ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Animism: a belief among some indigenous people, young children, or all religious people!

Pic ref

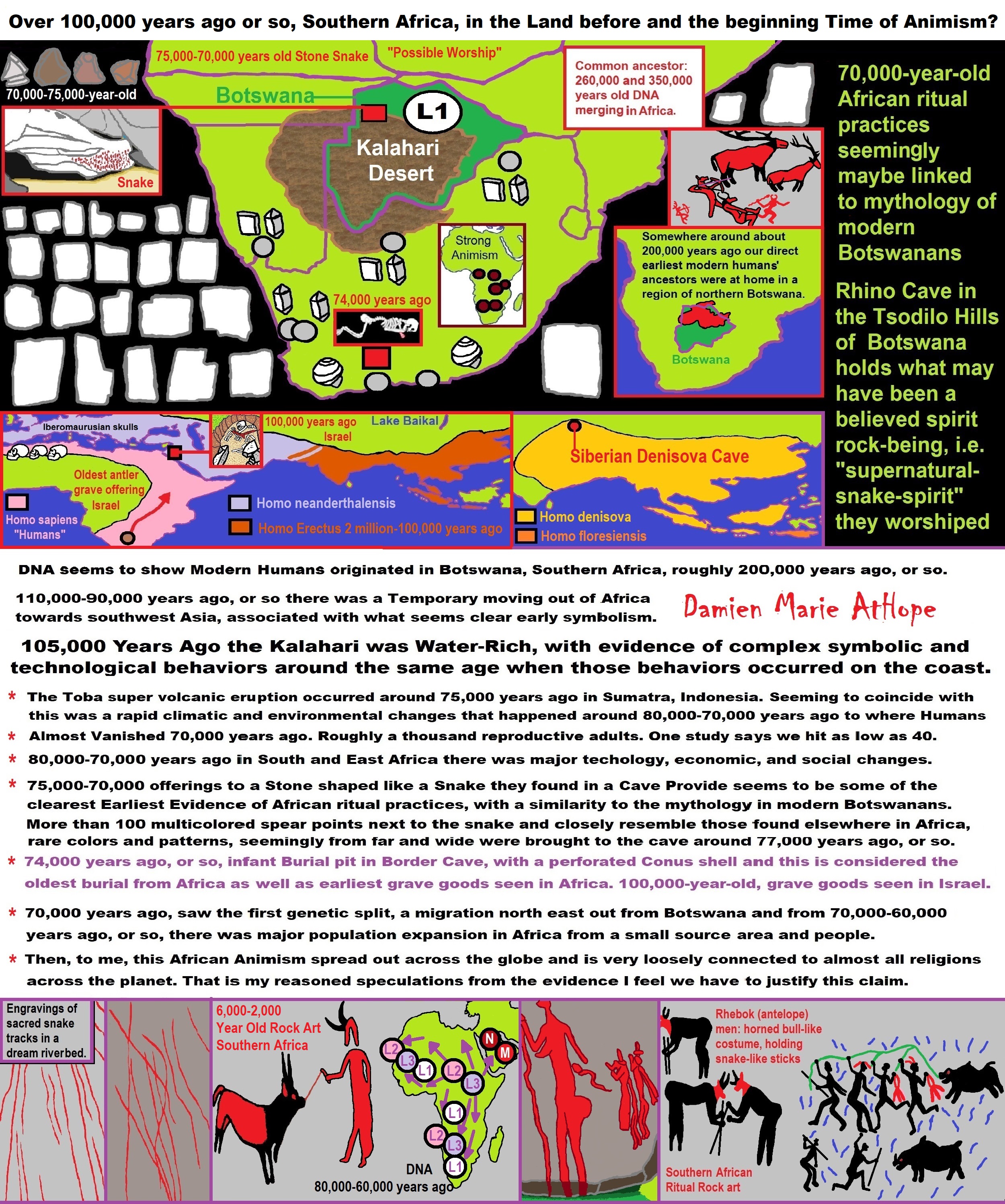

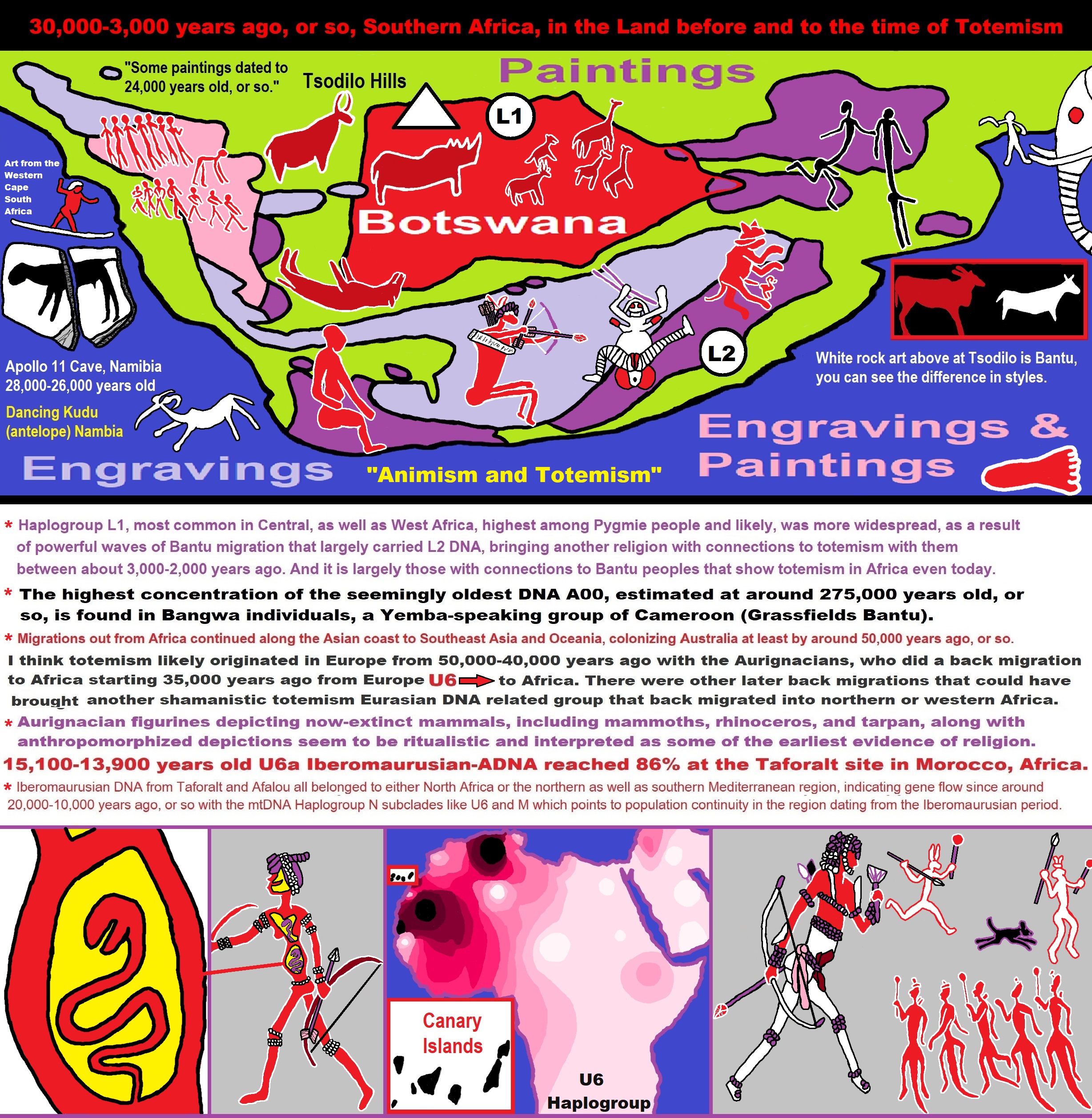

Over 100,000 years ago or so, Southern Africa, in the Land before and the beginning Time of Animism?

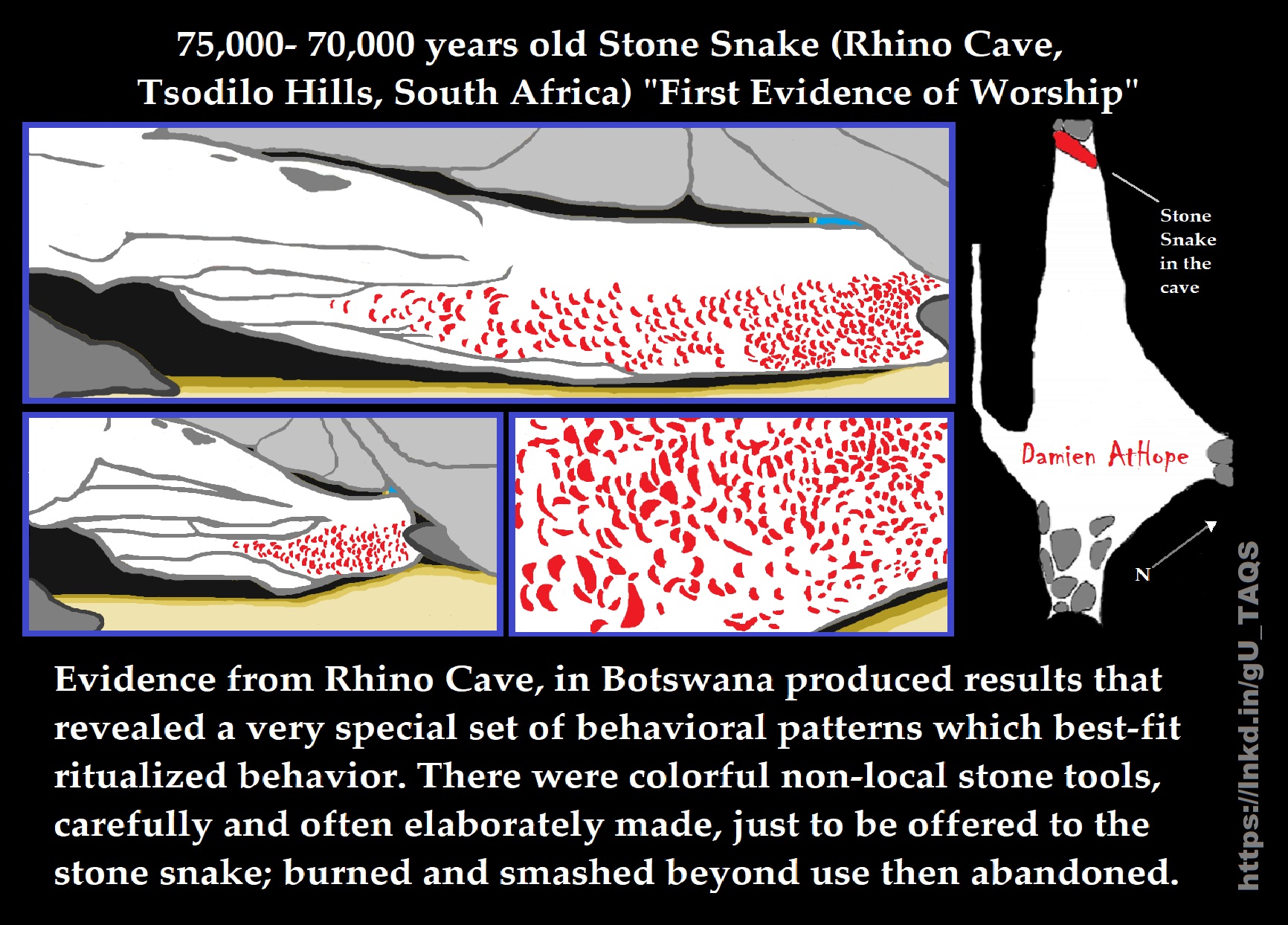

75,000-70,000 years old Stone Snake Possible Worship

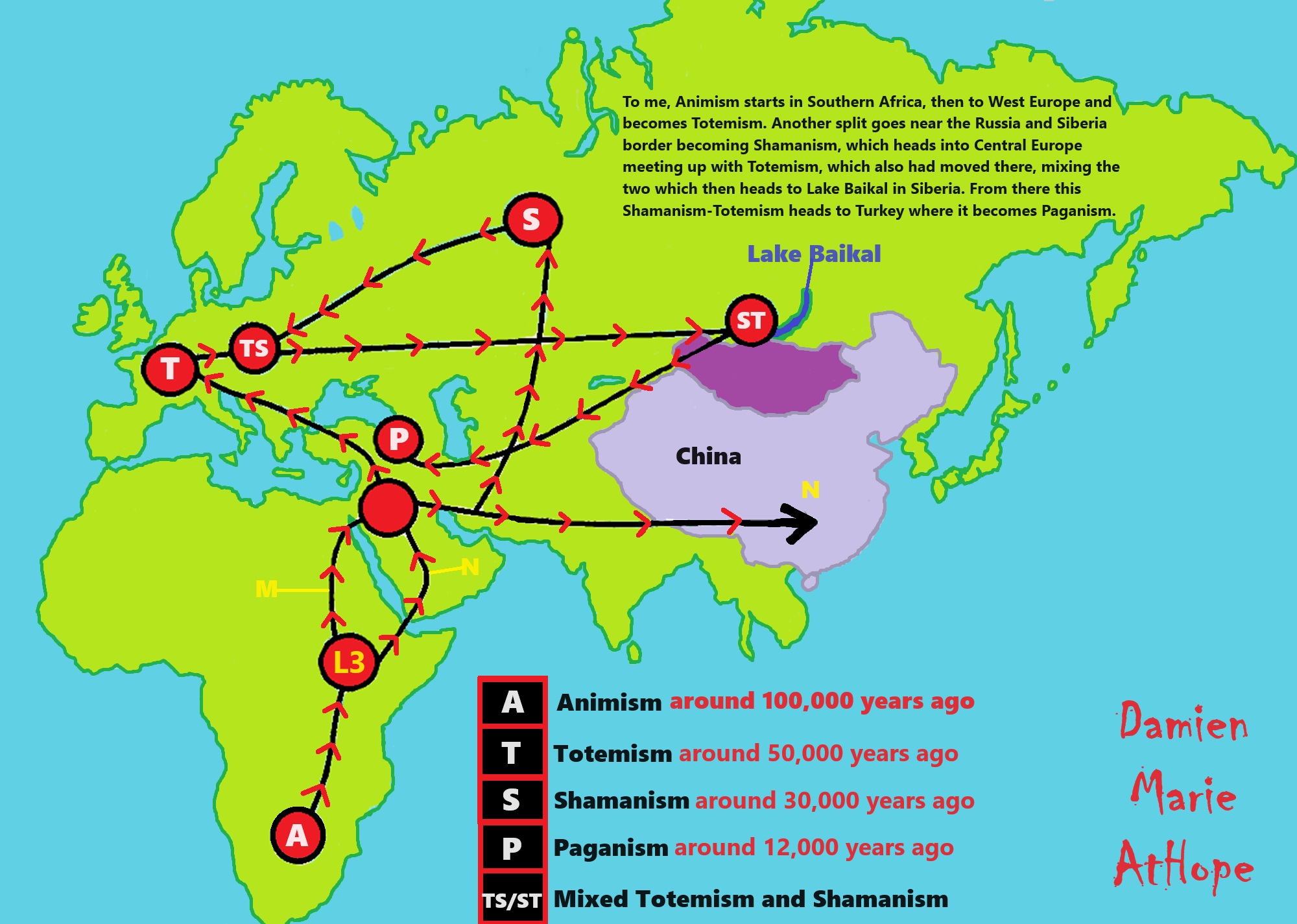

Then, to me, this African Animism spread out across the globe and is very loosely connected to almost all religions across the planet. That is my reasoned speculations from the evidence I feel we have to justify this claim.

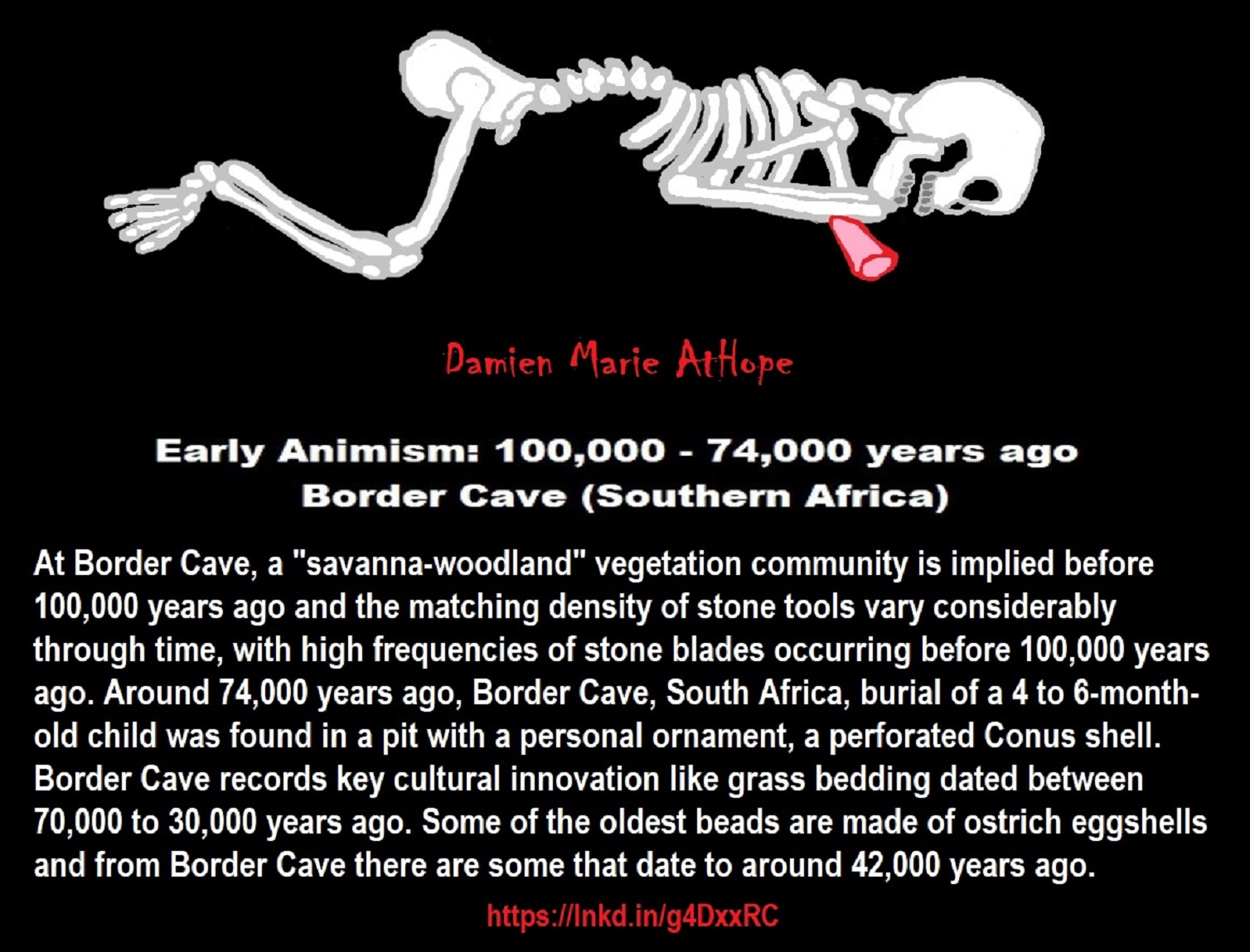

74,000 years ago, or so, infant Burial pit in Border Cave, with a perforated Conus shell, and this is considered the oldest burial from Africa as well as earliest grave goods are seen in Africa. 100,000-year-old, grave goods are seen in Israel.

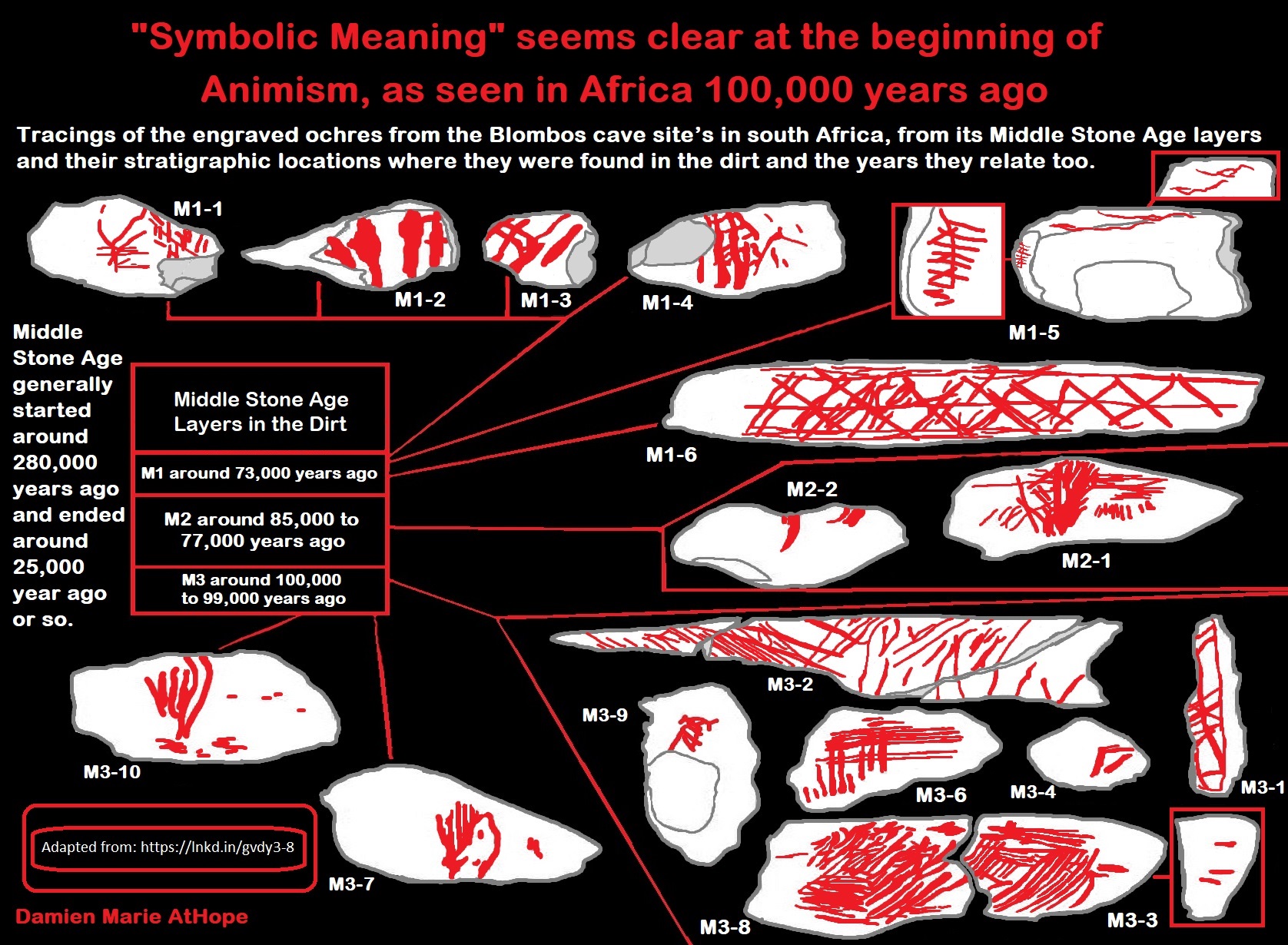

In Africa, it is interpreted that after around 500,000 years ago as some of the earliest evidence for collective ritual. The ubiquitous use of red ochre by 170,000 years ago.

