Du-Ku

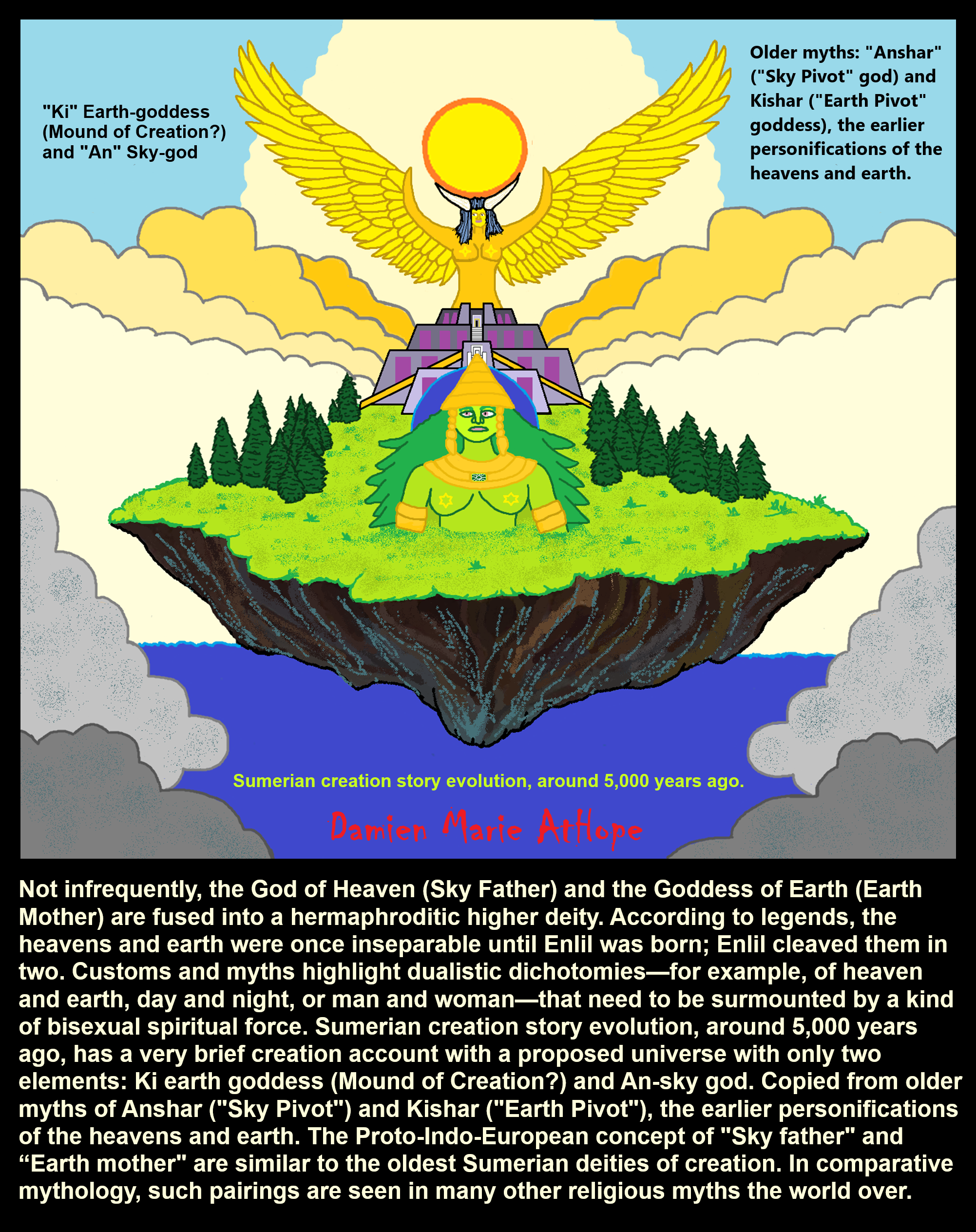

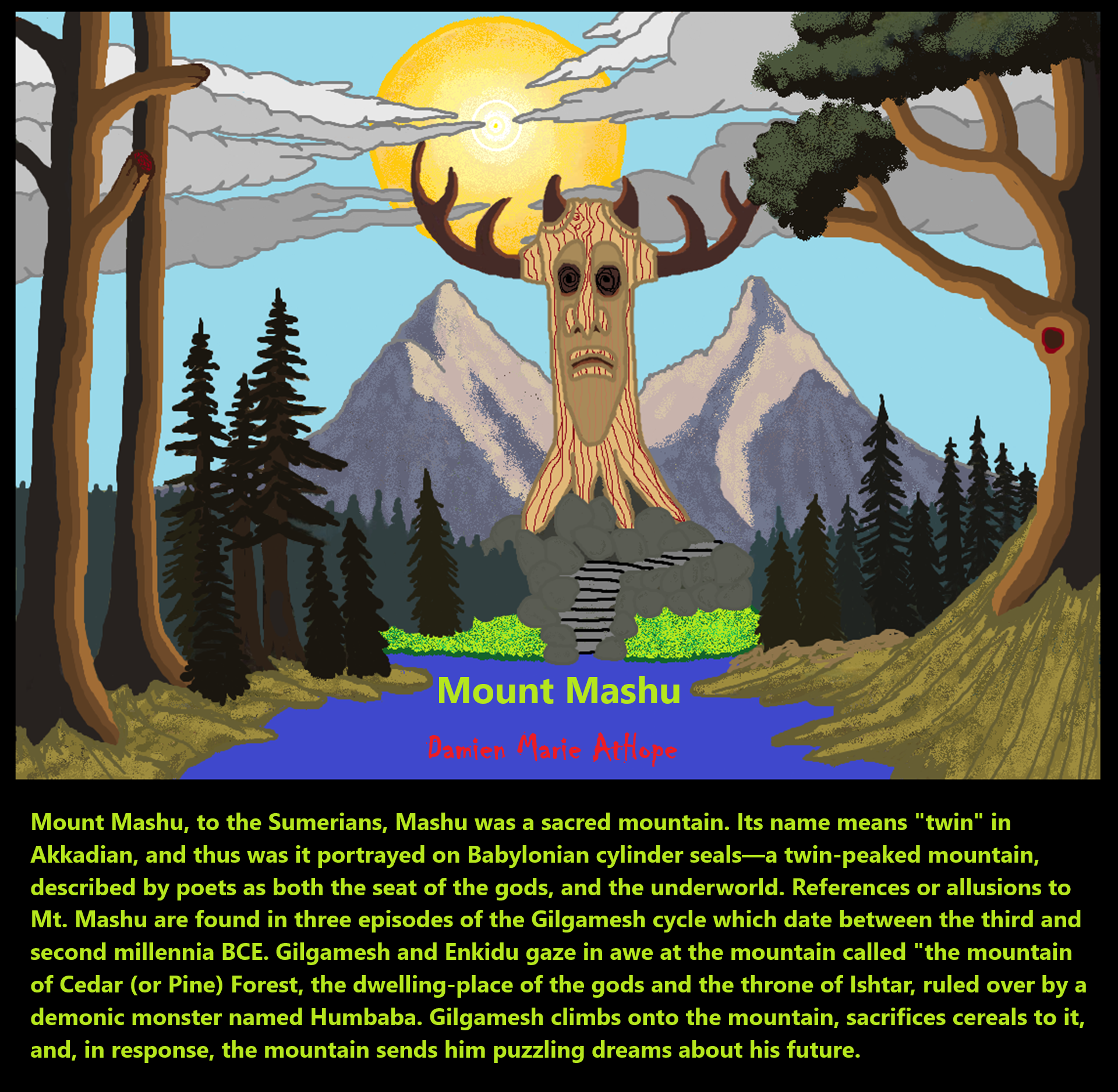

“Du-Ku or dul-kug is a Sumerian word for a sacred place. According to Wasilewska et al., du-ku translates as “holy hill”, “holy mound” […E-dul-kug… (House which is the holy mound), or “great mountain. According to the University of Pennsylvania online dictionary of Sumerian and Akkadian languages, du-ku is actually du6-ku3, with du6 being defined as a mound or ruin mound, and ku3 as either ritually pure or shining: it is used in the texts on the Univ. of Oxford site as “shining”. There is no mention of nor association with the term “holy”, and instead it represents a cultic and cosmic place. The location is otherwise alluded to in sacred texts as a specifically identified place of godly judgement. The hill was the location for ritual offerings to Sumerian god(s) Nungal and the Anunna dwell upon the holy hill in a text written from Gilgamesh.” ref

Sumerian tablet of Ereshkigal

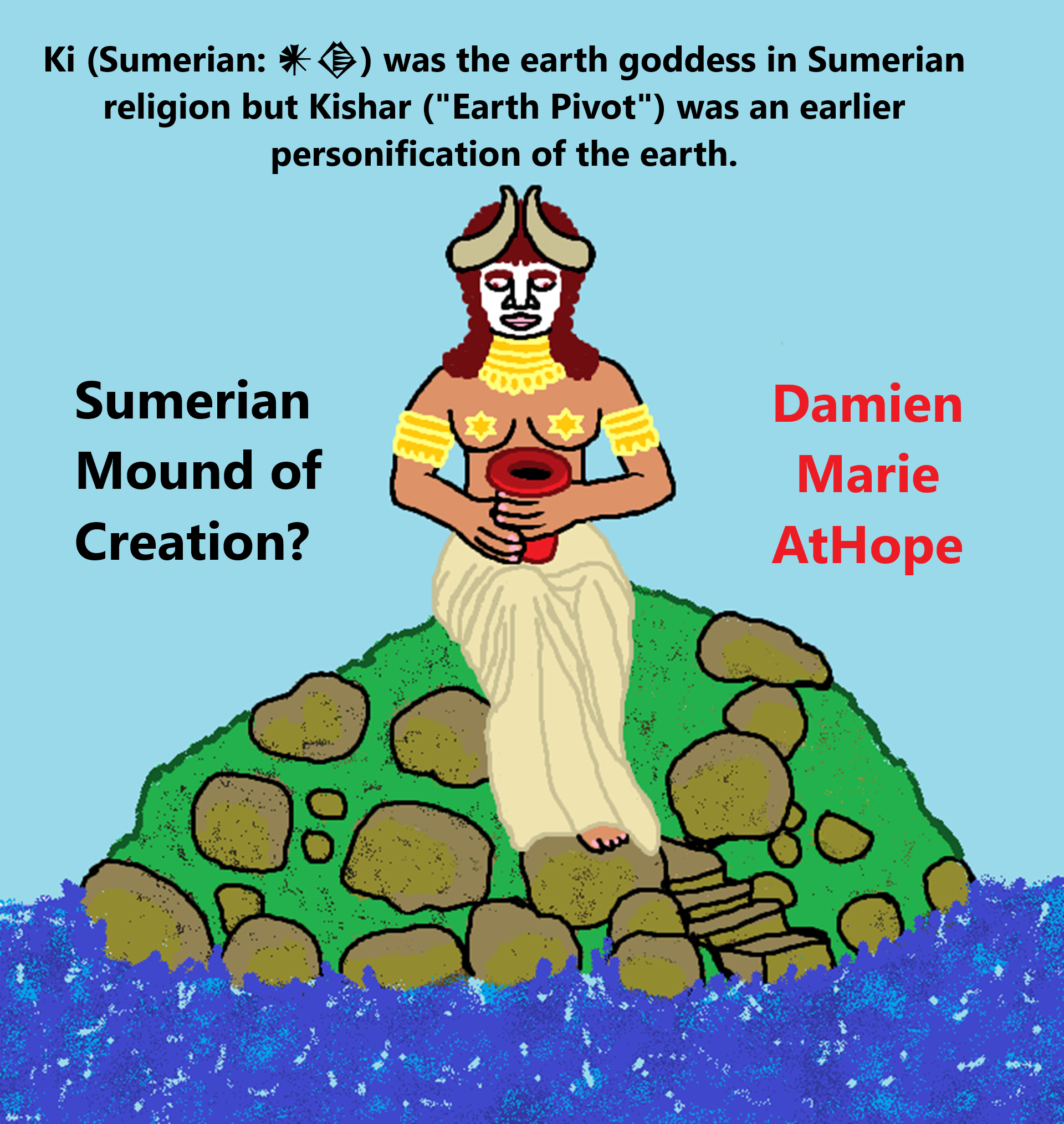

“… Enlil on the shore, where he kept watch over the “Du-Ku, the Holy Mound of Creation,” and Mother Ki, (sometimes Antu, sometimes Ninhursag) his eyes gleaming with fond laughter. But why did they leave the safety of the Duku, the mound of creation, why did they go beyond the Waters of Mother Nammu.” ref

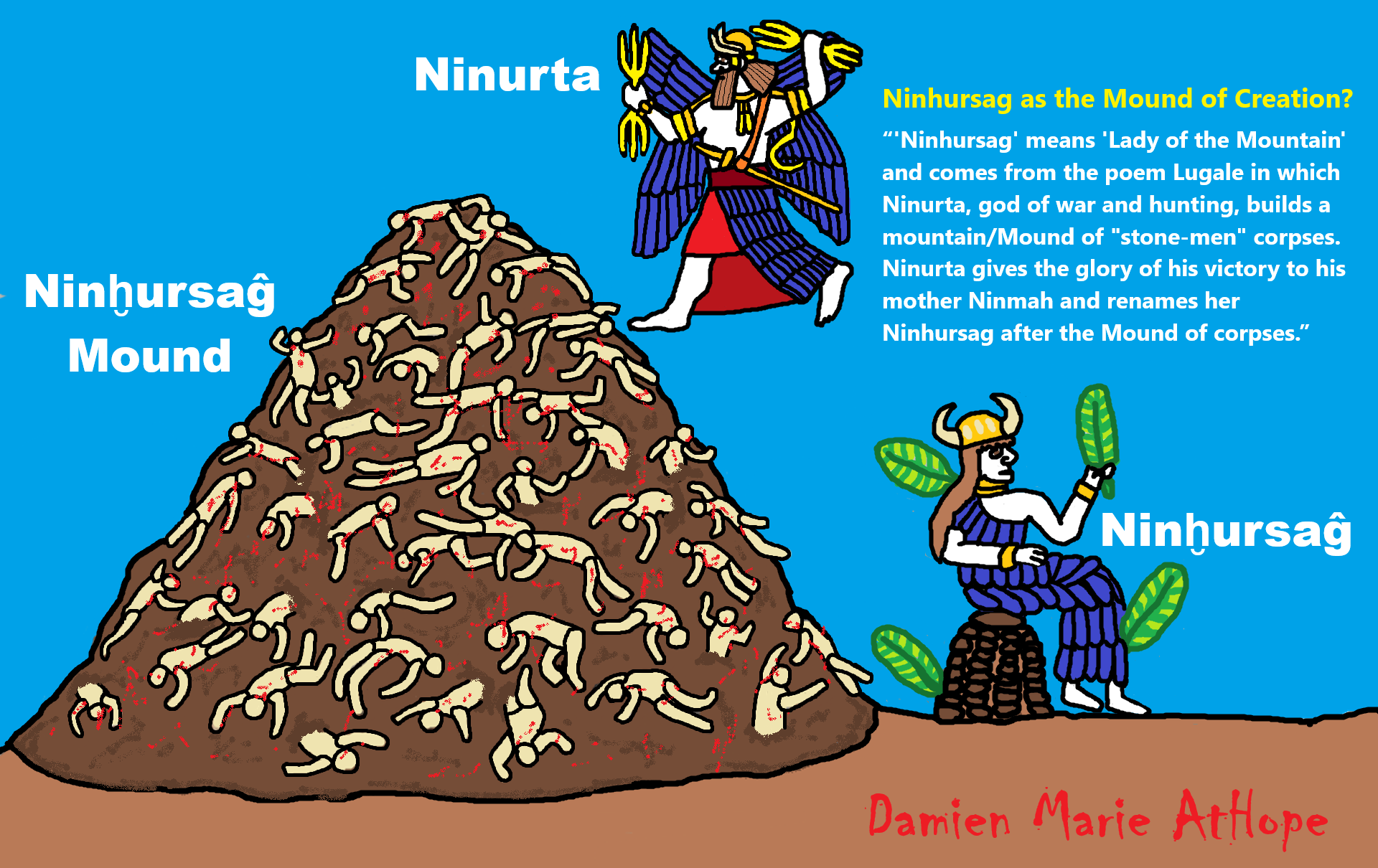

“Ninhursag (also Ninhursaga) is the Sumerian Mother Goddess and one of the oldest and most important in the Mesopotamian Pantheon. She replaced the earlier Mother Goddess, Nammu (also known as Namma) whose worship is attested as early as Dynastic III (2600-2334 BCE) of the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE).” ref

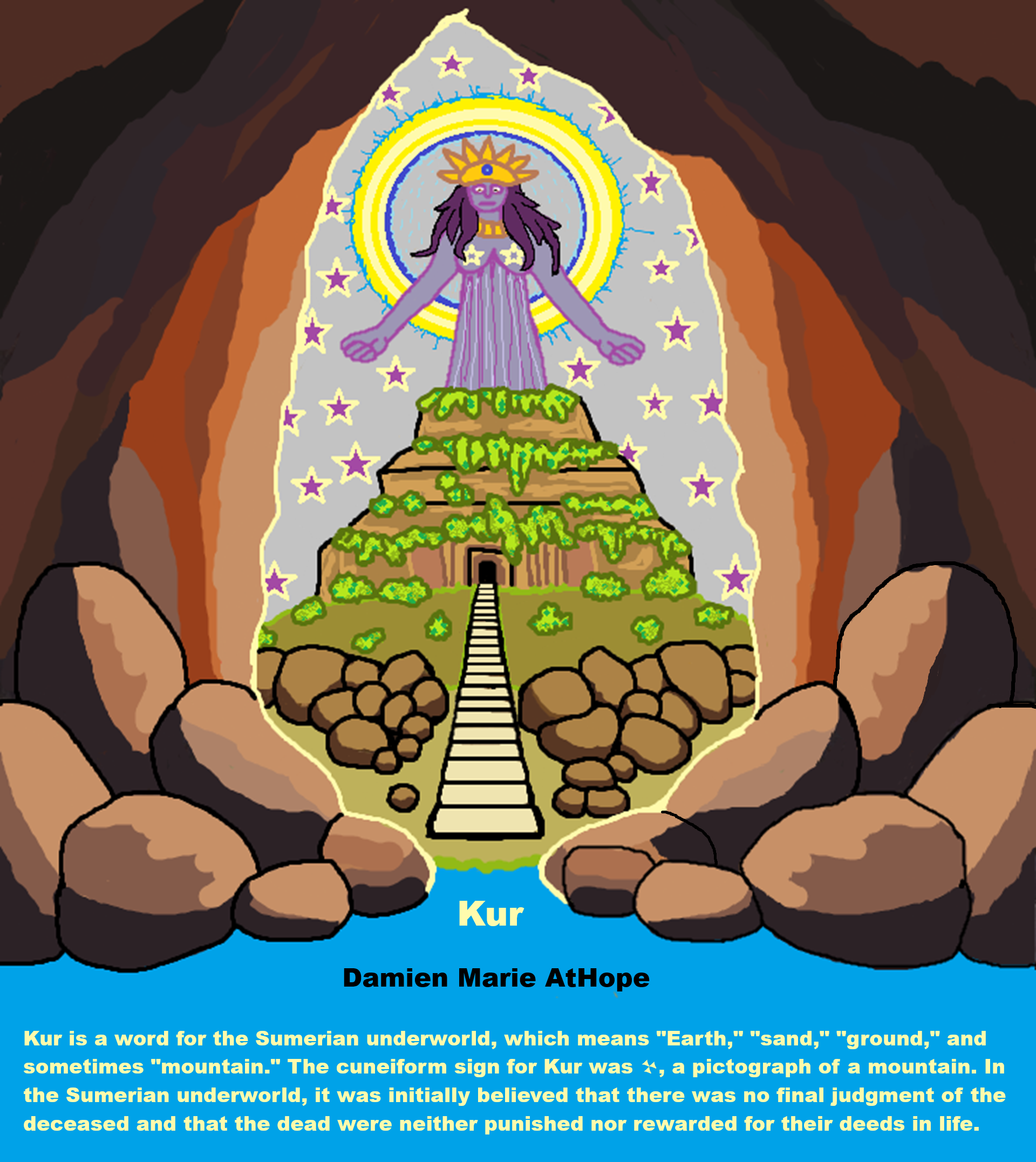

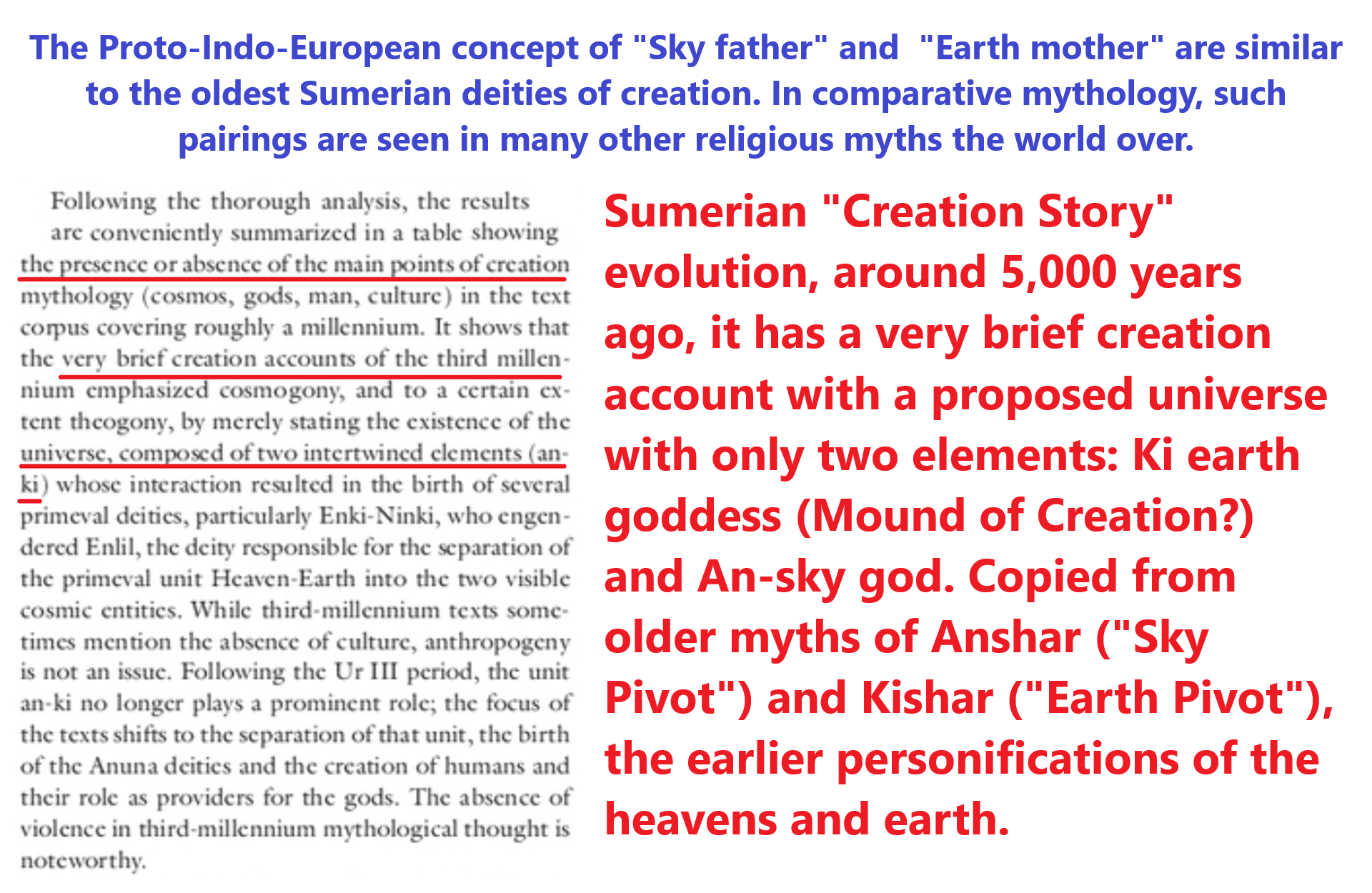

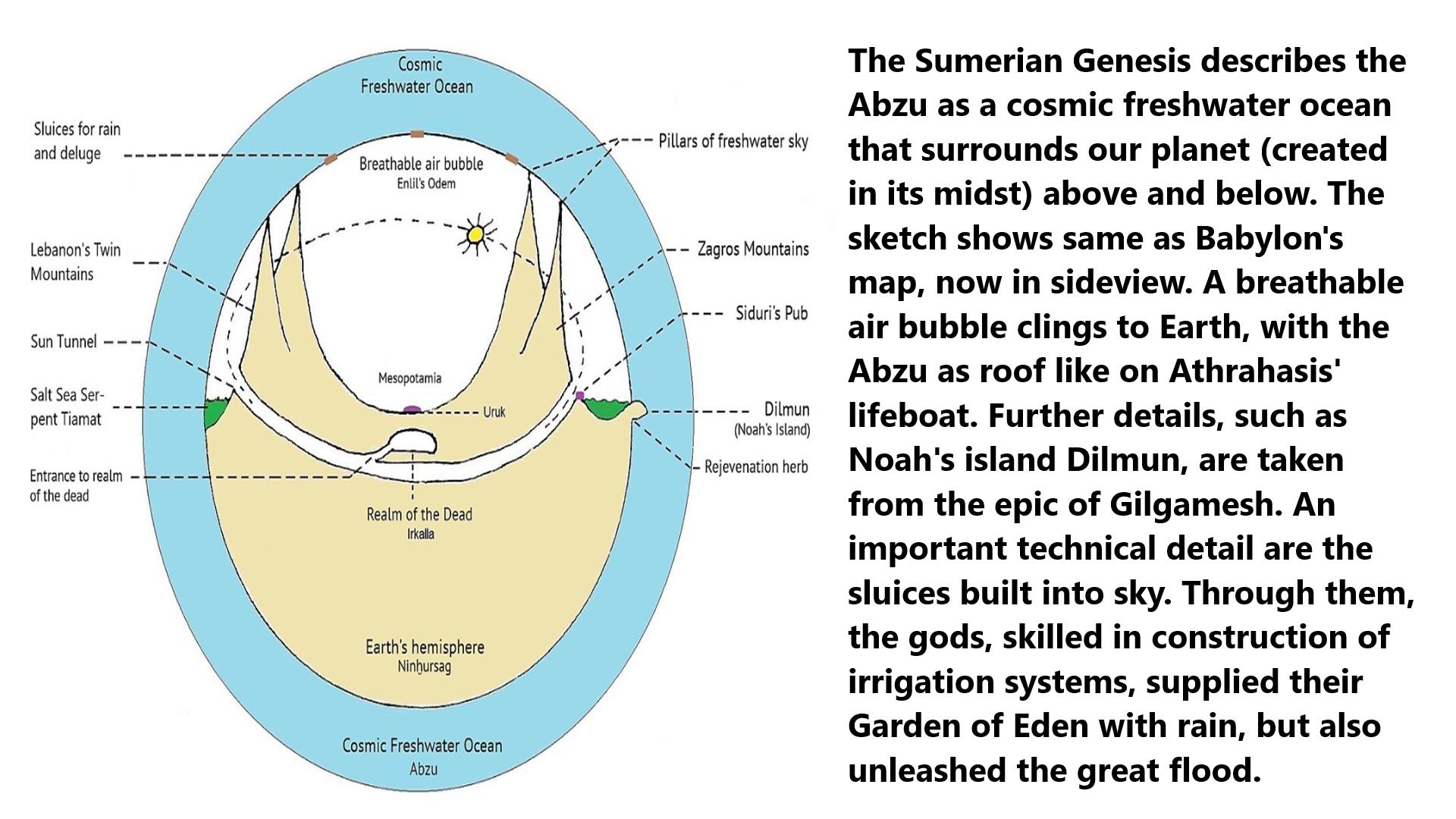

“Nammu was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as a creator deity, especially in the early Sumerian city, Eridu. Mother of An (Heaven/Sky god) and Ki (Earth/Mound of Creation?), as well as a primeval sea/Cosmic ocean, related to the goddess Tiamat.” ref

