Gemini (constellation)

“Gemini is one of the constellations of the zodiac and is located in the northern celestial hemisphere. It was one of the 48 constellations described by the 2nd century CE astronomer Ptolemy, and it remains one of the 88 modern constellations today. Its name is Latin for twins, and it is associated with the twins Castor and Pollux in Greek mythology. Its old astronomical symbol is ![]() (♊︎). Gemini lies between Taurus to the west and Cancer to the east, with Auriga and Lynx to the north, Monoceros and Canis Minor to the south, and Orion to the south-west.” ref

(♊︎). Gemini lies between Taurus to the west and Cancer to the east, with Auriga and Lynx to the north, Monoceros and Canis Minor to the south, and Orion to the south-west.” ref

I am adding many Native American Deities to show:

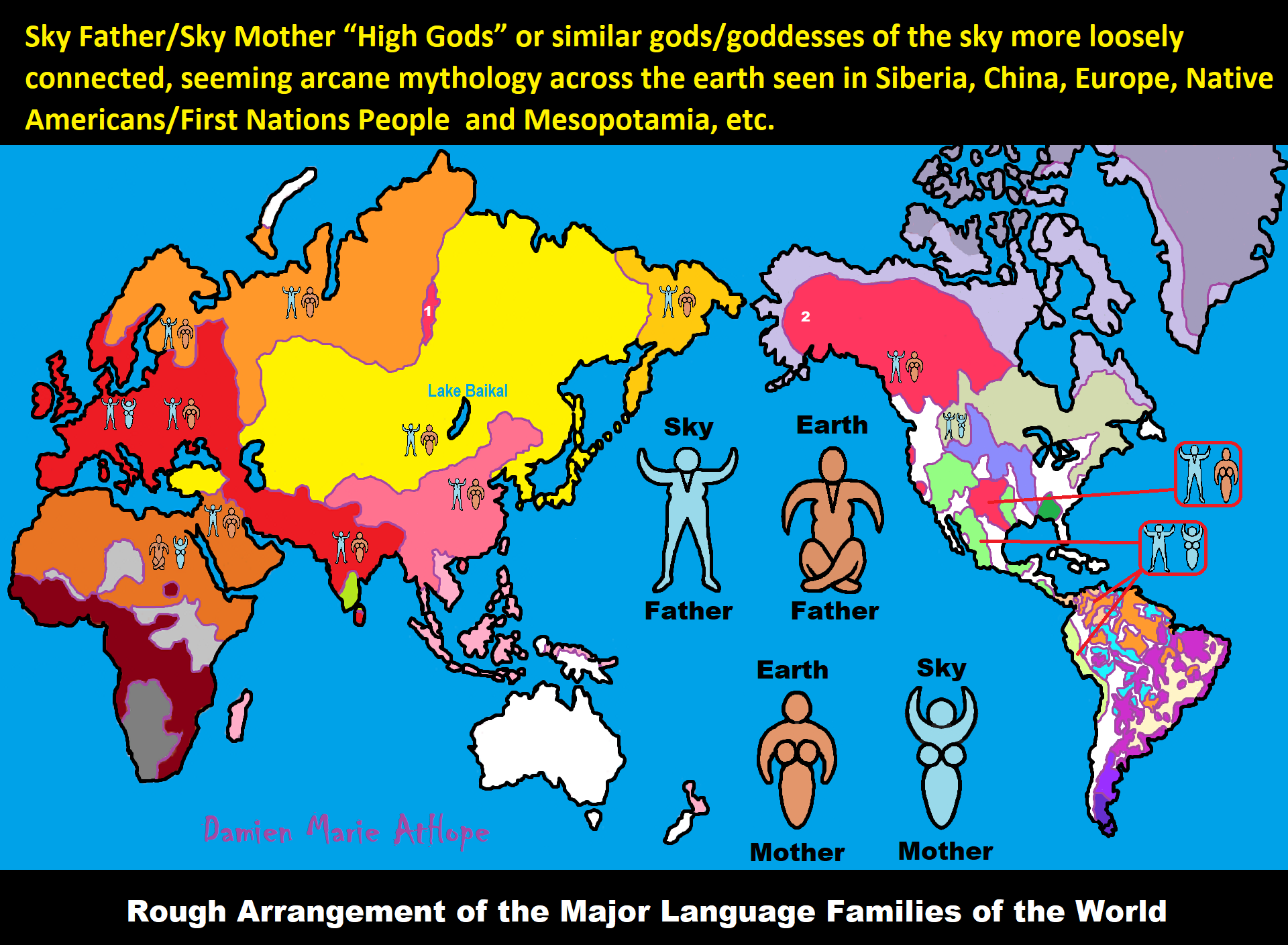

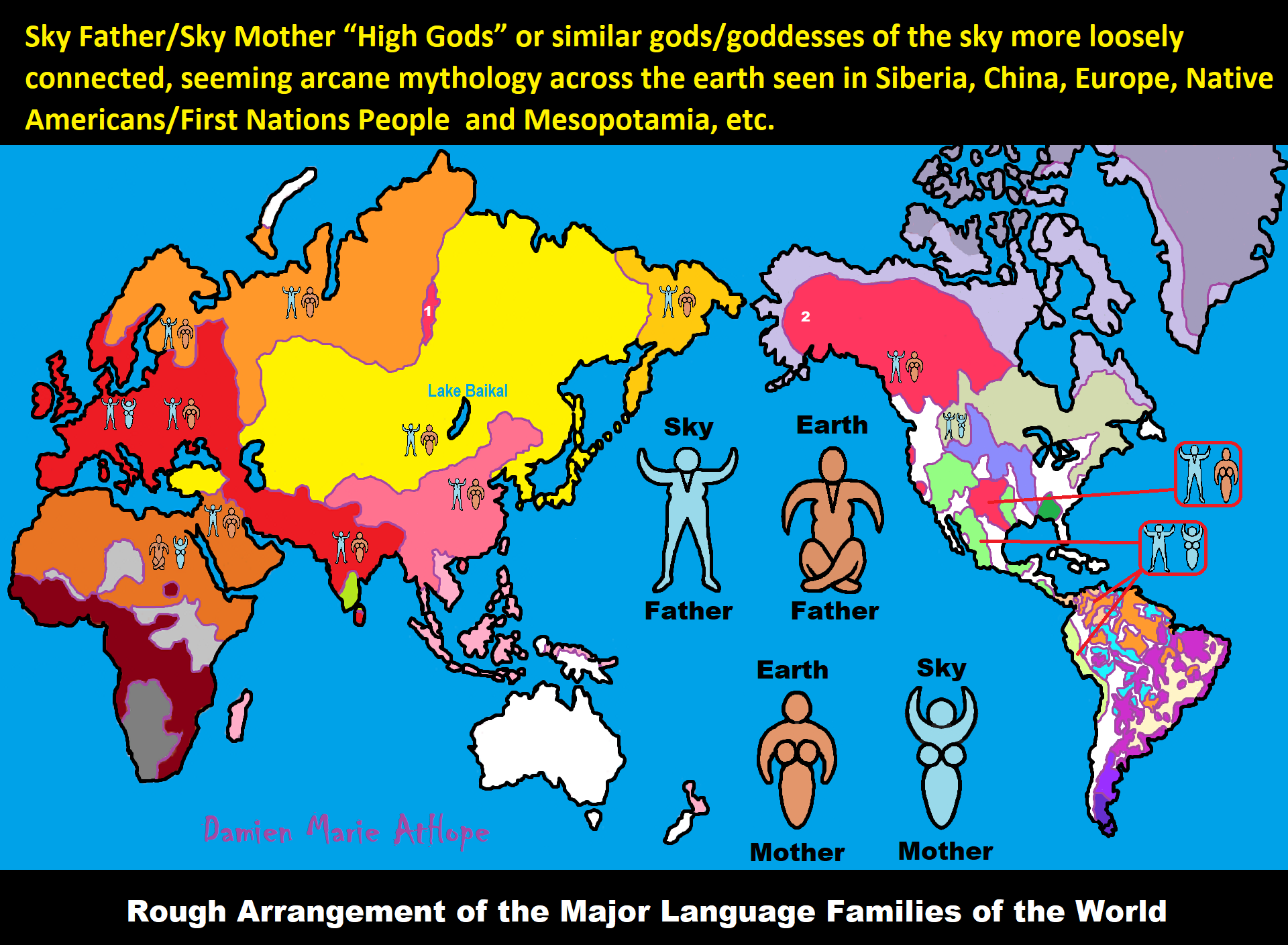

Sky Father (in Proto-Indo-European mythology): High god, often related to the sun

Twin/two Sons: (Devine Twins in Proto-Indo-European mythology)

