“Shaman Wearing a Jaguar Pelt”

Photo credits for the second Pic come from an Ecuadorian book about Valdivia.

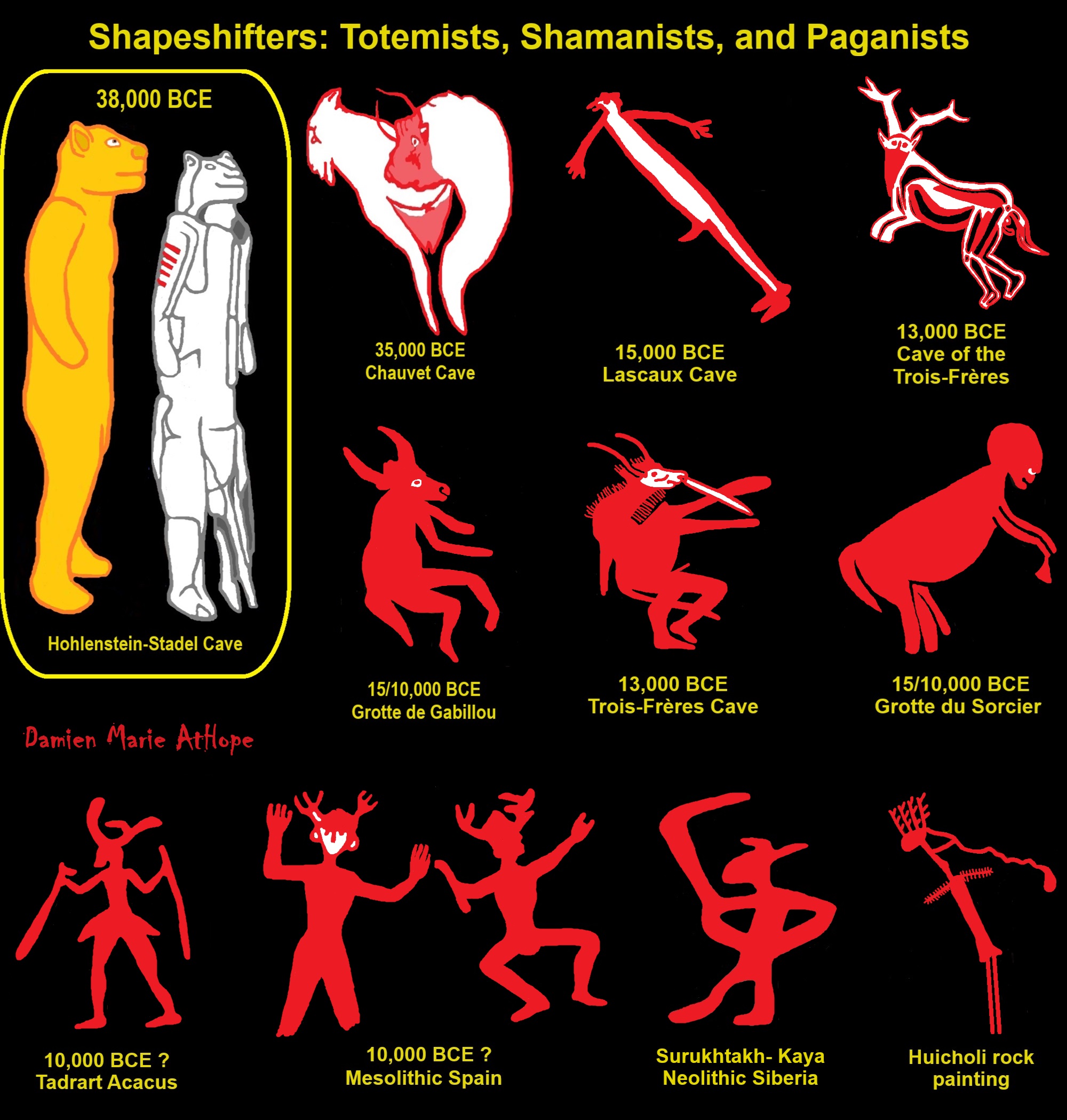

shape-shift·er: one that seems able to change form or identity at will. especially: a mythical figure that can assume different forms (as of animals) ref