“Nammu (𒀭𒇉 dENGUR = dLAGAB×ḪAL; also read Namma) was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as a creator deity in the local theology of Eridu. It is assumed that she was associated with water. She is also well-attested in connection with incantations and apotropaic magic. She was regarded as the mother of Enki, and in a single inscription she appears as the wife of Anu, but it is assumed that she usually was not believed to have a spouse. From the Old Babylonian period onwards, she was considered to be the mother of An (Heaven) and Ki (Earth), as well as a representation of the primeval sea/ocean, an association that may have come from influence from the goddess Tiamat.” ref

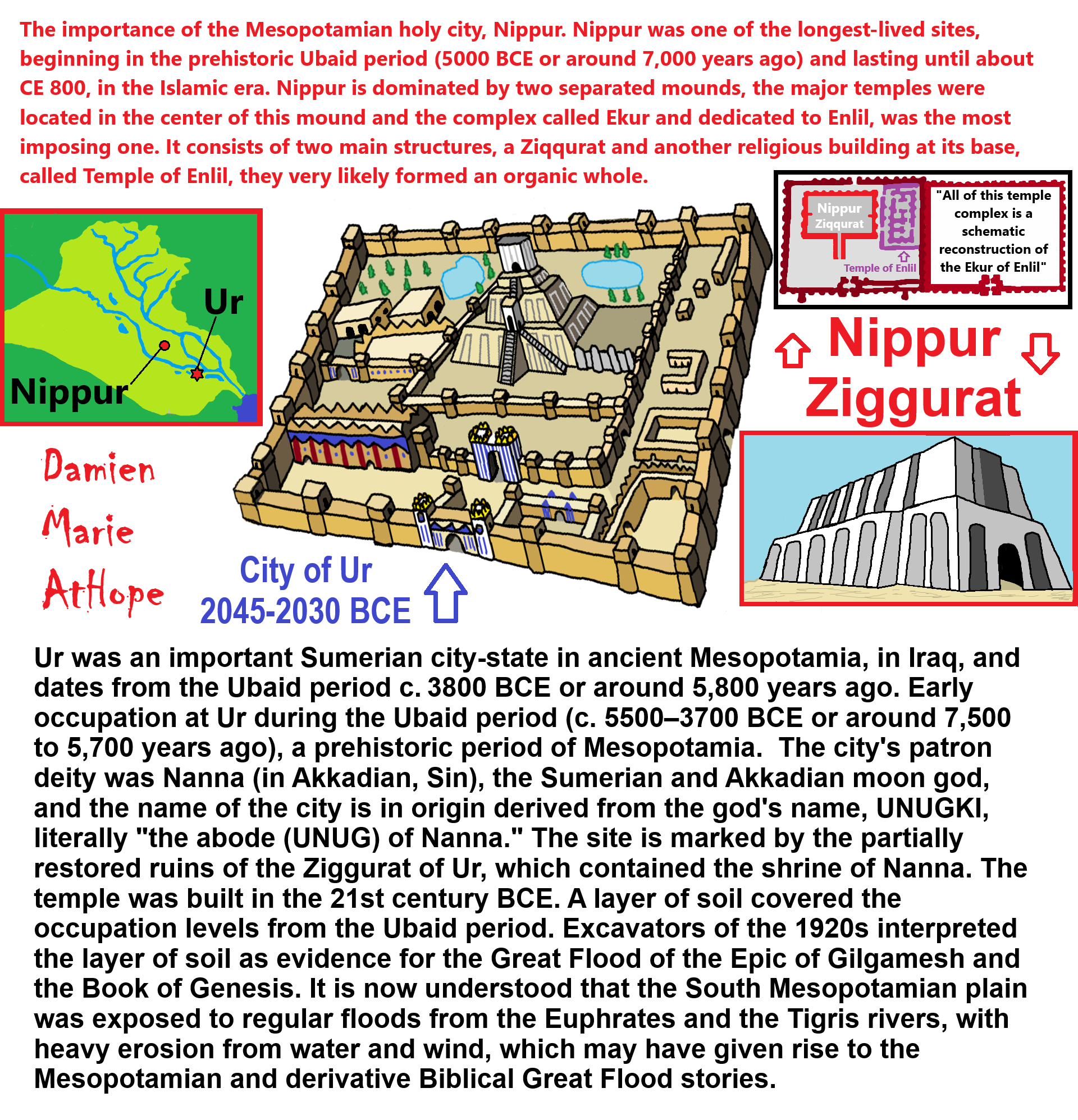

“While Nammu is already attested in sources from the Early Dynastic period, such as the zame hymns and an inscription of Lugal-kisalsi, she was not commonly worshiped. A temple dedicated to her existed in Ur in the Old Babylonian period, she is also attested in texts from Nippur and Babylon. Theophoric names invoking her were rare, with that of king Ur-Nammu until recently being believed to be the only example. In the Old Babylonian myth Enki and Ninmah, Nammu is one of the deities involved in the creation of mankind alongside the eponymous pair and a group of seven minor goddesses. Her presence differentiates this narrative from other texts dealing with the same motif, such as Atra-Hasis.” ref

“Nammu’s name was represented in cuneiform by the Sumerogram ENGUR (LAGAB×ḪAL). Lexical lists provide evidence for multiple readings, including Nammu, Namma, and longer, reduplicated variants such as Namnamu and Nannama. A bilingual text from Tell Harmal treats the short and long forms of the name as if they were respectively the Akkadian and Sumerian versions of the same word. The name is conventionally translated as “creatrix.” ref

‘This interpretation depends on the theory that it is etymologically related to the element imma (SIG7) in the name of the goddess Ninimma, which could be explained in Akkadian as nabnītu or bunnannû, two terms pertaining to creation. However, this proposal is not universally accepted. Another related possibility is to interpret it as a genitive compound, (e)n + amma(k), “lady of the cosmic river,” but it is similarly not free of criticism, and it has been argued no clear evidence for the etymology for Nammu’s name exists. Ancient authors secondarily etymologized it as nig2-nam-ma, “creativity,” “totality,” or “everything.” ref

“The sign ENGUR could also be read as engur, a synonym of apsu, but when used in this context, it was not identical with the name of the goddess, and Nammu could be referred to as the creator of engur, which according to Frans Wiggermann confirms she and the mythical body of water were not identical. Nammu could be referred to with epithets such as “lady who is great and high in the sea” (nin-ab-gal-an-na-u5-a),” mother who gave birth to heaven and earth” (dama-tu-an-ki) or “first mother who gave birth to all (or senior) gods” (ama-palil-u3-tu-diĝir-šar-šar-ra-ke4-ne). The motherhood of Nammu to heaven and earth is attested in texts like the god-list TCL XV 10 and is related to the status attained from the Old Babylonian period onwards as the mother of An (Heaven) and Ki (Earth).” ref

“Few sources providing information about Nammu’s character are known. Most of them come from the Old Babylonian period. Based on indirect evidence, it is assumed she was associated with water, though there is debate among researchers over whether sweet or saline. No explicit references to Nammu being identical with the sea are known, and Manuel Ceccarelli in a recent study suggests she might have represented groundwater. Jan Lisman, who views Nammu as having been a representation of the primordial ocean/sea from which the rest of the cosmos emerged, believes that Nammu’s association with this body of water may have come from the influence of the goddess Tiamat.” ref

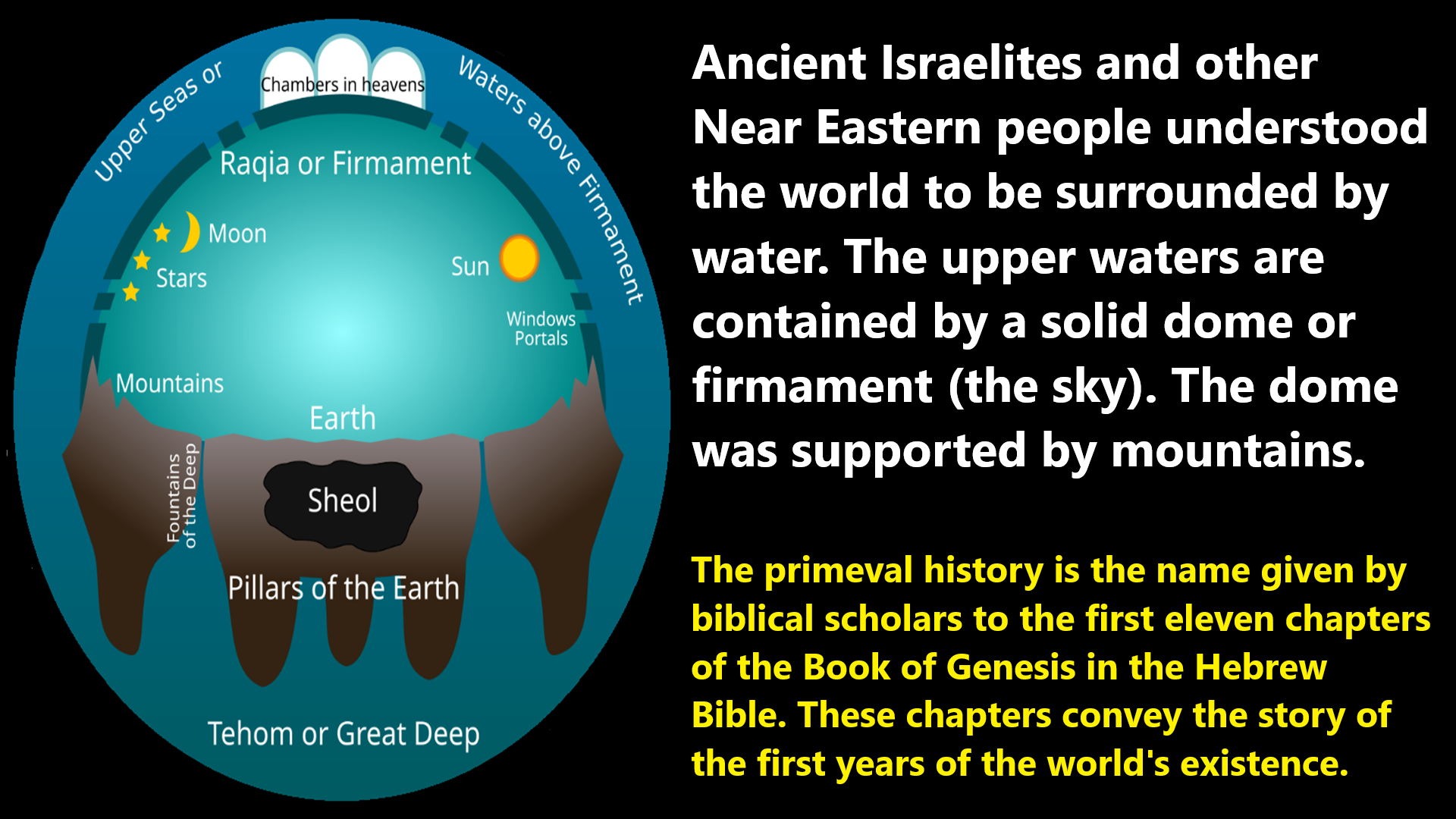

“In Mesopotamian religion, Tiamat (Akkadian: 𒀭𒋾𒊩𒆳 DTI.AMAT or 𒀭𒌓𒌈 DTAM.TUM, Ancient Greek: Θαλάττη, romanized: Thaláttē) is the primordial sea, mating with Abzû (Apsu), the groundwater, to produce the gods in the Babylonian epic Enûma Elish, which translates as “when on high.” She is referred to as a woman, and has—at various points in the epic—a number of anthropomorphic features (such as breasts) and theriomorphic features (such as a tail). In the Enûma Elish, the Babylonian epic of creation, Tiamat bears the first generation of deities after mingling her waters with those of Apsu, her consort. The gods continue to reproduce, forming a noisy new mass of divine children. Apsu, driven to violence by the noise they make, seeks to destroy them and is killed.” ref

“Enraged, Tiamat also wars upon those of her own and Apsu’s children who killed her consort, bringing forth a series of monsters as weapons. She also takes a new consort, Qingu, and bestows on him the Tablet of Destinies, which represents legitimate divine rulership. She is ultimately defeated and slain by Enki‘s son, the storm-god Marduk, but not before she conjures forth monsters whose bodies she fills with “poison instead of blood.” Marduk dismembers her, and then constructs and structures elements of the cosmos from Tiamat’s body. Some sources have dubiously identified her with images of a sea serpent or dragon. Tiamat also has been claimed to be cognate with the Northwest Semitic word tehom (תְּהוֹם; ‘the deeps, abyss’), in the Book of Genesis 1:2.” ref

“The Babylonian epic Enuma Elish is named for its incipit: “When on high [or: When above],” the heavens did not yet exist, nor the earth below, Abzu the subterranean ocean was there, “the first, the begetter,” and Tiamat, the overground sea, “she who bore them all”; they were “mixing their waters.” It is thought that female deities are older than male ones in Mesopotamia, and Tiamat may have begun as part of the cult of Nammu, a female principle of a watery creative force, with equally strong connections to the underworld, which predates the appearance of Ea-Enki. Harriet Crawford finds this “mixing of the waters” to be a natural feature of the middle Persian Gulf, where fresh waters from the Arabian aquifer mix and mingle with the salt waters of the sea.” ref

“This characteristic is especially true of the region of Bahrain, whose name in Arabic means “two seas”, and which is thought to be the site of Dilmun, the original site of the Sumerian creation beliefs. The difference in density of salt and fresh water drives a perceptible separation. In the Enuma Elish, Tiamat’s physical description includes a tail, a thigh, “lower parts” (which shake together), a belly, an udder, ribs, a neck, a head, a skull, eyes, nostrils, a mouth, and lips. She has insides (possibly “entrails”), a heart, arteries, and blood. Tiamat was once regarded as a sea serpent or dragon, although Assyriologist Alexander Heidel has previously recognized that a “dragon form can not be imputed to Tiamat with certainty.” She is still often referred to as a monster, though this identification has been credibly challenged. In Enuma Elish, Tiamat is clearly portrayed as a mother of monsters but, before this, she is just as clearly portrayed as a mother to all the gods.” ref

“With Tiamat, Abzu (or Apsû) fathered the elder deities Lahmu and Lahamu (masc. the ‘hairy’), a title given to the gatekeepers at Enki’s Abzu/E’engurra-temple in Eridu. Lahmu and Lahamu, in turn, were the parents of the ‘ends’ of the heavens (Anshar, from an-šar, ‘heaven-totality/end’) and the earth (Kishar); Anshar and Kishar were considered to meet at the horizon, becoming, thereby, the parents of Anu (Heaven) and Ki (Earth). Tiamat was the “shining” personification of the sea who roared and smote in the chaos of original creation. She and Abzu filled the cosmic abyss with the primeval waters. She is “Ummu-Hubur who formed all things.” ref

“In the myth recorded on cuneiform tablets, the deity Enki (later Ea) believed correctly that Abzu was planning to murder the younger deities as a consequence of his aggravation with the noisy tumult they created. This premonition led Enki to capture Abzu and hold him prisoner beneath Abzu’s own temple, the E-Abzu (‘temple of Abzu’). This angered Kingu, their son, who reported the event to Tiamat, whereupon she fashioned eleven monsters to battle the deities in order to avenge Abzu’s death. These were her own offspring: Bašmu (‘Venomous Snake’), Ušumgallu (‘Great Dragon’), Mušmaḫḫū (‘Exalted Serpent’), Mušḫuššu (‘Furious Snake’), Laḫmu (the ‘Hairy One’), Ugallu (the ‘Big Weather-Beast’), Uridimmu (‘Mad Lion’), Girtablullû (‘Scorpion-Man’), Umū dabrūtu (‘Violent Storms’), Kulullû (‘Fish-Man’), and Kusarikku (‘Bull-Man’).” ref

“Tiamat was in possession of the Tablet of Destinies, and in the primordial battle, she gave the relic to Kingu, the deity she had chosen as her lover and the leader of her host, and who was also one of her children. The terrified deities were rescued by Anu, who secured their promise to revere him as “king of the gods.” He fought Tiamat with the arrows of the winds, a net, a club, and an invincible spear. Anu was later replaced first by Enlil, and (in the late version that has survived after the First Dynasty of Babylon) then subsequently by Marduk, the son of Ea.” ref

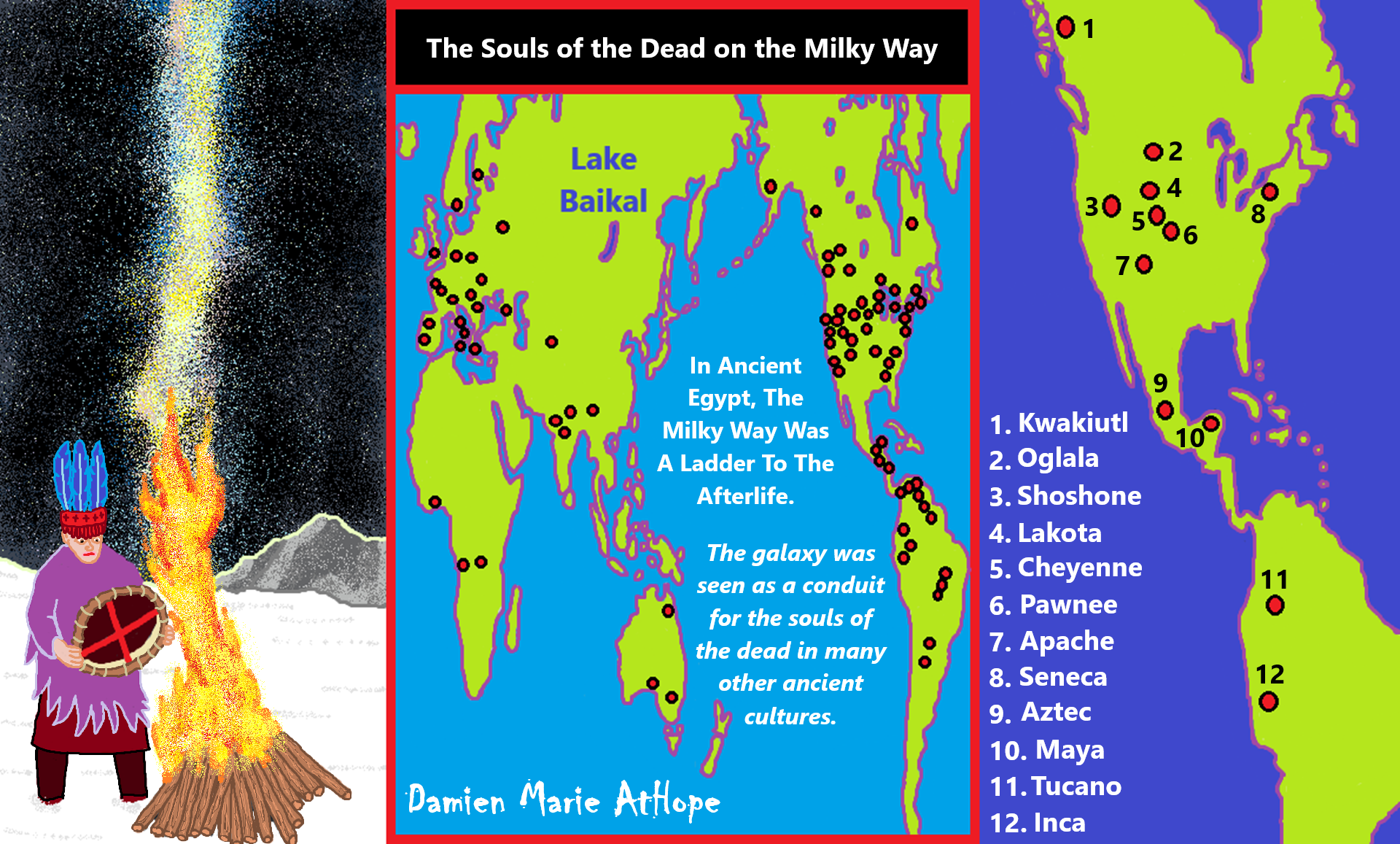

“Slicing Tiamat in half, Marduk made from her ribs the vault of heaven and earth. Her weeping eyes became the sources of the Tigris and the Euphrates, her tail became the Milky Way. With the approval of the elder deities, he took the Tablet of Destinies from Kingu, and installed himself as the head of the Babylonian pantheon. Kingu was captured and later was slain: his red blood mixed with the red clay of the Earth would make the body of humankind, created to act as the servant of the younger Igigi deities.” ref

“The principal theme of the epic is the rightful elevation of Marduk to command over all the deities. “It has long been realized that the Marduk epic, for all its local coloring and probable elaboration by the Babylonian theologians, reflects in substance older Sumerian material,” American Assyriologist E. A. Speiser remarked in 1942, adding, “The exact Sumerian prototype, however, has not turned up so far.” However, this surmise that the Babylonian version of the story is based upon a modified version of an older epic, in which Enlil, not Marduk, was the god who slew Tiamat, has been more recently dismissed as “distinctly improbable.” ref

“One example of an icon that was more so a motif of Tiamat was within the Temple of Bêl, located in Palmyra. The motif depicts Nabu and Marduk defeating Tiamat. In this picture, Tiamat is shown as a woman’s body with legs which are made of snakes. It was once thought that the myth of Tiamat was one of the earliest recorded versions of a Chaoskampf, a mythological motif that generally involves the battle between a culture hero and a chthonic or aquatic monster, serpent, or dragon. Chaoskampf motifs in other mythologies perhaps linked to the Tiamat myth include: the Hittite Illuyanka myth; the Greek lore of Apollo‘s killing of the Python as a necessary action to take over the Delphic Oracle; and to Genesis in the Hebrew Bible.” ref

“A number of writers have put forth ideas about Tiamat: Robert Graves, for example, considered Tiamat’s death by Marduk as evidence for his hypothesis of an ancient shift in power from a matriarchal society to a patriarchy. The theory suggested that Tiamat and other ancient monster figures were depictions of former supreme deities of peaceful, woman-centered religions. Their defeat at the hands of a male hero corresponded to the overthrow of these matristic religions and societies by male-dominated ones. Nu (mythology) – an ancient Egyptian deity with a similar role. Chaos (cosmogony) – Ancient Greek deity with a similar role. Ymir (Norse) is similar, as well as Pangu (Chinese), and Sea of Suf – a primordial sea in the World of Darkness in Mandaean cosmology.” ref