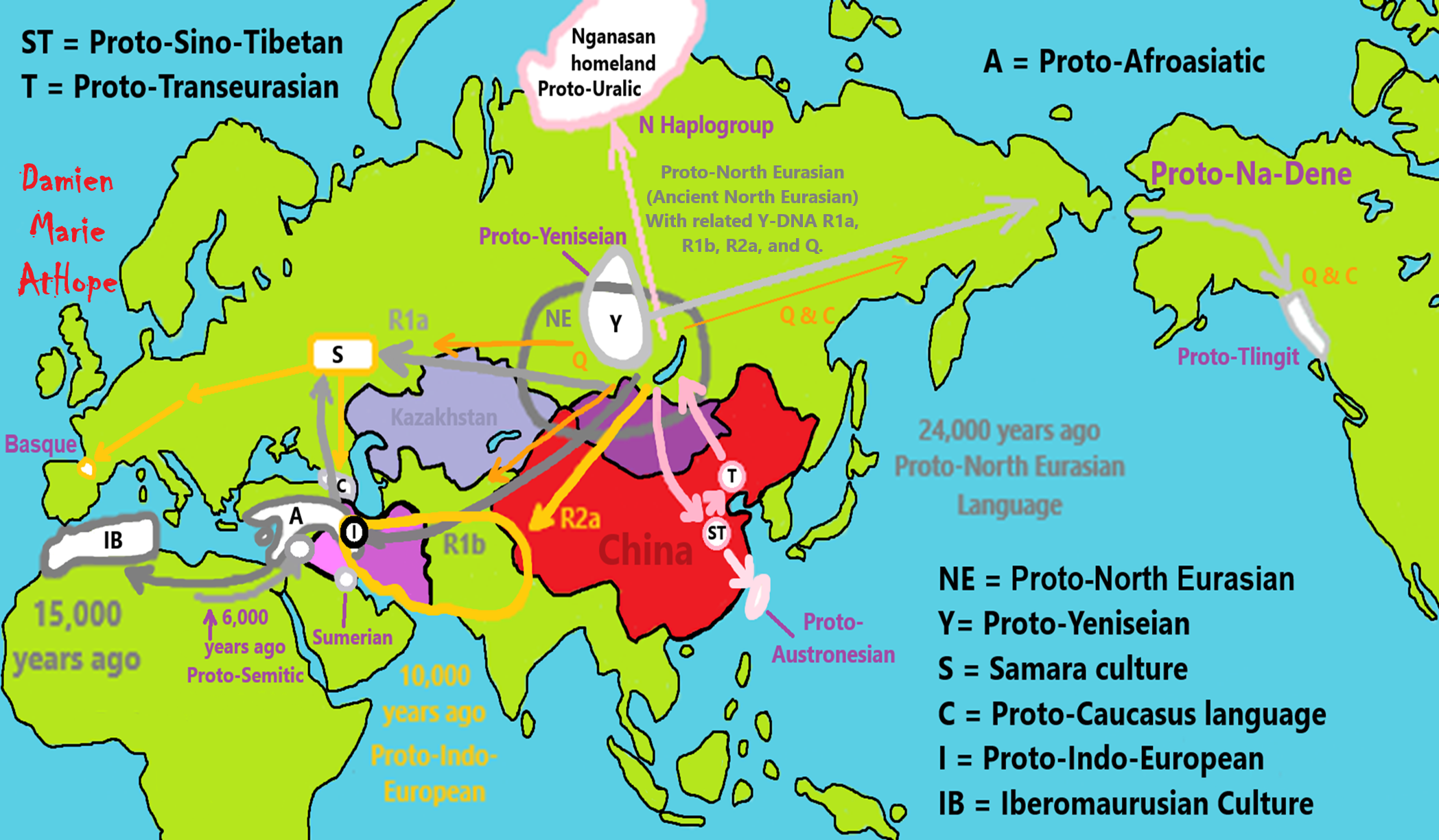

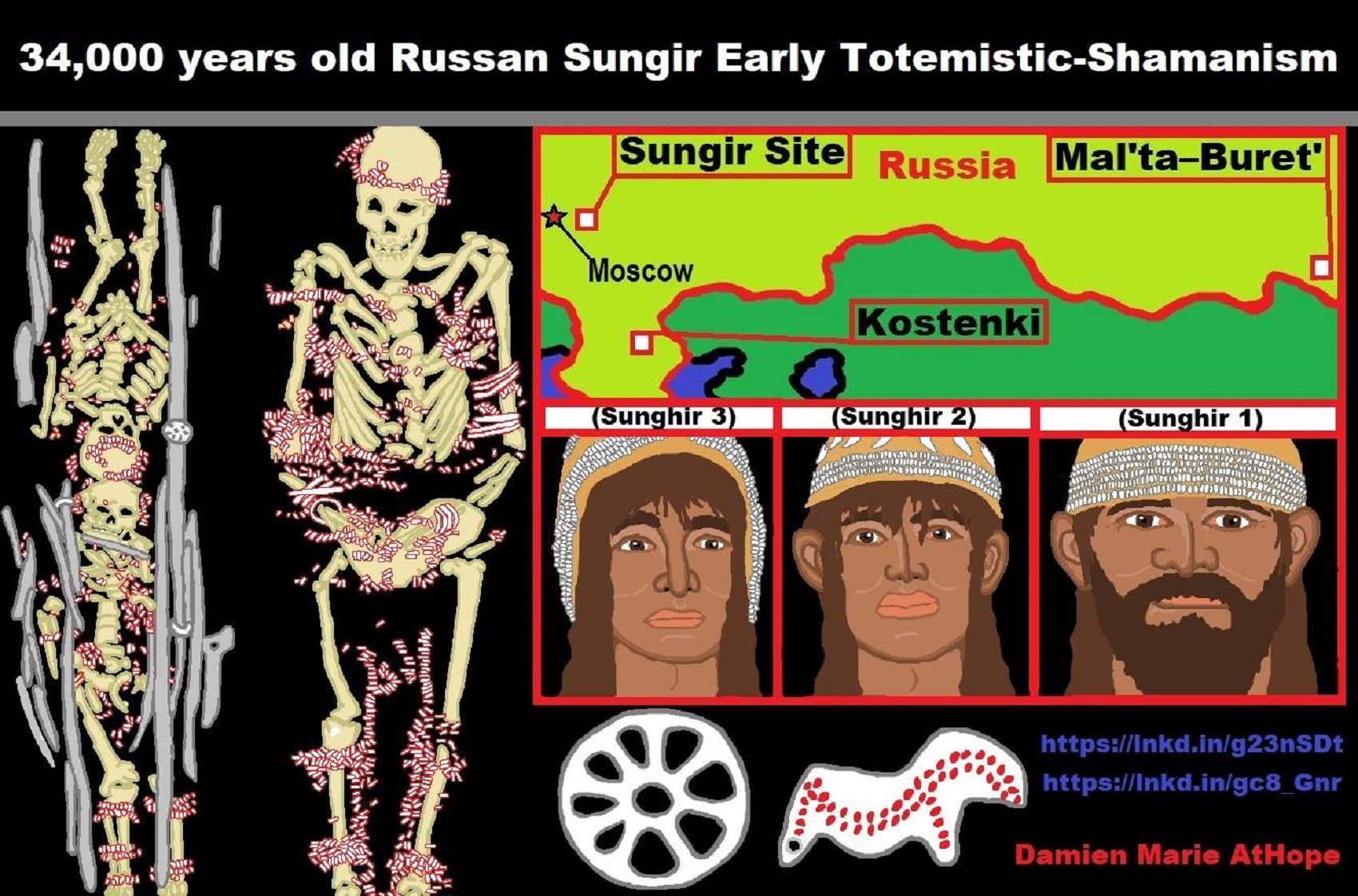

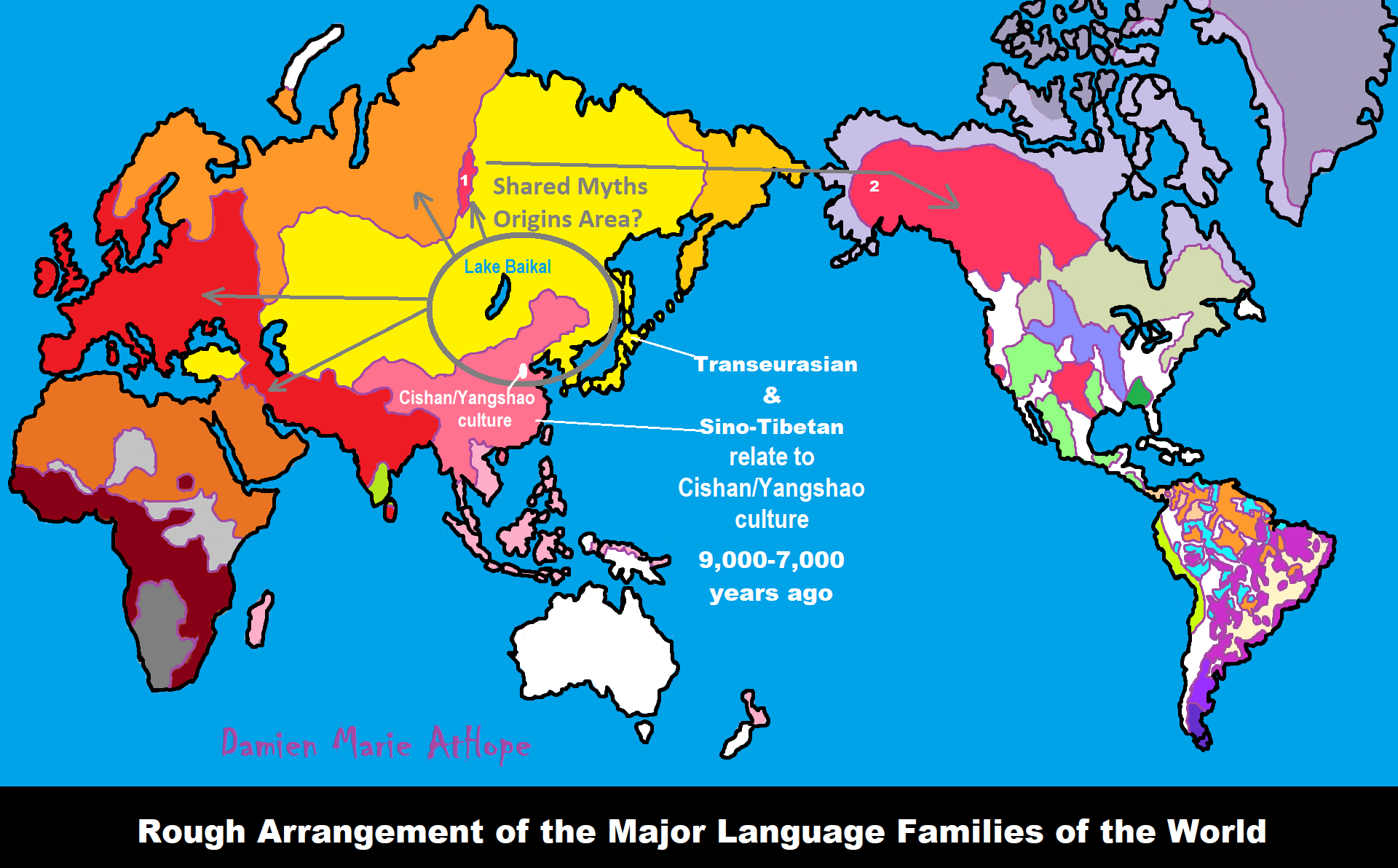

Sky Gods/Sky Father Gods: these, to me, are closely related myths going back to South Siberia/North China originally moved by migrations and trade.

“In comparative mythology, the sky father is a term for a recurring concept in polytheistic religion. The concept of “sky father” may also include Sun gods with similar characteristics, such as Ra. The concept is complementary to an “earth mother.” ref

Nitosi: Creator god, high god, sky spirit

Nitosi, or Yedariye, is the name of the great sky god of the Dene tribes.

Related figures in other tribes: Utakké (Carrier), Nesaru (Arikara), Gitchie Manitou (Chippewa) ref

Mukat: Creator deity, high god

“Cahuilla and other Sonoran tribes of southeast California and southwestern Arizona consider him dangerous; made the life of the ancients miserable, drove away their protector, Menily, goddess of the moon, and was eventually slain by his own creations after teaching them warfare. In the creation, Mukat and Temayuwat were born from the union of twin balls of lightning, which were the manifestations of Amnaa (Power) and Tukmiut (Night). Mukat and Temayuwat began a creative contest, in which Temayuwat was bested and fled with his ill-formed creation below the earth.” ref, ref

Divine Twins gods?

The Divine Twins are youthful horsemen, either gods or demigods, rescuers, and healers in Proto-Indo-European mythology. Often with mention of a female figure (their mother or their sister), two brothers are “Descendants” (sons or grandsons) of the Sky-God (Dyēus).” ref

“The Hero Twins (or God Boys) are recurring characters from the mythologies of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. The specifics of each myth vary from tribe to tribe, but each story has a pair of twins (usually with magical powers) who were born when their pregnant mother was killed by the tale’s antagonist. Twins were considered unnatural in many cultures of this region, with beliefs about them having supernatural abilities. Sometimes, the twins are separated at birth. Various versions have their mother’s killer leaving one where he could be easily be found by his family and the other deep in the wilderness so that one boy grew up civilized and the other wild. Eventually they become reunited and avenge the death of their mother. Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca are culture heroes and creator deities of the Aztecs and are said to be brothers. They are often seen in competition with each other, like when the two fought over who would become the sun.[1] They are also seen as allies however, as both are considered protectors of Earth. They are also depicted as having another brother, Xolotl. He is even shown as helping Quetzalcoatl returning the bones of the humans to the land of the living to bring them back to life.” ref

“The Twin Heroes share many similarities in the mythology of different tribes, but are different in their relationships with other mythological figures, their associations with stars or animal spirits, and the nature of the particular adventures they go on. In some traditions, the twins personified good and evil: one twin is good while the other is evil, but in others both are benevolent heroes. In some versions of this myth, the evil twin manipulates others into blaming his good brother for his misdeeds. The two brothers coexisted for a while, each making their own changes to the world. In the end, though, the Twin Gods fight each other, and the good brother prevails. In other traditions, the Twin Gods are not considered good or evil but instead represent day and night, summer and winter, and life and death. In some versions of that tradition, one is a trickster rather than a villain, and the brothers’ relationship is one of rivalry rather than enmity.” ref

Native American Magical twin

“The birth of twins is considered a notable event in many Native American cultures. In most cultures, twins are considered good luck, while in some, twins are considered spiritually powerful and were trained as medicine people. Twin gods or heroes are a common motif in the mythology of many North American tribes, and human twins were sometimes associated with these mythological figures. In some Northwest Coast tribes, such as the Kwakwaka’wakw, twins are believed to be blessed by the Salmon People and have special ceremonial roles in the Salmon Ceremony. In some Southwestern tribes, such as the Mojave, twins were considered supernatural visitors who were exempt from normal tribal taboos, and though that tradition is no longer commonly observed, twins are still seen as a special blessing in these tribes. Twins are not viewed positively in all tribes, however. In some South American cultures, twins are considered a bad omen or the result of black magic, and some parents have even abandoned their newborn twins due to this belief.” ref

Native American legends and traditional stories about twins.

