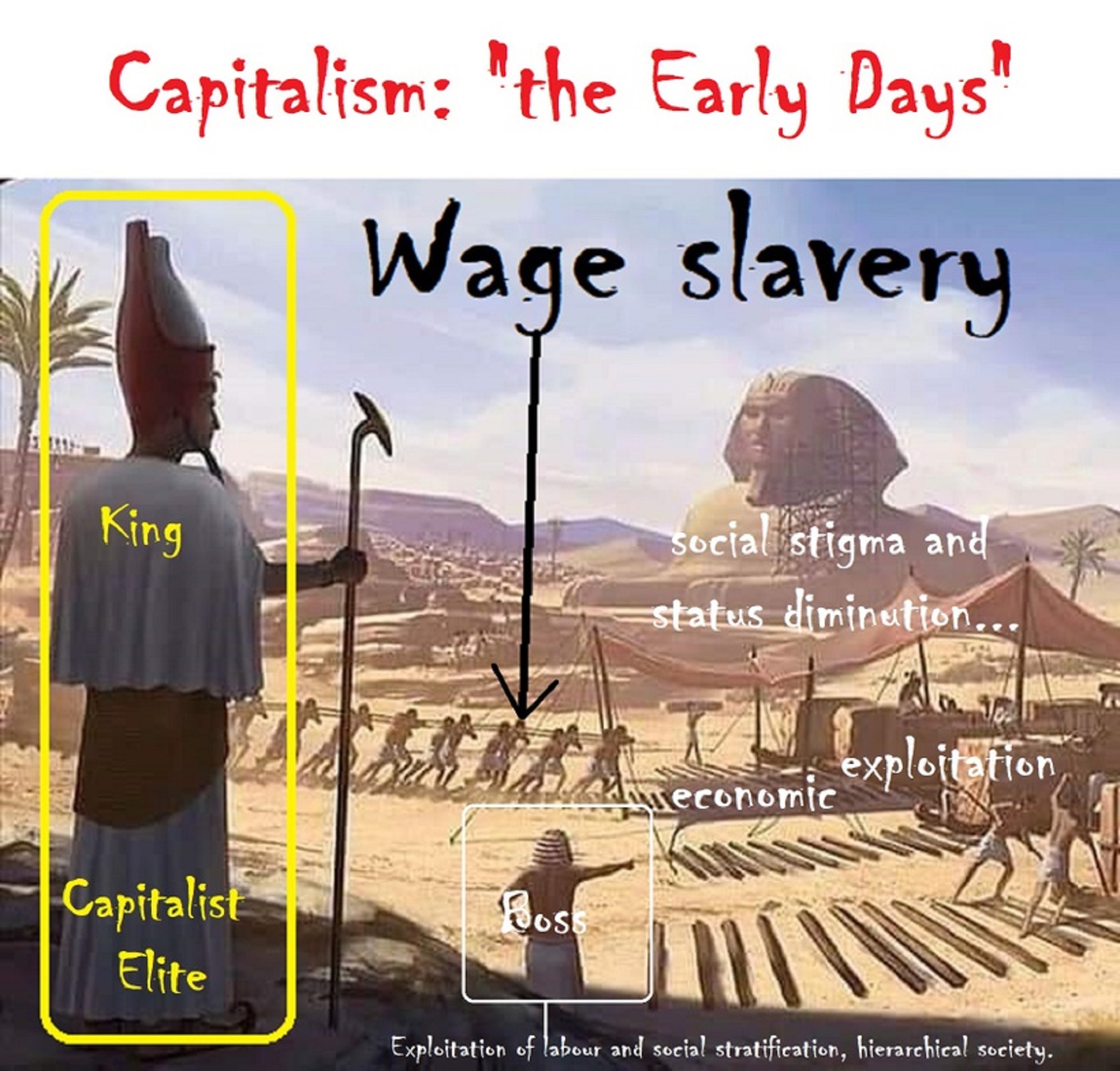

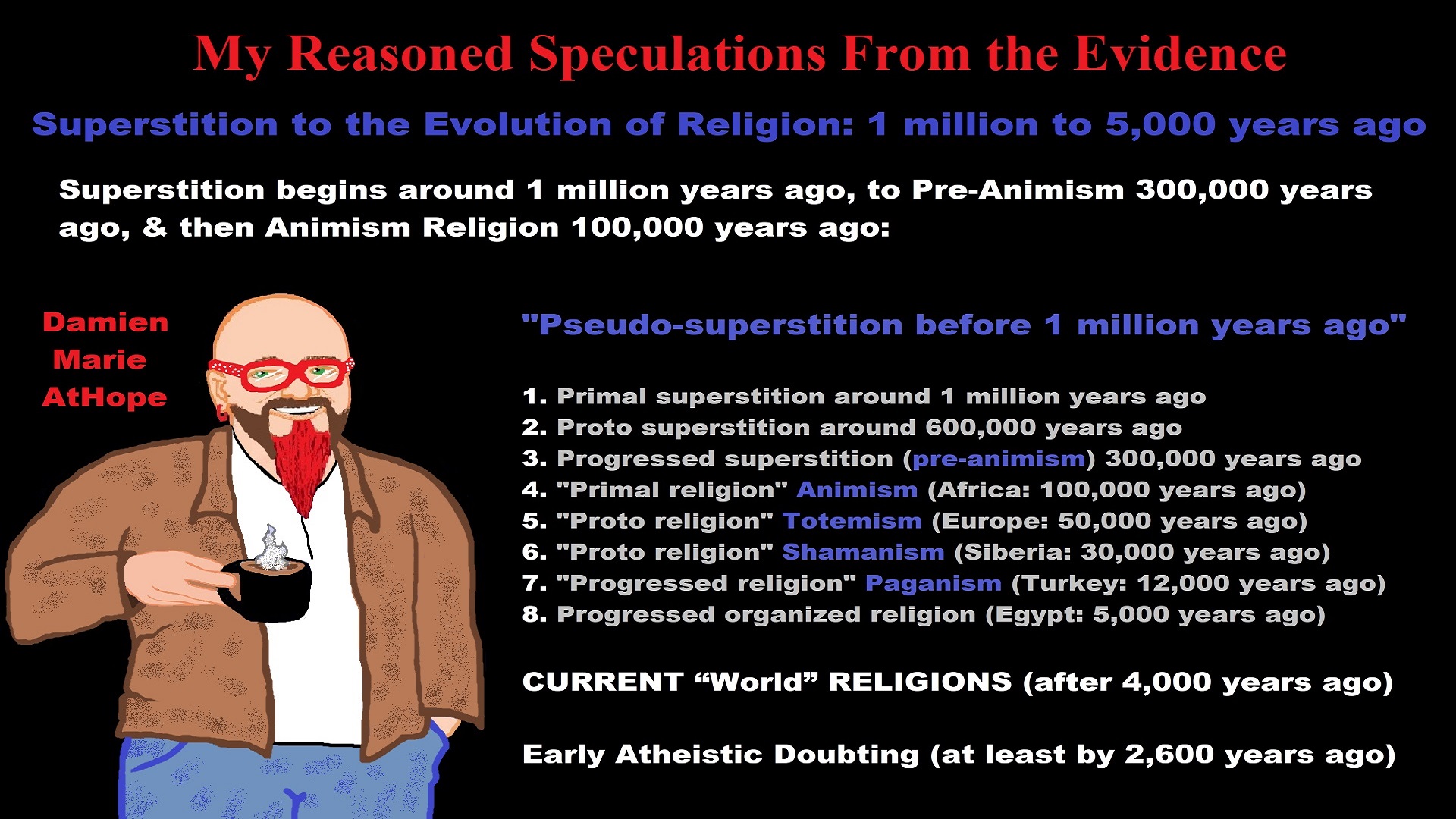

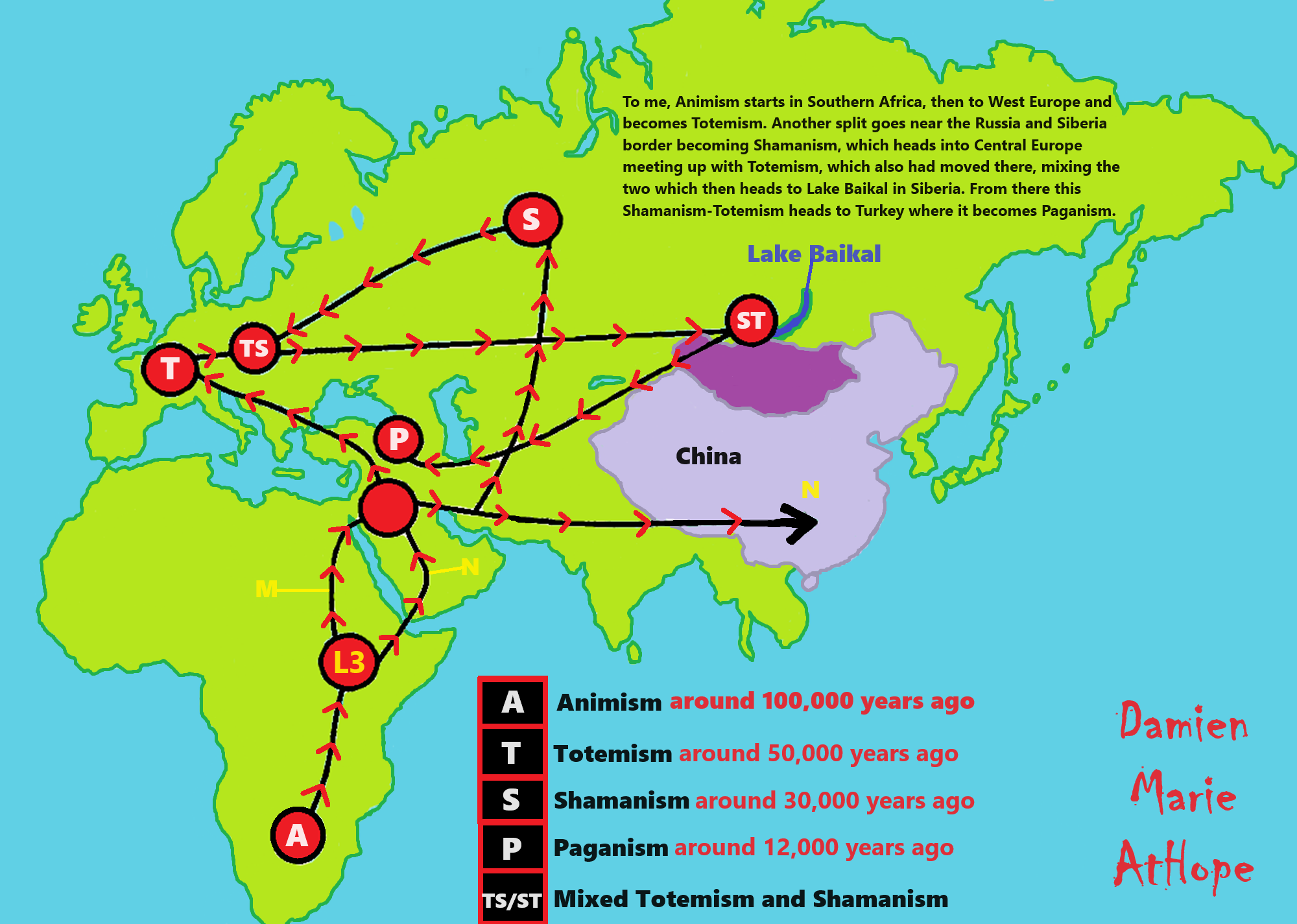

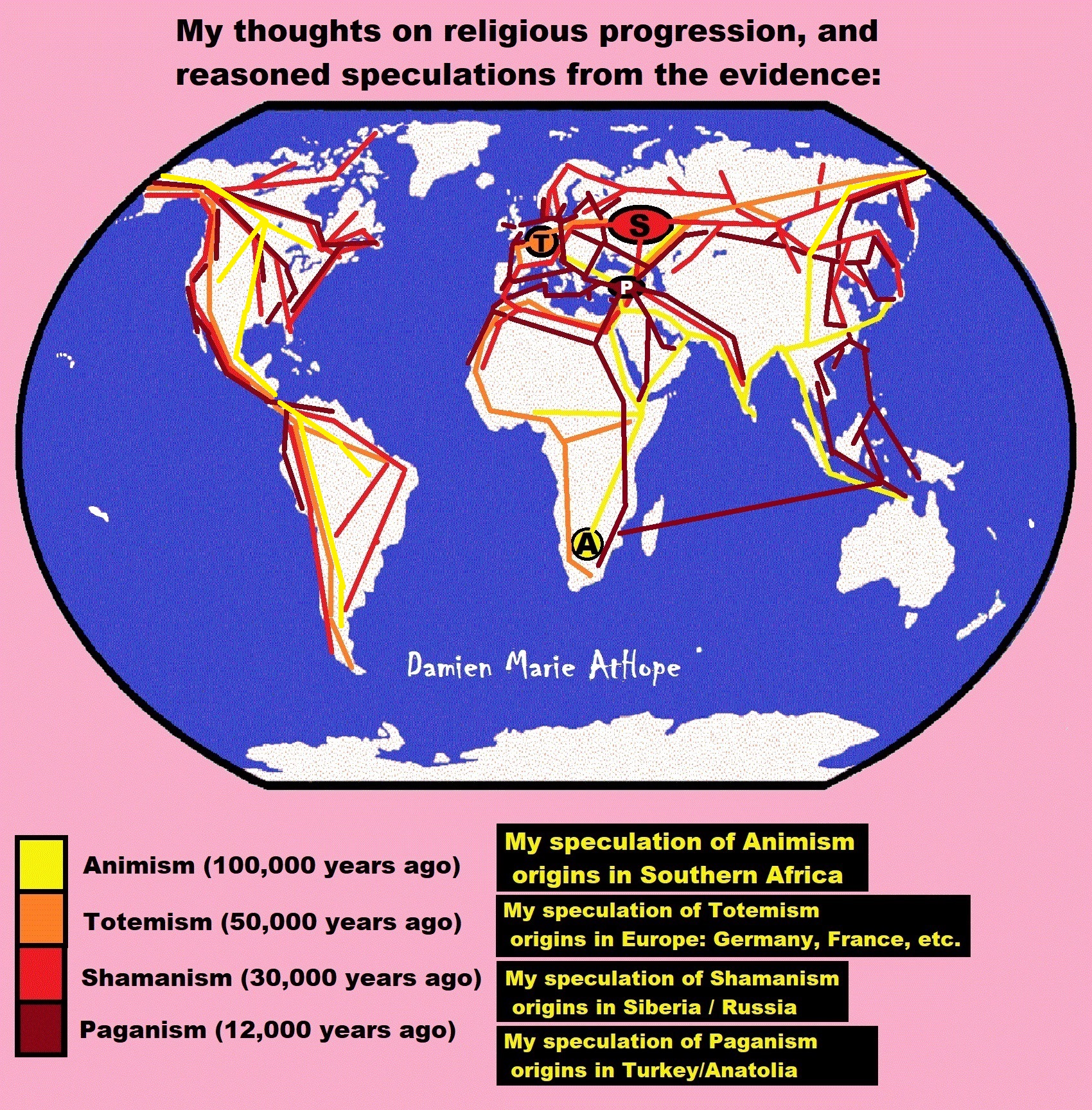

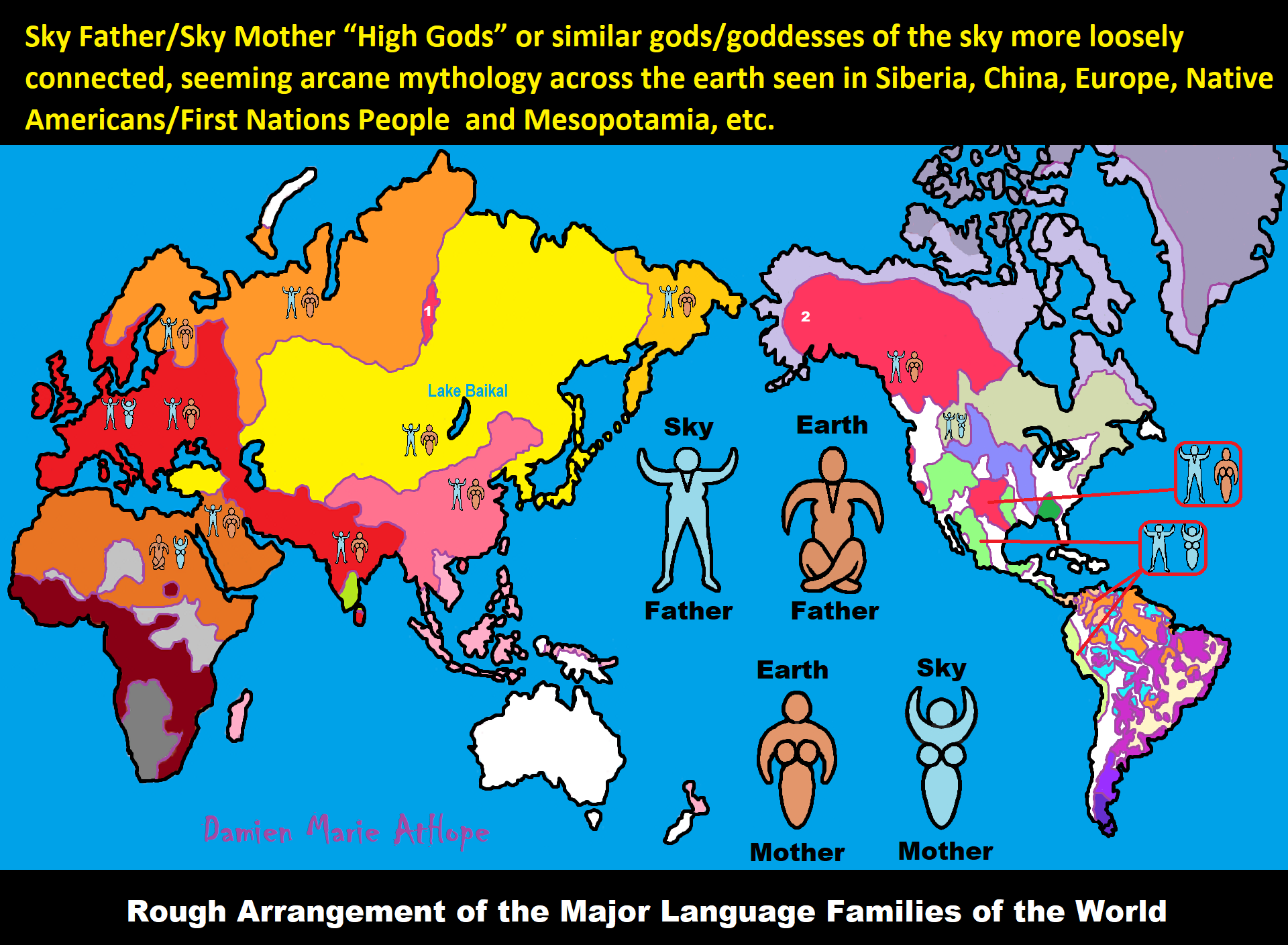

This art above explains my thinking from my life of investigation

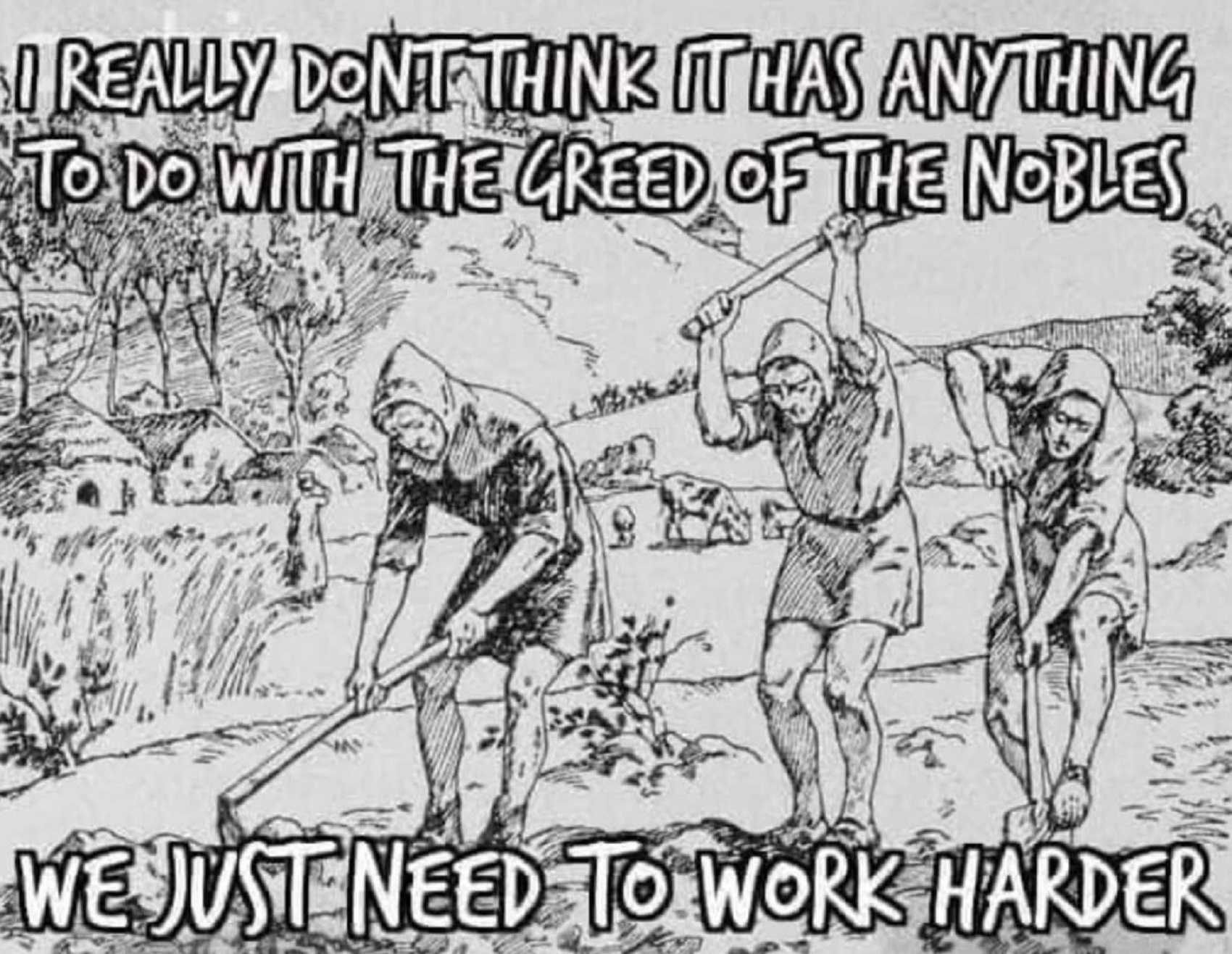

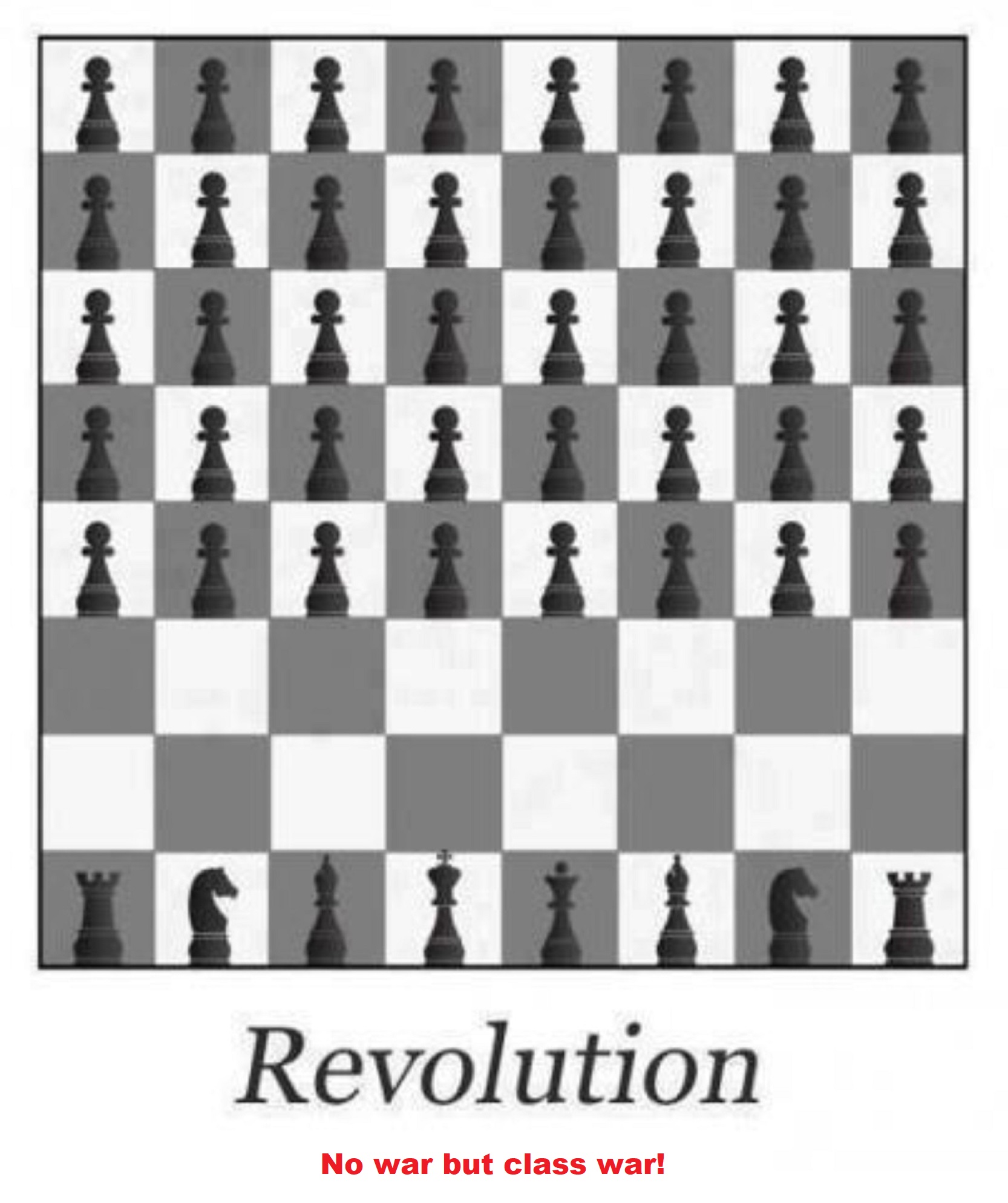

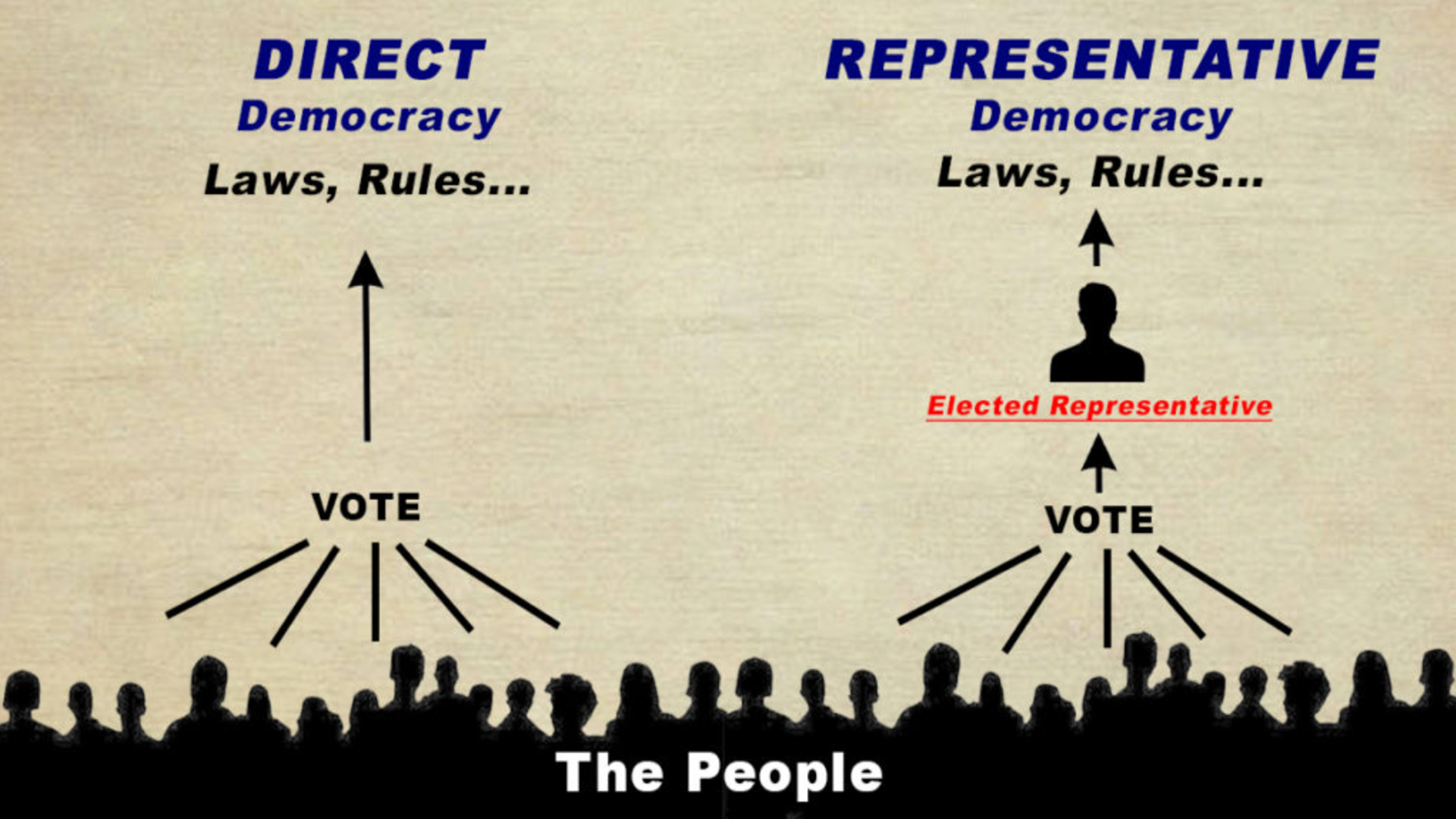

I am an anarchist (Social anarchism, Left-wing anarchism, or Socialist anarchism) trying to explain prehistory as I see it after studying it on my own starting 2006. Anarchists are for truth and believe in teaching the plain truth; misinformation is against this, and we would and should fight misinformation and disinformation.

I see anarchism as a social justice issue not limited to some political issue or monetary persuasion. People own themselves, have self/human rights, and deserve freedoms. All humanity is owed respect for its dignity; we are all born equal in dignity and human rights, and no plot of dirt we currently reside on changes this.

I fully enjoy the value (axiology) of archaeology (empirical evidence from fact or artifacts at a site) is knowledge (epistemology) of the past, adding to our anthropology (evidence from cultures both the present and past) intellectual (rational) assumptions of the likely reality of actual events from time past.

I am an Axiological Atheist, Philosopher & Autodidact Pre-Historical Writer/Researcher, Anti-theist, Anti-religionist, Anarcho Humanist, LGBTQI, Race, & Class equality. I am not an academic, I am a revolutionary sharing education and reason to inspire more deep thinking. I do value and appreciate Academics, Archaeologists, Anthropologists, and Historians as they provide us with great knowledge, informing us about our shared humanity.

