Indo-European Wheel Words

What exactly is the evidence that Proto-Indo-Europeans had wheels and wagons? And what is the significance of *kwekwlo-?

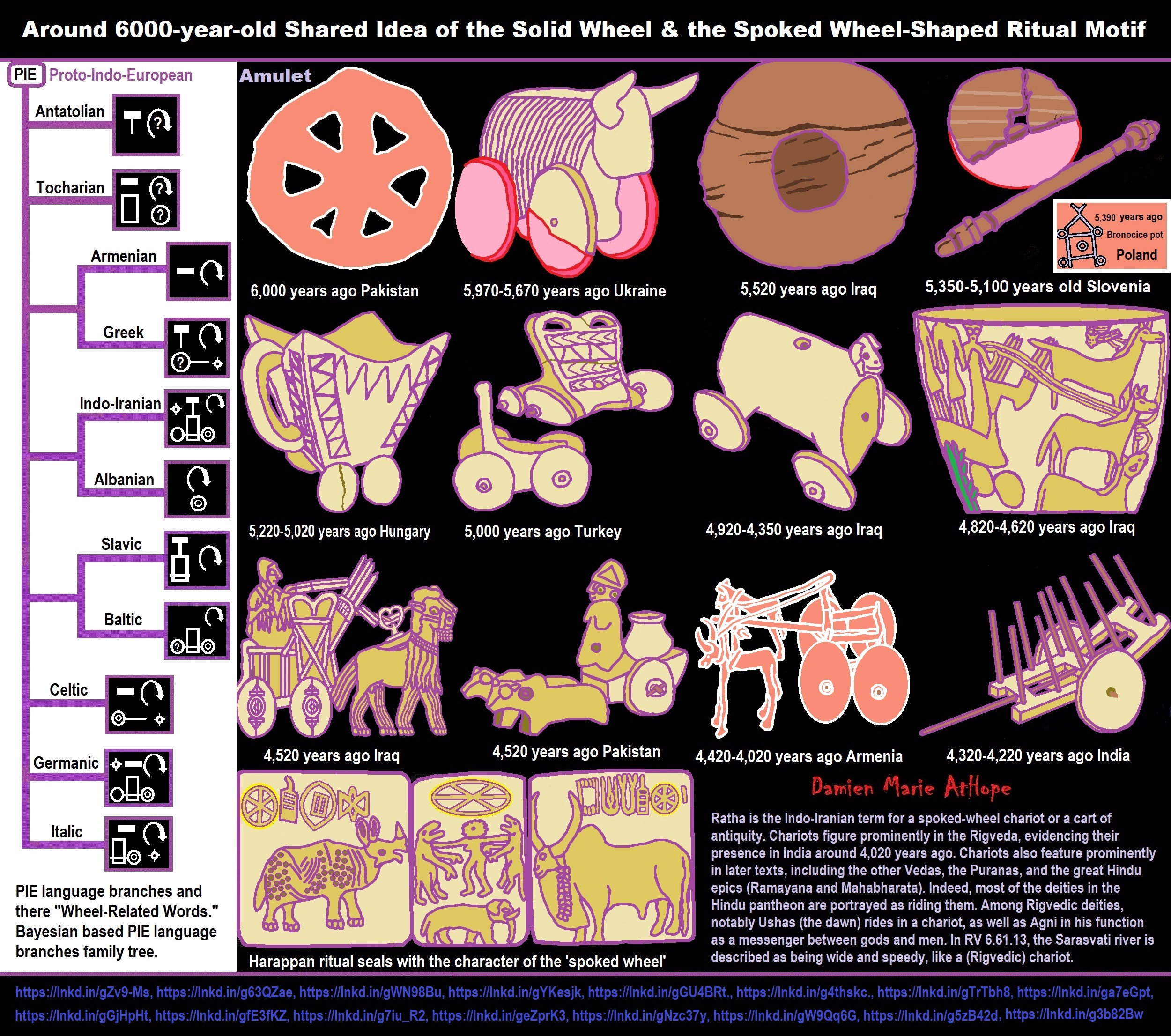

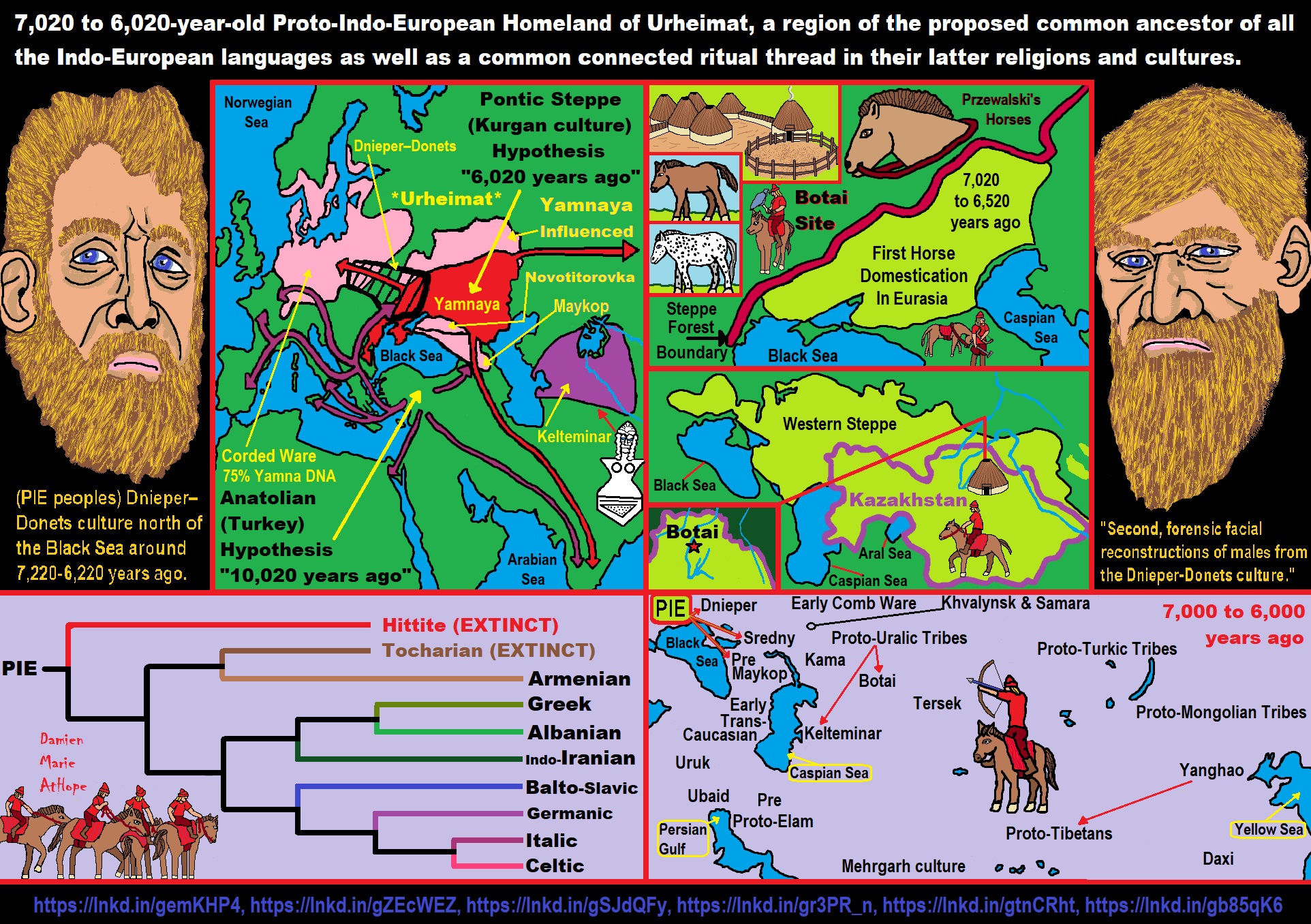

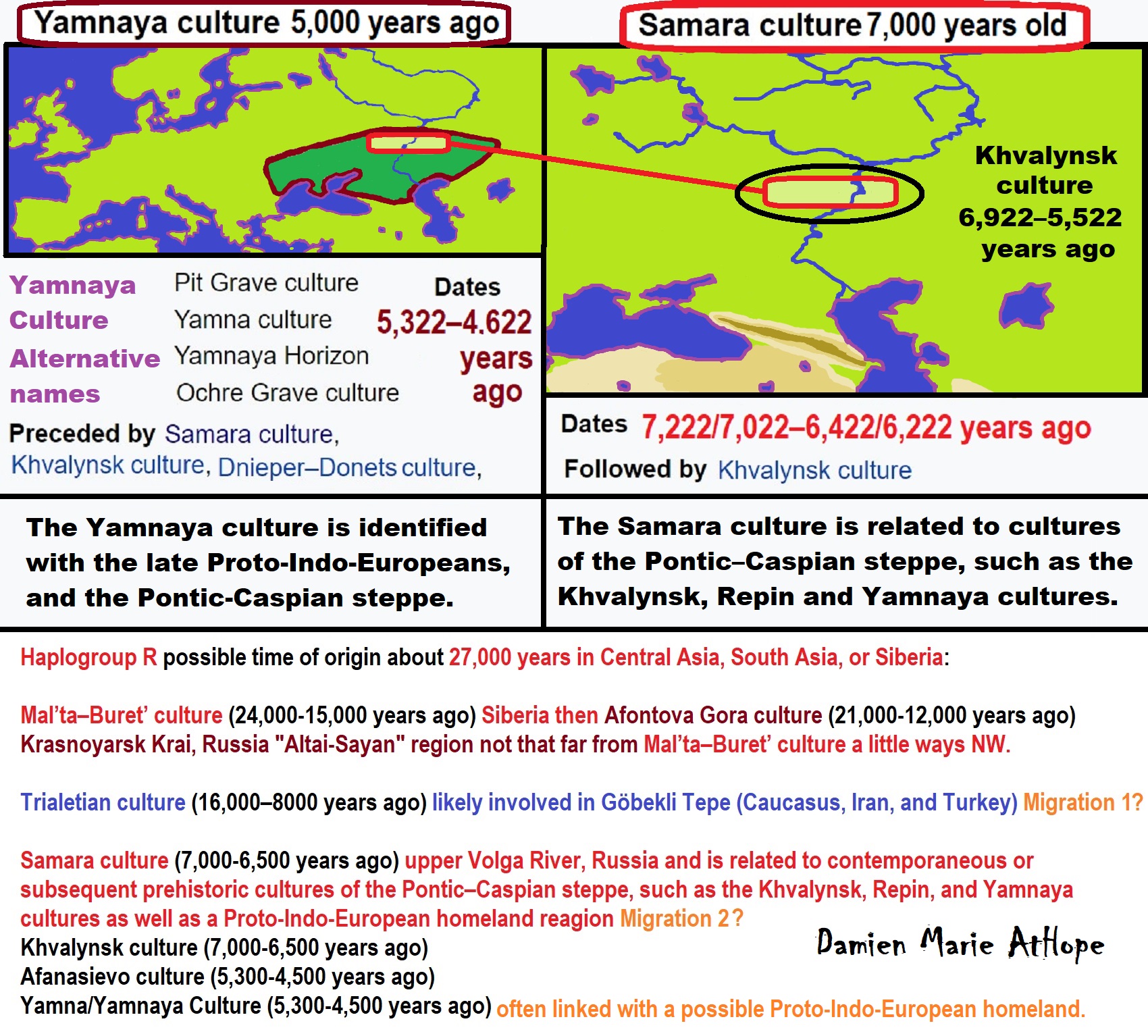

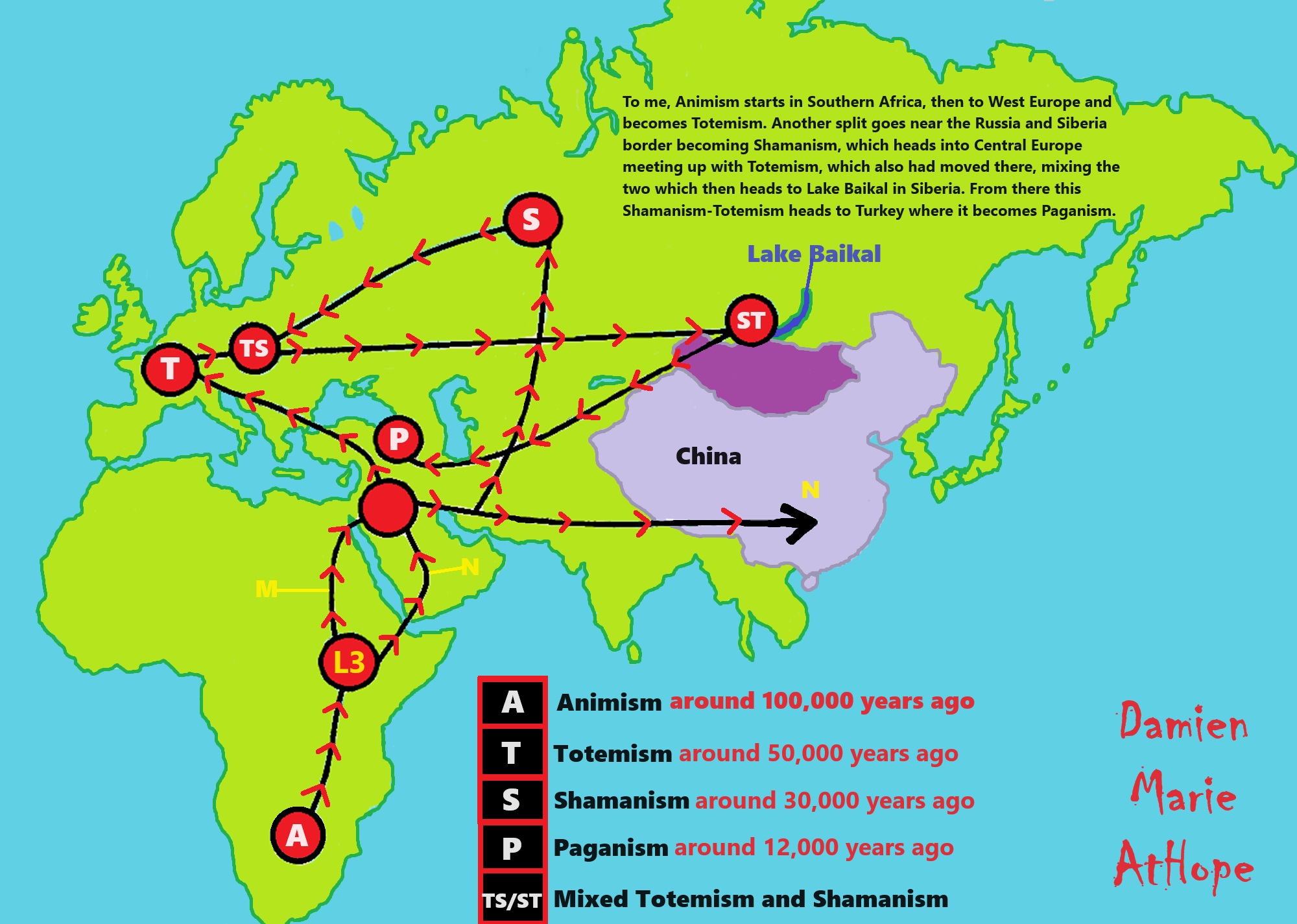

“Wheels, it appears, are not that old. They first turn up, in the form of molded clay wheels on toys, in Ukraine’s Tripolye B2 culture. After this date, there is an explosion of evidence for wheels across Europe and down into the Middle East. So (just going back 500 years to be safe) wheels probably weren’t invented much before, say, 4300 BCE or around 6,320 years ago then. Why does this matter? Frankly, it doesn’t. This is even more true now that the war of arguments over the age of Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is largely won (not in my favor I should add – apart from Anatolian, it probably existed as a mass of dialects somewhere around 4000-3000 BCE or 6,020-5,020 years ago). However, there are still questions to be answered about what has been taken by so many archaeologists and linguists to be a certainty.” ref

“The Halaf culture of 6500–5100 BC is sometimes credited with the earliest depiction of a wheeled vehicle, but this is doubtful as there is no evidence of Halafians using either wheeled vehicles or even pottery wheels. Precursors of wheels, known as “tournettes” or “slow wheels”, were known in the Middle East by the 5th millennium BC. One of the earliest examples was discovered at Tepe Pardis, Iran, and dated to 5200–4700 BC. These were made of stone or clay and secured to the ground with a peg in the center, but required significant effort to turn. True potter’s wheels, which are freely-spinning and have a wheel and axle mechanism, were developed in Mesopotamia (Iraq) by 4200–4000 BC. The oldest surviving example, which was found in Ur (modern day Iraq), dates to approximately 3100 BC. Wheel has been also found in the Indus Valley Civilization, a 4th millennium BCE civilization covering areas of present-day India and Pakistan.” ref

