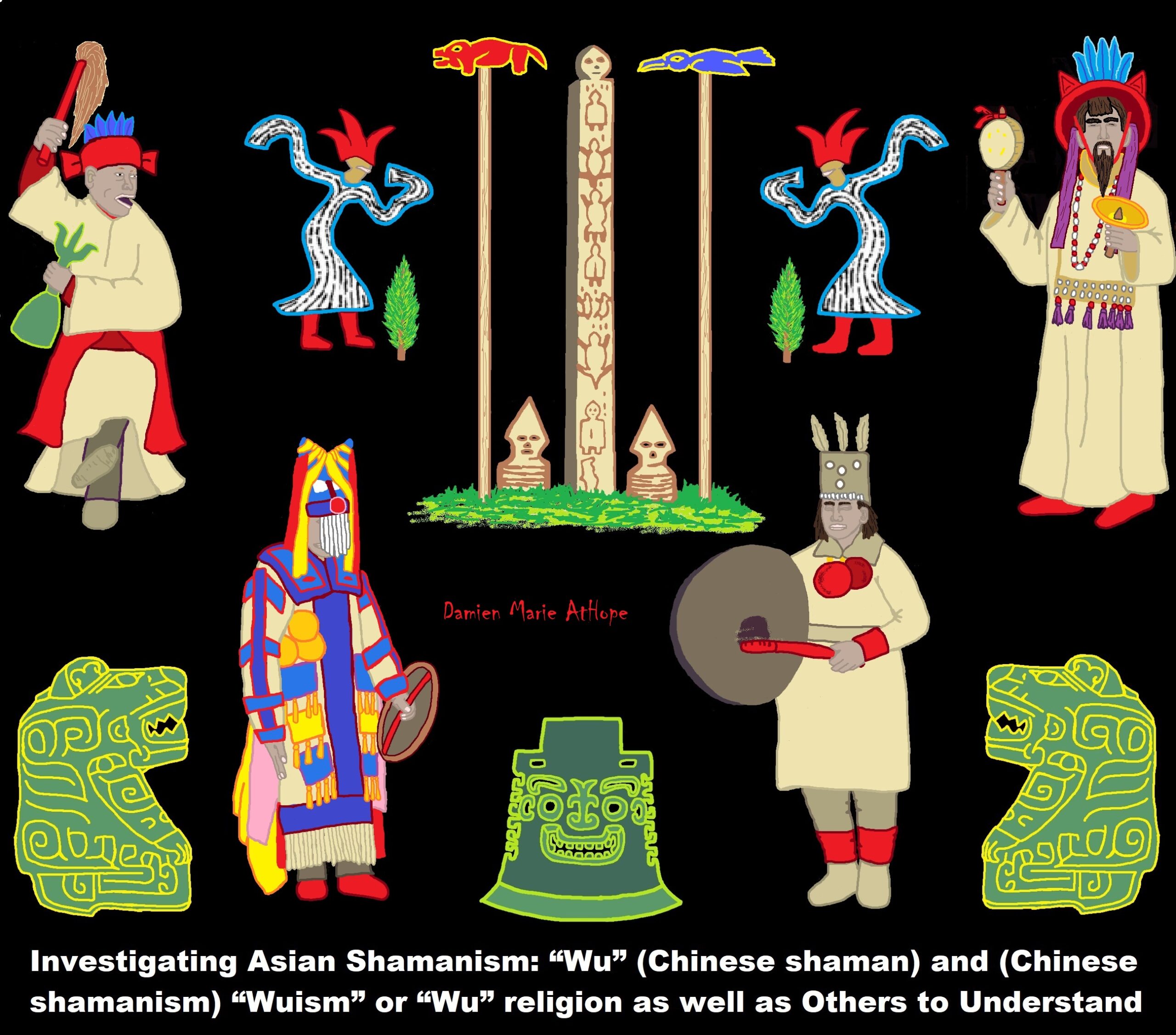

Chinese Wu, Ritualists, and Shamans: An Ethnological Analysis

“Abstract: The relationship of wu (巫) to shamanism is problematic, with virtually all mentions of historical and contemporary Chinese wu ritualists translated into English as shaman. Ethnological research is presented to illustrate cross-cultural patterns of shamans and other ritualists, providing an etic framework for empirical assessments of resemblances of Chinese ritualists to shamans. This etic framework is further validated with assessments of the relationship of the features with biogenetic bases of ritual, altered states of consciousness, innate intelligences and endogenous healing processes. Key characteristics of the various types of wu and other Chinese ritualists are reviewed and compared with ethnological models of the patterns of ritualists found cross-culturally to illustrate their similarities and contrasts. These comparisons illustrate the resemblances of pre-historic and commoner wu to shamans but additionally illustrate the resemblances of most types of wu to other ritualist types, not shamans. Across Chinese history, wu underwent transformative changes into different types of ritualists, including priests, healers, mediums and sorcerers/witches. A review of contemporary reports on alleged shamans in China also illustrates that only some correspond to the characteristics of shamans found in cross-cultural research and foraging societies. The similarities of most types of wu ritualists to other types of ritualists found cross-culturally illustrate the greater accuracy of translating wu as “ritualist” or “religious ritualist.” ref

The Shamanic Origins Of Medicine In Ancient China

“The link between medicine and shamanism in ancient China can be found in the etymology of the words used to describe the practices, as well as other ancient texts.” ref

“Wu (shaman): female shamans in ancient China, Chinese shamanism, is alternatively called “Wuism” ref

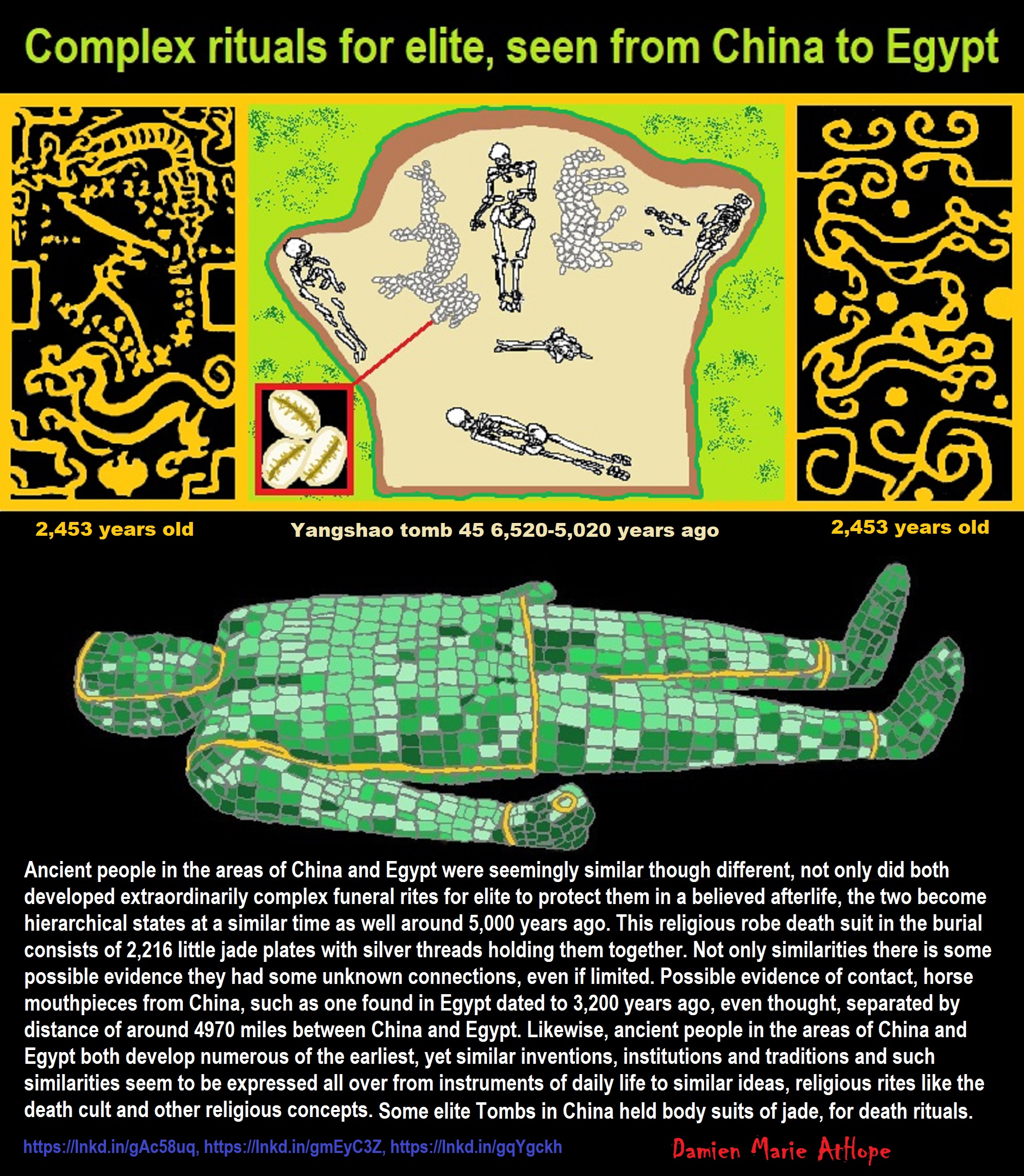

“Shamanism is China’s oldest indigenous belief system. It is still widely practiced in villages and even cities, especially during times of ritual transition and crisis. Shaman rituals are performed on mountaintops, at traditional shrines and in village homes. Ancient shaman in China likely used jade ornaments with divine markings to command mystical forces and communicate with gods and ancestors. Ancient Chinese believed that there ancestors originated with God and communicated through supernatural beings and symbols, whose images were placed on jade ornaments.” ref

Wu (shaman)

“Wu (Chinese: 巫; pinyin: wū; Wade–Giles: wu) is a Chinese term translating to “shaman” or “sorcerer”, originally the practitioners of Chinese shamanism or “Wuism” (巫教 wū jiào). The glyph ancestral to modern 巫 is first recorded in bronze script, where it could refer to shamans or sorcerers of either sex. Modern Mandarin wu (Cantonese mouh) continues a Middle Chinese mju or mjo. The Old Chinese reconstruction is uncertain, given as *mywo or as *myag, the presence of a final velar -g or -ɣ in Old Chinese being uncertain.” ref

“By the late Zhou Dynasty (4th to 3rd centuries BCE), wu referred mostly to female shamans or “sorceresses”, while male sorcerers were named xi 覡 “male shaman; sorcerer”, first attested in the Guoyu or Discourses of the States (4th century BCE). Other sex-differentiated shaman names include nanwu 男巫 for “male shaman; sorcerer; wizard”; and nüwu 女巫, wunü 巫女, wupo 巫婆, and wuyu 巫嫗 for “female shaman; sorceress; witch”. Wu is used in compounds like wugu 巫蠱 “sorcery; cast harmful spells”, wushen 巫神 or shenwu 神巫 (with shen “spirit; god”) “wizard; sorcerer”, and wuxian 巫仙 (with xian “immortal; alchemist”) “immortal shaman.” ref

“The word tongji 童乩 (lit. “youth diviner”) “shaman; spirit-medium” is a near-synonym of wu. Chinese uses phonetic transliteration to distinguish native wu from “Siberian shaman“: saman 薩滿 or saman 薩蠻. “Shaman” is occasionally written with Chinese Buddhist transcriptions of Shramana “wandering monk; ascetic”: shamen 沙門, sangmen 桑門, or sangmen 喪門. Joseph Needham suggests “shaman” was transliterated xianmen 羨門 in the name of Zou Yan‘s disciple Xianmen Gao 羨門高 (or Zigao 子高). He quotes the Shiji that Emperor Qin Shi Huang (r. 221–210 BCE), “wandered about on the shore of the eastern sea, and offered sacrifices to the famous mountains and the great rivers and the eight Spirits; and searched for xian “immortals”, [xianmen], and the like.” Needham compares two later Chinese terms for “shaman”: shanman 珊蛮, which described the Jurchen leader Wanyan Xiyin, and sizhu 司祝, which was used for imperial Manchu shamans during the Qing Dynasty.” ref

“Shaman is the common English translation of Chinese wu, but some scholars maintain that the Siberian shaman and Chinese wu were historically and culturally different shamanic traditions. Arthur Waley defines wu as “spirit-intermediary” and says, “Indeed the functions of the Chinese wu were so like those of Siberian and Tunguz shamans that it is convenient (as has indeed been done by Far Eastern and European writers) to use shaman as a translation of wu. In contrast, Schiffeler describes the “untranslatableness” of wu, and prefers using the romanization “wu instead of its contemporary English counterparts, “witches,” “warlocks,” or “shamans”,” which have misleading connotations.” ref

“Taking wu to mean “female shaman”, Edward H. Schafer translates it as “shamaness” and “shamanka”. The transliteration-translation “wu shaman” or “wu-shaman” implies “Chinese” specifically and “shamanism” generally. Wu, concludes von Falkenhausen, “may be rendered as “shaman” or, perhaps, less controversially as “spirit medium”. Paper criticizes “the majority of scholars” who use one word shaman to translate many Chinese terms (wu 巫, xi 覡, yi 毉, xian 仙, and zhu 祝), and writes, “The general tendency to refer to all ecstatic religious functionaries as shamans blurs functional differences.” ref

“The character 巫 wu besides the meanings of “spirit medium, shaman, witch doctor” (etc.) also has served as a toponym: Wushan 巫山 (near Chongqing in Sichuan Province), Wuxi 巫溪 “Wu Stream”, Wuxia 巫峽 “Wu Gorge”. Wu is also a surname (in antiquity, the name of legendary Wu Xian 巫咸). Wuma 巫馬 (lit. “shaman horse”) is both a Chinese compound surname (for example, the Confucian disciple Wuma Shi/Qi 巫馬施/期) and a name for “horse shaman; equine veterinarian” (for example, the Zhouli official). The contemporary Chinese character 巫 for wu combines the graphic radicals gong 工 “work” and ren 人 “person” doubled (cf. cong 从). This 巫 character developed from Seal script characters that depicted dancing shamans, which descend from Bronzeware script and Oracle bone script characters that resembled a cross potent.” ref

“The first Chinese dictionary of characters, the (121 CE) Shuowen Jiezi defines wu as zhu 祝 “sacrifice; prayer master; invoker; priest” (“祝也 女能以舞降神者也 象从工 两人舞形”) and analyzes the Seal graph, “An Invoker. A woman who can serve the Invisible, and by posturing bring down the spirits. Depicts a person with two sleeves posturing.” This Seal graph for wu is interpreted as showing “the 工 work of two dancing figures set to each other – a shamanistic dance” or “two human figures facing some central object (possibly a pole, or in a tent-like enclosure?).” ref

“This dictionary also includes a variant Great Seal script (called a guwen “ancient script”) that elaborates wu 巫. Hopkins analyzes this guwen graph as gong 廾 “two hands held upward” at the bottom (like shi 筮’s Seal graph) and two “mouths” with the “sleeves” on the sides; or “jade” because the Shuowen defines ling 靈 “spiritual; divine” as synonymous with wu and depicting 巫以玉事神, “an inspired shaman serving the Spirits with jade.” ref

“Schafer compares the Shang Dynasty oracle graphs for wu and nong 弄 “play with; cause” (written with 玉 “jade” over 廾 “two hands”) that shows “hands (of a shaman?) elevating a piece of jade (the rain-compelling mineral) inside an enclosure, possibly a tent. The Seal and modern form 巫 may well derive from this original, the hands becoming two figures, a convergence towards the dancer-type graph.” ref

“Tu Baikui 塗白奎 suggests that the wu oracle character “was composed of two pieces of jade and originally designated a tool of divination.” Citing Li Xiaoding 李孝定 that gong 工 originally pictured a “carpenter’s square”, Allan argues that oracle inscriptions used wu 巫 interchangeably with fang 方 “square; side; place” for sacrifices to the sifang 四方 “four directions.” ref

“This 巫 component is semantically significant in several characters:

- wu誣 (with the “speech radical” 言) “deceive; slander; falsely accuse”

- shi筮 (with the “bamboo radical” 竹) “Achillea millefolium (used for divination)”

- xi覡 (with the “vision radical” 見) “male shaman; male sorcerer”

- ling靈 (with the “cloud radical” 雨 and three 口 “mouths” or “raindrops”) “spirit; divine; clever”

- yi毉 “doctor”, which is an old “shaman” variant character for yi 醫 (with the “wine radical” 酉)” ref

“A wide range of hypotheses for the etymology of wū “spirit medium; shaman” has been proposed. Laufer proposed a relation between Mongolian bügä “shaman”, Turkish bögü “shaman”, “Chinese bu, wu (shaman), buk, puk (to divine), and Tibetan aba (pronounced ba, sorcerer)”. Coblin puts forward a Sino-Tibetan root *mjaɣ “magician; sorcerer” for Chinese wū < mju < *mjag 巫 “magician; shaman” and Written Tibetan ‘ba’-po “sorcerer” and ‘ba’-mo “sorcereress” (of the Bön religion).” ref

“Schuessler notes Chinese xian < sjän < *sen 仙 “transcendent; immortal; alchemist” was probably borrowed as Written Tibetan gšen “shaman” and Thai [mɔɔ] < Proto-Tai *hmɔ “doctor; sorcerer”. In addition, the Mon–Khmer and Proto-Western-Austronesian *səmaŋ “shaman” may also be connected with wū. Schuessler lists four proposed etymologies: Firstly, wū could be the same word as wū 誣 “to deceive”. Schuessler notes a written Tibetan semantic parallel between “magical power” and “deceive”: sprul-ba “to juggle, make phantoms; miraculous power” cognate with [pʰrul] “magical deception.” ref

“Secondly, wu could be cognate with wǔ 舞 “to dance”. Based on analysis of ancient characters, Hopkins proposed that wū 巫 “shaman”, wú 無 “not have; without”, and wǔ 舞 “dance”, “can all be traced back to one primitive figure of a man displaying by the gestures of his arms and legs the thaumaturgic powers of his inspired personality”. Many Western Han Dynasty tombs contained jade plaques or pottery images showing “long-sleeved dancers” performing at funerals, whom Erickson identifies as shamans, citing the Shuowen jiezi that early wǔ characters depicted a dancer’s sleeves.” ref

“Thirdly, wū could also be cognate with mǔ 母 “mother” since wū, as opposed to xí 覡, were typically female. Edward Schafer associates wū shamanism with fertility rituals. Jensen cites the Japanese sinologist Shirakawa Shizuka 白川静’s hypothesis that the mother of Confucius was a wū. Fourthly, wū could be a loanword from Iranian *maguš “magus; magician” (cf. Old Persian maguš, Avestan mogu), meaning an “able one; specialist in ritual”. Mair provides archaeological and linguistic evidence that Chinese wū < *myag 巫 “shaman; witch, wizard; magician” was a loanword from Old Persian *maguš “magician; magus“. Mair connects the bronze script character for wū 巫 with the “cross potent” symbol ☩ found in Neolithic West Asia, suggesting the loan of both the symbol and the word.” ref

Early records of wu: Chinese shamanism

“The oldest written records of wu are Shang Dynasty oracle inscriptions and Zhou Dynasty classical texts. Boileau notes the disparity of these sources. Concerning the historical origin of the wu, we may ask: were they a remnant of an earlier stage of the development of archaic Chinese civilization? The present state of the documentation does not allow such a conclusion for two reasons: first, the most abundant data about the wu are to be found in Eastern Zhou texts; and, second, these texts have little in common with the data originating directly from the Shang civilization; possible ancestors of the Eastern Zhou wu are the cripples and the females burned in sacrifice to bring about rain. They are mentioned in the oracular inscriptions but there is no mention of the Shang character wu. Moreover, because of the scarcity of information, many of the activities of the Zhou wu cannot be traced back to the Shang period. Consequently, trying to correlate Zhou data with Neolithic cultures appears very difficult.” ref

Wu in Shang oracular inscriptions

“Shima lists 58 occurrences of the character wu in concordance of oracle inscriptions: 32 in repeated compounds (most commonly 巫帝 “wu spirit/sacrifice” and 氐巫 “bring the wu) and 26 in miscellaneous contexts. Boileau differentiates four meanings of these oracular wu:

- “a spirit, wuof the north or east, to which sacrifices are offered”

- “a sacrifice, possibly linked to controlling the wind or meteorology”

- “an equivalent for shi筮, a form of divination using achilea”

- “a living human being, possibly the name of a person, tribe, place, or territory” ref

“Based on this ancient but limited Shang-era oracular record, it is unclear how or whether the Wu spirit, sacrifice, person, and place were related. The inscriptions about this living wu, which is later identified as “shaman”, reveal six characteristics:

- whether the wuis a man or a woman is not known;

- it could be either the name for a function or the name of a people (or an individual) coming from a definite territory or nation;

- the wu seems to have been in charge of some divinations, (in one instance, divination is linked to a sacrifice of appeasement);

- the wu is seen as offering a sacrifice of appeasement but the inscription and the fact that this kind of sacrifice was offered by other persons (the king included) suggests that the wuwas not the person of choice to conduct all the sacrifices of appeasement;

- there is only one inscription where a direct link between the king and the wu Nevertheless, the nature of the link is not known, because the status of the wudoes not appear clearly;

- he follows (being brought, presumably, to Shang territory or court) the orders of other people; he is perhaps offered to the Shang as a tribute.” ref

Wu in Zhou received texts

“Chinese wu 巫 “shaman” occurs over 300 times in the Chinese classics, which generally date from the late Zhou and early Han periods (6th-1st centuries BCE). The following examples are categorized by the common specializations of wu-shamans: men and women possessed by spirits or gods, and consequently acting as seers and soothsayers, exorcists and physicians; invokers or conjurers bringing down gods at sacrifices, and performing other sacerdotal functions, occasionally indulging also in imprecation, and in sorcery with the help of spirits.” ref

“A single text can describe many roles for wu-shamans. For instance, the Guoyu idealizes their origins in a Golden Age. It contains a story about King Zhao of Chu (r. 515-489 BCE) reading in the Shujing that the sage ruler Shun “commissioned Chong and Li to cut the communication between heaven and earth”. He asks his minister to explain and is told: Anciently, men and spirits did not intermingle. At that time there were certain persons who were so perspicacious, single-minded, and reverential that their understanding enabled them to make meaningful collation of what lies above and below, and their insight to illumine what is distant and profound. Therefore the spirits would descend upon them. The possessors of such powers were, if men, called xi (shamans), and, if women, wu (shamanesses). It is they who supervised the positions of the spirits at the ceremonies, sacrificed to them, and otherwise handled religious matters. As a consequence, the spheres of the divine and the profane were kept distinct. The spirits sent down blessings on the people, and accepted from them their offerings. There were no natural calamities.” ref

“In the degenerate time of [Shaohao] (traditionally put at the twenty-sixth century BCE), however, the Nine Li threw virtue into disorder. Men and spirits became intermingled, with each household indiscriminately performing for itself the religious observances which had hitherto been conducted by the shamans. As a consequence, men lost their reverence for the spirits, the spirits violated the rules of men, and natural calamities arose. Hence the successor of [Shaohao], [Zhuanxu] …, charged [Chong], Governor of the South, to handle the affairs of heaven in order to determine the proper place of the spirits, and Li, Governor of Fire, to handle the affairs of Earth, in order to determine the proper place of men. And such is what is meant by cutting the communication between Heaven and Earth.” ref

Wu-shamans as healers

“The belief that demonic possession caused disease and sickness is well documented in many cultures, including ancient China. The early practitioners of Chinese medicine historically changed from wu 巫 “spirit-mediums; shamans” who used divination, exorcism, and prayer to yi 毉 or 醫 “doctors; physicians” who used herbal medicine, moxibustion, and acupuncture. As mentioned above, wu 巫 “shaman” was depicted in the ancient 毉 variant character for yi 醫 “healer; doctor”. This archaic yi 毉, writes Carr, “ideographically depicted a shaman-doctor in the act of exorcistical healing with (矢 ‘arrows’ in) a 医 ‘quiver’, a 殳 ‘hand holding a lance’, and a wu 巫 ‘shaman’.” Unschuld believes this 毉 character depicts the type of wu practitioner described in the Liji.” ref

“Several times a year, and also during certain special occasions, such as the funeral of a prince, hordes of exorcists would race shrieking through the city streets, enter the courtyards and homes, thrusting their spears into the air, in an attempt to expel the evil creatures. Prisoners were dismembered outside all gates to the city, to serve both as a deterrent to the demons and as an indication of their fate should they be captured. Replacing the exorcistical 巫 “shaman” in 毉 with medicinal 酒 “wine” in yi 醫 “healer; doctor” signified, writes Schiffeler, “the practice of medicine was not any longer confined to the incantations of the wu, but that it had been taken over (from an official standpoint) by the “priest-physicians,” who administered elixirs or wines as treatments for their patients.” ref

“Wu and yi are compounded in the word wuyi 巫醫 “shaman-doctor; shamans and doctors”, translated “exorcising physician”, “sorcerer-physician”, or “physician-shaman”. Confucius quotes a “Southern Saying” that a good wuyi must have heng 恆 “constancy; ancient tradition; continuation; perseverance; regularity; proper name (e.g., Yijing Hexagram 32)”. The (ca. 5th century BCE) Lunyu “Confucian Analects” and the (ca. 1st century BCE) Liji “Record of Rites” give different versions of the Southern Saying.” ref

“First, the Lunyu quotes Confucius to mention the saying and refer to the Heng Hexagram: The Master said, The men of the south have a saying, Without stability a man will not even make a good shaman or witch-doctor. Well said! Of the maxim; if you do not stabilize an act of te 德, you will get evil by it (instead of good), the Master said, They (i.e. soothsayers) do not simply read the omens. Confucius refers to a Yijing line interpretation of the Heng “Duration” Hexagram: “Nine in the third place means: He who does not give duration to his character meets with disgrace.” In Waley’s earlier article about the Yijing, he translated “If you do not stabilize your “virtue,” Disgrace will overtake you”, and quoted the Lunyu.” ref

“The people of the south have a saying, ‘It takes heng to make even a soothsayer or medicine-man.’ It’s quite true. ‘If you do not stabilize your virtue, disgrace will overtake you’.” Confucius adds 不占而已矣, which has completely baffled his interpreters. Surely the meaning is ‘It is not enough merely to get an omen,’ one must also heng ‘stabilize it’. And if such a rule applies even to inferior arts like those of the diviner and medicine-man, Confucius asks, how much the more does it apply to the seeker after [de] in the moral sense? Surely he too must ‘make constant’ his initial striving! Second, the Liji quotes Confucius to elaborate upon the Southern Saying.” ref

“The Master said, ‘The people of the south have a saying that “A man without constancy cannot be a diviner either with the tortoise-shell or the stalks.” This was probably a saying handed down from antiquity. If such a man cannot know the tortoise-shell and stalks, how much less can he know other men? It is said in the Book of Poetry (II, v, ode 1, 3) “Our tortoise-shells are wearied out, And will not tell us anything about the plans.” The Charge to [Yue] says ([Shujing], IV, VIII, sect. 2, 5, 11), “Dignities should not be conferred on men of evil practices. (If they be), how can the people set themselves to correct their ways? If this be sought merely by sacrifices, it will be disrespectful (to the spirits). When affairs come to be troublesome, there ensues disorder; when the spirits are served so, difficulties ensue.” ‘It is said in the [Yijing], “When one does not continuously maintain his virtue, some will impute it to him as a disgrace; (in the position indicated in the Hexagram.) ‘When one does maintain his virtue continuously (in the other position indicated), this will be fortunate in a wife, but in a husband evil.” ref