Shapeshifting

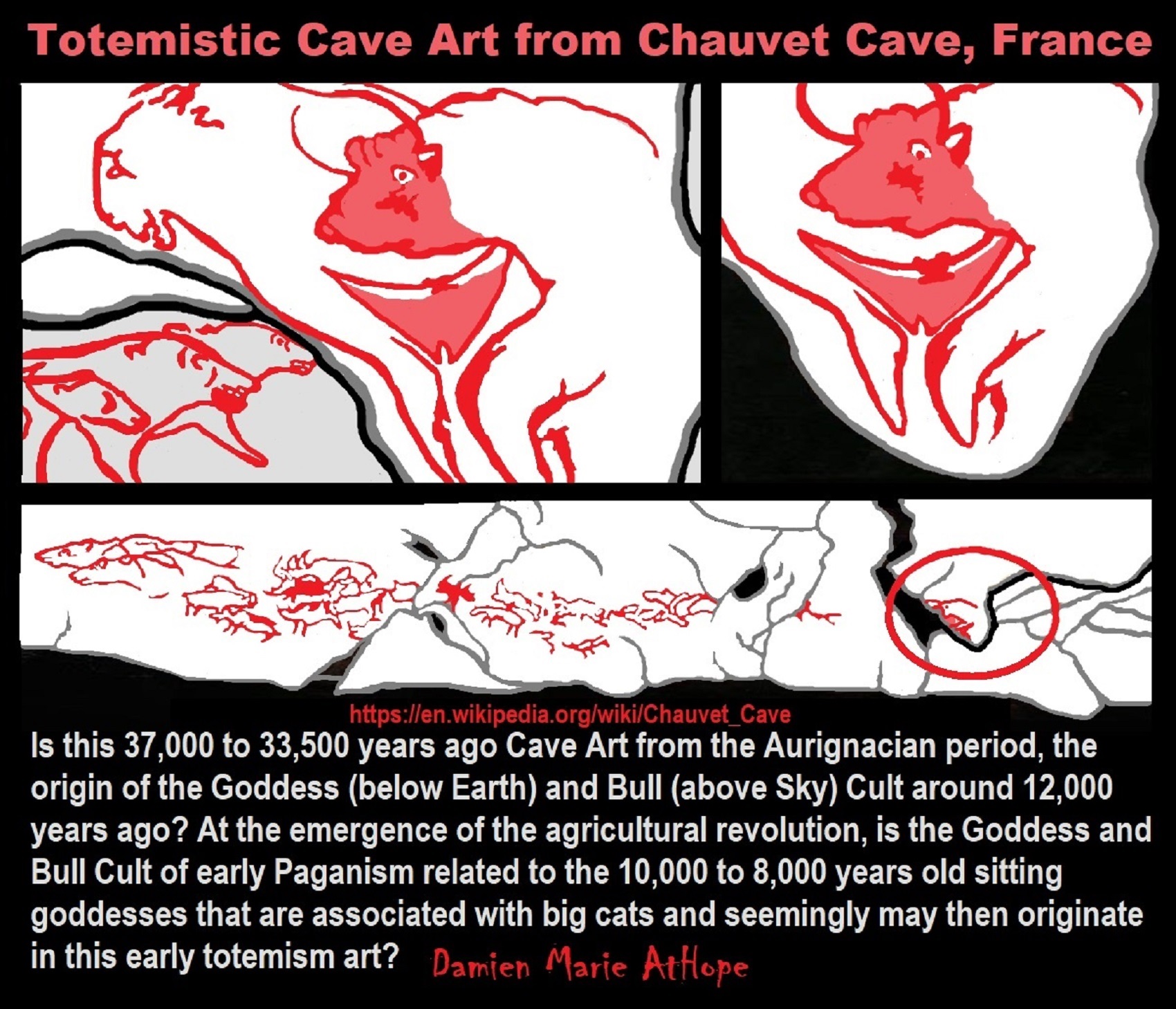

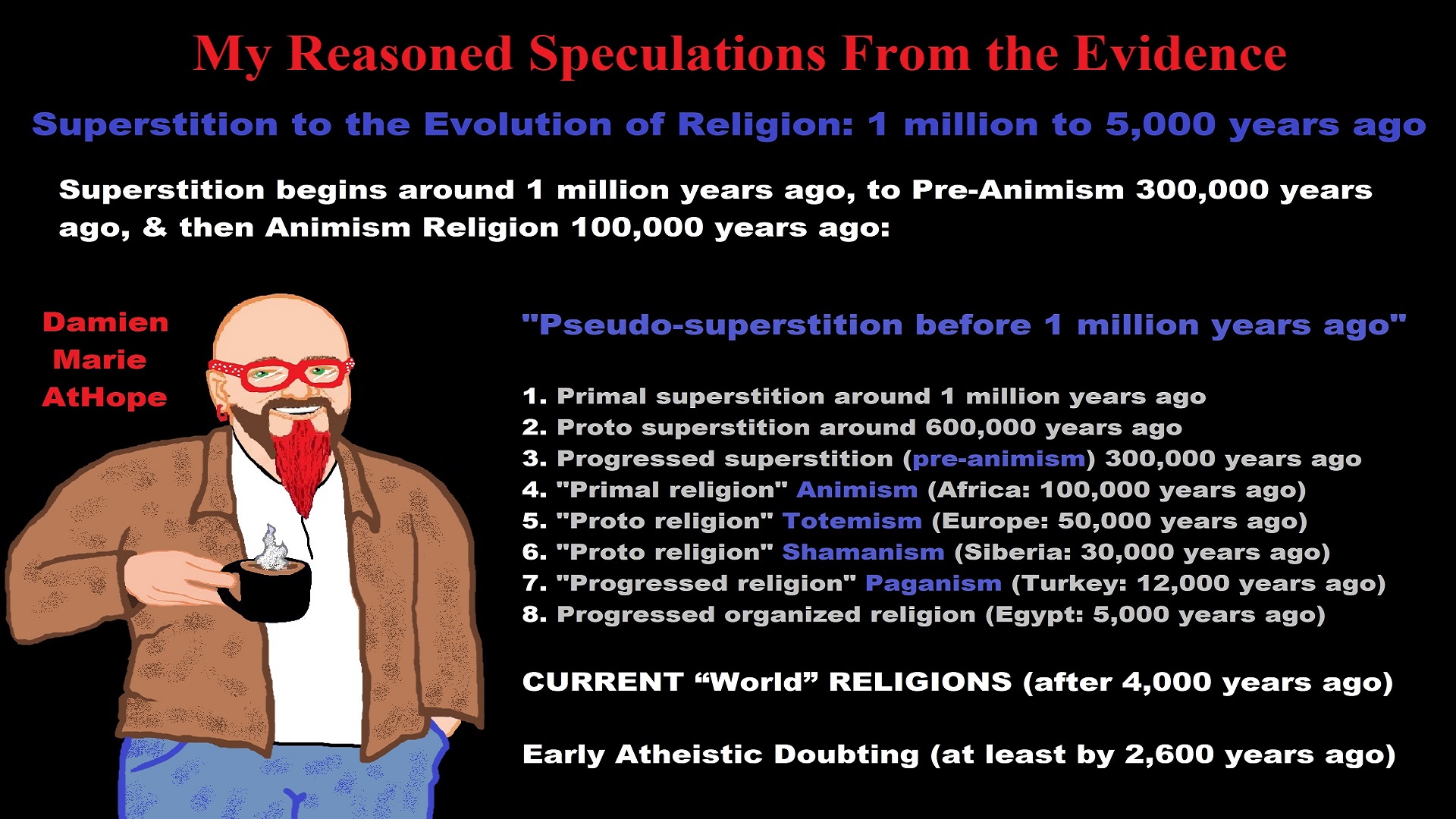

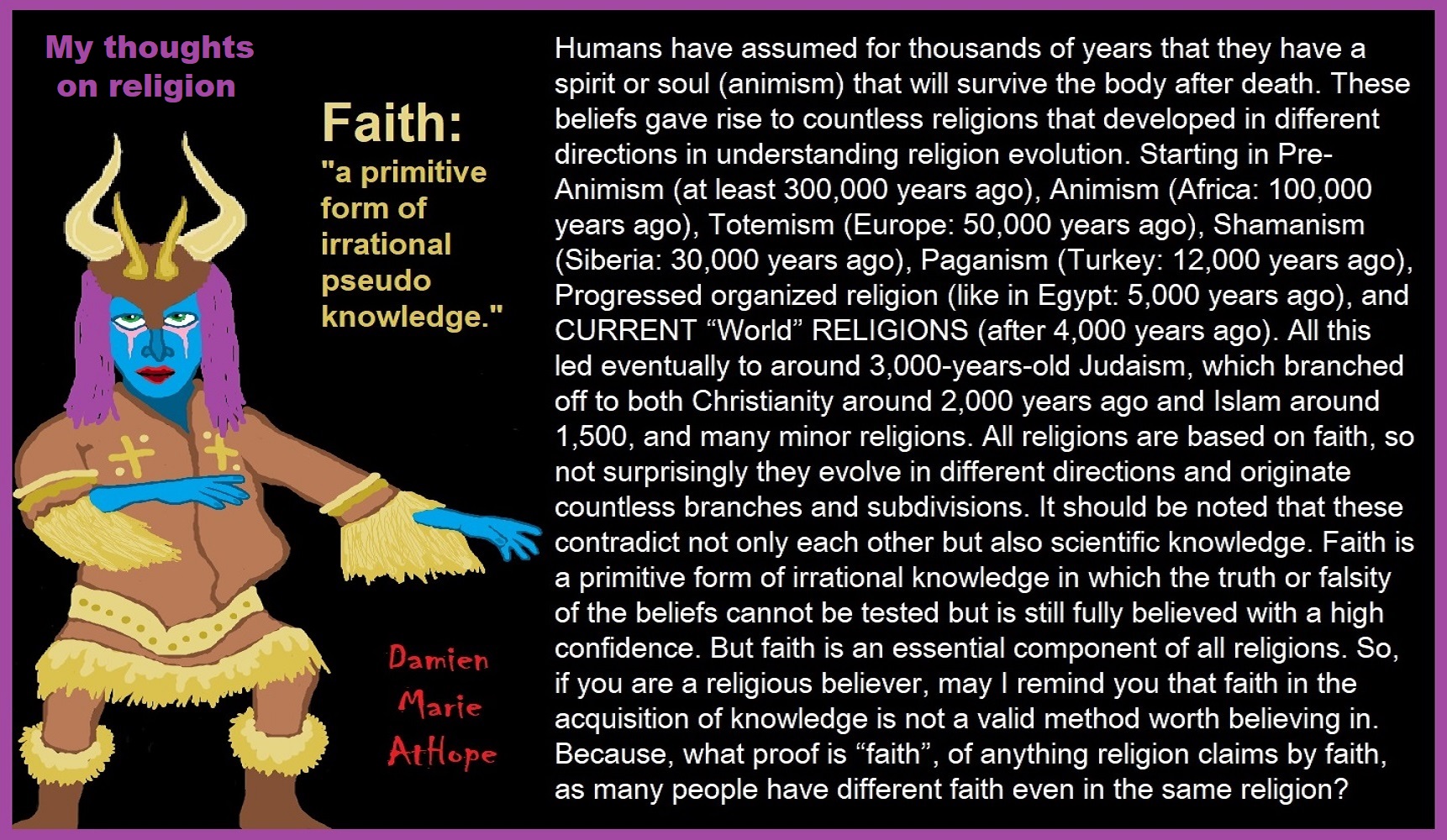

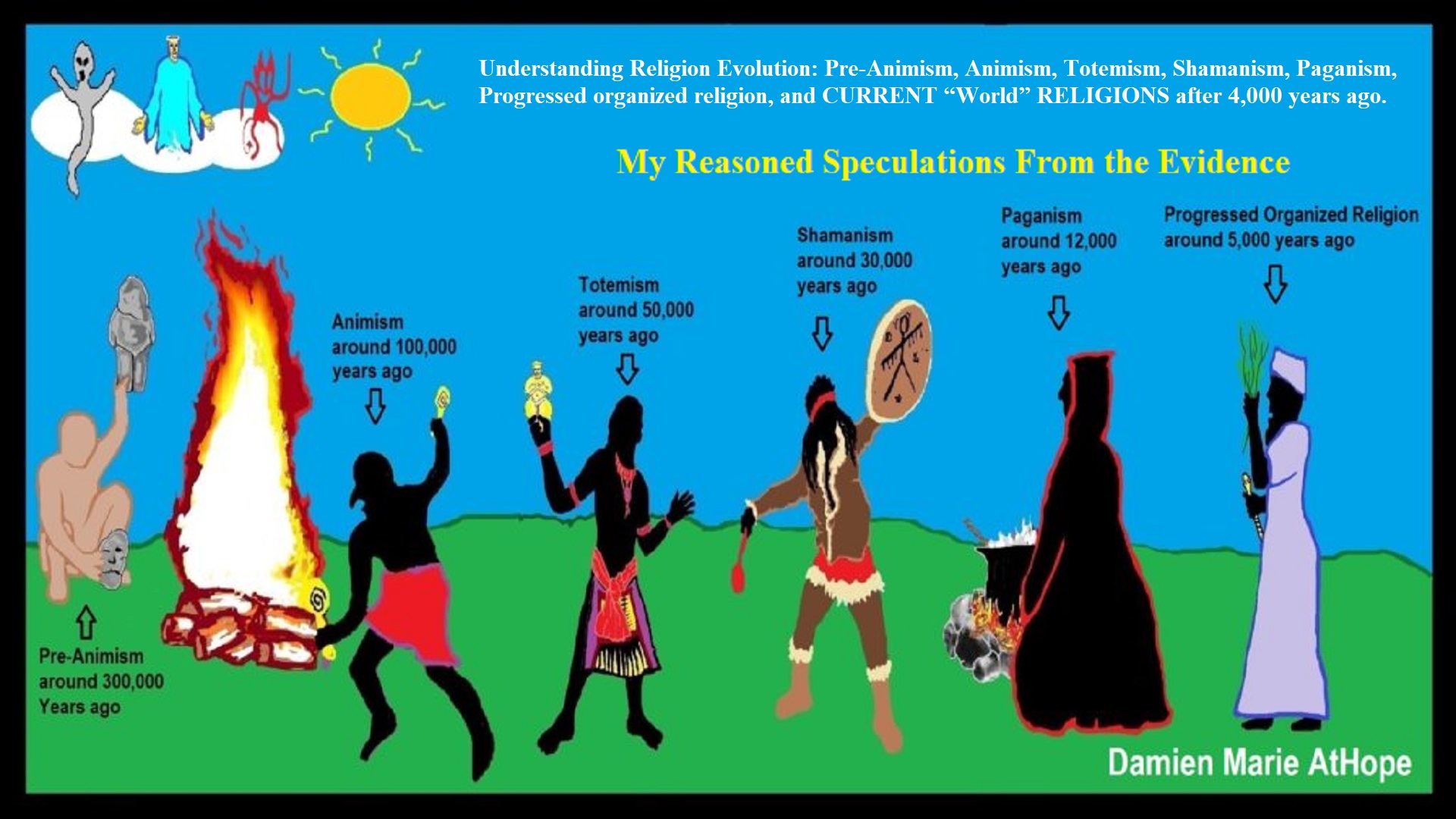

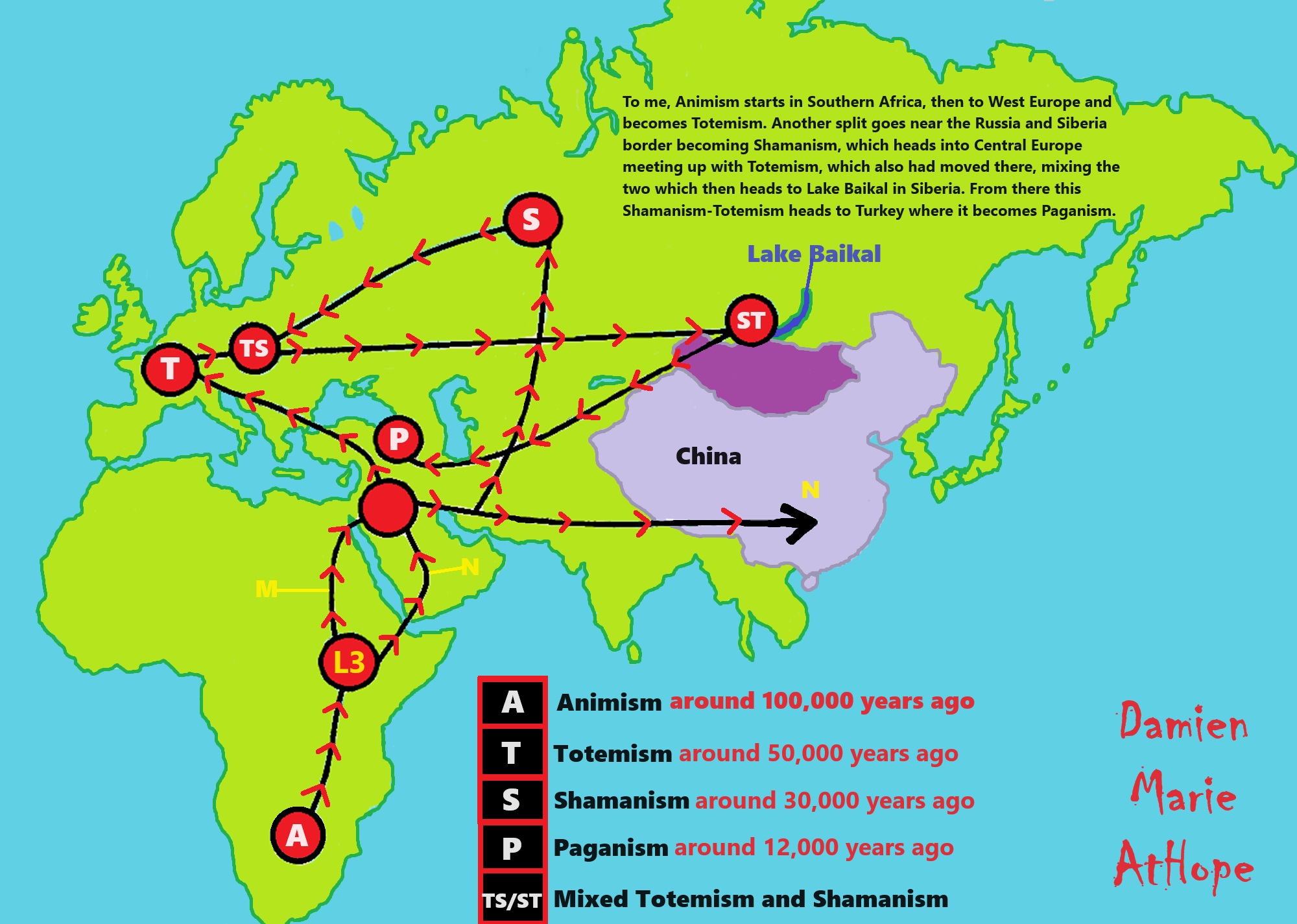

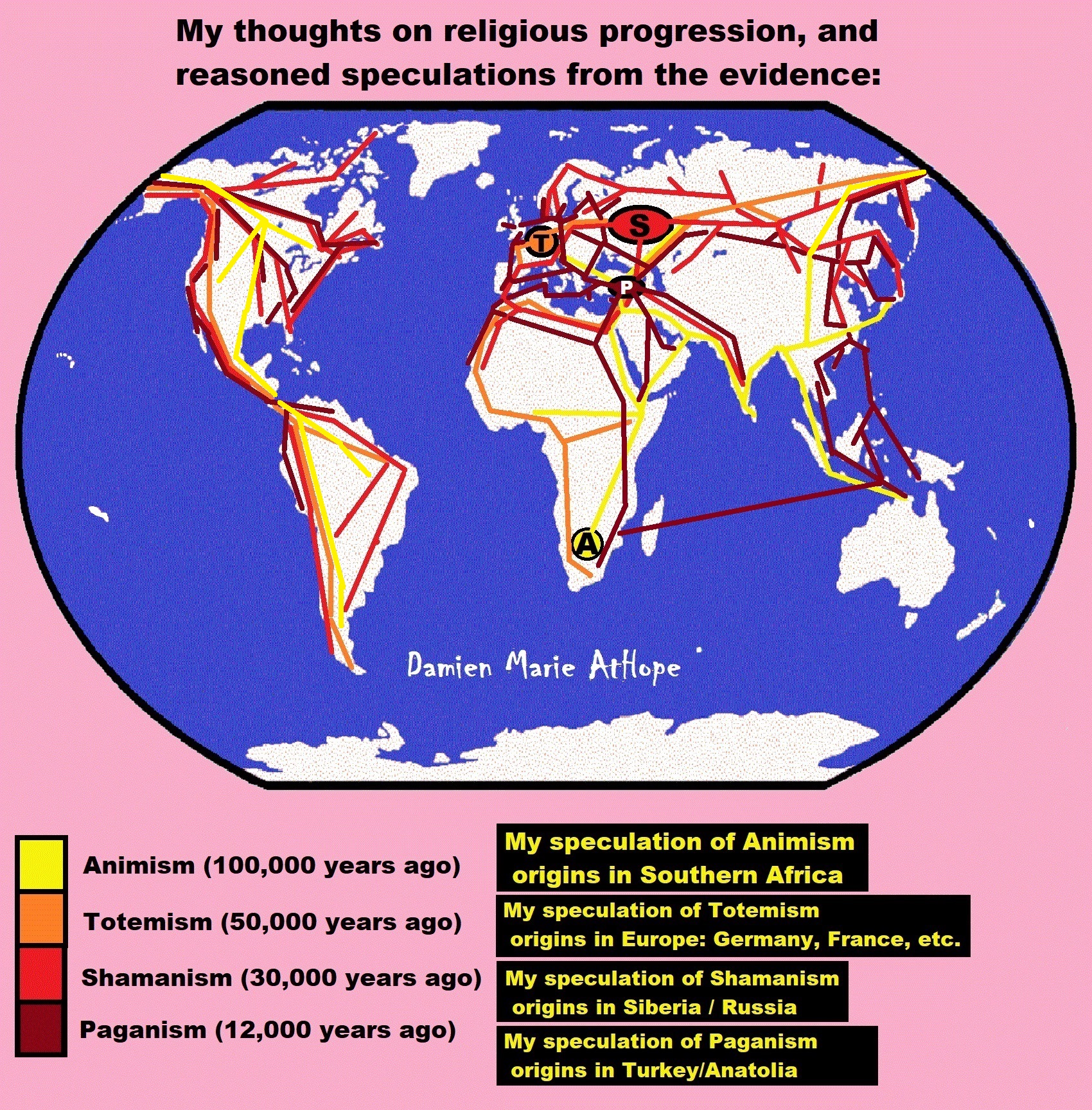

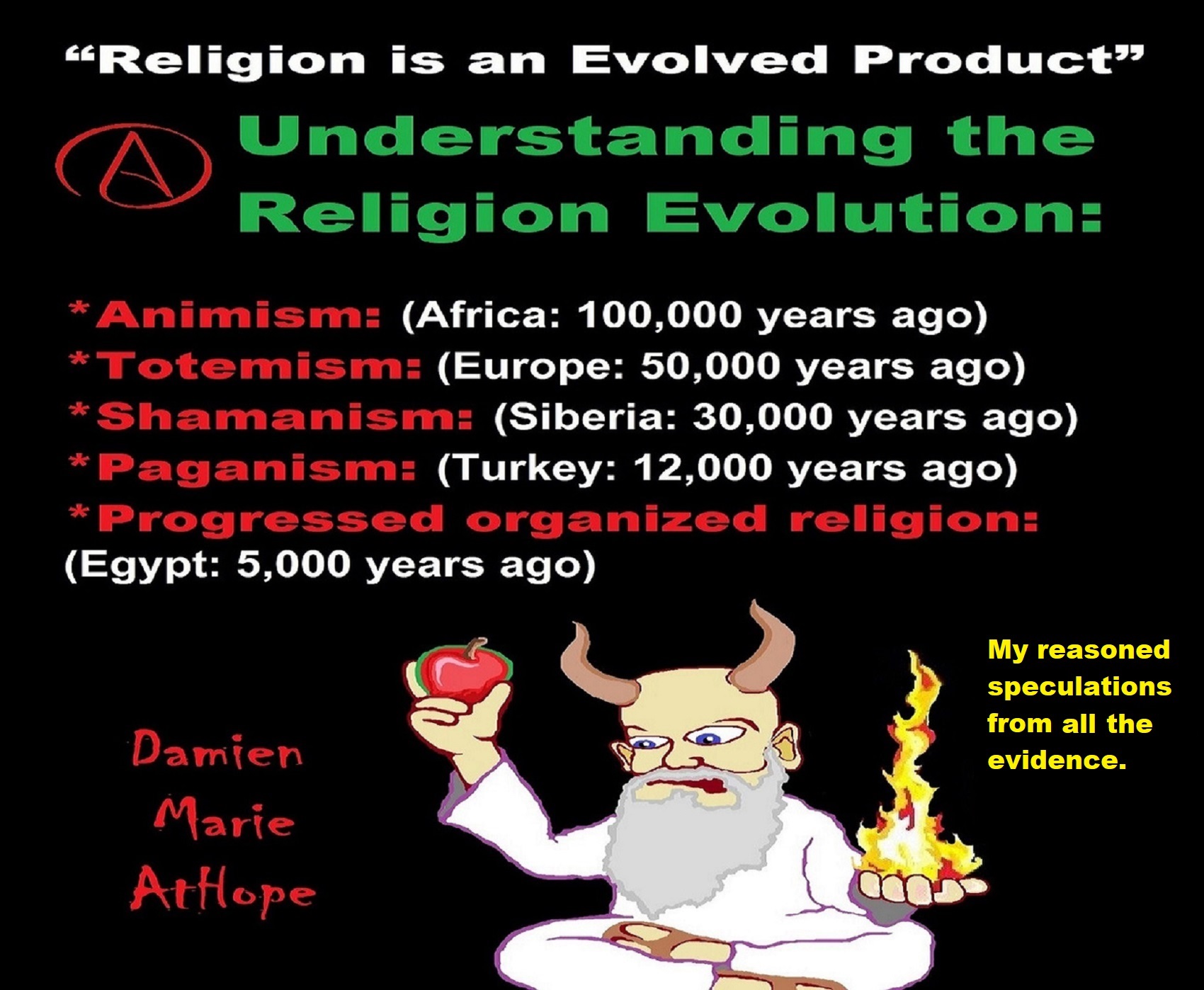

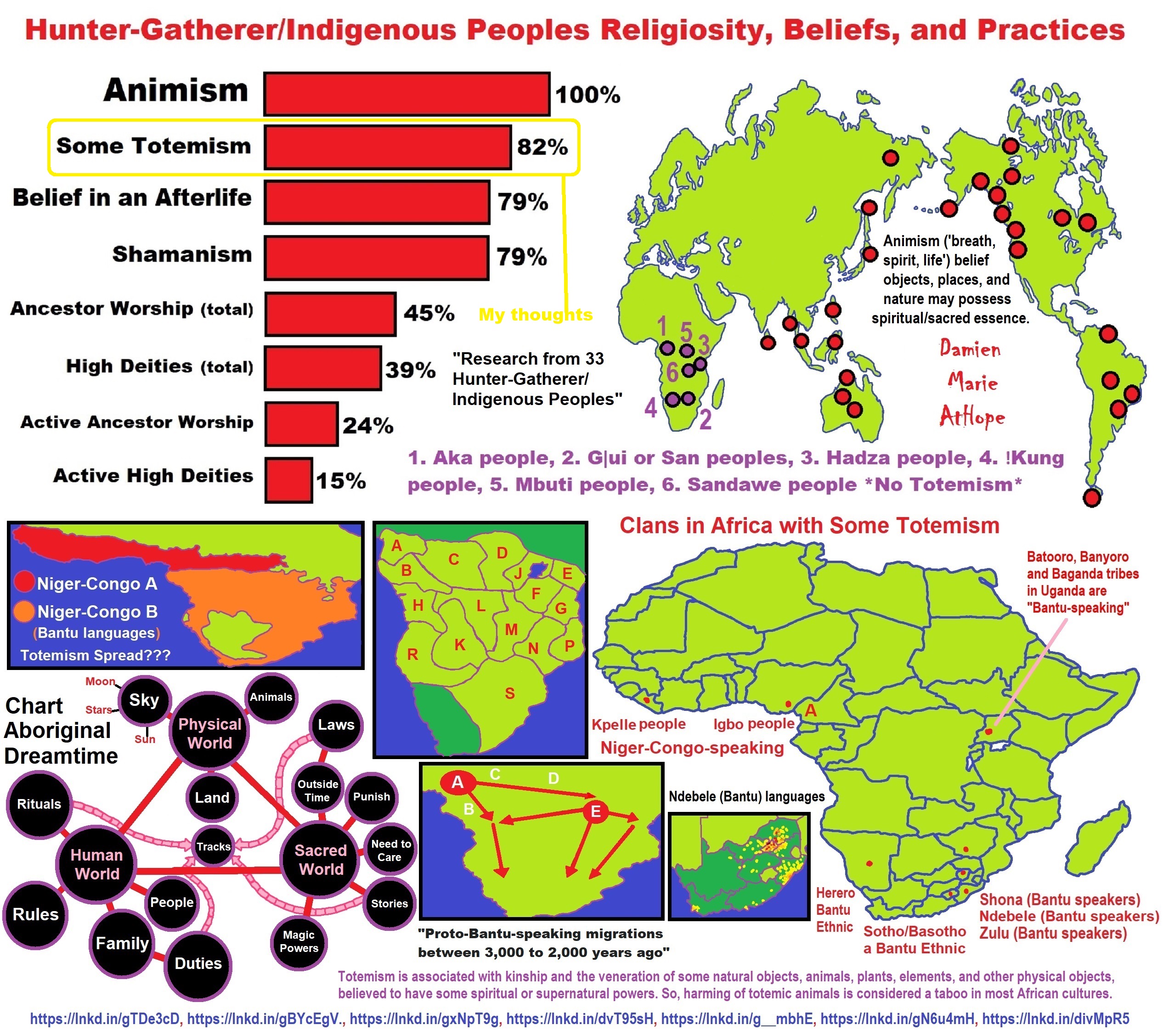

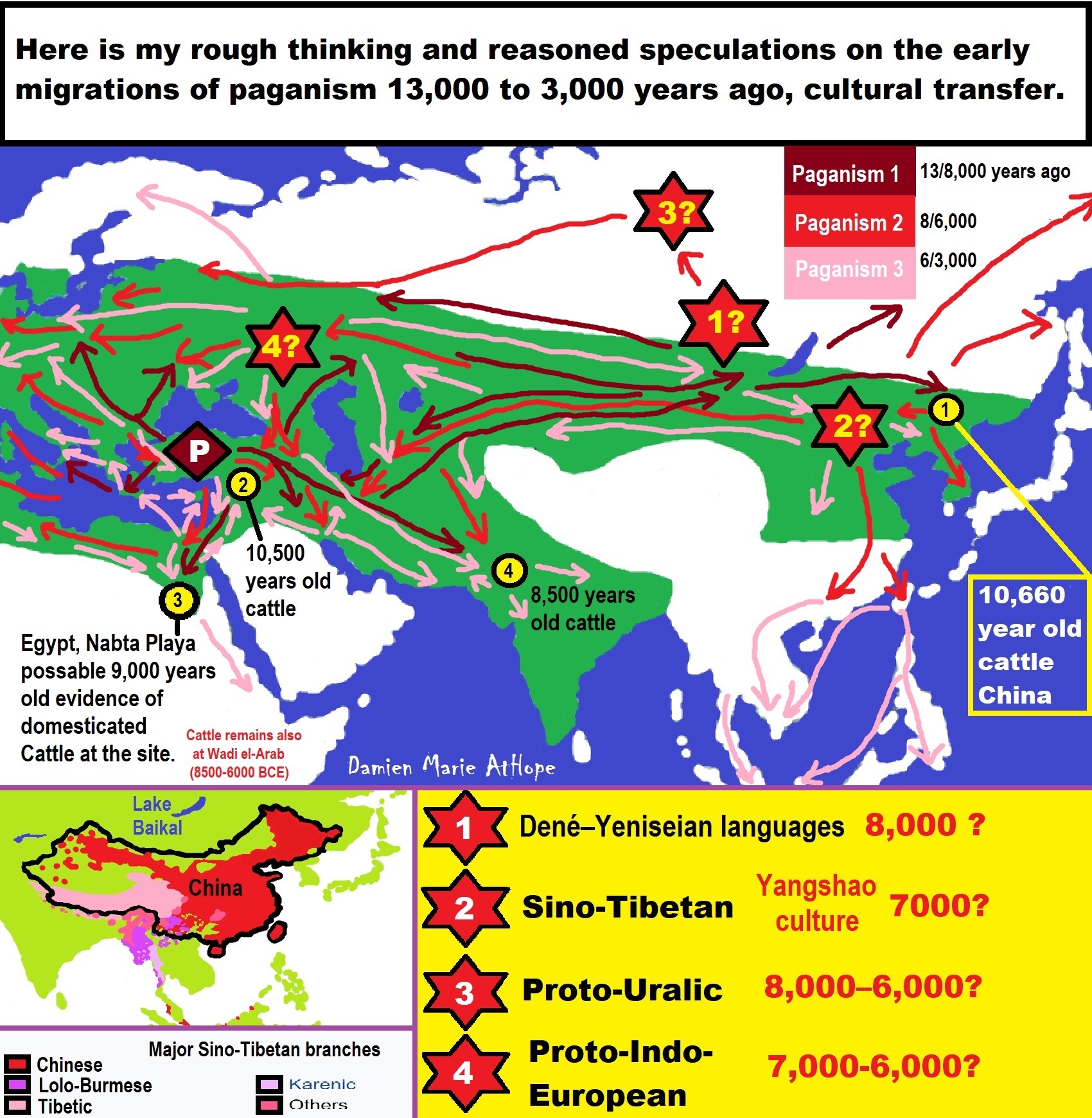

I made this article on shape-shifting beliefs, and how I see them likely emerging out totemism as well as shamanism, and then often adopted when deity beliefs emerged into paganism beliefs.

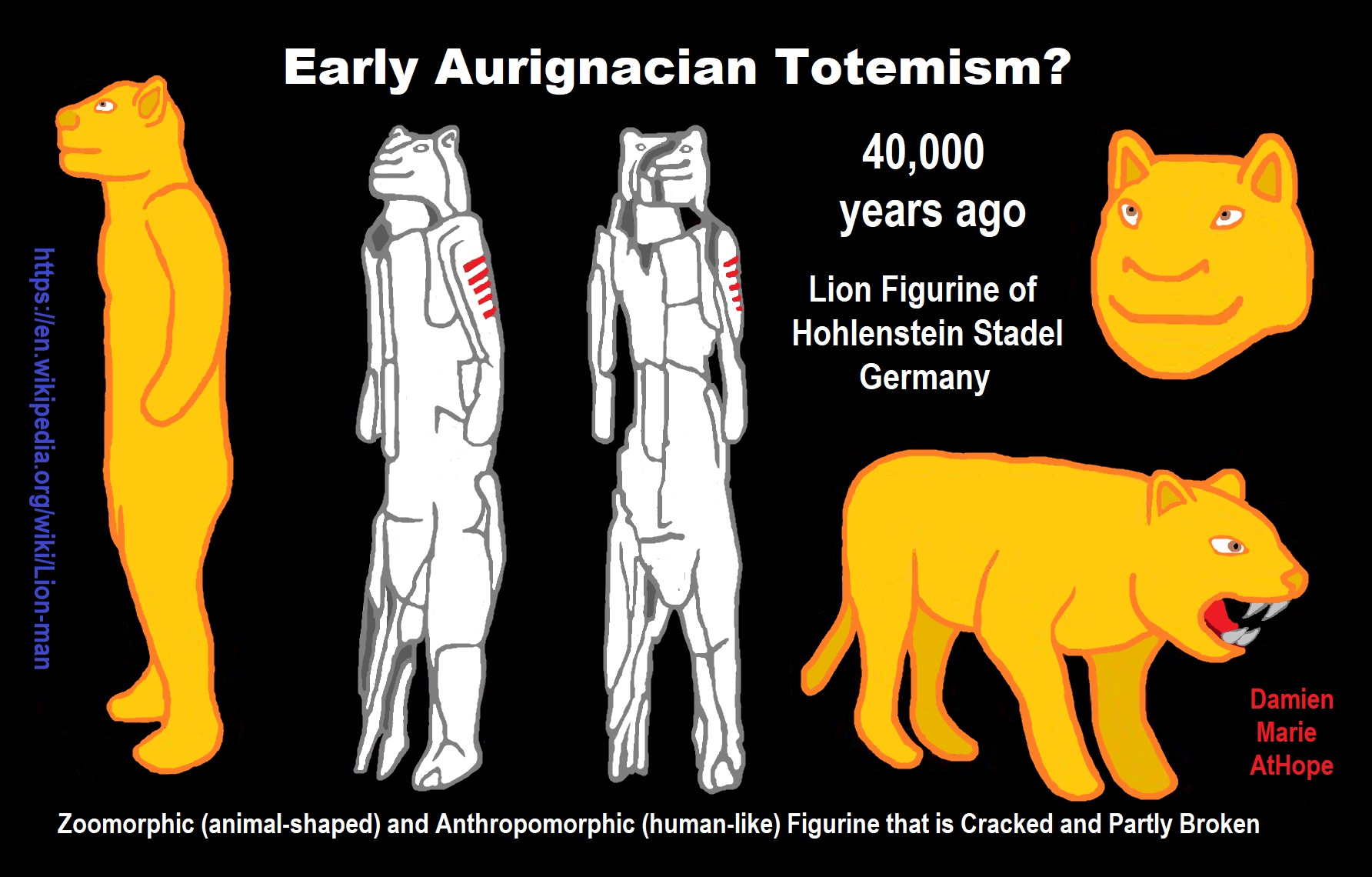

“In mythology, folklore, and speculative fiction, shapeshifting is the ability to physically transform oneself through unnatural means. The idea of shapeshifting is in the oldest forms of totemism and shamanism, as well as the oldest existent literature and epic poems such as the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Iliad.” ref

“Popular shapeshifting creatures in folklore are werewolves and vampires (mostly of European, Canadian, and Native American/early American origin), ichchadhari naag and ichchadhari naagin (shapeshifting cobras) of India, the huli jing of East Asia (including the Japanese kitsune and Korean kumiho), and the gods, goddesses, and demons and demonesses like succubus and incubus and other numerous mythologies, such as the Norse Loki or the Greek Proteus. Shapeshifting to the form of a gray wolf is specifically known as lycanthropy, and such creatures who undergo such change are called lycanthropes. Therianthropy is the more general term for human-animal shifts, but it is rarely used in that capacity. It was also common for deities to transform mortals into animals and plants.” ref

“Other terms for shapeshifters include metamorph, the Navajo skin-walker, mimic, and therianthrope. The prefix “were-“, coming from the Old English word for “man” (masculine rather than generic), is also used to designate shapeshifters; despite its root, it is used to indicate female shapeshifters as well. While the popular idea of a shapeshifter is of a human being who turns into something else, there are numerous stories about animals that can transform themselves as well.” ref

“Examples of shapeshifting in classical literature include many examples in Ovid‘s Metamorphoses, Circe‘s transforming of Odysseus‘ men to pigs in Homer‘s The Odyssey, and Apuleius‘s Lucius becoming a donkey in The Golden Ass. Proteus was noted among the gods for his shapeshifting; both Menelaus and Aristaeus seized him to win information from him, and succeeded only because they held on during his various changes. Nereus told Heracles where to find the Apples of the Hesperides for the same reason.” ref

“The Oceanid Metis, the first wife of Zeus and the mother of the goddess Athena was believed to be able to change her appearance into anything she wanted. In one story, she was so proud, that her husband, Zeus, tricked her into changing into a fly. He then swallowed her because he feared that he and Metis would have a son who would be more powerful than Zeus himself. Metis, however, was already pregnant. She stayed alive inside his head and built armor for her daughter. The banging of her metalworking made Zeus have a headache, so Hephaestus clove his head with an axe. Athena sprang from her father’s head, fully grown, and in battle armor.” ref

“In Greek mythology, the transformation is often a punishment from the gods to humans who crossed them.