Native American Twin Spirits

Amalivaca and Vochi (Cariban)

The God Boys (Caddo)

Hunahpu and Ixbalanque (Maya)

Keri and Kame (Bakairi)

The Little Thunders (Seminole)

Macunaima and Pia (Carib)

Monster Slayer and Child of Water (Navajo)

The Twin Gods, Good Spirit and Bad Spirit (Iroquois)

The Twin Heroes, Lodge Boy and Spring Boy (Plains tribes)

Native American Twin Stories

Lodge-Boy and Thrown-Away:

Crow legend about the two mythical twins.

The Twin Brothers The Brothers Who Became Lightning And Thunder:

Caddo legends about the twin heroes, Thunder and Lightning.

The Birth of Good and Evil:

Oneida myth about Sky Woman’s twin grandchildren.

The Creation:

Cayuga myth about Sky Woman and her twin sons Good Spirit and Bad Spirit.

The “two sons” of Abaangüí, god of the moon in the mythology of the Guarani Indians, climbed this chain until they reached the sky and remained there, turning into the sun and the moon.” ref

Kame (Kami): Creator god, Mythical twin

“Kame is one of the twin creator gods of the Bakairi tribe. Together with his brother Keri, Kame adapted the world for humans to live on. In other tribes: Mopo and Kujuli (Apalai)” ref

“Awonawilona. – Dual deity of the Zuñi Indians of New Mexico. He created a universe of nine layers. Earth, a large round island surrounded by oceans, is located on the central layer. The first people lived deep in the womb of Mother Earth ( Awitelin Tsta ). Then Father Sun ( Apoyan Tachi ) ordered his twin sons, the gods of war, to take them to earth because he was bored and had no one to pray to.” ref

Maya Hero Twins

“The Maya Hero Twins are the central figures of a narrative included within the colonial Kʼicheʼ document called Popol Vuh, and constituting the oldest Maya myth to have been preserved in its entirety. Called Hunahpu [hunaxˈpu] and Xbalanque [ʃɓalaŋˈke][2] in the Kʼicheʼ language, the Twins have also been identified in the art of the Classic Mayas (200–900 AD). The twins are often portrayed as complementary forces. The Twin motif recurs in many Native American mythologies; the Maya Twins, in particular, could be considered as mythical ancestors to the Maya ruling lineages.” ref

“Catequil (A.k.a. Apocatequil, Apu Catequil) was the tutelar god of day and good, thunder, and lightning in northern Peruvian highlands. Catequil and his twin brother Piguerao were born from hatched eggs. Catequil considered a regional variant of god Illapa.” ref

“Hahgwehdiyu is the Iroquois god of goodness and light, as well as a creator god. He and his twin brother Hahgwehdaetgah, the god of evil, were children of Atahensic the Sky Woman (or Tekawerahkwa the Earth Woman), whom Hahgwehdaetgah killed in childbirth.” ref

“Mount St. Helens and other Cascade volcanoes. The best known of these is the Bridge of the Gods story told by the Klickitat people of the Pacific Northwest.. The chief of all the gods “Great Spirit” and his two sons, WyEast (Mt. Hood) and Pahtoe, or Klickitat (Mt. Adams).” ref, ref

“Asdzą́ą́ Nádleehé is one of the creation spirits of the Navajo. She helped create the sky and the earth. Changing Woman, mother of twins Monster Slayer and Born for Water (fathered by the sun).” ref

“A zemi or cemi (Taíno: semi [sɛmi]) was a deity or ancestral spirit, and a sculptural object housing the spirit, among the Taíno people of the Caribbean. Cemi’no or Zemi’no is a plural word for the spirits. Supreme creator god and a fertility goddess. The creator god is Yúcahu Maórocoti and he governs the growth of the staple food, the cassava.” ref

“Twins? Yúcahu was the supreme deity of the Taíno people. The three names are thought to represent the Great Spirit’s epithets. He was the supreme deity or zemi of the Pre-Columbian Taíno people along with his mother Atabey who was his feminine counterpart.” ref

“The Taíno had a well developed creation myth, which was mostly passed down via oral tradition. According to this account, in the beginning there was only Atabey, who created the heavens. However, there was still a void, where nothingness prevailed. The heavens were inactive and any action was meaningless. Earth and the other cosmic entities laid barren. Despite being dominated by darkness, Atabey herself failed to notice that this universe was incomplete. Eventually she decided to create two new deities, Yucáhu and Guacar, from magic and intangible elements. Atabey now felt confident that her creation could be completed and left it in charge of her sons. Yucáhu took over as a creation deity, becoming a universal architect and gathering the favour of his mother. From his dwelling in the heavens, he contemplated and awoke the Earth from its slumber. As part of this process, two new deities emerged from a cave. Boinael and Maroya, controlling the sun and moon respectively, which were tasked with illuminating the new world day and night.” ref

“Hahgwehdiyu is the Iroquois god of goodness and light, as well as a creator god. He and his twin brother Hahgwehdaetgah, the god of evil, were children of Atahensic the Sky Woman (or Tekawerahkwa the Earth Woman), whom Hahgwehdaetgah killed in childbirth.” ref

Keri and Kame (Bakairi Twin Creator Gods)

“Type: Indian culture hero, creator god, transformer, magical twin, Related figures in other tribes: Mopo and Ikujuri (Apalai).” ref

“Ikujuri and Mopo are the “Two” Creator gods of the Apalai and Wayana tribes. Together, they created humans, adapted the world for them to live on, and taught them Native culture. Related figures in other tribes: Keri and Kami (Bakairi).” ref

“Makunaima: High God, Creator, “God” or “Great Spirit” but not personified. Tribal affiliation: Akawaio, Pemon, Macusi, Carib. Related figures in other tribes: Kururumany (Arawak). The Sun, the Frog, and the Fire-Sticks: A Guyanese Carib legend about Makunaima and his twin brother Pia.” ref

“Mopo and Kujuri are the “Two” Creator gods of the Apalai tribe. Together, Mopo and his brother created humans, adapted the world for them to live on, and taught them Apalai culture. Related figures in other tribes: Keri and Kame (Bakairi).” ref

“Sky Woman (Ataensic, Atahensic, Ataentsic): Mother goddess, Sky spirit, Grandmother Moon, the Woman Who Fell from the Sky=Earth-Diver. Sky Woman is the Iroquois mother goddess who descended to earth by falling through a hole in the sky. She is either the grandmother or mother of the twin culture heroes Sky-Holder and Flint, sometimes known as Good Spirit and Bad Spirit.” ref

Kokumthena – Blackfoot tribe

“Kokumthena is somewhat unique in that she is female (the Blackfoot tribe have a married couple, Old-Man and Old-Lady, in this role; all the other Algonquian tribes we know of have male Transformer figures.) In Shawnee legends, Kokumthena is depicted as an old woman (her name means “our grandmother”). Paboth’kwe (or Papoothkwe) is another Shawnee name for this matriarchal figure, meaning “cloud woman.” Perhaps this may be an indication that she is related to Sky Woman of the Iroquois tribes. Related figures in other tribes: Sky Woman (Iroquois), Nookomis (Anishinabe), Old Lady (Blackfoot), Grandmother Woodchuck (Abenaki), Nogami (Mi’kmaq).” ref

Sky-Holder (Taronhiawagon): Creator, High god

“Sky-Holder is the grandson of Sky-Woman– either the same as or equivalent to the Huron Ioskeha, creator of the human race. In other tribes: Ioskeha (Huron), Good Spirit (Cayuga), Manabush (Anishinabe).” ref

Maple Sapling (Ioskeha, Little Sprout): Magical twin

“In Huron mythology and the mythology of many Iroquois communities, Ioskeha or Maple Sapling is one of the twin grandsons of Ataensic, the Sky Woman. Ioskeha was born normally, while his brother Tawiscara (Flint) burst through his mother’s side and killed her. Related figures in other tribes: Sky Holder (Iroquois), Good Spirit (Cayuga), Nanabozho (Anishinabe).” ref

“Evaki is the Bakairi night goddess, aunt of the twin culture heroes Keri and Kame. Evaki has the responsibility of taking the sun out of the jar it is kept in every morning and putting it back away at night.” ref

Old Man Coyote (Akba Atatdia): Native Creator, high god, coyote spirit

“Coyote played the role of both Creator and trickster in Crow mythology. In some versions of the Crow creation myth there were actually two Coyotes, the Old Man Coyote who created people, animals, and the earth, and a regular Coyote who had adventures and got into trouble. In other versions, they were one and the same.” ref

Piai: Creator god, Medicine spirit, Mythical twin

“In some Carib traditions, Piai is the twin brother of the god Makunaima. They are said to be sons of the Sun. Piai is the father of medicine, and his name has come to mean “medicine man” in many Cariban languages.” ref

“Amalivaca is a benevolent transformer-type demigod from the mythology of the Tamanac and other Cariban tribes. Amalivaca shapes the world for the Caribs and teaches them how to live. In some Carib traditions he is known as Sigu or Sigoo and considered to be the son of the high god Tamosi; in others, he has a twin brother named Vochi who helps him in his work. Related figures in other tribes: Sigo (Akawaio), Kururumany (Arawak).” ref

“Charred Body is a Hidatsa hero who led the people to the earth from their original home in the sky. Charred Body was the uncle of the sacred twins Lodge-Boy and Thrown-Away. In some Crow legends his name is given as the father of the sacred twins, without the Hidatsa story of migration and murder.” ref

Qone: Transformer, Culture hero, Moon god

“Qone is a Transformer figure, a type of hero common to the mythology of many Northwest Coast tribes. He changed himself into the moon and his younger brother into the sun. Many Native storytellers today refer to the two magical heroes interchangeably. In other tribes: Suku (Alsea), Cikla (Chinook).” ref

Glooskap “liar”

“Glooscap is the benevolent culture hero of the Wabanaki tribes of northeast New England. And sometimes also had a brother (either an older brother Mikumwesu or Mateguas, a younger brother Malsom, or an adopted brother Marten.) According to legend, Glooscap got this name after lying about his secret weakness to an evil spirit (in some stories, his own brother) and therefore escaping from a murder plot.” ref

The Miraculous Twins

“South American legend about the birth and life of the Bakairi Indian gods Keri and Kame.” ref

Shikla (Cikla)

“Shikla is a Transformer type of hero common to the mythology of many Northwest Coast tribes. In some versions, there was one Shikla, while in others, there were two. Related figures in other tribes: Seuku (Alsea), Qone (Chehalis).” ref

Wisakedjak (Wesakechak): Culture hero, Transformer, trickster

“Wisakedjak is the benevolent culture hero of the Cree tribe. Wisakedjak was specifically created by the Great Spirit to be a teacher for humankind. In others, he was the divine son of the Earth. And in other legends, he was the son of a Rolling Head monster, who was forced to kill his violent mother to survive. In many traditions Wisakedjak’s younger brother was the Wolf, Mahihkan, who was killed by Water Lynxes or Horned Serpents, earning them the bitter enmity of Wisakedjak.” ref