I am a servant leader, as I serve the people, not myself, not my ego, and not some desire for money, but rather a caring teacher’s heart to help all I can with all I am. From such thoughtfulness may we all see the need for humanism and secularism, respecting all as helpful servant leaders assisting others as often as we can to navigate truth and the beauty of reality.

‘Reality’ ie. real/external world things, facts/evidence such as that confirmed by science, or events taken as a whole documented understanding of what occurred/is likely to have occurred; the accurate state of affairs. “Reason” is not from a mind devoid of “unreason” but rather demonstrates the potential ability to overcome bad thinking. An honest mind, enjoys just correction. Nothing is a justified true belief without valid or reliable reason and evidence; just as everything believed must be open to question, leaving nothing above challenge.

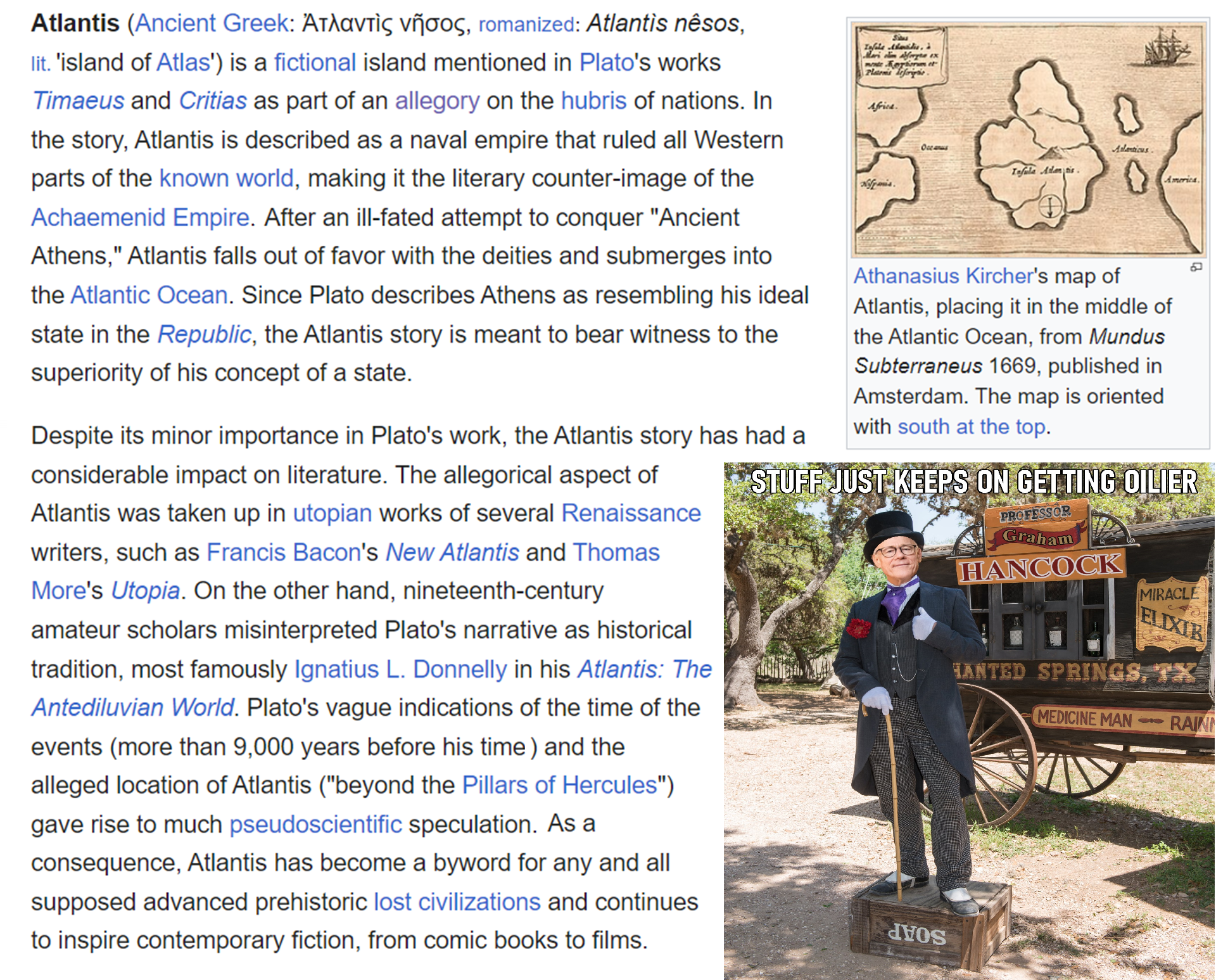

I don’t believe in gods or ghosts, and nor souls either. I don’t believe in heavens or hells, nor any supernatural anything. I don’t believe in Aliens, Bigfoot, nor Atlantis. I strive to follow reason and be a rationalist. Reason is my only master and may we all master reason. Thinking can be random, but reason is organized and sound in its Thinking. Right thinking is reason, right reason is logic, and right logic can be used in math and other scientific methods. I don’t see religious terms Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, or Paganism as primitive but original or core elements that are different parts of world views and their supernatural/non-natural beliefs or thinking.