- Zeus transformed King Lycaon and his children into wolves (hence lycanthropy) as a punishment for either killing Zeus’ children or serving him the flesh of Lycaon’s own murdered son Nyctimus, depending on the exact version of the myth.

- Ares assigned Alectryon to keep watch for Helios the sun god during his affair with Aphrodite, but Alectryon fell asleep, leading to their discovery and humiliation that morning. Ares turned Alectryon into a rooster, which always crows to signal the morning and the arrival of the sun.

- Demeter transformed Ascalabus into a lizard for mocking her sorrow and thirst during her search for her daughter Persephone. She also turned King Lyncus into a lynx for trying to murder her prophet Triptolemus.

- Athena transformed Arachne into a spider for challenging her as a weaver and/or weaving a tapestry that insulted the gods. She also turned Nyctimene into an owl, though in this case it was an act of mercy, as the girl wished to hide from the daylight out of shame of being raped by her father.

- Artemis transformed Actaeon into a stag for spying on her bathing, and he was later devoured by his hunting dogs.

- Galanthis was transformed into a weasel or cat after interfering in Hera‘s plans to hinder the birth of Heracles.

- Atalanta and Hippomenes were turned into lions after making love in a temple dedicated to Zeus or Cybele.

- Io was a priestess of Hera in Argos, a nymph who was raped by Zeus, who changed her into a heifer to escape detection.

- Hera punished young Tiresias by transforming him into a woman and, seven years later, back into a man.

- King Tereus, his wife Procne, and her sister Philomela were all turned into birds (a hoopoe, a swallow and a nightingale respectively), after Tereus raped Philomela and cut out her tongue, and in revenge she and Procne served him the flesh of his murdered son Itys (who in some variants is resurrected as a goldfinch).

- Callisto was turned into a bear by either Artemis or Hera for being impregnated by Zeus.

- Selene transformed Myia into a fly when she became a rival for the love of Endymion.” ref

“While the Greek gods could use transformation punitively – such as Medusa, who turned to a monster for having sexual intercourse (raped in Ovid’s version) with Poseidon in Athena‘s temple – even more frequently, the tales using it are of amorous adventure. Zeus repeatedly transformed himself to approach mortals as a means of gaining access:

- Danaë as a shower of gold

- Europa as a bull

- Leda as a swan

- Ganymede, as an eagle

- Alcmene as her husband Amphitryon

- Hera as a cuckoo

- Aegina as an eagle or a flame

- Persephone as a serpent

- Io, as a cloud

- Callisto as either Artemis or Apollo

- Nemesis (Goddess of retribution) transformed into a goose to escape Zeus‘ advances, but he turned into a swan. She later bore the egg in which Helen of Troy was found.” ref

“Vertumnus transformed himself into an old woman to gain entry to Pomona‘s orchard; there, he persuaded her to marry him. In other tales, the woman appealed to other gods to protect her from rape, and was transformed (Daphne into laurel, Corone into a crow). Unlike Zeus and other gods’ shapeshifting, these women were permanently metamorphosed. In one tale, Demeter transformed herself into a mare to escape Poseidon, but Poseidon counter-transformed himself into a stallion to pursue her, and succeeded in the rape. Caenis, having been raped by Poseidon, demanded of him that she be changed to a man. He agreed, and she became Caeneus, a form he never lost, except, in some versions, upon death.” ref

“Clytie was a nymph who loved Helios, but he did not love her back. Desperate, she sat on a rock with no food or water for nine days looking at him as he crossed the skies, until she was transformed into a purple, sun-gazing flower, the heliotropium. As a final reward from the gods for their hospitality, Baucis and Philemon were transformed, at their deaths, into a pair of trees. Eos, the goddess of the dawn, secured immortality for her lover the Trojan prince Tithonus, but not eternal youth, so he aged without dying as he shriveled and grew more and more helpless. In the end, Eos transformed him into a cicada. In some variants of the tale of Narcissus, he is turned into a narcissus flower.” ref

“Sometimes metamorphoses transform objects into humans. In the myths of both Jason and Cadmus, one task set to the hero was to sow dragon’s teeth; on being sown, they would metamorphose into belligerent warriors, and both heroes had to throw a rock to trick them into fighting each other to survive. Deucalion and Pyrrha repopulated the world after a flood by throwing stones behind them; they were transformed into people. Cadmus is also often known to have transformed into a dragon or serpent towards the end of his life. Pygmalion fell in love with Galatea, a statue he had made. Aphrodite had pity on him and transformed the stone into a living woman.” ref

“Fairies, witches, and wizards were all noted for their shapeshifting ability. Not all fairies could shapeshift, some having only the appearance of shapeshifting, through their power, called “glamour”, to create illusions, and some were limited to changing their size, as with the spriggans, and others to a few forms. But others, such as the Hedley Kow, could change to many forms, and both human and supernatural wizards were capable of both such changes, and inflicting them on others.” ref

“In Celtic mythology, Pwyll was transformed by Arawn into Arawn’s shape, and Arawn transformed himself into Pwyll’s so that they could trade places for a year and a day. Llwyd ap Cil Coed transformed his wife and attendants into mice to attack a crop in revenge; when his wife is captured, he turns himself into three clergymen in succession to try to pay a ransom.” ref

“Math fab Mathonwy and Gwydion transform flowers into a woman named Blodeuwedd, and when she betrays her husband Lleu Llaw Gyffes, who is transformed into an eagle, they transform her again, into an owl. Gilfaethwy committed rape on Goewin, Math fab Mathonwy’s virgin foothold, with help from his brother Gwydion. Both were transformed into animals, for one year each. Gwydion was transformed into a stag, sow, and wolf, and Gilfaethwy into a hind, boar, and she-wolf. Each year, they had a child. Math turned the three young animals into boys.” ref

“Gwion, having accidentally taken some of the wisdom potions that Ceridwen was brewing for her son, fled from her through a succession of changes that she answered with changes of her own, ending with his being eaten, a grain of corn, by her as a hen. She became pregnant, and he was reborn in a new form, as Taliesin.” ref

“Tales abound about the selkie, a seal that can remove its skin to make contact with humans for only a short amount of time before it must return to the sea. Clan MacColdrum of Uist‘s foundation myths include a union between the founder of the clan and a shape-shifting selkie. Another such creature is the Scottish selkie, which needs its sealskin to regain its form. In The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry the (male) selkie seduces a human woman. Such stories surrounding these creatures are usually romantic tragedies.” ref

“Scottish mythology features shapeshifters, which allows the various creatures to trick, deceive, hunt, and kill humans. Water spirits such as the each-uisge, which inhabit lochs and waterways in Scotland, were said to appear as a horse or a young man. Other tales include kelpies who emerge from lochs and rivers in the disguise of a horse or woman to ensnare and kill weary travelers. Tam Lin, a man captured by the Queen of the Fairies is changed into all manner of beasts before being rescued. He finally turned into a burning coal and was thrown into a well, whereupon he reappeared in his human form. The motif of capturing a person by holding him through all forms of transformation is a common thread in folktales.” ref

“Perhaps the best-known Irish myth is that of Aoife who turned her stepchildren, the Children of Lir, into swans to be rid of them. Likewise, in the Tochmarc Étaíne, Fuamnach jealously turns Étaín into a butterfly. The most dramatic example of shapeshifting in Irish myth is that of Tuan mac Cairill, the only survivor of Partholón‘s settlement of Ireland. In his centuries-long life, he became successively a stag, a wild boar, a hawk, and finally a salmon before being eaten and (as in the Wooing of Étaín) reborn as a human.” ref

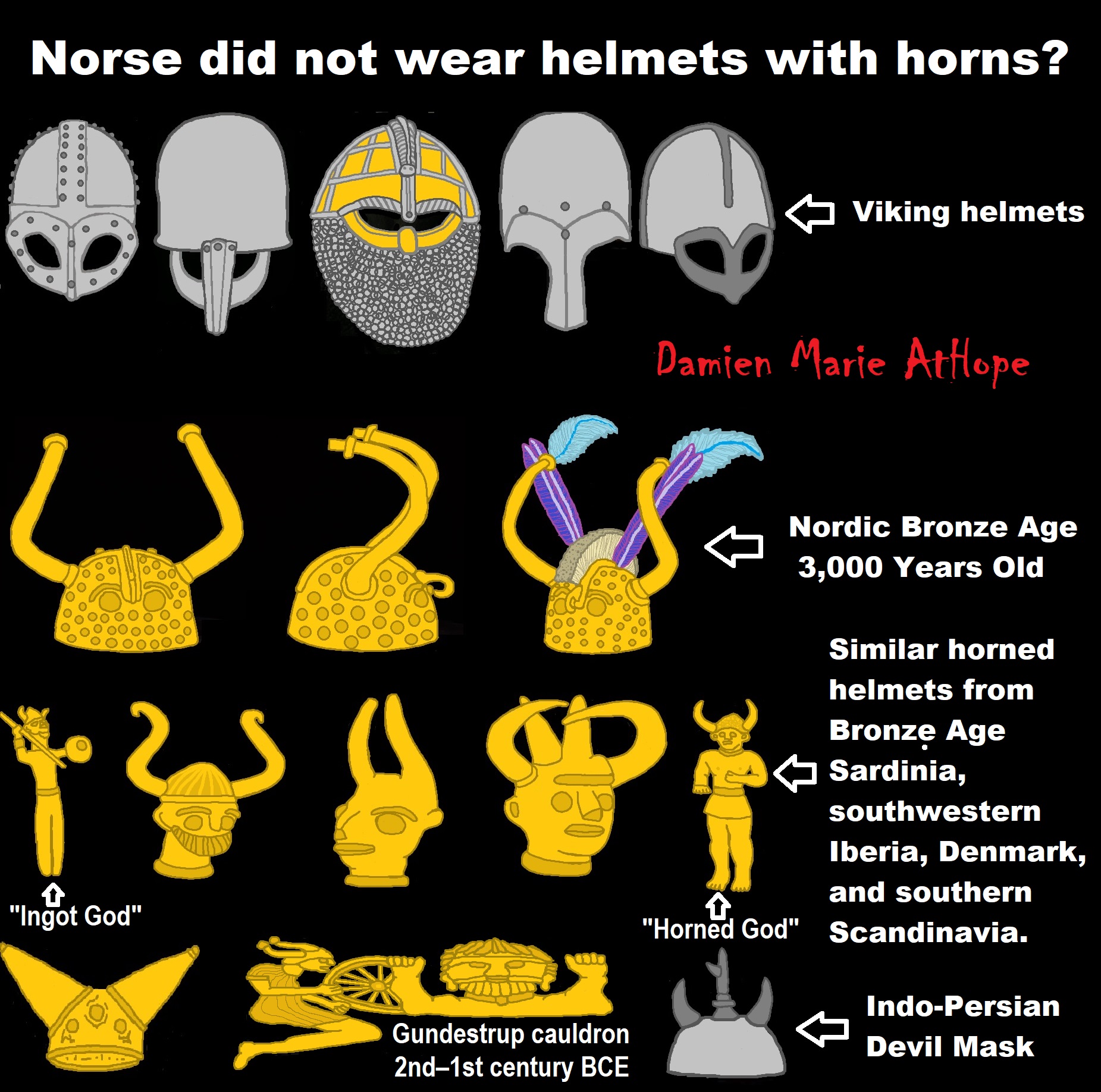

The Púca is a Celtic faery, and also a deft shapeshifter. He can transform into many different, terrifying forms. Sadhbh, the wife of the famous hero Fionn mac Cumhaill, was changed into a deer by the druid Fer Doirich when she spurned his amorous interests. There is a significant amount of literature about shapeshifters that appear in a variety of Norse tales. In the Lokasenna, Odin and Loki taunt each other with having taken the form of females and nursing offspring to which they had given birth. A 13th-century Edda relates Loki taking the form of a mare to bear Odin’s steed Sleipnir which was the fastest horse ever to exist, and also the form of a she-wolf to bear Fenrir.” ref

“Svipdagr angered Odin, who turned him into a dragon. Despite his monstrous appearance, his lover, the goddess Freyja, refused to leave his side. When the warrior Hadding found and slew Svipdagr, Freyja cursed him to be tormented by a tempest and shunned like the plague wherever he went. In the Hyndluljóð, Freyja transformed her protégé Óttar into a boar to conceal him. She also possessed a cloak of falcon feathers that allowed her to transform into a falcon, which Loki borrowed on occasion.” ref

“The Volsunga saga contains many shapeshifting characters. Siggeir‘s mother changed into a wolf to help torture his defeated brothers-in-law with slow and ignominious deaths. When one, Sigmund, survived, he and his nephew and son Sinfjötli killed men wearing wolfskins; when they donned the skins themselves, they were cursed to become werewolves. The dwarf Andvari is described as being able to magically turn into a pike. Alberich, his counterpart in Richard Wagner‘s Der Ring des Nibelungen, using the Tarnhelm, takes on many forms, including a giant serpent and a toad, in a failed attempt to impress or intimidate Loki and Odin/Wotan.” ref

“Fafnir was originally a dwarf, a giant, or even a human, depending on the exact myth, but in all variants, he transformed into a dragon—a symbol of greed—while guarding his ill-gotten hoard. His brother, Ótr, enjoyed spending time as an otter, which led to his accidental slaying by Loki. In Scandinavia, there existed, for example, the famous race of she-werewolves known by the name of Maras, women who took on the appearance of huge half-human and half-wolf monsters that stalked the night in search of human or animal prey. If a woman gives birth at midnight and stretches the membrane that envelopes the child when it is brought forth, between four sticks and creeps through it, naked, she will bear children without pain; but all the boys will be shamans, and all the girls Maras.” ref

“The Nisse is sometimes said to be a shapeshifter. This trait also is attributed to Hulder. Gunnhild, Mother of Kings (Gunnhild konungamóðir) (c. 910 – c. 980), a quasi-historical figure who appears in the Icelandic Sagas, according to which she was the wife of Eric Bloodaxe, was credited with magic powers – including the power of shapeshifting and turning at will into a bird. She is the central character of the novel Mother of Kings by Poul Anderson, which considerably elaborates on her shapeshifting abilities.” ref

“In Armenian mythology, shapeshifters include the Nhang, a serpentine river monster that can transform itself into a woman or seal, and will drown humans and then drink their blood; or the beneficial Shahapet, a guardian spirit that can appear either as a man or a snake. Tatar folklore includes Yuxa, a hundred-year-old snake that can transform itself into a beautiful young woman, and seeks to marry men to have children.” ref

Indian

- Shapeshifting cobra: A common male cobra will become an ichchadhari naag (male shapeshifting cobra) and a common female cobra will become an ichchadhari naagin (female shapeshifting cobra) after 100 years of tapasya (penance). After being blessed by Lord Shiva, they attain a human form of their own, can shapeshift into any living creature, and can live for more than a hundred years without getting old.

- Yoginis were associated with the power of shapeshifting into female animals.

- In the Indian fable The Dog Bride from Folklore of the Santal Parganas by Cecil Henry Bompas, a buffalo herder falls in love with a dog that has the power to turn into a woman when she bathes.

- In Kerala, there was a legend about the Odiyan clan, who in Kerala folklore are men believed to possess shapeshifting abilities and can assume animal forms. Odiyans are said to have inhabited the Malabar region of Kerala before the widespread use of electricity.” ref

“Chinese mythology contains many tales of animal shapeshifters, capable of taking on human form. The most common such shapeshifter is the huli jing, a fox spirit that usually appears as a beautiful young woman; most are dangerous, but some feature as the heroines of love stories. Madame White Snake is one such legend; a snake falls in love with a man, and the story recounts the trials she and her husband faced.” ref

“In Japanese folklore obake are a type of yōkai with the ability to shapeshifting. The fox, or kitsune is among the most commonly known, but other such creatures include the bakeneko, the mujina, and the tanuki. Korean mythology also contains a fox with the ability to shapeshift. Unlike its Chinese and Japanese counterparts, the kumiho is always malevolent. Usually its form is of a beautiful young woman; one tale recounts a man, a would-be seducer, revealed as a kumiho. The kumiho has nine tails and as she desires to be a full human, she uses her beauty to seduce men and eat their hearts (or in some cases livers where the belief is that 100 livers would turn her into a real human).” ref

“Philippine mythology includes the Aswang, a vampiric monster capable of transforming into a bat, a large black dog, a black cat, a black boar, or some other form to stalk humans at night. The folklore also mentions other beings such as the Kapre, the Tikbalang, and the Engkanto, which change their appearances to woo beautiful maidens. Also, talismans (called “anting-anting” or “birtud” in the local dialect), can give their owners the ability to shapeshift. In one tale, Chonguita the Monkey Wife, a woman is turned into a monkey, only becoming human again if she can marry a handsome man.” ref

“In Somali mythology Qori ismaris (“One who rubs himself with a stick”) was a man who could transform himself into a “Hyena-man” by rubbing himself with a magic stick at nightfall and by repeating this process could return to his human state before dawn. ǀKaggen is a demi-urge and folk hero of the ǀXam people of southern Africa. He is a trickster god who can shape shift, usually taking the form of a praying mantis but also a bull eland, a louse, a snake, and a caterpillar. The Ligahoo or loup-garou is the shapeshifter of Trinidad and Tobago’s folklore. This unique ability is believed to be handed down in some old creole families, and is usually associated with witch-doctors and practitioners of African magic.” ref

“Mapuche (Argentina and Chile), The name of the Nahuel Huapi Lake in Argentina derives from the toponym of its major island in Mapudungun (Mapuche language): “Island of the Jaguar (or Puma)”, from nahuel, “puma (or jaguar)”, and huapí, “island”. There is, however, more to the word “Nahuel” – it can also signify “a man who by sorcery has been transformed into a puma” (or jaguar). In Slavic mythology, one of the main gods Veles was a shapeshifting god of animals, magic and the underworld. He was often represented as a bear, wolf, snake or owl. He also became a dragon while fighting Perun, the Slavic storm god.” ref

Therianthropy

“Therianthropy is the mythological ability or affliction of individuals to metamorphose into animals or hybrids by means of shapeshifting. It is possible that cave drawings found at Cave of the Trois-Frères, in France, depict ancient beliefs in the concept. The best-known form of therianthropy, called lycanthropy, is found in stories of werewolves. Therianthropy was used to describe spiritual beliefs in animal transformation in a 1915 Japanese publication, A History of the Japanese People from the Earliest Times to the End of the Meiji Era.” ref

“Therianthropy refers to the fantastical, or mythological, ability of some humans to change into animals. Therianthropes are said to change forms via shapeshifting. Therianthropy has long existed in mythology, and seems to be depicted in ancient cave drawings such as The Sorcerer, a pictograph executed at the Palaeolithic cave drawings found in the Pyrenees at the Cave of the Trois-Frères, France, archeological site. Theriocephaly (Greek “animal headedness”) refers to beings that have an animal head attached to an anthropomorphic, or human, body; for example, the animal-headed forms of gods depicted in ancient Egyptian religion (such as Ra, Sobek, Anubis).” ref