“This Liji version makes five changes from the Lunyu. (1) It writes bushi 卜筮 “diviner” instead of wuyi 巫醫 “shaman-doctor”, compounding bu “divine by bone or shell, scapulimancy or plastromancy” and shi (also with “shaman”) “divine by milfoil stalks, cleromancy or sortilege”. (2) Instead of quoting Confucius to remark “well said!”; he describes the southern proverb as “probably a saying handed down from antiquity” and rhetorically questions the efficacy of divination. (3) The Liji correctly quotes the Shijing criticizing royal diviners: “Our tortoises are (satiated =) weary, they do not tell us the (proper) plans.” (4) It quotes the “Charge to Yue” 說命 (traditionally attributed to Shang king Wu Ding) differently from the fabricated Guwen “Old Texts” Shujing “Classic of History” chapter with this name.” ref

“Dignities may not be conferred on man of evil practices, but only on men of worth. Anxious thought about what will be good should precede your movements. Your movements also should have respect to the time for them. … Officiousness in sacrifices is called irreverence; ceremonies when burdensome lead to disorder. To serve the spirits in this way is difficult. (5) It cites an additional Yijing Hexagram 32 line that gender determines the auspiciousness of heng. “Six in the fifth place means: Giving duration to one’s character through perseverance. This is good fortune for a woman, misfortune for a man.” ref

“The mytho-geography Shanhaijing “Classic of Mountains and Seas” associates wu-shamans with medicinal herbs. East of the Openbright there are Shaman Robust, Shaman Pushaway, Shaman Sunny, Shaman Shoe, Shaman Every, and Shaman Aide. They are all on each side of the corpse of Notch Flaw and they hold the neverdie drug to ward off decay. There is Mount Divinepower. This is where Shaman Whole, Shaman Reach, Shaman Share, Shaman Robust, Shaman Motherinlaw, Shaman Real, Shaman Rite, Shaman Pushaway, ShamanTakeleave, and Shaman Birdnet ascend to the sky and come down from Mount Divinepower. This is where the hundred drugs are to be found.” ref

“Shaman Whole” translates Wu Xian 巫咸 below. Boileau contrasts Siberian and Chinese shamanic medicines. Concerning healing, a comparison of the wu and the Siberian shaman shows a big difference: in Siberia, the shaman is also in charge of cures and healing, but he does this by identifying the spirit responsible for the disease and negotiates the proper way to appease him (or her), for example by offering a sacrifice or food on a regular basis. In archaic China, this role is performed through sacrifice: exorcism by the wu does not seem to result in a sacrifice but is aimed purely and simply at expelling the evil spirit.” ref

Wu-shamans as rainmakers

“Wu anciently served as intermediaries with nature spirits believed to control rainfall and flooding. During a drought, wu-shamans would perform the yu 雩 “sacrificial rain dance ceremony”. If that failed, both wu and wang 尪 “cripple; lame person; emaciated person” engaged in “ritual exposure” rainmaking techniques based upon homeopathic or sympathetic magic. As Unschuld explains, “Shamans had to carry out an exhausting dance within a ring of fire until, sweating profusely, the falling drops of perspirations produced the desired rain.” These wu and wang procedures were called pu 曝/暴 “expose to open air/sun”, fen 焚 “burn; set on fire”, and pulu 暴露 “reveal; lay bare; expose to open air/sun.” ref

“For the year 639 BCE, the Chunqiu records, “In summer, there was a great drought” in Lu, and the Zuozhuan notes a discussion about fen wu wang 焚巫尪: The duke (Xi) wanted to burn a wu and a cripple at the stake. Zang Wenzhong 臧文仲 said: this is no preparation for the drought. Repair the city walls, limit your food, be economic in your consumption, be parsimonious and advise (people) to share (the food), this is what must be done. What use would be wu and cripple? If Heaven wanted to have them killed, why were they born at all? If they (the cripple and the wu) could produce drought, burning them would augment very much (the disaster). The duke followed this advice, and subsequently “scarcity was not very great.” ref

“The Liji uses the words puwang 暴尪 and puwu 暴巫 to describe a similar rainmaking ritual during the reign (407-375 BCE) of Duke Mu 穆公 of Lu. There was a drought during the year. Duke Mu called on Xianzi and asked him about the reason for this. He said: ‘Heaven has not (given us) rain in a long time. I want to expose to the sun a cripple and what about that?’ (Xianzi) said: ‘Heaven has not (given us) rain in a long time but to expose to the sun the crippled son of somebody, that would be cruel. No, this cannot be allowed.’ (the duke said): ‘Well, then I want to expose to the sun a wu and what about that?’ (Xianzi) answered: ‘Heaven has not (given us) rain in a long time but to put one’s hope on an ignorant woman and offer her to pray (for rain), no, this is too far (from reason).” ref

“Commentators interpret the wu as a female shaman and the wang as a male cripple. De Groot connects the Zuozhuan and Liji stories about ritually burning wu. These two narratives evidently are different readings of one, and may both be inventions; nevertheless they have their value as sketches of ancient idea and custom. Those ‘infirm or unsound’ wang were non-descript individuals, evidently placed somewhat on a line with the wu; perhaps they were queer hags or beldams, deformed beings, idiotic or crazy, or nervously affected to a very high degree, whose strange demeanour was ascribed to possession.” ref

Wu-shamans as oneiromancers

“Oneiromancy or dream interpretation was one type of divination performed by wu 巫. The Zuozhuan records two stories about wu interpreting the guilty dreams of murderers. First, in 581 BCE the lord of Jin, who had slain two officers from the Zhao (趙) family, had a nightmare about their ancestral spirit, and called upon an unnamed wu “shaman” from Sangtian 桑田 and a yi “doctor” named Huan 緩 from Qin. The marquis of [Jin] saw in a dream a great demon with disheveled hair reaching to the ground, which beat its breast, and leaped up, saying: “You have slain my descendants unrighteously, and I have presented my request to the High God in consequence.” It then broke the great gate (of the palace), advanced to the gate of the State chamber, and entered. The duke was afraid and went into a side-chamber, the door of which it also broke. The duke then awoke, and called the witch of [Sangtian], who told him everything which he had dreamt. “What will be the issue?” asked the duke. “You will not taste the new wheat,” she replied.” ref

“After this, the duke became very ill, and asked the services of a physician from [Qin], the earl of which sent the physician [Huan] to do what he could for him. Before he came, the duke dreamt that his disease turned into two boys, who said, “That is a skilful physician; it is to be feared he will hurt us; how shall we get out of his way?” Then one of them said: “If we take our place above the heart and below the throat, what can he do to us?” When the physician arrived, he said, “Nothing can be done for this disease. Its seat is above the heart and below the throat. If I assail it (with medicine), it will be of no use; if I attempt to puncture it, it cannot be reached. Nothing can be done for it.” The duke said, “He is a skilful physician”, gave him large gifts, and send him back to [Qin].” ref

“In the sixth month, on the day [bingwu], the marquis wished to taste the new wheat, and made the superintendent of his fields present some. While the baker was getting it ready, [the marquis] called the witch of [Sangtian], showed her the wheat and put her to death. As the marquis was about to taste the wheat, he felt it necessary to go to the privy, into which he fell, and so died. One of the servants that waited on him had dreamt in the morning that he carried the marquis on his back up to heaven. The same at mid-day carried him on his back out from the privy, and was afterwards buried alive with him.” ref

“Commentators have attempted to explain why the wu merely interpreted the duke’s dream but did not perform a healing ritual or exorcism, and why the duke waited until the prediction had failed before ordering the execution. Boileau suggests the wu was executed in presumed responsibility for the Zhao ancestral spirit’s attack. Second, in 552 BCE a wu named Gao 皋 both appears in and divines about a dream of Zhongxing Xianzi. After conspiring in the murder of Duke Li of Jin, Zhongxing dreams that the duke’s spirit gets revenge.” ref

“In autumn, the marquis of [Jin] invaded our northern border. [Zhongxing Xianzi] prepared to invade [Qi]. (Just then), he dreamt that he was maintaining a suit with duke [Li], in which the case was going against him, when the duke struck him with a [ge] on his head, which fell down before him. He took his head up, put it on his shoulders, and ran off, when he saw the wizard [Gao] of [Gengyang]. A day or two after, it happened that he did see this [Gao] on the road, and told him his dream, and the wizard, who had had the same dream, said to him: “Your death is to happen about this time; but if you have business in the east, you will there be successful [first]”. Xianzi accepted this interpretation.” ref

“Boileau questions: why wasn’t the wu asked by Zhongxin to expel the spirit of the duke? Perhaps because the spirit went through him to curse the officer. Could it be that the wu was involved (his involvement is extremely strong in this affair) in a kind of deal, or is it simply that the wu was aware of two different matters concerning the officer, only one connected to the dream? According to these two stories, wu were feared and considered dangerous. This attitude is also evident in a Zhuangzi story about the shenwu 神巫 “spirit/god shaman” Jixian 季咸 from Zheng. In [Zheng], there was a shaman of the gods named [Jixian]. He could tell whether men would live or die, survive or perish, be fortunate or unfortunate, live a long time or die young, and he would predict the year, month, week, and day as though he were a god himself. When the people of [Zheng] saw him, they all ran out of his way. “As soothsayers.” writes de Groot, “the wu in ancient China no doubt held a place of great importance.” ref

Wu-shamans as officials

“Sinological controversies have arisen over the political importance of wu 巫 in ancient China. Some scholars believe Chinese wu used “techniques of ecstasy” like shamans elsewhere; others believe wu were “ritual bureaucrats” or “moral metaphysicians” who did not engage in shamanistic practices. Chen Mengjia wrote a seminal article that proposed Shang kings were wu-shamans.” ref

“In the oracle bone inscriptions are often encountered inscriptions stating that the king divined or that the king inquired in connections with wind- or rain-storms, rituals, conquests, or hunts. There are also statements that “the king made the prognostication that …,” pertaining to weather, the border regions, or misfortunes and diseases; the only prognosticator ever recorded in the oracle bone inscriptions was the king … There are, in addition, inscriptions describing the king dancing to pray for rain and the king prognosticating about a dream. All of these were activities of both king and shaman, which means in effect that the king was a shaman.” ref

“Chen’s shaman-king hypothesis was supported by Kwang-chih Chang who cited the Guoyu story about Shao Hao severing heaven-earth communication (above). This myth is the most important textual reference to shamanism in ancient China, and it provides the crucial clue to understanding the central role of shamanism in ancient Chinese politics. Heaven is where all the wisdom of human affairs lies. … Access to that wisdom was, of course, requisite for political authority. In the past, everybody had had that access through the shamans. Since heaven had been severed from earth, only those who controlled that access had the wisdom – hence the authority – to rule. Shamans, therefore, were a crucial part of every state court; in fact, scholars of ancient China agree that the king himself was actually head shaman.” ref

“Some modern scholars disagree. For instance, Boileau calls Chen’s hypothesis “somewhat antiquated being based more on an a priori approach than on history” and says, In the case of the relationship between wu and wang [king], Chen Mengjia did not pay sufficient attention to what the king was able to do as a king, that is to say, to the parts of the king’s activities in which the wu was not involved, for example, political leadership as such, or warfare. The process of recognition must also be taken into account: it is probable that the wu was chosen or acknowledged as such according to different criteria to those adopted for the king. Chen’s concept of the king as the head wu was influenced by Frazer‘s theories about the origin of political power: for Frazer the king was originally a powerful sorcerer.” ref

“The Shujing “Classic of History” lists Wu Xian 巫咸 and Wu Xian 巫賢 as capable administrators of the Shang royal household. The Duke of Zhou tells Prince Shao 召 that: I have heard that of ancient time, when King Tang had received the favoring decree, he had with him Yi Yin, making his virtue like that of great Heaven. Tai Jia, again, had Bao Heng. Tai Wu had Yi Zhi and Chen Hu, through whom his virtue was made to affect God; he had also [巫咸] Wu Xian, who regulated the royal house; Zu Yi had [巫賢] Wu Xian. Wu Ding had Gan Pan. These ministers carried out their principles and effected their arrangements, preserving and regulating the empire of [Shang], so that, while its ceremonies lasted, those sovereigns, though deceased, were assessors to Heaven, while it extended over many years.” ref

“According to Boileau, In some texts, Wu Xian senior is described as being in charge of the divination using [shi 筮] achilea. He was apparently made a high god in the kingdom of Qin 秦 during the Warring States period. The Tang subcommentary interprets the character wu of Wu Xian father and son as being a cognomen, the name of the clan from which the two Xian came. It is possible that in fact the text referred to two Shang ministers, father and son, coming from the same eponymous territory wu. Perhaps, later, the name (wu 巫) of these two ministers has been confused with the character wu (巫) as employed in other received texts.” ref

“Wu-shamans participated in court scandals and dynastic rivalries under Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141-87 BCE), particularly regarding the crime of wugu 巫蠱 (with gu “venom-based poison”) “sorcery; casting harmful spells”. In 130 BCE, Empress Chen Jiao was convicted of using shamans from Yue to conduct wugu magic. She “was dismissed from her position and a total of 300 persons who were involved in the case were executed”, their heads were cut off and exposed on stakes. In 91 BCE, an attempted coup against crown prince Liu Ju involved accusations of practicing wugu, and subsequently “no less than nine long months of bloody terrorism, ending in a tremendous slaughter, cost some tens of thousands their lives!.” ref

“Ever since Emperor Wu of Han established Confucianism as the state religion, the ruling classes have shown increasing prejudice against shamanism. Some modern writers view the traditional Confucianist disdain for female shamans as sexism. Schafer wrote: In the opinion of the writer, the Chou ruling class was particularly hostile to women in government, and regarded the ancient fertility rites as impure. This anti-female tendency was even more marked in the state of Lu, where Confucius approved of the official rain-ceremony in which men alone participated. There was, within ancient China, a heterogeneity of culture areas, with female shamans favored in some, males in others. The “licentiousness” of the ceremonies of such a state as Cheng (doubtless preserving the ancient Shang traditions and customs) was a byword among Confucian moralists. Confucius’ state seems on the other hand to have taken the “respectable” attitude that the sexes should not mingle in the dance, and that men were the legitimate performers of the fertility rites. The general practice of the later Chou period, or at least the semi-idealized picture given of the rites of that time in such books as the Chou li, apparently prescribed a division of magical functions between men and women. The former generally play the role of exorcists, the latter of petitioners. This is probably related to the metaphysical belief that women, embodying the principle yin, were akin to the spirits, whereas men, exemplifying the element yang, were naturally hostile to them.” ref

“Accepting the tradition that Chinese shamans were women (i.e., wu 巫 “shamaness” as opposed to xi 覡 “shaman”), Kagan believes: One of the main themes in Chinese history is the unsuccessful attempt by the male Confucian orthodoxy to strip women of their public and sacred powers and to limit them to a role of service … Confucianists reasserted daily their claim to power and authority through the promotion of the phallic ancestor cult which denied women religious representation and excluded them from the governmental examination system which was the path to office, prestige, and status. In addition, Unschuld refers to a “Confucian medicine” based upon systematic correspondences and the idea that illnesses are caused by excesses (rather than demons).” ref

“The Zhouli provides detailed information about the roles of wu-shamans. It lists, “Spirit Mediums as officials on the payroll of the Zhou Ministry of Rites (Liguan 禮官, or Ministry of Spring, Chun guan 春官).” This text differentiates three offices: the Siwu 司巫 “Manager/Director of Shamans”, Nanwu 男巫 “Male Shamans”, and Nüwu 女巫 “Female Shamans”. The managerial Siwu, who was of Shi 士 “Gentleman; Yeoman” feudal rank, yet was not a wu, supervised “the many wu.” ref

“The Managers of the Spirit Mediums are in charge of the policies and orders issued to the many Spirit Mediums. When the country suffers a great drought, they lead the Spirit Mediums in dancing the rain-making ritual (yu 雩). When the country suffers a great calamity, they lead the Spirit Mediums in enacting the long-standing practices of Spirit Mediums (wuheng 巫恆). At official sacrifices, they [handle] the ancestral tablets in their receptacles, the cloth on which the spirits walk, and the box containing the reeds [for presenting the sacrificial foodstuffs]. In all official sacrificial services, they guard the place where the offerings are buried. In all funerary services, they are in charge of the rituals by which the Spirit Mediums make [the spirits] descend (jiang 降).” ref

“The Nanwu and Nüwu have different shamanic specializations, especially regarding inauspicious events like sickness, death, and natural disaster. The Male Spirit Mediums are in charge of the si 祀 and yan 衍 Sacrifices to the Deities of the Mountains and Rivers. They receive the honorific titles [of the deities], which they proclaim into the [four] directions, holding reeds. In the winter, in the great temple hall, they offer [or: shoot arrows] without a fixed direction and without counting the number. In the spring, they make proclamations and issue bans so as to remove sickness and disease. When the king offers condolence, they together with the invocators precede him.” ref

“The Female Mediums are in charge of anointing and ablutions at the exorcisms that are held at regular times throughout the year. When there is a drought or scorching heat, they dance in the rain-making ritual (yu). When the queen offers condolence, they together with the invocators precede her. In all great calamities of the state, they pray, singing and wailing. (part 26)” ref

“Von Falkenhausen concludes: If we are to generalize from the above enumeration, we find that the Spirit Mediums’ principal functions are tied up with averting evil and pollution. They are especially active under circumstances of inauspiciousness and distress. In case of droughts and calamities, they directly address the supernatural powers of Heaven and Earth. Moreover, they are experts in dealing with frightful, dangerous ghosts (the ghosts of the defunct at the time of the funeral, the evil spirits at the exorcism, and the spirits of disease) and harmful substances (unburied dead bodies during visits of condolence and all manner of impure things at the lustration festival).” ref

Chu Ci: Chu Ci

“The poetry anthology Chu Ci, especially its older pieces, is largely characterized by its shamanic content and style, as explicated to some extent by sinologist David Hawkes: passim]]). Among other points of interest are the intersection of Shamanic traditions and mythology/folk religion in the earlier textual material, such as Tianwen (possibly based on even more ancient shamanic temple murals), the whole question of the interpretation of the 11 verses of the Jiu Ge (Nine Songs) as the libretto of a shamanic dramatic performance, the motif of shamanic spirit flight from Li Sao through subsequent pieces, the evidence of possible regional variations in wu shamanism between Chu, Wei, Qi, and other states (or shamanic colleges associated with those regions), and the suggestion that some of the newer textual material was modified to please Han Wudi, by Liu An, the Prince of Huainan, or his circle. The Chu Ci contents have traditionally been chronologically divided into an older, pre-Han dynasty group, and those written during the Han Dynasty. Of the traditionally-considered to be the older works (omitting the mostly prose narratives, “Bu Ju” and “Yu Fu“) David Hawkes considers the following sections to be “functional, explicitly shamanistic”: Jiu Ge, Tian Wen, and the two shamanic summons for the soul, “The Great Summons” and “Summons of the Soul“. Regarding the other, older pieces he considers that “shamanism, if there is any” to be an incidental poetic device, particularly in the form of descriptions of the shamanic spirit journey.” ref

Background

“The mainstream of Chinese literacy and literature is associated with the shell and bone oracular inscriptions from recovered archeological artifacts from the Shang dynasty and with the literary works of the Western Zhou dynasty, which include the classic Confucian works. Both are associated with the northern Chinese areas. South of the traditional Shang and Zhou areas was the land (and water) of Chu. Politically and to some extent culturally distinct from the Zhou dynasty and its later 6 devolved hegemonic states, Chu was the original source and inspiration for the poems anthologized during the Han dynasty under the title Chu Ci, literally meaning something like “the literary material of Chu.” ref

“Despite the tendency of Confucian-oriented government officials to suppress wu shamanic beliefs and practice, in the general area of Chinese culture, the force of colonial conservatism and the poetic voice of Qu Yuan and other poets combined to contribute an established literary tradition heavily influenced by wu shamanism to posterity. Shamanic practices as described anthropologically are generally paralleled by descriptions of wu practices as found in the Chu Ci, and in Chinese mythology more generally.” ref

Li Sao, Yuan You, and Jiu Bian: Li Sao, Yuan You, and Jiu Bian

“The signature poem of the Chu Ci is the poem Li Sao. By China’s “first poet”, Qu Yuan, a major literary device of the poem is the shamanic spirit journey. “Yuan You“, literally “The Far-off Journey” features shamanic spirit flight as a literary device, as does Jiu Bian, as part of its climactic ending. In the Li Sao, two individual shaman are specified, Ling Fen (靈氛) and Wu Xian (巫咸). This Wu Xian may or may not be the same as the (one or more) historical person(s) named Wu Xian. Hawkes suggests an equation of the word ling in the Chu dialect with the word wu.” ref

Questioning Heaven: Heavenly Questions

“The Heavenly Questions (literally “Questioning Heaven”) is one of the ancient repositories of Chinese myth and a major cultural legacy. Propounded as a series of questions, the poem provides insight and provokes questions about the role of wu shaman practitioners in society and history.” ref

Jiu Ge: Jiu Ge

“The Jiu Ge may be read as the lyrical preservation of a shamanic dramatic performance. Apparently typical of at least one variety of shamanism of the Chu area of the Yangzi River basin, the text exhibits a marked degree of eroticism in connection with shamanic invocations.” ref

Summoning the soul: Hun and po

“Summoning the soul (hun) of the possibly dead was a feature of ancient culture. The 2 Chu Ci pieces of this type may be authentic transcriptions of such a process.” ref

Individual wu shaman

“Various individual wu shaman are alluded to in the Chu Ci. In some cases the binomial nomenclature is unclear, referring perhaps to one or two persons; for example, in the case of Peng Xian, who appears likely to represent Wu Peng and Wu Xian, which is a common type of morphological construction in Classical Chinese poetry. David Hawkes refers to some wu shaman as “Shaman Ancestors”. Additionally, the distinction between humans and transcendent divinities tends not to be explicit in the received Chu Ci text. In some cases, the individual wu shaman are known from other sources, such as the Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas). The name of some individual shaman includes “Wu” (巫) in the normal position of the family surname, for example, in the case of Wu Yang (巫陽, “Shaman Bright”). Wu Yang is the major speaker in Zhao Hun/Summons for the Soul. He also appears in Shanhaijing together with Wu Peng (巫彭): 6 wu shaman are depicted together reviving a corpse, with Wu Peng holding the Herb of Immortality.” ref

“In the Li Sao, two individual shaman are specified: Ling Fen (靈氛) and Wu Xian (巫咸). This Wu Xian may or may not be the same as the (one or more) historical person(s) named Wu Xian. Hawkes suggests an equation of the word ling in the Chu dialect with the word wu. In Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas), the name of some individual shaman includes “Wu” (巫) in the normal position of the family surname, for example, in the case of the following list, where the 6 are depicted together reviving a corpse, with Wu Peng holding the Herb of Immortality. Wu Peng and Wu Yang and others are also known from the Chu Ci poetry anthology. Wu Yang is the major speaker in Zhao Hun (also known as, Summons for the Soul).” ref

“From Hawkes:

- The six shamans receiving a corpse: Wu Yang (巫陽, “Shaman Bright”), Wu Peng (巫彭), Wu Di (巫抵), Wu Li (巫履) [Tang reconstruction *Lǐ, Hanyu Pinyin Lǚ], Wu Fan (巫凡), Wu Xiang (巫相)

- Ten other individuals named Wuin Shanhaijing: Wu Xian (巫咸), Wu Ji (巫即), Wu Fen (or Ban) (巫肦), Wu Peng (巫彭), Wu Gu (巫姑), Wu Zhen (巫真), Wu Li (巫禮), Wu Di (巫抵), Wu Xie (巫謝), Wu Luo (巫羅).” ref

“Modern: Chinese folk religion

Aspects of Chinese folk religion are sometimes associated with “shamanism”. De Groot provided descriptions and pictures of hereditary shamans in Fujian, called saigong (pinyin shigong) 師公. Paper analyzed tongji mediumistic activities in the Taiwanese village of Bao’an 保安. Shamanistic practices of Tungusic peoples are also found in China. Most notably, the Manchu Qing dynasty introduced Tungusic shamanistic practice as part of their official cult (see Shamanism in the Qing dynasty). Other remnants of Tungusic shamanism are found within the territory of the People’s Republic of China. documented Chuonnasuan (1927–2000), the last shaman of the Oroqen in northeast China.” ref