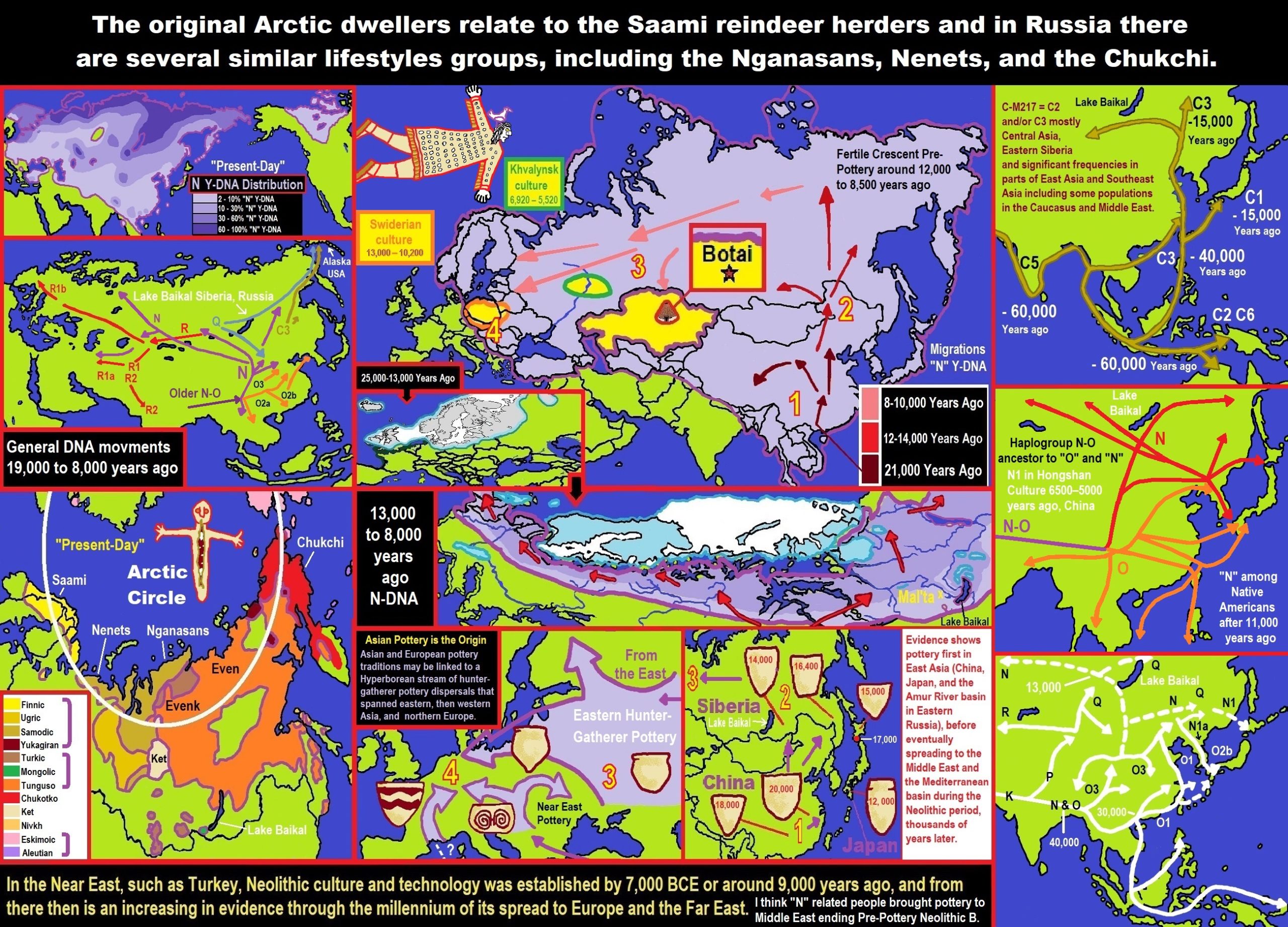

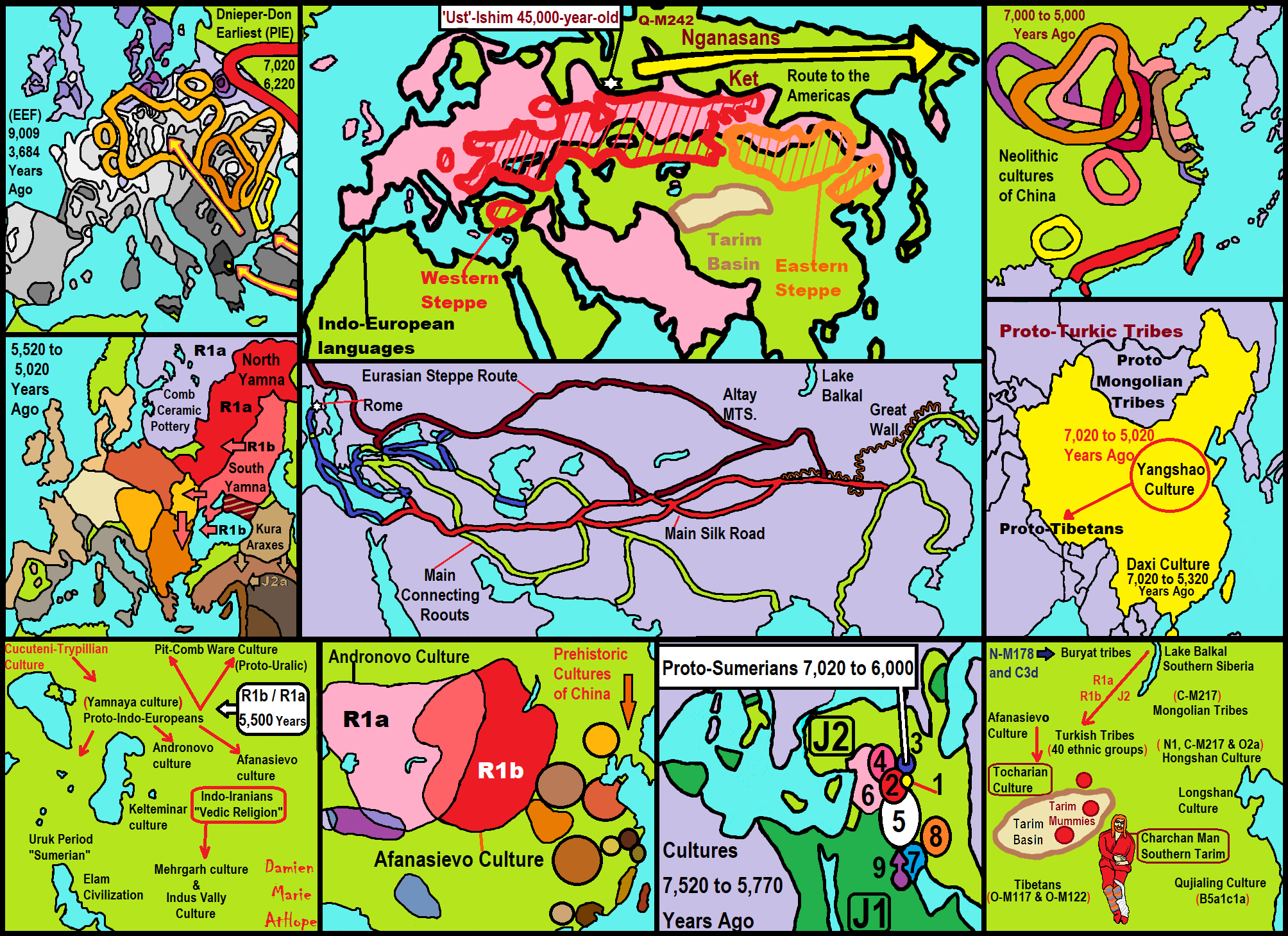

“The oldest indirect evidence of wheeled movement was found in the form of miniature clay wheels north of the Black Sea before 4000 BCE. From the middle of the 4th millennium BCE onward, the evidence is condensed throughout Europe in the form of toy cars, depictions, or ruts. In Mesopotamia, depictions of wheeled wagons found on clay tablet pictographs at the Eanna district of Uruk, in the Sumerian civilization are dated to c. 3500–3350 BCE. In the second half of the 4th millennium BCE, evidence of wheeled vehicles appeared near-simultaneously in the Northern (Maykop culture) and South Caucasus and Eastern Europe (Cucuteni-Trypillian culture). Depictions of a wheeled vehicle appeared between 3631 and 3380 BCE in the Bronocice clay pot excavated in a Funnelbeaker culture settlement in southern Poland. In nearby Olszanica, a 2.2 m wide door was constructed for wagon entry; this barn was 40 m long with 3 doors, dated to 5000 BCE – 7020 years old, and belonged to neolithic Linear Pottery culture. Surviving evidence of a wheel-axle combination, from Stare Gmajne near Ljubljana in Slovenia (Ljubljana Marshes Wooden Wheel), is dated within two standard deviations to 3340–3030 BCE, the axle to 3360–3045 BCE. Two types of early Neolithic European wheel and axle are known; a circumalpine type of wagon construction (the wheel and axle rotate together, as in Ljubljana Marshes Wheel), and that of the Baden culture in Hungary (axle does not rotate). They both are dated to c. 3200–3000 BCE. Some historians believe that there was a diffusion of the wheeled vehicle from the Near East to Europe around the mid-4th millennium BCE.” ref

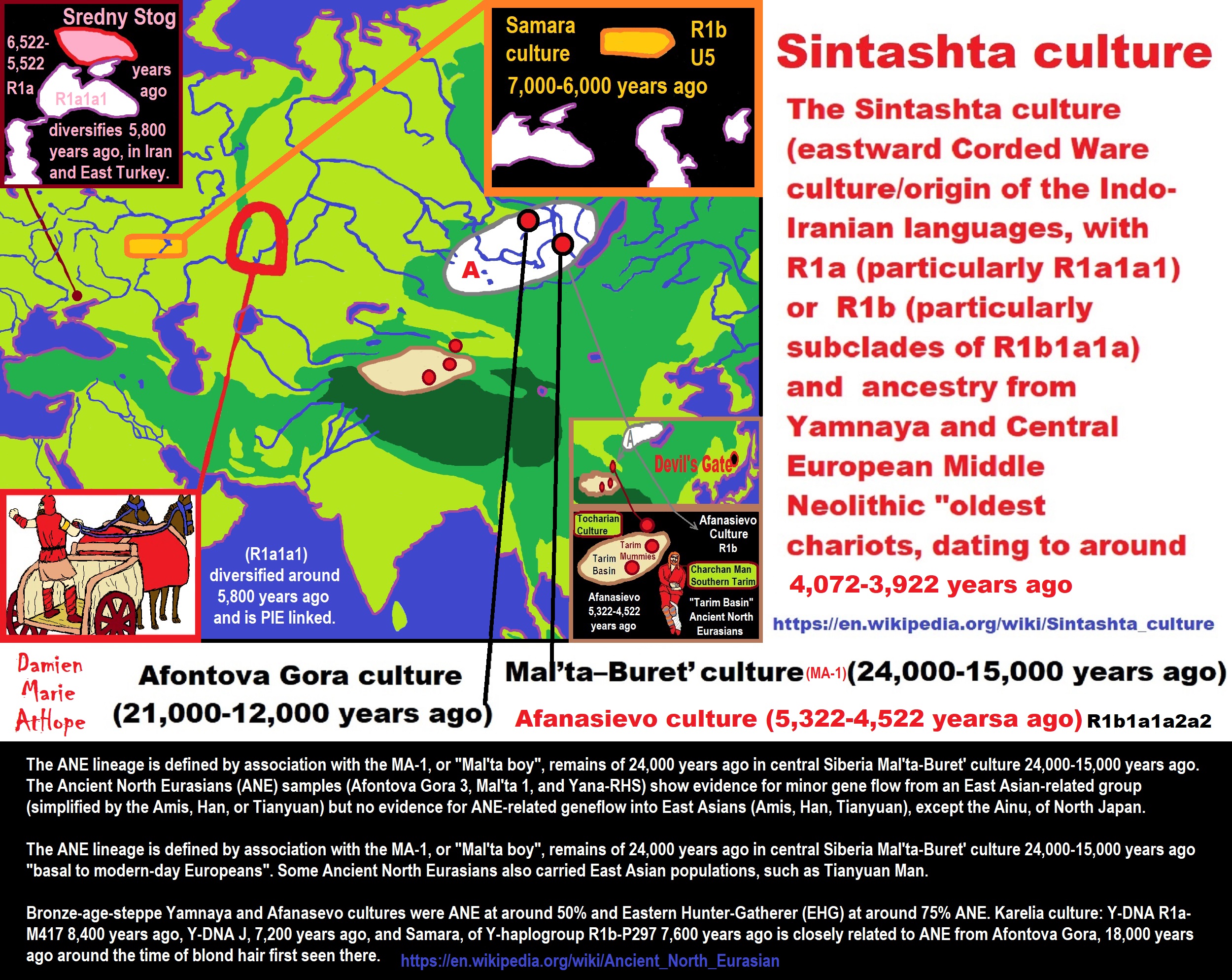

“Early wheels were simple wooden disks with a hole for the axle. Some of the earliest wheels were made from horizontal slices of tree trunks. Because of the uneven structure of wood, a wheel made from a horizontal slice of a tree trunk will tend to be inferior to one made from rounded pieces of longitudinal boards. The spoked wheel was invented more recently and allowed the construction of lighter and swifter vehicles. The earliest known examples of wooden spoked wheels are in the context of the Sintashta culture, dating to c. 2000 BCE (Krivoye Lake). Soon after this, horse cultures of the Caucasus region used horse-drawn spoked-wheel war chariots for the greater part of three centuries. They moved deep into the Greek peninsula where they joined with the existing Mediterranean peoples to give rise, eventually, to classical Greece after the breaking of Minoan dominance and consolidations led by pre-classical Sparta and Athens. Celtic chariots introduced an iron rim around the wheel in the 1st millennium BCE.” ref

“In China, wheel tracks dating to around 2200 BCE have been found at Pingliangtai, a site of the Longshan Culture. Similar tracks were also found at Yanshi, a city of the Erlitou culture, dating to around 1700 BCE. The earliest evidence of spoked wheels in China comes from Qinghai, in the form of two-wheel hubs from a site dated between 2000 and 1500 BCE. In Britain, a large wooden wheel, measuring about 1 m (3.3 ft) in diameter, was uncovered at the Must Farm site in East Anglia in 2016. The specimen, dating from 1,100 to 800 BCE, represents the most complete and earliest of its type found in Britain. The wheel’s hub is also present. A horse’s spine found nearby suggests the wheel may have been part of a horse-drawn cart. The wheel was found in a settlement built on stilts over wetland, indicating that the settlement had some sort of link to dry land.” ref

“The wheel has also become a strong cultural and spiritual metaphor for a cycle or regular repetition (see chakra, reincarnation, Yin and Yang among others). As such and because of the difficult terrain, wheeled vehicles were forbidden in old Tibet. The wheel in ancient China is seen as a symbol of health and strength and utilized by some villages as a tool to predict future health and success. The diameter of the wheel is an indicator of one’s future health. The winged wheel is a symbol of progress, seen in many contexts including the coat of arms of Panama, the logo of the Ohio State Highway Patrol, and the State Railway of Thailand. The wheel is also the prominent figure on the flag of India. The wheel in this case represents law (dharma). It also appears in the flag of the Romani people, hinting to their nomadic history and their Indian origins. The introduction of spoked (chariot) wheels in the Middle Bronze Age appears to have carried somewhat of a prestige. The sun cross appears to have a significance in Bronze Age religion, replacing the earlier concept of a Solar barge with the more ‘modern’ and technologically advanced solar chariot. The wheel was also a solar symbol for the Ancient Egyptians.” ref