Wisaka (Wizaka): Culture hero, Transformer, trickster

“Wisaka is the benevolent culture hero of the prairie Algonquian tribes. The details of Wisaka’s life vary somewhat from community to community. Most often he is said to have been directly created by the Great Spirit. (Some Kickapoo communities in Mexico identify Wisaka as the son of the Great Spirit, though this may be an influence from Christianity.) In other traditions, Wisaka is born of a virgin mother and raised by his Grandmother Earth. In some stories Wisaka is said to have created the first humans out of mud, while in others, the Great Spirit created people modelled on Wisaka, who then became their Elder Brother. In many tribal traditions, Wisaka has a younger brother named Chipiapoos or Yapata, who was killed by water spirits and became the ruler of the dead. Related: Wesakechak (Cree), Nanabojo (Anishinabe), Glooscap (Wabanaki), Napi (Blackfoot).” ref

“The Spider Twins: Achumawi story about a family of spiders helping the animals to end winter.” ref

“Achumawi (of northeastern California) housing, food sources, and seasonal movements therefore also varied. In the summer, the Achomawi band, and other upper Pit River bands usually lived in cone-shaped homes covered in tule-mat and spent time under shade or behind windbreaks of brush or mats.They have a patrilineal society, with inheritance and descent passed through the paternal line. The traditional chiefdom was handed down to the eldest son. When children were born, the parents were put into seclusion and had food restrictions while waiting for their baby’s umbilical cord to fall off. If twins were born, one of them was killed at birth.” ref

Achumawi Religion

“Adolescent boys sought guardian spirits called tinihowi and both genders experienced puberty ceremonies. A victory dance was also held in the community, which involved the toting of a head of the enemy with women participating in the celebration. Elder men would fast to increase the run of fish and women and children would eat out of sight of the river to encourage fish populations. Spiritual presences were identified with mountain peaks, certain springs, and other sacred places.” ref

“Achomawi shamans maintained the health of the community, serving as doctors. Shamans would focus on “pains” which were physical and spiritual. These pains were believed to have been put on people by other, hostile shamans. After curing the pain, the shaman would then swallow it. Both men and women held the role of shaman. A shaman was said to have a fetish called kaku by Kroeber or qaqu by Dixon. Kroeber relied upon Dixon’s work in this part of California. (The letter q was supposed to represent a velar spirant x, as in Bach, in the system generally used at that time for writing indigenous American languages. The Achumawi Dictionary does not have this word.) Dixon described the qaqu as a bundle of feathers which were believed to grow in rural places, rooted in the earth, and which, when secured, dripped of blood constantly. It was used as an oracle to locate pains in the body. Quartz crystal was also revered within the community and was obtained by diving into a waterfall. In the pool in the waterfall the diver would find a spirit (like a mermaid) who would lead the diver to a cave where the crystals grew. A giant moth cocoon, which symbolized the “heart of the world”, was another fetish, and harder to obtain.” ref

“In their networks with neighboring cultures Achomawi exchanged their furs, basketry, steatite, rabbit-skin blankets, food and acorn in return for goods such as epos root, clam beads, obsidian and other goods. Through these commercial dealings goods from the Wintun (iqpiimí – ″Wintun people″, númláákiname – Nomlaki (Central Wintu people)), Modoc and possibly the Paiute (aapʰúy – ″stranger″) were transported by the Achomawi. Eventually they would also trade for horses with the Modoc. The Achomawi used beads for money, specifically dentalia.” ref

Achomawi Puberty rites

“A girl would begin her puberty ritual by having her ears pierced by her father or another relative. She would then be picked up, dropped, and then hit with an old basket, before running away. During this part, her father would pray to the mountains for her. The girl would return in the evening with a load of wood, another symbol of women’s roles within the community, like the basket. She would then build a fire in front of her house and dance around it throughout the night, with relatives participating; around the fire or inside the house. Music would accompany the dance, made by a deer hoof rattle. During the ritual time, she would have herbs stuffed up her nose to avoid smelling venison being cooked. In the morning, she would be picked up and dropped again, and she would run off with the deer hoof rattle. This repeated for five days and nights. On the fifth night, she would return from her run to be sprinkled with fir leaves and bathed, completing the ritual.” ref

“Boys’ puberty rites were similar to the girls ritual but adds shamanistic elements. The boys ears are pierced, and then he is hit with a bowstring and runs away to fast and bathe in a lake or spring. While he is gone, his father prays for the mountains and the Deer Woman to watch over the boy. In the morning, he returns, lighting fires during his trip home and eats outside the home and then runs away again. He stays several nights away, lighting fires, piling up stones and drinking through a reed so that his teeth would not come into contact with water. If he sees an animal on the first night in the lake or spring or dream of an animal; that animal would become his personal protector. If the boy has a vision like this, he will become a shaman.” ref

The First Rainbow (with Spider Woman, Coyote, Silver Gray Fox, and the Spider Twins) – Achomawi Myth

“Sixty little spider children shivered as they slept. The snow had fallen every day for months. All the animals were cold, hungry, and frightened. Food supplies were almost gone. No one knew what to do. Blue Jay and Redheaded Woodpecker sang and danced for Silver Gray Fox, the creator, who floats above the clouds. Since Silver Gray Fox, had made the whole world with a song and a dance, Blue jay and Woodpecker hoped to be answered with blue skies. But the snow kept falling.” ref

“Finally, the animals decided to ask Coyote. Coyote had been around a long time, almost since the beginning. They thought that he might know how to reach Silver Gray Fox. They went to the cave where Coyote was sleeping, told him their troubles, and asked for help. “Grrrrowwwlll…go away,” grumbled Coyote, “and let me think.” ref

“Coyote stuck his head into the cold air outside and thought till he caught an idea. He tried singing in little yelps and loud yowls to Silver Gray Fox. Coyote sang and sang, but Silver Gray Fox didn’t listen, or didn’t want to. After all, it was Coyote’s mischief-making when the world was new that had caused Silver Gray Fox to go away beyond the clouds in the first place. Coyote thought he’d better think some more.” ref

“Suddenly he saw Spider Woman swinging down on a silky thread from the top of the tallest tree in the forest. Spider Woman’s been on Earth a long, long time, Coyote thought. She’s very wise. I’ll ask her what to do. Coyote went to the tree and lifted his ears to Spider Woman. “Spider Woman, O wise weaver, O clever one,” called Coyote in his sweetest voice. “We’re all cold and hungry and everyone’s afraid this winter will never end. Silver Gray Fox didn’t seem to notice. Can you help?” asked Coyote.” ref

“Spider Woman swayed her shining black body back and forth, back and forth, thinking and thinking, thinking and thinking. Her eight black eyes sparkled when she spoke, “I know how to reach Silver Gray Fox, Coyote, but I’m not the one for the work. Everyone will have to help. You’ll need my two youngest children, too. They’re little and light as dandelion fluff, and the fastest spinners in my web.” Spider Woman called up to her two littlest ones. “Spinnnnnn! Spinnnnnn!” ref

“They came down fast, each spinning on eight little legs, two fine, black twin Spider Boys, full of curiosity and fun. Spider Woman said, “My dear little quick ones, are you ready for a great adventure?” “Yes! Yes! We’re ready!” they cried. Spider Woman told them her plan, and the Spider Boys set off with Coyote in the snow. They hadn’t gone far when they met two White-Footed Mouse Brothers rooting around for seeds to eat. Coyote told them Spider Woman’s plan. “Will you help?” he asked. “Yes! Yes! We’ll help!” they squeaked.” ref

“So, they all traveled the trail towards Mount Shasta until they met Weasel Man looking hungry and even leaner than usual. Coyote told Weasel Man his plan. “Will you help?” asked Coyote. “Of course,” rasped Weasel Man, who joined them on the trail. Before long they came across Red Fox Woman swishing her big fluffy tail through the bushes. “Will you help?” asked Coyote. “Of course, I’ll come,” crooned Red Fox Woman. Then Rabbit Woman poked her head out of her hole. “I’ll come too.” She sneezed, shivering despite her thick fur.” ref

“Meadowlark wrapped a winter shawl around her wings, and trudged after the others along the trail to the top of Mount Shasta. The snow had stopped, but the sky was still cloudy. On top of Mount Shasta, Coyote barked, “Will our two best archers step forward?” The two White Footed Mouse Brothers proudly lifted their bows. “Everyone listen,” barked Coyote. “If any one of us is only half-hearted, Spider Woman’s plan will fail.” ref

“To get through the clouds to Silver Gray Fox, we must each share our powers, our thoughts, our dreams, our strength, and our songs whole-heartedly. Now, you White-Footed Mouse Brothers, I want you to shoot arrows at exactly the same spot in the sky.” Turning to the others, Coyote said, “Spider Boys, start spinning spider silk as fast as you can. Weasel Man, White-Footed Mouse Brothers, Red Fox Woman, Rabbit Woman, and I will sing and make music. We must sing with all our might or the Spider Boys won’t make it.” “One!” called Coyote. Everyone got ready. “Two!” counted out Coyote. The animals drew in deep breaths.” ref

“The Mouse Brothers pulled back their bowstrings. “Three!” said the Coyote. Two arrows shot straight up and stuck at the same spot in the clouds. “Whiff! Wiff! Wiff Wiff!”, sang the White Footed Mouse Brothers. “Yiyipyipla!”, sang Red Fox Woman. “Wowooooolll!” sang Coyote. Rabbit Woman shook her magic rattle. Weasel Man beat his very old and worn elk-hide drum. The Spider Boys hurled out long lines of spider silk, weaving swiftly with all their legs. The animals sang up a whirlwind of sound to lift the spider silk until it caught on the arrows in the clouds. Then the Spider Twins scurried up the lines of silk and scrambled through the opening. All the while, down below, the animals continued singing, rattling and drumming. The little Spiders sank, breathless, onto the clouds.” ref

“Silver Gray Fox spied them and called out, “What are you two doing here?” The Spider Boys bent low on their little legs and answered. “Silver Gray Fox, we bring greetings from our mother, Spider Woman, and all the creatures of the world below. We’ve come to ask if you’d please let the sun shine again. The whole world is cold. Everyone is hungry. Everyone is afraid spring will not return, ever.” They were so sincere and polite that Silver Gray Fox became gentler, and asked, “How did you two get up here?” ref

“The Spider Boys said, “Listen, can you hear the people singing? Can you hear the drum and rattle?” Silver Gray Fox heard the drum and rattle and the people singing. When the Spider Boys finished telling their story, Silver Gray Fox was pleased and told them, “I’m happy when creatures use their powers together. I’m especially glad to hear that Coyote’s been helping too. Your mother, Spider Woman, made a good plan. To reward all your hard work, I’ll create a sign to show that the skies will clear. And you may also help, but first picture the sun shining bright.” The Spider Boys thought hard and saw the sun sending out fierce rays in all directions.” ref

“Now, where sun rays meet the damp air” said Silver Gray Fox, “Picture a stripe of red, red as Woodpecker’s head. Add a stripe of blue nearby, blue as Blue Jay’s blue.” The Spider Boys thought hard, and great stripes appeared of red and blue. Silver Gray Fox chanted. “Now, in between, add stripes of orange, yellow and green!” The Spider Boys thought of this and dazzling their eyes, a beautiful arc of colors could be seen across the whole sky above the clouds. It was the very first rainbow.” ref

“Meanwhile, down below, beneath the clouds, the animals and people were so cold, hungry, and tired that they had stopped singing and drumming. Spider Woman missed her two youngest children. Each day she missed them more. She blamed Coyote for the trouble. So did the other animals. Coyote slipped away silent, lonely and sad. Above, on the clouds, the twins rested. Their legs ached and their minds were tired. Silver Gray Fox said, “You did what I asked and kept it secret. That’s very difficult, so I’m giving you a special reward. On wet mornings, when the sun starts to shine, you’ll see what I mean.” ref