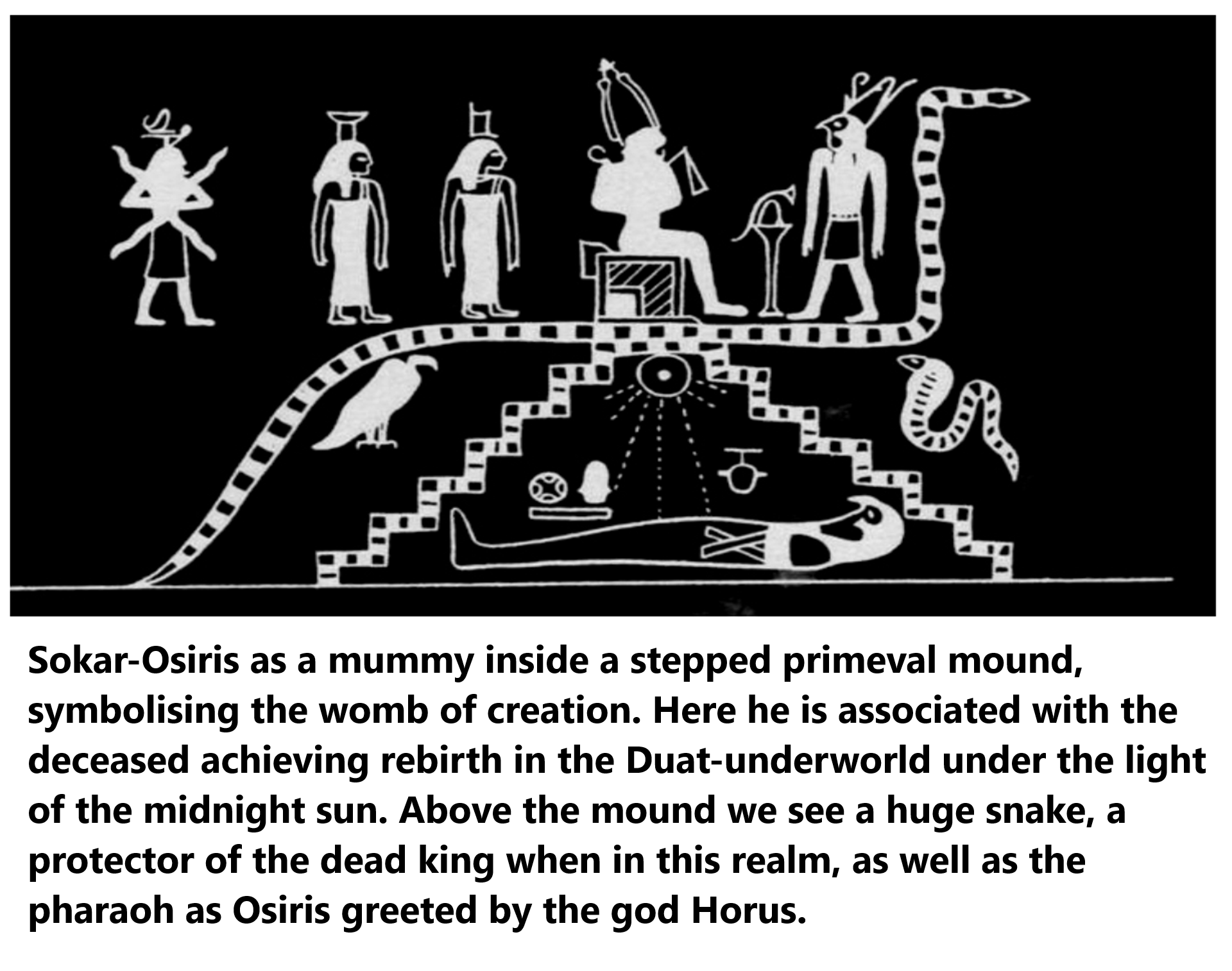

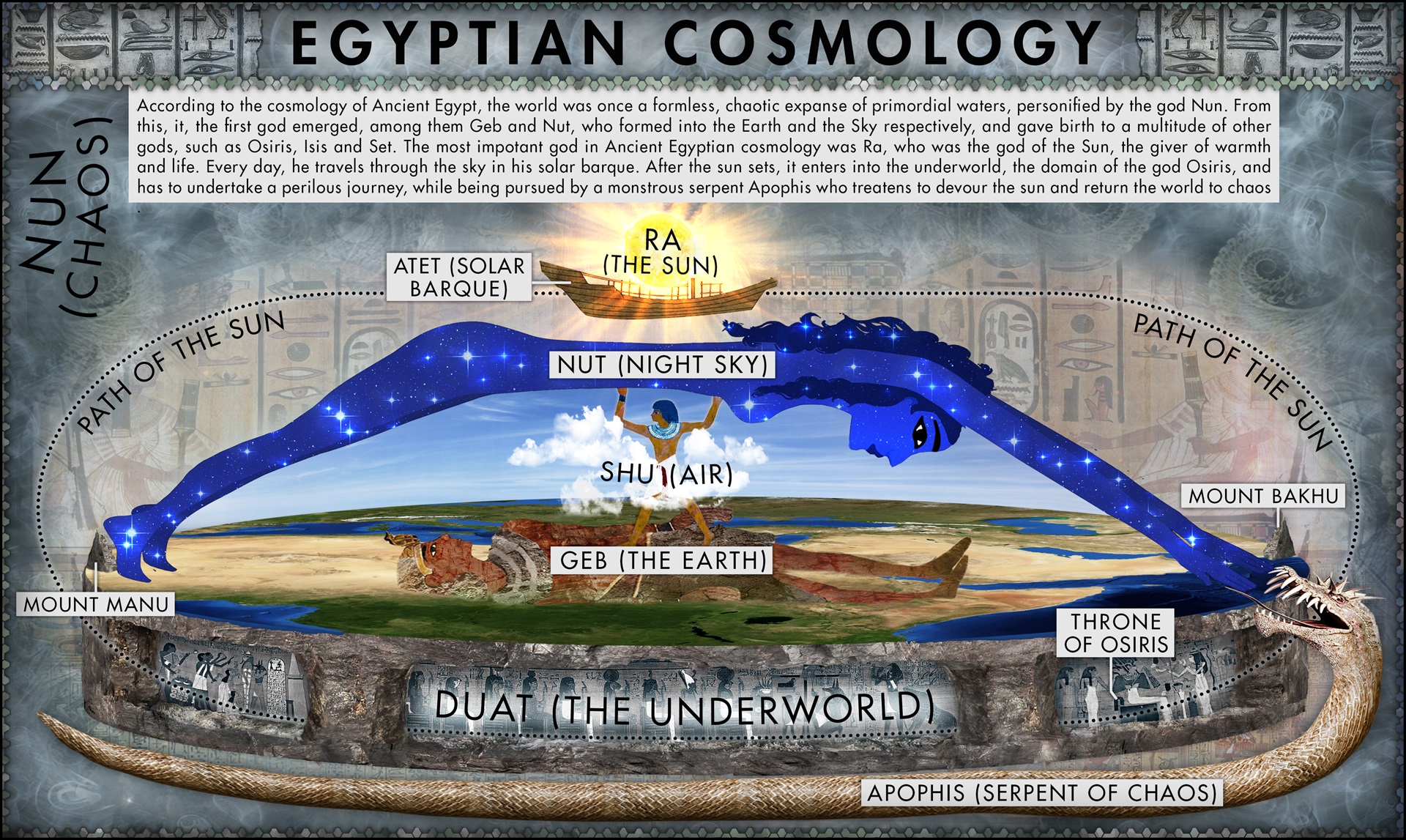

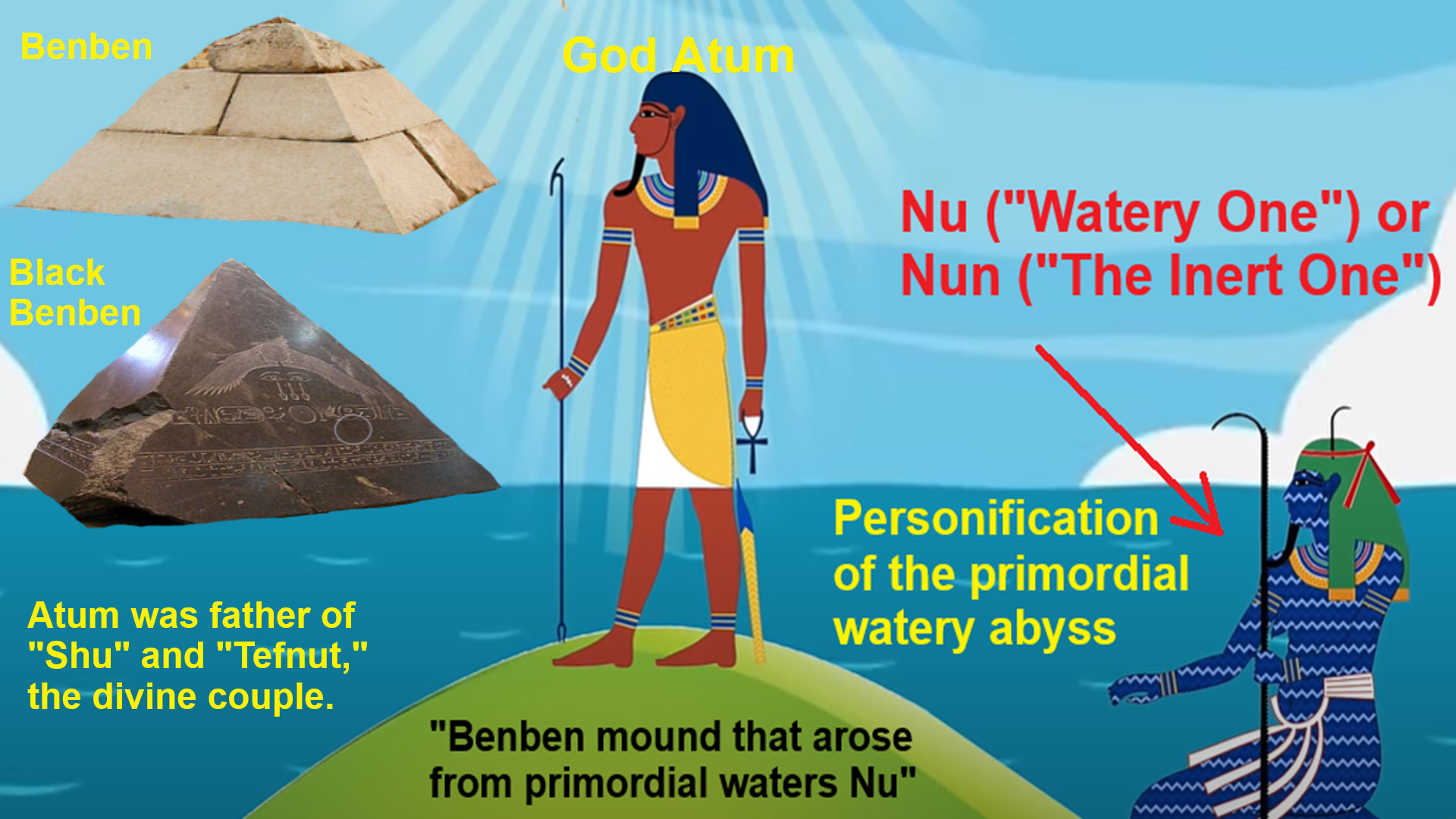

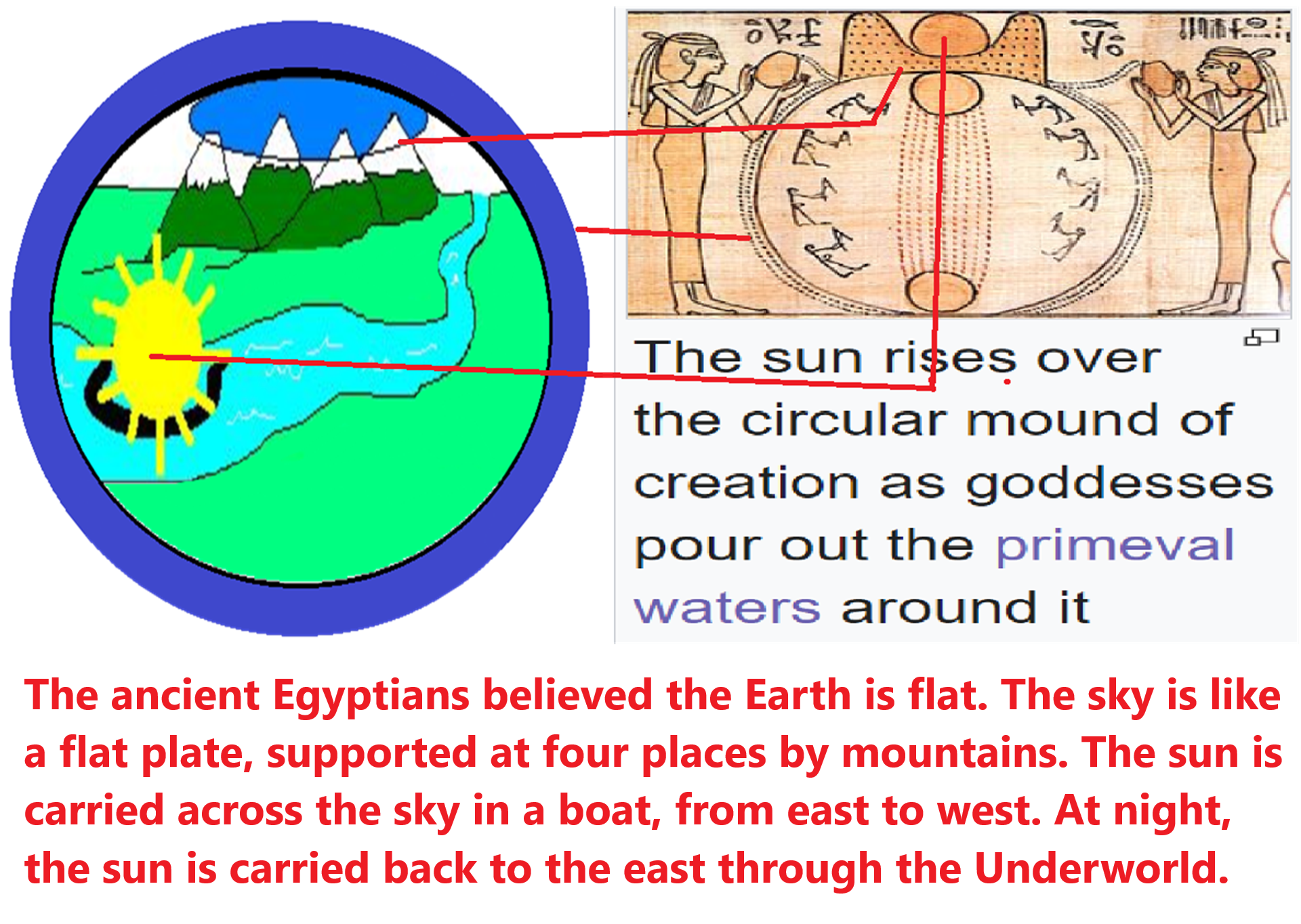

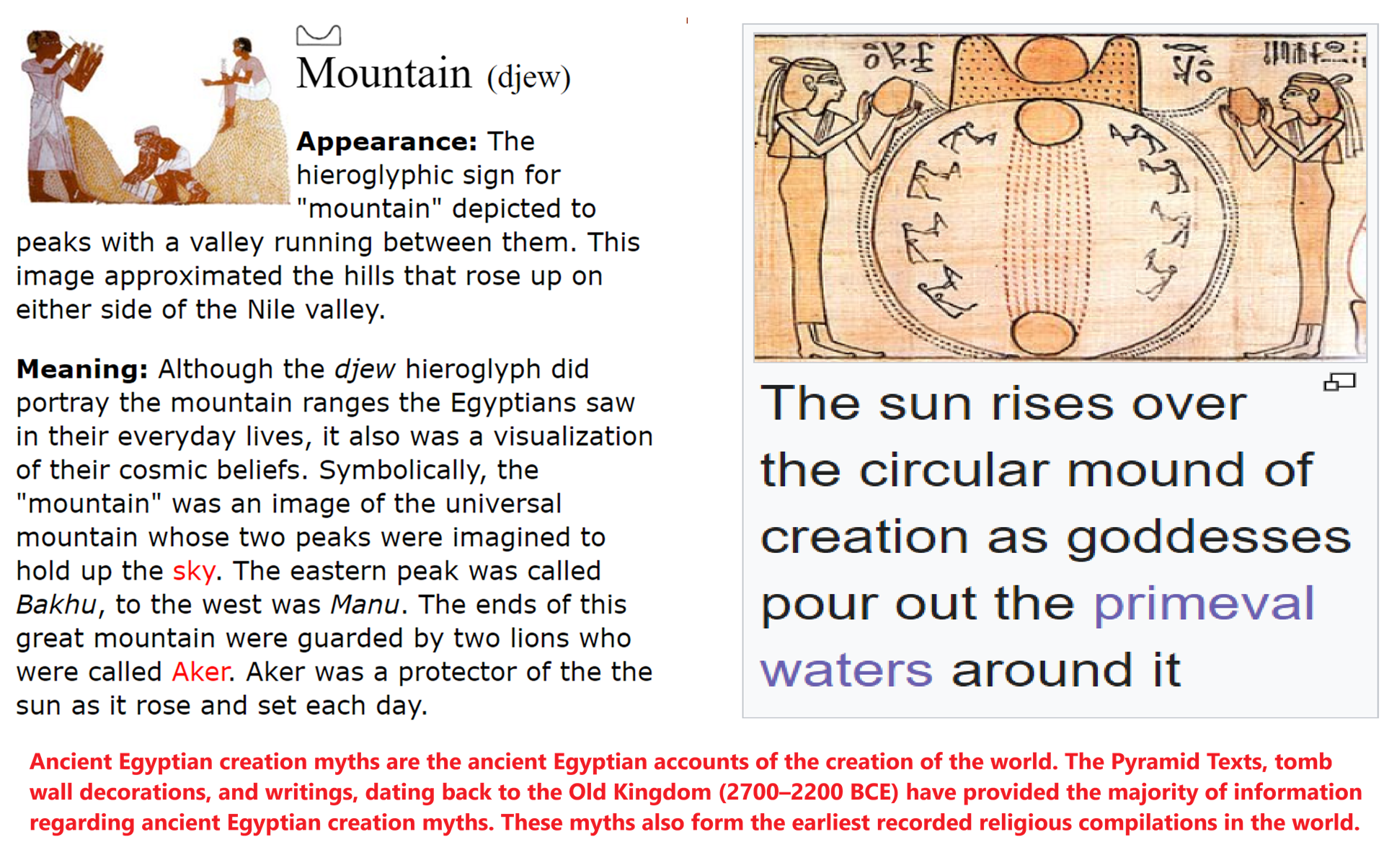

“Nu (“Watery One”) or Nun (“The Inert One”) (Ancient Egyptian: nnw Nānaw; Coptic: Ⲛⲟⲩⲛ Noun), in ancient Egyptian religion, is the personification of the primordial watery abyss which existed at the time of creation and from which the creator sun god Ra arose. Nu is one of the eight deities of the Ogdoad representing ancient Egyptian primordial Chaos from which the primordial mound arose. Nun can be seen as the first of all the gods and the creator of reality and personification of the cosmos. Nun is also considered the god that will destroy existence and return everything to the Nun whence it came. No cult was addressed to Nun.” ref

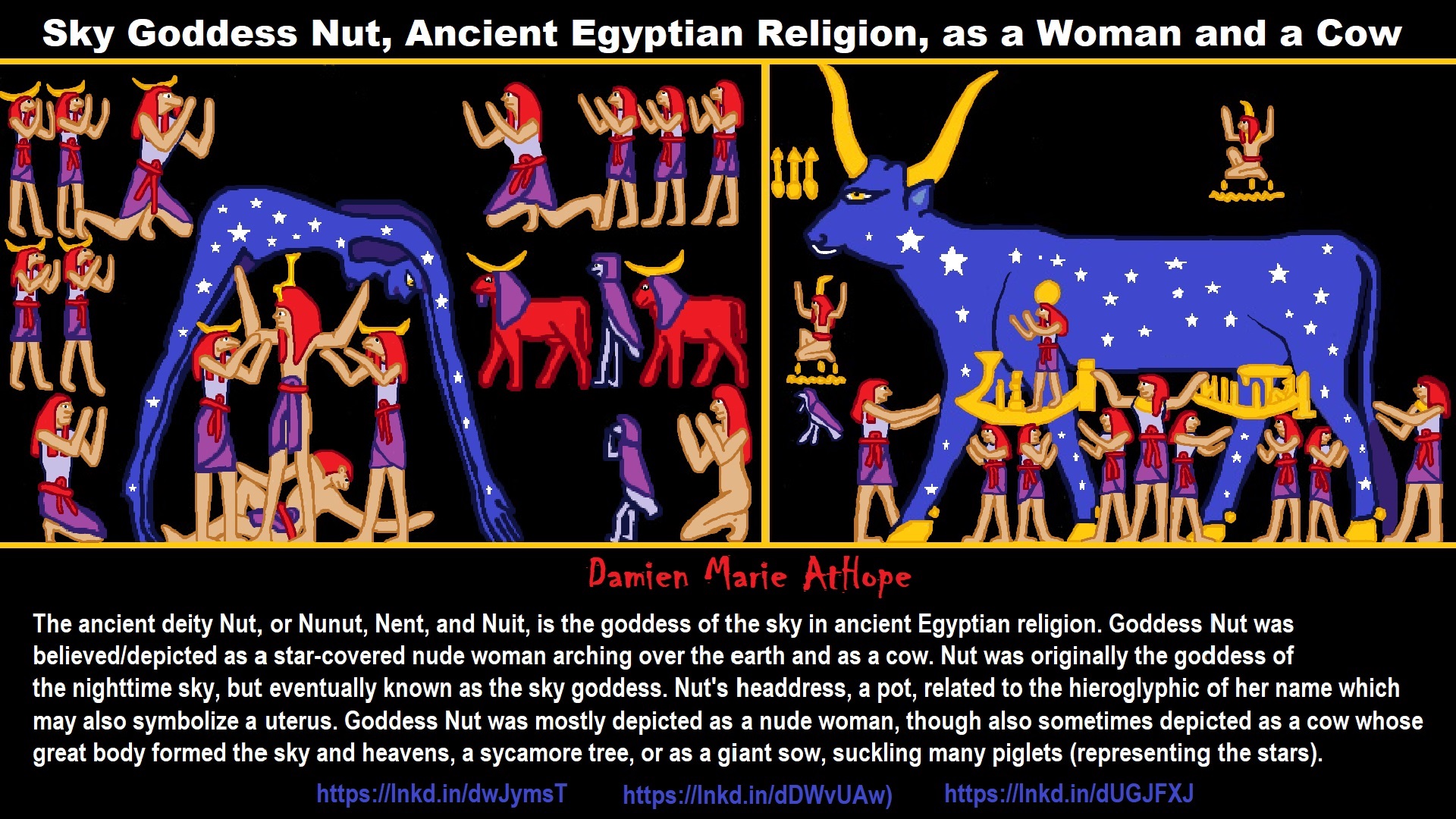

“The ancient Egyptians envisaged the oceanic abyss of the Nun as surrounding a bubble in which the sphere of life is encapsulated, representing the deepest mystery of their cosmogony. In ancient Egyptian creation accounts, the original mound of land comes forth from the waters of the Nun. The Nun is the source of all that appears in a differentiated world, encompassing all aspects of divine and earthly existence. In the Ennead cosmogony, Nun is perceived as transcendent at the point of creation alongside Atum the creator god. In the beginning the universe only consisted of a great chaotic cosmic ocean, and the ocean itself was referred to as Nu. In some versions of this myth, at the beginning of time Mehet-Weret, portrayed as a cow with a sun disk between her horns, gives birth to the sun, said to have risen from the waters of creation and to have given birth to the sun god Ra in some myths.” ref

“The universe was enrapt by a vast mass of primordial waters, and the Benben, a pyramid mound, emerged amid this primal chaos. There was a lotus flower with Benben, and from this when it blossomed emerged Ra. There were many versions of the sun’s emergence, and it was said to have emerged directly from the mound or from a lotus flower that grew from the mound, in the form of a heron, falcon, scarab beetle, or human child. In Heliopolis, the creation was attributed to Atum, a deity closely associated with Ra, who was said to have existed in the waters of Nu as an inert potential being.” ref

“Beginning with the Middle Kingdom, Nun is described as “the father of the gods” and he is depicted on temple walls throughout the rest of ancient Egyptian religious history. The Ogdoad includes along with Naunet and Nun, Amaunet and Amun; Hauhet and Heh; and Kauket and Kek. Like the other Ogdoad deities, Nu did not have temples or any center of worship. Even so, Nu was sometimes represented by a sacred lake, or, as at Abydos, by an underground stream. Nun was depicted as an anthropomorphic large figure and a personification of the primordial waters, with water ripples filling the body, holding a notched palm branch. Nun was also depicted in anthropomorphic form but with the head of a frog, and he was typically depicted in ancient Egyptian art holding aloft the solar barque or the sun disc. He may appear greeting the rising sun in the guise of a baboon.” ref

“Nun is otherwise symbolized by the presence of a sacred cistern or lake as in the sanctuaries of Karnak and Dendara. Nu was shown usually as male but also had aspects that could be represented as female or male. Naunet (also spelt Nunet) is the female aspect, which is the name Nu with a female gender ending. The male aspect, Nun, is written with a male gender ending. As with the primordial concepts of the Ogdoad, Nu’s male aspect was depicted as a frog, or a frog-headed man. In Ancient Egyptian art, Nun also appears as a bearded man, with blue-green skin, representing water. Naunet is represented as a snake or snake-headed woman. In the 12th Hour of the Book of Gates, Nu is depicted with upraised arms holding a solar bark (or barque, a boat). The boat is occupied by eight deities with Khepri, Ra’s morning aspect, standing in the middle and being surrounded by the seven other deities.” ref

“In the local tradition of Eridu, Nammu was regarded as a creator deity. There is no indication in known texts that she had a spouse when portrayed as such. Julia M. Asher-Greve suggests that while generally treated as a goddess, Nammu can be considered asexual in this context. Joan Goodnick Westenholz assumed the process of creation she was involved in was imagined as comparable to parthenogenesis. While primordial figures were often considered to no longer be active by the ancient Mesopotamians, in contrast with other deities, Nammu was apparently believed to still exist as an active figure.” ref

“Nammu was also associated with incantations, apotropaic magic, and tools and materials used in them. In a single incantation she is called bēlet egubbê, “mistress of the holy water basin“, but this epithet was usually regarded as belonging to Ningirima, rather than her. In texts of this genre, she could be invoked in order to purificate or consecrate something, or against demons, illness, or scorpions. Nammu was regarded as the mother of Enki (Ea), as indicated by the myth Enki and Ninmah, the god list An = Anum and a bilingual incantation. However, references to her being his sole parent are less common than the well-attested tradition according to which he was one of the children of Anu. Julia Krul assumes that in the third millennium BCE, Nammu was regarded as the spouse of the latter god.” ref

“She is designated this way in an inscription of Lugal-kisalsi from the Early Dynastic period. However, this is the only known reference to the existence of such a tradition. Wilfred G. Lambert concluded that Nammu had no traditional spouse. In incantations, Nammu could appear alongside deities such as Enki, Asalluhi, and Nanshe. An early literary text known from a copy from Ebla mentions a grouping of deities presumed to share judiciary functions, which includes Nammu, Shamash, Ishtaran, and Idlurugu.” ref

“A single explanatory text equates Nammu with Apsu. It seemingly reinterprets her as a male deity and as the spouse of Nanshe. However, it most likely depends on traditions pertaining to Enūma Eliš and does not represent a separate independent tradition. As of 2017, no clear evidence for the belief in personified Apsu predating the composition of this text was known. Additionally, while the presumed theogony focused on Nammu is the closest possible parallel to Tiamat‘s role in Enūma Eliš, according to Manuel Ceccarelli the two were not closely connected. In particular, there is no evidence Nammu was ever regarded as an antagonistic figure.” ref

“Evidence for the worship of Nammu is scarce in all periods it is attested in. She belonged to the local pantheon of Eridu, and could be referred to as the divine mother of this city. The only indication of an association with a local pantheon other than that of Eridu is the epithet assigned to her in the god list An = Anum (tablet I, line 27), munusagrig-zi-é-kur-(ra-)ke4, “true housekeeper of Ekur,” but it might have only been assigned to her due to confusion with similarly named Ninimma, who was a member of Enlil‘s court. The Early Dynastics zame hymns assign a separate settlement to her, but the reading of its name remains uncertain. Lugal-kisalsi, a king of Uruk, built a temple dedicated to her, but its ceremonial name is not known.” ref

“In the Ur III period, Nammu is attested in various incantations invoking deities associated with Eridu. She received offerings in Ur in the Old Babylonian period, and texts from this location mention the existence of a temple and clergy (including gudu4 priests) dedicated to her, as well as a field named after her. She also appears in the contemporary god list from Nippur as the 107th entry. According to Frans Wiggermann, a kudurru (inscribed boundary stone) inscription indicates that a temple of Nammu existed in the Sealand at least since the reign of Gulkišar, that it remained in use during the reign of Enlil-nadin-apli of the Second Dynasty of Isin, and that its staff included a šangû priest.” ref

“The latter king also invoked her alongside Nanshe in a blessing formula. A dedicatory inscription from the Kassite period which mentions Nammu is also known, though its point of origin remains uncertain. Based on a document most likely written during the reign of Esarhaddon, Nammu was also worshiped in É-DÚR-gi-na, the temple of Lugal-asal in Bāṣ. Shrines named kius-Namma, “footstep of Nammu”, existed in Ekur in Nippur and in Esagil in Babylon. Andrew R. George suggests that the latter, attested in a source from the reign of Nabonidus, was named after the former.” ref

“It is assumed that Nammu was not a popular deity. As of 1998, the only known example of a theophoric name invoking Nammu was that of king Ur-Nammu. Further studies identified no other names invoking her in sources from the Ur III period. However, two further examples have been identified in a more recent survey of texts from Kassite Nippur. Texts dealing with the study of calendars (hemerologies) indicate that the twenty-seventh day of the month could be regarded as a festival of Nammu and Nergal, and prescribe royal offerings to these two deities during it. “Nammu appears in the myth Enki and Ninmah. While the text comes from the Old Babylonian period, it might reflect an older tradition from the Ur III period. Two complete copies most likely postdating the reign of Samsu-iluna are known, in addition to a bilingual Sumero-Akkadian version from the library of Ashurbanipal.” ref

“In the beginning of the composition, Nammu wakes up her son Enki to inform him that other gods are complaining about the heavy tasks assigned to them. As a solution, he suggests the creation of mankind, and instructs Nammu how to form men from clay with the help of Ninmah and her assistants (Ninimma, Shuzianna, Ninmada, Ninšar, Ninmug, Mumudu and Ninnigina according to Wilfred G. Lambert‘s translation). After the task is finished, Enki prepares a banquet for Nammu and Ninmah, which other deities, such as Anu, Enlil and the seven assistants, also attend. Nammu’s presence sets the account of creation of mankind in this myth from other compositions dealing with the same topic, such as Atra-Hasis.” ref

“Du-Ku is a Sumerian word for a sacred place, which translates as “holy hill”, “holy mound” – E-dul-kug – (House which is the holy mound), “shining” a cultic and cosmic place, or “great mountain.” The hill was the location for ritual offerings to Sumerian god(s), and goddess Nungal as well as the god Anunna (or gods) dwell upon the holy hill. Also, Du-Ku is alluded to in sacred texts as a specifically identified place of godly judgement.” ref

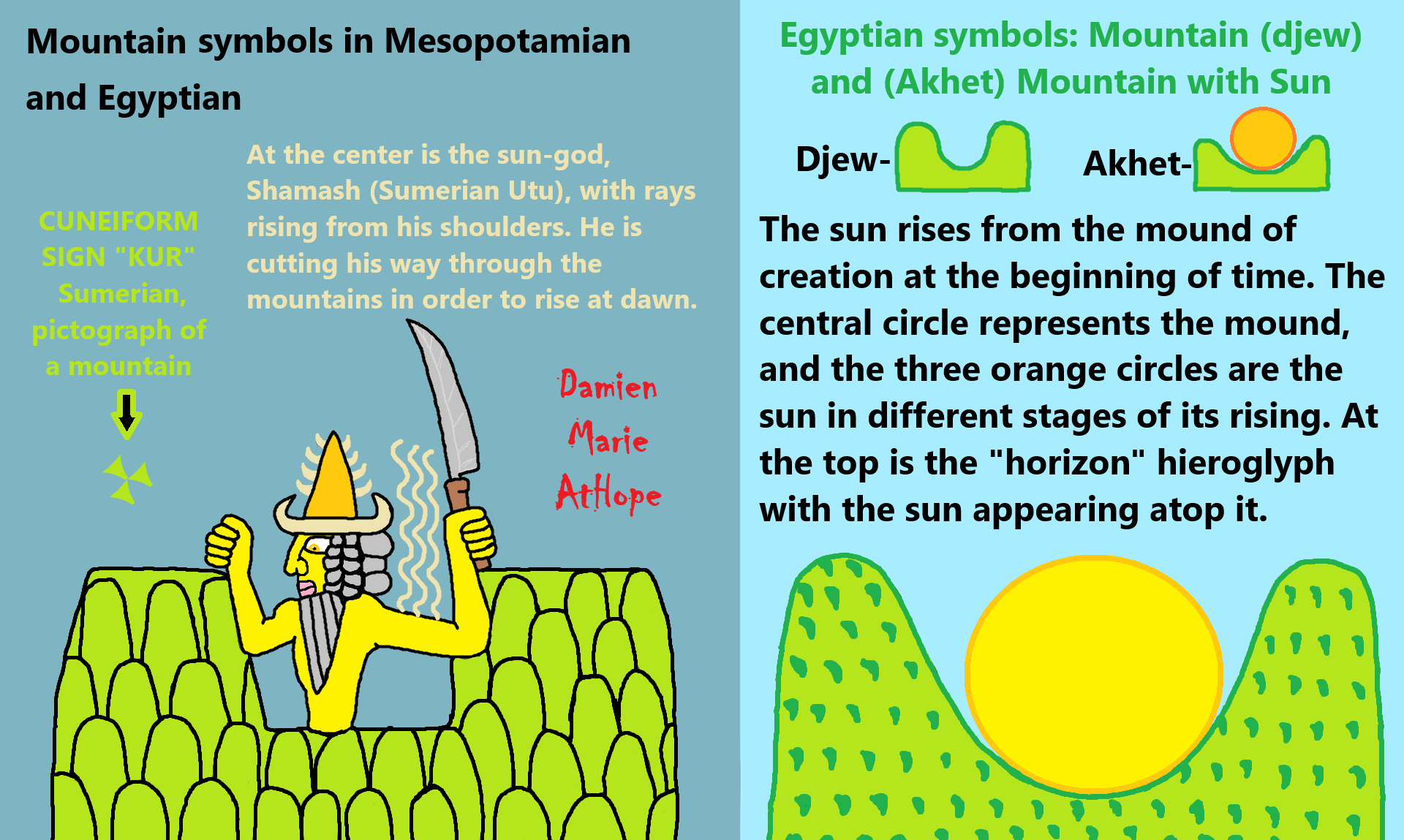

Hursag is a Sumerian term variously translated as “mountain,” “hill,” “foothills,” or “head of the valleys.” Mountains play a certain role in Mesopotamian mythology and Assyro-Babylonian religion, associated with deities such as Anu, Enlil, Enki, and Ninhursag. Hursag is the first word written on tablets found at the ancient Sumerian city of Nippur, dating to the third millennium BCE, Making it possibly the oldest surviving written word in the world.” ref