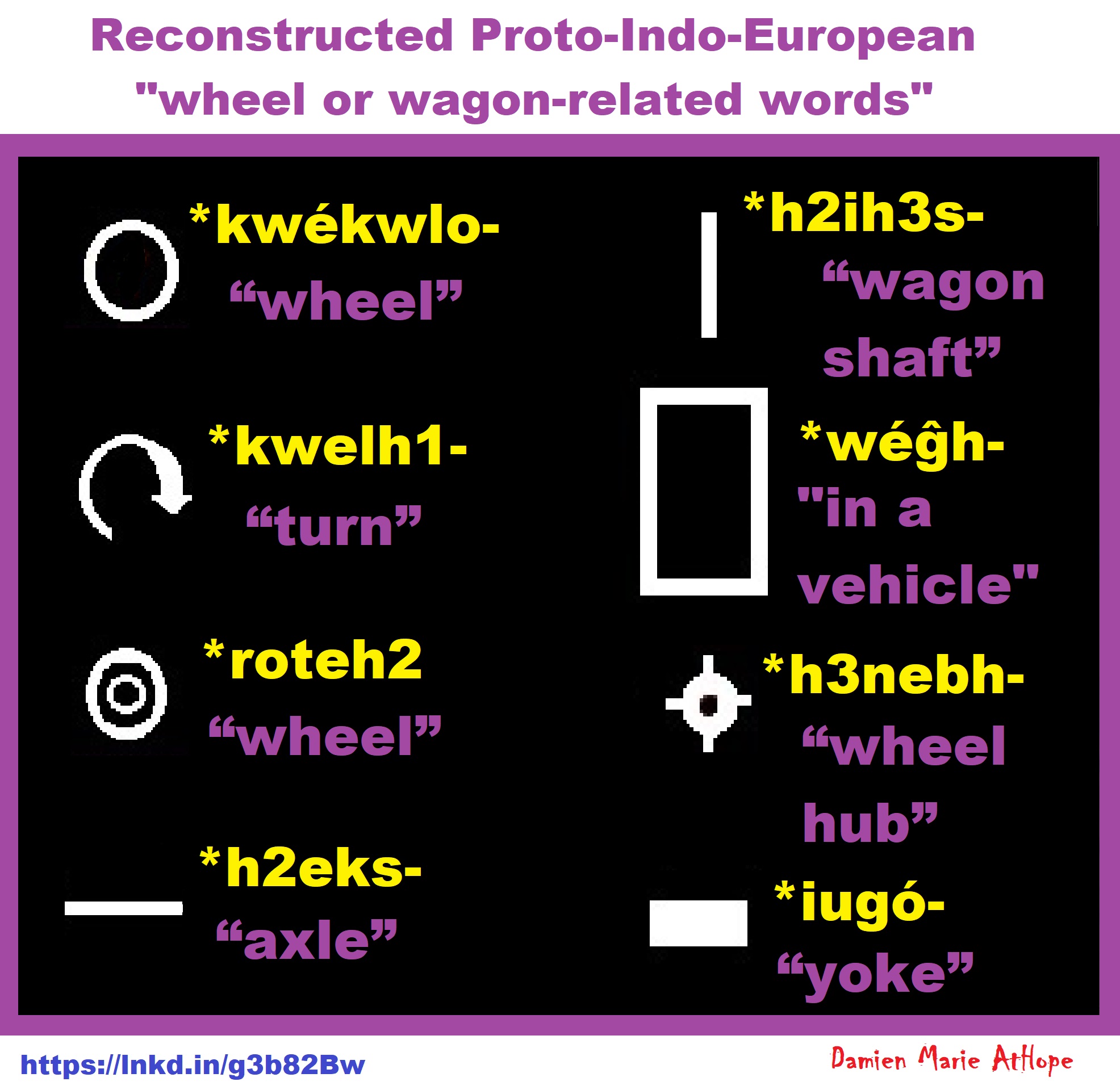

The “wheel” related word list

“Most linguists argue that the PIEs (Proto-Indo-Europeans) did have words for wheel. The candidates put forward for wheel or wagon-related words are nine reconstructed PIE word forms. These are:

- *hurki , argued to mean “wheel”

- *roteh2, argued to mean “wheel”

- *kwékwlo-, argued to mean “wheel”

- *kwelh1-, argued to mean “turn” perhaps in the sense of a turning wheel.

- *h2eks-, argued to mean “axle”

- *h2ih3s-, argued to mean “thill” or “wagon shaft”

- *wéĝh-, argued to mean “convey in a vehicle”

- *h3nebh-, argued to mean “nave” or “wheel hub”

- *iugó-, argued to mean “yoke” ref

The end of the Proto-Indo-European?

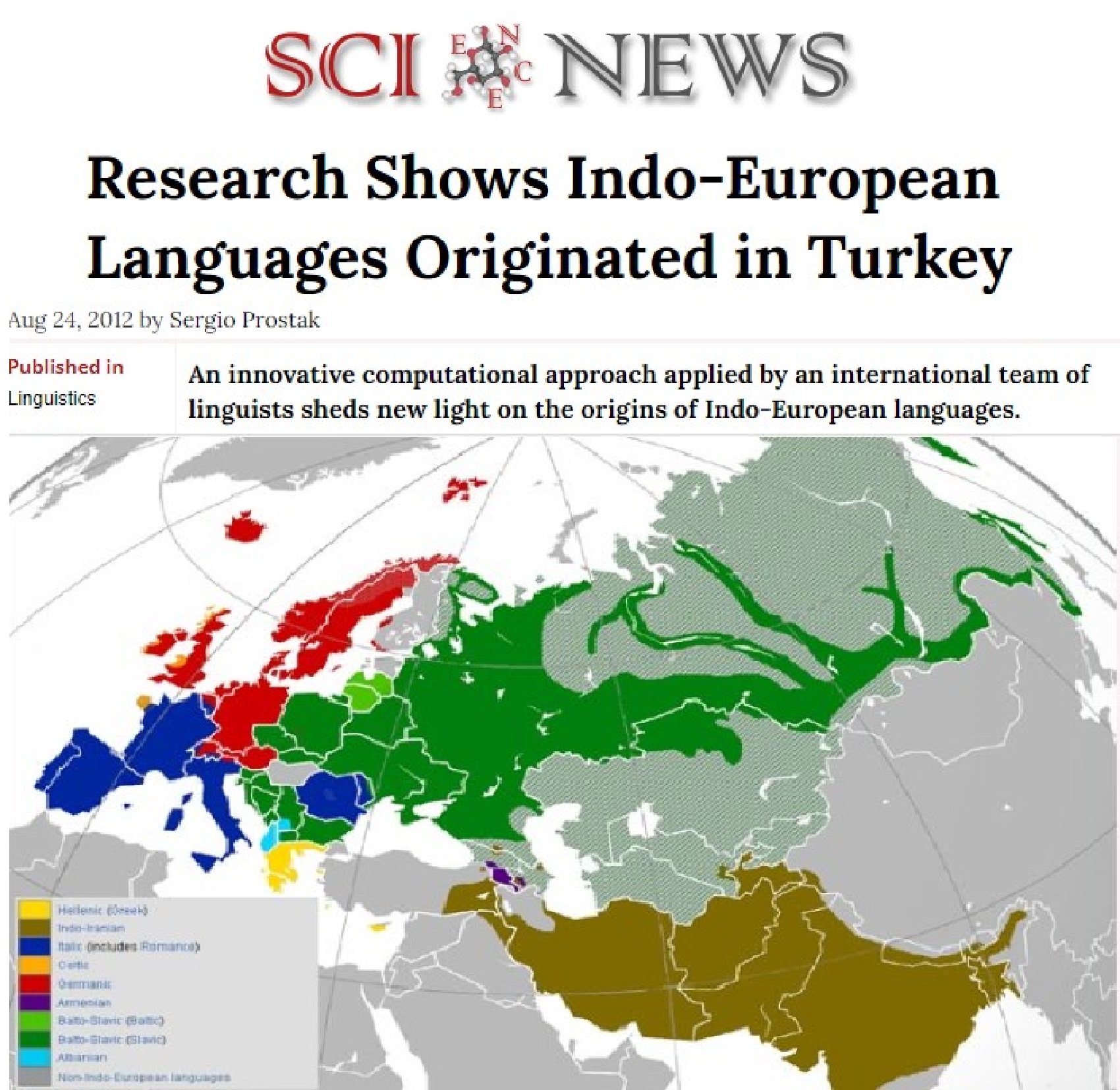

“It should mention the IE Indo-European branches which are important to this discussion. Currently, it’s generally accepted by all sides that the Anatolian language branch was the earliest to become separated from the rest of the PIE Proto-Indo-European group. This branch, which included Hittite, is now extinct but it was once present across much of modern-day Turkey. Because the Anatolian languages are quite different from other IE languages they are sometimes excluded from PIE. Instead, an earlier grouping is defined, called Proto-Indo-Hittite. Although there is some discussion, the next language branch generally thought to have split from the main IE group is the Tocharian branch. This is also extinct, but was present in the Taklamakan desert, north of the Himalayas. After that no-one can really agree which language branch or branches were the next to separate off. Candidates include Celtic, Celto-Italic, Germanic, Greek-Armenian, Greek-Armenian-Indo-Iranian, Albanian, etc.” ref

*kwelh1-, “to turn”

“This root is reconstructed regularly from Latin colus, meaning “spun thread”, Old Indic cárati, Old Irish cul meaning “vehicle”, Old Norse hvel, meaning “wheel”, Old Prussian kelan, meaning “mill wheel”, Ukrainian коло (kolo), meaning “circle” (corrected 19/6/11), Bulgarian кола (cola), meaning “cart” and Greek πολος (polos), meaning “axis”, and Albanian sjell, meaning “to turn”, and Armenian shrjvel, meaning “turn around”. The form seems to have resulted in a variety of different words. Many, but not all, relate to wheels and transport. These words can be divided into two categories. Those such as hvel, kelan, cárati and sjell are all regularly derived from the PIE root with e-grade (it’s got the vowel ‘e’ in it) *kwelh1-. Those such as colus, cul, коло and polos are regularly derived seemingly from the PIE with o-grade *kwolh1-. Whilst this is a regular phenomenon it does, arguably, suggest subtly separate origins for the derivations between, say, Old Norse and Russian. Interestingly, Luwian and Hittite include the word kaluti, which seems to mean “a turn” or “a circle”. However, linguists seem to think it is not derived from the same root (presumably because it would have become something like kual-). Tocharian A lutk & B klutk, meaning “to turn”, may be also from *kwelh1– but are irregular if so.” ref

*roteh2-, “wheel” (n)

“This is reconstructed regularly from Latin rota, Irish rath, Welsh rhōd, Lithuanian rãtas, Latvian rats and German rad (amongst others), all of them meaning “wheel” in the sense of a wagon, as well as Albanian rreth, meaning “circle”, and Old Indic rátha, meaning “chariot”. The etymology is pretty clear and unambiguous and it would be difficult to put forward an argument that the speakers of the root language of all of these did not have wheeled vehicles of some kind. It seems implausible that Tocharian A ratäk & B retke, meaning “army”, is derived from *roteh2 as tentatively suggested by Douglas Q Adams (PIE *roteh2– should become Tocharian *racä- as far as I can tell). Generally, it’s thought to be a Proto-Iranian loanword from *rataka, thought to mean “order” or “series”, although this itself has problems.” ref

*ak’s– or *h2eks-, “axle” (n)

“This root is reconstructed regularly from Old Indian ákṣa-, Latin axis, Irish ais, Welsh echel, German achse, Lithuanian ašìs, Russian ось (osi) and Old Greek άξονας (axonas) (among other languages). All mean either “wheel axle” or “axis on which something turns”. Therefore some relationship with a wheel seems reasonable.” ref

*h2ih3s-, “thill” or “shaft” (n)

“This is reconstructed from Old Indic īṣá, Hittite hissa, and Russian vojë (among other languages) meaning “shaft”, as well as Old Greek óiαξ (óiaks), meaning “tiller”, and English oar. I admit to finding this PIE stem’s derivation tricky to follow. Regardless, its necessary connection with a wheeled wagon seems tenuous.” ref

*wéĝh-, “convey in a vehicle” (v)

“This root is reconstructed regularly from German weg, English weigh, Latin vehō, Bulgarian веза (vesа) and Lithuanian vèžti . Meanings are generally on the lines of “carry” or “convey”, sometimes by means of a wagon. In Old Indic its cognate occurs in váhati, meaning “transport”. It’s also recognised in Tocharian A wkäṃ and B yakne, meaning “habit” or “manner”. Words meaning “wagon” have been derived from many of these words. However, there is nothing to indicate that the original PIE root particularly signified carrying something in any form of wheeled transport. In the case of Tocharian the link with wheeled transport, or in fact, any form of transport, is non-existent.” ref

*h1wŗgis, “wheel” or “having circular form” (n)

“This is based on the zero-grade (i.e. missing the vowel, meaning that the r has to pretend to be a vowel) of the PIE root *h1werg-. It is thought to mean “to turn around”. This is argued to have descendants in both Hittite hurki, and Tocharian A yerkwanto and B wärkänt, all of which mean “wheel”. However, to quote David Anthony, “Tocharian specialist Don Ringe sees serious difficulties in deriving either Tocharian term from the same root that yielded Anatolian hurki-, suggesting that the Tocharian and Anatolian terms were unrelated and therefore do not require a Proto-Indo-European root.” ref

*h3nebh-, “nave” or “hub” (n)

“This is reconstructed from Old Indic nábhya, meaning “wheel hub”, and many other languages including Greek omphalós, Latin umbilīcus, Old Irish imbliu, English navel, where it always means “navel”. Although it has come to mean “hub” in Old Indic, trying to assign any other meaning to the root but “navel” seems unreasonable.” ref

*iugó-, “yoke” (v)

“This is reconstructed from Old Indic yoga, Greek zdügo, Latin iugum, Welsh iau, English yoke, Russian иго (igo), all meaning “a yoke” or “yoking”. Other words thought to be related are Tocharian A & B yuk, meaning “conquer” and Hittite juga-, of unknown meaning, but possibly “yoke”. This word appears to have meant “yoke” as in to tie animals to something such as a plough or wagon.” ref

*kwékwlo-, “wheel” (n)

“This was originally reconstructed from Old Indic cakrá, meaning “circle” or “wheel”, Avestan caxrem, meaning “wheel” and Old English hweogol, hweowul, or hwēol, meaning “wheel” or “circular band”. Words also thought to derive from this root are Greek kuklos meaning “circle” or “wheel”, Tocharian A kukäl and B kokale, meaning “wagon”, and Lithuanian kãklas, meaning “neck”. Hittite kugullas could also derive easily from *kwékwlo-. However, its meaning, something along the lines of “lump” or “measure” or even “bread roll”, although unclear, is unlikely to be related to wheels. The reconstructed form *kwékwlo- appears to derive from the PIE root *kwélh1– (seen above) meaning something along the lines of “to turn”, by a process known as reduplication. Reduplication in IE is where a verb, noun, or adjective is expanded, often to give emphasis. This might have produced a shape like *kwékwelh1– or *kwékwolh1– which, by dropping the laryngeal h1 and adding a noun ending such as the animate non-neuter or masculine -os (all regular changes) would give *kwékwlos, meaning something like “revolver”, hence “wheel”.” ref

“The chance of reduplicating a root then turning it into a noun is reasonably high and may have been done many times in history. However, if it had been done by one of the descendants of IE it should have produced a distinctly different form, recognisable to an IE linguist. Indeed, in the opinion of one such linguist, Andrew Garrett, “… such an account is hardly possible for PNIE [Proto-Nuclear-Indo-European] *kwékwlos ‘wheel’ (in Germanic, Greek, Indo-Iranian, Tocharian…): though derived from *kwélh1– ‘turn’, a reduplicated C1e-C1C2-o- noun is so unusual morphologically that parallel independent formation is excluded.” This makes *kwékwlos the flagship word for the wheelies. It would suggest that any IE language that includes a word derived by regular rules of IE sound change from *kwékwlo- must have been part of a larger grouping somewhere in the second half of the fifth millennium BC or later. Following this argument, as both Tocharian and Greek have words supposedly derived from *kwékwlo- they must have split from the main IE group after wheels were invented. However, I seem to see weak points with this argument. Therefore it’s perhaps worth looking at the individual-derived words in more detail.” ref

Old Indic cakra, meaning “wheel’

“This, word, closely related to Avestan čaxra, meaning “circle” or “wheel”, can be derived by regular means from a PIE form *kwékwlo- via Proto-Indo-Iranian *kekro-. It is notably comparable to some Finno-Ugric words, such as Finnish kekri, which have meanings varying from perhaps “yearly cycle” to “circular”. Although this raises the possibility that the Indo-Iranian word is derived from a Finno-Ugric language, this is unlikely. Few, perhaps no, words have gone into Indo-Iranian from Finno-Ugric.” ref