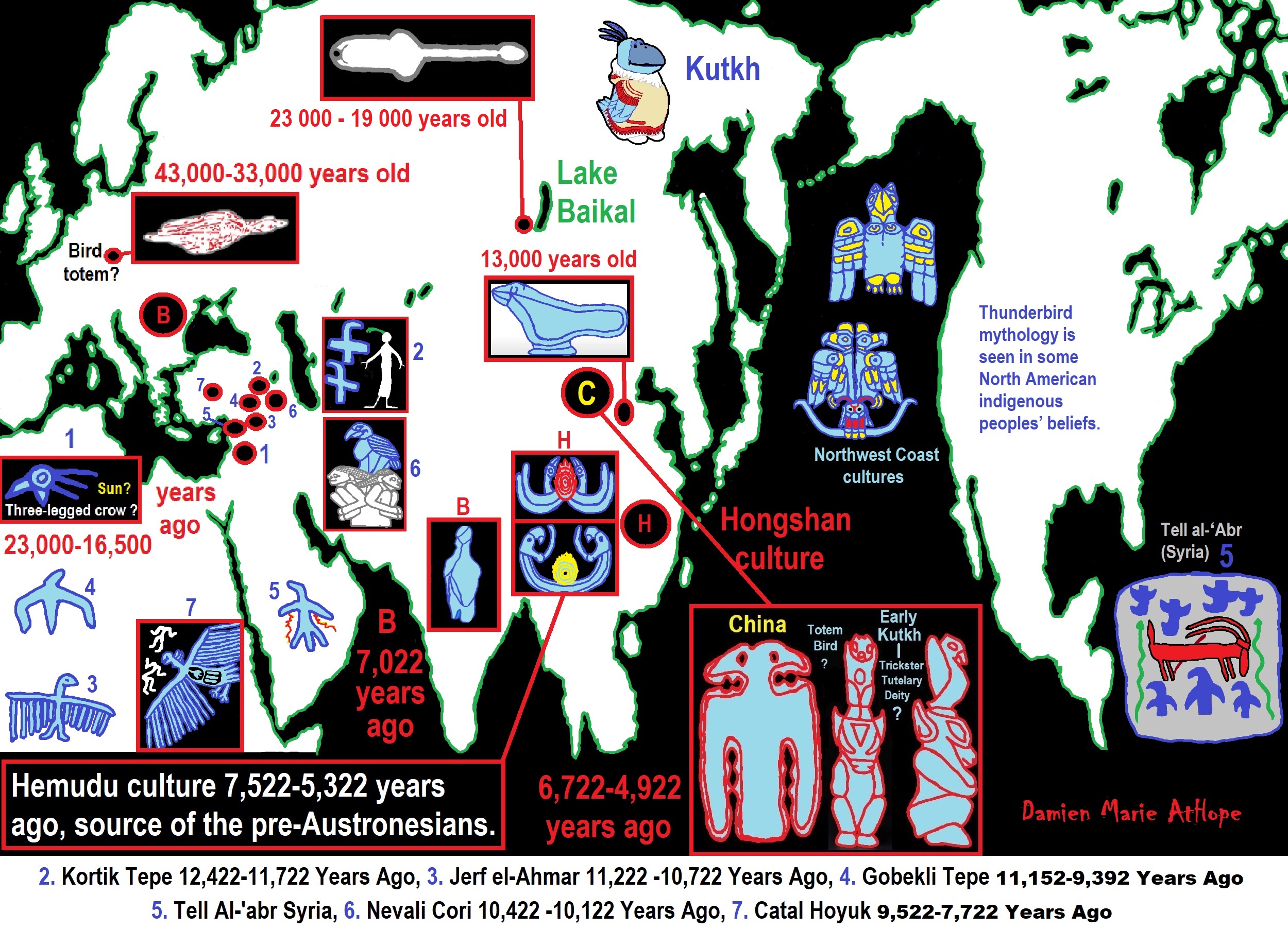

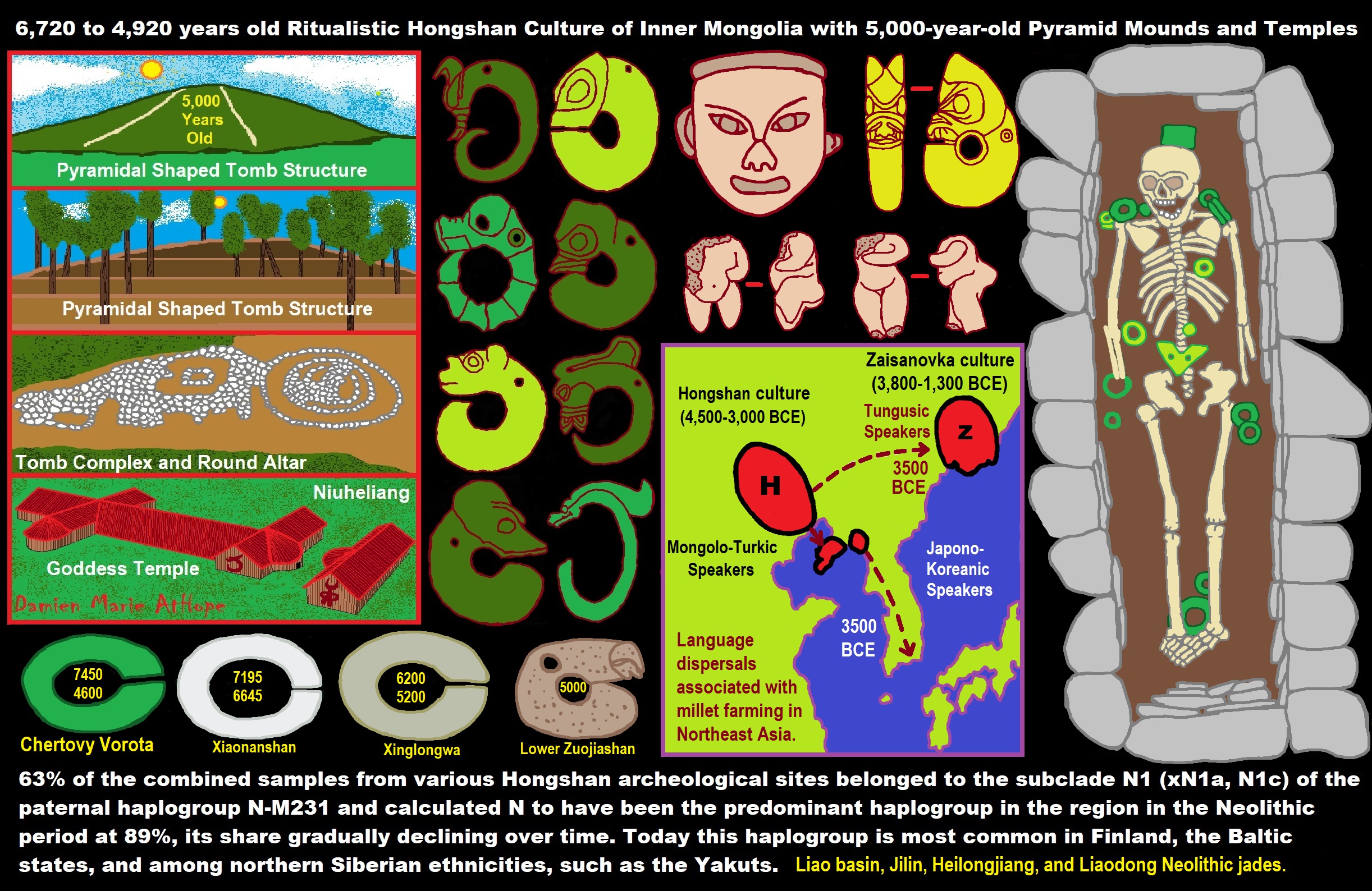

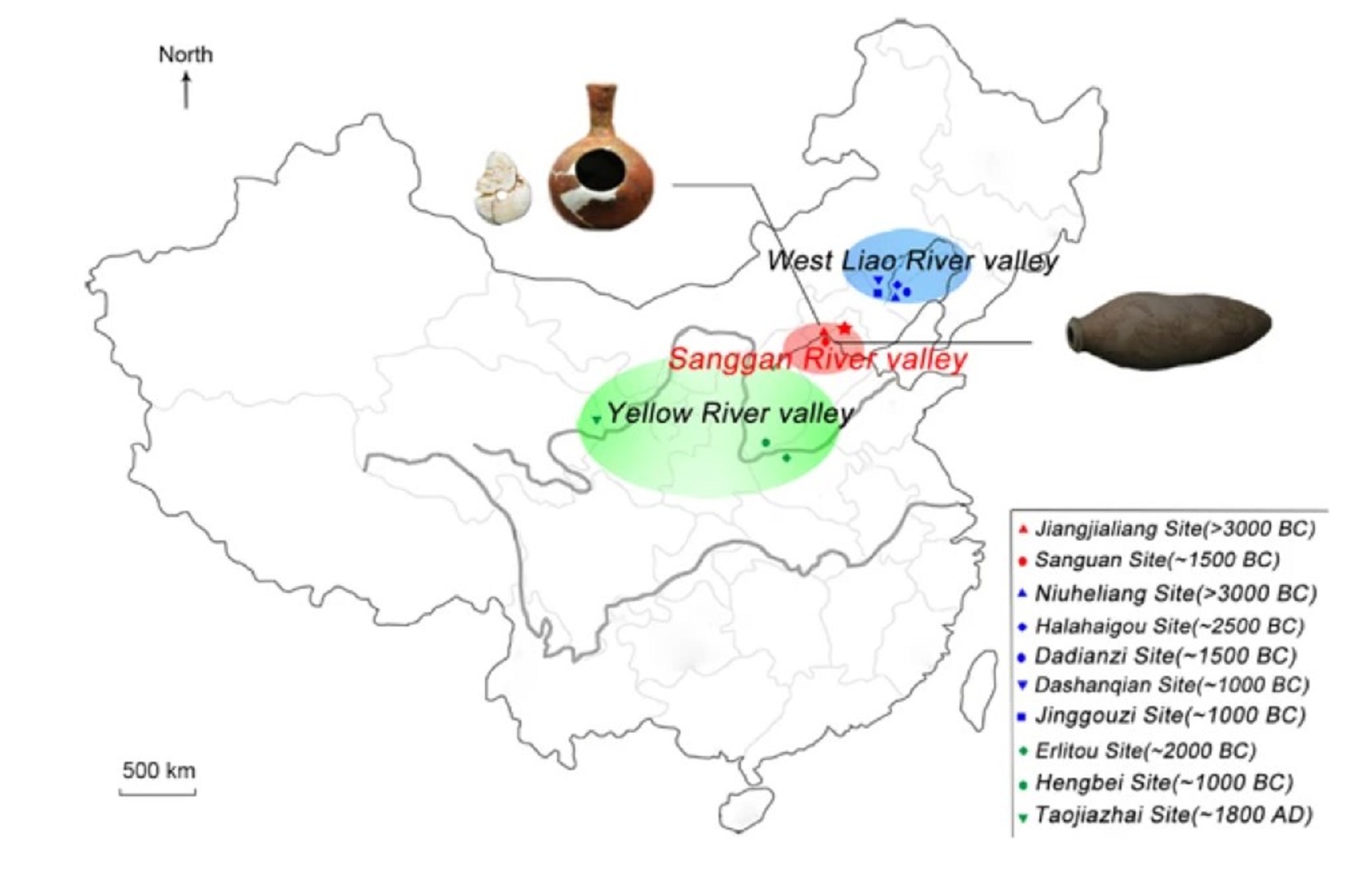

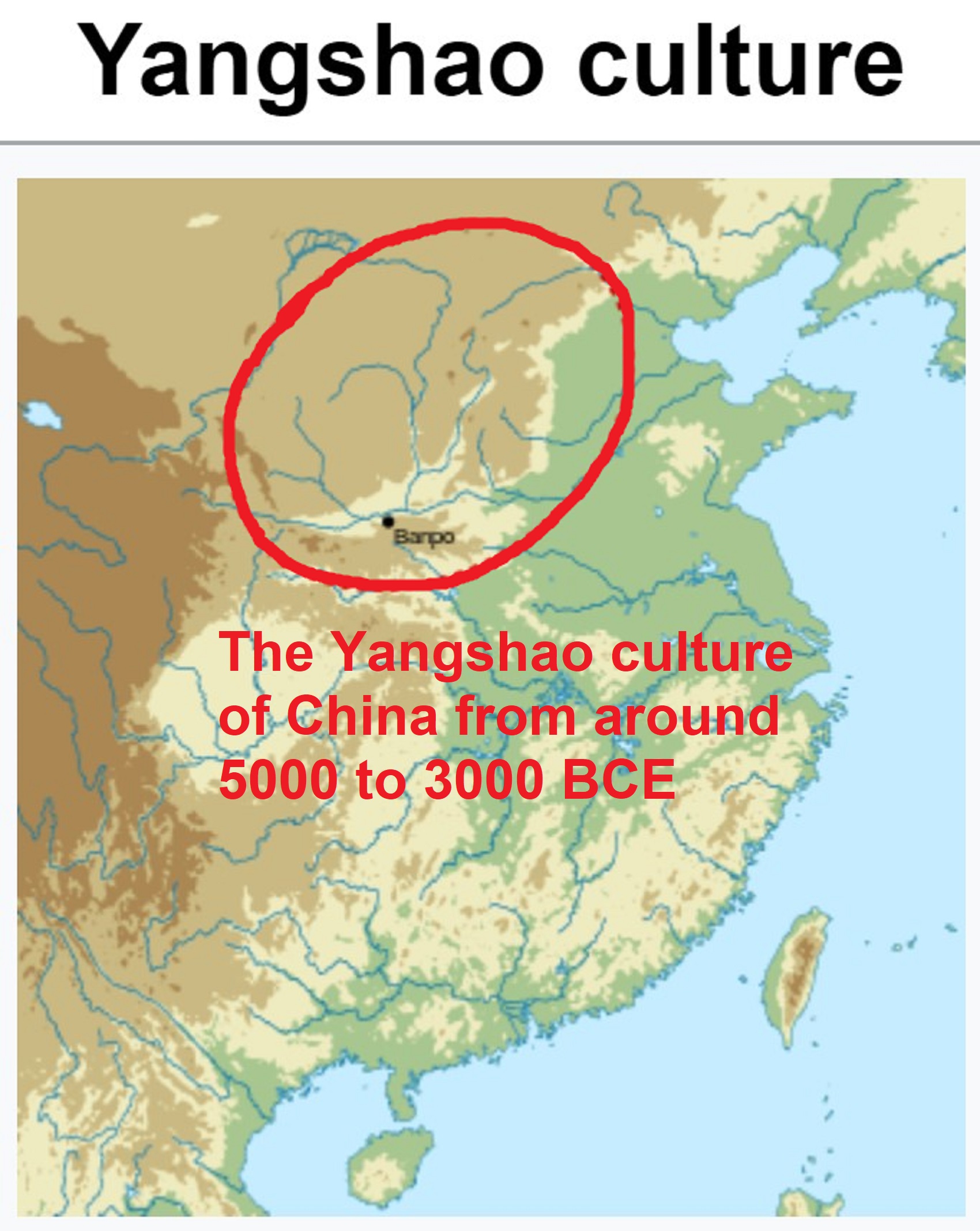

Chinese shamanism

“Chinese shamanism, alternatively called Wuism (Chinese: 巫教; pinyin: wū jiào; lit. ‘wu religion, shamanism, witchcraft‘; alternatively 巫觋宗教 wū xí zōngjiào), refers to the shamanic religious tradition of China. Its features are especially connected to the ancient Neolithic cultures such as the Hongshan culture. Chinese shamanic traditions are intrinsic to Chinese folk religion. Various ritual traditions are rooted in original Chinese shamanism: contemporary Chinese ritual masters are sometimes identified as wu by outsiders, though most orders don’t self-identify as such. Also Taoism has some of its origins from Chinese shamanism: it developed around the pursuit of long life (shou 壽/寿), or the status of a xian (仙, “mountain man”, “holy man”).” ref

“The Chinese word wu 巫 “shaman, wizard”, indicating a person who can mediate with the powers generating things (the etymological meaning of “spirit”, “god”, or nomen agentis, virtus, energeia), was first recorded during the Shang dynasty (ca. 1600-1046 BCE), when a wu could be either sex. During the late Zhou dynasty (1045-256 BCE) wu was used to specify “female shaman; sorceress” as opposed to xi 覡 “male shaman; sorcerer” (which first appears in the 4th century BCE Guoyu). Other sex-differentiated shaman names include nanwu 男巫 for “male shaman; sorcerer; wizard”; and nüwu 女巫, wunü 巫女, wupo 巫婆, and wuyu 巫嫗 for “female shaman; sorceress; witch”. The word tongji 童乩 (lit. “youth diviner”) “shaman; spirit-medium” is a near-synonym of wu. Modern Chinese distinguishes native wu from “Siberian shaman“: saman 薩滿 or saman 薩蠻; and from Indian Shramana “wandering monk; ascetic”: shamen 沙門, sangmen 桑門, or sangmen 喪門.” ref

“Berthold Laufer (1917:370) proposed an etymological relation between Mongolian bügä “shaman”, Turkic bögü “shaman”, Chinese bu, wu (shaman), buk, puk (to divine), and Tibetan aba (pronounced ba, sorcerer). Coblin (1986:107) puts forward a Sino-Tibetan root *mjaɣ “magician; sorcerer” for Chinese wu < mju < *mjag 巫 “magician; shaman” and Written Tibetan ‘ba’-po “sorcerer” and ‘ba’-mo “sorcereress” (of the Bön religion). Further connections are to the bu-mo priests of Zhuang Shigongism and the bi-mo priests of Bimoism, the Yi indigenous faith. Also Korean mu 무 (of Muism) is cognate to Chinese wu 巫. Schuessler lists some etymologies: wu could be cognate with wu 舞 “to dance”; wu could also be cognate with mu 母 “mother” since wu, as opposed to xi 覡, were typically female; wu could be a loanword from Iranian *maghu or *maguš “magi; magician”, meaning an “able one; specialist in ritual”. Mair (1990) provides archaeological and linguistic evidence that Chinese wu < *myag 巫 “shaman; witch, wizard; magician” was maybe a loanword from Old Persian *maguš “magician; magi“. Mair connects the nearly identical Chinese Bronze script for wu and Western heraldic cross potent ☩, an ancient symbol of a magus or magician, which etymologically descend from the same Indo-European root.” ref

Early history

“The Chinese religion from the Shang dynasty onwards developed around ancestral worship. The main gods from this period are not forces of nature in the Sumerian way, but deified virtuous men. The ancestors of the emperors were called di (帝), and the greatest of them was called Shangdi (上帝, “the Highest Lord”). He is identified with the dragon (Kui 夔), symbol of the universal power (qi).” ref

“Cosmic powers dominate nature: the Sun, the Moon, stars, winds and clouds were considered informed by divine energies. The earth god is She (社) or Tu (土). The Shang period had two methods to enter in contact with divine ancestors: the first is the numinous-mystical wu (巫) practice, involving dances and trances; and the second is the method of the oracle bones, a rational way. The Zhou dynasty, succeeding the Shang, was more rooted in an agricultural worldview. They opposed the ancestor-gods of the Shang, and gods of nature became dominant. The utmost power in this period was named Tian (天, “heaven”). With Di (地, “earth”) he forms the whole cosmos in a complementary duality.” ref

Qing period: Shamanism in the Qing dynasty

“The Manchu rulers of the Qing dynasty (1636–1912) introduced substantial elements of Tungusic shamanism to China. Hong Taiji (1592–1643) put shamanistic practices in the service of the state, notably by forbidding others to erect new shrines (tangse) for ritual purposes. In the 1620s and 1630s, the Qing ruler conducted shamanic sacrifices at the tangse of Mukden, the Qing capital. In 1644, as soon as the Qing seized Beijing to begin their conquest of China, they named it their new capital and erected an official shamanic shrine there. In the Beijing tangse and in the women’s quarters of the Forbidden City, Qing emperors and professional shamans (usually women) conducted shamanic ceremonies until the abdication of the dynasty in 1912.” ref

“In 1747 the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796) commissioned the publication of a Shamanic Code to revive and regulate shamanic practices, which he feared were becoming lost. He had it distributed to Bannermen to guide their practice, but we know very little about the effect of this policy. Mongols and Han Chinese were forbidden to attend shamanic ceremonies. Partly because of their secret aspect, these rituals attracted the curiosity of Beijing dwellers and visitors to the Qing capital. French Jesuit Joseph-Marie Amiot published a study on the Shamanic Code, “Rituels des Tartares Mandchous déterminés et fixés par l’empereur comme chef de sa religion” (1773). In 1777 the Qianlong Emperor ordered the code translated into Chinese for inclusion in the Siku quanshu. The Manchu version was printed in 1778, whereas the Chinese-language edition, titled Qinding Manzhou jishen jitian dianli (欽定滿洲祭神祭天典禮), was completed in 1780 or 1782. Even though this “Shamanic Code” did not fully unify shamanic practice among the Bannermen, it “helped systematize and reshape what had been a very fluid and diverse belief system.” ref

Northeast shamanism: Northeast China folk religion

“Shamanism is practiced in Northeast China and is considered different from those of central and southern Chinese folk religion, as it resulted from the interaction of Han religion with folk religion practices of other Tungusic people such as Manchu shamanism. The shaman would perform various ritual functions for groups of believers and local communities, such as moon drum dance and chūmǎxiān (出馬仙 “riding for the immortals”).” ref

“Shamanism saw a decline due to Neo-Confucianism labeling it as untutored and disorderly. This was furthered in the 19th century with the arrival of Western imperialism’s view of shamanism as superstition, opposing their view of science and western religion. The final hit was Maoist China causing all religious practices to disappear from public spaces. While spirit mediums have begun reappearing (mostly in rural China) since the 1980’s, they operate with a low profile, often working from their homes, relying on word of mouth to generate business, or in newly built temples under a Taoist Association membership card to be legitimate under the law. The term shamanism and the religion itself has been critiqued by Western scholars due to an unfair and limited comparison to more favored religions such as Christianity and other modern and more documented religions in Western society.” ref

“Today, the term shamanism has a somewhat negative stigma. Spirit mediums are often viewed as scammers, and are frequently portrayed as such in television shows and comedies. Along with the focus on science, modern medicine, and material culture in China (which created serious doubt in spiritual practices), shamanism is viewed as an opposition to the modern focus of science and medicine in the pursuit of modernizing. The marginalization of shamanism is one of the reasons for it mostly being practiced in rural or less developed areas or in small towns, along with the lack of enforcement of anti-shamanism policies among authorities in rural areas (either because they believe in Shamanism themselves or “look the other way in concession to local beliefs”). Shamanistic practices today include controlling the weather, healing diseases modern medicine can not treat, exorcism of ghosts and demons, and seeing or divining the future.” ref

“Shamanism’s decrease in popularity is not reflected in all areas. It still maintains popularity in many areas in southern China (such as in Chaoshan) and rural northern China. Taiwan (although Taiwan tried to ban Shamanism, in the end only restricting it) still have many who openly practice without the stigma seen in other parts of China.” ref

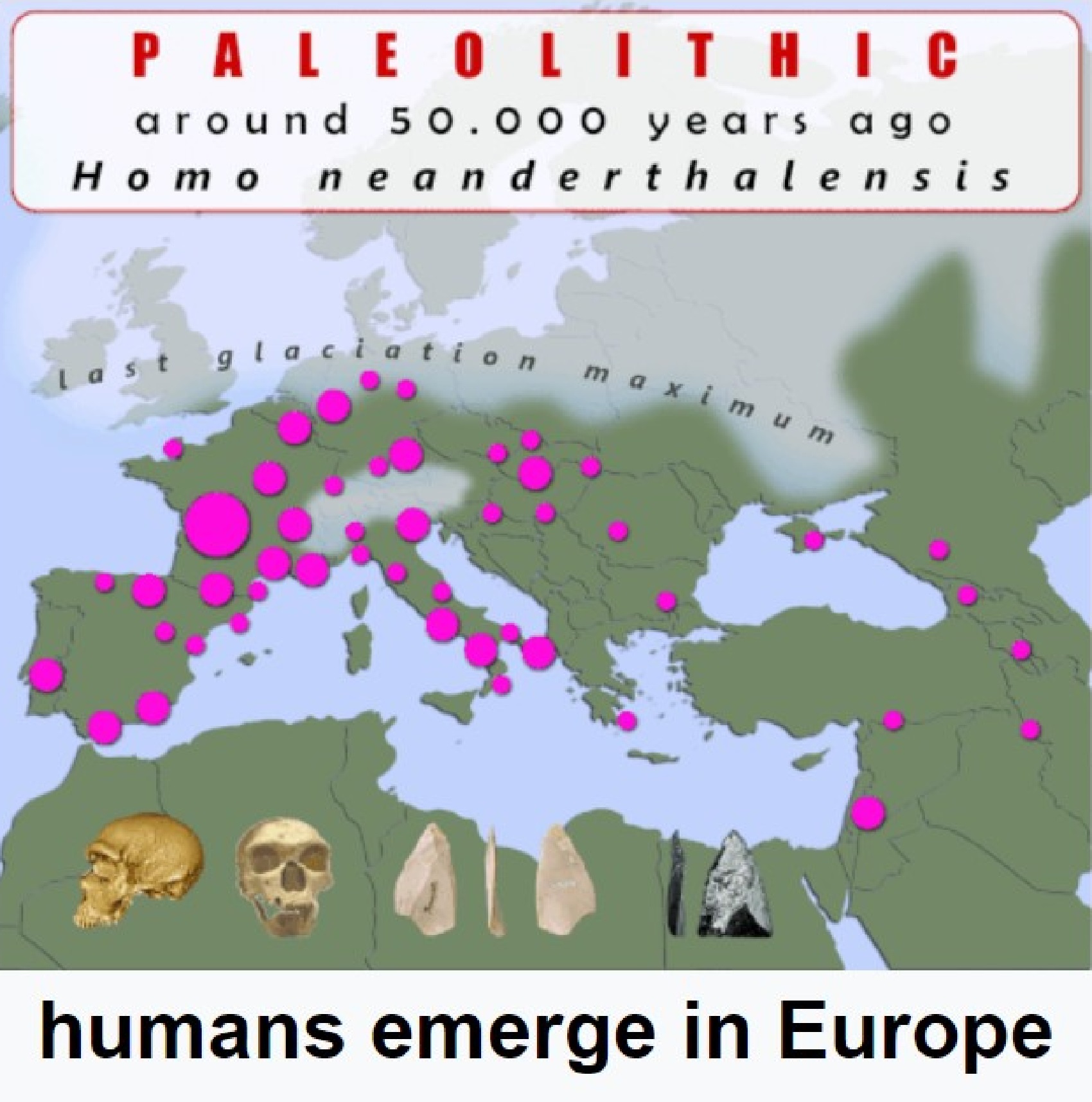

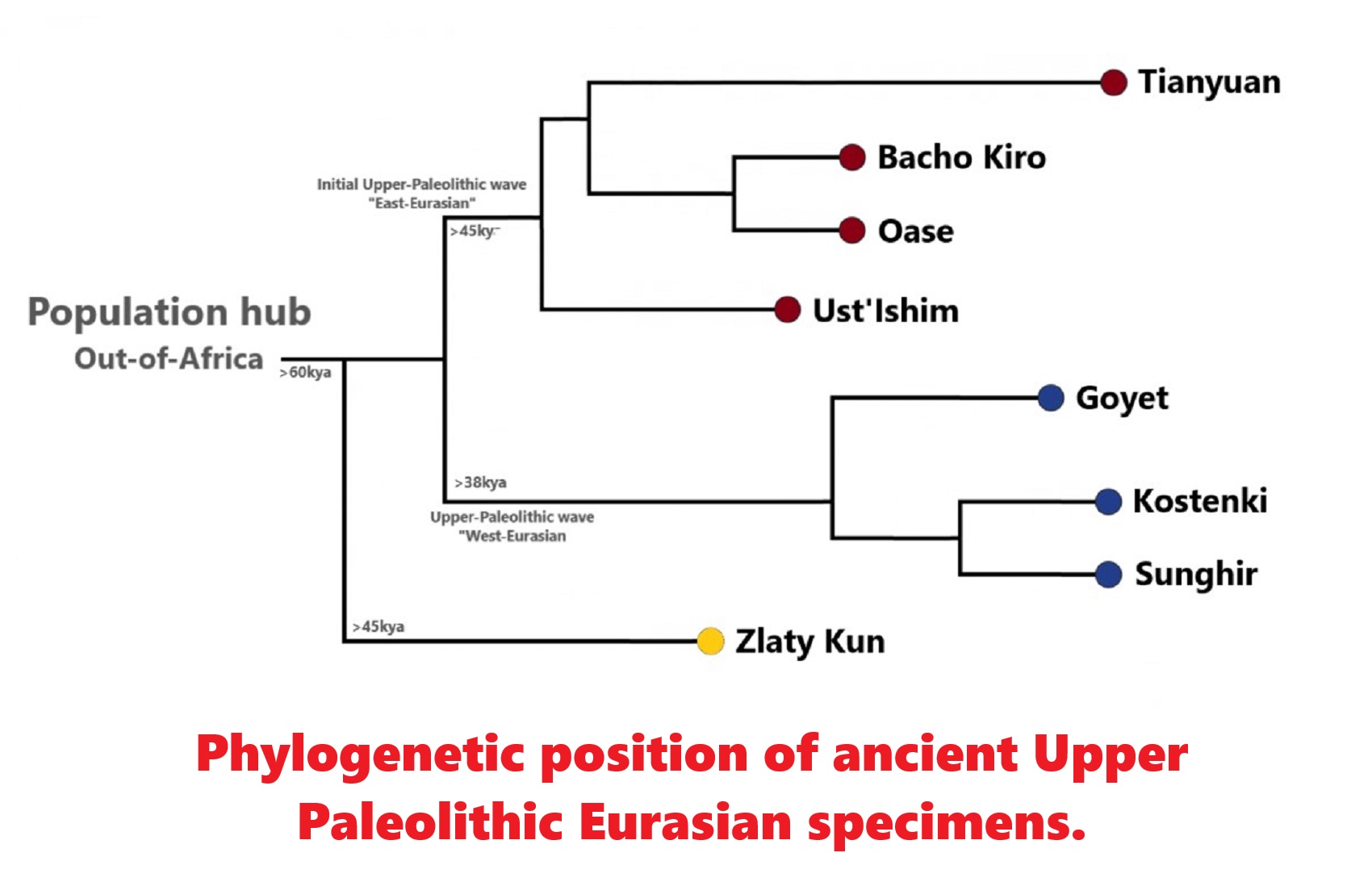

“Homo neanderthalensis emerged in Eurasia between 600,000 and 350,000 years ago as the earliest body of European people that left behind a substantial tradition, a set of evaluable historic data through a rich fossil record in Europe’s limestone caves and a patchwork of occupation sites over large areas. These include Mousterian cultural assemblages. Modern humans arrived in Mediterranean Europe during the Upper Paleolithic between 45,000 and 43,000 years ago, and both species occupied a common habitat for several thousand years. Research has so far produced no universally accepted conclusive explanation as to what caused the Neanderthal’s extinction between 40,000 and 28,000 years ago.” ref