“Du-Ku According to Wasilewska et al., du-ku translates as “holy hill”, “holy mound” […E-dul-kug… (House which is the holy mound)], or “great mountain.” Du-Ku or dul-kug [du6-ku3] is a Sumerian word for a sacred place. According to the University of Pennsylvania online dictionary of Sumerian and Akkadian languages, du-ku is actually du6-ku3, with du6 being defined as a mound or ruin mound, and ku3 as either ritually pure or shining: it is used in the texts on the Univ. of Oxford site as “shining”. There is no mention of nor association with the term “holy”, and instead it represents a cultic and cosmic place. The location is otherwise alluded to in sacred texts as a specifically identified place of godly judgement. The hill was the location for ritual offerings to Sumerian god(s). Nungal and the Anunna dwell upon the holy hill in a text written from Gilgamesh.” ref

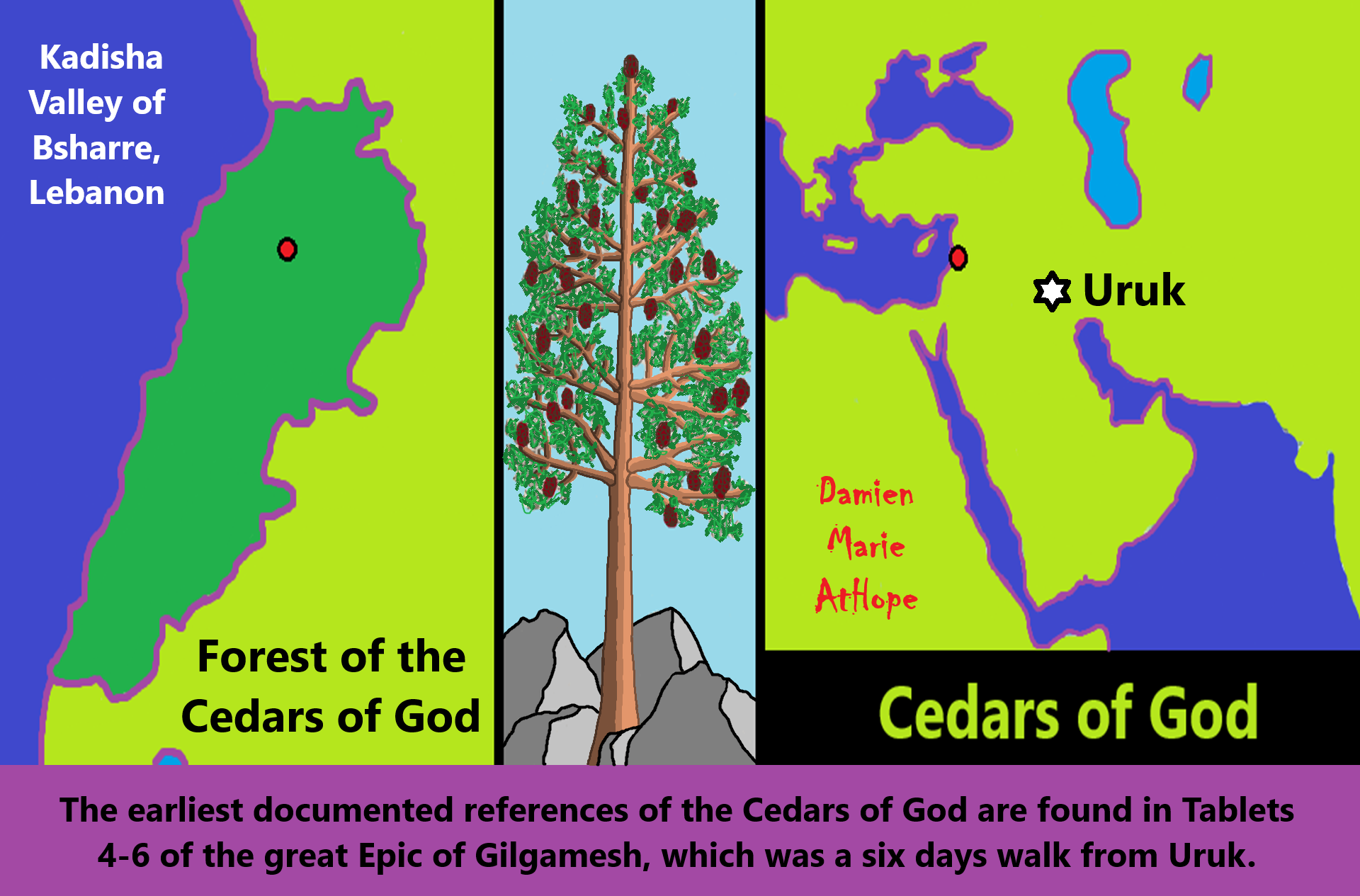

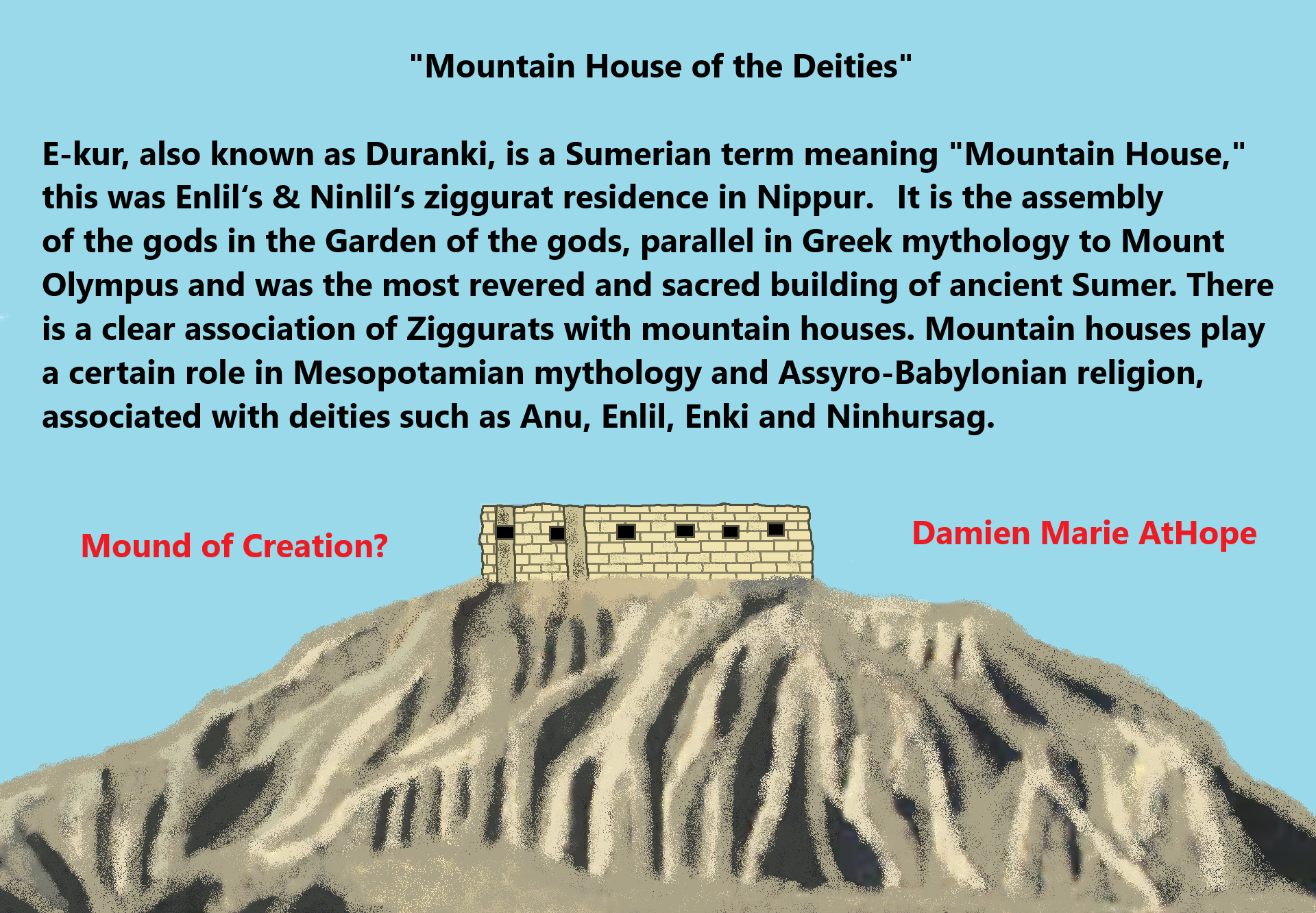

“Ekur (𒂍𒆳 É.KUR), also known as Duranki, is a Sumerian term meaning “mountain. One of the tablets contains a creation myth, the so-called Debate between Sheep and Grain. It begins with a mountain: “On the mountain of heaven and earth, Anu spawned the Annunaki gods.” In fact, “mountain” (ḫur-saĝ) is the very first word on the tablet and could be the oldest written word. Early in the story, heaven and earth are fused together in a site described as the mountain (ḫur-saĝ) of the supreme sky god Anu. On the slopes of the primordial mountain, primitive man existed, naked and feeding on grasses like cattle. Little else existed, so Anu created the other, lesser gods and goddesses — the Annunaki —who, in turn, created sheep and grain for food. Unsatisfied, the gods “sent down” sheep and grain “from the Holy Mound” to “mankind as sustenance.” ref

“There is more to the story than this. But the opening lines of the clay tablet are important because they are the earliest extant textual references linking mountains with gods and fertility. And there are more from the same period. In another Sumerian creation story, Enki and Ninhursag, a certain Mount Dilmun (kur dilmun) is described as a paradise.4 Indeed, the fertility goddess Ninhursag’s name literally means “lady of the sacred mountain.” It should be noted here that the god Enki, with whom Ninhursag bears children, is the god of water. In yet another Sumerian story, Debate Between Winter and Summer, the god Enlil copulates with a mountain (hur-saj) and impregnates it “with Summer and Winter, the plenitude and life of the Land.” ref

ḫur-saĝ

“O E-ninnu (House of 50), right hand of Lagaš, foremost in Sumer, the Anzud bird which gazes upon the mountain, the šar-ur weapon of …… Ninĝirsu, …… in all lands, the strength of battle, a terrifying storm which envelops men, giving the strength of battle to the Anuna, the great gods, brick building on whose holy mound destiny is determined, beautiful as the hills, your canal ……, your …… blowing in opposition (?) at your gate facing towards Iri-kug, wine is poured into holy An’s beautiful bowls set out in the open air.” ref

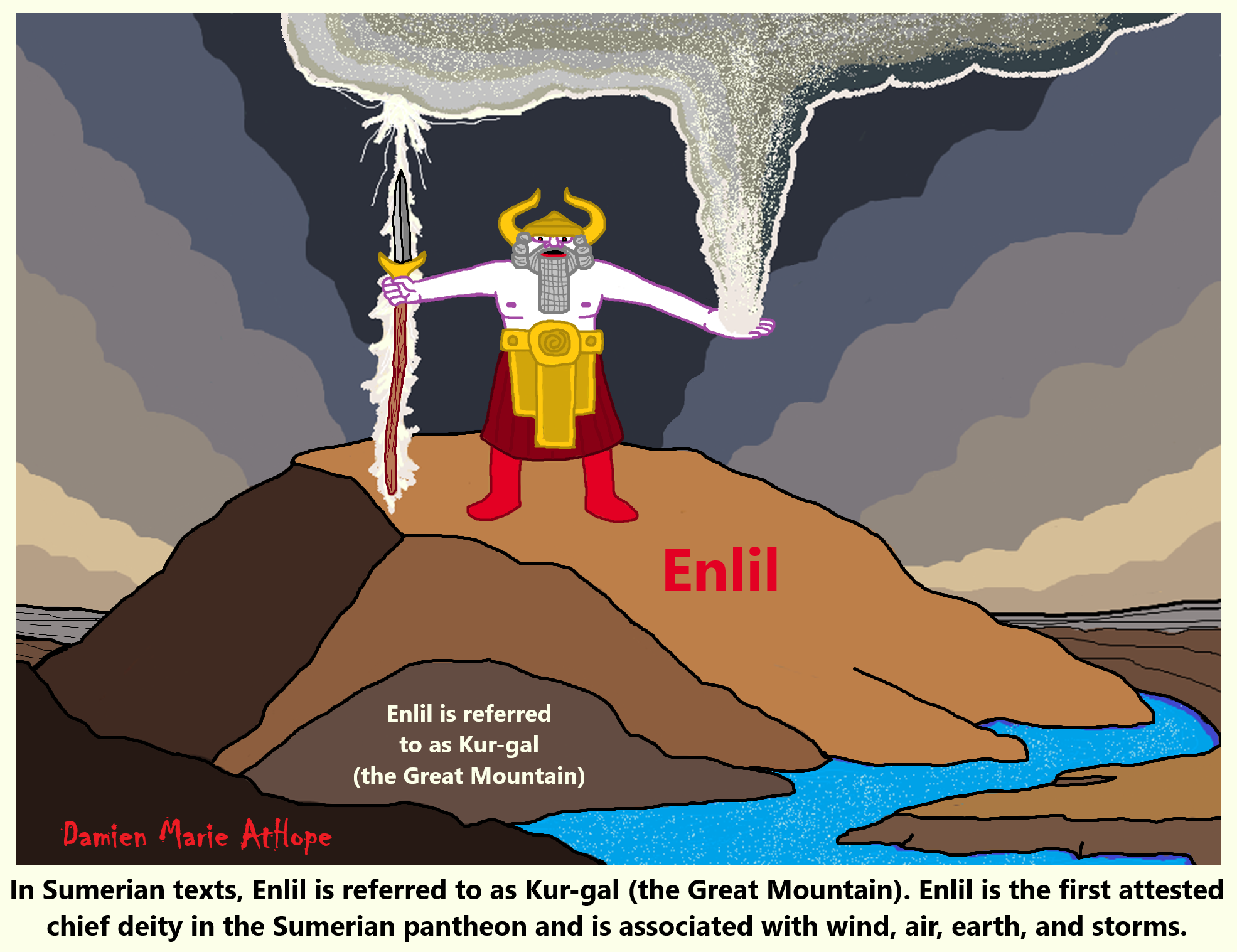

“The Hymn to Enlil, Enlil and the Ekur (Enlil A), Hymn to the Ekur, Hymn and incantation to Enlil, Hymn to Enlil the all beneficent or Excerpt from an exorcism is a Sumerian myth, written on clay tablets in the late third millennium BCE and found at the temple library at Nippur. The name given this time was “Hymn to the Ekur,” suggesting the tablets were “parts of a composition which extols the ekur of Enlil at Nippur. The hymn, noted by Kramer as one of the most important of its type, starts with praise for Enlil in his awe-inspiring dais: Enlil’s commands are by far the loftiest, his words are holy, his utterances are immutable! The fate he decides is everlasting, his glance makes the mountains anxious, his … reaches into the interior of the mountains. All the gods of the earth bow down to father Enlil, who sits comfortably on the holy dais, the lofty engur, to Nunamnir, whose lordship and princeship are most perfect. The Annanuki enter before him and obey his instructions faithfully.” ref

“The hymn develops by relating Enlil’s founding and creating the origin of the city of Nippur and his organization of the earth. In contrast to the myth of Enlil and Ninlil where the city exists before creation, here Enlil is shown to be responsible for its planning and construction, suggesting he surveyed and drew the plans before its creation: When you mapped out the holy settlement on the earth, You built the city Nippur by yourself, Enlil. The Kiur, your pure place. In the Duranki, in the middle of the four quarters of the earth, you founded it. Its soil is the life of the land (Sumer). The hymn moves on from the physical construction of the city and gives a description and veneration of its ethics and moral code: The powerful lord, who is exceedingly great in heaven and earth, who knows judgment, who is wise. He, of great wisdom, takes his seat in the Duranki. In princeship, he makes the Kiur, the great place, come forth radiantly. In Nippur, the ‘bond’ of heaven and earth, he establishes his place of residence. The City – its panorama is a terrifying radiance. To him who speaks mightily, it does not grant life.” ref

“It permits no inimical word to be spoken in judgement, no improper speech, hostile words, hostility, and unseemingliness, no evil, oppression, looking askance, acting without regard, slandering, arrogance, the breaking of promises. These abominations the city does not permit. The evil and wicked man do not escape its hand. The city, which is bestowed with steadfastness. For which righteousness and justice have been made a lasting possession. The last sentence has been compared by R. P. Gordon to the description of Jerusalem in the Book of Isaiah (Isaiah 1:21), “the city of justice, righteousness dwelled in her” and in the Book of Jeremiah (Jeremiah 31:23), “O habitation of justice, and mountain of holiness.” The myth continues with the city’s inhabitants building a temple dedicated to Enlil, referred to as the Ekur. The priestly positions and responsibilities of the Ekur are listed along with an appeal for Enlil’s blessings on the city, where he is regarded as the source of all prosperity:” ref

“Without the Great Mountain, Enlil, no city would be built, no settlement would be founded; no cow-pen would be built, no sheepfold would be established; no king would be elevated, no lord would be given birth; no high priest or priestess would perform extispicy; soldiers would have no generals or captains; no carp-filled waters would … the rivers at their peak; the carp would not … come straight up from the sea, they would not dart about. The sea would not produce all its heavy treasure, no freshwater fish would lay eggs in the reedbeds, no bird of the sky would build nests in the spacious land; in the sky the thick clouds would not open their mouths; on the fields, dappled grain would not fill the arable lands, vegetation would not grow lushly on the plain; in the gardens, the spreading forests of the mountain would not yield fruits.” ref

“Without the Great Mountain, Enlil, Nintud would not kill, she would not strike dead; no cow would drop its calf in the cattle-pen, no ewe would bring forth … lamb in its sheepfold; the living creatures which multiply by themselves would not lie down in their …; the four-legged animals would not propagate, they would not mate. A similar passage to the last lines above has been noted in the Biblical Psalms (Psalms 29:9): “The voice of the Lord makes hinds to calve and makes goats to give birth (too) quickly.” The hymn concludes with further reference to Enlil as a farmer and praise for his wife, Ninlil: When it relates to the earth, it brings prosperity: the earth will produce prosperity. Your word means flax, your word means grain. Your word means the early flooding, the life of the lands. It makes the living creatures, the animals (?) which copulate and breathe joyfully in the greenery.” ref

“You, Enlil, the good shepherd, know their ways … the sparkling stars. You married Ninlil, the holy consort, whose words are of the heart, her of noble countenance in a holy ma garment, her of beautiful shape and limbs, the trustworthy lady of your choice. Covered with allure, the lady who knows what is fitting for the E-kur, whose words of advice are perfect, whose words bring comfort like fine oil for the heart, who shares the holy throne, the pure throne with you, she takes counsel and discusses matters with you. You decide the fates together at the place facing the sunrise. Ninlil, the lady of heaven and earth, the lady of all the lands, is honored in praise of the Great Mountain. Andrew R. George suggested that the hymn to Enlil “can be incorporated into longer compositions” as with the Kesh temple hymn and “the hymn to temples in Ur that introduces a Shulgi hymn.” ref

“The poetic form and laudatory content of the hymn have shown similarities to the Book of Psalms in the Bible, particularly Psalm 23 (Psalms 23:1–2) “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want, he maketh me to lie down in green pastures.” Line eighty-four mentions: Enlil, if you look upon the shepherd favourably, if you elevate the one truly called in the Land, then the foreign countries are in his hands, the foreign countries are at his feet! Even the most distant foreign countries submit to him. and in line ninety-one, Enlil is referred to as a shepherd: Enlil, faithful shepherd of the teeming multitudes, herdsman, leader of all living creatures.” ref

“The shepherd motif originating in this myth is also found describing Jesus in the Book of John (John 10:11–13). Joan Westenholz noted that “The farmer image was even more popular than the shepherd in the earliest personal names, as might be expected in an agrarian society.” She notes that both Falkenstein and Thorkild Jacobsen consider the farmer refers to the king of Nippur; Reisman has suggested that the farmer or ‘engar’ of the Ekur was likely to be Ninurta. The term appears in line sixty.” ref

“Its great farmer is the good shepherd of the Land, who was born vigorous on a propitious day. The farmer, suited for the broad fields, comes with rich offerings; he does not …… into the shining E-kur. Wayne Horowitz discusses the use of the word abzu, normally used as a name for an abzu temple, god, cosmic place or cultic water basin. In the hymn to Enlil, its interior is described as a ‘distant sea’: Its (Ekur’s) me‘s (ordinances) are mes of the Abzu which no-one can understand. Its interior is a distant sea which ‘Heaven’s Edge’ cannot comprehend.” ref

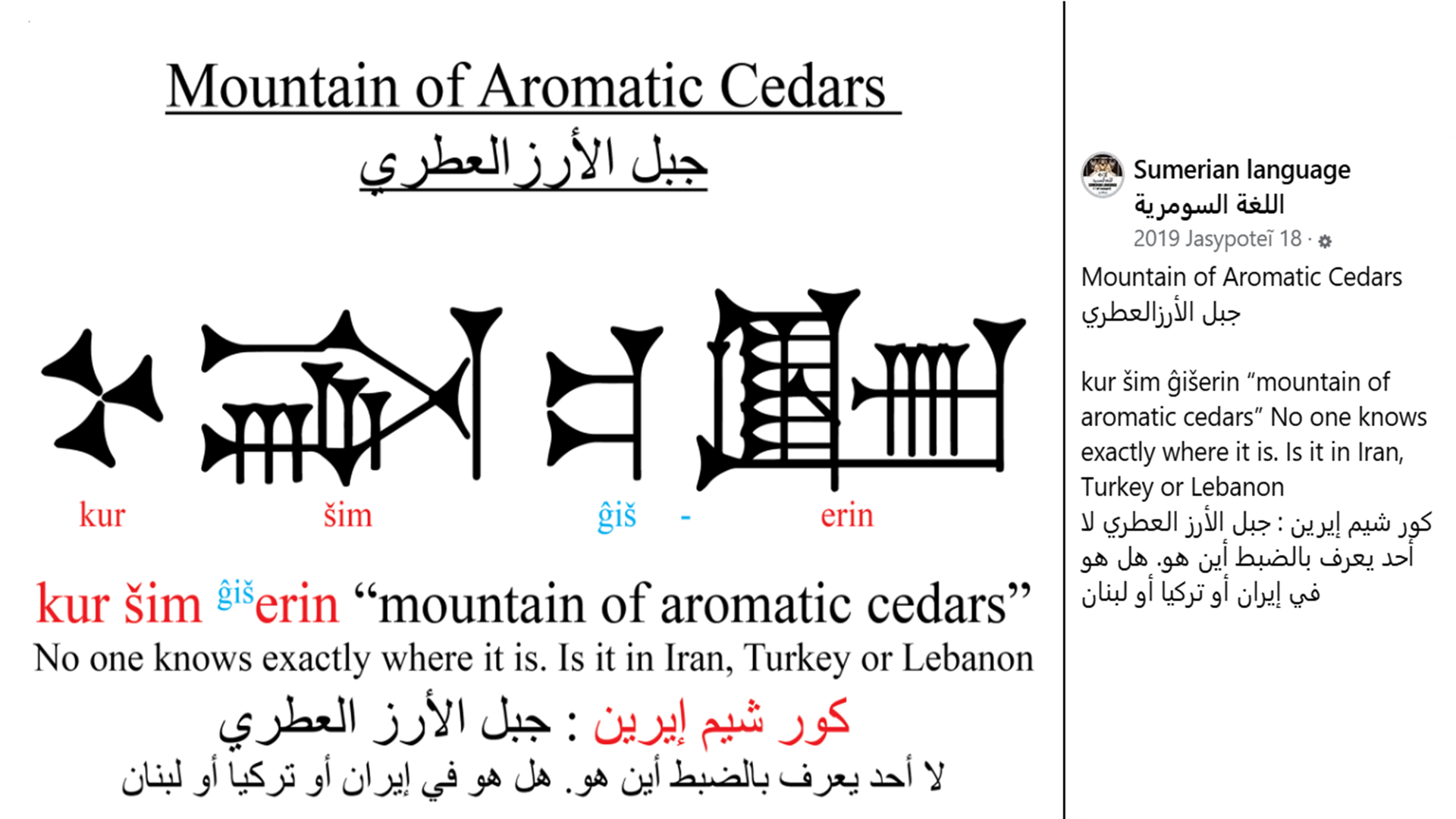

“The foundations of Enlil’s temple are made of lapis lazuli, which has been linked to the “soham” stone used in the Book of Ezekiel (Ezekiel 28:13) describing the materials used in the building of “Eden, the Garden of god“ perched on “the mountain of the lord”, Zion, and in the Book of Job (Job 28:6–16) “The stones of it are the place of sapphires and it hath dust of gold”. Moses also saw God’s feet standing on a “paved work of a sapphire stone” in (Exodus 24:10). Precious stones are also later repeated in a similar context describing decoration of the walls of New Jerusalem in the Apocalypse (Revelation 21:21).” ref

“You founded it in the Dur-an-ki, in the middle of the four quarters of the earth. Its soil is the life of the Land, and the life of all the foreign countries. Its brickwork is red gold, its foundation is lapis lazuli. You made it glisten on high. Along with the Kesh Temple Hymn, Steve Tinney has identified the Hymn to Enlil as part of a standard sequence of scribal training scripts he refers to as the Decad. He suggested that “the Decad constituted a required program of literary learning, used almost without exception throughout Babylonia. The Decad thus included almost all literary types available in Sumerian.” ref

“Tien Shan, great mountain system of Central Asia. Its name is Chinese for “Celestial Mountains.” Stretching about 1,500 miles (2,500 km) from west-southwest to east-northeast, it mainly straddles the border between China and Kyrgyzstan and bisects the ancient territory of Turkistan. It is about 300 miles (500 km) wide in places at its eastern and western extremities but narrows to about 220 miles (350 km) in width at the center. The Tien Shan is bounded to the north by the Junggar (Dzungarian) Basin of northwestern China and the southern Kazakhstan plains and to the southeast by the Tarim (Talimu) Basin. To the southwest, the Hisor (Gissar) and Alay ranges of Tajikistan extend into part of the Tien Shan, making the Alay, Surkhandarya, and Hisor valleys boundaries of the system, along with the Pamirs to the south. The Tien Shan also includes the Shū-Ile Mountains and the Qarataū Range, which extend far to the northwest into the eastern Kazakhstan lowlands. Within these limits, the total area of the Tien Shan is about 386,000 square miles (1,000,000 square km).” ref

