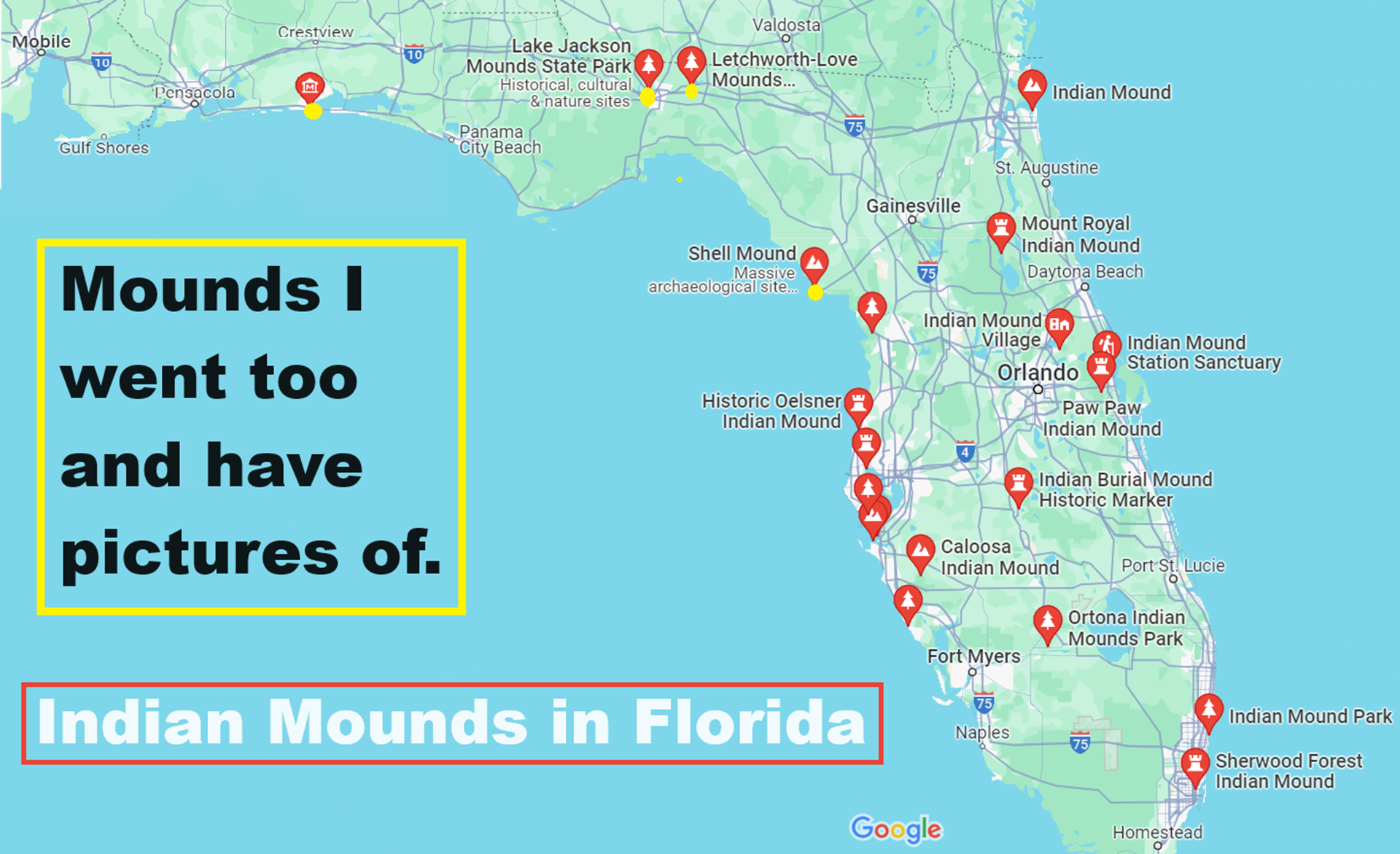

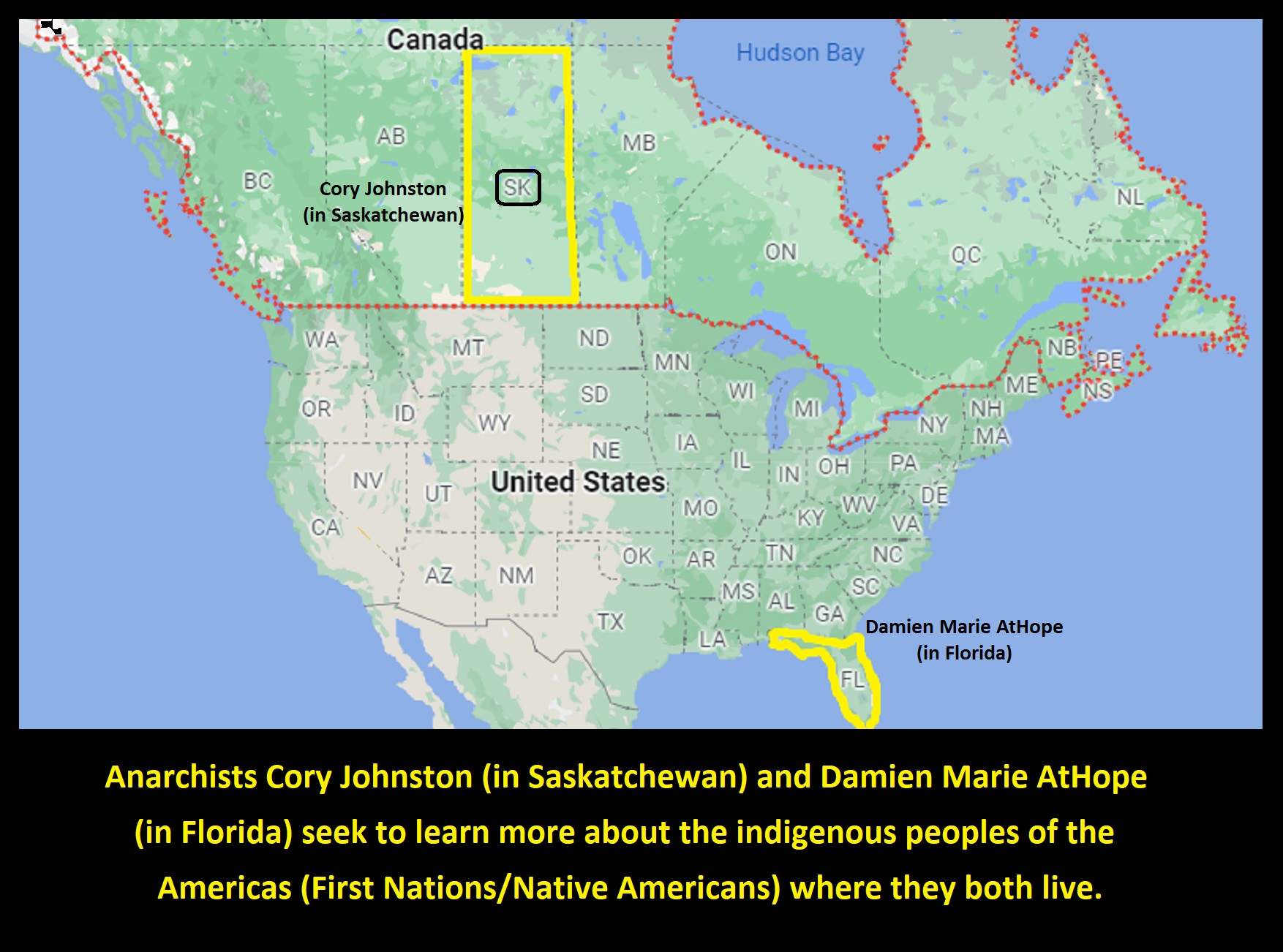

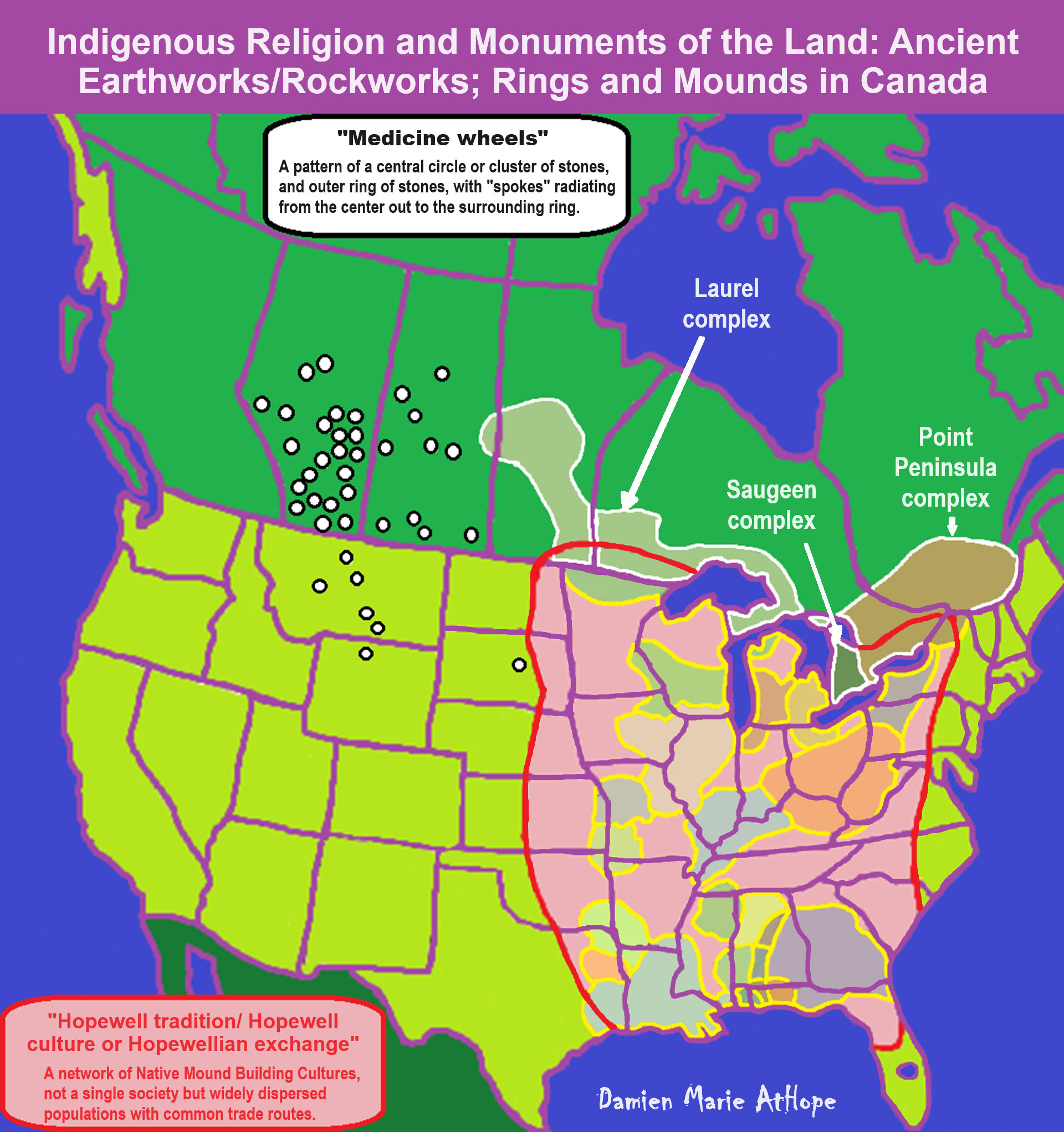

Indigenous Religion and Monuments of the Land: Ancient Earthworks/Rockworks; Rings and Mounds in Canada:

*Rings, such as medicine wheels

*Mounds, such as burial mounds, temple mounds, platform (like elite housing or ritual ceremonies) mounds, and effigy mounds