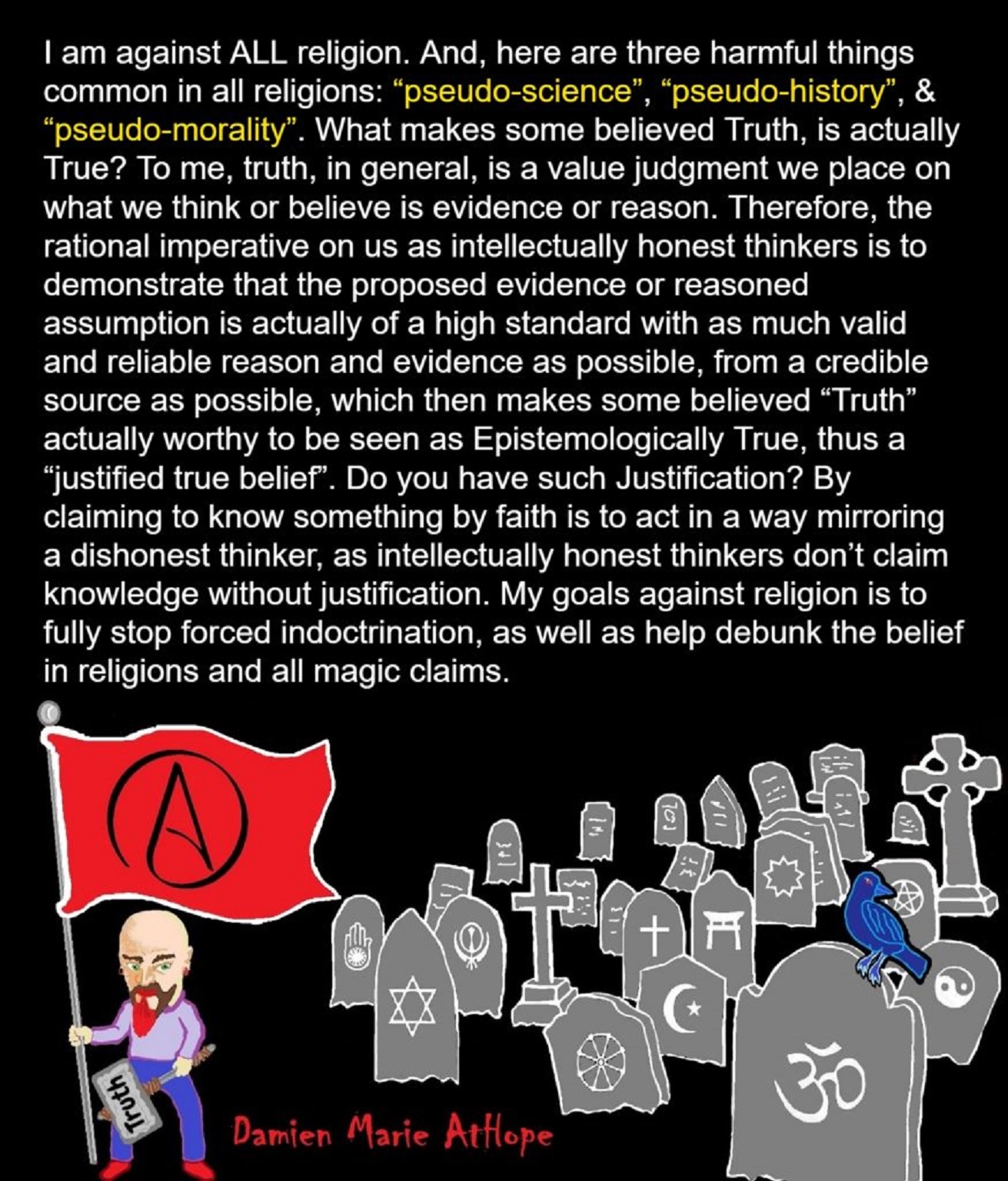

I am inspired by philosophy, enlightened by archaeology, and grounded by science that religion claims, on the whole, along with their magical gods, are but dogmatic propaganda, myths, and lies. To me, religions can be summed up as conspiracy theories about reality, a reality mind you is only natural and devoid of magic anything. And to me, when people talk as if Atlantis is anything real, I stop taking them seriously. Like asking about the reality of Superman or Batman just because they seem to involve metropolitan cities in their stores. Or if Mother Goose actually lived in a shoe? You got to be kidding.

We are made great in our many acts of kindness, because we rise by helping each other.

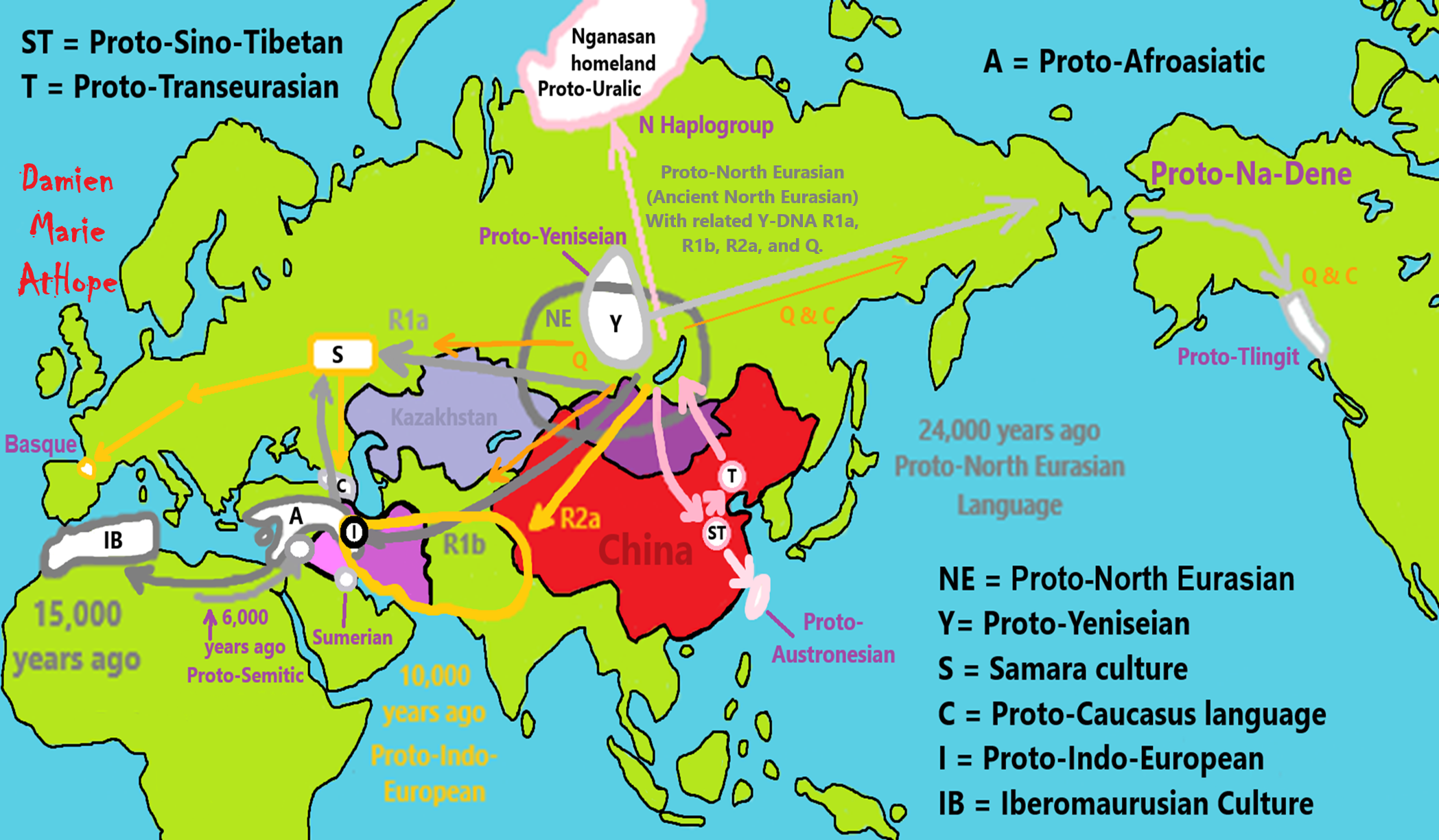

NE = Proto-North Eurasian/Ancient North Eurasian/Mal’ta–Buret’ culture/Mal’ta Boy “MA-1” 24,000 years old burial

A = Proto-Afroasiatic/Afroasiatic

S = Samara culture

ST = Proto-Sino-Tibetan/Sino-Tibetan

T = Proto-Transeurasian/Altaic

C = Proto-Northwest Caucasus language/Northwest Caucasian/Languages of the Caucasus

I = Proto-Indo-European/Indo-European

IB = Iberomaurusian Culture/Capsian culture

Natufian culture (15,000–11,500 years ago, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Negev desert)

Nganasan people/Nganasan language

Na-Dene languages/Dené–Yeniseian, Dené–Caucasian

Proto-Semitic/Semitic languages

24,000 years ago, Proto-North Eurasian Language (Ancient North Eurasian) migrations?

My thoughts:

Proto-North Eurasian Language (Ancient North Eurasian) With related Y-DNA R1a, R1b, R2a, and Q Haplogroups.

R1b 22,0000-15,000 years ago in the Middle east creates Proto-Afroasiatic languages moving into Africa around 15,000-10,000 years ago connecting with the Iberomaurusian Culture/Taforalt near the coasts of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia.

R2a 10,000 years ago in Iran brings/creates Proto-Indo-European language and also a possibility is R1a in Russia around 9,000 years ago may have had a version of Proto-Indo-European language.

Around 14,000-10,000 years ago??? Proto-North Eurasian Language goes to the Yellow River basin (eventually relating with the Yangshao culture) in China creates Proto-Sino-Tibetan language.

Proto-Sino-Tibetan language then moves to the West Liao River valley (eventually relating with the Hongshan culture) in China creating Proto-Transeurasian (Altaic) language around 9,000 years ago.

N Haplogroups 9,000 years ago with Proto-Transeurasian language possibly moves north to Lake Baikal. Then after living with Proto-North Eurasian Language 24,000-9,000 years ago?/Pre-Proto-Yeniseian language 9,000-7,000 years ago Q Haplogroups (eventually relating with the Ket language and the Ket people) until around 5,500 years ago, then N Haplogroups move north to the Taymyr Peninsula in North Siberia (Nganasan homeland) brings/creates the Proto-Uralic language.

Q Haplogroups with Proto-Yeniseian language /Proto-Na-Dene language likely emerge 8,000/7,000 years ago or so and migrates to the Middle East (either following R2a to Iraq or R1a to Russia (Samara culture) then south to Iraq creates the Sumerian language. It may have also created the Proto-Caucasian languages along the way. And Q Haplogroups with Proto-Yeniseian language to a migration to North America that relates to Na-Dené (and maybe including Haida) languages, of which the first branch was Proto-Tlingit language 5,000 years ago, in the Pacific Northwest.

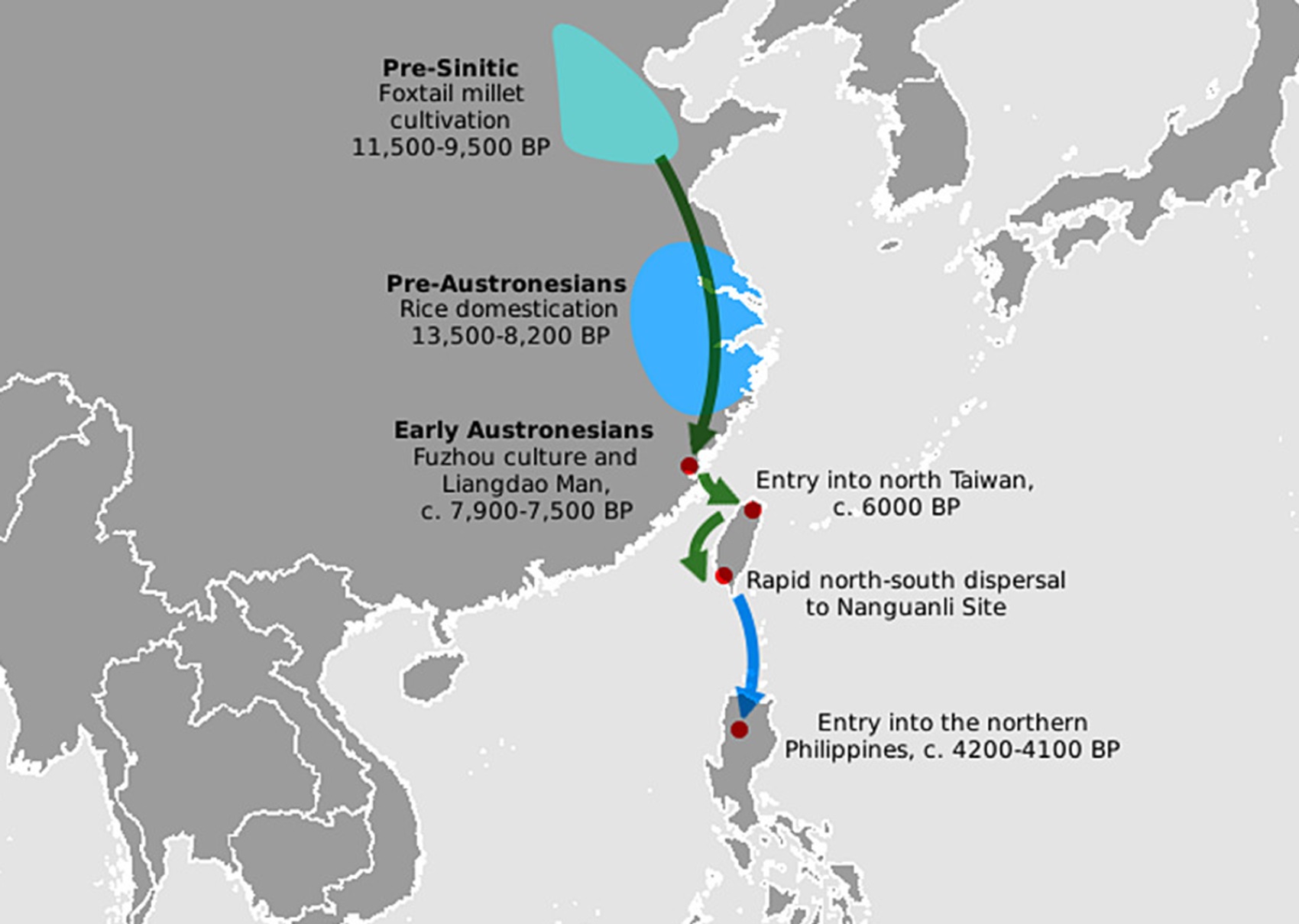

Sino-Tibetan language then moves more east in China to the Hemudu culture pre-Austronesian culture, next moved to Taiwan creating the Proto-Austronesian language around 6,000-5,500 years ago.

R1b comes to Russia from the Middle East around 7,500 years ago, bringing a version of Proto-Indo-European languages to the (Samara culture), then Q Y-DNA with Proto-Yeniseian language moves south from the (Samara culture) and may have been the language that created the Proto-Caucasian language. And R1b from the (Samara culture) becomes the 4,200 years or so R1b associated with the Basques and Basque language it was taken with R1b, but language similarities with the Proto-Caucasian language implies language ties to Proto-Yeniseian language.

