims to have found pictograms from the ancient Chinese Shang Dynasty etched into rocks in America

- The symbols are carved into rocks in New Mexico, California and Arizona

- He says the Chinese were exploring North America long before Europeans

- He claims the symbols give details of journeys and honour the Shang king

“The discovery of the Americas has for centuries been credited to the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus, but ancient markings carved into rocks around the US could require history to be rewritten. Researchers have discovered ancient scripts that suggest Chinese explorers may have discovered America long before Europeans arrived there. They have found pictograms etched into the rocks around the country that appear to belong of an ancient Chinese script.” ref

Epigraph researcher John Ruskamp claims these symbols shown in the enhanced image above, found etched into rock at the Petroglyph National Monument in Albuquerque, New Mexico, are evidence that ancient Chinese explorers discovered America long before Christopher Columbus stumbled on the continent in 1492

“They say could have been inscribed there alongside the carvings of Native Americans by Chinese explorers thousands of years ago. John Ruskamp, a retired chemist and amateur epigraph researcher from Illinois, discovered the unusual markings while walking in the Petroglyph National Monument in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He claims they indicate ancient people from Asia were present in the Americas around 1,300BC – nearly 2,800 years before Columbus’s ships stumbled across the New World by reaching the Caribbean in 1492.” ref

ASIAN TRADERS BEAT COLUMBUS

“Trade was taking place between East Asia and the New World hundreds of years before Christopher Columbus arrived in the area in 1492. Archaeologists have made the suggestion following the discovery of a series of bronze artifacts found at the ‘Rising Whale’ site in Cape Espenberg, Alaska. They found what they believe to be a bronze and leather buckle and a bronze whistle, dating to around CE 600.” ref

Bronze-working had not been developed at this time in Alaska, and researchers instead believe the artifacts were created in China, Korea, or Yakutia. ‘We’re seeing the interactions, indirect as they are, with these so-called “high civilizations” of China, Korea or Yakutia,’ Owen Mason, a research associate at the University of Colorado. Researchers believe those who lived at the Rising Whale site may be part of what scientists call the ‘Birnirk’ culture. This is a group of people who lived on both sides of the Bering Strait and used skin boats and harpoons to hunt whales, LiveScience reports. The latest discovery of bronze artifacts backs up earlier evidence for trade between Alaska and other civilizations prior to 1492.” ref

“He said: ‘These ancient Chinese writings in North America cannot be fake, for the markings are very old as are the style of the scripts. ‘As such the findings of this scientific study confirm that ancient Chinese people were exploring and positively interacting with the Native peoples over 2,500 years ago. ‘The pattern of the finds suggests more of an expedition than settlement.’ However, his controversial views have been met with skepticism by many experts who point to the lack of archaeological evidence for any ancient Chinese presence in the New World. Mr Ruskamp is not the first to claim that the Chinese were the first to discover America – retired submarine lieutenant-commander Gavin Menzies claimed a fleet of Chinese ships sailed to North America in 1421, 70 years before Columbus’s expedition.” ref

“However, Mr Ruskamp believes the contact between the Chinese and Native Americans may have been going on for far longer. He claims to have identified 84 pictograms which match unique ancient Chinese sites in various locations around the US including New Mexico, California, Oklahoma, Utah, Arizona, and Nevada. He says many of these have been examined by experts on ancient Chinese scripts and they appear to forms of writing that went out of use thousands of years ago. The pictograms he discovered on the rocks of Albuquerque appear to be an ancient script that was used by the Chinese after the end Shang Dynasty. Known as oracle bone pictograms, Mr Ruskamp claims the markings record a ritual sacrificial offering perhaps made to the 3rd Shang dynasty king Da Jia and also a divination of an ‘auspicious’ 10-day sacred period.” ref

“With the help of experts on Neolithic Chinese culture, Mr Ruskamp has deciphered the pictograms he has discovered at Petroglyph National Monument in Albuquerque and claims they details a sacrificial offering of a dog to the 3rd Shang dynasty king Da Jai. Mr Ruskamp claims to have found evidence of ancient Chinese scripts etched into rocks in New Mexico, Nevada, and Arizona. Mr Ruskamp said: ‘Although only half of the symbols found on the large boulder in Albuquerque, New Mexico have been identified and confirmed as Chinese scripts, when the four central pictogram-glyphs of this message – Jie, Da, Quan, and Xian – are read in the traditional Chinese manner from right to left we learn about a respectful man honoring a superior with the sacrificial offering of a dog.” ref

“Notably, the written order of these symbols conforms with the syntax used for documenting ancient Chinese rituals during the Shang and Zhou dynasties, and dog sacrifices were very popular in the second part of the second millennium B.C. in China.’ He says he has also found ancient Chinese scripts for the number five and writing describing a boat upon water, which he found on the shore of Little Lake in California. Mr Ruskamp also claims the pictograms shown above, which were found carved into rocks in Arizona, also appear to belong to an ancient Chinese script. He believes Chinese explorers were conducting expeditions around North America thousands of years ago and left these markings as evidence of their presence.” ref

Mr Ruskamp first discovered ancient Chinese scripts at Petroglyph National Monument, n Albuquerque, New Mexico, alongside carvings made by Native Americans

“Mr Ruskamp says he has also found ancient Chinese scripts for dogs, flowers, and the earth scratched onto the rocks in Petroglyph National Monument. He also claims to have found a Chinese pictogram of an elephant dating to 500 BCE or 2,520 years ago in the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, suggesting the Asian explorers had spread across much of the US. Another pictogram found in Grapevine Canyon in Nevada, appears to be an oracle-bone era symbol for teeth dating to 1,300 BCE or 3,320 years ago. One ancient message, preserved in Arizona translates as: ‘Set apart (for) 10 years together; declaring (to) return, (the) journey completed, (to the) house of the Sun; (the) journey completed together.” ref

“At the end of this text is an unidentified character that may be the author’s signature. Mr Ruskamp said: ‘Here the intention of the ancient author was more to document an event than to leave a readable message.’ Mr Ruskamp says this cartouche, which forms part of a set found in Arizona, is an ancient Chinese symbol for ‘returning together’. He insists weathering on the markings and the age of the script suggest they are not fake. Mr Ruskamp has written a book and an academic paper on the topic, which is currently undergoing peer review. In it he claims the carvings appear to have undergone significant levels of weathering, known as repatination which indicate they were created long ago and not within the past 150 years.” ref

He says the Shang script disappeared from use around the fall of the Shang empire in 1046BC and were only rediscovered and deciphered in 1899 in China. Taken together this suggests the carvings are unlikely to be fakes, he insists. He also points to DNA evidence which has suggested Native Americans and Asian populations share many genetic traits. He said: ‘For centuries, researchers have been debating if, in pre-Columbian times, meaningful exchanges between the indigenous peoples of Asia and the Americas might have taken place. ‘Here is “rock solid” epigraphic proof that Asiatic explorers not only reached the Americas, but that they interacted positively with Native North American people, on multiple occasions, long before any European exploration of the continent.” ref

Mr Ruskamp has also managed to decipher the symbol above as an oracle-bone script for ‘Together for Ten Years’. It was found alongside other markings on a rock in Arizona

“His views are also beginning to be taken seriously by other academics and they echo some theories put forward by researchers such as Dr Dennis Stanford of the Smithsonian Institution, who believed North America was first populated by people from Asia during the last ice age. According to the Epoch Times, one of Mr Ruskamp’s staunchest supporters has been Dr David Keightley, an expert on Neolithic Chinese civilization at the University of California, Berkley. He has been helping to decipher the scripts found carved into the rocks. Dr Michael Medrano, chief of the Division of Resource Management for Petroglyph National Monument, has also studied the petroglyphs found by Mr Ruskamp. He told the Epoch Times: ‘These images do not readily appear to be associated with local tribal entities. ‘Based on repatination, they appear to have antiquity to them.” ref