“Then the Spider Boys spun down to Earth, and ran back to their mother as fast as they could. Spider Woman cried for joy and wrapped all her legs around her two littlest children. Their fifty-eight sisters and brothers jumped up and down with happiness. All the animals gathered around to hear the Spider Boys’ story. When they finished, the Spider Boys cried, “Look up!” Everyone looked up to see that the clouds had drifted apart and there, like a bridge between the earth and the sky was a radiant arch – they could still see the very first rainbow. The sun began to warm the earth. Shoots of grass pushed up through the melting snow.” ref

“Meadowlark blew her silver whistle of spring across the valley, calling streams and rivers to awake. Coyote came out of hiding, and racing to a distant hilltop, he gave a long, long howl of joy. The animals held a great feast to honor the rainbow, Silver Gray Fox, Spider Woman, the Spider Twins, Coyote, and the hard work everyone had done together. To this day, after the rain, when the sun comes out, dewdrops on spider webs shine with tiny rainbows. This is the spiders’ special reward.” ref

Spider Grandmother (Koyangwuti or Kokyangwuti): Hopi or “Old Spider Woman”

“Spider Grandmother is the special benefactor of the Hopi tribe. In the Hopi creation myths, Spider Grandmother created humans from clay (with the assistance of Sotuknang and/or Tawa), and was also responsible for leading them to the Fourth World (the present Earth.) The Spider Woman and the Twins: Hopi legend about the birth of Spider Grandmother and her first creations.” ref

Xōchiquetzal (Her Twin was Xochipilli god) weaving goddess- Aztec

“In Aztec mythology, Xochiquetzal, also called Ichpochtli, meaning “maiden”, was a goddess associated with concepts of fertility, beauty, and female sexual power, serving as a protector of young mothers and a patroness of pregnancy, childbirth, and the crafts practised by women such as weaving and embroidery. In pre-Hispanic Maya culture, a similar figure is Goddess I.

In Classical Nahuatl morphology, the first element in a compound modifies the second, and thus the goddess’ name can literally be taken to mean “flower precious feather”, or ”flower quetzal feather”. Her alternative name, Ichpōchtli, corresponds to a personalized usage of ichpōchtli (“maiden, young woman”).” ref

“Worshippers wore animal and flower masks at a festival, held in her honor every eight years. Her twin was Xochipilli and her husband was Tlaloc, until Tezcatlipoca kidnapped her and she was forced to marry him. At one point, she was also married to Centeotl and Xiuhtecuhtli. By Mixcoatl, she was the mother of Quetzalcoatl. Anthropologist Hugo Nutini identifies her with the Virgin of Ocotlan in his article on patron saints in Tlaxcala. she was also the aztec goddesss called the great goddess or teotihuacan spider woman.” ref

Diana Roman twin goddess of hunt

“Diana (short for: deivā Jāna, literally: the Divine Jana) is the Roman goddess of hunt. She is one of a pair of twins born to Apollo. Her twin brother was Janus. She preferred to stay on Earth, roaming the wilderness with her nymph companions, suiting her role as goddess of the hunt. She was also the goddes of the moon and childbirth. The name Diana is cognate to Zeus, Dyaus, and Jupiter. Diana is also heavily related to the goddesses Trivia and Luna, as originally they were aspects of Diana herself – a triple goddess through and through. During the middle ages and because of the goddess’s relation to women and to the underworld through her aspect (Trivia), she became an icon for witches and there were even new myths written about her by modern Wiccans and pagans – such as the story of Aradia.” ref

“Diana is equated with the Greek goddess Artemis, and absorbed much of Artemis’ mythology early in Roman history, including a birth on the island of Delos to parents Jupiter and Latona, and a twin brother, Apollo.” ref

The Celestial Jaguar – Tupi-Guarani

“According to a version of the legend, the mother of the heavenly twins, known as Sun and Moon, was killed by the Celestial Jaguars. The twins were raised by the jaguars until a bird told them how their mother had been killed. The twins went on a rampage, killing all jaguars except one which was pregnant and the mother of today’s primitive jaguars. Now, jaguars are a wild beast that are to be feared by the Guarani. It is common for the animal to be part of the beginning and end of a person’s life. The meat will be eaten by a child’s mother while she is pregnant and the jaguars themselves represent the souls of the dead in temples. Those that are sick, elderly, and slow-moving have also been known to have been left behind to the jaguars.” ref

“In classical antiquity, Cancer was the location of the Sun on the northern solstice (June 21). During the first century CE, axial precession shifted it into Gemini. In 1990, the location of the Sun at the northern solstice moved from Gemini into Taurus, where it will remain until the 27th century CE and then move into Aries. The Sun will move through Gemini, next, from June 21 to July 20 through 2062.” ref

“Gemini is prominent in the winter skies of the northern Hemisphere and is visible the entire night in December–January. The easiest way to locate the constellation is to find its two brightest stars Castor and Pollux eastward from the familiar V-shaped asterism (the open cluster Hyades) of Taurus and the three stars of Orion’s Belt (Alnitak, Alnilam, and Mintaka). Another way is to mentally draw a line from the Pleiades star cluster located in Taurus and the brightest star in Leo, Regulus. In doing so, an imaginary line that is relatively close to the ecliptic is drawn, a line which intersects Gemini roughly at the midpoint of the constellation, just below Castor and Pollux. When the Moon moves through Gemini, its motion can easily be observed in a single night as it appears first west of Castor and Pollux, then aligns, and finally appears east of them.” ref

“In Babylonian astronomy, the stars Castor and Pollux were known as the Great Twins. The Twins were regarded as minor gods and were called Meshlamtaea and Lugalirra, meaning respectively ‘The One who has arisen from the Underworld’ and the ‘Mighty King’. Both names can be understood as titles of Nergal, the major Babylonian god of plague and pestilence, who was king of the Underworld.” ref

“In Greek mythology, Gemini was associated with the myth of Castor and Pollux, the children of Leda and Argonauts both. Pollux was the son of Zeus, who seduced Leda, while Castor was the son of Tyndareus, king of Sparta and Leda’s husband. Castor and Pollux were also mythologically associated with St. Elmo’s fire in their role as the protectors of sailors. When Castor died, because he was mortal, Pollux begged his father Zeus to give Castor immortality, and he did, by uniting them together in the heavens.” ref

“Gemini is dominated by Castor and Pollux, two bright stars that appear relatively very closely together forming an o shape, encouraging the mythological link between the constellation and twinship. The twin above and to the right (as seen from the Northern Hemisphere) is Castor, whose brightest star is α Gem; it is a second-magnitude star and represents Castor’s head. The twin below and to the left is Pollux, whose brightest star is β Gem (more commonly called Pollux); it is of the first magnitude and represents Pollux’s head. Furthermore, the other stars can be visualized as two parallel lines descending from the two main stars, making it look like two figures. H. A. Rey has suggested an alternative to the traditional visualization that connected the stars of Gemini to show twins holding hands.” ref

“In Chinese astronomy, the stars that correspond to Gemini are located in two areas: the White Tiger of the West (西方白虎, Xī Fāng Bái Hǔ) and the Vermillion Bird of the South (南方朱雀, Nán Fāng Zhū Què). In some cultures, the twin in Gemini refers to ‘the unborn twin’ and represents a spiritual or dual self that exists within. The modern constellation Gemini lies across two of the quadrants, symbolized by the White Tiger of the West (西方白虎, Xī Fāng Bái Hǔ) and the Vermilion Bird of the South (南方朱雀, Nán Fāng Zhū Què), that divide the sky in traditional Chinese uranography. The name of the western constellation in modern Chinese is 雙子座 (shuāng zǐ zuò), meaning “the twin constellation.” ref, ref

The Divine Twins

“Gemini, the sign of The Divine Twins. We can find the concept of The Divine Twins around the world. It is a powerful concept that, like its astrological equivalent, Gemini, takes on many forms. The Twins are depicted as two beings. Men, women. A man and woman. Two figures with multiple genders, or are beyond gender. Moreover, they are often interchangeable, with interchangeable genders, roles, and powers. I cannot say with any certainty which of these concepts was “first,” but it doesn’t matter, as they all illuminate facets in each other.” ref

Nearly all ancient civilizations recognized biologically occurring twins as holy, unique, blessed, or cursed.

“Whether identical, fraternal or conjoined, the birth of a set of twins was a significant occasion. There are many superstitions around twins. Many groups see twins as “astral” in nature, coming from or affiliated with “the stars.” However, as Holy archetypes go, the Twins are almost always closer in their behavior and habits to humanity than many many other deities.” ref

“There are some nearly universal consistencies among the holy Twins we see in various myths and religions around the planet. Duality and multiplicity are at the heart of much of our Twin symbolism. Further, almost all Twins represent polarities, and two sides of the same coin; light/dark, good/evil, mortal/divine, male/female, etc.” ref

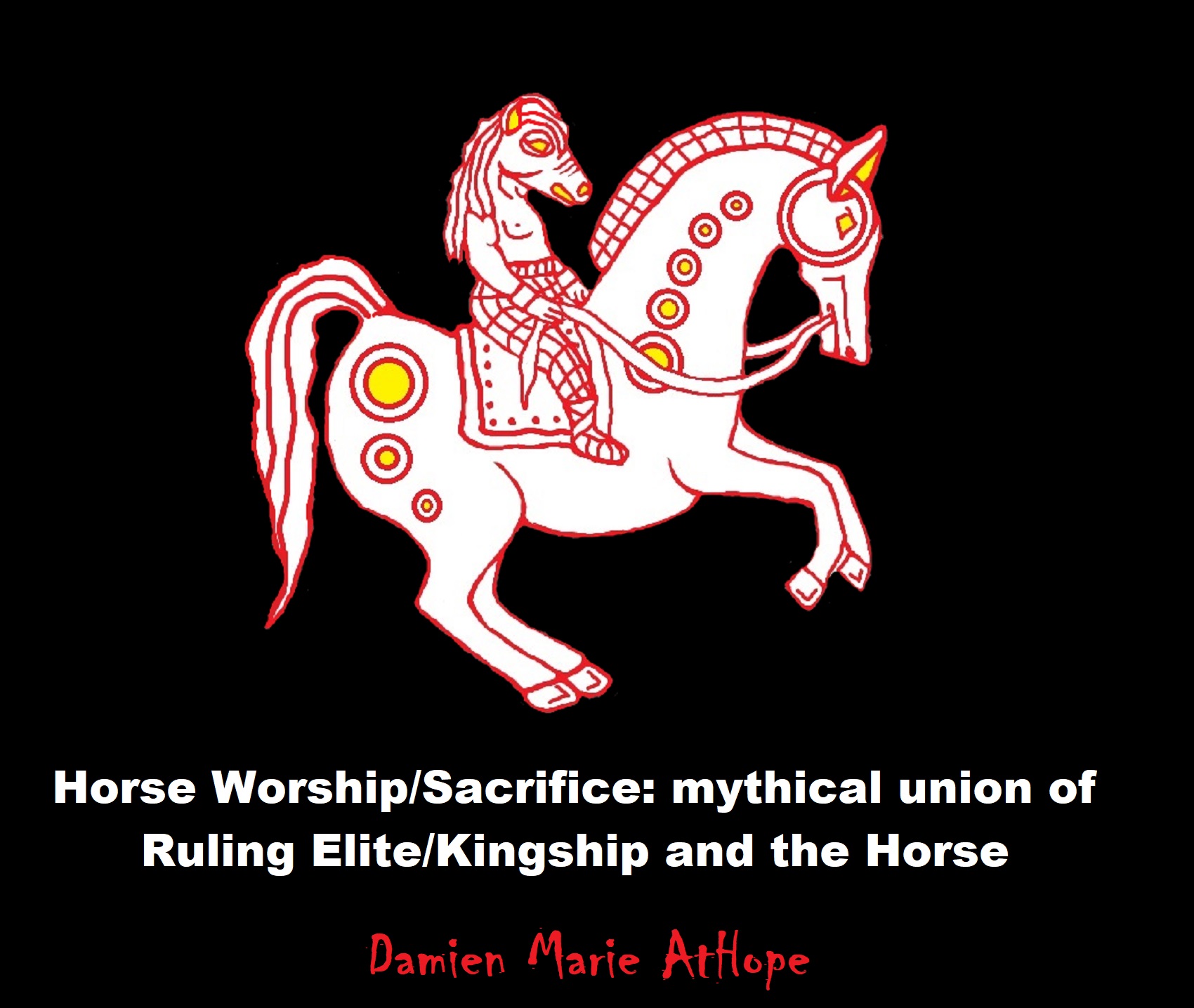

Another symbol connected to Gemini and the Divine Twins is the horse.