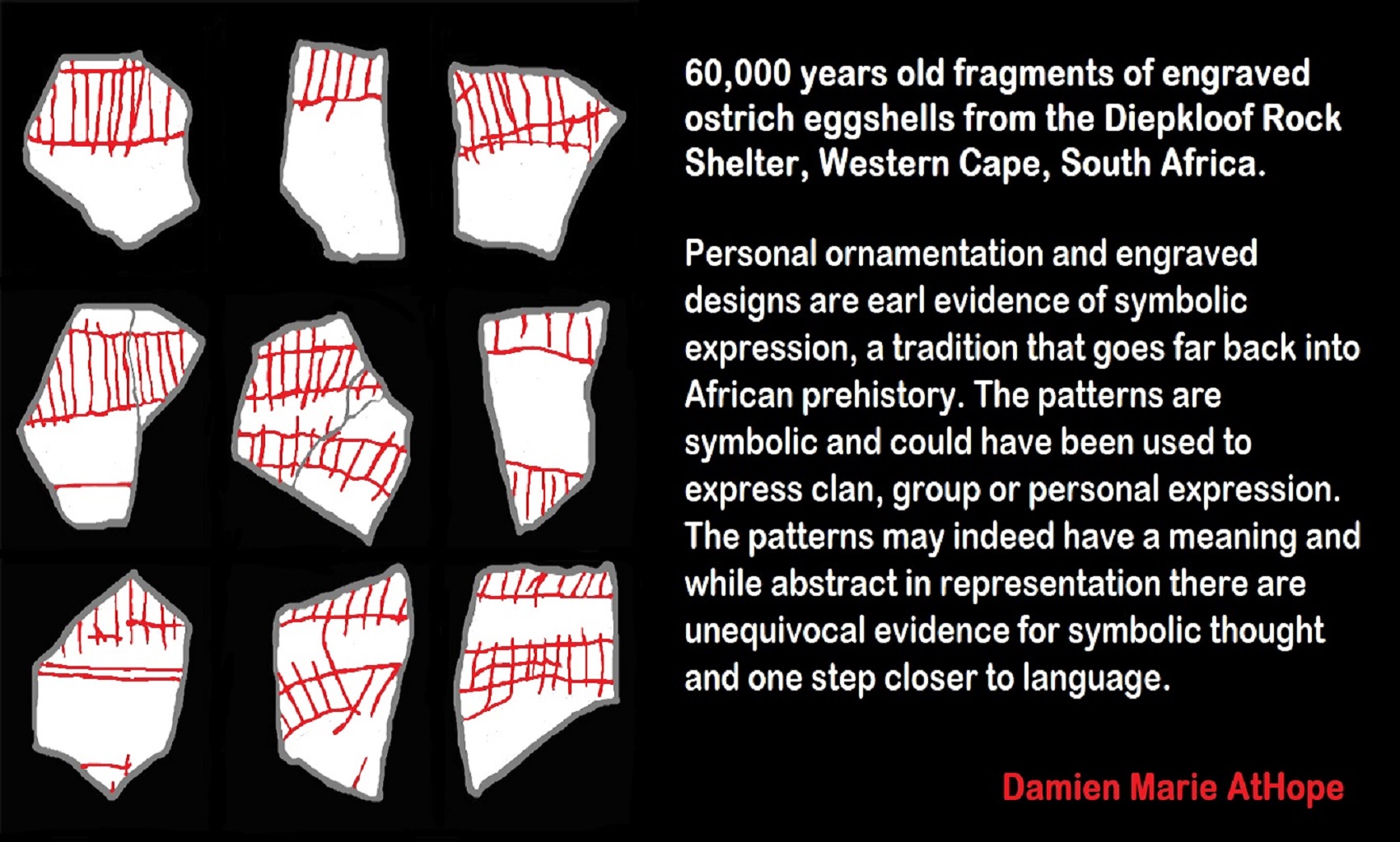

In Africa, symbolic culture was in place by around 100 years ago seen in evidence such as red ochre use, geometric engravings, beads. In Israel around this time, burials even with animals and ochre. In southern Africa around 70,000 to 75,000 years ago sees the first worship of a monolithic stone snake stone in a cave before humanity’s common ancestry separated out of Africa.

Rhino Cave in the Tsodilo Hills of Botswana holds what may have been a believed spirit rock-being, i.e. “supernatural- snake-spirit” they worshiped.

Offerings to a Stone Snake provide the Earliest clear Evidence of Religion in 70,000-year-old African ritual practices linked to the mythology of modern Botswanans.

Is there a seeming gradual evolution of collective ritual, out of which was forged a template of symbolic culture, or at least elements which might be inferred by the time of “Modern Human” dispersal beyond Africa? So, one can reason red and glittery pigment use in Rain Serpents in Northern Australia and Southern Africa: a Common Ancestry?

Animism: Respecting the Living World by Graham Harvey

“How have human cultures engaged with and thought about animals, plants, rocks, clouds, and other elements in their natural surroundings? Do animals and other natural objects have a spirit or soul? What is their relationship to humans? In this new study, Graham Harvey explores current and past animistic beliefs and practices of Native Americans, Maori, Aboriginal Australians, and eco-pagans. He considers the varieties of animism found in these cultures as well as their shared desire to live respectfully within larger natural communities. Drawing on his extensive casework, Harvey also considers the linguistic, performative, ecological, and activist implications of these different animisms.” ref

Pic ref

Pic ref

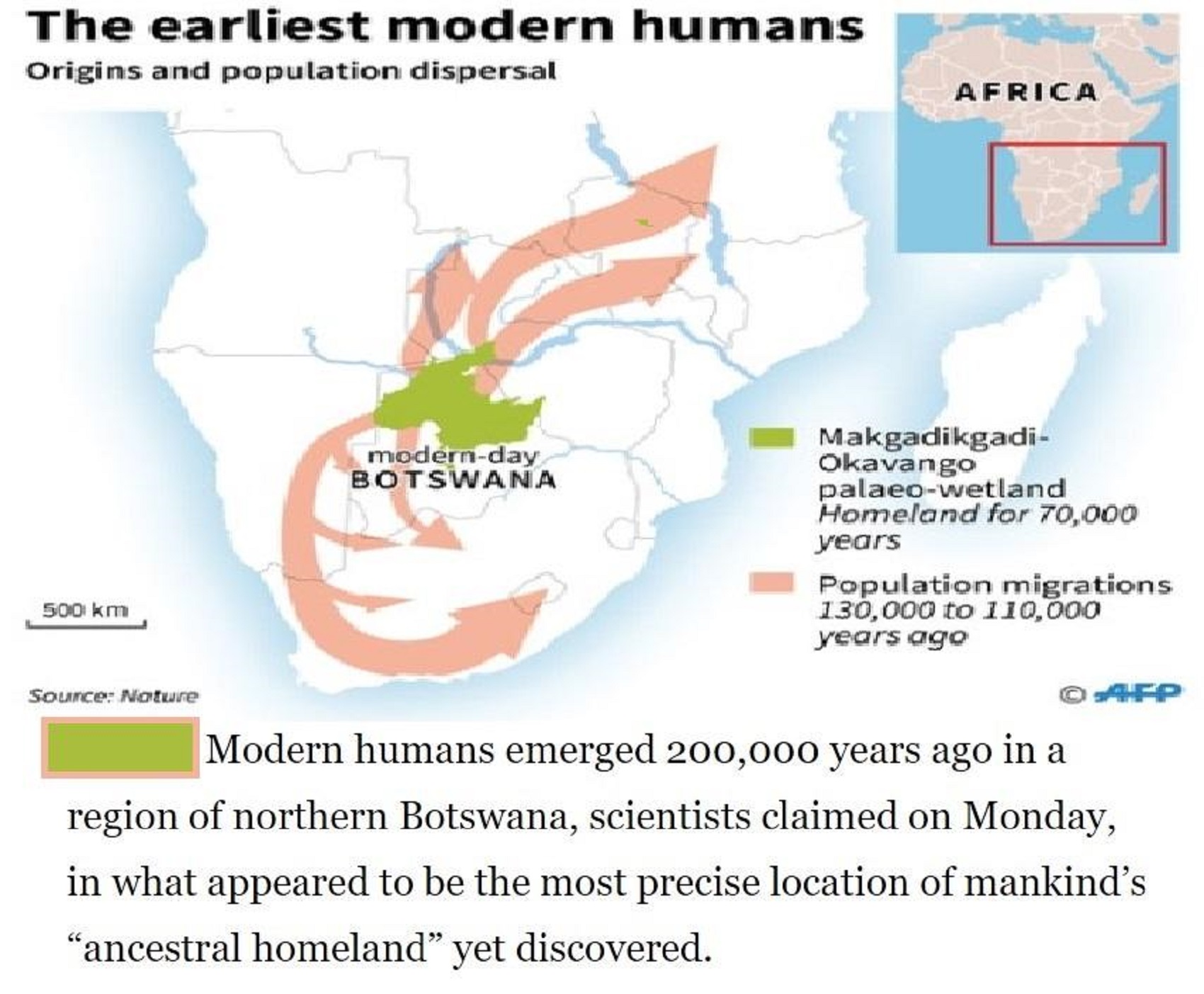

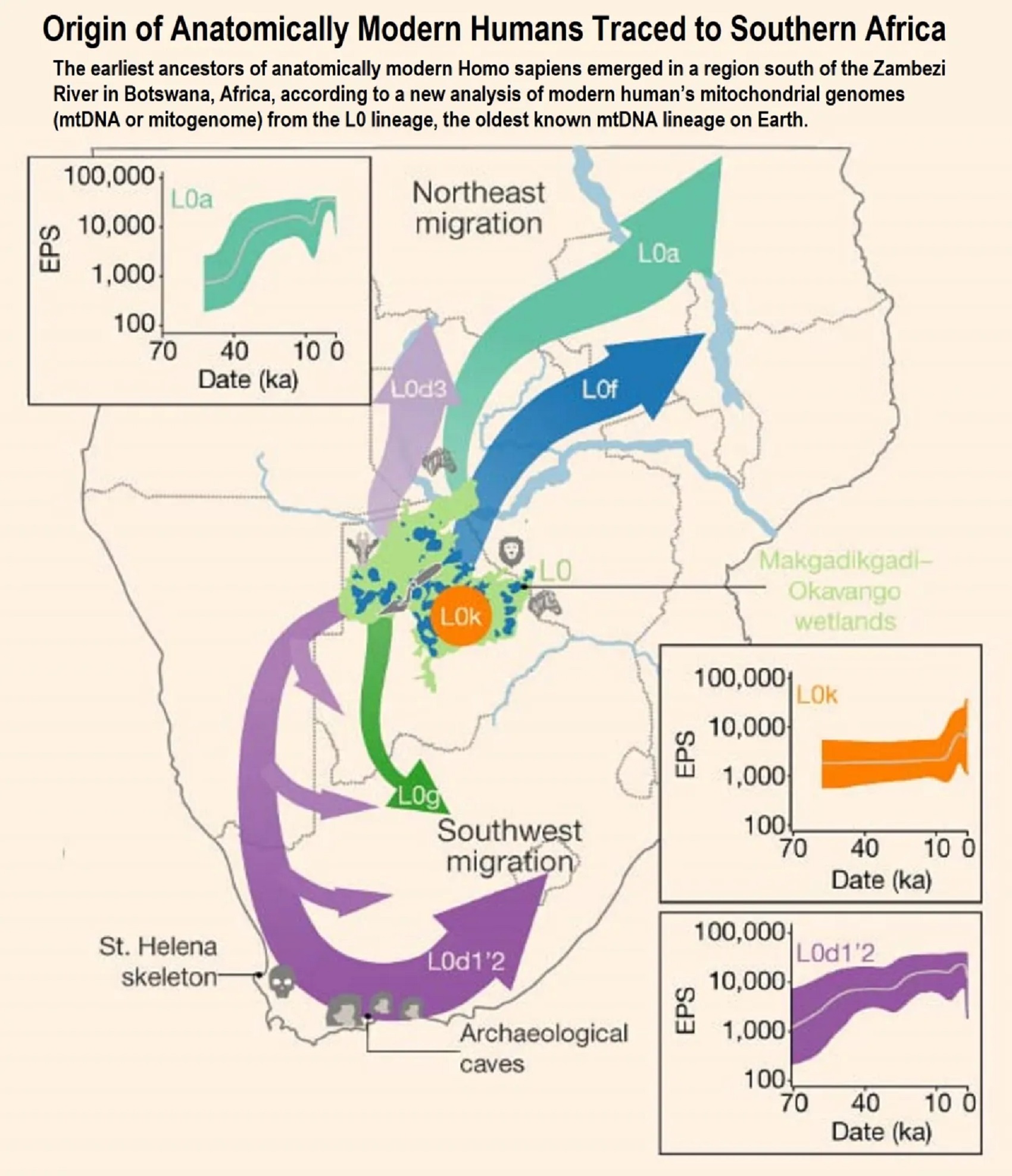

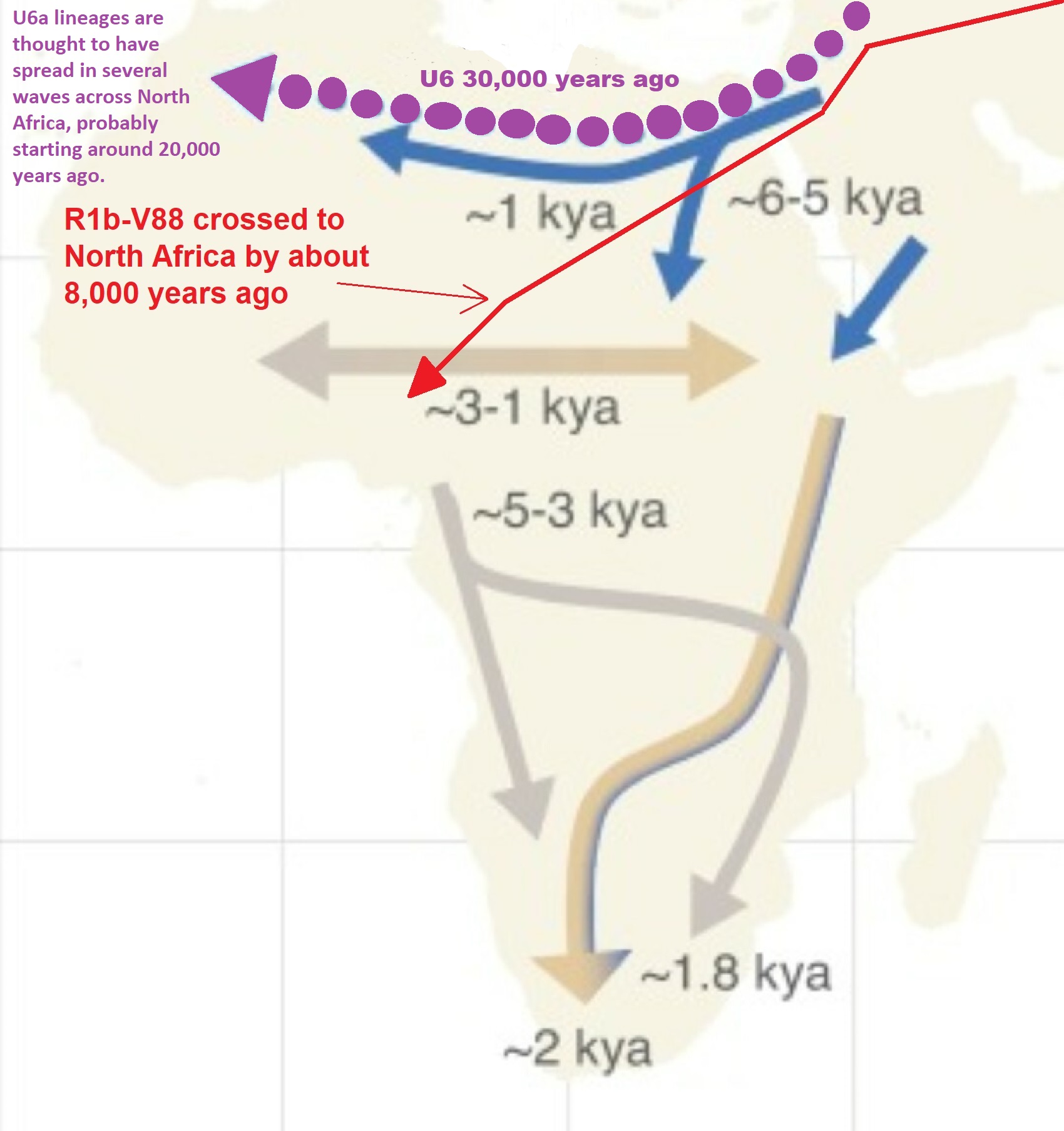

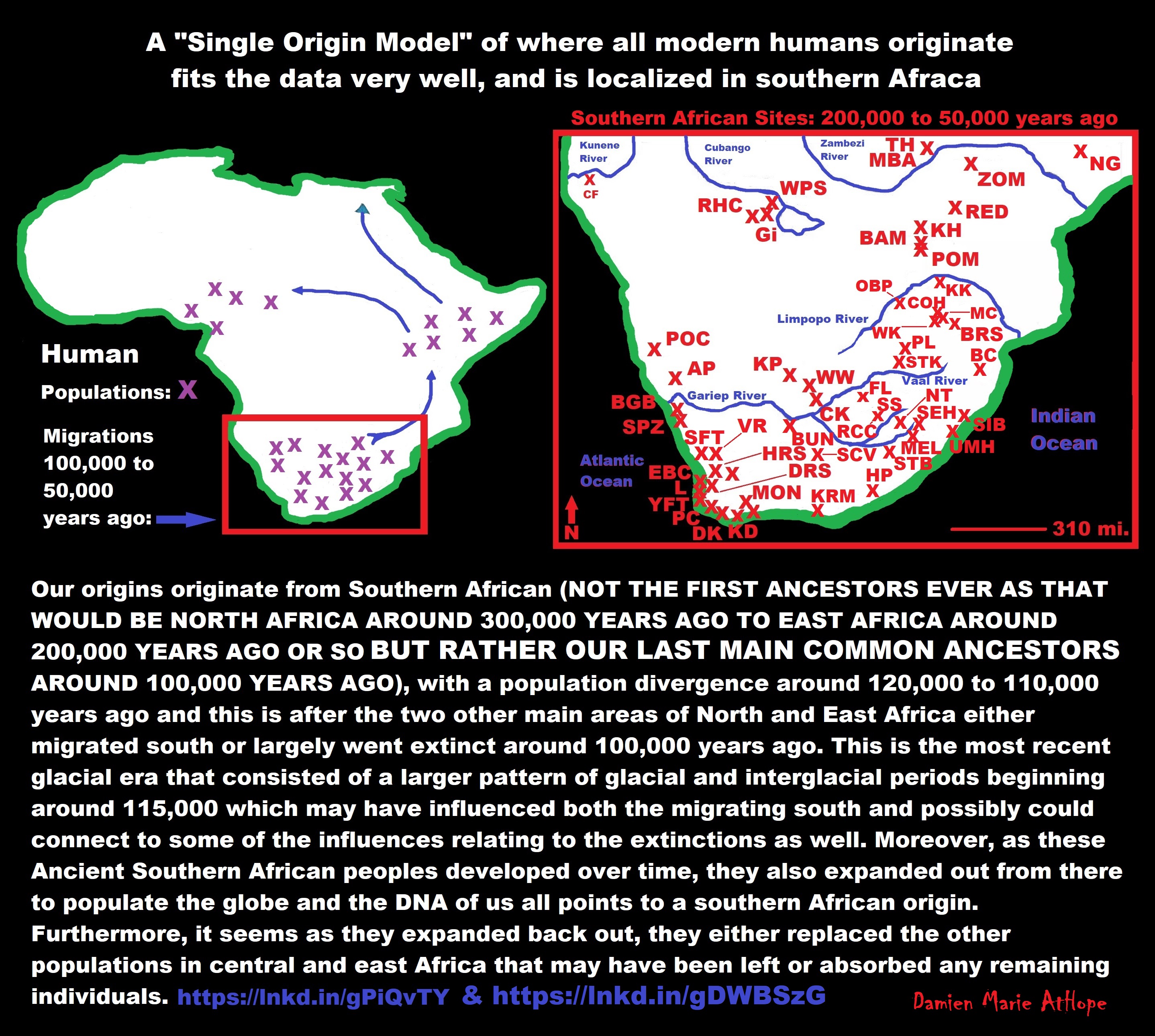

“The earliest ancestors of anatomically modern Homo sapiens emerged in a region south of the Zambezi River in Botswana, Africa, according to a new analysis of modern human’s mitochondrial genomes (mtDNA or mitogenome) from the L0 lineage, the oldest known mtDNA lineage on Earth.” ref

“In terms of mitochondrial haplogroups, the mt-MRCA is situated at the divergence of macro-haplogroup L into L0 and L1–6. As of 2013, estimates on the age of this split ranged at around 155,000 years ago, consistent with a date later than the speciation of Homo sapiens but earlier than the recent out-of-Africa dispersal.” ref

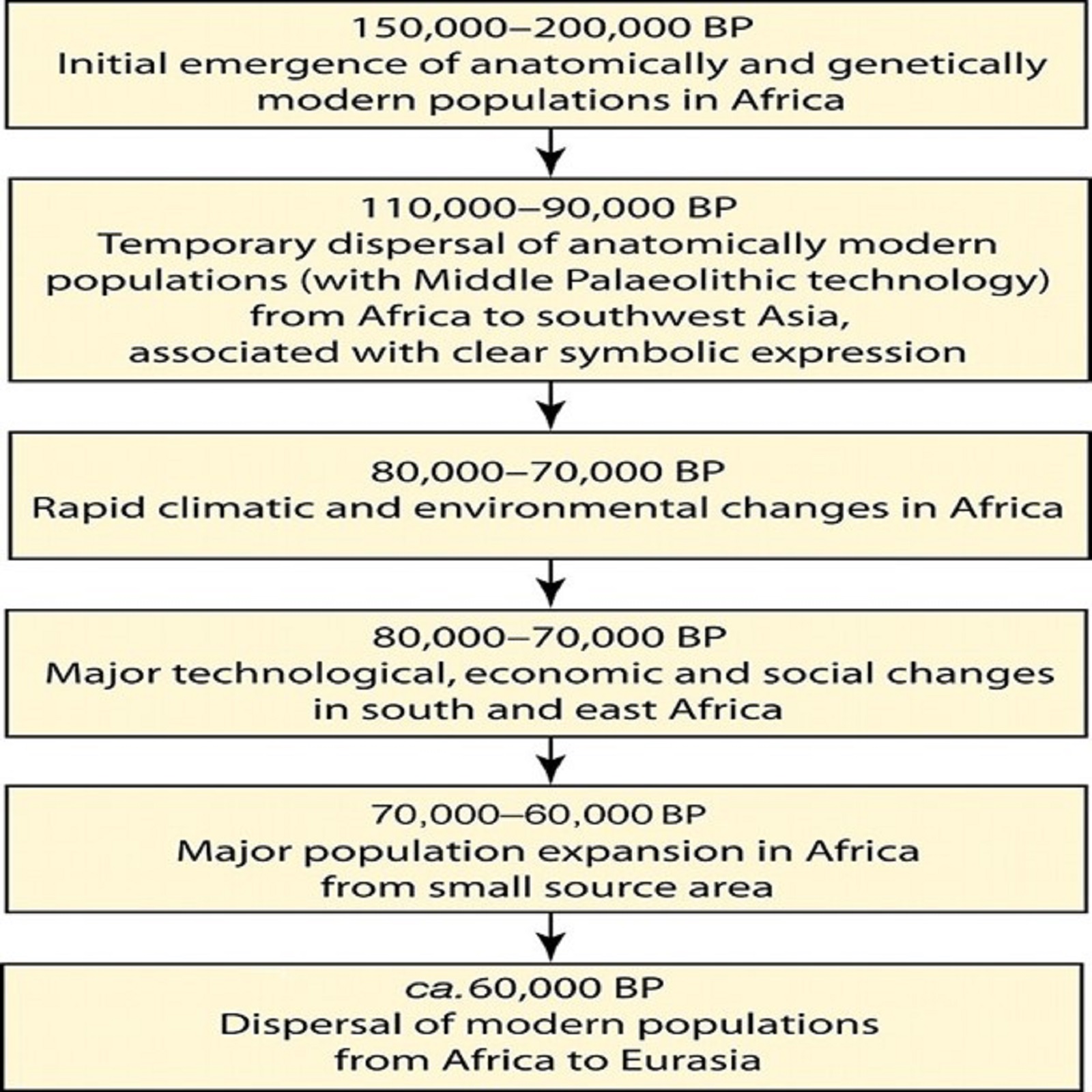

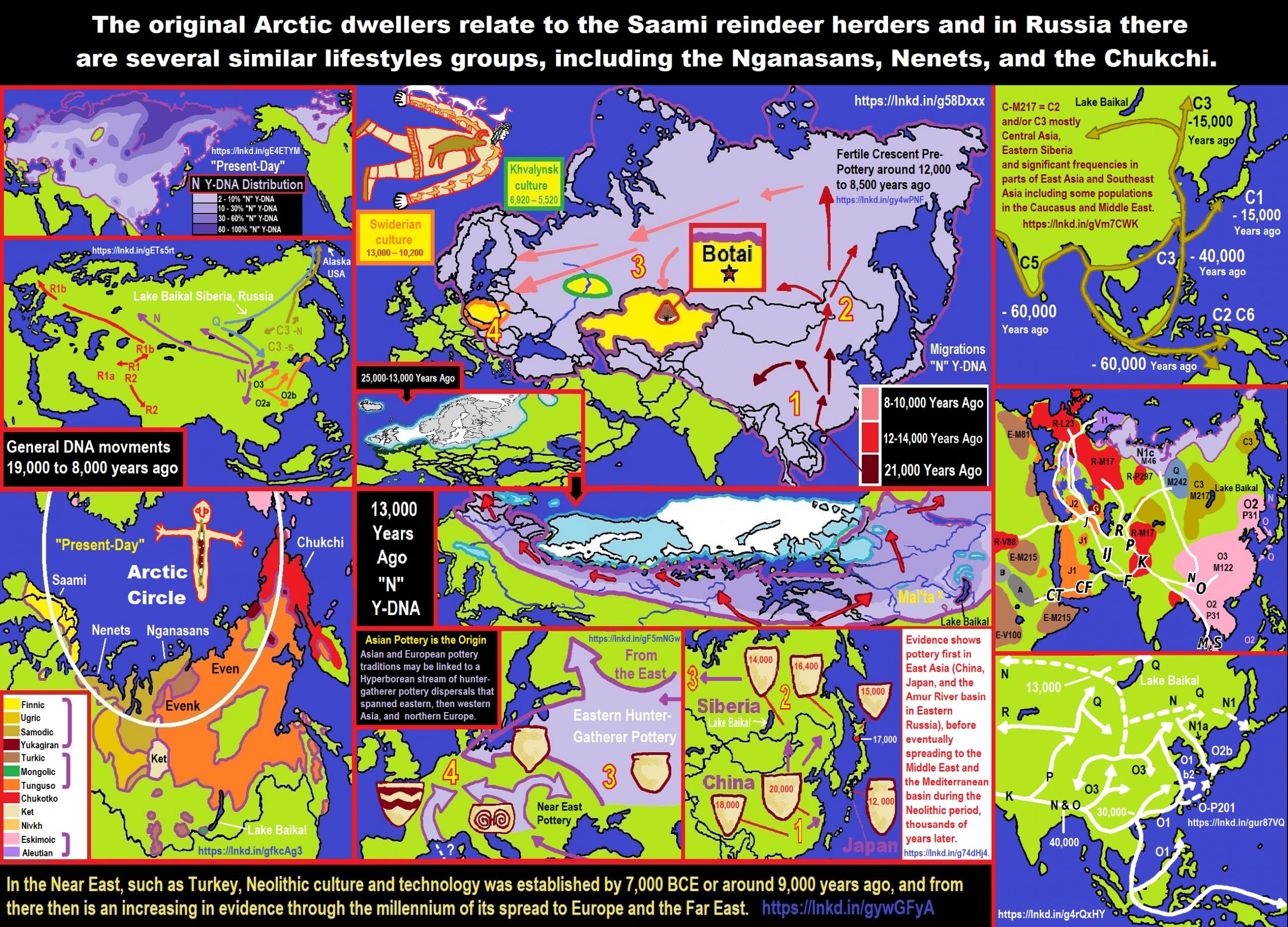

“There were at least several “out-of-Africa” dispersals of modern humans, possibly beginning as early as 270,000 years ago, including 215,000 years ago to at least Greece, and certainly via northern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula about 130,000 to 115,000 years ago. There is evidence that modern humans had reached China around 80,000 years ago. Practically all of these early waves seem to have gone extinct or retreated back, and present-day humans outside Africa descend mainly from a single expansion out 70,000–50,000 years ago. The most significant “recent” wave out of Africa took place about 70,000–50,000 years ago, via the so-called “Southern Route“, spreading rapidly along the coast of Asia and reaching Australia by around 65,000–50,000 years ago, (though some researchers question the earlier Australian dates and place the arrival of humans there at 50,000 years ago at earliest, while others have suggested that these first settlers of Australia may represent an older wave before the more significant out of Africa migration and thus not necessarily be ancestral to the region’s later inhabitants) while Europe was populated by an early offshoot which settled the Near East and Europe less than 55,000 years ago.” ref