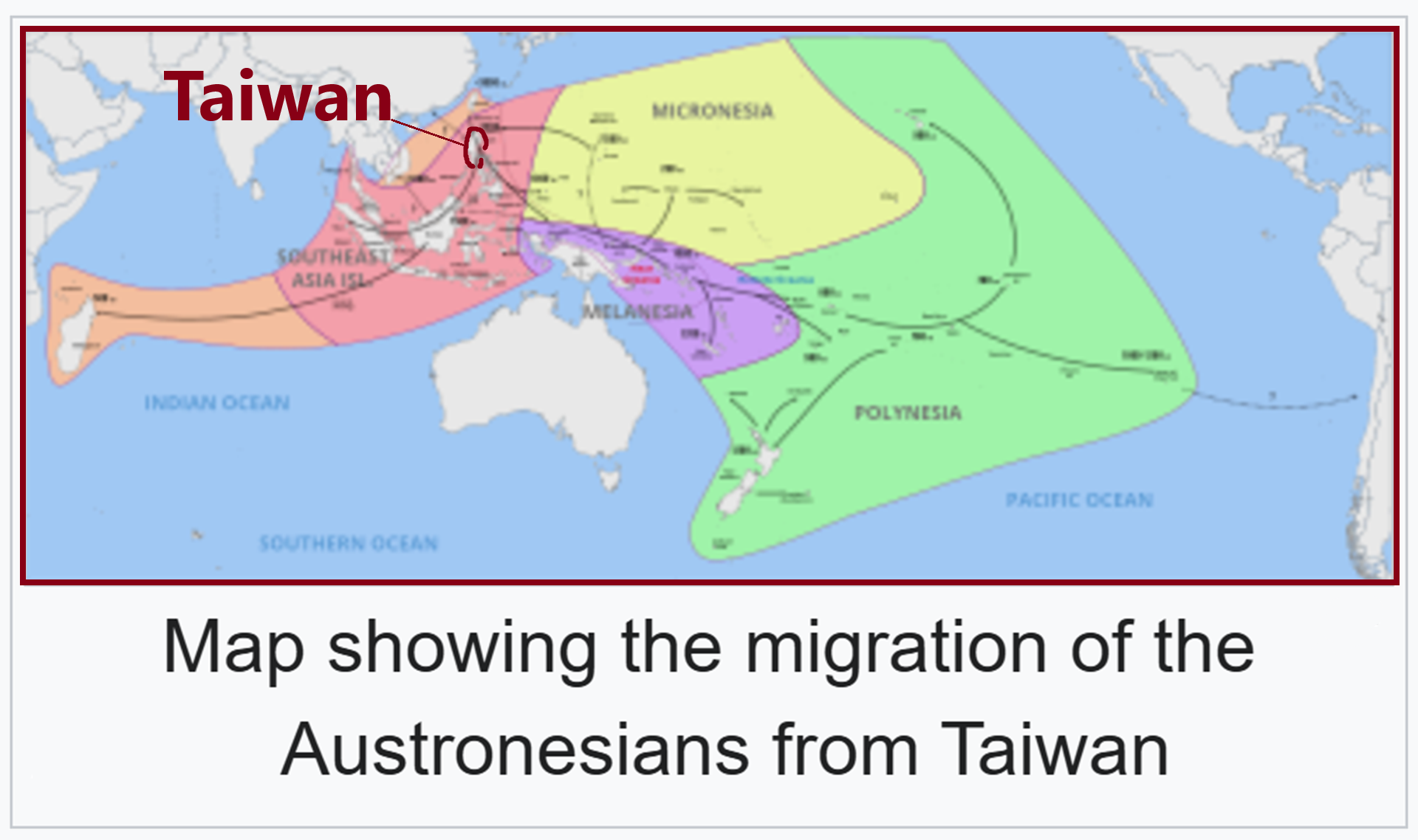

“Austronesians from Taiwan, circa 3000 to 1500 BCE, are now a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, parts of Mainland Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, Madagascar, and then New Zealand by 1250 CE.” ref

Genetic history of East Asians

“The genetic makeup and population history of East Asian peoples and their connection to genetically related populations such as Southeast Asians and North Asians, as well as Oceanians, and partly, Central Asians, South Asians, and Native Americans. They are collectively referred to as “East Eurasians” in population genomics.” ref

“Population genomic research has studied the origin and formation of modern East Asians. The ancestors of East Asians (Ancient East Eurasians) split from other human populations possibly as early as 70,000 to 50,000 years ago. Possible routes into East Asia include a northern route model from Central Asia, beginning north of the Himalayas, and a southern route model, beginning south of the Himalayas and moving through Southeast Asia. Seguin-Orlando et al. (2014) stated that East Asians diverged from West Eurasians, which occurred more than 36, 200 years ago in the Upper Paleolithic. This divergence most likely occurred in the Persian Plateau.” ref

“Phylogenetic data suggests that an early Initial Upper Paleolithic wave (>45,000 years ago) “ascribed to a population movement with uniform genetic features and material culture” (Ancient East Eurasians) used a Southern dispersal route through South Asia, where they subsequently diverged rapidly, and gave rise to Australasians (Oceanians), the Ancient Ancestral South Indians (AASI), as well as Andamanese and East/Southeast Asians, although Papuans may have also received some geneflow from an earlier group (xOoA), around 2%, next to additional archaic admixture in the Sahul region.” ref

“The southern route model for East Asians has been corroborated in multiple recent studies, showing that most of the ancestry of Eastern Asians arrived from the southern route in to Southeast Asia at a very early period, starting perhaps as early as 70,000 years ago, and dispersed northward across Eastern Asia. However, genetic evidence also supports more recent migrations to East Asia from Central Asia and West Eurasia along the northern route, as shown by the presence of haplogroups Q and R, as well as Ancient North Eurasian ancestry. The southern migration wave likely diversified after settling within East Asia, while the northern wave, which probably arrived from the Eurasian steppe, mixed with the southern wave, probably in Siberia.” ref

“A review paper by Melinda A. Yang (in 2022) described the East- and Southeast Asian lineage (ESEA); which is ancestral to modern East Asians, Southeast Asians, Polynesians, and Siberians, originated in Mainland Southeast Asia at c. 50,000 BCE, and expanded through multiple migration waves southwards and northwards, respectively. The ESEA lineage is also ancestral to the “basal Asian” Hoabinhian hunter-gatherers of Southeast Asia and the c. 40,000-year-old Tianyuan lineage found in Northern China, which can already be differentiated from the deeply related Ancestral Ancient South Indians (AASI) and Australasian (AA) lineages.” ref

“There are currently eight detected, closely related, sub-ancestries in the ESEA lineage:

- Amur ancestry (ANA) – Associated with populations in the Amur River region, Mongolia, and Siberia, as well as parts of Central Asia.

- Fujian ancestry – Associated with ancient samples in the Fujian region of Southern China, and modern Austronesian-speaking populations.

- Guangxi ancestry – Associated with a 10,500-year-old individual from Longlin, Guangxi. This ancestry was not observed in either historical samples from Guangxi or contemporary East and Southeast Asians, suggesting that the lineage is extinct in the modern day.

- Jōmon ancestry – Ancestry associated with 8,000–3,000-year-old individuals in the Japanese archipelago.

- Hoabinhian ancestry – Ancestry on the ESEA lineage associated with 8,000–4,000-year-old hunter-gatherers in Laos and Malaysia.

- Tianyuan ancestry – Ancestry on the ESEA lineage associated with an Upper Paleolithic individual dating to 40,000 years ago in northern China.

- Tibetan ancestry – Associated with 3,000-year-old individuals in the Himalayan region of the Tibetan Plateau.

- Yellow River ancestry – Associated with populations in the Yellow River region and common among Sino-Tibetan-speakers.” ref

“The genetic makeup of East Asians is primarily characterized by “Yellow River” (East Asian) ancestry which formed from a major Ancient Northern East Asian (ANEA) component and a minor Ancient Southern East Asian (ASEA) one. The two lineages diverged from each other at least 19,000 years ago, after the divergence of the Jōmon, Guangxi (Longlin), Hoabinhian and Tianyuan lineages.” ref

“Contemporary East Asians (notably Sino-Tibetan speakers) mostly have Yellow River ancestry, which is associated with millet and rice cultivation. “East Asian Highlanders” (Tibetans) carry both Tibetan ancestry and Yellow River ancestry. Japanese people were found to have a tripartite origin; consisting of Jōmon ancestry, Amur ancestry, and Yellow River ancestry. East Asians carry a variation of the MFSD12 gene, which is responsible for lighter skin color. Huang et al. (2021) found evidence for light skin being selected among the ancestral populations of West Eurasians and East Eurasians, prior to their divergence.” ref

“Northeast Asians such as Tungusic, Mongolic, and Turkic peoples derive most of their ancestry from the “Amur” (Ancient Northeast Asian) subgroup of the Ancient Northern East Asians, which expanded massively with millet cultivation and pastoralism. Tungusic peoples display the highest genetic affinity to Ancient Northeast Asians, represented by c. 7,000 and 13,000 year old specimens, whereas Turkic peoples have significant West Eurasian admixture.” ref

“East Asian populations exhibit some European-related admixture, originating from Silk Road traders and interactions with Mongolians, who were well-acquainted with European-like populations. This is more common among northern Han Chinese (2.8%) than southern Han Chinese (1.7%), Japanese (2.2%), and Koreans (1.6%). However, East Asians have less European-related admixture than Northeast Asians like Mongolians (10.9%), Oroqen (9.6%), Daur (8.0%), and Hezhen (6.8%).” ref

A 2020 genetic study about Southeast Asian populations, found that mostly all Southeast Asians are closely related to East Asians and have mostly “East Asian-related” ancestry.” ref

“Ancient remains of hunter-gatherers in Maritime Southeast Asia, such as one Holocene hunter-gatherer from South Sulawesi, had ancestry from both, an Australasian lineage (represented by Papuans and Aboriginal Australasians) and an “Ancient Asian” lineage (represented by East Asians or Andamanese Onge). The hunter-gatherer individual had approximately c. 50% “Basal-East Asian” ancestry and c. 50% Australasian/Papuan ancestry, and was positioned in between modern East Asians and Papuans of Oceania. The authors concluded that East Asian-related ancestry expanded from Mainland Southeast Asia into Maritime Southeast Asia much earlier than previously suggested, as early as 25,000 BCE, long before the expansion of Austroasiatic and Austronesian groups.” ref

“A 2022 genetic study confirmed the close link between East Asians and Southeast Asians, which the authors term “East/Southeast Asian” (ESEA) populations, and also found a low but consistent proportion of South Asian-associated “SAS ancestry” (best samplified by modern Bengalis from Dhaka, Bangladesh) among specific Mainland Southeast Asian (MESA) ethnic groups (~2–16% as inferred by qpAdm), likely as a result of cultural diffision; mainly of South Asian merchants spreading Hinduism and Buddhism among the Indianized kingdoms of Southeast Asia. The authors however caution that Bengali samples harbor detechtable East Asian ancestry, which may affect the estimation of shared haplotypes. Overall, the geneflow event is estimated to have happened between 500 and 1000 years ago.” ref

“The deep population history of East Asia remains poorly understood due to a lack of ancient DNA data and sparse sampling of present-day people. We report genome-wide data from 166 East Asians dating to 6000 BCE – 1000 CE and 46 present-day groups. Hunter-gatherers from Japan, the Amur River Basin, and people of Neolithic and Iron Age Taiwan and the Tibetan plateau are linked by a deeply-splitting lineage likely reflecting a Late Pleistocene coastal migration. We follow Holocene expansions from four regions. First, hunter-gatherers of Mongolia and the Amur River Basin have ancestry shared by Mongolic and Tungusic language speakers but do not carry West Liao River farmer ancestry contradicting theories that their expansion spread these proto-languages.” ref

“Second, Yellow River Basin farmers at ~3000 BCE likely spread Sino-Tibetan languages as their ancestry dispersed both to Tibet where it forms up ~84% to some groups and to the Central Plain where it contributed ~59–84% to Han Chinese. Third, people from Taiwan ~1300 BCE to 800 CE derived ~75% ancestry from a lineage also common in modern Austronesian, Tai-Kadai and Austroasiatic speakers likely deriving from Yangtze River Valley farmers; ancient Taiwan people also derived ~25% ancestry from a northern lineage related to but different from Yellow River farmers implying an additional north-to-south expansion. Fourth, Yamnaya Steppe pastoralist ancestry arrived in western Mongolia after ~3000 BCE but was displaced by previously established lineages even while it persisted in western China as expected if it spread the ancestor of Tocharian Indo-European languages. Two later gene flows affected western Mongolia: after ~2000 BCE migrants with Yamnaya and European farmer ancestry, and episodic impacts of later groups with ancestry from Turan.” ref

“Austronesians mainly carry “Fujian” (Ancient Southern East Asian) ancestry, which is associated with the spread of rice cultivation. Isolated hunter-gatherers in Southeast Asia, specifically in Malaysia and Thailand, such as the Semang, derive most of their ancestry from the Hoabinhian lineage. The emergence of the Neolithic in Southeast Asia went along with a population shift caused by migrations from southern China. Neolithic Mainland Southeast Asian samples predominantly have Ancient Southern East Asian ancestry with Hoabinhian-related admixture. In modern populations, this admixture of Ancient Southern East Asian and Hoabinhian ancestry is most strongly associated with Austroasiatic speakers.” ref

Austronesian Peoples

“The Austronesian peoples, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, parts of Mainland Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar that speak Austronesian languages. They also include indigenous ethnic minorities in Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Hainan, the Comoros, and the Torres Strait Islands. The nations and territories predominantly populated by Austronesian-speaking peoples are sometimes known collectively as Austronesia.” ref

“Austronesian peoples, originated from a prehistoric seaborne migration, known as the Austronesian expansion, from Taiwan, circa 3000 to 1500 BCE. Austronesians reached the northernmost Philippines, specifically the Batanes Islands, by around 2200 BCE. They used sails some time before 2000 BCE. In conjunction with their use of other maritime technologies (notably catamarans, outrigger boats, lashed-lug boats, and the crab claw sail), this enabled phases of rapid dispersal into the islands of the Indo-Pacific, culminating in the settlement of New Zealand c. 1250 CE. During the initial part of the migrations, they encountered and assimilated (or were assimilated by) the Paleolithic populations that had migrated earlier into Maritime Southeast Asia and New Guinea. They reached as far as Easter Island to the east, Madagascar to the west, and New Zealand to the south. At the furthest extent, they might have also reached the Americas.” ref

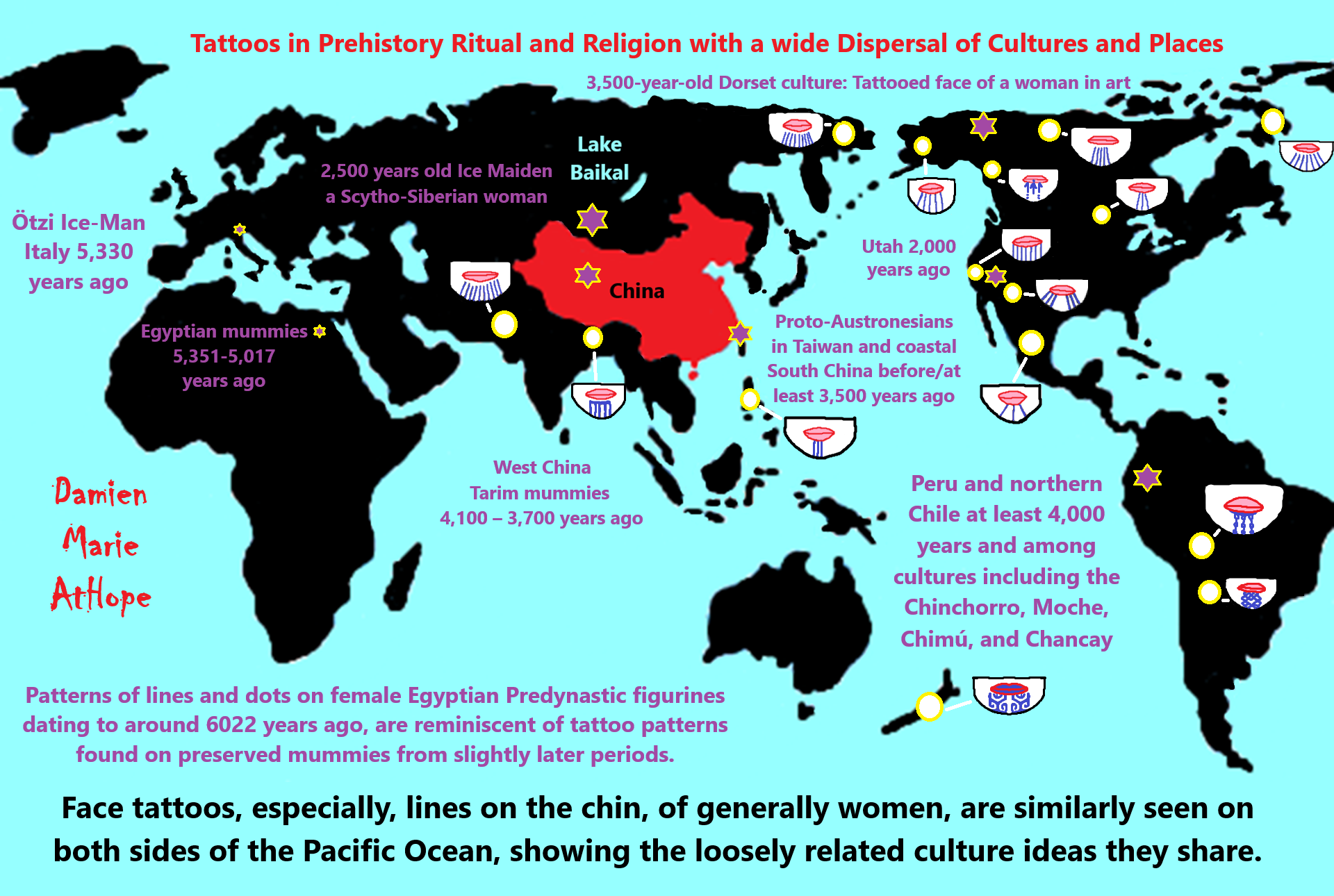

“Aside from language, Austronesian peoples widely share cultural characteristics, including such traditions and traditional technologies as tattooing, stilt houses, jade carving, wetland agriculture, and various rock art motifs. They also share domesticated plants and animals that were carried along with the migrations, including rice, bananas, coconuts, breadfruit, Dioscorea yams, taro, paper mulberry, chickens, pigs, and dogs.” ref

Quantifying the legacy of the Chinese Neolithic on the maternal genetic heritage of Taiwan and Island Southeast Asia

“Abstract: There has been a long-standing debate concerning the extent to which the spread of Neolithic ceramics and Malay-Polynesian languages in Island Southeast Asia (ISEA) were coupled to an agriculturally driven demic dispersal out of Taiwan 4,000 years ago. We previously addressed this question using founder analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) control-region sequences to identify major lineage clusters most likely to have dispersed from Taiwan into ISEA, proposing that the dispersal had a relatively minor impact on the extant genetic structure of ISEA, and that the role of agriculture in the expansion of the Austronesian languages was therefore likely to have been correspondingly minor. Here we test these conclusions by sequencing whole mtDNAs from across Taiwan and ISEA, using their higher chronological precision to resolve the overall proportion that participated in the “out-of-Taiwan” mid-Holocene dispersal as opposed to earlier, postglacial expansions in the Early Holocene. We show that, in total, about 20 % of mtDNA lineages in the modern ISEA pool result from the “out-of-Taiwan” dispersal, with most of the remainder signifying earlier processes, mainly due to sea-level rises after the Last Glacial Maximum. Notably, we show that every one of these founder clusters previously entered Taiwan from China, 6,000–7,000 years ago, where rice-farming originated, and remained distinct from the indigenous Taiwanese population until after the subsequent dispersal into ISEA.” ref