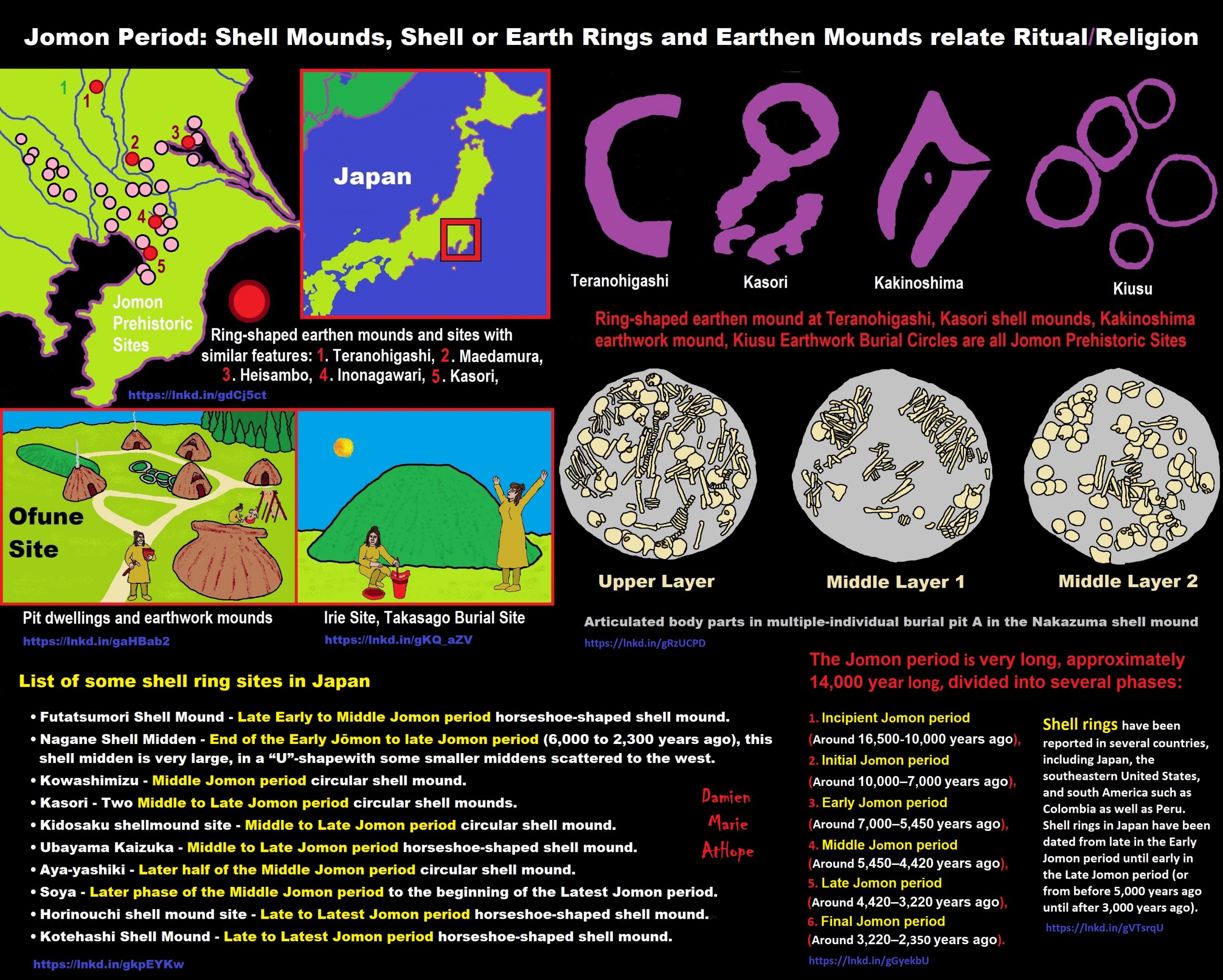

Claims of Japanese contact with the Americas

“Similar pottery styles in Valdivia (Ecuador) & Jōmon (Japan)”

“Archaeologist Emilio Estrada and co-workers wrote that pottery which was associated with the Valdivia culture of coastal Ecuador and dated to 3000–1500 BCE or 5,020-3,52- years ago exhibited similarities to pottery which was produced during the Jōmon period in Japan, arguing that contact between the two cultures might explain the similarities. Chronological and other problems have led most archaeologists to dismiss this idea as implausible. The suggestion has been made that the resemblances (which are not complete) are simply due to the limited number of designs possible when incising clay. Alaskan anthropologist Nancy Yaw Davis claims that the Zuni people of New Mexico exhibit linguistic and cultural similarities to the Japanese. The Zuni language is a linguistic isolate, and Davis contends that the culture appears to differ from that of the surrounding natives in terms of blood type, endemic disease, and religion. Davis speculates that Buddhist priests or restless peasants from Japan may have crossed the Pacific in the 13th century, traveled to the American Southwest, and influenced Zuni society.” ref

“In the 1890s, lawyer and politician James Wickersham argued that pre-Columbian contact between Japanese sailors and Native Americans was highly probable, given that from the early 17th century to the mid-19th century several dozen Japanese ships are known to have been carried from Asia to North America along the powerful Kuroshio Currents. Japanese ships landed at places between the Aleutian Islands in the north and Mexico in the south, carrying a total of 293 people in the 23 cases where head-counts were given in historical records. In most cases, the Japanese sailors gradually made their way home on merchant vessels. In 1834, a dismasted, rudderless Japanese ship was wrecked near Cape Flattery in the Pacific Northwest. Three survivors of the ship were enslaved by Makahs for a period before being rescued by members of the Hudson’s Bay Company. They were never able to return to their homeland due to Japan’s isolationist policy at the time. Another Japanese ship went ashore in about 1850 near the mouth of the Columbia River, Wickersham writes, and the sailors were assimilated into the local Native American population. While admitting there is no definitive proof of pre-Columbian contact between Japanese and North Americans, Wickersham thought it implausible that such contacts as outlined above would have started only after Europeans arrived in North America and began documenting them.” ref

