ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

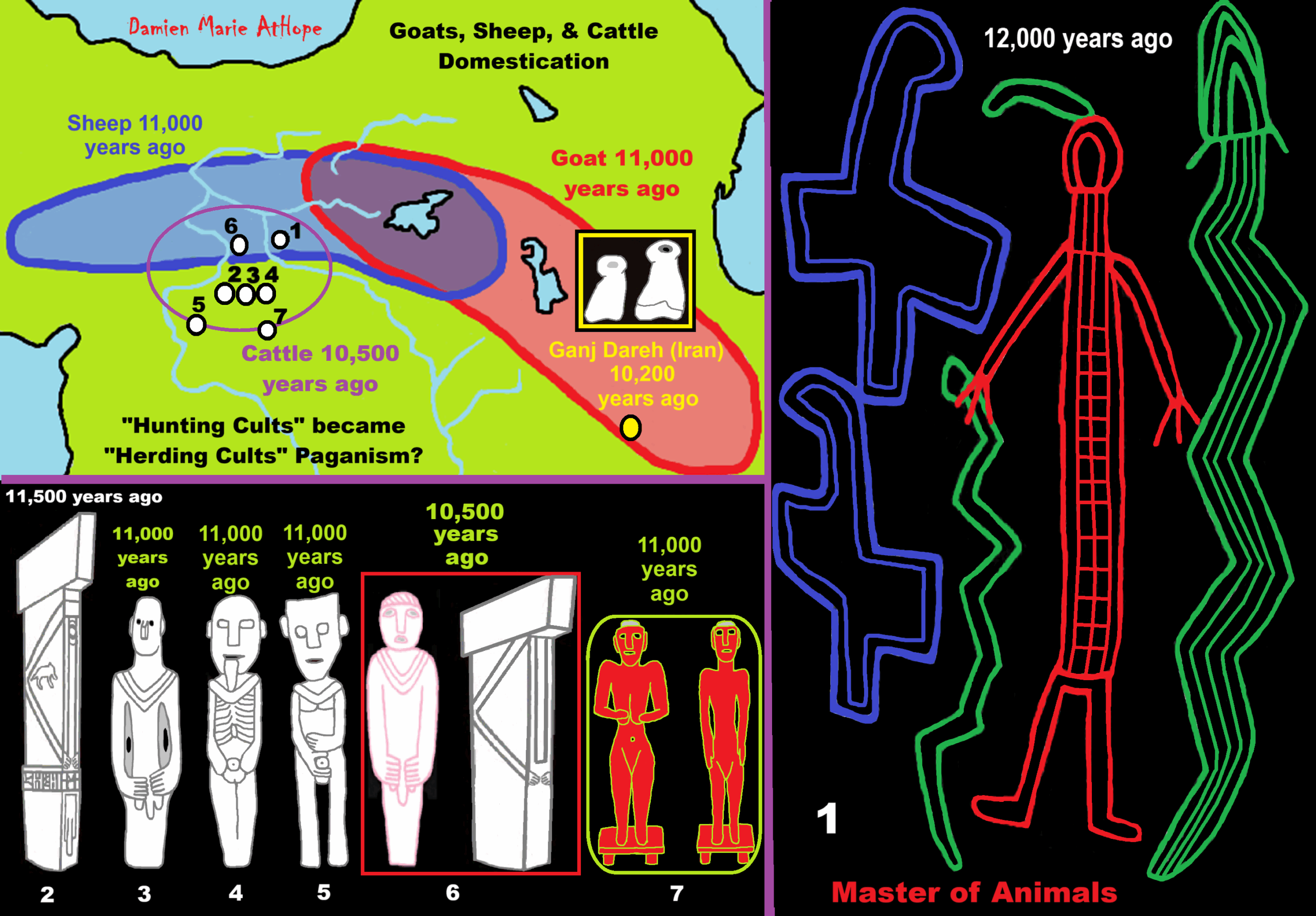

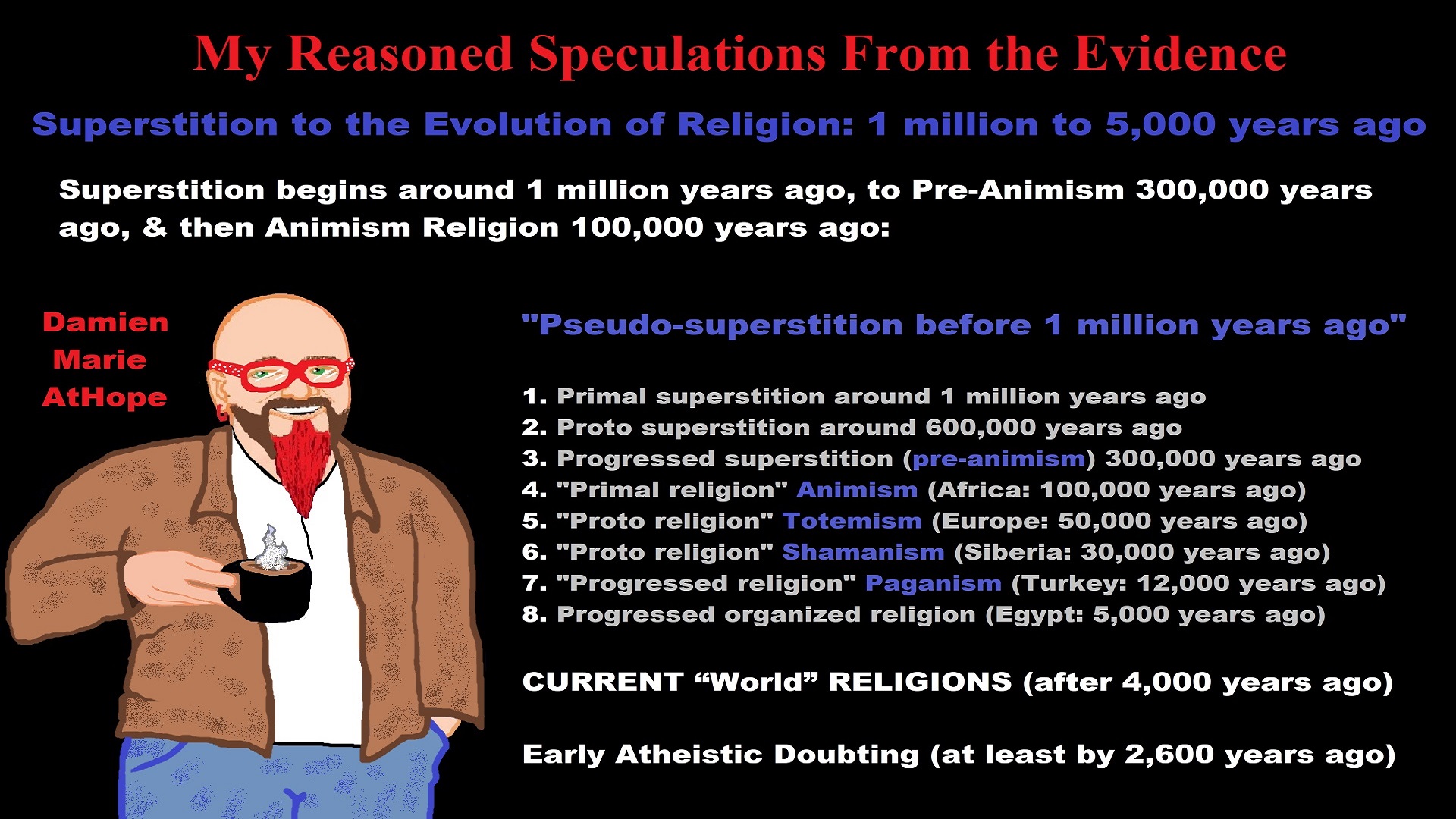

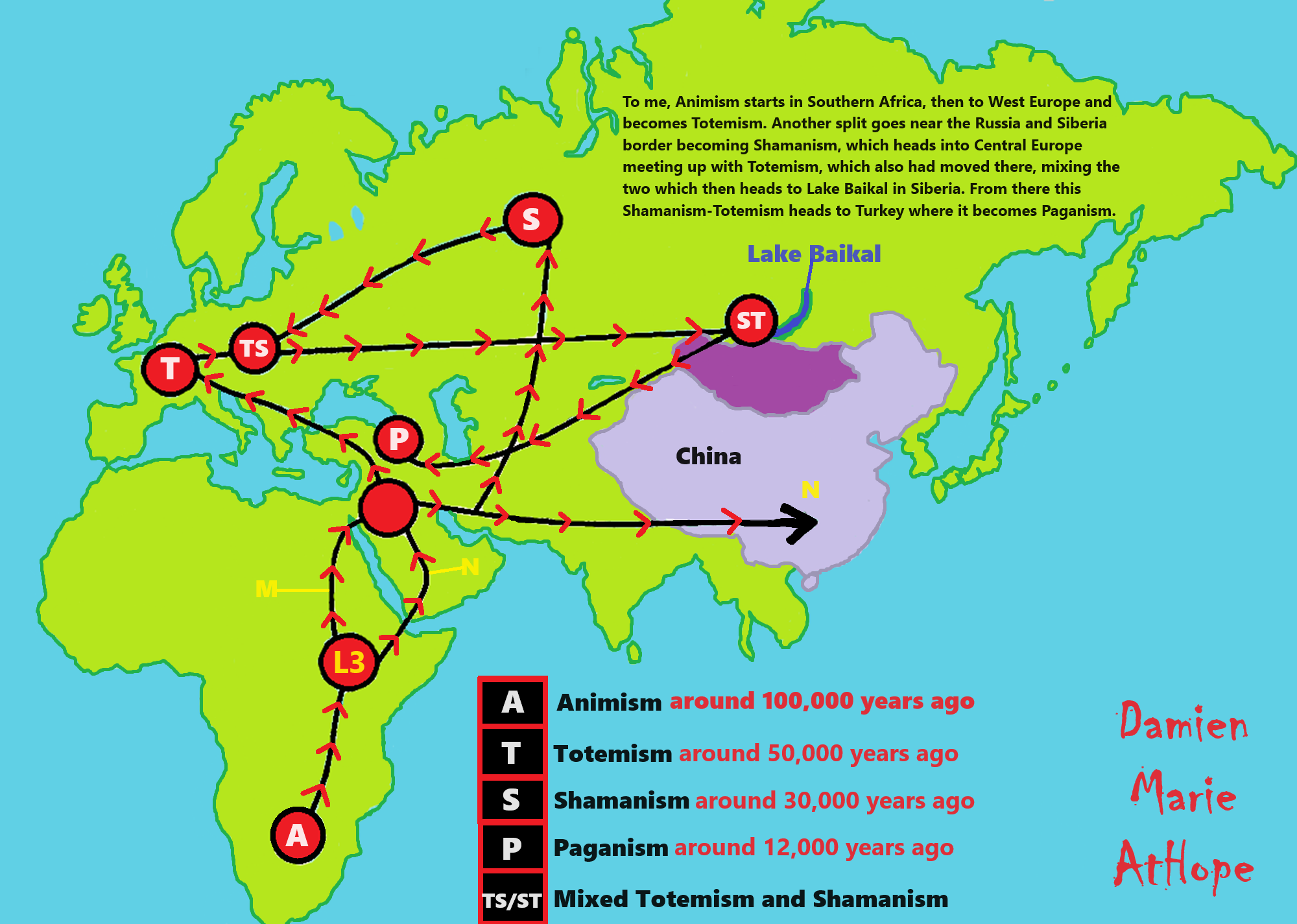

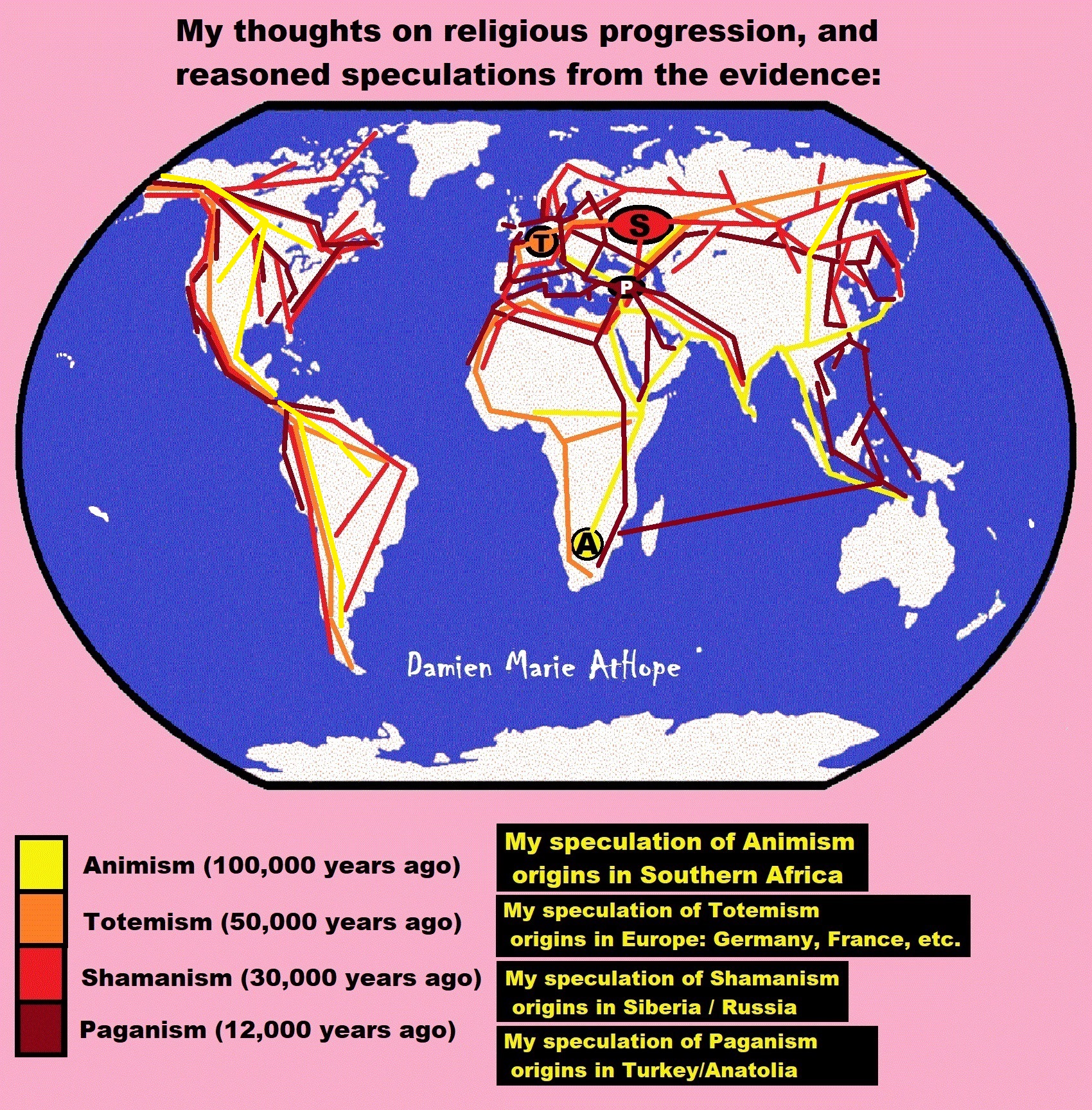

“Hunting Cult” (Cosmic Hunt) becomes “Herding Cult” Paganism

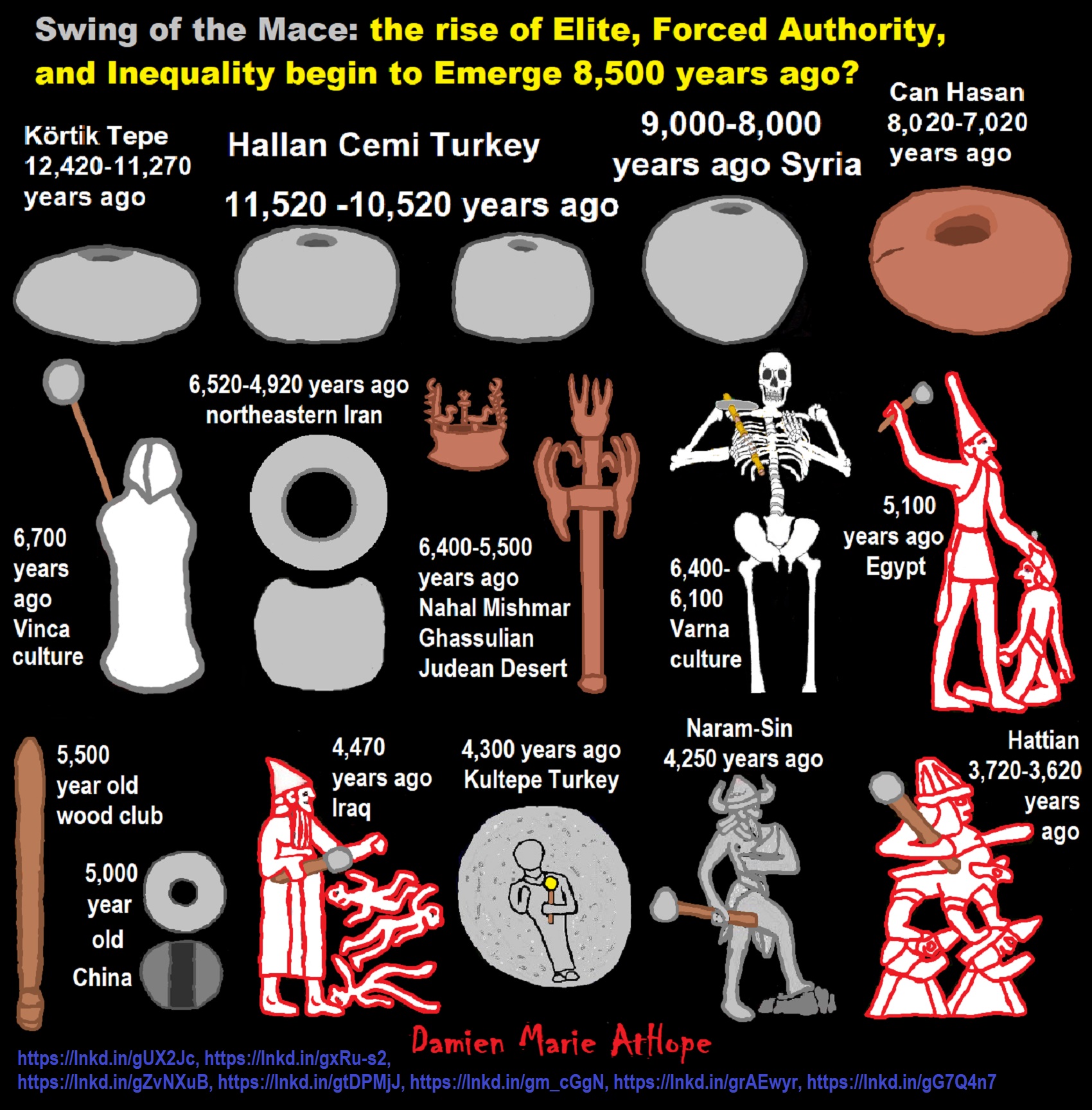

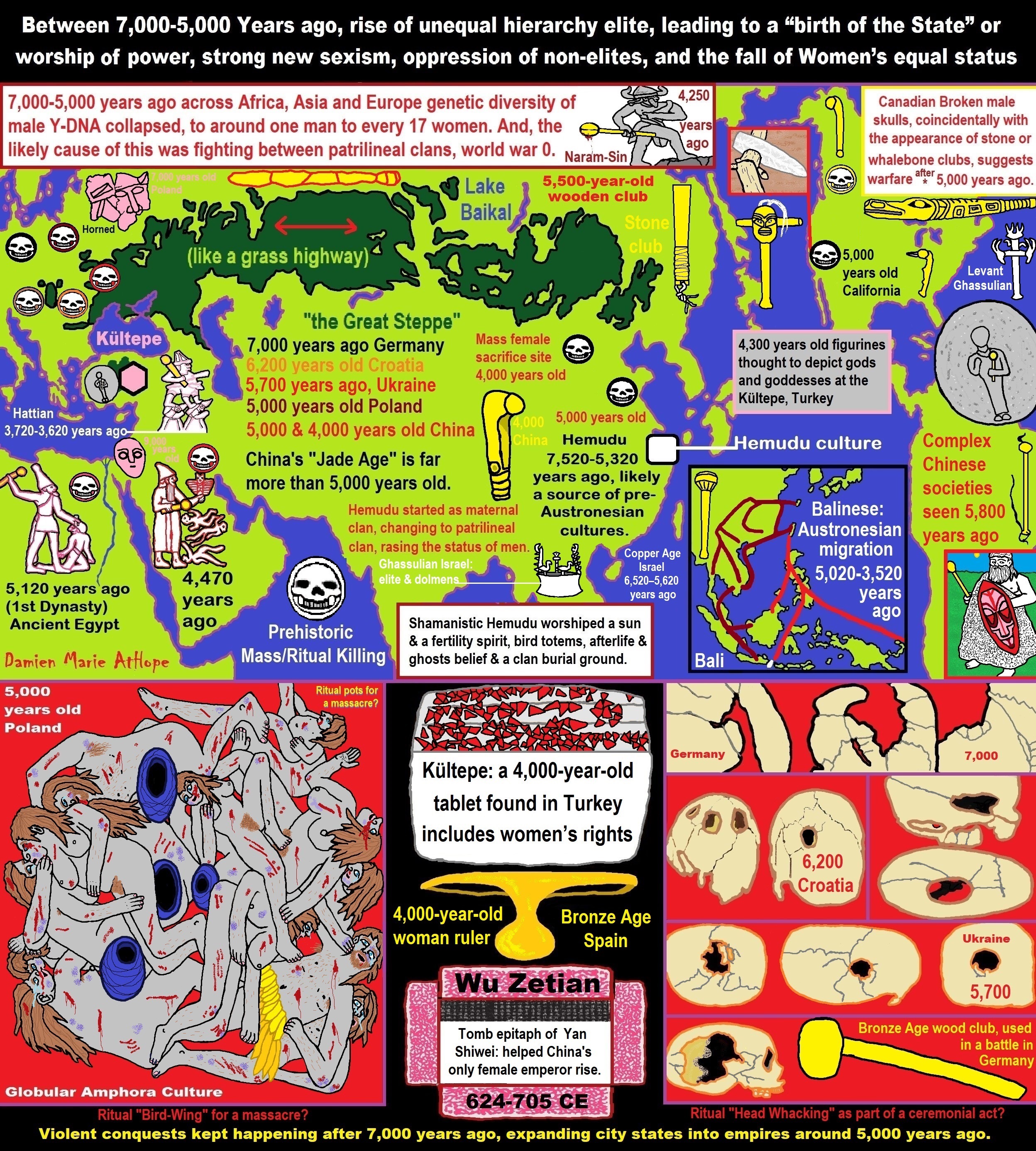

“Herding societies are nearly always that of a true hierarchical chiefdom rather than of an egalitarian society. Horticulture mixed with the domestication of animals seems to have predominated until even the least cultivable zones were filled. Sometimes, a complete symbiosis between a tribe/clan of herders and an adjacent tribe/clan of horticulturalists occurs to the point that they resemble a single society composed of two specialized castes, the herders occupying the superior position. Fully committed pastoralists manifest a considerable degree of cultural uniformity in economics, social organization, political order, and even in religion. Full pastoralism, with its powerful equestrian warriors, seems to have developed around 1500 to 1000 BCE, or around 3,500 to 3,000 years ago, in Inner Asia. Herders are likely to raid settled villages and frequently raid other herders as well.” ref

“To the extent that pastoral nomadic societies achieve wealth and success in herding and in war, they tend to solidify and extend their chiefdom structure. They also add to their religious organization a hierarchical principle, together with the content known as ancestor worship. Much of the mythology by which a primitive people explains itself and its customs comes in this way to have an ingredient familiar to readers of the Old Testament. Sometimes the significance of herding leads not only to the glorification of herds and herding, but even to a religious taboo against planting. Taboos, such as a belief that plowing and planting may defile the earth spirit. Or herders, in time of need, may engage in horticulture, but it is considered degrading to toil in farming, whereas herding is a very prideful occupation.” ref

Cult, herding, and ‘pilgrimage’