“Haplogroup L3 is a human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup. The clade has played a pivotal role in the early dispersal of anatomically modern humans. It is strongly associated with the out-of-Africa migration of modern humans of about 70–50,000 years ago. It is inherited by all modern non-African populations, as well as by some populations in Africa. Haplogroup L3 arose close to 70,000 years ago, near the time of the recent out-of-Africa event. This dispersal originated in East Africa and expanded to West Asia, and further to South and Southeast Asia in the course of a few millennia, and some research suggests that L3 participated in this migration out of Africa. L3 is also common amongst African Americans and Afro-Brazilians. A 2007 estimate for the age of L3 suggested a range of 104–84,000 years ago. More recent analyses, including Soares et al. (2012) arrive at a more recent date, of roughly 70–60,000 years ago. Soares et al. also suggest that L3 most likely expanded from East Africa into Eurasia sometime around 65–55,000 years ago years ago as part of the recent out-of-Africa event, as well as from East Africa into Central Africa from 60 to 35,000 years ago. In 2016, Soares et al. again suggested that haplogroup L3 emerged in East Africa, leading to the Out-of-Africa migration, around 70–60,000 years ago.” ref

“Haplogroups L6 and L4 form sister clades of L3 which arose in East Africa at roughly the same time but which did not participate in the out-of-Africa migration. The ancestral clade L3’4’6 has been estimated at 110 kya, and the L3’4 clade at 95 kya. The possibility of an origin of L3 in Asia was also proposed by Cabrera et al. (2018) based on the similar coalescence dates of L3 and its Eurasian-distributed M and N derivative clades (ca. 70 kya), the distant location in Southeast Asia of the oldest known subclades of M and N, and the comparable age of the paternal haplogroup DE. According to this hypothesis, after an initial out-of-Africa migration of bearers of pre-L3 (L3’4*) around 125 kya, there would have been a back-migration of females carrying L3 from Eurasia to East Africa sometime after 70 kya. The hypothesis suggests that this back-migration is aligned with bearers of paternal haplogroup E, which it also proposes to have originated in Eurasia. These new Eurasian lineages are then suggested to have largely replaced the old autochthonous male and female North-East African lineages.” ref

“According to other research, though earlier migrations out of Africa of anatomically modern humans occurred, current Eurasian populations descend instead from a later migration from Africa dated between about 65,000 and 50,000 years ago (associated with the migration out of L3). Vai et al. (2019) suggest, from a newly discovered old and deeply-rooted branch of maternal haplogroup N found in early Neolithic North African remains, that haplogroup L3 originated in East Africa between 70,000 and 60,000 years ago, and both spread within Africa and left Africa as part of the Out-of-Africa migration, with haplogroup N diverging from it soon after (between 65,000 and 50,000 years ago) either in Arabia or possibly North Africa, and haplogroup M originating in the Middle East around the same time as “N.” A study by Lipson et al. (2019) analyzing remains from the Cameroonian site of Shum Laka found them to be more similar to modern-day Pygmy peoples than to West Africans, and suggests that several other groups (including the ancestors of West Africans, East Africans, and the ancestors of non-Africans) commonly derived from a human population originating in East Africa between about 80,000-60,000 years ago, which they suggest was also the source and origin zone of haplogroup L3 around 70,000 years ago.” ref

Did Pleistocene Africans use the spearthrower‐and‐dart?

“Well, evidence grows apace for ever-more ancient bow-and-arrow use. List of age estimates, locations, and current evidence bundles for the use of either arrows or darts by/before 30,000 years ago, the list may not be exhaustive, but we suggest that it broadly summarizes current knowledge (MSA = middle stone age).” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref ,ref, ref, ref

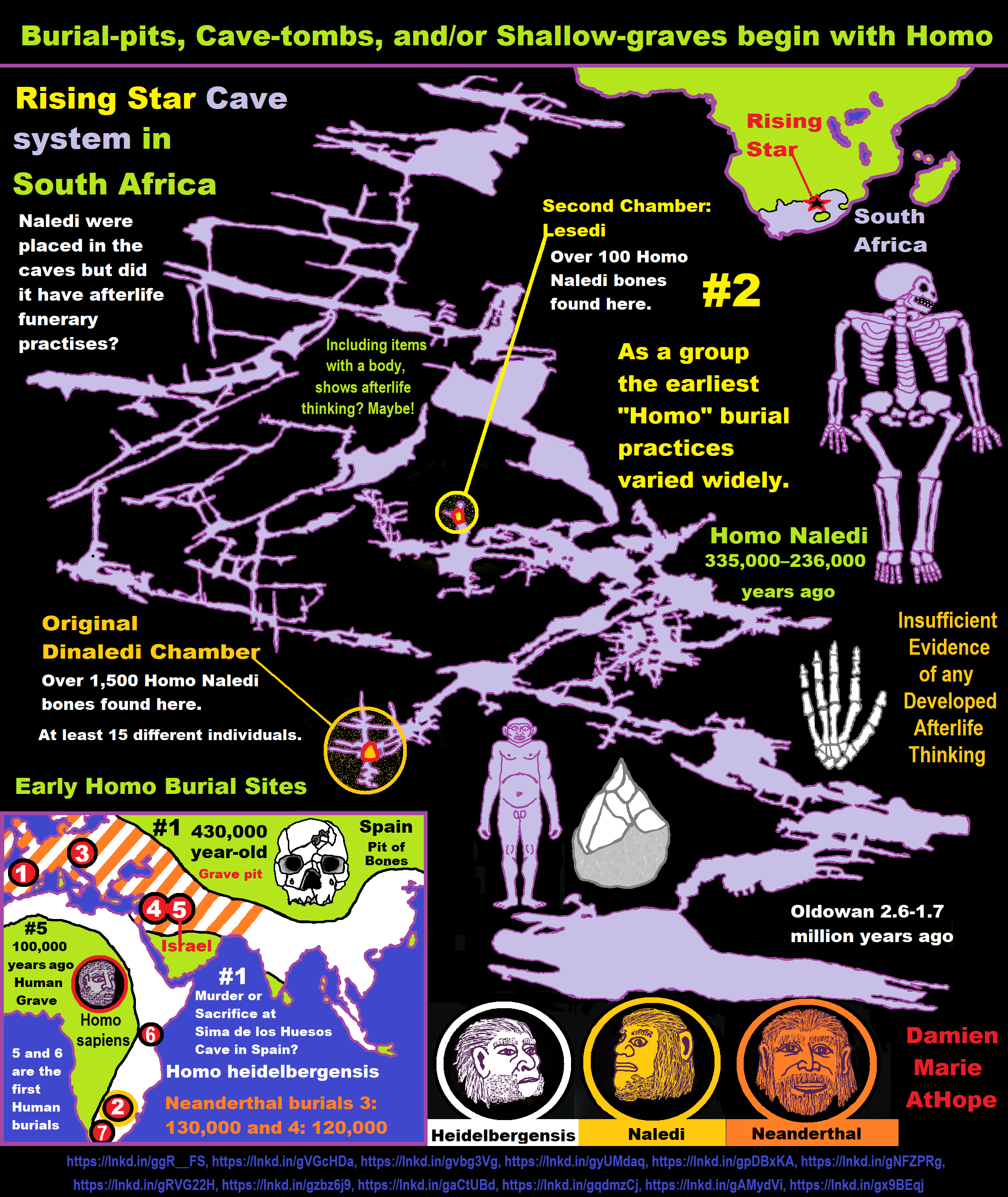

Homo Naledi

“Homo Naledi is a species of archaic human discovered in the Rising Star Cave, Cradle of Humankind, South Africa dating to the Middle Pleistocene 335,000–236,000 years ago. The initial discovery comprises 1,550 specimens, representing 737 different elements, and at least 15 different individuals. Despite this exceptionally high number of specimens, their classification with other Homo remains unclear.” ref

“Along with similarities to contemporary Homo, they share several characteristics with the ancestral Australopithecus and early Homo as well (mosaic anatomy), most notably a small cranial capacity of 465–610 cm3 (28.4–37.2 cu in), compared to 1,270–1,330 cm3 (78–81 cu in) in modern humans. They are estimated to have averaged 143.6 cm (4 ft 9 in) in height and 39.7 kg (88 lb) in weight, yielding a small encephalization quotient of 4.5. Nonetheless, Homo Naledi’s brain anatomy seems to have been similar to contemporary Homo, which could indicate equatable cognitive complexity. The persistence of small-brained humans for so long in the midst of bigger-brained contemporaries revises the previous conception that a larger brain would necessarily lead to an evolutionary advantage, and their mosaic anatomy greatly expands the known range of variation for the genus.” ref

“Homo Naledi anatomy indicates that, though they were capable of long-distance travel with a humanlike stride and gait, they were more arboreal than other Homo, better adapted to climbing and suspensory behavior in trees than endurance running. Tooth anatomy suggests consumption of gritty foods covered in particulates such as dust or dirt. Though they have not been associated with stone tools or any indication of material culture, they appear to have been dextrous enough to produce and handle tools, and likely manufactured Early or Middle Stone Age industries. It has also been controversially postulated that these individuals were given funerary rites, and were carried into and placed in the chamber.” ref

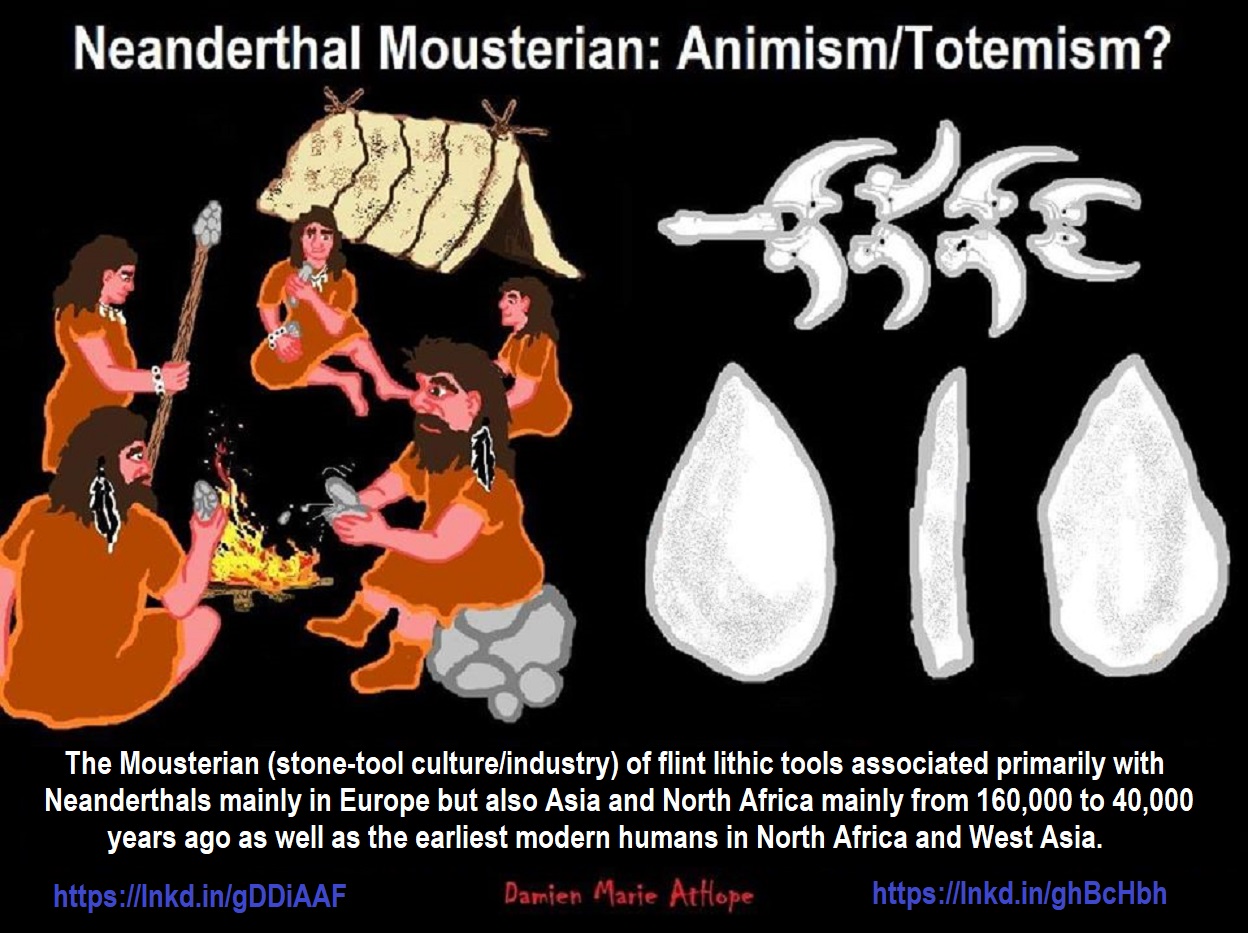

Neanderthal Mousterian: Animism/Totemism?

The Mousterian (stone-tool culture/industry) of flint lithic tools associated primarily with the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia, as well as with the Neanderthals in Europe from 160,000 to 40,000 years ago. If its predecessor, known as Levallois or “Levallois-Mousterian” is included, the range is extended to as early as c. 300,000–200,000 years ago. Moreover, Mousterian continued alongside the new Neandertal Châtelperronian industry during the 45,000-40,000 ref

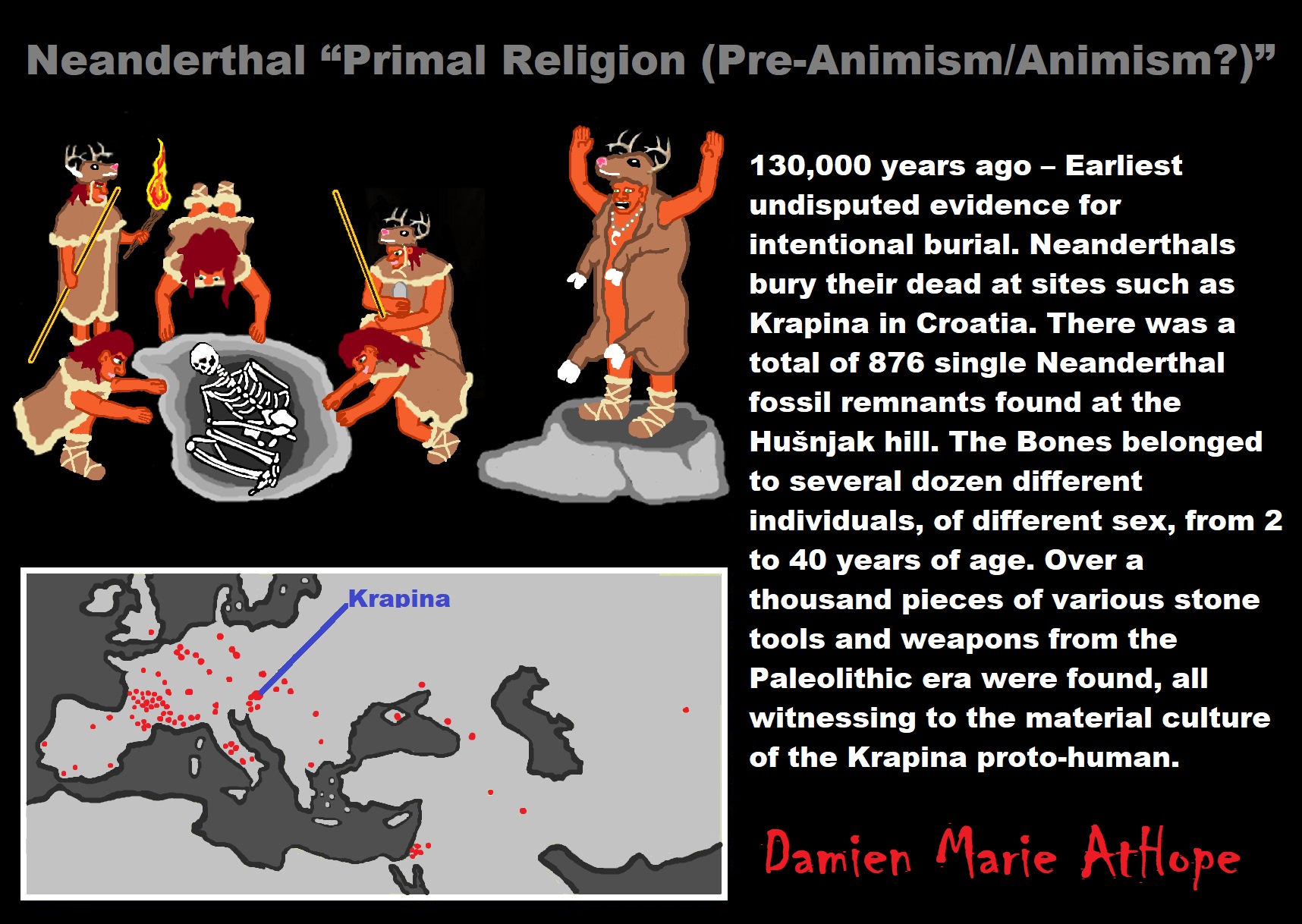

130,000 years ago – Earliest undisputed evidence for intentional burial and it is Neanderthals…

Evidence suggests that the Neanderthals were the first humans to intentionally bury the dead and possibly doing cannibalism which could be evidence of a death ritual, doing so in shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. 130,000 years ago – Earliest undisputed evidence for intentional burial. Neanderthals bury their dead at sites such as Krapina in Croatia. There was a total of 876 single Neanderthal fossil remnants found at the Hušnjak hill. The Bones belonged to several dozen different individuals, of different sex, from 2 to 40 years of age. Over a thousand pieces of various stone tools and weapons from the Paleolithic era were found, all witnessing to the material culture of the Krapina proto-human. This rich locality is approximately 130.000 years old.

Numerous fossil remnants of the cave bear, wolf, moose, large deer, warm climate rhinoceros, wild cattle and many other animals were also found. Moreover, there is bird skeletons, with some of the parts modified, are found in association with the Neanderthal bones. Here are some talons and foot bones from the white-tailed eagle. There appears to be cut marks in the talons and foot bones to which they were attached, suggesting that Neanderthals were using the talons and bones as jewelry. This is supported by recent findings of gut “fiber” tied around part of a talon. Here are a foot bone and a talon that have been modified by having grooves cut in them. Neanderthals were largely carnivores, though we know they also used medicinal plants. ref, ref, ref