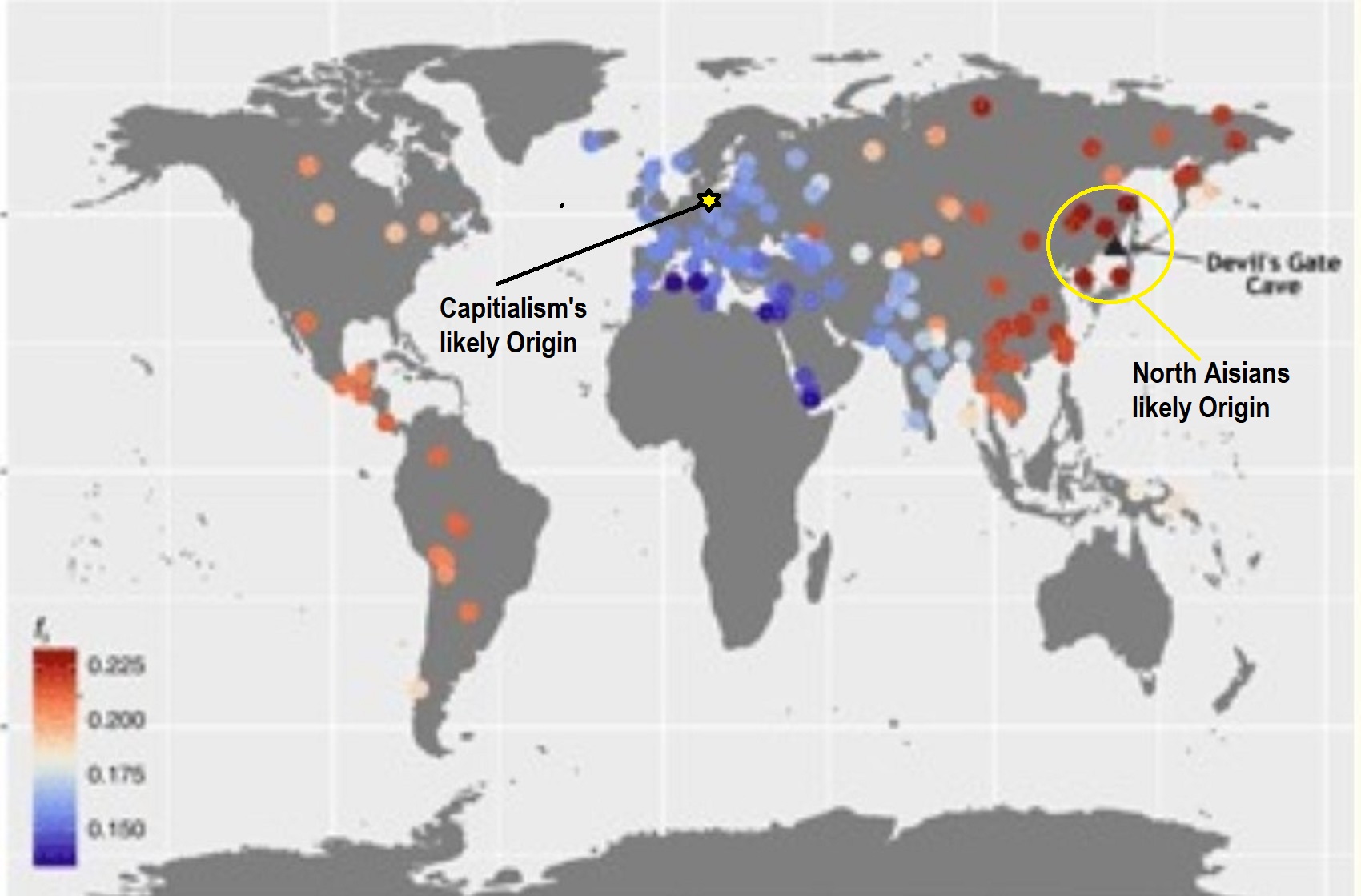

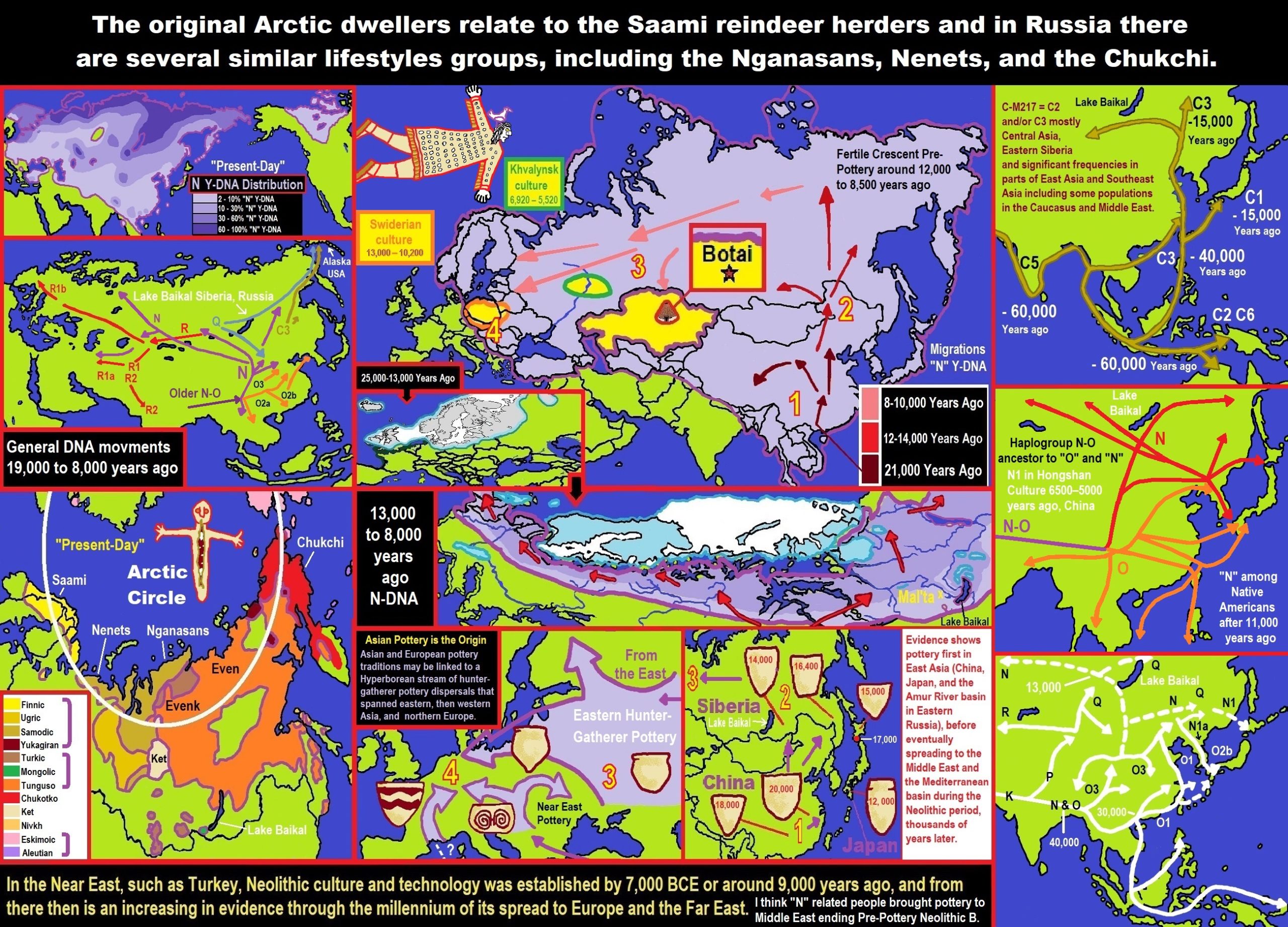

Genome-wide data from two early Neolithic East Asian individuals dating to 7700 years ago

Abstract

“Ancient genomes have revolutionized our understanding of Holocene prehistory and, particularly, the Neolithic transition in western Eurasia. In contrast, East Asia has so far received little attention, despite representing a core region at which the Neolithic transition took place independently ~3 millennia after its onset in the Near East. We report genome-wide data from two hunter-gatherers from Devil’s Gate, an early Neolithic cave site (dated to ~7.7 thousand years ago) located in East Asia, on the border between Russia and Korea. Both of these individuals are genetically most similar to geographically close modern populations from the Amur Basin, all speaking Tungusic languages, and, in particular, to the Ulchi. The similarity to nearby modern populations and the low levels of additional genetic material in the Ulchi imply a high level of genetic continuity in this region during the Holocene, a pattern that markedly contrasts with that reported for Europe.” ref

INTRODUCTION

“Ancient genomes from western Asia have revealed a degree of genetic continuity between preagricultural hunter-gatherers and early farmers 12 to 8 thousand years ago. In contrast, studies on southeast and central Europe indicate a major population replacement of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers by Neolithic farmers of a Near Eastern origin during the period 8.5 to 7 ka. This is then followed by a progressive “resurgence” of local hunter-gatherer lineages in some regions during the Middle/Late Neolithic and Eneolithic periods and a major contribution from the Asian Steppe later, ~5.5 ka, coinciding with the advent of the Bronze Age. Compared to western Eurasia, for which hundreds of partial ancient genomes have already been sequenced, East Asia has been largely neglected by ancient DNA studies to date, with the exception of the Siberian Arctic belt, which has received attention in the context of the colonization of the Americas.” ref

“However, East Asia represents an extremely interesting region as the shift to reliance on agriculture appears to have taken a different course from that in western Eurasia. In the latter region, pottery, farming, and animal husbandry were closely associated. In contrast, Early Neolithic societies in the Russian Far East, Japan, and Korea started to manufacture and use pottery and basketry 10.5 to 15 ka, but domesticated crops and livestock arrived several millennia later. Because of the current lack of ancient genomes from East Asia, we do not know the extent to which this gradual Neolithic transition, which happened independently from the one taking place in western Eurasia, reflected actual migrations, as found in Europe, or the cultural diffusion associated with population continuity.” ref

“To fill this gap in our knowledge about the Neolithic in East Asia, we sequenced to low coverage the genomes of five early Neolithic burials (DevilsGate1, 0.059-fold coverage; DevilsGate2, 0.023-fold coverage; and DevilsGate3, DevilsGate4, and DevilsGate5, <0.001-fold coverage) from a single occupational phase at Devil’s Gate (Chertovy Vorota) Cave in the Primorye Region, Russian Far East, close to the border with China and North Korea (see the Supplementary Materials). This site dates back to 9.4 to 7.2 ka, with the human remains dating to ~7.7 ka, and it includes some of the world’s earliest evidence of ancient textiles. The people inhabiting Devil’s Gate were hunter-fisher-gatherers with no evidence of farming; the fibers of wild plants were the main raw material for textile production. We focus our analysis on the two samples with the highest sequencing coverage, DevilsGate1, and DevilsGate2, both of which were female.” ref