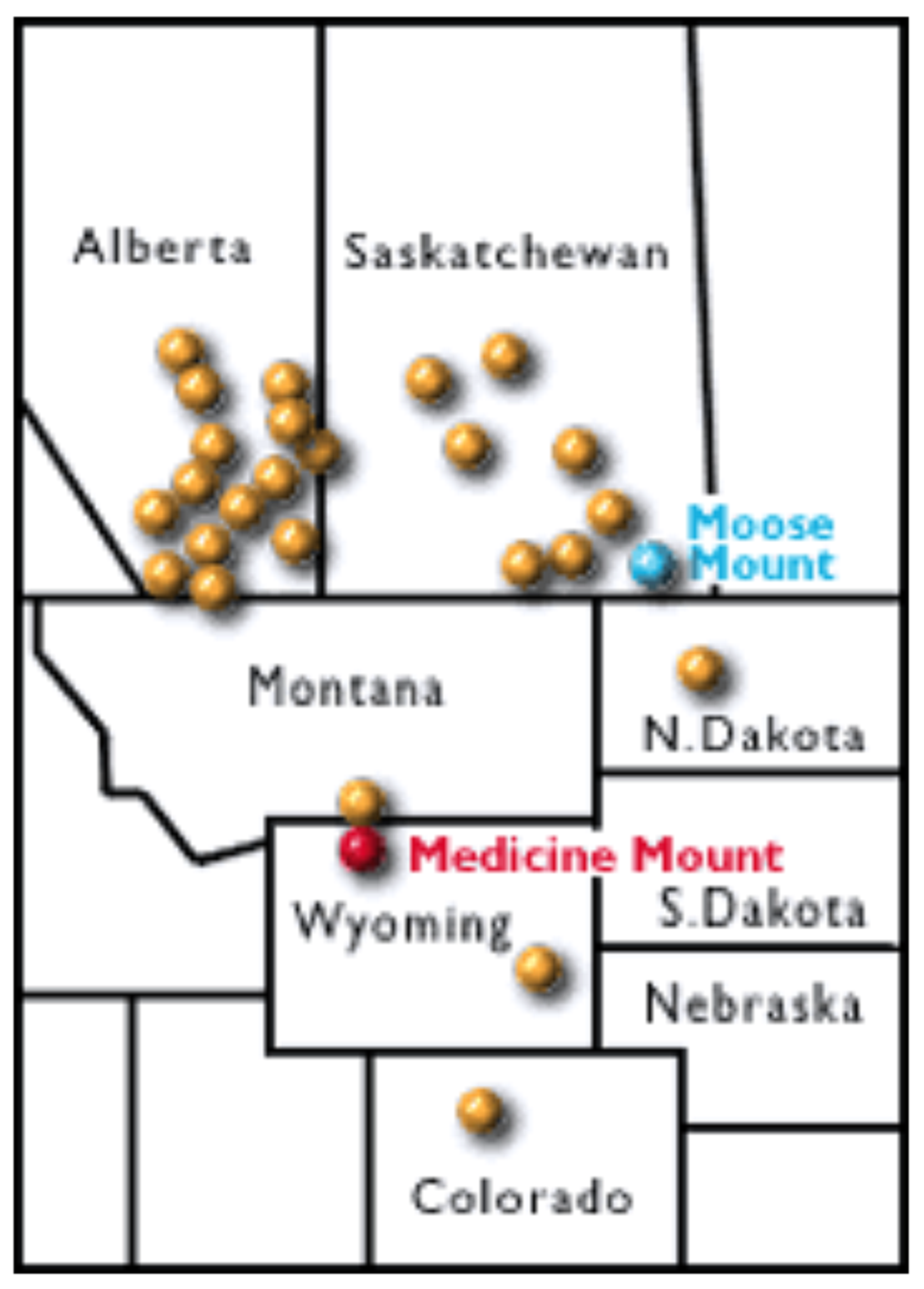

Moose Mountain Medicine Wheel

“On top of a wind-swept hill in southeastern Saskatchewan, there’s a cairn of boulders connected to a large circle of rocks surrounding it by five lines of stones resembling spokes in a wheel. The Moose Mountain Medicine Wheel has been a sacred site for Northern Plains Indians for more than 2,000 years. And yet its origins and purpose remain hidden amid the fog of pre-history. Theories, from the scientific to the other-worldly, abound. But one thing is certain: medicine wheels like the one at Moose Mountain are disappearing, one stone at a time.” ref

“And First Nations peoples and archaeologists, alike, fear they may be gone by the next generation. The Moose Mountain Medicine Wheel was first noted by Canadians of European ancestry in an 1895 report written by land surveyors. The report described the central cairn of the wheel as being about 14 feet high, says Ian Brace, an archaeologist with the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Regina. “The central rock cairn is now about a foot-and-a-half high,” says Brace. “There’ve been people from all points on the globe who’ve not only visited the site, but taken a rock home with them.” ref

“Theft, vandalism and agriculture have reduced to about 170 the number of medicine wheels on the Northern Plains of North America. Brace says he can’t even guess how many wheels once graced the plains. But if the destruction of tipi rings is any indication of the degree of desecration besetting medicine wheels, “in my life time, they might just disappear”. Though medicine wheels are sacred to all plains Indian groups, their symbolism and meaning vary from tribe to tribe.” ref

“The oldest wheels date back about 4,000 years, to the time of the Egyptian pyramids and the English megaliths like Stonehenge. (Moose Mountain has been radio-carbon dated to 800 BCE, however, Brace says it’s possible an older boulder alignment exists beneath the exposed one.) The Blackfoot, first of the current Indian groups on the plains of what are now Saskatchewan and Alberta, arrived about 800 CE.” ref

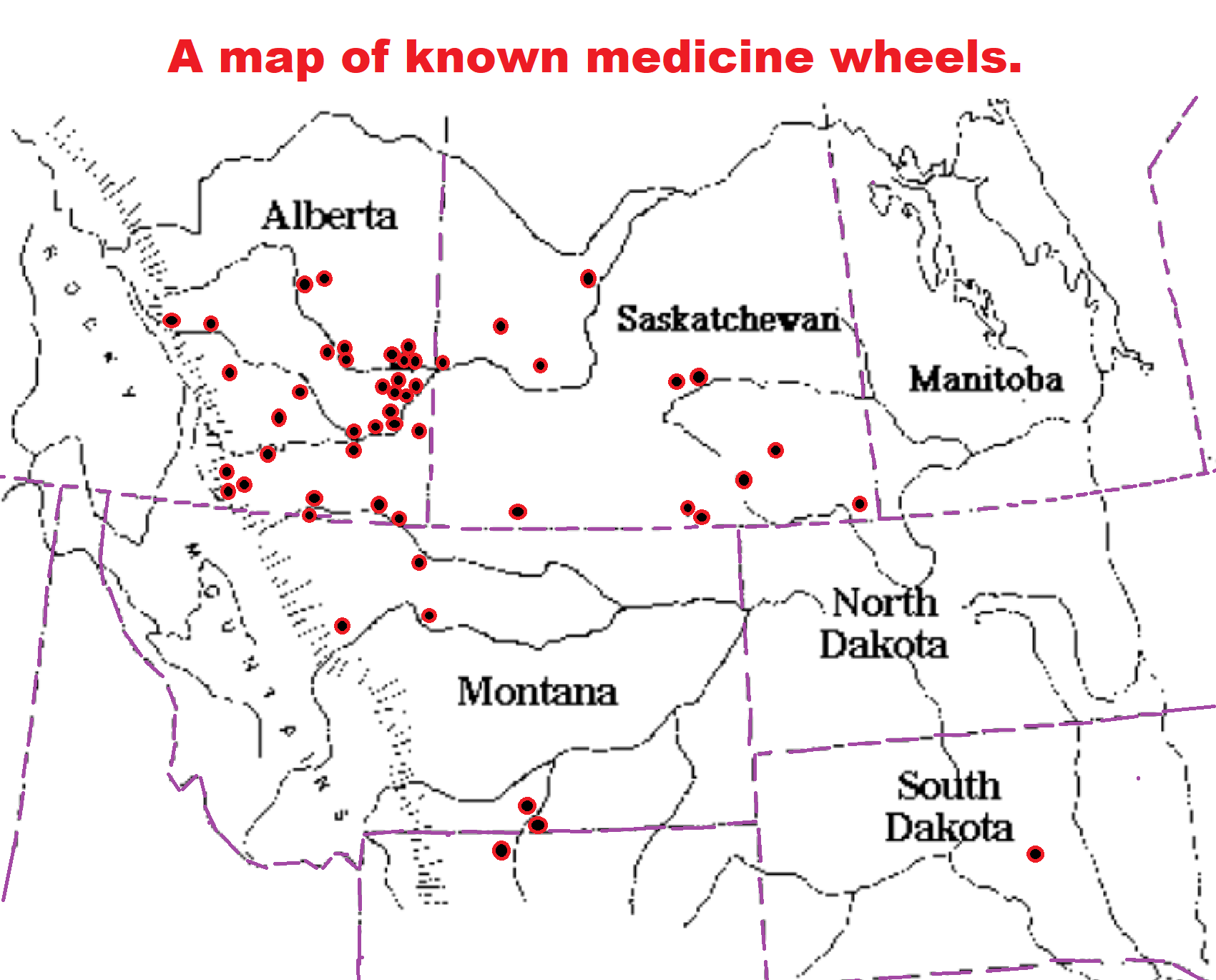

“When the Blackfoot arrived in the new environment it was already populated by two groups of people called the “Tunaxa” and the “Tunaha”, according to Blackfoot oral history. Brace and others believe the three groups assimilated and the Blackfoot carried on the tradition of building medicine wheel monuments. Alberta and Saskatchewan host the majority of known medicine wheels. Others are located in North Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming.” ref

“Like the Blackfoot before them, Indian groups who migrated to the Northern Plains adopted the medicine wheel as a cultural and spiritual icon. Simon Kytwayhat, a Cree elder who lives in Saskatoon, says he learned his Cree perspective on the meaning of the medicine wheel from elders. Kytwayhat’s interpretation associates the four directions represented on the wheel with the four races and their attributes — the circle and the number four are sacred symbols in First Nations’ spirituality.” ref

“South, says Kytwayhat, stands for the color yellow, the Asian people, the Sun, and intellect, while west represents the black race, the color black, the Thunderbird, and emotion. North is associated with the color white, the white man, winter and physicality — “white people sometimes rush into things without considering the consequences” — and east is identified with the color red, the Indian person, spirituality, and the eagle.” ref

“The eagle has great vision, and so do those who follow the spiritual path in life.” Kytwayhat said he used to blame the white man for all the troubles experienced by Indians. “In time, I came to see the real meaning of the medicine wheel is the brotherhood of man. How you treat others comes back to you around the circle.” ref

“If First Nations’ peoples have divergent views on the meaning of the medicine wheel, members of the non-Native community, including scientists, are often poles apart. The Mormon Church believes the wheels were built by the Aztecs, and Swiss author Erich von Daniken contends they’re a link to pre-historic astronauts. New-Agers, meanwhile, embrace them as spiritual symbols and construct their own near existing sites.” ref

“In the 1970s, Colorado astronomer John Eddy proposed wheels like Moose Mountain and Bighorn, in Wyoming, were calendars whose cairns and spokes aligned with celestial markers like Rigel, Aldebaran and Sirius to forecast events like the return of the buffalo. “It’s all over the map,” says Ernie Walker, head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon.” ref

“We don’t know whether some have astronomical alignments or not — if some do, they’re very much in the minority. A lot of (archaeologists) doubt it.” Brace says the astronomical theory is easily debunked by simply imagining someone trying to carry out celestial alignments over the 17-foot crest that separates one side of the Moose Mountain wheel from the other. “Even standing on a horse, you can’t see the other side.”

