Mal’ta–Buret’ culture of Siberia and Basal Haplogroup R* or R-M207

“The Mal’ta–Buret‘ culture is an archaeological culture of the Upper Paleolithic (around 24,000 to 15,000 years ago) on the upper Angara River in the area west of Lake Baikal in the Irkutsk Oblast, Siberia, Russian Federation. The type sites are named for the villages of Mal’ta, Usolsky District and Buret’, Bokhansky District (both in Irkutsk Oblast).” ref

“The “Mal’ta Cluster” is composed of three individuals from the Glacial Maximum 24,000-17,000 years ago from the Lake Baikal region of Siberia.” ref

“From about 55,000 years ago to about 15,000 years ago, the mammoth hunters are distinguished by their yurts built of mammoth bones. During that time their physical appearance changed from the rugged Neanderthal type to the more modern type like ourselves. The architecture of the yurts improved until 15,000 years ago, they were neatly constructed with the bones fitted together in patterns. Society seems to have developed too, with larger villages and the yurts arranged along streets. And with a ceremonial lodge as a main feature.” ref

“Blades and Microblades, Percussion and Pressure: Towards the Evolution of Lithic Technologies of the Stone Age Period, Russian Far East around 22,530 to 5,830 years ago. Russian Far East. Cultures and sites locations. 1 Selemja Culture; 2 Gromatukhinskaya and Novopetrovskaya Cultures ; 3 Osipovskaya Culture; 4 Mariinskaya Culture; 5 Ustinovka Culture; 6 Vetka Culture; 7 Ogonki Sites; 8 Ushki Lake sites.” ref

“When the mammoth hunters first arrived in Europe from Siberia, about 30,000 to 35,000 years ago, they brought with them a far more advanced technology and culture to the native Neanderthal population. Although the Neanderthals at the time were not far behind, this new culture was far more advance in so many ways that the European Neanderthals were from that time history. This is referred to as the Aurignacian culture and sites have been across Europe as well as in Siberia. These perhaps represent the first wave of “modern” European settlers as can be traced in the Y chromosomes of European men as originating from South Siberia.” ref

“The next wave of migrants into Europe from Siberia from 28,000 to 22,000 years ago is called the “Gravettian culture”. This is also traceable in the Y chromosome indicating orgins of European men as from South Siberia. Not just more advanced in technology, but also in trading relations and cultural and some kind of political relationship with other peoples. This is shown by the little portable “mother” figurines found at such mammoth hunter sites from across Europe, France, Czech Republic etc. and in South Siberia itself.” ref

The development of this culture can be found in sites in south Siberia such as those of Mal’ta and Buret. Finds from the mammoth-hunter yurts excavated near the Angara River (especally Mal’ta and Buret) sites start at a date of about 24,000 years ago. At Malta, with large and small round houses, partly dug out of the ground (as homes were in the north until into the Iron Age) and built with a low wall of stone and then roofed over with mammoth bones, reindeer antlers etc. – which would have been covered with mammoth hides. At Buret, the people lived together in large dwellings, several families together. There were three hearths in each – one in the center, and one either end.” ref

“Paleolithic art of Europe and Asia falls into two broad categories: mural art and portable art. Mural art is concentrated in southwest France, Spain, and northern Italy. The tradition of portable art, predominantly carvings in ivory and antler, spans the distance across western Europe into North and Central Asia. It is suggested that the broad territory in which the tradition of carving and imagery is shared is evidence of cultural contact and common religious beliefs.” ref

“Female/Mother images have been found right across the mammoth-hunter area. Artistically they vary. Some are very abstract and sophisticated. The mother figurines near the Angara River are mostly naturallistic. They show real women, with braided hair styles, possibly tattoos or body paint, saggy breasts, and in some cases it could represent clothing – a fur onesie or jumpsuit – much as was still worn until recently by the Chukchi and Koryak women in the North Pacific regions. These could be interpreted as protective “mothers” for childbirth, hunting, the home, the tribal territory, the earth and land itself, etc. Clearly many iconic beliefs still held today were already well established some 25,000 years ago.” ref

“Totally there are 39 or 40 known figurines found both on Mal’ta and Buret and although the ancient Siberian Venus figurines ‘are NOT Venuses (not depicting goddesses or gods). At least some if not many are show of ordinary people of seemingly all ages in clothing dating from some 20,000 years ago. Far from being only idealized female forms. many are seemingly male, and others could represent children. It’s true that in the past some of the woolly mammoth tusk carvings were known to be clothed as well as the different types of hats, hairstyles, shoes and accessories. Notably, these were called alluringly Venus in Furs figurines. They were dressed for protection from the Siberian winter, and are possibly the oldest known images anywhere in the world of sewn fur clothing. Through scientific study traces on the surface of the figurines were seen not visible to the naked eye, due to the ravages of time. These traces showed more details of clothes than we had seen previously: bracelets, hats, shoes, bags and even back packs. ” ref

“At one of the three hearths of the long house, were found “mother” dolls together with bracelets, headbands, pins and spatulas (which could be used for applying makeup). This is easily interpreted as the women’s quarters, especially as at the hearth at the other end, was found weapons, tools, jewellry and small ivory images of phallic looking swans – made to wear as pendants. Such swan pendants were also found in the tombs of men.” ref

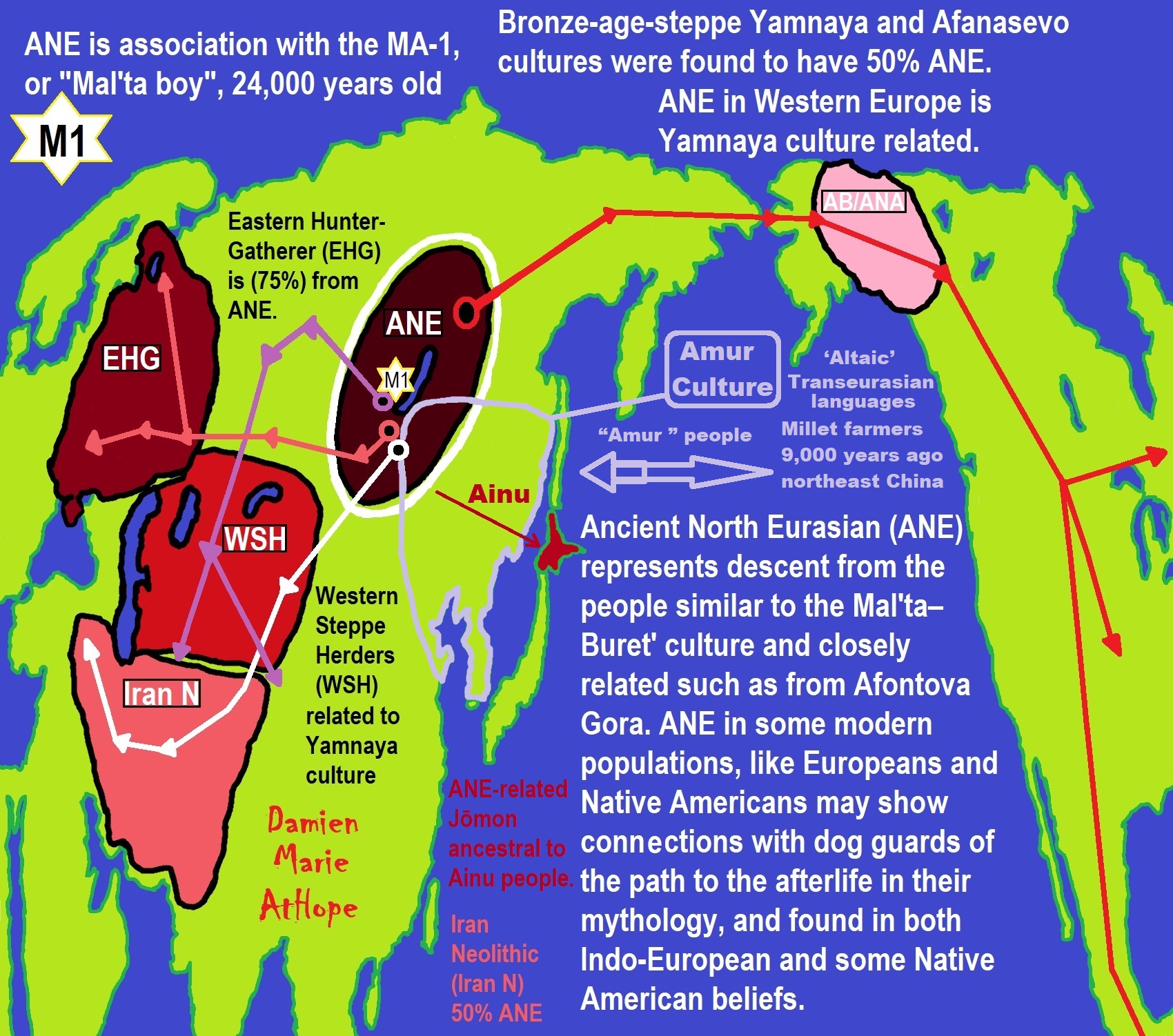

“MA-1 is the abbreviation of male child remains found near Mal’ta dated to 24,000 years ago, who belonged to a population related to the genetic ancestors of Siberians, American Indians, and Bronze Age Yamnaya people of the Eurasian steppe. In particular, modern-day Native Americans, Kets, Mansi, Nganasans and Yukaghirs were found to be harbour a lot of ancestry related to MA-1.” ref

“24,000-year-old individual (MA-1), from Mal’ta in south-central Siberia. The MA-1 mitochondrial genome belongs to haplogroup U, which has also been found at high frequency among Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic European hunter-gatherers and the Y chromosome of MA-1 is basal to modern-day western Eurasians and near the root of most Native American lineages. Similarly, we find autosomal evidence that MA-1 is basal to modern-day western Eurasians and genetically closely related to modern-day Native Americans, with no close affinity to east Asians.” ref

“This suggests that populations related to contemporary western Eurasians had a more north-easterly distribution 24,000 years ago than commonly thought. Furthermore, we estimate that 14 to 38% of Native American ancestry may originate through gene flow from this ancient population. This is likely to have occurred after the divergence of Native American ancestors from east Asian ancestors, but before the diversification of Native American populations in the New World.” ref

“Gene flow from the MA-1 lineage into Native American ancestors could explain why several crania from the First Americans have been reported as bearing morphological characteristics that do not resemble those of east Asians. Sequencing of another south-central Siberian, Afontova Gora-2 dating to approximately 17,000 years ago, revealed similar autosomal genetic signatures as MA-1, suggesting that the region was continuously occupied by humans throughout the Last Glacial Maximum. And findings reveal that western Eurasian genetic signatures in modern-day Native Americans derive not only from post-Columbian admixture, as commonly thought, but also from a mixed ancestry of the First Americans.” ref

“Haplogroup P1 (P-M45), the immediate ancestor of Haplogroup R, likely emerged in Southeast Asia. The SNP M207, which defines Haplogroup R, is believed to have arisen about 27,000 years ago. Only one confirmed example of basal R* has been found, in 24,000 year old remains, known as MA1, found at Mal’ta–Buret’ culture near Lake Baikal in Siberia. R-M207 was found in one out of 132 males from the Kyrgyz people of East Kyrgyzstan who are a Turkic ethnic group native to Central Asia, primarily Kyrgyzstan bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west and southwest, Tajikistan to the southwest, and China to the east. It is possible that neither of the primary branches of R-M207, namely R1 (R-M173) and R2 (R-M479) still exist in their basal, undivergent forms, i.e. R1* and R2*. Despite the rarity of R* and R1*, the relatively rapid expansion – geographically and numerically – of subclades from R1 in particular, has often been noted: both R1a and R1b comprise young, star-like expansions.” ref

‘The earliest publications on R1b described their ancestor R1, entering Europe from central Asia during a warm period about 30,000 – 40,000 years ago. The last ice age forced R1 to split and take refuge south in Iberia and the Balkans. Time and separation gave us the mutations R1b in Iberia and R1a in the Balkans. That split is roughly what we see today in those regions. That’s clean and simple. The real world is much more complex. R1b and R1a were not alone in Europe. Their interactions with the other major European haplogroups- E, G, I, J and N has to be taken into consideration.” ref

“We know that modern humans survived and flourished in the Iberian refuge during the end of the last ice age, based on mitochondrial DNA studies. [Could someone please run some y-DNA tests on those samples?] The tribes in western Europe, whoever they were, had a 1,000 to 2,500 year head start over the tribes in central and eastern Europe on repopulating the continent. The ice sheets melted and retreated earlier on the west coast than in the rest of Europe. This gave the inhabitants of the Iberian refuge an advantage – a “first-mover” advantage gained by being the first to move north. These first-movers gained a land-monopoly. A tribe with a first-mover advantage and over a 1,000 year head start should have been hard to displace from western Europe. In other anthropological situations, those original inhabitants are forced into niche locations by invading populations, but very rarely are displaced completely. What we see on the west coast of Europe, is a very strong R1b presence and no niche haplogroups of a significant age.” ref

“Haplogroup R1 is very common throughout all of Eurasia except East Asia and Southeast Asia. Its distribution is believed to be associated with the re-settlement of Eurasia following the last glacial maximum. Its main subgroups are R1a and R1b.” ref

“The split of R1a (M420) is computed to ca 25,000 years ago or roughly the last glacial maximum. A large study using 16,244 individuals from over 126 populations from across Eurasia, concluded that there was compelling evidence that “the initial episodes of haplogroup R1a diversification likely occurred in the vicinity of present-day Iran.” ref