“The mitochondrial genome of the individual with higher coverage (DevilsGate1) could be assigned to haplogroup D4; this haplogroup is found in present-day populations in East Asia and has also been found in Jomon skeletons in northern Japan. For the other individual (DevilsGate2), only membership to the M branch (to which D4 belongs) could be established. Contamination, estimated from the number of discordant calls in the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequence, was low {0.87% [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.28 to 2.37%] and 0.59% (95% CI, 0.03 to 3.753%)} on nonconsensus bases at haplogroup-defining positions for DevilsGate1 and DevilsGate2, respectively. Using schmutzi on the higher-coverage genome, DevilsGate1 also gives low contamination levels [1% (95% CI, 0 to 2%); see the Supplementary Materials]. As a further check against the possible confounding effect of contamination, we made sure that our most important analyses [outgroup f3 scores and principal components analysis (PCA)] were qualitatively replicated using only reads showing evidence of postmortem damage (PMD score of at least 3), although these latter results had a high level of noise due to the low coverage (0.005X for DevilsGate1 and 0.001X for DevilsGate2).” ref

Devils Gate area people Relation to modern populations

“We compared the individuals from Devil’s Gate to a large panel of modern-day Eurasians and to published ancient genomes (Fig). On the basis of PCA and an unsupervised clustering approach, ADMIXTURE, both individuals fall within the range of modern variability found in populations from the Amur Basin, the geographic region where Devil’s Gate is located (Fig), and which is today inhabited by speakers from a single language family (Tungusic). This result contrasts with observations in western Eurasia, where, because of a number of major intervening migration waves, hunter-gatherers of a similar age fall outside modern genetic variation. We further confirmed the affinity between Devil’s Gate and modern-day Amur Basin populations by using outgroup f3 statistics in the form f3(African; DevilsGate, X), which measures the amount of shared genetic drift between a Devil’s Gate individual and X, a modern or ancient population, since they diverged from an African outgroup.” ref

“Modern populations that live in the same geographic region as Devil’s Gate have the highest genetic affinity to our ancient genomes (Fig), with a progressive decline in affinity with increasing geographic distance (r2 = 0.756, F1,96 = 301, P < 0.001; Fig), in agreement with neutral drift leading to a simple isolation-by-distance pattern. The Ulchi, traditionally fishermen who live geographically very close to Devil’s Gate and are the only Tungusic-speaking population from the Amur Basin sampled in Russia (all other Tungusic speakers in our panel are from China), are genetically the most similar population in our panel. Other populations that show high affinity to Devil’s Gate are the Oroqen and the Hezhen—both of whom, like the Ulchi, are Tungusic speakers from the Amur Basin—as well as modern Koreans and Japanese. Given their geographic distance from Devil’s Gate (Fig), Amerindian populations are unusually genetically close to samples from this site, in agreement with their previously reported relationship to Siberian and other north Asian populations.” ref