“Archaeologists and Blackfoot elders appear to agree on at least one kind of medicine wheel. Walker says most archaeologists of the Northern Plains recognize eight different classes or styles of medicine wheels. “Lo-and-behold, the Blackfoot elders have routinely referred to one of these eight styles — although they don’t call it that — and they strongly indicate these were monuments to particular people, or events that happened in the past. I think there’s some consensus on that.” ref

“Brace points out the most recent wheel was constructed in Alberta in 1938, as a memorial to a renowned Blackfoot leader. Brace has come up with a medicine wheel definition that allows him to categorize the 12 to 14 Saskatchewan wheels, which range in diameter from 45 to 144 metres (160 yards), into four groups: burial; surrogate burial; fertility symbol; and “medicine hunting.” ref

“Burial and surrogate burial, as the names imply, are grave sites and memorials. The longest line of boulders in such wheels points to the direction of the honoree’s birth, while shorter ones point to places of courageous acts or remarkable deeds. Fertility wheels have the same pattern of radiating lines and circles employed as fertility symbols on the pottery and birch-bark “bitings” of other pre-historic, North American cultures, he says. The fertility wheels contain buried offerings their builders believed would increase the number of buffalo. “Medicine hunting”, meanwhile, may explain the origin of the Moose Mountain Medicine Wheel, says Brace.” ref

“If the people went into a particular place and they were without resources, they’d take the shoulder blade of the animal they wanted to hunt and put it in the fire. As the bone dried out, it would crack, and at the end of the crack you’d get blobs of fat. “They would interpret (the cracks with the blobs of fat) as indicating the directions they’d have to go to find those food resources, or people who had food to share. The cracks where fat did not accumulate would indicate a poor direction to go.” ref

“Brace suspects the medicine hunting wheel was created, and likely amended over time, to serve as a permanent hunting guide to succeeding generations of nomadic Indians. Permanent, that is, until the white culture came into contact with the red. In the 1980s, the land encompassing the Moose Mountain Medicine Wheel came under the jurisdiction of a First Nation band. Because visitors wishing to view it must first get permission from the band council, at least some degree of security is now assured, says Brace.” ref

“But most of Saskatchewan’s medicine wheels are on Crown, public and privately-owned land. Although they’re “protected” under provincial legislation that allows for fines of up to $3,000 for anyone caught desecrating a medicine wheel, enforcement is difficult. Most of the surviving medicine wheels are situated “off the beaten path”, accessible only to those bent on finding them, says Brace. The same remoteness that protects the wheels from the ravages of high foot traffic, however, also protects the unscrupulous from being caught stealing or vandalizing them.” ref

“It’s a problem that has no easy solution, but Brace says there may be hope in the Indian land-claims process. If ownership of the medicine-wheel sites located on public and Crown land could be transferred to Indian bands, and if Indian families could be induced to reside on the sites, security would be greatly enhanced. In the mean time, people wishing to see a medicine wheel might consider a visit to Wanuskewin Heritage Park, near Saskatoon. There’s no better place to learn about the people to whom the circles remain sacred, and the science that seeks to know why. Readers may also be interested in our story about rock carvings at St. Victor, in south-central Saskatchewan, and rock paintings in northern Saskatchewan on the Churchill River.” ref

“Moose Mountain Upland, Moose Mountain Uplands, or commonly Moose Mountain, is a hilly plateau located in the south-east corner of the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, that covers an area of about 13,000 km2 (5,000 sq mi). The upland rises about 200 m (660 ft) above the broad, flat prairie which is about 600 m (2,000 ft) above sea level. The highest peak is “Moose Mountain” at 830 m (2,720 ft) above sea level. The area was named Moose Mountain because of the large number of moose that lived in the area. When it was originally used by fur traders, Métis, and the Indigenous peoples, the plateau was called Montagne a la Bosse, which is French for “The Mountain of The Bump or Knob.” ref

“Before the most recent continental glaciation 23,000 years ago, Moose Mountain was capped by Tertiary-age gravels. As the ice began to retreat about 17,000 years ago from southern Saskatchewan, the highest hills formed nunataks in the ice sheet. The protrusion of the Moose Mountain Upland initiated an interlobate area between two glacial lobes, the Weyburn Lobe and the Moose Mountain Lobe. On the southern side of the upland, in the interlobate area, a short lived glacial lake named Lake Arcola formed. The Moose Mountain Creek Spillway drained the area southward into the Souris Spillway. As the ice was melting away, large chunks were left behind forming depressions called kettles or potholes (locally, the depressions are called sloughs) in the ground. The retreating ice also left small shallow lakes, knobs, and moraines dotted all over Moose Mountain and the surrounding prairies.” ref

“This region of North America is referred to as the Prairie Pothole Region.

A large portion of the Canadian prairies is classified as having a knob and kettle topography. It is believed that this topography was formed by glacial movement. As the glaciers advanced, till was pushed into mounds in some locations and in other locations large blocks of the glacier ice were buried. After the glacier retreated these large buried blocks of ice melted leaving a depression that geologists call a kettle. These kettles are the wetlands or sloughs that are prevalent on the prairie landscape.” ref

“Indigenous people have lived in the area of southern Saskatchewan for about 11,000 years and were originally nomadic hunters and gatherers. The area provided plenty of big game such as buffalo, deer, and elk as well as a variety of berries such as saskatoons, blueberries, and raspberries and edible plants like wild rice, turnips, and onions. The earliest archaeological evidence of First Nations in the Moose Mountain area is the Moose Mountain Medicine Wheel which carbon dates to about 800 BCE. The Medicine Wheel is located on the plateau’s highest peak and is under jurisdiction of the Pheasant Rump Nations Band.” ref

“From the 1700s a large network of trails were developed that criss-crossed the prairies that the Métis, First Nations, and other fur traders used as a transportation network for furs and other goods. One of the trails, the Fort Ellice–Wood Mountain Trail ran along the east and to the south of the Moose Mountain Upland. It was mainly a provisions trail transporting pemmican from buffalo hunting grounds near Wood Mountain back to Port Ellice. It operated from 1757 to about the 1850s. Since there are no major waterways near Moose Mountain and since beaver are not native to the area (two breeding pairs were introduced in 1923 and thrived), it did not play a significant role in the fur trade. Also, combined with its unsuitability for agriculture, much of the plateau remained in situ until the late 1800s. Even today much of the area remains undeveloped and in a natural state.” ref

“One of the first major trails to be built was the Christopher Trail. It was built from Kenosee Lake to Cannington Manor in the 1890s by the Christopher family, who were German immigrants that had a homestead 7 miles east of Kenosee Lake, and the Fripp brothers who owned land on the north-east corner of Kenosee Lake (where the village of Kenosee Lake sits today). Fred Christopher and his two sons cut through 6.4 kilometres of bush going from east to west and the Fripp brothers, Harold and Percy, started at Kenosee Lake and cut through 4.8 kilometres of bush to meet near the middle. Along the trail, two human skeletons were found near a lake. That lake was named Skeleton Lake. Today, that trail is a well-travelled gravel road that runs from Kenosee Lake to Cannington Manor.” ref

“The first road to Kenosee Lake was built in 1905 and went from about 3 miles west of Carlyle north into the upland past the lakes of McGurk, Stevenson, and Hewitt to the west side of Kenosee Lake, near where the Bible camps are today. At that time, there was a resort on the west side of the lake called Arcola Resort. The south side of Moose Mountain Upland rises sharply above the flat plains while the north side has a more gradual ascent. Compared to the surrounding landscape, the upland, which appears oval in shape when viewed from above, is quite hilly and heavily wooded.” ref

“Moose Mountain at 830 metres above sea level is the highest peak and is located on the south side of the plateau near the middle. Highway 605 passes to the west of it. In the vicinity there are other unnamed hills over 800 metres. The next highest named hill is Heart Hill on the eastern side of the plateau located on White Bear First Nations. It is 774 metres high. The only other named summit in the region is Lost Horse Hill with a much lower elevation than most of the plateau at just over 660 metres. Lost Horse Hill is part of the Lost Horse Hills, which are a cluster of rolling hills partially on the Ocean Man Indian Reserve. These hills are located on the far west side of the plateau at the point where the plateau tapers off, south of Moose Mountain Lake and just west of the junction of Moose Mountain and Wolf Creeks. Highway 47 traverses the eastern slope of Lost Horse Hill.” ref

Moose Mountain

- Location: 49°47′0″N, 102°35′2″W

- 830 meters above sea level

- Prominence: 216 metres

- 27th highest named peak in Saskatchewan

Heart Hill

- Location: 49°45′0″N, 102°12′2″W

- 774 metres above sea level

- Prominence: 37 metres

- 36th highest named peak in Saskatchewan

Lost Horse Hill

- Location: 49°53′0″N, 103°3′2″W

- 660 metres above sea level

- Prominence: 24 metres

- 71st highest named peak in Saskatchewan” ref

“At the heart of Moose Mountain Upland is Moose Mountain Provincial Park, which features the Moose Mountain Chalet and an 18-hole golf course. The development of the park and the building of the Chalet between 1931 and 1933 were part of an effort by the Saskatchewan Government to get people working during the Great Depression. The chalet and golf course were built in tandem with the idea of bringing wealthy people to the park. The largest lake on the plateau, Kenosee Lake, is found in the park. Kenosee Lake is stocked with fish, has a beach area, docks, miniature golf, and camping. Overlooking the lake is the Kenosee Inn & Cabins which features a conference room, 30 hotel rooms, and 23 cabins. Three Christian camps, Kenosee Lake Bible Camp.” ref

“Clearview Christian Camp, and Kenosee Boys & Girls Camp are located on the western shore of the lake in Christopher Bay at the site of the former Arcola Resort. Also on the lake is the village of Kenosee Lake which has services such as a gas station, restaurant, and convenience store. To the east of the village, just off Highway 9, is Kenosee Superslides. There is also a ball diamond and hiking trails. Red Barn Market is located five kilometres north of Kenosee Lake near, the intersection of highways 9 and 48. In the winter there is ice fishing, a tobogganing hill, and sledding. On the White Bear First Nation, there is the Bear Claw Casino & Hotel, Carlyle Lake Resort, and White Bear Lake Golf Course.” ref

“At the far western end of the upland, there are two other parks. At the south end of Moose Mountain Lake by the dam, there’s Lost Horse Hills Heritage Park. It’s a small park with a picnic area and dock and is accessed off Highway 47. At the north end of Moose Mountain Lake on the north side of Highway 711, is Saint Clair National Wildlife Area. It is one of 28 Prairie National Wildlife Areas in Saskatchewan. In 1974 Saskairie, a Nature Conservancy of Canada property, was established on the southern slope of Moose Mountain Upland. It is three-quarters of a section located along the southern border of Moose Mountain Provincial Park and along the eastern shore of Kippan Lake, about 2 miles west from the south-western most corner of White Bear Indian Reserve.” ref

STONES, SOLSTICES, AND SUN DANCE STRUCTURES

“Eleven boulder configurations in Saskatchewan were examined in 1975 for possible astronomical alignments. Three were found to contain alignments to summer solstice phenomena. Ethnographic interviewing failed to discover any tradition of solstice marking in the historic tribes of the Northwestern Plains, but did suggest that the boulder configurations may have been constructed for the private observations of calendar-keeping shamans. Ethnoarchaeological mapping of a 1975 Sun Dance camp revealed that the ceremonial structures were aligned to sunrise, but whether this was deliberate, and if deliberate, traditional, could not be determined.” ref

Medicine Wheels?

“Medicine wheels have been identified in South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, Alberta, and Saskatchewan. The oldest identified medicine wheel is the 5,500-year-old Majorville Cairn in southern Alberta.” ref

“To some indigenous peoples of North America, the medicine wheel is a metaphor for a variety of spiritual concepts. A medicine wheel may also be a stone monument that illustrates this metaphor. Historically, most medicine wheels follow the basic pattern of having a center of stone, and surrounding that is an outer ring of stones with “spokes” (lines of rocks) radiating from the center to the cardinal directions (east, south, west, and north). These stone structures may be called “medicine wheels” by the nation which built them, or more specific terms in that nation’s language.” ref

“Physical medicine wheels made of stone were constructed by several different indigenous peoples in North America, especially the Plains Indians. They are associated with religious ceremonies. As a metaphor, they may be used in healing work or to illustrate other cultural concepts. The medicine wheel has been adopted as a symbol by a number of pan-Indian groups, or other native groups whose ancestors did not traditionally use it as a symbol or structure. It has also been appropriated by non-indigenous people, usually those associated with New Age communities.” ref

“The Royal Alberta Museum (2005) holds that the term “medicine wheel” was first applied to the Big Horn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming, the southernmost archeological wheel still extant. The term “medicine” was not applied because of any healing that was associated with the medicine wheel, but denotes that the sacred site and rock formations were of central importance and attributed with religious, hallowed, and spiritual significance.” ref

“As a metaphor, the concept of the sacred hoop of life, also used by multiple Nations, is sometimes conflated with that of the medicine wheel. A 2007 Indian Country Today article on the history of the modern Hoop Dance defines the dancer’s hoop this way: The hoop is symbolic of “the never-ending circle of life.” It has no beginning and no end. Intentionally erecting massive stone structures as sacred architecture is a well-documented activity of ancient monolithic and megalithic peoples.” ref

“The Royal Alberta Museum posits the possible point of origin, or parallel tradition, to other round structures such as the tipi lodge, stones used as “foundation stones” or “tent-pegs“:

Scattered across the plains of Alberta are tens of thousands of stone structures. Most of these are simple circles of cobble stones which once held down the edges of the famous tipi of thePlains Indians; these are known as “tipi rings.” Others, however, were of a more esoteric nature. Extremely large stone circles – some greater than 12 meters across – may be the remains of specialceremonial dancestructures. A few cobble arrangements form the outlines of human figures, most of them obviously male. Perhaps the most intriguing cobble constructions, however, are the ones known as medicine wheels.” ref

“Stone medicine wheels are sited throughout the northern United States and southern Canada, specifically South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, Alberta and Saskatchewan. The majority of the approximately 70 documented stone structures still extant are in Alberta, Canada. One of the prototypical medicine wheels is in the Bighorn National Forest in Big Horn County, Wyoming. This 75-foot-diameter (23 m) wheel has 28 spokes, and is part of a vast set of old Native American sites that document 7,000 years of their history in that area. Medicine wheels are also found in Ojibwa territory, the common theory is that they were built by the prehistoric ancestors of the Assiniboine people. Larger astronomical and ceremonial petroforms, and Hopewell mound building sites are also found in North America.” ref

“In defining the commonalities among different stone medicine wheels, the Royal Alberta Museum cites the definition given by John Brumley, an archaeologist from Medicine Hat, that a medicine wheel “consists of at least two of the following three traits: (1) a central stone cairn, (2) one or more concentric stone circles, and/or (3) two or more stone lines radiating outward from a central point.” From the air, a medicine wheel often looks like a wagon wheel lying on its side. The wheels can be large, reaching diameters of 75 feet.” ref

“The most common variation between different wheels are the spokes. There is no set number of spokes for a medicine wheel to have although there are usually 28, the same number of days in a lunar cycle. The spokes within each wheel are rarely evenly spaced, or even all the same length. Some medicine wheels will have one particular spoke that is significantly longer than the rest. The spokes may start from the center cairn and go out only to the outer ring, others go past the outer ring, and some spokes start at the outer ring and go out from there.” ref

“Sometimes there is a passageway, or a doorway, in the circles. The outer ring of stones will be broken, and there will be a stone path leading in to the center of the wheel. Some have additional circles around the outside of the wheel, sometimes attached to spokes or the outer ring, and sometimes floating free of the main structure.” ref

“While alignment with the cardinal directions is common, some medicine wheels are also aligned with astronomical phenomena involving the sun, moon, some stars, and some planets in relation to the Earth’s horizon at that location. The wheels are generally considered to be sacred sites, connected in various ways to the builders’ particular culture, lore and ceremonial ways. Other North American indigenous peoples have made somewhat-similar petroforms, turtle-shaped stone piles with the legs, head, and tail pointing out the directions and aligned with astronomical events.” ref

“Stone medicine wheels have been built and used for ceremonies for millennia, and each one has enough unique characteristics and qualities that archaeologists have encountered significant challenges in determining with precision what each one was for; similarly, gauging their commonality of function and meaning has also been problematic.” ref

“One of the older wheels, the Majorville medicine wheel located south of Bassano, Alberta, has been dated at 3200 BCE (5200 years ago) by careful stratification of known artifact types. Like Stonehenge, it had been built up by successive generations who would add new features to the circle. Due to that and its long period of use (with a gap in its use between 3000 and 2000 years ago, archaeologists believe that the function of the medicine wheel changed over time.” ref

“Astronomer John Eddy put forth the suggestions that some of the wheels had astronomical significance, where spokes on a wheel could be pointing to certain stars, as well as sunrise or sunset, at a certain time of the year, suggesting that the wheels were a way to mark certain days of the year. In a paper for the Journal for the History of Astronomy Professor Bradley Schaefer stated that the claimed alignments for three wheels studied, the Bighorn medicine wheel, one at Moose Mountain in southeastern Saskatchewan, and one at Fort Smith, Montana, there was no statistical evidence for stellar alignments.” ref

“The Bighorn Medicine Wheel is the best known of those found on the Northern and Northwestern Plains, and was the first structure of its type to be systematically studied by professional anthropologists and archaeologists. The Bighorn Medicine Wheel is located at an elevation of 9,642 feet on a high, alpine plateau near the crest of the Bighorn Mountains of north central Wyoming, about 30 miles east of Lovell. Native Americans regard the Medicine Wheel as an essential but secondary component of a much larger spiritual landscape composed of the surrounding alpine forests and mountain peaks, including Medicine Mountain.” ref

“The most conspicuous feature of the Medicine Wheel is a circular alignment of limestone boulders that measures about 80 feet in diameter and contains 28 rock “spokes” that radiate from a prominent central cairn. Five smaller stone enclosures are connected to the outer circumference of the wheel. A sixth and westernmost enclosure is located outside the Medicine Wheel but is clearly linked to the central cairn by one of the “spokes.” The enclosures are round, oval, or horseshoe-shaped and closely resemble Northern and Northwestern Plains fasting (vision quest) structures described by early researchers. Though obscured by a century of non-native use by loggers, ranchers, miners, and recreationalists, the surrounding 15,000 acres contain numerous historic and prehistoric sites including tipi rings, lithic scatters, buried archaeological sites, and a system of relict prehistoric Indian trails.” ref

“Archaeologists generally believe that the Medicine Wheel was constructed over a period of several hundred years during the Late Prehistoric Period. Ceramic shards recovered from the eastern half of the Medicine Wheel have been associated with the Shoshone and Crow tribes. Early nineteenth century glass beads were found near the central cairn, and a wood sample from one of the cairns was tentatively dated to 1760 by means of dendrochronological techniques. Hearth charcoal and preserved wood fragments recovered from archaeological sites in the area yielded radiocarbon dates ranging from the modern era to nearly 7,000 years ago.” ref

“Diagnostic artifacts and other archaeological materials found in close association with the Medicine Wheel itself tend to date to the latter half of the Late Prehistoric Period, from about 900 to 1800. Although these diagnostic artifacts and radiocarbon dates fail to decisively explain the construction and use of the Medicine Wheel, the evidence indicates that prehistoric Native Americans used the general area for nearly 7,000 years. Whether this prehistoric occupation was oriented towards ceremonial or spiritual use—with the Medicine Wheel/Medicine Mountain as the central focus—is a speculative issue that archaeological data may not be able to resolve. It is clear, however, that the Medicine Mountain area was known to and used by prehistoric Native Americans long before the Medicine Wheel was constructed.” ref

“Archaeological evidence cannot definitively identify which tribes used the Medicine Wheel. However, in addition to the above-referenced ceramics associated with the Shoshone and Crow, researchers have noted substantial archaeological evidence supporting an extensive Crow presence on the western slopes of the Big Horn Mountains beginning in the late sixteenth century (or possibly earlier) as well as evidence of a substantial Shoshone occupation in the nearby western Big Horn Basin. Horseshoe-shaped enclosures like those found at the Medicine Wheel have been associated with the Crow Indian fasting (vision quest) rituals.” ref

“Based on exhaustive ethnohistorical research, anthropologist Karl Schlesier has suggested that the Bighorn Medicine Wheel, as well as the Moose Mountain wheel in Saskatchewan, may represent tribal boundary markers as well as Cheyenne ritual lodges that predate sun dance ceremonies. Archaeoastronomer John Eddy demonstrated that the Medicine Wheel likely served as an ancient astronomical observatory, noting several important star alignments involving the central and circumferential cairns.” ref

“Along with the ceremonial and/or spiritual prehistoric sites, the Medicine Mountain area contains many contemporary Native American traditional use areas and features, including ceremonial staging areas, plant gathering areas, sweat lodge sites, altars, offering locales, and recent fasting (vision quest) enclosures. Ethnographic evidence demonstrates that the Medicine Wheel and the surrounding landscape is and has been a major ceremonial and traditional use area for many regional Indian tribes, including Arapaho, Bannock, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Crow, Kootenai-Salish, Plains Cree, Shoshone, and Sioux. These tribes generally venerate the Medicine Wheel because it embodies powerful spiritual principles that figure prominently in tribal and family ceremonial traditions.” ref

“Native American oral traditions and ethnohistory are also relevant to the question of the origins and use of the Medicine Wheel. A Crow legend recounts the construction of the Medicine Wheel by Burnt Face, who fasted there in order to heal his disfigurement. According to Blackfeet traditions, Scar Face traveled to the Medicine Wheel in the distant past, where his disfigurement was removed and he was given instructions for building a sweathouse and conducting the sun dance, information, which he carried back to his tribe.” ref

“In the 1910s, the Crow Indian Flat-Dog reported to anthropologist Robert Lowie that the Medicine Wheel was the “Sun’s Lodge,” that many Crow went there to fast, and that the structure was very ancient. When interviewed by George Bird Grinnell in 1921, an elderly Cheyenne Indian named Elk River compared the Medicine Wheel to the Cheyenne sun dance lodge. Anthropologist James Howard cited an ethnohistorical transcription in which John Bull, a Ponca chief, testified the Medicine Wheel “represents a sun dance circle.” ref

“Native American oral traditions also clearly affiliate Medicine Mountain and the Medicine Wheel with several historically prominent Indian chiefs. Plenty Coups was the last hereditary chief of the Mountain Crow tribe, as well as the most prominent Crow statesman during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. According to Crow tribal oral traditions, Plenty Coups fasted at the Medicine Wheel, once with Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce. Chief Joseph is perhaps best known for leading a band of 700 Nez Perce in a desperate, brilliant, and ultimately futile 1877 military campaign to withdraw his tribe to a Canadian sanctuary among the northern Sioux. Chief Joseph twice asked the Crow Chief Spotted Tail to take him to the Wheel to fast and pray—once after he was incarcerated by the military, and later when he became ill with tuberculosis. Chief Washakie, the celebrated head chief of the Eastern Shoshone until his death in 1900, reportedly acquired much of his power at the Medicine Wheel and was sometimes joined in prayer by the Crow.” ref

“To many longtime Euro-American residents of the northern Bighorn Basin, the Medicine Wheel represents a popular area for camping, hunting, fishing, and picnicking. The first documentary reference to the Wheel occurred in 1895, when Paul Francke described his hunting exploits in an article published in Forest and Stream. At the turn of the nineteenth century, miners and loggers exploited the natural resources near the Medicine Wheel, contributing significantly to the local economy. Later, the area served as an important summer range for domestic sheep and cattle. Local residents have always expressed a proprietary interest in the Medicine Wheel. Boy scouts from the nearby town of Lovell built a protective rock wall around the Medicine Wheel sometime in the early 1920s, and prominent local politicians were instrumental in the Wheel’s designation as a National Historic Landmark in 1970. The Landmark documentation was revised in 2011 to include a rapidly expanding body of ethnographic information regarding Native American traditional cultural knowledge of the Medicine Mountain landscape, and the designation was renamed the Medicine Wheel/Medicine Mountain National Historic Landmark. Today, the Medicine Wheel is managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Visiting the site requires a 3-mile round trip walk at more than 9,000-foot elevation. Visitors with impaired mobility are permitted to drive to the Medicine Wheel.” ref

Who built the Great Medicine Wheels?