“The tallest peaks in the Tien Shan are a central cluster of mountains forming a knot, from which ridges extend along the boundaries between China, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan; these peaks are Victory Peak (Kyrgyz, Jengish Chokusu; Russian, Pik Pobedy), which at 24,406 feet (7,439 meters) is the highest mountain in the range, and Khan Tängiri Peak (Kyrgyz, Kan-Too Chokusu), which reaches 22,949 feet (6,995 meters) and is the highest point in Kazakhstan. The ranges are of the alpine type, with steep slopes; glaciers occur along their crests. The basins are bounded to the south by the low-rising Qoltag Mountains. West of the Turfan Depression is one of the greatest mountain knots of the eastern Tien Shan: the Eren Habirga Mountains, which reach elevations of 18,200 feet (5,550 meters). The ridge has considerable glacial development, as well as numerous forms of relief that indicate the area was the site of ancient glaciation.” ref

Tian Shan and Tengrism

“It is the highest part of the range – the Central Tian Shan, with Peak Pobeda (Kakshaal Too range) and Khan Tengri. In Tengrism, Khan Tengri, is the lord of all spirits and the religion’s supreme deity, and it is the name given to the second highest peak of Tian Shan. One of the earliest historical references to these mountains may be related to the Xiongnu word Qilian (traditional Chinese: 祁連; simplified Chinese: 祁连; pinyin: Qílián), which, according to Tang commentator Yan Shigu, is the Xiongnu word for “sky” or “heaven.” Sima Qian, in the Records of the Grand Historian, mentioned Qilian in relation to the homeland of the Yuezhi, and the term is believed to refer to the Tian Shan rather than the range 1,500 kilometers (930 mi) further east now known as the Qilian Mountains. The name of the Tannu-Ola mountains in Tuva has the same meaning. The Chinese name Tian Shan is most likely a direct translation of the traditional Kyrgyz name for the mountains, Teñir Too. Khan Tengri is a mountain of the Tian Shan mountain range in Central Asia. It is on the China—Kyrgyzstan—Kazakhstan tripoint, east of Lake Issyk Kul. The name “Khan Tengri” literally means “King Heaven” in Kazakh or “King Sky” in Mongolian and possibly references the sky deity Tengri that both exist in the religion of Tengrism and Central Asian Buddhism. Local residents named the mountain Khan-Tengri for the unique beauty of snow giants. Khan Tengri is a massive marble pyramid, covered in snow and ice. At sunset, the marble glows red, giving it the name “blood mountain” in Kazakh and Kyrgyz (Kazakh: Қантау; Kyrgyz: Кан-Тоо).” ref

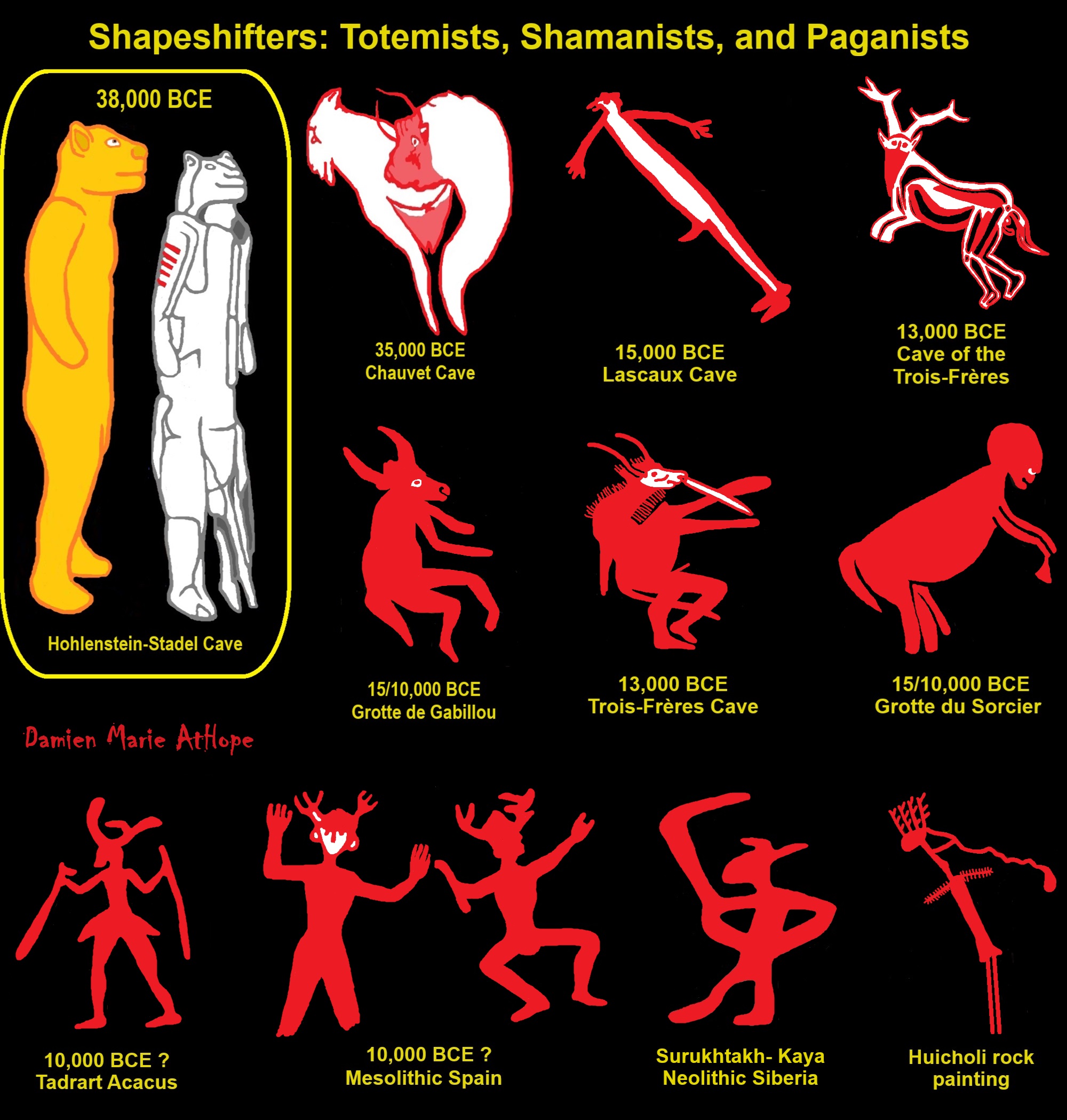

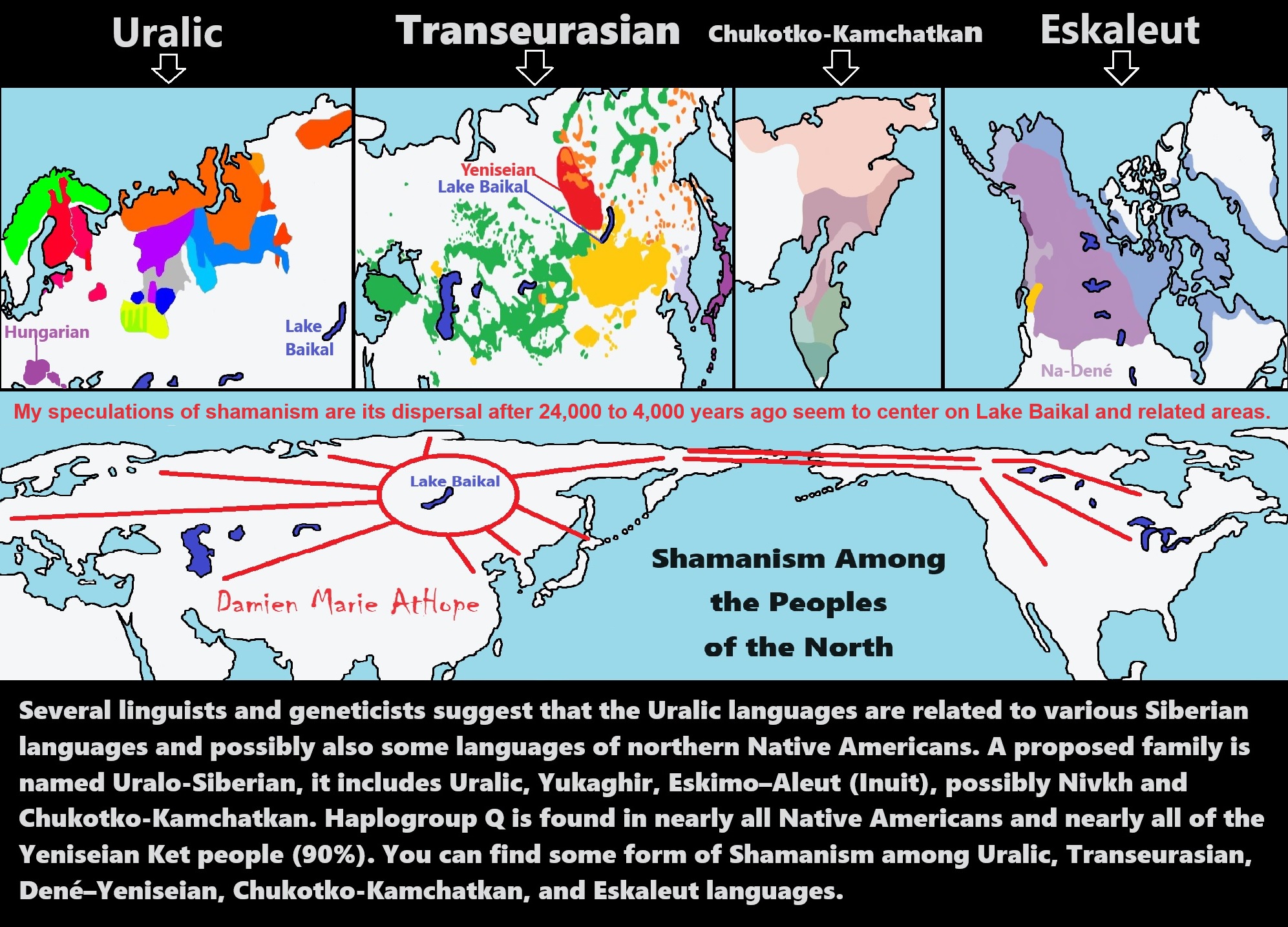

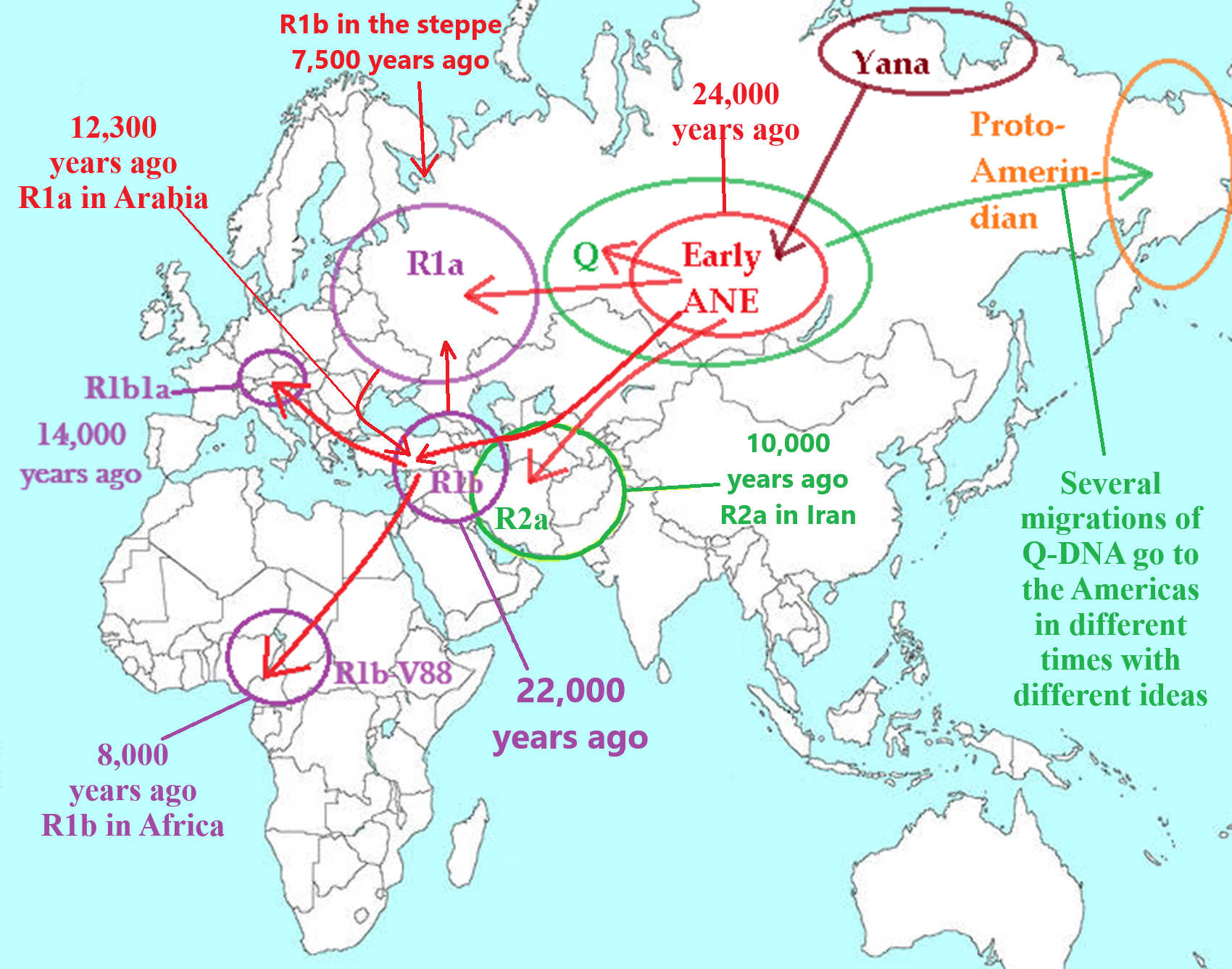

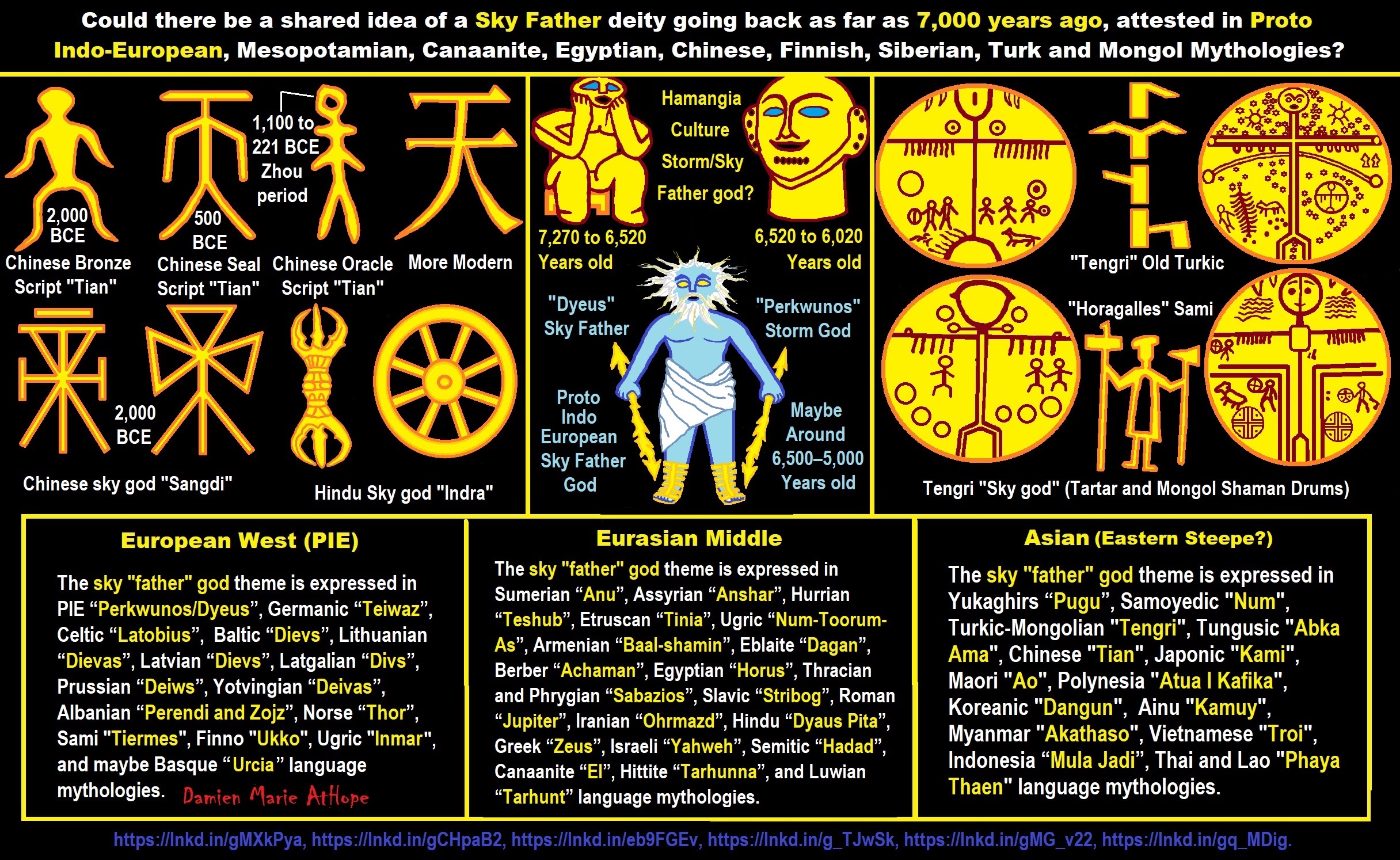

“Tengrianism) is a religion originating in the Eurasian steppes, based on shamanism and animism. It generally involves the titular sky god Tengri, who is not considered a deity in the usual sense but a personification of the universe. According to some scholars, adherents of Tengrism view the purpose of life to be in harmony with the universe. It was the prevailing religion of the Göktürks, Xianbei, Bulgars, Xiongnu, Yeniseian, and Mongolic peoples and Huns, as well as the state religion of several medieval states such as the First Turkic Khaganate, the Western Turkic Khaganate, the Eastern Turkic Khaganate, Old Great Bulgaria, the First Bulgarian Empire, Volga Bulgaria, Khazaria, and the Mongol Empire. In the Irk Bitig, a ninth-century manuscript on divination, Tengri is mentioned as Türük Tängrisi (God of Turks). According to many academics, Tengrism was, and to some extent still is, a predominantly polytheistic religion based on the shamanistic concept of animism, and was first influenced by monotheism during the imperial period, especially by the 12th–13th centuries. Abdulkadir Inan argues that Yakut and Altai shamanism are not entirely equal to the ancient Turkic religion.” ref

“The term also describes several contemporary Turkic and Mongolic native religious movements and teachings. All modern adherents of “political” Tengrism are monotheists. Tengrism has been advocated for in intellectual circles of the Turkic nations of Central Asia (Kyrgyzstan with Kazakhstan) and Russia (Tatarstan, Bashkortostan) since the dissolution of the Soviet Union during the 1990s. Still practiced, it is undergoing an organized revival in Buryatia, Sakha (Yakutia), Khakassia, Tuva, and other Turkic nations in Siberia. Altaian Burkhanism and Chuvash Vattisen Yaly are contemporary movements similar to Tengrism. The term tengri (compare with Kami) can refer to the sky deity Tenger Etseg – also Gök Tengri; Sky father, Blue sky – or to other deities. While Tengrism includes the worship of personified gods (tngri) such as Ülgen and Kayra, Tengri is considered an “abstract phenomenon”. In Mongolian folk religion, Genghis Khan is considered one of the embodiments, if not the main embodiment, of Tengri’s will.” ref

“The forms of the name Tengri (Old Turkic: Täŋri) among the ancient and modern Turkic and Mongolic are Tengeri, Tangara, Tangri, Tanri, Tangre, Tegri, Tingir, Tenkri, Tangra, Teri, Ter, and Ture. The name Tengri (“the Sky”) is derived from Old Turkic: Tenk (“daybreak”) or Tan (“dawn”). Meanwhile, Stefan Georg proposed that the Turkic Tengri ultimately originates as a loanword from Proto-Yeniseian *tɨŋgɨr- “high.” Mongolia is sometimes poetically called the “Land of Eternal Blue Sky” (Mönkh Khökh Tengeriin Oron) by its inhabitants. According to some scholars, the name of the important deity Dangun (also Tangol) (God of the Mountains) of the Korean folk religion is related to the Siberian Tengri (“Heaven”), while the bear is a symbol of the Big Dipper (Ursa Major).” ref

“The spellings Tengriism, Tangrism, Tengrianity are also found from the 1990s. In modern Turkey and, partly, Kyrgyzstan, Tengrism is known as the Tengricilik or Göktanrı dini (“Sky God religion”); the Turkish gök (sky) and tanrı (God) corresponds to the Mongolian khukh (blue) and Tengeri (sky), respectively. Mongolian Тэнгэр шүтлэг is used in a 1999 biography of Genghis Khan. The nature of this religion remains debatable. According to many scholars, it was originally polytheistic, but a monotheistic branch with the sky god Kök-Tengri as the supreme being evolved as a dynastical legitimation. It is at least agreed that Tengrism formed from the diverse folk religions of the local people and may have had diverse branches.” ref

“It is suggested that Tengrism was a monotheistic religion only at the imperial level in aristocratic circles, and, perhaps, only by the 12th-13th centuries (a late form of development of ancient animistic shamanism in the era of the Mongol empire). According to Jean-Paul Roux, the monotheistic concept evolved later out of a polytheistic system and was not the original form of Tengrism. The monotheistic concept helped to legitimate the rule of the dynasty: “As there is only one God in Heaven, there can only be one ruler on the earth …”. Others point out that Tengri itself was never an Absolute, but only one of many gods of the upper world, the sky deity, of polytheistic shamanism, later known as Tengrism.” ref

“Tengrism differs from contemporary Siberian shamanism in that it was a more organized religion. Additionally, the polities practicing it were not small bands of hunter-gatherers like the Paleosiberians, but a continuous succession of pastoral, semi-sedentarized khanates and empires from the Xiongnu Empire (founded 209 BC) to the Mongol Empire (13th century). In Mongolia, it survives as a synthesis with Tibetan Buddhism while surviving in purer forms around Lake Khovsgol and Lake Baikal. Unlike Siberian shamanism, which has no written tradition, Tengrism can be identified from Turkic and Mongolic historical texts like the Orkhon inscriptions, Secret History of the Mongols, and Altan Tobchi. However, these texts are more historically oriented and are not strictly religious texts like the scriptures and sutras of sedentary civilizations, which have elaborate doctrines and religious stories.” ref

“On a scale of complexity, Tengrism lies somewhere between the Proto-Indo-European religion (a pre-state form of pastoral shamanism on the western steppe) and its later form the Vedic religion. The chief god Tengri (“Heaven”) is considered strikingly similar to the Indo-European sky god *Dyḗus and the East Asian Tian (Chinese: “Sky; Heaven”). The structure of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European religion is actually closer to that of the early Turks than to the religion of any people of neolithic European, Near Eastern, or Mediterranean antiquity. The term “shamanism” was first applied by Western anthropologists as outside observers of the ancient religion of the Turkic and Mongolic peoples, as well as those of the neighboring Tungusic and Samoyedic-speaking peoples. Upon observing more religious traditions across the world, some Western anthropologists began to also use the term in a very broad sense. The term was used to describe unrelated magico-religious practices found within the ethnic religions of other parts of Asia, Africa, Australasia, and even completely unrelated parts of the Americas, as they believed these practices to be similar to one another.” ref

“Terms for ‘shaman’ and ‘shamaness’ in Siberian languages:

- ‘shaman’: saman (Nedigal, Nanay, Ulcha, Orok), sama (Manchu). The variant /šaman/ (i.e., pronounced “shaman”) is Evenk (whence it was borrowed into Russian).

- ‘shaman’: alman, olman, wolmen (Yukagir)

- ‘shaman’: [qam] (Tatar, Shor, Oyrat), [xam] (Tuva, Tofalar)

- The Buryat word for shaman is бөө (böö) [bøː], from early Mongolian böge.

- ‘shaman’: ńajt (Khanty, Mansi), from Proto-Uralic *nojta (cf. Sámi noaidi)

- ‘shamaness’: [iduɣan] (Mongol), [udaɣan] (Yakut), udagan (Buryat), udugan (Evenki, Lamut), odogan (Nedigal). Related forms found in various Siberian languages include utagan, ubakan, utygan, utügun, iduan, or duana. All these are related to the Mongolian name of Etügen, the hearth goddess, and Etügen Eke ‘Mother Earth’. Maria Czaplicka points out that Siberian languages use words for male shamans from diverse roots, but the words for female shaman are almost all from the same root. She connects this with the theory that women’s practice of shamanism was established earlier than men’s, that “shamans were originally female.” ref

Buryat scholar Irina S. Urbanaeva developed a theory of Tengrist esoteric traditions in Central Asia after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the revival of national sentiment in the former Soviet republics of Central Asia.