1. Körtiktepe (12,000 years ago) link & link

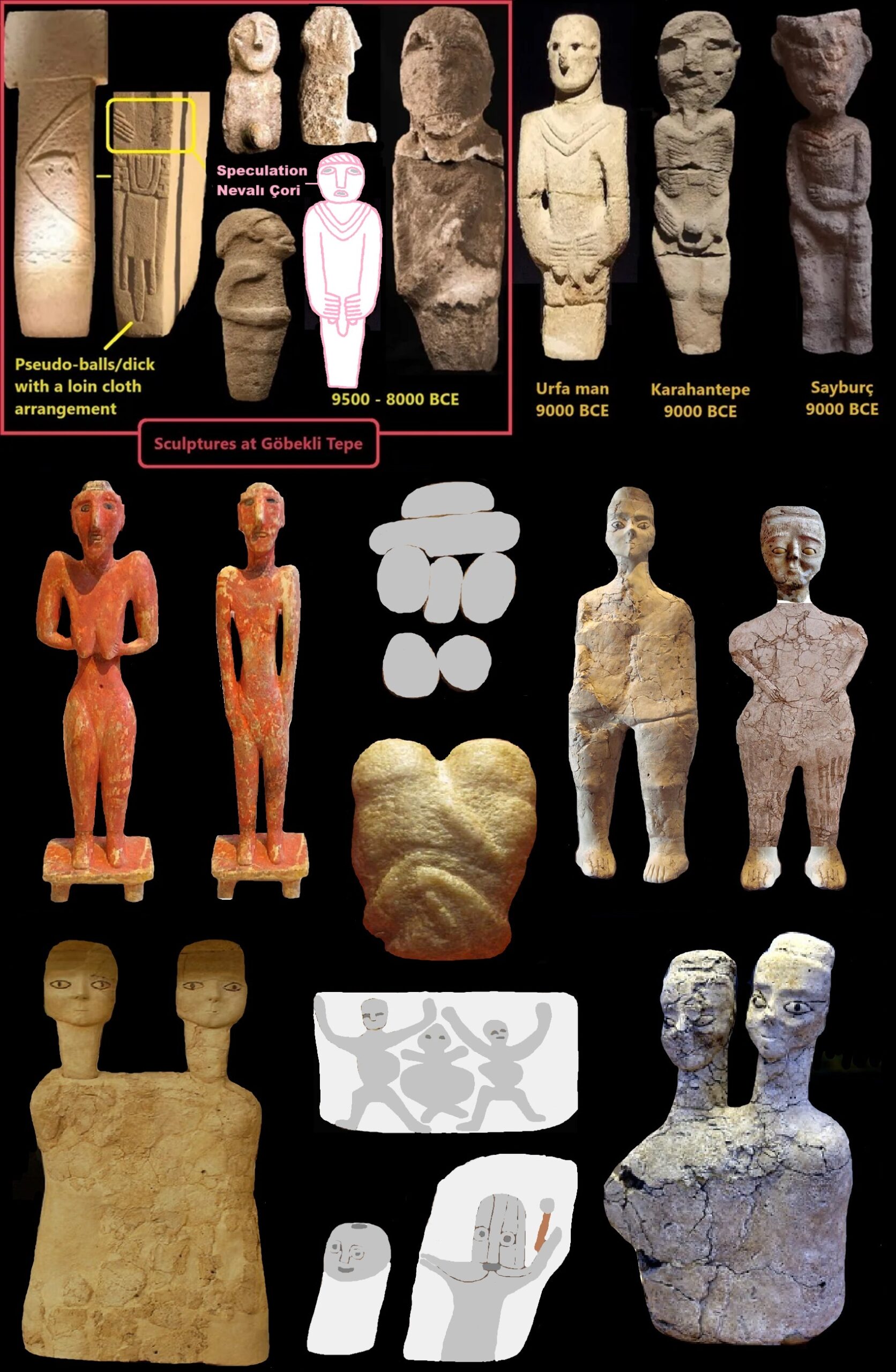

2. Göbekli Tepe (11,500 years ago) link

3. Balıklıgöl statue “Urfa man” (11,000 years ago) link

4. Karahan Tepe (11,000 years ago) link

5. Sayburç (11,000 years ago) link

6. Nevalı Çori (10,400) link & link

7. Tell Fekheriye (11,000 years ago) link

Ganj Dareh link

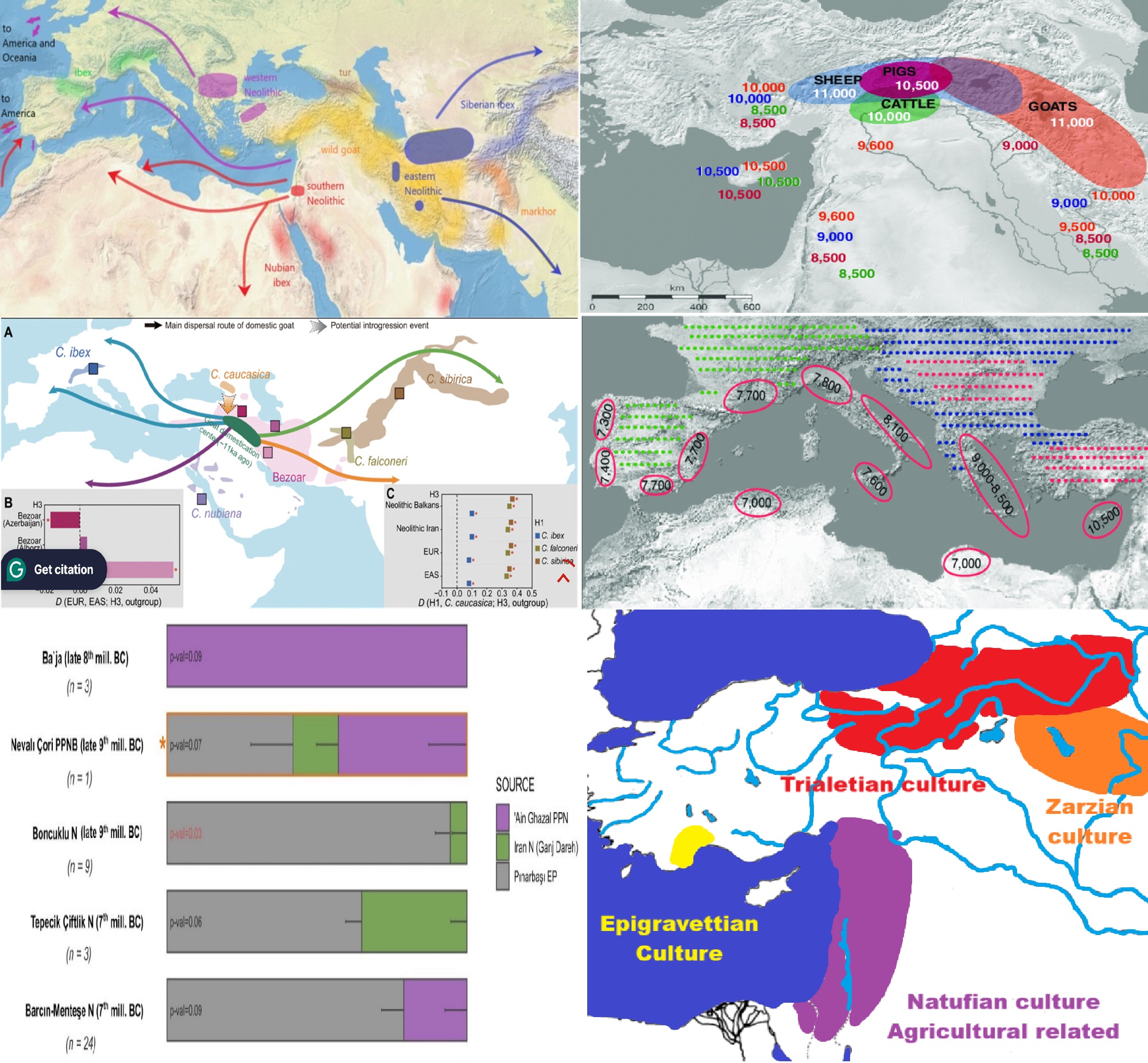

Goat, Sheep, and Cattle Domestication link & link

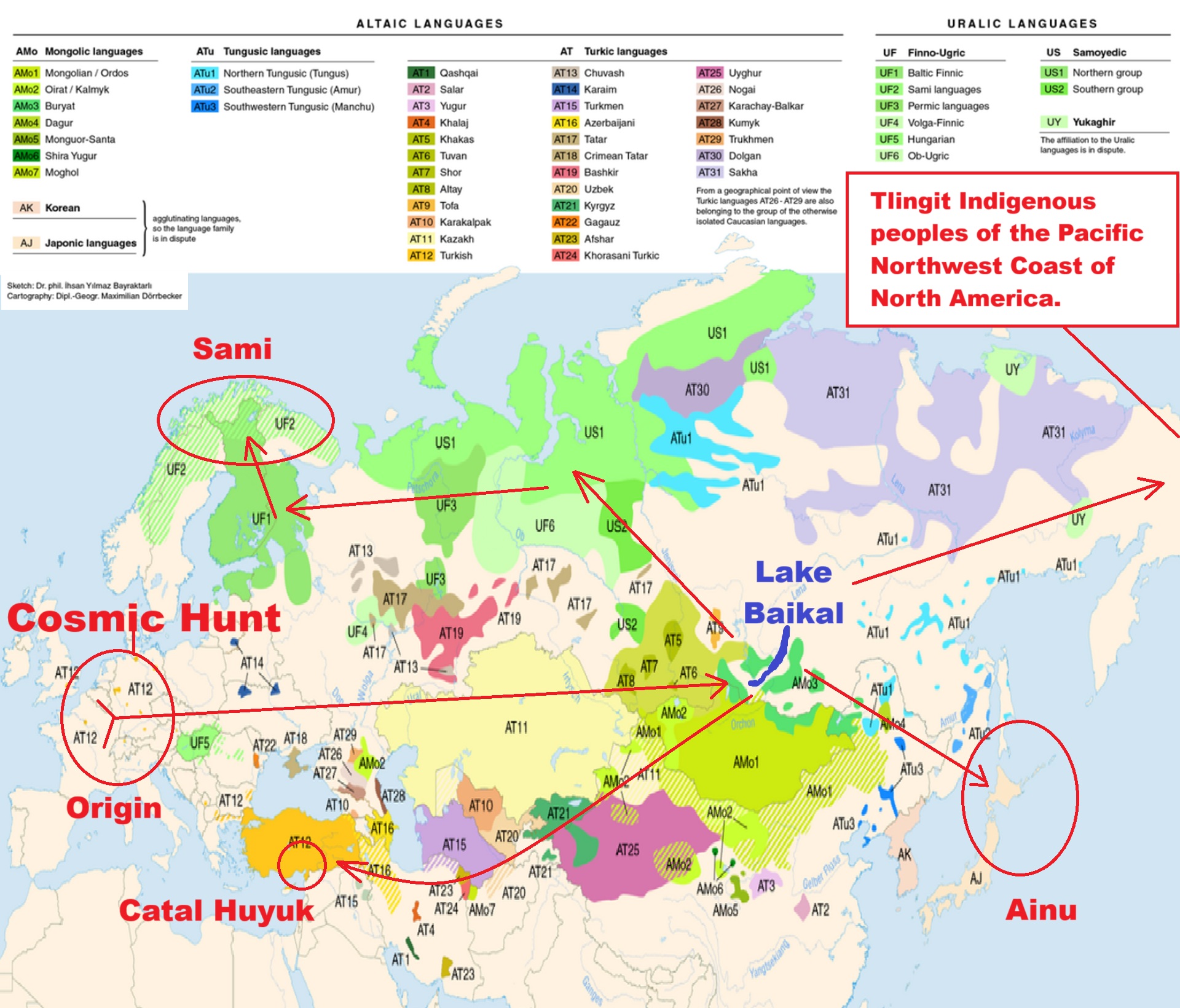

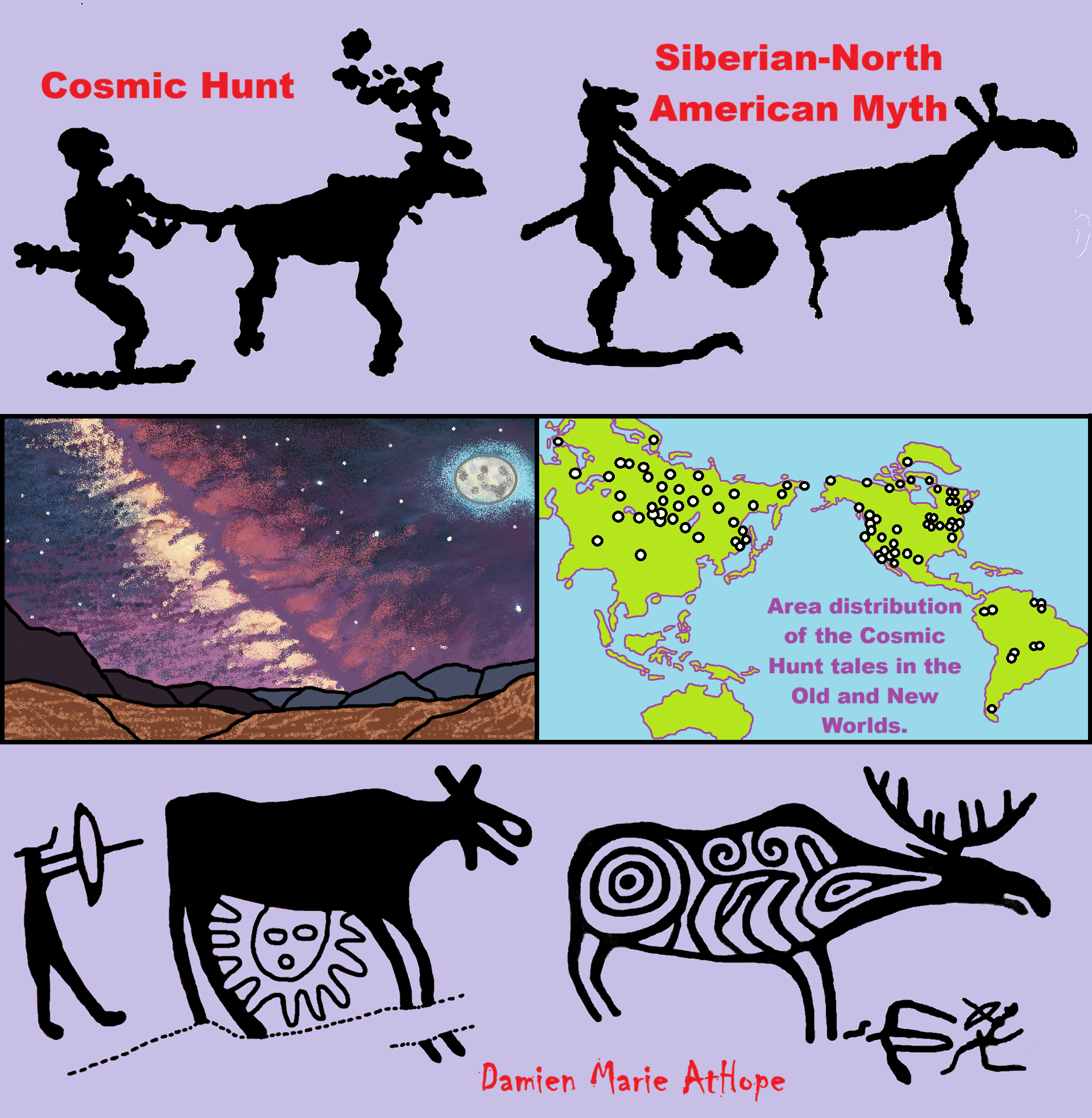

Cosmic Hunt link

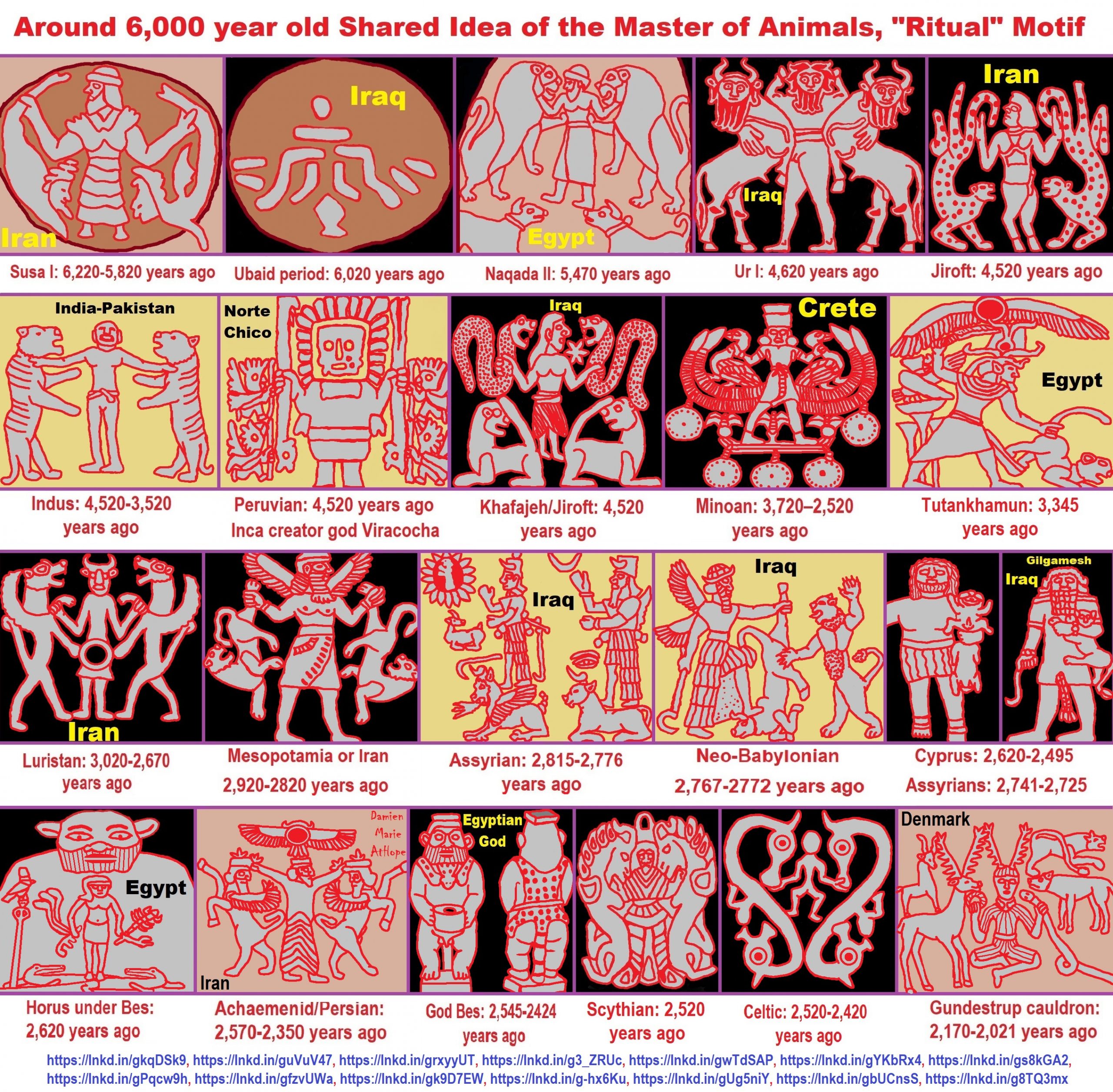

Master of Animals link

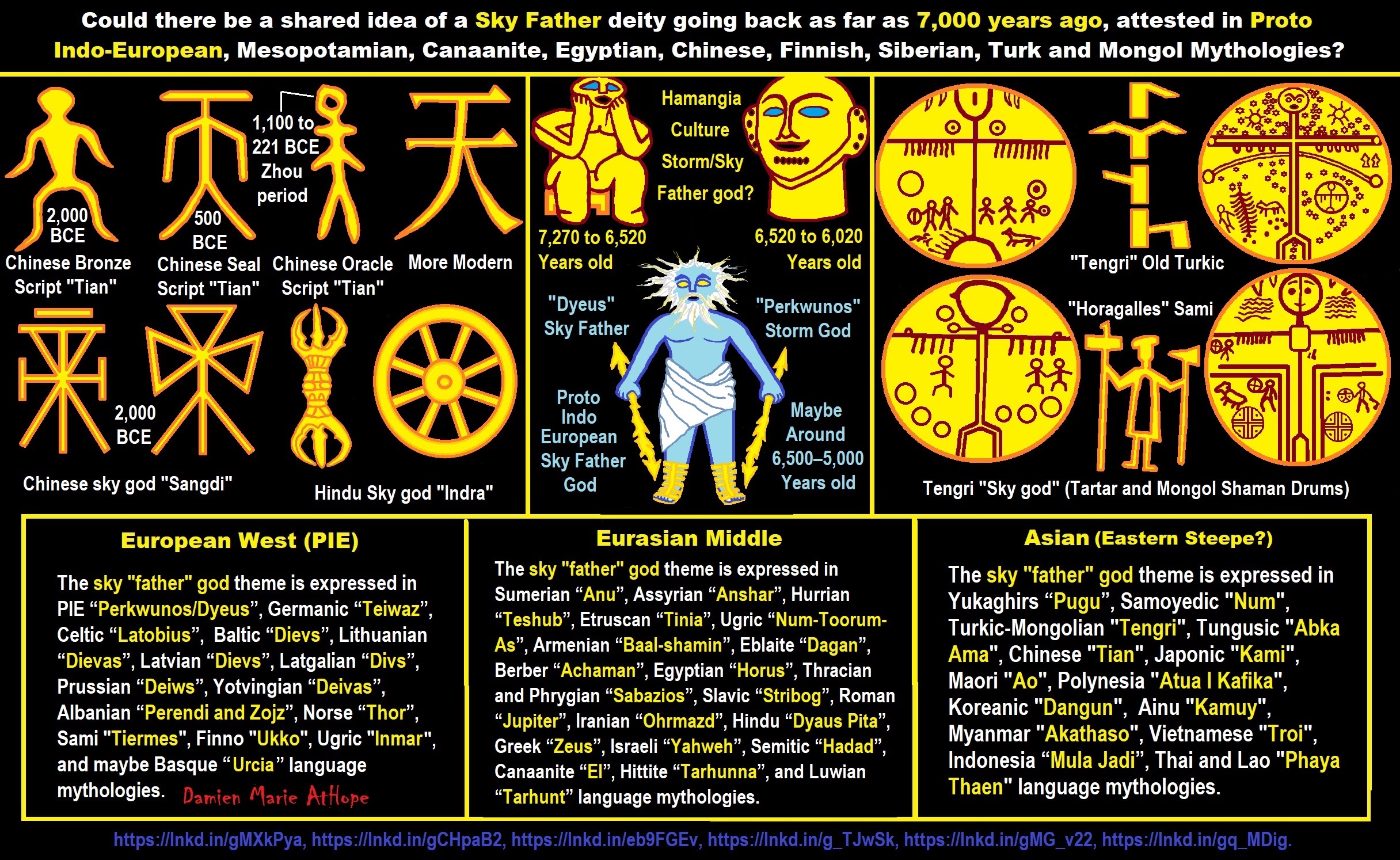

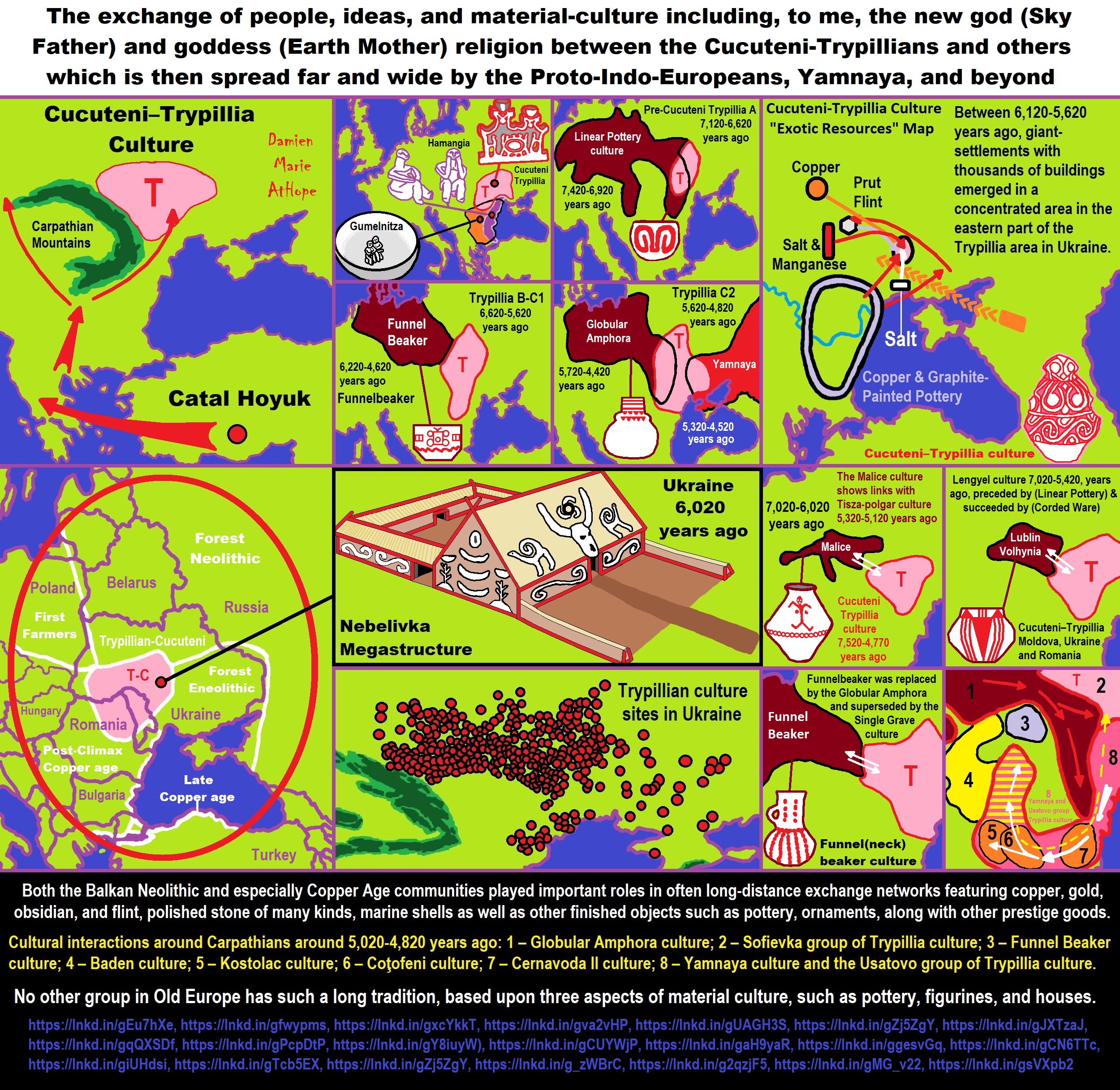

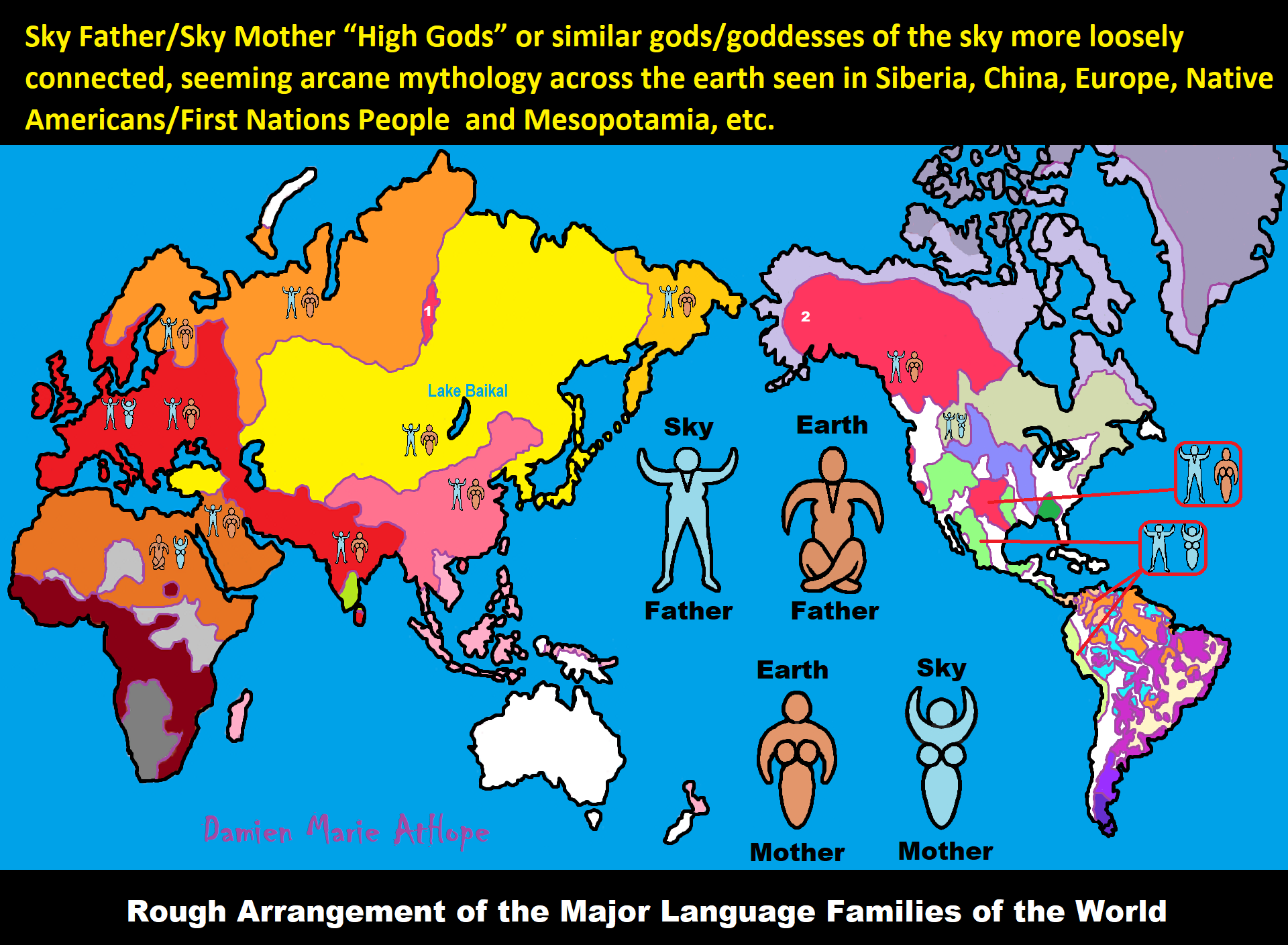

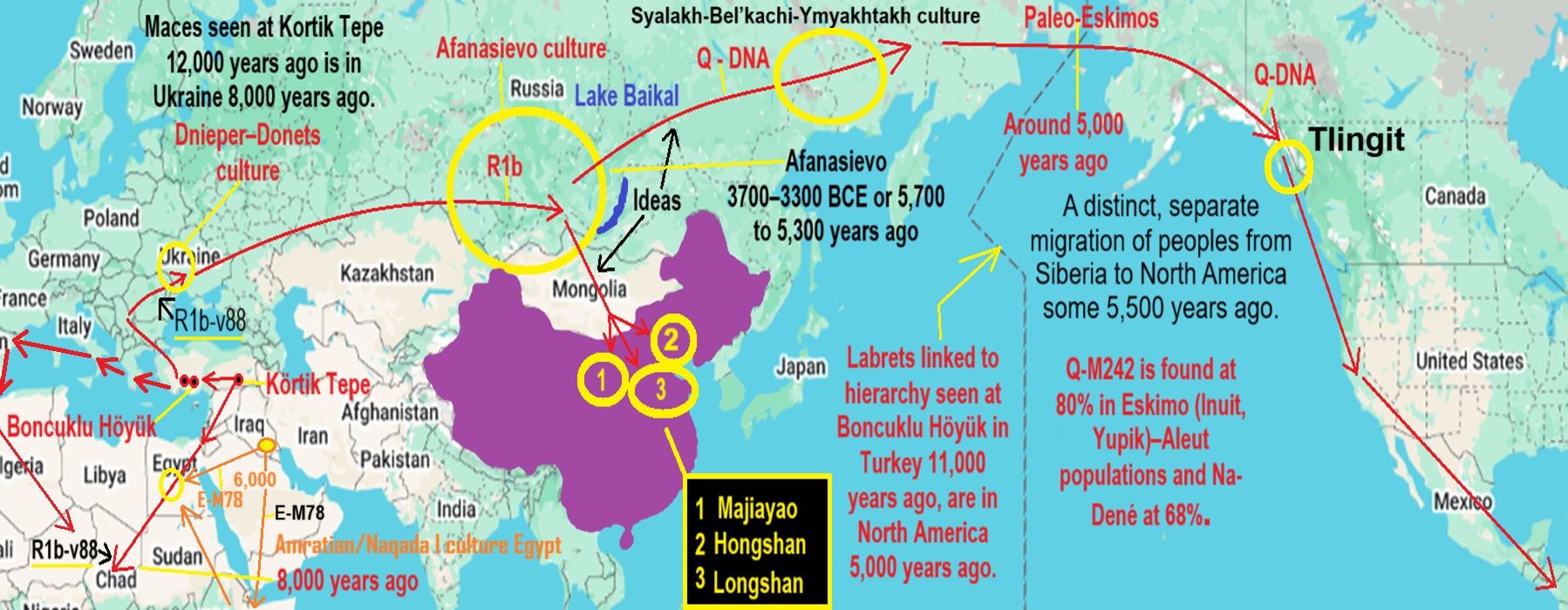

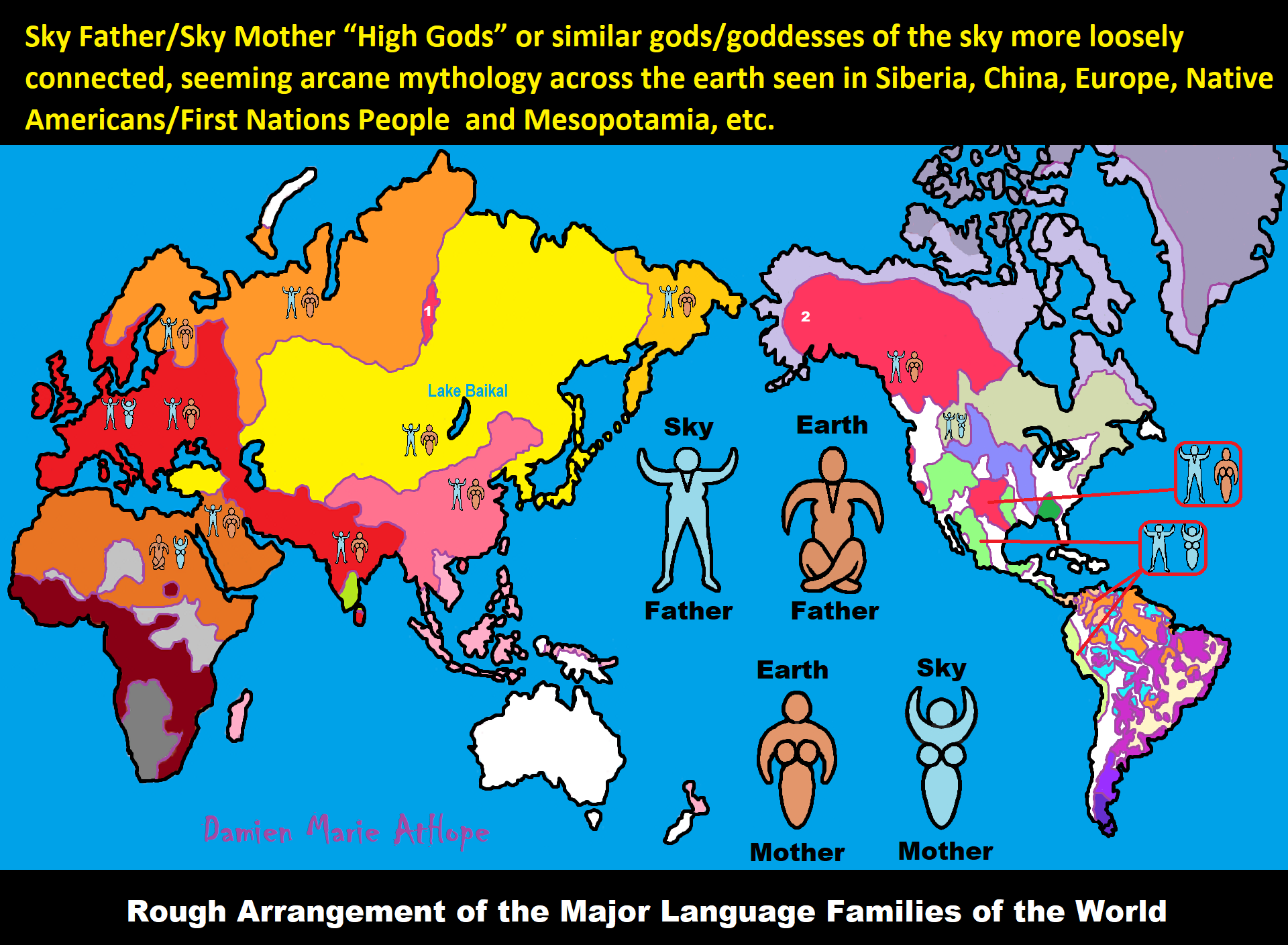