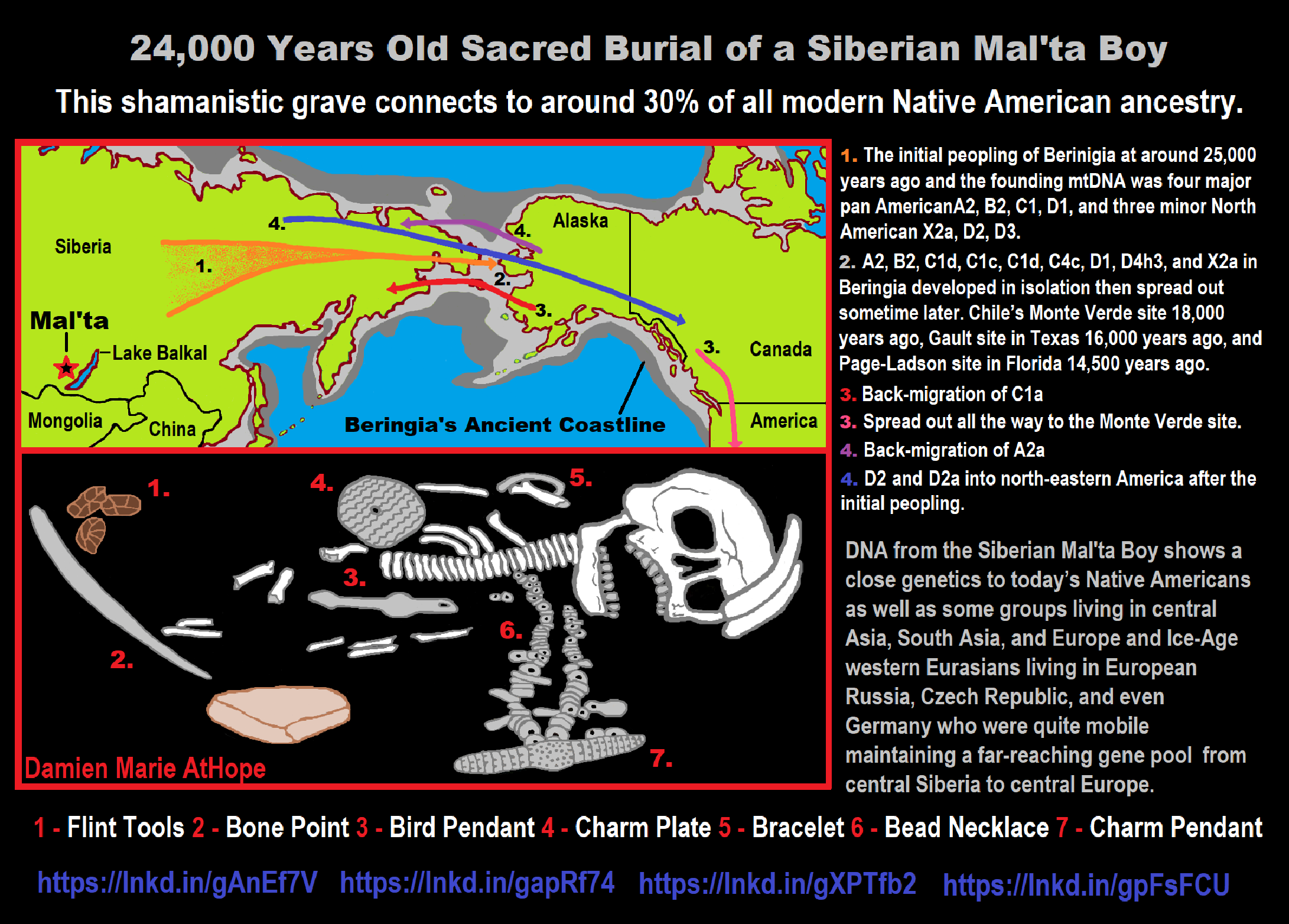

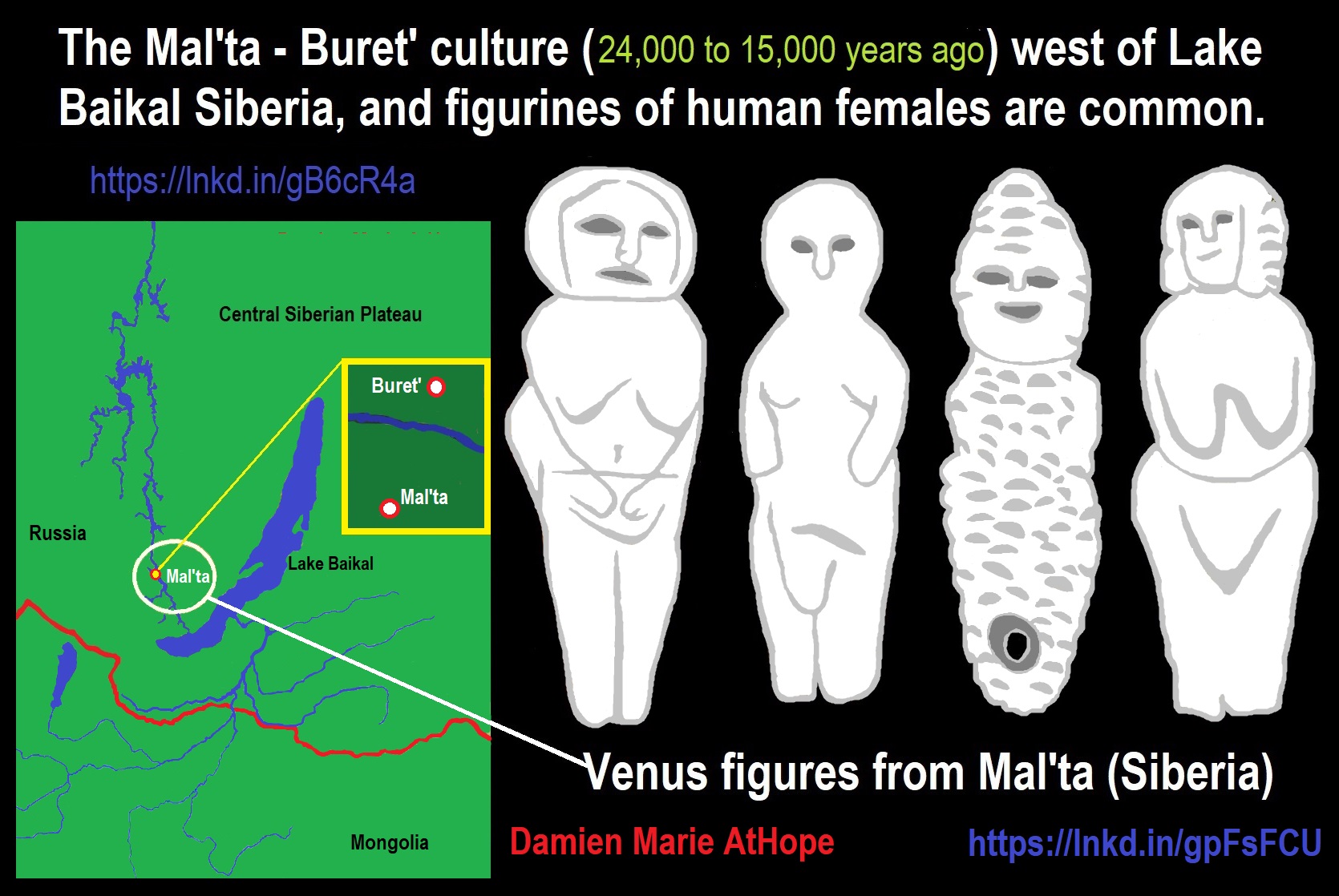

“No previously published ancient genome shows marked genetic affinity to Devil’s Gate: The top 50 populations in our outgroup f3 statistic were all modern, an expected result given that all other ancient genomes are either geographically or temporally very distant from Devil’s Gate. Among these ancient genomes, the closest to Devil’s Gate are those from Steppe populations dating from the Bronze Age onward and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from Europe, but these genomes are no closer to the Devil’s Gate genomes than to genomes of modern populations from the same regions (for example, Tuvinian, Kalmyk, Russian, or Finnish). The two ancient genomes geographically closest to Devil’s Gate, Ust’-Ishim (~45,000 years ago) and Mal’ta (MA1, 24,000 years ago), also do not show high genetic affinity, probably because they both date to a much earlier time period. Of the two, MA1 is genetically closer to Devil’s Gate, but it is equally as distant from Devil’s Gate as it is from all other East Asians. A similar pattern is found for Ust’-Ishim, which is equally as distant to all Asians, including Devil’s Gate; this is consistent with its basal position in a genealogical tree.” ref

Continuity between Devil’s Gate and the Ulchi

“Because Devil’s Gate falls within the range of modern human genetic variability in the Amur Basin in a number of analyses and shows a high genetic affinity to the Ulchi, we investigated the extent of genetic continuity in this region. To look for signals of additional genetic material in the Ulchi, we modeled them as a mixture of Devil’s Gate and other modern populations using admixture f3 statistics. Despite a large panel of possible modern sources, the Ulchi are best represented by Devil’s Gate alone without any further contribution. Because admixture f3 can be affected by demographic events such as bottlenecks, we also tested whether Devil’s Gate formed a clade with the Ulchi using a D statistic in the form D(African outgroup, X; Ulchi, Devil’s Gate). A number of primarily modern populations worldwide gave significantly nonzero results (|z| > 2), which, together with the additional components for the Ulchi in the ADMIXTURE analysis, suggests that the continuity is not absolute. However, it should be noted that the higher error rates in the Devil’s Gate sequence resulting from DNA degradation and low coverage can also decrease the inferred level of continuity. To compare the level of continuity between the Ulchi and the inhabitants of Devil’s Gate to that between modern Europeans and European hunter-gatherers, we compared their ancestry proportions as inferred by ADMIXTURE. We found that the proportion of Devil’s Gate–related ancestry in the Ulchi was significantly higher than the local hunter–gatherer–related ancestry in any European population (P < 0.01 from 100 bootstrap replicates for the five European populations with the highest mean hunter-gatherer–related component).” ref

“These results suggest a relatively high degree of continuity in this region; the Ulchi are likely descendants of Devil’s Gate (or a population genetically very close to it), but the geographic and genetic connectivity among populations in the region means that this modern population also shows increased association with related modern populations. Compared to Europe, these results suggest a higher level of genetic continuity in northern East Asia over the last ~7.7 thousand years (ky), without any major population turnover since the early Neolithic.” ref

The southern and northern genetic material in the Japanese and the Koreans

“The close genetic affinity between Devil’s Gate and modern Japanese and Koreans, who live further south, is also of interest. It has been argued, based on both archaeological and genetic analyses, that modern Japanese have a dual origin, descending from an admixture event between hunter-gatherers of the Jomon culture (16,000 to 3,000 years ago) and migrants of the Yayoi culture (3 to 1.7 ka), who brought wet rice agriculture from the Yangtze estuary in southern China through Korea. The few ancient mtDNA samples available from Jomon sites on the northern Hokkaido island show an enrichment of particular haplotypes (N9b and M7a, with D1, D4, and G1 also detected) present in modern Japanese populations, particularly the Ainu and Ryukyuans, as well as southern Siberians (for example, Udegey and Ulchi). The mtDNA haplogroups of our samples from Devil’s Gate (D4 and M) are also present in Jomon samples, although they are not the most common ones (N9b and M7a). Recently, nuclear genetic data from two Jomon samples also confirmed the dual origin hypothesis and implied that the Jomon diverged before the diversification of present-day East Asians.” ref

“We investigated whether it was possible to recover the Northern and Southern genetic components by modeling modern Japanese as a mixture of all possible pairs of sources, including both modern Asian populations and Devil’s Gate, using admixture f3 statistics. The clearest signal was given by a combination of Devil’s Gate and modern-day populations from Taiwan, southern China, and Vietnam (Fig), which could represent hunter-gatherer and agriculturalist components, respectively. However, it is important to note that these scores were just barely significant (−3 < z < −2) and that some modern pairs also gave negative scores, even if not reaching our significance threshold (z scores as low as −1.9; see the Supplementary Materials).” ref

“The origin of Koreans has received less attention. Also, because of their location on the mainland, Koreans have likely experienced a greater degree of contact with neighboring populations throughout history. However, their genomes show similar characteristics to those of the Japanese on genome-wide SNP data and have also been shown to harbor both northern and southern Asian mtDNA and Y chromosomal haplogroups. Unfortunately, our low coverage and small sample size from Devil’s Gate prevented a reliable estimate of admixture coefficients or use of linkage disequilibrium–based methods to investigate whether the components originated from secondary contact (admixture) or continuous differentiation and to date any admixture event that did occur.” ref

Devil’s Gate overall DISCUSSION

“By analyzing genome-wide data from two early Neolithic East Asians from Devil’s Gate, in the Russian Far East, we could demonstrate a high level of genetic continuity in the region over at least the last 7700 years. The cold climatic conditions in this area, where modern populations still rely on a number of hunter-gatherer-fisher practices, likely provide an explanation for the apparent continuity and lack of major genetic turnover by exogenous farming populations, as has been documented in the case of southeast and central Europe. Thus, it seems plausible that the local hunter-gatherers progressively added food-producing practices to their original lifestyle. However, it is interesting to note that in Europe, even at very high latitudes, where similar subsistence practices were still important until very recent times, the Neolithic expansion left a significant genetic signature, albeit attenuated in modern populations, compared to the southern part of the continent. Our ancient genomes thus provide evidence for a qualitatively different population history during the Neolithic transition in East Asia compared to western Eurasia, suggesting stronger genetic continuity in the former region. These results encourage further study of the East Asian Neolithic, which would greatly benefit from genetic data from early agriculturalists (ideally, from areas near the origin of wet rice cultivation in southern East Asia), as well as higher-coverage hunter-gatherer samples from different regions to quantify population structure before intensive agriculture.Devil’s Gate

Genome-wide data relating to people from Devil’s Gate Cave in Primorsky Krai, Russia

Chertovy Vorota Cave/Devil’s Gate Cave

“Chertovy Vorota Cave (known as Devil’s Gate Cave in English) is a Neolithic archaeological site located in the Sikhote-Alin mountains, about 12 km (7 mi) from the town of Dalnegorsk in Primorsky Krai, Russia. The karst cave is located on a limestone cliff and lies about 35 m (115 ft) above the Krivaya River, a tributary of the Rudnaya River, below. Chertovy Vorota provides secure evidence for some of the oldest surviving textiles found in the archaeological record. The cave consists of a main chamber, measuring around 45 m (148 ft) in length, and several smaller galleries behind it. The site was looted several times before the first archaeological excavations were performed in 1973. Around 600 lithic, osteological, and shell artifacts, 700 pottery fragments, and over 700 animal bones were recovered from the site. A .6 cm thick jade disk made from brownish-green jade and measuring 5.2 cm (2 in) in diameter was also recovered from Chertovy Vorota. The remains of racoon dog, brown bear, Asian black bear, wild boar, badger, red deer, fish, and mollusc shells were found inside the cave.