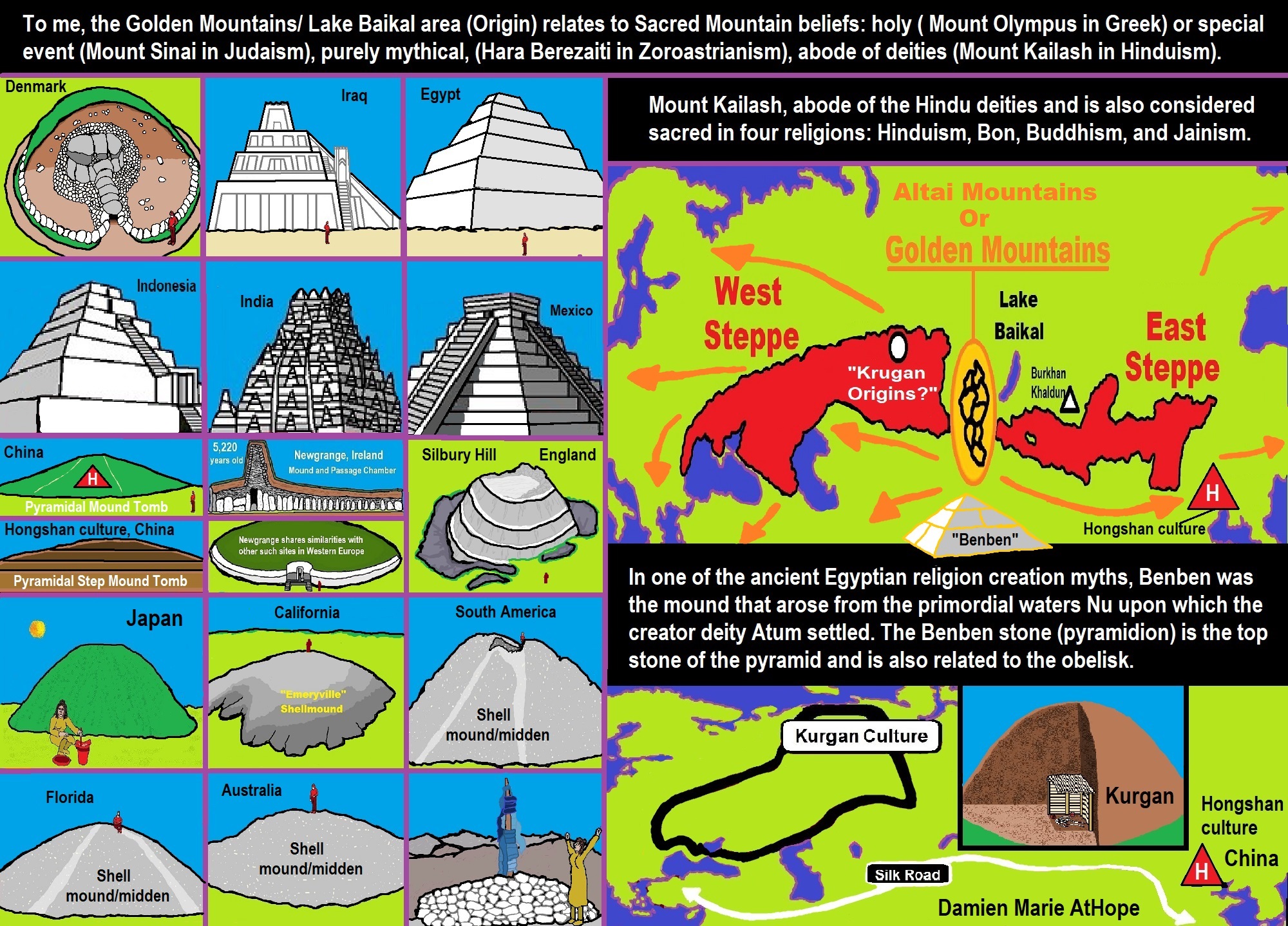

Cosmic Mountain

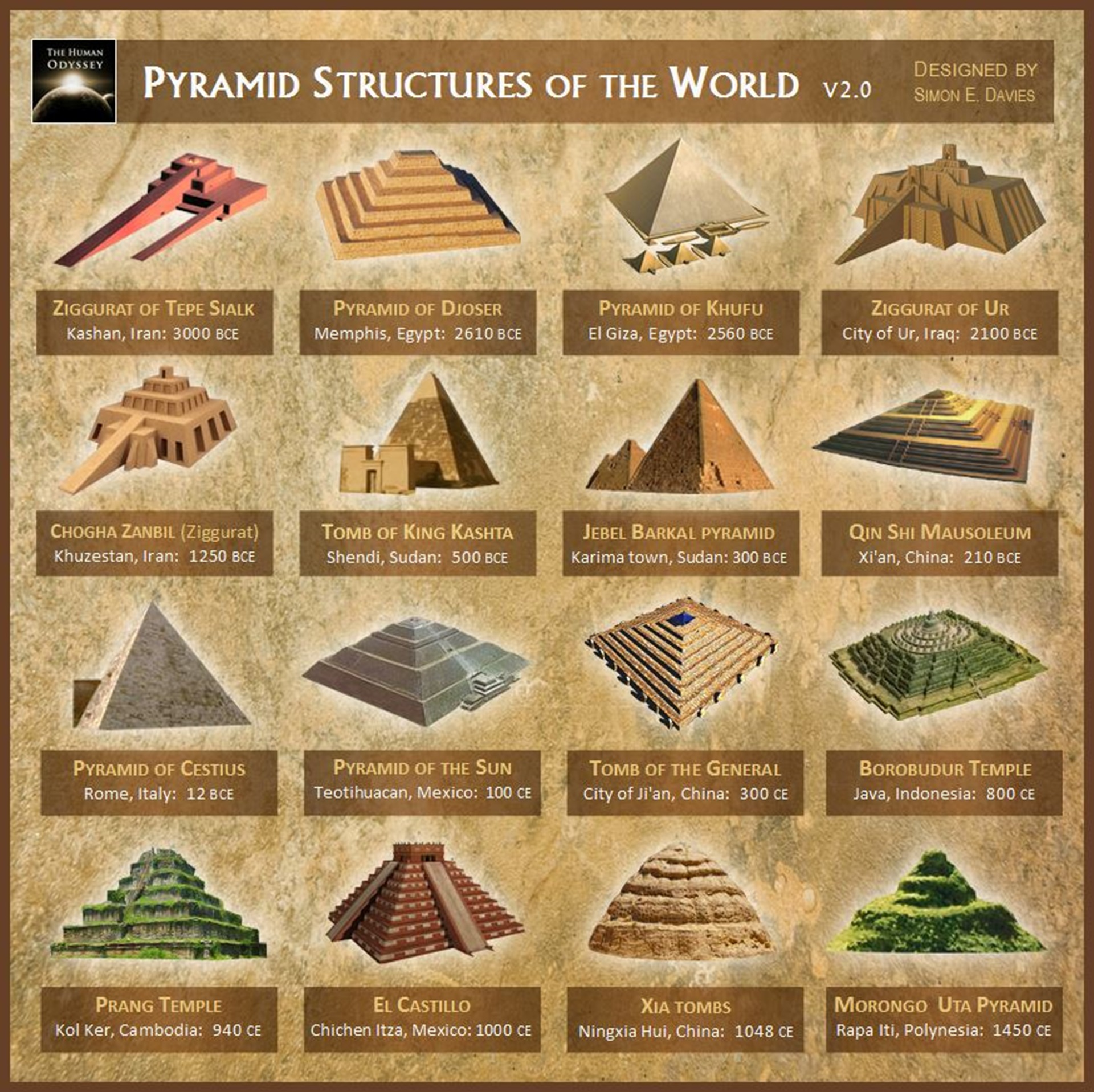

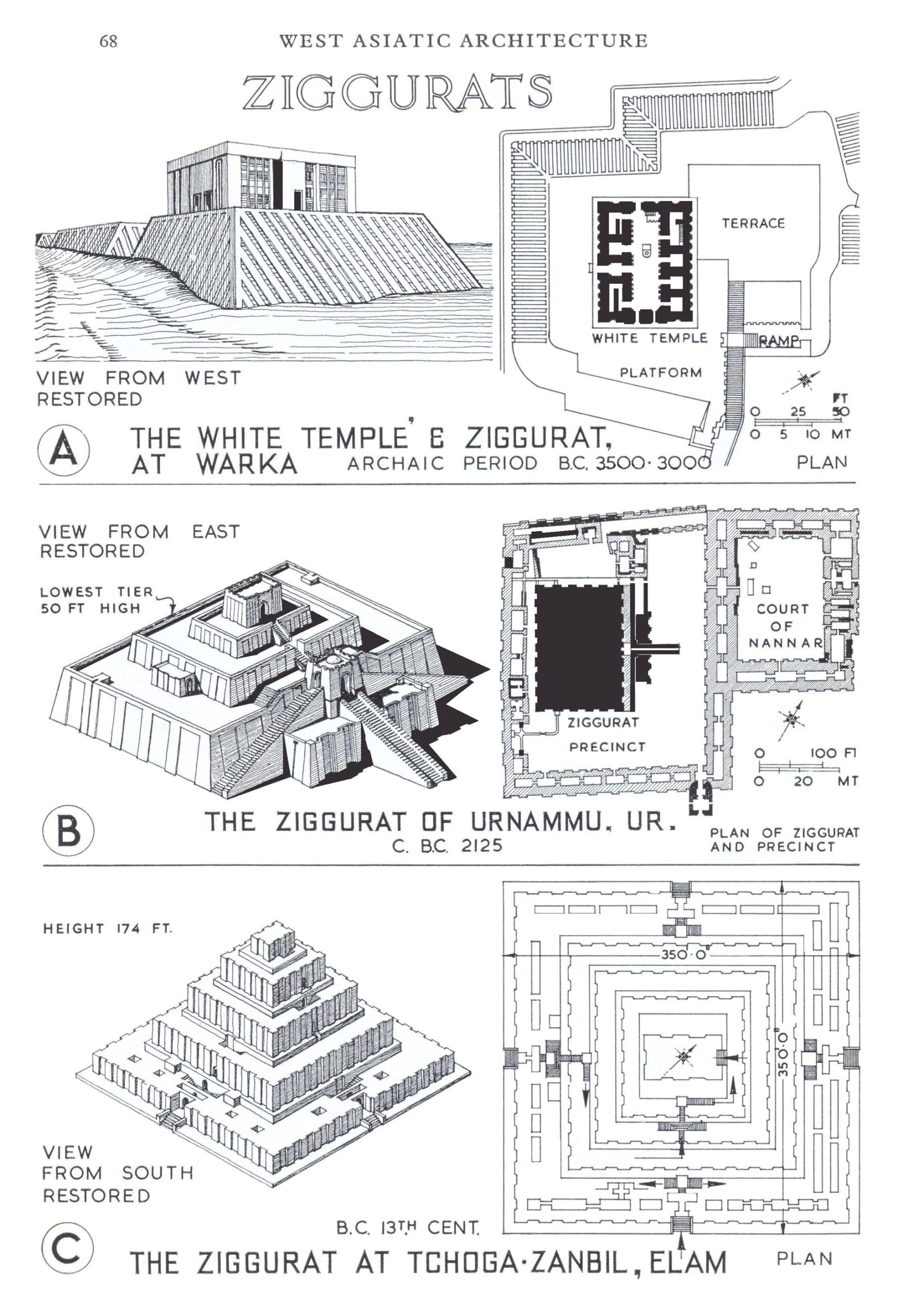

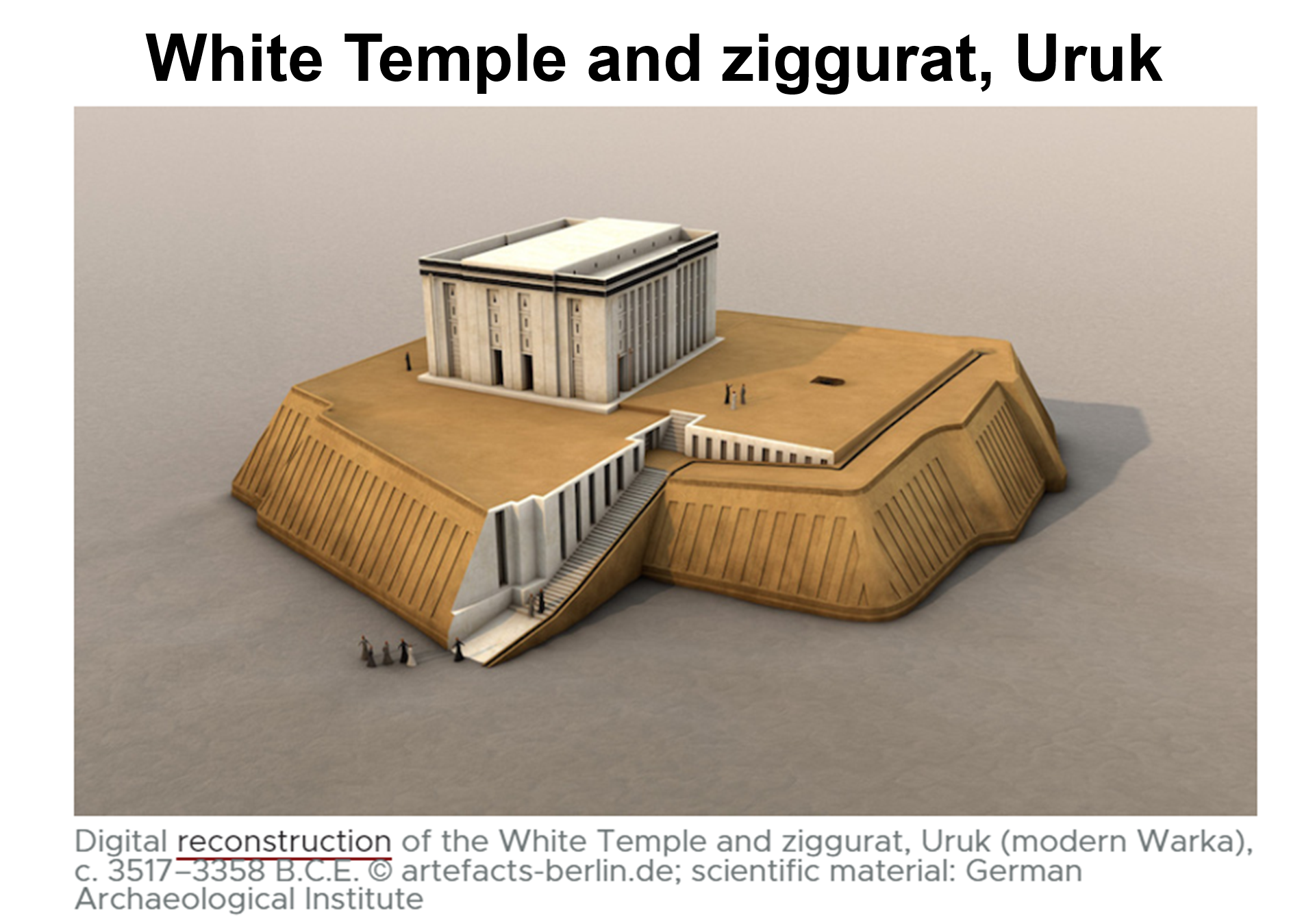

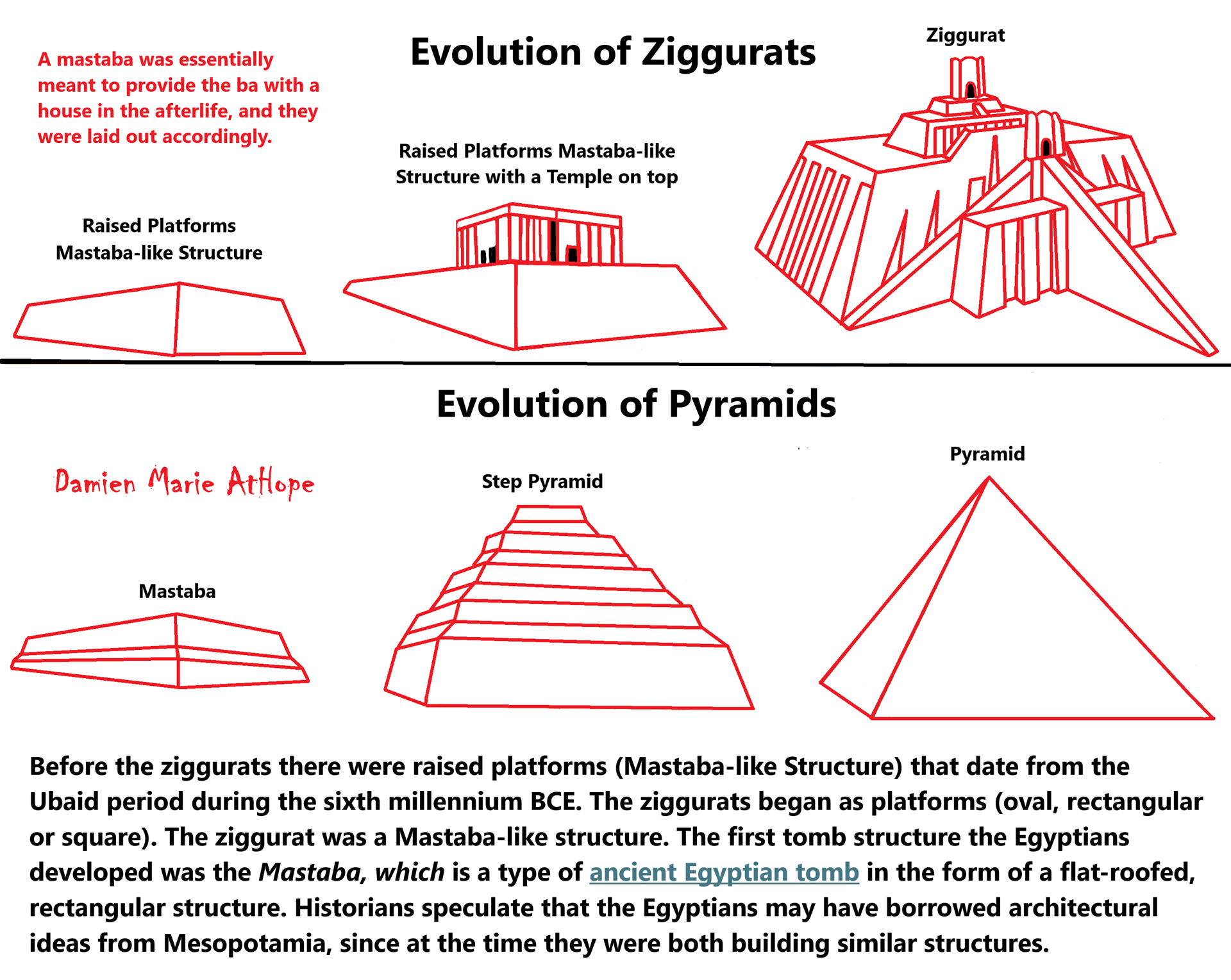

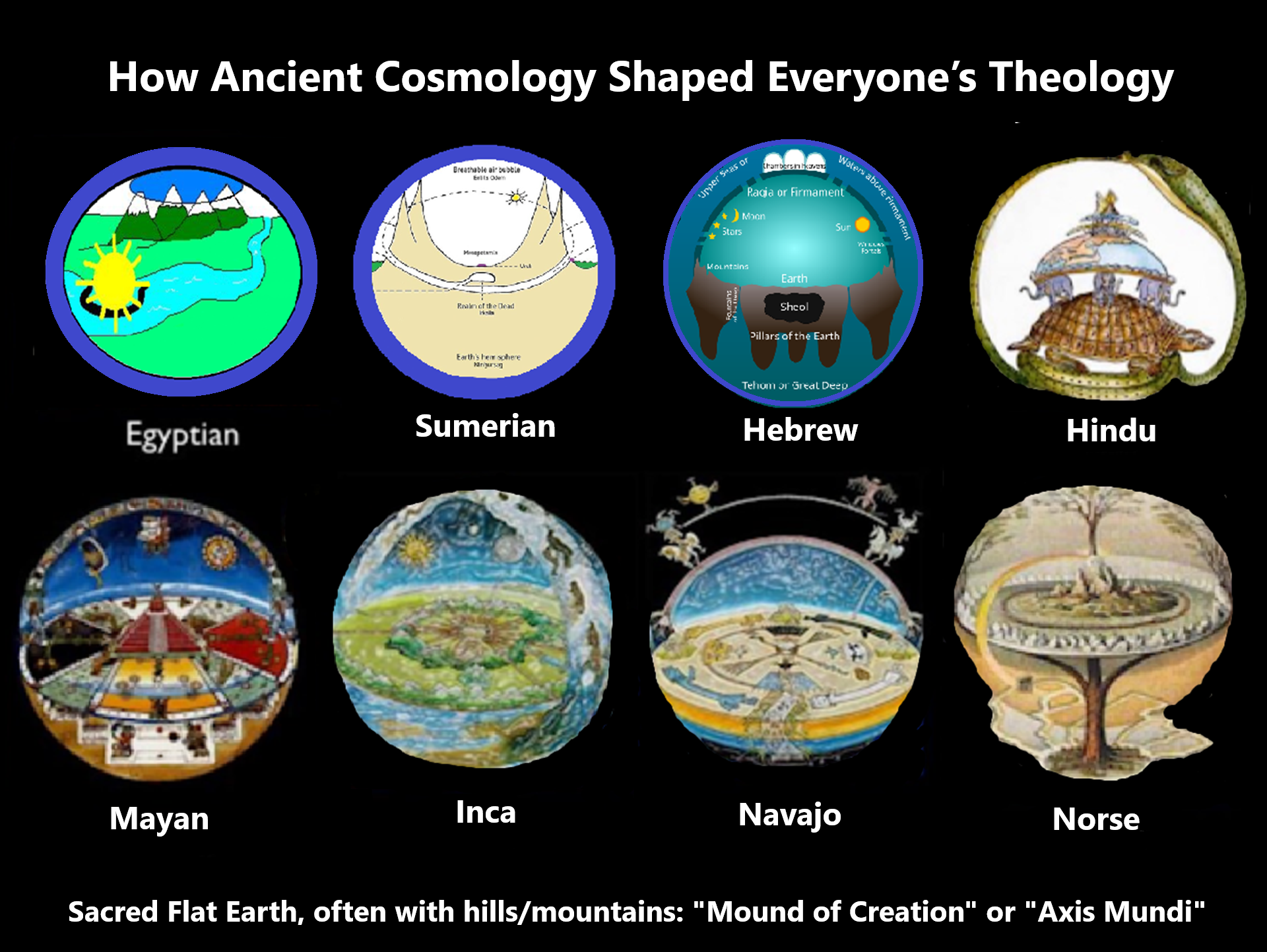

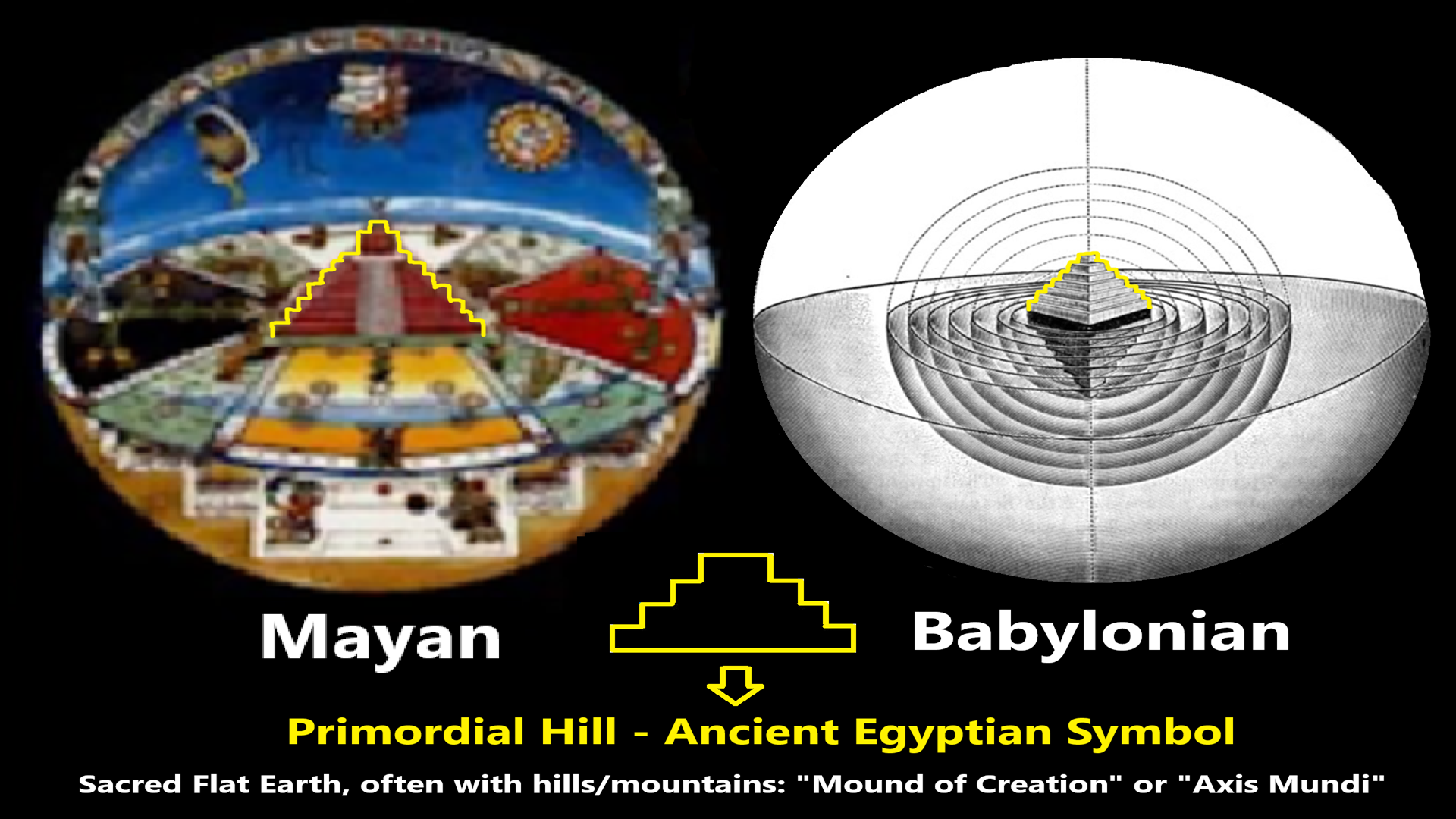

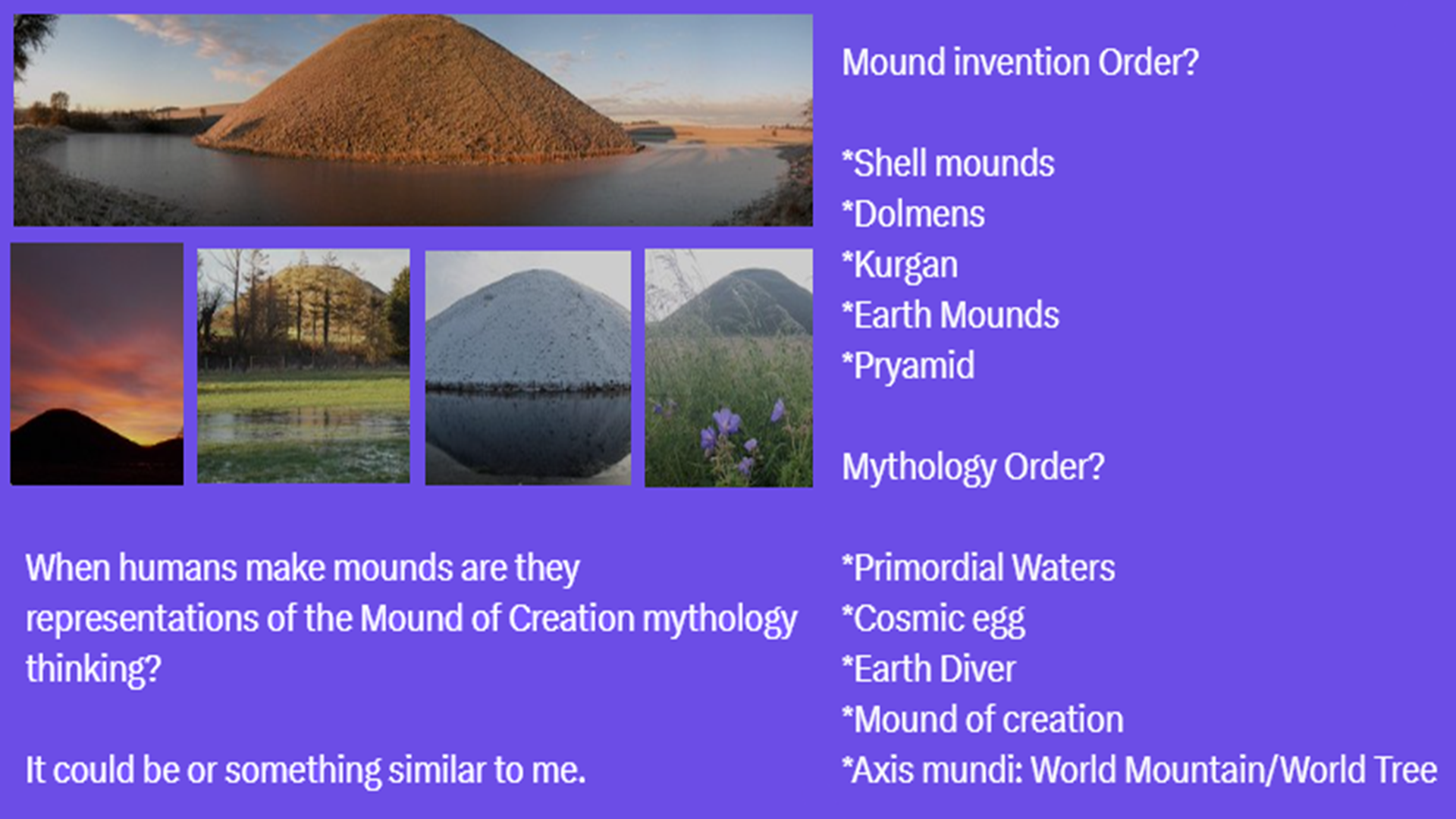

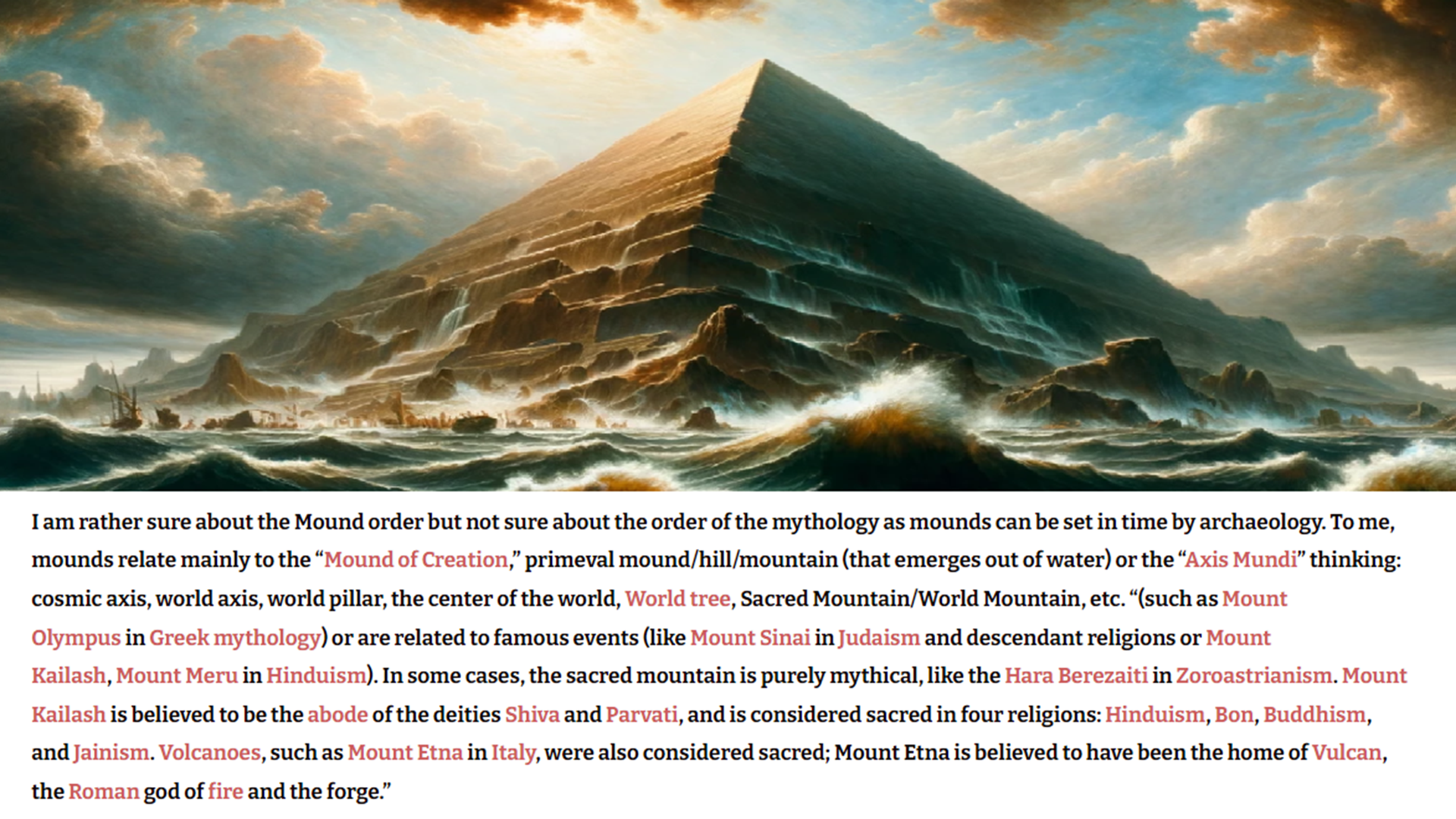

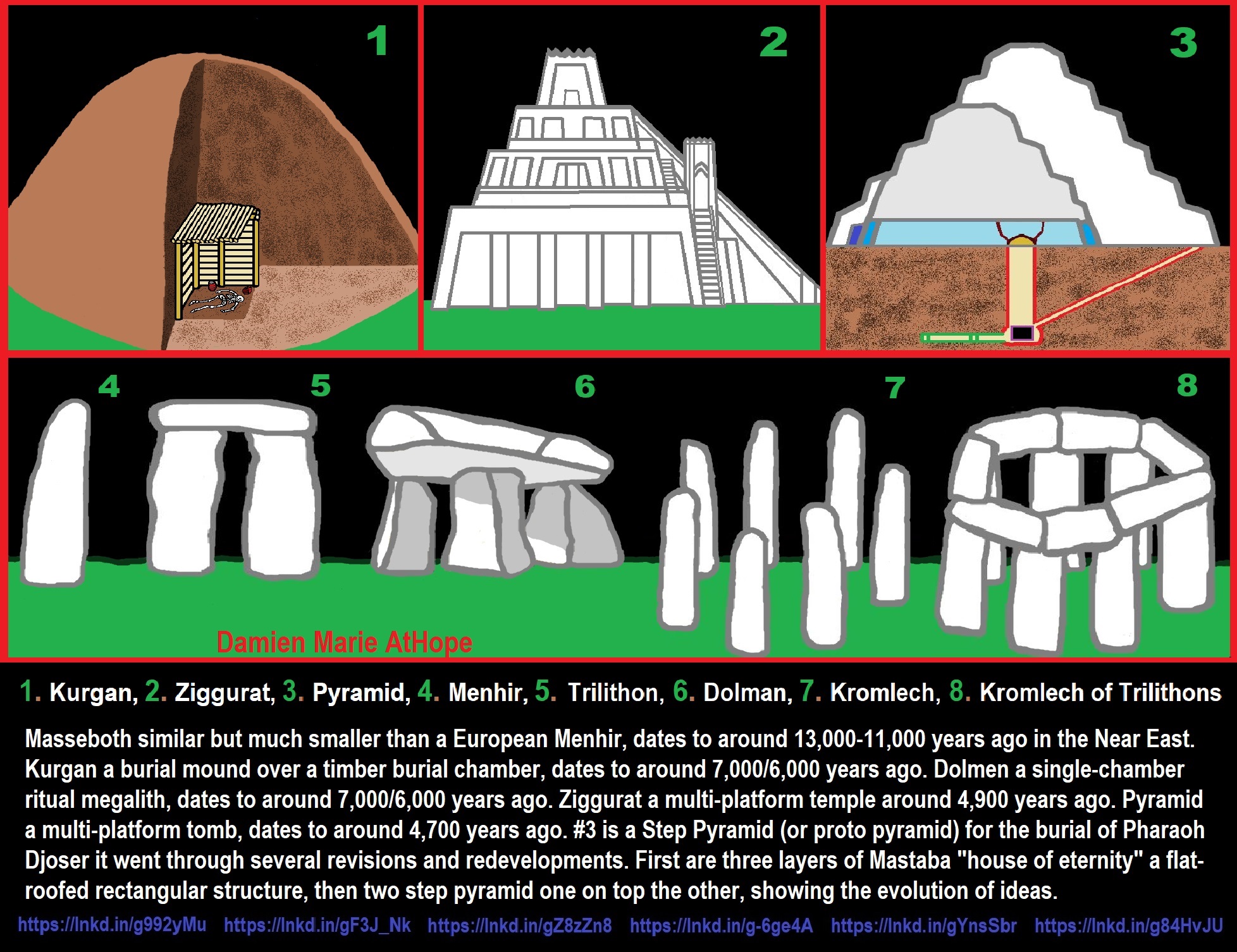

“Harsag/Hursag “mountain,” “hill,” can mean: (Mountain-House “Temple,” “Cosmic Mountain,” “Holy Mountain,” or “World Mountain”). The peak of the cosmic mountain is not only the highest point on earth, it is also the earth’s navel, the point where creation had its beginning” the very the root/Axis Mundi. And maybe identified with a real mountain, or it can be mythic, but it is aways placed at the center. Examples abound: the Mesopotamian ziggurat is properly called a cosmic mountain and is seen as “a mountain with a deity house.” ref

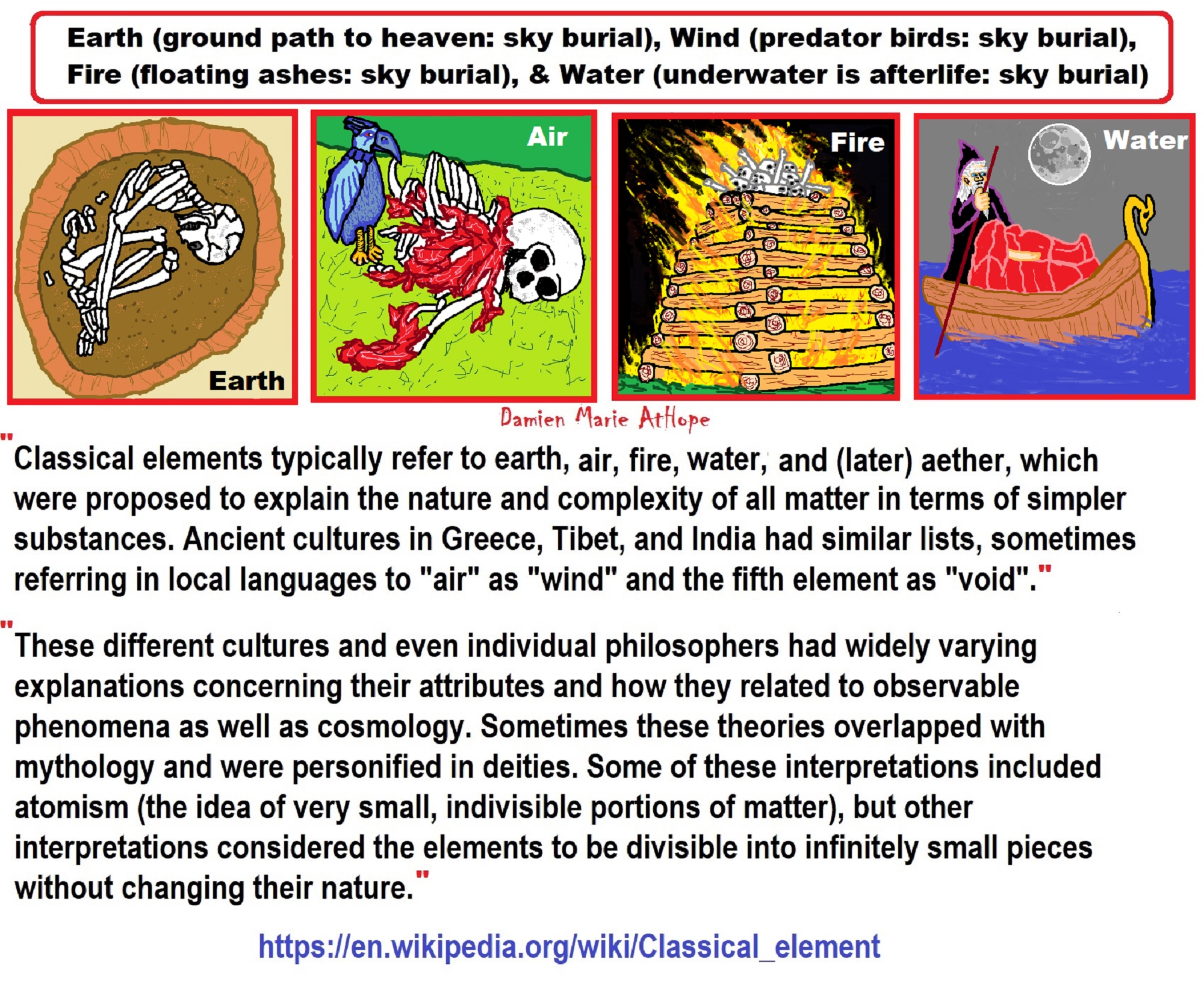

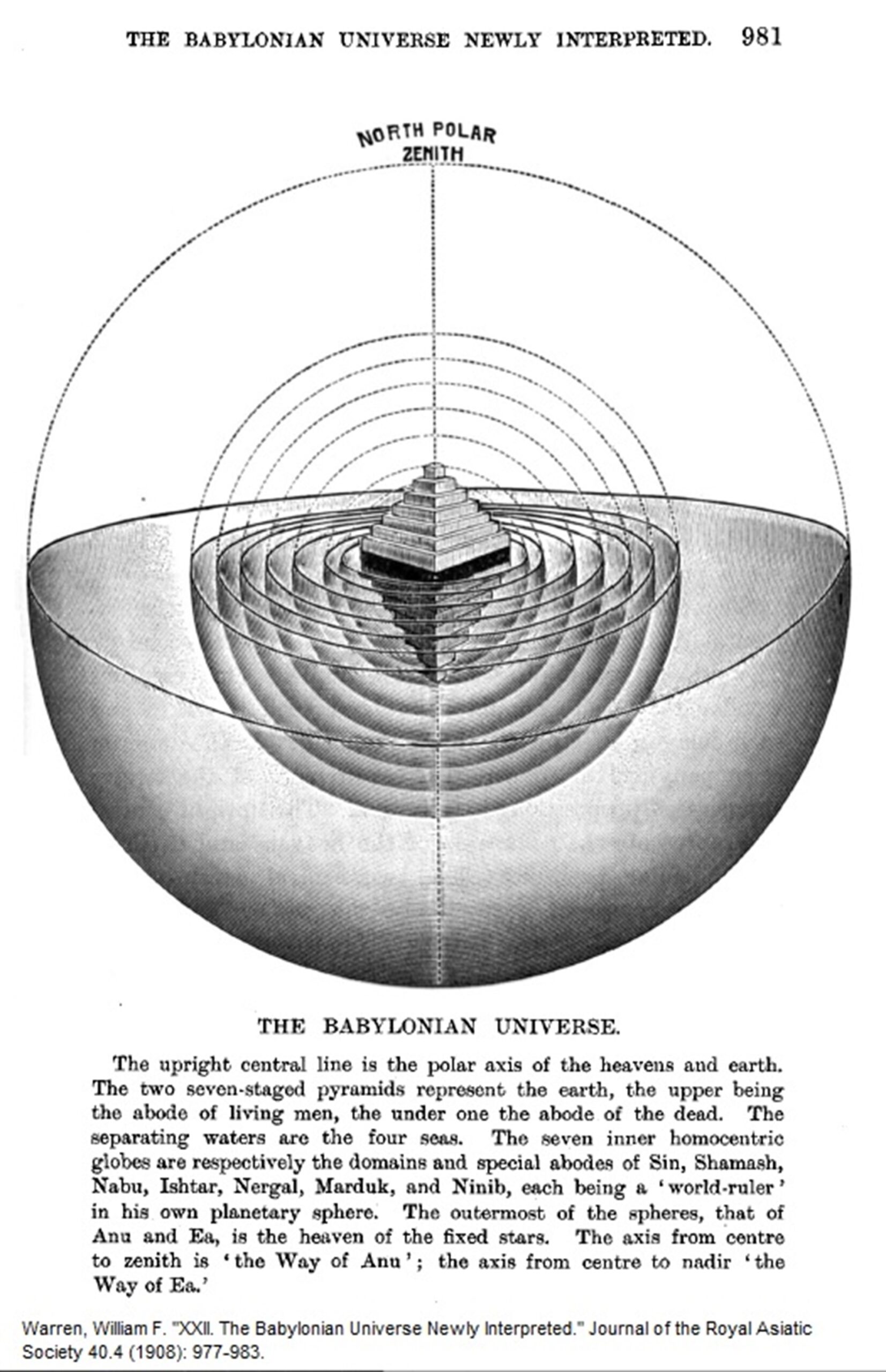

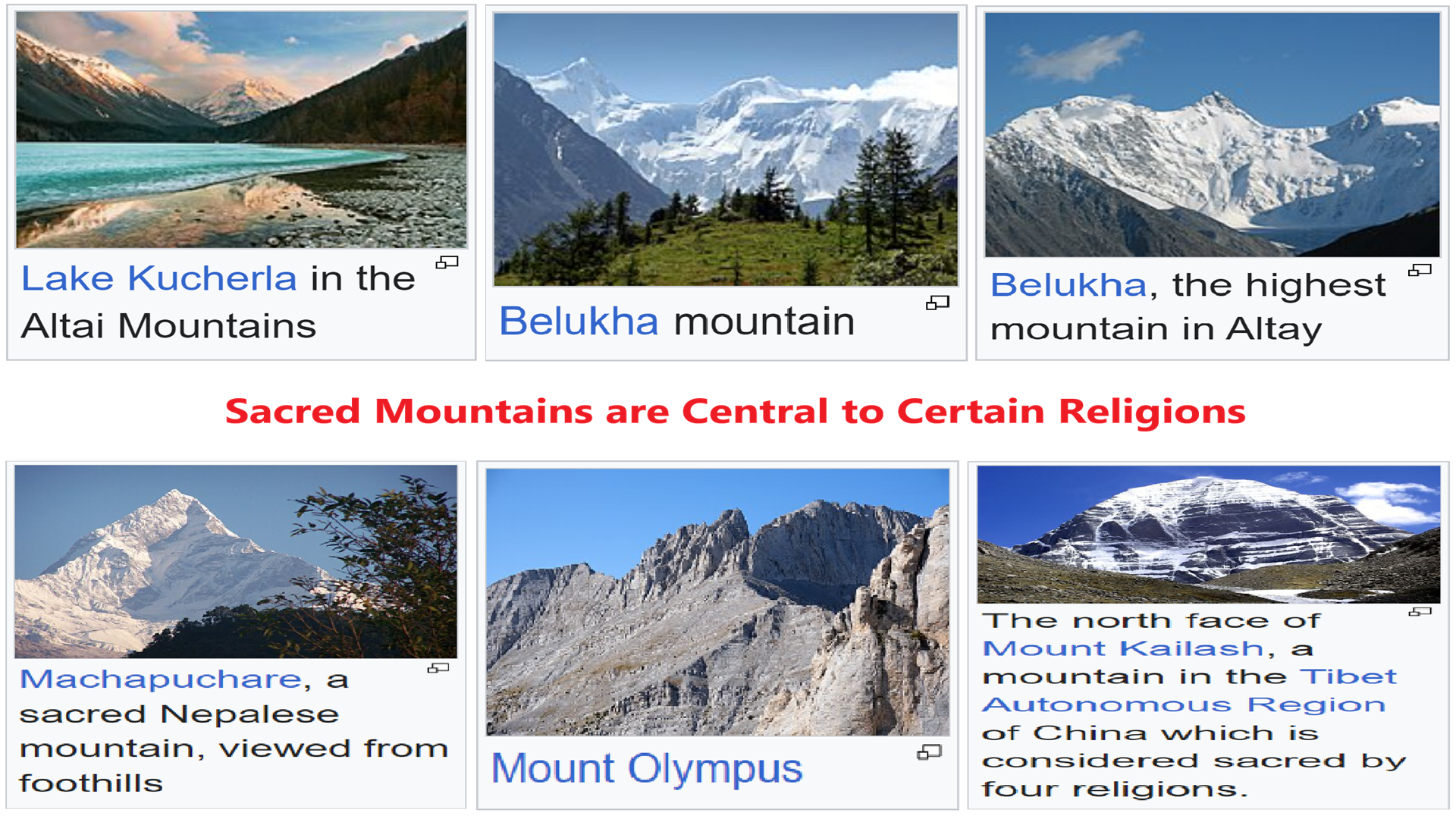

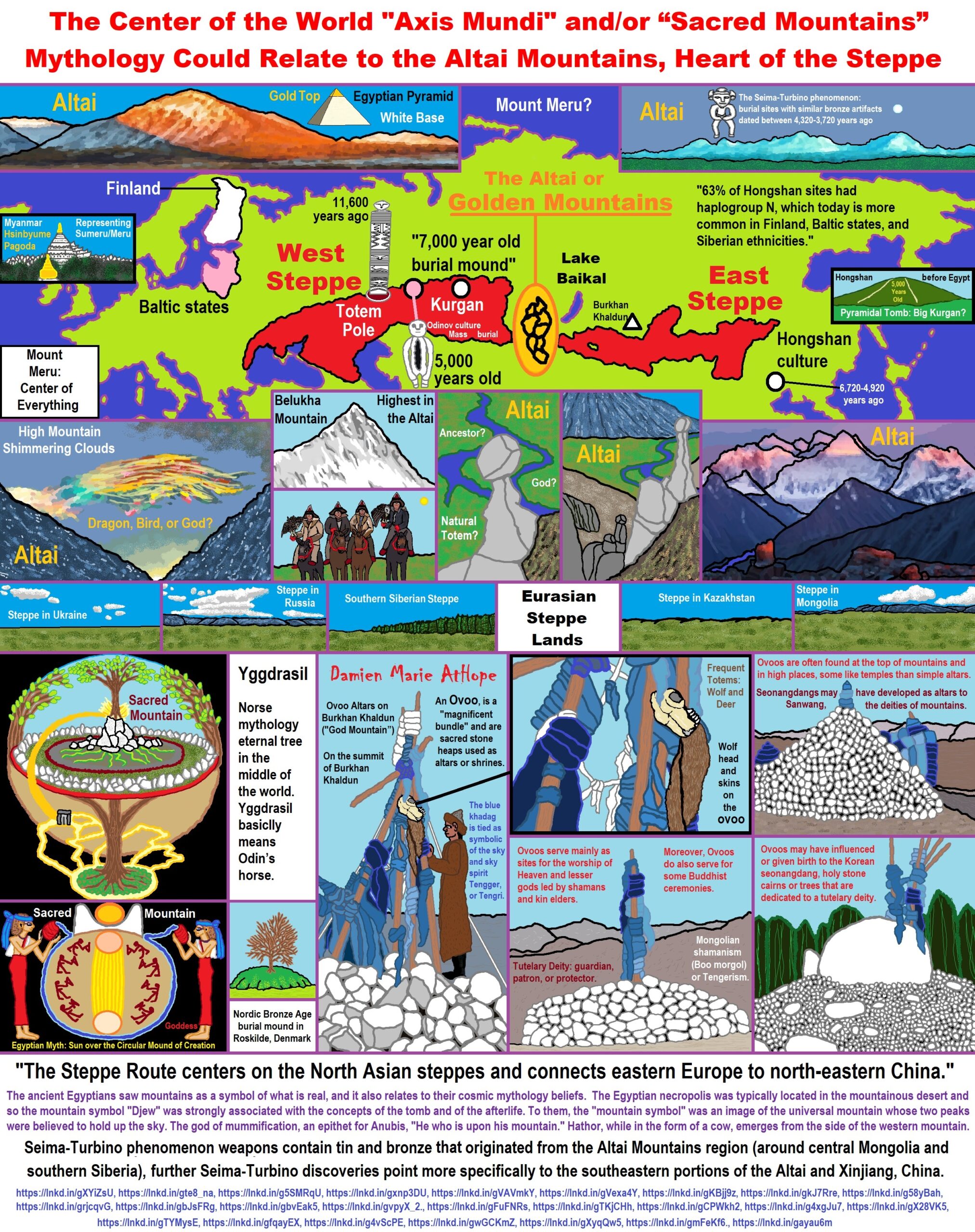

The concept of divine regulation of the world from a mountain venue was universal in ancient times. The scholar of comparative religion Mircea Eliade says that “the peak of the cosmic mountain is not only the highest point on earth, it is also the earth’s navel, the point where creation had its beginning” — the root. According to Eliade, “This cosmic mountain may be identified with a real mountain, or it can be mythic, but it is always placed at the center … Examples abound: the Mesopotamian ziggurat is properly called a cosmic mountain…” Richard J. Clifford prefers the term “cosmic mountain” to “sacred mountain.” The mention of “holy mountain” evokes mythological thoughts of the cosmic mountain that stands at the center of the world. This is the place where creation began, a point of contact between the human and divine worlds.” ref

“Peter Jensen’s landmark book Die Kosmologie der Babylonier [The Cosmology of the Babylonians] was published in Strassbourg in 1890. Jensen’s book attracted considerable attention among European Orientalists of the day, as he articulated a theory destined to become the foundation of a later school of thought concerning the” Weltberg” or “world-mountain.” His evidence was based on philological and archaeological material. In a seminal passage, Jensen homed in on the Sumerian word harsag (or hursag), found in passages describing temples. It often appears in the phrase I-harsag-kurkura, which Jensen translated as “Berghaus der Lander.” ref

“The term harsag, isolated from its contextual usage, only means Berghaus (mountain-house), and can best be translated as “temple.” There is thus a correlation made between temple and mountain. An image of a “cosmic mountain” figures prominently in religious practices throughout the ages and in attendant mythic narratives. The inaccessible mountain, stunning in its beauty yet elusive to all approach, is the most prevalent and compelling of all imaginary places recurring in cultural myth and private dream. The concept of the cosmic mountain was prevalent in different forms throughout the ancient Near East: from Mesopotamian and Ugaritic cultures, and as far as Egypt and Greece.” ref

“In Asia, one finds the elaborate religious symbolism of Mount Meru, the cosmic mountain whose complex symbolic meanings are put forth. This axis, providing an opening through the three planes, makes possible communication with the sacred. This world axis may be symbolically represented as a world pillar, a ladder, a cosmic mountain, a cosmic tree, and so forth. Mount Meru, the cosmic mountain, carried the hierarchy of beings. Under the name of one of its peaks as cosmic axis, Mandara, the mountain functioned in the Churning of the Ocean. For the mythic world of Asia, Meru is the cosmic mountain, rooted in the earth, with its top in the heavens. It is both the axial mountain and the ideal divine city, and it provides the pattern for the cities of the kings on earth.” ref