General patterns of migration and expansion in Island Southeast Asia

“For the phylogeographic analysis, we used 870 previously published and 114 newly sequenced mitogenomes belonging to haplogroups R9b, R9c, F1a4, F3, F4b, B4b1, B4c1, B5b, N9, Y and D5. Figure 1 shows an outline topology of the main subclades in East Asia and SEA for these haplogroups, scaled against the ML age estimates. F4b, which entered Taiwan from China at the time of the Neolithic, but does not disperse further into ISEA, is not included. We can group the haplogroups into those with Early Holocene and those with mid-Holocene ancestry in ISEA. The clades B4a1, E1, E2 (the higher-frequency lineages analysed previously, F3b1, R9c1a, B5b1c and B4c1b2a2, corresponding to almost 27 % of all present-day mtDNA lineages in ISEA, most probably expanded within ISEA mainly between 10,000 and 7,000 years ago, many of them reaching Taiwan at some point in the last 8,000 years ago. Haplogroups M7c3c, Y2a1, B4b1a2, F1a4, D5b1c1 and M7b3, amounting to ~20 % overall in ISEA primarily show founder ages that indicate a mid-Holocene, potentially Neolithic entrance into this region, probably from a source in Taiwan (Table 1).” ref

“Southeast Asia (SEA) harbours a rich variety of human populations with contrasting patterns of diversity seen in their ethnic cultures, languages, physical appearance and genetic heritage. The population history of this region was traditionally framed in terms of two distinct major prehistoric population movements. The first settlers, described as “Australo-Melanesian” people, arrived around 50,000–60,000 years ago, and were the ancestors of several “Australoid” populations found in SEA, New Guinea and Australia. The second migration occurred during the mid-Holocene (5–4 ka) and involved a large-scale demic expansion of rice agriculturalists starting in South China ~6 ka, which spread in two directions, one towards Mainland Southeast Asia (MSEA), and the other, via Taiwan, to Island Southeast Asia (ISEA), Near and Remote Oceania, and Madagascar. Proponents of this “two-layer” model, drawn essentially from historical linguistics and some archaeological data, argue that the South Chinese rice agriculturalists partly or largely replaced the previous inhabitants of the region, whilst spreading Austronesian languages in ISEA and Austroasiatic languages in MSEA.” ref

“It is, however, possible that ISEA received direct influence from both of these hypothetical Neolithic migrations, as suggested by Anderson (2005), taking into consideration both archaeological and linguistic evidence. Anderson (2005) offered a more comprehensive view of the Neolithic spread in the region, suggesting that it most likely followed a reticulate pattern, and not a linear expansion model. He proposed the existence of two Neolithic movements from different sources: an earlier minor one ~4,500 years ago from MSEA (“Neolithic I”), related to the spread of Austroasiatic languages and basket or cord-marked ceramics, into the Malay Peninsula and Borneo; and a second, major wave (“Neolithic II”), encompassing the hypothetical “out-of-Taiwan” migration. Our recent genetic work supports this view but emphasizes that both mid-Holocene expansions were due to small-scale migrations.” ref

“Our genetic evidence suggests that other demographic events also contributed to current population structure in SEA, especially as a consequence of the massive climatic changes that occurred at the end of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). In the Late Pleistocene, ~20,000 years ago, global sea levels were ~130 m below present-day levels, MSEA and Western ISEA were interconnected by a vast continental landmass, called Sundaland, that facilitated early human dispersals through the region. After the LGM, rapid episodes of sea-level rises at ~14,500, 11,500 and 7,500 years ago flooded about half of the land area of Sundaland, with a concomitant doubling of the length of the coastline.” ref

“Taking into consideration the past climatic changes in SEA, and the pressure suffered from the flooding of large areas of the landscape, some authors have suggested that these episodes triggered massive migratory events in the region. Thus the dispersals across SEA could have resulted from movement and expansion of indigenous Southeast Asian people, possibly reflected in the increase in sites across ISEA at the end of the Pleistocene. Following this premise, Solheim’s Nusantao Maritime Trading and Communication Network hypothesis (NMTCN) argues that Southeast Asian natives, regardless of language, developed a highly maritime-oriented culture as a result of the changes in the climate and landscape in the region which promoted successful exchange systems between populations in the region for the past 10,000 years ago. The cultural and linguistic similarities could then have been promoted through this wide-ranging trade and communication network.” ref

“Recent technological advances have led to the generation of huge amounts of new genetic data. Maternal, paternal and autosomal genetic markers have all been used to shed light on population migration history but genetic studies on SEA and the Pacific are often still framed within the two-layer model. For example, Friedlaender et al. (2008) suggested that the autosomal variation of Remote Pacific Islanders resulted almost solely from the mid-Holocene expansion of Austronesian-speaking Taiwanese, although their analysis did not include SEA populations. From a slightly different premise, Kayser et al. (2008) also argued that the Polynesian populations have clear maternal Asian ancestry, while Y chromosomes are mostly from New Guinean populations. On this view, Polynesian genetic make-up becomes the result of the intermarriage between Austronesian-speaking females carrying Asian mtDNA lineages (e.g. the mtDNA “Polynesian motif”) with male Melanesians en route to the Pacific.” ref

“However, although the Polynesian motif (defining mtDNA haplogroup B4a1a1) is extremely frequent in the Remote Pacific, with ancestral lineages present equally in ISEA and Taiwanese aboriginals, this need not imply an “Austronesian dispersal”. In fact, the Polynesian motif itself is absent in most of ISEA and not found further west of Wallace’s line, except for southeast Borneo, and it has a coalescence time much greater than expected if it had emerged en route between Taiwan and the Pacific in the mid-Holocene. The molecular-clock evidence (strongly corroborated by archaeologically consistent estimates for the entry into Remote Oceania itself) rather suggests the ancestral lineage reached the Pacific in the Early Holocene, where it evolved into the Polynesian motif ~6,000–7,000 years ago, probably in the Bismarck Archipelago, before expanding both east into the Remote Pacific and west back into ISEA.” ref

“In fact, an increasing number of studies in recent years have indicated that the simple two-layer expansion model does not capture the complexity of the demographic history in ISEA, analysing patterns of Y chromosome variation (Y-SNPs), argued for a discontinuous four-phase colonization process with several population incursions in SEA, starting with the introduction of basal haplogroups with the first settlers, followed by Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene postglacial migrations from the mainland, the mid-Holocene “out-of-Taiwan”, and a more recent migration in the historical era. Significantly, they suggest that only few paternal lineages are associated with the Austronesian dispersal, and that the other major lineages date to earlier population movements.” ref

“These results have been corroborated in other recent. In terms of mtDNA, although studies showed the existence of mtDNA lineages shared between Austronesian speakers of Formosan, Filipino and other ISEA populations, many have contradicted a demic “out-of-Taiwan” expansion due to the time frame. Moreover, some ISEA maternal mtDNA lineages did not trace back their origin to Taiwan, but instead arose within the ISEA region and spread toward Taiwan, probably because of climatic changes. For example, mtDNA haplogroup E underwent major expansions and dispersals in the Early to mid-Holocene, extending west into Malaysia, east into New Guinea and north into Taiwan, somewhere between 8,000 and 4,000 years ago (using the recalibrated mtDNA clock). Thus, Taiwan appears to have been a recipient of haplogroup E lineages from the south, before the Austronesian dispersal, rather than being the major source of Holocene population migrations southwards across ISEA (as in the “out-of-Taiwan” model). Genome-wide analyses have independently supported the notion that Taiwan was, at least in part, the recipient of genetic input from ISEA, rather than the other way around.” ref

“Nevertheless, the genetic picture of SEA remains far from being fully understood. Recently, Soares et al. (2016) performed a founder analysis for ISEA that highlighted three major haplogroups representing the main signals in the analysis; two were postglacial or Early Holocene (haplogroups E and B4a1) and one was a mid-Holocene “out-of-Taiwan” marker (haplogroup M7c3c). Overall, the data, representing 30–40 % of all present-day mtDNA lineages, matched the Early Holocene period, implying that although migrations from Taiwan did occur in the mid- to late Holocene, the so-called Austronesian expansion was mainly a process of cultural diffusion and assimilation. The remaining mtDNA lineages, many displaying low frequencies, cannot be so clearly partitioned using a founder analysis based on HVS-I sequences (first hypervariable segment of the control region). Here, therefore, we analyse in detail the sequence variation of whole-mtDNA genomes (“mitogenomes”) of these low frequency mtDNA lineages.” ref

“These lineages have already been tentatively associated with various demographic events in SEA, including the first settlement (haplogroup F3, R9b), Early Holocene postglacial expansions (haplogroup R9c, N9a) and mid-Holocene dispersals from Taiwan (haplogroups B4c1, F1a4, B5b, Y2, B4b1 and D5), potentially identifying the spread of Neolithic material culture. We previously analysed R9b with whole mtDNAs (Hill et al. 2006), but the subsequent increase in sampling, as well as a revision of the molecular clock demand a reassessment of the phylogeography of the clade. A comprehensive study of these low-frequency haplogroups in Southeast Asia can complete the picture of both the main dispersal routes and the impact of dispersals on the population history in the region. Our study ranges across the vast geographic region of Taiwan, MSEA, ISEA and Near Oceania, in contrast to other recent studies, in which more limited geographic regions were targeted.” ref

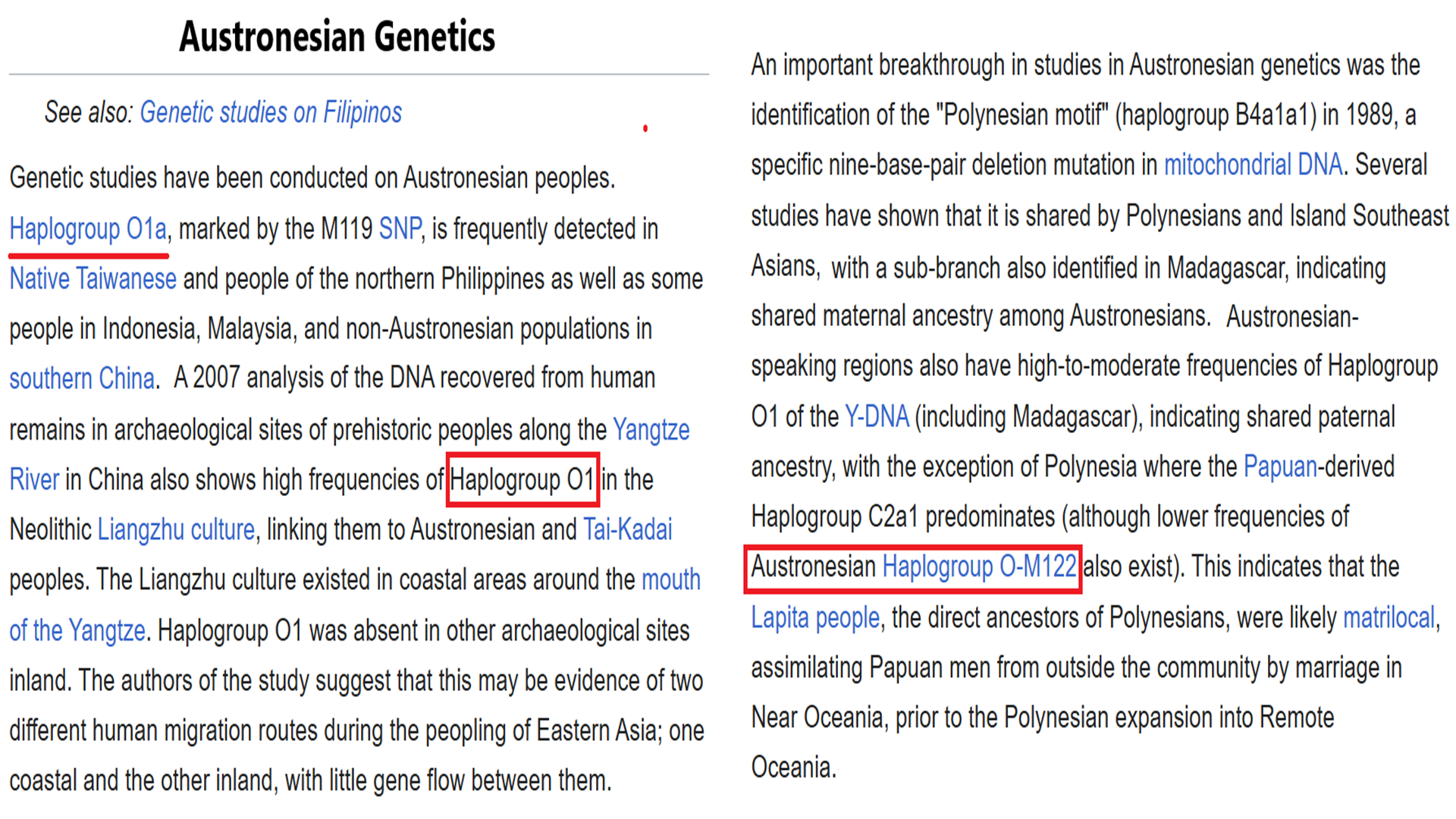

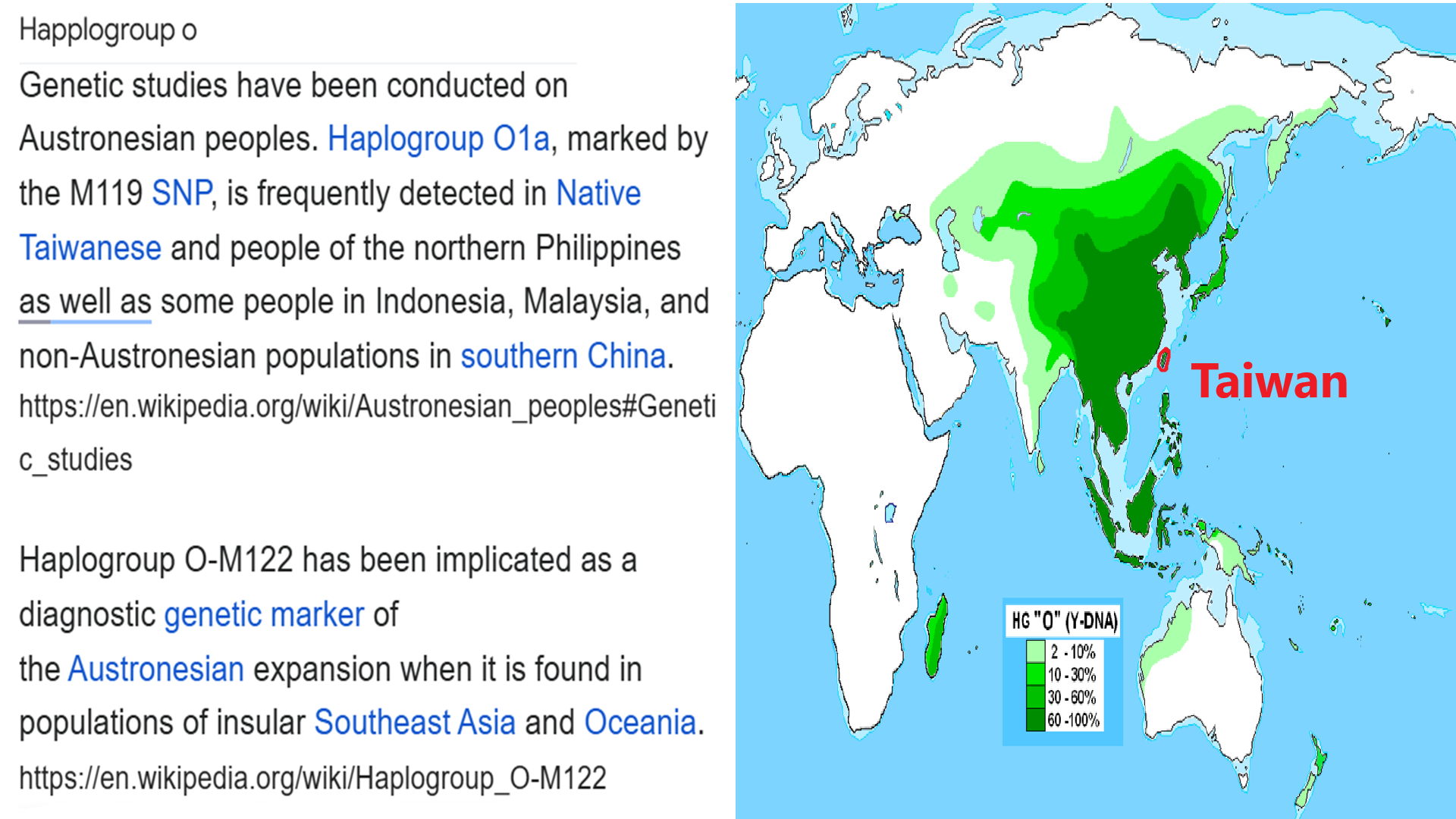

“Genetic studies have been conducted on Austronesian peoples. Haplogroup O1a, marked by the M119 SNP, is frequently detected in Native Taiwanese and people of the northern Philippines as well as some people in Indonesia, Malaysia, and non-Austronesian populations in southern China.” ref

“Haplogroup O-M122 has been implicated as a diagnostic genetic marker of the Austronesian expansion when it is found in populations of insular Southeast Asia and Oceania.” ref

“Haplogroup O mtDNA is a haplogroup derived from haplogroup N and found in Oceania. Specifically, it is found among Aboriginal Australians. Its defining mutations are G6755A, C9140T, and G16213A.” ref