“A subclade of haplogroup R1a (especially haplogroup R1a1) is the most common haplogroup in large parts of South Asia, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, Western China, and South Siberia. One subclade of haplogroup R1b (especially R1b1a2), is the most common haplogroup in Western Europe and Bashkortostan which is a federal subject of Russia. It is located between the Volga River and the Ural Mountains.” ref

Haplogroup R possible time of origin about 27,000 years in Central Asia, South Asia, or Siberia:

- Mal’ta–Buret’ culture (24,000-15,000 years ago)

- Afontova Gora culture (21,000-12,000 years ago)

- Trialetian culture (16,000–8000 years ago)

- Samara culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Khvalynsk culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Afanasievo culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Yamna/Yamnaya Culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Andronovo culture (4,000–2,900 years ago) ref

“Sequencing of another south-central Siberian, Afontova Gora-2 dating to approximately 17,000 years ago, revealed similar autosomal genetic signatures as MA-1, suggesting that the region was continuously occupied by humans throughout the Last Glacial Maximum.” ref

“Afontova Gora is a Late Upper Paleolithic Siberian complex of archaeological sites located on the left bank of the Yenisei River near the city of Krasnoyarsk, Russia. Afontova Gora has cultural and genetic links to the people from Mal’ta-Buret’. Afontova Gora II consists of 7 layers. Layer 3 from Afontova Gora II is the most significant: the layer produced the largest amount of cultural artefacts and is the layer where the human fossil remains were discovered. Over 20,000 artefacts were discovered at layer 3: this layer produced over 450 tools and over 250 osseous artefacts (bone, antler, ivory). The human fossil remains of Afontova Gora 2 discovered at Afontova Gora II dated to around 16,930-16,490 years ago. The individual showed close genetic affinities to Mal’ta 1 (Mal’ta boy). Afontova Gora 2 also showed more genetic affinity for the Karitiana people versus Han Chinese. Moreover, human fossil remains consisting of five lower teeth of a young girl (Afontova Gora 3) estimated to be around 14–15 years old is dated to around 16,130-15,749 BC (14,710±60 BP).” ref

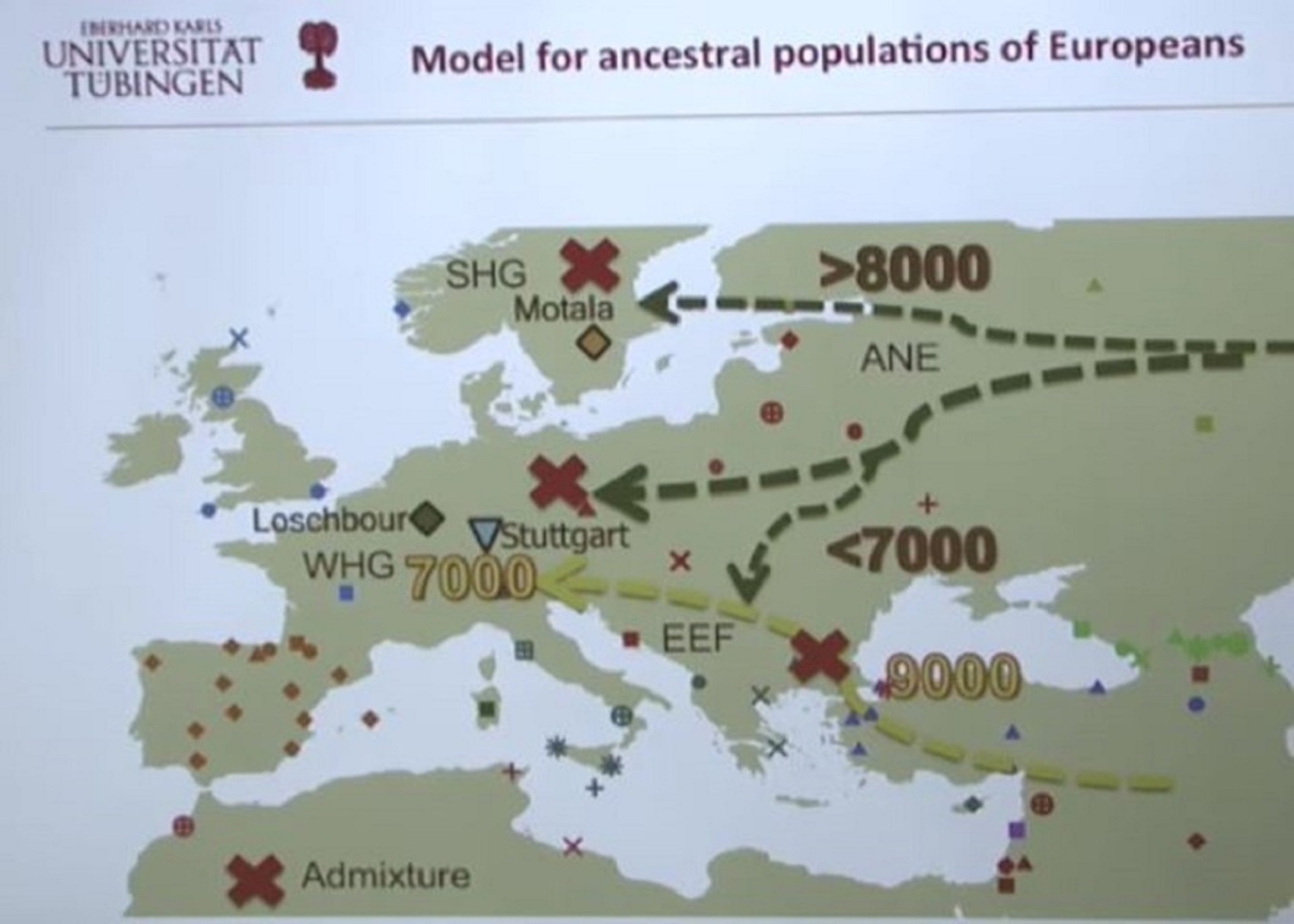

“The great majority of European ancestry derives from three distinct sources. 177 First, there is “hunter-gatherer-related” ancestry that is more closely related 178 to Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from Europe than to any other population, and that can be 179 further subdivided into “Eastern” (EHG) and “Western” (WHG) hunter-gatherer-related ancestry. 7 180 Second, there is “NW Anatolian Neolithic-related” ancestry related to the Neolithic farmers of northwest Anatolia and tightly linked to the appearance of agriculture.9,10 181 182 The third source, “steppe-related” ancestry, appears in Western Europe during the Late 183 Neolithic to Bronze Age transition and is ultimately derived from a population related to Yamnaya steppe pastoralists. 184 Steppe-related ancestry itself can be modeled as a mixture of 185 EHG-related ancestry, and ancestry related to Upper Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers of the Caucasus (CHG) and the first farmers of northern Iran.” ref

Map showing Afontova Gora (27) and Mal’ta (29), both circled.

“Afontova Gora is an important site has cultural ties with Mal’ta and Buret’, hundreds of kilometres to the south east. It is on a north flowing river, the Yenisei, Енисея.

The settlement is dated to 20,000 – 18,000 years ago.” ref

Haplogroup R1b (R-M343), is the most frequently occurring paternal lineage in Western Europe, as well as some parts of Russia (e.g. the Bashkir minority) and Central Africa (e.g. Chad and Cameroon). The clade is also present at lower frequencies throughout Eastern Europe, Western Asia, as well as parts of North Africa and Central Asia. R1b also reaches high frequencies in the Americas and Australasia, due largely to immigration from Western Europe. There is an ongoing debate regarding the origins of R1b subclades found at significant levels among some indigenous peoples of the Americas, such as speakers of Algic languages in central Canada. It has been found in Bahrain, Bhutan, Ladakh, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Western China. The point of origin of R1b is thought to lie in Western Eurasia, most likely in Western Asia.” ref

“Within haplogroup R1b, there are extremely large subclades, R-U106 and R-P312. While these subclades are important to the overall picture, their size leads tonoise in the analysis of an R1b origin. It isthe minority branches of R1b (R-L278*, R-V88, R-M73*, R-YSC0000072/PF6426 andR-L23-) that provide the resolution required.(While the data from R-V88 supports anIberian origin, and along the Western Atlantic coast, with R-L278 origins south of the Pyrenees. And the Pyrenees, Spanish Pirineos, French Pyrénées, Catalan Pireneus, mountain chain of southwestern Europe that consists of flat-topped massifs and folded linear ranges. It stretches from the shores of the Mediterranean Sea on the east to the Bay of Biscay on the Atlantic Oceanon the west. The Pyrenees form a high wall between France and Spain that has played a significant role in the history of both countries and of Europe as a whole.” ref, ref

“R1b-V88 originated in Europe about 12 000 years ago and crossed to North Africa by about 8000 years ago; it may formerly have been common in southern Europe, where it has since been replaced by waves of other haplogroups, leaving remnant subclades almost excusively in Sardinia. It first radiated within Africa likely between 7 and 8 000 years ago – at the same time as trans-Saharan expansions within the unrelated haplogroups E-M2 and A-M13 – possibly due to population growth allowed by humid conditions and the adoption of livestock herding in the Sahara. R1b-V1589, the main subclade within R1b-V88, underwent a further expansion around 5500 years ago, likely in the Lake Chad Basin region, from which some lines recrossed the Sahara to North Africa.” ref

“The majority of modern R1b and R1a would have expanded from the Caspian Sea along with the Indo-European languages. And genetic studies support the Kurgan hypothesis regarding the Proto-Indo-European homeland. According to those studies, haplogroups R1b and R1a, now the most common in Europe (R1a is also common in South Asia) would have expanded from the West Eurasian Steppe, along with the Indo-European languages; they also detected an autosomal component present in modern Europeans which was not present in Neolithic Europeans, which would have been introduced with paternal lineages R1b and R1a, as well as Indo-European languages.” ref

The oldest human remains found to carry R1b include:

- Villabruna 1 (individual I9030), found in an Epigravettian culture setting in the Cismon valley (modern Veneto, Italy), who lived circa 14,000 years BP and belonged to R1b-L754,

- numerous individuals from the Mesolithic Iron Gates culture of the central Danube (modern Romania and Serbia), dating from 10,000 to 8,500 BP – most of them falling into R1b-L754;

- two individuals, dating from circa 7,800–6,800 BP, found at the Zvejnieki burial ground, belonging to the Narva culture of the Baltic neolithic, both determined to belong to the R1b-P297 subclade, and;

- the “Samara hunter-gatherer” (I0124/SVP44), who lived approximately 7,500 BP in the Volga River area and carried R1b-L278. ref

“This burial is from the early Mesolithic stage which is proto-Lepenski Vir. Whereas, the general Lepenski Vir, located in Serbia, Mesolithic Iron Gates culture of the Balkans. Around 11,500/9,200–7,900 years ago.” ref,ref, ref

“A particularly important hunter-gatherer population that we report is from the Iron Gates region that straddles the border of present-day Romania and Serbia. This population (Iron_Gates_HG) is represented in our study by 40 individuals from five sites. Modeling Iron Gates hunter-gatherers as a mixture of WHG and EHG (Supplementary Table 3) shows that they are intermediate between WHG (~85%) and EHG (~15%). However, this qpAdm model 244 does not fit well (p=0.0003, Supplementary table 3) and the Iron Gates hunter-gatherers carry mitochondrial haplogroup K1 (7/40) as well as other subclades of haplogroups U (32/40) and H (1/40). This contrasts with WHG, EHG and Scandinavian hunter-gatherers who almost all carry haplogroups U5 or U2. One interpretation is that the Iron Gates hunter-gatherers have ancestry that is not present in either WHG or EHG. Possible scenarios include genetic contact between the ancestors of the Iron Gates population and Anatolia, or that the Iron Gates population is related to the source population from which the WHG split during a reexpansion into Europe from the Southeast after the Last Glacial Maximum.” ref

“A notable finding from the Iron Gates concerns the four individuals from the site of Lepenski Vir, two of whom (I4665 & I5405, 8,200-7,600 years ago), have entirely NW Anatolian Neolithicrelated ancestry. Strontium and Nitrogen isotope data indicate that both these individuals were migrants from outside the Iron Gates, and ate a primarily terrestrial diet. A third individual (I4666, 8,070 years ago) has a mixture of NW Anatolian Neolithic-related and hunter-gatherer-related ancestry and ate a primarily aquatic diet, while a fourth, probably earlier, individual (I5407) had entirely hunter-gatherer-related ancestry. We also identify one individual from Padina (I5232), dated to 7,950 years ago that had a mixture of NW Anatolian Neolithic-related and hunter-gatherer-related ancestry. These results demonstrate that the Iron Gates was a region of interaction between groups distinct in both ancestry and subsistence strategy.” ref

“R-M173, also known as R1, has been common throughout Europe and South Asia since pre-history. It is the second most common haplogroup in Indigenous peoples of the Americas following haplogroup Q-M242, especially in the Algonquian peoples of Canada and the United States. There is a great similarity of many R-M173 subclades found in North America to those found in Siberia, suggesting prehistoric immigration from Asia and/or Beringia.” ref