“When Hindu beliefs reached Cambodia, they merged with the religious aspect of Mount Mahendra with early Khmer rulers becoming identified as the earthly incarnations of the deities of this cosmic mountain. Similarly, in early Taoism, K’un-lun is a cosmic mountain paradise connecting heaven and earth. China has Five Sacred Mountains: Mount Tai, of the East; Mount Hua, of the West; Mount Heng, of the North; Mount Song, of the Centre; and Mount Heng, of the South. It also has Mount Kunlun, a Cosmic Mountain. The ancient Iranian mythological motif of the cosmic mountain at the edge of the world was incorporated early on into medieval Islamic cosmology, known as Mount Qaf.” ref

“The Tatars of the Altai imagine Bai Ulgan in the middle of the sky, seated on a golden mountain. The Abakan Tatars call it “The Iron Mountain”. In Iranian Sufism the mountain of visions is the psycho-cosmic mountain, the cosmic mountain seen as homologous to the human microcosm. It is the “Mountain of dawns” from whose summit the Chinvat Bridge springs forth to span the passage to the beyond. Images used in early Persian mysticism are of “emerald cities,” the “emerald rock” at the top of Qaf, the cosmic mountain (also called Alburz). East Kalmuck people in Siberia believe the world is centered on a great cosmic mountain they call Sumer. Its truncated summit is represented by the square in the middle of this picture they draw of their world.” ref

“According to scholars of the history of religion, people of widely differing cultures have believed that there is a world axis located at the center of the earth, which is marked by a cosmic mountain. Throughout Indian Asia the mythical cosmic mount Meru at the center of the universe was thought to be the axis mundi. In Sumeria the primeval sea begot the cosmic mountain consisting of heaven and earth united. It is said that the gods grasped this cosmic mountain, the axis of the world, and used it to stir the primordial ocean, thus giving birth to the universe. The cosmic mountain not only was the origin of the earth, but also came to function as the peg which secured the earth a firm support. The Center of the World is represented by the image of the Cosmic Mountain, seen also as a connecting axis.” ref

“The Cosmic Mountain, the World Tree, or the central Pillar, which sustains the planes of the Cosmos. For shamans, the connection between the seen (physical) and the unseen (spiritual) worlds, the axis mundi, is most often visualized as a great cosmic tree connecting all of the Kosmos. This cosmic tree, which functions like the cosmic mountain, is thought to make it possible for the two or three levels of the universe to communicate. Sometimes, it holds up the sky, and it plays an important role in shamanism.” ref

“The metaphorical picture is that of a huge tree atop a cosmic mountain whose height reaches heaven, whose branches encompass the earth, and whose roots sink down to the lowest parts of the earth. Both the sacred mountain and the cosmic tree are emblems of stability, and, like the top of the World Tree, the summit of the cosmic mountain is always said to be the highest place on earth. Sitting atop the cosmic mountain, one climbs the cosmic tree to reach the heavenly abode. The mountain and tree form the axis that connects the three worlds — the underworld, the earth, and the heavens.” ref

“The focal point of the cosmic motif in biblical imagery is often as not the cosmic mountain, undoubtedly because of the Sinai event. The cosmic tree rarely, if ever, appears apart from its mountainous base. Within the magic ring of myth, the cosmic mountain is preeminent, both for its universality and its spiritual resonance as the meeting – place of heaven, earth, and hell and the axle of the revolving firmament. Unlike man-made sanctuaries, Sinai was created by Yahweh — it was the temple established not by humans but by divine hands. It was the sanctuary that served as a model for all replicas, especially the Tabernacle and the temple in Jerusalem.” ref