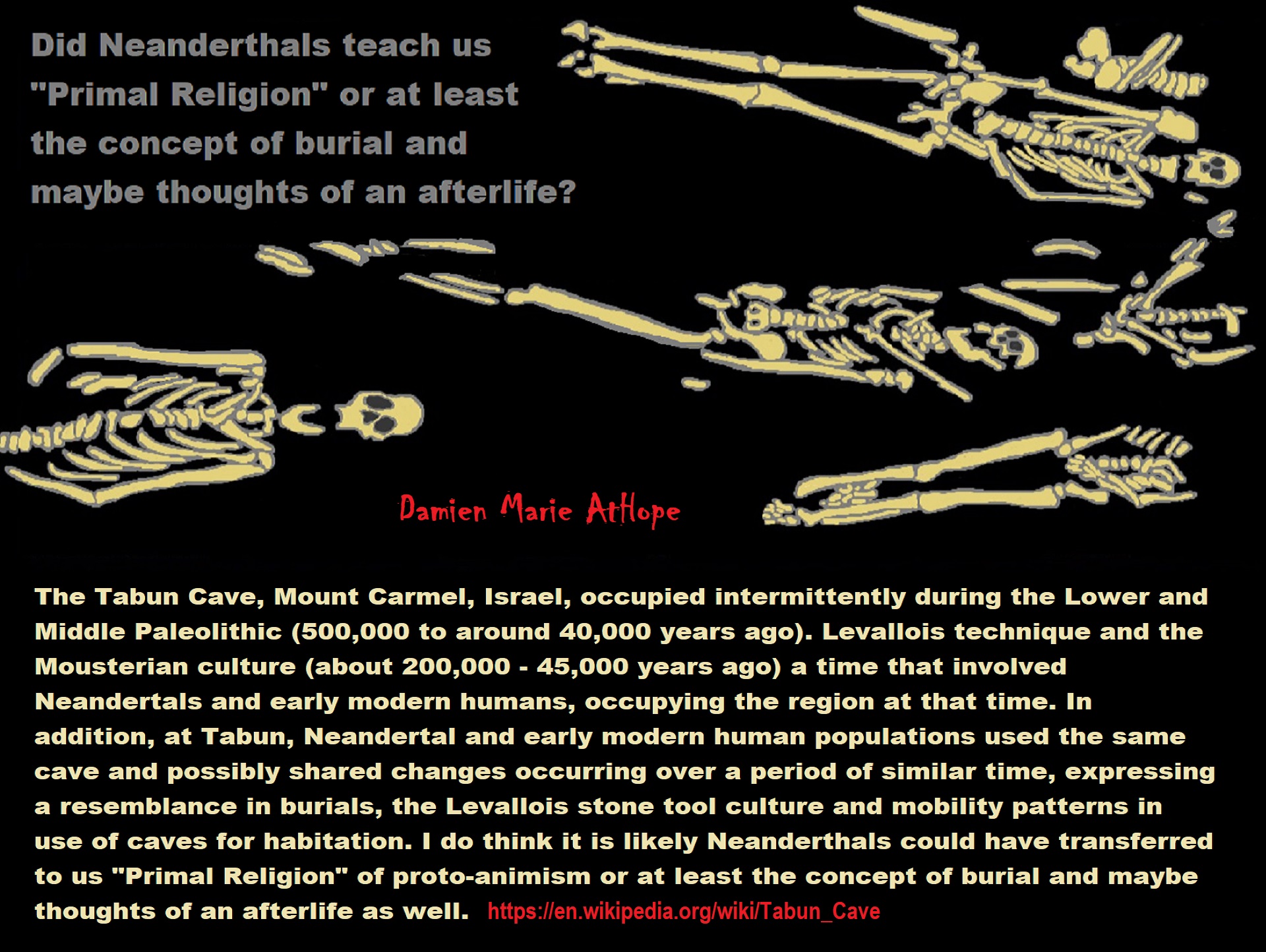

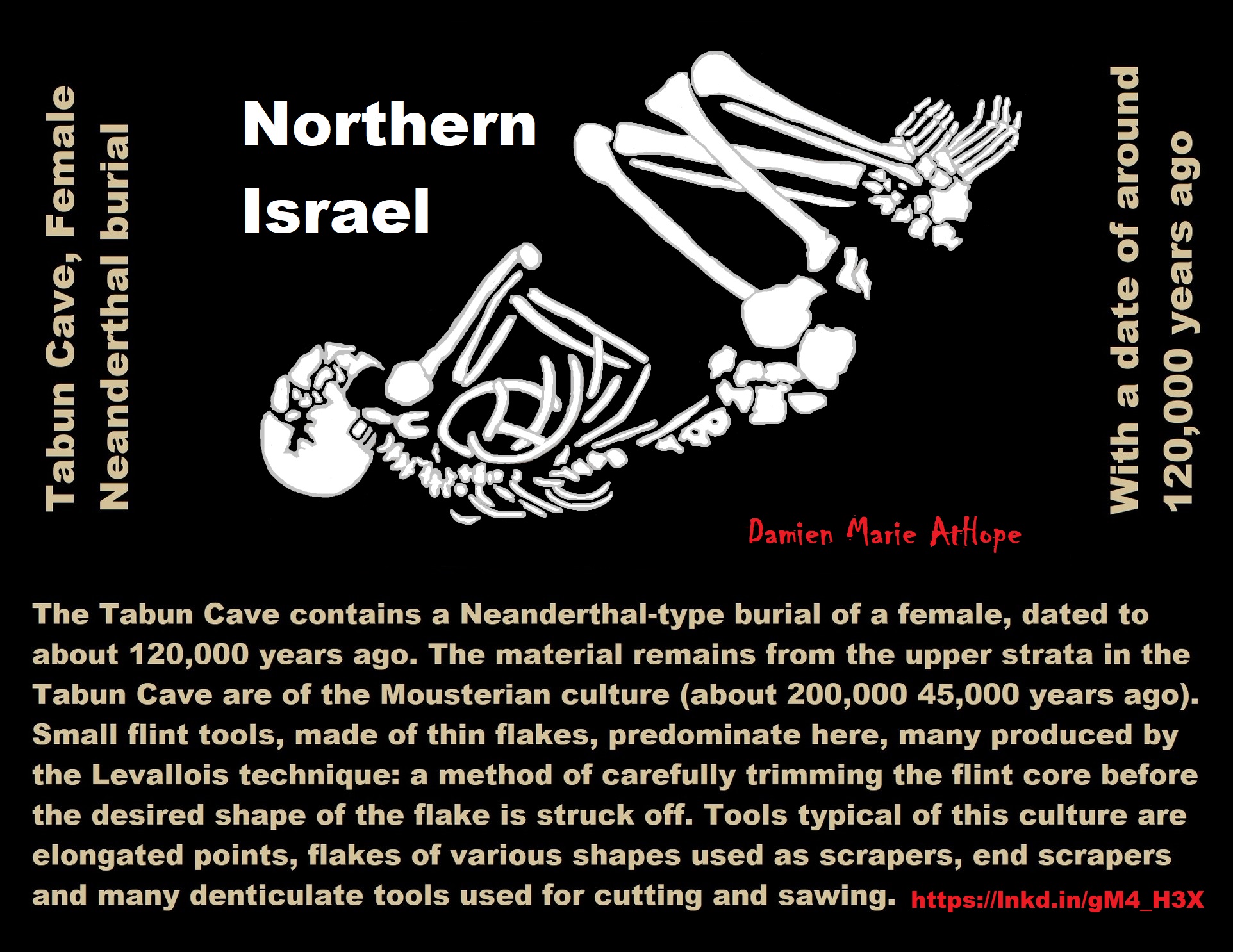

The Tabun Cave, Mount Carmel, Israel, occupied intermittently during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic (500,000 to around 40,000 years ago). Tabun suggests that ancestral humans used fire at the site on a regular basis since about 350,000 years ago and this likely would have shaped our culture and behavior. The material remains from the upper strata of the cave are of Levallois technique and the Mousterian culture (about 200,000 – 45,000 years ago). The Middle Palaeolithic of the southern Levant involved Neandertals and early modern humans, occupying the region at that time. Tabun Cave held fossil remains involved Neandertals and early modern humans but not an absolute chronology of the Levantine MP fossils though could indicates that an enamel fragment from the Tabun C1 could be as old as 143,000 years ago nearly double Tabun BC7. Moreover, a Neanderthal-type female, dated to about 120,000 years ago around the time early modern humans existed there which was between 120,000 – 90,000 years ago and again from 55,000 years ago on. ref, ref, ref, ref

Did Neanderthals teach us “Primal Religion (Pre-Animism/Animism?)” 120,000 Years Ago?

Homo sapiens – is known to have reached the Levant between 120,000 and 90,000 years ago, but that exit from Africa evidently went extinct. Homo sapiens – is known to have reached the Levant between 120,000 and 90,000 years ago, but that exit from Africa evidently went extinct. Tabun Cave Mousterian (stone tool) culture (about 200,000 45,000 years ago). Small flint tools, made of thin flakes, predominate here, many produced by the Levallois technique. ref, ref

Animism: an approximately 100,000-year-old belief system?

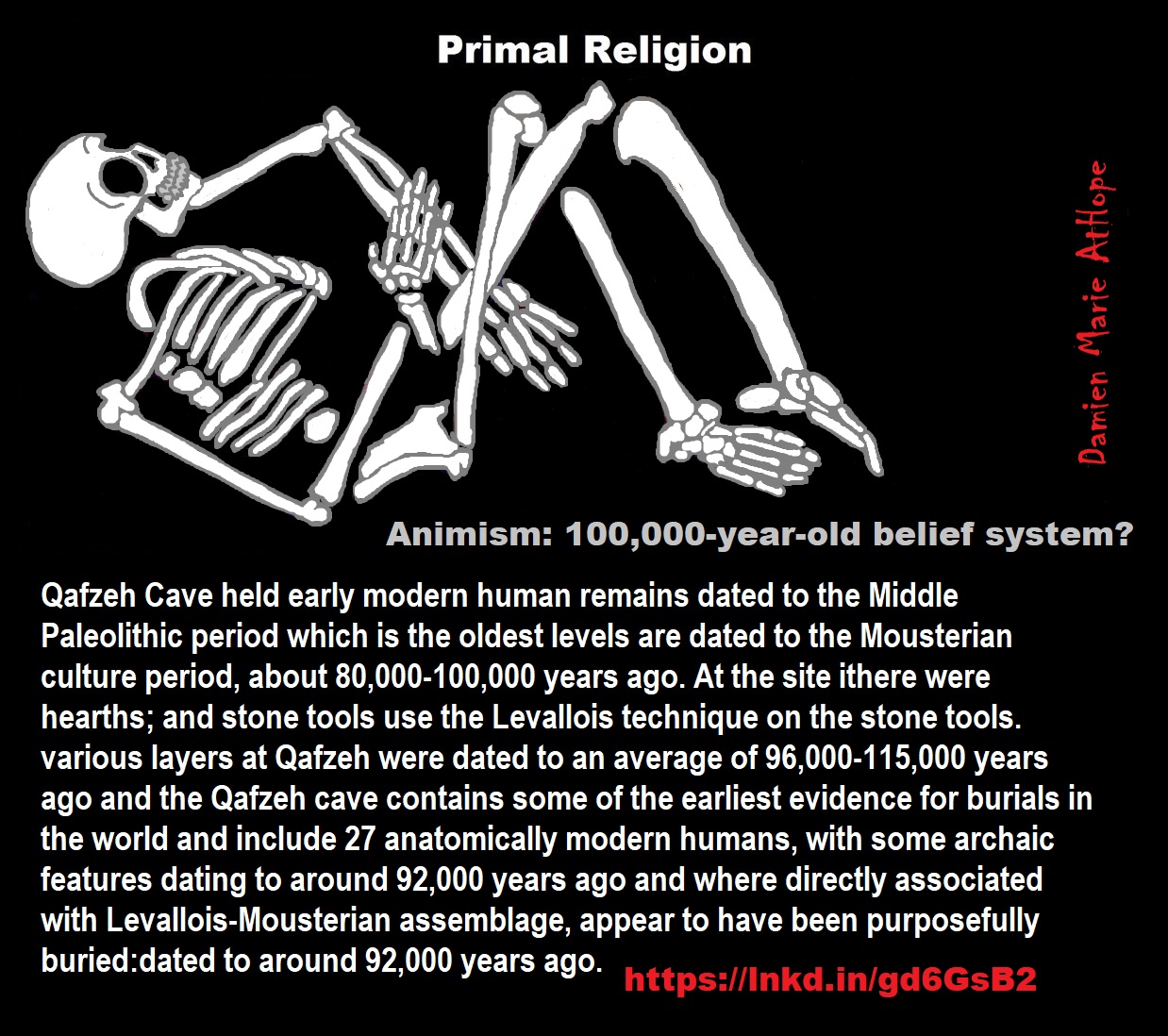

Qafzeh Cave held early modern human remains dating to the Middle Paleolithic period which is the oldest levels are dated to the Mousterian culture period, about 80,000-100,000 years ago. At the site there were hearths; and stone tools use the Levallois technique on the stone tools. various layers at Qafzeh were dated to an average of 96,000-115,000 years ago and the Qafzeh cave contains some of the earliest evidence for burials in the world and included 27 anatomically modern humans, with some archaic features dating to around 92,000 years ago and were directly associated with Levallois-Mousterian assemblage, appear to have been purposefully buried: dated to around 92,000 years ago. The remains are from anatomically modern humans, with some archaic features; they are directly associated with Levallois-Mousterian assemblage. Modern behaviors indicated at the cave include the purposeful burials; the use of ochre for body painting; the presence of marine shells, used as ornamentation, and most interestingly, the survival and eventual ritual interment of a severely brain-damaged child. Moreover, deer antlers at Qafzeh 11 seem to be associated with burials unlike the marine shells which do not seem to be associated with burials, but rather are scattered more or less randomly throughout the site, possibly as a sacred offering, one that sanctifies an area? Or kind of blessing the aria? ref

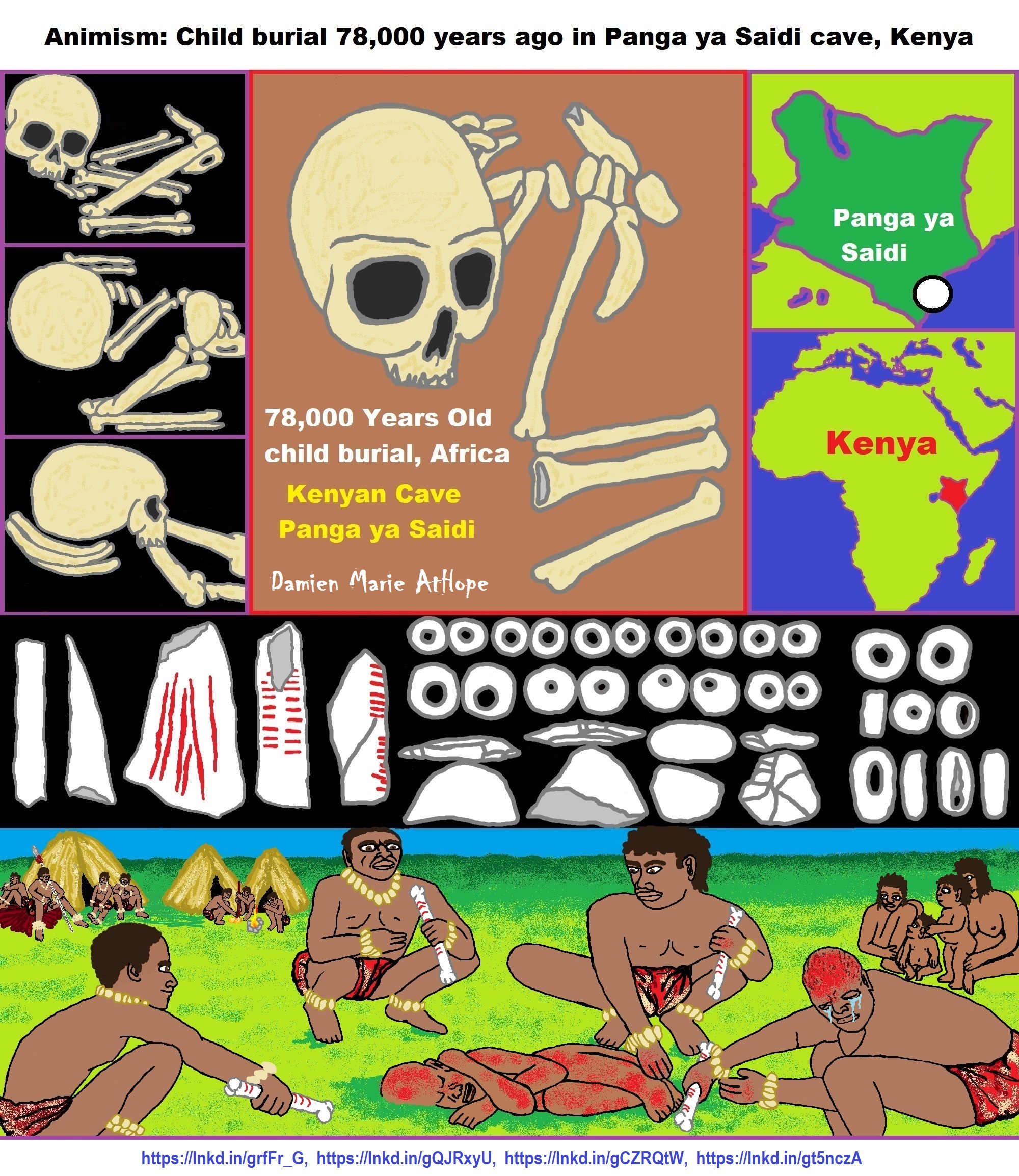

“Mtoto’s burial, to experts it is believed the child was around three years old when they died and was likely wrapped in a shroud and had their head on a pillow. Besides the seemingly deliberate position of the body, the team noticed a few clues that suggested the child was swaddled in cloth, possibly with the intention of preserving the corpse. They also speculate the body was placed in a cave fissure — known as funerary caching — before being covered with sediment.” ref, ref

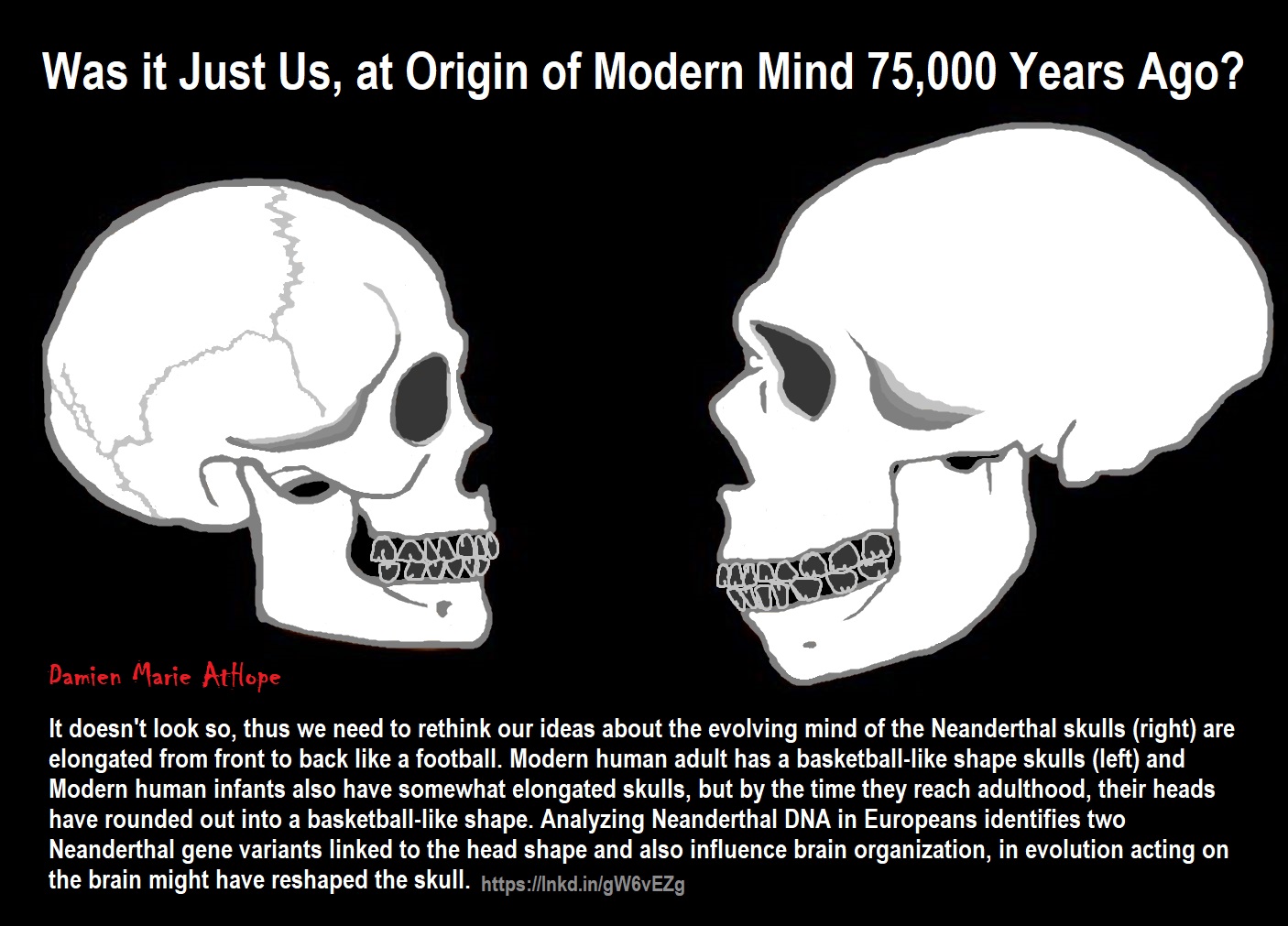

Was it Just Us, at Origin of Modern Mind 75,000 Years Ago?

It doesn’t look so, thus we need to rethink our ideas about the evolving mind of the Neanderthal skulls (right) are elongated from front to back like a football. Modern human adult has a basketball-like shape skulls (left) and Modern human infants also have somewhat elongated skulls, but by the time they reach adulthood, their heads have rounded out into a basketball-like shape. Analyzing Neanderthal DNA in Europeans identifies two Neanderthal gene variants linked to the head shape and also influence brain organization, in evolution acting on the brain might have reshaped the skull. Therefore, the Neanderthal DNA had a direct effect on brain shape and, presumably, brain function in humans today but infants start life with elongated skulls, somewhat like Neanderthals. ref

Evidence shows that Neanderthals had a complex culture although they did not behave in the same ways as the early modern humans who lived at the same time. Neanderthal dead were often buried, although there is no conclusive evidence for full ritualistic behavior, though at some sites, objects have been uncovered that may represent grave goods. ref

Animism: an approximately 100,000-year-old belief system?

Animism (from Latin anima, “breath, spirit, life”) is the religious belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and perhaps even words—as animated and alive. Animism is the oldest known type of belief system in the world that even predates paganism. It is still practiced in a variety of forms in many traditional societies. Animism is used in the anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of many indigenous tribal peoples, especially in contrast to the relatively more recent development of organized religions. Although each culture has its own different mythologies and rituals, “animism” is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples’ “spiritual” or “supernatural” perspectives. The animistic perspective is so widely held and inherent to most animistic indigenous peoples that they often do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to “animism” (or even “religion”); the term is an anthropological construct. ref

* “animist” Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife (you are a hidden animist/Animism : an approximately 100,000-year-old belief system Qafzeh: Oldest Intentional Burial of 15 individuals with red ocher and Border Cave: intentional burial of an infant with red ochre and a shell ornament (possibly extending to or from Did Neanderthals teach us “Primal Religion (Animism?)” 120,000 Years Ago, as they too used red ocher? well it seems to me it may be Neanderthals who may have transmitted a “Primal Religion (Animism?)” or at least burial and thoughts of an afterlife they seem to express what could be perceived as a Primal “type of” Religion, which could have come first is supported in how 250,000 years ago Neanderthals used red ochre and 230,000 years ago shows evidence of Neanderthal burial with grave goods and possibly a belief in the afterlife. Think of the idea that Neanderthals who may have transmitted a “Primal Religion” as crazy then consider this, it appears that Neanderthals built mystery underground circles 175,000 years ago. Evidence suggests that the Neanderthals were the first humans to intentionally bury the dead, doing so in shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. Exemplary sites include Shanidar in Iraq, Kebara Cave in Israel, and Krapina in Croatia. Or maybe Neanderthals had it transmitted to them Evidence of earliest burial: a 350,000-year-old pink stone ax with 27 Homo heidelbergensis. As well as the fact that the oldest Stone Age Art dates to around 500,000 to 233,000 Years Old and it could be of a female possibly with magical believed qualities or representing something that was believed to)

No, Religion and Gods were not Created due to fear of Lightning.

I hear some say that the fear of lightning-caused or inspired religion it most likely did not as it is not well represented in the most ancient religious forms like animism at least 100,000 years ago and rather seems to gain its importance around the time of agriculture after paganism around 12,000 years ago relating to the bull and was connected to the early goddess faiths connected to the worship of cereal grains believed to be goddesses and rain/thunderstorms/lightning the bull was worshiped as it was thought to help fertilize the goddess. To the animist, spirit believer the goal is to create the proper atmosphere so that spirits add their benefit and not their harm. All existence is connected commonly lacking strict or permanent divisions or distinctions between that seen as animate or inanimate, human or non-human and while there may be prescribed pattern to avoid discomfort to the spirits even a fear in doing so, animists don’t generally view themselves as a helpless or passive victim of the world nor do they hesitate in utilizing almost any means which will provide protection as it is merely a way of relating effectively in the world. ref