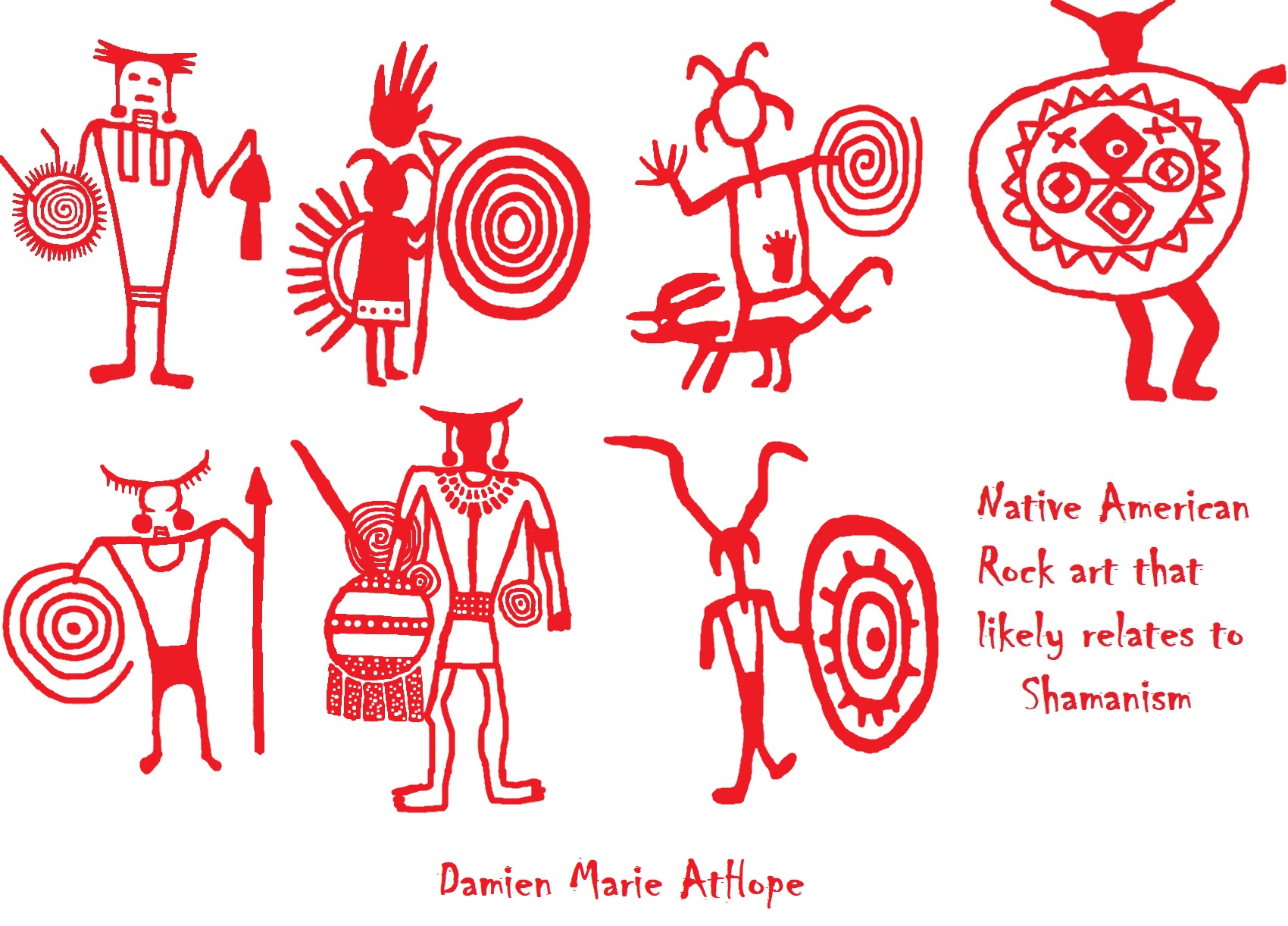

Skin-walkers and naguals

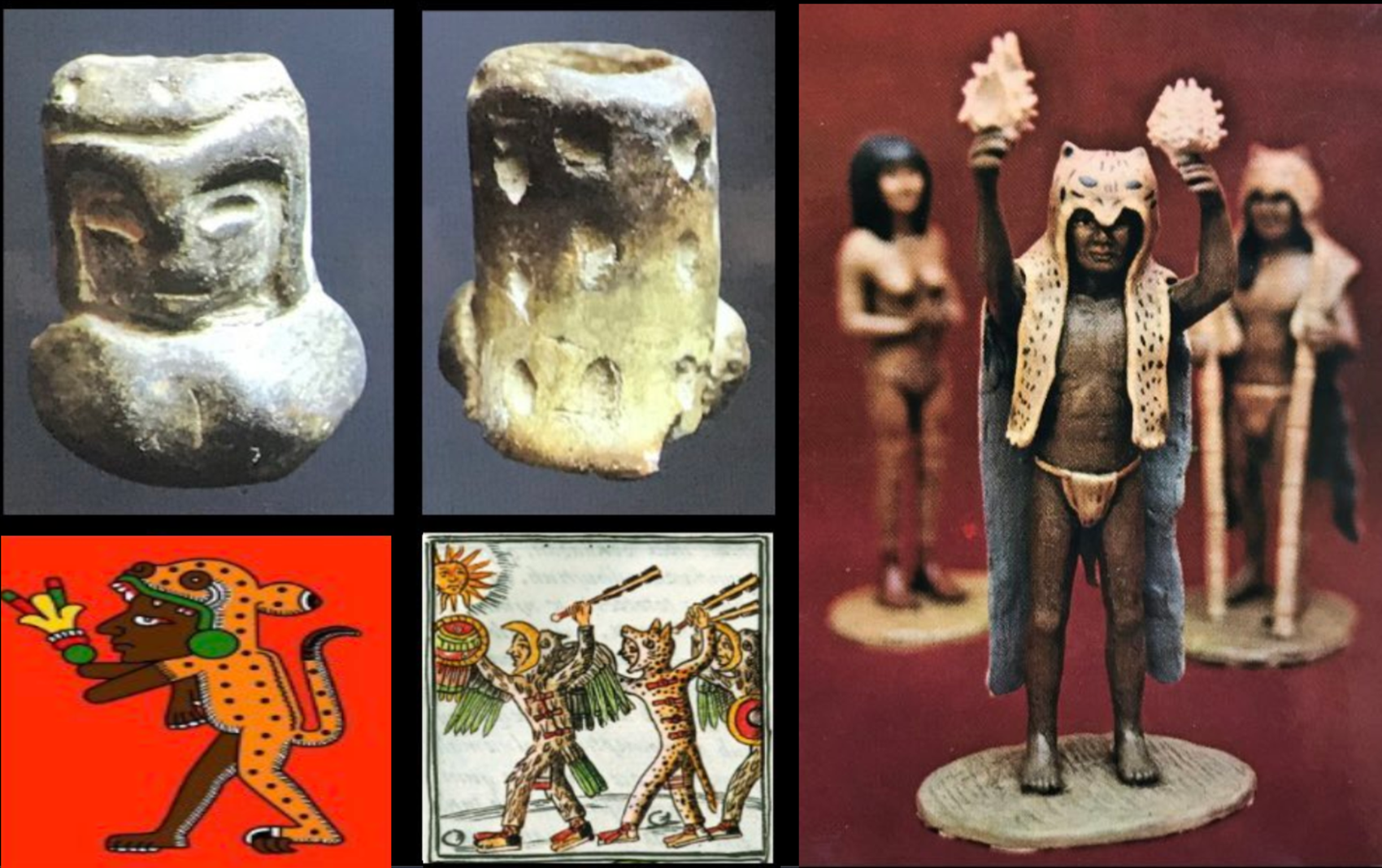

“Some Native American and First Nation legends talk about skin-walkers—people with the supernatural ability to turn into any animal they desire. To do so, however, they first must be wearing a pelt of the specific animal. In the folk religion of Mesoamerica, a nagual (or nahual) is a human being who has the power to magically turn themselves into animal forms—most commonly donkeys, turkeys, and dogs—but can also transform into more powerful jaguars and pumas.” ref

Animal Ancestors

“Stories of humans descending from animals are found in the oral traditions of many tribal and clan origins. Sometimes the original animals had assumed human form in order to ensure their descendants retained their human shapes; other times the origin story is of a human marrying a normal animal. North American indigenous traditions mingle the ideas of bear ancestors and ursine shapeshifters, with bears often being able to shed their skins to assume human form, marrying human women in this guise. The offspring may be creatures with combined anatomy, they may be very beautiful children with uncanny strength, or they may be shapeshifters themselves.” ref

“P’an Hu is represented in various Chinese legends as a supernatural dog, a dog-headed man, or a canine shapeshifter that married an emperor’s daughter and founded at least one race. When he is depicted as a shapeshifter, all of him can become human except for his head. The race(s) descended from P’an Hu were often characterized by Chinese writers as monsters who combined human and dog anatomy. In Turkic mythology, the wolf is a revered animal. The Turkic legends say the people were descendants of wolves. The legend of Asena is an old Turkic myth that tells of how the Turkic people were created. In the legend, a small Turkic village in northern China is raided by Chinese soldiers, with one baby left behind. An old she-wolf with a sky-blue mane named Asena finds the baby and nurses him. She later gives birth to half-wolf, half-human cubs who are the ancestors of the Turkic people.” ref

“In Melanesian cultures there exists the belief in the tamaniu or atai, which describes the animal counterpart to a person. Specifically among the Solomon Islands in Melanesia, the term atai means “soul” in the Mota language and is closely related to the term ata, meaning a “reflected image” in Maori and “shadow” in Samoan. Terms relating to the “spirit” in these islands such as figona and vigona convey a being that has not been in human form The animal counterpart depicted may take the form of an eel, shark, lizard, or some other creature. This creature is considered to be corporeal and can understand human speech. It shares the same soul as its master. This concept is found in similar legends which have many characteristics typical of shapeshifter tales. Among these characteristics is the theory that death or injury would affect both the human and animal form at once.” ref

“Among a sampled set of psychiatric patients, the belief of being part animal, or clinical lycanthropy, is generally associated with severe psychosis but not always with any specific psychiatric diagnosis or neurological findings. Others regard clinical lycanthropy as a delusion in the sense of the self-disorder found in affective and schizophrenic disorders, or as a symptom of other psychiatric disorders.” ref