“For the Bible, cosmic mountain imagery is also a backdrop against which to see the special relationship between Israel and her own mountains expressed in national mountain imagery. Many of the salient features of the cosmic mountain known from foreign sources appear in the religion of biblical Israel in connection with Mount Zion. The Hebrew Scriptures contain clear allusions to the Ancient Near Eastern notion of mountains as the dwelling places of deities or the place where the gods assemble. Zaphon is the name of the cosmic mountain where El and Baal exercised their kingship. Zaphon (Heb. sapôn) designates “north” and is the cosmic mountain par excellence.” ref

“The motif of rivers flowing from the cosmic mountain as a source of life has been incorporated into Hebrew literature. The Cosmic Mountain The “very high mountain” mentioned in Ezekiel 40:2, to which Ezekiel is transported at the beginning of his vision in chapters 40–48, is at once Mount Zion and the cosmic mountain, the center of the creation. To Christians, Golgotha is the center of the world, for it is the peak of the cosmic mountain and the spot where Adam was created and buried. In the beginning of his Apocalyptic vision, John is in the spiritual degree; but after he has experienced or realized in his upward march the realities of the Lamb’s book of life, he takes his place in the celestial mountain.” ref

“In Syro-Palestine, the temple was the architectural embodiment of the cosmic mountain. The primary element of a sanctuary was the bamah, the ‘high place’, the local counterpart of the cosmic mountain on which the Deity was conceived as dwelling and where he sat enthroned as cosmic king. Jerusalem was fully established as the new Sinai, a cosmic mountain and source of order. The order of Eden, restored in historical times by the covenant at Sinai, was the present and future blessing of Jerusalem. The temple of Solomon would seem ultimately to be a replica of the holy, cosmic mountain of religious literature, replicating the heavenly mountain of YHWH at Mt. Horeb/Sinai. The Jerusalem of Solomon has been characterized by Michael Fishbane as “the new Sinai, a cosmic mountain and . . . source of order.” ref

“For the Cherokee, the “world” is their world, and at its center is the Cosmic Mountain, stated above to be the axis. Their council house was consequently modeled after the Cosmic Mountain. Most ancient cultures have their standing stones, megaliths, pyramids, and obelisks. The cosmic mountain is such an important image that it has been the basis of sacred buildings. The direct antecedent of all Buddhist stupas was a cairn; and in the Sumerian myth a cairn is a summary representation of the cosmic mountain erected on the body of the anthropomorphic personation of the Mountain. Temple towers functioned as a representation of the cosmic mountain. A stupa may also suggest the stylized representation of a mountain.” ref

“These temple mountains were not uncommon in various parts of the world – for instance, the Ziggurat at Ur of the Chaldees, and Borobudur in Java. The Central Javanese complexes give the impression of being self-centered and complete in themselves as replicas of the cosmos (the cosmic mountain). As the cosmic mountain, Meru is imitated and repeated architecturally in Hindu temples, with sbikbaras, or “mountain peaks,” rising toward the heavens. It is repeated as the center post of Buddhist stupas. Though there is a common symbolism with the Brahmanic Mount Meru, the stupa is more than simply an architectural imitation of this cosmic mountain: it becomes, in its own right, the cosmic mountain. The cult of Balinese water temples embellishes the cosmic-mountain symbolism by emphasizing the role of the volcanic crater lakes as the symbolic origin of water, with its life-giving and purificatory powers.” ref

“The Shiva linga, like the Sri Chakra, is a symbol of the cosmic mountain. The three-dimensional form of the Sri Chakra is also a Shiva linga. The Iron Pillar, as the World Tree or Pillar (skambhd), surmounted by Visnu’s standard (dhvajd), is rooted in the Cosmic Mountain, which, as “Visnu’s place,” is the highest heaven. In Cambodia the linga appears, as a rule, associated with the symbolism of the cosmic mountain. At one time, there was a relationship between the temple, representing the cosmic mountain, and the essence of royal power, which was venerated.” ref

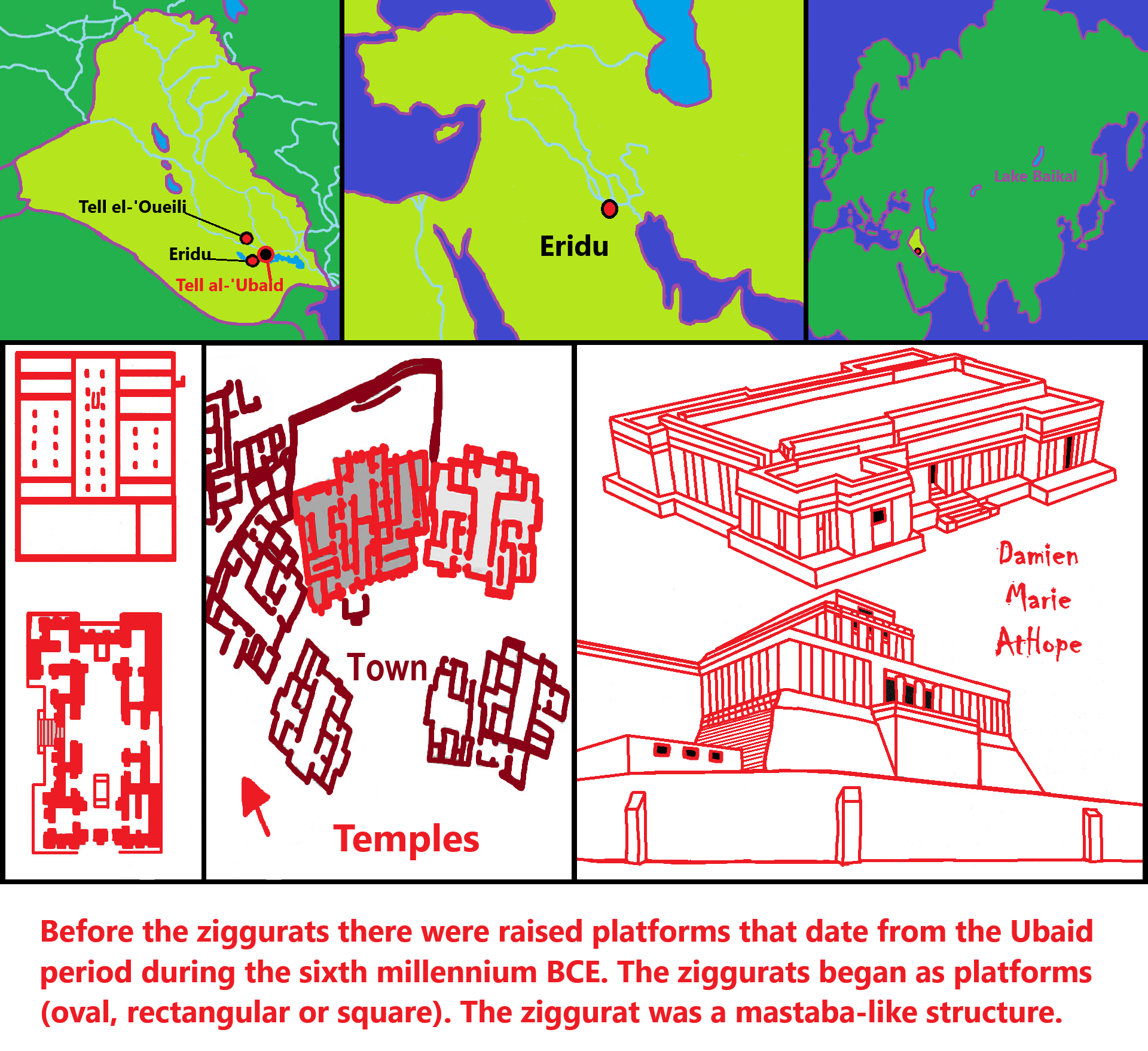

“In Mesopotamia, the temple could represent the cosmic mountain. Mesopotamian seals represent a god emerging from the cosmic mountain, supporting the interpretation of the ziggurat as the cosmic mountain, symbolic of the earth itself. Properly speaking, the ziggurat was a cosmic mountain, ie, a symbolic image of the cosmos. Religions attempted to build their sanctuaries on prominent heights. Since no such natural heights were available in the flat flood plains of Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), ancient priests and kings determined to build ziggurats, square or rectangular artificial stepped temple platforms. Functionally, temples were placed on raised platforms to give them prominence over other buildings in a city, and to allow more people to watch the services performed at the temple.” ref

“Symbolically, however, the ziggurat represents the cosmic mountain on which the gods dwell. The priest’s ascent up the stairway to the temple at the top of the ziggurat represents the ascent to heaven. The great ziggurat at Khorsabad, for example, had seven different stages; each was painted a different color and represented the five known planets, the moon, and the sun. The names of the Babylonian temples and sacred towers themselves testify to their assimilation to the cosmic mountain. The ziggurat at Til Barsip was called ” the house of the seven directions of heaven and earth.” Important temples were built on a terraced base, recalling all the more the image of the cosmic mountain, formed by diverse levels of existence and crowned with the residences of divinities and the supreme god.” ref

“These cities, temples, or palaces, regarded as Centers of the World, are all only replicas, repeating ad libitum the same archaic image — the Cosmic Mountain. The initial stone that is placed, the foundation or cornerstone, mystically represents the peak of the cosmic mountain breaking the surface of the primordial waters before rising to fill the heavens and earth. Potentates in lands influenced by Indian culture raised models in miniature of the Cosmic Mountain, on the possession of which they based claims to universal dominion. Eliade argued that the Chinese capital was perceived along similar lines — as an axis mundi, or a symbolic cosmic mountain: “In China, the capital of the perfect sovereign stood at the exact center of the universe…” The Hollow Mulberry is a cosmic mountain and it is also identified with the Yellow Emperor.” ref

Aztec temples were the axis mundi of the cosmic tree/cosmic mountain, which provided abundant “hearts” or animistic powers for agriculture. Mesoamerican parallels forcefully assert that the Teotihuacanos erected their tree, their axis mundi, in close proximity to the north house in the Plaza of the Moon near the cosmic mountain filled with life-sustaining water. Mythic cities, temples, or palaces, regarded as Centers of the World, are all only replicas, representing ad libitum the same archaic image — the Cosmic Mountain, the World Tree, or the central Pillar, which sustains the planes of the universe. The cosmic mountain of Kaf/Qaf in Sufism has significance beyond merely topographical detail.” ref

“That mountain-climbing for Rushdie, Dante, and ‘Attar possesses some symbolic significance is evident. It involves guidance in climbing the cosmic mountain and even flying beyond it, transcending the ordinary human state. The ascent of a mountain is viewed symbolically by the Chinese as a creative move upward, and the Taoist’s cosmic mountain (K’un Lun, the Abode of the Taoist Immortals) was considered the highest point on earth. The Cosmic Mountain allows the seer a vantage point of all- seeing; and its ascent is associated with loftiness. Cosmic mountain, cosmic waters, and sanctuary — this is the language of the sacred. Existing at the very heart of Creation, yet paradoxically everywhere, the archetypal Cosmic Mountain provides a crystal-clear yet constantly spiraling path to the Absolute.” ref

“Frank Korom writes, “lf we accept the contemporary criticisms, interpretations, and exegesis that has resulted from more sufficient evidence based on ever-increasing sources of information and documentation, then we must seriously question the use of axis mundi as a universal mythological concept. What began as a potentially useful analytic model for the study of a specific culture over a century ago has been transformed into a phenomenological ideal type grounded in an inaccurate original hypothesis, and scanty worldwide empirical evidence.” ref

“Hursag (Sumerian: 𒄯𒊕 ḫar.sag̃, ḫarsang) is a Sumerian term variously translated as meaning “mountain,” “hill,” “foothills,” or “piedmont.” Thorkild Jacobsen extrapolated the translation in his later career to mean literally, “head of the valleys.” Mountains play a certain role in Mesopotamian mythology and Assyro-Babylonian religion, associated with deities such as Anu, Enlil, Enki and Ninhursag. Hursag is the first word written on tablets found at the ancient Sumerian city of Nippur, dating to the third millennium BCE, Making it possibly the oldest surviving written word in the world. Some scholars also identify the hursag with an undefined mountain range or strip of raised land outside the plain of Mesopotamia.” ref

“Eḫursag is a Sumerian term meaning “house of the mountains,” sometimes etymologized as É.ḪAR.SAG with the signs É “temple” (or “house”), ḪAR “mountain” and SAG “head”. Eḫursag (Sumerian: 𒂍𒄯𒊕) is a Sumerian term meaning “house of the mountains”. Sumerian ÉḪURSAG is written as a special ligature (ÉPAxGÍN 𒂍𒉺𒂅), sometimes etymologized as É.ḪAR.SAG (𒂍𒄯𒊕), written with the signs É “temple” (or “house”), ḪAR “mountain” and SAG “head.” ref

“Ehursag is commonly associated with a temple of Enlil discovered by Sir. Charles Leonard Woolley during excavations at Ur in modern-day Iraq. He originally considered this to be a palace, a view that was later rejected in replace for a temple. The location of the royal palace at Ur remains unknown. No graves were discovered under the Ekursag during these excavations. Woolley eventually conceded that it was a “minor temple of some sort.” Modern scholars still vary on their interpretations of it as a temple, palace, or administrative building. It has even been suggested to be a wing or annex of the main temple, having had some of its foundations destroyed.” ref

“Stamped bricks used in the construction of the foundations revealed that they were built by Ur-Nammu of the Third Dynasty of Ur. Bricks from the pavement bore the stamp of his successor, Shulgi, and later ones of the Isin–Larsa period after Ur was destroyed by Elamites. Ehursag is also the name or epithet of Ninhursag‘s temple at Hiza and has been suggested to have been an interchangeable word with Enamtila. The Ehursag at Ur was restored in 1961 using ancient and modern bricks, a 2008 report for the British Museum noted that this had collapsed in some areas, especially the northwest corner.” ref

“Anunit – Mesopotamian mother or creator goddess derived from the earlier Sumerian Ki. She was Anu’s consort. Also known as Antu.

E-barra – Temple of the Sun.

E-gal-mach – Temple.

E-kur – Heaven.

E-mach – (Great Gate). Temple.

E-me-te-ursag – The temple of the War God, Zamama.

E-mish-mish – Temple.

Eridu – One of the most sacred cities of Mesopotamia. It was the resedence of the God Enki.

E-sagil – The “Temple that raises its head.”.The temple of Marduk in Babaylon.

E-shidlam – Temple.

E-ud-gal-gal – Temple.

Harsag-kalama – Temple. Possibly located in Ur (Ekhursag).” ref

The Tale of Inanna and Ebih: A Story of Honor and Might

“In the myth of Inanna and Ebih, An warned Inanna about the dangers of the mountain. He described Ebih’s thick forests, fierce lions, and wild bulls. An knew the mountain’s formidable nature. He cautioned Inanna, hoping to deter her from the perilous journey. These mountains were rugged and wild, home to fierce tribes and untamed nature. For the Sumerians, the Lulubi Mountains were a place of both awe and fear. Inanna’s journey took her through several regions, including Elam, Subir, and the Lulubi Mountains, culminating in a fierce confrontation with Mount Ebih. Each place she visited held great significance to the Sumerians.” ref

The Lulubi Mountains: Gateway to the Wild

“The Lulubi Mountains were within the Zagros range, now on the border between Iraq and Iran. These mountains were rugged and wild, home to fierce tribes and untamed nature. For the Sumerians, the Lulubi Mountains were a place of both awe and fear. Inanna’s passage through these mountains highlighted her bravery and her determination to conquer all obstacles in her path.” ref

Mount Ebih: The Ultimate Challenge

“Mount Ebih, known today as Jabal Hamrin, is a mountain ridge on the western side of the Zagros Mountains. To the Sumerians, this mountain was more than just a physical obstacle; it was a symbol of defiance and pride. Samuel Noah Cramer, the scholar and expert in Sumerian history, likened it to the Dragon Kur, an ancient beast that represented chaos and resistance. Inanna’s confrontation with Mount Ebih was not just a battle with a mountain but a fight against a force that refused to acknowledge her divine power. Inanna’s journey culminated in a fierce confrontation with Mount Ebih. Despite Inanna’s power and might the mountain refused to show her respect and bow down to her. And hence the myth of Inanna and Ebih was born.” ref

The Myth: Inanna and Ebih

“Inanna, the goddess of fearsome power, rode into battle, wrapped in terror. Armed with the holy a-an-kar weapon, she was drenched in blood. Her shield rested on the ground as storms and floods surrounded her. Inanna, the great lady, was a master of conflict. With her arrows and strength, she destroyed mighty lands and overpowered enemies. In the heavens and on earth, Inanna roared like a lion, causing devastation. She triumphed over hostile lands like a wild bull. With the ferocity of a lion, she subdued the rebellious and the defiant.” ref

“Inanna grew to the stature of the heavens. She became as magnificent as the earth. She appeared like Utu, the sun god, stretching her arms wide. Inanna walked in the heavens, cloaked in terror, and on earth, she wore daylight and brilliance. In the mountain ranges, she brought forth beaming rays. She bathed the mountain plants in light and gave birth to the bright mountain, the holy place. Strong with her mace, she was joyful and eager in battle, a destructive force. The people sang her praises, and all lands celebrated her.” ref

Inanna’s Declaration of Vengeance

“Inanna, the goddess of love and war, spoke with fiery determination. “When I, the goddess, walked in heaven and on earth, I roamed through Elam and Subir. I traveled in the Lulubi Mountains. As I approached the heart of the mountains, I saw that the mountain Ebih showed me no respect. It did not bow to me. It did not fear me.” She continued, her voice filled with resolve. “Since it did not honor me, I will teach it fear. I will fill my hand with the mountain range and make it tremble. Against its mighty sides, I will place my battering rams. I will storm it and begin the sacred game of Inanna. In the mountains, I will start battles and prepare for war.” ref

“Inanna’s eyes gleamed with fierce intent. “I will prepare arrows in my quiver. I will polish my lance and ready my shield. Then, I will set fire to its thick forests and chop down its evil deeds with my axe. I will summon Gibil, the mighty god of fire, the purifier, to cleanse its waters. I will spread terror through the unreachable mountains of Aratta.” Her final words echoed with power. “Like a city cursed by An, it will never be restored. Like a place frowned upon by Enlil, it will never lift its head again. The mountain will witness my might. Ebih will give me honor and praise.” ref

“You placed me at the king’s right hand to destroy rebel lands. May he, with my aid, crush enemies like a falcon in the mountains.” Inanna declared, “May he destroy lands like a snake in a crevice. May he make them slither like a snake from the mountain. Let him know the mountain’s length and depth through the holy campaign of An. I strive to surpass the other deities.” “When I roamed the heavens and walked upon the earth, I traveled through Elam and Subir. I wandered in the Lulubi Mountains. As I turned towards the heart of the mountains, I approached the mountain Ebih. But Ebih did not bow to me. It showed me no respect. As I, Inanna, came near, the mountain refused to honor me. It did not fear my presence.” ref

“With a fierce resolve, Inanna asked, “How can the mountain not fear me? How can Ebih not fear Inanna, the goddess of heaven and earth? Since it did not bow down, I will make it learn to fear.” I will spread terror through the mountains of Aratta.” Inanna’s voice echoed with power, “Like a city cursed by An, may it never be restored. Like a city frowned upon by Enlil, may it never rise again. Let the mountain see my might. Let Ebih honor and praise me.” The powerful mountain Ebih, resembling a mighty dragon, reaches to the heavens with lush gardens, magnificent trees, and abundant wildlife, capturing its fearsome and overwhelming nature.” ref

An’s Warning and Inanna’s Fury

An, the king of the gods, answered her with concern. “My little one, you seek to destroy this mountain. Do you know what you are taking on? This mountain has spread fear among the gods. It has cast terror over the holy dwellings of the Anunnaki deities. Its presence weighs heavily on the land and stretches arrogantly to the center of heaven.” An continued, painting a vivid picture of the mountain’s splendor and danger. “Its gardens are lush, filled with hanging fruit. Magnificent trees rise like crowns to the heavens. Lions roam under the canopy of trees, and wild rams and stags abound. Wild bulls graze in flourishing grass. Deer couple among the cypress trees. Its fearsome nature is overwhelming. Inanna, you cannot pass through it.” Determined and unyielding, Inanna stormed out, ready to face the mountain. She would not be deterred. The battle was hers to win.” ref

The Battle Against Ebih

“Inanna stood before the mighty mountain, her gaze fierce and unyielding. She advanced, step by determined step, her dagger gleaming in the dim light. She sharpened both edges, preparing for the battle to come. With a swift, powerful move, she grabbed Ebih’s neck, her strength like a force of nature. She plunged the dagger deep into the mountain’s core, her roar echoing like thunder across the land. Ebih, the proud mountain, fought back fiercely. Rocks tumbled down its sides, clattering and shaking the ground. From its crevices, venomous serpents spat their poison, hissing in defiance. But Inanna’s wrath was unstoppable. She cursed the forests, damning the trees to wither and die. The mighty oak trees succumbed to her drought, their leaves turning to dust.” ref

“Inanna’s assault was relentless. She poured fire onto the mountain’s flanks, thick smoke rising to choke the sky. The flames consumed everything in their path, leaving nothing but ash. The mountain’s resistance was fierce, but Inanna’s power was greater. She established her authority over Ebih, bending it to her will. Inanna’s authority over the mountain was undeniable. She conquered it completely, bending it to her will. Holy Inanna, the fierce goddess of love and war, did as she wished. Her power and determination were unmatched. Inanna, the goddess of love and war, fights the Ebih mountain. Rocks tumble down its sides, venomous serpents hiss, trees wither and burn, and a storm engulfs the mountain.” ref

Inanna’s Victory and Declaration

“Inanna stood before the mountain range of Ebih, her voice powerful and commanding. “Mountain range,” she said, “you stood tall and proud, reaching up to the heavens. You were beautiful and majestic. But you did not bow to me. You did not show respect. So, I have brought you low.” Inanna’s words were filled with righteous fury. “My father Enlil has spread my great terror over these mountains. “In my victory, I rushed towards the mountain like a surging flood. Like rising water, I overflowed the dam. I imposed my will upon you, Ebih. My victory is complete.” Inanna’s power and dominance were clear. Her triumphant speech echoed through the mountains, marking her as a force to be reckoned with. Praise rose to Inanna, the great child of Nanna, the mighty goddess.” ref

The Significance of the Myth of Inanna and Ebih

“The myth of Inanna and Ebih was a powerful tale of divine retribution and the assertion of authority. Inanna, the fierce goddess of love and war, confronted the proud mountain Ebih, which refused to bow to her. Despite warnings from An, the king of the gods, Inanna’s determination and might lead her to victory. She destroyed the mountain with relentless fury, establishing her dominance and demanding the respect she was due. For the Sumerians, myths like that of Inanna and Ebih were more than just stories. They were sacred narratives that conveyed essential truths about the world, the gods, and human society. These myths provided a framework for understanding the forces of nature and the divine, guiding their religious practices and cultural values.” ref

“Inanna’s myth reinforced the idea that the gods were deeply involved in the affairs of the world and that their favor was crucial for prosperity and survival. It taught lessons about humility, respect, and the consequences of arrogance. By venerating Inanna and other deities, the Sumerians sought to align themselves with the divine will, ensuring harmony and protection. In conclusion, the myth of Inanna and Ebih is a vivid and powerful story that encapsulates the values and beliefs of the Sumerian people. It celebrates the might of the gods, the importance of reverence, and the eternal struggle between order and chaos. Through this timeless narrative, the Sumerians expressed their understanding of the cosmos and their place within it, creating a legacy that continues to inspire and intrigue us today.” ref

The Celestial Stone: A Cultural History of Lapis Lazuli

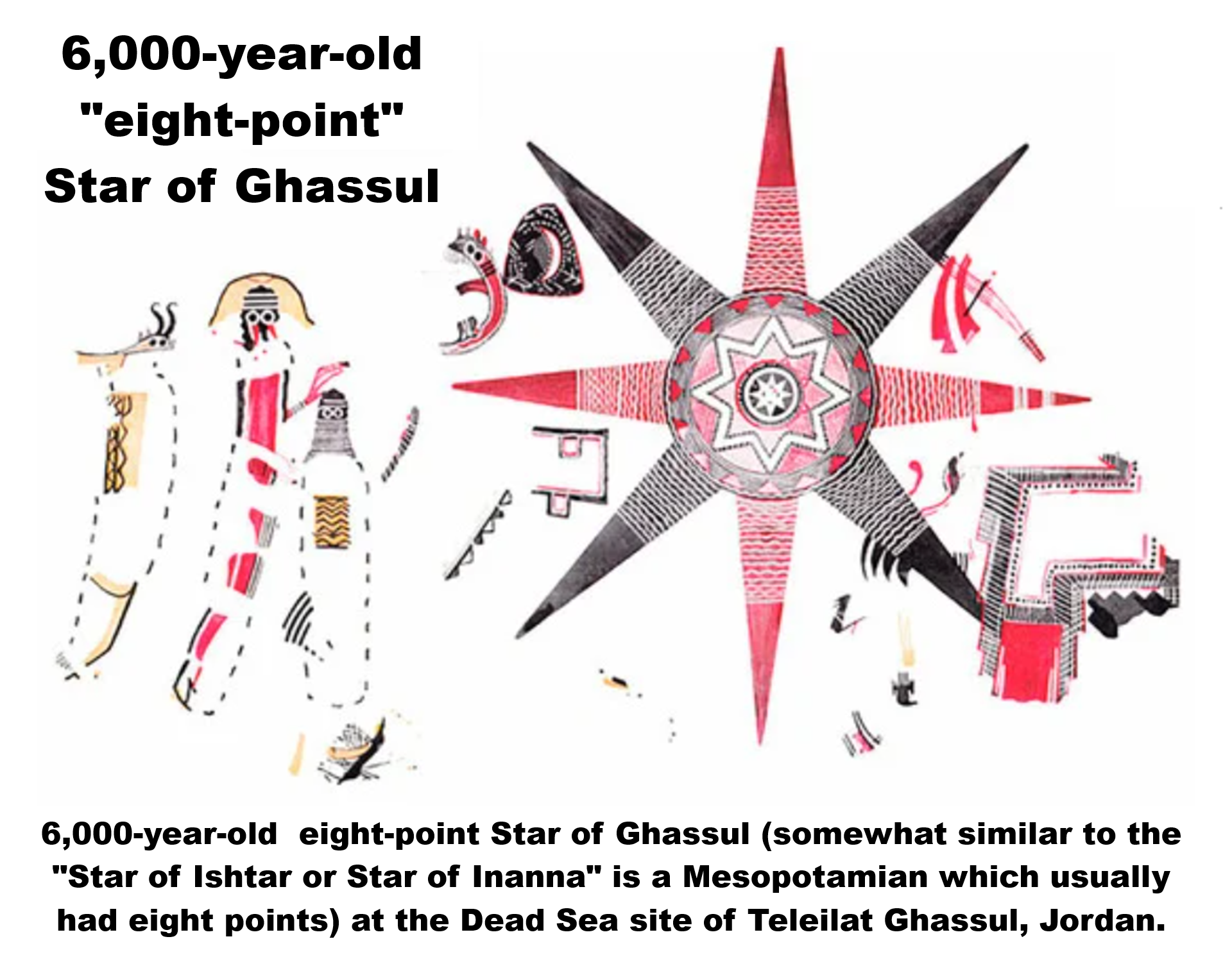

“Sumerians believed that the stone houses the deity’s soul, which could be connected to through jewelry worn on the body. The Sumerian sky goddess Inanna had a necklace and staff made of lapis lazuli. Pigment obtained from the rich blue mineral was used to paint the Madonna’s robes. In fact, the rock, mined in the mountains of Central Asia, is vital to many cultures.” ref

“The cold, inhospitable wilderness of the Afghan province Badakhshan is a network of rocky peaks, furrowed with treacherous gorges. The mountain range of the Hindu Kush rises there, 24,600 feet above sea level. Its name fully reflects the hostile character of this place—in Pashto, Hindu Kush means “killer of Hindus.” Despite these adverse conditions, the mines here have been exploited continuously for more than six thousand years. They are used to extract lapis lazuli—a stone which has become an attribute of divinity in many cultures, and was one of the first luxury goods.” ref

The Rarest of Pigments