“The Dyuktai culture was defined by Yuri Mochanov in 1967, following the Dyuktai Cave discovery on the Aldan River, Yakutia. In the Pleistocene deposits, at a 2-m depth, lithic tools and Pleistocene animal bones were exposed, radiocarbon dated to 14,000-12,000 BP. Further research in Yakutia resulted in the discovery of other Dyuktai culture sites on the Aldan, Olenyok, and Indigirka rivers. The sites are located along the banks and at the estuary capes of smaller tributaries. The Dyuktai culture tool assemblage is represented by choppers, wedge-shaped cores, microblades, end scrapers on blades, oval bifaces, points, as well as angle, dihedral, and transversal burins on flakes and blades. The emergence of the Dyuktai culture defines the time when the microblade technique first appeared in northeast Asia. Judging by bones found in the same layers with tools, the Dyuktai people used to hunt mammoth, wooly rhino, bison, horse, reindeer, moose, and snow ram. Fishing tools have not been excavated, although a few fish bones were found in the Dyuktai cave Pleistocene cultural levels.” ref

“The cultural materials at the sites were concentrated around small hearths with no special lining. The question of whether the bow and arrow existed in the Dyuktai culture has so far been open, because just a few stone points small enough to be used on arrows were found. Yu. Mochanov associates the Dyuktai culture emergence in Yakutia with the bifacial Paleolithic cultures coming from the southern Urals, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and northern China. From Dyuktai materials of some stratified sites, Yu. Mochanov dated the Dyuktai culture to 35,000-11,500 BP. This date was broadly discussed by scholars within the debates on the question of the microblade industry emergence in Siberia and aroused some serious objections. The dates exceeding 25,000 BP are deemed to be erroneous, so the microblade technique appeared in Siberia no earlier than 25,000 BP. A. Derevyanko supposes that the origin of the Dyuktai culture can be found on the Selemja River, tributary of the Amur, in the Selemja culture, by 25000-11000 BP.” ref

“The Dyuktai tradition was spread over all of northeast Asia. In Kamchatka, it has been represented by the materials of the Late Ushki Upper Paleolithic culture in levels V and VI of the Ushki I-V sites. It determines the latest period in the Dyuktai tradition development, 10,800-8800 BP. Its general outlook differs significantly from that of the Dyuktai culture in Yakutia. The sites are located on the bank of a small lake in the valley of Kamchatka’s largest river in its medium flow. The exposed dwellings are represented by surface, teepee-type, 8-16 m2, and semi-subterranean with the corridor, 10-44 m2, with circular stone hearths in the center. Several inhabited horizons exposed on the site and numerous stone tools, burials, and caches found in the dwellings testify to its long-term use, perhaps even as a winter camp.” ref

“Judging by tooth remains in the cultural level, its people hunted for reindeer, bison, and moose. Burned salmon and other fish bones found in the hearths as well as the sites location at the spawning lake confirm the existence of fishing. The tool assemblage of the Ushki culture consisted of small- and medium-sized bifacial projectile points; end scrapers; angle, transversal, and dihedral burins; semilunar and oval bifaces; end scrapers on blades and flakes; microblades and wedge-shaped cores; and grooved pumice shaft straighteners. Ornaments were represented by oval pendants. In the dwellings, a pair and a group (as many as five human bodies) children’s burial were found. The corpses in both graves were in a flexed position and covered with ochre. The bottom of the pair-burial grave was covered with lemming incisors; the group burial was covered with a large animal’s scapula. The rich burial inventory included arrow and spear points, leaf-shaped knives, grinding plates, grooved pumice shaft.” ref

“To help with geography, the following google map shows the following locations: A=the Altai Republic, in Russia, B=Mal’ta, the location of the 24,000-year-old skeletal remains and C=Lake Baikal, the region from where the Native American population originated in Asia.” ref

The genome from Ust’-Ishim (Main Semi-Related Ancestor DNA Branch)

“The Ust’-Ishim DNA was from northern Siberia that dates to 45,000 years ago, from the bank of the Irtysh River, which is in the Siberian plain near Omsk. Its source lies in the Mongolian Altai in Dzungaria (the northern part of Xinjiang, China) close to the border with Mongolia. The Ob-Irtysh system forms a major drainage basin in Asia, encompassing most of Western Siberia and the Altai Mountains.” ref, ref

“Ust’-Ishim is more similar to genomes of non-Africans than it is to sub-Saharan African genomes. Ust’-Ishim is not more like the Mal’ta genome than it is like any other genomes of Asians or Native Americans. It is not like any living population of Asians or Native Americans more than any other.” ref

Link to Enlarge Population history inferences

“The MA-1 sequence compare to that of another 40,000-year-old individual from Tianyuan Cave, China whose genome has been partially sequenced. This Chinese individual has been shown to be ancestral to both modern-day Asians and Native Americans. This comparison was particularly useful, because it showed that MA-1 is not closely related to the Tianyuan Cave individual, and is more closely related to Native Americans. This means that MA-1’s line and Tianyuan Cave’s line had not yet met and admixed into the population that would become the Native Americans. That occurred sometime later than 24,000 years ago and probably before crossing Beringia into North America sometime between about 18,000 and 20,000 years ago.” ref

“A basal Ancestral Native American (ANA) lineage. This lineage was formed by admixture of early East Asian and Ancient North Eurasian lineages prior to the Last Glacial Maximum, ca. 36–25 kya. Basal ANA diverged into an “Ancient Beringian” (AB) lineage at ca. 20 kya. The non-AB lineage further diverged into “Northern Native American” (NNA) and “Southern Native American” (SNA) lineages between about 17.5 and 14.6 kya. Most pre-Columbian lineages are derived from NNA and SNA, except for the American Arctic, where there is evidence of later (after 10kya) admixture from Paleo-Siberian lineages.” ref

“DNA of a 12,500+-year-old infant from Montana was sequenced from a skeleton referred to as Anzick-1, found in close association with several Clovis artifacts. Comparisons showed strong affinities with DNA from Siberian sites, and virtually ruled out that particular individual had any close affinity with European sources (the “Solutrean hypothesis“). The DNA also showed strong affinities with all existing Amerindian populations, which indicated that all of them derive from an ancient population that lived in or near Siberia, the Upper Palaeolithic Mal’ta population.” ref

“Native Americans descend of at least three main migrant waves from East Asia. Most of it is traced back to a single ancestral population, called ‘First Americans’. However, those who speak Inuit languages from the Arctic inherited almost half of their ancestry from a second East Asian migrant wave. And those who speak Na-dene, on the other hand, inherited a tenth of their ancestry from a third migrant wave. The initial settling of the Americas was followed by a rapid expansion southwards, by the coast, with little gene flow later, especially in South America. One exception to this are the Chibcha speakers, whose ancestry comes from both North and South America.” ref

“Linguistic studies have backed up genetic studies, with ancient patterns having been found between the languages spoken in Siberia and those spoken in the Americas. Two 2015 autosomal DNA genetic studies confirmed the Siberian origins of the Natives of the Americas. However, an ancient signal of shared ancestry with Australasians (Natives of Australia, Melanesia, and the Andaman Islands) was detected among the Natives of the Amazon region. The migration coming out of Siberia would have happened 23,000 years ago.” ref

“R1 is very common throughout all of Eurasia except East Asia and Southeast Asia. R1 (M173) is found predominantly in North American groups like the Ojibwe (50-79%), Seminole (50%), Sioux(50%), Cherokee (47%), Dogrib (40%), and Tohono O’odham (Papago) (38%). Skeletal remain of a south-central Siberian child carrying R* y-dna (Mal’ta boy-1) “is basal to modern-day western Eurasians and genetically closely related to modern-day Amerindians, with no close affinity to east Asians. This suggests that populations related to contemporary western Eurasians had a more north-easterly distribution 24,000 years ago than commonly thought.” Sequencing of another south-central Siberian (Afontova Gora-2) revealed that “western Eurasian genetic signatures in modern-day Amerindians derive not only from post-Columbian admixture, as commonly thought, but also from a mixed ancestry of the First Americans.” It is further theorized if “Mal’ta might be a missing link, a representative of the Asian population that admixed both into Europeans and Native Americans.” ref

Swan Point 15,000 – 14,200 years ago

“It is significant that Swan Point is not only the oldest site (radiocarbon dated between circa 15,000 and 14,200 cal. BP), but also contains microblade technology throughout the multiple components. This makes the site comparable with the other Tanana Valley sites, yet distinctive- a position that may be advantageous for testing theories on site formation, group mobility, and landscape exploitation patterns.” ref

“Microblade technology, exemplified by the Dyuktai culture of Siberia, has been seen as linked to early cultures in Alaska, e.g., Denali complex and American Paleoarctic tradition. Clovis-like characteristics (e.g., blades, bifaces, scrapers and gravers) found in the Nenana complex, have been argued as evidence for a regional presence of the Paleoindian tradition. Swan Point appears to have aspects of both of these complexes at the earliest levels, as well as multiple occupation levels that range from the terminal Pleistocene to the late Holocene. Swan Point has the potential to provide information on past life ways that would be of interest locally, regionally, and hemispherically.” ref

“Evidence of charcoal that has been radiocarbon dated to approximately 14,000 years ago. The charcoal dating makes this the oldest known site in the Tanana River Valley. The mammoth artifacts found in the Latest Pleistocene zone date to approximately 14,000 cal years ago. With no other mammoth remains found beyond tusk ivory, it is assumed that the people who lived on the site scavenged the ivory rather than hunting the mammoth themselves.” ref

Terminal Pleistocene

“This is the oldest cultural level from approximately 11,660 cal – 10,000 cal years ago. Artifacts found at this level include worked mammoth tusk fragments, microblades, microblade core preparation flakes, blades, dihedral burins, red ochre, pebble hammers, and quartz hammer tools and choppers. The microblades found at this zone are significant as they are the oldest securely dated microblades in eastern Beringia.” ref

Latest Pleistocene

“A variety of bifacial points were found at this level, which dates to approximately 10,230 ± 80 cal years ago, including lanceolate points with convex to straight bases, along with graver spurs, quartz pebble choppers and hammers. The mammoth artifacts found in the Latest Pleistocene zone date to approximately 14,000 cal years ago. With no other mammoth remains found beyond tusk ivory, it is assumed that the people who lived on the site scavenged the ivory rather than hunting the mammoth themselves.” ref

Migration map of Y-haplogroup R1b from the Paleolithic to the end of the Bronze Age (c. 1000BCE) ref

Paleolithic mammoth hunters

“Haplogroup R* originated in North Asia just before the Last Glacial Maximum (26,500-19,000 years ago). This haplogroup has been identified in the remains of a 24,000 year-old boy from the Altai region, in south-central Siberia. This individual belonged to a tribe of mammoth hunters that may have roamed across Siberia and parts of Europe during the Paleolithic. Autosomally this Paleolithic population appears to have contributed mostly to the ancestry of modern Europeans and South Asians, the two regions where haplogroup R also happens to be the most common nowadays (R1b in Western Europe, R1a in Eastern Europe, Central and South Asia, and R2 in South Asia).” ref

“The oldest forms of R1b (M343, P25, L389) are found dispersed at very low frequencies from Western Europe to India, a vast region where could have roamed the nomadic R1b hunter-gatherers during the Ice Age. The three main branches of R1b1 (R1b1a, R1b1b, R1b1c) all seem to have stemmed from the Middle East. The southern branch, R1b1c (V88), is found mostly in the Levant and Africa. The northern branch, R1b1a (P297), seems to have originated around the Caucasus, eastern Anatolia or northern Mesopotamia, then to have crossed over the Caucasus, from where they would have invaded Europe and Central Asia. R1b1b (M335) has only been found in Anatolia.” ref

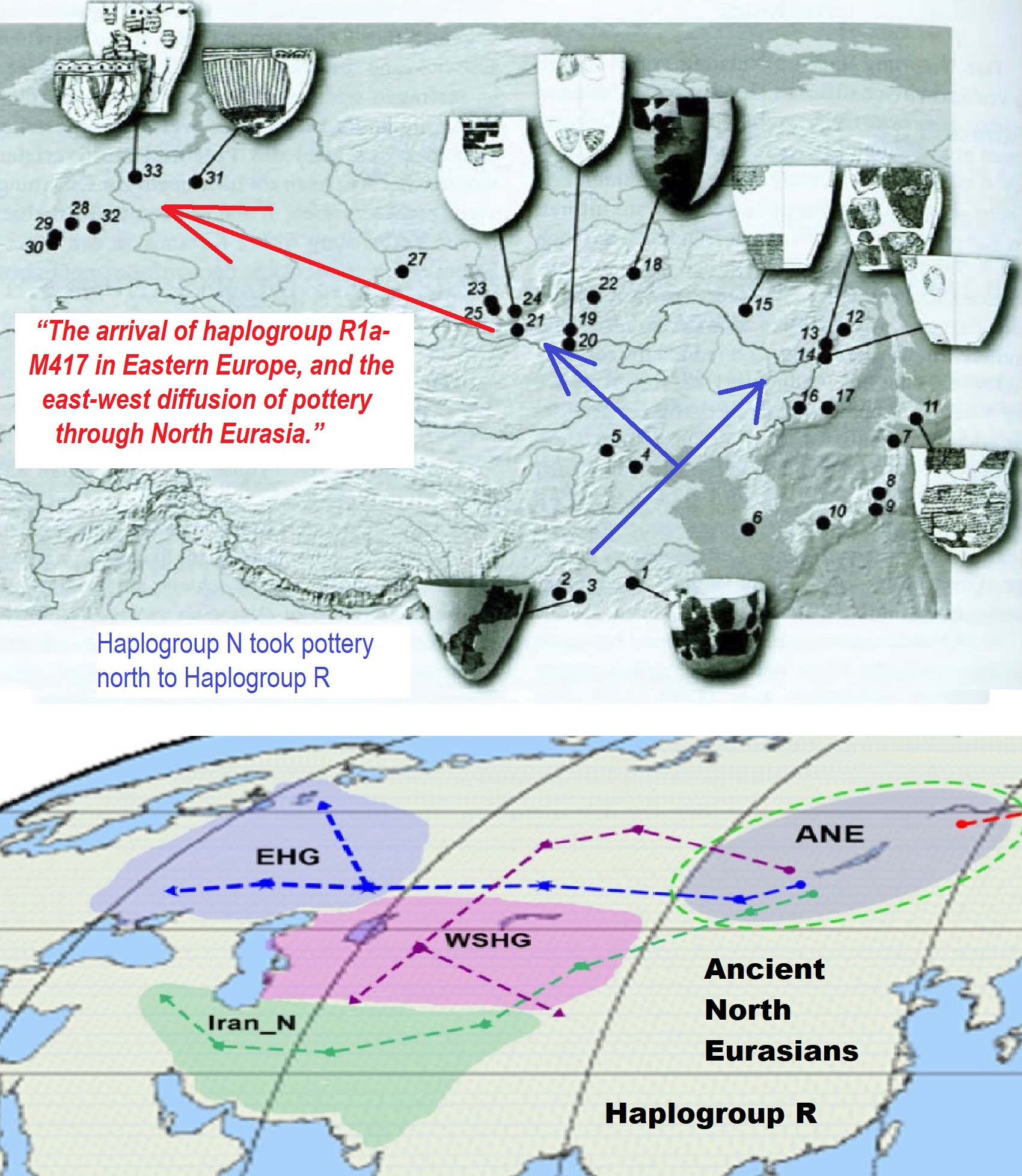

“The arrival of haplogroup R1a-M417 in Eastern Europe, and the east-west diffusion of pottery through North Eurasia.” https://indo-european.eu/2018/02/the-arrival-of-haplogroup-r1a-m417-in-eastern-europe-and-the-east-west-diffusion-of-pottery-through-north-eurasia/