Diet of the Devil’s Gate Cave people

“The isotopic analysis shows that the people of Chertovy Vorota likely derived their protein from a mix of terrestrial and maritime sources; around 25% of their dietary protein appears to have been derived from maritime resources, most likely from anadromous salmon. The people of Chertovy Vorota likely hunted terrestrial mammals, collected nuts, and fished salmon to provide for their food needs.

Ancient textiles[edit]

The remains of carbonized textile fragments were found within the cave, under the remains of a wooden structure that had caught on fire and collapsed. The carbonized remains of rope, nets, and woven fabrics were recovered from the cave. The fibers likely came from Carex sordida, a sedge grass from the family Cyperaceae. The textile remains were directly dated to around 9400-8400 BP, the earliest evidence in the archaeological record for textile remains from East Asia. As spindle whorls were not found in the cave, and also rarely found in contemporary East Asian sites, archaeologists postulate that the people at Chertovy Vorota either produced their textiles by hand or through the use of warp-weighted looms.

Devil’s Gate Cave Human remains

“The remains of 7 individuals were discovered within the cave. The skulls of two of the individuals, DevilsGate1 and DevilsGate2, were directly dated to around 5726-5622 BCE. Six of seven individuals whose remains have been recovered from the cave have been DNA tested. Originally, three of the specimens were thought to be adult males, two were thought to be adult females, one was thought to be a sub-adult of about 12-13 years of age, and one was thought to be a juvenile of about 6-7 years of age based on the skeletal morphology of the remains. Results of genetic analysis of the sub-adult individual have not yet been published. However, two specimens, NEO236 (Skull B, DevilsGate2) and NEO235 (Skull G), who had been presumed to be adult males according to a forensic morphological assessment of their remains, were discovered through genetic analysis to actually be females.” ref

“The juvenile specimen also has been determined to be female through genetic analysis. Three of the specimens (including the only adult male plus NEO235/Skull G and another adult female, labeled as Skull Е, DevilsGate1, or NEO240, who has been genetically determined to be a first-degree relative of NEO235/Skull G) have been assigned to mtDNA haplogroup D4m; a previous genetic analysis of one of these adult female specimens determined her mtDNA haplogroup to be D4.” ref

“Another three specimens (including the juvenile female, the DevilsGate2 specimen, and another adult female; both the juvenile female and the DevilsGate2 specimen have been determined to be first-degree relatives of the other adult female, and the juvenile female and the DevilsGate2 specimen also have been determined to be second-degree relatives of each other) have been assigned to haplogroup D4; a previous genetic analysis of the DevilsGate2 specimen determined her mtDNA haplogroup to be M. The only specimen from the cave who has been confirmed to be male through genetic analysis has been assigned to Y-DNA haplogroup C2b-F6273/Y6704/Y6708, equivalent to C2b-L1373, the northern (Central Asian, Siberian, and indigenous American) branch of haplogroup C2-M217.” ref

“When compared against all populations on record, ancient or modern, the ancient Chertovy Vorota individuals were found to be genetically closest to the contemporary Ulchi, speakers of a Tungusic language from the lower Amur Basin. The DevilsGate1 and DevilsGate2 specimens were also found to be close to the Hezhen and Oroqen, two other contemporary Tungusic-speaking populations from the basin of the Amur River, as well as contemporary Koreans and Nganasans. When compared against an outgroup from southern Africa (Khomani), outgroup f3 statistics indicate that DevilsGate1 and DevilsGate2 exhibit greatest shared drift with representatives of the same six populations, though in slightly different rank order: DevilsGate1 shares greatest drift with Ulchi followed in order by Oroqen, Hezhen, Korean and Nganasan, whereas DevilsGate2 shares greatest drift with Ulchi followed in order by Nganasan, Hezhen, Korean and Oroqen.” ref

“The outgroup f3 statistics also reveal a tendency for the DevilsGate2 specimen to exhibit slightly greater shared drift with contemporary populations than the DevilsGate1 specimen shares with contemporary populations. The ancient Chertovy Vorota individuals are genetically closest to the Ulchi, followed by the Oroqen and Hezhen. The genetic distance from the ancient Chertovy Vorota individuals to Mal’ta boy is the same as that from modern East Asian populations to Mal’ta boy.” ref

“With the exception of DevilsGate1, most of the individuals tested did not yield enough DNA to allow for phenotypic testing of traits. DevilsGate1 did not carry the derived SLC45A2 or SLC24A5 alleles associated with lighter skin color, the derived HERC2 allele associated with blue eyes, the derived LT allele associated with lactase persistence, or the derived ALDH2 allele associated with the alcohol flush reaction.[2] However, the individual likely did carry the derived EDAR allele commonly found in modern East Asian populations, the derived ABCC11 allele associated with dry earwax and reduced body odor commonly found in modern East Asian populations, and the derived ADD1 allele associated with increased risk for hypertension.” ref

Confirmation of Y haplogroup tree topologies with newly suggested Y-SNPs for the C2, O2b, and O3a subhaplogroups

“Based on the outcomes, the C2 haplogroup defined by M217 was classified into two main sub-clades, C2b-L1373 and C2e-Z1338. Then, C2e was further sub-classified into four subhaplogroups, C2el-Z1300, C2e1a-CTS2657, C2e1b-Z8440 and C2e2-F845.” ref

Haplogroup C3* – Previously Believed East Asian Haplogroup is Proven Native American

“In a paper, “Insights into the origin of rare haplogroup C3* Y chromosomes in South America from high-density autosomal SNP genotyping,” by Mezzavilla et al, research shows that haplogroup C3* (M217, P44, Z1453), previously believed to be exclusively East Asian, is indeed, Native American. Subgroup C-P39 (formerly C3b) was previously proven to be Native and is found primarily in the eastern US and Canada although it was also reported among the Na-Dene in the 2004 paper by Zegura et all titled “High-resolution SNPs and microsatellite haplotypes point to a single recent entry of Native American Y chromosomes into the Americas.” ref

“The discovery of C3* as Native is great news, as it more fully defines the indigenous American Y chromosome landscape. It also is encouraging in that several mitochondrial haplogroups, including variants of M, have also been found in Central and South America, also not previously found in North America and also only previously found in Asia, Polynesia, and even as far away as Madagascar. They too had to come from someplace and desperately need additional research of this type.” ref

“There is a great deal that we don’t know today that remains to be discovered. As in the past, what is thought to be fact doesn’t always hold water under the weight of new discoveries – so it’s never wise to drive a stake too far in the ground in the emerging world of genetics. You can view the Y DNA projects for C-M217 here, C-P39 here, and the main C project here. Please note that on the latest version of the ISOGG tree, M217, P44, and Z1453 are now listed as C2, not C3. Also, note that I added the SNP names in this article. The Mezzavilla paper references the earlier C3 type naming convention which I have used in discussing their article to avoid confusion.” ref

“In the Messavilla study, fourteen individuals from the Kichwa and Waorani populations of South America were discovered to carry haplogroup C3*. Most of the individuals within these populations carry variants of expected haplogroup Q, with the balance of 26% of the Kichwa samples and 7.5% of the Waorani samples carrying C3*. MRCA estimates between the groups are estimated to be between 5.0-6.2 KYA, or years before present. Other than one C3* individual in Alaska, C3* is unknown in the rest of the Native world including all of North American and the balance of Central and South America, but is common and widespread in East Asia.” ref

In the paper, the authors state that:

“We set out to test whether or not the haplogroup C3* Y chromosomes found at a mean frequency of 17% in two Ecuadorian populations could have been introduced by migration from East Asia, where this haplogroup is common. We considered recent admixture in the last few generations and, based on an archaeological link between the middle Jōmon culture in Japan and the Valdivia culture in Ecuador, a specific example of ancient admixture between Japan and Ecuador 6 Kya.” ref

“In a paper, written by Estrada et all, titled “Possible Transpacific Contact on the Cost of Ecuador”, Estrada states that the earliest pottery-producing culture on the coast of Ecuador, the Valdivia culture, shows many striking similarities in decoration and vessel shape to the pottery of eastern Asia. In Japan, resemblances are closest to the Middle Jomon period. Both early Valdivia and Middle Jomon are dated between 2000 and 3000 BCE. A transpacific contact from Asia to Ecuador during this time is postulated.” ref

This of course, opens the door for Asian haplogroups not found elsewhere to be found in Ecuador.