The origin of “Deities” (Sky Father/Master of Animals, a male hurding/hunting god, and Sky Mother, as seen in Earth Diver mythology, seemingly depicted together with a turtle at Nevali Cori) dates back to goat domestication 11,000 years ago, within the Trialetian culture, which is associated with R1b and also J Y-DNA haplogroups.

“The Caucasian-Anatolian area of Trialetian culture was adjacent to the Iraqi-Iranian Zarzian culture to the east and south, as well as the Levantine Natufian to the southwest. These groups were based on hunting mountain-dwelling goat-antelope “Caucasian ibex,” wild boar, and brown bear. Seen at Ali Tepe (Iran) 10,500 BCE, Cafer Hoyuk (Turkey) 8920 BCE, Hallan Çemi (Turkey) 8,600 BCE, and Nevali Çori (Turkey) 8,400 BCE.” ref

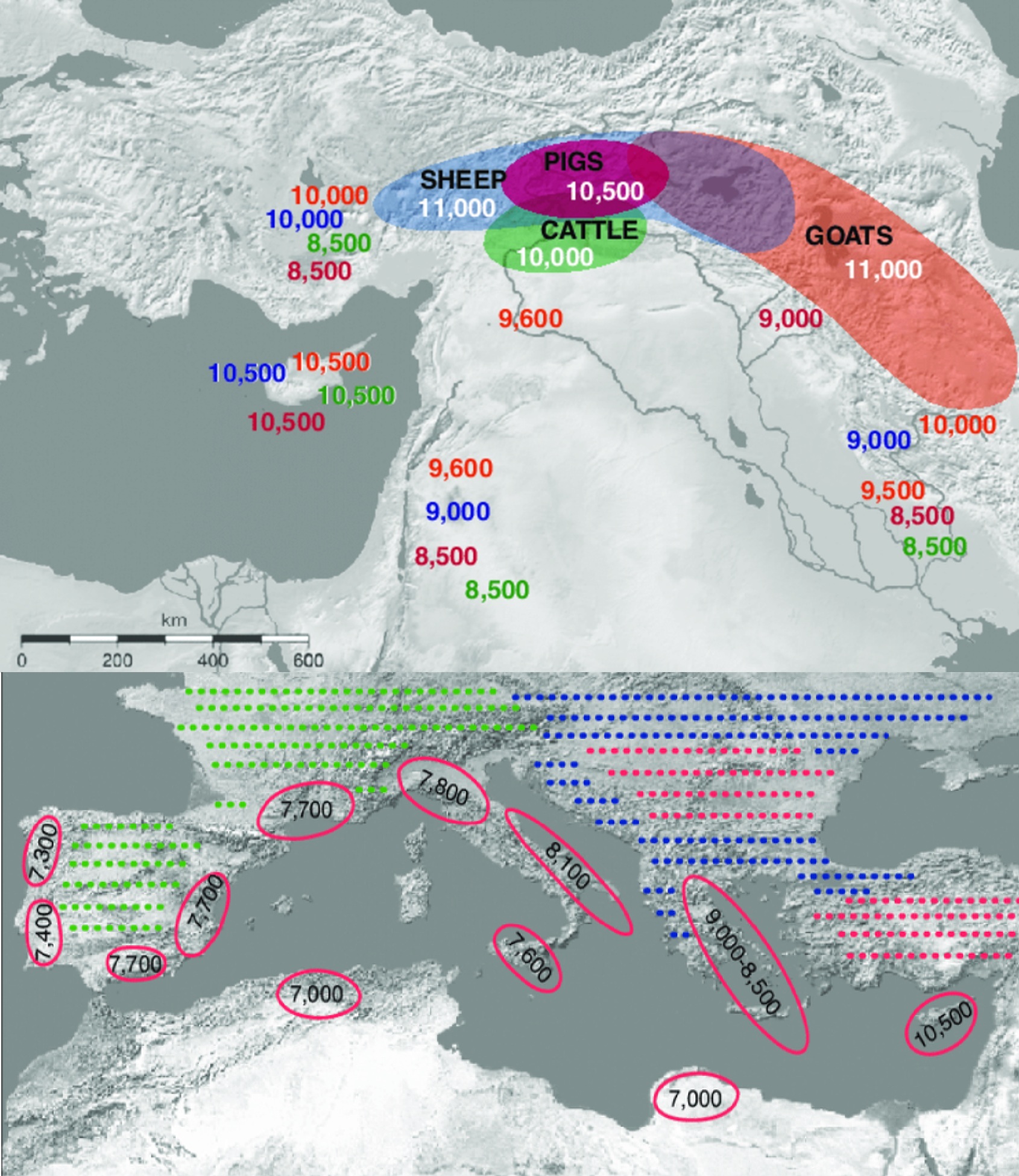

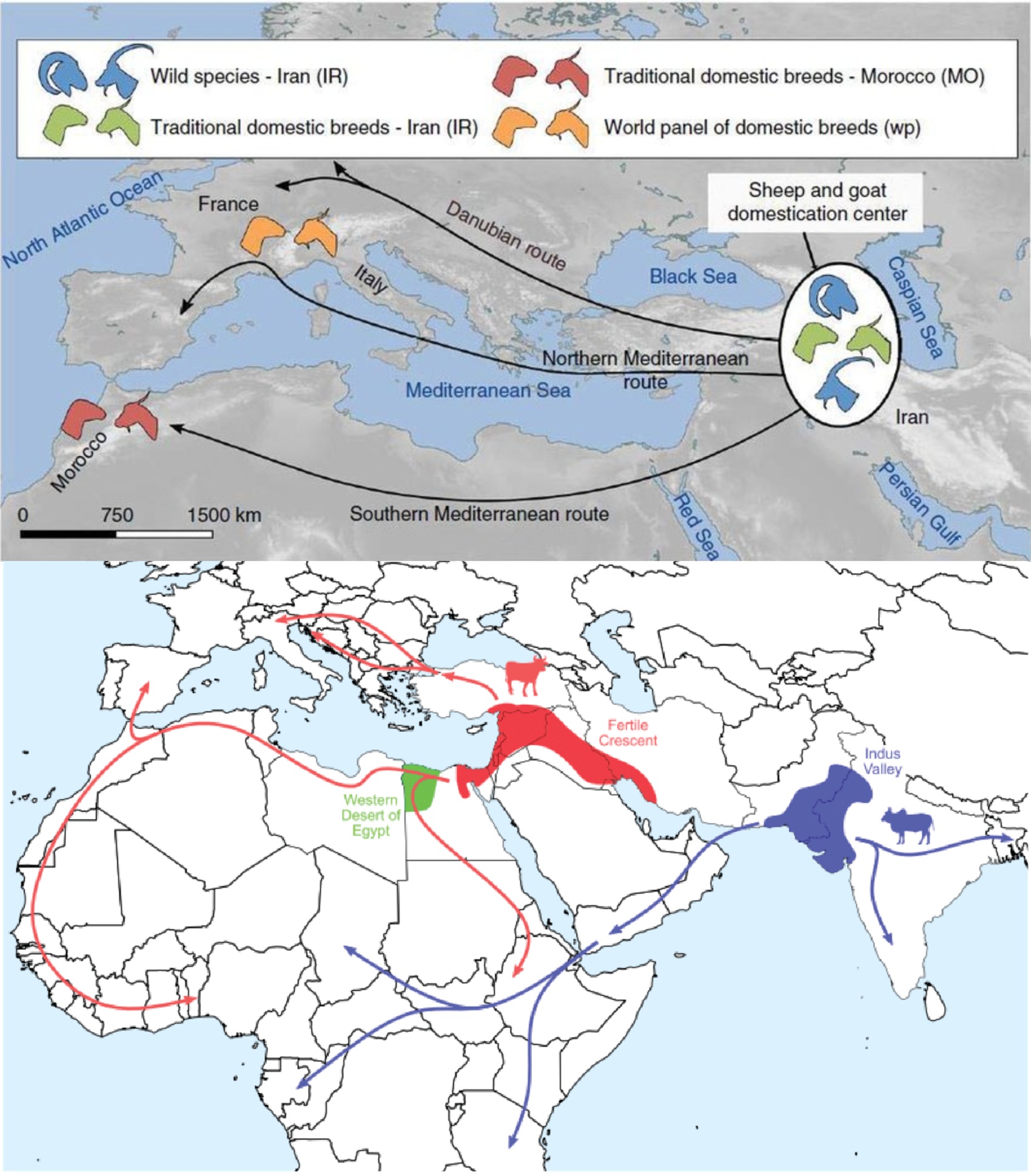

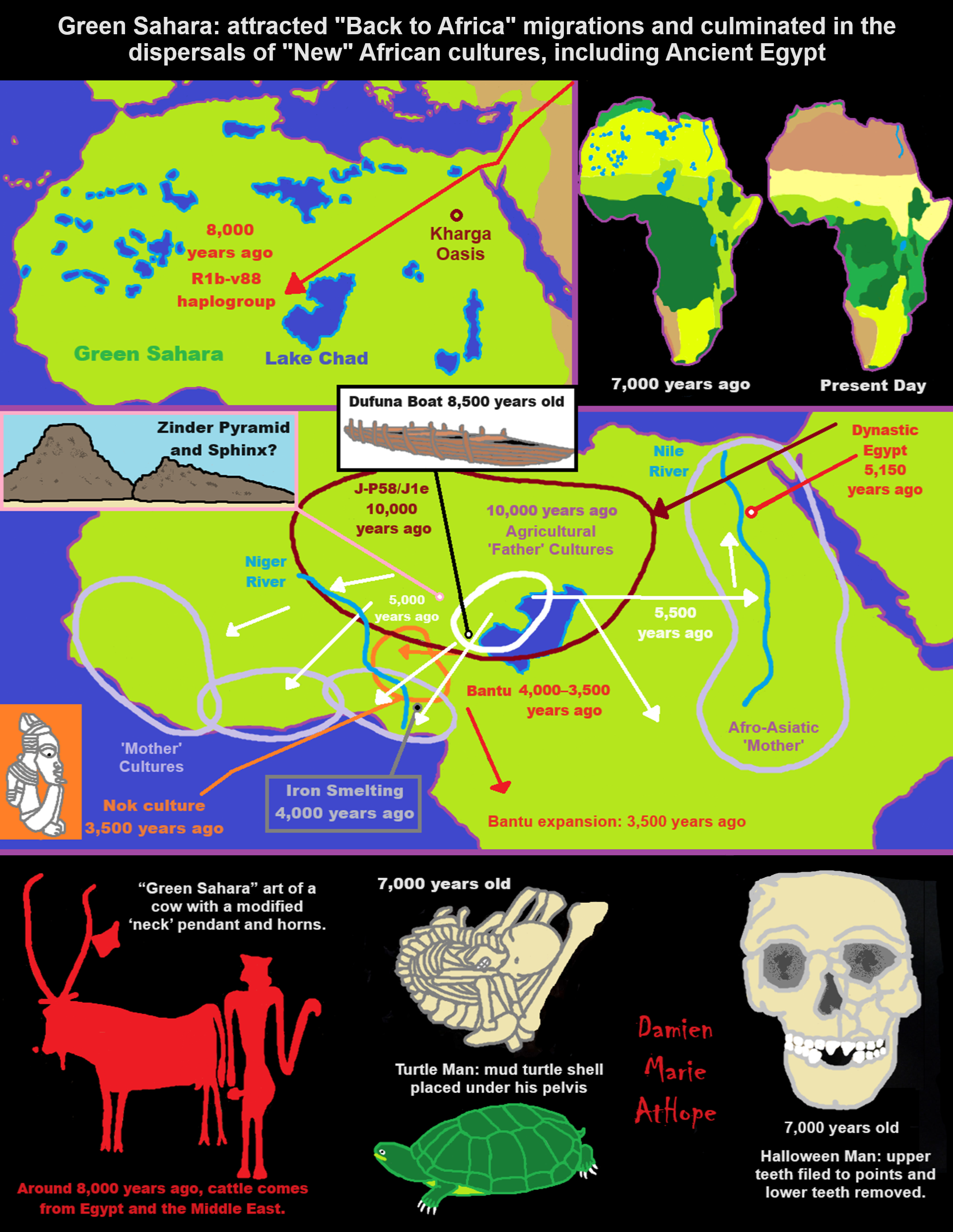

Domestication and early agriculture in the Meditrranean Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact

“The past decade has witnessed a quantum leap in our understanding of the origins, diffusion, and impact of early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin. In large measure these advances are attributable to new methods for documenting domestication in plants and animals. The initial steps toward plant and animal domestication in the Eastern Mediterranean can now be pushed back to the 12th millennium years ago. Evidence for herd management and crop cultivation appears at least 1,000 years earlier than the morphological changes traditionally used to document domestication. Different species seem to have been domesticated in different parts of the Fertile Crescent, with genetic analyses detecting multiple domestic lineages for each species. Recent evidence suggests that the expansion of domesticates and agricultural economies across the Mediterranean was accomplished by several waves of seafaring colonists who established coastal farming enclaves around the Mediterranean Basin. This process also involved the adoption of domesticates and domestic technologies by indigenous populations and the local domestication of some endemic species. Human environmental impacts are seen in the complete replacement of endemic island faunas by imported mainland fauna and in today’s anthropogenic, but threatened, Mediterranean landscapes where sustainable agricultural practices have helped maintain high biodiversity since the Neolithic.” ref

“The transition from foraging and hunting; to farming and herding is a significant threshold in human history. Domesticates and the agricultural economies based on them are associated with radical restructuring of human societies, worldwide alterations in biodiversity, and significant changes in the Earth’s landforms and its atmosphere. Given the momentous outcomes of this transition it comes as little surprise that the origin and spread of domesticates and the emergence of agriculture remain topics of enduring interest to both the scholarly community and the general public. The past decade has seen remarkable analytical advances in documenting domestication (1), particularly in tracking the domestication of four major Near Eastern livestock species (sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs) and their subsequent dispersal throughout the Mediterranean Basin. New morphometric methods are tracking changes in human prey strategies that mark the transition from hunting to herding.” ref

“Genetic analyses bring fresh insights into initial livestock domestication and their dispersal. Small-sample atomic mass spectrometry radiocarbon dating provides refined chronological frameworks for these developments. These recent analytical advances, in turn, have produced an explosion of new information that is calling into question prevailing hypotheses about the origin and early spread of animal domesticates and the Neolithic lifeways of which they were a part. Here, the researcher brings together these different sources of information to consider the origins, diffusion, and impacts of domesticates and agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin, outlining our current understanding of these developments and highlighting promising areas for future study.” ref

“Archaeological assemblages from Iraq and Iran has identified the clear signature of a managed herd of goats (harvesting of young males and prolonged survivorship of females) at the site of Ganj Dareh in highland Iran. Directly dated to 9,900 years ago, the goats from this site show no evidence of size reduction or any other domestication-induced morphological change. Smaller body size and changes in the size and shape of horns [a morphological change clearly linked to domestication] appear 500–1,000 years later than this demographic shift, when managed animals were moved from the natural habitat of wild goats and introduced into hotter and more arid lowland Iran. These follow-on morphological changes likely reflect responses to new selective pressures, plus the now more limited opportunities for introgression between managed and wild animals or the restocking of herds with wild animals.” ref

“Clear-cut morphological responses to domestication (i.e., changes in horns in bovids and tooth size in pigs) are not evident in these four livestock species until ca. 9,500–9,000 years ago. As is the case with animal domestication in the Near East, the leading edge of plant domestication in the region is now recognized as an extended process. Evidence from multiple locations points to a prolonged period of human manipulation of morphologically wild, but possibly cultivated, plants, which, in certain species, resulted in the development of morphologically altered domesticated crops. This period of intensified plant management dates at least as far back as ca. 12,000 years ago, with morphological markers of crop domestication (i.e., nonshattering seed heads in cereals) not well established until ca. 10,500 years ago. Agricultural economies reliant on a mix of domesticated crops and livestock apparently do not fully crystallize in the region until ca. 9,500–9,000 years ago.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

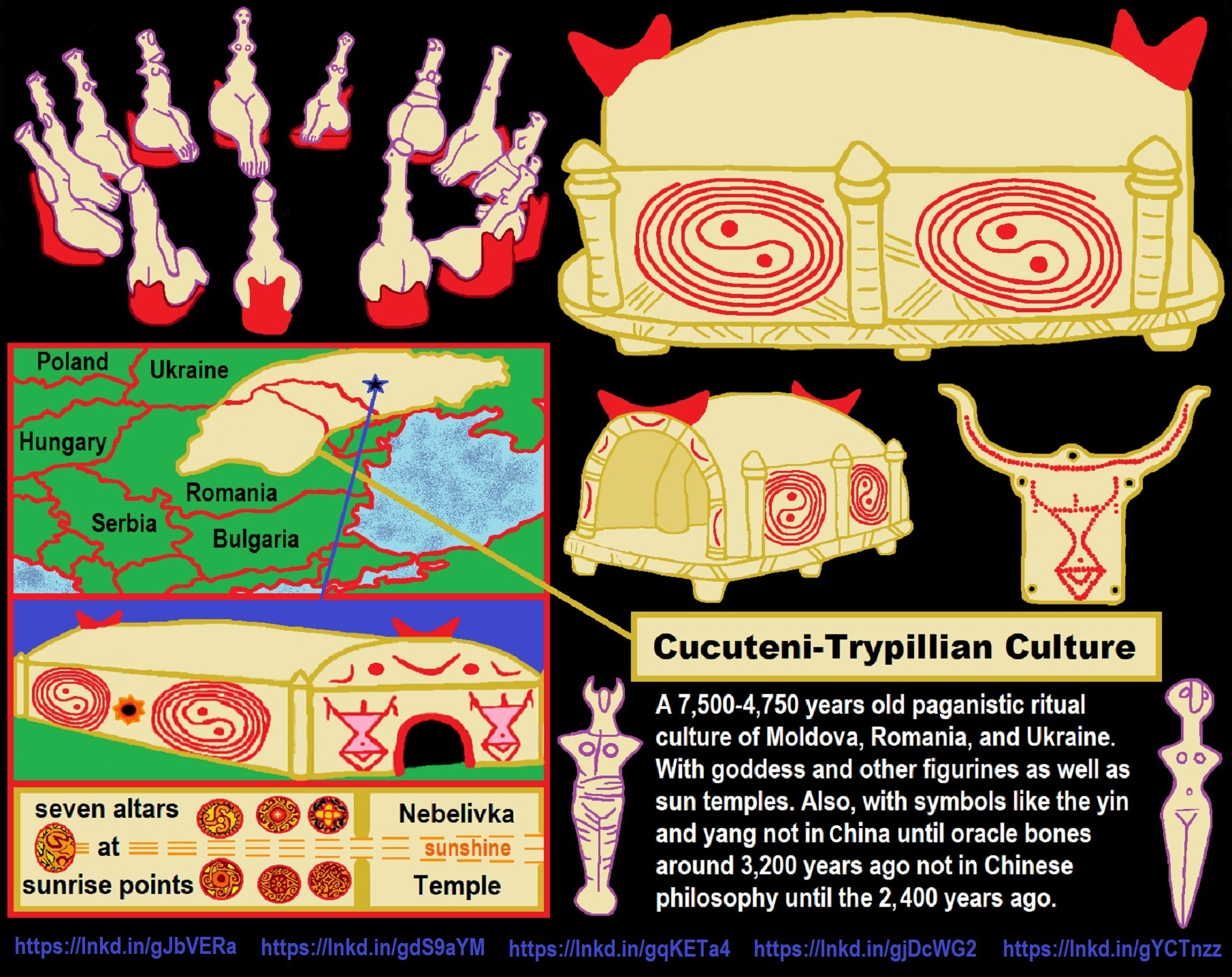

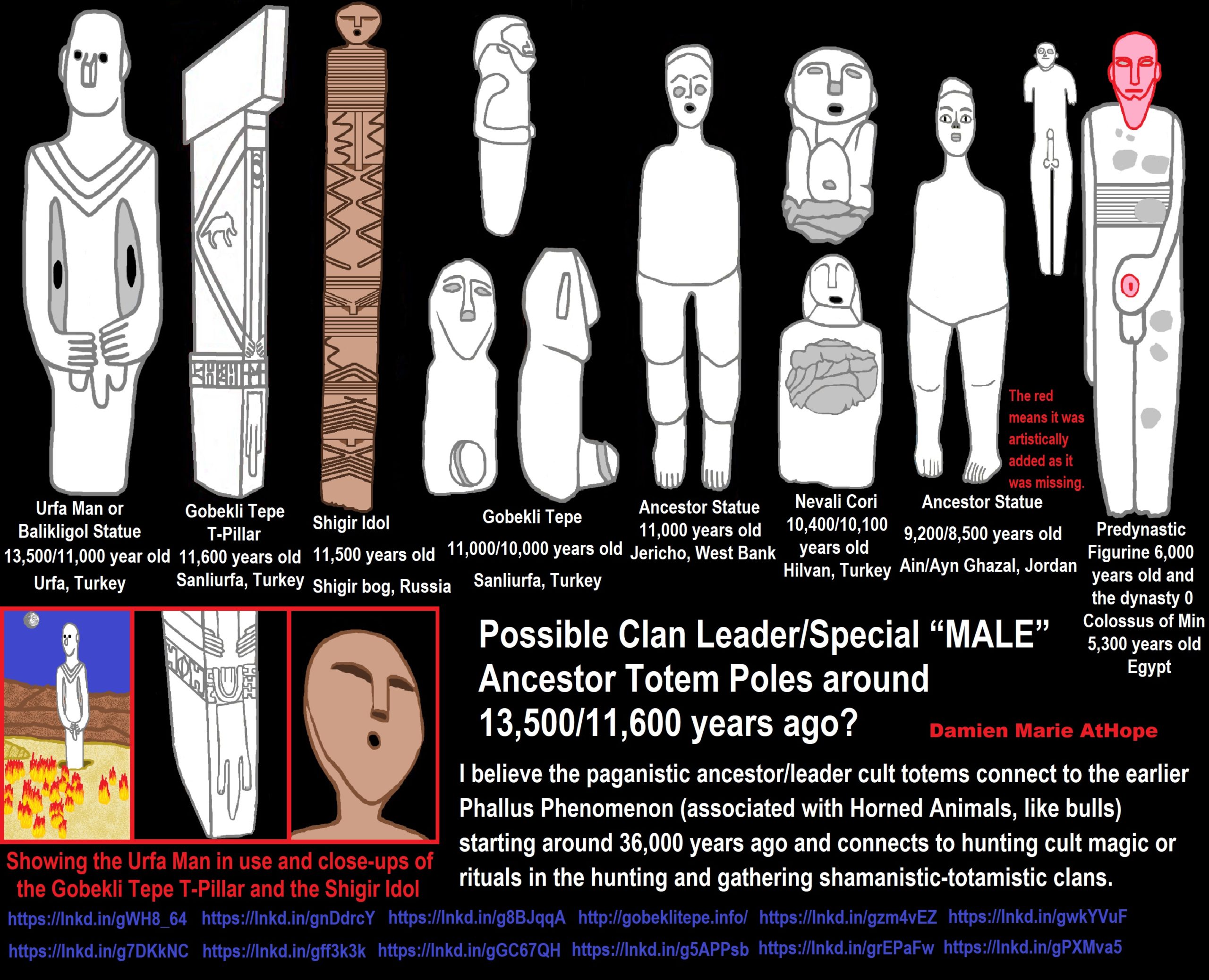

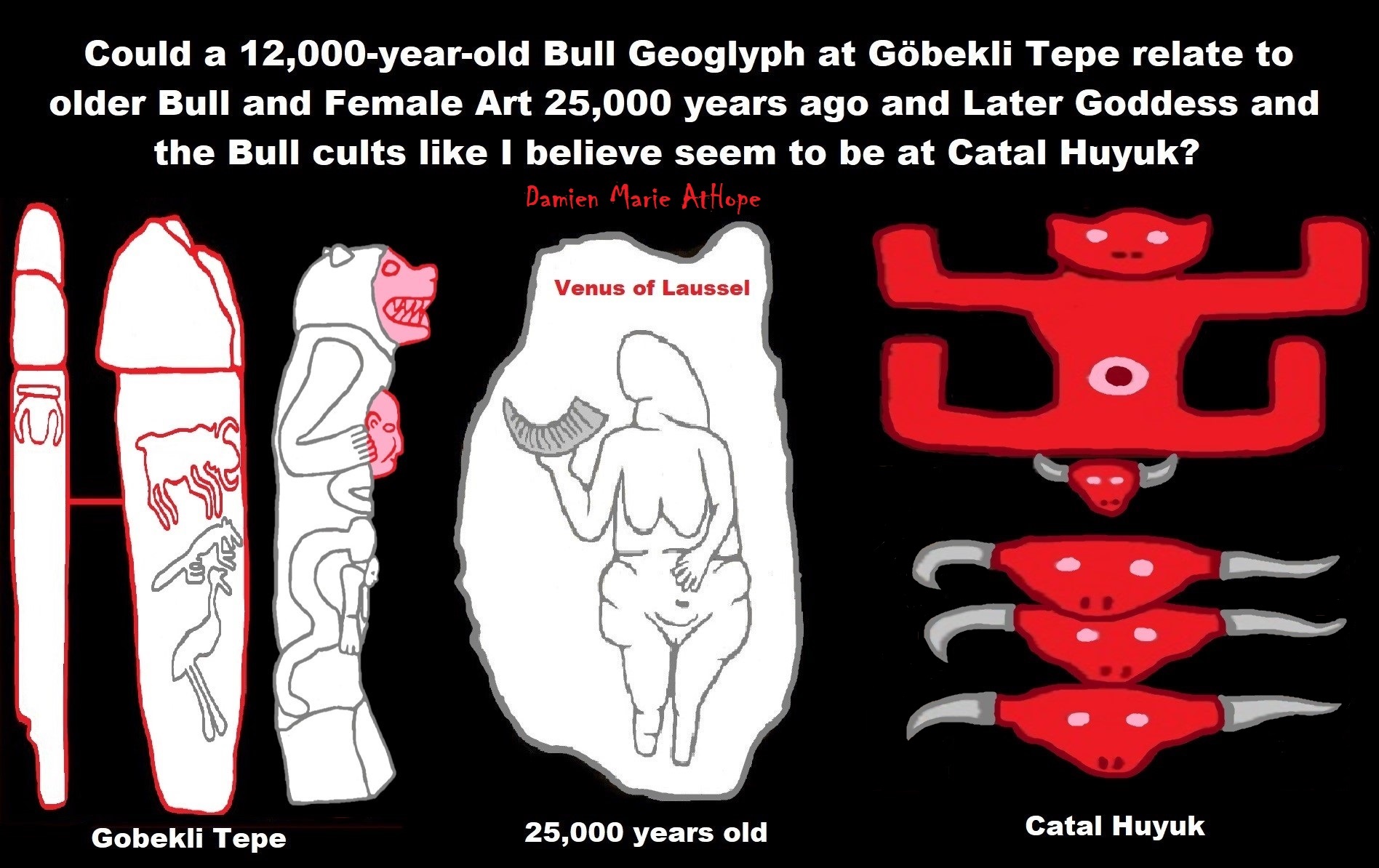

I believe the paganistic ancestor/leader cult totems connect to the earlier Phallus Phenomenon (associated with Horned Animals, like bulls) starting around 36,000 years ago and connects to hunting cult magic or rituals in the hunting and gathering shamanistic-totamistic clans.

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

The Mesopotamian “Bull of Heaven”

“In ancient Mesopotamian mythology, the Bull of Heaven is a mythical beast fought by the King of Uruk, Gilgamesh. The story of the Bull of Heaven is known from two different versions: one recorded in an earlier Sumerian poem and a later episode in the Standard Babylonian (a literary dialect of Akkadian) Epic of Gilgamesh. In the Sumerian poem, the Bull is sent to attack Gilgamesh by the goddess Inanna for reasons that are unclear. In the Sumerian poem Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven, Gilgamesh and Enkidu slay the Bull of Heaven, who has been sent to attack them by the goddess Inanna, the Sumerian equivalent of Ishtar. The plot of this poem differs substantially from the corresponding scene in the later Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh. In the Sumerian poem, Inanna does not seem to ask Gilgamesh to become her consort as she does in the later Akkadian epic. Furthermore, while she is coercing her father An to give her the Bull of Heaven, rather than threatening to raise the dead to eat the living as she does in the later epic, she merely threatens to let out a “cry” that will reach the earth.” ref

“The more complete Akkadian account comes from Tablet VI of the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which Gilgamesh refuses the sexual advances of the goddess Ishtar, the East Semitic equivalent of Inanna, leading the enraged Ishtar to demand the Bull of Heaven from her father Anu, so that she may send it to attack Gilgamesh in Uruk. Anu gives her the Bull, and she sends it to attack Gilgamesh and his companion, the hero Enkidu, who slay the Bull together. Numerous depictions of the slaying of the Bull of Heaven occur in extant works of ancient Mesopotamian art. Representations are especially common on cylinder seals of the Akkadian Empire (c. 2334 – 2154 BCE or 4,334 to 4,154 years ago). These show that the Bull was clearly envisioned as a bull of abnormally large size and ferocity. It is unclear exactly what the Bull of Heaven represents, however. Assyriologists Jeremy Black and Anthony Green observe that the Bull of Heaven is identified with the constellation Taurus and argue that the reason why Enkidu hurls the bull’s thigh at Ishtar in the Epic of Gilgamesh after defeating it may be an effort to explain why the constellation seems to be missing its hind quarters.” ref

The Mountain Goat; Symbol of Rain In Iranian Pottery

“The designs drawn by the Iranians, especially drawings of Iran’s national animal, the mountain goat, have been infused with the spirit of simplicity and precision. These designs are unique in all of Asia. The prehistoric man lived in constant fear and anxiety. He feared the satanic force, and needed a stimulant to help him defend himself from this wicked force. That is the reason why he resorted to talismans, charms, and totems to the point of worshipping them. Studying prehistoric man’s creations, helps us discover his interest in exhibiting what they considered as the manifestations of the gods that they worshipped. For example, drawings of the sun, and the animals related to the sun, such as the eagle, lion, cow, deer, and the mountain goat, can be seen on pottery dating back to the 4th millennium BCE People wore necklaces with pendants of mountain goats, especially among Cassy tribes in Lorestan. These people needed a defender because they believed that, since time immemorial, hurricanes, floods, wild animals, etc. had threatened man, his home, livestock, and crops. Because they wanted to be safe, they began worshipping the gods and goddesses, or objects and animals which they presumed the gods and goddesses liked. Sometimes only one of the animal’s limbs or organs was drawn on pottery. For example, in the pottery made during the period between 3,000 to 4,000 BCE, there are drawings of the horns of cows, deer, and mountain goats, or the wings and claws of birds, together with geometrical designs. Each ancient tribe considered the mountain goat to be the symbol of one of the natural, beneficial elements. For example, in Lorestan, it symbolized the sun. Sometimes it symbolized the rain because in ancient times the moon was related to the rain, and the sun was related to the heat and dryness. There was also a relationship between the mountain goat’s twisted horns and the crescent – shaped moon.” ref

“That is why it was believed that the mountain goat’s twisted horns could bring about rainfall. In ancient Susa and Elam, the mountain goat was the symbol of prosperity and the god of vegetation. In Mesopotamia, the mountain goat symbolized the “Great god’s” bestial nature (The Great god appeared in the role of the god of plants, holding a tee branch in his hand, while the mountain goat ate its leaves). Prehistoric men had an astonishing skill in making pottery. They made the best types of pottery by hand, and by using the potter’s wheel. In these artifacts, they have demonstrated all aspects of their lives, such as their religion, mores and art. By studying these creations, we come to know the relationship between different civilizations. These ancient people, had great skill in depicting horned animals. Maybe the transformation of gods into different drawings of animals, is one of the reasons why animals were considered sacred, and why they became an interesting topic for the works of ancient artists and potters. Most of the prehistoric pottery were first designed with geometrical and decorative designs. Drawings of animals became common after some time, and after that, geometric shapes became widespread once again. This transformation is seen in most of the prehistoric Persian civilizations. The mountain goat motif emerges in different historical periods. In excavations of many hills, archeologists have discovered vessels bearing the same motif. Here, we shall refer to some of these instances: The Sialk Hill Civilization, in Kashan, lasted from the fifth millennium to the first millennium BCE The hill has six ancient layers, each layer containing distinct types of pottery and other artifacts. Flowers and trees such as the sunflower, and the ‘Tree of Life’ (The Sacred Tree), drawn in between the goat’s horns, are very interesting. The sunflower symbolized the sun, and was considered to be sacred.” ref

Rain Bull

“Capturing the Rain Animal: an important mythological and symbolic aspect of the rock art of the San in the Drakensberg Mountains in southern Africa. With more than 500,000 rock art sites, Africa is the world’s greatest repository of ancient rock art. Of Africa’s many rock art traditions, the San – or Bushman – rock art of the Drakensberg Mountains in southern Africa is one of the finest. Some of its images have details only the width of a hair, and its delicately shaded colours fade seamlessly from white through pink to dark red. For decades, researchers believed that San rock paintings were simply a record of daily life or a primitive form of hunting magic. But by linking specific San beliefs to recurrent features in the art, researchers such as Patricia Vinnicombe and David Lewis-Williams managed to crack the fundamental codes underlying San rock art, revealing a complex and sophisticated form of symbolic art. One aspect of this is capturing the rain animal.” ref

Rain-making was one of the San shamans’ most important tasks. The southern San thought of the rain as an animal. A male rain-animal, or rain-bull, was associated with the frightening thunderstorm that bellowed, stirred up the dust, and sometimes killed people with its lightning. The female rain animal was associated with soft, soaking rains. For the San, rain was life. When it fell, tubers that had lain hidden beneath the parched land sprang up, and the veld was renewed. Then antelopes were attracted to the new grass and bushes. Columns of falling rain were called the rain’s legs, while wisps of cloud were known as the rain’s hair; mist was said to be rain’s breath. When the San did a rain dance, they would go into a trance to capture one of these animals. In their trance, they would kill it, and its blood and milk became the rain.” ref

“Mehet-Weret or Mehturt (Ancient Egyptian: mḥt-wrt) is an ancient Egyptian deity of the sky in ancient Egyptian religion. Her name means “Great Flood”. She was mentioned in the Pyramid Texts. In ancient Egyptian creation myths, she gives birth to the sun at the beginning of time. In spell 17 of the Book of the Dead, the god Ra is born from her buttocks. In art, she is portrayed as a cow with a sun disk between her horns. She is associated with the goddesses Neith, Hathor, and Isis, all of whom have similar characteristics, and like them, she could be called the “Eye of Ra”. In some instances, she is simply an epithet for those goddesses. Her own titles included ‘mound’ and ‘island’ (mound of creation). Geraldine Pinch suggests that Mehet-Weret was also ‘probably’ the Milky Way in the night sky, to correspond with her identification as the celestial waters travelled by the solar barque.” ref

Pastoralists’ indigenous religious practices: capturing the “rain-bull”