Ancient North Eurasian https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_North_Eurasian

Ancient North Eurasian/Mal’ta–Buret’ culture haplogroup R* https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mal%27ta%E2%80%93Buret%27_culture

“The arrival of haplogroup R1a-M417 in Eastern Europe, and the east-west diffusion of pottery through North Eurasia.” ref

R-M417 (R1a1a1)

“R1a1a1 (R-M417) is the most widely found subclade, in two variations which are found respectively in Europe (R1a1a1b1 (R-Z282) ([R1a1a1a*] (R-Z282) and Central and South Asia (R1a1a1b2 (R-Z93) ([R1a1a2*] (R-Z93).” ref

R-Z282 (R1a1a1b1a) (Eastern Europe)

“This large subclade appears to encompass most of the R1a1a found in Europe.

- R1a1a1b1a [R1a1a1a*] (R-Z282*) occurs in northern Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia at a frequency of c. 20%.

- R1a1a1b1a3 [R1a1a1a1] (R-Z284) occurs in Northwest Europe and peaks at c. 20% in Norway.

- R1a1a1c (M64.2, M87, M204) is apparently rare: it was found in 1 of 117 males typed in southern Iran.” ref

R1a1a1b2 (R-Z93) (Asia)

“This large subclade appears to encompass most of the R1a1a found in Asia, being related to Indo-European migrations (including Scythians, Indo-Aryan migrations, and so on).

- R-Z93* or R1a1a1b2* (R1a1a2* in Underhill (2014)) is most common (>30%) in the South Siberian Altai region of Russia, cropping up in Kyrgyzstan (6%) and in all Iranian populations (1-8%).

- R-Z2125 occurs at highest frequencies in Kyrgyzstan and in Afghan Pashtuns (>40%). At a frequency of >10%, it is also observed in other Afghan ethnic groups and in some populations in the Caucasus and Iran.

- R-M434 is a subclade of Z2125. It was detected in 14 people (out of 3667 people tested), all in a restricted geographical range from Pakistan to Oman. This likely reflects a recent mutation event in Pakistan.

- R-M560 is very rare and was only observed in four samples: two Burushaski speakers (north Pakistan), one Hazara (Afghanistan), and one Iranian Azerbaijani.

- R-M780 occurs at high frequency in South Asia: India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the Himalayas. The group also occurs at >3% in some Iranian populations and is present at >30% in Roma from Croatia and Hungary.” ref

R-M458 (R1a1a1b1a1)

“R-M458 is a mainly Slavic SNP, characterized by its own mutation, and was first called cluster N. Underhill et al. (2009) found it to be present in modern European populations roughly between the Rhine catchment and the Ural Mountains and traced it to “a founder effect that … falls into the early Holocene period, 7.9±2.6 KYA.” M458 was found in one skeleton from a 14th-century grave field in Usedom, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. The paper by Underhill et al. (2009) also reports a surprisingly high frequency of M458 in some Northern Caucasian populations (for example 27.5% among Karachays and 23.5% among Balkars, 7.8% among Karanogays and 3.4% among Abazas).” ref

Pic ref

Ancient Human Genomes…Present-Day Europeans – Johannes Krause (Video)

Ancient North Eurasian (ANE)

Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG)

Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG)

Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (SHG)

Early European Farmers (EEF)

A quick look at the Genetic history of Europe

“The most significant recent dispersal of modern humans from Africa gave rise to an undifferentiated “non-African” lineage by some 70,000-50,000 years ago. By about 50–40 ka a basal West Eurasian lineage had emerged, as had a separate East Asian lineage. Both basal East and West Eurasians acquired Neanderthal admixture in Europe and Asia. European early modern humans (EEMH) lineages between 40,000-26,000 years ago (Aurignacian) were still part of a large Western Eurasian “meta-population”, related to Central and Western Asian populations. Divergence into genetically distinct sub-populations within Western Eurasia is a result of increased selection pressure and founder effects during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, Gravettian). By the end of the LGM, after 20,000 years ago, A Western European lineage, dubbed West European Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) emerges from the Solutrean refugium during the European Mesolithic. These Mesolithic hunter-gatherer cultures are substantially replaced in the Neolithic Revolution by the arrival of Early European Farmers (EEF) lineages derived from Mesolithic populations of West Asia (Anatolia and the Caucasus). In the European Bronze Age, there were again substantial population replacements in parts of Europe by the intrusion of Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) lineages from the Pontic–Caspian steppes. These Bronze Age population replacements are associated with the Beaker culture archaeologically and with the Indo-European expansion linguistically.” ref

“As a result of the population movements during the Mesolithic to Bronze Age, modern European populations are distinguished by differences in WHG, EEF, and ANE ancestry. Admixture rates varied geographically; in the late Neolithic, WHG ancestry in farmers in Hungary was at around 10%, in Germany around 25%, and in Iberia as high as 50%. The contribution of EEF is more significant in Mediterranean Europe, and declines towards northern and northeastern Europe, where WHG ancestry is stronger; the Sardinians are considered to be the closest European group to the population of the EEF. ANE ancestry is found throughout Europe, with a maximum of about 20% found in Baltic people and Finns. Ethnogenesis of the modern ethnic groups of Europe in the historical period is associated with numerous admixture events, primarily those associated with the Roman, Germanic, Norse, Slavic, Berber, Arab and Turkish expansions. Research into the genetic history of Europe became possible in the second half of the 20th century, but did not yield results with a high resolution before the 1990s. In the 1990s, preliminary results became possible, but they remained mostly limited to studies of mitochondrial and Y-chromosomal lineages. Autosomal DNA became more easily accessible in the 2000s, and since the mid-2010s, results of previously unattainable resolution, many of them based on full-genome analysis of ancient DNA, have been published at an accelerated pace.” ref

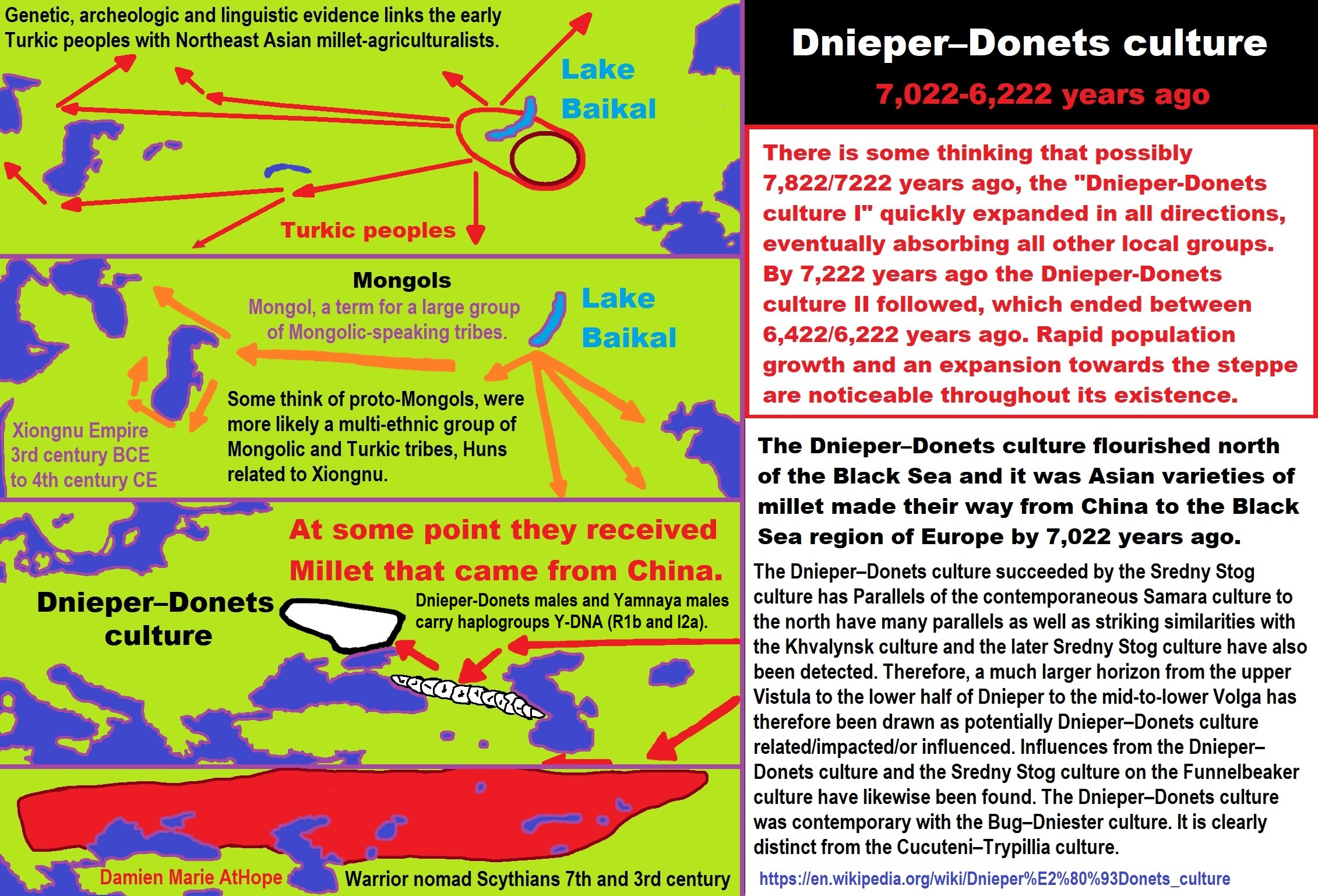

“Asian varieties of millet made their way from China to the Black Sea region of Europe by 5000 BCE or 7,000 years ago.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Millet

Origins of ‘Transeurasian’ languages traced to Neolithic millet farmers in north-eastern China about 9,000 years ago

“A study combining linguistic, genetic, and archaeological evidence has traced the origins of a family of languages including modern Japanese, Korean, Turkish and Mongolian and the people who speak them to millet farmers who inhabited a region in north-eastern China about 9,000 years ago. The findings outlined on Wednesday document a shared genetic ancestry for the hundreds of millions of people who speak what the researchers call Transeurasian languages across an area stretching more than 5,000 miles (8,000km).” ref

“Millet was an important early crop as hunter-gatherers transitioned to an agricultural lifestyle. There are 98 Transeurasian languages, including Korean, Japanese, and various Turkic languages in parts of Europe, Anatolia, Central Asia, and Siberia, various Mongolic languages, and various Tungusic languages in Manchuria and Siberia. This language family’s beginnings were traced to Neolithic millet farmers in the Liao River valley, an area encompassing parts of the Chinese provinces of Liaoning and Jilin and the region of Inner Mongolia. As these farmers moved across north-eastern Asia over thousands of years, the descendant languages spread north and west into Siberia and the steppes and east into the Korean peninsula and over the sea to the Japanese archipelago.” ref