English wheel, meaning “wheel”

“This is thought to come from Old English hweogul, hweowul or hwēol. PIE *kwekwlo- would develop into a form like *hwigwl. With the softening of gw to give *hwiwl this seems close enough to be reasonable. (If you want a much fuller understanding of this, the linguist Piotr Gąsiorowski has a post on it here.)” ref

Ancient Greek kuklos, meaning “circle” or “wheel”

“Χύχlος (kuklos), with an irregular plural χύχlα (kúkla), meaning “set of wheels” (NB the ancient Greek for “wheel” is τροχός trochos) is suggested to derive from a Proto-Greek form *kwukwlos, although without explanation for the change of vowel from PIE *kwékwlos. Postulating the Proto-Greek form *kwukwlos is an attempt by linguists to explain why the recorded ancient Greek form was not *téklos or *péklos, as would be expected from the normal sound change laws. For comparison, ancient Greek τέσσαρες/πέσσαρες (téssares or péttares, depending on dialect), both meaning “four”, are thought to be from PIE *kwetwares. This makes the derivation of kuklos from *kwekwlos strange. Sihler has suggested that “strongly labial environments” (i.e. using your lips to make a sound) may change a PIE “e” to PIE “o” (a result of ablaut), which would naturally change to “u” in Proto-Greek. One of two good examples of this that Sihler quotes is, of course, *kwékwlo-, the other being PIE *gwenh2-, which becomes Greek γυνή (guní) instead of, say, *bení or *dení. So Sihler’s preferred late PIE form is *kwokwlos. A third possible example of this rule given by Sihler is *swépnos becoming ϋπνος. However, Sihler himself expressed doubts about this, as it could simply be the natural change of zero-grade PIE *súpnos.” ref

“Much of Sihler’s argument depends on what you mean by a “strongly labial environment”. If this simply means that it has a labiovelar (e.g. kw or gw) in front of it, then it makes it difficult to explain why PIE *kwélh1- has derived words such as πόλος (pólos), πέλομαι (pélomai) and πέλω (pélō). If, on the other hand, “strongly labial” means that the vowel has two labiovelars or labials on either side then this rules out the use of such a rule for *gwenh2– to guní. Not much of a rule. Much more complex, but in a way clearer, is Piotr Gąsiorowski’s argument that kúklos is derived from the collective of *kwékwlos. Collectives are thought to be a type of PIE noun to indicate a set or grouping of something, in this case a “set of wheels” say. It is thought that when a collective form of a noun was created in PIE it had a different ending, *-eh2 instead of *-os (this is a regular process). The new form *kwékwleh2 , again by regular development of *-eh2 to *-a, and moving the stress to the end, would become *kwekwlá. From there, the first vowel might be weakened to make *kwɔkwlá and the first consonant delabialised, allowing it to become *kuklá in Greek.” ref

“(It should also be mention that Gąsiorowski’s argument has greater implications, as formation of the collective is something that appears to have happened only in early PIE, not late, and at a time when the Anatolian family was still close or had not yet branched off.) In for following his argument up to here but now Prof Gąsiorowski talks about regularisation of the accent to match the singular to make it kúkla. If that is regularisation with kúklos (which also exists) then that appears to mean that nominative singular kúklos and plural kúkloi were themselves changed from *péklos/i or *téklos/i to match *kuklá, which doesn’t seem to make sense. I’ve asked him about this and he resorted to Sihler’s argument about “strong labial environments”. Hmm. Does that mean that the collective argument is not needed?” ref

Lithuanian kãklas, meaning “neck”

“This word can be from PIE *kwekwlo- via Balto-Slavic *k:ikla-. However, it would again be preferable to derive kãklas from *kwokwlo-, as with Greek. If the form originally meant “wheel” it has changed this meaning considerably. This could possibly be achieved with a corruption of meaning to do with, say, wheeling your head around, although this seems a stretch (in both senses of the word).” ref

Tocharian kukäl (A) & kokale (B), meaning “chariot” or “wagon”

“(NB The Tocharian for “wheel” is, as stated above, A wärkänt, B yerkwanta) Kukäl and kokale are thought to derive from a Proto-Tocharian form, perhaps *kukäle. As with Greek there are problems deriving this form from PIE *kwekwlo-. The form necessary for giving the correct Tocharian should be, as Tocharian expert Douglas Adams noted, “closely related to, but phonologically distinct from … *kwekwlo- .” He suggests PIE *kwukwlo-. Alternatively, Don Ringe (2009) suggests the following, slightly tortuous derivation process (references removed): “*kwékwlos > *kwékwlë > *kwyékwlë > *kwyә́kwlë → Proto-Tocharian *kwә́kwlë ‘chariot, wagon’ (with adjustment of palatalization in a reduplicated form; or is this just straightforward assimilation?); > *kŭkl ~ *kŭkla- > *kukäl ~ kukla- → Tocharian A kukäl ~ kukla-; > *kwәkwә́lë > Tocharian B kokale.)” ref

“This looks a bit like the Greek derivation of Piotr Gąsiorowski. The reason for this complication is because PIE *kwékwlo- would give a Tocharian form of *käkla- or, following the sound change laws to their extremes, *käśla- or *śäśla- or *śla- (c.f. PIE *kwetares becomes Proto-Tocharian *ś(ä)twer, becoming Tocharian A śtwar and B śtwer). Looking at it another way, *kukäle could be derived from PIE *kwukwelo-, *gwugwelo-, *kukelo- or some other similar forms, but not obviously from *kwekwlo-. On the other hand, the –käl– element of both kukäl and kokale could simply be derived from PIE *kwelh1– (the root thought to mean “turn” mentioned earlier) without any reduplication. There are also other PIE roots that could give rise to the same element. For example PIE *kwele-, meaning to “move around” or “drive”, is thought to have produced the Tocharian stem käl-, to “lead” or “bring”. This would satisfy the Tocharian form in kukäl and kokale. Speculating wildly and unsensibly, the first element of kukäl and kokale could, conceivably, be related to the Tocharian word for “cow”, which is ko in Tocharian A and keǔ in Toch B (probably from another PIE root *gwow- through Proto-Tocharian *kew). Using this logic the words for “lead” and “cow” could be brought together in the Proto-Tocharian word *kukäle, meaning “cow bring thing”… Well, perhaps not.” ref

The significance of *kwekwlo-

“Looking at the words supposedly derived from *kwekwlo- it seems that all apart from cakrá and caxrem and hwēol require some manipulation of the PIE form. There is at least the need for a second, o-grade form, *kwokwlo- and possibly a zero-grade-ish third (say *kwukwelo-). At the moment I can’t help having doubts about whether such a word as *kwekwlo-, meaning “wheel”, ever existed in the original PIE vocabulary. Its descendants, unlike those of *roteh2, are rather scarce among the different branches. More preferable is that different reduplicated forms occurred, with different meanings perhaps related to turning, at different times. So, to contradict Andrew Garrett, parallel independent formation from derivatives of *kwelh1– or *kwolh1– seems just as easy as anything.” ref

Discussion – who did have wheels?

“Certain forms, such as *roteh2 and *h 2eks-, appear to mean “wheel” and “axle” respectively. They seem to reflect a genuine, wheel-related origin and one or both appear in all the language families excluding Tocharian and Anatolian. As for *kwelh1 and *kwekwlos they may well be connected to an original word for wheel and they may not. If they were, then Greek would be part of the wheel set. It gets complicated if the Hittite word kugullas is added as part of the group, as it actually makes a worse case for these words being connected to wheels and a better case for them being connected to round and rollable things in general. Some words, such as *h2ih3s-,*wéĝh-,*iugó- and *h3nebh-, have meanings which do not necessarily require the use of wheels or wagons. Therefore their distribution in the language groups is not enough evidence for the use of wheels by PIEs. *hurki can be also excluded from the discussion as this form may well not have existed.” ref