“Ritual Cemeteries—For Cows and Then Humans—Plot Pastoralist Expansion Across Africa. As early herders spread across northern and then eastern Africa, the communities erected monumental graves which may have served as social gathering points. Testing religious beliefs Pastoralists’ indigenous religious practices: found that appeasing spirits (82%), sacrifice (89%), divination (76%), and communal ceremonies (94%) were practiced in the study areas. These systems have highly contributed to personal reproduction (55%), farming practices (45%), conflict resolution (60%), forecasting events (48%), healing (60%), social cohesion (70%), and local governing (50%) among the pastoralists.” ref

Mesopotamian Gods and the Bull

“In Mesopotamia, gods were associated with the bull from at least the Early Dynastic Period until the Neo-Babylonian or Chaldean Period. This relationship took on many forms; the bull could serve as the god’s divine animal, the god could be likened to the bull, or he could actually take on the form of the beast. In this paper, the various gods identified with or related to the bull will be identified and studied in order to identify which specific types of gods were most commonly and especially associated with the bull. The relationships between the gods and the bull are evident in textual as well as iconographic sources, although fewer instances of this connection are found in iconography. Examples of the portrayal of the association between the various gods and the bull in texts and iconography can be compared and contrasted in order to reveal differences and similarities in these portrayals.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Sacred Cattle in Egyptian Mythology

“Bat is a cow goddess in Egyptian mythology who was depicted as a human face with cow ears and horns or as a woman. Other feminine bovine deities include Sekhat-Hor, Mehet-Weryt, Shedyt, Hathor, Hesat, and Celestial Cow “Sky goddess” Nut. Their masculine counterparts include Apis, Mnevis, Buchis, Sema-wer, Ageb-wer. Cattle are prominent in some religions and mythologies. As such, numerous people throughout the world have at one point in time honored bulls as sacred. In the Sumerian religion, Marduk is the “bull of Utu”. In Hinduism, Shiva’s steed is Nandi, the Bull. The sacred bull survives in the constellation Taurus. The bull, whether lunar as in Mesopotamia or solar as in India, is the subject of various other cultural and religious incarnations.” ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Sumerian religion, Marduk is the “Bull of Utu”

“Taurus (Latin, ‘Bull‘) is one of the constellations of the zodiac and is located in the northern celestial hemisphere. Taurus is a large and prominent constellation in the Northern Hemisphere‘s winter sky. It is one of the oldest constellations, dating back to the Early Bronze Age at least, when it marked the location of the Sun during the spring equinox. Its importance to the agricultural calendar influenced various bull figures in the mythologies of Ancient Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, Greece, and Rome. Its old astronomical symbol is (♉︎), which resembles a bull’s head. We cannot recreate a specific context for the bull skulls with horns (bucrania) preserved in an 8th millennium BCE sanctuary at Çatalhöyük in Central Anatolia. The sacred bull of the Hattians, whose elaborate standards were found at Alaca Höyük alongside those of the sacred stag, survived in Hurrian and Hittite mythology as Seri and Hurri (“Day” and “Night”), the bulls who carried the weather god Teshub on their backs or in his chariot and grazed on the ruins of cities.” ref

“The identification of the constellation of Taurus with a bull is very old, certainly dating to the Chalcolithic, and perhaps even to the Upper Paleolithic. Michael Rappenglück of the University of Munich believes that Taurus is represented in a cave painting at the Hall of the Bulls in the caves at Lascaux (dated to roughly 15,000 BCE), which he believes is accompanied by a depiction of the Pleiades. The name “seven sisters” has been used for the Pleiades in the languages of many cultures, including indigenous groups of Australia, North America and Siberia. This suggests that the name may have a common ancient origin. Taurus marked the point of vernal (spring) equinox in the Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Age, from about 4000 to 1700 BCE, after which it moved into the neighboring constellation Aries. The Pleiades were closest to the Sun at vernal equinox around the 23rd century BCE. In Babylonian astronomy, the constellation was listed in the MUL.APIN as GU4.AN.NA, “The Bull of Heaven“. Although it has been claimed that “when the Babylonians first set up their zodiac, the vernal equinox lay in Taurus,” there is a claim that the MUL.APIN tablets indicate that the vernal equinox was marked by the Babylonian constellation known as “the hired man” (the modern Aries).” ref

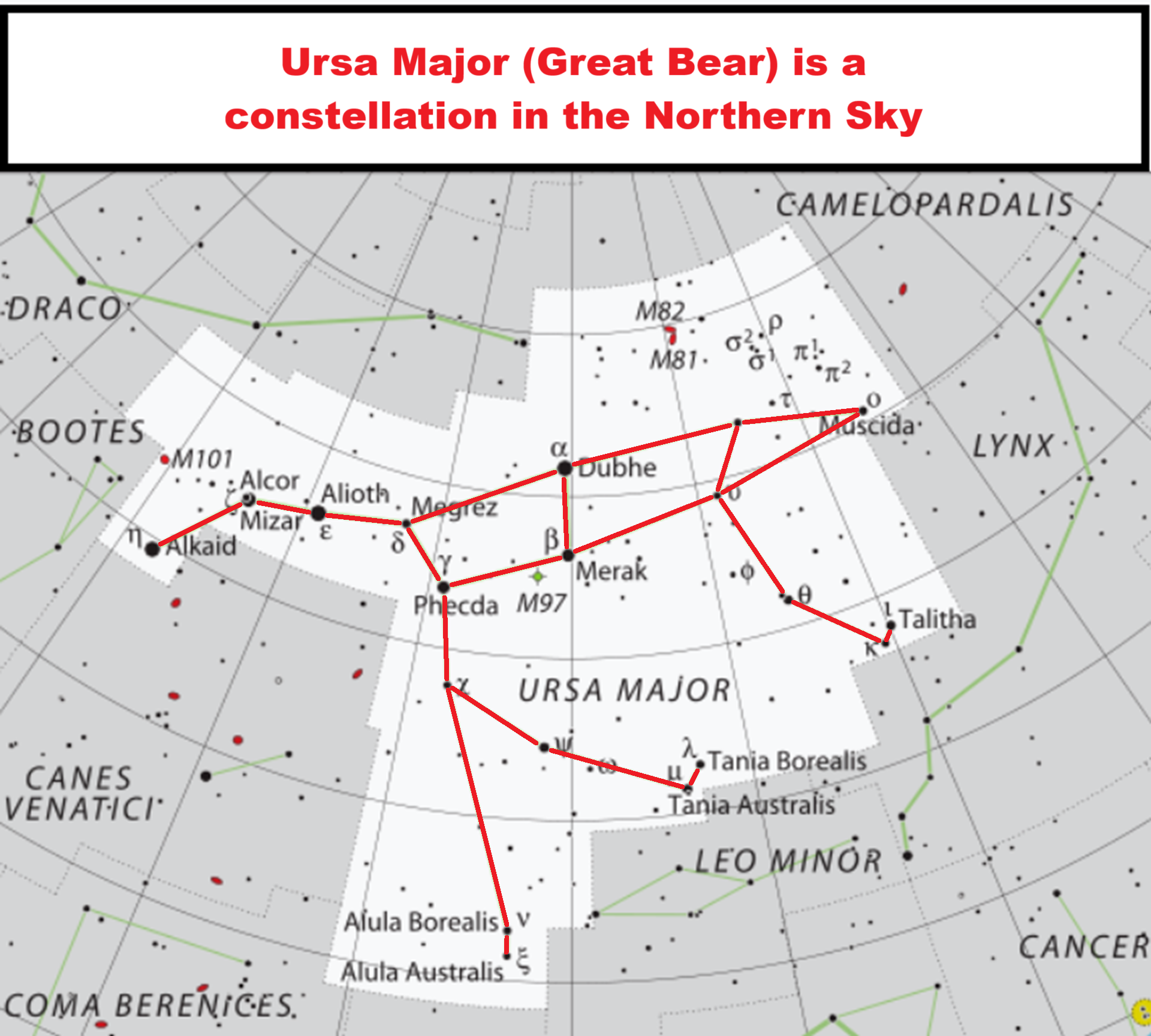

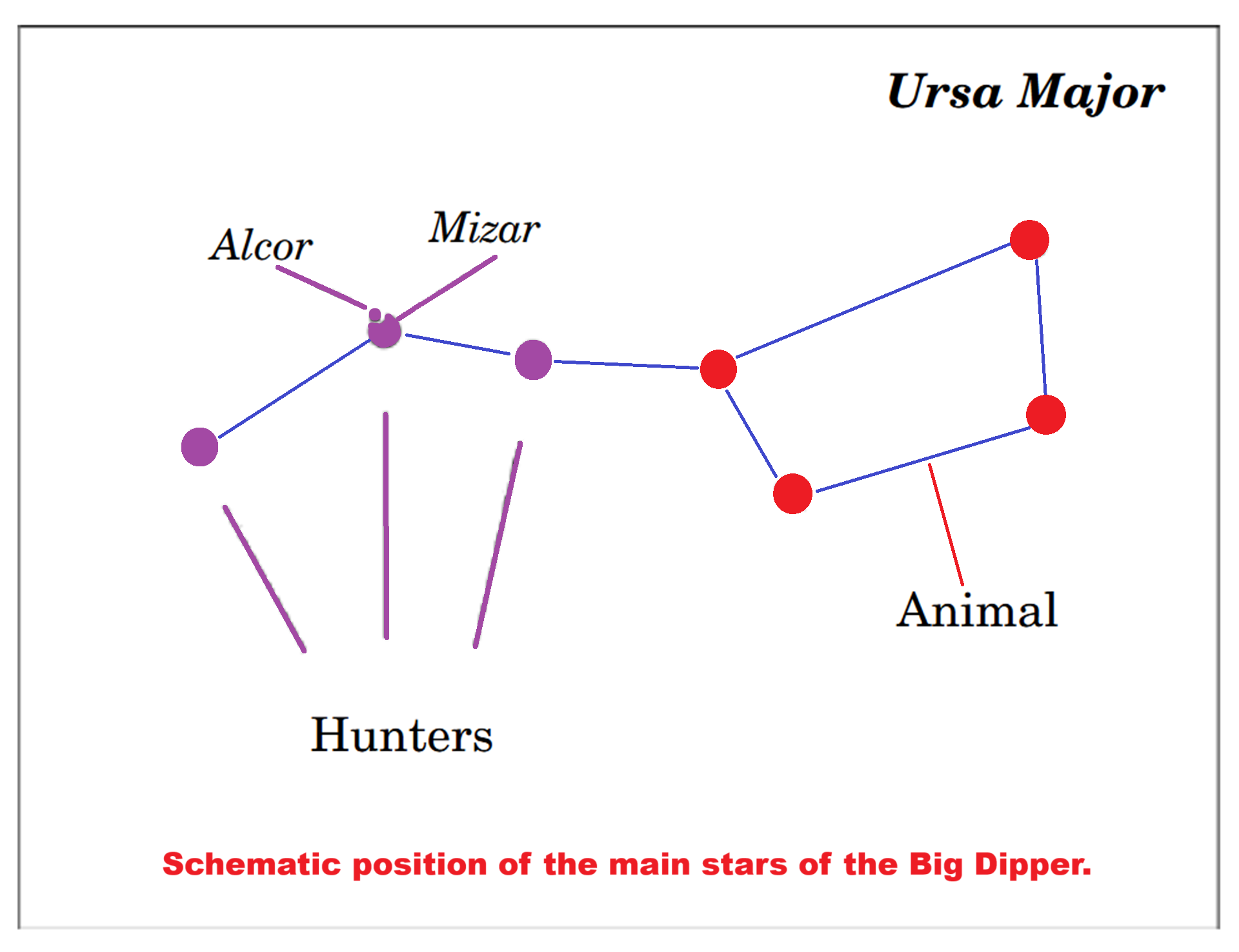

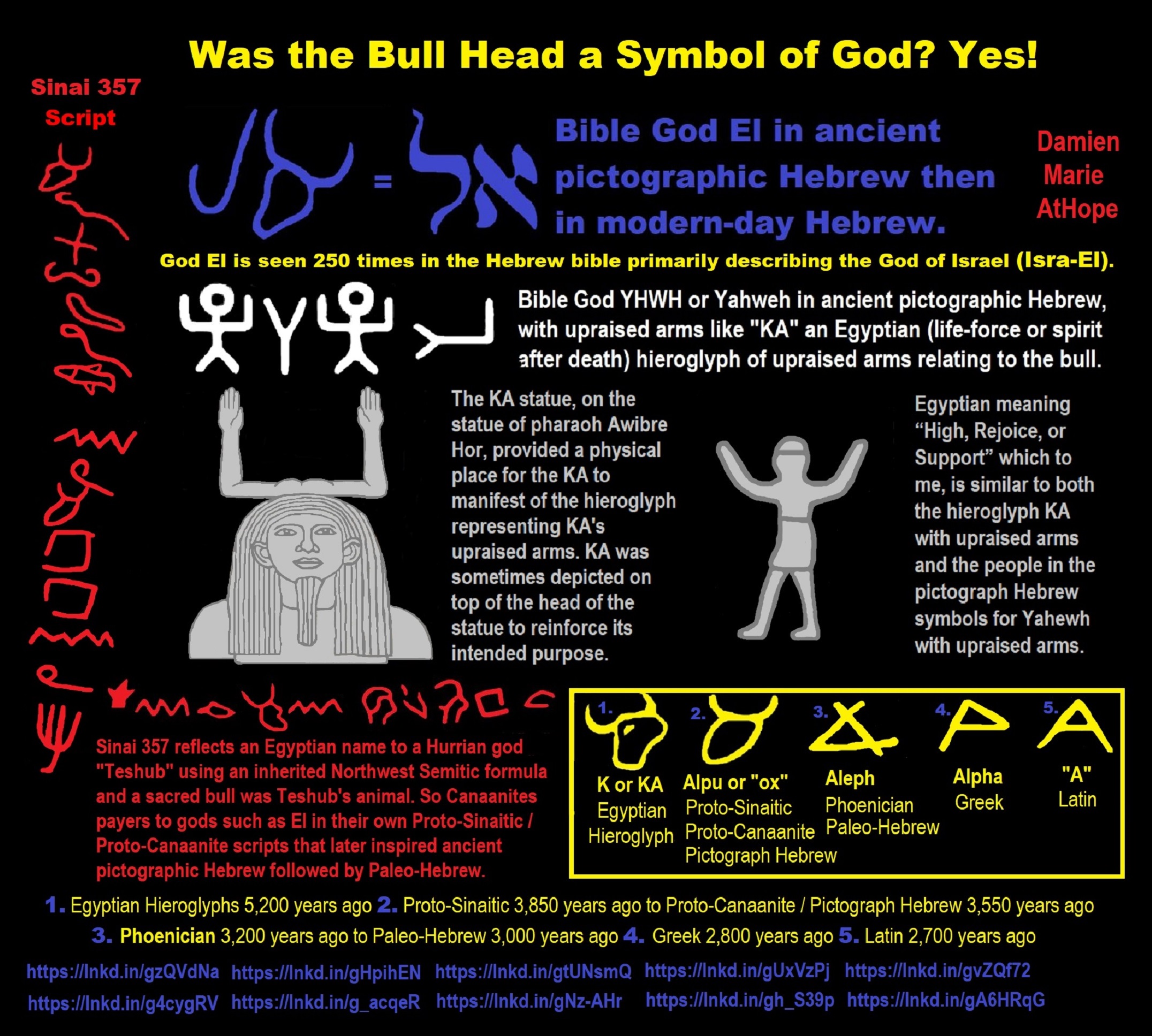

“In the Old Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh, the goddess Ishtar sends Taurus, the Bull of Heaven, to kill Gilgamesh for spurning her advances. Enkidu tears off the bull’s hind part and hurls the quarters into the sky where they become the stars we know as Ursa Major and Ursa Minor. Some locate Gilgamesh as the neighboring constellation of Orion, facing Taurus as if in combat, while others identify him with the sun whose rising on the equinox vanquishes the constellation. In early Mesopotamian art, the Bull of Heaven was closely associated with Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of sexual love, fertility, and warfare. One of the oldest depictions shows the bull standing before the goddess’ standard; since it has 3 stars depicted on its back (the cuneiform sign for “star-constellation”), there is good reason to regard this as the constellation later known as Taurus. The same iconic representation of the Heavenly Bull was depicted in the Dendera zodiac, an Egyptian bas-relief carving in a ceiling that depicted the celestial hemisphere using a planisphere. In these ancient cultures, the orientation of the horns was portrayed as upward or backward. This differed from the later Greek depiction where the horns pointed forward. To the Egyptians, the constellation Taurus was a sacred bull that was associated with the renewal of life in spring. When the spring equinox entered Taurus, the constellation would become covered by the Sun in the western sky as spring began. This “sacrifice” led to the renewal of the land. To the early Hebrews, Taurus was the first constellation in their zodiac and consequently it was represented by the first letter in their alphabet, Aleph.” ref

“In Greek mythology, Taurus was identified with Zeus, who assumed the form of a magnificent white bull to abduct Europa, a legendary Phoenician princess. In illustrations of Greek mythology, only the front portion of this constellation is depicted; this was sometimes explained as Taurus being partly submerged as he carried Europa out to sea. A second Greek myth portrays Taurus as Io, a mistress of Zeus. To hide his lover from his wife Hera, Zeus changed Io into the form of a heifer. Greek mythographer Acusilaus marks the bull Taurus as the same that formed the myth of the Cretan Bull, one of The Twelve Labors of Heracles. Taurus became an important object of worship among the Druids. Their Tauric religious festival was held while the Sun passed through the constellation. Among the arctic people known as the Inuit, the constellation is called Sakiattiat and the Hyades is Nanurjuk, with the latter representing the spirit of the polar bear. Aldebaran represents the bear, with the remainder of the stars in the Hyades being dogs that are holding the beast at bay.” ref

“In Buddhism, legends hold that Gautama Buddha was born when the full moon was in Vaisakha, or Taurus. Buddha’s birthday is celebrated with the Wesak Festival, or Vesākha, which occurs on the first or second full moon when the Sun is in Taurus. In 1990, due to the precession of the equinoxes, the position of the Sun on the first day of summer (June 21) crossed the IAU boundary of Gemini into Taurus. The Sun will slowly move through Taurus at a rate of 1° east every 72 years until approximately 2600, at which point it will be in Aries on the first day of summer.” ref

“The Sumerian guardian deity called lamassu was depicted as hybrids with bodies of either winged bulls or lions and heads of human males. The motif of a winged animal with a human head is common to the Near East, first recorded in Ebla around 3000 BCE. The first distinct lamassu motif appeared in Assyria during the reign of Tiglath-Pileser II as a symbol of power. “The human-headed winged bulls protective genies called shedu or lamassu, … were placed as guardians at certain gates or doorways of the city and the palace. Symbols combining man, bull, and bird, they offered protection against enemies.” ref

“The bull was also associated with the storm and rain god Adad, Hadad or Iškur. The bull was his symbolic animal. He appeared bearded, often holding a club and thunderbolt while wearing a bull-horned headdress. Hadad was equated with the Greek god Zeus; the Roman god Jupiter, as Jupiter Dolichenus; the Indo-European Nasite Hittite storm-god Teshub; the Egyptian god Amun. When Enki distributed the destinies, he made Iškur inspector of the cosmos. In one litany, Iškur is proclaimed again and again as “great radiant bull, your name is heaven” and also called son of Anu, lord of Karkara; twin-brother of Enki, lord of abundance, lord who rides the storm, lion of heaven.” ref

“The Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh depicts the horrors of the rage-fueled deployment of the Bull of Heaven by Ishtar and its slaughter by Gilgamesh and Enkidu as an act of defiance that seals their fates:

Ishtar opened her mouth and said again, “My father, give me the Bull of Heaven to destroy Gilgamesh. Fill Gilgamesh, I say, with arrogance to his destruction; but if you refuse to give me the Bull of Heaven I will break in the doors of hell and smash the bolts; there will be a confusion of people, those above with those from the lower depths. I shall bring up the dead to eat food like the living; and the hosts of the dead will outnumber the living.” Anu said to great Ishtar, “If I do what you desire there will be seven years of drought throughout Uruk when corn will be seedless husks. Have you saved grain enough for the people and grass for the cattle?” Ishtar replied “I have saved grain for the people, grass for the cattle.”…When Anu heard what Ishtar had said he gave her the Bull of Heaven to lead by the halter down to Uruk. When they reached the gates of Uruk the Bull of Heaven went to the river; with his first snort cracks opened in the earth and a hundred young men fell down to death.” ref

“With his second snort cracks opened and two hundred fell down to death. With his third snort cracks opened, Enkidu doubled over but instantly recovered, he dodged aside and leapt onto the Bull and seized it by the horns. The Bull of Heaven foamed in his face, it brushed him with the thick of its tail. Enkidu cried to Gilgamesh, “My friend we boasted that we would leave enduring names behind us. Now thrust your sword between the nape and the horns.” So Gilgamesh followed the Bull, he seized the thick of its tail, he thrust the sword between the nape and the horns and slew the Bull. When they had killed the Bull of Heaven they cut out its heart and gave it to Shamash, and the brothers rested.” ref

“In Ancient Egypt multiple sacred bulls were worshiped. A long succession of ritually perfect bulls were identified by the god’s priests, housed in the temple for their lifetime, then embalmed and buried. The mother-cows of these animals were also revered, and buried in separate locations.

- In the Memphite region, the Apis was seen as the embodiment of Ptah and later of Osiris. Some of the Apis bulls were buried in large sarcophagi in the underground vaults of the Serapeum of Saqqara, which was rediscovered by Auguste Mariette in 1851.

- Mnevis of Heliopolis was the embodiment of Atum–Ra.

- Buchis of Hermonthis was linked with the gods Ra and Montu. The catacombs for these bulls are now known as the Bucheum. Multiple Buchis mummies were found in situ during excavations in the 1930s. Some of their sarcophagi are similar to those in the Serapeum, others are polylithic (made from multiple stones).” ref

“Ka, in Egyptian, is both a religious concept of life-force/power and the word for bull. Andrew Gordon, an Egyptologist, and Calvin Schwabe, a veterinarian, argue that the origin of the ankh is related to two other signs of uncertain origin that often appear alongside it: the was-sceptre, representing “power” or “dominion”, and the djed pillar, representing “stability”. According to this hypothesis, the form of each sign is drawn from a part of the anatomy of a bull, like some other hieroglyphic signs that are known to be based on body parts of animals. In Egyptian belief semen was connected with life and, to some extent, with “power” or “dominion”, and some texts indicate the Egyptians believed semen originated in the bones. Therefore, Calvin and Schwabe suggest the signs are based on parts of the bull’s anatomy through which semen was thought to pass: the ankh is a thoracic vertebra, the djed is the sacrum and lumbar vertebrae, and the was is the dried penis of the bull.” ref

“In Cyprus, bull masks made from real skulls were worn in rites. Bull-masked terracotta figurines and Neolithic bull-horned stone altars have been found in Cyprus. Bulls were a central theme in the Minoan civilization, with bull heads and bull horns used as symbols in the Knossos palace. Minoan frescos and ceramics depict bull-leaping, in which participants of both sexes vaulted over bulls by grasping their horns.” ref

“The Iranian language texts and traditions of Zoroastrianism have several different mythological bovine creatures. One of these is Gavaevodata, which is the Avestan name of a hermaphroditic “uniquely created (-aevo.data) cow (gav-)”, one of Ahura Mazda‘s six primordial material creations that becomes the mythological progenitor of all beneficent animal life. Another Zoroastrian mythological bovine is Hadhayans, a gigantic bull so large that it could straddle the mountains and seas that divide the seven regions of the earth, and on whose back men could travel from one region to another.” ref

“In medieval times, Hadhayans also came to be known as Srīsōk (Avestan *Thrisaok, “three burning places”), which derives from a legend in which three “Great Fires” were collected on the creature’s back. Yet another mythological bovine is that of the unnamed creature in the Cow’s Lament, an allegorical hymn attributed to Zoroaster himself, in which the soul of a bovine (geush urvan) despairs over her lack of protection from an adequate herdsman. In the allegory, the cow represents humanity’s lack of moral guidance, but in later Zoroastrianism, Geush Urvan became a yazata representing cattle. The 14th day of the month is named after her and is under her protection.” ref

“Bulls appear on seals from the Indus Valley civilisation. In The Rig Veda, the earliest collection of Vedic hymns (c. 1500-1000 BCE), Indra is often praised as a Bull (Vṛṣabha – vrsa (he) plus bha (being) or as uksan, a bull aged five to nine years, which is still growing or just reached its full growth). The bull is an icon of power and virile strength in Aryan literature and other Indo-European traditions. Vrsha means “to shower or to spray”, in this context Indra showers strength and virility. Vṛṣabha is also an astrological sign in Indian horoscope systems, corresponding to Taurus.” ref

“The storm god Rudra is called a bull as are the Maruts or storm deities referred to as bulls under the command of Indra, thus Indra is called “bull with bulls.” The following excerpts from The Rig Veda demonstrate these attributes:

“As a bull I call to you, the bull with the thunderbolt, with various aids, O Indra, bull with bulls, greatest killer of Vrtra.” — Atri and the Last Sun” ref

“He the mighty bull who with his seven reins let loose the seven rivers to flow, who with his thunderbolt in his hand hurled down Ruhina as he was climbing up to the sky, he my people is Indra.” — Who is Indra?