“Even the Pegasus and the Unicorn connect to the Twins. The famous Greek twins that the constellation Gemini depicts, Castor and Pollux, were known far and wide for their horsemanship. Other twins have mothers or fathers associated with horses. Epona, for example, is a Gaulish/Celtic Horse Goddess who ran a race against horses and won. She then died on the finish line as She gave birth to twins. The good folks of Mackinac Island in Michigan still worship Her every year in late Spring. The island allows no cars. Horses are still the main form of transportation.” ref

Many Divine Twins have split parentage.

“Many myths feature one mother and two fathers. Or, the twins are born in two different ways, with one born naturally and one coming from an egg or some other unusual source. This split parentage speaks directly to the duality nature of these archetypes. Even from their genesis they are the same but different. Often their Holy parent is a Sky-Related Deity, like storm, air, lightning, wind, thunder, and in particularly Sun Deities. Many Twins are the natural siblings and dual protectors of Solar Maidens in particular.” ref

The Mayan Hero Twins

“The Mayan Hero Twins are named Hunahpu (One-Blowgunner) and Xbalanque (Jaguar-Sun, Jaguar-Deer, or Hidden-Sun). These Twins are a great example of twins that include many symbols of this archetype. They represent complimentary forces – life/death, sky/earth, day/night, sun/moon, male/female. Also, the twins experienced a harsh pregnancy and upbringing. They often use cleverness or trickery to solve their problems.” ref

“The twins are bird hunters and known for their hypnotic dances. While fighting the God Seven Macaw (Vucub Caquix), Hunahpu loses an arm (Gemini rules arms). At one point in their myth, they challenge the Gods to a game to retrieve the head and body of their father. All in all, the Gods pull many tricks on them, including attempting to kill the twins. The Gods succeed, but the twins are brought back to life in a river. At another point in the myth, one twin loses his head but continues to play ball. Ultimately, the twins win; they retrieve their father’s body and kill the Gods.” ref

Yoruba Divine Twins

“In Yoruba land pantheons, the Orishas Ibeji are the Holy Twins. In the diaspora Yoruba of Latin America, these twins are equal to same as Saints Cosmas and Saint Damian. Yoruba land peoples believe twins are magical. And the great ancestor God-Father Shango, who oversees thunder, lightning, justice, dance, and virility guards them. In these communities, if one twin dies, it is a bad omen, not only for the family but for the community as well. The family will ask a Babalawo (an Ifa Priest) to carve a wooden replacement for the lost twin. The family then dresses it and cares for it as a member of the family. In their myth, the 1st twin is Taiwo, 2nd is Kehinde (Omokehinde), the elder. The 2nd twin is the older twin. Taiwo goes first to make sure the world is fit for Kehinde.” ref

“For the Dahomey people, this was Lisa and Mawu, the twin/lovers who birthed the universe together over four days as the androgynous figure Mawu-Lisa. And the Dogon Tribe sees them as the Nummo Twins, who are both androgynous and hermaphroditic. Both figures express any, all and no genders, in turn. The Nummo Twins are Shapeshifters and connected to the Serpent. They are usually depicted as Conjoined twins and are described as the Mothers of the Earth.” ref

“In Haitian Vodoun, these twins are Marassa Jumeaux. They are polygendered children, but more ancient than any Loa. They represent and govern issues concerning astronomical and astrological learning, divine power vs. human impotence, justice, truth, reason, and mystery.” ref

The European world also has its Divine Twins

- “The Latvian Dieva dēli, who were the sons of God

- Sicilian Palici; one legend claims the Palici are the sons of Zeus, or possibly Hephaestus, but another story insists the Palici were the sons of the Sicilian deity Adrianus.Ancients associated them with geysers and the underworld.

- Germanic Gods Alcis, a pair of young male brothers worshiped by the Naharvali.

- Italian Wolf-Gods Romulus and Remus, whose story tells the events that led to the founding of Rome.

- Anglo-Saxon warrior brothers Hengist and Horsa, who’s names mean “Stallion” and “Horse” respectively.

From Wikipedia: “On farmhouses in Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein, horse-head gables were referred to as “Hengst und Hors” as late as around 1875. Rudolf Simeknotes that these horse-head gables can still be seen today, and says that the horse-head gables confirm that Hengist and Horsa were originally considered mythological, horse-shaped beings. Martin Litchfield West comments that the horse heads may have been remnants of pagan religious practices in the area.” - Norse Freyr and Freyjawere the twin son and daughter of the Sea God, Njord. Both were deities of fertility.

- Slavic Lada and Lado, female and male personifications of beauty and fertility who were seen as twins, and as mother and son.

- Welsh Lleu Llaw Gyffes and Dylan ail Don, twin brothers who are born when Arianrhod is tested for virginity. Dylan takes on the nature of a sea creature when he comes into contact with water, while Lleu is related to the pan-Celtic plural hero god Lugus. In the related Irish story of the birth of Lugh Lámfada, one version indicates that Lugh was a surviving triplet, whose twin brothers were drowned. Some interpreters of the legend view Dylan as representing darkness and Llew connected to light.” ref

The Solar connection is essential and oft repeated.

“Many, many religions and myth cycles have an image of The Sun being pulled across the sky by a chariot drawn by two horses. Often the horses are twins or exact opposites from each other. For example, the Chariot card from Tarot depicts this image nicely. Interestingly, the Chariot card connects to Cancer, the sign directly after Gemini.” ref

“In particular, The Twins have some specific roles they play in nearly every myth around the world:

-Protectors at Sea

-Battle Protectors

-Protecting Oaths and Contracts

-Magical Healers

-Fertility

-Assisting at Birth

-Dances and Dancing

-Founding Cities

Ultimately, in true Gemini style, The Divine Twins stand for multifold experiences.” ref

“The Divine Twins represent the duality and multiplicity we experience as we shed old forms of ourselves. We are that person, but they are dying. We are the new person, but they’re not quite here yet. And we are the beings in between, shapeshifting and shedding skins.” ref

“They express the camaraderie we feel when we find our “twin” in a stranger, who suddenly becomes a best friend, a best Judy, a “sister from another mister” or “a brother from another mother.” Maybe we actually look alike, but often what we mean by this phrase is that this person feels that close to us, like someone who knows us better than we know ourselves, knows us from the inside out, and thinks about and sees the world just like us.” ref

“You share clothes, you share lovers, you share passwords. These are our “ride or die bitches,” and we often get into some of our craziest capers with them. We might feel like we would sacrifice a lot for them. We might even face (or tempt) death with them. They see our struggles, they see where we screw up, they see our messy, and they are here for all of it.” ref

The Divine Twins are also two people after union. They became a single being, and now have parted again, but with an intimate knowledge of each other.

“There is the experience of seeing ourselves in other people, and there is also the experience of seeing other people in ourselves. The Divine Twins represent the duality and multiplicity we experience as we shed old forms of self and reveal new ones during personal growth work like self-care, cord-cutting, and other profoundly altering ritual forms. There is our current self, but they are changing. Also, we’re the new person forming, but they’re not quite here yet. And we are the beings in between, shapeshifting and shedding skins.” ref

The Divine Twins also represent a profoundly holy concept. As above, so below.

“One twin divine, one twin mortal. These are the polarities of ourselves. Our mundane, extremely faulty mortal self is, in fact, the twin of our divine self, our soul, the Holy Guardian Angel, the Ka, etc. These are the same, but different, but the same. And, as it is expressed in spiritual practices stretching back through time, if you affect the spiritual body the mortal body will feel it, but also that the inverse is true. If you affect the mortal body, the spiritual twin will react.” ref

“And in the rhythmic pulse of infinite phases experienced while moving between these two extremes – mortal and holy – we discover our lives. Who we are. What we are. How we deal with and integrate the blessings and hardships introduced by our spiritual battles and our mortal experiences. The Sun, balanced between to spinning wheels. Along with the Chariot card, we can work with The Lovers card, as it is ruled by Gemini, and is a fantastic magical image for all these ideas.” ref

“This is the deep magical teaching of working with the Divine Twins as we leave Spring and Beltane season and head into Summer. Finally, we are getting some feedback on our full immersion of the real world. Being born unto the Earth plane, we are married to the consequences of our actions. We are married to reality. And now we are meeting our real world self, and learning to love them.” ref

“Most of the old Pagan religions in Europe were part of an original source: Proto-Indo-European religion. We can discover how the primordial religion looked like by comparing myths of different cultures and ethnic groups. Through this method, scholars have been able to reconstruct the entire pantheon of the primeval gods and goddesses.” ref

“One of the central figures in the Indo-European pantheon is the Sky Father. He is also known by his reconstructed Proto-Indo-European term, *Dyeus. The patriarch of the gods has an intricate web of family relatives — as it is well evinced, for example, through both Vedic and Greek mythologies. Among these relatives, the sons of *Dyeus are probably the most relevant ones. They are the divine Twins.” ref

“There is an unusual academic consensus around the ancient Indo-European origins of the divine Twins. It is considered one of the few original myths within the primordial Proto-Indo-European pantheon. We can find the same divine Twin figures in Greek, Vedic, Roman and Baltic mythology. They are the original “Sons of God.” ref

Creation Myth of Twins

“Key figures in Dogon religion are the twins Nummo and Nommo, primal spirits of Dogon ancestors, sometimes seen as deities. These are hermaphroditic water creatures, seen similarly to water deities (to-vodun) in West African vodun; they can be depicted with a human body and a fish tail. Nommo is supposed to be the first living creature created by the supreme god Amma. Shortly after his creation, Nommo spawned into four pairs of twins, with one pair defying the order established by creator Amma. To restore order, the god Amma sacrificed another creature, whose body he cut up and scattered throughout creation. A shrine for the god Amma was to be built at each place where a fragment of the body landed.” ref

“The cult of the god Amma – like the entire Dogon religion – is closely tied to the Bandiagara cliff where the Dogon live. The cult of the god Amma is geographically defined by this cliff, it is not practiced elsewhere. The Bandiagara cliff is a sandstone terrain fault approximately 150 km long, reaching a height of up to 500 m in some places. The Dogon inhabit mud villages built on the upper edge of the cliff, villages directly attached to the cliff at its lower edge, but also at various heights in the wall, also villages scattered under the cliff, and a labyrinth of caves right in the cliff. The architecture of the villages and the religiously motivated urban arrangement of mud houses centered on the hogon priestly building is unique in the context of the whole of Africa. The Dogon language forms an independent branch of the Niger-Congo language family and is not closely related to any other language.” ref

“Legend says that a long time ago in China there were immortal twins, one who brought harmony and the other, union. So artists made figurines showing the twin brothers, called ”He-He. ” They often were pictured and given to brides, because it was thought they brought a happy marriage.” ref