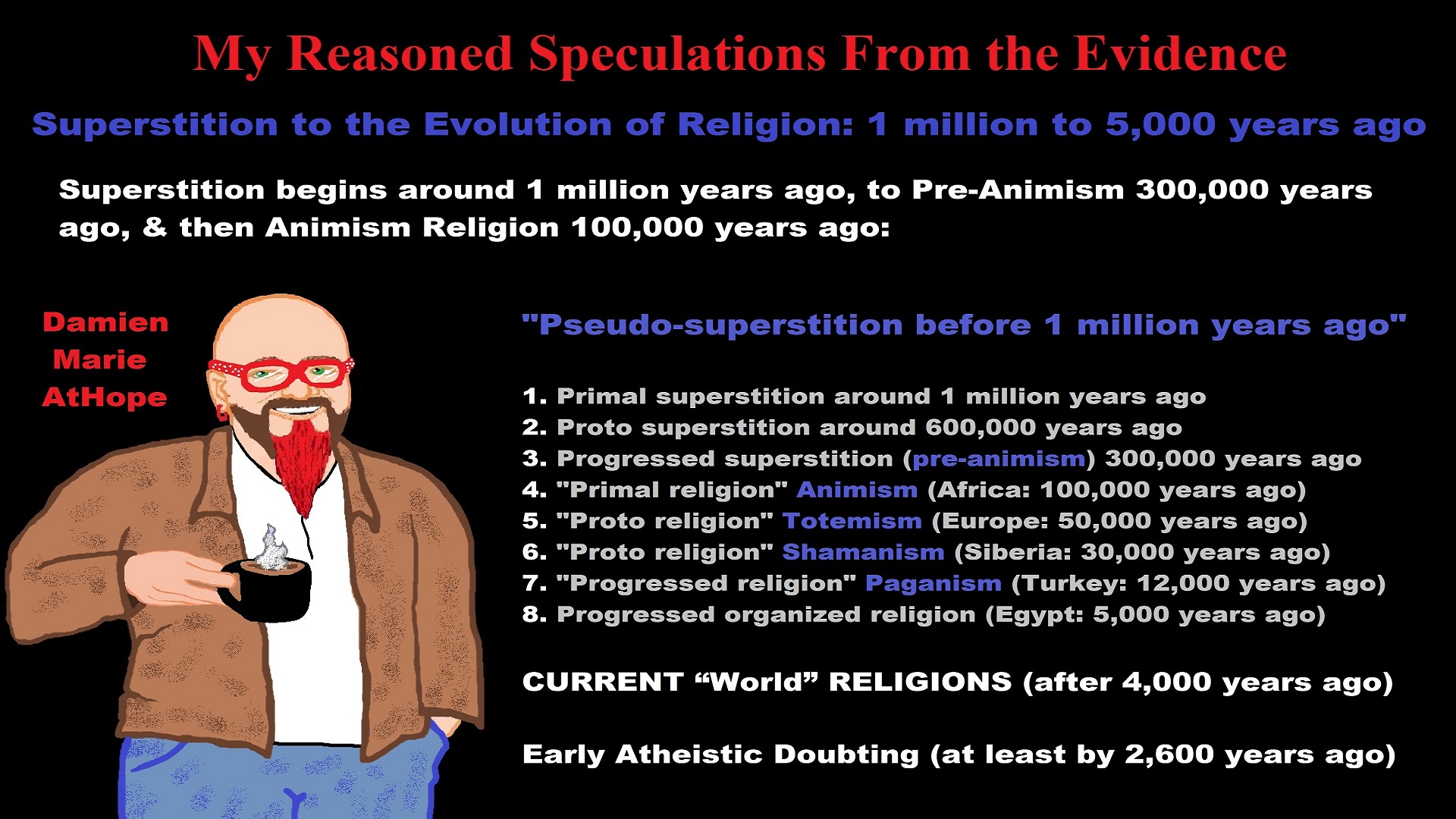

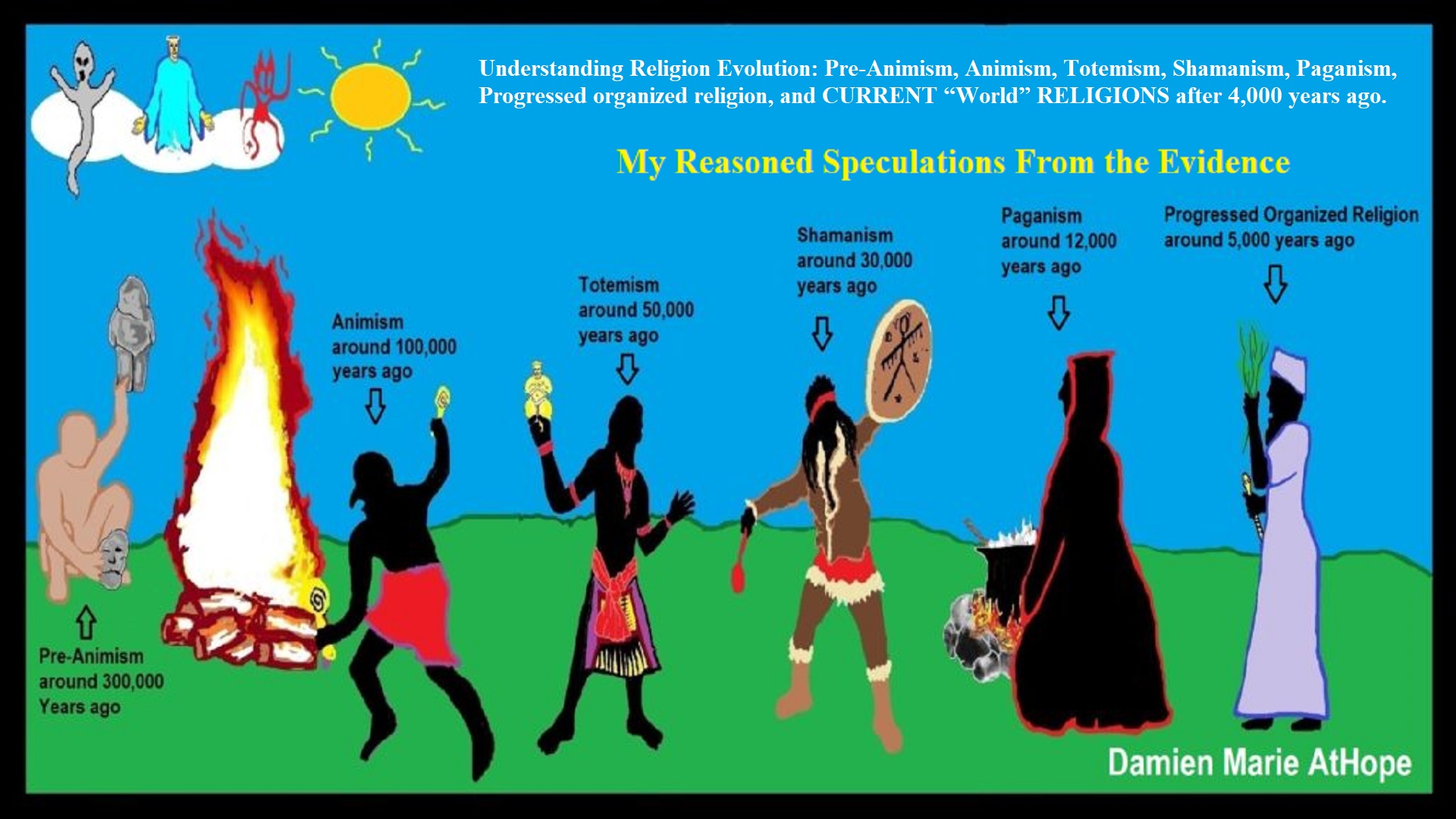

Understanding Religion Evolution

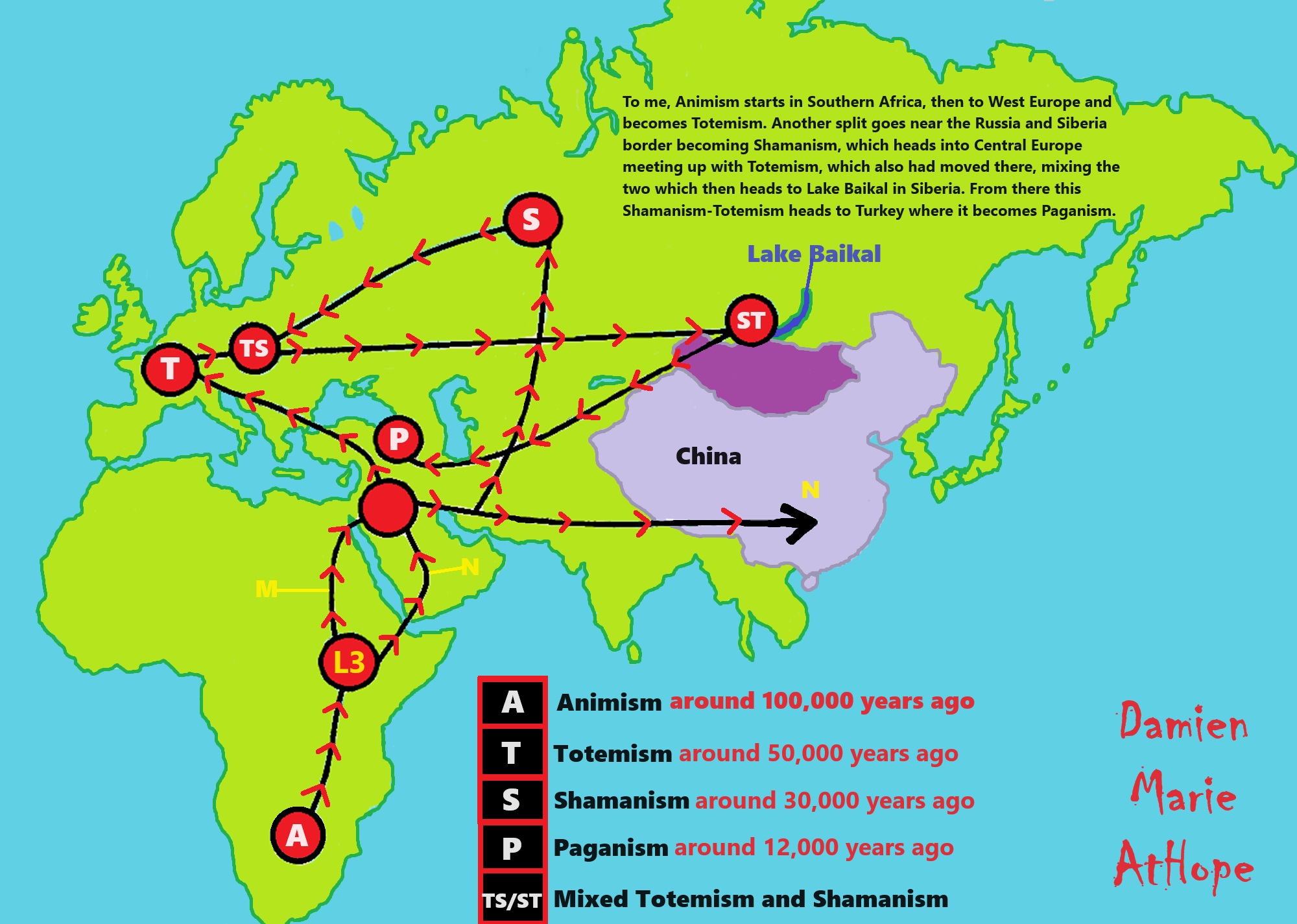

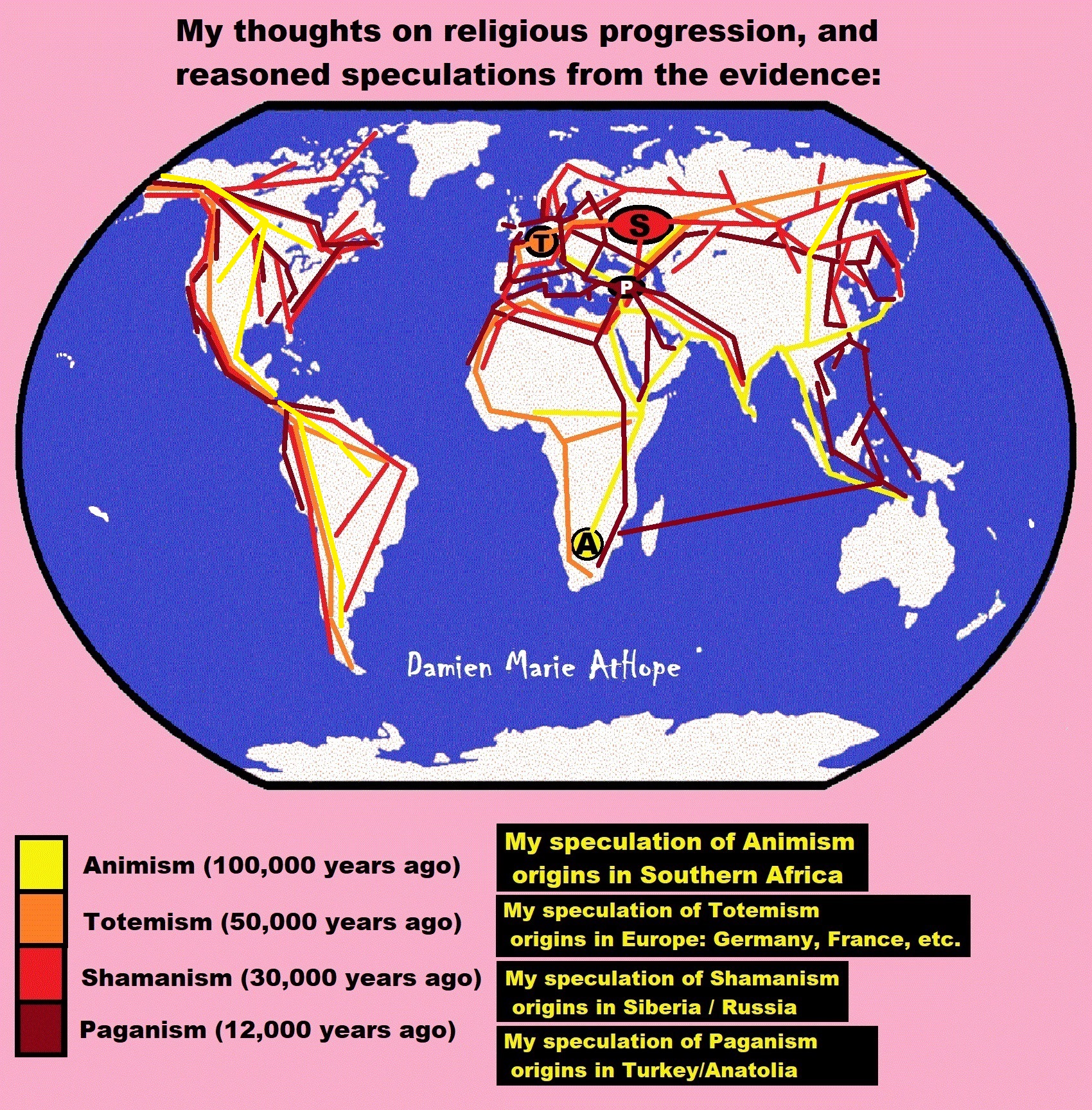

My thoughts on Religion Progression

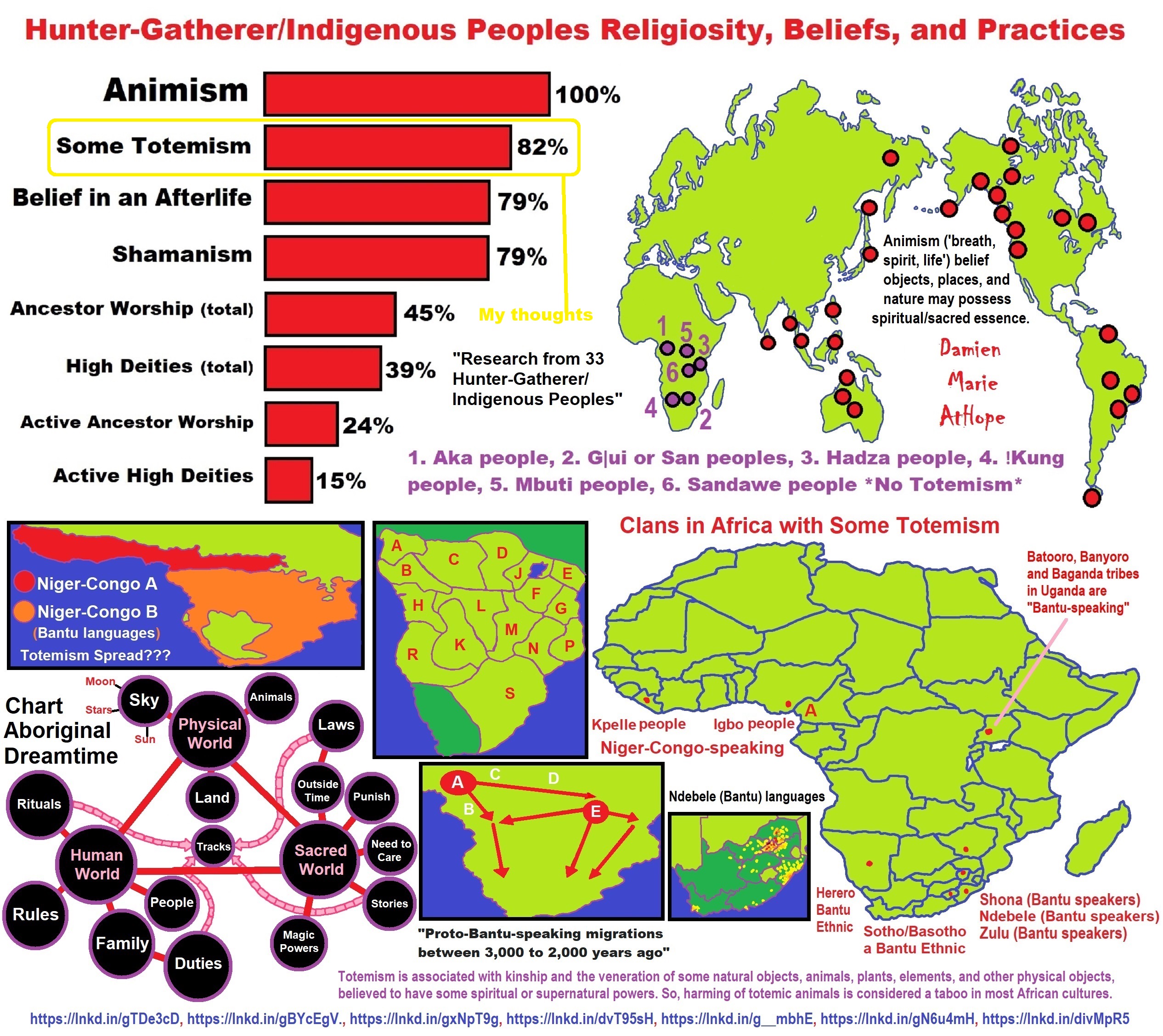

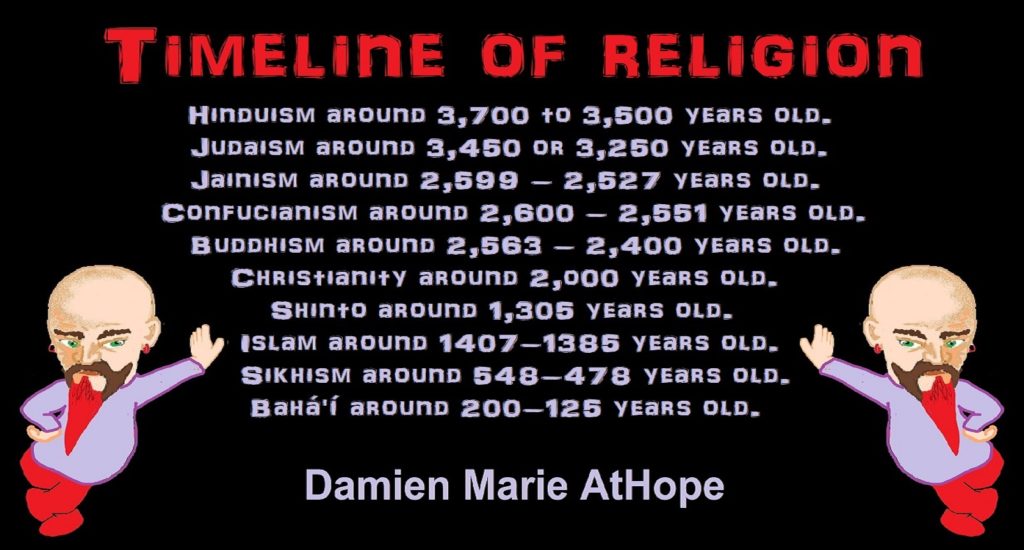

- Animism (a belief in a perceived spirit world) passably by at least 100,000 years ago “the primal stage of early religion”