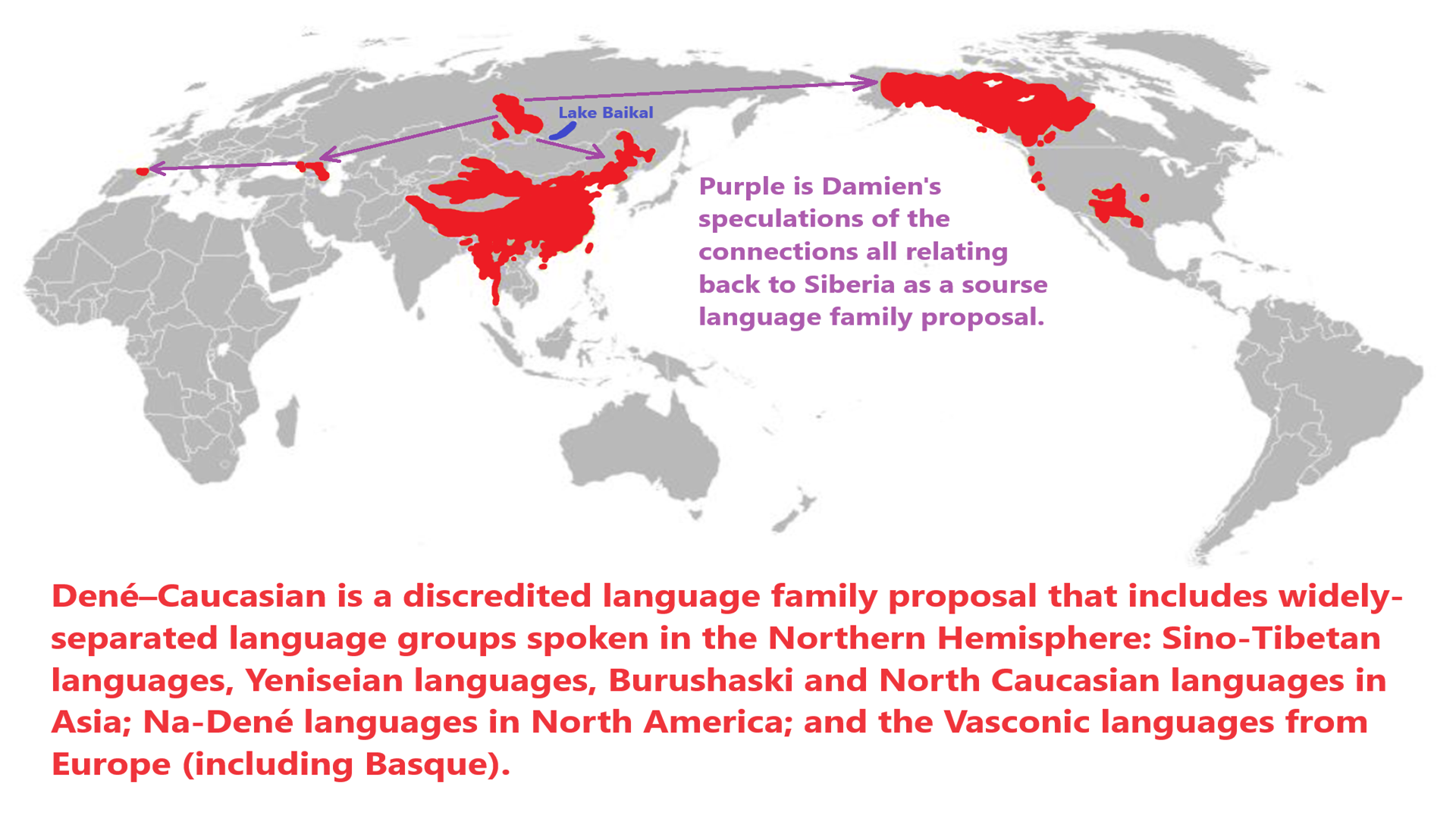

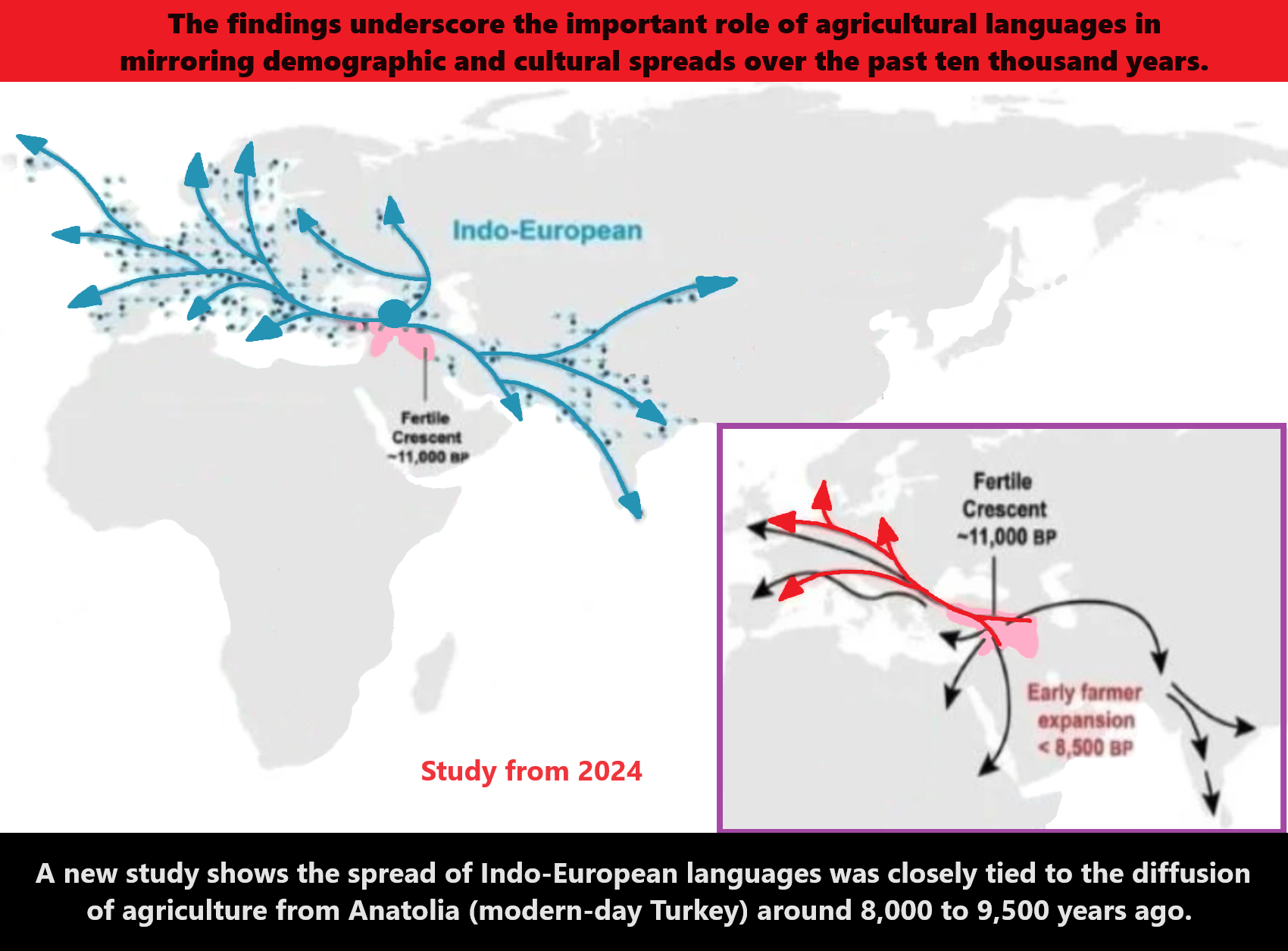

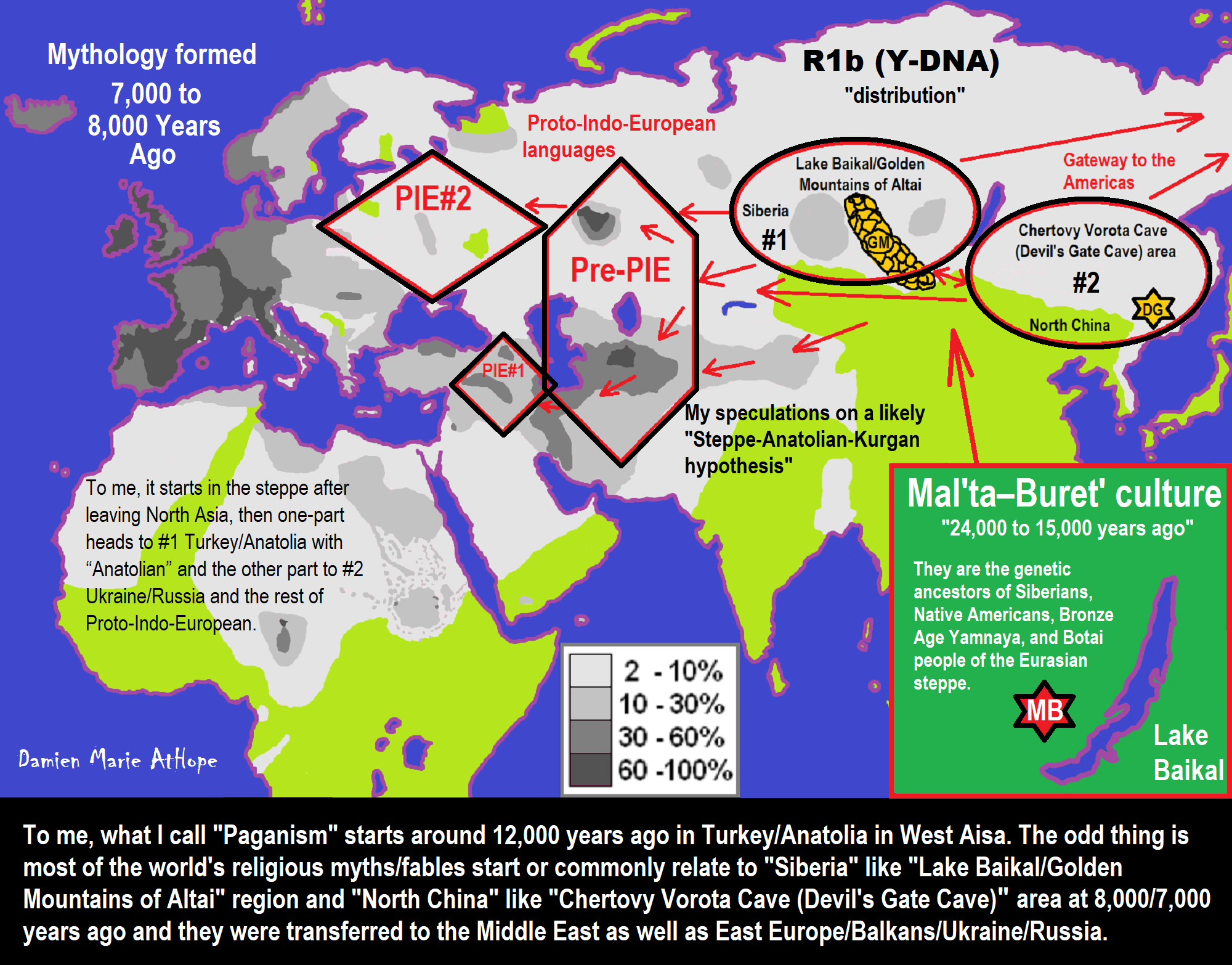

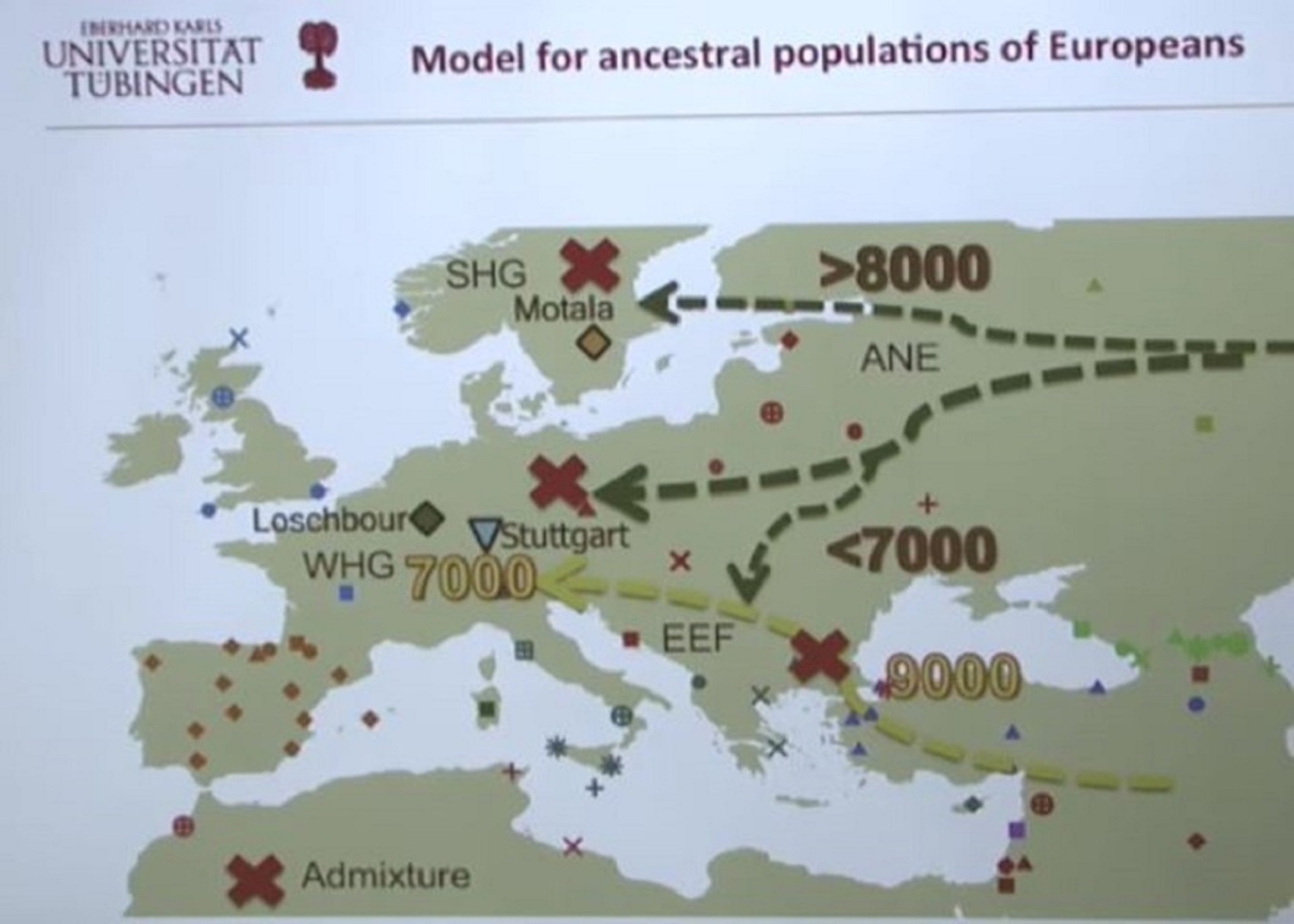

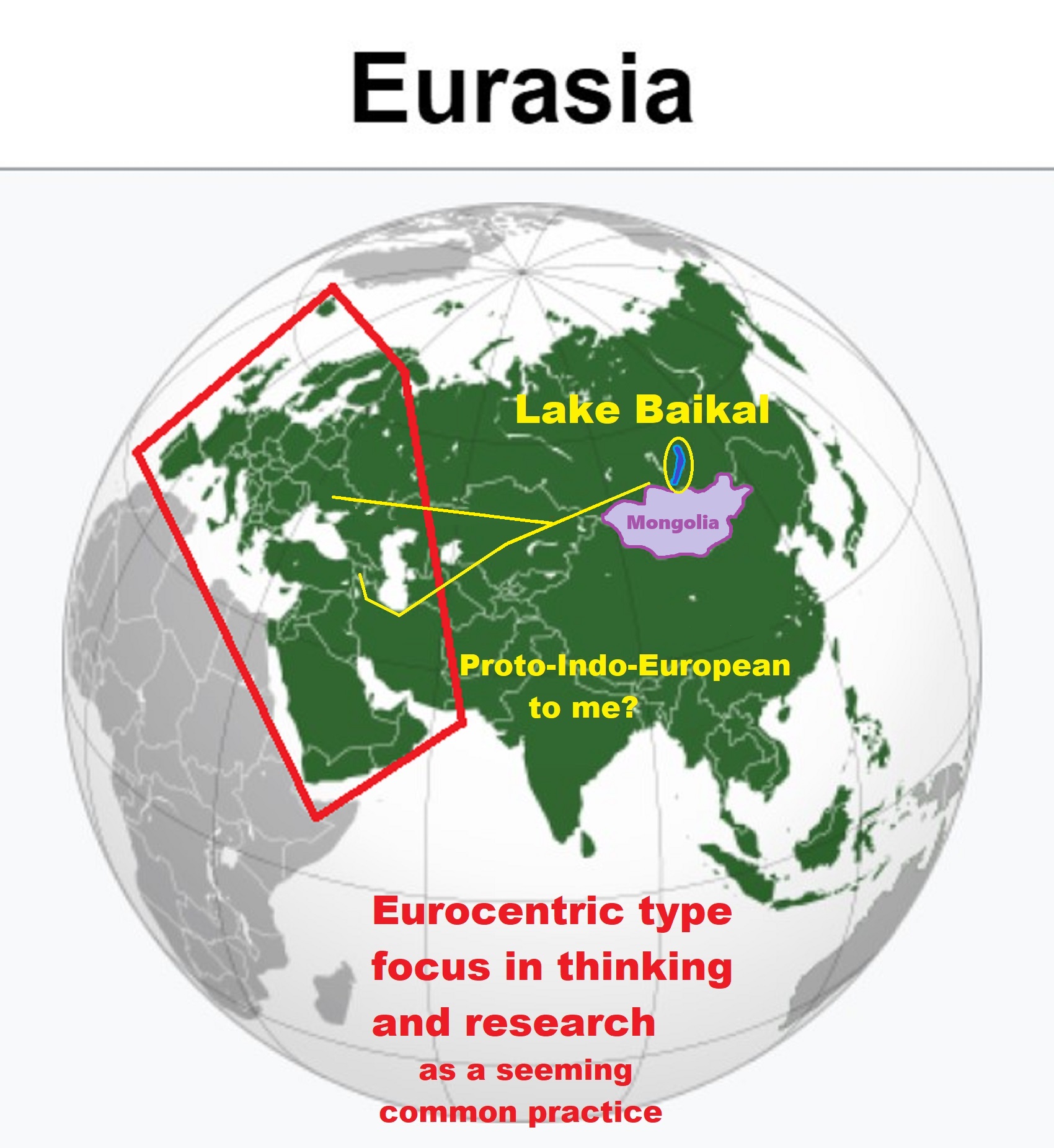

Much of this doesn’t really matter anymore. When I first wrote this page there was still some chance that PIE was spread early from Anatolia with pre-wheel farmers, and I had some sympathy with this view. However, there is now a convincing genetic case for wheels being present at least during the time that all PIE languages except Anatolian were connected. So there’s no reason to think that late PIE speakers didn’t share (in some form) words for wheels. There are, of course, other lines of evidence, such as the IE word for wool (*h2/3wlh1-), also used to argue a late date for PIE. Despite this, I find myself surprised. Some archaeologists have, over the years, used words provided for them by linguists, such as those derived from *kwekwlo-, to make a case for the late date of PIE. In the case of Indo-Iranian and it’s links to Germanic this seems reasonable. However, this argument seems much more debatable for uniting Tocharian and Greek in the same time frame.” ref

“Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying that Greek and Tocharian wheel words did not derive from PIE forms. I’m just saying that the case, always stated as watertight by people like David Anthony, seems anything but. What I’d now argue is that linguists should be tested on such things by being prepared to be asked ‘damn-fool’ questions by idiot students like me. Its benefits, like any teacher knows, are that it would: 1) improve their own understanding of PIE; 2) increase their engagement with others outside the profession (such as Colin Renfrew) and, 3) improve the students’ (i.e. the archaeologists’) understanding.” ref

1. 6,000-year-old Mehrgarh Spoked Wheel Amulet

“The 6,000-year-old amulet from Mehrgarh (Baluchistan, Pakistan), is currently identified as the oldest known artifact made by lost-wax casting and providing a better understanding of this fundamental invention.” ref

“Mehrgarh is a Neolithic site (dated c. 7000 BCE to c. 2500/2000 BCE or 9,020-4,520/4,020 years ago), which lies on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan, Pakistan. Mehrgarh is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River valley, and between the present-day Pakistani cities of Quetta, Kalat, and Sibi. Archaeological material has been found in six mounds, and about 32,000 artifacts have been collected. The earliest settlement at Mehrgarh—in the northeast corner of the 495-acre (2.00 km2) site—was a small farming village dated between 7000 to 5500 BCE or 9,020-7,520 years ago.” ref

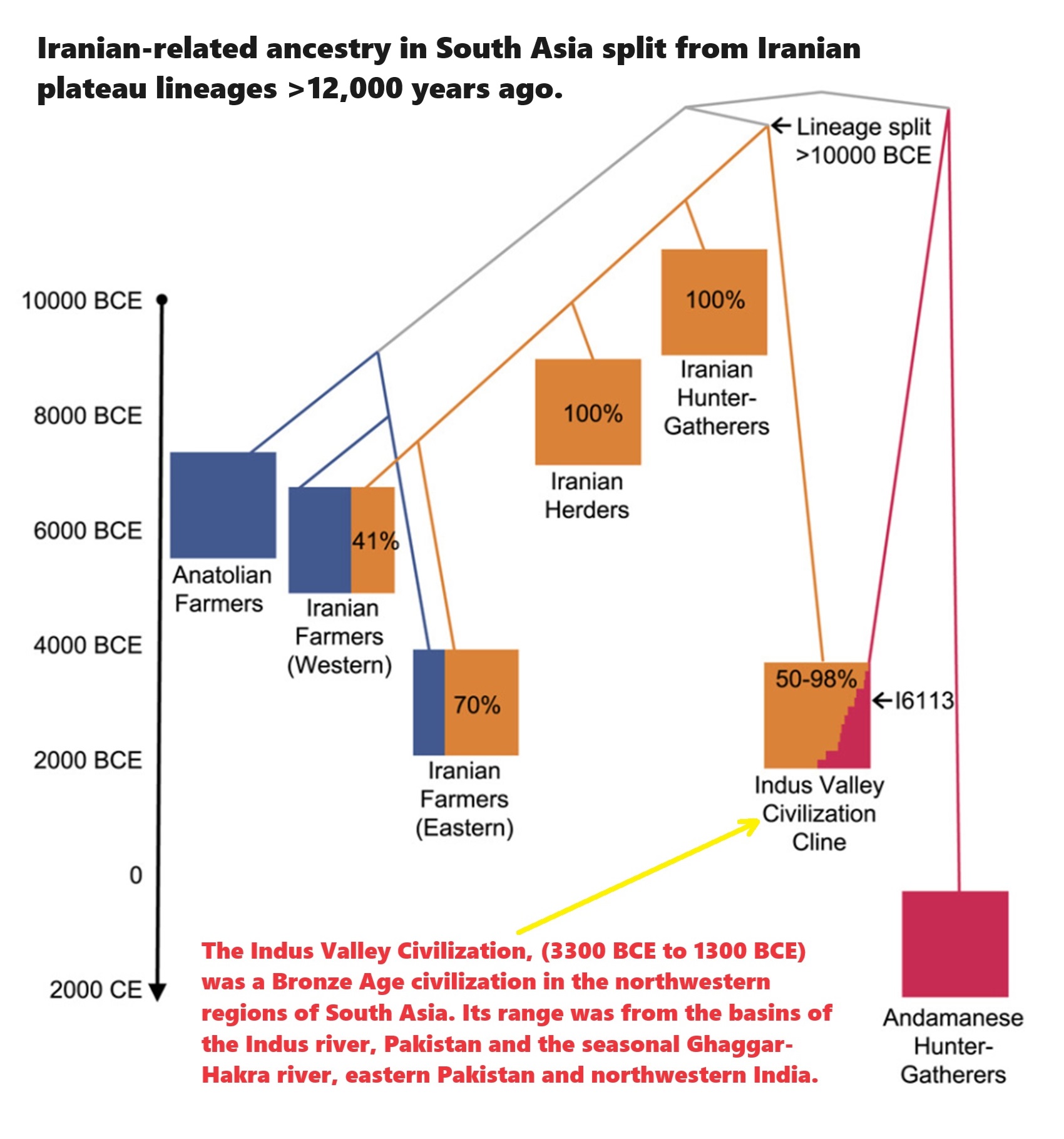

“Mehrgarh is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming and herding in South Asia. Mehrgarh was influenced by the Near Eastern Neolithic, with similarities between “domesticated wheat varieties, early phases of farming, pottery, other archaeological artifacts, some domesticated plants and herd animals.” According to Parpola, the culture migrated into the Indus Valley and became the Indus Valley Civilisation. Jean-Francois Jarrige argues for an independent origin of Mehrgarh. Jarrige notes “the assumption that farming economy was introduced full-fledged from Near-East to South Asia,” and the similarities between Neolithic sites from eastern Mesopotamia and the western Indus valley, which are evidence of a “cultural continuum” between those sites. But given the originality of Mehrgarh, Jarrige concludes that Mehrgarh has an earlier local background,” and is not a “‘backwater’ of the Neolithic culture of the Near East.” ref

