ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

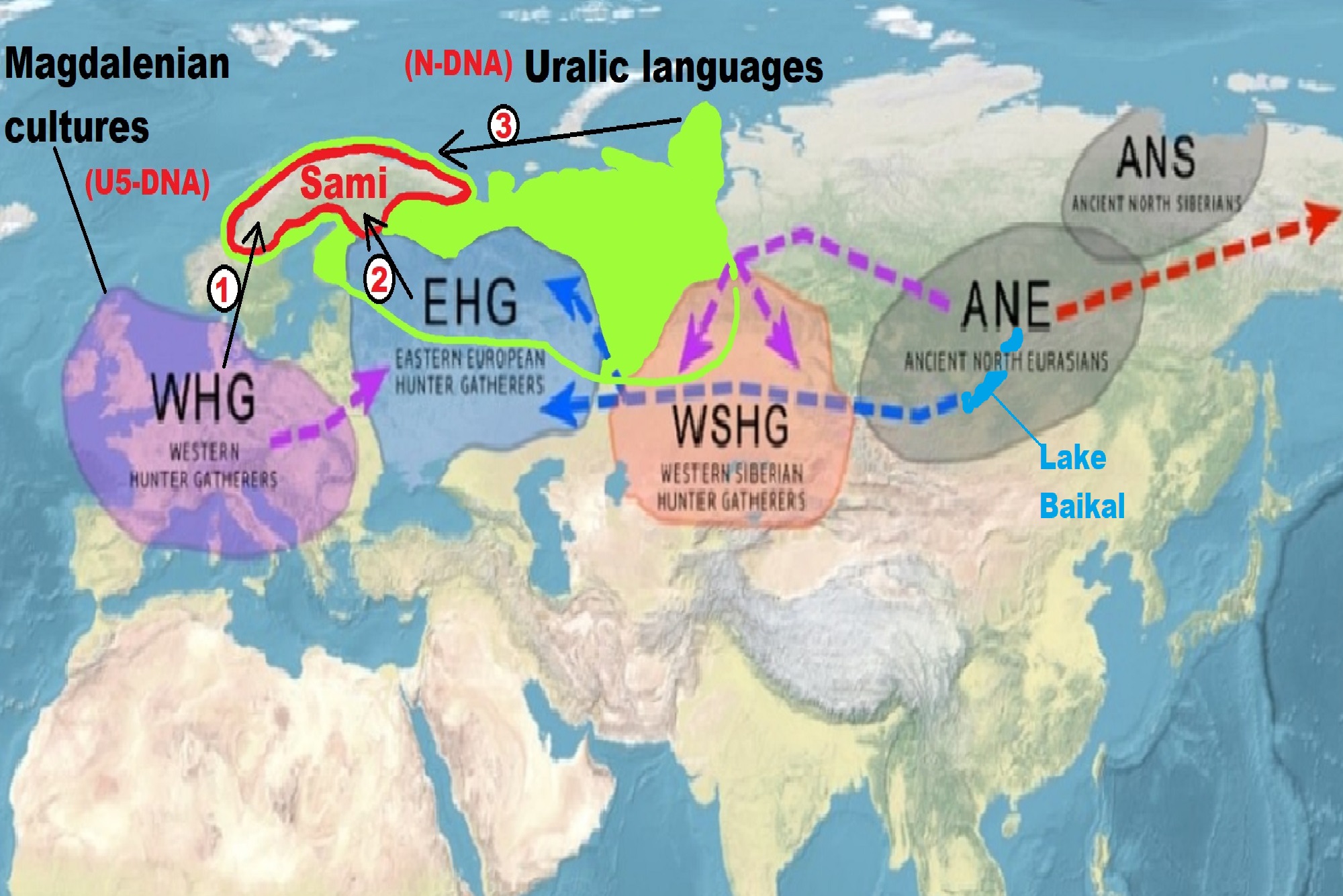

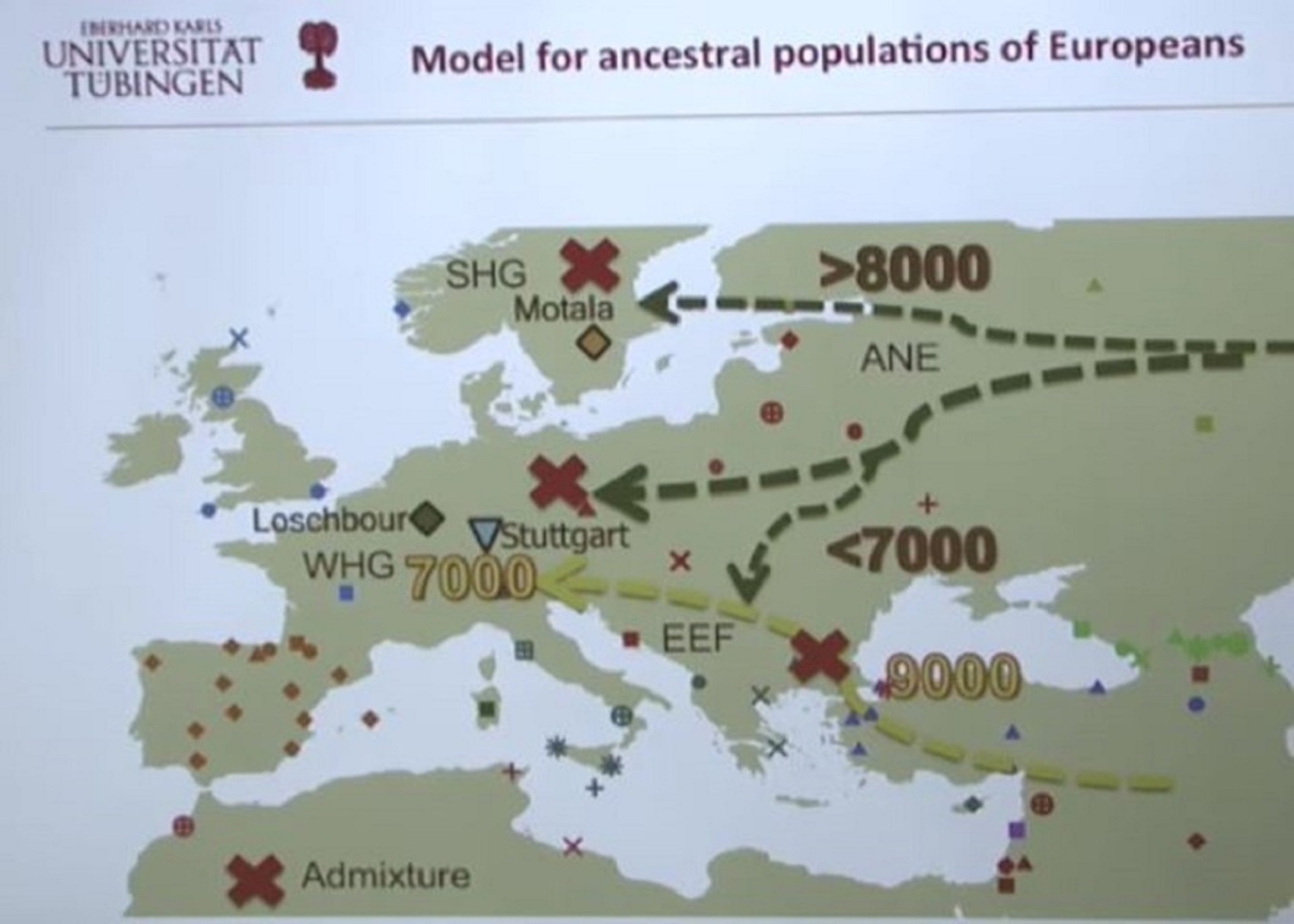

Genetic Relations to Ancient North Eurasians (ANE):

Eastern hunter-gatherer (EHG)

Caucasus hunter-gatherer (CHG)

Zagros/Iranian Hunter-Gatherer (IHG)

Iranian Neolithic Farmers (INF)

Anatolian hunter-gatherer (AHG)

Anatolian Neolithic Farmers (ANF)

Early European Farmers (EEF)

Yamnaya/Steppe Herders (WSH)

Villabruna 1 (burial)/Ripari Villabruna rock shelter in northern Italy (14,000 years old)

Satsurblia Cave (burial) in the Country of Georgia (13,000 years old)

Motala (burial) (8,000 years old)

A 23,000-year-old southern Iberian individual links human groups that lived in Western Europe before and after the Last Glacial Maximum

“Following the Bølling/Allerød warming interstadial (14,000 years ago), the Goyet Q2 cluster was replaced by the Villabruna cluster in central Europe, named for its oldest Epigravettian-associated individual from northern Italy, but which also includes most of the Epipalaeolithic- and Mesolithic-associated groups from central and western Europe, all of which are also known as western hunter-gatherers (WHG). In this genetic landscape, Iberian hunter-gatherers (HG) stood out as they retained higher proportions of the Goyet Q2-like ancestry during the Epipalaeolithic and Mesolithic periods and thus are often considered separate.” ref

Human populations underwent range contractions during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) which had lasting and dramatic effects on their genetic variation. The genetic ancestry of individuals associated with the post-LGM Magdalenian technocomplex has been interpreted as being derived from groups associated with the pre-LGM Aurignacian. However, both these ancestries differ from that of central European individuals associated with the chronologically intermediate Gravettian. Thus, the genomic transition from pre- to post-LGM remains unclear also in western Europe, where we lack genomic data associated with the intermediate Solutrean, which spans the height of the LGM. Here we present genome-wide data from sites in Andalusia in southern Spain, including from a Solutrean-associated individual from Cueva del Malalmuerzo, directly dated to ~23,000 years ago.” ref