“Homo sapiens arrived in Europe around 45,000 and 43,000 years ago via the Levant and entered the continent through the Danubian corridor, as the fossils at Peștera cu Oase suggest. The fossils’ genetic structure indicates a recent Neanderthal ancestry and the discovery of a fragment of a skull in Israel in 2008 support the notion that humans interbred with Neanderthals in the Levant. After the slow processes of the previous hundreds of thousands of years, a turbulent period of Neanderthal–Homo sapiens coexistence demonstrated that cultural evolution had replaced biological evolution as the primary force of adaptation and change in human societies.” ref

“Generally, small and widely dispersed fossil sites suggest that Neanderthals lived in less numerous and more socially isolated groups than Homo sapiens. Tools and Levallois points are remarkably sophisticated from the outset, but they have a slow rate of variability, and general technological inertia is noticeable during the entire fossil period. Artifacts are of utilitarian nature, and symbolic behavioral traits are undocumented before the arrival of modern humans. The Aurignacian culture, introduced by modern humans, is characterized by cut bone or antler points, fine flint blades, and bladelets struck from prepared cores, rather than using crude flakes. The oldest examples and subsequent widespread tradition of prehistoric art originate from the Aurignacian.” ref

“After more than 100,000 years of uniformity, around 45,000 years ago, the Neanderthal fossil record changed abruptly. The Mousterian had quickly become more versatile and was named the Chatelperronian culture, which signifies the diffusion of Aurignacian elements into Neanderthal culture. Although debated, the fact proved that Neanderthals had, to some extent, adopted the culture of modern Homo sapiens. However, the Neanderthal fossil record completely vanished after 40,000 years BCE. Whether Neanderthals were also successful in diffusing their genetic heritage into Europe’s future population or they simply went extinct and, if so, what caused the extinction cannot conclusively be answered.” ref

“Around 32,000 years ago, the Gravettian culture appeared in the Crimean Mountains (southern Ukraine). By 24,000 BCE, the Solutrean and Gravettian cultures were present in Southwestern Europe. Gravettian technology and culture have been theorized to have come with migrations of people from the Middle East, Anatolia, and the Balkans, and might be linked with the transitional cultures mentioned earlier since their techniques have some similarities and are both very different from Aurignacian ones, but this issue is very obscure. The Gravettian also appeared in the Caucasus and Zagros Mountains but soon disappeared from southwestern Europe, with the notable exception of the Mediterranean coasts of Iberia.” ref

“Around 19,000 BCE, Europe witnesses the appearance of a new culture, known as Magdalenian, possibly rooted in the old Aurignacian one, which soon superseded the Solutrean area and also the Gravettian of Central Europe. However, in Mediterranean Iberia, Italy, the Balkans and Anatolia, epi-Gravettian cultures continued to evolve locally. With the Magdalenian culture, the Paleolithic development in Europe reaches its peak and this is reflected in art, owing to previous traditions of paintings and sculpture.” ref