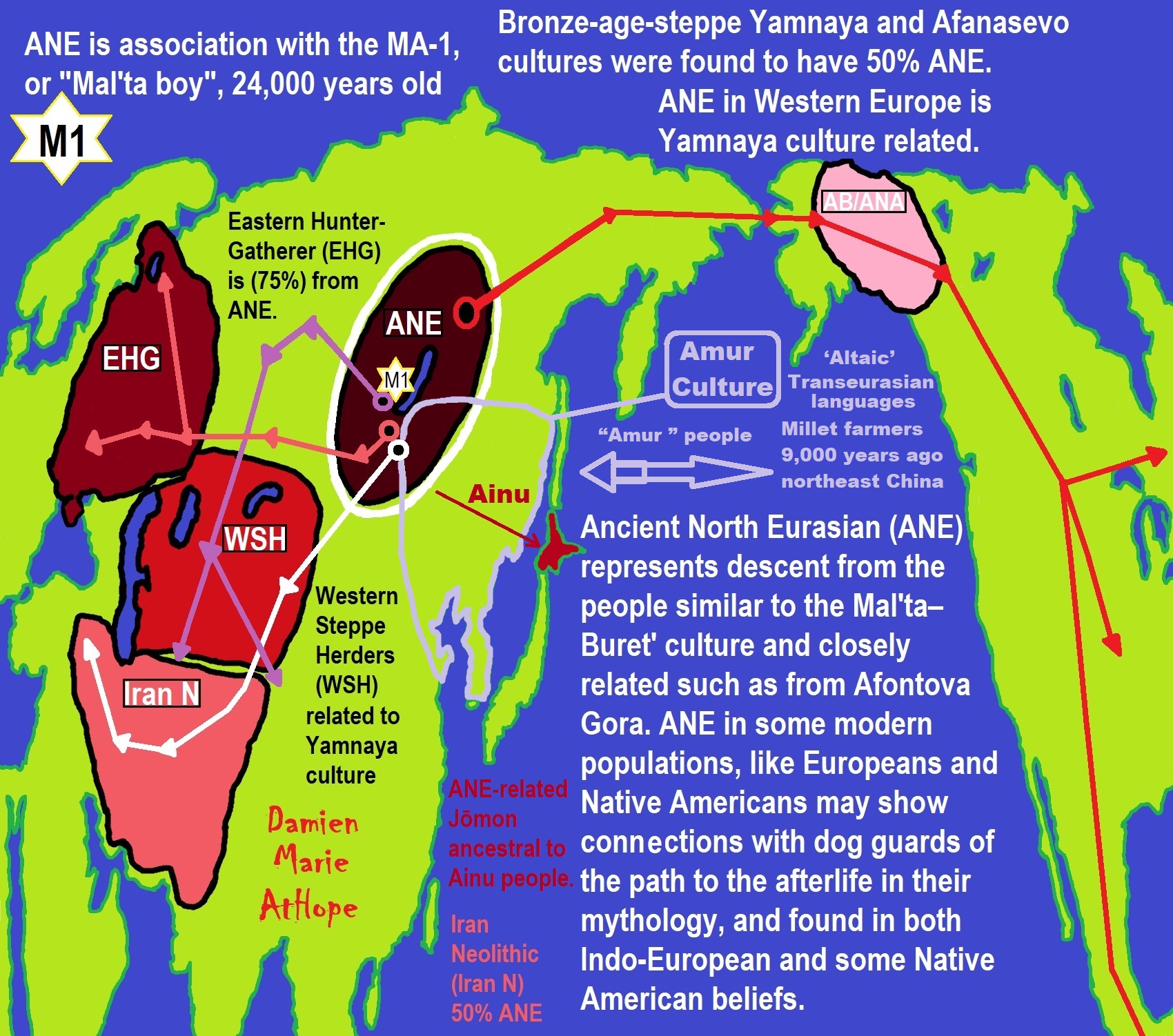

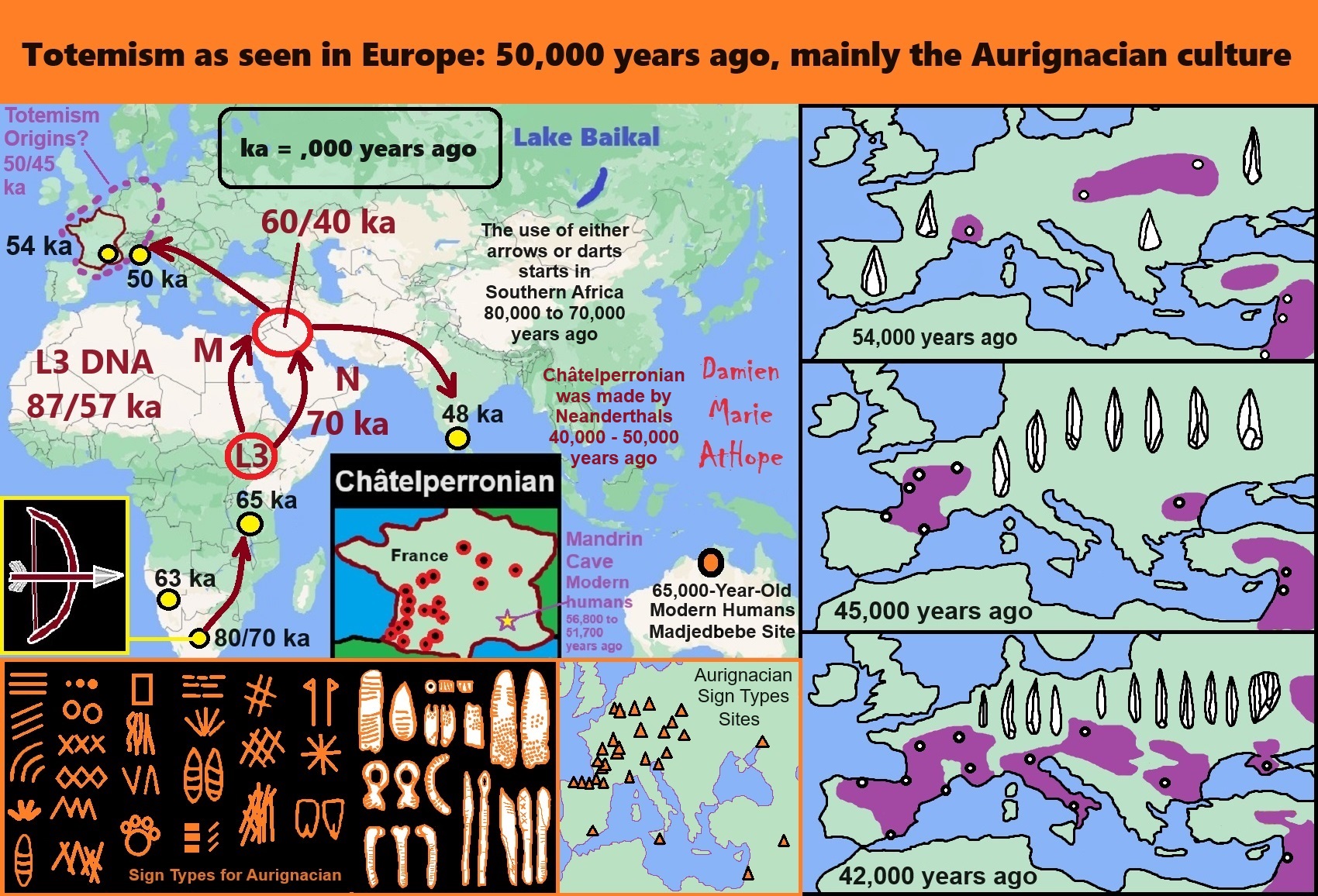

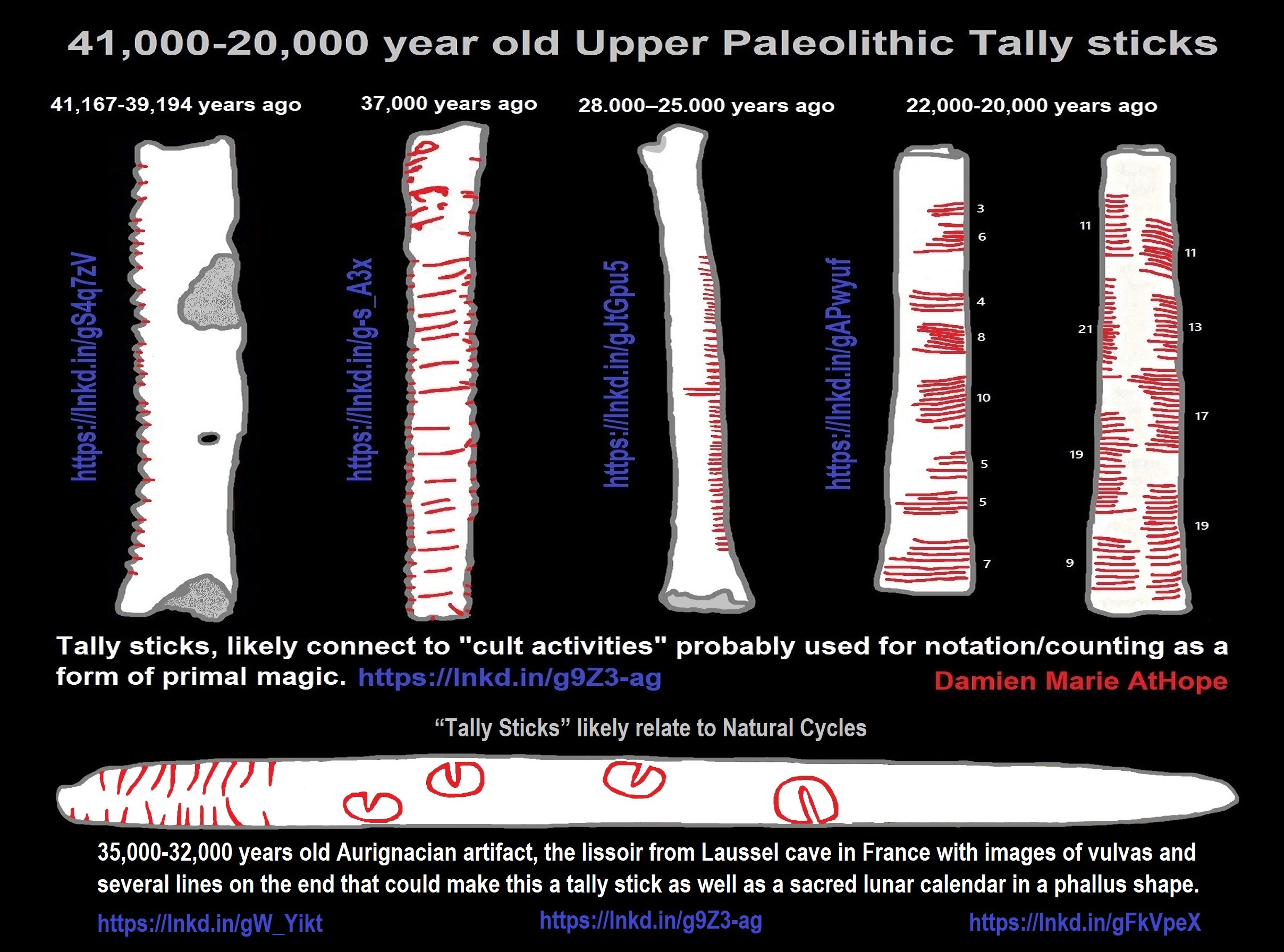

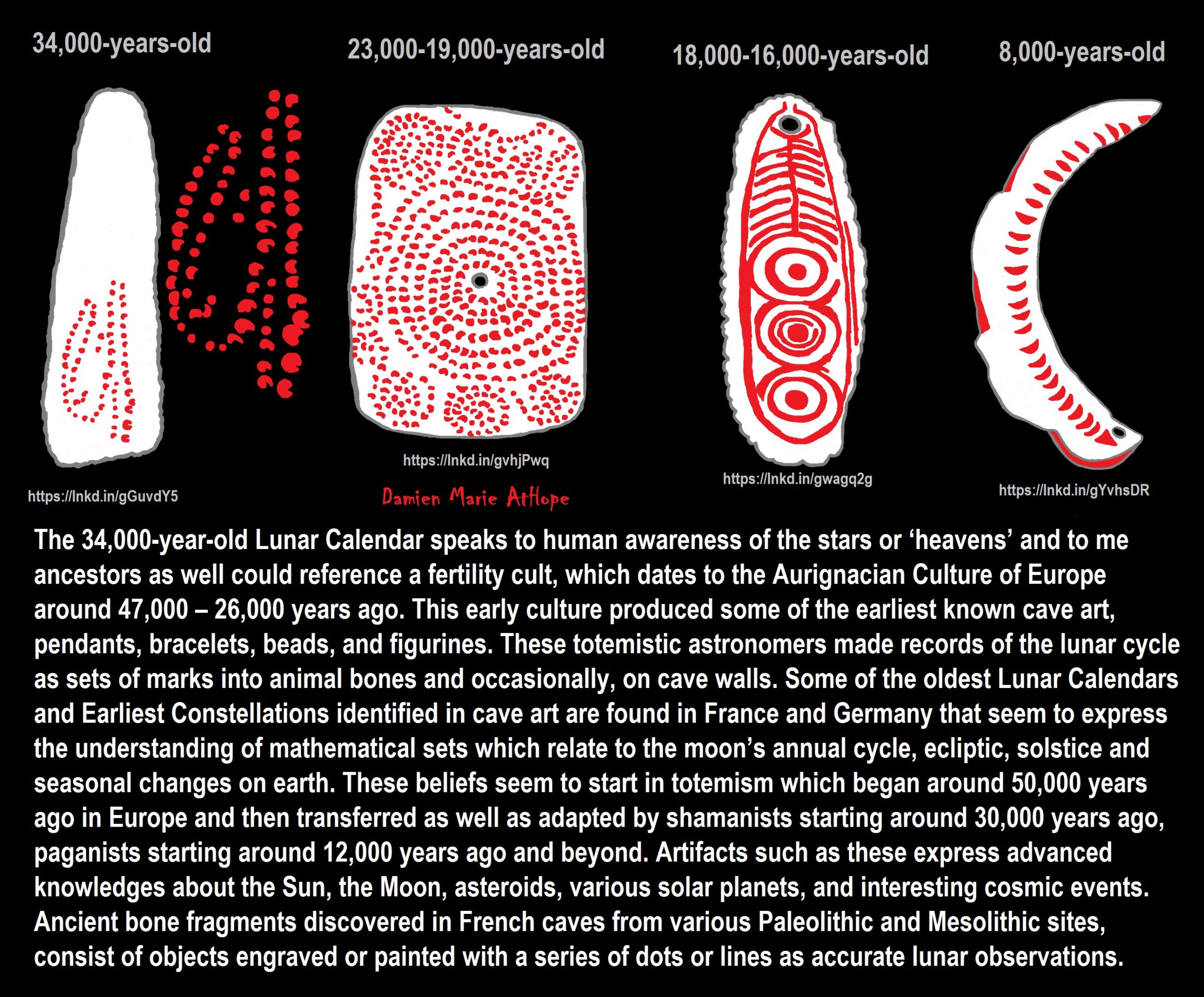

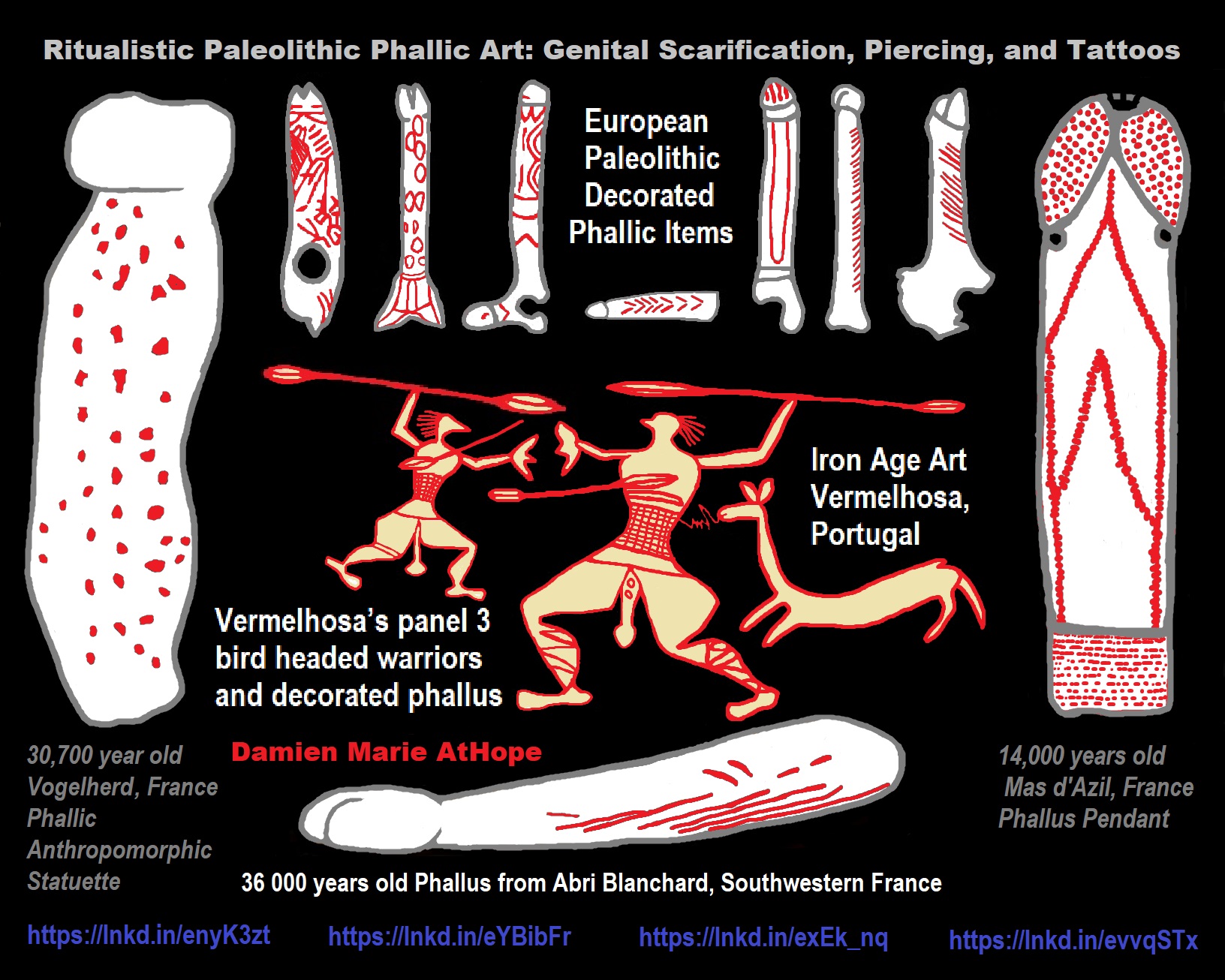

- Totemism (a belief that these perceived spirits could be managed with created physical expressions) passably by at least 50,000 years ago “progressed stage of early religion”

- Shamanism (a belief that some special person can commune with these perceived spirits on the behalf of others by way rituals) passably by at least 30,000 years ago

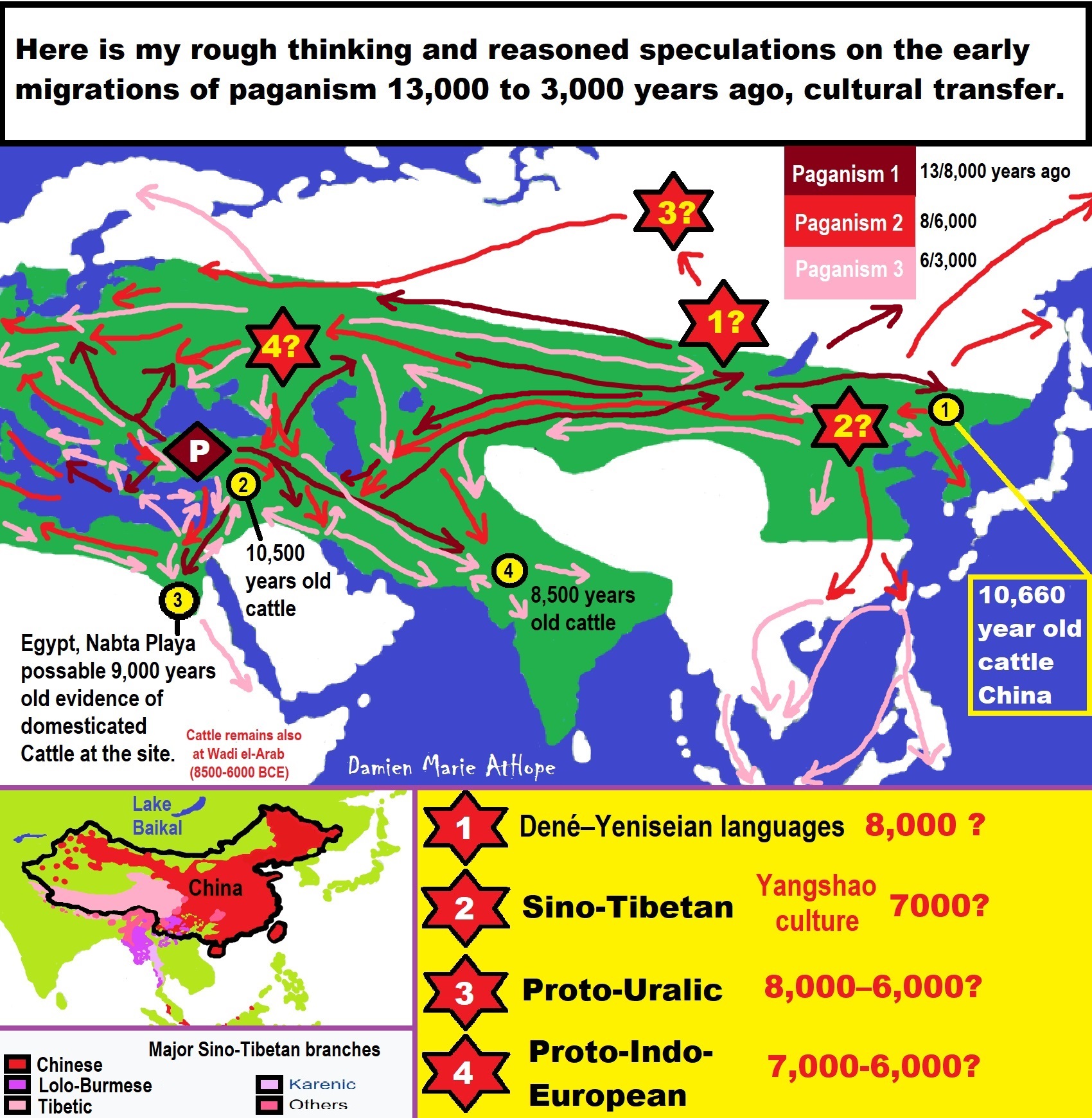

- Paganism “Early organized nature-based religion” mainly like an evolved shamanism with gods (passably by at least 12,000 years ago).

- Institutional religion “organized religion” as a social institution with official dogma usually set in a hierarchical/bureaucratic structure that contains strict rules and practices dominating the believer’s life.

“Religion is an Evolved Product”

What we don’t understand we can come to fear. That which we fear we often learn to hate. Things we hate we usually seek to destroy. It is thus upon us to try and understand the unknown or unfamiliar not letting fear drive us into the unreasonable arms of hate and harm.

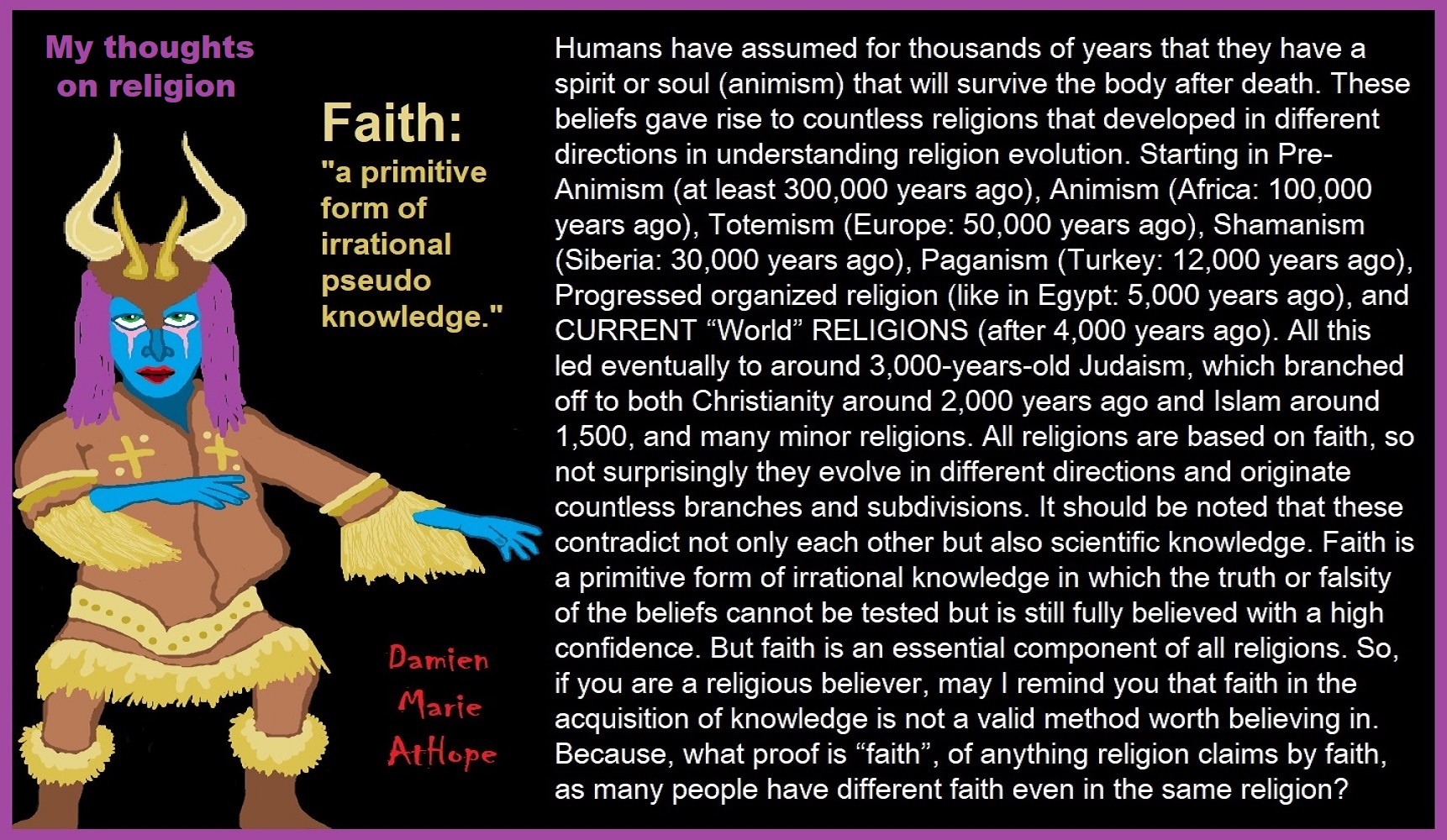

“An Archaeological/Anthropological Understanding of Religion Evolution”

If you are a religious believer, may I remind you that faith in the acquisition of knowledge is not a valid method worth believing in. Because, what proof is “faith”, of anything religion claims by faith, as many people have different faith even in the same religion?

Did Neanderthals teach us “Primal Religion (Pre-Animism/Animism?)” 120,000 Years Ago?

Evidence suggests that the Neanderthals were the first humans to intentionally bury the dead, doing so in shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. 130,000 years ago – Earliest undisputed evidence for intentional burial. Neanderthals bury their dead at sites such as Krapina in Croatia. ref

Homo sapiens – is known to have reached the Levant between 120,000 and 90,000 years ago, but that exit from Africa evidently went extinct. ref

Homo sapiens – is known to have reached the Levant between 120,000 and 90,000 years ago, but that exit from Africa evidently went extinct. ref

A population that diverged early from other modern humans in Africa contributed genetically to the ancestors of Neanderthals from the Altai Mountains roughly 100,000 years ago. By contrast, we do not detect such a genetic contribution in the Denisovan or the two European Neanderthals. In addition to later interbreeding events, the ancestors of Neanderthals from the Altai Mountains and early modern humans met and interbred, possibly in the Near East, many thousands of years earlier than previously thought. ref

In 2005, a set of 7 teeth from Tabun Cave in Israel were studied and found to most likely belong to a Neandertal that may have lived around 90,000 years ago ref

and another Neandertal (C1) from Tabun Cave was estimated to be in northern Israel. The limb bones are characteristic of Neanderthals, whereas the lower jaw has a combination of Neanderthal and earlier features. These fossils date from more than 150,000 years ago ref

A fossilized human jawbone in a collapsed cave in Israel that they said is between 177,000 and 194,000 years old. ref

The Tabun Cave contains a Neanderthal-type female, dated to about 120,000 years ago. It is one of the most ancient human skeletal remains found in Israel. ref

Objects at Tabun suggests that ancestral humans used fire at the site on a regular basis since about 350,000 years ago. ref

The remains of seven adults and three children were found, some of which (Skhul;1,4, and 5) are claimed to have been burials. ref

Assemblages of perforated Nassarius shells (a marine genus) significantly different from local fauna have also been recovered from the area, suggesting that these people may have collected and employed the shells as a bead as they are unlikely to have been used as food. ref

Skhul Layer B has been dated to an average of 81,000-101,000 years ago with the electron spin resonance method, and to an average of 119,000 years ago with the thermoluminescence method. ref

Skhul 5 had the mandible of a wild boar on its chest. The skull displays prominent supraorbital ridges and jutting jaw, but the rounded braincase of modern humans. When found, it was assumed to be an advanced Neanderthal, but is today generally assumed to be a modern human, if a very robust one. ref, ref

It is possible that Neandertals and early moderns did make contact in the region and it may be possible that the Skhul and Qafzeh hominids are partially of Neandertal descent. Non-African modern humans contain 1-4% Neandertal genetic material, with hybridization possibly having taken place in the Middle East. ref

It has been suggested, however, that the Skhul/Qafzeh hominids represent an extinct lineage. If this is the case, modern humans would have re-exited Africa around 70,000 years ago, crossing the narrow Bab-el-Mandeb strait between Eritrea and the Arabian Peninsula. ref

Modern humans were present in Arabia and South Asia earlier than currently believed, and probably coincident with the presence of Homo sapiens in the Levant between ca 130 and 70,000 years ago. ref

This is the same route proposed to have been taken by the people who made the modern tools at Jebel Faya. ref

This Neandertal girl’s toe bone had ancient DNA her ancestors picked up by mating with modern humans more than 100,000 years ago. ref

If the Skhul burials took place within a relatively short time span, then the best age estimate lies between 100 and 135 ka. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the material associated with the Skhul IX burial is older than those of Skhul II and Skhul V. These and other recent age estimates suggest that the three burial sites, Skhul, Qafzeh, and Tabun are broadly contemporaneous, falling within the time range of 100 to 130 ka. The presence of early representatives of both early modern humans and Neanderthals in the Levant during Marine Isotope Stage 5 inevitably complicates attempts at segregating these populations by date or archaeological association. Nevertheless, it does appear that the oldest known symbolic burials are those of early modern humans at Skhul and Qafzeh. This supports the view that, despite the associated Middle Palaeolithic technology, elements of modern human behavior were represented at Skhul and Qafzeh prior to 100 ka. ref

As some of the first bands of modern humans moved out of Africa, they met and mated with Neandertals about 100,000 years ago—perhaps in the fertile Nile Valley, along the coastal hills of the Middle East, or in the once-verdant Arabian Peninsula. These early modern humans’ own lineages died out, and they are not among the ancestors of living people. But a small bit of their DNA survived in the toe bone of a Neandertal woman who lived more than 50,000 years ago in Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia, Russia. ref

100,000 years ago – The oldest known ritual burial of modern humans at Qafzeh in Israel: a double burial of what is thought to be a mother and child. The bones have been stained with red ochre. By 100,000 years ago anatomically modern humans migrated to the middle east from Africa. However, the fossil record of these humans ends after 100kya, leading scholars to believe that the population either died out or returned to Africa. 100,000 to 50,000 years ago – Increased use of red ochre at several Middle Stone Age sites in Africa. Red Ochre is thought to have played an important role in ritual. The human skeletons were associated with red ochre which was found only alongside the bones, suggesting that the burials were symbolic in nature. ref

Within Israel’s Qafzeh Cave, researchers found evidence of a sophisticated culture and remains of modern humans that are up to 100,000 years old. About 100,000 years ago, tall, long-limbed humans lived in the caves of Qafzeh, east of Nazareth, and Skhul, on Israel’s Mount Carmel. The Skhul-Qafzeh people gathered shells from a shoreline more than 20 miles away, decorated them, and strung them as jewelry. They buried their dead, most likely with grave goods, and cared for their living: A child born with hydrocephalus, sometimes called water on the brain, lived with a profound disability until the age of 3 or so, a feat only possible with patient, loving care. The Qafzeh humans were around 92,000 years old, and the Skhul people were even older, averaging about 115,000 years. Around 75,000 years ago, close to the time, the Homo sapiens of Skhul and Qafzeh disappear from the fossil record, the climate in the Levant shifted in Neanderthals’ favor. Rapid glaciation left the region both cooler and drier. Steppe-deserts advanced, and forests retreated. Neanderthal bodies were adapted for colder conditions. Their stocky, barrel-chested build lost less heat and offered plenty of insulating muscle, and their systems were streamlined to extract calories from food and turn them into body heat. The Skhul-Qafzeh people’s slender physiques were better at getting rid of heat than making it. Or, as Shea says, “Neanderthals liked cold and dry. Our ancestors liked warm and wet. It got cold, and humans retreated.” ref, ref

Neanderthals may have transmitted:

“Primal Religion (Pre-Animism/Animism?)” or at least burial and thoughts of an afterlife may have been transferred from Neanderthals to arcane humans when they bread with them.