“The Medicine Wheels in North America were built by the ancient Plains Indians, nomadic tribes including the Sioux (Lakota, Dakota, Nakota), Cheyenne, Crow, Blackfoot, Arapaho, Cree, Shoshoni, Comanche, and Pawnee. Because they followed herds of buffalo and deer, they were typically on the move most of the year. At one time the Plains Indians occupied all of central North America, from the North Saskatchewan River, in Canada, to Texas, and from the valleys of the Mississippi and the Missouri to the foot of the Rockies.” ref

“Since they rarely stayed in one place, they did not need to build permanent structures out of stone. Thus architectural evidence of the ancient plains Indians is almost non-existent. Along with the lack of permanent buildings, they did not have a written language. Their lore was passsed down in stories told through generations. Even though they left no books to guide us, much of their story can be gleaned in their art and artifacts. Many of these objects reflect their fascination and respect for the Sun and sky. They looked at the heavens with wonder and awe just as we continue to do today. It appears these ancient Plains Indians were deeply connected to their environment and their mythology is rich with celestial themes.” ref

“Medicine Wheels vary in age by centuries. The current Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming is thought to be about 200 years old, thus still fairly “new.” However, there is some evidence that the wheel existed for much longer than that, and that the current wheel is only the last example of a wheel at Bighorn. The Moose Mountain wheel in Saskatchewan is thought to be about 2000 years old, thus built around the time of Christ. Moose Mountain is so similar to Bighorn that some believe it was the model for the younger wheel. The oldest wheel known is in Majorville Canada. Archaeologists have set its age at 5000 years, around the time of the Great pyramids of Egypt. There is some evidence that some of the older wheels have been adjusted over the centuries to correct for the shift in alignment of the solstice.” ref

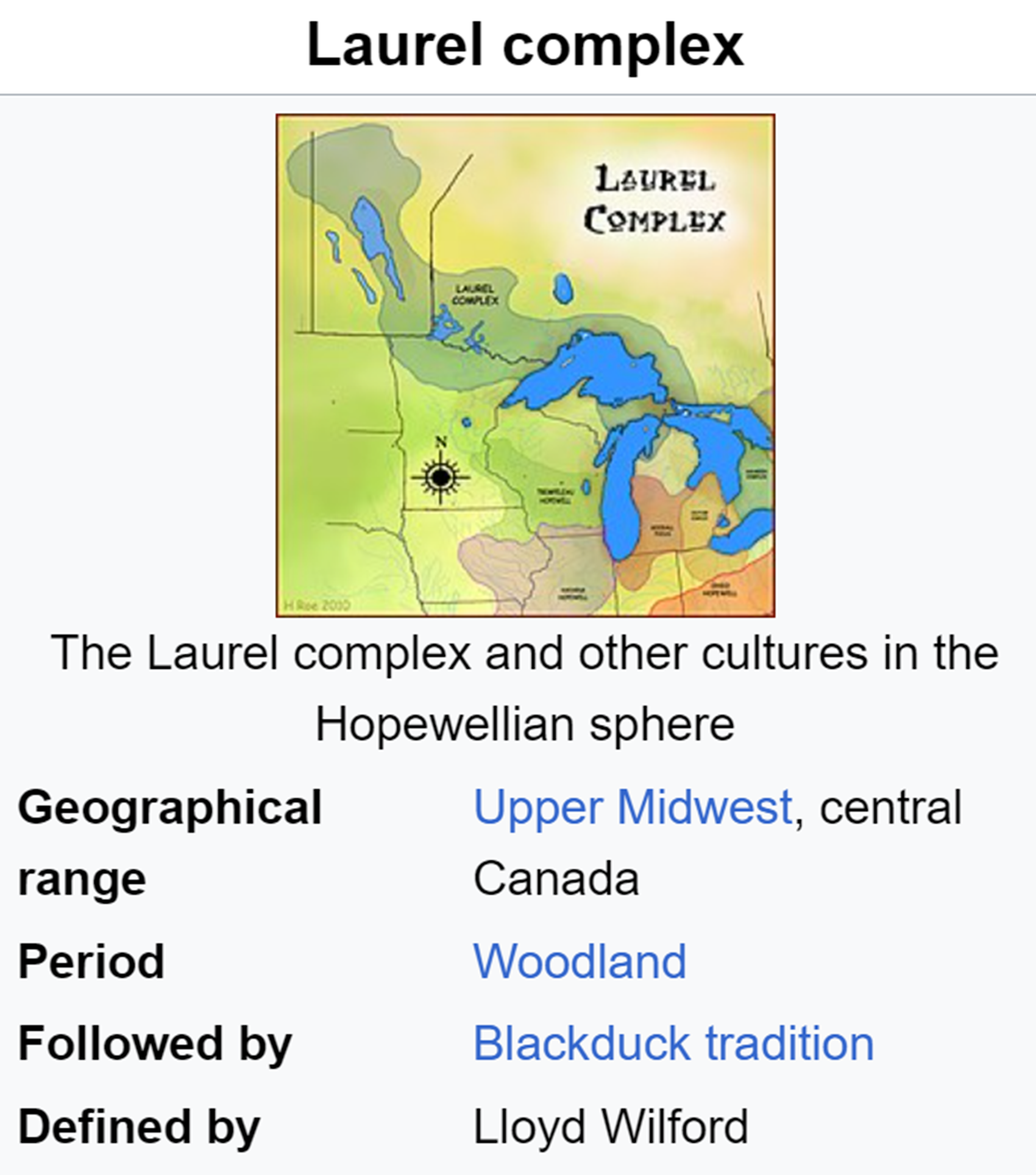

Laurel complex

“The Laurel complex or Laurel tradition is an archaeological culture which was present in what is now southern Quebec, southern and northwestern Ontario, east-central Manitoba in Canada, and northern Michigan, northwestern Wisconsin and northern Minnesota in the United States. They were the first pottery using people of Ontario north of the Trent–Severn Waterway. The complex is named after the former unincorporated community of Laurel, Minnesota. It was first defined by Lloyd Wilford in 1941.” ref

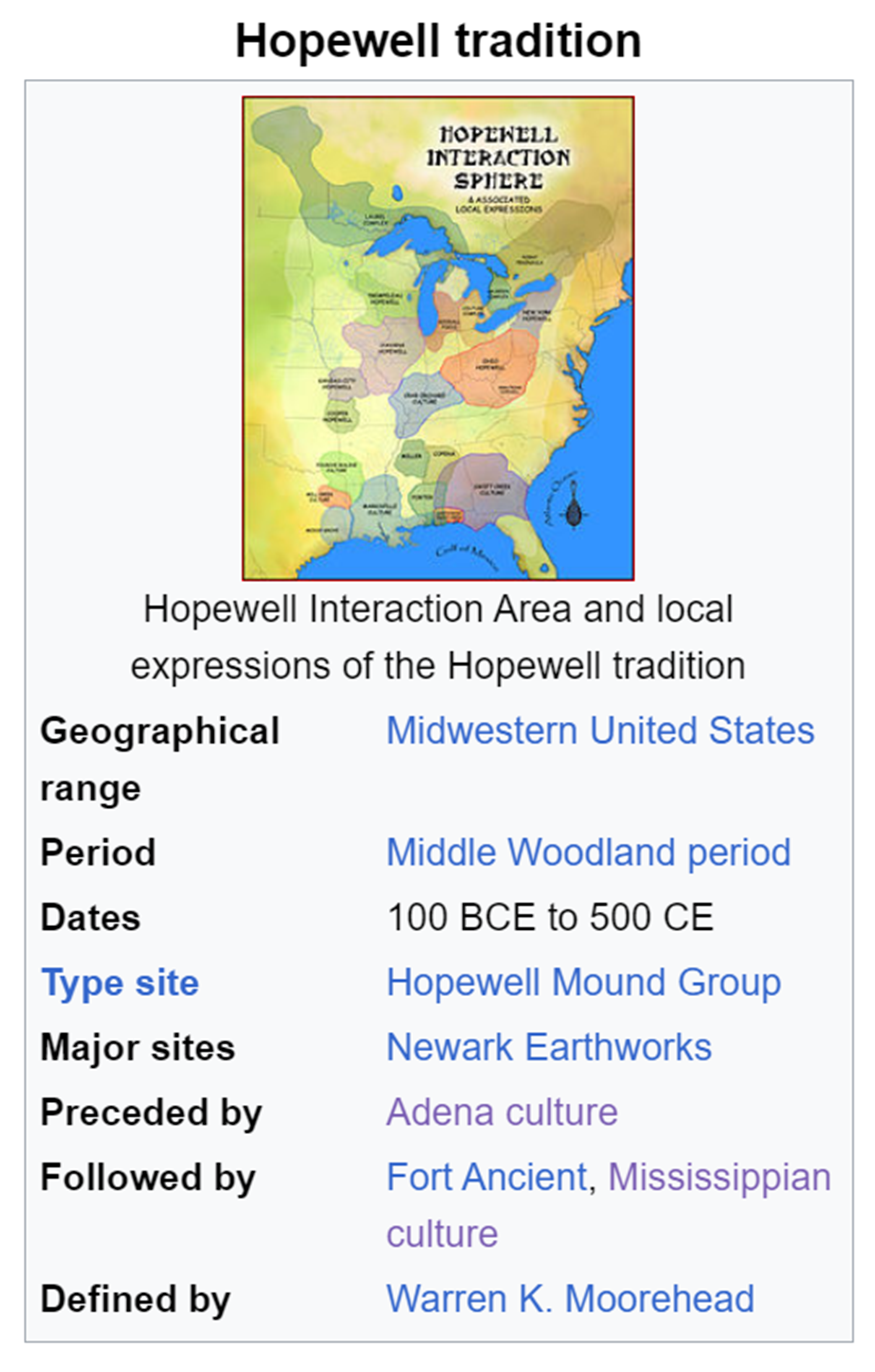

Hopewell Interaction Sphere

“The Hopewell Exchange system began in the Ohio and Illinois River Valleys about 300 BCE. The culture is referred to more as a system of interaction among a variety of societies than as a single society or culture. Hopewell trading networks were quite extensive, with obsidian from the Yellowstone area, copper from Lake Superior, and shells from the Gulf Coast. The construction of ceremonial mounds was an important feature of the Laurel complex, as it was for the Point Peninsula complex and other Hopewell cultures. Sites were usually located at rapids or falls where sturgeon come to spawn, and ceremonies may have coincided with this yearly event. The mounds and the artifacts contained within them indicate contact with the Adena and Hopewell of the Ohio River valley. It is unknown if the contact was direct or indirect.” ref

Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung

“The first mound-builders in what is now the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung National Historic Site of Canada, Laurel culture (c.2300 – 900 years ago) who lived “in villages and built large round burial mounds along the edge of the river, as monuments to their dead.” These mounds remain visible today. Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung is considered to be one of the “most significant centers of early habitation and ceremonial burial in Canada,” is located on the north side Rainy River in Northwestern Ontario, Canada. It became part of a continent-wide trading network because of its strategic location at the center of major North American waterways.” ref

Blackduck tradition

“The later Blackduck tradition has been framed as a successor culture in the region, with the archaeologist K. C. A. Dawson positioning the Blackduck as a new, unrelated population which spread northward through northern Minnesota, southern Manitoba, and northwestern Ontario c. CE 500 to CE 900. Blackduck ceramics were notably better-constructed than Woodland period predecessors, with thinner walls and larger size. It was noted by Dawson that at the Wabinosh River site north of Lake Superior, late Laurel ceramics display some traits of the Blackduck and Selkirk traditions. Dawson associates the Laurel with an Archaic period residual population, with an influx of Blackduck people as the climate in the north became milder; he associates the Blackduck with the Ojibwe.” ref

Saugeen complex

“The Saugeen complex was a First Nations culture located around the southeast shores of Lake Huron and the Bruce Peninsula, around the London area, and possibly as far east as the Grand River. They were active in the period 200 BCE to 500 CE. Archeological evidence suggests that Saugeen complex people of the Bruce Peninsula may have evolved into the Odawa people (Ottawa). In mid-20th century archaeology, the Middle Woodland period in Ontario was conceived of as being divided geographically into three regional complexes: the Couture in the far southwest, the Point Peninsula in south-central and eastern Ontario, and the Saugeen in much of the rest of southwestern Ontario.” ref

“David Marvyn Stothers, who originally conceptualized the Princess Point complex as an archeological culture, argued in a 1973 article that it and the Saugeen were unrelated. However, with continued discoveries and understanding of the period, the idea of distinct, separate complexes has been eroded, especially with the discovery of greater local variability in material culture. Therefore, scholars such as Neal Ferris and Michael Spence have proposed abandonment of the framework altogether, or relegation of the terms to purely geographic use, with their replacement by more localized complexes.” ref

“The Hopewell Exchange system began in the Ohio and Illinois River valleys about 200 BCE. The culture is referred to more as a system of interaction among a variety of societies than as a single society or culture. Hopewell trading networks were quite extensive, and their valued commodities included obsidian from the Yellowstone area, copper from Lake Superior, and shells from the Gulf Coast. The Hopewell tradition was not a single culture or society, but a widely dispersed set of related populations. They were connected by a network of trade routes. known as the Hopewell Exchange System. At its greatest extent, the Hopewell exchange system ran from the Southeastern United States into the southeastern Canadian shores of Lake Ontario. Within this area, societies participated in a high degree of exchange with the highest amount of activity along waterways, the easiest transportation routes.” ref

“The burial customs of the Saugeen people were similar to those of the nearby Point Peninsula complex. The evidence from excavations suggests a band size of about 50 individuals. No indications of status differences have been found in excavations, but no mounds in the Saugeen complex have been excavated. The main distinction between the Saugeen complex and the nearby Point Peninsula complex peoples seems to be that Saugeen ceramics were cruder in construction and decoration.” ref