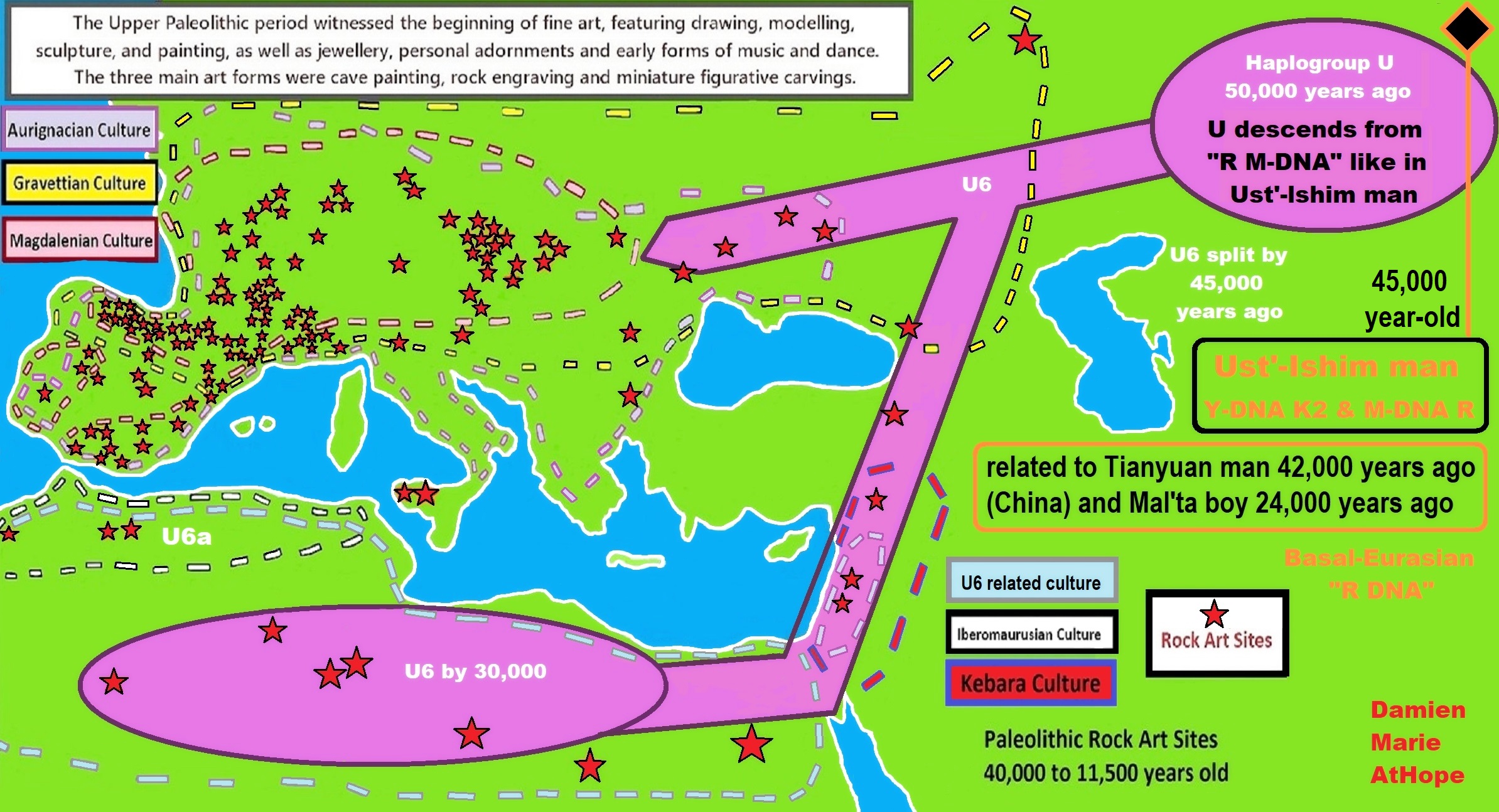

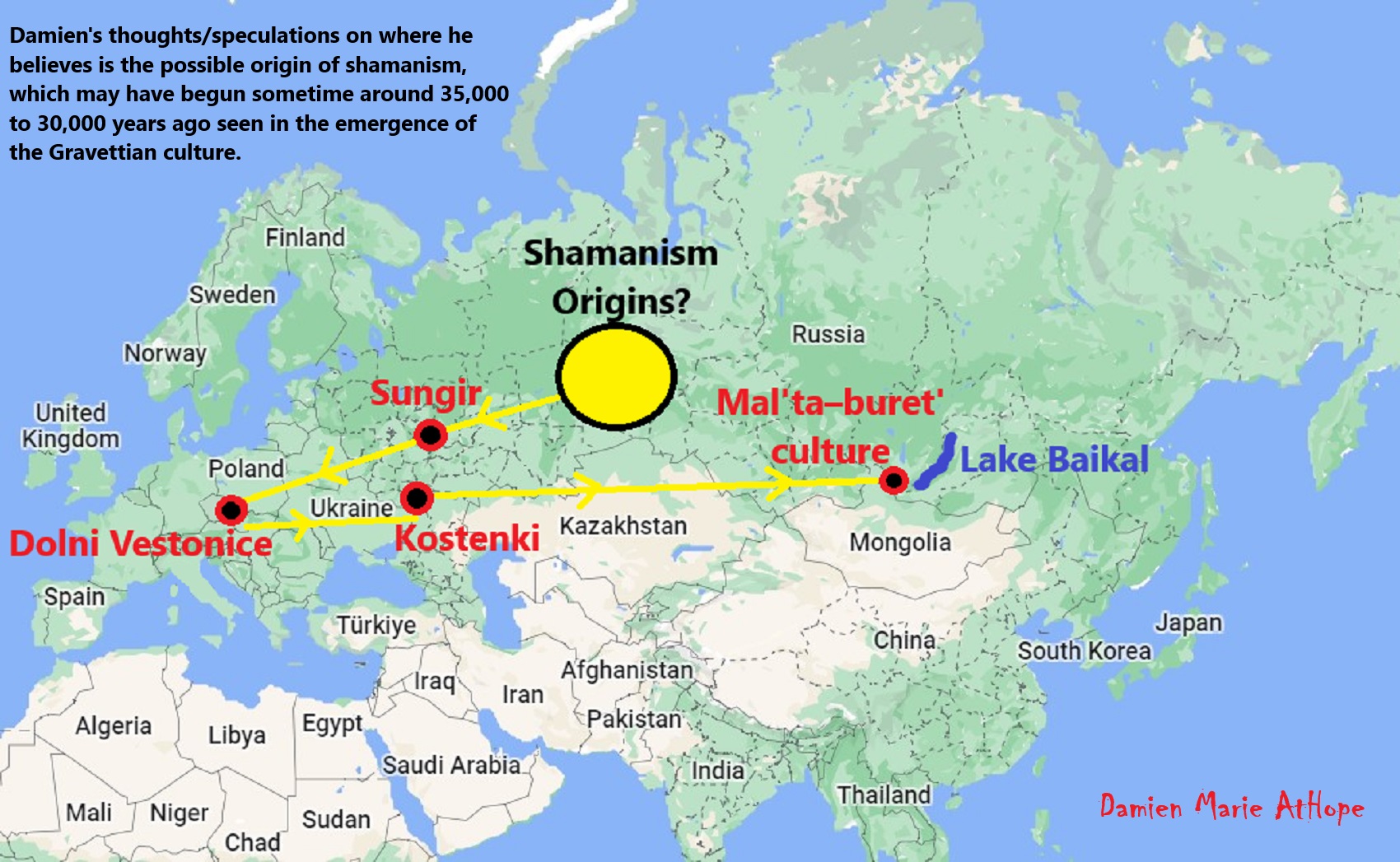

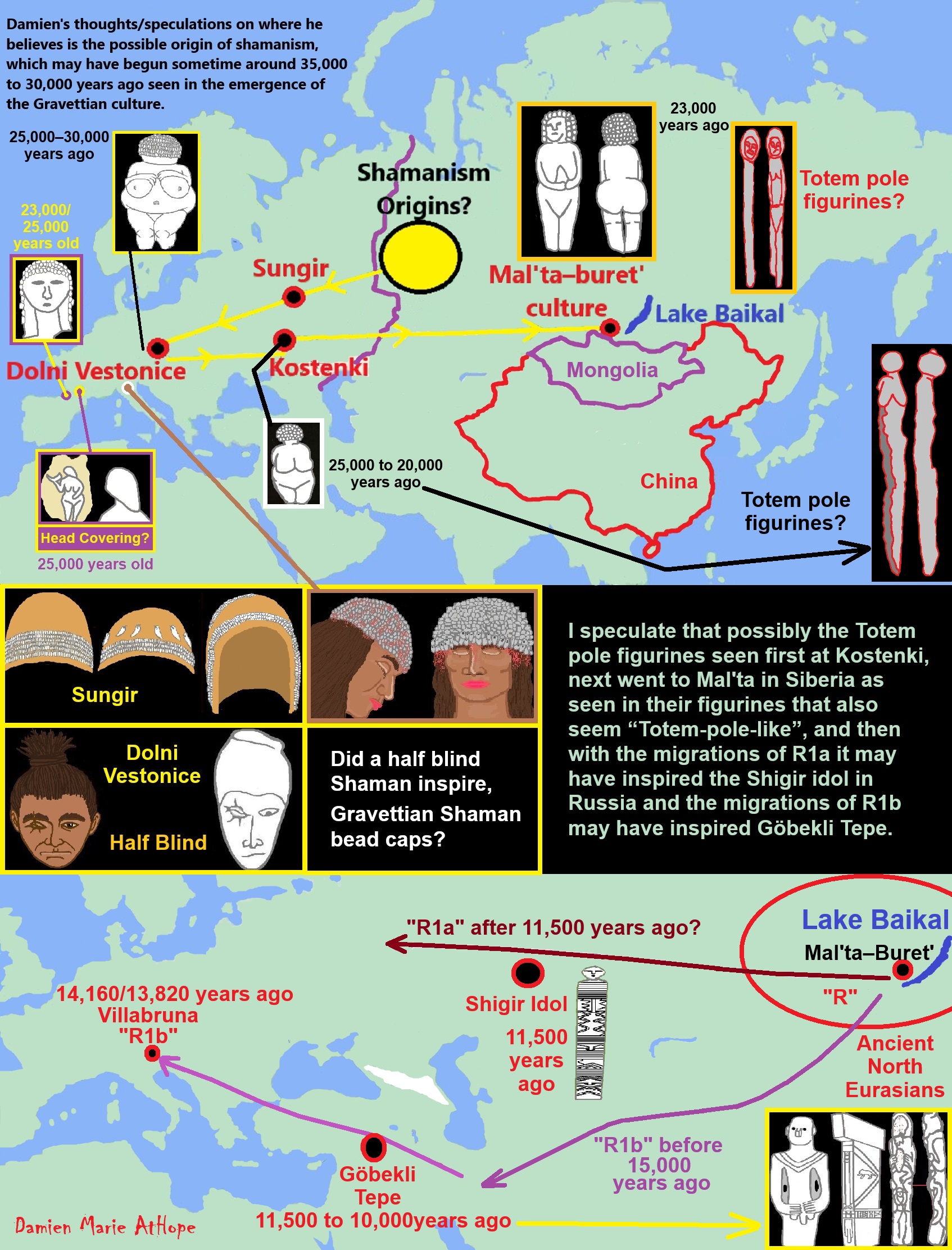

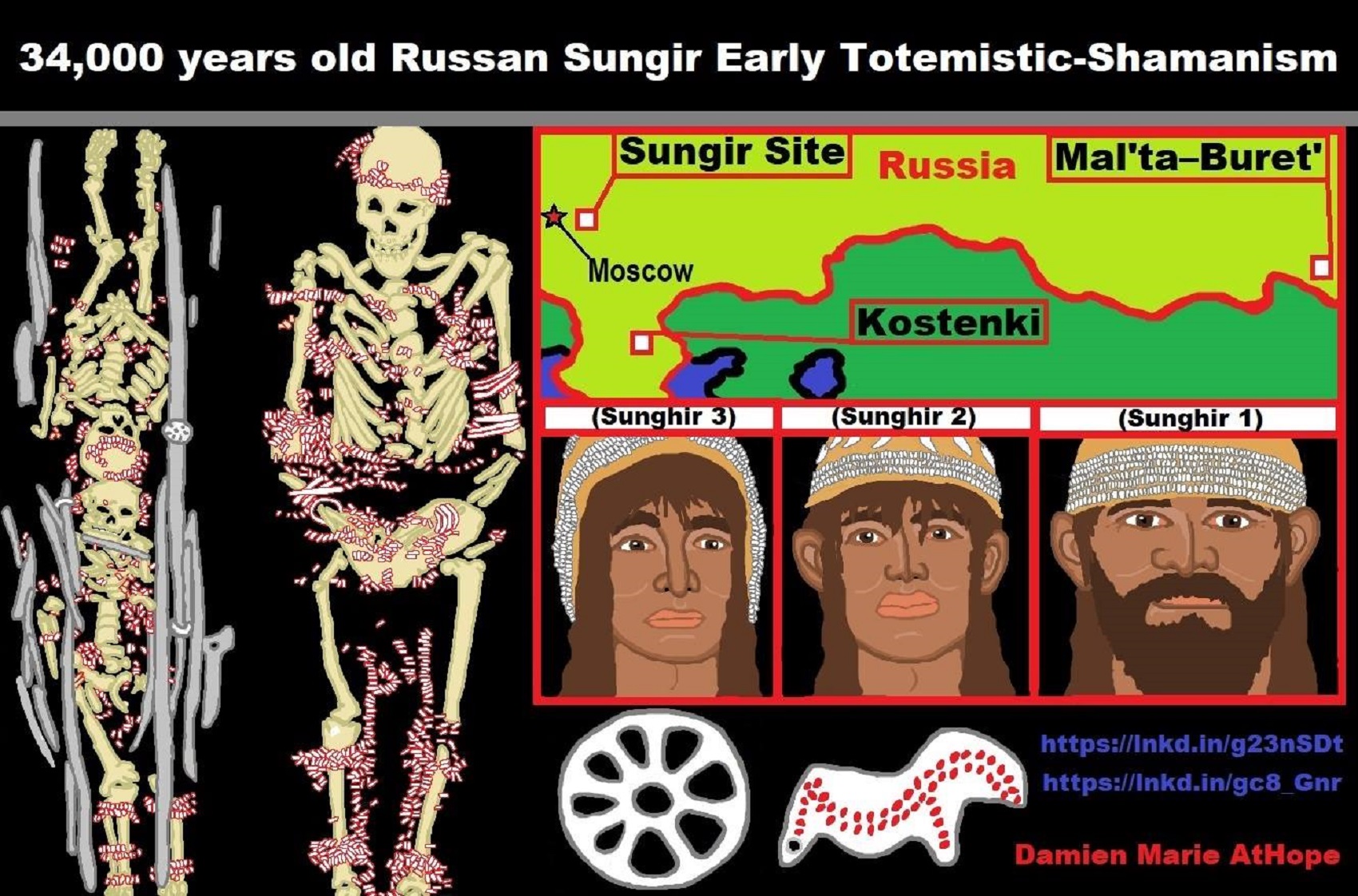

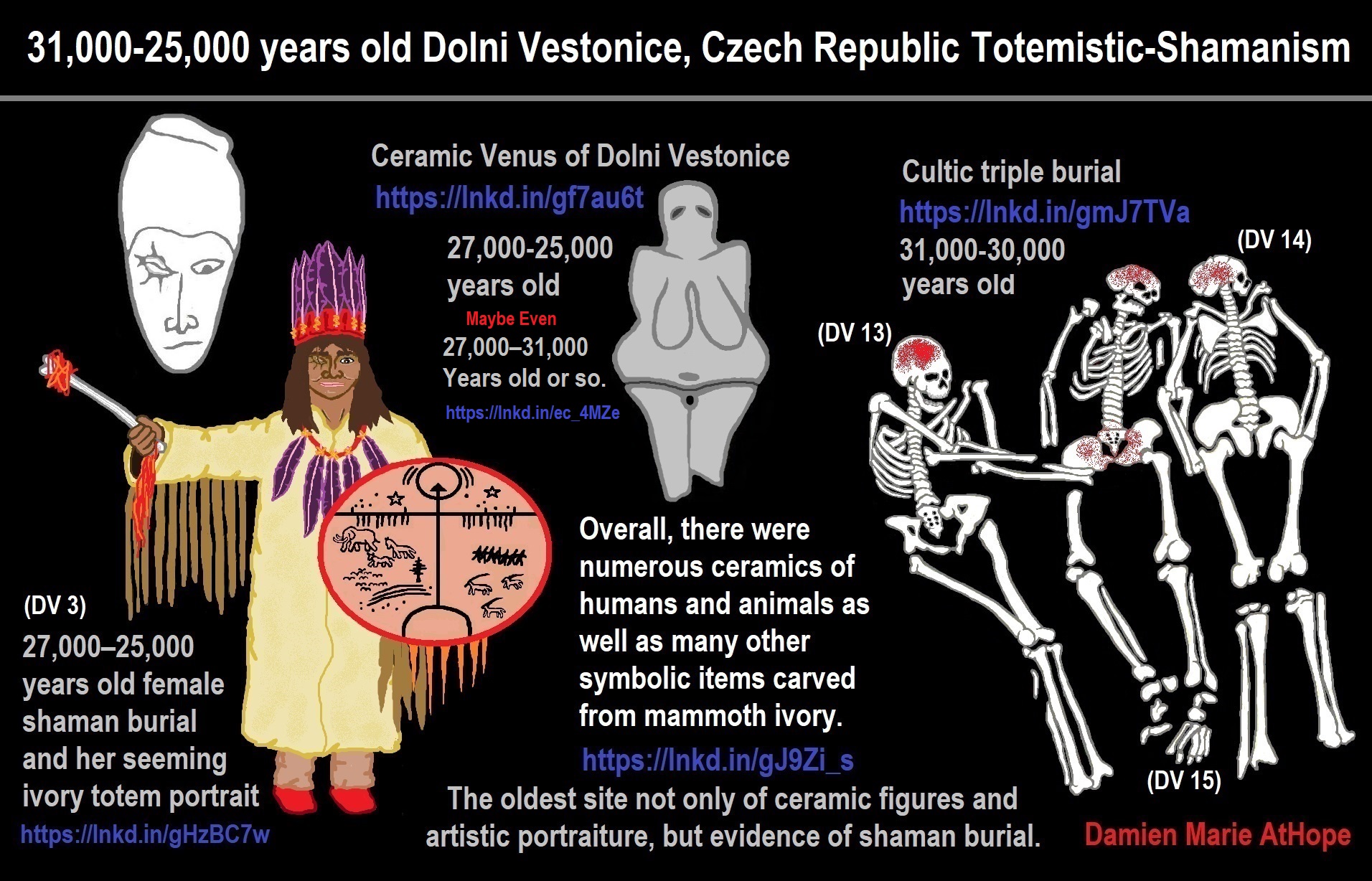

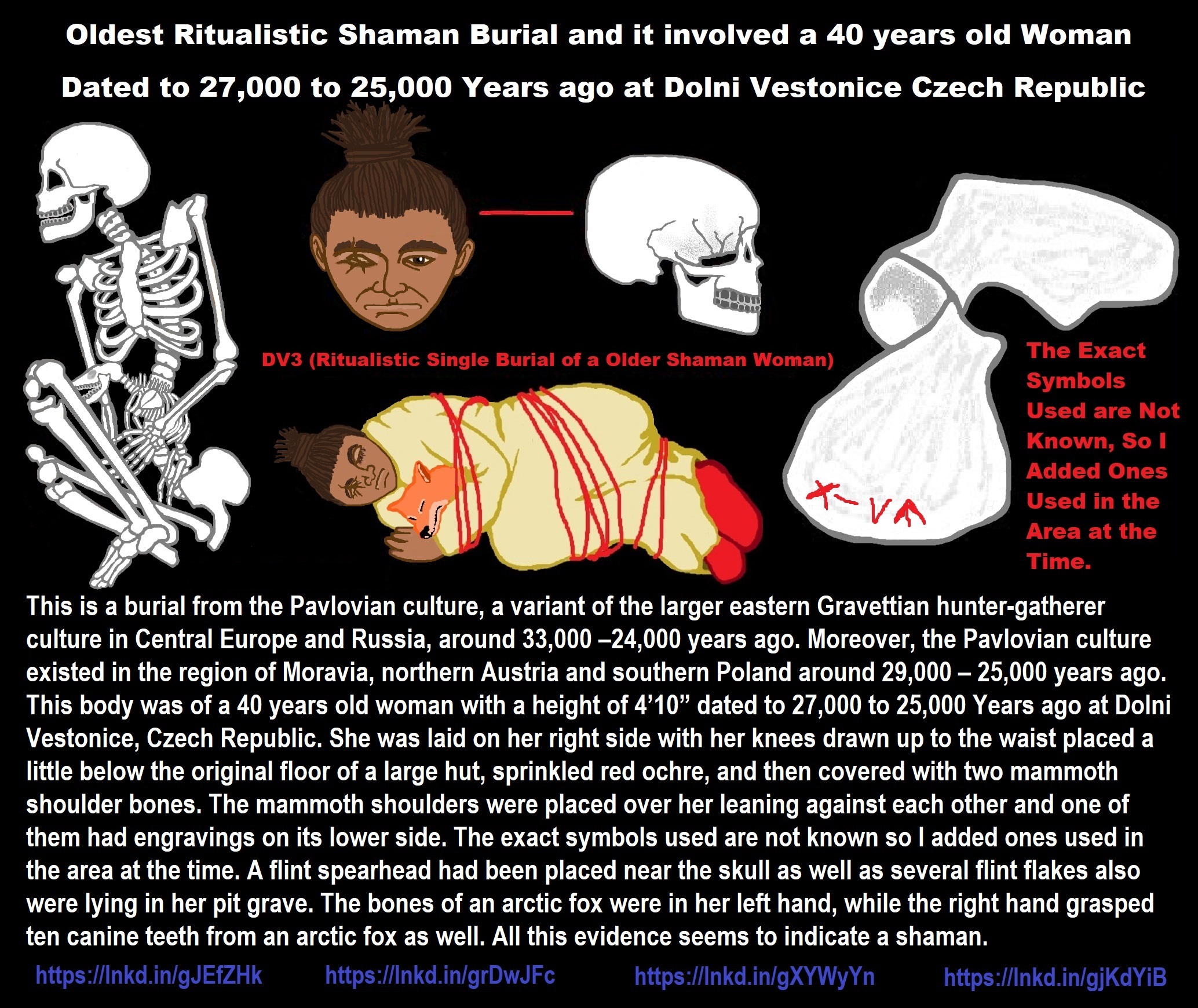

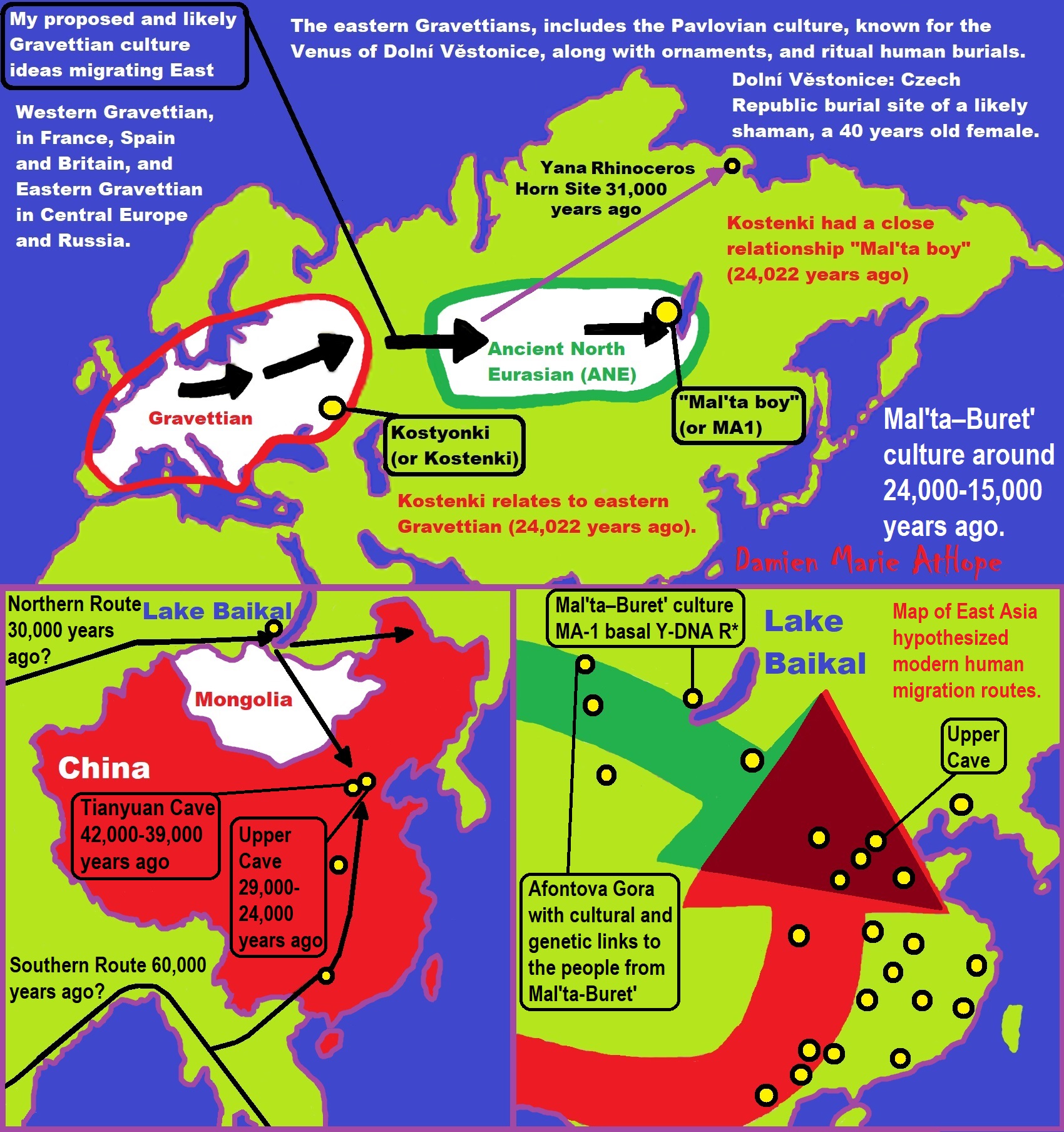

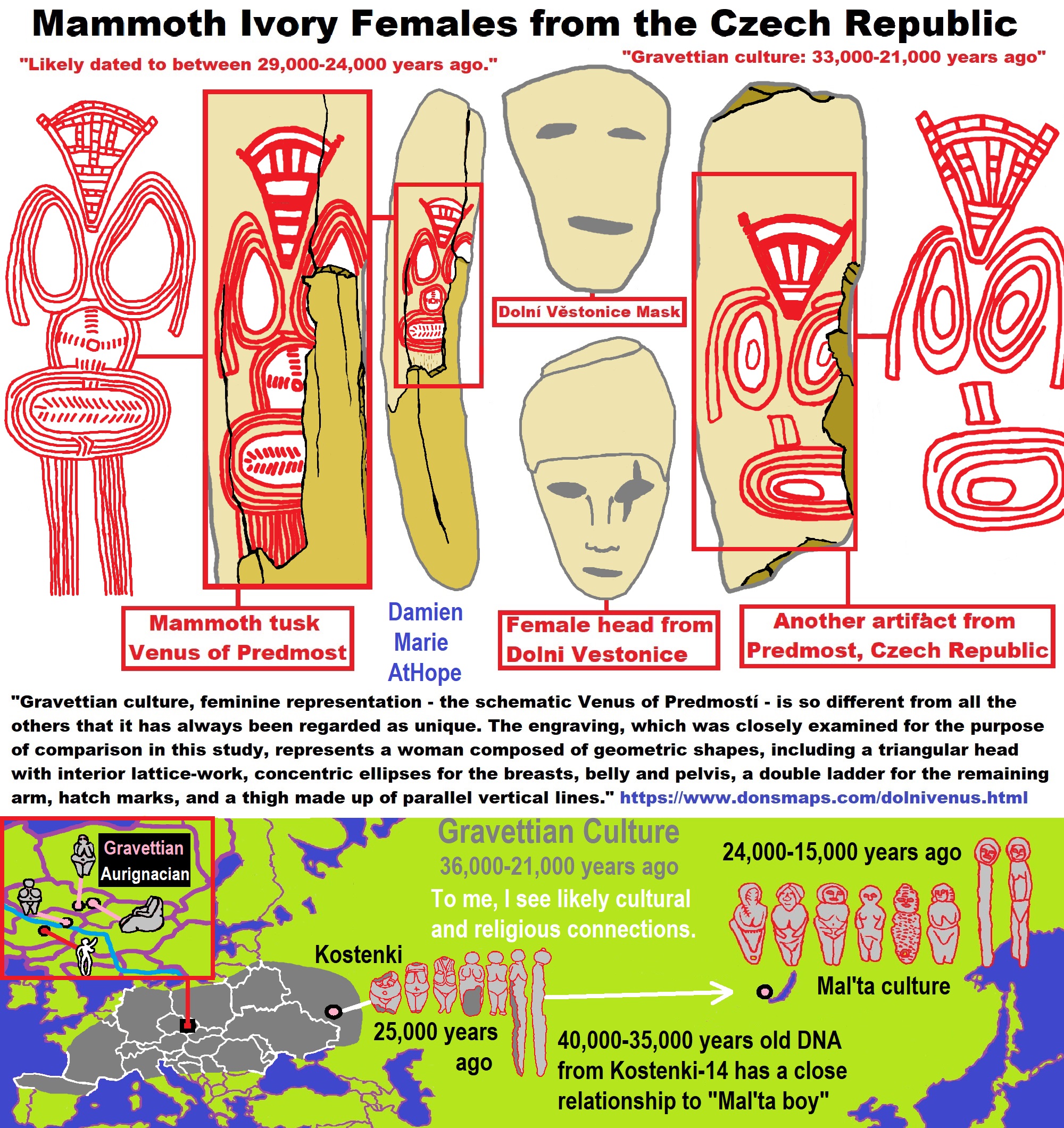

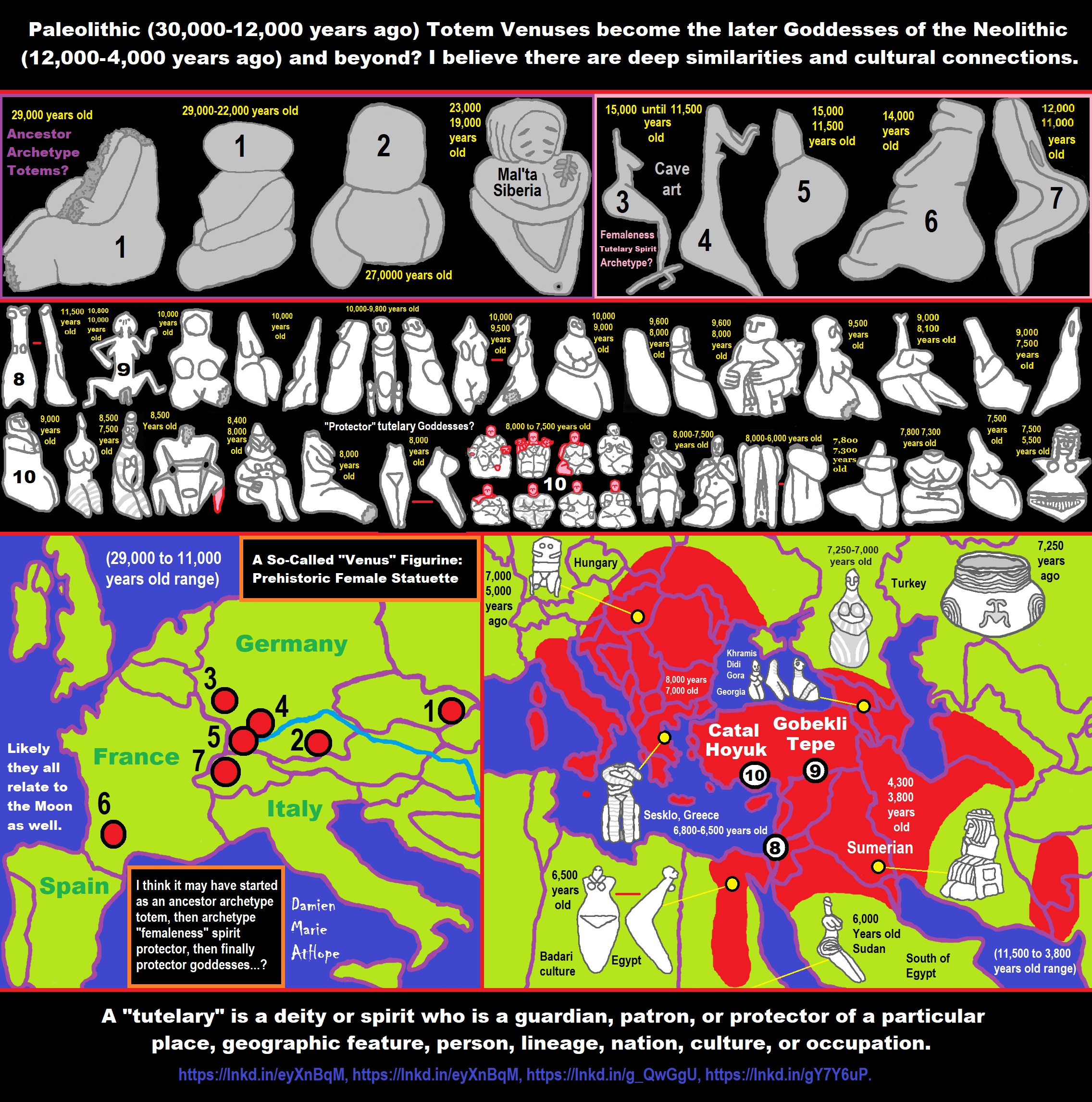

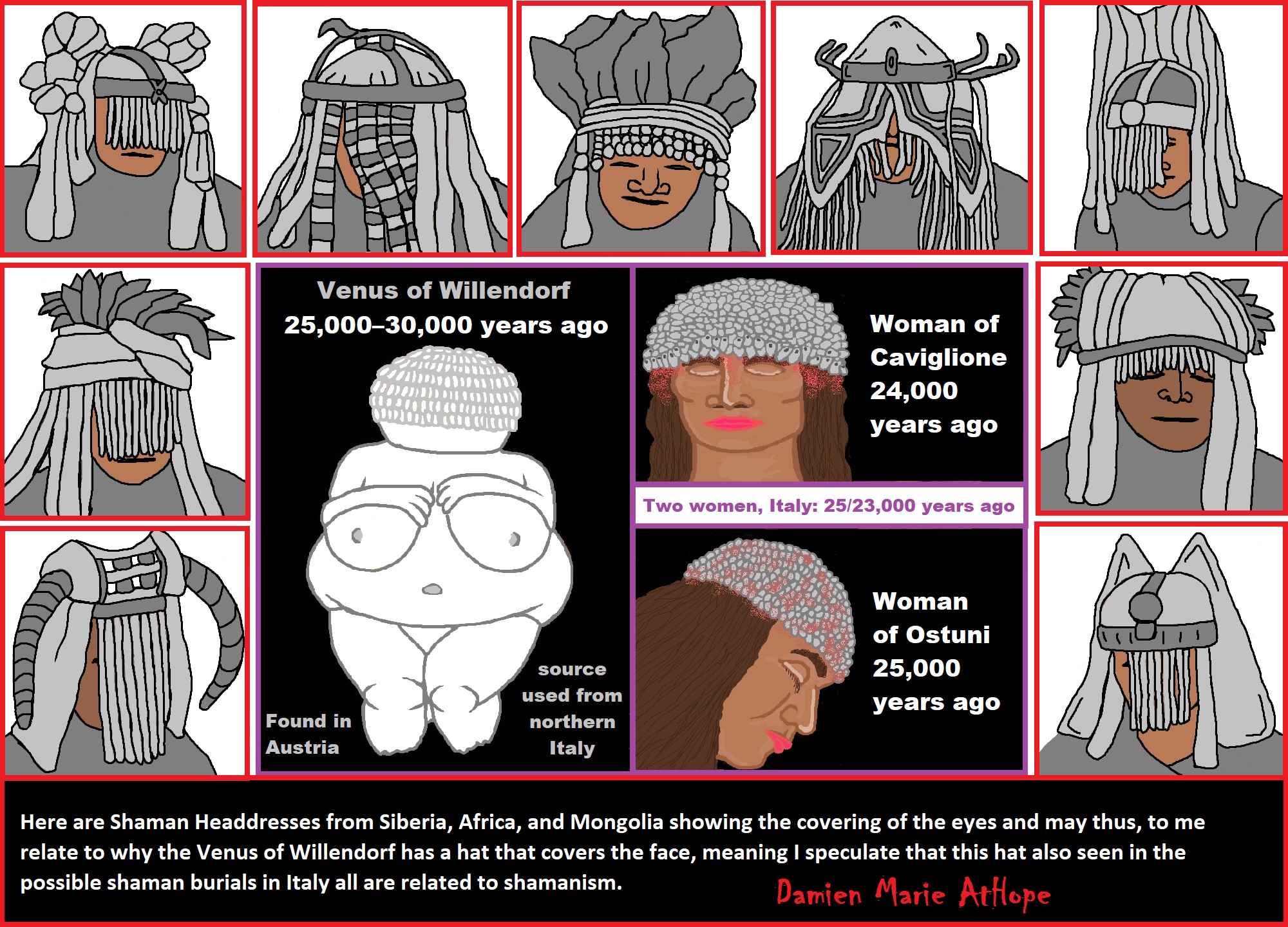

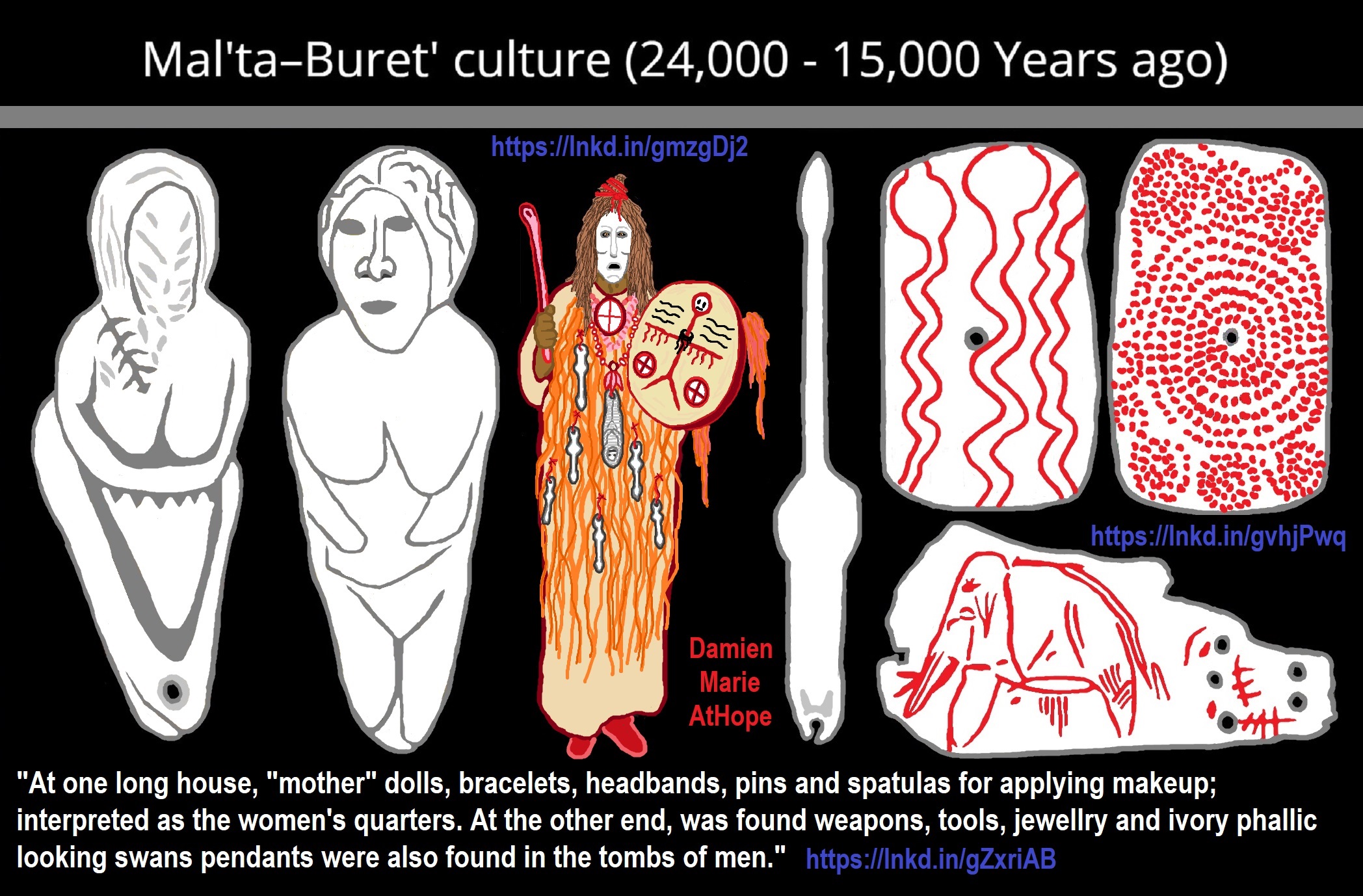

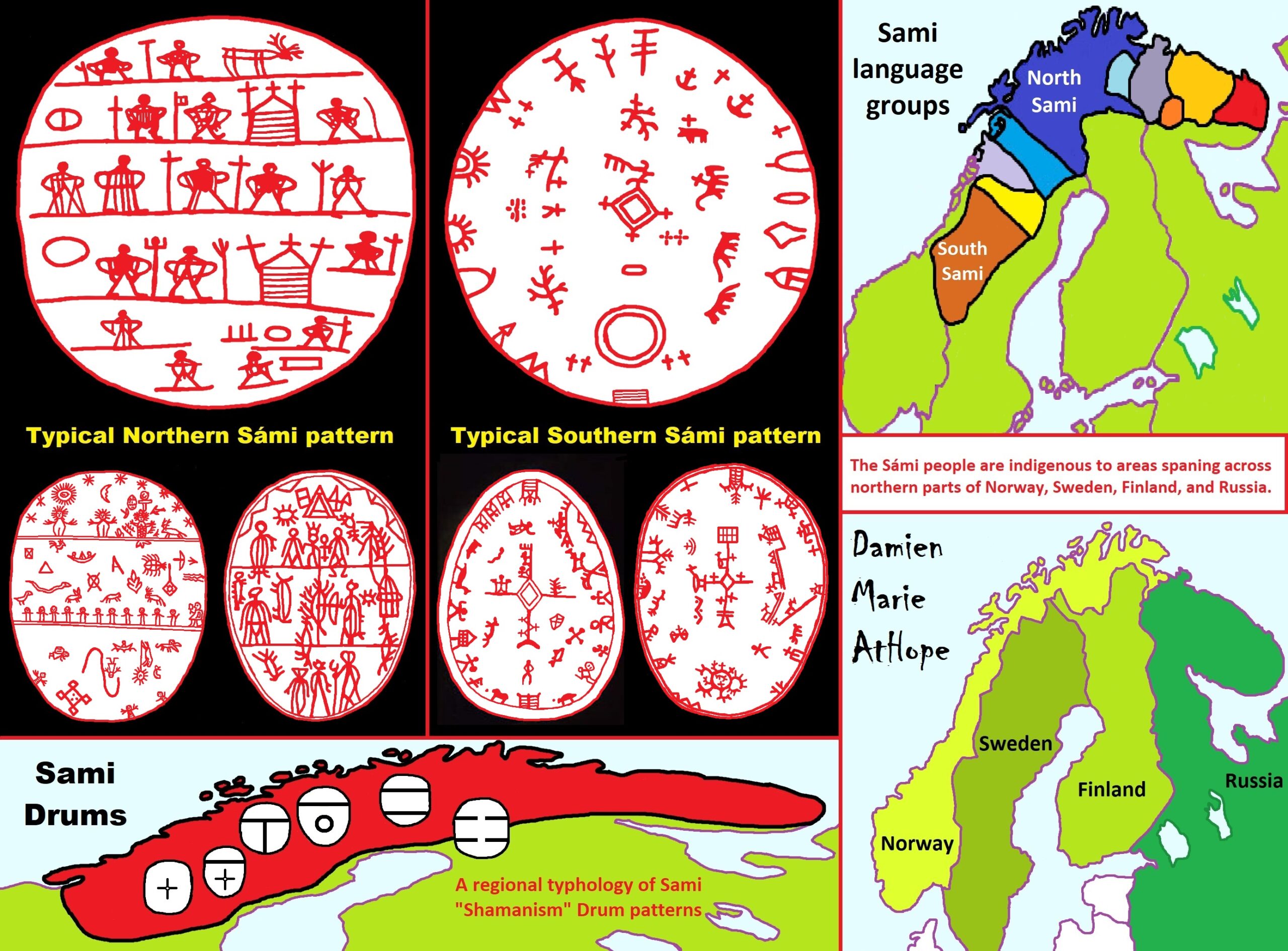

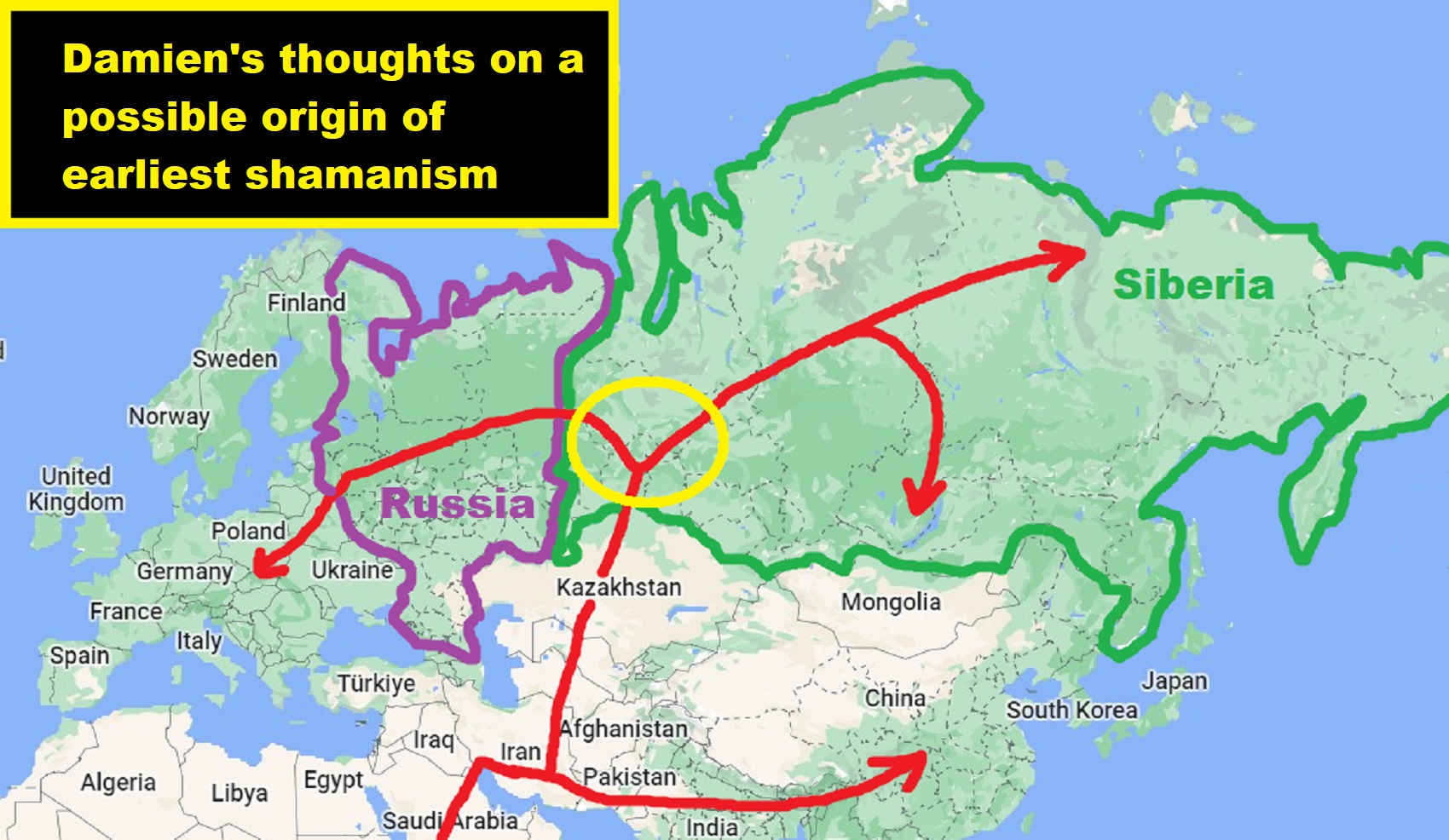

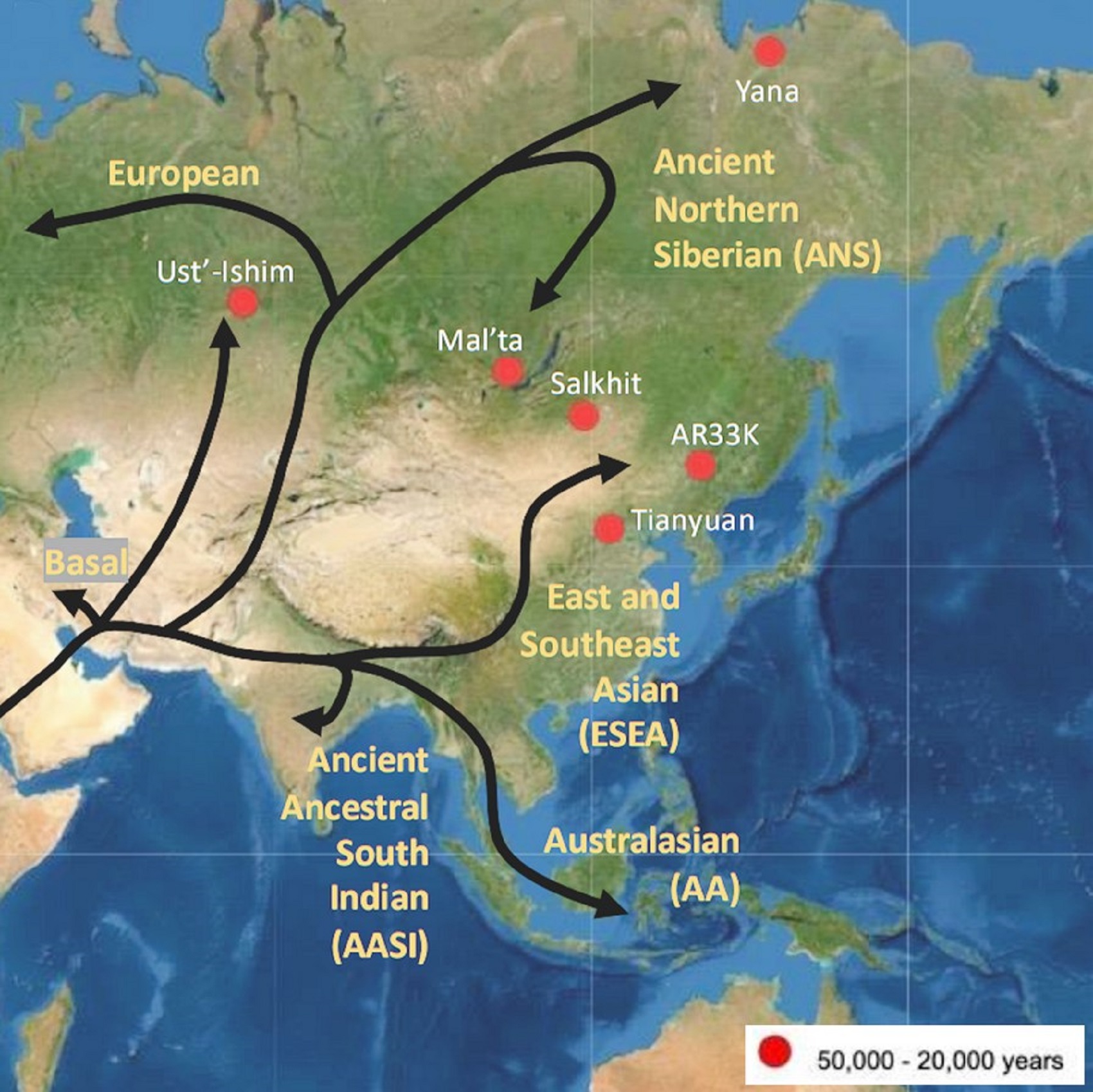

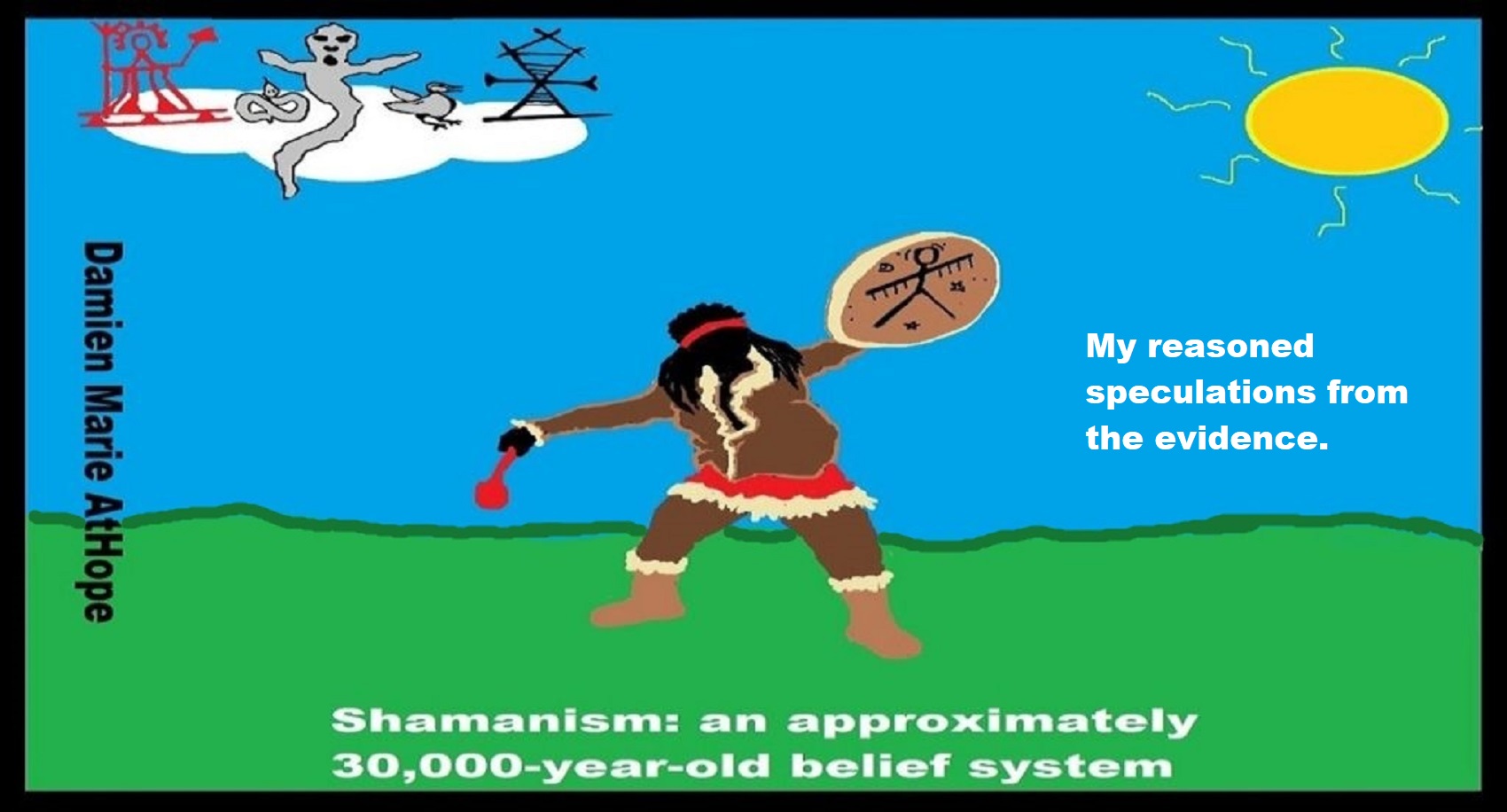

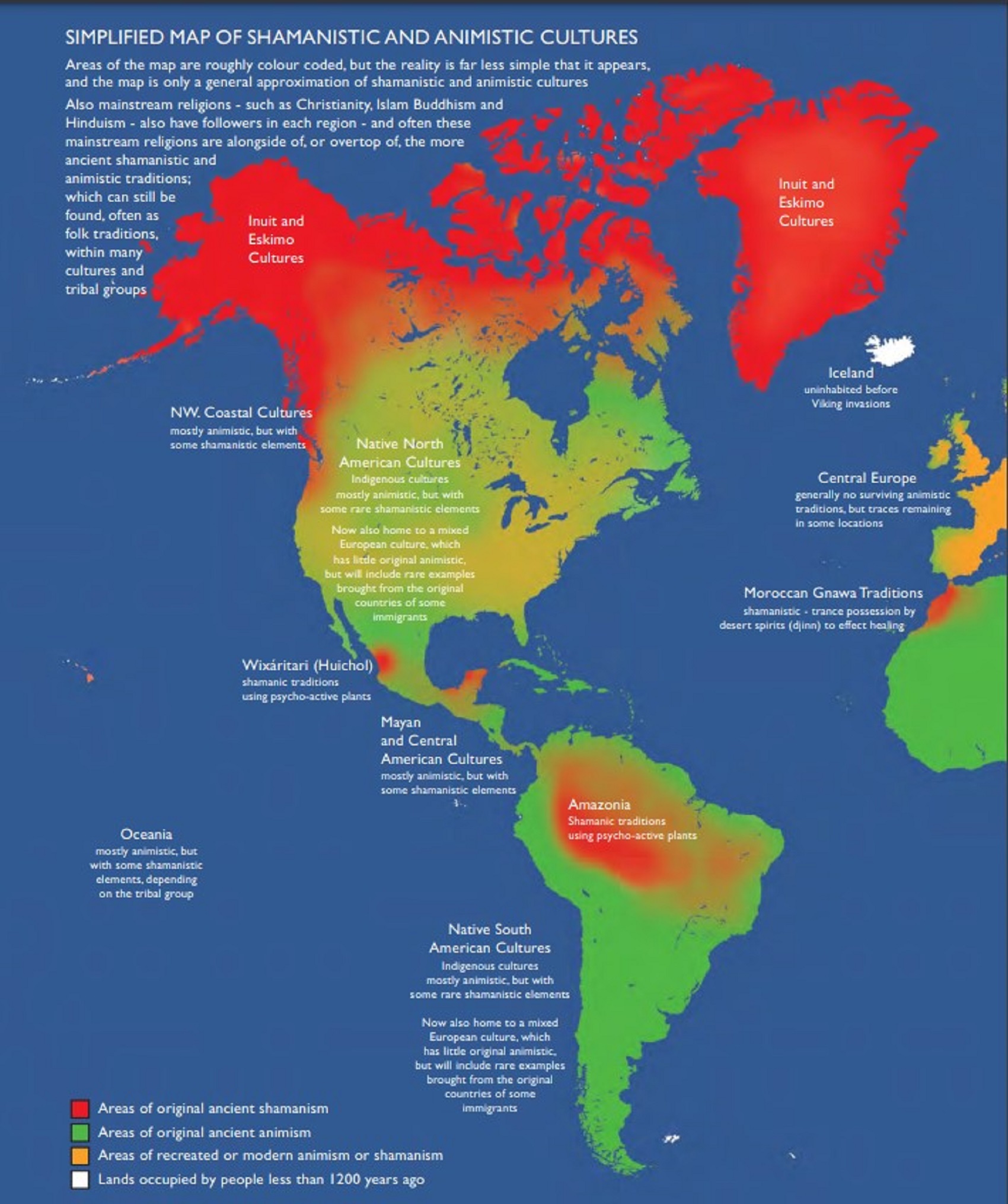

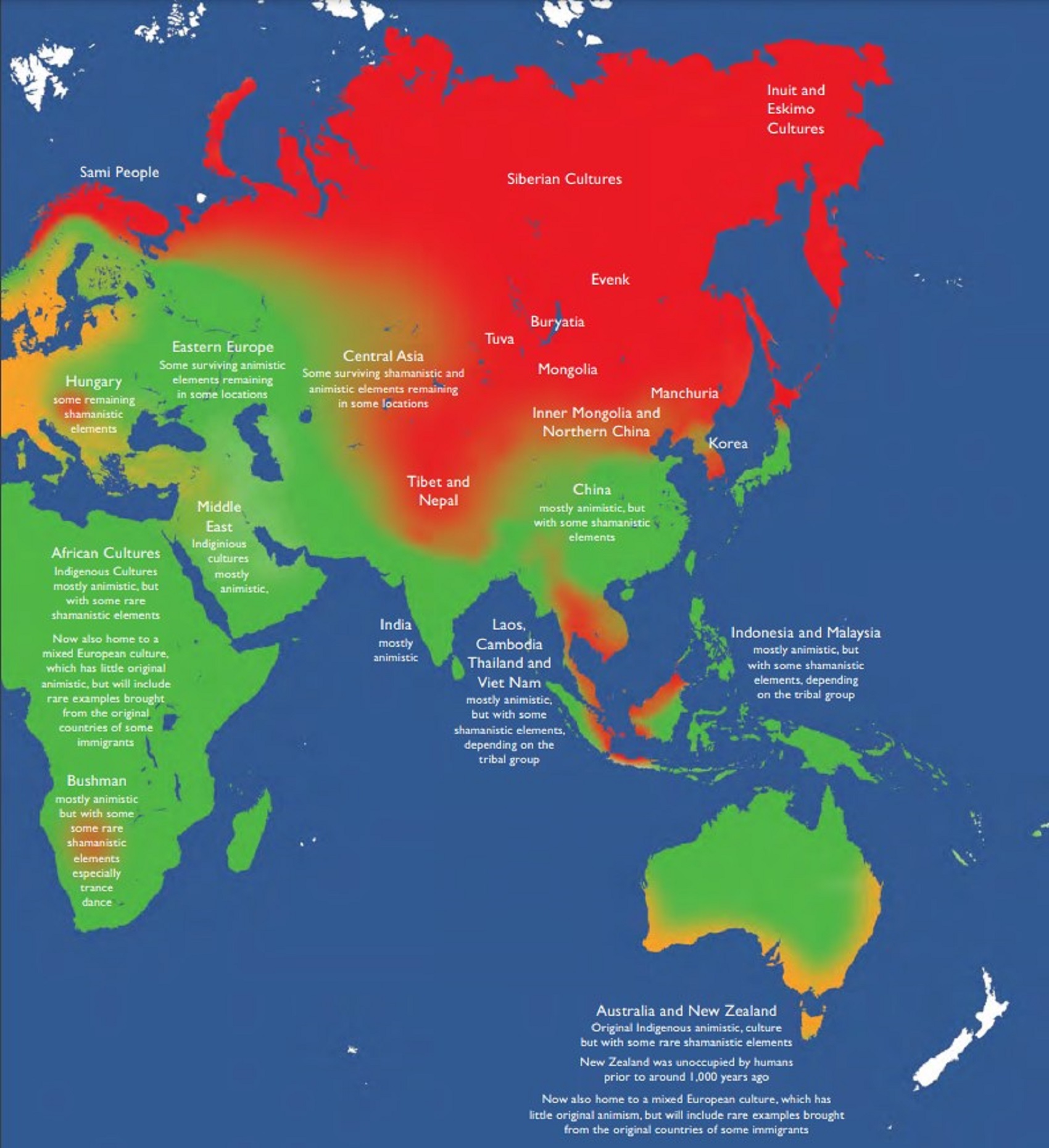

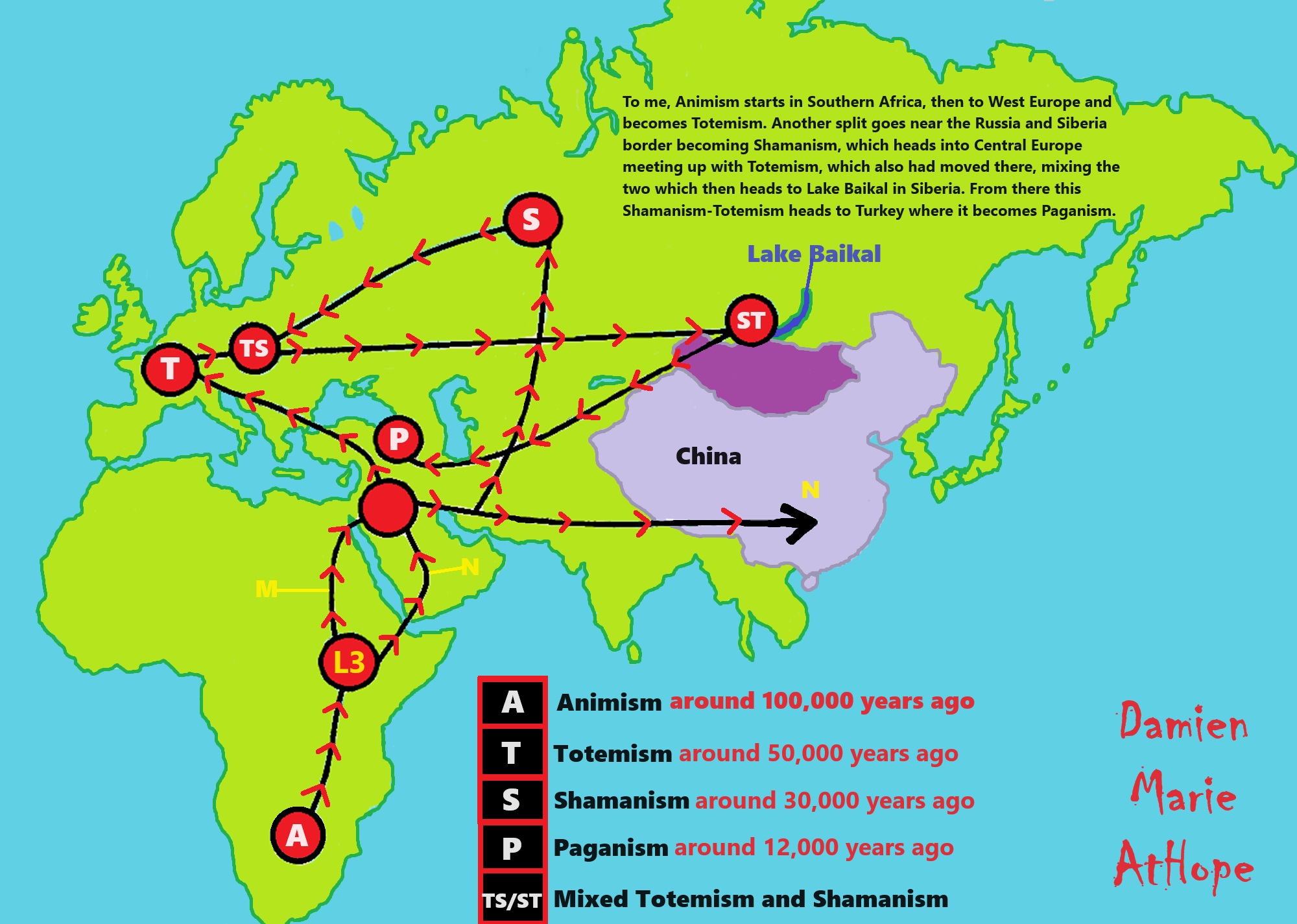

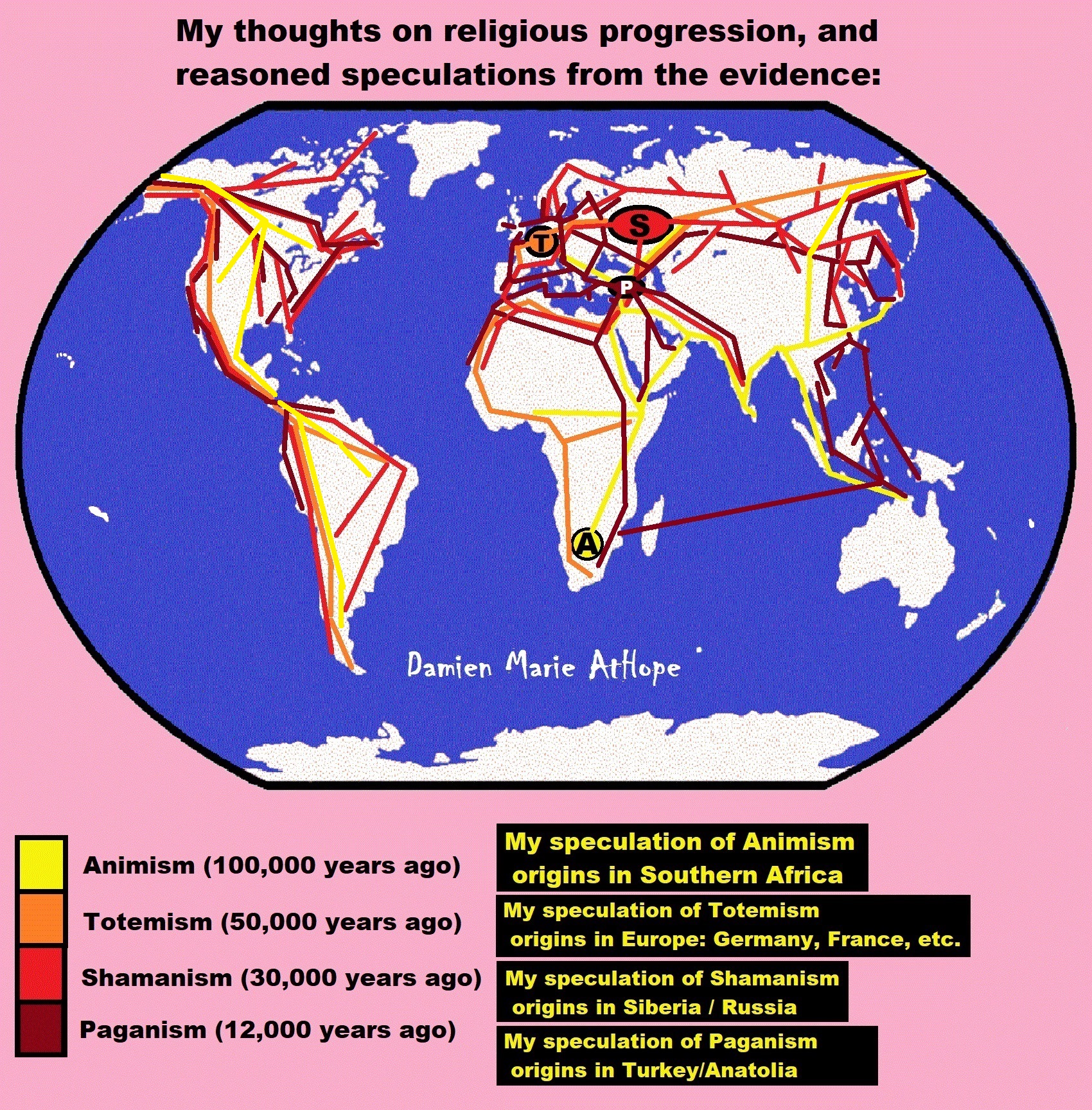

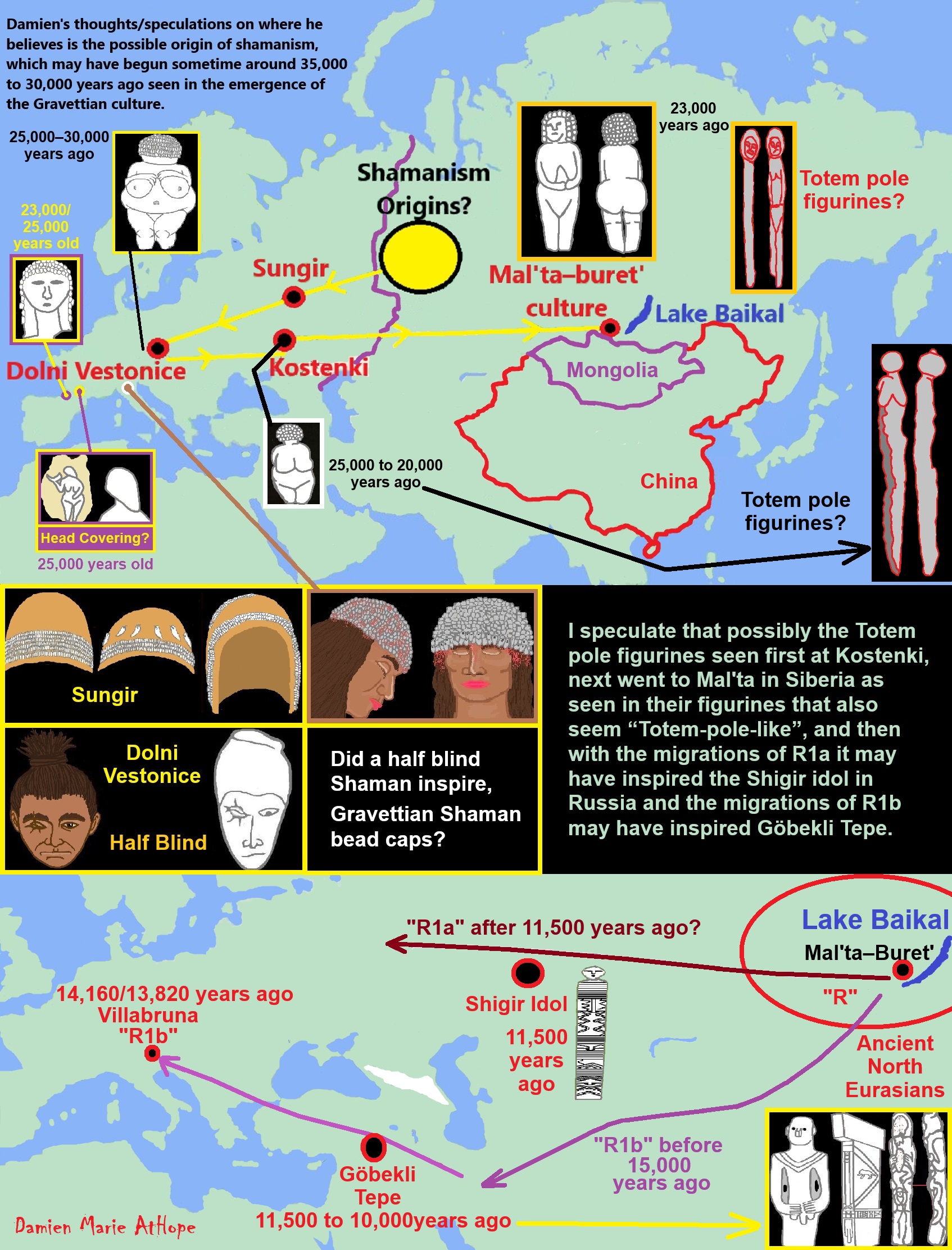

Here are Damien’s thoughts/speculations on where he believes is the possible origin of shamanism, which may have begun sometime around 35,000 to 30,000 years ago seen in the emergence of the Gravettian culture, just to outline his thinking, on what thousands of years later led to evolved Asian shamanism, in general, and thus WU shamanism as well. In both Europe-related “shamanism-possible burials” and in Gravettian mitochondrial DNA is a seeming connection to Haplogroup U. And the first believed Shaman proposed burial belonged to Eastern Gravettians/Pavlovian culture at Dolní Věstonice in southern Moravia in the Czech Republic, which is the oldest permanent human settlement that has ever been found. It is at Dolní Věstonice where approximately 27,000-25,000 years ago a seeming female shaman was buried and also there was an ivory totem portrait figure, seemingly of her.