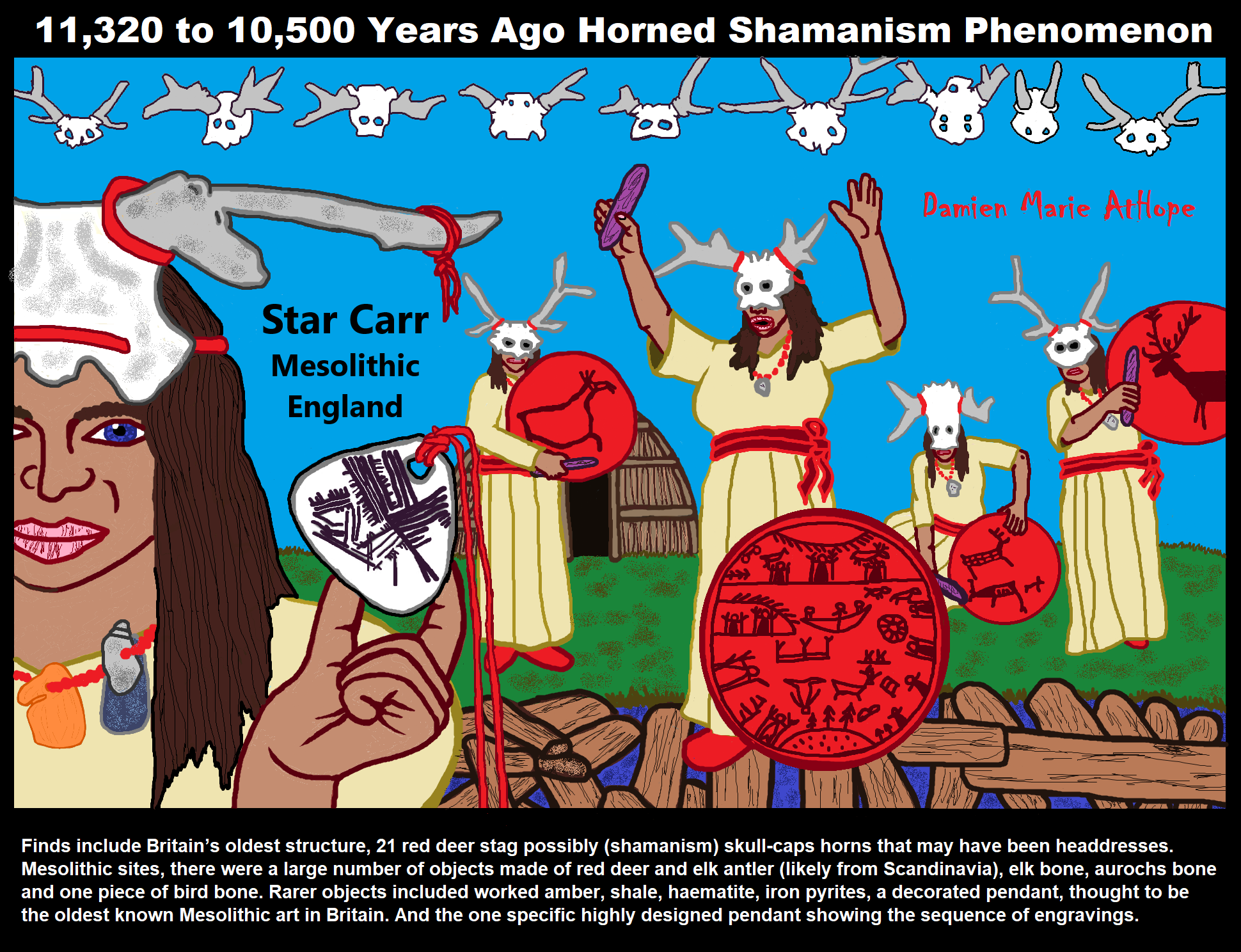

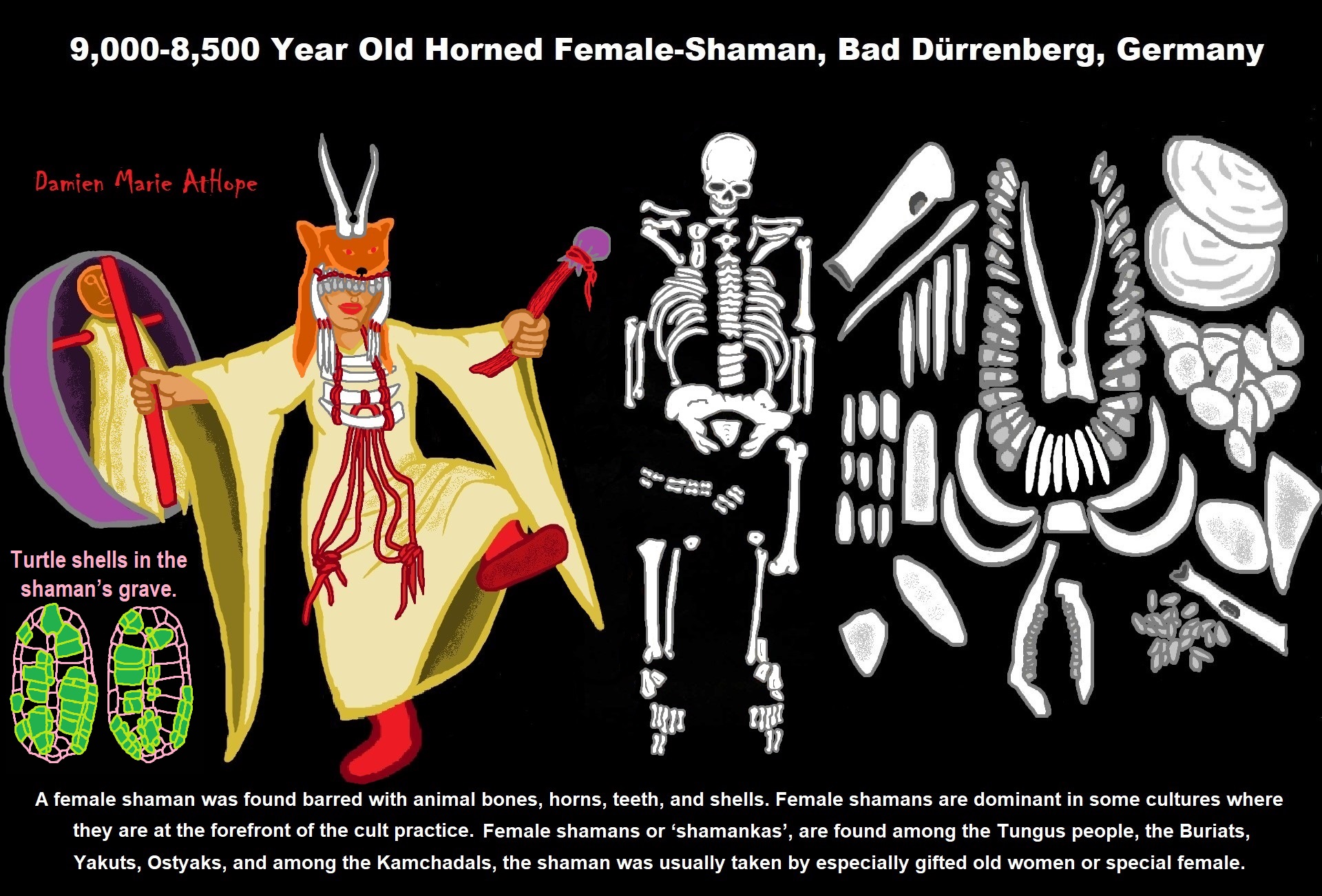

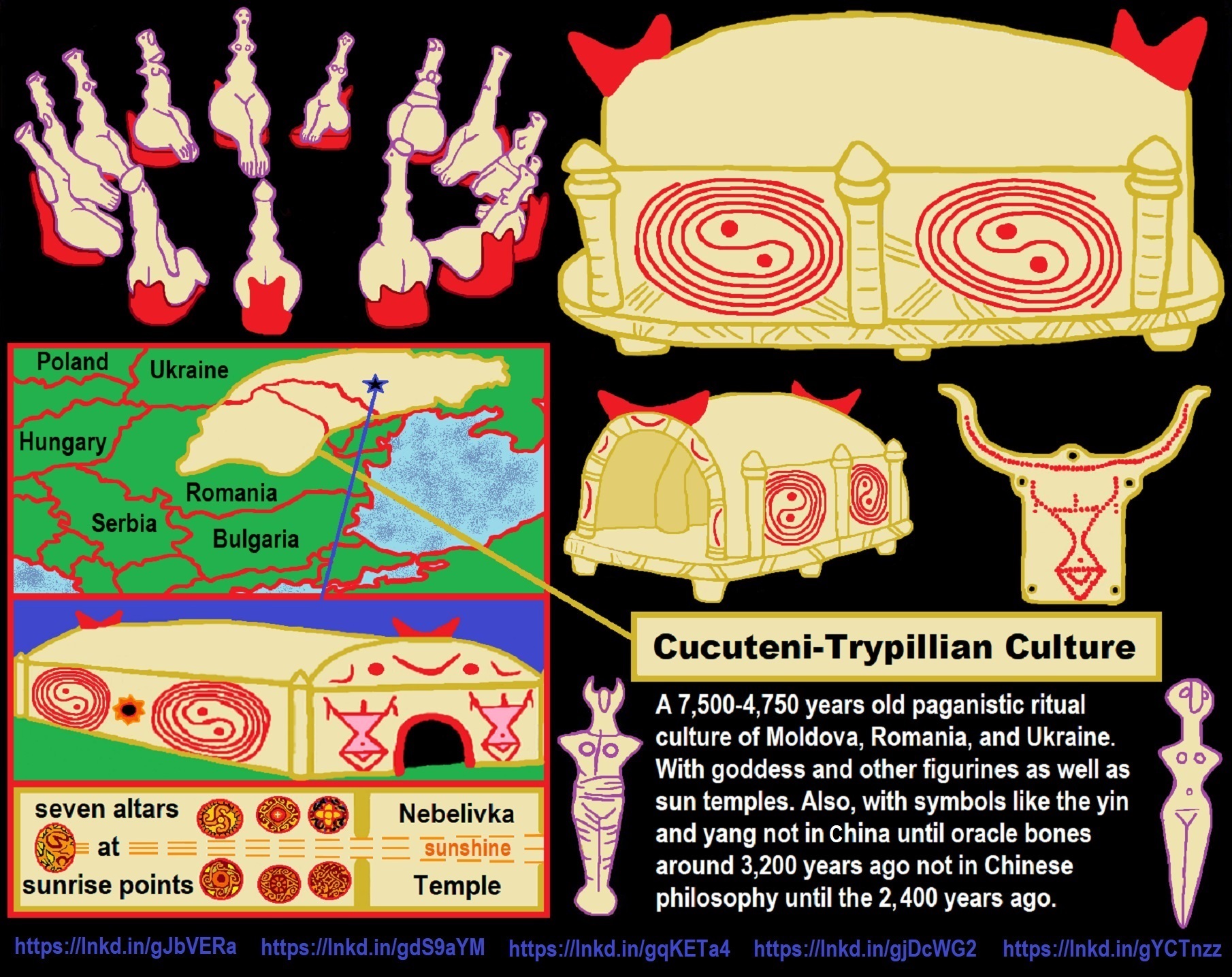

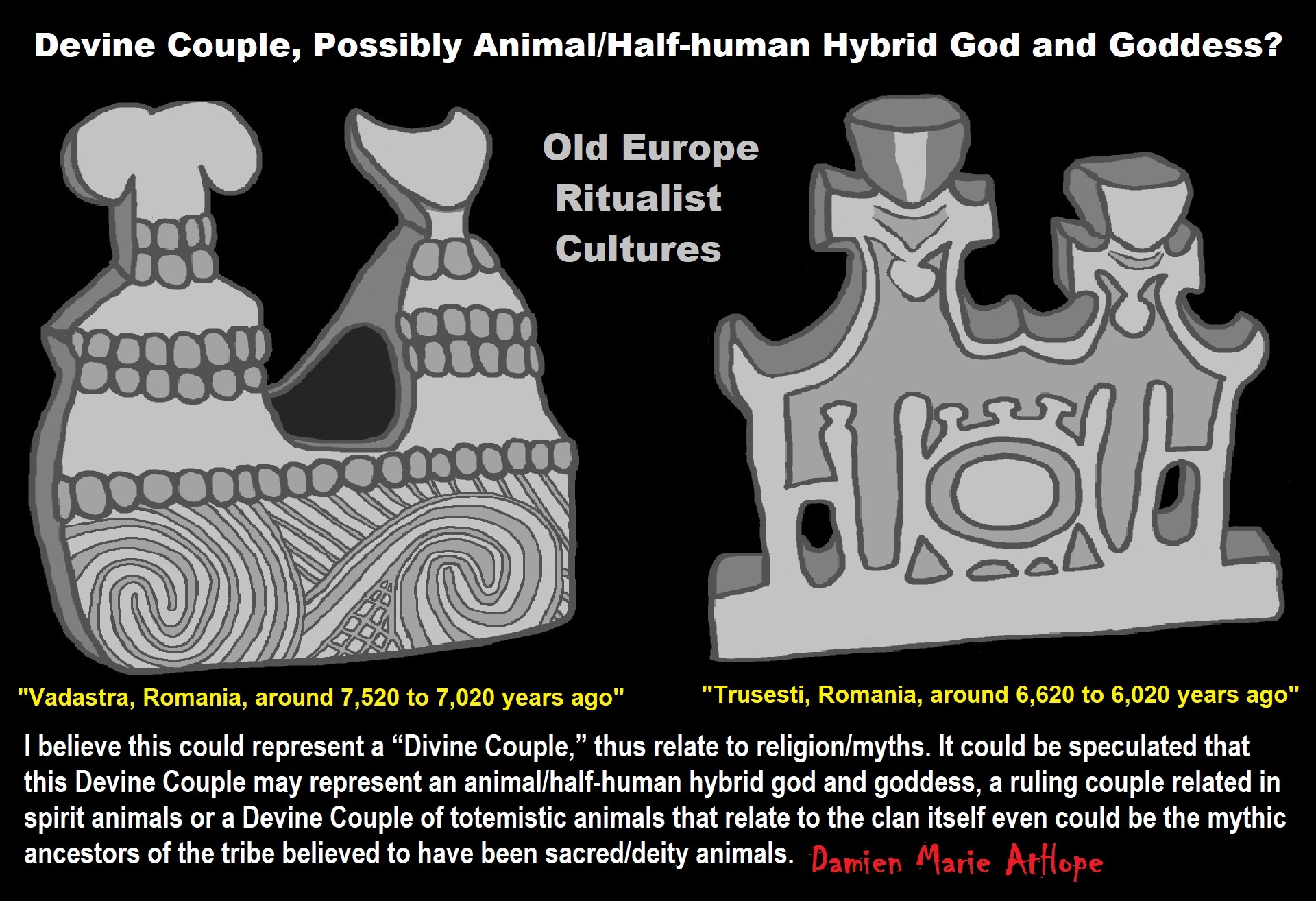

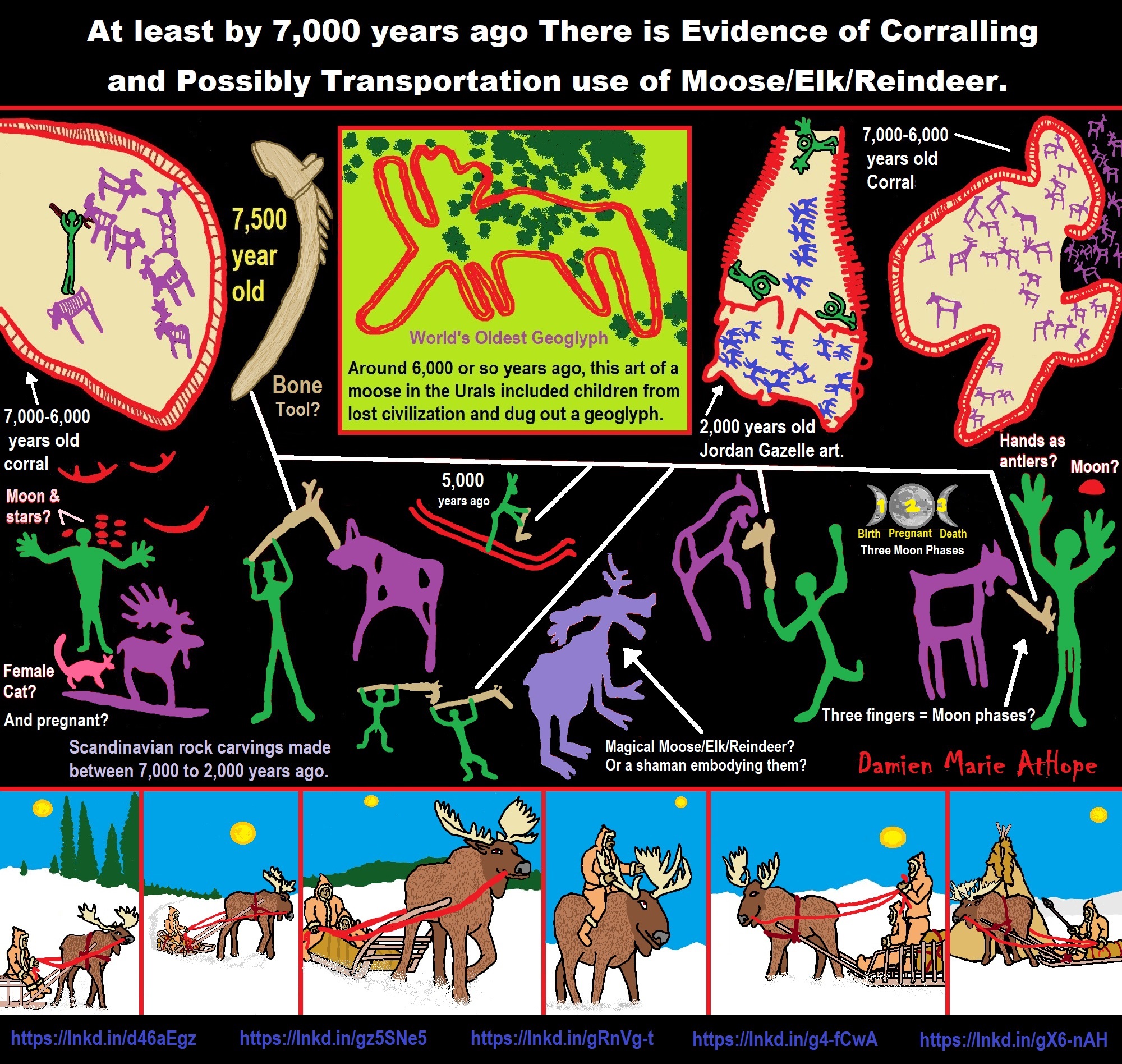

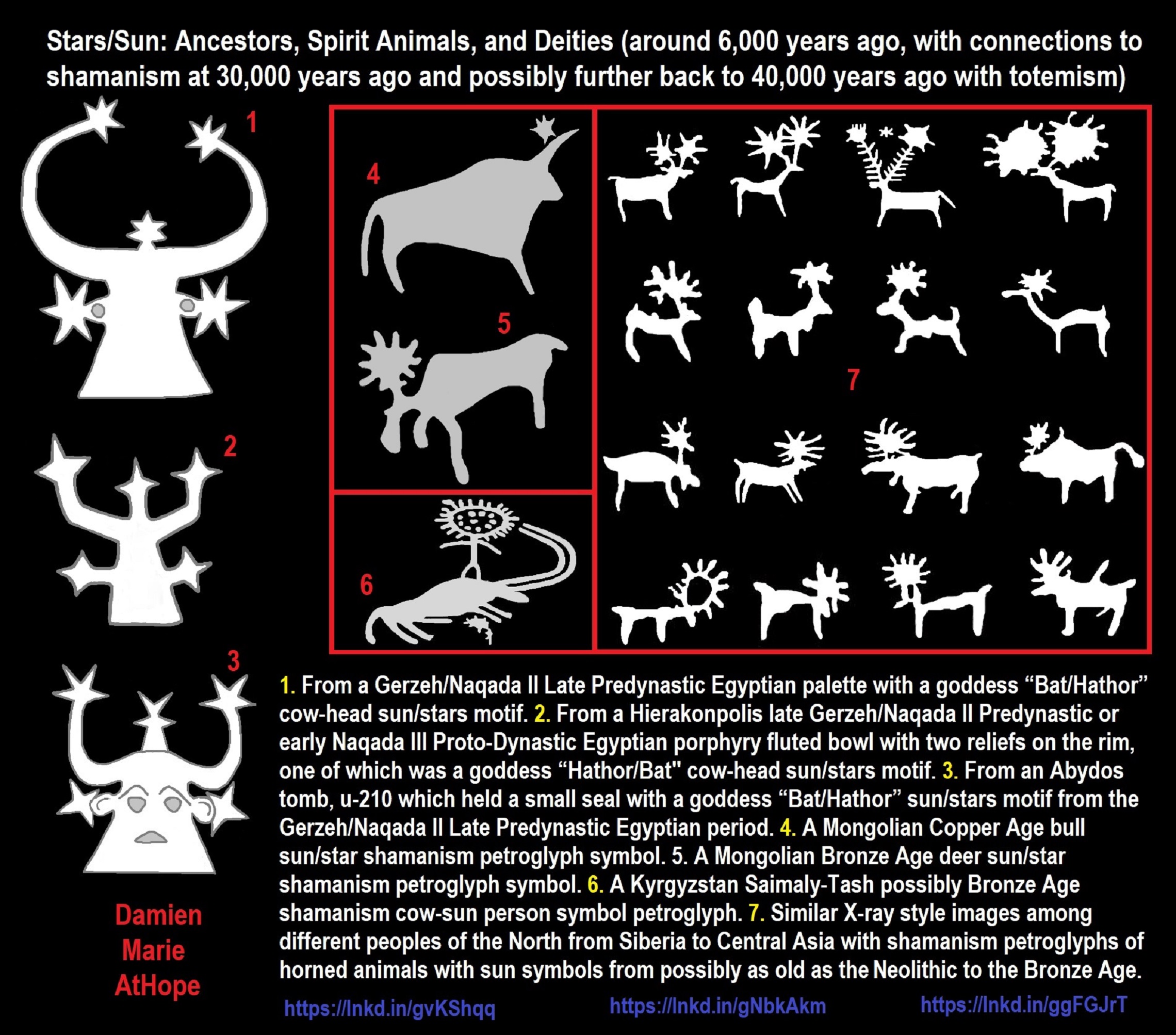

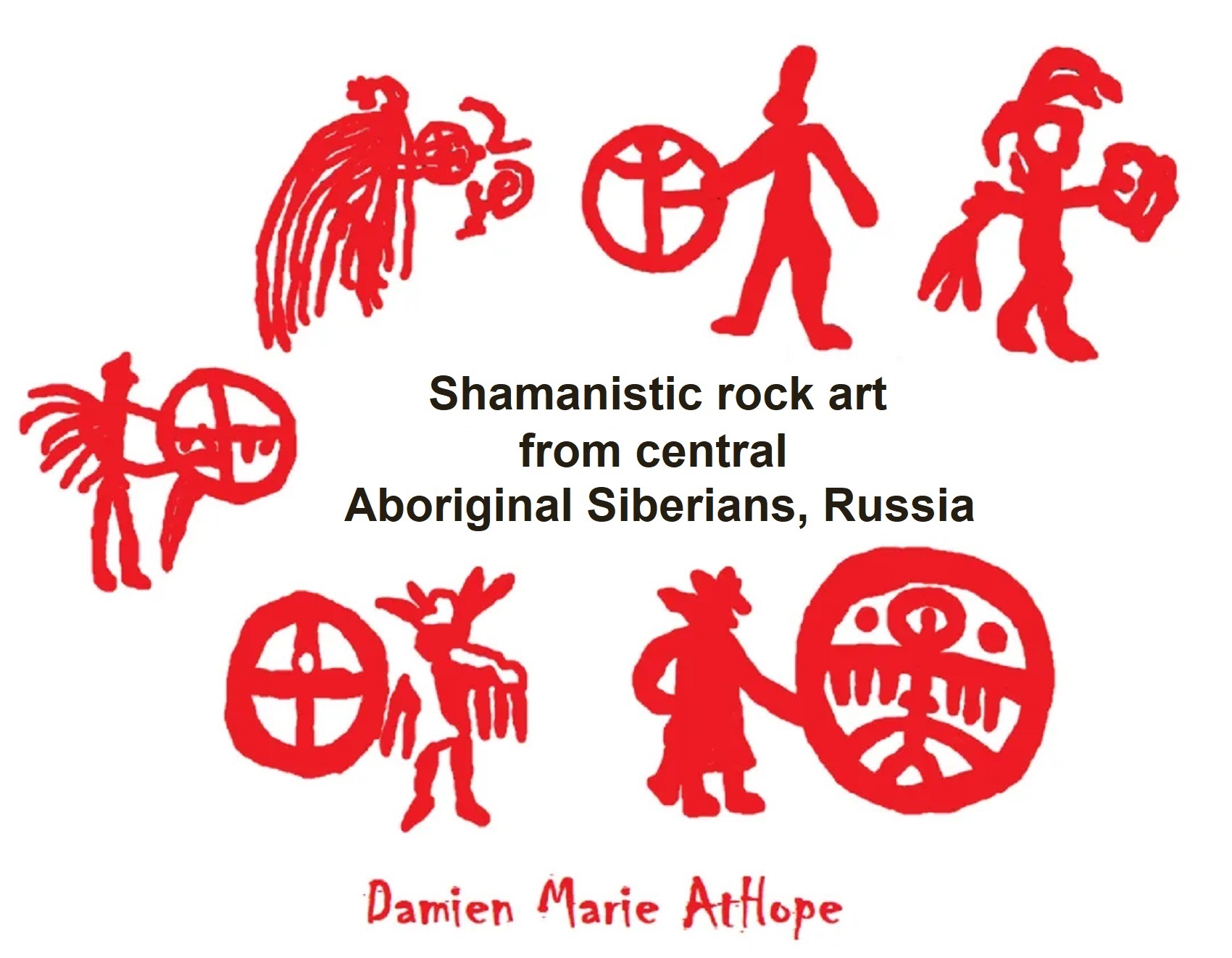

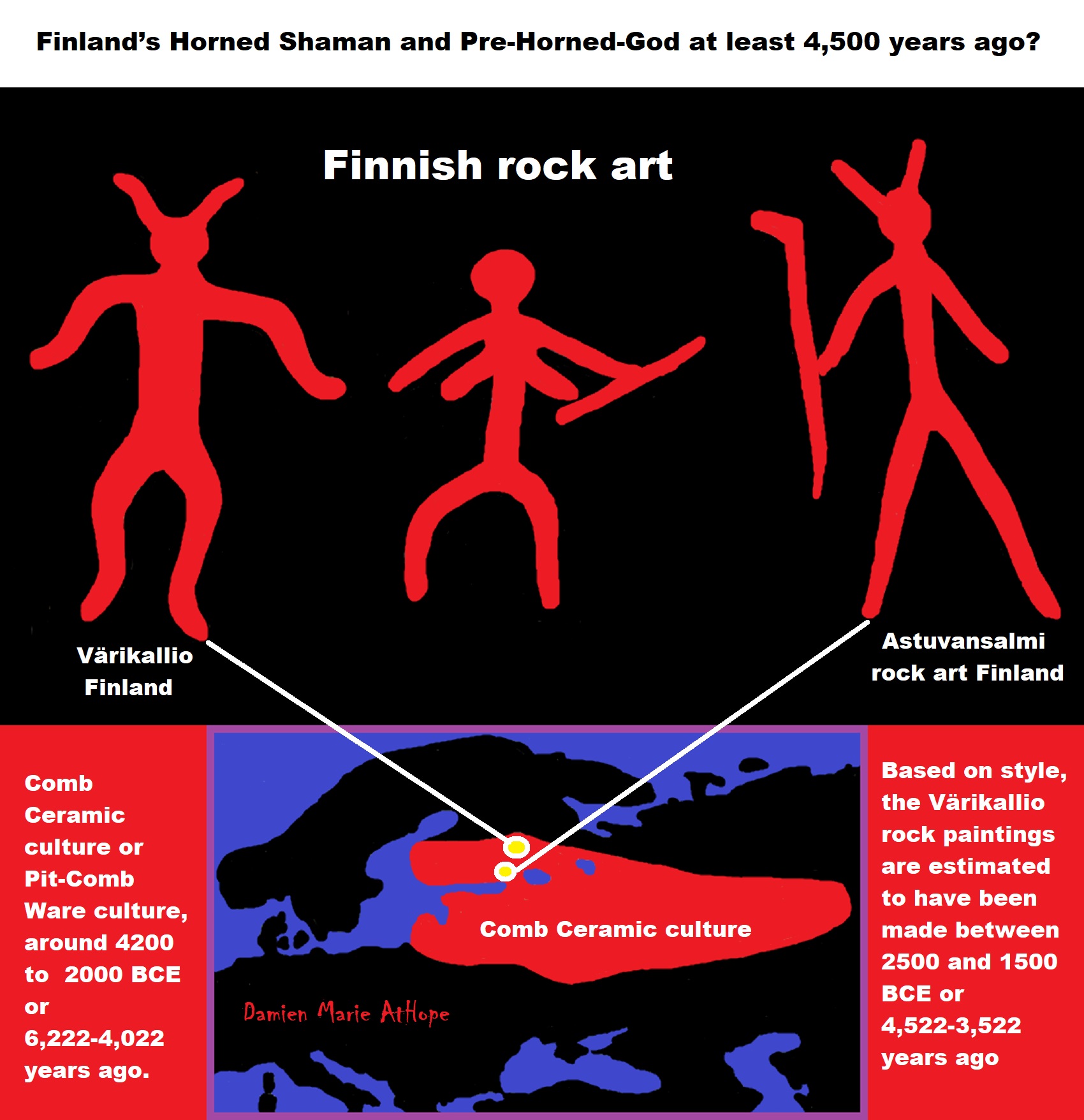

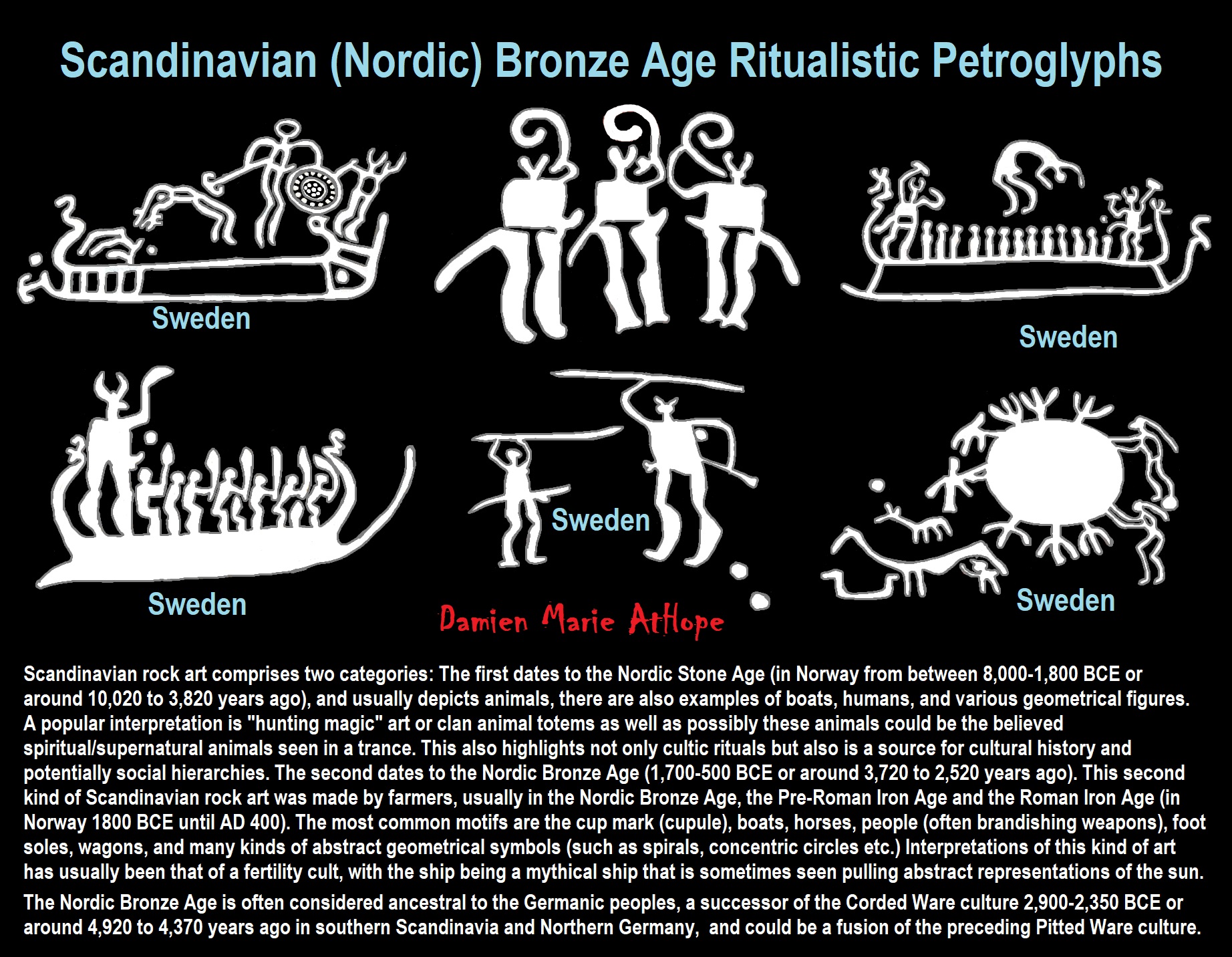

Ritual on the Rock. Reflection of Totemic Rites of the Deer Cult in the Rock Art of Northern Eurasia