Point Peninsula complex

“The Point Peninsula complex was an indigenous culture located in Ontario and New York from 600 BCE to 700 CE (during the Middle Woodland period). Point Peninsula ceramics were first introduced into Canada around 600 BCE then spread south into parts of New England around 200 BCE. Some time between 300 BCE and 1 CE, Point Peninsula pottery first appeared in Maine, and “over the entire Maritime Peninsula.” Little evidence exists to show that it was derived from the earlier, thicker pottery, known as Vinette I, Adena Thick, etc… Point Peninsula pottery represented a new kind of technology in North America and has also been called Vinette II. Compared to existing ceramics that were thicker and less decorated, this new pottery has been characterized by “superior modeling of the clay with vessels being thinner, better fired and containing finer grit temper.” Where this new pottery technology originated is not known for sure. The origin of this pottery is “somewhat of a problem.” The people are thought to have been influenced by the Hopewell traditions of the Ohio River valley. This influence seems to have ended about 250 CE, after which they no longer practiced burial ceremonialism.” ref

“The Hopewell exchange system began in the Ohio and Illinois River valleys about 300 BCE. The culture is referred to more as a system of interaction among a variety of societies than as a single society or culture. Hopewell trading networks were quite extensive, with obsidian from the Yellowstone area, copper from Lake Superior, and shells from the Gulf Coast. In some areas Point Peninsula people buried some of their dead in mortuary mounds. Interred with the dead were exotic grave goods, including copper and silver pan pipes, marine shell gorgets, and exotic cherts. The exotic goods among the burials may provide evidence for inherited status differentiation among Point Peninsula groups. Pan pipes, which have been found in burial mounds from Florida to Minnesota, considered to be a diagnostic trait within the Hopewell inventory, appear suddenly in North America around 200 BCE, then disappear as do certain other Hopewell traits, around 400 CE. Found mostly in the United States, nine pan pipes curiously appear in the LeVesconte mound, a Point Peninsula site located in Campbellford, Ontario.” ref

“Though the Hopewell interaction sphere generally is confined to the United States, much of the silver found in mound artifacts, such as pan pipes, actually comes from Cobalt, Ontario, far up the Ottawa River. The Point Peninsula people of the Middle Woodland period lived by hunting and gathering, supplemented by agriculture. Around 900 CE, Point Peninsula artifacts in New York were replaced by Owasco culture artifacts. However, a 2011 paper by archaeologist John P. Hart argues there was no definable Owasco culture. Archaeologists believe these indicated the presence of Clemson Island peoples’ spreading northward and intermingling with the Point Peninsula complex through the years of 1300. The Serpent Mounds Park at Rice Lake was occupied during the prehistoric Middle Woodland period. The burial mound was shaped like a giant snake.” ref

“The Owasco peoples practiced different pottery techniques and were more sedentary agriculturalists than the Point Peninsula people. They cultivated a variety of types of maize, squash, and eventually beans, and lived in larger villages of several hundred to a thousand people. Warfare was prevalent, as is shown by archeology. The people built fortified villages, but many still died violently. Gradually, smaller bands and tribes formed into larger groups. The Owasco are thought to have eventually developed into the several Iroquoian-speaking nations of Pennsylvania and New York. The Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy, likely formed in an effort to avoid the continual warfare of years past. Some important sites are the Rice Lake/Lower Trent River area, including the Serpent Mounds Park, Cameron’s Point, and LeVescounte Mounds in Prince Edward County.” ref

Hopewell

“The Hopewell tradition, also called the Hopewell culture and Hopewellian exchange, describes a network of precontact Native American cultures that flourished in settlements along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern Eastern Woodlands from 100 BCE to 500 CE, in the Middle Woodland period. The Hopewell tradition was not a single culture or society but a widely dispersed set of populations connected by a common network of trade routes. At its greatest extent, the Hopewell exchange system ran from the northern shores of Lake Ontario south to the Crystal River Indian Mounds in modern-day Florida. Within this area, societies exchanged goods and ideas, with the highest amount of activity along waterways, which were the main transportation routes. Peoples within the Hopewell exchange system received materials from all over the territory of what now comprises the mainland United States. Most of the items traded were exotic materials; they were delivered to peoples living in the major trading and manufacturing areas.” ref

“These people converted raw materials into products and exported them through local and regional exchange networks. Hopewell communities traded finished goods, such as steatite platform pipes, far and wide; they have been found among grave goods in many burials outside the Midwest. Although the origins of the Hopewell are still under discussion, the Hopewell culture can also be considered a cultural climax. Hopewell populations originated in western New York and moved south into Ohio, where they built upon the local Adena mortuary tradition. Or, Hopewell was said to have originated in western Illinois and spread by diffusion… to southern Ohio. Similarly, the Havana Hopewell tradition was thought to have spread up the Illinois River and into southwestern Michigan, spawning Goodall Hopewell.” ref

“American archaeologist Warren K. Moorehead popularized the term Hopewell after his 1891 and 1892 explorations of the Hopewell Mound Group in Ross County, Ohio. The mound group was named after Mordecai Hopewell, whose family then owned the property where the earthworks are sited. What any of the various peoples now classified as Hopewellian called themselves is unknown; indeed, what language families they spoke is unknown. Archaeologists applied the term “Hopewell” to a broad range of cultures. Many of the Hopewell communities were temporary settlements of one to three households near rivers. They practiced a mixture of hunting, gathering, and horticulture.” ref

“The Hopewell inherited from their Adena forebears an incipient social stratification. This increased social stability and reinforced sedentism, specialized use of resources, and probably population growth. Hopewell societies cremated most of their deceased and reserved burial for only the most important people. In some sites, hunters apparently were given a higher status in the community: their graves were more elaborate and contained more status goods. The Hopewellian peoples had leaders, but they did not command the kind of centralized power to order armies of slaves or soldiers. These cultures likely accorded certain families a special place of privilege.” ref

“Some scholars suggest that these societies were marked by the emergence of “big-men“, leaders whose influence depended on their skill at persuasion in important matters such as trade and religion. They also perhaps augmented their influence by cultivating reciprocal obligations with other important community members. The emergence of “big-men” was a step toward the development of these societies into highly structured and stratified chiefdoms. The Hopewell settlements were linked by extensive and complex trading routes; these operated also as communication networks, and were a means to bring people together for important ceremonies.” ref

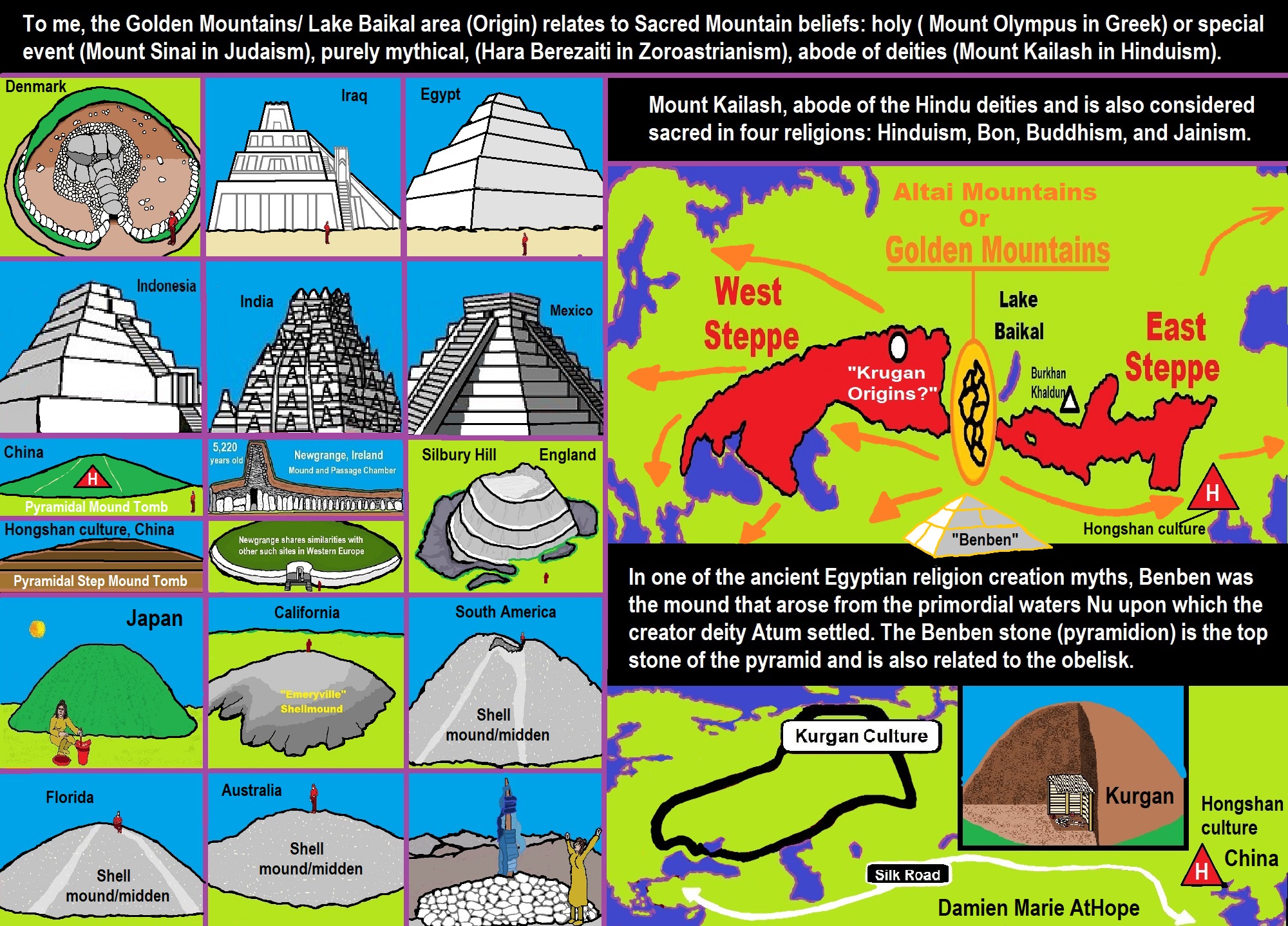

“Today, the best-surviving features of the Hopewell tradition era are earthwork mounds. Researchers have speculated about their purposes, and debate continues. Great geometric earthworks are one of the most impressive Native American monuments throughout American prehistory, and were built by cultures following the Hopewell. Eastern Woodlands mounds typically have various geometric shapes and rise to impressive heights. Some of the gigantic sculpted earthworks, described as effigy mounds, were constructed in the shape of animals, birds, or writhing serpents.” ref

“Several scientists, including Bradley T. Lepper, hypothesize that the Octagon, in the Newark Earthworks at Newark, Ohio, was a lunar observatory. He believes that it is oriented to the 18.6-year cycle of minimum and maximum lunar risings and settings on the local horizon. The Octagon covers more than 50 acres, the size of 100 football pitches. John Eddy completed an unpublished survey in 1978, and proposed a lunar major alignment for the Octagon. Ray Hively and Robert Horn of Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, were the first researchers to analyze numerous lunar sightlines at the Newark Earthworks (1982) and the High Banks Works (1984) in Chillicothe, Ohio.” ref

“Christopher Turner noted that the Fairground Circle in Newark, Ohio aligns to the sunrise on May 4, i.e. that it marks the May cross-quarter sunrise. In 1983, Turner demonstrated that the Hopeton earthworks encode various sunrise and moonrise patterns, including the winter and summer solstices, the equinoxes, the cross-quarter days, the lunar maximum events, and the lunar minimum events, due to their precise straight and parallel lines. William F. Romain has written a book on the subject of “astronomers, geometers, and magicians” at the earthworks. Many of the mounds also contain various types of human burials, some containing precious grave goods such as ornaments of copper, mica and obsidian imported from hundreds of miles away. Stone and ceramics were also fashioned into intricate shapes.” ref

“The Hopewell created some of the finest craftwork and artwork of the Americas. Most of their works had some religious significance, and their graves were filled with necklaces, ornate carvings made from bone or wood, decorated ceremonial pottery, ear plugs, and pendants. Some graves were lined with woven mats, mica (a mineral consisting of thin glassy sheets), or stones. The Hopewell produced artwork in a greater variety and with more exotic materials than their predecessors the Adena. Grizzly bear teeth, fresh water pearls, sea shells, sharks’ teeth, copper, and small quantities of silver were crafted as elegant pieces. The Hopewell artisans were expert carvers of pipestone, and many of the mortuary mounds are full of exquisitely carved statues and pipes.” ref