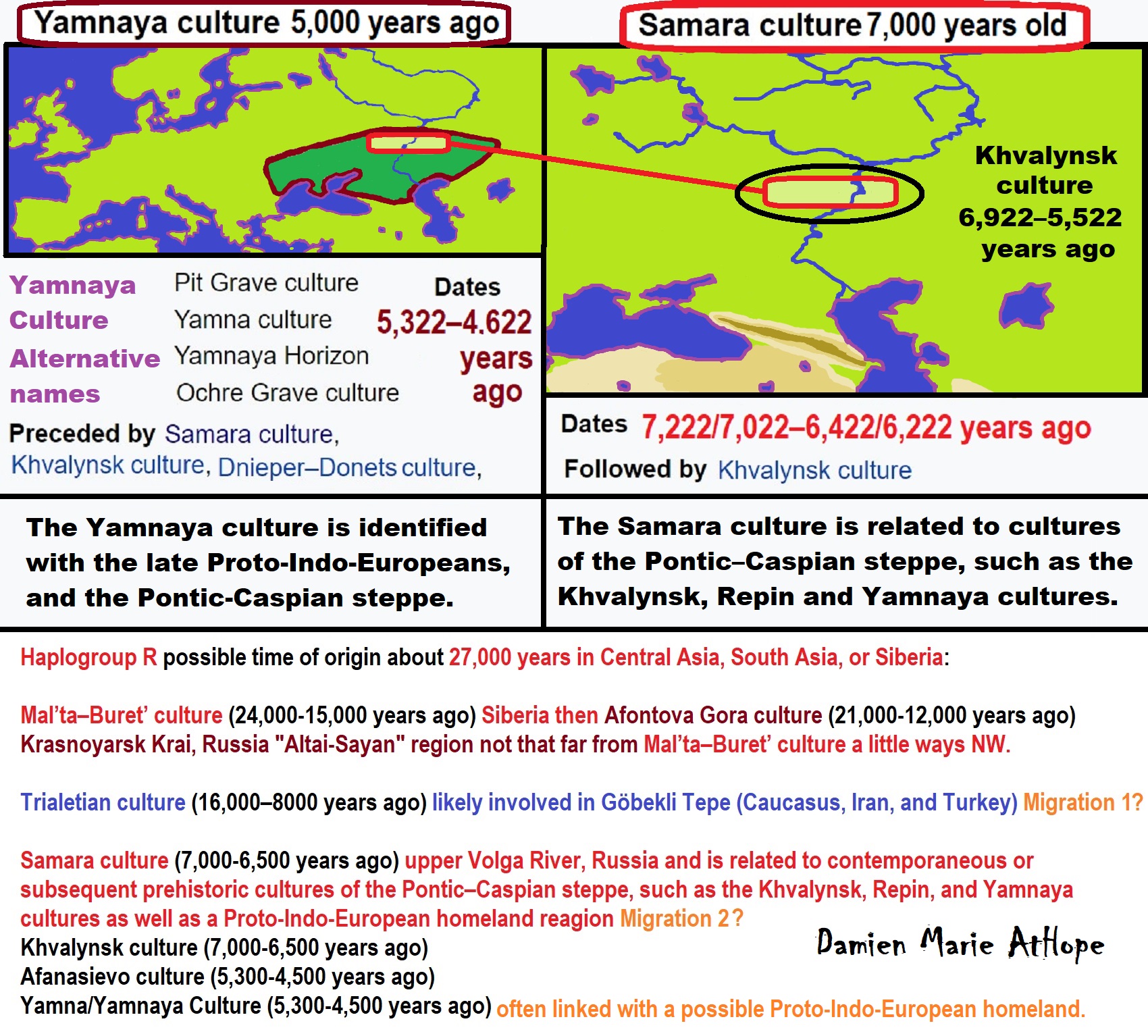

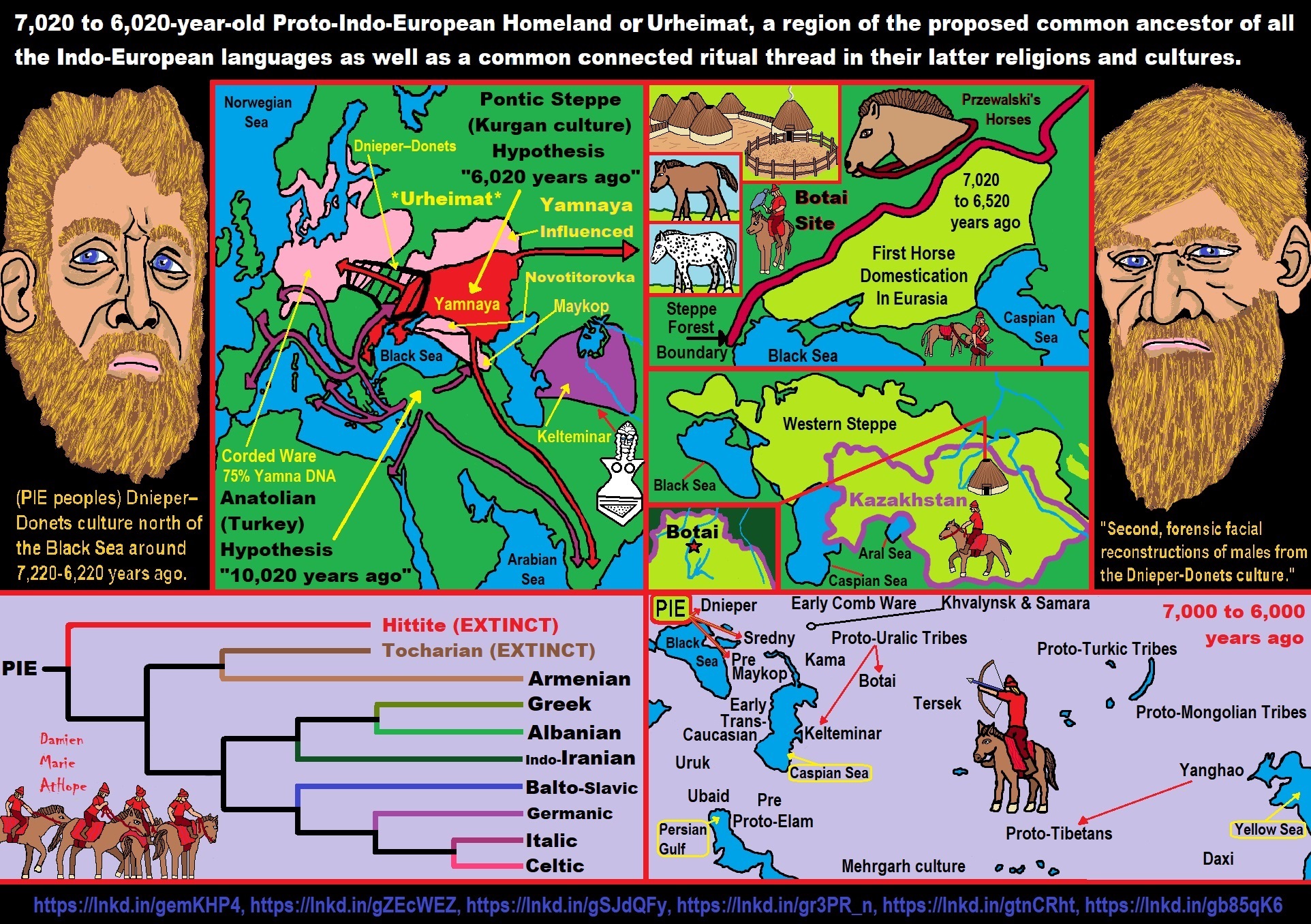

Samara culture (7,000-6,500 years ago) upper Volga River, Russia, and is related to contemporaneous or subsequent prehistoric cultures of the Pontic–Caspian steppe, such as the Khvalynsk, Repin, and Yamnaya cultures as well as a Proto-Indo-European homeland region. Migration 2?

Khvalynsk culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

Afanasievo culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

Yamna/Yamnaya Culture (5,300-4,500 years ago) related to the spread of Proto-Indo-European

Samara culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

“The Samara culture was an eneolithic culture of the early 5th millennium BCE at the Samara bend region of the middle Volga, at the northern edge of the steppe zone. It was discovered during archaeological excavations in 1973 near the village of Syezzheye (Съезжее) in Russia. Related sites are Varfolomievka on the Volga (5500 BCE), which was part of the North Caspian culture, and Mykol’ske, on the Dnieper. The later stages of the Samara culture are contemporaneous with its successor culture in the region, the early Khvalynsk culture (4700–3800 BCE), while the archaeological findings seem related to those of the Dniepr-Donets II culture (5200/5000–4400/4200 BCE).” ref

“The valley of the Samara river contains sites from subsequent cultures as well, which are descriptively termed “Samara cultures” or “Samara valley cultures”. Some of these sites are currently under excavation. “The Samara culture” as a proper name, however, is reserved for the early eneolithic of the region.” ref

Pottery and the Samara culture?

“Pottery consists mainly of egg-shaped beakers with pronounced rims. They were not able to stand on a flat surface, suggesting that some method of supporting or carrying must have been in use, perhaps basketry or slings, for which the rims would have been a useful point of support. The carrier slung the pots over the shoulder or onto an animal. Decoration consists of circumferential motifs: lines, bands, zig-zags or wavy lines, incised, stabbed, or impressed with a comb. These patterns are best understood when seen from the top. They appear then to be a solar motif, with the mouth of the pot as the sun. Later developments of this theme show that in fact the sun is being represented.” ref

Samara culture Sacrificial objects

“The culture is characterized by the remains of animal sacrifice, which occur over most of the sites. There is no indisputable evidence of riding, but there were horse burials, the earliest in the Old World.[citation needed] Typically the head and hooves of cattle, sheep, and horses are placed in shallow bowls over the human grave, smothered with ochre. Some have seen the beginning of the horse sacrifice in these remains, but this interpretation has not been more definitely substantiated. We know that the Indo-Europeans sacrificed both animals and people, like many other cultures.” ref

Samara culture Graves

“The graves found are shallow pits for single individuals, but two or three individuals might be placed there. A male buried at Lebyazhinka, only archaeologically dated to 8000-7000 calBCE, and often referred to by scholars of archaeogenetics as the “Samara hunter-gatherer” (a.k.a. I0124; SVP44; M340431), appears to have carried the rare Y-DNA haplogroup R1b1* (R-L278*).” ref

“Some of the graves are covered with a stone cairn or a low earthen mound, the very first predecessor of the kurgan. The later, fully developed kurgan was a hill on which the deceased chief might ascend to the sky god, but whether these early mounds had that significance is doubtful.” ref

“Grave offerings included ornaments depicting horses. The graves also had an overburden of horse remains; it cannot yet be determined decisively if these horses were domesticated and ridden or not, but they were certainly used as a meat-animal. Most controversial are bone plaques of horses or double oxen heads, which were pierced.” ref

“The graves yield well-made daggers of flint and bone, placed at the arm or head of the deceased, one in the grave of a small boy. Weapons in the graves of children are common later. Other weapons are bone spearheads and flint arrowheads. Other carved bone figurines and pendants were found in the graves.” ref

Samara culture Genetics

Further information: Khvalynsk § Archaeogenetics

“Mathieson et al. (2015, 2018) found that a male hunter-gatherer from Lebyanzhinka, Samara Oblast who lived ca. 5650-5540 BCE belonged to Y-haplogroup R1b1a1a and U5a1d.” ref

Yamnaya culture

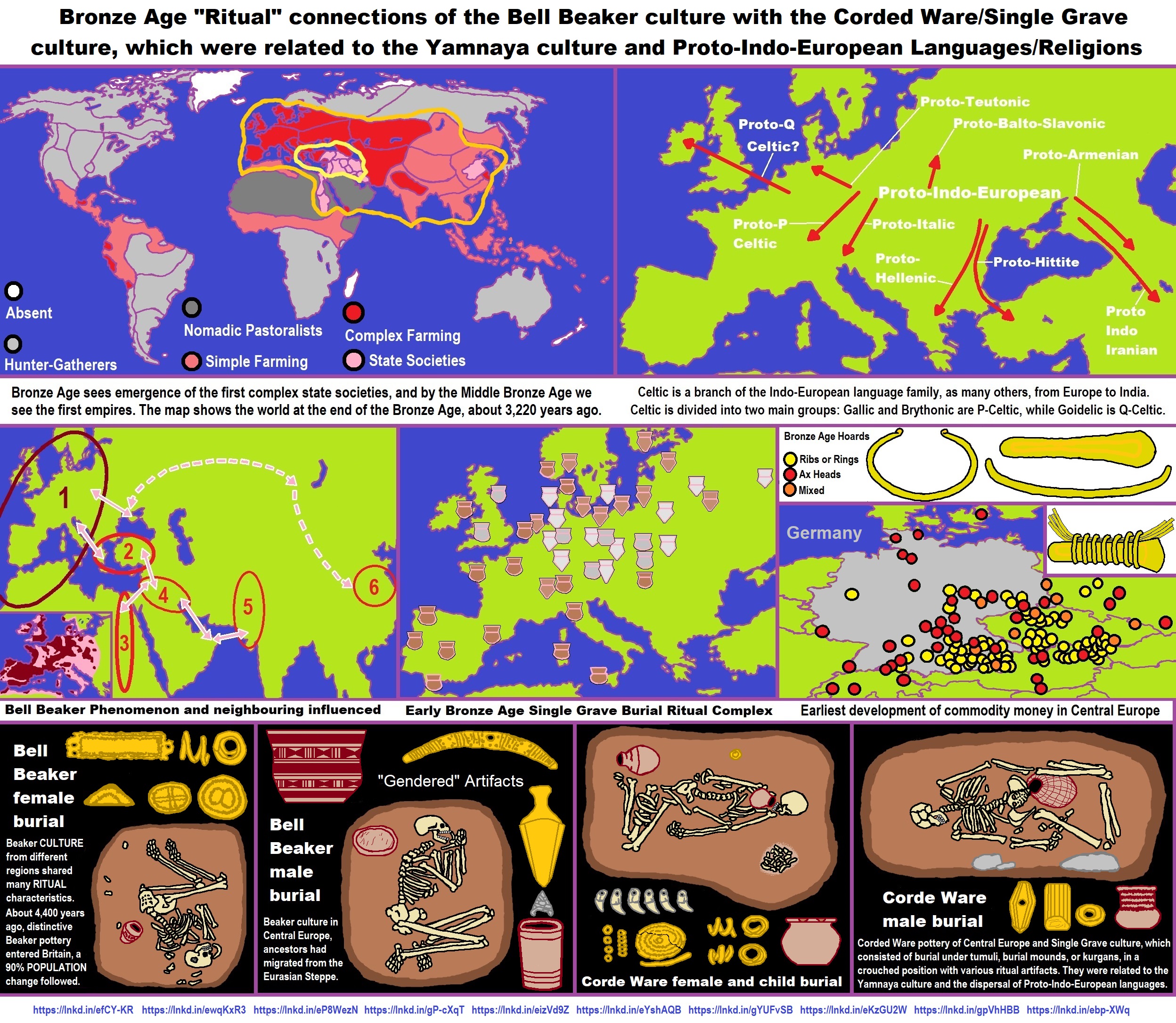

“The Yamnaya culture (Russian: Ямная культура, romanized: Yamnaya kul’tura, Ukrainian: Ямна культура, romanized: Yamna kul’tura lit. ‘culture of pits’), also known as the Yamnaya Horizon, Yamna culture, Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, was a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archaeological culture of the region between the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Ural rivers (the Pontic steppe), dating to 3300–2600 BCE. Its name derives from its characteristic burial tradition: Я́мная (romanization: yamnaya) is a Russian adjective that means ‘related to pits (yama)’, and these people used to bury their dead in tumuli (kurgans) containing simple pit chambers.” ref