“The introduction of the Mezzabilla paper states: The consensus view of the peopling of the Americas, incorporating archaeological, linguistic, and genetic evidence, proposes colonization by a small founder population from Northeast Asia via Beringia 15–20 Kya (thousand years ago), followed by one or two additional migrations also via Alaska, contributing only to the gene pools of North Americans, and little subsequent migration into the Americas south of the Arctic Circle before the voyages from Europe initiated by Columbus in 1492.” ref

“In the most detailed genetic analysis thus far, for example, Reich and colleagues identified three sources of Native American ancestry: a ‘First American’ stream contributing to all Native populations, a second stream contributing only to Eskimo-Aleut-speaking Arctic populations, and a third stream contributing only to a Na-Dene-speaking North American population.” ref

“Nevertheless, there is strong evidence for additional long-distance contacts between the Americas and other continents between these initial migrations and 1492. Norse explorers reached North America around 1000 CE and established a short-lived colony, documented in the Vinland Sagas and supported by archaeological excavations. The sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) was domesticated in South America (probably Peru), but combined genetic and historical analyses demonstrate that it was transported from South America to Polynesia before 1000–1100 CE. Some inhabitants of Easter Island (Rapa Nui) carry HLA alleles characteristic of South America, most readily explained by gene flow after the colonization of the island around 1200 CE but before European contact in 1722.” ref

“In Brazil, two nineteenth-century Botocudo skulls carrying the mtDNA Polynesian motif have been reported, and a Pre-Columbian date for entry of this motif into the Americas discussed, although a more recent date was considered more likely. Thus South America was in two-way contact with other continental regions in prehistoric times, but there is currently no unequivocal evidence for outside gene flow into South America between the initial colonization by the ‘First American’ stream and European contact.” ref

“The researchers originally felt that the drift concept, which means that the line was simply lost to time in other American locations outside of Ecuador, was not likely because the populations of North and Central America have in general experienced less drift and retained more diversity than those in South America.” ref

“The paper abstract states: The colonization of Americas is thought to have occurred 15–20 thousand years ago (Kya), with little or no subsequent migration into South America until the European expansions beginning 0.5 Kya. Recently, however, haplogroup C3* Y chromosomes were discovered in two nearby Native American populations from Ecuador. Since this haplogroup is otherwise nearly absent from the Americas but is common in East Asia, and an archaeological link between Ecuador and Japan is known from 6 Kya, an additional migration 6 Kya was suggested.” ref

“Here, the generated high-density autosomal SNP genotypes from the Ecuadorian populations and compared them with genotypes from East Asia and elsewhere to evaluate three hypotheses: a recent migration from Japan, a single pulse of migration from Japan 6 Kya, and no migration after the First Americans. First, using forward-time simulations and an appropriate demographic model, we investigated our power to detect both ancient and recent gene flow at different levels. Second, we analyzed 207,321 single nucleotide polymorphisms from 16 Ecuadorian individuals, comparing them with populations from the HGDP panel using descriptive and formal tests for admixture. Our simulations revealed good power to detect recent admixture, and that ≥5% admixture 6 Kya ago could be detected.” ref

“However, in the experimental data we saw no evidence of gene flow directly from Japan to Ecuador. In summary, we can exclude recent migration and probably admixture 6 Kya as the source of the C3* Y chromosomes in Ecuador, and thus suggest that they represent a rare founding lineage lost by drift elsewhere.” ref

The conclusions from the paper states that:

“Three different hypotheses to explain the presence of C3* Y chromosomes in Ecuador but not elsewhere in the Americas were tested: recent admixture, ancient admixture ∼6 Kya, or entry as a founder haplogroup 15–20 Kya with subsequent loss by drift elsewhere. We can convincingly exclude the recent admixture model, and find no support for the ancient admixture scenario, although cannot completely exclude it. Overall, our analyses support the hypothesis that C3* Y chromosomes were present in the “First American” ancestral population, and have been lost by drift from most modern populations except the Ecuadorians. It will be interesting as additional people are tested and more ancient DNA is discovered and processed to see what other haplogroups will be found in Native people and remains that were previously thought to be exclusively Asian, or perhaps even African or European.” ref

“This discovery also begs a different sort of question that will eventually need to be answered. Clearly, we classify the descendants of people who arrived with the original Beringian and subsequent wave migrants as Native American, Indigenous American, or First Nations. However, how would we classify these individuals if they had arrived 6000 years ago, or 2000 years ago – still before Columbus or significant European or African admixture – but not with the first wave of Asian founders? If found today in South Americans, could they be taken as evidence of Native American heritage? Clearly, in this context, yes – as opposed to African or European. Would they still be considered only Asian or both Asian and Native American in certain contexts – as is now the case for haplogroup C3* (M217)? This scenario happening in 2014 could easily and probably will happen with other haplogroups as well.” ref

Thunderbird (mythology)

“The thunderbird is a legendary creature in certain North American indigenous peoples’ history and culture. It is considered a supernatural being of power and strength. Pacific NW (Haida) imagery of a double thunderbird. It is especially important, and frequently depicted, in the art, songs, and oral histories of many Pacific Northwest Coast cultures, but is also found in various forms among some peoples of the American Southwest, East Coast of the United States, Great Lakes, and Great Plains. The thunderbird is said to create thunder by flapping its wings (Algonqian, ), and lightning by flashing its eyes (Algonquian, Iroquois.)

Algonquian

Mississaugas, Ho-Chunk, Menominee

Tribal signatures using thunderbirds on the Great Peace of Montreal.

‘”The thunderbird myth and motif is prevalent among Algonquian peoples in the “Northeast”, i.e., Eastern Canada (Ontario, Quebec, and eastward) and Northeastern United States, and the Iroquois peoples (surrounding the Great Lakes). The discussion of the “Northeast” region has included Algonquian-speaking people in the Lakes-bordering U.S. Midwest states (e.g., Ojibwe in Minnesota). In Algonquian mythology, the thunderbird controls the upper world while the underworld is controlled by the underwater panther or Great Horned Serpent. The thunderbird creates not just thunder (with its wing-flapping), but lightning bolts, which it cast at the underworld creatures. Thunderbirds in this tradition may be depicted as a spread-eagled bird (wings horizontal head in profile), but also quite commonly with the head facing forward, thus presenting an X-shaped appearance overall (see under §Iconography below).” ref

Ojibwe

“The Ojibwe version of the myth states that the thunderbirds were created by Nanabozho for the purpose of fighting the underwater spirits. They were also used to punish humans who broke moral rules. The thunderbirds lived in the four directions and arrived with the other birds in the springtime. In the fall they migrated south after the ending of the underwater spirits’ most dangerous season.” ref

Menominee

Seal of the Menominee Nation featuring a thunderbird

“The Menominee of Northern Wisconsin tell of a great mountain that floats in the western sky on which dwell the thunderbirds. They control the rain and hail and delight in fighting and deeds of greatness. They are the enemies of the great horned snakes (the Misikinubik) and have prevented these from overrunning the earth and devouring mankind. They are messengers of the Great Sun himself. Thunderbird from the Great Lakes region. The thunderbird motif is also seen in Siouan-speaking peoples, which include tribes traditionally occupying areas around the Great Lakes.” ref

Ho-Chunk

“Ho-Chunk tradition states that a man who has a vision of a thunderbird during a solitary fast will become a war chief of the people.” ref

Iconography

Crest of the Anishinaabe

X-shapes

“In Alogonquian images, an X-shaped thunderbird is often used to depict the thunderbird with its wings alongside its body and the head facing forwards instead of in profile. The depiction may be stylized and simplified. A headless X-shaped thunderbird was found on an Ojibwe midewiwin disc dating to 1250–1400 CE. In an 18th century manuscript (a “daybook” ledger) written by the namesake grandson of Governor Matthew Mayhew, the thunderbird pictograms varies from a “recognizable birds to simply an incised X”.” ref