“The genetic ancestry of Polynesians can be traced to both Asia and Melanesia, which presumably reflects admixture occurring between incoming Austronesians and resident non-Austronesians in Melanesia before the subsequent occupation of the greater Pacific; however, the genetic impact of the Austronesian expansion to Melanesia remains largely unknown. We therefore studied the diversity of nonrecombining Y chromosomal (NRY) and mitochondrial (mt) DNA in the Admiralty Islands, located north of mainland Papua New Guinea, and updated our previous data from Asia, Melanesia, and Polynesia with new NRY markers. The Admiralties are occupied today solely by Austronesian-speaking groups, but their human settlement history goes back 20,000 years prior to the arrival of Austronesians about 3,400 years ago. On the Admiralties, we found substantial mtDNA and NRY variation of both Austronesian and non-Austronesian origins, with higher frequencies of Asian mtDNA and Melanesian NRY haplogroups, similar to previous findings in Polynesia and perhaps as a consequence of Austronesian matrilocality.” ref

“Thus, the Austronesian language replacement on the Admiralties (and elsewhere in Island Melanesia and coastal New Guinea) was accompanied by an incomplete genetic replacement that is more associated with mtDNA than with NRY diversity. These results provide further support for the “Slow Boat” model of Polynesian origins, according to which Polynesian ancestors originated from East Asia but genetically mixed with Melanesians before colonizing the Pacific. We also observed that non-Austronesian groups of coastal New Guinea and Island Melanesia had significantly higher frequencies of Asian mtDNA haplogroups than of Asian NRY haplogroups, suggesting sex-biased admixture perhaps as a consequence of non-Austronesian patrilocality. We additionally found that the predominant NRY haplogroup of Asian origin in the Admiralties (O-M110) likely originated in Taiwan, thus providing the first direct Y chromosome evidence for a Taiwanese origin of the Austronesian expansion. Furthermore, we identified a NRY haplogroup (K-P79, also found on the Admiralties) in Polynesians that most likely arose in the Bismarck Archipelago, providing the first direct link between northern Island Melanesia and Polynesia. These results significantly advance our understanding of the impact of the Austronesian expansion and human history in the Pacific region.” ref

“The vast majority (94%) of Polynesian mtDNA types are of East Asian origin (Kayser et al. 2006), and a genetic trail for a particular mtDNA HV1 motif (the Polynesian motif [PM]) that is in high frequency (∼78%) in Polynesians can be traced back along Island Melanesia and coastal New Guinea to Eastern Indonesia, continuing via the immediate precursor HV1 sequence (lacking the transition at 16247) through the Philippines to Taiwan. Surprisingly, most (∼66%) Polynesian Y chromosomes are of Melanesian origin; this large discrepancy between the mtDNA and NRY ancestry of Polynesians led us to propose the “Slow Boat” model of Polynesian origins. According to this model, Austronesians spread from East Asia (perhaps Taiwan), intermixed with people in coastal New Guinea and/or Island Melanesia, and then continued spreading eastward across the western and southern Pacific.” ref

“To explain the discrepancy between the mtDNA and NRY in the ancestry of Polynesians, it was proposed that this intermixing was sex biased, involving primarily the occasional union of an Austronesian woman and a non-Austronesian man, as is typical of matrilocal residence and no other; a position we further affirmed by additional Polynesian data. Recently, this Slow Boat model has received further genetic support from studies of genome-wide autosomal DNA variation in Polynesians, which indicate a primarily East Asian origin of Polynesians but with nonnegligible genetic contributions from Melanesia.” ref

“An important question raised by this scenario is the overall genetic impact of the Austronesian expansion on Melanesia, especially the islands north of mainland New Guinea. We use the term “Austronesian” to refer to the people who brought languages classified as Austronesian into this part of the world, including their current speakers. Northern Island Melanesia represents the area where seafaring, pottery-making people, who most likely spoke an Austronesian language immediately ancestral to Proto-Oceanic, first arrived in Melanesia about 3,400 years ago according to archaeological evidence.” ref

“Because human settlement in this region goes back into the Pleistocene period according to archaeological data, northern Island Melanesia can be assumed as the first regional contact zone for the incoming pre-Proto-Oceanic–speaking Austronesians and the local non-Austronesian inhabitants of Melanesia and presumably reflects the region where the assumed genetic admixture between these 2 groups of people mostly occurred initially. These people then developed in the Bismarcks the characteristic elements of the Lapita cultural complex (most notable highly decorated dentate-stamped pottery), as well as the Proto-Oceanic language. Subsequent voyages distributed Lapita cultural elements further east to Santa Cruz, Reef Island, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Fiji, and eventually into (western) Polynesia within only about 500 years, whereas the Proto-Oceanic language of the voyagers started to diversify into different Oceanic subgroups finally leading to the approximately 450 Oceanic languages known today.” ref

“To investigate the genetic impact of the Austronesian expansion in Melanesia, we analyzed mtDNA and NRY variation in the Admiralty Islands, located north of mainland New Guinea. The “Admiralties” were first colonized by humans from about 21 to 24,000 years ago onward linking them with similarly old and older sites (40,000–50,000 years ago) in mainland New Guinea and other parts of northern Island Melanesia. The human Pleistocene occupation of the Admiralty Islands is quite remarkable as it involved a minimum blind crossing of 60–90 km of open ocean, with no land in sight, in a 200- to 230-km voyage, thus representing one of the few examples of humans crossing water where land was not intervisible prior to the Austronesian expansion across the Pacific. Today, the Admiralties are settled by people speaking 30 different Oceanic languages belonging to the Admiralties subgroup of Oceanic within the Austronesian language family. The presence of at least 1 (perhaps 3) Lapita site on the Admiralty Islands together with a distribution of obsidian tools from Lou Island to regions outside the Admiralties such as to New Britain, the Solomons and as far as Vanuatu from the Lapita period onward suggests that the Admiralties could have played an important role during the Austronesian expansion.” ref

“Thus, the Admiralty Islands were already inhabited for about 20,000 years before the Austronesians arrived there. Did the Austronesian newcomers completely replace the local non-Austronesian inhabitants, or can one find either linguistic or genetic traces of these first inhabitants in contemporary Admiralty Islanders? The complete lack of knowledge on the extinct non-Austronesian languages of the Admiralties makes it difficult (if not impossible) to search for their traces in the contemporary Austronesian languages of these islands. Here, we analyze mtDNA and NRY variation in contemporary Admiralty Islanders in order to search for genetic traces of the pre-Austronesian inhabitants and to test if the Austronesian language replacement on these islands was accompanied by a genetic replacement. Our results provide further insights into the genetic impact of the Austronesian expansion and enhance our understanding of the human colonization of Island Melanesia and the southern Pacific region.” ref

“The observed higher frequencies of Asian than Melanesian mtDNA haplogroups in the Admiralty Islanders, together with their higher frequencies of Melanesian than Asian NRY haplogroups, suggest sex-biased genetic admixture between the incoming Austronesians and the local non-Austronesians inhabitants of northern Island Melanesia. Thus, the data presented here provide additional support for the Slow Boat model of Polynesian origins because the genetic findings concerning the Admiralties of northern Island Melanesia, the region of assumed first contact between the incoming pre-Proto-Oceanic–speaking Austronesians and the local non-Austronesian inhabitants of Melanesia were similar to those from Polynesia, the final eastern destination of the Austronesian expansion. The observation of more Asian mtDNA haplogroups than Asian NRY haplogroups on the Admiralty Islands as well as in other Austronesian-speaking groups from coastal New Guinea and Island Melanesia suggests that the Austronesian language replacement in Melanesia was driven by Austronesian women rather than men, perhaps as a consequence of a matrilocal residence pattern in combination with a matrilineal social structure.” ref

“Sex-biased admixture is also observed in those groups speaking non-Austronesian languages in coastal New Guinea and Island Melanesia, but here there was a much bigger contribution inferred for Austronesian women than for Austronesian men, in keeping with the patrilocal residence and patrilineal social structure of non-Austronesian (Papuan) groups in Melanesia. The major Asian NRY haplogroup on the Admiralties (O-M110) can be ultimately traced back to Taiwan, which provides a genetic parallel to mtDNA data evidence and strikingly intersects with linguistic and archaeological evidence for a Taiwanese source of the Austronesian expansion.” ref

“Furthermore, our genetic data are in line with archaeological evidence suggesting human Pleistocene contacts between mainland New Guinea and the Admiralties, as we found most known NRY and mtDNA haplogroups with an inferred origin in mainland New Guinea on the Admiralties, as well as with other archaeological data proposing at most limited human contacts between the Admiralties and the nearby New Britain and New Ireland, as we found many mtDNA and NRY haplogroups with an inferred origin in New Britain/New Ireland absent or nearly so in the Admiralties. Finally, we showed that the Melanesian NRY haplogroup K-P79 was most likely contributed to Polynesia from New Britain/New Ireland, and in fact northern Island Melanesia may have been the source of all the haplogroups of Melanesian origin found in Polynesia. Thus, the work reported here substantially advances our knowledge on the genetic impact of the Austronesian expansion and human history in the western and southern Pacific region.” ref

“Strong genetic affinity with the indigenous Taiwan aborigines, which may support a coastal route of the Jomon-ancestry migration, 2,500-year-old individual (IK002) from the main-island of Japan that is characterized with a typical Jomon culture.” ref

Ancient Jomon genome sequence analysis sheds light on migration patterns of early East Asian populations

“Abstract: Anatomically modern humans reached East Asia more than 40,000 years ago. However, key questions still remain unanswered with regard to the route(s) and the number of wave(s) in the dispersal into East Eurasia. Ancient genomes at the edge of the region may elucidate a more detailed picture of the peopling of East Eurasia. Here, we analyze the whole-genome sequence of a 2,500-year-old individual (IK002) from the main-island of Japan that is characterized with a typical Jomon culture. The phylogenetic analyses support multiple waves of migration, with IK002 forming a basal lineage to the East and Northeast Asian genomes examined, likely representing some of the earliest-wave migrants who went north from Southeast Asia to East Asia. Furthermore, IK002 shows strong genetic affinity with the indigenous Taiwan aborigines, which may support a coastal route of the Jomon-ancestry migration. This study highlights the power of ancient genomics to provide new insights into the complex history of human migration into East Eurasia.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Japan’s population Origins and Religious Beliefs from around 35,000 to 500 years ago

“After the major Out-of-Africa dispersal of Homo sapiens around 60,000 years ago, modern humans rapidly expanded across the vast landscapes of Eurasia. Both fossil and ancient genomic evidence suggest that groups ancestrally related to present-day East Asians were present in eastern China by as early as 40,000 years ago. Two major routes for these dispersals have been proposed, either from the northern or southern parts of the Himalaya mountains. Population genomic studies on present-day humans have exclusively supported the southern route origin of East Asian populations. On the other hand, the archaeological record provides strong support for the northern route as the origin of human activity, particularly for the arrival at the Japanese archipelago located at the east end of Eurasian continent. The oldest use of Upper Paleolithic stone tools goes back 38,000 years, and microblades, likely originated from an area around Lake Baikal in Central Siberia, are found in the northern island (i.e., Hokkaido; ~25,000 years ago) and main-island (i.e., Honshu; ~20,000 years ago) of the Japanese archipelago.” ref

“However, few human remains were found from the Upper Paleolithic sites in the archipelago. The Jomon culture started >16,000 years ago, characterized by a hunter-fisher-gathering lifestyle with the earliest use of pottery in the world. This Jomon culture lasted until a start of rice cultivation which brought by people migrated from the Eurasian continent, plausibly through the Korean peninsula, to northern parts of Kyushu island in the Japanese archipelago 3,000 years ago. Several lines of archaeological evidence support the cultural continuity from the Upper-Paleolithic to the Jomon period, providing a hypothesis that the Jomon people are direct descendants of Upper-Paleolithic people who likely remained isolated in the archipelago until the end of Last Glacial Maximum. Therefore, ancient genomics of the Jomon can provide new insights into the origin and migration history of East Asians.” ref

“A critical challenge for ancient genomics with samples from the Japanese archipelago is the inherent nature of warm and humid climate conditions except for the most north island, Hokkaido, and the soils indicating strong acidity because of the volcanic islands, which generally result in poor DNA preservation. Though whole-genome sequences of two Hokkaido Jomon individuals dated to be 3500–3800-year-old were recently published with sufficient coverage, a partial genome of a 3000-year-old Jomon individual from the east-north part of Honshu Japan was reported, with very limited coverage (~0.03-fold) due to the poor preservation. To identify the origin of the Jomon people, we sequenced the genome of a 2500-year-old Jomon individual (IK002) excavated from the central part of Honshu to 1.85-fold genomic coverage.” ref

“Comparing this IK002 genome with ancient Southeast Asians, we previously reported genetic affinity between IK002 and the 8000 years old Hòabìnhian hunter-gatherer. This direct evidence on the link between the Jomon and Southeast Asians, thus, suggests the southern route origin of the Jomon lineage. Nevertheless, key questions still remain as to (1) whether the Jomon were the direct descendant of the Upper Paleolithic people who were the first migrants into the Japanese archipelago and (2) whether the Jomon, as well as present-day East Asians, retain ancestral relationships with people who took the northern route.” ref

“Here, we test the deep divergence of the Jomon lineage and the impacts of southern- versus northern-route ancestry on the genetic makeup of the Jomon. The Jomon forms a lineage basal to both ancient and present-day East Asians; this deep origin supports the hypothesis that the Jomon were direct descendants of the Upper Paleolithic people. Furthermore, the Jomon has strong genetic affinities with the indigenous Taiwan aborigines. Our study shows that the Jomon-related ancestry is one of the earliest-wave migrants who might have taken a coastal route on the way from Southeast Asia toward East Asia.” ref

Subsequently, we carried out model-based unsupervised clustering using ADMIXTURE. Assuming K = 15 ancestral clusters, an ancestral component unique to IK002 appears, which is the most prevalent in the Hokkaido Ainu (average 79.3%). This component is also shared with present-day Honshu Japanese as well as Ulchi (9.8% and 6.0%, respectively). Those results also support the strong genetic affinity between IK002 and the Hokkaido Ainu.” ref

“We used ALDER in order to date the timing of admixture in populations with Jomon ancestry. Using IK002 and the Hokkaido Jomon as a merged source population representing Jomon ancestry, and present-day Han Chinese as the second source representing mainland East Asian ancestry, we estimated the admixture in present-day Honshu Japanese to be between 60 and 77 generations ago (~1700–2200 years ago assuming 29 years/generation), which is slightly earlier than previous estimates but more consistent with the archaeological record. This indicates the admixture started and continuously occurred after the Yayoi period. For the Ulchi we estimated a more recent timing (31–47 generations ago) consistent with the higher variance in the IK002 component observed in ADMIXTURE. Finally, we detected more recent (17–25 generations ago) admixture for the Hokkaido Ainu, likely a consequence of still ongoing gene flow between the Hokkaido Ainu and Honshu Japanese. The estimates of admixture timing are consistent when replacing Han with Korean, Ami or Devil′s Gate cave as mainland East Asian source population, and exponential curves from a single admixture event fit the observed LD curve well.” ref

“To further explore the deep relationships between the Jomon and other Eurasian populations, we used TreeMix to reconstruct admixture graphs of IK002 and 18 ancient and present-day Eurasians and Native Americans. We found the IK002 lineage placed basal to the divergence between ancient and present-day Tibetans and to the common ancestor of the remaining ancient/present-day East Eurasians and Native Americans. These genetic relationships are stable across different numbers of migration incorporated into the analysis. Major gene flow events recovered include the well-documented contribution of the Mal′ta individual (MA-1) to the ancestor of Native Americans, as well as a contribution of IK002 to present-day mainland Japanese (m = 3–8) .” ref

“IK002 can be modeled as a basal lineage to East Asians, Northeast Asians/East Siberians, and Native Americans, supporting a scenario in which their ancestors arrived through the southern route and migrated from Southeast Asia toward Northeast Asia. However, regarding Native Americans, high genetic contributions (11.8–36.8%) were detected from the Upper Paleolithic individual, MA-1, which means that Native Americans were admixture between the southern and the northern routes as shown in Raghavan et al. (2014). The divergence of IK002 from the ancestors of continental East Asians therefore likely predates the split between East Asians and Native Americans, which has been previously estimated at 26,000 years ago. Thus, our TreeMix results support the hypothesis that IK002 is a direct descendant of the people who brought the Upper Paleolithic stone tools 38,000 years ago into the Japanese archipelago.” ref

Taiwanese Indigenous Peoples

“Taiwanese indigenous peoples, also known as Native Taiwanese, Formosan peoples, Austronesian Taiwanese, Yuanzhumin or Gaoshan people, and formerly as Taiwanese aborigines, are the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, with the nationally recognised subgroups numbering about 569,000 or 2.38% of the island’s population. This total is increased to more than 800,000 if the indigenous peoples of the plains in Taiwan are included, pending future official recognition. When including those of mixed ancestry, such a number is possibly more than a million. Academic research suggests that their ancestors have been living on Taiwan for approximately 6,500 years. A wide body of evidence suggests that the Taiwanese indigenous peoples had maintained regular trade networks with numerous regional cultures of Southeast Asia before the Han Chinese colonists began settling on the island from the 17th century, at the behest of the Dutch colonial administration and later by successive governments towards the 20th century.” ref

“Taiwanese indigenous peoples are Austronesians, with linguistic, genetic and cultural ties to other Austronesian peoples in the region. Taiwan is also the origin and linguistic homeland of the oceanic Austronesian expansion whose descendant groups today include the majority of the ethnic groups throughout many parts of East and Southeast Asia as well as Oceania, which includes Brunei, East Timor, Indonesia, Malaysia, Madagascar, Philippines, Micronesia, Island Melanesia and Polynesia. The Chams and Utsul of contemporary central and southern Vietnam and Hainan respectively are also a part of the Austronesian family.” ref

“Currently, there are 16 officially recognized indigenous tribes in Taiwan: Amis, Atayal, Paiwan, Bunun, Puyuma, Rukai, Tsou, Saisiyat, Yami, Thao, Kavalan, Truku, Sakizaya, Sediq, Hla’alua and Kanakanavu.” ref

“Taiwan has been settled for at least 25,000 years. Ancestors of Taiwanese indigenous peoples settled the island around 6,000 years ago.” ref