“Lukacs and Hemphill suggest an initial local development of Mehrgarh, with a continuity in cultural development but a change in population. According to Lukacs and Hemphill, while there is a strong continuity between the neolithic and chalcolithic (Copper Age) cultures of Mehrgarh, dental evidence shows that the chalcolithic population did not descend from the neolithic population of Mehrgarh, which “suggests moderate levels of gene flow.” They wrote that “the direct lineal descendents of the Neolithic inhabitants of Mehrgarh are to be found to the south and the east of Mehrgarh, in northwestern India and the western edge of the Deccan plateau,” with neolithic Mehrgarh showing greater affinity with chalcolithic Inamgaon, south of Mehrgarh, than with chalcolithic Mehrgarh.” ref

“Gallego Romero et al. state that their research on lactose tolerance in India suggests that “the west Eurasian genetic contribution identified by Reich et al. principally reflects gene flow from Iran and the Middle East.” Gallego Romero notes that Indians who are lactose-tolerant show a genetic pattern regarding this tolerance which is “characteristic of the common European mutation.” According to Romero, this suggests that “the most common lactose tolerance mutation made a two-way migration out of the Middle East less than 10,000 years ago. While the mutation spread across Europe, another explorer must have brought the mutation eastward to India – likely traveling along the coast of the Persian Gulf where other pockets of the same mutation have been found.” They further note that “[t]he earliest evidence of cattle herding in south Asia comes from the Indus River Valley site of Mehrgarh and is dated to 7,000 YBP.” ref

Periods of occupation

Mehrgarh Period I (pre-7000 BCE-5500 BCE)

“The Mehrgarh Period I (pre-7000 BCE-5500 BCE) was Neolithic and aceramic, without the use of pottery. The earliest farming in the area was developed by semi-nomadic people using plants such as wheat and barley and animals such as sheep, goats, and cattle. The settlement was established with unbaked mud-brick buildings and most of them had four internal subdivisions. Numerous burials have been found, many with elaborate goods such as baskets, stone and bone tools, beads, bangles, pendants, and occasionally animal sacrifices, with more goods left with burials of males. Ornaments of sea shell, limestone, turquoise, lapis lazuli, and sandstone have been found, along with simple figurines of women and animals. Sea shells from far sea shore and lapis lazuli found as far away as present-day Badakshan, Afghanistan shows good contact with those areas. A single ground stone ax was discovered in a burial, and several more were obtained from the surface. These ground stone axes are the earliest to come from a stratified context in South Asia. Periods I, II, and III are considered contemporaneous with another site called Kili Gul Mohammad. The aceramic Neolithic phase in the region is now called ‘Kili Gul Muhammad phase’, and it is dated 7000-5000 BC. Yet the Kili Gul Muhammad site, itself, may have started c. 5500 BCE or 7,520 years ago.” ref

Mehrgarh Period II (5500 BCE–4800 BCE) and Period III (4800 BCE–3500 BCE)

“The Mehrgarh Period II (5500 BCE–4800 BCE) and Merhgarh Period III (4800 BCE–3500 BCE) were ceramic Neolithic, using pottery, and later chalcolithic. Period II is at site MR4 and Period III is at MR2. Much evidence of manufacturing activity has been found and more advanced techniques were used. Glazed faience beads were produced and terracotta figurines became more detailed. Figurines of females were decorated with paint and had diverse hairstyles and ornaments. Two flexed burials were found in Period II with a red ochre cover on the body. The amount of burial goods decreased over time, becoming limited to ornaments and with more goods left with burials of females. The first button seals were produced from terracotta and bone and had geometric designs. Technologies included stone and copper drills, updraft kilns, large pit kilns, and copper melting crucibles. There is further evidence of long-distance trade in Period II: important as an indication of this is the discovery of several beads of lapis lazuli, once again from Badakshan. Mehrgarh Periods II and III are also contemporaneous with an expansion of the settled populations of the borderlands at the western edge of South Asia, including the establishment of settlements like Rana Ghundai, Sheri Khan Tarakai, Sarai Kala, Jalilpur, and Ghaligai.” ref

“In 2001, archaeologists studying the remains of nine men from Mehrgarh made the discovery that the people of this civilization had knowledge of proto-dentistry. In April 2006, it was announced in the scientific journal Nature that the oldest (and first early Neolithic) evidence for the drilling of human teeth in vivo (i.e. in a living person) was found in Mehrgarh. According to the authors, their discoveries point to a tradition of proto-dentistry in the early farming cultures of that region. “Here we describe eleven drilled molar crowns from nine adults discovered in a Neolithic graveyard in Pakistan that dates from 7,500 to 9,000 years ago. These findings provide evidence for a long tradition of a type of proto-dentistry in an early farming culture.” ref

Mehrgarh Periods IV, V and VI (3500 BCE-3000 BCE)

“Period IV was 3500 to 3250 BCE. Period V from 3250 to 3000 BCE and period VI was around 3000 BCE. The site containing Periods IV to VII is designated as MR1.” ref

Mehrgarh Period VII (2600 BCE-2000 BCE)

“Somewhere between 2600 BCE and 2000 BCE, the city seems to have been largely abandoned in favor of the larger and fortified town Nausharo five miles away when the Indus Valley Civilization was in its middle stages of development. Historian Michael Wood suggests this took place around 2500 BCE.” ref

Mehrgarh Period VIII

“The last period is found at the Sibri cemetery, about 8 kilometers from Mehrgarh.” ref

Lifestyle and technology

“Early Mehrgarh residents lived in mud brick houses, stored their grain in granaries, fashioned tools with local copper ore, and lined their large basket containers with bitumen. They cultivated six-row barley, einkorn and emmer wheat, jujubes, and dates, and herded sheep, goats, and cattle. Residents of the later period (5500 BCE to 2600 BCE) put much effort into crafts, including flint knapping, tanning, bead production, and metal working. Mehrgarh is probably the earliest known center of agriculture in South Asia. The oldest known example of the lost-wax technique comes from a 6,000-year-old wheel-shaped copper amulet found at Mehrgarh. The amulet was made from unalloyed copper, an unusual innovation that was later abandoned.” ref

Human figurines

“The oldest ceramic figurines in South Asia were found at Mehrgarh. They occur in all phases of the settlement and were prevalent even before pottery appears. The earliest figurines are quite simple and do not show intricate features. However, they grow in sophistication with time and by 4000 BC begin to show their characteristic hairstyles and typical prominent breasts. One Seated Mother Goddess dates to 3000–2500 BCE or 6,020-4,520 years ago. All the figurines up to this period were female. Male figurines appear only from period VII and gradually become more numerous. Many of the female figurines are holding babies, and were interpreted as depictions of the “mother goddess”. However, due to some difficulties in conclusively identifying these figurines with the “mother goddess”, some scholars prefer using the term “female figurines with likely cultic significance”.” ref

Pottery

“Evidence of pottery begins from Period II. In period III, the finds become much more abundant as the potter’s wheel is introduced, and they show more intricate designs and also animal motifs. The characteristic female figurines appear beginning in Period IV and the finds show more intricate designs and sophistication. Pipal leaf designs are used in decoration from Period VI. Some sophisticated firing techniques were used from Period VI and VII and an area reserved for the pottery industry has been found at mound MR1. However, by Period VIII, the quality and intricacy of designs seem to have suffered due to mass production, and due to a growing interest in bronze and copper vessels.” ref

Burials

“There are two types of burials in the Mehrgarh site. There were individual burials where a single individual was enclosed in narrow mud walls and collective burials with thin mud brick walls within which skeletons of six different individuals were discovered. The bodies in the collective burials were kept in a flexed position and were laid east to west. Child bones were found in large jars or urn burials (4000~3300 BCE).” ref

Metallurgy

“Metal finds have dated as early as Period IIB, with a few copper items.” ref

- Indus Valley Civilization and the list of Indus Valley Civilization sites

- List of inventions and discoveries of the Indus Valley Civilization

2. A partially reconstructed, wheeled toy from the Cucuteni Tripolye B2 culture

“The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture (Romanian: Cultura Cucuteni and Ukrainian: Трипільська культура), also known as the Tripolye culture (Russian: Трипольская культура), is a Neolithic–Eneolithic archaeological culture (c. 5500 to 2750 BCE 7,520-4,770 years ago) of Eastern Europe. It extended from the Carpathian Mountains to the Dniester and Dnieper regions, centered on modern-day Moldova and covering substantial parts of western Ukraine and northeastern Romania, encompassing an area of 350,000 km2 (140,000 sq mi), with a diameter of 500 km (300 mi; roughly from Kyiv in the northeast to Brașov in the southwest). The majority of Cucuteni–Trypillia settlements consisted of high-density, small settlements (spaced 3 to 4 kilometers apart), concentrated mainly in the Siret, Prut, and Dniester river valleys.” ref

“During the Middle Trypillia phase (c. 4000 to 3500 BCE), populations belonging to the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture built the largest settlements in Neolithic Europe, some of which contained as many as three thousand structures and were possibly inhabited by 20,000 to 46,000 people. One of the most notable aspects of this culture was the periodic destruction of settlements, with each single-habitation site having a lifetime of roughly 60 to 80 years. The purpose of burning these settlements is a subject of debate among scholars; some of the settlements were reconstructed several times on top of earlier habitational levels, preserving the shape and the orientation of the older buildings. One particular location; the Poduri site in Romania, revealed thirteen habitation levels that were constructed on top of each other over many years.” ref

The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture flourished in the territory of what is now Moldova, northeastern Romania, and parts of Western, Central, and Southern Ukraine. The culture thus extended northeast from the Danube river basin around the Iron Gates to the Black Sea and the Dnieper. It encompassed the central Carpathian Mountains as well as the plains, steppe, and forest steppe on either side of the range. Its historical core lay around the middle to upper Dniester (the Podolian Upland). During the Atlantic and Subboreal climatic periods in which the culture flourished, Europe was at its warmest and moistest since the end of the last Ice Age, creating favorable conditions for agriculture in this region. As of 2003, about 3,000 cultural sites have been identified, ranging from small villages to “vast settlements consisting of hundreds of dwellings surrounded by multiple ditches”.” ref

“Traditionally separate schemes of periodization have been used for the Ukrainian Trypillia and Romanian Cucuteni variants of the culture. The Cucuteni scheme, proposed by the German archaeologist Hubert Schmidt in 1932, distinguished three cultures: Pre-Cucuteni, Cucuteni, and Horodiştea–Folteşti; which were further divided into phases (Pre-Cucuteni I–III and Cucuteni A and B). The Ukrainian scheme was first developed by Tatiana Sergeyevna Passek in 1949 and divided the Trypillia culture into three main phases (A, B, and C) with further sub-phases (BI–II and CI–II). Initially, based on informal ceramic seriation, both schemes have been extended and revised since the first proposed, incorporating new data and formalized mathematical techniques for artifact seriation. The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture is commonly divided into an Early, Middle, Late period, with varying smaller sub-divisions marked by changes in settlement and material culture. A key point of contention lies in how these phases correspond to radiocarbon data.” ref

The following chart represents this most current interpretation:

• Early (Pre-Cucuteni I–III to Cucuteni A–B, Trypillia A to Trypillia BI–II):5800 to 5000 BCE

• Middle (Cucuteni B, Trypillia BII to CI–II): 5000 to 3500 BCE

• Late (Horodiştea–Folteşti, Trypillia CII): 3500 to 3000 BCE ref

Early period (5800–5000 BCE)

“The roots of Cucuteni–Trypillia culture can be found in the Starčevo–Körös–Criș and Vinča cultures of the 6th to 5th millennia, with additional influence from the Bug–Dniester culture (6500–5000 BC). During the early period of its existence (in the fifth millennium BCE), the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture was also influenced by the Linear Pottery culture from the north, and by the Boian culture from the south. Through colonization and acculturation from these other cultures, the formative Pre-Cucuteni/Trypillia A culture was established. Over the course of the fifth millennium, the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture expanded from its ‘homeland’ in the Prut–Siret region along the eastern foothills of the Carpathian Mountains into the basins and plains of the Dnieper and Southern Bug rivers of central Ukraine. Settlements also developed in the southeastern stretches of the Carpathian Mountains, with the materials known locally as the Ariuşd culture (see also: Prehistory of Transylvania). Most of the settlements were located close to rivers, with fewer settlements located on the plateaus. Most early dwellings took the form of pit-houses, though they were accompanied by an ever-increasing incidence of above-ground clay houses. The floors and hearths of these structures were made of clay, and the walls of clay-plastered wood or reeds. Roofing was made of thatched straw or reeds.” ref

“The inhabitants were involved with animal husbandry, agriculture, fishing, and gathering. Wheat, rye, and peas were grown. Tools included ploughs made of antler, stone, bone, and sharpened sticks. The harvest was collected with scythes made of flint-inlaid blades. The grain was milled into flour by quern-stones. Women were involved in pottery, textile– and garment-making, and played a leading role in community life. Men hunted, herded the livestock, made tools from flint, bone, and stone. Of their livestock, cattle were the most important, with swine, sheep, and goats playing lesser roles. The question of whether or not the horse was domesticated during this time of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture is disputed among historians; horse remains have been found in some of their settlements, but it is unclear whether these remains were from wild horses or domesticated ones.” ref

“Clay statues of females and amulets have been found dating to this period. Copper items, primarily bracelets, rings, and hooks, are occasionally found as well. A hoard of a large number of copper items was discovered in the village of Cărbuna, Moldova, consisting primarily of items of jewelry, which were dated back to the beginning of the fifth millennium BCE. Some historians have used this evidence to support the theory that a social stratification was present in early Cucuteni culture, but this is disputed by others. Pottery remains from this early period are very rarely discovered; the remains that have been found indicate that the ceramics were used after being fired in a kiln. The outer color of the pottery is a smoky grey, with raised and sunken relief decorations. Toward the end of this early Cucuteni–Trypillia period, the pottery begins to be painted before firing. The white-painting technique found on some of the pottery from this period was imported from the earlier and contemporary (5th millennium) Gumelnița–Karanovo culture. Historians point to this transition to kiln-fired, white-painted pottery as the turning point for when the Pre-Cucuteni culture ended and Cucuteni Phase (or Cucuteni–Trypillia culture) began. Cucuteni and the neighbouring Gumelniţa–Karanovo cultures seem to be largely contemporary; the “Cucuteni A phase seems to be very long (4600–4050) and covers the entire evolution of the Gumelnița–Karanovo A1, A2, B2 phases (maybe 4650–4050).” ref

Middle period (4000–3500 BC)

“In the middle era, the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture spread over a wide area from Eastern Transylvania in the west to the Dnieper River in the east. During this period, the population immigrated into and settled along the banks of the upper and middle regions of the Right Bank (or western side) of the Dnieper River, in present-day Ukraine. The population grew considerably during this time, resulting in settlements being established on plateaus, near major rivers and springs. Their dwellings were built by placing vertical poles in the form of circles or ovals. The construction techniques incorporated log floors covered in clay, wattle-and-daub walls that were woven from pliable branches and covered in clay, and a clay oven, which was situated in the center of the dwelling. As the population in this area grew, more land was put under cultivation. Hunting supplemented the practice of animal husbandry of domestic livestock.” ref