“There are numerous complex scenes, including images of people and deer, among the rock paintings of Northern Europe and Siberia. Some of them can be interpreted as rituals (Alta, Glosa, Surukhtakh-Kaya, etc.). We consider them in the context of the deer cult, which developed in deer hunter societies and survived at a later time. Totemic and cosmological myths were the essence of this cult, they were inextricably linked with rituals — calendrical, which correlated with natural and economic cycles, and liminal, conditioned by the life cycle of people. Archaeological materials and rock paintings of the Mesolithic-Neolithic of Northern Europe and Northern Asia indicate that the cult of the deer played a leading role in the myths and ritual complex. We used the method of ethno-archaeological reconstruction for the interpretations of the compositions. We compared some narratives of rock carvings in Northern Europe and Siberia with totemic rites of the indigenous peoples of the subarctic zone. These ceremonies were supposed to guarantee success in hunting and, at the same time, the reproduction of deer. Imitating deer, creation of models of deer, killing of a sacrificial deer, dismemberment, joint eating and preservation of the remains for further restoration – those were the main elements of the rituals. These ritual actions are reflected in the rock art of Northern Eurasia.” ref

“Shapeshifting images run deep in human history, going back to ancient cave paintings (and to Damien, maybe some of the first carved figurines art). Oxford University archeologist Chris Gosden thinks they’re linked to the shaman’s ability to cross into the spirit world where humans and animals merge. He says animist beliefs are gaining new traction among some scientists, and they raise profound questions about the nature of consciousness.” ref

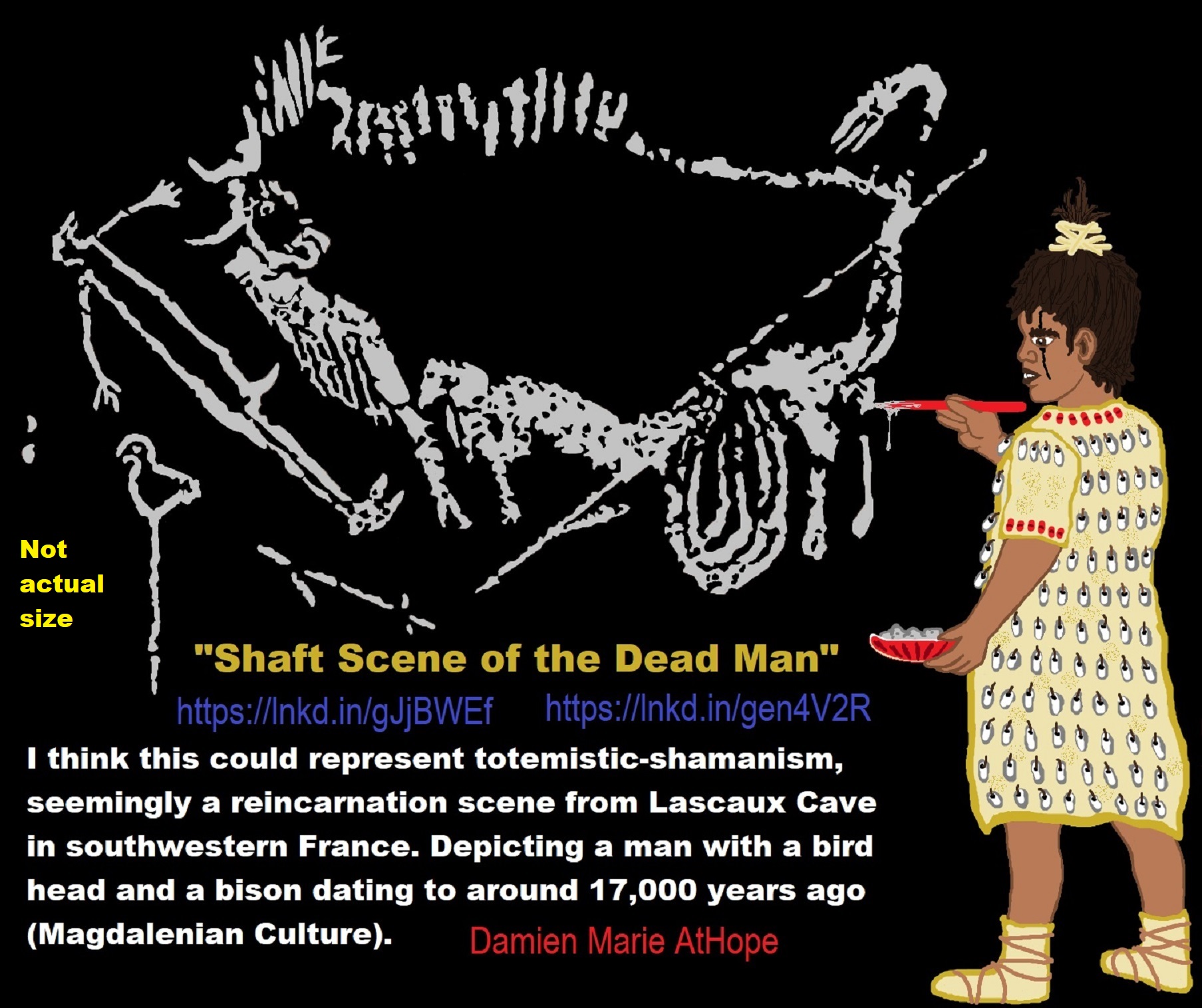

“Among the approximately 100 painted caves of Europe, a handful have enigmatic paintings of human-animal composites, or “therianthropes,” the meaning of which is and probably will remain a topic of speculation. In some cases, we know that the paintings had a special significance for the people who created them because of their location. For example, the famous “hunting accident” in the Cave of Lascaux, pictured immediately below, is painted near the bottom of a twenty-foot shaft in a remote corner of the cave, with room enough only for a single person to view it at a time. The extreme rarity of the images and the fact that they depict human beings or human-like entities also suggest their unique importance. Scholars have interpreted the images variously as sorcerers, mythic ancestors, gods, and human hunters in costume. However, if we accept David-Lewis’ interpretation of the geometric images on the walls of the Paleolithic caves, it is likely that therianthropic paintings depict shamans in states of trance. On this interpretation, the bird-headed human figure painted in the shaft at Lascaux is not the victim of a hunting accident, but a shaman whose ecstatic trance state is represented by an erect penis, hard to account for in other interpretations. The bird-headed staff, perhaps was a ritual instrument, and the bison spilling its entrails an animal spirit encountered and perhaps killed in the other world, in an act of hunting magic such as Abbe Breuil described.” ref

“For those who believe in the Magic of Shapeshifting. One of the best ways to connect with believed power animals is through the believed art of shapeshifting. In the shaman’s world, animals are kin, an ancient belief reflected in mythology and in animism – the belief that non-human entities are spiritual beings. It is a mental world where the seen and the unseen; the material and the spiritual merge. As their helping spirits, the shamans “might use animals, anything that grows,” says Osuitok Ipeelee, an esteemed Artic Inuit sculptor. “It was well known that the animals the shamans controlled had the ability to turn into humans. When a shaman was using his magic he had a real change of personality. When the animals entered into him he’d be chanting loudly; if a shaman was turning into a certain animal, he’d make that animal sound. Once he was filled inside, he’d begin to change; his face and his skin followed.” ref

“For those who believe in the Magic of Shapeshifting think it is more than just transforming into an animal as is often depicted in shamanic accounts and tales. It is the ability to shift your energies to adapt to the demands and changes of daily life. We all learn which activities, behaviors, and attitudes support or hinder our survival and growth. It is a natural and instinctual ability that we all share. The minimal development of this talent is the ability to mimic. We often mimic for the purpose of learning something or to blend in with our social or physical environment. It implies changing one’s pattern of appearance or behavior, rather than just using what you already have. Actors, for example, are known for their ability to take on the characteristics of another person or thing.” ref

“For those who believe in the Magic of Shapeshifting, they may think a shapeshifter is one who manipulates their aura to access a higher or inner power in order to grow and learn. The human aura is the energy field that surrounds the human body in all directions. All shapeshifting occurs on an energy level. If everything is broadcasting its own energy pattern and if you could match and rebroadcast the same pattern, then you would take on the appearance and qualities of the thing you were matching. The only constraining factor is the degree of belief, connection, and energy. To experience this for yourself, try the following simple exercise:

1. Create sacred space as you would for other spiritual work, dim the lights, and sit comfortably erect in a chair or on the floor.

2. Close your eyes and take a couple of deep breaths.

3. Call upon an animal that you have an affinity with. Visualize and invite this animal spirit to come into your body and consciousness.

4. Meditate with it. Be open to the feelings and sensations of being that animal. It is not uncommon to be and see the animal at the same time.

5. Simply observe whatever happens for a few minutes, and then thank the spirit animal and release it.” ref

“For those who believe in the Magic of Shapeshifting, they may think shapeshifting, to any degree will help you develop a kinship with your animal relatives. Learning to shift your consciousness, to align with and adapt your energies to power animals, opens your heart and mind to the wisdom and strength of the animal world. You must empty yourself so that the believed “spirit” can embody you. “Become like a hollow bone,” a Lakota elder once advised me in the sweat lodge.” ref

Werewolf (or other believed were-animals, such as a Were-Jaguar once believed in ancient Central and South America)

“A werecat (also written in a hyphenated form as were-cat) is an analog to “werewolf” for a feline therianthropic creature. Ailuranthropy comes from the Greek root words ailouros meaning “cat”, and anthropos, meaning “human” and refers to human/feline transformations, or to other beings that combine feline and human characteristics. Its root word ailouros is also used in ailurophilia, the most common term for a deep love of cats. Ailuranthrope is a lesser-known term that refers to a feline therianthrope. Depending on the story in question, the species involved can be a domestic cat, a tiger, a lion, a leopard, a lynx, or any other type, including some that are purely mythical felines. Werecats are increasingly featured in popular culture, although not as often as werewolves.” ref

“In folklore, a werewolf (from Old English werwulf ‘man-wolf’), or occasionally lycanthrope (from Ancient Greek λυκάνθρωπος, lykánthrōpos, ‘wolf-human’) is an individual who can shape-shift into a wolf (or, especially in modern film, a therianthropic hybrid wolf-like creature), either purposely or after being placed under a curse or affliction (often a bite or the occasional scratch from another werewolf), with the transformations occurring on the night of a full moon. Early sources for belief in this ability or affliction, called lycanthropy, are Petronius (27–66) and Gervase of Tilbury (1150–1228).” ref

“The werewolf is a widespread concept in European folklore, existing in many variants, which are related by a common development of a Christian interpretation of underlying European folklore developed during the medieval period. From the early modern period, werewolf beliefs also spread to the New World with colonialism. Belief in werewolves developed in parallel to the belief in witches, in the course of the Late Middle Ages and the early modern period. Like the witchcraft trials as a whole, the trial of supposed werewolves emerged in what is now Switzerland (especially the Valais and Vaud) in the early 15th century and spread throughout Europe in the 16th, peaking in the 17th and subsiding by the 18th century.” ref

“The persecution of werewolves and the associated folklore is an integral part of the “witch-hunt” phenomenon, albeit a marginal one, accusations of lycanthropy being involved in only a small fraction of witchcraft trials. During the early period, accusations of lycanthropy (transformation into a wolf) were mixed with accusations of wolf-riding or wolf-charming. The case of Peter Stumpp (1589) led to a significant peak in both interest in and persecution of supposed werewolves, primarily in French-speaking and German-speaking Europe. The phenomenon persisted longest in Bavaria and Austria, with persecution of wolf-charmers recorded until well after 1650, the final cases taking place in the early 18th century in Carinthia and Styria.” ref

“The Modern English werewolf descends from the Old English wer(e)wulf, which is a cognate of Middle Dutch weerwolf, Middle Low German warwulf, werwulf, Middle High German werwolf, and West Frisian waer-ûl(e). These terms are generally derived from a Proto-Germanic form reconstructed as *wira-wulfaz (‘man-wolf’), itself from an earlier Pre-Germanic form *wiro-wulpos. An alternative reconstruction, *wazi-wulfaz (‘wolf-clothed’), would bring the Germanic compound closer to the Slavic meaning, with other semantic parallels in Old Norse úlfheðnar (‘wolf-skinned’) and úlfheðinn (‘wolf-coat’), Old Irish luchthonn (‘wolf-skin’), and Sanskrit Vṛkājina (‘Wolf-skin’).” ref

“The Norse branch underwent taboo modifications, with Old Norse vargúlfr (only attested as a translation of Old French garwaf ~ garwal(f) from Marie’s lay of Bisclavret) replacing *wiraz (‘man’) with vargr (‘wolf, outlaw’), perhaps under the influence of the Old French expression leus warous ~ lous garous (modern loup-garou), which literally means ‘wolf-werewolf’. The modern Norse form varulv (Danish, Norwegian and Swedish) was either borrowed from Middle Low German werwulf, or else derived from an unattested Old Norse *varulfr, posited as the regular descendant of Proto-Germanic *wira-wulfaz. An Old Frankish form *werwolf is inferred from the Middle Low German variant and was most likely borrowed into Old Norman garwa(l)f ~ garo(u)l, with regular Germanic–Romance correspondence w- / g- (cf. William / Guillaume, Wales / Galles, etc.).” ref

“The Proto-Slavic noun *vьlko-dlakь, meaning ‘wolf-haired’ (cf. *dlaka, ‘animal hair, fur’), can be reconstructed from Serbian vukòdlak, Slovenian vołkodlȃk, and Czech vlkodlak, although formal variations in Slavic languages (*vьrdl(j)ak, *vьlkdolk, *vьlklak) and the late attestation of some forms pose difficulties in tracing the origin of the term. The Greek Vrykolakas and Romanian Vîrcolac, designating vampire-like creatures in Balkan folklores, were borrowed from Slavic languages. The same form is also found in other non-Slavic languages of the region, such as Albanian vurvolak and Turkish vurkolak. Bulgarian vьrkolak and Church Slavonic vurkolak may be interpreted as back-borrowings from Greek. The name vurdalak (вурдалак; ‘ghoul, revenant’) first appeared in Russian poet Alexander Pushkin‘s work Pesni, published in 1835. The source of Pushkin’s distinctive form remains debated in scholarship.” ref

“A Proto-Celtic noun *wiro-kū, meaning ‘man-dog’, has been reconstructed from Celtiberian uiroku, the Old Brittonic place-name Viroconium (< *wiroconion, ‘place of man-dogs, i.e. werewolves’), the Old Irish noun ferchu (‘male dog, fierce dog’), and the medieval personal names Guurci (Old Welsh) and Gurki (Old Breton). Wolves were metaphorically designated as ‘dogs’ in Celtic cultures. The modern term lycanthropy comes from Ancient Greek lukanthrōpía (λυκανθρωπία), itself from lukánthrōpos (λυκάνθρωπος), meaning ‘wolf-man’. Ancient writers used the term solely in the context of clinical lycanthropy, a condition in which the patient imagined himself to be a wolf. Modern writers later used lycanthrope as a synonym of werewolf, referring to a person who, according to medieval superstition, could assume the form of wolves.” ref

“The European motif of the devilish werewolf devouring human flesh harks back to a common development during the Middle Ages in the context of Christianity, although stories of humans turning into wolves take their roots in earlier pre-Christian beliefs. Their underlying common origin can be traced back to Proto-Indo-European mythology, where lycanthropy is reconstructed as an aspect of the initiation of the kóryos warrior class, which may have included a cult focused on dogs and wolves identified with an age grade of young, unmarried warriors. The standard comparative overview of this aspect of Indo-European mythology is McCone (1987).” ref

“Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities. It is considered to be an innate tendency of human psychology. Personification is the related attribution of human form and characteristics to abstract concepts such as nations, emotions, and natural forces, such as seasons and weather. Both have ancient roots as storytelling and artistic devices, and most cultures have traditional fables with anthropomorphized animals as characters. People have also routinely attributed human emotions and behavioral traits to wild as well as domesticated animals. From the beginnings of human behavioral modernity in the Upper Paleolithic, about 40,000 years ago, examples of zoomorphic (animal-shaped) works of art occur that may represent the earliest known evidence of anthropomorphism. One of the oldest known is an ivory sculpture, the Löwenmensch figurine, Germany, a human-shaped figurine with the head of a lioness or lion, determined to be about 32,000 years old. It is not possible to say what these prehistoric artworks represent. A more recent example is The Sorcerer, an enigmatic cave painting from the Trois-Frères Cave, Ariège, France: the figure’s significance is unknown, but it is usually interpreted as some kind of great spirit or master of the animals. In either case there is an element of anthropomorphism.” ref

“In religion and mythology, anthropomorphism is the perception of a divine being or beings in human form, or the recognition of human qualities in these beings. Ancient mythologies frequently represented the divine as deities with human forms and qualities. They resemble human beings not only in appearance and personality; they exhibited many human behaviors that were used to explain natural phenomena, creation, and historical events. The deities fell in love, married, had children, fought battles, wielded weapons, and rode horses and chariots. They feasted on special foods, and sometimes required sacrifices of food, beverage, and sacred objects to be made by human beings. Some anthropomorphic deities represented specific human concepts, such as love, war, fertility, beauty, or the seasons. Anthropomorphic deities exhibited human qualities such as beauty, wisdom, and power, and sometimes human weaknesses such as greed, hatred, jealousy, and uncontrollable anger.” ref

“Greek deities such as Zeus and Apollo often were depicted in human form exhibiting both commendable and despicable human traits. Anthropomorphism in this case is, more specifically, anthropotheism. From the perspective of adherents to religions in which humans were created in the form of the divine, the phenomenon may be considered theomorphism, or the giving of divine qualities to humans. Anthropomorphism has cropped up as a Christian heresy, particularly prominently with Audianism in third-century Syria, but also fourth-century Egypt and tenth-century Italy. This often was based on a literal interpretation of the Genesis creation myth: “So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.” ref

“European folklore usually depicts werecats as people who transform into domestic cats. Some European werecats became giant domestic cats or panthers. They are generally labeled witches, even though they may have no magical ability other than self-transformation. During the witch trials, all shapeshifters, including werewolves, were considered witches whether they were male or female.” ref

“African legends describe werelions, werepanthers or wereleopards. In the case of leopards, this is often because the creature is really a leopard deity masquerading as a human. When these gods mate with humans, offspring can be produced, and these children sometimes grow up to be shapeshifters; those who do not transform may instead have other powers. In reference to werecats who turn into lions, the ability is often associated with royalty. Such a being may have been a king or queen in a former life.” ref