“He-He Er Xian, translated as the Immortals of Harmony and Union and as the Two gods of Harmony and Union, are two Taoist immortals. They are popularly associated with happy marriages. He and He are typically depicted as boys holding a lotus flower (荷, hé) and a box (盒, hé). There are a number of legendary tales behind two celestial beings of He and Ho, among them there is one regarding the two monks living a secluded life in Tiantai Mountain in the Tang dynasty by the name of Hanshan and Shide and no one know about their subsequent whereabouts. The story is based on Poems of Hanshan and Shide composed by Lv Qiuyin. They were officially canonized as the God of Harmony and the God of Good Union in the first year of Yongzheng rule in the Qing dynasty. They are widely regarded as gods who bless love between husband and wife.” ref

“The Divine Twins are youthful horsemen, either gods or demigods, who serve as rescuers and healers in Proto-Indo-European mythology. Like other Proto-Indo-European divinities, the Divine Twins are not directly attested by archaeological or written materials, but scholars of comparative mythology and Indo-European studies generally agree on the motifs they have reconstructed by way of the comparative method.” ref

Common traits

“Scholar Donald Ward proposed a set of common traits that pertain to divine twin pairs of Indo-European mythologies:

- dual paternity;

- mention of a female figure (their mother or their sister);

- deities of fertility;

- known by a single dual name or having rhymed/alliterative names;

- associated with horses;

- saviours at sea;

- of astral nature;

- protectors of oaths;

- providers of divine aid in battle; and

- magic healers.” ref

“Although the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) name of the Divine Twins cannot be reconstructed with certainty based on the available linguistic evidence, the most frequent epithets associated with the two brothers in liturgic and poetic traditions are the “Youthful” and the “Descendants” (sons or grandsons) of the Sky-God (Dyēus). Two well-accepted reflexes of the Divine Twins, the Vedic Aśvins and the Lithuanian Ašvieniai, are linguistic cognates ultimately deriving from the Proto-Indo-European word for the horse, *h1éḱwos. They are related to Sanskrit áśva and Avestan aspā (both from Indo-Iranian *Haćwa), and to Old Lithuanian ašva, which all share the meaning of “mare“. This may point to an original PIE divine name *h1éḱw-n-, although this form could also have emerged from later contacts between Proto-Indo-Iranian and Proto-Balto-Slavic speakers, which are known to have occurred in prehistoric times.” ref

“Represented as young men rescuing mortals from peril in battle or at sea, the Divine Twins rode the steeds that pull the sun across the sky and were sometimes depicted as horses themselves. They shared a sister, the Dawn (*H2éwsōs), who is also portrayed as the daughter of the Sky-God (*Dyēus) in Indo-European myths. The two brothers are generally depicted as healers and helpers, travelling in miraculous vehicles to save shipwrecked mortals. They are often differentiated: one is represented as a physically strong and aggressive warrior, while the other is seen as a healer who rather gives attention to domestic duties, agrarian pursuits, or romantic adventures.” ref

“In the Vedic, Greek and Baltic traditions, the Divine Twins similarly appear as the personifications of the morning and evening star. They are depicted as the lovers or the companions of a solar female deity, preferably the Sun’s daughter but sometimes also the Dawn. In the majority of the stories where they appear, the Divine Twins rescue the Dawn from a watery peril, a theme that emerged from their role as the solar steeds. During the night, the Divine Twins were said to return to the east in a golden boat, where they traversed a sea to bring back the rising sun each morning. During the day, they crossed the nocturnal sky in pursuit of their consort, the morning star. In what seems to be a later addition confined to Europe, they were said to take a rest at the end of the day on the “Isles of the Blessed”, a land seating in the western sea which possessed magical apple orchards. By the Bronze Age, the Divine Twins were also represented as the coachmen of horse-driven solar chariots.” ref

“The Gaulish Divanno [de] and Dinomogetimarus are said to be protective deities and “the Gallic equivalents” of the Greek Dioskouroi. They seem to be represented in monuments and reliefs in France flanked by horses, which would make them comparable to Gaulish Martes and the Germanic Alcis. Scholars suggest that the numerous Gallo-Roman dedicatory epigraphs to Castor and Pollux, more than any other region of the Roman Empire, attest a cult of the Dioskoroi. Greek historian Timaeus mentions that Atlantic Celts venerated the “Dioskouroi” above all other gods and that they [Dioskouroi] had visited them from across the Ocean. Historian Diodorus Siculus, in the fourth book of Bibliotheca historica, writes that the Celts who dwelt along the ocean worshipped the Dioscuroi “more than the other gods”. The conjecture that it refers to the Gallic gods Divanno and Dinomogetimarus has no firm support.” ref

“In one of the Irish myths involving Macha (the Dindsenchas of Ard Macha), she is forced to race against the horses of King of Ulster while in late pregnancy. As a talented rider, she wins the race but starts giving birth to Fír and Fial immediately after crossing the finish line. The archetype is also partly matched by figures such as the Gallic sun god Belenus, whose epithet Atepomarus meant “having good horses”; Grannus, who is associated with the healing goddess Sirona (her name means “star”); Maponos (“Son of God”), considered in Irish mythology as the son of Dagda, associated with healing, The Welsh Brân and Manawydan may also be reflexes of the Divine Twins.” ref

“Comparative mythologist Alexander Haggerty Krappe suggested that two heroes, Feradach and Foltlebar, brothers and sons of the king of Innia, are expressions of the mytheme. These heroes help the expedition of the Fianna into Tir fa Thuinn (a realm on the other side of the sea), in a Orphean mission to rescue some of their members, in the tale The pursuit of the Gilla Decair and his horse. Both are expert navigators: one can build a ship and the other can follow the wild birds. Other possible candidates are members of Lugh‘s retinue, Atepomarus and Momorus (fr). Atepomarus is presumed to mean “Great Horseman” or “having great horses”, based on the possible presence of Celtic stem -epo- ‘horse’ in his name. Both appear as a pair of Celtic kings and founders of Lugdunum. They escape from Sereroneus and arrive at a hill. Momorus, who had skills in augury, sees a murder of crows and names the hill Lougodunum, after the crows. This myth is reported in the works of Klitophon of Rhodes and in Pseudo-Plutarch‘s De fluviis.” ref

“The Polish deities Lel and Polel, first mentioned by Maciej Miechowita in 1519, are presented as the equivalents of Castor and Pollux, the sons of the goddess Łada (counterpart of the Greek Leda) and an unknown male god. An idol was found in 1969 on the Fischerinsel island, where the cult centres of the Slavic tribe of Veleti was located, depicting two male figures joined with their heads. Scholars believe it may represent Lel and Polel. Lelek means “strong youth” in Russian dialect. The brightest stars of the Gemini constellation, α Gem and β Gem, are thought to have been originally named Lele and Polele in Belarusian tradition, after the twin characters. According to Polish professor of medieval history, Jacek Banaszkiewicz, the two Polabian gods, Porevit and Porenut, manifest dioscuric characteristics. According to him, the first part of their names derives from a Proto-Slavic root -por meaning “strength,” with first being “Lord of strength” – the stronger one, and the other “Lord in need of support (strength)” – the weaker one. They both have five faces each and appear alongside Rugiaevit, the chief god.” ref

“During childbirth, the mother of the Polish hero twins Waligóra (“Mountain Beater”) and Wyrwidąb (“Oak Tearer”) died in the forest, where wild animals took care of them. Waligóra was raised of by a she-wolf and Wyrwidąb by a she-bear, who fed them with their own milk. Together, they defeated the dragon who tormented the kingdom, for which the grateful king gave each of them half of the kingdom and one of his two daughters as a wife. The sons of Krak: Krak II and Lech II also appear in Polish legends as the killers of the Wawel dragon. Amphion and Zethus, another pair of twins fathered by Zeus and Antiope, are portrayed as the legendary founders of Thebes. They are called “Dioskouroi, riders of white horses” (λευκόπωλοι) by Euripides in his play The Phoenician Women (the same epithet is used in Heracles and in the lost play Antiope). In keeping with the theme of distinction between the twins, Amphion was said to be the more contemplative, sensitive one, whereas Zethus was more masculine and tied to physical pursuits, like hunting and cattle-breeding.” ref

“The mother of Romulus and Remus, Rhea Silvia, placed them in a basket before her death, which she put in the river to protect them from murder, before they were found by the she-wolf who raised them. The Palici, a pair of Sicilian twin deities fathered by Zeus in one account, may also be a reflex of the original mytheme. Greek rhetorician and grammar Athenaeus of Naucratis, in his work Deipnosophistae, Book II, cited that poet Ibycus, in his Melodies, described twins Eurytus and Cteatus as “λευκίππους κόρους” (“white-horsed youths”) and said they were born from a silver egg, a story that recalls the myth of Greek divine twins Castor and Pollux and their mother Leda. This pair of twins was said to have been fathered by sea god Poseidon and a human mother, Molione.” ref

“Another possible reflex may be found in Nakula and Sahadeva. Mothered by Princess Madri, who summoned the Aśvins themselves in a prayer to beget her sons (thus them being called Ashvineya (आश्विनेय)), the twins are two of the five Pandava brothers, married to the same woman, Draupadi. In the Mahabharata epic, Nakula is described in terms of his exceptional beauty, warriorship and martial prowess, while Sahadeva is depicted as patient, wise, intelligent and a “learned man”. Nakula takes great interest in Virata’s horses, and his brother Sahadeva become Virata’s cowherd. Scholarship also points out that the Vedic Ashvins had an Avestic counterpart called Aspinas. The pair of heroic brothers and main characters of the Albanian legendary epic cycle Kângë Kreshnikësh – Muji and Halili – are considered to bear common traits of the Indo-European divine twins.” ref

“The Armenian heroes Sanasar and Baldasar appear as twins in the epic tradition, born of princess Tsovinar (as depicted in Daredevils of Sassoun); Sanasar finds a “fiery horse”, is more warlike than his brother, and becomes the progenitor of a dynasty of heroes. In an alternate account, their mother is named princess Saṙan, who drinks water from a horse’s footprint and gives birth to both heroes. Scholar Armen Petrosyan also sees possible reflexes of the divine twins in other pairs of heroic brothers in Armenian epic tradition, e.g., Ar(a)maneak and Ar(a)mayis; Eruand (Yervant) and Eruaz (Yervaz). In the same vein, Sargis Haroutyunian argues that the Armenian heroes, as well as twins Izzadin (or Izaddin) and Zyaddin (mentioned in the Kurdish Sharafnama), underlie the myth of divine twins: pairs of brother-founders of divine origin.” ref

“The mytheme of the Divine Twins was widely popular in the Indo-European traditions; evidence for their worship can be found from Scandinavia to the Near East as early as the Bronze Age. The motif was also adopted in non-Indo-European cultures, as attested by the Etruscan Tinas Clenar, the “sons of Jupiter”. There might also have been a worship of twin deities in Myceanean times, based on the presence of myths and stories about pairs of brothers or male twins in Attica and Boeotia. The most prevalent functions associated with the twins in later myths are magic healers and physicians, sailors and saviours at sea, warriors and providers of divine aid in battle, controllers of weather and keepers of the wind, assistants at birth with a connection to fertility, divinities of dance, protectors of the oath, and founders of cities, sometimes related to swans. Scholarship suggests that the mytheme of twins has echoes in the medieval legend of Amicus and Amelius. In Belarusian folklore, Saints George and Nicholas are paired up together, associated with horses, and have a dual nature as healers. The veneration of the Slavic saint brothers Boris and Gleb may also be related.” ref