“The Pavlovian is an Upper Paleolithic culture, a variant of the Gravettian, that existed in the region of Moravia, northern Austria, and southern Poland around 29,000–25,000 years ago. Its name is derived from the village of Pavlov, in the Pavlov Hills, next to Dolní Věstonice in southern Moravia. The culture used sophisticated stone age technology to survive in the tundra on the fringe of the ice sheets around the Last Glacial Maximum. Excavation has yielded flint implements, polished and drilled stone artifacts, bone spearheads, needles, digging tools, flutes, bone ornaments, drilled animal teeth, and seashells. Art or religious finds are bone carvings and figurines of humans and animals made of mammoth tusk, stone, and fired clay.” ref

“One of the burials, located near the huts, revealed a human female skeleton aged to 40+ years old, ritualistically placed beneath a pair of mammoth scapulae, one leaning against the other. Surprisingly, the left side of the skull was disfigured in the same manner as the aforementioned carved ivory figure, indicating that the figure was an intentional depiction of this specific individual. The bones and the earth surrounding the body contained traces of red ocher, a flint spearhead had been placed near the skull, and one hand held the body of a fox. This evidence suggests that this was the burial site of a shaman. This is the oldest site not only of ceramic figurines and artistic portraiture, but also of evidence of female shamans.” ref

“A burial of an approximately forty-year-old woman was found at Dolní Věstonice in an elaborate burial setting. Various items found with the woman have had a profound impact on the interpretation of the social hierarchy of the people at the site, as well as indicating an increased lifespan for these inhabitants. The remains were covered in red ochre, a compound known to have religious significance, indicating that this woman’s burial was ceremonial in nature. Also, the inclusion of a mammoth scapula and a fox are indicative of a high-status burial.” ref

“In the Upper Paleolithic, anatomically modern humans began living longer, often reaching middle age, by today’s standards. Rachel Caspari argues in “Human Origins: the Evolution of Grandparents,” that life expectancy increased during the Upper Paleolithic in Europe (Caspari 2011). She also describes why elderly people were highly influential in society. Grandparents assisted in childcare, perpetuated cultural transmission, and contributed to the increased complexity of stone tools (Caspari 2011). The woman found at Dolní Věstonice was old enough to have been a grandparent. Although human lifespans were increasing, elderly individuals in Upper Paleolithic societies were still relatively rare. Because of this, it is possible that the woman was attributed with great importance and wisdom, and revered because of her age. Because of her advanced age, it is also possible she had a decreased ability to care for herself, instead relying on her family group to care for her, which indicates strong social connections.” ref

“Furthermore, a female figurine was found at the site and is believed to be associated with the aged woman, because of remarkably similar facial characteristics. The woman was found to have deformities on the left side of her face. The special importance accorded with her burial, in addition to her facial deformity, makes it possible that she was a shaman in this time period, where it was “not uncommon that people with disabilities, either mental or physical, are thought to have unusual supernatural powers” (Pringle 2010).” ref

“In 1981, Patricia Rice studied a multitude of female clay figurines found at Dolní Věstonice, believed to represent fertility in this society. She challenged this assumption by analyzing all the figurines and found that, “it is womanhood, rather than motherhood that is symbolically recognized or honored” (Rice 1981: 402). This interpretation challenged the widely held assumption that all prehistoric female figurines were created to honor fertility. The fact is that we have no idea why these figurines proliferated nor of their purpose or usage.” ref

“Haplogroup U5 is estimated to be about 30,000 years old, and it is primarily found today in people with European ancestry. Both the current geographic distribution of U5 and testing of ancient human remains indicate that the ancestor of U5 expanded into Europe before 31,000 years ago. A 2013 study by Fu et al. found two U5 individuals at the Dolni Vestonice burial site in the Czech Republic that has been dated to 31,155 years ago. A third person from the same burial was identified as haplogroup U8. The Dolni Vestonice samples have only two of the five mutations ( C16192T and C16270T) that are found in the present day U5 population. This indicates that the U5-(C16192T and C16270T) mtDNA sequence is ancestral to the present day U5 population that includes the additional three mutations T3197C, G9477A and T13617C.” ref

“Haplogroup U5 is thought to have evolved in the western steppe region and then entered Europe around 30,000 to 55,000 years ago. Results support previous hypotheses that haplogroup U5 mtDNAs expanded throughout Northern, Southern, and Central Europe with more recent expansions into Western Europe and Africa. The results further allow us to explain how U5 mtDNAs are now found with high frequency in Northern Europe, as well as delineate the origins of the specific U5 subhaplogroups found in that part of Europe.” ref

“Haplogroup U5 is found throughout Europe with an average frequency ranging from 5% to 12% in most regions. U5a is most common in north-east Europe and U5b in northern Spain. Nearly half of all Sami and one fifth of Finnish maternal lineages belong to U5. Other high frequencies are observed among the Mordovians (16%), the Chuvash (14.5%) and the Tatars (10.5%) in the Volga-Ural region of Russia, the Estonians (13%), the Lithuanians (11.5%) and the Latvians in the Baltic, the Dargins (13.5%), Avars (13%) and the Chechens (10%) in the Northeast Caucasus, the Basques (12%), the Cantabrians (11%) and the Catalans (10%) in northern Spain, the Bretons (10.5%) in France, the Sardinians (10%) in Italy, the Slovaks (11%), the Croatians (10.5%), the Poles (10%), the Czechs (10%), the Ukrainians (10%) and the Slavic Russians (10%). Overall, U5 is generally found in population with high percentages of Y-haplogroups I1, I2, and R1a, three lineages already found in Mesolithic Europeans. The highest percentages are observed in populations associated predominantly with Y-haplogroup N1c1 (the Finns and the Sami), although N1c1 is originally an East Asian lineage that spread over Siberia and Northeast Europe and assimilated indigenous U5 maternal lineages.” ref

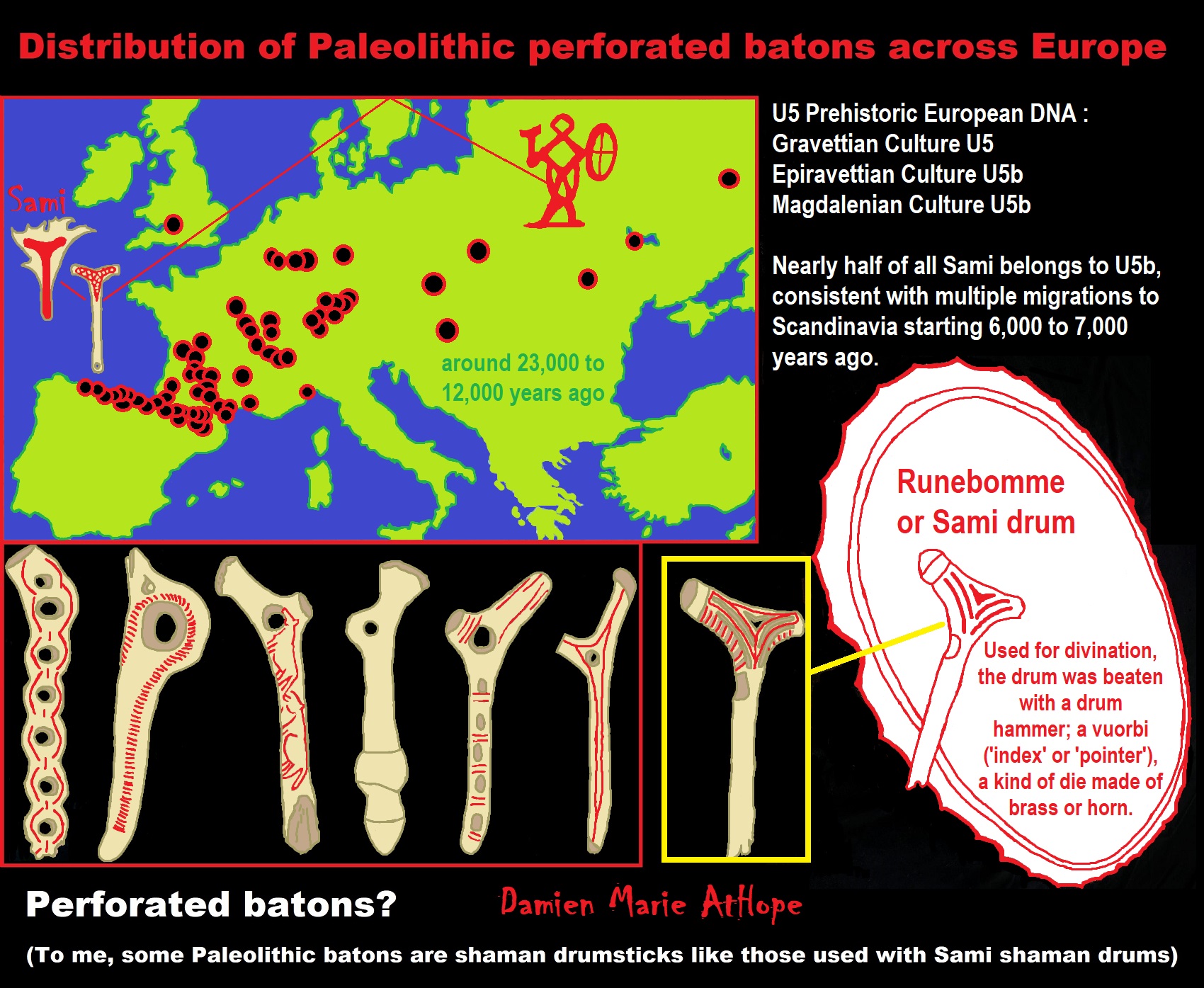

“The age of haplogroup U5 is uncertain at present. It could have arisen as recently as 35,000 years ago, or as early was 50,000 years ago. U5 appear to have been a major maternal lineage among the Paleolithic European hunter-gatherers, and even the dominant lineage during the European Mesolithic. In two papers published two months apart, Posth et al. 2016 and Fu et al. 2016 reported the results of over 70 complete human mitochondrial genomes ranging from 45,000 to 7,000 years ago. The oldest U5 samples all dated from the Gravettian culture (c. 32,000 to 22,000 years ago), while the older Aurignacian samples belonged to mt-haplogroups M, N, R*, and U2. Among the 16 Gravettian samples that yielded reliable results, six belonged to U5 – the others belonging mostly to U2, as well as isolated samples of M, U*, and U8c. Two Italian Epigravettian samples, one from the Paglicci Cave in Apulia (18,500 years ago), and another one from Villabruna in Veneto (14,000 years ago), belonged to U5b2b, as did two slightly more recent Epipaleolithic samples from the Rhône valley in France. U5b1 samples were found in Epipalaeolithic Germany, Switzerland (U5b1h in the Grotte du Bichon), and France. More 80% of the numerous Mesolithic European mtDNA tested to date belonged to various subclades of U5. Overall, it appears that U5 arrived in Europe with the Gravettian tool makers, and that it particularly prospered from the end of the glacial period (from 11,700 years ago) until the arrival of Neolithic farmers from the Near East (between 8,500 and 6,000 years ago).” ref

“Carriers of haplogroup U5 were part of the Gravettian culture, which experienced the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, 26,000 to 19,000 years ago). During this particularly harsh period, Gravettian people would have retreated into refugia in southern Europe, from which they would have re-expanded to colonise the northern half of the continent during the Late Glacial and postglacial periods. For reasons that are yet unknown, haplogroup U5 seems to have resisted better to the LGM to other Paleolithic haplogroups like U*, U2 and U8. Mitochondrial DNA being essential for energy production, it could be that the mutations selected in early U5 subclades (U5a1, U5a2, U5b1, U5b2) conferred an advantage for survival during the coldest millennia of the LGM, which had for effect to prune less energy efficient mtDNA lineages.” ref

“It is likely that U5a and U5b lineages already existed prior to the LGM and they were geographically scattered to some extent around Europe before the growing ice sheet forced people into the refugia. Nonetheless, founder effects among the populations of each LGM refugium would have amplified the regional division between U5b and U5a. U5b would have been found at a much higher frequency in the Franco-Cantabrian region. We can deduce this from the fact that modern Western Europeans have considerably more U5b than U5a, but also because the modern Basques and Cantabrians possess almost exclusively U5b lineages. What’s more, all the Mesolithic U5 samples from Iberia whose subclade could be identified belonged to U5b.” ref

“Conversely, only U5a lineages have been found so far in Mesolithic Russia (U5a1) and Sweden (U5a1 and U5a2), which points at an eastern origin of this subclade. Mesolithic samples from Poland, Germany and Italy yielded both U5a and U5b subclades. German samples included U5a2a, U5a2c3, U5b2 and U5b2a2. The same observations are valid for the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods too, with U5a1 being found in Russia and Ukraine, U5b in France (Cardium Pottery and Megalithic), U5b2 in Portugal. U5b1b1 arose approximately 10,000 years ago, over two millennia after the end of the Last Glaciation, when the Neolithic Revolution was already under way in the Near East. Despite this relatively young age, U5b1b1 is found scattered across all Europe and well beyond its boundaries. The Saami, who live in the far European North and have 48% of U5 and 42% of V lineages, belong exclusively to the U5b1b1 subclade. Amazingly, the Berbers of Northwest Africa also possess that U5b1b1 subclade and haplogroup V.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Here are my thoughts/speculations on where I believe is the possible origin of shamanism, which may have begun sometime around 35,000 to 30,000 years ago seen in the emergence of the Gravettian culture, just to outline his thinking, on what thousands of years later led to evolved Asian shamanism, in general, and thus WU shamanism as well. In both Europe-related “shamanism-possible burials” and in Gravettian mitochondrial DNA is a seeming connection to Haplogroup U. And the first believed Shaman proposed burial belonged to Eastern Gravettians/Pavlovian culture at Dolní Věstonice in southern Moravia in the Czech Republic, which is the oldest permanent human settlement that has ever been found. It is at Dolní Věstonice where approximately 27,000-25,000 years ago a seeming female shaman was buried and also there was an ivory totem portrait figure, seemingly of her.