Neanderthals, also interbred with Homo erectus, the “upright walking man,” Homo habilis, the “tool-using man,” and possibly others which means they could have possibly learned some pre-animism ideas from one of them like that expressed in portable anthropomorphic art that could have related to so kind of ancestor veneration as well. ref

Pre-Animism (at least 300,000 years ago)

- Around 500,000 – 233,000 years ago, Oldest Anthropomorphic art (Pre-animism) is Related to Female

- 400,000 Years Old Sociocultural Evolution

- Pre-Animism: Portable Rock Art at least 300,000-year-old

- Homo Naledi and an Intentional Cemetery “Pre-Animism” dating to around 250,000 years ago?

First, there was Pre-Animism: Portable Rock Art

Around a million years ago, I surmise that Pre-Animism, “animistic superstitionism”, began and led to the animistic somethingism or animistic supernaturalism, which is at least 300,000 years old and about 100,00 years ago, it evolves to a representation of general Animism, which is present in today’s religions.

Anthropology states that Pre-animism is “A stage of religious development supposed to have preceded animism, in which material objects were believed to contain spiritual energy.” ref

To me, it is a kind of “Primal Pre-Religion (Pre-Animism/Proto-Animism” or at least burial and thoughts of an afterlife, may have been transferred from the Neanderthals to arcane humans when they bred with them. Neanderthals, also interbred with Homo erectus, the ‘upright walking man,’ Homo habilis, the ‘tool-using man” and possibly others, which means they could have possibly learned some pre-animism ideas from one of the other hominids thas is expressed in portable anthropomorphic art, which could have been related to some kind of ancestor veneration as well. ref

Around 500,000 to 400,000 years ago, the earliest European hominin crania associated with Acheulean handaxes are at the sites of Arago, Atapuerca Sima de los Huesos, and Swanscombe. The Atapuerca fossils and the Swanscombe cranium belong to the Neandertals whereas the Arago hominins have been attributed to Homo heidelbergensis or to a subspecies of Homo erectus, which is an incipient stage of Neandertal evolution. A cranium (Aroeira 3) from the Gruta da Aroeira (Almonda karst system, Portugal) dating to 436,000 to 390,000 years ago provides important evidence on the earliest European Acheulean-bearing hominins as well as could show a transfer of ideas. ref

Homo erectus, the “upright walking man,” lived between 1.89 million and 143,000 years ago, whereas early African Homo erectus and sometimes called Homo ergaster are the oldest known early humans to have possessed modern human-like attributes. The earliest evidence of campfires occurred during the time of Homo erectus. While there is evidence that campfires were used for cooking, and probably sharing food, they are likely to have been placed for social interaction, used for warmth, to keep away large predators, and possibly even relating to Primal Religion, “Pre-Animism,” which may have included Fire Sacralizing and/or Worship. ref

Neanderthals used fire 400,000 years ago and there is evidence of a 300,000-year-old ‘campfire’ from Israel, which is not that surprising since our human ancestors have controlled fire from 1.5 million to 300,000 years ago and beyond. The benefits of fire are not only to cook food and fend off predators, but also extended their day and added to the community by how a fire in the middle of the darkness mellows and also excite people, which possibly inspire pre-animism’s “animistic superstitionism.” ref

Sun-worshipping baboons rise early to catch the African sunrise and race each other to the top for the best spots. Thus, we may rightly ponder how much did fireside tales aid to the socio-cultural-religious transformations or evolution. In the dark under flickering lights from the stars above and the fire below was the scene of wonder, fear, and mystery. Was superstition expanded and religion further imagined? It would seem that superstition was expanded and religion further imagined because both heavenly lights and flickering fire have been sacralized. This does seem to be somewhat supported by a researcher who spent 40 years studying African Bushmen who gathered evidence of the importance of gathering around a nighttime campfire as a time for bonding, social information, and shared emotions with fireside tales. This may provide a correlation that our prehistoric ancestors likely lived in a similar way to how the Bushmen currently do. Although, we cannot directly peer into the past or fully know the past from the indigenous Bushmen, these people do live in a way that our ancient ancestors lived for around 99% of our evolution.

Fire, as sacred or magic, can be seen in:

- Consuming fire as volcanos/lightning as gods and gods’power/vengeance.

- Holy fire as a means of transformation or magical purification.

- A magical being as used in worshipping the sun or punishment such as hell/lake of fire, which could be seen as mixing fire and water, if only symbolically.

- Ceremonies such as bonfires, eternal flames, or sacred candles/incense/lights/lamps are in one form or another incorporated in many faiths such as judaism, christianity, islam, hinduism, buddhism, sikhism, bahaism, shintoism, taoism, etc. ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

All this worship of fire/sun is hardly special to humans since many other primates worship thunderstorms, others fire, or sunrises. We have forgotten how nature worship, animistic superstitionism, animistic somethingism, or animistic supernatralism is presented in today’s religion. The mega religions now think they are removed from animistic superstitionism, which they are not. Their rituals, beliefs, and prayers have a connection to animism nature worship but are more hidden or stylized such as burning candles, which is worshipping fire.

Archaeology reveals that the world’s oldest sculpture was enhanced by hominid hand. To date, the oldest known human three-dimensional representation is the Tan-Tan sculpture, which is an anthropomorific human form from Morocco was found in ancient river deposits of the Draa river. It is Acheulian and has been dated between 500,000 to 300,000 years old. 500,000 to 233,000 years ago, in Israel, another sculpture, which may be the oldest Stone Age Art was found at the Berekhat Ram site on the Golan Heights that consist of a small quartzite pebble, which resembles a human female figure with magical believed qualities or representing something that was believed to be magical. ref

Is this just art or a form of ancestor veneration?

Pre-animism ideas can be seen in rock art such as that expressed in portable anthropomorphic art, which may be related to some kind of ancestor veneration. This magical thinking may stem from a social or non-religious function of ancestor veneration, which cultivates kinship values such as filial piety, family loyalty, and continuity of the family lineage. Ancestor veneration occurs in societies with every degree of social, political, and technological complexity and it remains an important component of various religious practices in modern times.

Humans are not the only species, which bury their dead. The practice has been observed in chimpanzees, elephants, and possibly dogs. Intentional burial, particularly with grave goods, signify a “concern for the dead” and Neanderthals were the first human species to practice burial behavior and intentionally bury their dead, doing so in shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. Exemplary sites include Shanidar in Iraq, Kebara Cave in Israel and Krapina in Croatia. The earliest undisputed human burial dates back 100,000 years ago with remains stained with red ochre, which show ritual intentionality similar to the Neanderthals before them. ref, ref

- “300,000 years ago: the first possible appearance of Homo sapiens, in Jebel Irhoud, Morocco.

- 270,000 years ago: age of Y-DNA haplogroup A00(“Y-chromosomal Adam“).

- 250,000 years ago: the first appearance of Homo neanderthalensis (Saccopastore skulls)

- 250,000-200,000 years ago: modern human presence in West Asia (Misliya cave)

- 230,000–150,000 years ago: age of mt-DNA haplogroup L (“Mitochondrial Eve“)

- 195,000 years ago: Omo remains (Ethiopia), the emergence of anatomically modern humans.

- 160,000 years ago: Homo sapiens idaltu

- 170,000 years ago: humans are wearing clothing by this date.

- 150,000 years ago: Peopling of Africa: Khoisanid separation, an age of mtDNA haplogroup L0

- 125,000 years ago: the peak of the Eemian interglacial period.

- 120,000–90,000 years ago: Abbassia Pluvial in North Africa—the Sahara desert region is wet and fertile.” ref

Pre-Animism: Portable Rock Art

Pre-animism ideas seen in rock art, such as that expressed in portable anthropomorphic art that could have related to so kind of ancestor veneration, which may be a magical thinking but stem from the social or non-religious function of ancestor veneration is to cultivate kinship values, such as filial piety, family loyalty, and continuity of the family lineage. Ancestor veneration occurs in societies with every degree of social, political, and technological complexity, and it remains an important component of various religious practices in modern times. Ancestor reverence is not the same as the worship of a deity or deities. In some Afro-diasporic cultures, ancestors are seen as being able to intercede on behalf of the living, often as messengers between humans and the gods. As spirits who were once human themselves, they are seen as being better able to understand human needs than would a divine being. In other cultures, the purpose of ancestor veneration is not to ask for favors but to do one’s filial duty. Some cultures believe that their ancestors actually need to be provided for by their descendants, and their practices include offerings of food and other provisions. Others do not believe that the ancestors are even aware of what their descendants do for them, but that the expression of filial piety is what is important. Although there is no generally accepted theory concerning the origins of ancestor veneration, this social phenomenon appears in some form in all human cultures documented so far. David-Barrett and Carney claim that ancestor veneration might have served a group coordination role during human evolution, and thus it was the mechanism that led to religious representation fostering group cohesion. Humans are not the only species that bury their dead; the practice has been observed in chimpanzees, elephants, and possibly dogs. Intentional burial, particularly with grave goods, signifies a “concern for the dead” and Neanderthals were the first human species to practice burial behavior and intentionally bury their dead, doing so in shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. Exemplary sites include Shanidar in Iraq, Kebara Cave in Israel, and Krapina in Croatia. The earliest undisputed human burial dates back 100,000 years with remains stained with red ochre showing ritual intentionality similar to the Neanderthals before them. ref, ref

Pre-animism: Anthropology; “A stage of religious development supposed to have preceded animism, in which material objects were believed to contain spiritual energy.” ref

Animism (from Latin anima, “breath, spirit, life”) is the religious belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and perhaps even words—as animated and alive. Animism is the oldest known type of belief system in the world that even predates paganism. It is still practiced in a variety of forms in many traditional societies. Animism is used in the anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of many indigenous tribal peoples, especially in contrast to the relatively more recent development of organized religions. Although each culture has its own different mythologies and rituals, “animism” is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples’ “spiritual” or “supernatural” perspectives. The animistic perspective is so widely held and inherent to most animistic indigenous peoples that they often do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to “animism” (or even “religion”); the term is an anthropological construct. ref

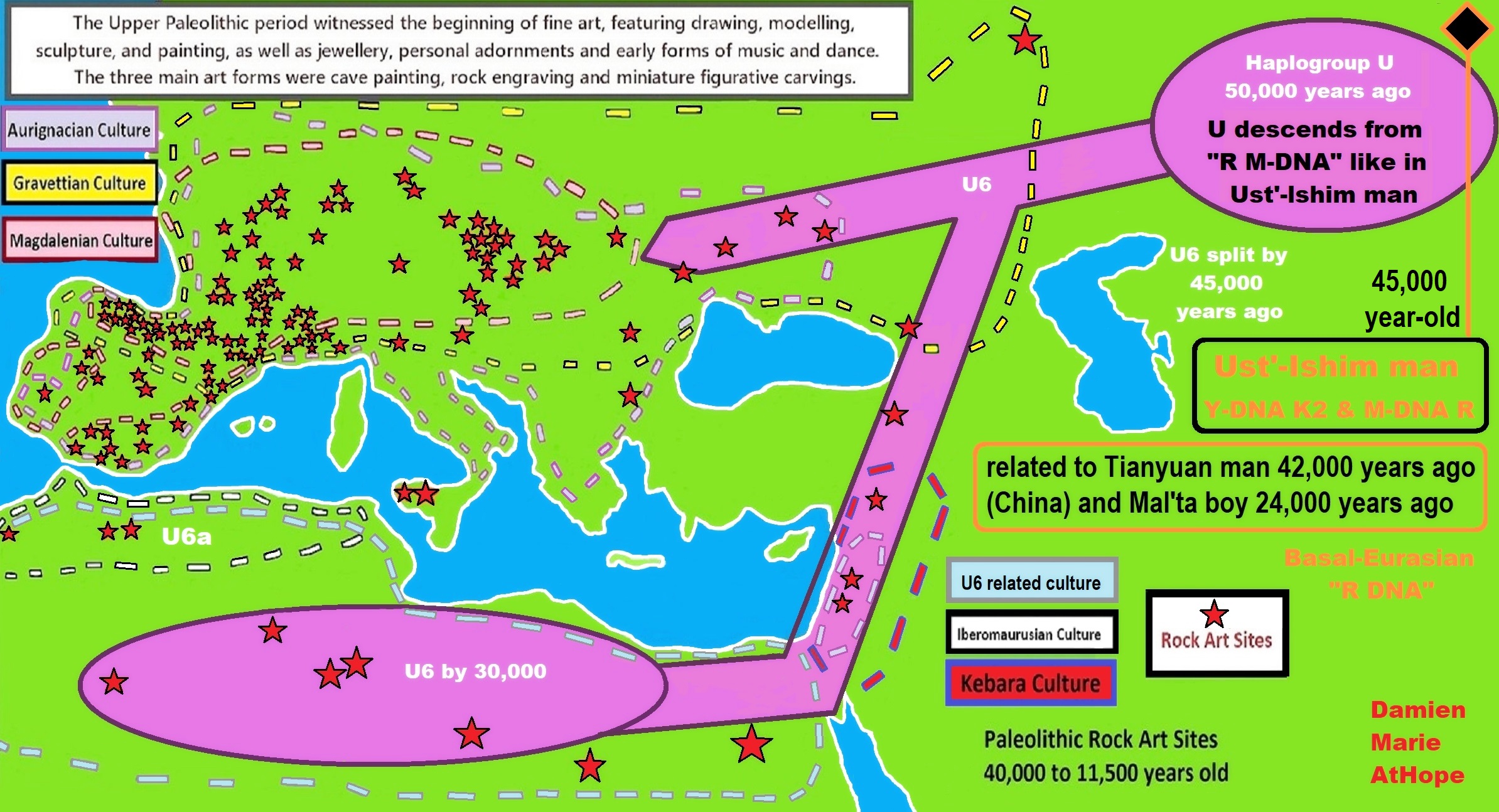

Animism (beginning around 100,000 years ago)

Animism (such as that seen in Africa: 100,000 years ago)

- Aterian Culture (North African 145,000–20,000 years ago)

- Sangoan Culture (sub-Saharan African 130,000-10,000 years ago)

- Animism: an approximately 100,000-year-old belief system?

- Rock crystal stone tools 75,000 Years Ago – (Spain) made by Neanderthals

- Stone Snake of South Africa: “first human worship” 70,000 years ago

- Similarities and differences in Animism and Totemism

- Did Neanderthals Help Inspire Totemism? Because there is Art Dating to Around 65,000 Years Ago in Spain?

- History of Drug Use with Religion or Sacred Rituals possibly 58,000 years ago?

Animism is approximately a 100,000-year-old belief system and believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife. If you believe like this, regardless of your faith, you are a hidden animist.

The following is evidence of Animism: 100,000 years ago, in Qafzeh, Israel, the oldest intentional burial had 15 African individuals covered in red ocher was from a group who visited and returned back to Africa. 100,000 to 74,000 years ago, at Border Cave in Africa, an intentional burial of an infant with red ochre and a shell ornament, which may have possible connections to the Africans buried in Qafzeh, Israel. 120,000 years ago, did Neanderthals teach us Primal Religion (Pre-Animism/Animism) as they too used red ocher and burials? ref, ref

It seems to me, it may be the Neanderthals who may have transmitted a “Primal Religion (Animism)” or at least burial and thoughts of an afterlife. The Neanderthals seem to express what could be perceived as a Primal “type of” Religion, which could have come first and is supported in how 250,000 years ago, the Neanderthals used red ochre and 230,000 years ago shows evidence of Neanderthal burial with grave goods and possibly a belief in the afterlife. ref

Do you think it is crazy that the Neanderthals may have transmitted a “Primal Religion”? Consider this, it appears that 175,000 years ago, the Neanderthals built mysterious underground circles with broken-off stalactites. This evidence suggests that the Neanderthals were the first humans to intentionally bury the dead, doing so in shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. Exemplary sites include Shanidar in Iraq, Kebara Cave in Israel, and Krapina in Croatia. Other evidence may suggest the Neanderthals had it transmitted to them by Homo heidelbergensis, 350,000 years ago, by their earliest burial in a shaft pit grave in a cave that had a pink stone ax on the top of 27 Homo heidelbergensis individuals and 250,000 years ago, Homo Naledi had an intentional cemetery in South Africa cave. ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

- “120,000–90,000 years ago: Abbassia Pluvial in North Africa—the Sahara desert region is wet and fertile.

- 120,000 to 75,000 years ago: Khoisanid back-migration from Southern Africa to East Africa.

- 82,000 years ago: small perforated seashell beads from Taforalt in Morocco are the earliest evidence of personal adornment found anywhere in the world.

- 75,000 years ago: Toba Volcano supereruption that almost made humanity extinct. Populations could have been lowered to about 3000-1000 people on the Earth.

- 70,000 years ago: earliest example of abstract art or symbolic art from Blombos Cave, South Africa—stones engraved with grid or cross-hatch patterns.

- 70,000 years ago: Recent African origin: separation of sub-Saharan Africans and non-Africans.” ref

143,000 – 120,000 Years Ago – Tabun Cave (Israel), found evidence of a Neanderthal-type burial of an archaic type of human female. There is some evidence of burial in Skhul Cave 130,000 – 100,000 which may be Neanderthal humans hybrids, thought early modern humans started engaging in burial around 100,000 years ago. So one should wonder did Neanderthals teach humans religion or at least ritual burial around 120,000 – 100,000 years ago? I think maybe it seems to possibly be the case by 100,000 years ago, but this is just my speculation of somewhat loose but interesting evidence. Burial seems to have been and is now certainly evidence of some concern about what happened when someone died perhaps even proof of a belief that would be one of the key tenets of most religions of the world today, which is life after this one.

100,000 Years Ago – Qafzeh cave (Israel), found a burial site of 15 early modern humans stained with red ochre and grave goods, 71 pieces of red ocher, and red ocher-stained stone tools near the bones suggest ritual or symbolic use, as well as seashells with traces of being strung, and a few also had ochre stains which may also suggest ritual or symbolic use. Likewise, a wild boar jaw found placed in the arms of one of the skeletons.

Only after 100,000 years ago modern human burials become more frequent. Could this seemingly new practice of barrel among early modern humans with the use of red ochre be in some way connected or influenced by the meeting, interbreeding, and possible idea sharing with the Neanderthal ancestors of the Neanderthals from the Altai Mountains of Central Asia around 100,000 years ago possibly in the Near East, maybe even in Israel or some other part of the with the levant? Well to me it sounds like a real possibility that Neanderthals may have directly taught or indirectly been observed thus in a way are responsible candidates for possibly teaching humans the beginnings of religion, or at least superstitionism/supernaturalism seen in the act of doing burial and the ritual and seemingly sacralized use of red ocher around 100,000 years ago. This thinking Neanderthals Primal Religion could have come first is supported in how 250,000 years ago Neanderthals used red ochre and 230,000 years ago shows evidence of Neanderthal burial with grave goods and possibly a belief in the afterlife.

*Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife (you are a hidden animist/Animism: an approximately 100,000-year-old belief system) Animism: the (often hidden) religion thinking all religionists (as well as most who say they are the so-called spiritual and not religious which to me are often just reverting back to have to Animism (even though this religious stance is often hidden to their realization so they are still very religious whether they know it or not) some extent or another. Ref

References: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Ancient human burials, By Sally McBrearty

Whereas with modern people, anatomically modern Homo sapiens from somewhat later in time, you find artifacts that are definitely grave offerings. You find quantities of red ochre, which have been sprinkled over the skeleton, beads, and other kinds of objects, bone tools, and things like that, which appear to have been placed in the grave with the person when they were interred. And there’s really no doubt that they’re deliberate burials. The evidence for the burial of the dead in Africa is very very spotty. There’s one site in South Africa that’s called Border Cave, where there are a number of burials, including the burial of an infant, with a little shell ornament, it’s a pierced sea shell ornament, and the argument has been about whether that is in good stratographic context or whether it is an intrusive burial into earlier deposits. And so the age of that is not particularly well established. If it is in good context, then it’s about 100,000 years old, and it is the earliest in Africa. There are early burials of anatomically modern Homo sapiens in Israel, from the site of Qafzeh. There is a modern human that probably dates to about the same time, about maybe 90,000 to 100,000 years ago. ref

Neandertal burials, By Sally McBrearty

The Neandertals have always been thought to bury their dead, because there’s so many complete skeletons of Neandertals that have been found. And I think from the number of skeletons that have been found, it’s probably a good guess that they were deliberately burying the dead. However, there are a lot of skeletons of other cave-dwelling animals that are found in caves: cave bears or hyenas, that because they live in caves they often die in caves. And there, people have argued about whether rock falls, or simply accidental death, or natural death, occurring in a cave could preserve whole skeletons better than in the open air. But the argument has also been about the objects that you find associated with the Neandertal burials, because what you find together with Neandertal skeletons are really mundane objects, like stone tools, or animal bones that would be food remains. ref

Chimpanzees Sacralizing Trees?

There is evidence currently limited to West Africa where chimpanzees mainly adult males but also females or juveniles are observed creating a kind of shrine of accumulated stone piles beside, or inside trees as well as regularly visiting these trees picking up these stones, and then throwing them at these trees accompanied with vocalization “performativity” which is (speech, gestures) to communicate an action.

Chimpanzees have been observed engaging in “social learning,” both teaching and learning such as tool use as well as communication signals: vocal and gestures. Such social learning is seen as playing an important and unique role in the development of human language, culture, and mythologizing.

All together such things observed in these West Africa where chimpanzees could indicate some kind of what could be perceived as magical thinking or at least quasi-magical thinking in the sacralizing of trees as it does not seem connected to some utilitarian or food foraging practice of which rocks or tools would make since. This at first may sound too complex for a nonhuman animal but what needs to be understood is that chimpanzees have been known to exhibit “metacognition,” or think about thinking.

Also, chimpanzees have the greatest variation in tool-use behaviors of any animal, second only to humans, where humans seem to have magical thinking or irrational beliefs are hardwired in our brains at a very ancient level because they involve mentally-fabricated patterns of thinking. Moreover, such processing abilities are somewhat common among non-human primates if not lower mammals as well to some extent and can be seen as a part of evolutionary survival fitness and thus not uniquely human.

It can be thought that different emotions evolved at different times with fear being ancient care for offspring relatively next later followed likely by extended social emotions, such as guilt and pride, evolved among social primates. Why this could be important is it is believed that emotions evolved to reinforce memories of patterns adding to survival and reproduction as well as responses to internal or external events and in such remapping facilitated by emotions could involve mentally-fabricated patterns of thinking which could superstitionize things in the world that do not truly limit it to the way it is possibly adding a kind of animism or the like involving some amount of magical thinking such as sacralizing of trees.

Magical thinking such as beliefs that there are relationships between behaviors or sounds thought to have the ability to directly affect other events in the world. Whereas quasi-magical thinking is acting as if there is a false belief that action influences outcome, even though they may not really actualize or intentionally hold such a belief.