“Tools made of flint, rock, clay, wood, and bones continued to be used for cultivation and other chores. Much less common than other materials, copper axes and other tools have been discovered that were made from ore mined in Volyn, Ukraine, as well as some deposits along the Dnieper river. Pottery-making by this time had become sophisticated, however, they still relied on techniques of making pottery by hand (the potter’s wheel was not used yet). Characteristics of the Cucuteni–Trypillia pottery included a monochromic spiral design, painted with black paint on a yellow and red base. Large pear-shaped pottery for the storage of grain, dining plates, and other goods, was also prevalent. Additionally, ceramic statues of female “goddess” figures, as well as figurines of animals and models of houses dating to this period have also been discovered. Some scholars have used the abundance of these clay female fetish statues to base the theory that this culture was matriarchal in nature. Indeed, it was partially the archaeological evidence from Cucuteni–Trypillia culture that inspired Marija Gimbutas, Joseph Campbell, and some latter 20th-century feminists to set forth the popular theory of an Old European culture of peaceful, egalitarian (counter to a widespread misconception, “matristic” not matriarchal), goddess-centred neolithic European societies that were wiped out by patriarchal, Sky Father-worshipping, warlike, Bronze-Age Proto-Indo-European tribes that swept out of the steppes north and east of the Black Sea.” ref

Late period (3500–3000 BC)

“During the late period, the Cucuteni–Trypillia territory expanded to include the Volyn region in northwest Ukraine, the Sluch and Horyn Rivers in northern Ukraine, and along both banks of the Dnieper river near Kyiv. Members of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture who lived along the coastal regions near the Black Sea came into contact with other cultures. Animal husbandry increased in importance, as hunting diminished; horses also became more important. Outlying communities were established on the Don and Volga rivers in present-day Russia. Dwellings were constructed differently from previous periods, and a new rope-like design replaced the older spiral-patterned designs on the pottery. Different forms of ritual burial were developed where the deceased were interred in the ground with elaborate burial rituals. An increasingly larger number of Bronze Age artifacts originating from other lands were found as the end of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture drew near.” ref

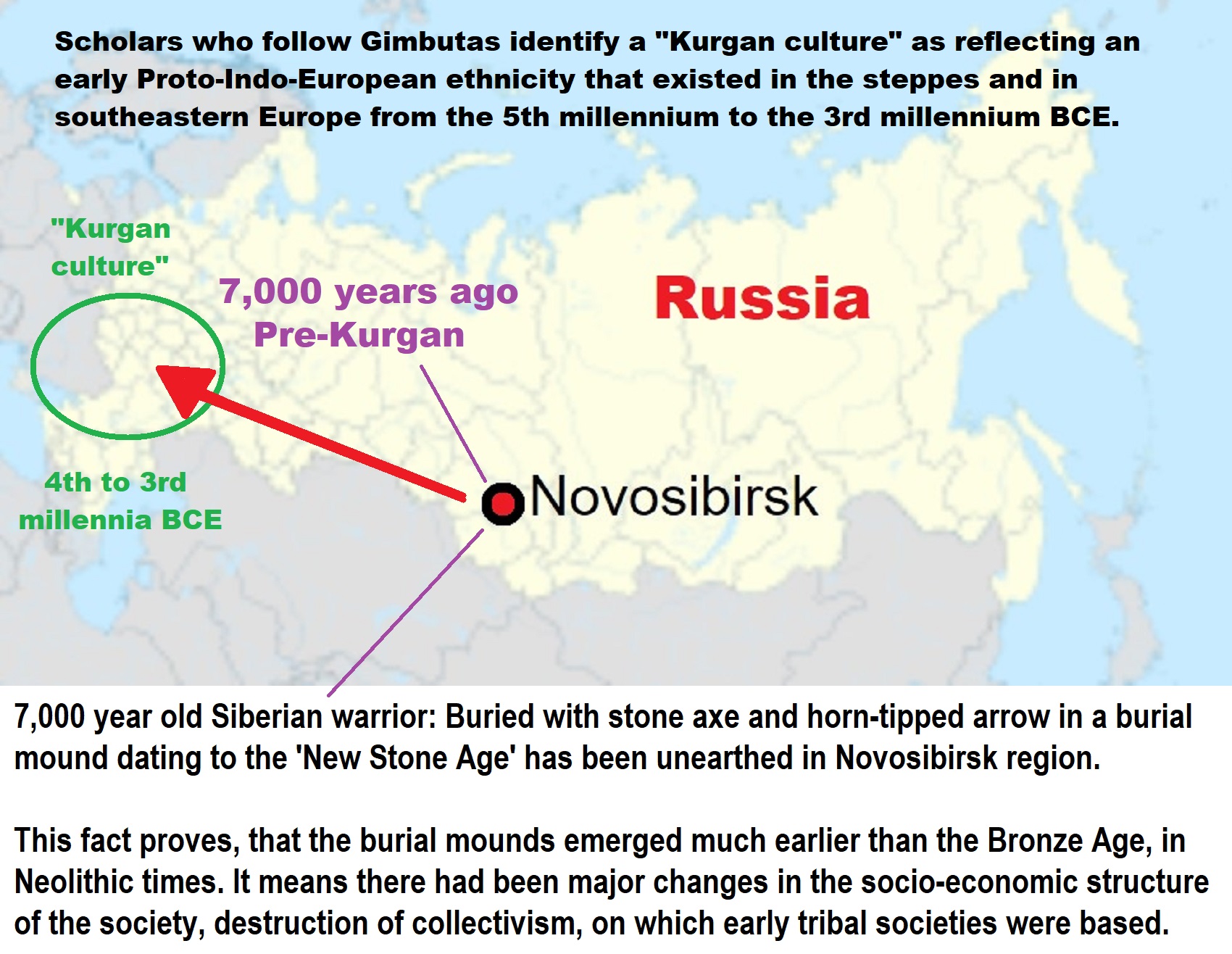

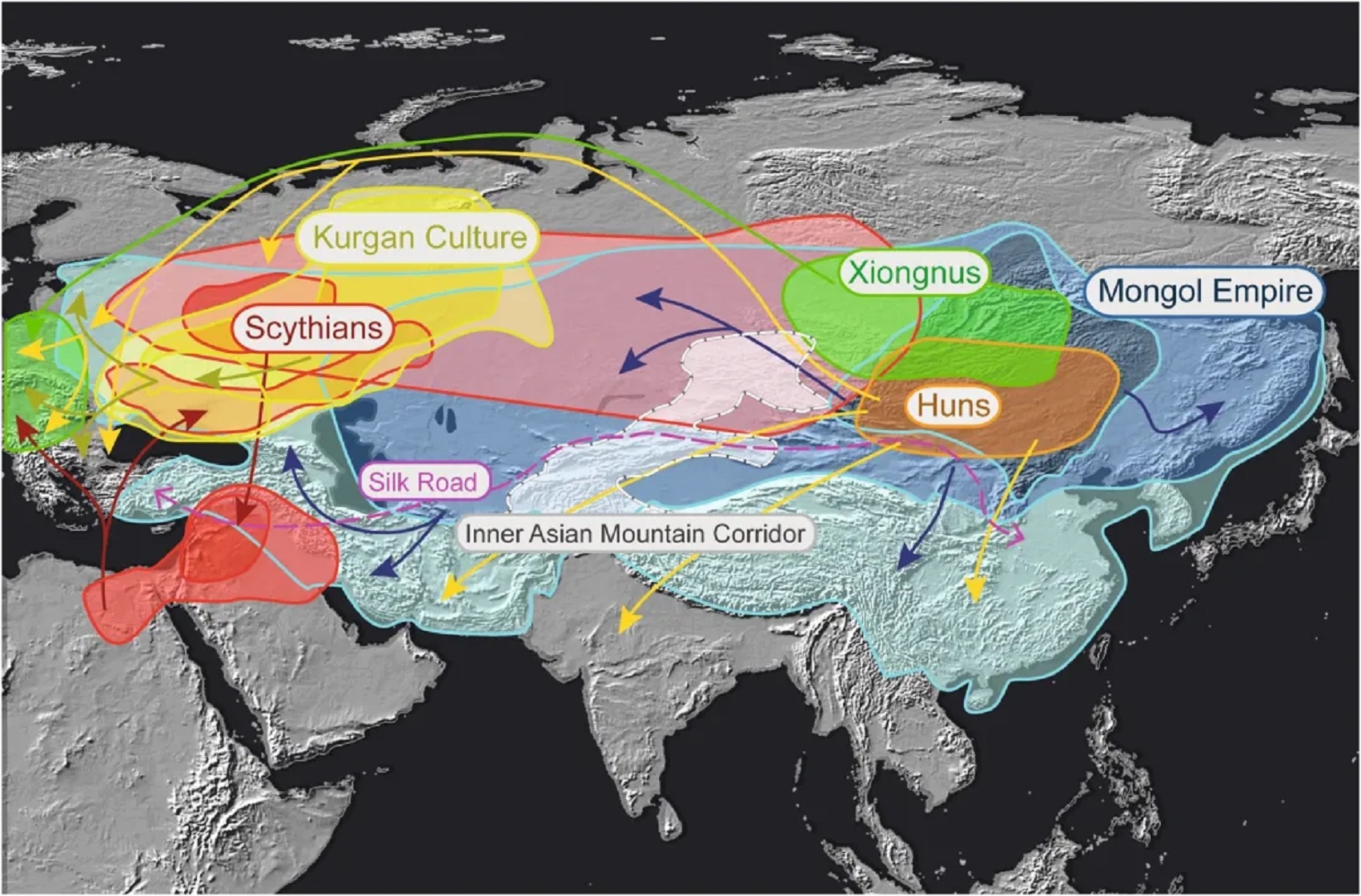

Decline and end: Decline and end of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture

“There is a debate among scholars regarding how the end of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture took place. According to some proponents of the Kurgan hypothesis of the origin of Proto-Indo-Europeans, and in particular the archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, in her book “Notes on the chronology and expansion of the Pit-Grave Culture” (1961, later expanded by her and others), the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture was destroyed by force. Arguing from archaeological and linguistic evidence, Gimbutas concluded that the people of the Kurgan culture (a term grouping the Yamnaya culture and its predecessors) of the Pontic–Caspian steppe, being most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language, effectively destroyed the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture in a series of invasions undertaken during their expansion to the west. Based on this archaeological evidence Gimbutas saw distinct cultural differences between the patriarchal, warlike Kurgan culture and the more peaceful egalitarian Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, which she argued was a significant component of the “Old European cultures” which finally met extinction in a process visible in the progressing appearance of fortified settlements, hillforts and the graves of warrior-chieftains, as well as in the religious transformation from the matriarchy to patriarchy, in a correlated east–west movement. In this, “the process of Indo-Europeanization was a cultural, not a physical, transformation and must be understood as a military victory in terms of successfully imposing a new administrative system, language, and religion upon the indigenous groups.” ref

“Accordingly, these proponents of the Kurgan hypothesis hold that this invasion took place during the third wave of Kurgan expansion between 3000–2800 BC, permanently ending the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture. In his 1989 book In Search of the Indo-Europeans, Irish-American archaeologist J. P. Mallory, summarising the three existing theories concerning the end of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, mentions that archaeological findings in the region indicate Kurgan (i.e. Yamnaya culture) settlements in the eastern part of the Cucuteni–Trypillia area, co-existing for some time with those of the Cucuteni–Trypillia. Artifacts from both cultures found within each of their respective archaeological settlement sites attest to an open trade in goods for a period, though he points out that the archaeological evidence clearly points to what he termed “a dark age,” its population seeking refuge in every direction except east. He cites evidence of the refugees having used caves, islands, and hilltops (abandoning in the process 600–700 settlements) to argue for the possibility of a gradual transformation rather than an armed onslaught bringing about cultural extinction.” ref

“The obvious issue with that theory is the limited common historical life-time between the Cucuteni–Trypillia (4800–3000 BC) and the Yamnaya culture (3300–2600 BC); given that the earliest archaeological findings of the Yamnaya culture are located in the Volga–Don basin, not in the Dniester and Dnieper area where the cultures came in touch, while the Yamnaya culture came to its full extension in the Pontic steppe at the earliest around 3000 BC, the time the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture ended, thus indicating an extremely short survival after coming in contact with the Yamnaya culture. Another contradicting indication is that the kurgans that replaced the traditional horizontal graves in the area now contain human remains of a fairly diversified skeletal type approximately ten centimeters taller on average than the previous population. In the 1990s and 2000s, another theory regarding the end of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture emerged based on climatic change that took place at the end of their culture’s existence that is known as the Blytt–Sernander Sub-Boreal phase. Beginning around 3200 BC, the earth’s climate became colder and drier than it had ever been since the end of the last Ice age, resulting in the worst drought in the history of Europe since the beginning of agriculture. The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture relied primarily on farming, which would have collapsed under these climatic conditions in a scenario similar to the Dust Bowl of the American Midwest in the 1930s.” ref

“According to The American Geographical Union, The transition to today’s arid climate was not gradual, but occurred in two specific episodes. The first, which was less severe, occurred between 6,700 and 5,500 years ago. The second, which was brutal, lasted from 4,000 to 3,600 years ago. Summer temperatures increased sharply, and precipitation decreased, according to carbon-14 dating. According to that theory, the neighboring Yamnaya culture people were pastoralists, and were able to maintain their survival much more effectively in drought conditions. This has led some scholars to come to the conclusion that the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture ended not violently, but as a matter of survival, converting their economy from agriculture to pastoralism, and becoming integrated into the Yamnaya culture.” ref

“However, the Blytt–Sernander approach as a way to identify stages of technology in Europe with specific climate periods is an oversimplification not generally accepted. A conflict with that theoretical possibility is that during the warm Atlantic period, Denmark was occupied by Mesolithic cultures, rather than Neolithic, notwithstanding the climatic evidence.[citation needed] Moreover, the technology stages varied widely globally. To this must be added that the first period of the climate transformation ended 500 years before the end of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture and the second approximately 1400 years after.” ref

Economy: Economy of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture

“Throughout the 2,750 years of its existence, the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture was fairly stable and static; however, there were changes that took place. This article addresses some of these changes that have to do with the economic aspects. These include the basic economic conditions of the culture, the development of trade, interaction with other cultures, and the apparent use of barter tokens, an early form of money.” ref

“Members of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture shared common features with other Neolithic societies, including:

- An almost nonexistent social stratification

- Lack of a political elite

- Rudimentary economy, most likely a subsistence or gift economy

- Pastoralists and subsistence farmers” ref

Earlier societies of hunter-gatherer tribes had no social stratification, and later societies of the Bronze Age had noticeable social stratification, which saw the creation of occupational specialization, the state and social classes of individuals who were of the elite ruling or religious classes, full-time warriors, and wealthy merchants, contrasted with those individuals on the other end of the economic spectrum who were poor, enslaved and hungry. In between these two economic models (the hunter-gatherer tribes and Bronze Age civilizations), we find the later Neolithic and Eneolithic societies such as the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, where the first indications of social stratification began to be found. However, it would be a mistake to overemphasize the impact of social stratification in the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, since it was still (even in its later phases) very much an egalitarian society. And of course, social stratification was just one of the many aspects of what is regarded as a fully established a more civilized society, which began to appear in the Bronze Age.” ref

“Like other Neolithic societies, the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture had almost no division of labor. Although this culture’s settlements sometimes grew to become the largest on Earth at the time (up to 15,000 people in the largest), there is no evidence that has been discovered of labor specialization. Every household probably had members of the extended family who would work in the fields to raise crops, go to the woods to hunt game and bring back firewood, work by the river to bring back clay or fish, and all of the other duties that would be needed to survive. Contrary to popular belief, the Neolithic people experienced a considerable abundance of food and other resources. Since every household was almost entirely self-sufficient, there was very little need for trade. However, there were certain mineral resources that, because of limitations due to distance and prevalence, did form the rudimentary foundation for a trade network that towards the end of the culture began to develop into a more complex system, as is attested to by an increasing number of artifacts from other cultures that have been dated to the later period.” ref

“Toward the end of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture’s existence (from roughly 3000 BC to 2750 BC), copper traded from other societies (notably, from the Balkans) began to appear throughout the region, and members of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture began to acquire skills necessary to use it to create various items. Along with the raw copper ore, finished copper tools, hunting weapons, and other artifacts were also brought in from other cultures. This marked the transition from the Neolithic to the Eneolithic, also known as the Chalcolithic or Copper Age. Bronze artifacts began to show up in archaeological sites toward the very end of the culture. The primitive trade network of this society, that had been slowly growing more complex, was supplanted by the more complex trade network of the Proto-Indo-European culture that eventually replaced the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture.” ref

Pottery

“Most Cucuteni–Trypillia pottery was hand coiled from local clay. Long coils of clay were placed in circles to form first the base and then the walls of the vessel. Once the desired shape and height of the finished product was built up the sides would then be smoothed to create a seamless surface. This technique was the earliest form of pottery shaping and the most common in the Neolithic; however, there is some evidence that they also used a primitive type of slow-turning potter’s wheel, an innovation that did not become common in Europe until the Iron Age. Characteristically vessels were elaborately decorated with swirling patterns and intricate designs. Sometimes decorative incisions were added prior to firing, and sometimes these were filled with colored dye to produce a dimensional effect. In the early period, the colors used to decorate pottery were limited to a rusty-red and white. Later, potters added additional colors to their products and experimented with more advanced ceramic techniques.