“I send praise to the high bull, tawny and white. I bow low to the radiant one. We praise the dreaded name of Rudra.” — Rudra, father of the Maruts” ref.

“Nandi later appears in the Puranas as the primary vahana (mount) and the principal gana (follower) of Shiva. Nandi figures depicted as a seated bull are present at Shiva temples throughout the world. Kao (bull), a supernatural divine bull, appears in ancient Meitei mythology and folklore of Ancient Manipur (Kangleipak). In the legend of the Khamba Thoibi epic, Nongban Kongyamba, a nobleman of ancient Moirang realm, pretended to be an oracle and falsely prophesied that the people of Moirang would lead to miserable lives, if the powerful Kao (bull) roaming freely in the Khuman kingdom, wasn’t offered to the god Thangjing (Old Manipuri: Thangching), the presiding deity of Moirang. Orphan Khuman prince Khamba was chosen to capture the bull, as he was known for his valor and faithfulness.” ref

“Since to capture the bull without killing it was not an easy task, Khamba’s motherly sister Khamnu disclosed to Khamba the secrets of the bull, by means of which the animal could be captured. Bull figurines are common finds on archaeological sites across the Levant; two examples are the 16th century BCE (Middle Bronze Age) bull calf from Ashkelon, and the 12th century BCE (Iron Age I) bull found at the so-called Bull Site in Samaria on the West Bank. Both Baʿal and El were associated with the bull in Ugaritic texts, as it symbolized both strength and fertility.” ref

Exodus 32:4 reads “He took this from their hand, and fashioned it with a graving tool and made it into a molten calf; and they said, ‘This is your god, O Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt’.” ref

Nehemiah 9:18 reads “even when they made an idol shaped like a calf and said, ‘This is your god who brought you out of Egypt!’ They committed terrible blasphemies.” ref

“Calf-idols are referred to later in the Tanakh, such as in the Book of Hosea, which would seem accurate as they were a fixture of near-eastern cultures. Solomon‘s “Molten Sea” basin stood on twelve brazen bulls. Young bulls were set as frontier markers at Dan and Bethel, the frontiers of the Kingdom of Israel. Much later, in Abrahamic religions, the bull motif became a bull demon or the “horned devil” in contrast and conflict to earlier traditions. The bull is familiar in Judeo-Christian cultures from the Biblical episode wherein an idol of the golden calf (Hebrew: עֵגֶּל הַזָהָב) is made by Aaron and worshipped by the Hebrews in the wilderness of the Sinai Peninsula (Book of Exodus). The text of the Hebrew Bible can be understood to refer to the idol as representing a separate god, or as representing Yahweh himself, perhaps through an association or religious syncretism with Egyptian or Levantine bull gods, rather than a new deity in itself.” ref

“Among the Twelve Olympians, Hera‘s epithet Bo-opis is usually translated “ox-eyed” Hera, but the term could just as well apply if the goddess had the head of a cow, and thus the epithet reveals the presence of an earlier, though not necessarily more primitive, iconic view. (Heinrich Schlieman, 1976) Classical Greeks never otherwise referred to Hera simply as the cow, though her priestess Io was so literally a heifer that she was stung by a gadfly, and it was in the form of a heifer that Zeus coupled with her. Zeus took over the earlier roles, and, in the form of a bull that came forth from the sea, abducted the high-born Phoenician Europa and brought her, significantly, to Crete.” ref

“Dionysus was another god of resurrection who was strongly linked to the bull. In a worship hymn from Olympia, at a festival for Hera, Dionysus is also invited to come as a bull, “with bull-foot raging.” “Quite frequently he is portrayed with bull horns, and in Kyzikos he has a tauromorphic image,” Walter Burkert relates, and refers also to an archaic myth in which Dionysus is slaughtered as a bull calf and impiously eaten by the Titans.” ref

“For the Greeks, the bull was strongly linked to the Cretan Bull: Theseus of Athens had to capture the ancient sacred bull of Marathon (the “Marathonian bull”) before he faced the Minotaur (Greek for “Bull of Minos”), who the Greeks imagined as a man with the head of a bull at the center of the labyrinth. Minotaur was fabled to be born of the Queen and a bull, bringing the king to build the labyrinth to hide his family’s shame. Living in solitude made the boy wild and ferocious, unable to be tamed or beaten. Yet Walter Burkert‘s constant warning is, “It is hazardous to project Greek tradition directly into the Bronze Age.” Only one Minoan image of a bull-headed man has been found, a tiny Minoan sealstone currently held in the Archaeological Museum of Chania.” ref

“In the Classical period of Greece, the bull and other animals identified with deities were separated as their agalma, a kind of heraldic show-piece that concretely signified their numinous presence. The religious practices of the Roman Empire of the 2nd to 4th centuries included the taurobolium, in which a bull was sacrificed for the well-being of the people and the state. Around the mid-2nd century, the practice became identified with the worship of Magna Mater, but was not previously associated only with that cult (cultus). Public taurobolia, enlisting the benevolence of Magna Mater on behalf of the emperor, became common in Italy and Gaul, Hispania and Africa. The last public taurobolium for which there is an inscription was carried out at Mactar in Numidia at the close of the 3rd century. It was performed in honor of the emperors Diocletian and Maximian.” ref

“Another Roman mystery cult in which a sacrificial bull played a role was that of the 1st–4th century Mithraic Mysteries. In the so-called “tauroctony” artwork of that cult (cultus), and which appears in all its temples, the god Mithras is seen to slay a sacrificial bull. Although there has been a great deal of speculation on the subject, the myth (i.e. the “mystery”, the understanding of which was the basis of the cult) that the scene was intended to represent remains unknown. Because the scene is accompanied by a great number of astrological allusions, the bull is generally assumed to represent the constellation of Taurus. The basic elements of the tauroctony scene were originally associated with Nike, the Greek goddess of victory. Macrobius lists the bull as an animal sacred to the god Neto/Neito, possibly being sacrifices to the deity.” ref

“Tarvos Trigaranus (the “bull with three cranes”) is pictured on ancient Gaulish reliefs alongside images of gods, such as in the cathedrals at Trier and at Notre Dame de Paris. In Irish mythology, the Donn Cuailnge and the Finnbhennach are prized bulls that play a central role in the epic Táin Bó Cúailnge (“The Cattle Raid of Cooley”). Early medieval Irish texts also mention the tarbfeis (bull feast), a shamanistic ritual in which a bull would be sacrificed and a seer would sleep in the bull’s hide to have a vision of the future king. Pliny the Elder, writing in the first century CE, describes a religious ceremony in Gaul in which white-clad druids climbed a sacred oak, cut down the mistletoe growing on it, sacrificed two white bulls and used the mistletoe to cure infertility.” ref

“The druids—that is what they call their magicians—hold nothing more sacred than the mistletoe and a tree on which it is growing, provided it is Valonia oak. … Mistletoe is rare and when found it is gathered with great ceremony, and particularly on the sixth day of the moon….Hailing the moon in a native word that means ‘healing all things,’ they prepare a ritual sacrifice and banquet beneath a tree and bring up two white bulls, whose horns are bound for the first time on this occasion. A priest arrayed in white vestments climbs the tree and, with a golden sickle, cuts down the mistletoe, which is caught in a white cloak. Then finally they kill the victims, praying to a god to render his gift propitious to those on whom he has bestowed it. They believe that mistletoe given in drink will impart fertility to any animal that is barren and that it is an antidote to all poisons. Bull sacrifices at the time of the Lughnasa festival were recorded as late as the 18th century at Cois Fharraige in Ireland (where they were offered to Crom Dubh) and at Loch Maree in Scotland (where they were offered to Saint Máel Ruba).” ref

Cattle in religion and mythology

There are varying beliefs about cattle in societies and religions.

“Cattle are considered sacred in the Indian religions of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism, as well as in some Chinese folk religion and in African paganism. Cattle played other major roles in many religions, including those of ancient Egypt, ancient Greece, ancient Israel, and ancient Rome. In some regions, especially most states of India, the slaughter of cattle is prohibited and their meat (beef) may be taboo.” ref

“In ancient Egyptian religion, bulls symbolized strength and male sexuality and were linked with aggressive deities such as Montu and virile deities such as Min. Some Egyptian cities kept sacred bulls that were said to be incarnations of divine powers, including the Mnevis bull, Buchis bull, and the Apis bull, which was regarded as a manifestation of the god Ptah and was the most important sacred animal in Egypt. Cows were connected with fertility and motherhood. One of several ancient Egyptian creation myths said that a cow goddess, Mehet-Weret, who represented the primeval waters that existed before creation, gave birth to the sun at the beginning of time. The sky was sometimes envisioned as a goddess in the form of a cow, and several goddesses, including Hathor, Nut, and Neith, were equated with this celestial cow. The Egyptians did not regard cattle as uniformly positive. Wild bulls, regarded as symbols of the forces of chaos, could be hunted and ritually killed.” ref

“As cattle were a central part of the pastoralist economy of Ancient Nubia, Africa, they also played a prominent role in their culture and mythology, as evidenced by their inclusion in burials and rock art. Starting in the Neolithic period, cattle skulls, also known as bucrania, were often placed alongside human burials. Bucrania were a status symbol, and they were used frequently in adult male burials, occasionally in adult female burials, and rarely in child burials. In cemeteries at Kerma, there is a strong correlation between the number of bucrania and the quantity and lavishness of other grave goods. Dozens if not hundreds of cattle were often slaughtered as tribute for the burial of one individual; 400 bucrania were found at one tumulus alone at Kerma. The use of cattle skulls rather than those of sheep or goats reveals the importance of cattle in their pastoral economy, as well as the cultural associations of cattle with wealth, prosperity, and passage into the afterlife. Sometimes complete cattle were buried alongside their owner, symbolic of their relationship continuing into the afterlife.” ref

“Beginning in the third millennium BCE, cattle became the most popular motif in Nubian rock art. The bodies are usually depicted in profile, while the horns are facing forward. The length and shape of the horns and the pattern on the hide varied widely. Human silhouettes are often drawn alongside the cattle, symbolic of the important symbiotic relationship between cattle and humans. For pastoralists, drawing cattle may have also been a way to ensure the health of their herd. The role of cattle in Nubian mythology is more covert than in Egypt to the north, where several gods are often depicted as cattle; however, the significance of cattle in Nubian culture is evident in burial practices, understandings of the afterlife, and rock art.” ref

“Hinduism specifically considers the zebu (Bos indicus) to be sacred. Respect for the lives of animals including cattle, diet in Hinduism and vegetarianism in India are based on the Hindu ethics. The Hindu ethics are driven by the core concept of Ahimsa, i.e. non-violence towards all beings, as mentioned in the Chandogya Upanishad (~ 800 BCE). By mid 1st millennium BCE, all three major religions – Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism – were championing non-violence as an ethical value, and something that impacted one’s rebirth. By about 200 CE, food and feasting on animal slaughter were widely considered as a form of violence against life forms, and became a religious and social taboo. India, which has 79.80% Hindu population as of (2011 census), had the lowest rate of meat consumption in the world according to the 2007 UN FAO statistics, and India has more vegetarians than the rest of the world put together.” ref

“According to Ludwig Alsdorf, “Indian vegetarianism is unequivocally based on ahimsa (non-violence)” as evidenced by ancient smritis and other ancient texts of Hinduism.” He adds that the endearment and respect for cattle in Hinduism is more than a commitment to vegetarianism and has become integral to its theology. The respect for cattle is widespread but not universal. Animal sacrifices have been rare among the Hindus outside a few eastern states. To the majority of modern Indians, states Alsdorf, respect for cattle and disrespect for slaughter is a part of their ethos, and there is “no ahimsa without renunciation of meat consumption”. The cow in Hindu society is traditionally identified as a caretaker and a maternal figure, and Hindu society honors the cow as a symbol of unselfish giving, selfless sacrifice, gentleness, and tolerance.” ref

“Several scholars explain the veneration for cows among Hindus in economic terms, including the importance of dairy in the diet, the use of cow dung as fuel and fertilizer, and the importance that cattle have historically played in agriculture. Ancient texts such as Rig Veda, Puranas highlight the importance of cattle. The scope, extent, and status of cows throughout ancient India is a subject of debate. Cattle, including cows, were neither inviolable nor as revered in ancient times as they were later. A Gryhasutra recommends that beef be eaten by the mourners after a funeral ceremony as a ritual rite of passage. In contrast, the Vedic literature is contradictory, with some suggesting ritual slaughter and meat consumption, while others suggesting a taboo on meat eating. Many ancient and medieval Hindu texts debate the rationale for a voluntary stop to cow slaughter and the pursuit of vegetarianism as a part of a general abstention from violence against others and all killing of animals.” ref

“The interdiction of the meat of the bounteous cow as food was regarded as the first step to total vegetarianism. Dairy cows are called aghnya “that which may not be slaughtered” in the Rigveda. Yaska, the early commentator of the Rigveda, gives nine names for cow, the first being “aghnya”. The literature relating to cow veneration became common in 1st millennium CE, and by about 1000 CE vegetarianism, along with a taboo against beef, became a well accepted mainstream Hindu tradition. This practice was inspired by the beliefs in Hinduism that a soul is present in all living beings, life in all its forms is interconnected, and non-violence towards all creatures is the highest ethical value. The god Krishna and his Yadava kinsmen are associated with cows, adding to its endearment.” ref

“The cow veneration in ancient India during the Vedic era, the religious texts written during this period called for non-violence towards all bipeds and quadrupeds, and often equated killing of a cow with the killing of a human being specifically a Brahmin. The hymn 8.3.25 of the Hindu scripture Atharvaveda (~1200–1500 BCE) condemns all killings of men, cattle, and horses, and prays to god Agni to punish those who kill.” ref

“In the Puranas, which are part of the Hindu texts, the earth-goddess Prithvi was in the form of a cow, successively milked of beneficent substances for the benefit of humans, by deities starting with the first sovereign: Prithu milked the cow to generate crops for humans to end a famine. Kamadhenu, the miraculous “cow of plenty” and the “mother of cows” in certain versions of the Hindu mythology, is believed to represent the generic sacred cow, regarded as the source of all prosperity. In the 19th century, a form of Kamadhenu was depicted in poster-art that depicted all major gods and goddesses in it. Govatsa Dwadashi, which marks the first day of Diwali celebrations, is the main festival connected to the veneration and worship of cows as chief source of livelihood and religious sanctity in India, wherein the symbolism of motherhood is most apparent with the sacred cows Kamadhenu and her daughter Nandini.” ref

“Jainism is against violence to all living beings, including cattle. According to the Jaina sutras, humans must avoid all killing and slaughter because all living beings are fond of life, they suffer, they feel pain, they like to live, and long to live. All beings should help each other live and prosper, according to Jainism, not kill and slaughter each other. In the Jain religious tradition, neither monks nor laypersons should cause others or allow others to work in a slaughterhouse. Jains believe that vegetarian sources can provide adequate nutrition, without creating suffering for animals such as cattle. According to some Jain scholars, slaughtering cattle increases ecological burden from human food demands since the production of meat entails intensified grain demands, and reducing cattle slaughter by 50 percent would free up enough land and ecological resources to solve all malnutrition and hunger worldwide. The Jain community leaders, states Christopher Chapple, has actively campaigned to stop all forms of animal slaughter including cattle.” ref

“The texts of Buddhism state ahimsa to be one of five ethical precepts, which requires a practicing Buddhist to “refrain from killing living beings”. Slaughtering cow has been a taboo, with some texts suggesting that taking care of a cow is a means of taking care of “all living beings”. Cattle are seen in some Buddhist sects as a form of reborn human beings in the endless rebirth cycles in samsara, protecting animal life and being kind to cattle and other animals is good karma. Not only do some, mainly Mahayana, Buddhist texts state that killing or eating meat is wrong, it urges Buddhist laypersons to not operate slaughterhouses, nor trade in meat. Indian Buddhist texts encourage a plant-based diet.” ref

“According to Saddhatissa, in the Brahmanadhammika Sutta, the Buddha “describes the ideal mode of life of Brahmins in the Golden Age” before him as follows: Like mother (they thought), father, brother or any other kind of kin, cows are our kin most excellent from whom come many remedies. Givers of good and strength, of good complexion and the happiness of health, having seen the truth of this cattle, they never killed. Those Brahmins, then by Dharma, did what should be done, not what should not, and so aware they graceful were, well-built, fair-skinned, of high renown. While in the world, this lore was found, these people happily prospered. — Buddha, Brahmanadhammika Sutta 13.24, Sutta Nipāta” ref

“Saving animals from slaughter for meat, is believed in Buddhism to be a way to acquire merit for better rebirth. According to Richard Gombrich, there has been a gap between Buddhist precepts and practice. Vegetarianism is admired, states Gombrich, but often it is not practiced. Nevertheless, adds Gombrich, there is a general belief among Theravada Buddhists that eating beef is worse than other meat and the ownership of cattle slaughterhouses by Buddhists is relatively rare. Meat eating remains controversial within Buddhism, with most Theravada sects allowing it, reflecting early Buddhist practice, and most Mahayana sects forbidding it. Early suttas indicate that the Buddha himself ate meat and was clear that no rule should be introduced to forbid meat eating to monks. The consumption, however, appears to have been limited to pork, chicken and fish and may well have excluded cattle.” ref

“The term geush urva means “the spirit of the cow” and is interpreted as the soul of the earth. In the Ahunavaiti Gatha, Zoroaster accuses some of his co-religionists of abusing the cow while Ahura Mazda tells him to protect them. After fleeing to India, many Zoroastrians stopped eating beef out of respect for Hindus living there. The lands of Zoroaster and the Vedic priests were those of cattle breeders. The 9th chapter of the Vendidad of the Avesta expounds the purificatory power of cow urine. It is declared to be a panacea for all bodily and moral evils and features prominently in the 9-night purification ritual Barashnûm.” ref

“According to the Bible, the Israelites worshipped a cult image of a golden calf when the prophet Moses went up to Mount Sinai. Moses considered this a great sin against God. As a result of their abstention from the act, the Levite tribe attained a priestly role. A cult of golden calves appears later during the rule of Jeroboam. According to the Hebrew Bible, an unblemished red cow was an important part of ancient Jewish rituals. The cow was sacrificed and burned in a precise ritual, and the ashes were added to water used in the ritual purification of a person who had come in to contact with a human corpse. The ritual is described in the Book of Numbers in Chapter 19, verses 1–14.” ref

“Observant Jews study this passage every year as part of the weekly Torah portion called Chukat. A contemporary Jewish organization called the Temple Institute is trying to revive this ancient religious observance. Traditional Judaism considers beef kosher and permissible as food, as long as the cow is slaughtered in a religious ritual called shechita, and the meat is not served in a meal that includes any dairy foods. Some Jews committed to Jewish vegetarianism believe that Jews should refrain from slaughtering animals altogether and have condemned widespread cruelty towards cattle on factory farms. The red heifer or red cow is a particular kind of cow brought to priests for sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible. Jews and some Christian fundamentalists believe that once a red heifer is born they will be able to rebuild the Third Temple on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.” ref

“Oxen are one of the animals sacrificed by Greek Orthodox believers in some villages of Greece. It is especially associated with the feast of Saint Charalambos. This practice of kourbania has been repeatedly criticized by church authorities. The ox is the symbol of Luke the Evangelist. Among the Visigoths, the oxen pulling the wagon with the corpse of Saint Emilian lead to the correct burial site (San Millán de la Cogolla, La Rioja). In Greek mythology, the Cattle of Helios pastured on the island of Thrinacia, which is believed to be modern Sicily. Helios, the sun god, is said to have had seven herds of oxen and seven flocks of sheep, each numbering fifty head. A hecatomb was a sacrifice to the gods Apollo, Athena, and Hera, of 100 cattle (hekaton = one hundred).” ref

“The Greek gods also transformed themselves or others into cattle as a form of deception or punishment, such as in the myths of Io and Europa. In the myth of Pasiphaë, she falls in love with a bull as punishment by Poseidon. She gives birth to the Minotaur, a human-bull hybrid. In the ancient Anatolian civilization Hatti, the storm god was closely linked to a bull. Tarvos Trigaranus (the “bull with three cranes”) is pictured on ancient Gaulish reliefs alongside images of gods. There is evidence that ancient Celtic peoples sacrificed animals, which were almost always cattle or other livestock. Early medieval Irish texts mention the tarbfeis (bull feast), a shamanistic ritual in which a bull would be sacrificed and a seer would sleep in the bull’s hide to have a vision of the future king.” ref

“Cattle appear often in Irish mythology. The Glas Gaibhnenn is a mythical prized cow that could produce plentiful supplies of milk, while Donn Cuailnge and Finnbhennach are prized bulls that play a central role in the epic Táin Bó Cúailnge (“The Cattle Raid of Cooley”). The mythical lady Flidais, the main figure in the Táin Bó Flidhais, owns a herd of magical cattle.The name of the goddess of the River Boyne, Bóinn, comes from Archaic Irish *Bóu-vinda meaning the “bright or white cow”; while the name of the Corcu Loígde means “tribe of the calf goddess”. In Norse mythology, the primeval cow Auðumbla suckled Ymir, the ancestor of the frost giants, and licked Búri, Odin‘s grandfather and ancestor of the gods, out of the ice.” ref

“A beef taboo in ancient China was historically a dietary restriction, particularly among the Han Chinese, as oxen and buffalo (bovines) are useful in farming and are respected. During the Zhou dynasty, they were not often eaten, even by emperors. Some emperors banned killing cows. Beef is not recommended in Chinese medicine, as it is considered a hot food and is thought to disrupt the body’s internal balance. In written sources (including anecdotes and Daoist liturgical texts), this taboo first appeared in the 9th to 12th centuries (Tang–Song transition, with the advent of pork meat.)” ref

“By the 16th to 17th centuries, the beef taboo had become well accepted in the framework of Chinese morality and was found in morality books (善書), with several books dedicated exclusively to this taboo. The beef taboo came from a Chinese perspective that relates the respect for animal life and vegetarianism (ideas shared by Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism, and state protection for draught animals.) In Chinese society, only ethnic and religious groups not fully assimilated (such as the Muslim Huis and the Miao) and foreigners consumed this meat. This taboo, among Han Chinese, led Chinese Muslims to create a niche for themselves as butchers who specialized in slaughtering oxen and buffalo. Occasionally, some cows seen weeping before slaughter are often released to temples nearby.” ref

“Islam allows the slaughter of cows and consumption of beef, as long as the cow is slaughtered in a religious ritual called dhabīḥah or zabiha similar to the Jewish shechita. Although slaughter of cattle plays a role in a major Muslim holiday, Eid al-Adha, many rulers of the Mughal Empire had imposed a ban on the slaughter of cows owing to the large Hindu and Jain populations living under their rule. The second and longest surah of the Quran is named Al-Baqara (“The Cow”). Out of the 286 verses of the surah, 7 mention cows (Al Baqarah 67–73). The name of the surah derives from this passage in which Moses orders his people to sacrifice a cow in order to resurrect a man murdered by an unknown person. Per the passage, the “Children of Israel” quibbled over what kind of cow was meant when the sacrifice was ordered.” ref

“While addressing to children of Israel, it was said:

And when We did appoint for Moses forty nights (of solitude), and then ye chose the calf, when he had gone from you, and were wrong-doers. Then, even after that, We pardoned you in order that ye might give thanks. And when We gave unto Moses the Scripture and the criterion (of right and wrong), that ye might be led aright. And when Moses said unto his people: O my people! Ye have wronged yourselves by your choosing of the calf (for worship) so turn in penitence to your Creator, and kill (the guilty) yourselves. That will be best for you with your Creator, and He will relent toward you. Lo! He is the Relenting, the Merciful. (Al-Quran 2:51–54)” ref

“And when Moses said unto his people: Lo! God commandeth you that ye sacrifice a cow, they said: Dost thou make game of us ? He answered: God forbid that I should be among the foolish! They said: Pray for us unto thy Lord that He make clear to us what (cow) she is. (Moses) answered: Lo! He saith, Verily she is a cow neither with calf nor immature; (she is) between the two conditions; so do that which ye are commanded. They said: Pray for us unto thy Lord that He make clear to us of what colour she is. (Moses) answered: Lo! He saith: Verily she is a yellow cow. Bright is her colour, gladdening beholders. They said: Pray for us unto thy Lord that He make clear to us what (cow) she is. Lo! cows are much alike to us; and Lo! if God wills, we may be led aright. (Moses) answered: Lo! He saith: Verily she is a cow unyoked; she plougheth not the soil nor watereth the tilth; whole and without mark. They said: Now thou bringest the truth. So they sacrificed her, though almost they did not. And (remember) when ye slew a man and disagreed concerning it, and God brought forth that which ye were hiding. And We said: Smite him with some of it. Thus God bringeth the dead to life and showeth you His portents so that ye may understand. (Al-Quran 2:67–73)” ref

“Classical Sunni and Shia commentators recount several variants of this tale. Per some of the commentators, though any cow would have been acceptable, but after they “created hardships for themselves” and the cow was finally specified, it was necessary to obtain it at any cost. Historically, there was a beef taboo in ancient Japan, as a means of protecting the livestock population and due to Buddhist influence. Meat-eating had long been taboo in Japan, beginning with a decree in 675 that banned the consumption of cattle, horses, dogs, monkeys, and chickens, influenced by the Buddhist prohibition of killing. In 1612, the shōgun declared a decree that specifically banned the killing of cattle.” ref

“This official prohibition was in place until 1872, when it was officially proclaimed that Emperor Meiji consumed beef and mutton, which transformed the country’s dietary considerations as a means of modernizing the country, particularly with regard to consumption of beef. With contact from Europeans, beef increasingly became popular, even though it had previously been considered barbaric. Several shrines and temples are decorated with cow figurines, which are believed to cure illnesses when stroked.” ref

Herding societies

“The best known and purest pastoral nomads are found in the enormous arid belt from Morocco to Manchuria, passing through North Africa, Arabia, Iran, Turkistan, Tibet, and Mongolia. They include people as diverse as the Arabized North Africans and the Mongol hordes. Other less specialized and successful pastoralists include the Siberian reindeer herders, cattle herders of the grasslands of north-central Africa, and the Khoekhoe and Herero of southern Africa.” ref, ref

Evidence for the early dispersal of domestic sheep into Central Asia

“Archaeological and biomolecular evidence from Obishir V in southern Kyrgyzstan, establishing the presence of domesticated sheep by ca. 6,000 BCE. Zooarchaeological and collagen peptide mass fingerprinting show exploitation of Ovis and Capra, while cementum analysis of intact teeth implicates possible pastoral slaughter during the fall season. Most significantly, ancient DNA reveals these directly dated specimens as the domestic O. aries, within the genetic diversity of domesticated sheep lineages. Together, these results provide the earliest evidence for the use of livestock in the mountains of the Ferghana Valley, predating previous evidence by 3,000 years and suggesting that domestic animal economies reached the mountains of interior Central Asia far earlier than previously recognized.” ref, ref

Tutelary Deities

“A tutelary is a deity or spirit who is a guardian, patron, or protector of a particular place, geographic feature, person, lineage, nation, culture, or occupation. The etymology of “tutelary” expresses the concept of safety, and thus of guardianship. Chinese folk religion, both past and present, includes a myriad of tutelary deities. Exceptional individuals may become deified after death. In Hinduism, tutelary deities are known as ishta-devata and Kuldevi or Kuldevta. Gramadevata are guardian deities of villages. In Korean shamanism, jangseung and sotdae were placed at the edge of villages to frighten off demons. They were also worshiped as deities. In Shinto, the spirits, or kami, which give life to human bodies come from nature and return to it after death. Ancestors are therefore themselves tutelaries to be worshiped. In Philippine animism, Diwata or Lambana are deities or spirits that inhabit sacred places like mountains and mounds and serve as guardians. Thai provincial capitals have tutelary city pillars and palladiums. The guardian spirit of a house is known as Chao Thi or Phra Phum. Almost every Buddhist household in Thailand has a miniature shrine housing this tutelary deity, known as a spirit house. And in Tibetan Buddhism has Yidam as a tutelary deity.” ref

Grandmother-Mother Ancestor Spirits

“Ancestor worship is perhaps the world’s oldest religion. Some anthropologists theorize that it grew out of belief in some societies that dead people still exist in some form because they appear in dreams. Ancestor worship involves the belief that the dead live on as spirits and that it is the responsibility of their family members and descendants to make sure that they are well taken care of. If they are not they may come back and cause trouble to the family members and descendants that have ignored or disrespected them. Unhappy dead ancestors are greatly feared and every effort is made to make sure they are comfortable in the afterlife. Accidents and illnesses are often attributed to deeds performed by the dead and cures are often attempts to placate them.” ref

“In some societies, people go out of their way to be nice to one another, especially older people, out of fear of the nasty things they might do when they die. Ancestor worship is found in many forms in cultures throughout the world, Veneration of ancestors is regarded as a means through which an individual can assure his or her own immortality. Children are valued because they could provide for the spirits of their parents after death. Family members who remained together and venerated their forebears with strict adherence to prescribed ritual find comfort in the belief that the souls of their ancestors are receiving proper spiritual nourishment and that they are insuring their own soul’s nourishment after death.” ref

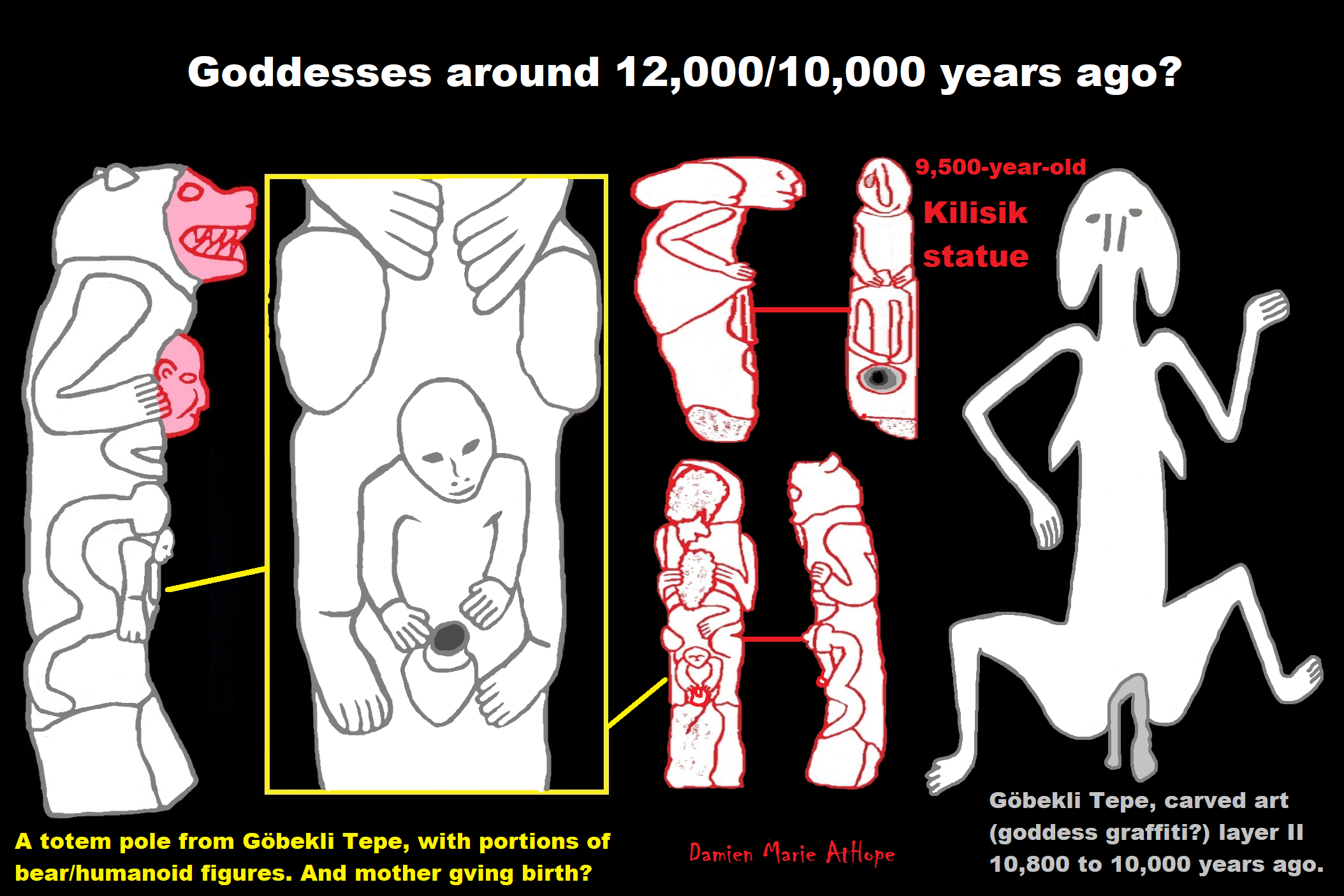

“Göbekli Tepe, engraving of a female person (seemingly in the birth position) and the Bear totem pole

giving birth to a human with pottery are from layer II, around 10,000 years ago.” ref

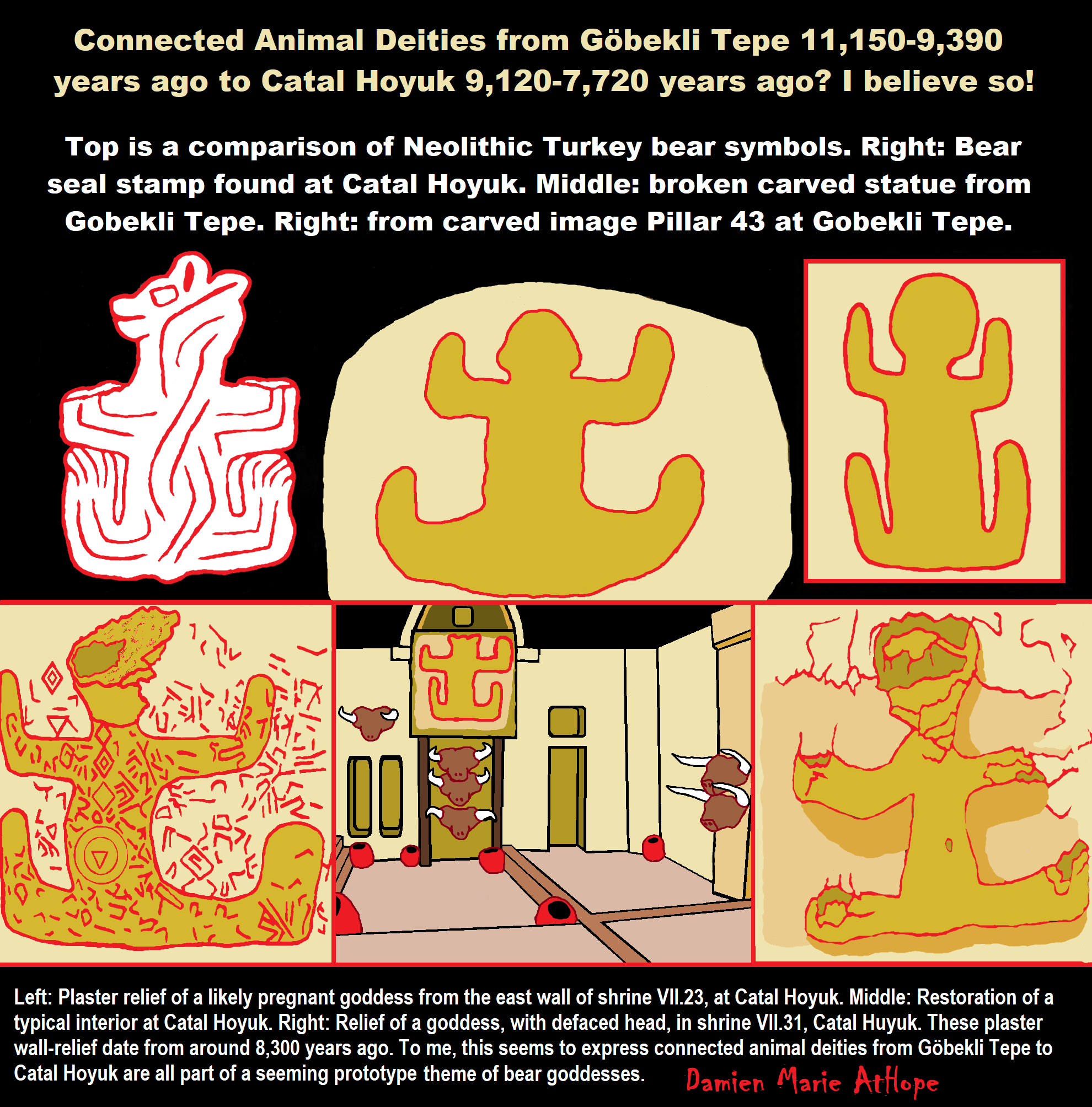

“Göbekli Tepe is a Neolithic archaeological site in Upper Mesopotamia (al-Jazira) in modern-day Turkey. The settlement was inhabited from around 9500 BCE to at least 8000 BCE or around 11,500 to 10,000 years ago, during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic. Elements of village life appeared as early as 10,000 years before the Neolithic in places, and the transition to agriculture took thousands of years, with different paces and trajectories in different regions. It is famous for its large circular structures that contain massive stone pillars – among the world’s oldest known megaliths. Many of these pillars are decorated with anthropomorphic details, clothing, and sculptural reliefs of wild animals, providing archaeologists rare insights into prehistoric religion and the particular iconography of the period. The 15 m (50 ft) high, 8 ha (20-acre) tell is densely covered with ancient domestic structures and other small buildings, quarries, and stone-cut cisterns from the Neolithic, as well as some traces of activity from later periods. The site was first used at the dawn of the southwest Asian Neolithic period, which marked the appearance of the oldest permanent human settlements anywhere in the world. Prehistorians link this Neolithic Revolution to the advent of agriculture but disagree on whether farming caused people to settle down or vice versa. Göbekli Tepe, a monumental complex built on a rocky mountaintop with no clear evidence of agricultural cultivation, has played a prominent role in this debate. Recent findings suggest a settlement at Göbekli Tepe, with domestic structures, extensive cereal processing, a water supply, and tools associated with daily life. This contrasts with a previous interpretation of the site as a sanctuary used by nomads, with few or no permanent inhabitants. No definitive purpose has been determined for the megalithic structures, which have been popularly described as the “world’s first temple[s]”. They were likely roofed and appear to have regularly collapsed, been inundated by slope slides, and subsequently repaired or rebuilt. The iconography of these objects is similar to that of the pillars, mostly depicting animals but also humans, again primarily male.” ref

“The architecture and iconography are similar to other contemporary sites in the vicinity, such as Karahan Tepe. Evidence indicates the inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe were hunter-gatherers who supplemented their diet with early forms of domesticated cereal and lived in villages for at least part of the year. Archaeologists divide the Pre-Pottery Neolithic into two subperiods: the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA, c. 9600–8800 BCE) and the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB, c. 8800 and 7000 BCE). The earliest phases at Göbekli Tepe have been dated to the PPNA; later phases to the PPNB. PPN villages consisted mainly of clusters of stone or mud brick houses, but sometimes also substantial monuments and large buildings. These include the tower and walls at Tell es-Sultan (Jericho), as well as large, roughly contemporaneous circular buildings at Göbekli Tepe, Nevalı Çori, Çayönü, Wadi Feynan 16, Jerf el-Ahmar, Tell ‘Abr 3, and Tepe Asiab. Archaeologists typically associate these structures with communal activities which, together with the communal effort needed to build them, helped to maintain social interactions in PPN communities as they grew in size. The T-shaped pillar tradition seen at Göbekli Tepe is unique to the Urfa region but is found at most PPN sites. These include Nevalı Çori, Hamzan Tepe, Karahan Tepe, Harbetsuvan Tepesi, Sefer Tepe, and Taslı Tepe. Other stone stelae—without the characteristic T shape—have been documented at contemporary sites further afield, including Çayönü, Qermez Dere, and Gusir Höyük.” ref

Animal Deities? Are the Bull symbol on the side and the big cat a Possible Type of or similar to a Tutelary Deity? Then there is yet another grouping of three animals, one being an odd bulged head bull, could they possibly be a Type of or similar to Tutelary Deities?

Göbekli Tepe involves a male-dominated society?

“So far, every known depiction – as long as their sex is clearly recognizable – seems to be male, be it animals or humans. The only exception is a later added graffiti of a single woman on a stone slab in one of the later PPN B buildings. While this may somehow denote the site of Göbekli Tepe as a refuge of male hunters, it does, of course, not at all mean that women did not play a role in PPN society. There is a wide range of finds clearly connected to women in the contemporary settlements for instance – however, at Göbekli Tepe they (respectively their activity) remain invisible as of yet.” ref

I see a similarity in the bear art that I think could be female as well as doing the same spread leg gesture.

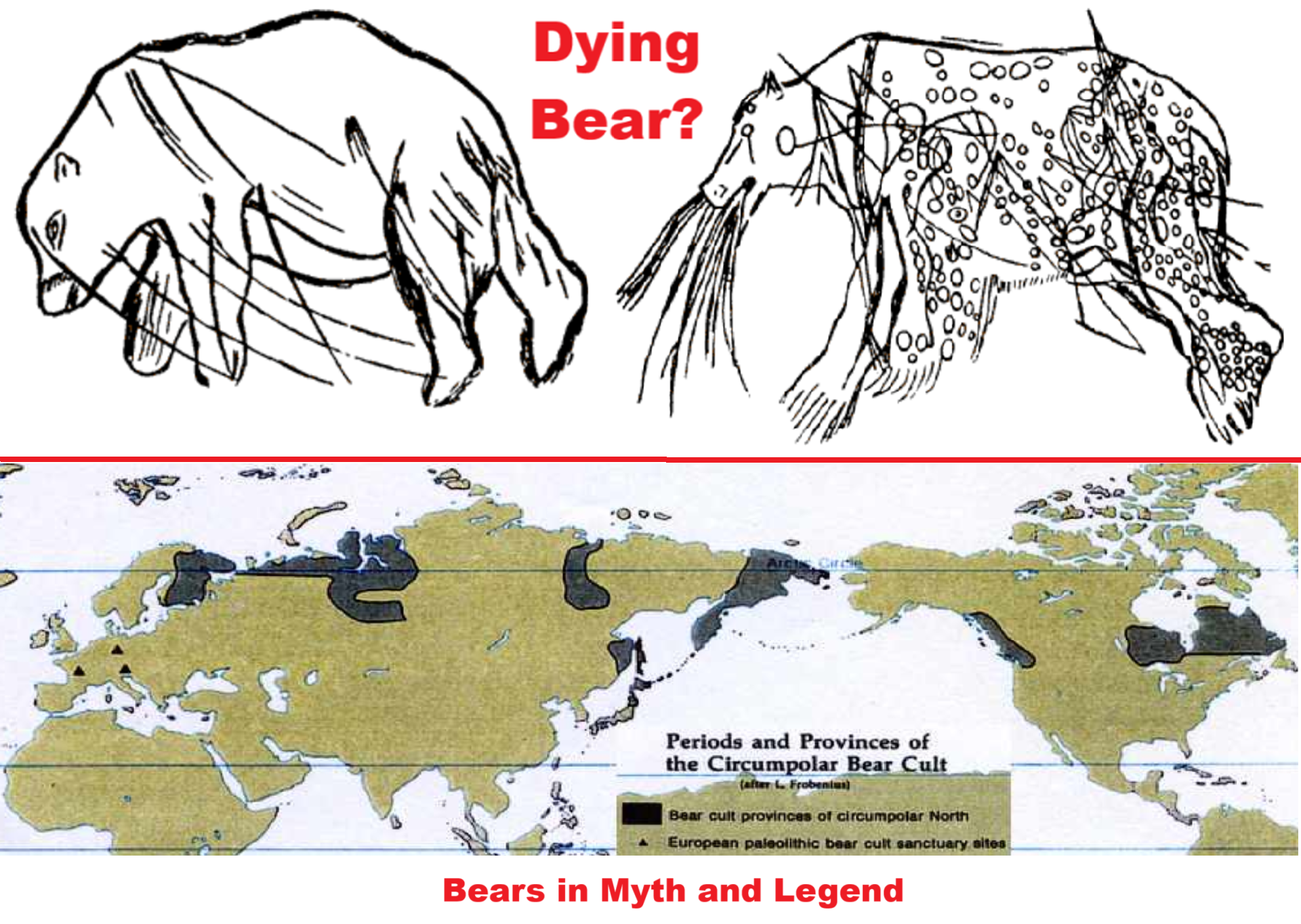

Women and Sacred (BEARS) Animals?