Now I doubt West African chimpanzees are fully mythologizing the trees to a human magical thinking extent but we can see some possibilities of what about them could be inspired by magical thinking. Magical thinking may lead to a type of causal reasoning or causal fallacy that looks for meaningful relationships of grouped phenomena (coincidence) between acts and events.

Moreover, magical thinking when applied to trees are significant as believed sacred totems and natural sacred representations in many of the world’s oldest myths possibly because of using magical thinking when observing the growth and annual death and then revival of their foliage, seen them as symbolic representations of growth, death, and rebirth.

As well as trees may be conceived as existing in three realms the underworld or death with the roots the world of the living the trunk existing in our world above the ground and its branches reaching to the heavens thus existing in the realm of the spirits, ancestors or gods.

An Old Branch of Religion Still Giving Fruit: Sacred Trees

References 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, and Paganism

The interconnectedness of religious thinking Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, and Paganism

So, it all starts in a general way with Animism (theoretical belief in supernatural powers/spirits), then this is physically expressed in or with Totemism (theoretical belief in mythical relationship with powers/spirits through a totem item), which then enlists a full-time specific person to do this worship and believed interacting Shamanism (theoretical belief in access and influence with spirits through ritual), and then there is the further employment of myths and gods added to all the above giving you Paganism (often a lot more nature-based than most current top world religions, thus hinting to their close link to more ancient religious thinking it stems from). My hypothesis is expressed with an explanation of the building of a theatrical house (modern religions development).

Religion and it’s fixation with holy land or places which is both an animism belief that areas or natural features have a sacredness and the totemistic clan thinking that a tribe of people own areas or natural features as some sacred right, often along with believing only they belong there, sometimes and n some places outsiders or those not deemed sacred enough are excluded or harmed even possibly killed. Similar to sectarianism, isolationism, extreme nationalism, ethnocentrism, racism, is one of the most decisive factors leading to harmful effects and death in the past, present, and likely into the future. Yes, you need to know about Animism to understand Religion

Hidden Religious Expressions: “animist, totemist, shamanist & paganist”

- *Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife (you are a hidden animist/Animism : an approximately 100,000-year-old belief system)

- *Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife can be attached to or be expressed in things or objects (you are a hidden totemist/Totemism: an approximately 50,000-year-old belief system)

- *Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife can be attached to or be expressed in things or objects and these objects can be used by special persons or in special rituals can connect to spirit-filled life and/or afterlife (you are a hidden shamanist/Shamanism: an approximately 30,000-year-old belief system)

- *Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife can be attached to or be expressed in things or objects and these objects can be used by special persons or in special rituals can connect to spirit-filled life and/or afterlife who are guided/supported by a goddess/god or goddesses/gods (you are a hidden paganist/Paganism: an approximately 12,000-year-old belief system)

Religious Evolution?

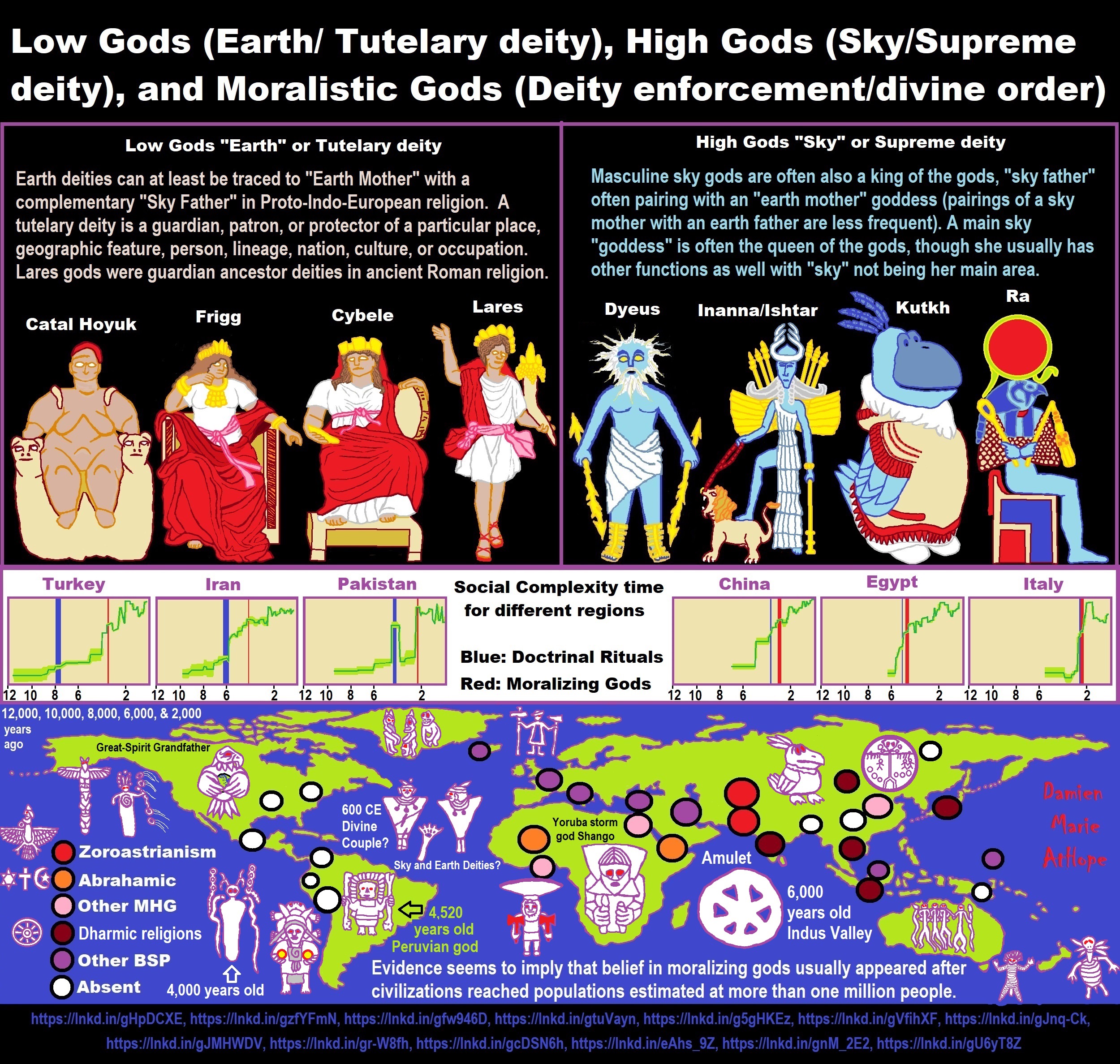

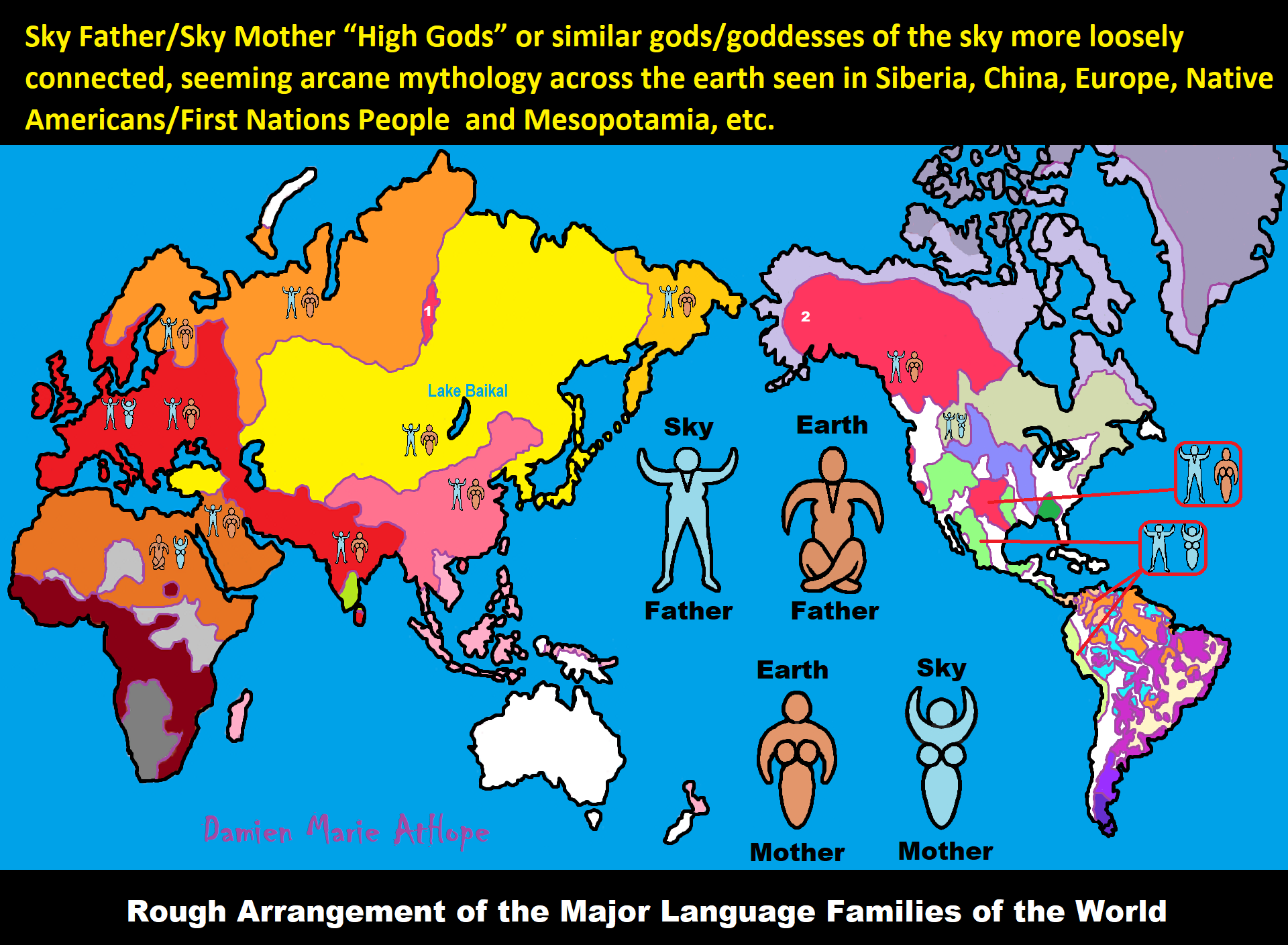

In my thinking on the evolution of religion, it seems a belief in animistic spirits” (a belief system dating back at least 100,000 years ago on the continent of Africa), that in totemism (dating back at least 50,000 years ago on the continent of Europe) with newly perceived needs where given artistic expression of animistic spirits both animal or human “seemingly focused on female humans to begin with and only much much later is there what look like could be added male focus”, but even this evolved into a believed stronger communion with more connections in shamanism (a belief system dating back at least 30,000 years ago on the continent of Aisa) with newly perceived needs, then this also evolved into Paganism (a belief system dating back at least 13,000 years ago on the continent of eastern Europe/western Asia turkey mainly but eastern Mediterranean lavant as well to some extent or another) with newly perceived needs where you see the emergence of animal gods and female goddesses around into more formalized animal gods and female goddesses and only after 7,000 to 6,000 do male gods emerge one showing its link in the evolution of religion and the other more on it as a historical religion.

Ps. Progressed organized religion starts approximately 5,000-year-old belief system)

Promoting Religion as Real is Harmful?

Sometimes, when you look at things, things that seem hidden at first, only come clearer into view later upon reselection or additional information. So, in one’s earnest search for truth one’s support is expressed not as a one-time event and more akin to a life’s journey to know what is true. I am very anti-religious, opposing anything even like religion, including atheist church. but that’s just me. Others have the right to do atheism their way. I am Not just an Atheist, I am a proud antireligionist. I can sum up what I do not like about religion in one idea; as a group, religions are “Conspiracy Theories of Reality.”

These reality conspiracies are usually filled with Pseudo-science and Pseudo-history, often along with Pseudo-morality and other harmful aspects and not just ancient mythology to be marveled or laughed at. I regard all this as ridiculous. Promoting Religion as Real is Mentally Harmful to a Flourishing Humanity To me, promoting religion as real is too often promote a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from who they are shaming them for being human. In addition, religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from real history, real science, or real morality to pseudohistory, pseudoscience, and pseudomorality.

Moreover, religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from rational thought, critical thinking, or logic. Likewise, religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from justice, universal ethics, equality, and liberty. Yes, religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from loved ones, and religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from humanity. Therefore, to me, promoting religion as real is too often promote a toxic mental substance that should be rejected as not only false but harmful as well even if you believe it has some redeeming quality. To me, promoting religion as real is mentally harmful to a flourishing humanity. Religion may have once seemed great when all you had or needed was to believe. Science now seems great when we have facts and need to actually know.

A Rational Mind Values Humanity and Rejects Religion and Gods

A truly rational mind sees the need for humanity, as they too live in the world and see themselves as they actually are an alone body in the world seeking comfort and safety. Thus, see the value of everyone around then as they too are the same and therefore rationally as well a humanistically we should work for this humanity we are part of and can either dwell in or help its flourishing as we are all in the hands of each other. You are Free to think as you like but REALITY is unchanged. While you personally may react, or think differently about our shared reality (the natural world devoid of magic anything), We can play with how we use it but there is still only one communal reality (a natural non-supernatural one), which we all share like it or not and you can’t justifiably claim there is a different reality. This is valid as the only one of warrant is the non-mystical natural world around us all, existing in or caused by nature; not made or caused by superstitions like gods or other monsters to many people sill fear irrationally.

Do beliefs need justification?

Yes, it all requires a justification, and if you think otherwise you should explain why but then you are still trying to employ a justification to challenge justification. So, I still say yes it all needs a justification and I know everything is reducible to feeling the substation of existence. I feel my body and thus I can start my justificationism standard right there and then build all logic inferences from that justified point and I don’t know a more core presupposition to start from. A presupposition is a core thinking stream like how a tree of beliefs always has a set of assumed sets of presuppositions or a presupposition is relatively a thing/thinking assumed beforehand at the beginning of a line of thinking point, belief projection, argument, or course of action. And that, as well as everything, needs justification to be concluded as reasonable. Sure, you can believe all kinds of things with no justification at all but we can’t claim them as true, nor wish others to actually agree unless something is somehow and or in some way justified. When is something true that has no justification? If you still think so then offer an example, you know a justification. Sure, there can be many things that may be true but actually receiving rational agreement that they are intact true needs justification.

Without Nonsense, Religion Dies

I am against ALL Pseudoscience, Pseudohistory, and Pseudomorality. And all of these should openly be debunked, when and where possible. Of course, not forgetting how they are all highly represented in religion. All three are often found in religion to the point that if they were removed, their loss would likely end religion as we know it. I don’t have to respect ideas. People get confused ideas are not alive nor do they have beingness, Ideas don’t have rights nor the right to even exist only people have such a right. Ideas don’t have dignity nor can they feel violation only people if you attack them personally. Ideas don’t deserve any special anything they have no feelings and cannot be shamed they are open to the most brutal merciless attack and challenge without any protection and deserve none nor will I give them any if they are found wanting in evidence or reason. I will never respect Ideas if they are devoid of merit I only respect people.

Rain Serpents in Northern Australia and Southern Africa: a Common Ancestry? (proof)

Introduction

“In the late 1980s, geneticists announced that we evolved in Africa close to 200,000 years ago (200 ka), with a tentatively inferred initial migration between ~50 ka and ~100 ka. Paleolithic archaeologists immediately recognized that these findings made the long-established consensus that there was no compelling evidence for symbolic behaviors pre-dating ~40 ka (treated as a cognitive Rubicon) look decidedly anomalous. How could the fundamental trait distinguishing our species from earlier hominins postdate our dispersal? New research in Africa was initiated, as a result of which it is now widely accepted that symbolic culture was in place by ~100 ka.” ref

“The evidence includes habitual use of red ochre (closely associated with the dispersal), geometric engravings on ochre, beads (some with ochre residues), and (in the Levant) male burials with parts of game animals (indirectly associated with ochre). In southern Africa, the most intensively studied portion of the continent for the relevant period, it seems that ubiquitous use of red ochre can be inferred from ~170 ka, suggesting that symbolic culture correlates with our speciation. The use of red and glittery pigments in southern Africa from ~500 ka has been interpreted as the earliest evidence for collective ritual. At first sight, a speculative case might be made for a gradual evolution of collective ritual, out of which was forged a template of symbolic culture, at least three elements of which might be inferred by the time of dispersal beyond Africa – belief in ‘other’ worlds (associating the dead with game animals), cosmetic ‘skin-change’, and some form of ‘blood’ symbolism (see Knight and Lewis, this volume; Power, this volume). For reasons concerning the history of the discipline, social anthropologists have been slow to respond to the possible implications of our recent dispersal out of Africa.” ref

“Among the first to do so was Alan Barnard, who made a case for why Bushmen, rather than Australian Aborigines, are more appropriate for thinking about early human society, identifying six areas of difference where parsimony suggested this was the case – essentially that the Australian world-view was too ‘structurally evolved’. Within the field of belief, he considered that Australian Aborigines differed from ‘all other modern hunter-gatherers … (in) their belief in the Rainbow Serpent and the Dreaming’. He went on to note: ‘Although Rainbow Serpent-type creatures feature too in African mythology and rock art, they do not carry this symbolic weight; and that there is no African equivalent to the Dreaming’. The Dreaming is a parallel but ontologically prior world where the distinction between animals and humans is not fixed; other Bushmen specialists do see an equivalence, so Barnard’s assertion is debatable. Regarding Rainbow Serpent-type creatures, a more interesting issue than their relative symbolic weight in the two regions is the implicit question about the nature of the identity, and whether this should be attributed to trivial or non-trivial factors. Rainbow Serpent-type creatures are representative of the wider set of dragons, serpents, and rain-animals widely distributed in world mythology.” ref

“The set has primarily been based on a number of recurrent themes, prominent among which have been control of water, an intimate relationship to women, transformative power (including ‘death’, healing and ‘resurrection’), movement between ‘worlds’, and an antithesis to cooking and exogamous sex/marriage. They have fascinated European commentators since anthropology’s emergence as a distinct discipline. Initially, building upon an earlier, theological research agenda (Deane 1833), attention largely focused on ‘serpent worship’ in state societies. Even as the scope of inquiry broadened, it remained a search for fixed meanings. A notable exception was Vladimir Propp’s formalist approach, which recognized that all magical tales were uniquely constrained; he concluded that Eurasian fairytales could be treated as variants of one tale only, in which a dragon kidnaps a princess. Only with the influence of structuralism in the 1970s did researchers begin to focus on the underlying logic informing such supernatural beings. Radcliffe-Brown (1926) first noted possible parallels between Australian Rainbow Snakes and Bushman belief in snakes protecting waterholes, but without comment or citing any African literature.” ref

“The issue remained dormant until a preliminary treatment by Knight, drawing on rock-art studies and limited ethnographic material (predominantly from Khoe-speaking, historically pastoralist cultures) to compare the logic of belief with that he had identified in greater detail in Australia. In the most recent and exhaustive evaluation of Khoisan Rainbow Snake-type creatures, Sullivan and Low end by quoting Knight’s conclusion about Australian Rainbow Snake myths. To give the full quote, ‘what all these myths are referring to is not really a “thing” at all, but a cyclical logic which lies beyond and behind all the many concrete images – moon, snakes, tidal forces, waterholes, rainbows, mothers and so on – used in partial attempts to describe it’. Sullivan and Low’s own conclusion is that the Khoisan material ‘affirms in all its detail and particularity the broad contours of this “logic”. So what is this cyclical logic?” ref

“Knight had proposed a model of the origin of symbolic culture in which evolving women, faced with the costs of giving birth to and rearing larger-brained, more dependent offspring, needed to secure unprecedented levels of male investment (see Finnegan, this volume). To achieve this, they had, through collective ritual action, made themselves periodically sexually unavailable, declaring themselves ‘sacred’ and ‘taboo’ until men surrendered the product of a collective hunt. This was achieved by exploiting the signaling potential of menstruation. The evolutionary logic was more precisely specified by Knight, Power, and Watts, identifying menstruation as a valuable cue to males of imminent fertility. The posited strategy was that the most reproductively burdened females prevented would-be philanderer males from targeting an imminently fertile menstruant at the expense of other females, forming a ‘picket-line’ around her, sharing the blood around or using blood substitutes to scramble the information, thereby using cultural or cosmetic means to ‘synchronize’ bleeding, while at the same time advertising her attractive qualities. These female cosmetic coalitions inverted standard fertility signaling, ritually pantomiming ‘Wrong species, wrong sex, wrong time’.” ref

“The economic logic was the imposition of a rule of distribution dissociating people from their own produce, whether the product of hunting labor (a hunter’s ‘own kill rule’), or reproductive labor (incest prohibitions). Synchronizing ‘strike’ action across communities required an environmental cue of appropriate periodicity. Collective spear-hunting of medium to large game – liable to take several days and nights – needed to optimize available natural light, making the days and nights immediately before full moon ideal, implying that the ‘strike’ began at dark moon. The cyclical logic is the movement from blood-defined kinship solidarity to ‘honeymoon’, from temporary death (to marital relations) to resurrection, from ritual power ‘on’ to ritual power ‘off’. If lack of meat motivates the sex strike, it should also be a cooking strike, and if women’s blood marks them as periodically taboo, then killed and bloody game animals should also be taboo, until they are surrendered and the blood removed through cooking. Treating metaphor as the underlying principle of symbolic culture (Knight and Lewis, this volume), the fundamental metaphor is that women’s blood be equated with that of game animals.” ref

“What kind of phenomena might be suitable for elaborating the logic informing this metaphor? Anything that could represent periodicity, movement between worlds, association with wetness, ambiguous sex, minimal morphological differentiation, skin-change, and transformative powers (e.g. death-dealing) would be appropriate. Rainbows meet some of these requirements, and for a tropically evolved species, pythons would also be particularly good to think with (cf. Lévi-Strauss 1966).In this chapter, I compare aspects of Yurlunggur (the Yolngu Rainbow Snake of Arnhem Land, northern Australia) and !Khwa (the Rain Bull of the /Xam Bushmen in the Upper Karoo, South Africa). Following Knight, I focus on the relationship of these supernatural beings to menstrual blood, hoping to show how this throws their logic and structural role into sharpest relief.” ref

Background

“The study of Rainbow Snakes in Australia can be divided into two main phases: an initial period identifying and describing the phenomena in the late 1920s; and structuralist influenced work in the 1970s and early 1980s. Some Aboriginal cultures permitted relating the mythological entity to ritual practice. The second phase recognized the Rainbow Snake as perhaps the ultimate symbolic representation of paradox and transformation. The Yolngu live in northeast Arnhem Land, in the Australian tropics.” ref

“Seasonal flooding and a difficult landscape made the area unattractive to Europeans, allowing the Yolngu to keep their culture relatively intact well into the twentieth century. The myth of how, as a result of the actions of the two Wawilak Sisters, Yurlunggur created the present world is the most extensively recorded and thoroughly analyzed of Australian Rainbow Snake myths, allowing me to present an abridged version here. A history of research on Khoisan Rainbow Serpent-type creatures in southern Africa is beyond the scope of this paper. Suffice it to say that they have been indigenously described as ‘Watersnakes’, ‘Great Snakes’, eland-bulls, ‘Rain Bulls’, and indeterminate large quadrupeds.” ref

“Such creatures are considered to lie at the heart of ‘a dynamic assemblage of extant cognitive associations between snakes, rain, environmental/landscape dynamics, water, fertility, blood, fat, transformation, dance and healing’. The /Xam were Bushmen of the Upper Karoo, the interior, semi-arid region south of the Orange River. Because they were killed or brutally assimilated into the colonial frontier economy of the late eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth centuries, virtually everything we know about them is through the remarkable linguistic endeavors of Wilhelm Bleek and his sister-in-law Lucy Lloyd in the 1870s, and the equally remarkable co-operation of a succession of /Xam prisoners released into their custody, several of whom stayed well beyond their prison terms. This vast corpus of material included information on ritual and an extensive body of mythology.” ref

“A history of research on Khoisan Rainbow Serpent-type creatures in southern Africa is beyond the scope of this paper. Suffice it to say that they have been indigenously described as ‘Watersnakes’, ‘Great Snakes’, eland-bulls, ‘Rain Bulls’, and indeterminate large quadrupeds. Such creatures are considered to lie at the heart of ‘a dynamic assemblage of extant cognitive associations between snakes, rain, environmental/landscape dynamics, water, fertility, blood, fat, transformation, dance, and healing. The /Xam were Bushmen of the Upper Karoo, the interior, semi-arid region south of the Orange River. Because they were killed or brutally assimilated into the colonial frontier economy of the late eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth centuries, virtually everything we know about them is through the remarkable linguistic endeavors of Wilhelm Bleek and his sister-in-law Lucy Lloyd in the 1870s, and the equally remarkable co-operation of a succession of /Xam prisoners released into their custody, several of whom stayed well beyond their prison terms.” ref