“The pigments used to decorate ceramics were based on iron oxide for red hues, calcium carbonate, iron magnetite, and manganese Jacobsite ores for black and calcium silicate for white. The black pigment, which was introduced during the later period of the culture, was a rare commodity: taken from a few sources and circulated (to a limited degree) throughout the region. The probable sources of these pigments were Iacobeni in Romania for the iron magnetite ore and Nikopol in Ukraine for the manganese Jacobsite ore. No traces of the iron magnetite pigment mined in the easternmost limit of the Cucuteni–Trypillia region have been found to be used in ceramics from the western settlements, suggesting exchange throughout the entire cultural area was limited. In addition to mineral sources, pigments derived from organic materials (including bone and wood) were used to create various colors.” ref

“In the late period of Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, kilns with a controlled atmosphere were used for pottery production. These kilns were constructed with two separate chambers—the combustion chamber and the filling chamber— separated by a grate. Temperatures in the combustion chamber could reach 1000–1100 °C but were usually maintained at around 900 °C to achieve a uniform and complete firing of vessels. Toward the end of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, as copper became more readily available, advances in ceramic technology leveled off as more emphasis was placed on developing metallurgical techniques.” ref

Ceramic figurines

“An anthropomorphic ceramic artifact was discovered during an archaeological dig in 1942 on Cetatuia Hill near Bodeşti, Neamţ County, Romania, which became known as the “Cucuteni Frumusica Dance” (after a nearby village of the same name). It was used as a support or stand, and upon its discovery was hailed as a symbolic masterpiece of Cucuteni–Trypillia culture. It is believed that the four stylized feminine silhouettes facing inward in an interlinked circle represented a hora, or ritualistic dance. Similar artifacts were later found in Bereşti and Drăgușeni. Extant figurines excavated at the Cucuteni sites are thought to represent religious artifacts, but their meaning or use is still unknown. Some historians as Gimbutas claim that: …the stiff nude to be representative of death on the basis that the color white is associated with the bone (that which shows after death). Stiff nudes can be found in Hamangia, Karanovo, and Cucuteni cultures.” ref

“No examples of Cucuteni–Trypillia textiles have yet been found – preservation of prehistoric textiles is rare and the region does not have a suitable climate. However, impressions of textiles are found on pottery sherds (because the clay was placed there before it was fired). These show that woven fabrics were common in Cucuteni–Trypillia society. Finds of ceramic weights with drilled holes suggest that these were manufactured with a warp-weighted loom. It has also been suggested that these weights, especially “disposable” examples made from poor quality clay and inadequately fired, were used to weigh down fishing nets. These would probably have been frequently lost, explaining their inferior quality. Other pottery sherds with textile impressions, found at Frumuşica and Cucuteni, suggest that textiles were also knitted (specifically using a technique known as nalbinding).” ref

Weapons and tools

“Cucuteni–Trypillia tools were made from knapped and polished stone, organic materials (bone, antler, and horn), and in the later period, copper. Local Miorcani flint was the most common material for stone tools, but a number of other types are known to have been used, including chert, jasper, and obsidian. Presumably, these tools were hafted with wood, but this is not preserved. Weapons are rare but not unknown, implying the culture was relatively peaceful.” ref

Wheels

“Some researchers, e.g., Asko Parpola, an Indologist at the University of Helsinki in Finland, believe that the CT-culture used the wheel with wagons. However, only miniature models of animals and cups on 4 wheels have been found, and they date to the first half of the fourth millennium BCE. Such models are often thought to have been children’s toys; nevertheless, they do convey the idea that objects could be pulled on wheels. Up to now, there is no evidence for wheels used with real wagons.” ref

Ritual and Religion

“Some Cucuteni–Trypillia communities have been found that contain a special building located in the center of the settlement, which archaeologists have identified as sacred sanctuaries. Artifacts have been found inside these sanctuaries, some of them having been intentionally buried in the ground within the structure, that are clearly of a religious nature, and have provided insights into some of the beliefs, and perhaps some of the rituals and structure, of the members of this society. Additionally, artifacts of an apparent religious nature have also been found within many domestic Cucuteni–Trypillia homes. Many of these artifacts are clay figurines or statues. Archaeologists have identified many of these as fetishes or totems, which are believed to be imbued with powers that can help and protect the people who look after them. These Cucuteni–Trypillia figurines have become known popularly as goddesses; however, this term is not necessarily accurate for all female anthropomorphic clay figurines, as the archaeological evidence suggests that different figurines were used for different purposes (such as for protection), and so are not all representative of a goddess. There have been so many of these figurines discovered in Cucuteni–Trypillia sites that many museums in eastern Europe have a sizeable collection of them, and as a result, they have come to represent one of the more readily identifiable visual markers of this culture to many people.” ref

“The archaeologist Marija Gimbutas based at least part of her Kurgan Hypothesis and Old European culture theories on these Cucuteni–Trypillia clay figurines. Her conclusions, which were always controversial, today are discredited by many scholars, but still, there are some scholars who support her theories about how neolithic societies were matriarchal, non-warlike, and worshipped an “earthy” mother goddess, but were subsequently wiped out by invasions of patriarchal Indo-European tribes who burst out of the steppes of Russia and Kazakhstan beginning around 2500 BC, and who worshipped a warlike Sky God. However, Gimbutas’ theories have been partially discredited by more recent discoveries and analyses. Today there are many scholars who disagree with Gimbutas, pointing to new evidence that suggests a much more complex society during the Neolithic era than she had been accounting for.” ref

Further information: Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses

“One of the unanswered questions regarding the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture is the small number of artefacts associated with funerary rites. Although very large settlements have been explored by archaeologists, the evidence for mortuary activity is almost invisible. Making a distinction between the eastern Trypillia and the western Cucuteni regions of the Cucuteni–Trypillia geographical area, American archaeologist Douglass W. Bailey writes: There are no Cucuteni cemeteries and the Trypillia ones that have been discovered are very late. The discovery of skulls is more frequent than other parts of the body, however, because there has not yet been a comprehensive statistical survey done of all of the skeletal remains discovered at Cucuteni–Trypillia sites, precise post-excavation analysis of these discoveries cannot be accurately determined at this time. Still, many questions remain concerning these issues, as well as why there seems to have been no male remains found at all. The only definite conclusion that can be drawn from archaeological evidence is that in the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, in the vast majority of cases, the bodies were not formally deposited within the settlement area.” ref

Vinča–Turdaș script

Symbols and proto-writing of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture and Vinča symbols

“The mainstream academic theory is that writing first appeared during the Sumerian civilization in southern Mesopotamia, around 3300–3200 BC. in the form of the Cuneiform script. This first writing system did not suddenly appear out of nowhere,[original research?] but gradually developed from less stylized pictographic systems that used ideographic and mnemonic symbols that contained meaning, but did not have the linguistic flexibility of the natural language writing system that the Sumerians first conceived. These earlier symbolic systems have been labeled as proto-writing, examples of which have been discovered in a variety of places around the world, some dating back to the 7th millennium BCE.” ref

“One such early example of a proto-writing system are the Vinča symbols, which is a set of symbols depicted on clay artifacts associated with the Vinča culture, which flourished along the Danube River in the Pannonian Plain, between 6000 and 4000 BC. The first discovery of this script occurred at the archaeological site in the village of Turdaş (Romania), and consisted of a collection of artifacts that had what appeared to be an unknown system of writing. In 1908, more of these same kinds of artifacts were discovered at a site near Vinča, outside the city of Belgrade, Serbia. Scholars subsequently labeled this the “Vinča script” or “Vinča–Turdaş script”. There is a considerable amount of controversy surrounding the Vinča script as to how old it is, as well as whether it should be considered as an actual writing system, an example of proto-writing, or just a collection of meaningful symbols. Indeed, the entire subject regarding every aspect of the Vinča script is fraught with controversy.

“Beginning in 1875 up to the present, archaeologists have found more than a thousand Neolithic era clay artifacts that have examples of symbols similar to the Vinča script scattered widely throughout south-eastern Europe. This includes the discoveries of what appear to be barter tokens, which were used as an early form of currency. Thus it appears that the Vinča or Vinča–Turdaş script is not restricted to just the region around Belgrade, which is where the Vinča culture existed, but that it was spread across most of southeastern Europe, and was used throughout the geographical region of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture. As a result of this widespread use of this set of symbolic representations, historian Marco Merlini has suggested that it be given a name other than the Vinča script, since this implies that it was only used among the Vinča culture around the Pannonian Plain, at the very western edge of the extensive area where examples of this symbolic system have been discovered. Merlini has proposed naming this system the Danube Script, which some scholars have begun to accept. However, even this name change would not be extensive enough, since it does not cover the region in Ukraine, as well as the Balkans, where examples of these symbols are also found. Whatever name is used, however (Vinča script, Vinča–Turdaș script, Vinča symbols, Danube script, or Old European script), it is likely that it is the same system.” ref

Archaeogenetics: Archaeogenetics of Europe

“Nikitin (2011) analyzed mtDNA recovered from Cucuteni–Trypillia human osteological remains found in the Verteba Cave (on the bank of the Seret River, Ternopil Oblast, Ukraine). It revealed that seven of the individuals whose remains where analysed belonged to: two to haplogroup HV(xH), two to haplogroup H, one to haplogroup R0(xHV), one to haplogroup J and one to haplogroup T4, the latter also being the oldest sample of the set. The authors conclude that the population living around Verteba Cave was fairly heterogenous, but that the wide chronological age of the specimens might indicate that the heterogeneity might have been due to natural population flow during this timeframe. The authors also link the R0(xHV) and HV(xH) haplogroups with European Paleolithic populations, and consider the T4 and J haplogroups as hallmarks of Neolithic demic intrusions from the southeast (the north-pontic region) rather than from the west (i.e. the Linear Pottery culture). A 2017 ancient DNA study found evidence of genetic contact between the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture and steppe populations from the east from as early as 3600 BCE, well before the influx of steppe ancestry into Europe associated with the Yamnaya culture. A 2018 study published in Nature included an analysis of three males from the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture. With respect to Y-DNA, two carried haplogroup G2a2b2a, while one carried G2a. With respect to mtDNA, the males carried H5a, T2b, and HV.” ref

3. Mesopotamian currently the Oldest Wheel

“The oldest existing wheel in Mesopotamia can be dated back to 3500 BCE. The Sumerians first used circular sections of logs as wheels to carry heavy objects, joining them together and rolling them along. Subsequently, they invented the sledge/sled and then combined the two. Eventually, they decided to drill a hole through the frame of the cart and make a place for the axle. Now both the wheels and axles could be used separately. The Sumerians realized that logs which had worn-out centers were more manageable and soon these became wheels which could be connected to a chariot.” ref

Primitive wheel form

“In its primitive form, a wheel is a circular block of a hard and durable material at whose center has been bored a hole through which is placed an axle bearing about which the wheel rotates when torque is applied to the wheel about its axis. The wheel and axle assembly can be considered one of the six simple machines. When placed vertically under a load-bearing platform or case, the wheel turning on the horizontal axle makes it possible to transport heavy loads. This arrangement is the main topic of this article, but there are many other applications of a wheel addressed in the corresponding articles: when placed horizontally, the wheel turning on its vertical axle provides the spinning motion used to shape materials (e.g. a potter’s wheel); when mounted on a column connected to a rudder or to the steering mechanism of a wheeled vehicle, it can be used to control the direction of a vessel or vehicle (e.g. a ship’s wheel or steering wheel); when connected to a crank or engine, a wheel can store, release, or transmit energy (e.g. the flywheel). A wheel and axle with force applied to create torque at one radius can translate this to a different force at a different radius, also with a different linear velocity.” ref

“The place and time of an “invention” of the wheel remains unclear, because the oldest hints do not guarantee the existence of real wheeled transport, or are dated with too much scatter. Mesopotamian civilization is credited with the invention of the wheel. The invention of the solid wooden disk wheel falls into the late Neolithic, and may be seen in conjunction with other technological advances that gave rise to the early Bronze Age. This implies the passage of several wheel-less millennia even after the invention of agriculture and of pottery, during the Aceramic Neolithic.

- 4500–3300 BC (Copper Age): the invention of the potter’s wheel; earliest solid wooden wheels (disks with a hole for the axle); earliest wheeled vehicles; domestication of the horse

- 3300–2200 BC (Early Bronze Age)

- 2200–1550 BC (Middle Bronze Age): the invention of the spoked wheel and the chariot” ref

4. Wheel with axle and the Bronocice pot’s Pottery art

“This Ljubljana Marshes Wheel with axle is the oldest wooden wheel yet discovered dating to Copper Age (c. 3,130 BC). The Ljubljana Marshes Wheel is a wooden wheel that was found in the Ljubljana Marshes some 20 kilometers (12 mi) south of Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia. In 2002 Slovenian archaeologists uncovered a wooden wheel some 20 kilometers southeast of Ljubljana. It was established that the wheel is between 5.100 and 5.350 years old. This makes it the oldest in the world ever found.” ref, ref, ref

The archaeological site

“Remains of pile dwellings were discovered in the Ljubljana Marshes as early as in 1875. Since 2011, the site has been protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site as an example of prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps, a special form of dwellings in areas with lakes and marshes. The archaeologists at the excavation site identified over one thousand piles in the bed of the Iška River, near Ig. They reconstructed the dwellings of 3.5 by 7 meters (11 ft 6 in × 23 ft 0 in) in size, separated by approximately 2 to 3 meters (6 ft 7 into 9 ft 10 in). The analyses of the piles revealed that the dwellings were repaired each year and that a new house had to be built on the same place in as little as 10 to 20 years. The earliest inhabitants settled in the region as early as 9,000 years ago. In the Mesolithic, they built temporary residences on isolated rocks in the marsh and on the fringe, living by hunting and gathering. The permanent settlements were not built until the first farmers appeared approximately 6,000 years ago during the Neolithic.” ref

The wooden wheel

“The wooden wheel belonged to a prehistoric two-wheel cart – a pushcart. Similar wheels have been found in the hilly regions of Switzerland and southwest Germany, but the Ljubljana Marshes wheel is bigger and older. It shows that wooden wheels appeared almost simultaneously in Mesopotamia and Europe. It has a diameter of 72 centimeters (28 3⁄8 in) and is made of ash wood, and its 124-centimetre-long (48 7⁄8 in) axle is made of oak. The axle was attached to the wheels with oak wood wedges, which meant that the axle rotated together with the wheels. The wheel was made from a tree that grew in the vicinity of the pile dwellings and at the time of the wheel, construction was approximately 80 years old. It appears that the wheel itself is primarily made of two planks of wood which are held together with four cross braces. The cross braces appear to have been held in place simply by a tenon arrangement, the braces being fitted into tenoned slots carved into the two main wheel sections.” ref

Bronocice pot

“The Bronocice pot, discovered in a village in Gmina Działoszyce, Świetokrzyskie Voivodeship in Małopolska, near Nida River, Poland, is a ceramic vase incised with one of the earliest known depictions of what may be a wheeled vehicle. It was dated by the radiocarbon method to the mid-fourth millennium BCE, and is attributed to the Funnelbeaker archaeological culture. Today it is housed in the Archaeological Museum of Kraków (Muzeum Archeologiczne w Krakowie), Poland. The picture on the pot symbolically depicts key elements of the prehistoric human environment. The most important component of the decoration are five rudimentary representations of what seems to be a wagon. They represent a vehicle with a shaft for a draught animal, and four wheels. The lines connecting them probably represent axles. The circle in the middle possibly symbolizes a container for harvest. Other images on the pot include a tree, a river, and what may be fields intersected by roads/ditches or the layout of a village. The Bronocice pot inscription markings may represent a kind of “pre-writing” symbolic system that was suggested by Marija Gimbutas in her model of Old European language, similar to Vinča culture logographics (5700–4500 BC).” ref