“Lugal-irra (𒀭𒈗𒄊𒊏) and Meslamta-ea (𒀭𒈩𒇴𒋫𒌓𒁺𒀀) were a pair of Mesopotamian gods who typically appear together in cuneiform texts and were described as the “divine twins” (Maštabba). There were regarded as warrior gods and as protectors of doors, possibly due to their role as the gatekeepers of the underworld. In Mesopotamian astronomy they came to be associated with a pair of stars known as the “Great Twins”, Alpha Geminorum and Beta Geminorum. They were both closely associated with Nergal, and could be either regarded as members of his court or equated with him. Their cult centers were Kisiga and Dūrum. While no major sanctuaries dedicated to them are attested elsewhere, they were nonetheless worshiped in multiple other cities. Lugal-irra’s name was most commonly written in cuneiform as dLugal–GÌR-ra. It can be romanized as Lugalirra as well. It has Sumerian origin and can be translated as “the strong lord”. The variant Lugal-girra, dLugal-gír-ra, reflects a late reinterpretation of the name as “lord of the dagger” and is no longer considered an indication that dLugal-GÌR-ra was ever read as Lugal-girra. Despite the phonetic similarity, the second half of Lugal-irra’s name is most likely unrelated to the theonym Erra (variant: Irra), and its Akkadian translation was gašru according to lexical lists.” ref

“Twin deities manifested integrating or opposite natural elements in ancient Egypt. Two identical falcons represented Horus and Seth. Isis and Nephtys were also a divine twin of the same gender. Shu and Tefnut were an example for unlike-sexed divine twins. The souls of Osiris and Re were the twin children of Horus. This research studies the Egyptian divine twins beside the Greek twin deities which appeared in Egypt on a limited scale. Some of them had an Egyptian origin such as; the sign of Gemini which was inspired from Shu and Tefnut. Apollo and Artemis were also venerated in Egypt.” ref

“Twins in mythology are in many cultures around the world. In some cultures they are seen as ominous, and in others they are seen as auspicious. Twins in mythology are often cast as two halves of the same whole, sharing a bond deeper than that of ordinary siblings, or seen as fierce rivals. They can be seen as representations of a dualistic worldview. They can represent another aspect of the self, a doppelgänger, or a shadow.” ref

“Twins are often depicted with special powers. This applies to both mortal and immortal sets of twins, and often is related to power over the weather. Twins in mythology also often share deep bonds. In Greek mythology, Castor and Pollux share a bond so strong that when mortal Castor dies, Pollux gives up half of his immortality to be with his brother. Castor and Pollux are the Dioscuri twin brothers. Their mother is Leda, a being who was seduced by Zeus who had taken the form of a swan. Even though the brothers are twins, they have two different fathers. This phenomenon is a very common interpretation of twin births across different mythological cultures. Castor’s father is Tyndareus, the king of Sparta (hence the mortal form). Pollux is the son of Zeus (demigod).” ref

“This brothers were said to be born from an egg along with either sister Helen and Clytemnestra. This etymologically explains why their constellation, the Dioskouroi or Gemini, is only seen during one half of the year, as the twins split their time between the underworld and Mount Olympus. In an aboriginal tale, the same constellation represents the twin lizards who created the plants and animals and saved women from evil spirits. Another example of this strong bond shared between twins is the Ibeji twins from African mythology. Ibeji twins are viewed as one soul shared between two bodies. If one of the twins dies, the parents then create a doll that portrays the body of the deceased child, so the soul of the deceased can remain intact for the living twin.” ref

“Without the creation of the doll, the living twin is almost destined for death because it is believed to be missing half of its soul. Twins in mythology are often associated with healing. They are also often gifted with the ability of divination or insight into the future. Divine twins in twin mythology are identical to either one or both place of a god. The Feri gods are not separated entities but are unified into one center. These divine twins can function alone in one body, either functioning as a male or as male and female as they desire. Divine twins represent a polarity in the world. This polarity may be great or small and at times can be opposition. Twins are often seen to be rivals or adversaries.” ref

Africa

Egyptian

- Nut and Geb, Dualistic twins. God of Earth (Geb) and Goddess of the sky (Nut)

- Osiris – Isis’ twin and husband. Lord of the underworld. First born of Geb and Nut. One of the most important gods of ancient Egypt.

- Isis – Daughter of Geb and Nut; twin of Osiris.

- Ausar – (also known by Macedonian Greeks as Osiris) twin of Set. Set tricked his brother at a banquet he organized so as to take his life.

West African

- Mawu-Lisa – Twins representing moon and sun, respectively. Ewe-Fon culture.

- Yemaja – Mother of all life on earth. Yoruba culture.

- Aganju – Twin and husband of Yemaja

- Ibeji – Twins of joy and happiness. Children of Shango and Oshun.

Amerindian

See also: Hero Twins in Native American culture

- Gluskap and Malsumis – A cultural hero and its evil twin brother for the Wabanaki peoples.

- Hahgwehdiyu and Hahgwehdaetgah – Sons of either Iroquois sky goddess Atahensic or her daughter Tekawerahkwa.

- Asdzą́ą́ Nádleehé and Yolkai Estsan – Navajo goddesses.

- Monster Slayer and Born-for-Water – Navajo Hero Twins.

- Jukihú and Juracán – Twin sons of Atabex (Mother Nature), the personifications of Order and Chaos, respectively; from the Taíno Arawak nation which once stretched from South America through the Caribbean and up to Florida in the US.

- Hun-apu and Ixbalanque, the Maya Hero Twins – Defeated the Seven Macaw

- Quetzalcoatl and Xolotl or Tezcatlipoca

- Kokomaht and Bahotahl – Good and evil forces in nature.

Ancient Mesopotamian religion

Greek and Roman mythology

- Divine

- Helios and Selene – God and Goddess, children of Hyperion and Theia

- Apollo and Artemis – God and goddess, children of Zeus and Leto

- Hypnos and Thanatos – Sons of Nyx

- Despoina and Arion – Goddess and immortal horse, children of Demeter and Poseidon.

- Palici – Sicilian chthonic deities in Greek mythology and Roman mythology.

- Phobos and Deimos – Sons of Ares and Aphrodite

- Eros and Anteros – Sons of Ares and Aphrodite

- One divine, one mortal

- Heracles and Iphicles – Though their mother was Alcmene, Hercules was son of Zeus while Iphicles was son of Amphitryon.

- Castor and Pollux, known as the Dioscuri – Though their mother was Leda, Castor was mortal son of Tyndareus, the king of Sparta, while Pollux was the divine son of Zeus.

- Helen and Clytemnestra – Sisters of the Dioscuri, they were the daughters of Leda by Zeus and Tyndareus, respectively.

- Children of a god or nymph and a mortal

- Atlas and Eumelus/Gadeirus, Ampheres and Evaemon, Mneseus and Autochthon, Elasippus and Mestor, and Azaes and Diaprepes – Five sets of twins, sons of Poseidon and Cleito, and Kings of Atlantis in Plato‘s myth.

- Belus and Agenor – Sons of Poseidon and Libya.

- Aegyptus and Danaus – Sons of Belus and Achiroe, a naiad daughter of Nile.

- Aeolus and Boeotus – Sons of Poseidon and Arne.

- Lycastus and Parrhasius – Sons of Ares and Phylonome, daughter of Nyctimus of Arcadia.

- Amphion and Zethus – Sons of Zeus by Antiope

- Centaurus and Lapithes – Sons of Ixion and Nephele or Apollo and Stilbe.

- Pelias and Neleus – Sons of Poseidon and Tyro.

- Romulus and Remus – Central characters of Rome’s foundation myth. Children of Rhea Silvia by either the god Mars, or by the demi-god Hercules.

- Eurytus and Cteatus – Sons of Molione either by Actor or Poseidon

- Ascalaphus and Ialmenus – Sons of Ares and Astyoche, Argonauts who participated in the Trojan War.

- Mortal

- Kleobis and Biton – Sons of a Hera priestess in Argos

- Iasus and Pelasgus – Sons of Phoroneus or Triopas

- Proetus and Acrisius – Rival twins, children of Abas and Aglaea or Ocalea.

- Porphyrion and Ptous – Sons of Athamas and Themisto

- Thessalus and Alcimenes – Sons of Jason and Medea.

- Cassandra and Helenus – Children of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy with prophetic powers.

- Procles and Eurysthenes – Great-great-great-grandsons of Heracles, sons of Aristodemus and Argia.

- Sisyphus and Salmoneus – Rivals who angered Zeus with their deceit and hubris. Sons of King Aeolus of Thessaly and Enarete.

Ancient Syria

Norse mythology

- Freyr and Freyja – God and goddess, children of Njörðr

- Baldr and Hodr – “The Shining One” and “The Blind God”, Children of Odin and Frigg

- Móði and Magni – Courage/Bravery and Strength. Although not Twins in every Source, they often come in a pair. In some iterations, Twin sons of Thor and Sif.

Hinduism

- The Ashvins – Sons of the sun God, Surya. Represent dualities such as building and destroying.

- Koti and Chennayya – Twin heroes

- Yama and Yami – God and Goddess of death.

- Lava and Kusha – Children of Rama and Sita.

- Nakula and Sahadeva – sons of the last born of the Pandavas

- Lakshmana and Shatrughna – Children of Dasharatha and Sumitra

- Indra and Agni – Mirror twins

- Nala and Nila Ramayan

Jewish

- Jacob and Esau – Sons of Isaac and Rebekah. Represented two nations.

Christian

Thomas the apostle and his unnamed twin brother.

Zoroastrian

- Ahura Mazda and Ahriman – Twins of opposing forces: good and evil.

Ossetian mythology

Afro-Caribbean cosmologies

- Marassa Jumeaux – The divine, children twins in Vodou.

- Ibeji – Twins of joy and happiness. Children of Shango or Sango and Oshun.

East Asian

- Izanagi and Izanami – God and Goddess, creators of the Japanese islands.

Cain and Abel, the First Human Brothers in the Bible

“In the biblical Book of Genesis, Cain and Abel are the first two sons of Adam and Eve. Cain, the firstborn, was a farmer, and his brother Abel was a shepherd. The brothers made sacrifices, each from his own fields, to God. God had regard for Abel’s offering, but had no regardfor Cain’s. Cain killed Abel, and God cursed Cain, sentencing him to a life of transience. Cain then dwelt in the land of Nod (נוֹד, ‘wandering’), where he built a city and fathered the line of descendants beginning with Enoch.” ref

“The story of Cain‘s murder of Abel and its consequences is told in Genesis 4:1–18:

Now the man knew his wife Eve, and she conceived and bore Cain, saying, “I have produced a man with the help of the Lord.” Next she bore his brother Abel. Now Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a tiller of the ground. In the course of time Cain brought to the Lord an offering of the fruit of the ground, and Abel for his part brought of the firstlings of his flock, their fat portions. And the Lord had regard for Abel and his offering, but for Cain and his offering he had no regard. So Cain was very angry, and his countenance fell. The Lord said to Cain,

“Why are you angry,

and why has your countenance fallen?

If you do well,

will you not be accepted?

And if you do not do well,

sin is lurking at the door;

its desire is for you,

but you must master it.”

Cain said to his brother Abel, “Let us go out to the field.” And when they were in the field, Cain rose up against his brother Abel, and killed him.

Then the Lord said to Cain, “Where is your brother Abel?” He said, “I do not know; am I my brother’s keeper?” And the Lord said, “What have you done? Listen; your brother’s blood is crying out to me from the ground! And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. When you till the ground, it will no longer yield to you its strength; you will be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth.” Cain said to the Lord, “My punishment is greater than I can bear! Today you have driven me away from the soil, and I shall be hidden from your face; I shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth, and anyone who meets me may kill me.” Then the Lord said to him, “Not so! Whoever kills Cain will suffer a sevenfold vengeance.” And the Lord put a mark on Cain, so that no one who came upon him would kill him. Then Cain went away from the presence of the Lord, and settled in the land of Nod, east of Eden. Cain knew his wife, and she conceived and bore Enoch; and he built a city, and named it Enoch after his son Enoch.” — Book of Genesis, 4:1–18