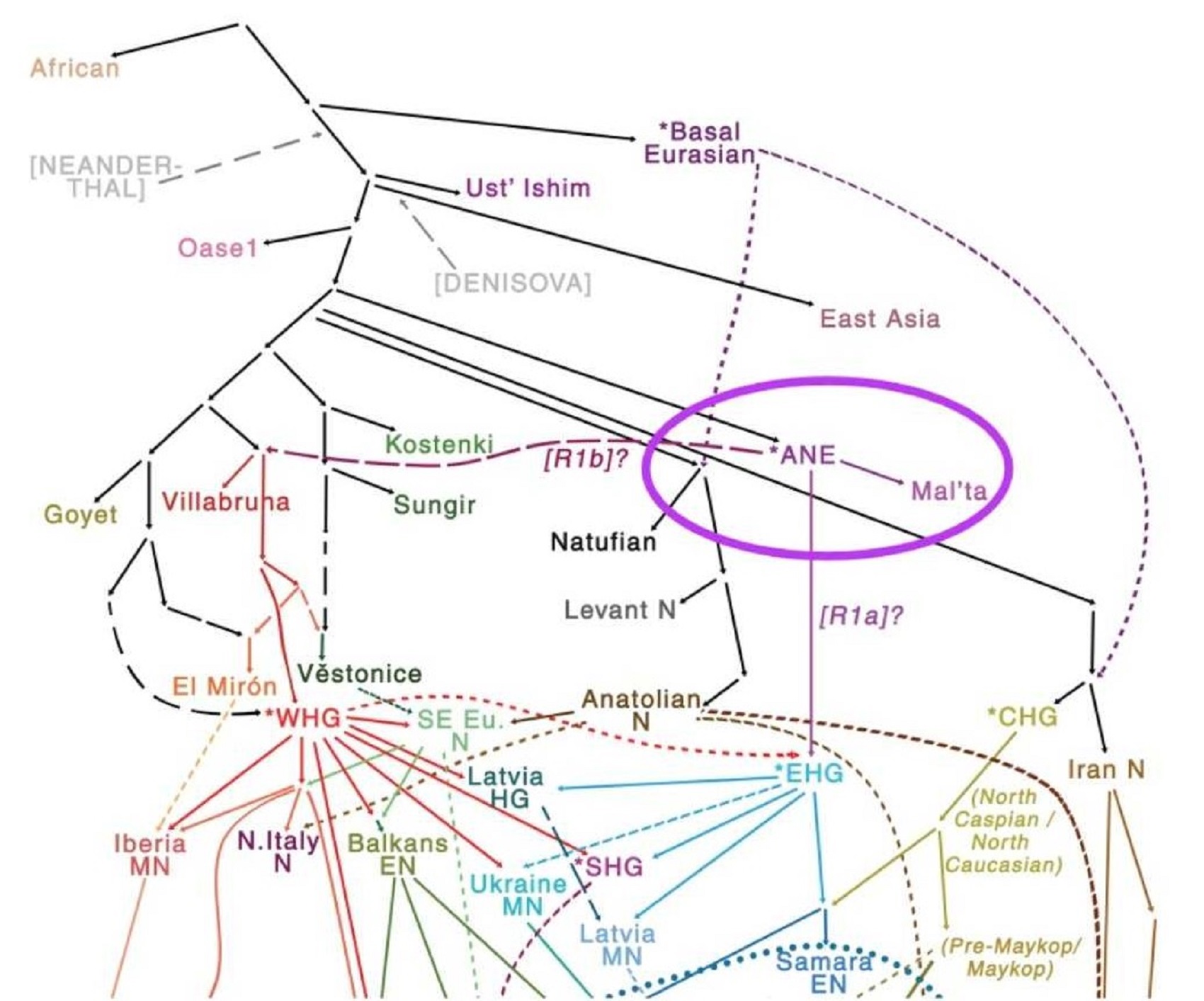

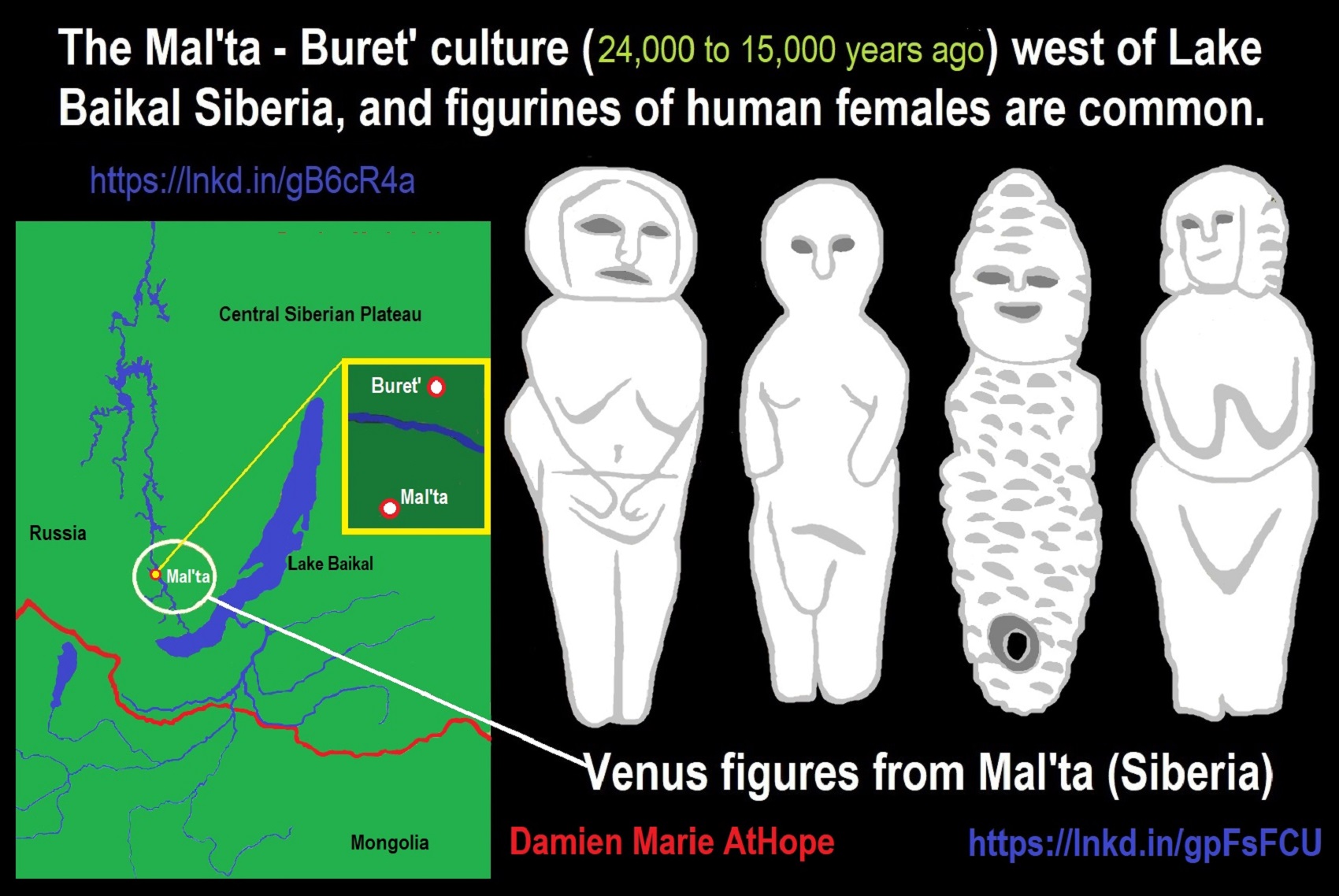

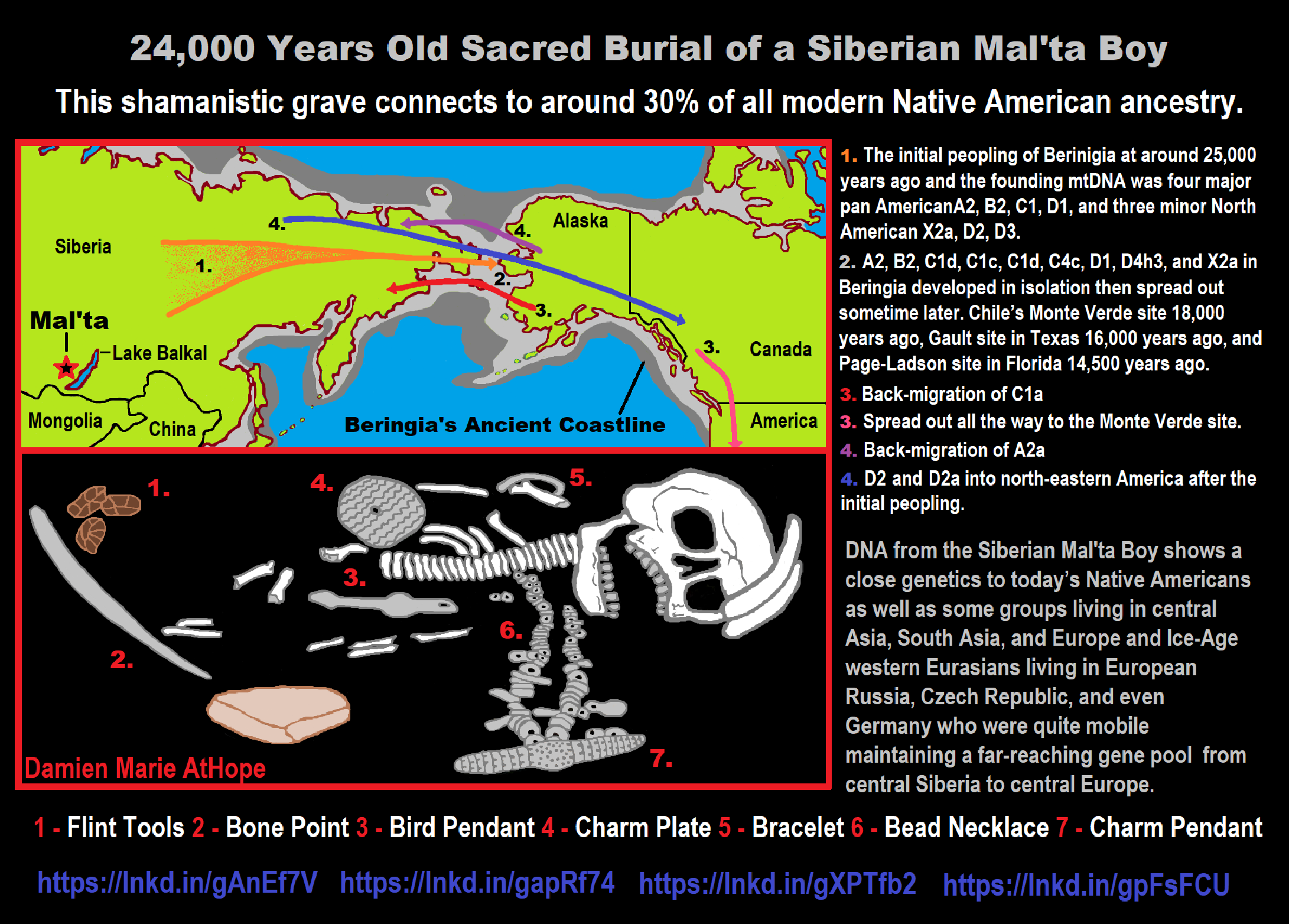

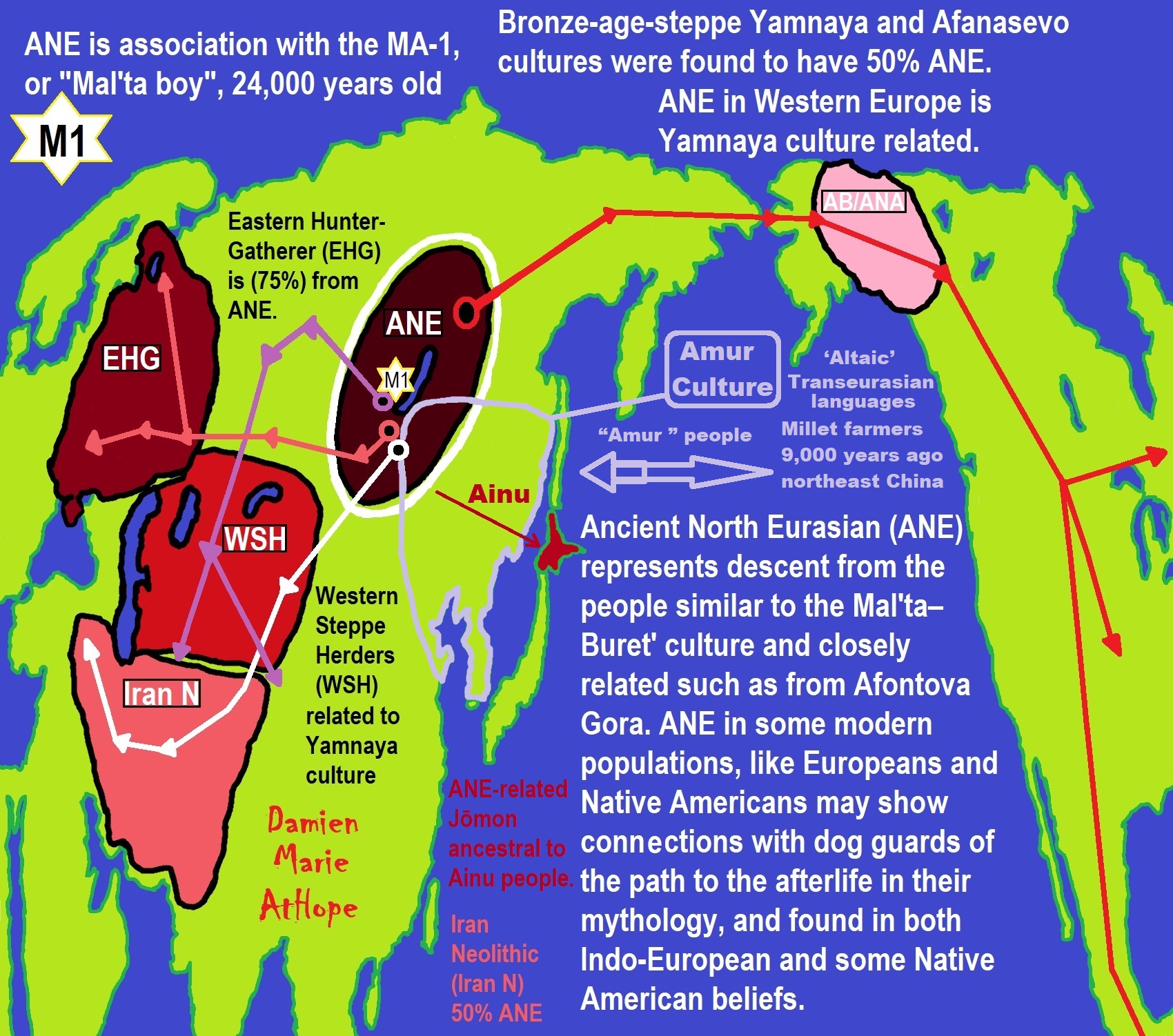

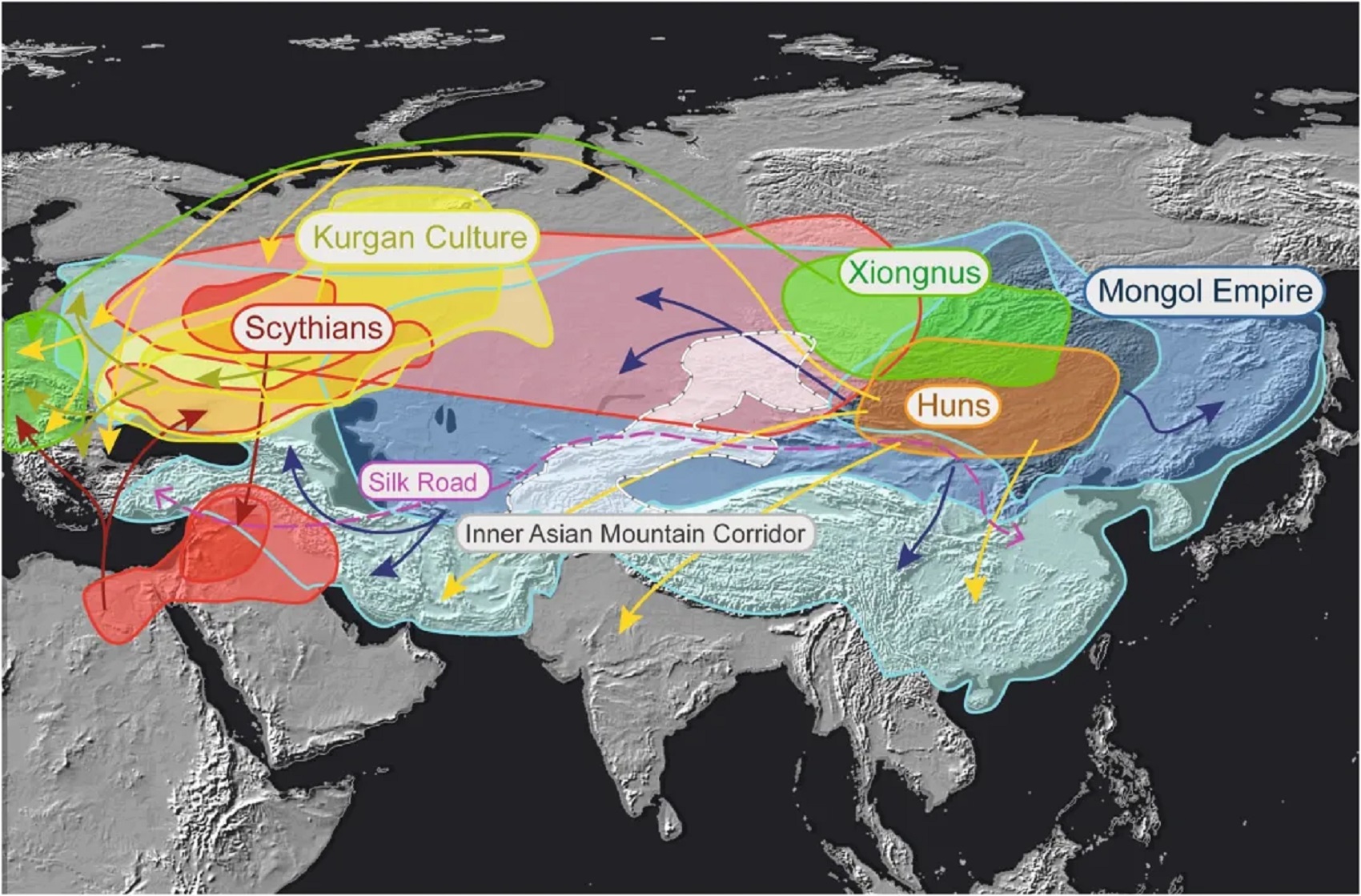

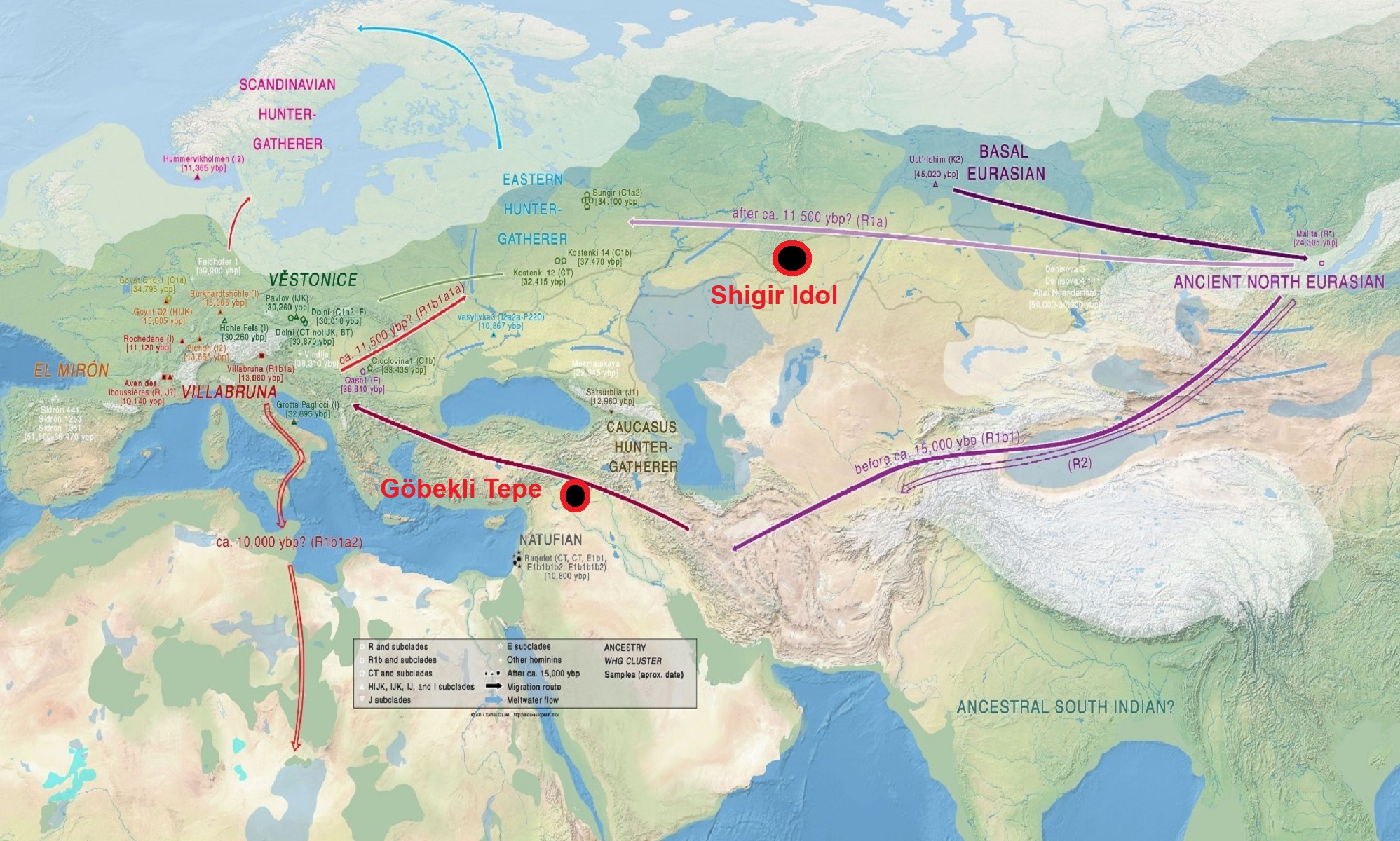

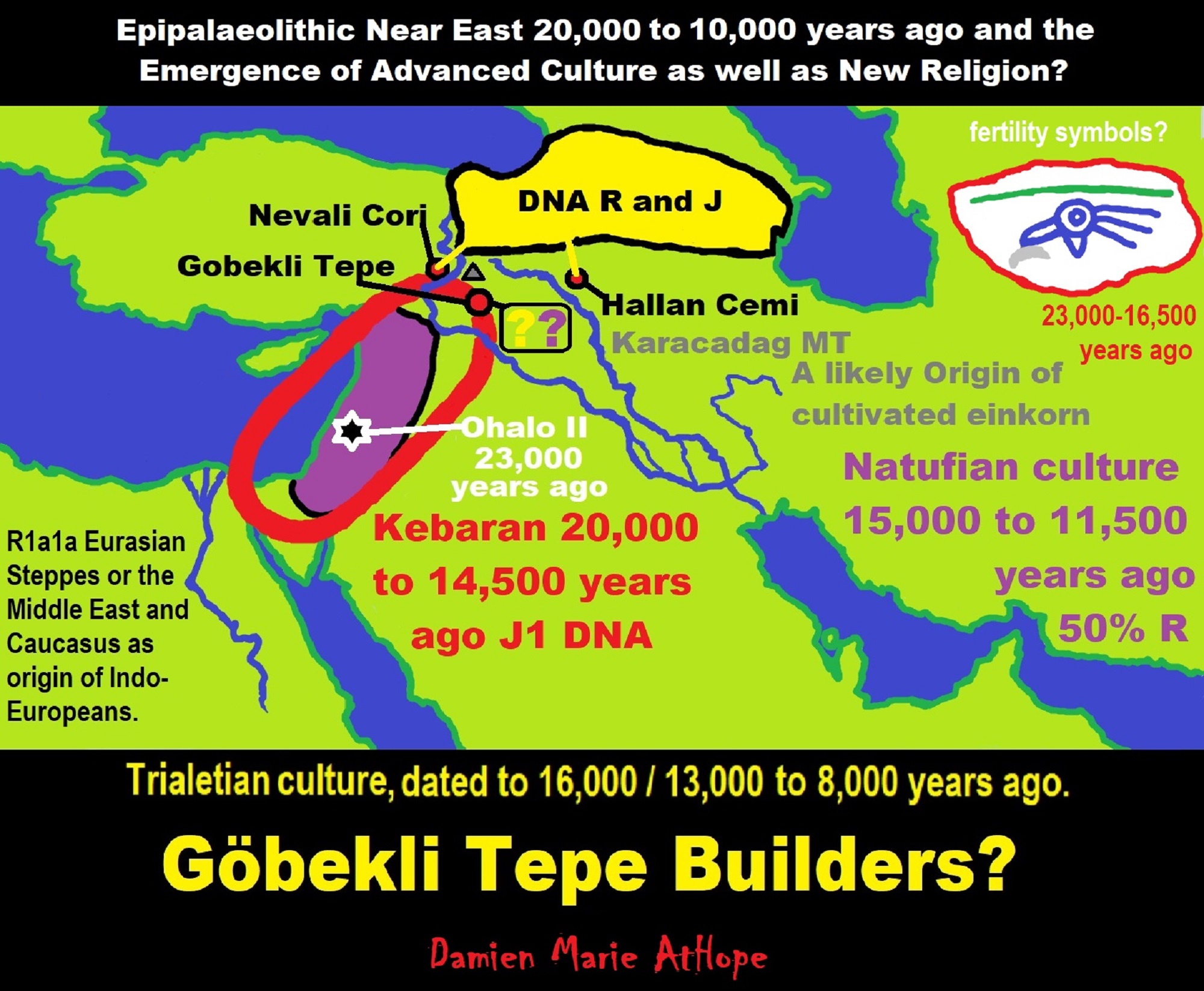

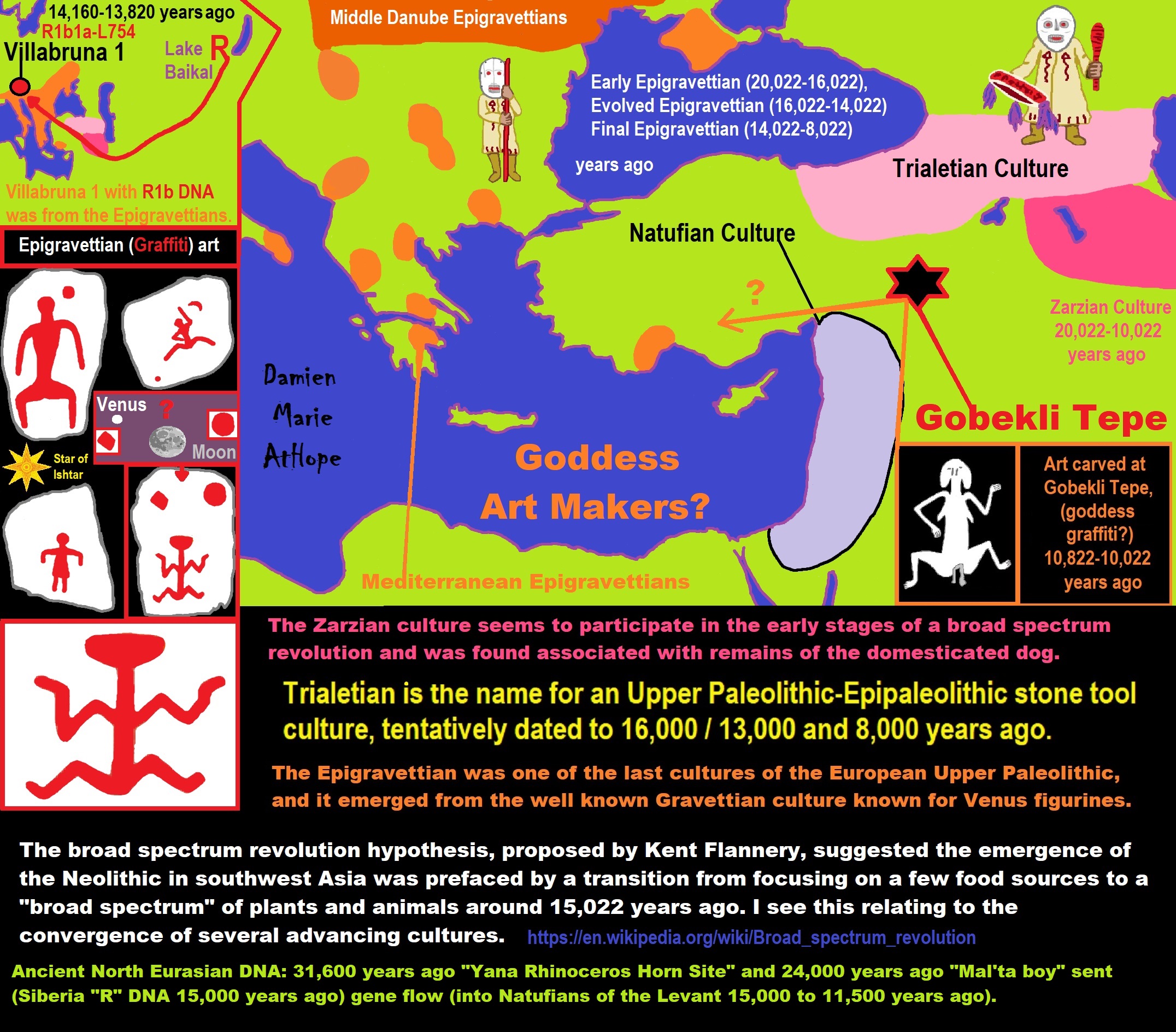

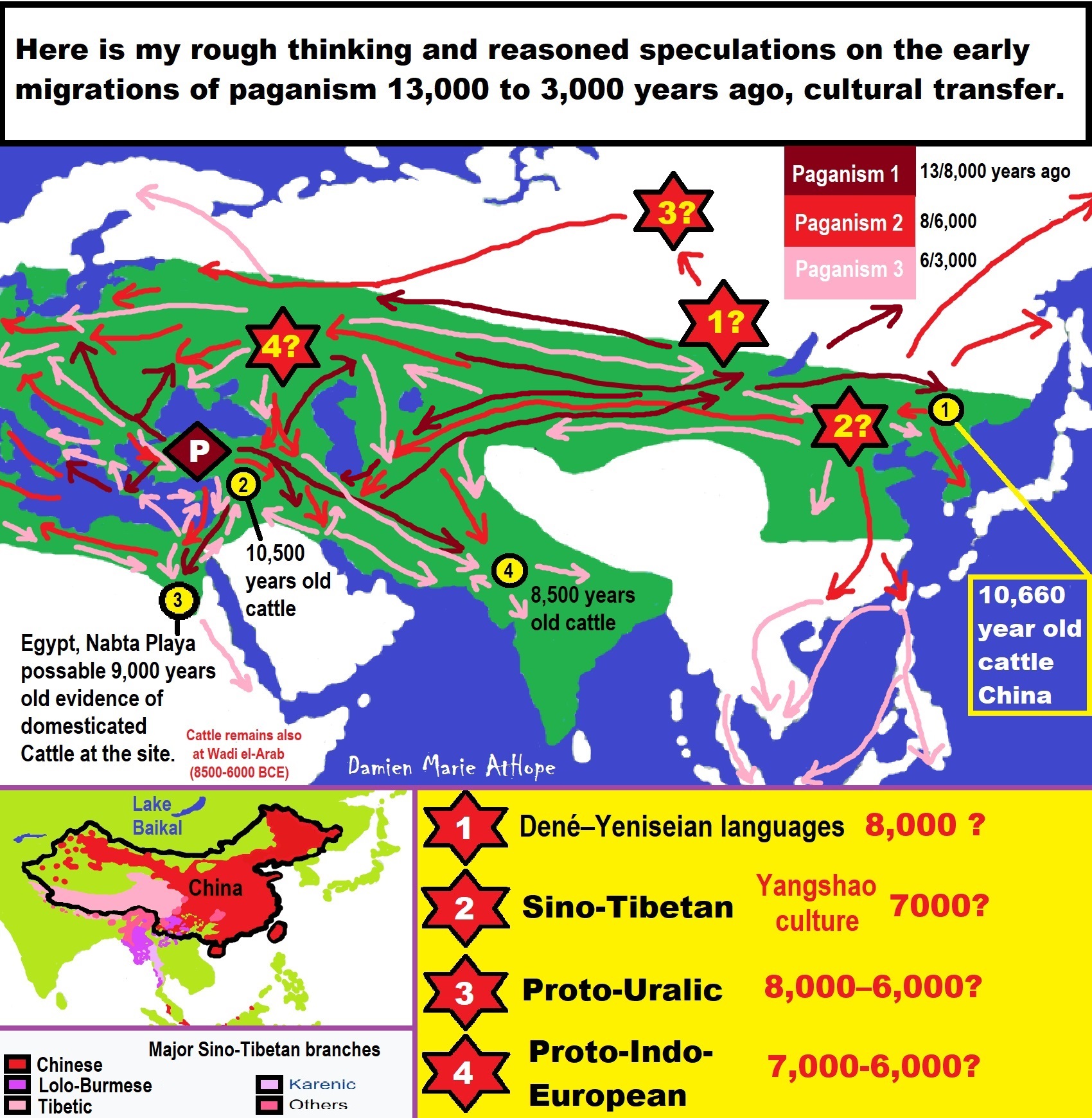

And my thoughts on how cultural/ritual aspects were influenced in the area of Göbekli Tepe. I think it relates to a few different cultures starting in the area before the Neolithic. Two different groups of Siberians first from northwest Siberia with U6 haplogroup 40,000 to 30,000 or so. Then R Haplogroup (mainly haplogroup R1b but also some possible R1a both related to the Ancient North Eurasians). This second group added its “R1b” DNA of around 50% to the two cultures Natufian and Trialetian. To me, it is likely both of these cultures helped create Göbekli Tepe. Then I think the female art or graffiti seen at Göbekli Tepe to me possibly relates to the Epigravettians that made it into Turkey and have similar art in North Italy. I speculate that possibly the Totem pole figurines seen first at Kostenki, next went to Mal’ta in Siberia as seen in their figurines that also seem “Totem-pole-like”, and then with the migrations of R1a it may have inspired the Shigir idol in Russia and the migrations of R1b may have inspired Göbekli Tepe.

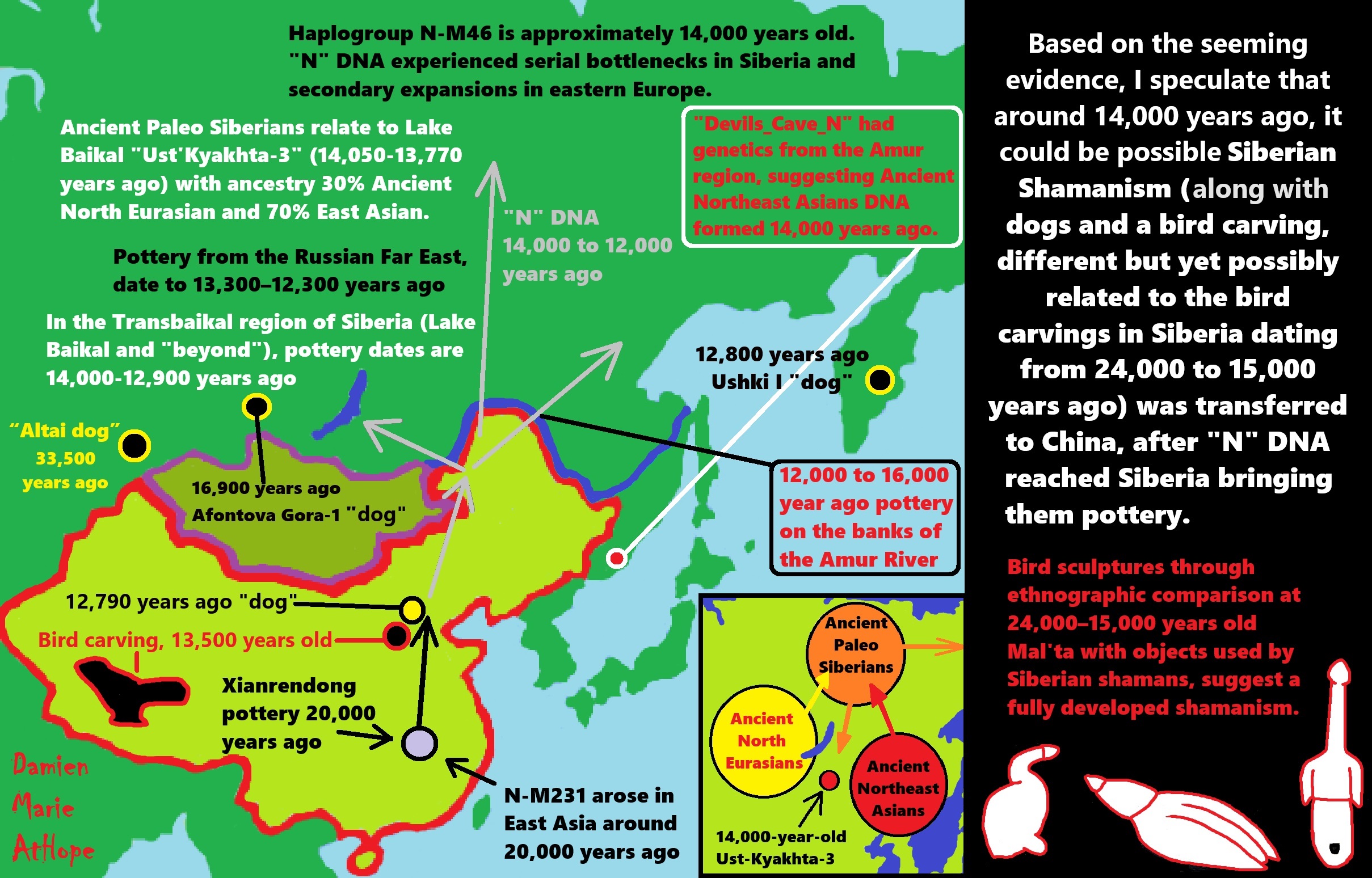

“Migration from Siberia behind the formation of Göbeklitepe: Expert states. People who migrated from Siberia formed the Göbeklitepe, and those in Göbeklitepe migrated in five other ways to spread to the world, said experts about the 12,000-year-old Neolithic archaeological site in the southwestern province of Şanlıurfa.“ The upper paleolithic migrations between Siberia and the Near East is a process that has been confirmed by material culture documents,” he said.” ref

“Semih Güneri, a retired professor from Caucasia and Central Asia Archaeology Research Center of Dokuz Eylül University, and his colleague, Professor Ekaterine Lipnina, presented the Siberia-Göbeklitepe hypothesis they have developed in recent years at the congress held in Istanbul between June 11 and 13. There was a migration that started from Siberia 30,000 years ago and spread to all of Asia and then to Eastern and Northern Europe, Güneri said at the international congress.” ref

“The relationship of Göbeklitepe high culture with the carriers of Siberian microblade stone tool technology is no longer a secret,” he said while emphasizing that the most important branch of the migrations extended to the Near East. “The results of the genetic analyzes of Iraq’s Zagros region confirm the traces of the Siberian/North Asian indigenous people, who arrived at Zagros via the Central Asian mountainous corridor and met with the Göbeklitepe culture via Northern Iraq,” he added.” ref

“Emphasizing that the stone tool technology was transported approximately 7,000 kilometers from east to west, he said, “It is not clear whether this technology is transmitted directly to long distances by people speaking the Turkish language at the earliest, or it travels this long-distance through using way stations.” According to the archaeological documents, it is known that the Siberian people had reached the Zagros region, he said. “There seems to be a relationship between Siberian hunter-gatherers and native Zagros hunter-gatherers,” Güneri said, adding that the results of genetic studies show that Siberian people reached as far as the Zagros.” ref

“There were three waves of migration of Turkish tribes from the Southern Siberia to Europe,” said Osman Karatay, a professor from Ege University. He added that most of the groups in the third wave, which took place between 2600-2400 BCE, assimilated and entered the Germanic tribes and that there was a genetic kinship between their tribes and the Turks. The professor also pointed out that there are indications that there is a technology and tool transfer from Siberia to the Göbeklitepe region and that it is not known whether people came, and if any, whether they were Turkish.” ref

“Around 12,000 years ago, there would be no ‘Turks’ as we know it today. However, there may have been tribes that we could call our ‘common ancestors,’” he added. “Talking about 30,000 years ago, it is impossible to identify and classify nations in today’s terms,” said Murat Öztürk, associate professor from İnönü University. He also said that it is not possible to determine who came to where during the migrations that were accepted to have been made thousands of years ago from Siberia. On the other hand, Mehmet Özdoğan, an academic from Istanbul University, has an idea of where “the people of Göbeklitepe migrated to.” ref