“In the “hunters’ religion” preserved among the northern Finno-Ugric peoples, bear ceremonies are central. The Khanty, Mansi, Nenets, Sami, Finns, and Karelians have all been acquainted with myths and rites connected with the bear. The myths recount that the bear is of heavenly origin and is the son of the god of the sky; it descends from heaven and, when it dies, returns there. There is also a story about a marriage between a bear and a woman from which a tribe of the Skolt Sami (in Finland) is said to be descended. The bear-killing ceremony is divided into two acts—the killing itself and the feast afterward. Killing a bear that was protected by a forest guardian spirit involved a complicated ritual, which ended with bringing the bear home. Women believed that they had to keep at a distance so that the bear would not make them pregnant.” ref

Ancestor veneration in China: “Chinese traditional primordial religion” has been defined as the traditional religious system organized around the worship of ancestor-gods. Chinese ancestor worship, or Chinese ancestor veneration, also called the Chinese patriarchal religion, is an aspect of the Chinese traditional religion that revolves around the ritual celebration of the deified ancestors and tutelary deities of people with the same surname organized into lineage societies in ancestral shrines. Ancestors, their ghosts, or spirits, and gods are considered part of “this world”, that is, they are neither supernatural (in the sense of being outside nature) nor transcendent in the sense of being organized beyond nature. The ancestors are humans who have become godly beings, beings who keep their individual identities. For this reason, Chinese religion is founded on the veneration of ancestors. Ancestors are believed to be a means of connection to the supreme power of god Tian as they are considered embodiments or reproducers of the creative order of Heaven.” ref

“A household deity is a deity or spirit that protects the home, looking after the entire household or certain key members. It has been a common belief in pagan religions as well as in folklore across many parts of the world. Household deities fit into two types; firstly, a specific deity – typically a goddess – often referred to as a hearth goddess or domestic goddess who is associated with the home and hearth, with examples including the Greek Hestia and Norse Frigg. The second type of household deities are those that are not one singular deity, but a type, or species of animistic deity, who usually have lesser powers than major deities. This type was common in the religions of antiquity, such as the Lares of ancient Roman religion, the Gashin of Korean shamanism, and Cofgodas of Anglo-Saxon paganism.” ref

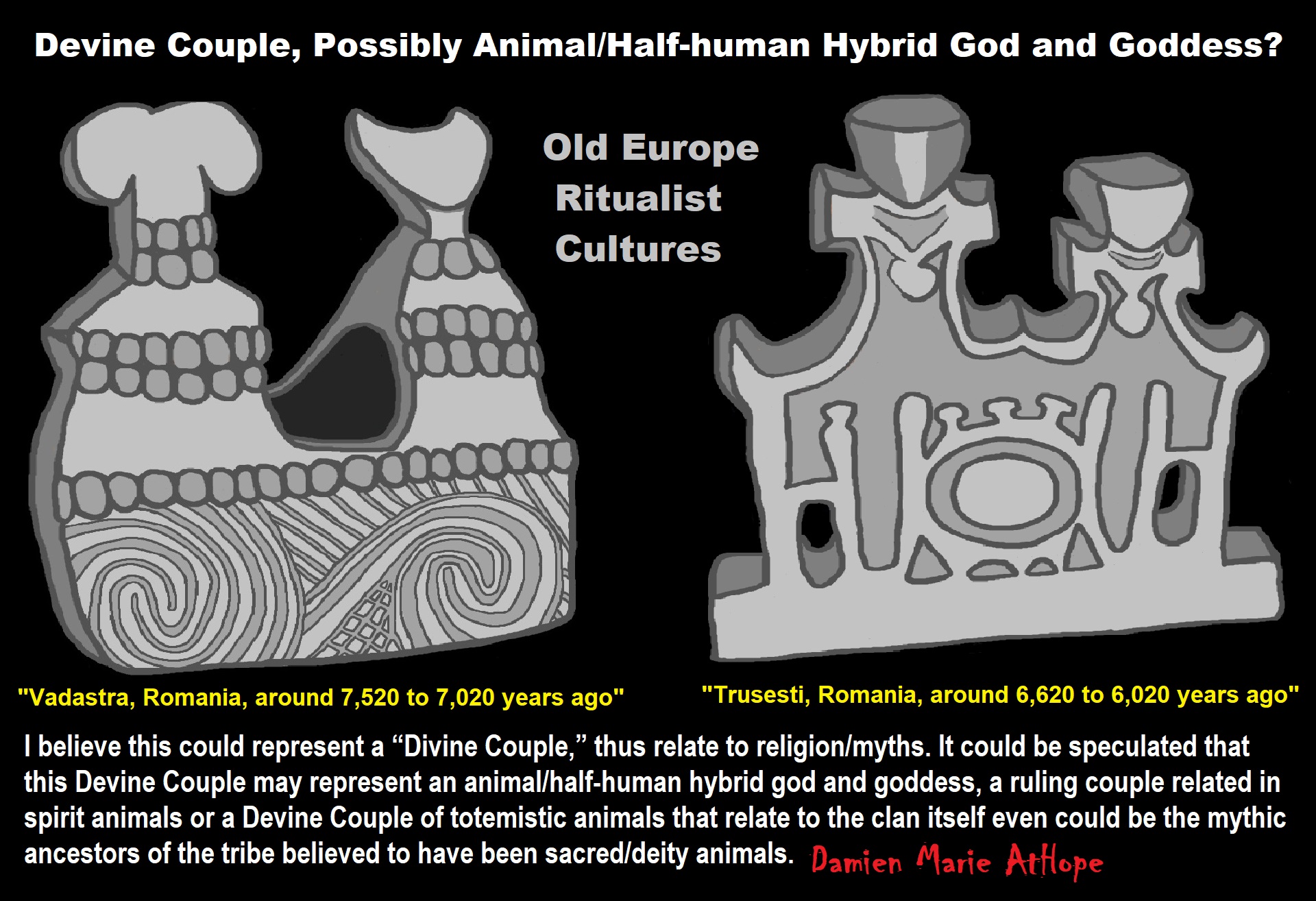

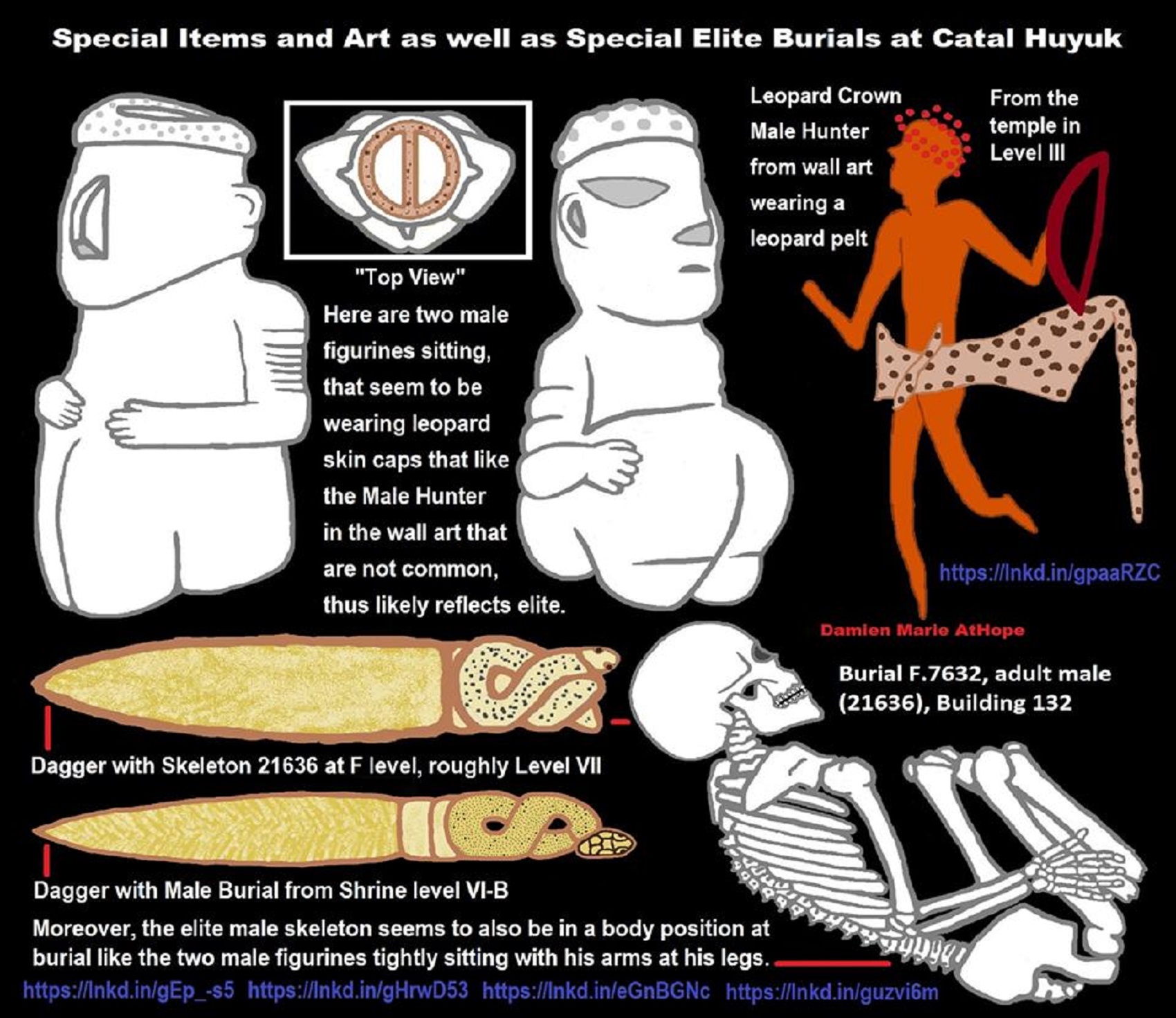

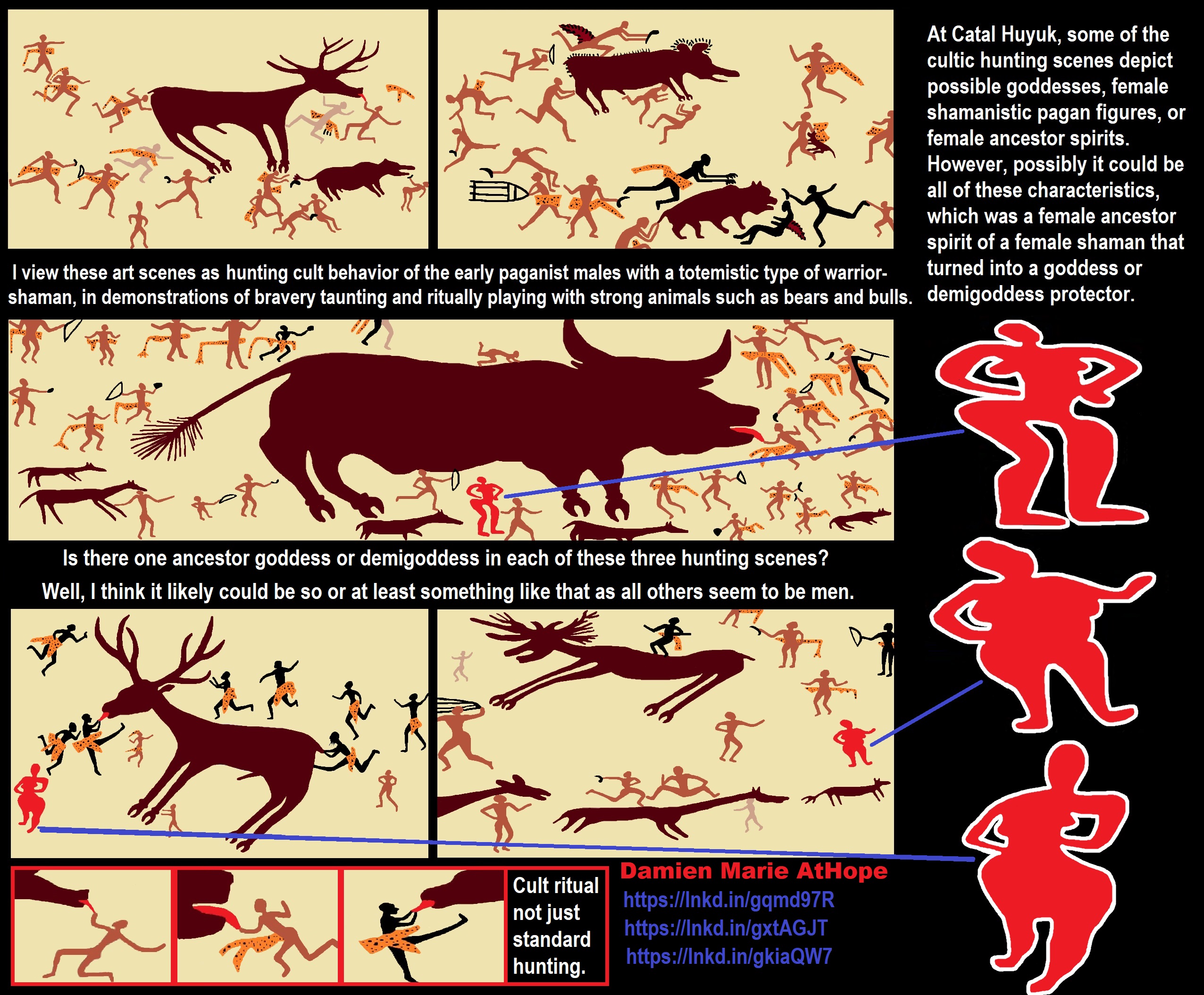

I view these art scenes as hunting cult behavior of the early paganist males with a totemistic type of warrior-shaman, in demonstrations of bravery taunting and ritually playing with strong animals such as bears and bulls. Cult ritual, not just standard hunting. None of the average male hunters are depicted as wearing a leopard skin crown. It is thus a special or elite thing to wear a leopard skin crown and only a few have this. Moreover, I see this not as standard hunting for food but rather cult ritual hunting behaviors. At Catal Huyuk, some of the cultic hunting scenes depict possible goddesses, female shamanistic pagan figures, or female ancestor spirits. However, possibly it could be all of these characteristics, which was a female ancestor spirit of a female shaman that turned into a goddess or demigoddess protector. Is there one ancestor goddess or demigoddess in each of these three hunting scenes? Well, I think it likely could be so or at least something like that as all others seem to be men. ref, ref, ref, ref

To me, my referencing of Catal Huyuk cultic hunting totemistic “warrior-shaman” type it meant to be similar in some ways to the Norse and Germanic peoples paganistic shamanism that involved a sacred trance-like battle-fury closely linked to a particular totem animal, which for Catal Huyuk males was seemingly the leopard (wearer of “leopard -shirts”) and whom I surmise believed they drew their power from the leopard and were devoted to leopard cults. Viking Age “warrior-shamans” had two main totem animal groups, such as the berserkers (wearer of “bear-shirts”) who thought they drew their power from the bear and were devoted to bear cults and ulfheonar (“wolf-hides”) who thought they drew their power from the bear and were devoted to bear cults. Moreover, the wolf type of warrior-shamans appears among the legends of the Indo-Europeans, Turks, Mongols, and even Native American cultures. ref, ref

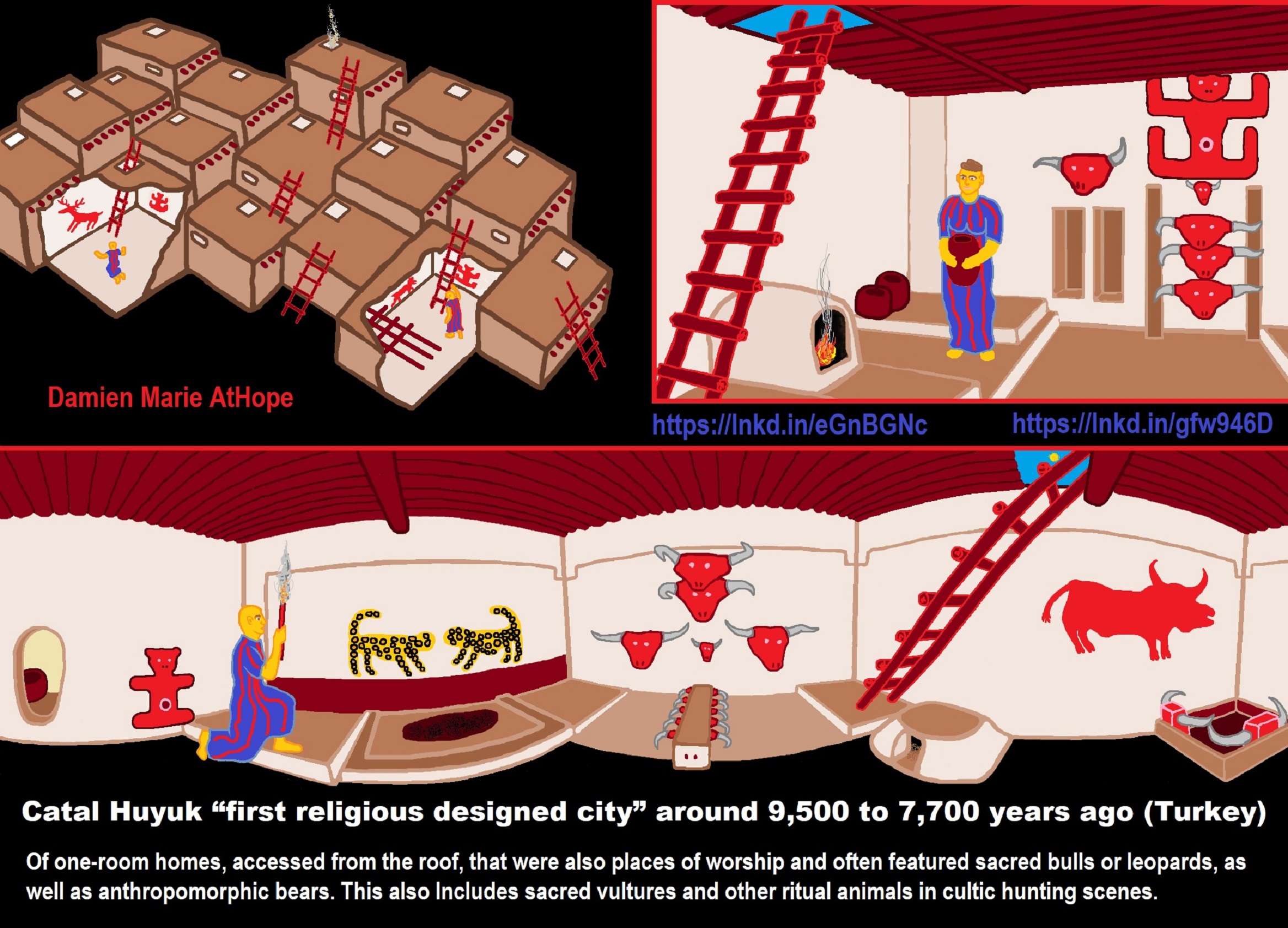

Cultic Hunting at Catal Huyuk “first religious designed city”

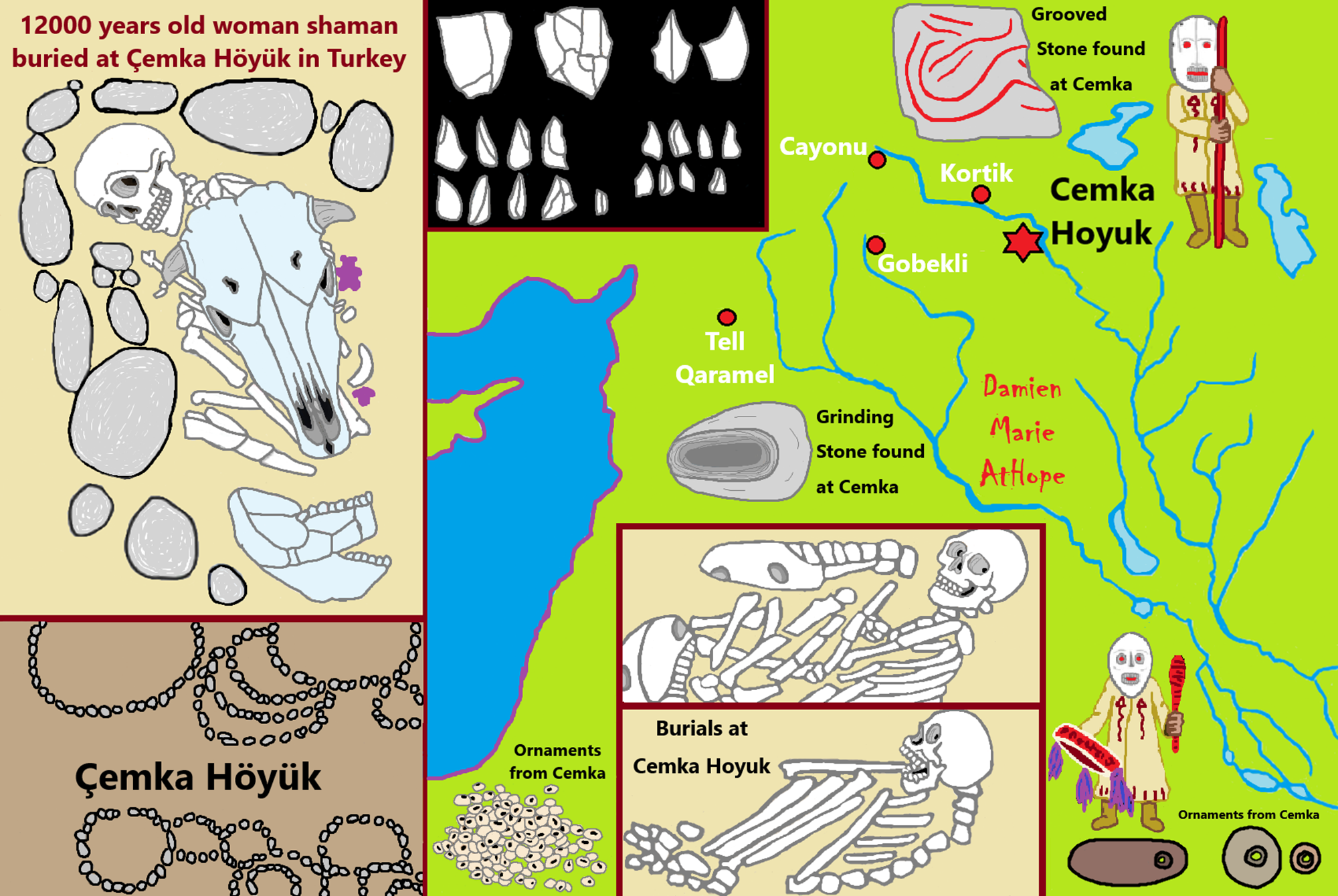

12,000 years ago, a shaman woman was buried at Çemka Höyük in Turkey, similar to others, like the 12,000 shaman woman burial in Israel as well as the phenomenon of Shamanism and the feminine

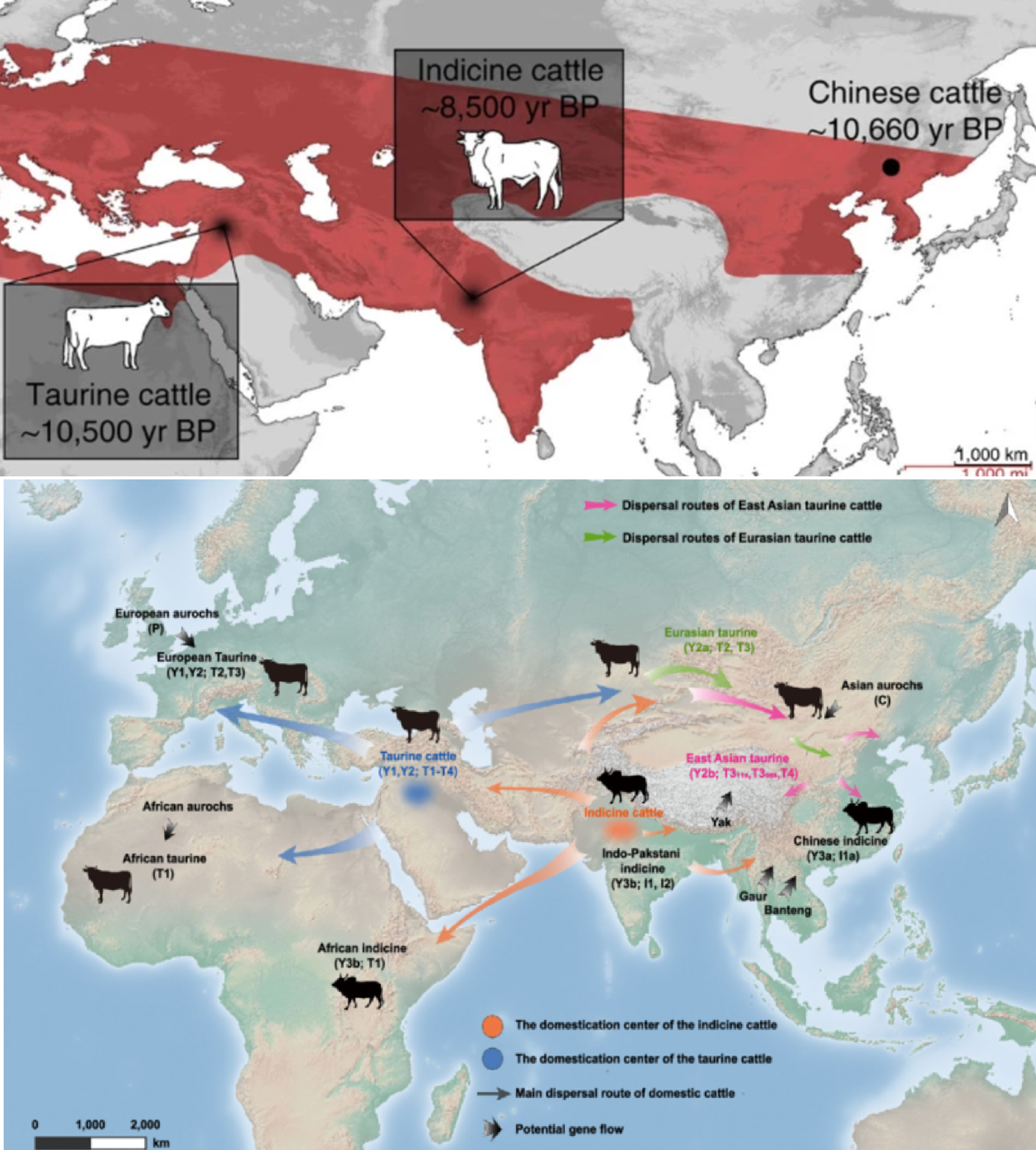

“Approximate migration route and the origin of Africa domestic cattle. Circle regions represent the expected center of cattle domestication. Migration route from outside Africa and within Africa was shown by color arrows, and the color of the arrow represents the migration time and its origin.” ref

Cattle