“Taiwan was joined to the Asian mainland in the Late Pleistocene, until sea levels rose about 10,000 years ago. Human remains and Paleolithic artifacts dated 20,000 to 30,000 years ago have been found. Study of the human remains suggested they were Australo-Papuan people similar to Negrito populations in the Philippines. Paleolithic Taiwanese likely settled the Ryukyu Islands 30,000 years ago. Slash-and-burn agriculture practices started at least 11,000 years ago.” ref

“Stone tools of the Changbin culture have been found in Taitung and Eluanbi. Archaeological remains suggest they were initially hunter-gatherers that slowly shifted to intensive fishing. The distinct Wangxing culture, found in Miaoli County, were initially gatherers who shifted to hunting. Around 6,000 years ago, Taiwan was settled by farmers of the Dapenkeng culture, most likely from what is now southeast China. These cultures are the ancestors of modern Taiwanese Indigenous peoples and the originators of the Austronesian language family.” ref

“Trade with the Philippines persisted from the early 2nd millennium BCE, including the use of Taiwanese jade in the Philippine jade culture. The Dapenkeng culture was succeeded by a variety of cultures throughout the island, including the Tahu and Yingpu; the Yuanshan were characterized by rice harvesting. Iron appeared in such cultures as the Niaosung culture, influenced by trade with China and Maritime Southeast Asia. The Plains Indigenous peoples mainly lived in permanent walled villages, with a lifestyle based on agriculture, fishing, and hunting. They had traditionally matriarchal societies.” ref

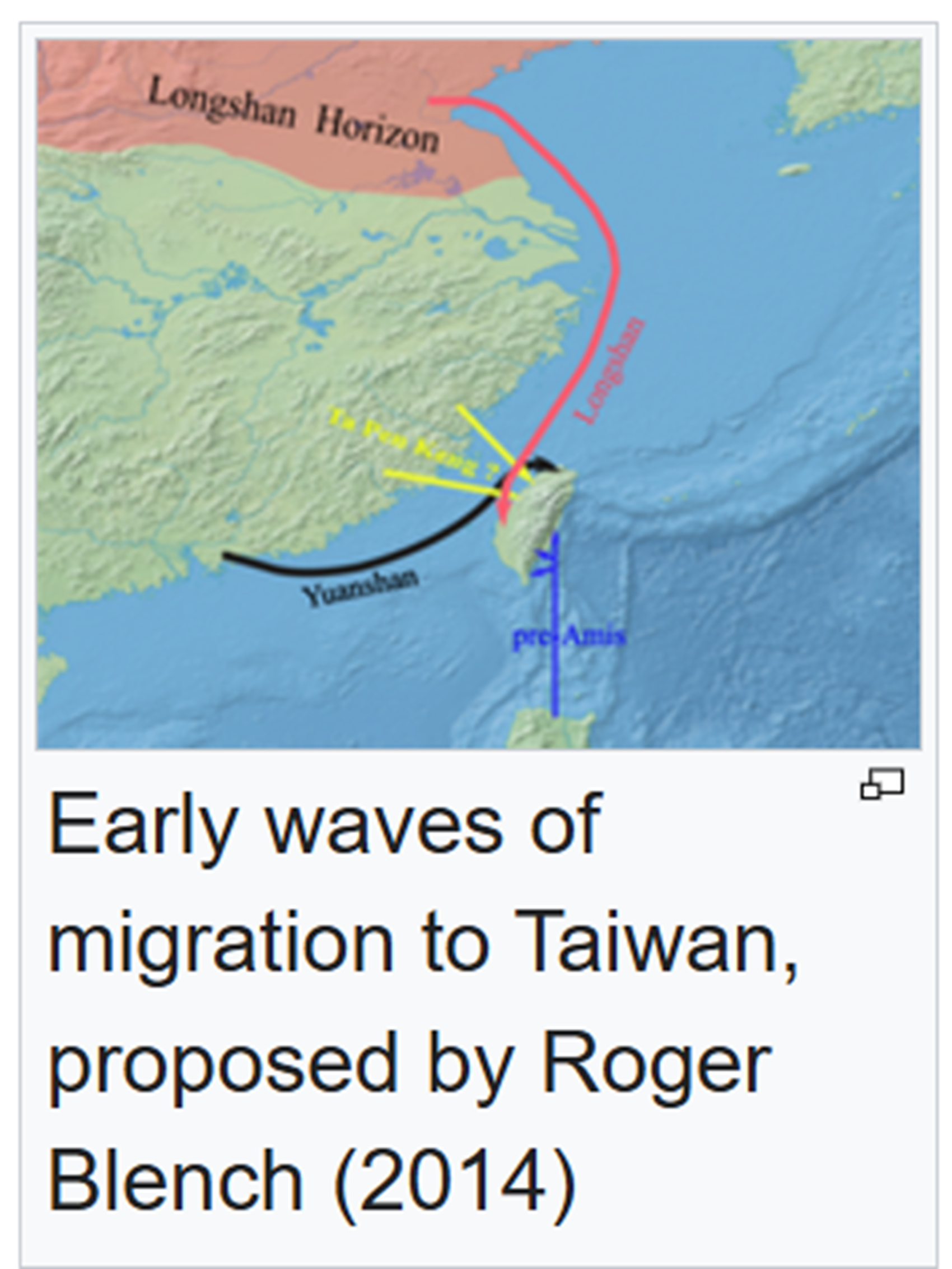

The early migration route of early Austronesians into and out of Taiwan was suggested based on ancient and modern mtDNA data. This hypothesis assumes the Sino-Austronesian grouping, a minority view among linguists. (Ko et al.., 2014)” ref

Dapenkeng Culture

“The Dapenkeng culture (Chinese: 大坌坑文化; pinyin: Dàbènkēng wénhuà) was an early Neolithic culture that appeared in northern Taiwan between 4000 and 3000 BC and quickly spread around the coast of the island, as well as the Penghu islands to the west. Most scholars believe this culture was brought across the Taiwan Strait by the ancestors of today’s Taiwanese aborigines, speaking early Austronesian languages. No ancestral culture on the mainland has been identified, but a number of shared features suggest ongoing contacts.” ref

“The Sino-Austronesian hypothesis, on the other hand, is a relatively new hypothesis by Laurent Sagart, first proposed in 1990. It argues for a north–south linguistic genetic relationship between Chinese and Austronesian. This is based on sound correspondences in basic vocabulary and morphological parallels. Sagart places special significance in shared vocabulary on cereal crops, citing them as evidence of shared linguistic origin. However, this has largely been rejected by other linguists. The sound correspondences between Old Chinese and Proto-Austronesian can also be explained as a result of the Longshan interaction sphere, when pre-Austronesians from the Yangtze region came into regular contact with Proto-Sinitic speakers in the Shandong Peninsula, around the 4th to 3rd millennia BCE.” ref

“This corresponded with the widespread introduction of rice cultivation to Proto-Sinitic speakers and conversely, millet cultivation to Pre-Austronesians. An Austronesian substratum in formerly Austronesian territories that have been Sinicized after the Iron Age Han expansion is also another explanation for the correspondences that do not require a genetic relationship. In relation to Sino-Austronesian models and the Longshan interaction sphere, Roger Blench (2014) suggests that the single migration model for the spread of the Neolithic into Taiwan is problematic, pointing out the genetic and linguistic inconsistencies between different Taiwanese Austronesian groups. The surviving Austronesian populations in Taiwan should rather be considered as the result of various Neolithic migration waves from the mainland and back-migration from the Philippines. These incoming migrants almost certainly spoke languages related to Austronesian or pre-Austronesian, although their phonology and grammar would have been quite diverse.” ref

“Blench considers the Austronesians in Taiwan to have been a melting pot of immigrants from various parts of the coast of East China that had been migrating to Taiwan by 4000 years ago. These immigrants included people from the foxtail millet-cultivating Longshan culture of Shandong (with Longshan-type cultures found in southern Taiwan), the fishing-based Dapenkeng culture of coastal Fujian, and the Yuanshan culture of northernmost Taiwan, which Blench suggests may have originated from the coast of Guangdong. Based on geography and cultural vocabulary, Blench believes that the Yuanshan people may have spoken Northeast Formosan languages. Thus, Blench believes that there is in fact no “apical” ancestor of Austronesian in the sense that there was no true single Proto-Austronesian language that gave rise to present-day Austronesian languages. Instead, multiple migrations of various pre-Austronesian peoples and languages from the Chinese mainland that were related but distinct came together to form what we now know as Austronesian in Taiwan. Hence, Blench considers the single-migration model into Taiwan by pre-Austronesians to be inconsistent with both the archaeological and linguistic (lexical) evidence.” ref

The Sino-Austronesian hypothesis/Sino-Austronesian languages

“Sino-Austronesian or Sino-Tibetan-Austronesian is a proposed language family suggested by Laurent Sagart in 1990. Using reconstructions of Old Chinese, Sagart argued that the Austronesian languages are related to the Sinitic languages phonologically, lexically and morphologically. Sagart later accepted the Sino-Tibetan languages as a valid group and extended his proposal to include the rest of Sino-Tibetan. He also placed the Tai–Kadai languages within the Austronesian family as a sister branch of Malayo-Polynesian. The proposal has been largely rejected by other linguists who argue that the similarities between Austronesian and Sino-Tibetan more likely arose from contact rather than being genetic.” ref

“Sagart suggests that monosyllabic Old Chinese words correspond to the second syllables of disyllabic Proto-Austronesian roots. However, the type A/B distinction in OC, corresponding to non-palatalized or palatalized syllables in Middle Chinese, is considered to correspond to a voiceless/voiced initial in PAN. Stanley Starosta (2005) expands Sagart’s Sino-Austronesian tree with a “Yangzian” branch, consisting of Austroasiatic and Hmong–Mien, to form an East Asian superphylum. Weera Ostapirat (2005) supports the link between Austronesian and Kra–Dai (Sagart built upon Ostapirat’s findings), though as sister groups. However, he rejects a link to Sino-Tibetan, noting that the apparent cognates are rarely found in all branches of Kra–Dai, and almost none are in core vocabulary.” ref

“Austronesian linguists Paul Jen-kuei Li and Robert Blust have criticized Sagart’s comparisons, on the grounds of loose semantic matches, inconsistent correspondences, and that basic vocabulary is hardly represented. They also note that comparing with the second syllable of disyllabic Austronesian roots vastly increases the odds of chance resemblance. Blust has been particularly critical of Sagart’s use of the comparative method. Laurent Sagart (2016) responds to some of the criticisms by Blust (2009).” ref

“Alexander Vovin (1997) does not accept Sino-Austronesian as a valid grouping, but instead suggests that some of the Sino-Austronesian parallels proposed by Sagart may in fact be due to an Austronesian substratum in Old Chinese. This view is also espoused by George van Driem, who suggests that Austronesian and Sinitic had come into contact with each other during the fourth and third millennia BCE in the Longshan interaction sphere.” ref

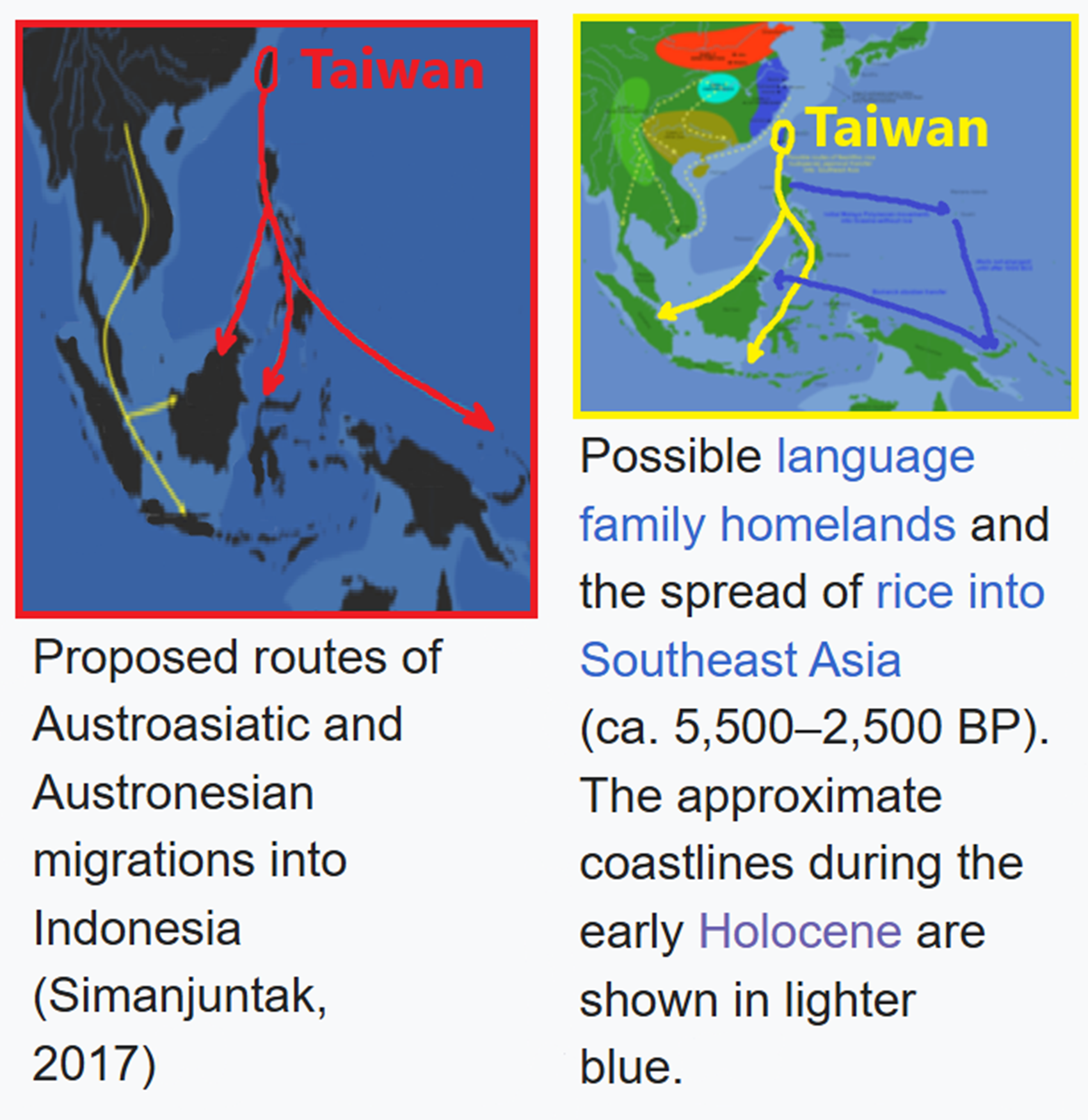

“Left: Proposed routes of Austroasiatic and Austronesian migrations into Indonesia (Simanjuntak, 2017).” ref

“Right: Possible language family homelands and the spread of rice into Southeast Asia (ca. 5,500–2,500 years ago). The approximate coastlines during the early Holocene are shown in lighter blue.” ref

“These early settlers are generally historically referred to as “Australo-Melanesians“, though the terminology is problematic, as they are genetically diverse, and most groups within Austronesia have significant Austronesian admixture and culture. The unmixed descendants of these groups today include the interior Papuans and Indigenous Australians.” ref

“In modern literature, descendants of these groups, located in Island Southeast Asia west of Halmahera, are usually collectively referred to as “Negritos“, while descendants of these groups east of Halmahera (excluding Indigenous Australians) are referred to as “Papuans“. They can also be divided into two broad groups based on Denisovan admixture. Philippine Negritos, Papuans, Melanesians, and Indigenous Australians display Denisovan admixture, while Malaysian and western Indonesian Negritos (Orang Asli) and Andamanese islanders do not.” ref

“Mahdi (2017) also uses the term “Qata” (from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *qata) to distinguish the indigenous populations of Southeast Asia, versus “Tau” (from Proto-Austronesian *Cau) for the later settlers from Taiwan and mainland China. Both are based on proto-forms for the word “person” in Malayo-Polynesian languages that referred to darker-skinned and lighter-skinned groups, respectively. Jinam et al. (2017) also proposed the term “First Sundaland People” in place of “Negrito”, as a more accurate name for the original population of Southeast Asia.” ref

“These populations are genetically distinct from later Austronesians, but through fairly extensive population admixture, most modern Austronesians have varying levels of ancestry from these groups. The same is true for some populations historically considered “non-Austronesians”, due to physical differences—like Philippine Negritos, Orang Asli, and Austronesian-speaking Melanesians, all of whom have Austronesian admixture. In Polynesians in Remote Oceania, for example, the admixture is around 20 to 30% Papuan and 70 to 80% Austronesian. The Melanesians in Near Oceania are roughly around 20% Austronesian and 80% Papuan, while in the natives of the Lesser Sunda Islands, the admixture is around 50% Austronesian and 50% Papuan. Similarly, in the Philippines, the groups traditionally considered to be “Negrito” vary between 30 and 50% Austronesian.” ref

“The high degree of assimilation among Austronesian, Negrito, and Papuan groups indicates that the Austronesian expansion was largely peaceful. Rather than violent displacement, the settlers and the indigenous groups absorbed each other. It is believed that in some cases, like in the Toalean culture of Sulawesi (c. 8,000–1,500 years ago), it is even more accurate to say that the densely populated indigenous hunter-gatherer groups absorbed the incoming Austronesian farmers, rather than the other way around. Mahdi (2016) further asserts that Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *tau-mata (“person”) is derived from a composite protoform *Cau ma-qata, combining “Tau” and “Qata” and indicative of the mixing of the two ancestral population types in these regions.” ref

“The broad consensus on the Urheimat (homeland) of Austronesian languages as well as the Neolithic early Austronesian peoples is accepted to be Taiwan, as well as the Penghu Islands. They are believed to have descended from ancestral populations in coastal mainland southern China, which are generally referred to as the “pre‑Austronesians”. Through these pre-Austronesians, Austronesians may also share a common ancestry with neighboring groups in Neolithic southern China.” ref