“In Africa, there are folk tales that speak of the “Nunda,” or the “Mngwa,” a big cat of immense size that stalks villages at night. Many of these tales say it is more ferocious than a lion and more agile than a leopard. The Nunda are believed by some to be a variation of therianthrope that, by day, is a human, but by night becomes the werecat. No actual evidence of such a creature existing has ever been documented, but in 1938 a British administrator named William Hitchens, working in Tanzania, was told by locals that a monstrous cat had been attacking people at night. Huge paw prints were found to be much larger than any known big-cat, but Hitchens dismissed the case, believing it more likely to be a lion with gigantism.” ref

“Mainland Asian werecats usually become tigers. In India, the weretiger is often a dangerous sorcerer, portrayed as a menace to livestock, who might at any time turn to man-eating. These tales travelled through the rest of India and into Persia through travellers who encountered the royal Bengal tigers of India and then further west. Chinese legends often describe weretigers as the victims of either a hereditary curse or a vindictive ghost. Alternatively, the ghosts of people who had been killed by tigers could become a malevolent supernatural being known as “Chang” (伥), devoting all their energy to making sure that tigers killed more humans. Some of these ghosts were responsible for transforming ordinary humans into man-eating weretigers. Also, in Japanese folklore there are creatures called bakeneko that are similar to kitsune (fox spirits) and bake-danuki (Japanese raccoon dog spirits). In Thailand a tiger that eats many humans may become a weretiger. There are also other types of weretigers, such as sorcerers with great powers who can change their form to become animals.” ref

“In both present-day Indonesia and Malaysia there is another kind of weretiger, known as Harimau jadian. Linguist and writer Zainal Abidin bin Ahmad for example has compiled oral stories of a famous weretiger named Dato’ Paroi fabled to have led the flock of all tigers that roamed in his home area of Negeri Sembilan. In Malaysia too, Bajangs have been described as vampiric or demonic werecats. The Kerinchi Malays of Sumatra were reputed to have the ability to transform into weretigers.” ref

“In the central area of the Indonesian island of Java the power of transformation is regarded as due to inheritance, to the use of spells, to fasting and willpower, to the use of charms, etc. Save when it is hungry or has just cause for revenge it is not hostile to man; in fact, it is said to take its animal form only at night and to guard the plantations from wild pigs. Variants of this belief assert that the shapeshifter does not recognize his friends unless they call him by name, or that he goes out as a mendicant and transforms himself to take vengeance on those who refuse him alms. Somewhat similar is the belief of the Khonds; for them the tiger is friendly, and he reserves his wrath for their enemies. A man is said to take the form of a tiger in order to wreak a just vengeance.” ref

“The foremost were-animal in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures was the were-jaguar. It was associated with the veneration of the jaguar, with priests and shamans among the various peoples who followed this tradition, wearing the skins of jaguars to “become” a were-jaguar. Among the Aztecs, an entire class of specialized warriors who dressed in the jaguar skins were called “jaguar warriors” or “jaguar knights”. Depictions of the jaguar and the were-jaguar are among the most common motifs among the artifacts of the ancient Mesoamerican civilizations.” ref

“N. W. Thomas wrote in the 11th ed. of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1911) that, according to Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (1794–1868), the kanaima was a human being who employed poison to carry out his function of blood avenger, and that other authorities represent the kanaima as a jaguar, which was either an avenger of blood or the familiar of a cannibalistic sorcerer. He also mentioned that in 1911 some Europeans in Brazil believed that the seventh child of the same sex in unbroken succession becomes a were-man or woman, and takes the form of a horse, goat, jaguar, or pig.” ref

“In the US, urban legends tell of encounters with feline bipeds; beings similar to the Bigfoot having cat heads, tails, and paws. Feline bipeds are sometimes classified as part of cryptozoology, but more often they are interpreted as werecats. Assertions that werecats truly exist and have an origin in supernatural or religious realities have been common for centuries, with these beliefs often being hard to entirely separate from folklore. In the 19th century, occultist J. C. Street asserted that material cat and dog transformations could be produced by manipulating the “ethereal fluid” that human bodies are supposedly floating in. The Catholic witch-hunting manual, the Malleus Maleficarum, asserted that witches can turn into cats, but that their transformations are illusions created by demons. New Age author John Perkins asserted that every person has the ability to shapeshift into “jaguars, bushes, or any other form” by using mental power. Occultist Rosalyn Greene claims that werecats called “cat shifters” exist as part of a “shifter subculture” or underground New Age religion based on lycanthropy and related beliefs.” ref

Shamanism and Dogs?

Yekyua “Mother Animal”

“A Yekyua or “mother animal” is a class of Yakut spirits that remain hidden until the snow melts in the Spring. The Yakuts are a Turkic people. Each yekyua is associated with a particular animal. They act as familiar spirits to protect Yakut shamans. They are dangerous and powerful. The most dangerous are attached to female shamans. The type of animal determines the strength of the yekyua. For example, dog yekyua have little power, while elk yekyua do. Only shaman can see yekyua. When a shaman puts his/her spirit into his yekyua, he/she is dependent on his animal part. If another shaman who has manifested his animal kills the animal of another, the shaman with the dead animal dies. When the yekyua are fighting in the spring, the shaman with which they are associated feel ill. Dog yekyua are not prized as they gnaw at the shaman and destroy his body, bringing him sickness. Ordinarily, a good yekyua protects the shaman.” ref

“Throughout history dogs have been known as guardians, protectors and most importantly – MANS BEST FRIEND. Dog was the servant/soldier that guarded the tribe’s abodes, protecting them from surprise attacks. His keen sense of smell and acute hearing alerted his master of dangers. He also assisted when hunting and provided warmth in winter. The dogs medicine is loyalty, reliability, nobleness, trustworthiness, unconditional love, friendship, fierce energy of protection and service. People who have Dog as power animal are usually helping others or serving humanity in some way and have a deep understanding and compassion of human shortcomings. Dog serves selflessly, never asking for their service to be praised or anything in return. Dogs can be both sensitive and intelligent. From a dog we can learn the true meaning of unconditional love and forgiveness. Domestic dogs are faithful companions to humans with a strong sense to serve. Their ability to love even when abused is incredible. The belief in psychic gifts has been associated with Dog because of his talent to pick up on subtle energy frequencies generally unknown to mankind. Like other animals, they can feel for instance if an earthquake is about to occur, and can lead us to safety, if we trust them like they trust us. A dog’s behavior often mirrors the personality of its owner. If you own a dog, they are constantly observing you and his/her interaction with you. They then anticipate your next move, serving as a mirror image of who you truly are. The dog is a great teacher for those who wish to learn.” ref

Dogs in Ancient China

“Remains of dogs and pigs have been found in the oldest Neolithic settlements of the Yangshao (circa 4000 BCE or around 6,000 years ago) and Hemudu (circa 5000 BCE or around 7,000 years ago) cultures. Canine remains similar to the Dingo have been found in some early graves excavated in northern China. Tests on neolithic dog bones show similarities between dogs from this era and modern-day Japanese dogs, especially the shiba inu. Dogs (Canis lupus familiaris), known in Classical Chinese as quan (Chinese: 犬; pinyin: quǎn; Wade–Giles: ch’üan), played an important role in ancient Chinese society. According to Bruno Schindler, the origin of using dogs as sacrificial animals dates back to a primitive cult in honor of a dog-shaped god of vegetation whose worship later became amalgamated with that of Shang Di, the reigning deity of the Shang pantheon.” ref

“Systematic excavation of Shang tombs around Anyang since 1928 have revealed a large number of animal and human sacrifices. There was hardly a tomb or a building consecrated without the sacrifice of a dog. At one site, Xiaotong, the bones of a total of 825 human victims, 15 horses, 10 oxen, 18 sheep, and 35 dogs were unearthed. Dogs were usually buried wrapped in reed mats and sometimes in lacquer coffins. Small bells with clappers, called ling (鈴) have sometimes been found attached to the necks of dogs or horses. The fact that alone among domestic animals dogs and horses were buried demonstrates the importance of these two animals to ancient Chinese society. It’s reflected in an idiom passed down to modern times: “to serve like a dog or a horse.” (犬馬之勞). According to ancient folk legends, solar eclipses take place because dogs in heaven eat the sun. In order to save the sun from demise, ancient people formed the habit of beating drums and gongs at the critical moment to drive away the dogs.” ref

“Shang oracle bones mention questions concerning the whereabouts of lost dogs. They also refer to the ning (寧) rite during which a dog was dismembered to placate the four winds or honor the four directions. This sacrifice was carried over into Zhou times. The Erya records a custom to dismember a dog to “bring the four winds to a halt.” (止風). Other ceremonies involving dogs are mentioned in the Zhou li. In the nan (難) sacrifice to drive away pestilence, a dog was dismembered and his remains were buried in front of the main gates of the capital. The ba (軷) sacrifice to ward off evil required the Son of Heaven, riding in a jade chariot, to crush a dog under the wheels of his carriage. The character ba gives a clue as to how the ceremony took place. It is written with the radical for chariot (車) and a phonetic element which originally meant an animal whose legs had been bound (发). It was the duty of a specially appointed official to supply a dog of one color and without blemishes for the sacrifice. The blood of dogs was used for the swearing of covenants between nobles.” ref

“Towards the late fifth century BCE, surrogates began to be used for sacrifice in lieu of real dogs. The Dao De Jing mentions the use of straw dogs as a metaphor: “Haven and earth are ruthless, and treat the myriad creatures as straw dogs; the sage is ruthless, and treats the people as straw dogs.” However, the practice of burying actual dogs by no means died out. One Zhongshan royal mausoleum, for example, included two hunting dogs with gold and silver neck rings. Later, clay figurines of dogs were buried in tombs. Large quantities of these sculptures have been unearthed from the Han dynasty onwards. Most show sickle-shaped tails not unlike the modern shiba inu or akita inu. Dogs are an important motif in Chinese mythology. These motifs include a particular dog which accompanies a hero, the dog as one of the twelve totem creatures for which years are named, a dog giving first provision of grain which allowed current agriculture, and claims of having a magical dog as an original ancestor in the case of certain ethnic groups.” ref, ref

“Chinese mythology includes myths in Chinese and other languages, as transmitted by Han Chinese as well as other ethnic groups (of which fifty-six are officially recognized by the current administration of China). In the study of historical Chinese culture, many of the stories that have been told regarding characters and events which have been written or told of the distant past have a double tradition: one which tradition which presents a more historicized and one which presents a more mythological version. This is also true of some accounts related to mythological dogs in China. Historical accounts and anecdotes about dogs from ancient China and onwards exist in extant literary works, for example in the Shiji, by Sima Qian. Archaeological study provides substantial backing and supplemental knowledge in this regard.” ref

“For thousands of years, a twelve-year cycle named after various real or mythological animals has been used in Southeast Asia. This twelve-year cycle, sometimes referred to as the “Chinese zodiac,” associates each year in turn with a certain creature, in a fixed order of twelve animals, after which it returns to the first in the order, the Rat. The eleventh in the cycle is the Dog. One account is that the order of the beings-of-the-year is due to their order in a racing contest involving swimming across a river, in the Great Race. The reason for the Dog finishing the race second from last despite generally being a talented swimmer is explained as being due to its playful nature: the Dog played and frolicked along the way, thus delaying completing the course and reaching the finishing line. Other members of the canidae family also figure in Chinese mythology, including wolves and foxes. The portrayal of these is usually quite different than in the case of dogs. Tales and literature on foxes is especially extensive, with foxes often having magical qualities, such as being able to shift back and forth to human shape, live for incredible life spans, and to grow supernumerary tails (nine being common).” ref

“The personalities of people born in Dog years are popularly supposed to share certain attributes associated with Dogs, such as loyalty or exuberance; however, this would be modified according to other considerations of Chinese astrology, such as the influences of the month, day, and hour of birth, according to the traditional system of Earthly Branches, in which the zodiacal animals are also associated with the months and times of the day (and night), in twelve two-hour increments. The Hour of the Dog is 7 to 9 p.m. and the Dog is associated with the ninth lunar month. There are various myths and legends in which various ethnic groups claimed or were claimed to have had a divine dog as a forebear, one of these is the story of Panhu. The legendary Chinese sovereign Di Ku has been said to have a dog named Panhu. Panhu helped him win a war by killing the enemy general and bringing him his head and ended up with marriage to the emperor’s daughter as a reward.” ref

“The dog carried his bride to the mountainous region of the south, where they produced numerous progeny. Because of their self-identification as descendants from these original ancestors, Panhu has been worshiped by the Yao people and the She people, often as King Pan, and the eating of dog meat tabooed. This ancestral myth is also has been found among the Miao people and Li people. An early documentary source for the Pan-hu origin myth is by the Jin dynasty (266–420) author Gan Bao, who records this origin myth for a southern (that is, south of the Yangzi River) ethnic group which he refers to as “Man” (蠻). There are various variations of the Panhu mythology. According to one version, the Emperor had promised his daughter in marriage as a reward to the one who brought back the enemy general’s head, but due to the perceived difficulties of a dog marriage with a human bride (especially an imperial princess), the dog proposed to magically turn into a human being, by means of a process in which he would be sequestered beneath a bell for 280 days.” ref

“One of the stock heroic supernatural beings with mighty martial prowess in Chinese culture is Erlang, a character in Journey to the West. Erlang has been said to have a dog. In the epic novel, Journey to the West Erlang’s dog helps him in his fight against the evolved-monkey hero, Sun Wukong, critically biting him on the leg. Later on in the story (Chapter 63), Sun Wukong with Erlang (now both on the same side) and their companions-in-fight battle against a Nine-headed Insect monster, when, again, Erlang’s small hound comes to the rescue and defeats by biting off the monster’s retractable head, which popped in and out of its torso: the monster then flees, dripping blood, off into the unknown.” ref

“The author of the Journey to the West comments that this is the origin of the “nine-headed blood-dripping bird”, and that this trait was passed on to its descendant. Anthony C. Yu, editor and translator of Journey to the West associates this bird with the ts’ang kêng of Chinese mythology. The Tiangou (“Heavenly Dog”) has been said to resemble a black dog or meteor, which is thought to eat the sun or moon during an eclipse, unless frightened away. According to the myths of various ethnic groups, a dog provided humans with the first grain seeds enabling the seasonal cycle of planting, harvesting, and replanting staple agricultural products by saving some of the seed grains to replant, thus explaining the origin of domesticated cereal crops. This myth is common to the Buyi, Gelao, Hani, Miao, Shui, Tibetan, Tujia, and Zhuang peoples.” ref

“A version of this myth collected from ethnic Tibetan people in Sichuan tells that in ancient times grain was tall and bountiful, but that rather than being duly grateful for the plenty that people even used it for personal hygiene after defecation, which so angered the God of Heaven that he came down to earth to repossess it all. However, a dog grasped his pant leg, piteously crying, and so moving God of Heaven to leave a few seeds from each type of grain with the dog, thus providing the seed stock of today’s crops. Thus it is said that because humans owe their possession of grain seed stocks to a dog, people should share some of their food with dogs. Another myth, of the Miao people, recounts the time of the distantly remote era when dogs had nine tails, until a dog went to steal grains from heaven, and lost eight of its tails to the weapons of the heavenly guards while making its escape, but bringing back grain seeds stuck onto its surviving tail. According to this, when Miao people hold their harvest celebration festival, the dogs are the first to be fed.(Yang 2005: 54) The Zhuang and Gelao peoples have a similar myth explaining why it is that the ripe heads of grain stalks are curly, bushy, and bent – just so as is the tail of a dog.” ref

“In northern China, dog images made by cutting paper were thrown in the water as part of the ritual of the Double Fifth (Duanwu Festival) holiday, celebrated on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month, as an apotropaic magic act meant to drive away evil spirits. Paper dogs were also provided for protecting the dead. Numerous statuary of Chinese guardian lions exist, which are often called “Fu Dogs” “Foo Dogs“, “Fu Lions“, “Fo Lions“, and “Lion Dogs“. Modern lions are not native in the area of China, except perhaps the extreme west; however, their existence was well known, and associated symbolism and ideas about lions were familiar; however, in China, artistic representations of lions tended to be dog-like. Indeed, “[t]he ‘lion’ which we see depicted in Chinese paintings and in sculpture bears little resemblance to the real animal, which, however, plays a big part in Chinese folklore.” The reasons for referencing “guardian lions” as “dogs” in Western cultures may be obscure, however, the phenomenon is well known.” ref

“Dogs have played a role in the religion, myths, tales, and legends of many cultures. In mythology, dogs often serve as pets or as watchdogs. Stories of dogs guarding the gates of the underworld recur throughout Indo-European mythologies and may originate from Proto-Indo-European religion. Historian Julien d’Huy has suggested three narrative lines related to dogs in mythology. One echoes the gatekeeping noted above in Indo-European mythologies—a linkage with the afterlife; a second “related to the union of humans and dogs”; a third relates to the association of dogs with the star Sirius. Evidence presented by d’Huy suggests a correlation between the mythological record from cultures and the genetic and fossil record related to dog domestication.” ref

“The Ancient Egyptians are often more associated with cats in the form of Bastet, but dogs are found to have a sacred role and figure as an important symbol in religious iconography. Dogs were associated with Anubis, the jackal headed god of the underworld. At times throughout its period of being in use the Anubieion catacombs at Saqqara saw the burial of dogs. Anput was the female counterpart of her husband, Anubis; she was often depicted as a pregnant or nursing jackal, or as a jackal wielding knives. Other dogs can be found in Egyptian mythology. Am-heh was a minor god from the underworld. He was depicted as a man with the head of a hunting dog who lived in a lake of fire. Duamutef was originally represented as a man wrapped in mummy bandages. From the New Kingdom onwards, he is shown with the head of a jackal. Wepwawet was depicted as a wolf or a jackal, or as a man with the head of a wolf or a jackal. Even when considered a jackal, Wepwawet usually was shown with grey, or white fur, reflecting his lupine origins. Khenti-Amentiu was depicted as a jackal-headed deity at Abydos in Upper Egypt, who stood guard over the city of the dead.” ref

“Dogs were closely associated with Hecate in the Classical world. Dogs were sacred to Artemis and Ares. Cerberus is a three-headed, dragon-tailed watchdog who guards the gates of Hades. Laelaps was a dog in Greek mythology. When Zeus was a baby, a dog, known only as the “golden hound” was charged with protecting the future King of Gods. In Homer‘s epic poem the Odyssey, when the disguised Odysseus returns home after 20 years, he is recognized only by his faithful dog, Argos, who has been waiting all this time for his return.” ref

“In Hindu mythology, Yama, the god of death, owns two watchdogs who have four eyes. They are said to watch over the gates of Naraka. The hunter god Muthappan from the North Malabar region of Kerala has a hunting dog as his mount. Dogs are found in and out of the Muthappan Temple and offerings at the shrine take the form of bronze dog figurines. The dog (Shvan) is also the vahana or mount of the Hindu god Bhairava. Yudhishthira had approached heaven with his dog who was the god Yama himself. Dogs are also shown in the background in the iconography of Hindu deities like Dattatreya, many times dogs are also shown in the background in the iconography of deities like Khandoba. In Valmiki Ramayana there’s a tale about a dog receiving justice, passed by king Rama.” ref

“In ancient Mesopotamia, from the Old Babylonian period until the Neo-Babylonian, dogs were the symbol of Ninisina, the goddess of healing and medicine, and her worshippers frequently dedicated small models of seated dogs to her. In the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian periods, dogs were used as emblems of magical protection. There is a temple in Isin, Mesopotamia, named é-ur-gi7-ra which translates as “dog house”. Enlilbani, a king from the Old Babylonian First Dynasty of Isin, commemorated the temple to the goddess Ninisina. Although there is a small amount of detail known about it, there is enough information to confirm that a dog cult did exist in this area. Usually, dogs were only associated with the Gula cult, but there is some information, like Enlilbani’s commemoration, to suggest that dogs were also important to the cult of Ninisina, as Gula was another goddess who was closely associated to Ninisina. More than 30 dog burials, numerous dog sculptures, and dog drawings were discovered when the area around this Ninisina temple was excavated. In the Gula cult, the dog was used in oaths and was sometimes referred to as a divinity.” ref

“In Persian mythology, two four-eyed dogs guard the Chinvat Bridge. During archaeological diggings, the Ashkelon dog cemetery was discovered in the layer dating from when the city was part of the Persian Empire. It is believed the dogs may have had a sacred role – however, evidence for this is not conclusive. In Zoroastrianism, the dog is regarded as an especially beneficent, clean and righteous creature, which must be fed and taken care of. The dog is praised for the useful work it performs in the household, but it is also seen as having special spiritual virtues. Dogs are associated with Yama who guards the gates of afterlife with his dogs just like Hinduism. A dog’s gaze is considered to be purifying and to drive off daevas (demons). It is also believed to have a special connection with the afterlife: the Chinwad Bridge to Heaven is said to be guarded by dogs in Zoroastrian scripture, and dogs are traditionally fed in commemoration of the dead. Ihtiram-i sag, “respect for the dog”, is a common injunction among Iranian Zoroastrian villagers.” ref

“In Norse mythology, a bloody, four-eyed dog called Garmr guards Helheim. Also, Fenrir is a giant wolf who is a child of the Norse god Loki, who was foretold to kill Odin in the events of Ragnarok. In Welsh mythology, Annwn is guarded by Cŵn Annwn.” ref