“The people of the Yamnaya culture were likely the result of a genetic admixture between the descendants of Eastern European Hunter-Gatherers (EHG) and people related to hunter-gatherers from the Caucasus (CHG), an ancestral component which is often named “Steppe ancestry”, with an additional admixture of up to 18% from Early European Farmers. Their material culture was very similar to the Afanasevo culture, and the populations of both cultures are genetically indistinguishable. They lived primarily as nomads, with a chiefdom system and wheeled carts and wagons that allowed them to manage large herds.” ref

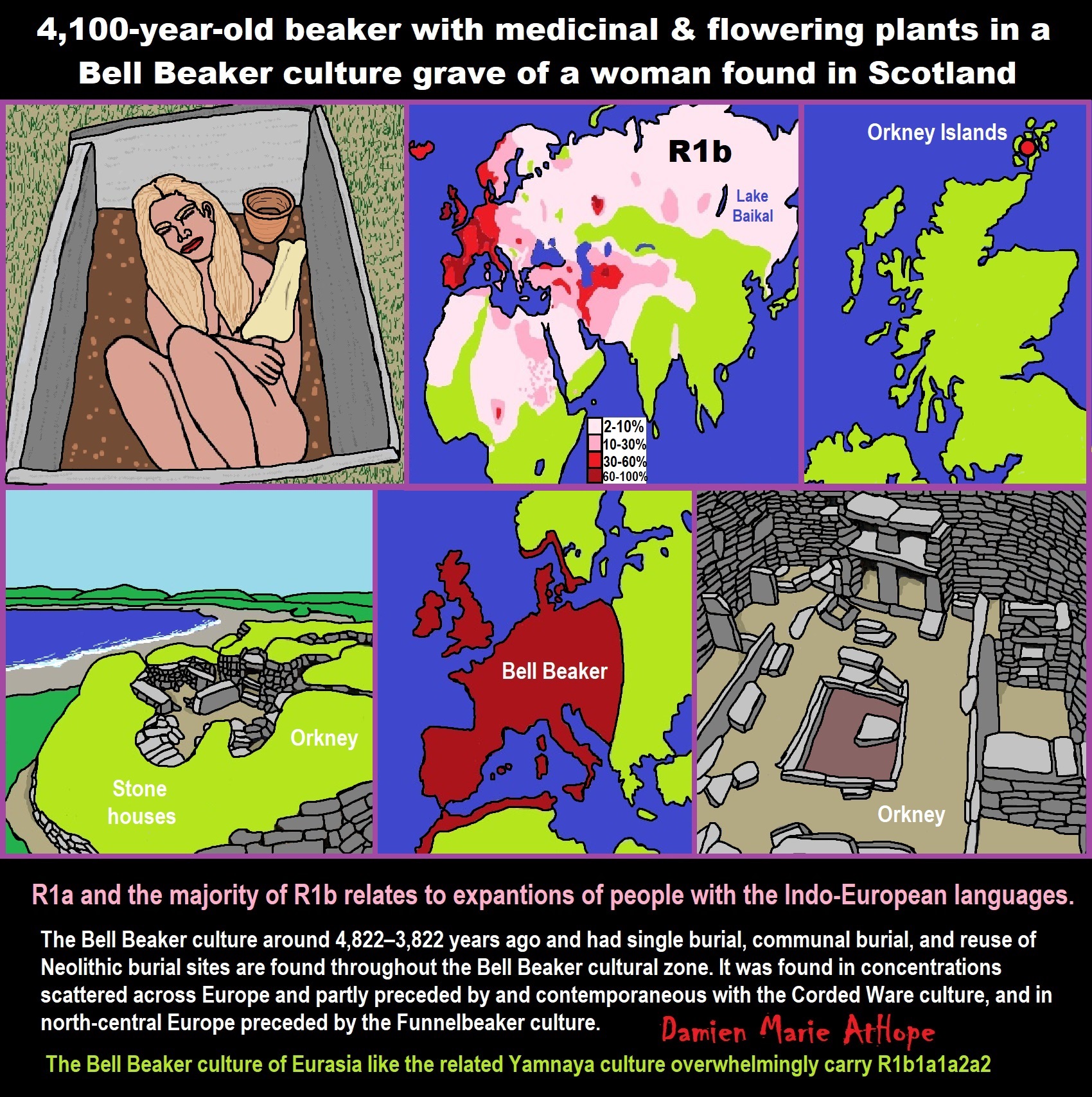

“They are also closely connected to Final Neolithic cultures, which later spread throughout Europe and Central Asia, especially the Corded Ware people and the Bell Beaker culture, as well as the peoples of the Sintashta, Andronovo, and Srubnaya cultures. Back migration from Corded Ware also contributed to Sintashta and Andronovo. In these groups, several aspects of the Yamnaya culture are present. Genetic studies have also indicated that these populations derived large parts of their ancestry from the steppes.” ref

“The Yamnaya culture is identified with the late Proto-Indo-Europeans, and the Pontic-Caspian steppe is the strongest candidate for the Urheimat (original homeland) of the Proto-Indo-European language.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Mal’ta–Buret’ culture

“The Mal’ta–Buret’ culture is an archaeological culture of c. 24,000 to 15,000 BP / 22’050 to 13’050 BC in the Upper Paleolithic on the upper Angara River in the area west of Lake Baikal in the Irkutsk Oblast, Siberia, Russian Federation. The type sites are named for the villages of Mal’ta (Мальта́), Usolsky District and Buret’ (Буре́ть), Bokhansky District (both in Irkutsk Oblast).” ref

“A boy whose remains were found near Mal’ta is usually known by the abbreviation MA-1 (or MA1). Discovered in the 1920s, the remains have been dated to 24,000 years ago. According to research published in 2013, MA-1 belonged to a population related to the genetic ancestors of Siberians, American Indians, and Bronze Age Yamnaya and Botai people of the Eurasian steppe. In particular, modern-day Native Americans, Kets, Mansi, and Selkup have been found to harbor a significant amount of ancestry related to MA-1.” ref

Afontova Gora culture

“Afontova Gora is a Late Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic Siberian complex of archaeological sites located on the left bank of the Yenisei River near the city of Krasnoyarsk, Russia. Afontova Gora has cultural and genetic links to the people from Mal’ta-Buret’. The complex was first excavated in 1884 by I. T. Savenkov. Afontova Gora is a complex, consisting of multiple stratigraphic layers, of five or more campsites. The campsites shows evidence of mammoth hunting and were likely the result of an eastward expansion of mammoth hunters.” ref

“Afontova Gora I is situated on the western bank of the Enisei River and has yielded the remains from horse, mammoth, reindeer, steppe bison, and large canids. A canid tibia has been dated 16,900 years old and the skull has been taxonomically described as being that of a dog, but it is now lost. Its description falls outside of the range of Pleistocene or modern northern wolves.” ref

Trialetian Mesolithic culture

“Trialetian is the name for an Upper Paleolithic–Epipaleolithic stone tool industry from the South Caucasus. It is tentatively dated to the period between 16,000 / 13,000- 8,000 years ago. The Caucasian–Anatolian area of Trialetian culture was adjacent to the Iraqi–Iranian Zarzian culture to the east and south as well as the Levantine Natufian to the southwest. Alan H. Simmons describes the culture as “very poorly documented.” ref

‘In contrast, recent excavations in the Valley of Qvirila river, to the north of the Trialetian region, display a Mesolithic culture.[citation needed] The subsistence of these groups were based on hunting Capra caucasica, wild boar, and brown bear. Differences have been found between the Trialetian and the Caspian Mesolithic of the southeastern part of the Caspian Sea (represented by sites like Komishan, Hotu, Kamarband, and Ali Tepe), even though the Caspian Mesolithic had previously been attributed to Trialetian by Kozłowski (1994, 1996 and 1999), Kozłowski and Aurenche 2005 and Peregrine and Ember 2002.” ref

“These differences have been established through a detailed study of the site of Komishan and are driven by the underlying differences at the level of cultural ecology. While Trialetian industry developed in steppe riparian and mountain ecozones, as for example in the Khrami river and the mountainous site of Chokh respectively, the Caspian Mesolithic took place in a transitional ecotone between the sea (Caspian Sea), plain, and mountains (Alborz mountain range).” ref

“The Caspian Mesolithic hunter-gatherers were adapted to the exploitation of marine resources and had access to high quality raw material, whereas in the Trialetian sites as Chokh and Trialeti there is imported raw material from distances of 100 km. Kmlo-2 is a rock shelter situated on the west slope of the Kasakh River valley, on the Aragats massif, in Armenia. This site seems to present three different phases of occupation (11-10k cal BCE, 9-8k cal BCE and 6-5k cal BCE).

“The lithic industry of the three phases show similarities such as the predominance of microliths, small cores and obsidian as raw material. The backed an scalene bladelets are the dominant type of microlith; these tools show similarities with those of the Late Upper Paleolithic of Kalavan-1 and the Mesolithic layer B of the Kotias Klde. Cultural affinities of the Kmlo-2 lithic industry with the Epipaleolithic and Aceramic Neolithic sites in Taurus-Zagros mountains have also been noted.” ref

“Little is known about the end of the Trialetian. 6k BC has been proposed as the time on which the decline phase took place. From this date are the first evidence of the Jeitunian, an industry that has probably evolved from the Trialetian. Also from this date are the first pieces of evidence of Neolithic materials in the Belt cave.” ref

“In the southwest corner of the Trialetian region it has been proposed that this culture evolved towards a local version of the PPNB around 7k BC, in sites as Cafer Höyük. Kozłowski suggests that the Trialetian does not seem to have a continuation in the Neolithic of Georgia (as for example in Paluri and Kobuleti). Although in the 5k BCE certain microliths similar to those of the Trialetian reappear in Shulaveris Gora (see Shulaveri-Shomu) and Irmis Gora.” ref

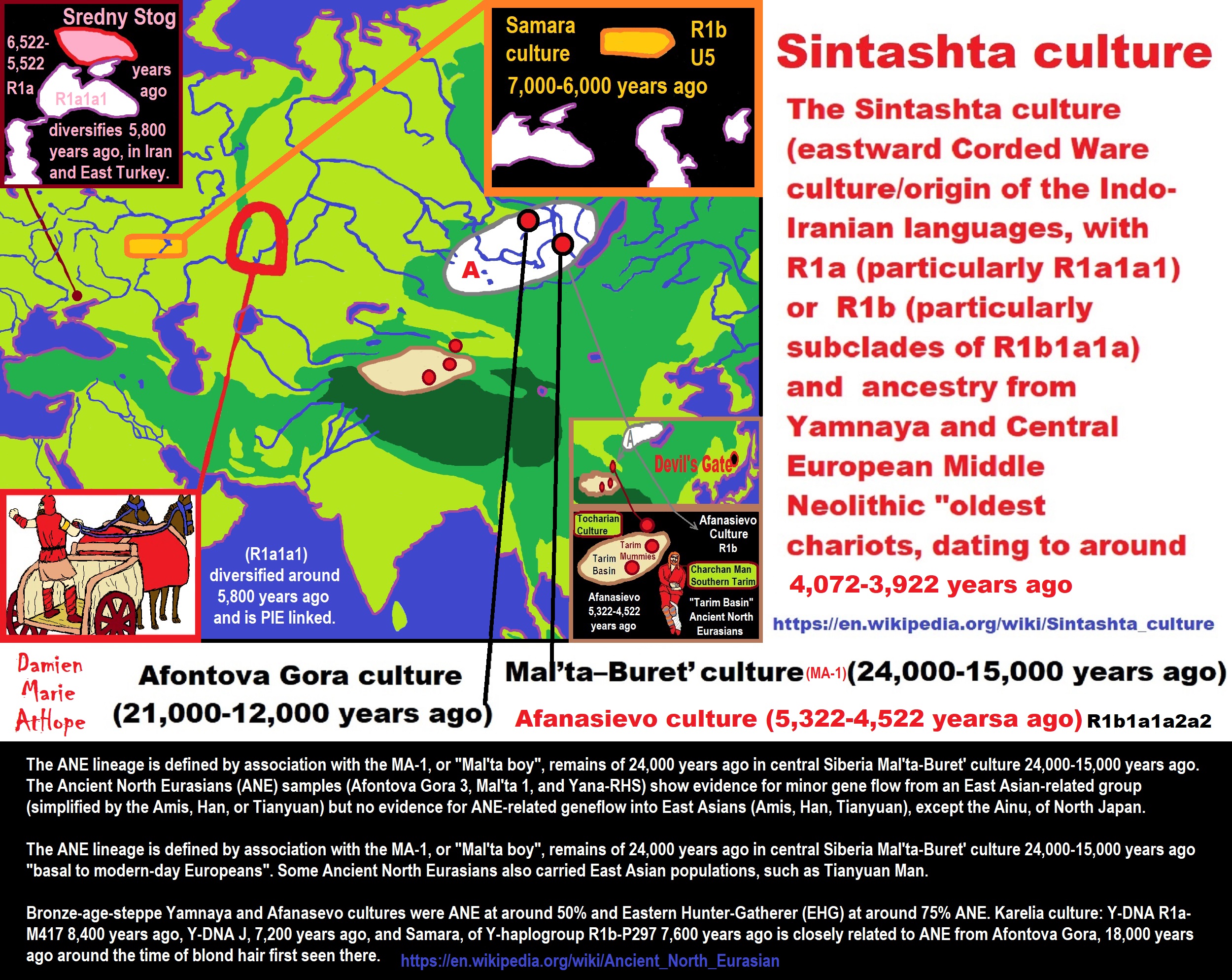

Sintashta Culture

“The Sintashta culture (eastward Corded Ware culture/origin of the Indo-Iranian languages, with R1a (particularly R1a1a1) or R1b (particularly subclades of R1b1a1a) and ancestry from Yamnaya and Central European Middle Neolithic “oldest chariots, dating to around 2050–1900 BCE.” ref