“Excavation of the Mound of Pipes at Mound City found more than 200 stone smoking pipes; these depicted animals and birds in well-realized three-dimensional form. More than 130 such artifacts were excavated from the Tremper site in Scioto County. Some artwork was made from carved human bones. A rare mask found at Mound City was created using a human skull as a face plate. Hopewell artists created both abstract and realistic portrayals of the human form. One tubular pipe is so accurate in form that the model was identified by researchers as an achondroplastic (chondrodystropic) dwarf. Many other figurines are highly detailed in dress, ornamentation, and hairstyles. An example of the abstract human forms is the “Mica Hand” from the Hopewell Site in Ross County, Ohio. Delicately cut from a piece of mica 11 x 6 in, the hand carving was likely worn or carried for public viewing. They also made beaded work. In addition to the noted Ohio Hopewell, a number of other Middle Woodland period cultures are known to have been involved in the Hopewell tradition and participated in the Hopewell exchange network.” ref

“The Laurel complex was a Native American culture in what is now southern Quebec, southern and northwestern Ontario, and east-central Manitoba in Canada; and northern Michigan, northwestern Wisconsin, and northern Minnesota in the United States. They were the first pottery-using people of Ontario north of the Trent-Severn Waterway. The complex is named after the former unincorporated community of Laurel, Minnesota. And the Point Peninsula complex was a Native American culture located in present-day Ontario, Canada and New York, United States, during the Middle Woodland period. It is thought to have been influenced by the Hopewell traditions of the Ohio River valley. This influence seems to have ended about 250 CE, after which burial ceremonialism was no longer practiced. Also, the Saugeen complex was a Native American culture located around the southeast shores of Lake Huron and the Bruce Peninsula, around the London, Ontario area, and possibly as far east as the Grand River in Canada. Some evidence exists that the Saugeen complex people of the Bruce Peninsula may have evolved into the historic Odawa people, also known as the Ottawa.” ref

Mounds in Canada

“Petroform Site: In Manitoba, a large, nine-acre site exists in the Whiteshell Provincial Park that may be North America’s largest, intact petroform site. It includes human-made boulder outlines, effigies, large carved boulders, stone circles, medicine wheels, and rock art. Medicine wheels and petroforms are also found in Manitoba’s Turtle Mountain Provincial Park.” ref

“Ancient Burial Mounds: In both northern Minnesota and northwestern Ontario, there’s the vast network of ancient burial mounds dating back 2000 years, along the Rainy River west of International Falls (all now registered historic sites in both countries). On the Minnesota side of the river is the Grand Mound, the largest burial mound in the upper U.S. Midwest at 325 feet around and 25 feet high, and the McKinstry Mounds (aka Pelland Mounds). Just across the river on the Canadian north side are the 20-25 sacred Manitou Mounds at the Kay-Nay-Chi-Wah-Nung National Historic Site.” ref

Linear Mounds National Historic Site

“Linear Mounds was designated as a national historic site of Canada in 1973 because the site contains some of the most spectacular and best-preserved examples of mortuary mounds belonging to the Devil’s Lake-Sourisford Burial Complex. Located near the Souris River in southern Manitoba, the Linear Mounds burial site is a sophisticated construction consisting of three mounds spread out over a large area of land. These burial mounds, dating from approximately 900 to about 1400 CE, are complex constructions of soil, bone, and other materials. The excellent state of preservation of these mounds has yielded a wealth of information concerning life in the Great Plains at this time, revealing, by the nature of the goods in the burial mounds, that the peoples of this area were part of a continent-wide trading network.” ref

Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Mounds

“The Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre, or Manitou Mounds, is Canada’s premier concentration of ancient burial mounds. Manitou Mounds National Historic Site, as it was once called, is a vast network of 30 village sites and 15 ancient burial mounds constructed from approximately 5000 years ago during the Archaic Period, to 360 years ago it is one of the “most significant centers of early habitation and ceremonial burial in Canada.” It is located on a river stretch known as Long Sault Rapids on the north side of Rainy River, approximately 54 kilometres (34 mi) east of Fort Frances, in the Rainy River District of Northwestern Ontario, Canada off highway 11. It was designated as a National Historic Site of Canada in 1969.” ref

“The name Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung, is Ojibway and it means “place of the long rapids”. Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung is also known as Manitou Mounds National Historic Site of Canada, GENWAAJIWANAANG, Rainy River Burial Mounds, and Armstrong Mounds. The larger network of mounds extends from Quetico in the east through Rainy River and Lake of the Woods into south-eastern Manitoba. There are approximately 20 archaeological sites. The burial mounds are as tall as 40 feet (12 m). The national historic site of Canada consists of a “500 metres (1,600 ft)-wide strip of lowland stretching 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) along the north bank of the Rainy River in the isolated area midway between Rainy Lake and Lake of the Woods.” ref

“Its strategic location at the centre of major North American waterways, created a vibrant continent-wide trading network. Having direct contact with European fur traders and explorers of the 17th century, Aboriginal people continued to live in the area throughout the period of the fur trade and settlement eras. Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung permitted easy access to, and interaction with, people from other areas of the continent. It came to be known as a gathering place where people would trade, share, celebrate, and mourn. The Ojibway and their ancestors used the prominent sets of rapids along the Rainy River to fish. Because the rapids never froze, fish were in abundance during every season, thus supporting larger populations. — Parks Canada 2013″ ref

“The south-facing hills overlooking the Rainy River served as an ideal location for growing, harvesting and sharing medicinal plants. Specimens were brought by many First Nations peoples when they came there to trade. The site is considered sacred to the Ojibwa, on whose traditional land it is located: This site has deep cultural and spiritual significance to the Ojibway people as a living link in the continuum of past, present and future. Its location at the centre of a major network of North American waterways also means it has significance to First Nations peoples on other parts of the continent. The heritage value of Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung National Historic Site of Canada resides in its historical associations with past and present cultures as symbolized by its strong sense of place, the location and natural features of the site, the presence of its ancient burial mounds and habitation sites, and the site’s function as a living link between those who visited, occupied or used it in the past and the lives of the Ojibway people of today. — NHSC Commemorative Integrity Statement 1998″ ref

“The Rainy River, a relatively wide, straight, and peaceful river (with the exception of the fluvial terraces at Long Sault Rapids), was a major North American waterway. With waterways the most important means of transportation, it served as a superhighway for a vibrant continent-wide trading network for thousands of years. Archaeological artifacts and sites dated at approximately 5,000 years ago, provides evidence that the first residents of the area were nomadic hunters, fishers, and gatherers known as Archaic people. They inhabited many parts of North America and traded extensively over large areas. First Nations consider these traditional lands to have been theirs for time immemorial.” ref

“Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung has the largest concentration of earthwork burial mounds in Canada. The mounds were built on river terraces along the north side of the Long Sault Rapids on Rainy River. The first mound-builders at the site were the Laurel culture (c.2300 – 900 years ago). They lived “in villages and built large round burial mounds along the edge of the river, as monuments to their dead.” Their mounds remain visible today. The Blackduck culture (c.1200 to 400 years ago) also built mounds along the Rainy River. The Blackduck mounds were low and linear.” ref

Interpretive center and museum

“Opened in 1987, the interpretive center showcases 10,000 years of aboriginal history. There is also a reconstructed village and tepee camp. In 1995, Parks Canada provided funds to improve the park, including the construction of the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre and traditional Roundhouse for visitors and the local First Nations communities. Along with a conservation lab and collection storage, the center is also used as a meeting place for Elders. It is an educational resource for teaching Ojibway culture, continuing its role as a gathering place that began thousands of years ago.” ref

“According to the Ontario Museum Association, Inhabited continually for over 5,000 years, this national historic site interprets the pre-history and history of the Ojibway people of the Rainy River. Focusing mainly on the huge burial mounds, this site has an interpretive centre and guided tours. Members of the Rainy River First Nations interpret the site along the 3 km-long trail. Opportunities to learn about Ojibway stories and dance, to participate in a rendezvous, an archaeological dig, or an 1800s living village, are also offered. — Ontario Museum Association 2009″ ref

“The museum with a futuristic design is surrounded by wilderness with resident bear and deer. The Ojibway people of the Rainy River First Nation are the present day guardians of Kay-Nah-Chi-Wan-Nung and have built a world-class historical centre on the beautiful 90-hectare site. The centre has five galleries, a conservation lab with more than 10,000 artifacts in storage, a gift shop (specializing in beautiful Ojibway arts and crafts), a first-class restaurant that serves traditional Ojibway cuisine, and is the gateway to the Manitou Mounds. — Mather Department of Natural Resources Minnesota 2008″ ref

“Treaty 3: With the signing of Treaty no. 3 in 1873 to 1916, this site area was homesteaded by the Rainy Lake First Nations. Evidence of cabins and farm buildings have been found from that time on the site.” ref

MYSTERIOUS ANCIENT MOUNDS IN PRINCE EDWARD COUNTY

“Endless sand dunes, the limitless horizon of the water, and a fascinating history have always made it a wonderful spot for adventure. The ancient burial mounds studied by Thomas Wallbridge in 1860. Acquiring a copy of Wallbridge’s 1860 archeological report on his findings of odd stone “mounds” in “The Canadian Journal Of Industry, Science and Art- 1860″, Wallbridge notes that before the native Iroquois that once roamed the region, there were “traces of a more ancient race”. Wallbridge noted that 100 mounds existed in Prince Edward County, and they occurred in groups of two on the shores of water. Upon excavating one of the mounds Wallbridge discovered a limestone box made up of flat stones, where skeletons were found sitting in an upright position with folded arms.” ref

“The mounds are mostly comprised of stone, metamorphic granite that is not typically found in that area. This means the builders would have had to carry the stones from afar to construct these unexplained mounds. Wallbridge concludes his report by saying “Whatever be the origin of these remains, it is clear that the Massassaga Indians were not the builders of the works which they are entombed, since this tribe, it is well known, buried their dead in wrapped birch bark, and laid them at full length a few inches beneath the surface of the soil,” Wallbridge is perplexed at the whole series of mounds, and insists “the skeletons found in the sitting posture belong to some other and far earlier race.” ref

“Now we must remember that archaeology was still a rather new field of study at the time of Wallbridge, so proper knowledge of former occupation and Indigenous history was naively unknown. But what is most interesting is a more recent study of the mounds that throw a new light on an old mystery. A more recent study of the mounds was done by a fellow by the name of Beauchamp in 1905 and reversed what was thought earlier about the ancient mounds being for burial purposes and was inclined to believe that the burials Wallbridge found were “intrusive” (dug into it later, not the original) and of no “high antiquity.” ref

“An article from 2001 in Ontario Archeology (number 72, 2001) by David A. Robertson suggests that studies have “failed to reach a consensus as to their function.” It was observed that the mounds comprised of “burnt rocks” which indicated they were under the influence of fire and heat. Robertson then details similarities of the PEC mounds to burned rock middens in Texas and in Ireland where they are known as fulachata fiadh (“outdoor” or “wild cooking places”). Similar features can be found in ancient mounds in the Orkneys, and regions of Atlantic Europe. These mounds would almost always be found near marshy areas where a hole dug into the ground would quickly fill with water. These stone enclosures were filled with water and heated stones thrown in to create a pool of boiling water in which meat was cooked, or used for bathing, washing and dyeing of cloth, and leather working. The ancient Irish mounds date from Early Bronze Age (2,300-1,700 BCE) with the majority dating to the second millennium BCE with various explanations as to their use ranging from cooking ovens to wool production.” ref

“Robertson outlines the lack of study of the Prince Edward County mounds, and states:

“It is clear that the Quinte and Perch Lake burnt stone mounds bear close similarities with sites found in Texas and Atlantic Europe and undoubtedly elsewhere: namely the massive quantities of shattered, burnt rock enclosing a small area, the presence of hearths, deposits of ash and charcoal-rich soil, and a general dearth of associated artifacts. Some other parallels with the burnt mounds of Ireland and Britain are even more striking, although these must remain only subjective impressions until further research is devoted..” ref

“Both mound structures are situated in marshy areas, and both have slab-stoned chambers in the center. Robertson also mentions that these ancient mounds could have been used as food processing centers for boiling fats and preserving foods. Mapping out where the mounds may be located, I indeed came across some of the unusual mounds and recorded my findings. They are situated in close proximity to the shore of Lake Ontario, facing east in groups of two with a huge marshy area surrounding the area. The mounds are about 20-ft in diameter and are about 8ft in height. The pair of mounds, with their center points connected with a line, aligned with the rising sun in the east.” ref

“If I were to speculate, these mounds were used for a ceremonial purpose, either for a fire ceremony or a celestial event. Other theories for their use include indigenous sweat lodges, houses, and the commonly accepted burial rituals. Only one thing is certain: no one seems to know exactly what these ancient stone mounds were made for, and until we look into it further, their real purpose and the confirmed identity of their builders may never be known.” ref

“Prince Edward County (PEC) is a county in southern Ontario, Canada. Its coastline on Lake Ontario’s northeastern shore is known for Sandbanks Provincial Park, sand beaches, and limestone cliffs. Settled by indigenous peoples, the county has significant archeological sites. These include the LeVescounte Mounds of the Point Peninsula complex people, built about 2000 years ago.” ref

Mound Culture in North America – in Edmonton, Alberta too?