In modern usage

“Thunderbird at the top of the totem pole in front of Wawadit’la, a Kwakwaka’wakw First Nation big house built by Chief Mungo Martin in 1953, located at Thunderbird Park in Victoria, BC. In 1925, Aleuts were recorded as using the term to describe the Douglas World Cruiser aircraft which passed through Atka on the first aerial circumnavigation by a US Army team the previous year. In one of his speeches, which took place few days before the Iranian revolution, Shapour Bakhtiar, the last Prime Minister of Imperial Iran, said: “I am a thunderbird. I am not afraid of the storm”.[a] Due to this, Bakhtiar is known as the Thunderbird.” ref

Ancient DNA Yields Unprecedented Insights into Mysterious Chaco Civilization

“The results suggest that a maternal “dynasty” ruled the society’s greatest mansion for more than 300 years, but concerns over research ethics cast a shadow on the technical achievement.” ref

Valdivia culture

“The Valdivia culture is one of the oldest settled cultures recorded in the Americas. It emerged from the earlier Las Vegas culture and thrived on the Santa Elena peninsula near the modern-day town of Valdivia, Ecuador between 3500 BCE and 1500 BCE. Remains of the Valdivia culture were discovered in 1956 on the western coast of Ecuador by the Ecuadorian archeologist Emilio Estrada, who continued to study this culture. American archeologists Clifford Evans and Betty Meggers joined him in the early 1960s in studying the type-site.” ref

“The Valdivia lived in a community that built its houses in a circle or oval around a central plaza. They were believed to have a relatively egalitarian culture of sedentary people who lived mostly off fishing, though they did some farming and occasionally hunted for deer to supplement their diet. From the archeological remains that have been found, it has been determined that Valdivians cultivated maize, kidney beans, squash, cassava, chili peppers, and cotton plants. The latter was processed, spun, and woven to make clothing.” ref

“Valdivian pottery, dated to 2700 BCE, initially was rough and practical, but it became splendid, delicate, and large over time. They generally used red and gray colors, and the polished dark red pottery is characteristic of the Valdivia period. In their ceramics and stone works, the Valdivia culture shows a progression from the most simple to much more complicated works. The trademark Valdivia piece is the “Venus” of Valdivia: feminine ceramic figures. The “Venus” of Valdivia likely represented actual people, as each figurine is individual and unique, as expressed in the hairstyles. The figures were made joining two rolls of clay, leaving the lower portion separated as legs and making the body and head from the top portion. The arms were usually very short, and in most cases were bent towards the chest, holding the breasts or under the chin. A display of Valdivian artifacts is located at Universidad de Especialidades Espíritu Santo in Guayaquil, Ecuador.” ref

Influences on Valdivia culture

“Ceramic phase A of the Valdivia was long thought to be the oldest pottery produced by a coastal culture in South America, dated to 3000-2700 BCE. In the 1960s, a team of researchers proposed there were significant similarities between the archeological remains and pottery styles of Valdivia and those of the ancient Jōmon culture, active in this same period on the island of Kyūshū, Japan). They compared both decoration and vessel shape, pointing to techniques of incising. The Early to Middle Jomon pottery had antecedents dating 10,000 years, but the Valdivia pottery style seemed to have developed rather quickly. In 1962 three archeologists, Ecuadorian Emilio Estrada and Americans Clifford Evans and Betty Meggers suggested that Japanese fishermen had gotten blown to Ecuador in a storm and introduced their ceramics to Valdivia at that time. Their theory was based on the idea of diffusion of style and techniques. Their concept was challenged at the time by other archaeologists, who argued that there were strong logistical challenges to the idea that Japanese could have survived what would have been nearly a year and a half voyage in dugout canoes. The cultures were separated by a distance of 15,000 km (8,000 nautical miles). Researchers argued that Valdivia ceramics (and culture) had developed independently, and those apparent similarities were a result simply of constraints on technique, and an “accidental convergence” of symbols and style.” ref

“In the 1970s, what is believed widely to be conclusive evidence refuting the diffusion theory was found at the Valdivia type-site, as older pottery and artifacts were found below these excavations. Researchers found what is called San Pedro pottery, pre-dating Phase A and the Valdivia style. It was more primitive. Some researchers believe pottery may have been introduced by people from northern Colombia, where comparably early pottery was found at the Puerto Hormiga archaeological site. In addition, they think that the maize at Valdivia was likely introduced by people living closer to Meosamerica, where it was domesticated. In addition, other pottery remains of the San Pedro style were found at sites about 5.6 miles (9 km) up the river valley. Additional research at both several coastal sites, including San Pablo, Real Alto, and Salango, and Loma Alta, Colimes, and San Lorenzo del Mate inland have resulted in a major rethinking of Valdivian culture. It has been reclassified as representing a “tropical forest culture” with a riverine settlement focus. There has been major re-evaluation of nearly every aspect of its culture.” ref

Ceramics of indigenous peoples of the Americas

“Native American pottery is an art form with at least a 7500-year history in the Americas. Pottery is fired ceramics with clay as a component. Ceramics are used for utilitarian cooking vessels, serving and storage vessels, pipes, funerary urns, censers, musical instruments, ceremonial items, masks, toys, sculptures, and a myriad of other art forms.” ref

“Due to their resilience, ceramics have been key to learning more about pre-Columbian indigenous cultures. The earliest ceramics known from the Americas have been found in the lower Amazon Basin. Ceramics from the Caverna da Pedra Pintada, near Santarém, Brazil, have been dated to 9,500 to 5,000 years ago. Ceramics from Taperinha, also near Santarém, have been dated to 7,000 to 6,000 years ago. Some of the sherds at Taperinho were shell-tempered, which allowed the sherds themselves to be radiocarbon dated. These first ceramics-making cultures were fishers and shellfish-gatherers.” ref

“Ceramics appeared next across northern South America and then down the western side of South America and northward through Mesoamerica. Ceramics of the Alaka culture in Guyana have been dated to 6,000 to 4,500 years ago. Ceramics of the San Jacinto culture in Colombia have been dated to about 4530 BCE, and at Puerto Hormiga, also in Colombia, to about 3794 BCE. Ceramics appeared in the Valdivia culture in Ecuador around 3200 BCE, and in the Pandanche culture in Peru around 2460 BCE.” ref

“The spread of ceramics in Mesoamerica came later. Ceramics from Monagrillo in Panama have been dated to around 2140 BCE, from Tronadora in Costa Rica to around 1890 BCE, and from Barra in the Soconusco of Chiapas to around 1900 BCE. Ceramics of the Purrón tradition in southcentral Mexico have been dated to around 1805 BCE, and from the Chajil tradition of northcentral Mexico, to around 1600 BCE.” ref

“The appearance of ceramics in the Southeastern United States does not fit the above pattern. Ceramics from the middle Savannah River in Georgia and South Carolina (known as Stallings, Stallings Island, or St. Simons) have been dated to about 2888 BCE, and ceramics of the Orange and Norwood cultures in northern Florida to around 2460 BCE (all older than any other dated ceramics from north of Colombia). Ceramics appeared later elsewhere in North America. Ceramics reached southern Florida (Mount Elizabeth) by 4000 BP, Nebo Hill (in Missouri) by 3700 BP, and Poverty Point (in Louisiana) by 3400 BP.” ref

Cultural regions

North America

Arctic

“Several Inuit communities, such as the Netsilik, Sadlermiut, Utkuhiksalik, and Qaernerimiut created utilitarian pottery in historic times, primarily to store food. In Rankin Inlet, Nunavut, Canada, when the mine that employed much of the community closed down, the national government created the Rankin Inlet Ceramics Project, whose wares were successfully exhibited in Toronto in 1967. The project foundered but a local gallery revived interest in Inuit ceramics in the 1990s.” ref

Eastern Woodlands

- “Hopewell pottery is the ceramic tradition of the various local cultures involved in the Hopewell tradition (ca. 200 BCE to 400 CE) and are found as artifacts in archeological sites in the American Midwest and Southeast.

- Mississippian culture pottery is the ceramic tradition of the Mississippian culture (800–1600 CE) found as artifacts in archaeological sites in the American Midwest and Southeast.” ref

Southeastern Woodlands