“The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000 BCE. The critical invention that allowed the construction of light, horse-drawn chariots was the spoked wheel.” ref

Horse Worship/Sacrifice: mythical union of Ruling Elite/Kingship and the Horse

Haplogroup R possible time of origin about 27,000 years in Central Asia, South Asia, or Siberia:

- Mal’ta–Buret’ culture (24,000-15,000 years ago)

- Afontova Gora culture (21,000-12,000 years ago)

- Trialetian culture (16,000–8000 years ago)

- Samara culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Khvalynsk culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Afanasievo culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Yamna/Yamnaya Culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Andronovo culture (4,000–2,900 years ago) ref

Trialetian sites

Caucasus and Transcaucasia:

- Edzani (Georgia)

- Chokh (Azerbaijan), layers E-C200

- Kotias Klde, layer B” ref

Eastern Anatolia:

- Hallan Çemi (from ca. 8.6-8.5k BC to 7.6-7.5k BCE)

- Nevali Çori shows some Trialetian admixture in a PPNB context” ref

Trialetian influences can also be found in:

- Cafer Höyük

- Boy Tepe” ref

Southeast of the Caspian Sea:

- Hotu (Iran)

- Ali Tepe (Iran) (from cal. 10,500 to 8,870 BCE)

- Belt Cave (Iran), layers 28-11 (the last remains date from ca. 6,000 BCE)

- Dam-Dam-Cheshme II (Turkmenistan), layers7,000-3,000 BCE)” ref

“The belonging of these Caspian Mesolithic sites to the Trialetian has been questioned. Little is known about the end of the Trialetian. 6k BC has been proposed as the time on which the decline phase took place. From this date are the first evidence of the Jeitunian, an industry that has probably evolved from the Trialetian. Also from this date are the first pieces of evidence of Neolithic materials in the Belt cave.” ref

“In the southwest corner of the Trialetian region it has been proposed that this culture evolved towards a local version of the PPNB around 7,000 BCE, in sites as Cafer Höyük. Kozłowski suggests that the Trialetian does not seem to have continuation in the Neolithic of Georgia (as for example in Paluri and Kobuleti). Although in the 5,000 BCE certain microliths similar to those of the Trialetian reappear in Shulaveris Gora (see Shulaveri-Shomu) and Irmis Gora.” ref

“The genome of a Mesolithic hunter-gatherer individual found at the layer A2 of the Kotias Klde rock shelter in Georgia (labeled KK1), dating from 9,700 years ago, has been analyzed. This individual forms a genetic cluster with another hunter-gatherer from the Satsurblia Cave, the so-called Caucasian Hunter-Gatherer (CHG) cluster. KK1 belongs to the Y-chromosome haplogruoup J2a (an independent analysis has assigned him J2a1b-Y12379*).” ref

“Although the belonging of the Caspian Mesolithic to the Trialetian has been questioned, it is worth noting that genetic similarities have been found between an Mesolithic hunther-gatherer from the Hotu cave (labeled Iran_HotuIIIb) dating from 9,100-8,600 BCE and the CHG from Kotias Klde. The Iran_HotuIIIb individual belongs to the Y-chromosome haplogroup J (xJ2a1b3, J2b2a1a1) (an independent analysis yields J2a-CTS1085(xCTS11251,PF5073) -probably J2a2-). Then, both KK1 and Iran_HotuIIIb individuals share a paternal ancestor that lived approximately 18.7k years ago (according to the estimates of full). At the autosomal level, it falls in the cluster of the CHG’s and the Iranian Neolithic Farmers.” ref

“Göbekli Tepe (“Potbelly Hill”) is a Neolithic archaeological site near the city of Şanlıurfa in Southeastern Anatolia, Turkey. Dated to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, between c. 9500 and 8000 BCE, the site comprises a number of large circular structures supported by massive stone pillars – the world’s oldest known megaliths. Many of these pillars are richly decorated with abstract anthropomorphic details, clothing, and reliefs of wild animals, providing archaeologists rare insights into prehistoric religion and the particular iconography of the period..” ref

“R1b is the most common haplogroup in Western Europe, reaching over 80% of the population in Ireland, the Scottish Highlands, western Wales, the Atlantic fringe of France, the Basque country, and Catalonia. It is also common in Anatolia and around the Caucasus, in parts of Russia, and in Central and South Asia. Besides the Atlantic and North Sea coast of Europe, hotspots include the Po valley in north-central Italy (over 70%), Armenia (35%), the Bashkirs of the Urals region of Russia (50%), Turkmenistan (over 35%), the Hazara people of Afghanistan (35%), the Uyghurs of North-West China (20%) and the Newars of Nepal (11%). R1b-V88, a subclade specific to sub-Saharan Africa, is found in 60 to 95% of men in northern Cameroon.” ref

R1b Origins & History

R1b and Paleolithic mammoth hunters

“Haplogroup R* originated in North Asia just before the Last Glacial Maximum (26,500-19,000 years ago). This haplogroup has been identified in the remains of a 24,000 year-old boy from the Altai region, in south-central Siberia (Raghavan et al. 2013). This individual belonged to a tribe of mammoth hunters that may have roamed across Siberia and parts of Europe during the Paleolithic. Autosomally this Paleolithic population appears to have contributed mostly to the ancestry of modern Europeans and South Asians, the two regions where haplogroup R also happens to be the most common nowadays (R1b in Western Europe, R1a in Eastern Europe, Central and South Asia, and R2 in South Asia).” ref

“The oldest forms of R1b (M343, P25, L389) are found dispersed at very low frequencies from Western Europe to India, a vast region where could have roamed the nomadic R1b hunter-gatherers during the Ice Age. The three main branches of R1b1 (R1b1a, R1b1b, R1b1c) all seem to have stemmed from the Middle East. The southern branch, R1b1c (V88), is found mostly in the Levant and Africa. The northern branch, R1b1a (P297), seems to have originated around the Caucasus, eastern Anatolia or northern Mesopotamia, then to have crossed over the Caucasus, from where they would have invaded Europe and Central Asia. R1b1b (M335) has only been found in Anatolia.” ref

R1b and Neolithic cattle herders

“It has been hypothesised that R1b people (perhaps alongside neighboring J2 tribes) were the first to domesticate cattle in northern Mesopotamia some 10,500 years ago. R1b tribes descended from mammoth hunters, and when mammoths went extinct, they started hunting other large game such as bisons and aurochs. With the increase of the human population in the Fertile Crescent from the beginning of the Neolithic (starting 12,000 years ago), selective hunting and culling of herds started replacing the indiscriminate killing of wild animals. The increased involvement of humans in the life of aurochs, wild boars, and goats led to their progressive taming. Cattle herders probably maintained a nomadic or semi-nomadic existence, while other people in the Fertile Crescent (presumably represented by haplogroups E1b1b, G, and T) settled down to cultivate the land or keep smaller domesticates.” ref

“The analysis of bovine DNA has revealed that all the taurine cattle (Bos taurus) alive today descend from a population of only 80 aurochs. The earliest evidence of cattle domestication dates from circa 8,500 BCE in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic cultures in the Taurus Mountains. The two oldest archaeological sites showing signs of cattle domestication are the villages of Çayönü Tepesi in southeastern Turkey and Dja’de el-Mughara in northern Iraq, two sites only 250 km away from each others. This is presumably the area from which R1b lineages started expanding – or in other words the “original homeland” of R1b.” ref

“The early R1b cattle herders would have split in at least three groups. One branch (M335) remained in Anatolia, but judging from its extreme rarity today wasn’t very successful, perhaps due to the heavy competition with other Neolithic populations in Anatolia, or to the scarcity of pastures in this mountainous environment. A second branch migrated south to the Levant, where it became the V88 branch. Some of them searched for new lands south in Africa, first in Egypt, then colonizing most of northern Africa, from the Mediterranean coast to the Sahel.” ref

“The third branch (P297), crossed the Caucasus into the vast Pontic-Caspian Steppe, which provided ideal grazing grounds for cattle. They split into two factions: R1b1a1 (M73), which went east along the Caspian Sea to Central Asia, and R1b1a2 (M269), which at first remained in the North Caucasus and the Pontic Steppe between the Dnieper and the Volga. It is not yet clear whether M73 actually migrated across the Caucasus and reached Central Asia via Kazakhstan, or if it went south through Iran and Turkmenistan. In any case, M73 would be a pre-Indo-European branch of R1b, just like V88 and M335.” ref

“R1b-M269 (the most common form in Europe) is closely associated with the diffusion of Indo-European languages, as attested by its presence in all regions of the world where Indo-European languages were spoken in ancient times, from the Atlantic coast of Europe to the Indian subcontinent, which comprised almost all Europe (except Finland, Sardinia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina), Anatolia, Armenia, European Russia, southern Siberia, many pockets around Central Asia (notably in Xinjiang, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan), without forgetting Iran, Pakistan, northern India, and Nepal. The history of R1b and R1a are intricately connected to each others.” ref

The Levantine & African branch of R1b (V88)

“Like its northern counterpart (R1b-M269), R1b-V88 is associated with the domestication of cattle in northern Mesopotamia. Both branches of R1b probably split soon after cattle were domesticated, approximately 10,500 years ago (8,500 BCE). R1b-V88 migrated south towards the Levant and Egypt. The migration of R1b people can be followed archeologically through the presence of domesticated cattle, which appear in central Syria around 8,000-7,500 BCE (late Mureybet period), then in the Southern Levant and Egypt around 7,000-6,500 BCE (e.g. at Nabta Playa and Bir Kiseiba). Cattle herders subsequently spread across most of northern and eastern Africa. The Sahara desert would have been more humid during the Neolithic Subpluvial period (c. 7250-3250 BCE), and would have been a vast savannah full of grass, an ideal environment for cattle herding.” ref

“Evidence of cow herding during the Neolithic has shown up at Uan Muhuggiag in central Libya around 5500 BCE, at the Capeletti Cave in northern Algeria around 4500 BCE. But the most compelling evidence that R1b people related to modern Europeans once roamed the Sahara is to be found at Tassili n’Ajjer in southern Algeria, a site famous pyroglyphs (rock art) dating from the Neolithic era. Some painting dating from around 3000 BCE depict fair-skinned and blond or auburn haired women riding on cows. The oldest known R1b-V88 sample in Europe is a 6,200 year-old farmer/herder from Catalonia tested by Haak et al. (2015). Autosomally this individual was a typical Near Eastern farmer, possessing just a little bit of Mesolithic West European admixture.” ref

“After reaching the Maghreb, R1b-V88 cattle herders could have crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to Iberia, probably accompanied by G2 farmers, J1 and T1a goat herders. These North African Neolithic farmers/herders could have been the ones who established the Almagra Pottery culture in Andalusia in the 6th millennium BCE.” ref

“Nowadays small percentages (1 to 4%) of R1b-V88 are found in the Levant, among the Lebanese, the Druze, and the Jews, and almost in every country in Africa north of the equator. Higher frequency in Egypt (5%), among Berbers from the Egypt-Libya border (23%), among the Sudanese Copts (15%), the Hausa people of Sudan (40%), the the Fulani people of the Sahel (54% in Niger and Cameroon), and Chadic tribes of northern Nigeria and northern Cameroon (especially among the Kirdi), where it is observed at a frequency ranging from 30% to 95% of men.” ref

“According to Cruciani et al. (2010) R1b-V88 would have crossed the Sahara between 9,200 and 5,600 years ago, and is most probably associated with the diffusion of Chadic languages, a branch of the Afroasiatic languages. V88 would have migrated from Egypt to Sudan, then expanded along the Sahel until northern Cameroon and Nigeria. However, R1b-V88 is not only present among Chadic speakers, but also among Senegambian speakers (Fula-Hausa) and Semitic speakers (Berbers, Arabs).” ref