“Government officials worked to eradicate evidence of pre-contact North American peoples in the late 1800s but they could not erase all their structures, in particular the thousands of man-made mounds that can still be seen today. According to one source, John Wesley Powell, the leader of the first trip down the Grand Canyon – and one-armed to boot – and the Director of the Bureau of Ethnology (U.S.) to 1894, directed archeologists, etc. across the U.S. to send him any evidence they had of pre-Contact peoples. More than 100,000 figurines, sketches of rock drawings, etc. were sent to him and promptly destroyed because as he said there was no culture in the U.S. before Contact with Europe so the evidence could not be true. (This accusation is supported in Henriette Mertz’s book The Mystic Symbol, Mark of the Michigan Mound Builders, p. 203.) But many of the more than 30,000 mounds left behind by these peoples in the Mississippi valley, southern Canada, and the west coast survived these efforts.” ref

“An interesting, although now mostly-erased, mound complex left by this culture was at Marietta, Ohio, where I happen to have spent some of my youth. My paper route was across the street from the town cemetery that had been built around a 10-metre-high mound on a bluff in town. Nearby was the Sacra Via Street ([Sacred Way] Street), named thusly because it is built on a paved road alredy bjuilt before the arrival of the first White pioneers. it is hypothesized that the road had no material purpose, as Natives in the Americas did not have wheeled transport (prior to Contact), so such an established road must have been constructed for a ceremonial procession. One local amateur archaeologist/ anthropologist has worked out a scheme whereby the procession ascended to the mound on the bluff then returned to the (Muskingum) river, crossing and after convulations through various mound constructions ascended the hills across the river from Marietta (in present-day West Virginia). No mounds have yet been found in Alberta although they have been found as nearby as Saskatchewan where Moose Mountain has one of the best-known Prairie ones.” ref

“Pilot Mound, Manitoba is named after one in that area. A Quebecois-born interpreter, Jean L’Heureux, who lived in central Alberta in the 1860s and 1870s, observed that the mound civilization of the Mississippian river valley could have extended as far as Alberta (see “Jean L’Heureux: A Life of Adventure”, Alberta History, Autumn, 2012). The book Canada’s Stonehenge by Gordon R. Freeman discusses possibility of a version of Stonehenge in central Alberta. The recent discovery of what some think is a pyramid in the Balkans, hidden inside what had been assumed to be a mountain, leads me at least to wonder if perhaps Edmonton’s Mount Pleasant or Rabbit Hill or Huntington Hills (south of 51 Avenue west of 104th Street) could be man-made features – mounds.” ref

Manitoba History: The Manitoba Mound Builders: The Making of an Archaeological Myth, 1857-1900

“The first recorded excavation of a Native American mound in Manitoba was undertaken in 1857 by Henry Youle Hind. Hind had left his teaching position at the University of Toronto to serve as a geologist in the Canadian government’s expedition to appraise the territory in the northwest. In the process of exploring potential transportation routes and determining the suitability of land for cultivation, Hind examined a conical mound on the bank of the Souris River. His brief account of the excavation he undertook marks the beginning of what eventually became a nineteenth century fascination with the identity of the mysterious creators of Manitoba’s ancient mounds:

Our half-breeds said it was an old Mandan village; the Indians of that tribe having formerly hunted and lived in this part of the Great Prairies. We endeavoured to make an opening into one of the mounds and penetrated six feet without finding anything to indicate that the mounds were the remains of Mandan lodges.” ref

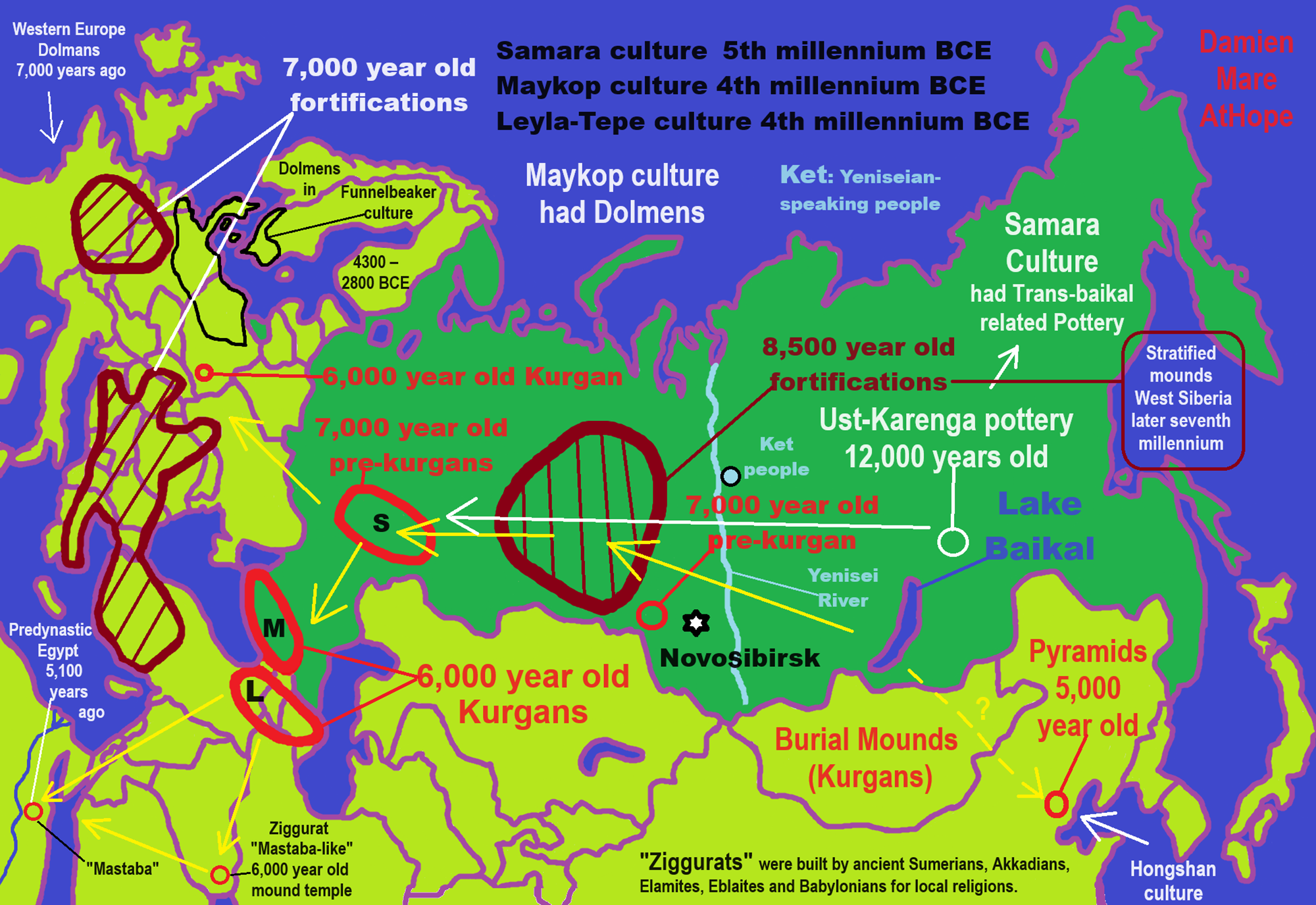

“The mound Hind described in his journal is part of a group of approximately seventy such mounds in the Melita region, and one of over one hundred mounds scattered throughout what is now southern Manitoba. The majority of these mounds have been assigned by modern scholars to two Late Woodland Period archaeological complexes. These complexes, the Blackduck and the Devil’s Lake-Sourisford, flourished in Manitoba between 900 and 1,400 CE. Many of Manitoba’s mounds contain burials, some appear to be animal effigies, still others have no known purpose. Archaeologists point to the remains of small ceremonial fires on the mounds’ burial surfaces, and to the inclusion of foreign materials such as copper and conch shell to support the theory that these ancient earthworks had a ritual meaning for the Aboriginal cultures that constructed them. They speculate that the cooperative labor which mound building entailed provided important ceremonial opportunities to cement relationships between different Native groups in the region.” ref

“Modern scholars agree that Manitoba’s mounds are the product of ancient North American Aboriginal societies. This opinion was not held by their nineteenth-century counterparts. The European Canadian ‘discoverers’ of Manitoba’s mounds interpreted their findings by turning to an existing body of American theory about comparable structures in the United States. American mound scholarship had been stimulated by a series of ancient earthworks located in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys. These structures were remarkable for both their great size and their amazing degree of geometric symmetry. While modern archaeologists attribute these earthworks to the ancient Adena, Hopewell, and Mississippian Aboriginal cultures, their imposing and complex nature led earlier European Americans to reject any connection between the mounds’ creators and the ‘savage Indians’ they had encountered during their westward expansion across the continent. Instead, Americans manufactured a mythical Mound Builder race to resolve the mystery.” ref

“The foundation of the Mound Builder myth rested on the adoption of existing historical, classical, and biblical sources to explain evidence associated with America’s pre-contact past. While a few eighteenth and nineteenth-century American scholars used precursors of modern ethnographical and archaeological methods to argue that the mounds had been built by Native Americans, the majority of early mound enthusiasts preferred to engage in armchair speculation. Their application of European classical scholarship to America’s earthworks produced a variety of bizarre theories. The Mound Builders were presented by various mound enthusiasts as either giants, or white men, or Israelites, or Danes, or Toltecs, or at least in one instance, giant white Jewish Toltec Vikings.” ref

“Although the American Mound Builder myth had made its first appearance in the late eighteenth century, it was not fully endorsed by the American scientific community until 1848. In that year, the recently created Smithsonian Institute published E. G. Squire’s and E. H. Davis’ Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. This publication connected the Mound Builder race with ‘advanced’ pre-conquest civilizations in Peru and Mexico. By 1892, the Smithsonian Institute had revised its initial opinion. A subsequent systematic examination of ancient American mounds resulted in the 1890-1891 Report on the Mound Explorations of the Bureau of Ethnology. This report finally established the builders of the Ohio and Mississippi mounds as the ancestors of America’s contemporary Native peoples.” ref

“The inconclusive nature of the mound excavation undertaken by Henry Youle Hind in 1857 left the door open for further speculation about the creators of Canada’s ancient mounds. It was not, however, until a decade later that the idea of a distinct Mound Builder race was advanced to explain the artificial mounds found in what was then Rupert’s Land. Donald Gunn was responsible for initiating this first step towards a Manitoba Mound Builder myth.” ref

“As an early citizen of the Red River Settlement, Gunn was both a political and intellectual leader within his community. He had been instrumental in agitating against the Hudson’s Bay Company’s monopoly and had been appointed to teach in the Settlement’s parish school. Gunn also regularly contributed meteorological observations and specimens of prairie flora and fauna to the Smithsonian Institute. It was probably through this connection that Gunn had become acquainted with American Mound Builder theories. He may even have had a copy of Squire’s and Davis’ Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley in his extensive collection of natural history books. Certainly, he was aware of the Smithsonian’s interest in ancient earthworks. Consequently, when a burial mound was accidentally discovered near the Red River Settlement in 1867, he excavated it and sent its contents along with a brief report to the Institute.” ref

“Although Gunn referred to the creators of the burial mounds as a red skinned people, he did not believe that the mounds’ builders were related to the area’s current Native populations:

[The] race who reared [the mounds] and whose remains they cover have passed away, or become absorbed in a race of red men; barbarous, possessing less energy and industry; for certainly the present race of red men are in every respect incapable of undergoing the labor necessary to accumulate such heaps of earth.” ref