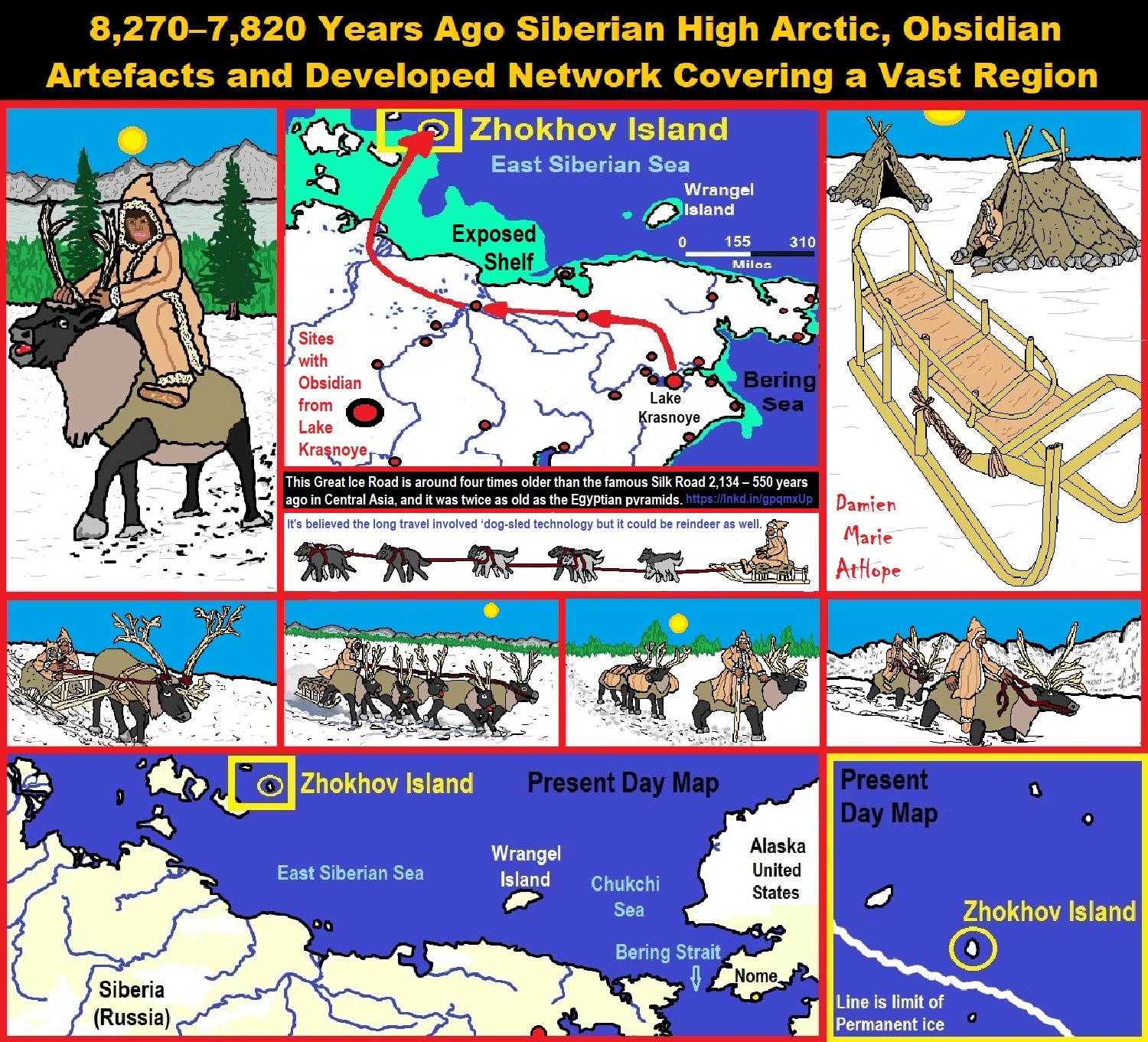

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy“, the remains of an individual who lived during the Last Glacial Maximum, 24,000 years ago in central Siberia. Populations genetically similar to MA-1 were an important genetic contributor to Native Americans, Europeans, Ancient Central Asians, South Asians, and some East Asian groups (such as the Ainu people), in order of significance.” ref

“Groups partially derived from the Ancient North Eurasians: Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (R1a-M417, around 8,400 years ago), Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (around 8,000 years ago), Ancient Beringian/Ancestral Native American (around 11,500 years ago), West Siberian Hunter-Gatherer, Western Steppe Herders (closely related to the Yamnaya culture), Late Upper Paeolithic Lake Baikal (14,050-13,770 years ago), Lake Baikal Holocene (around 11,650 years ago to the present), Jōmon people, pre-Neolithic population of Japan (and present-day Ainu people).” ref

“Since the term ‘Ancient North Eurasian’ refers to a genetic bridge of connected mating networks, scholars of comparative mythology have argued that they probably shared myths and beliefs that could be reconstructed via the comparison of stories attested within cultures that were not in contact for millennia and stretched from the Pontic–Caspian steppe to the American continent.” ref

“For instance, the mytheme of the dog guarding the Otherworld possibly stems from an older Ancient North Eurasian belief, as suggested by similar motifs found in Indo-European, Native American, and Siberian mythology. In Siouan, Algonquian, Iroquoian, and in Central and South American beliefs, a fierce guard dog was located in the Milky Way, perceived as the path of souls in the afterlife, and getting past it was a test. The Siberian Chukchi and Tungus believed in a guardian-of-the-afterlife dog and a spirit dog that would absorb the dead man’s soul and act as a guide in the afterlife. In Indo-European myths, the figure of the dog is embodied by Cerberus, Sarvarā, and Garmr. Anthony and Brown note that it might be one of the oldest mythemes recoverable through comparative mythology.” ref

“A second canid-related series of beliefs, myths, and rituals connected dogs with healing rather than death. For instance, Ancient Near Eastern and Turkic–Kipchaq myths are prone to associate dogs with healing and generally categorized dogs as impure. A similar myth-pattern is assumed for the Eneolithic site of Botai in Kazakhstan, dated to 3500 BC, which might represent the dog as absorber of illness and guardian of the household against disease and evil. In Mesopotamia, the goddess Nintinugga, associated with healing, was accompanied or symbolized by dogs. Similar absorbent-puppy healing and sacrifice rituals were practiced in Greece and Italy, among the Hittites, again possibly influenced by Near Eastern traditions.” ref

“Koryaks (Russian: коряки) are an Indigenous people of the Russian Far East, who live immediately north of the Kamchatka Peninsula in Kamchatka Krai and inhabit the coastlands of the Bering Sea. The cultural borders of the Koryaks include Tigilsk in the south and the Anadyr basin in the north. The Koryaks are culturally similar to the Chukchis of extreme northeast Siberia. The Koryak language and Alutor (which is often regarded as a dialect of Koryak), are linguistically close to the Chukchi language. All of these languages are members of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan language family. They are more distantly related to the Itelmens on the Kamchatka Peninsula. All of these peoples and other, unrelated minorities in and around Kamchatka are known collectively as Kamchadals.” ref

“The origin of the Koryak is unknown. Anthropologists have speculated that a land bridge connected the Eurasian and North American continent during Late Pleistocene. It is possible that migratory peoples crossed the modern-day Koryak land en route to North America. Scientists have suggested that people traveled back and forth between this area and Haida Gwaii before the ice age receded. They theorize that the ancestors of the Koryak had returned to Siberian Asia from North America during this time. Cultural and some linguistic similarity exist between the Nivkh and the Koryak. Families usually gathered into groups of six or seven, forming bands. The nominal chief had no predominating authority, and the groups relied on consensus to make decisions, resembling common small group egalitarianism.” ref

“The inland Koryak rode reindeer to get around, cutting off their antlers to prevent injuries. They also fitted a team of reindeer with harnesses and attached them to sleds to transport goods and people when moving camp. Koryaks believe in a Supreme Being whom they call by various names: ŋajŋənen (Universe/World), ineɣitelʔən (Supervisor), ɣət͡ɕɣoletənvəlʔən (Master-of-the-Upper-World), ɣət͡ɕɣolʔən (One-on-High), etc. He is considered to reside in Heaven with his family and when he wishes to punish mankind for immoral acts, he falls asleep and thus leaves man vulnerable to unsuccessful hunting and other ills. Koryak mythology centers on the supernatural shaman Quikil (Big-Raven), who was created by the Supreme Being as the first man and protector of the Koryak. Big Raven myths are also found in Southeast Alaska in the Tlingit culture, and among the Haida, Tsimshian, and other natives of the Pacific Northwest Coast Amerindians.” ref

“Archeologists have uncovered evidence of sled dogs during thousand year old excavations in the Kamchatka Peninsula. Early 18th century writers report the abundance of sled dogs in the region and local dependence on sled dogs for transportation. However, the Kamchatka sled dog was also used for clothing and spiritual purposes by the native Koryak people. Koryaks believe that the door to the afterlife was guarded by dogs which had to be bribed to allow the newly deceased to pass through. Prior to the introduction of reindeer, Kamchatka sled dogs were allowed to roam freely during the summer to find their own food. With the introduction of reindeer, the dogs needed to be tied up during the summers, creating a dependency on humans for feeding. While generally the Chukotka sled dog is considered the progenitor of the Siberian huskies, it is theorized that the Kamchatka sled dog may also have been intermingled, contributing the characteristic blue eyes seen in Siberian huskies but which are not standard in Chukotka sled dogs.” ref

Koryak Dog Sacrifices

“The Koryak people impaled dogs on a post as an offering to local spirits. Spiritual forces in traditional Koryak religion are associated with a particular geography, like a region, a hill, or even a house. Spirits from one place had to be kept separate from spirits associated with other places, therefore visitors would be “cleansed” by a brief ritual involving smoke and a few words. A spiritually “charged” drum used for shamanic healing was not carried from house to house by an individual shaman, but rather each household had a drum associated with the spirits of that place, which a shaman would use to talk to the spirits and heal a sick person. Scholars often refer to this kind of shamanic activity as “familial shamanism.” Each family had a person who was skilled in drumming and had some influence with spirits, and he or she would heal family and friends. Professional shamans, like those known among the Evenk (Tungus) or Sakha (Yakut) were unknown among Koryaks.” ref

“The sacrifice of nearly a whole team of dogs by coastal Koryaks (indigenous people of Siberia), was made in early spring to ensure the success of the new hunting season. The dogs are hung from poles stuck in the snow in front of a Koryak semi–dugout house.” ref

“Laikas are aboriginal spitz from Northern Russia, especially Siberia but also sometimes expanded to include Nordic hunting breeds. Laika breeds are primitive dogs who flourish with minimal care even in hostile weather. Generally, laika breeds are expected to be versatile hunting dogs, capable of hunting game of a variety of sizes by treeing small game, pointing and baying larger game, and working as teams to corner bear and boar. However, a few laikas have specialized as herding or sled dogs. Indeed the word laika is often used to refer not only to hunting dogs but also to the related sled dog breeds of the tundra belt, which the FCI classifies as “Nordic Sled Dogs” and even occasionally all spitz breeds.” ref

“Modern Siberian dog ancestry was shaped by several thousand years of Eurasian-wide trade and human dispersal. The Siberian Arctic has witnessed numerous societal changes since the first known appearance of dogs in the region ∼10,000 years ago. Dogs have been essential to life in the Siberian Arctic for over 9,500 years ago, and this tight link between people and dogs continues in Siberian communities. Although Arctic Siberian groups such as the Nenets received limited gene flow from neighboring groups, archaeological evidence suggests that metallurgy and new subsistence strategies emerged in Northwest Siberia around 2,000 years ago. It is unclear if the Siberian Arctic dog population was as continuous as the people of the region or if instead admixture occurred, possibly in relation to the influx of material culture from other parts of Eurasia. To address this question, we sequenced and analyzed the genomes of 20 ancient and historical Siberian and Eurasian Steppe dogs. Our analyses indicate that while Siberian dogs were genetically homogenous between 9,500 to 7,000 years ago, the later introduction of dogs from the Eurasian Steppe and Europe led to substantial admixture. This is clearly the case in the Iamal-Nenets region (Northwestern Siberia) where dogs from the Iron Age period (∼2,000 years ago) possess substantially less ancestry related to European and Steppe dogs than dogs from the medieval period (∼1,000 years ago). These changes include the introduction of ironworking ∼2,000 years ago and the emergence of reindeer pastoralism ∼800 years ago. The analysis of 49 ancient dog genomes reveals that the ancestry of Arctic Siberia dogs shifted over the last 2,000 years due to an influx of dogs from the Eurasian Steppe and Europe. Combined with genomic data from humans and archaeological evidence, our results suggest that though the ancestry of human populations in Arctic Siberia did not change over this period, people there participated in trade with distant communities that involved both dogs and material culture.” ref

Some Important Dog Sites

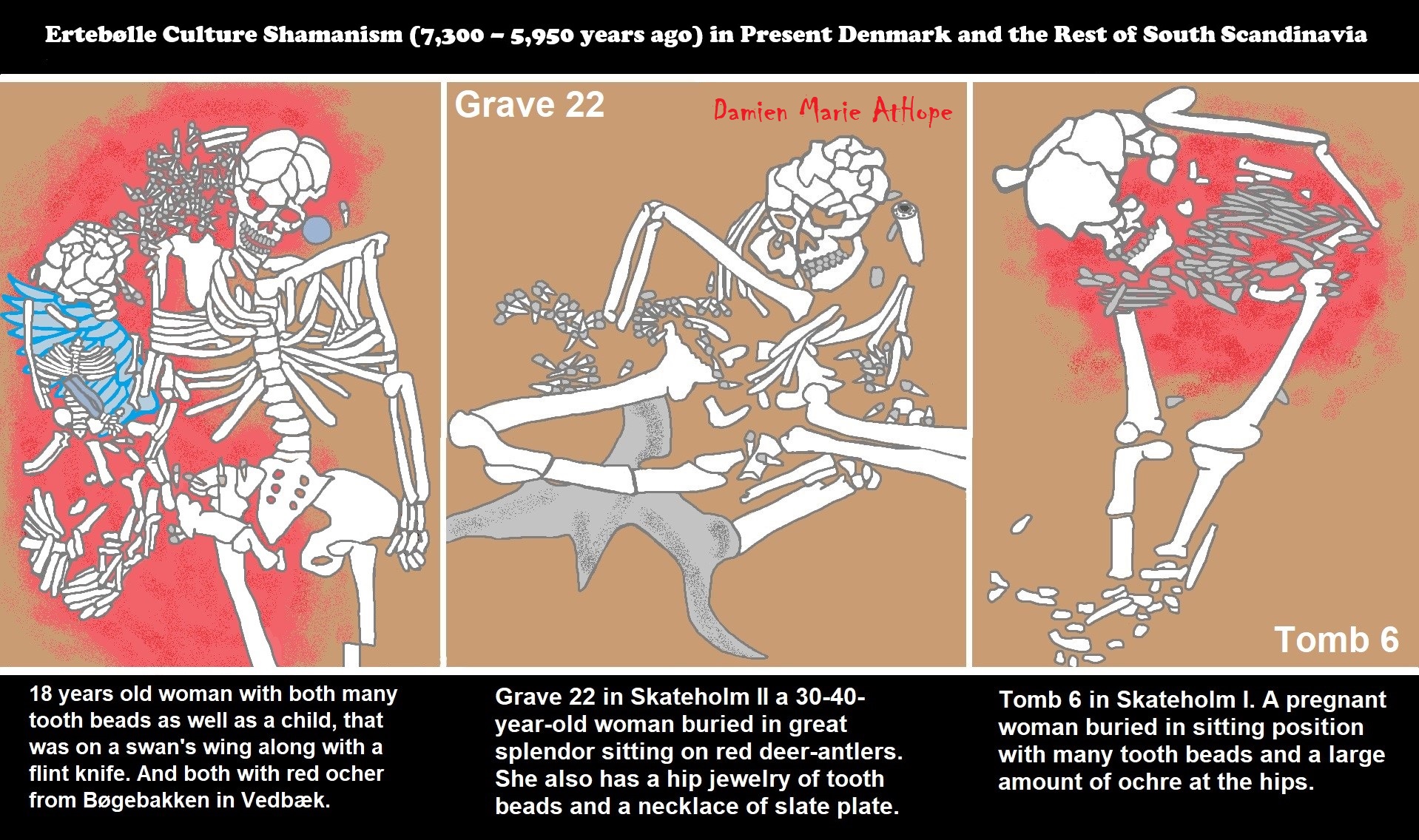

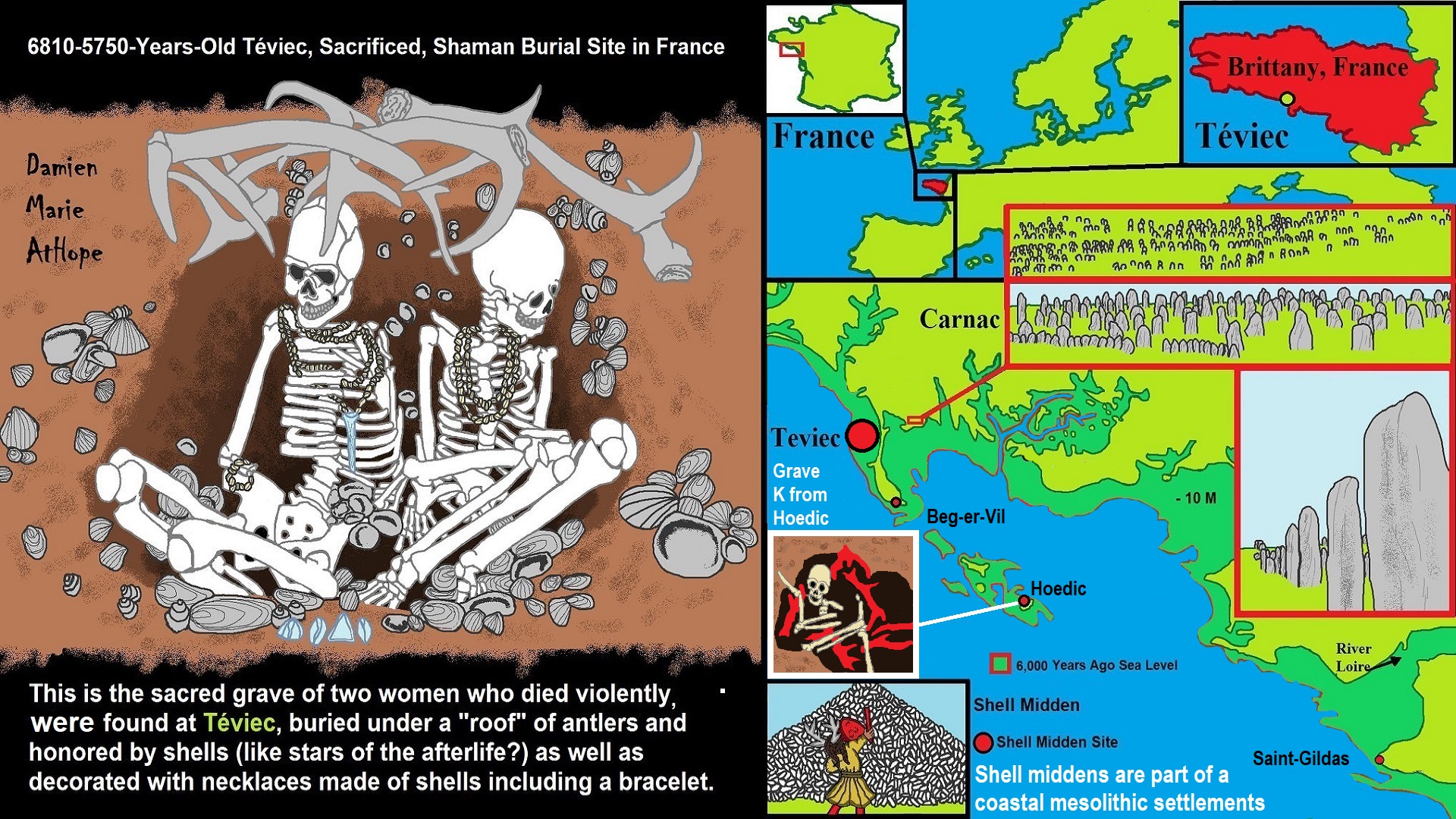

“The Ertebølle culture (c. 5,300 – 3,950 BCE or around 7,300 to 5,950 years ago) Southern Scandinavia. The Ertebølle culture replaced the earlier Kongemose culture of Denmark. The Ertebølle pot was made by coil technique, being fired on the open bed of hot coals. It was not like the neighboring Neolithic Linearbandkeramik/Linear Pottery culture (5500–4500 BCE or around 7,500 to 6,500 years ago), and appears related instead to a pottery type that first appears in Europe in the Samara region of Russia c. 7,000 cal BCE or around 9,000 years ago, and spread west. Skateholm contained also a dog cemetery. Dog graves were prepared and gifted the same as human, with ochre, antler, and grave goods. In either history or prehistory, the dog is an invaluable animal and is often treated as a person.” ref