“R1b-V88 is found among the native populations of Rwanda, South Africa, Namibia, Angola, Congo, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Ivory Coast, Guinea-Bissau. The wide distribution of V88 in all parts of Africa, its incidence among herding tribes, and the coalescence age of the haplogroup all support a Neolithic dispersal. In any case, a later migration out of Egypt would be improbable since it would have brought haplogroups that came to Egypt during the Bronze Age, such as J1, J2, R1a, or R1b-L23. The maternal lineages associated with the spread of R1b-V88 in Africa are mtDNA haplogroups J1b, U5, and V, and perhaps also U3 and some H subclades (=> see Retracing the mtDNA haplogroups of the original R1b people).” ref

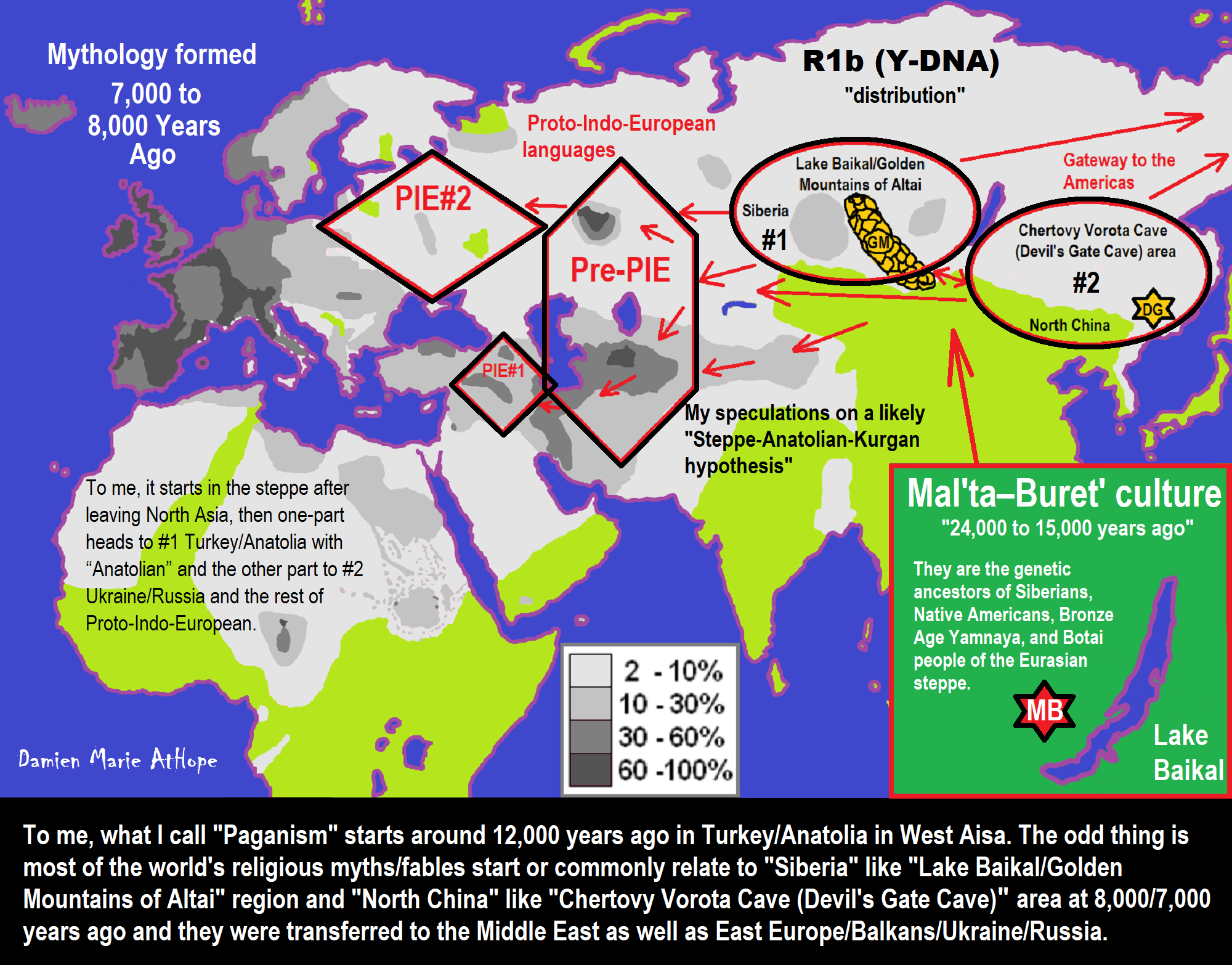

The North Caucasus and the Pontic-Caspian steppe : the Indo-European link

“Modern linguists have placed the Proto-Indo-European homeland in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe, a distinct geographic and archeological region extending from the Danube estuary to the Ural mountains to the east and North Caucasus to the south. The Neolithic, Eneolithic, and early Bronze Age cultures in Pontic-Caspian steppe has been called the Kurgan culture (4200-2200 BCE) by Marija Gimbutas, due to the lasting practice of burying the deads under mounds (“kurgan”) among the succession of cultures in that region. It is now known that kurgan-type burials only date from the 4th millenium BCE and almost certainly originated south of the Caucasus. The genetic diversity of R1b being greater around eastern Anatolia, it is hard to deny that R1b evolved there before entering the steppe world.” ref

“Horses were first domesticated around 4600 BCE in the Caspian Steppe, perhaps somewhere around the Don or the lower Volga, and soon became a defining element of steppe culture. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that R1b was already present in the eastern steppes at the time, so the domestication of the horse should be attributed to the indigenous R1a people, or tribes belonging to the older R1b-P297 branch, which settled in eastern Europe during the Late Paleolithic or Mesolithic period. Samples from Mesolithic Samara (Haak 2015) and Latvia (Jones 2017) all belonged to R1b-P297. Autosomally these Mesolithic R1a and R1b individuals were nearly pure Mesolithic East European, sometimes with a bit of Siberian admixture, but lacked the additional Caucasian admixture found in the Chalcolithic Afanasevo, Yamna and Corded Ware samples.” ref

“It is not yet entirely clear when R1b-M269 crossed over from the South Caucasus to the Pontic-Caspian steppe. This might have happened with the appearance of the Dnieper-Donets culture (c. 5100-4300 BCE). This was the first truly Neolithic society in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe. Domesticated animals (cattle, sheep, and goats) were herded throughout the steppes and funeral rituals were elaborate. Sheep wool would play an important role in Indo-European society, notably in the Celtic and Germanic (R1b branches of the Indo-Europeans) clothing traditions up to this day.” ref

“However, many elements indicate a continuity in the Dnieper-Donets culture with the previous Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, and at the same time an influence from the Balkans and Carpathians, with regular imports of pottery and copper objects. It is, therefore, more likely that Dnieper-Donets marked the transition of indigenous R1a and/or I2a1b people to early agriculture, perhaps with an influx of Near Eastern farmers from ‘Old Europe’. Over 30 DNA samples from Neolithic Ukraine (5500-4800 BCE) were tested by Mathieson et al. (2017).” ref

“They belonged to Y-haplogroups I, I2a2, R1a, R1b1a (L754), and one R1b1a2 (L388). None of them belonged to R1b-M269 or R1b-L23 clades, which dominated during the Yamna period. Mitochondrial lineages were also exclusively of Mesolithic European origin (U4a, U4b, U4d, U5a1, U5a2, U5b2, as well as one J2b1 and one U2e1). None of those maternal lineages include typical Indo-European haplogroups, like H2a1, H6, H8, H15, I1a1, J1b1a, W3, W4 or W5 that would later show up in the Yamna, Corded Ware, and Unetice cultures. Indeed, autosomally genomes from Neolithic Ukraine were purely Mesolithic European (about 90% EHG and 10% WHG) and completely lacked the Caucasian (CHG) admxiture later found in Yamna and subsequent Indo-European cultures during the Bronze Age.” ref

“The first clearly Proto-Indo-European cultures were the Khvalynsk (5200-4500 BCE) and Sredny Stog (4600-3900 BCE) cultures in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe. This is when small kurgan burials begin to appear, with the distinctive posturing of the dead on the back with knees raised and oriented toward the northeast, which would be found in later steppe cultures as well. There is evidence of population blending from the variety of skull shapes.” ref

“Towards the end of the 5th millennium, an elite starts to develop with cattle, horses, and copper used as status symbols. It is at the turn of the Khvalynsk and Sredny Stog periods that R1b-M269’s main subclade, L23, is thought to have appeared, around 4,500 BCE. 99% of Indo-European R1b descends from this L23 clade. The other branch descended from M269 is PF7562, which is found mostly in the Balkans, Turkey, and Armenia today, and may represent an early Steppe migration to the Balkans dating from the Sredny Stog period.” ref

“Another migration across the Caucasus happened shortly before 3700 BCE, when the Maykop culture, the world’s first Bronze Age society, suddenly materialized in the north-west Caucasus, apparently out of nowhere. The origins of Maykop are still uncertain, but archeologists have linked it to contemporary Chalcolithic cultures in Assyria and western Iran. Archeology also shows a clear diffusion of bronze working and kurgan-type burials from the Maykop culture to the Pontic Steppe, where the Yamna culture developed soon afterwards (from 3500 BCE). Kurgan (a.k.a. tumulus) burials would become a dominant feature of ancient Indo-European societies and were widely used by the Celts, Romans, Germanic tribes, and Scythians, among others.” ref

“The Yamna period (3500-2500 BCE) is the most important one in the creation of Indo-European culture and society. Middle Eastern R1b-M269 people had been living and blending to some extent with the local R1a foragers and herders for over a millennium, perhaps even two or three. The close cultural contact and interactions between R1a and R1b people all over the Pontic-Caspian Steppe resulted in the creation of a common vernacular, a new lingua franca, which linguists have called Proto-Indo-European (PIE). It is pointless to try to assign another region of origin to the PIE language. Linguistic similarities exist between PIE and Caucasian and Hurrian languages in the Middle East on the one hand, and Uralic languages in the Volga-Ural region on the other hand, which makes the Pontic Steppe the perfect intermediary region.” ref

“During the Yamna period, cattle and sheep herders adopted wagons to transport their food and tents, which allowed them to move deeper into the steppe, giving rise to a new mobile lifestyle that would eventually lead to the great Indo-European migrations. This type of mass migration in which whole tribes moved with the help of wagons was still common in Gaul at the time of Julius Caesar, and among Germanic peoples in the late Antiquity.” ref

The Yamna horizon was not a single, unified culture. In the south, along the northern shores of the Black Sea coast until the the north-west Caucasus, was a region of open steppe, expanding eastward until the Caspian Sea, Siberia, and Mongolia (the Eurasian Steppe). The western section, between the Don and Dniester Rivers (and later the Danube), was the one most densely settled by R1b people, with only a minority of R1a people (5-10%). The eastern section, in the Volga basin until the Ural mountains, was inhabited by R1a people with a substantial minority of R1b people (whose descendants can be found among the Bashkirs, Turkmans, Uyghurs, and Hazaras, among others).” ref

“The northern part of the Yamna horizon was forest-steppe occupied by R1a people, also joined by a small minority of R1b (judging from Corded Ware samples and from modern Russians and Belarussians, whose frequency of R1b is from seven to nine times lower than R1a). The western branch would migrate to the Balkans and Greece, then to Central and Western Europe, and back to their ancestral Anatolia in successive waves (Hittites, Phrygians, Armenians, etc.). The eastern branch would migrate to Central Asia, Xinjiang, Siberia, and South Asia (Iran, Pakistan, India). The northern branch would evolve into the Corded Ware culture and disperse around the Baltic, Poland, Germany, and Scandinavia.” ref

The Maykop culture, the R1b link to the Steppe?

“The Maykop culture (3700-2500 BCE) in the north-west Caucasus was culturally speaking a sort of southern extension of the Yamna horizon. Although not generally considered part of the Pontic-Caspian steppe culture due to its geography, the North Caucasus had close links with the steppes, as attested by numerous ceramics, gold, copper, and bronze weapons and jewelry in the contemporaneous cultures of Mikhaylovka, Sredny Stog, and Kemi Oba. The link between the northern Black Sea coast and the North Caucasus is older than the Maykop period. Its predecessor, the Svobodnoe culture (4400-3700 BCE), already had links to the Suvorovo-Novodanilovka and early Sredny Stog cultures. The even older Nalchik settlement (5000-4500 BCE) in the North Caucasus displayed a similar culture as Khvalynsk in the Caspian Steppe and Volga region. This may be the period when R1b started interracting and blending with the R1a population of the steppes.” ref

“The Yamna and Maykop people both used kurgan burials, placing their deads in a supine position with raised knees and oriented in a north-east/south-west axis. Graves were sprinkled with red ochre on the floor, and sacrificed domestic animal buried alongside humans. They also had in common horses, wagons, a heavily cattle-based economy with a minority of sheep kept for their wool, use of copper/bronze battle-axes (both hammer-axes and sleeved axes), and tanged daggers. In fact, the oldest wagons and bronze artifacts are found in the North Caucasus, and appear to have spread from there to the steppes.” ref

‘Maykop was an advanced Bronze Age culture, actually one of the very first to develop metalworking, and therefore metal weapons. The world’s oldest sword was found at a late Maykop grave in Klady kurgan 31. Its style is reminiscent of the long Celtic swords, though less elaborated. Horse bones and depictions of horses already appear in early Maykop graves, suggesting that the Maykop culture might have been founded by steppe people or by people who had close link with them. However, the presence of cultural elements radically different from the steppe culture in some sites could mean that Maykop had a hybrid population.” ref