“These Neolithic pre-Austronesians from the coast of southeastern China are believed to have migrated to Taiwan between approximately 10,000 and 6000 BCE. Other research has suggested that, according to radiocarbon dates, Austronesians may have migrated from mainland China to Taiwan as late as 4000 BCE (Dapenkeng culture). They continued to maintain regular contact with the mainland until 1500 BCE.” ref

“The identity of the Neolithic pre-Austronesian cultures in China is contentious. Tracing Austronesian prehistory in Fujian and Taiwan has been difficult due to the southward expansion of the Han dynasty (2nd century BCE) and the recent Qing dynasty annexation of Taiwan (1683 CE). Today, the only Austronesian language in southern China is Tsat, spoken in Hainan. The politicization of archaeology is also problematic, particularly erroneous reconstructions among some Chinese archaeologists of non-Sinitic sites as Han. Some authors, favoring the “Out of Sundaland” model, like William Meacham, reject the southern Chinese mainland origin of pre-Austronesians entirely.” ref

“Nevertheless, based on linguistic, archaeological, and genetic evidence, Austronesians are most strongly associated with the early farming cultures of the Yangtze River basin that domesticated rice from around 13,500 to 8,200 years ago. They display typical Austronesian technological hallmarks, including tooth removal, teeth blackening, jade carving, tattooing, stilt houses, advanced boatbuilding, aquaculture, wetland agriculture, and the domestication of dogs, pigs, and chickens. These include the Kuahuqiao, Hemudu, Majiabang, Songze, Liangzhu, and Dapenkeng cultures that occupied the coastal regions between the Yangtze River delta and the Min River delta.” ref

“Based on linguistic evidence, there have been proposals linking Austronesians with other linguistic families into linguistic macrofamilies that are relevant to the identity of the pre-Austronesian populations. The most notable are the connections of Austronesians to the neighboring Austroasiatic, Kra-Dai, and Sinitic peoples (as Austric, Austro-Tai, and Sino-Austronesian, respectively). These are still not widely accepted, as evidence of these relationships are still tenuous, and the methods used are highly contentious.” ref

“In support of both the Austric and Austro-Tai hypothesis, Robert Blust connects the lower Yangtze Neolithic Austro-Tai entity with the rice-cultivating Austroasiatic cultures, assuming the center of East Asian rice domestication, and putative Austric homeland, to be located in the Yunnan/Burma border area, instead of the Yangtze River basin, as is currently accepted. Under that view, there was an east–west genetic alignment, resulting from a rice-based population expansion, in the southern part of East Asia: Austroasiatic-Kra-Dai-Austronesian, with unrelated Sino-Tibetan occupying a more northerly tier. Depending on the author, other hypotheses have also included other language families like Hmong-Mien and even Japanese-Ryukyuan into the larger Austric hypothesis.” ref

“While the Austric hypothesis remains contentious, there is genetic evidence that at least in western Island Southeast Asia, there had been earlier Neolithic overland migrations (pre-4,000 years ago) by Austroasiatic-speaking peoples into what is now the Greater Sunda Islands when the sea levels were lower, in the early Holocene. These peoples were assimilated linguistically and culturally by incoming Austronesian peoples in what is now modern-day Indonesia and Malaysia.” ref

“The proposed genesis of Daic languages and their relation with Austronesians (Blench, 2018).” ref

“Several authors have also proposed that Kra-Dai speakers may actually be an ancient daughter subgroup of Austronesians that migrated back to the Pearl River Delta from Taiwan and/or Luzon, shortly after the Austronesian expansion, later migrating further westwards to Hainan, Mainland Southeast Asia, and Northeast India. They propose that the distinctiveness of Kra-Dai (it is tonal and monosyllabic) was the result of linguistic restructuring due to contact with Hmong-Mien and Sinitic cultures. Aside from linguistic evidence, Roger Blench has also noted cultural similarities between the two groups, like facial tattooing, tooth removal or ablation, teeth blackening, snake (or dragon) cults, and the multiple-tongued jaw harps shared by the indigenous Taiwanese and Kra-Dai-speakers.” ref

“However, archaeological evidence for this is still sparse. This is believed to be similar to what happened to the Cham people, who were originally Austronesian settlers (likely from Borneo) to southern Vietnam around 2100–1900 years ago and had languages similar to Malay. Their languages underwent several restructuring events to syntax and phonology due to contact with the nearby tonal languages of Mainland Southeast Asia and Hainan. Although the populations of the Malay peninsula, Sumatra, Java, and neighboring islands are Austronesian-speaking, they have significantly high admixture from Mainland Southeast Asian populations. These areas were already populated (most probably by speakers of Austroasiatic languages) before they were reached by the Austronesian expansion, roughly 3,000 years ago. Currently, only the indigenous Aslians still speak Austroasiatic languages. However, some of the languages in the region show signs of underlying Austroasiatic substrates.” ref

“According to Juha Janhunen and Ann Kumar, Austronesians may have also settled parts of southern Japan, especially on the islands of Kyushu and Shikoku, and influenced or created the Japanese hierarchical society. It is suggested that Japanese tribes like the Hayato people, the Kumaso, and the Azumi were of Austronesian origin. Until today, local traditions and festivals show similarities to Malayo-Polynesian culture.” ref

“Map showing the migration of the Austronesians from Taiwan” ref

Migration from Taiwan

“Austronesian expansion (also called the “Out of Taiwan” model) is a large-scale migration of Austronesians from Taiwan, occurring around 3000 to 1500 BCE. Population growth primarily fueled this migration. These first settlers settled in northern Luzon, in the archipelago of the Philippines, intermingling with the earlier Australo-Melanesian population who had inhabited the islands since about 23,000 years earlier. Over the next thousand years, Austronesian peoples migrated southeast to the rest of the Philippines, and into the islands of the Celebes Sea and Borneo. From southwestern Borneo, Austronesians spread further west in a single migration event to both Sumatra and the coastal regions of southern Vietnam, becoming the ancestors of the speakers of the Malayic and Chamic branches of the Austronesian language family.” ref

“Soon after reaching the Philippines, Austronesians colonized the Northern Mariana Islands by 1500 BCE or even earlier, becoming the first humans to reach Remote Oceania. The Chamorro migration was also unique in that it was the only Austronesian migration to the Pacific Islands to successfully retain rice cultivation. Palau and Yap were settled by separate voyages by 1000 BCE.” ref

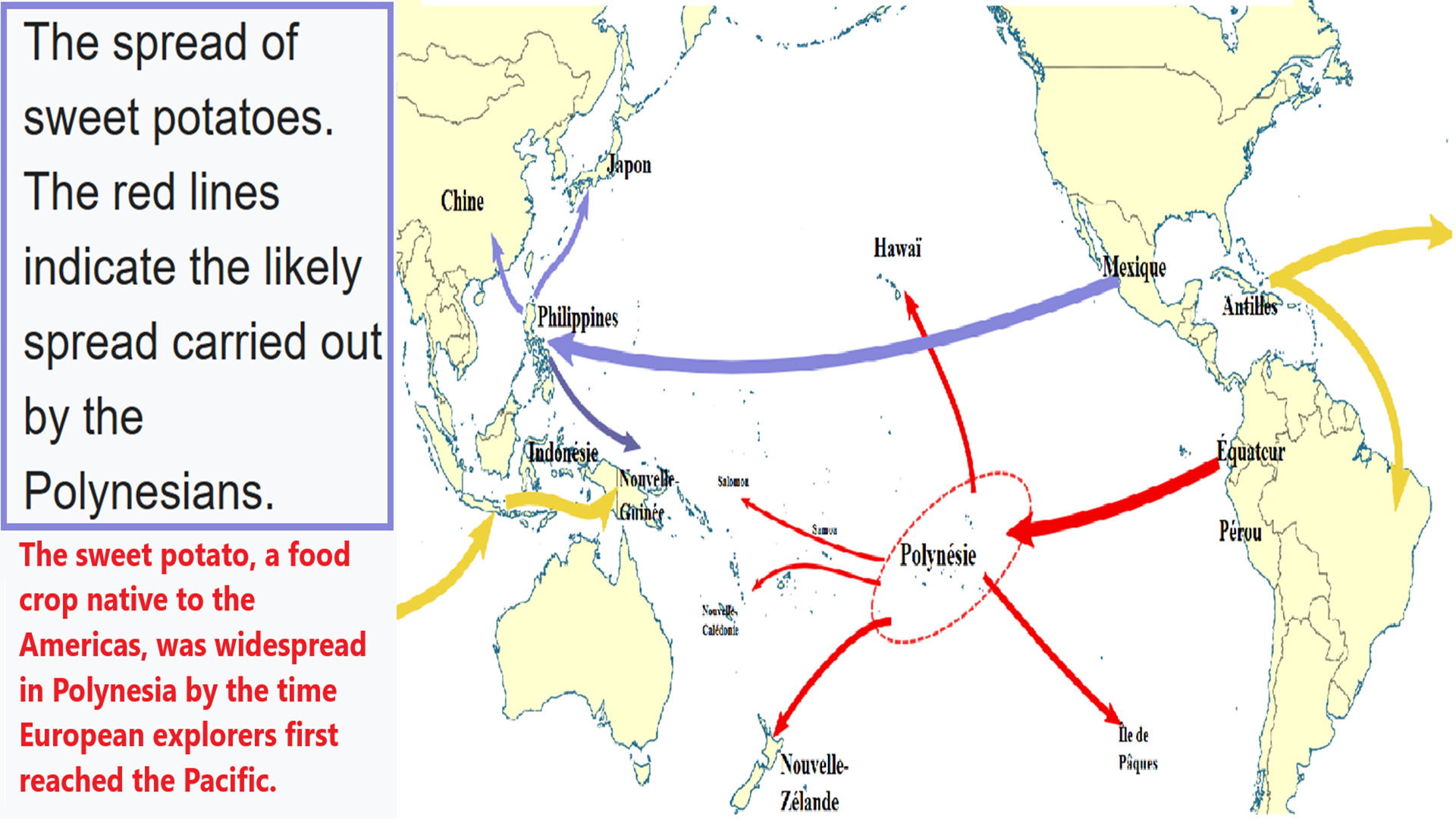

“Another important migration branch was by the Lapita culture, which rapidly spread into the islands off the coast of northern New Guinea and into the Solomon Islands and other parts of coastal New Guinea and Island Melanesia by 1200 BCE. They reached the islands of Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga by around 900 to 800 BCE. This remained the furthest extent of the Austronesian expansion into Polynesia until around 700 CE, when there was another surge of island colonization. It reached the Cook Islands, Tahiti, and the Marquesas by 700 CE; Hawaii by 900 CE; Rapa Nui by 1000 CE; and New Zealand by 1200 CE. For a few centuries, the Polynesian islands were connected by bidirectional long-distance sailing, with the exception of Rapa Nui, which had limited further contact due to its isolated geographical location. Island groups like the Pitcairns, the Kermadec Islands, and the Norfolk Islands were also formerly settled by Austronesians but later abandoned. There is also putative evidence, based in the spread of the sweet potato, that Austronesians may have reached South America from Polynesia, where they might have traded with the Indigenous peoples of the Americas.” ref

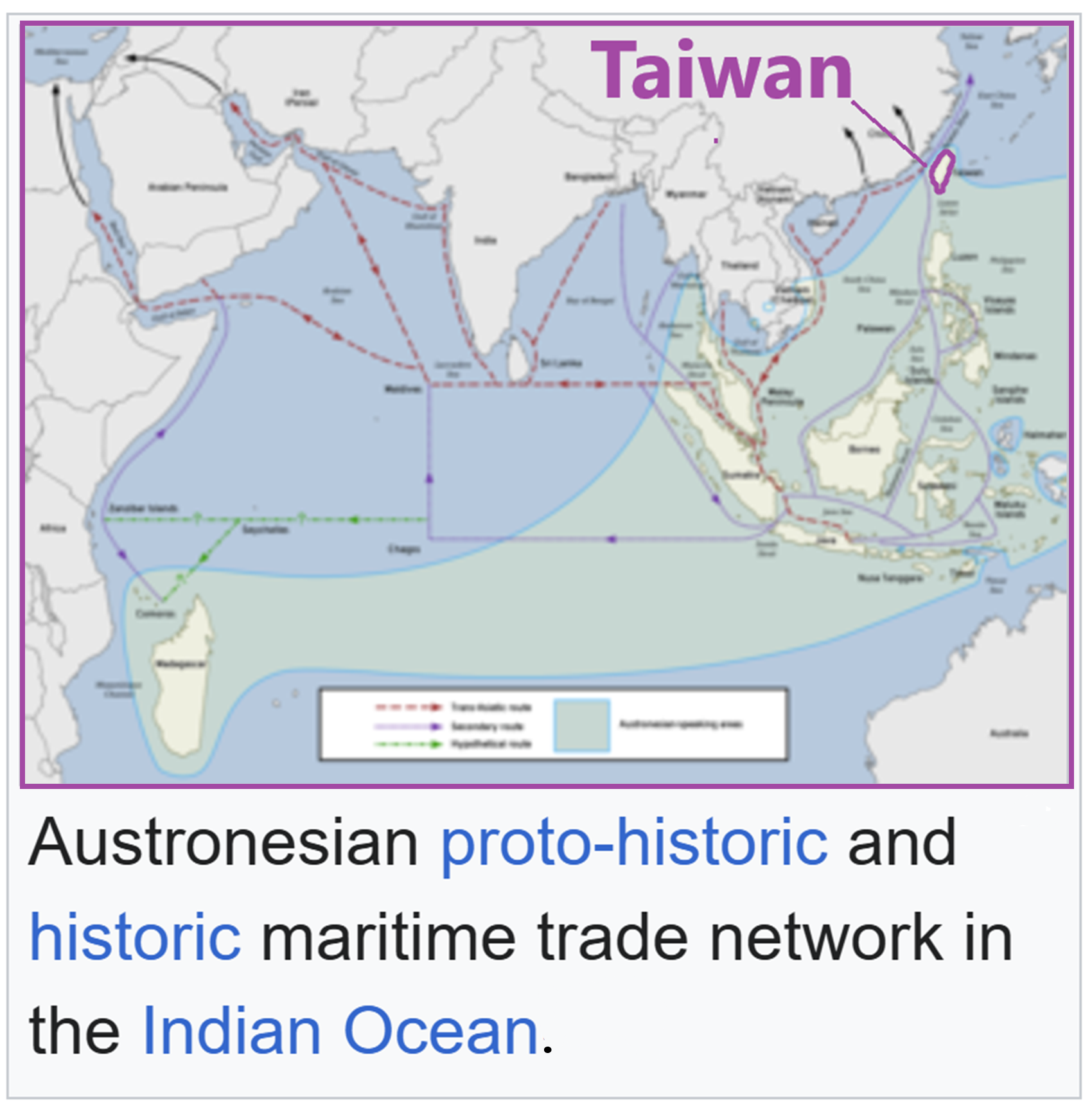

“In the Indian Ocean, Austronesians in Maritime Southeast Asia established trade links with South Asia. They also established early long-distance contacts with Africa, possibly as early as before 500 BCE, based on archaeological evidence like banana phytoliths in Cameroon and Uganda and remains of Neolithic chicken bones in Zanzibar. By the end of the first millennium BCE, Austronesians were already sailing maritime trade routes linking the Han dynasty of China with the western Indian Ocean trade in India, the Roman Empire, and Africa.” ref

“An Austronesian group, originally from the Makassar Strait region around Kalimantan and Sulawesi, eventually settled Madagascar, either directly from Southeast Asia or from preexisting mixed Austronesian-Bantu populations from East Africa. Estimates for when this occurred vary, from the 5th to 7th centuries CE. It is likely that the Austronesians that settled Madagascar followed a coastal route through South Asia and East Africa, rather than directly across the Indian Ocean. Genetic evidence suggests that some individuals of Austronesian descent reached Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.” ref

“The native culture of Austronesia varies from region to region. The early Austronesian peoples considered the sea as the basic feature of their life. Following their diaspora to Southeast Asia and Oceania, they migrated by boat to other islands. Boats of different sizes and shapes have been found in every Austronesian culture, from Madagascar, Maritime Southeast Asia, to Polynesia, and have different names. In Southeast Asia, head-hunting was restricted to the highlands as a result of warfare. Mummification is only found among the highland Austronesian Filipinos and in some Indonesian groups in Celebes and Borneo.” ref

“Seagoing catamaran and outrigger ship technologies were the most important innovations of the Austronesian peoples. They were the first humans with vessels capable of crossing vast distances of water. The crossing from the Philippines to the Mariana Islands at around 1500 BCE, a distance of more than 2,500 km (1,600 mi), is likely the world’s first and longest ocean crossing of that time. These maritime technologies enabled them to colonize the Indo-Pacific in prehistoric times. Austronesian groups continue to be the primary users of outrigger canoes today.” ref

“Early researchers like Heine-Geldern (1932) and Hornell (1943) once believed that catamarans evolved from outrigger canoes, but modern authors specializing in Austronesian cultures, like Doran (1981) and Mahdi (1988), now believe it to be the opposite. Two canoes bound together developed directly from minimal raft technologies of two logs tied together. Over time, the double-hulled canoe form developed into the asymmetric double canoe, where one hull is smaller than the other. Eventually the smaller hull became the prototype outrigger, giving way to the single outrigger canoe, then to the reversible single outrigger canoe. Finally, the single outrigger types developed into the double outrigger canoe (or trimarans).” ref

“This would also explain why older Austronesian populations in Island Southeast Asia tend to favor double outrigger canoes, as it keeps the boats stable when tacking. However, there are small regions where catamarans and single-outrigger canoes are still used. In contrast, more distant outlying descendant populations in Micronesia, Polynesia, Madagascar, and the Comoros retained the double-hull and the single-outrigger canoe types, but the technology for double outriggers never reached them (although it exists in western Melanesia). To deal with the problem of the boat’s instability when the outrigger faces leeward when tacking, they instead developed the shunting technique in sailing, in conjunction with reversible single-outriggers.” ref