“The Malalmuerzo individual carried genetic ancestry that directly connects earlier Aurignacian-associated individuals with post-LGM Magdalenian-associated ancestry in western Europe. This scenario differs from Italy, where individuals associated with the transition from pre- and post-LGM carry different genetic ancestries. This suggests different dynamics in the proposed southern refugia of Ice Age Europe and posits Iberia as a potential refugium for western European pre-LGM ancestry. Moreover, individuals from Cueva Ardales, which were thought to be of Palaeolithic origin, date younger than expected and, together with individuals from the Andalusian sites Caserones and Aguilillas, fall within the genetic variation of the Neolithic, Chalcolithic, and Bronze Age individuals from southern Iberia.” ref

“Abstract: The concept of grief, the metamorphosis of the deceased into the departed, a subject recreated and rethought by the psyche, is crucial for understanding the significance of the grave and funeral rites. We can divide the funeral rites into three phases: seeing the dead person presented socialized, hiding him to begin the mourning process, and finally metamorphosing him into the deceased. Moreover, these three phases typically require the involvement of several community members, some of whom may be less affected by sorrow — a factor that hinders action — compared to close relatives. Considering these factors, it becomes apparent that grief and, consequently, the tomb are more fundamentally social phenomena than cultural ones. The cultural aspect is an overlay, as beliefs and religions facilitate the mourning process by providing guidelines for conduct and contemplation. An evolutionary perspective on the recognition of death and griefs considers these definitions, cognitive developments during human growth, and the cognitive evolution of hominids. Recognizing another’s death without integrating the concept of one’s mortality could have emerged early in human evolution and been a factor in developing consciousness in a feedback loop. Moreover, the funerary rites and tombs are probably older than is commonly accepted by many researchers to date.” ref

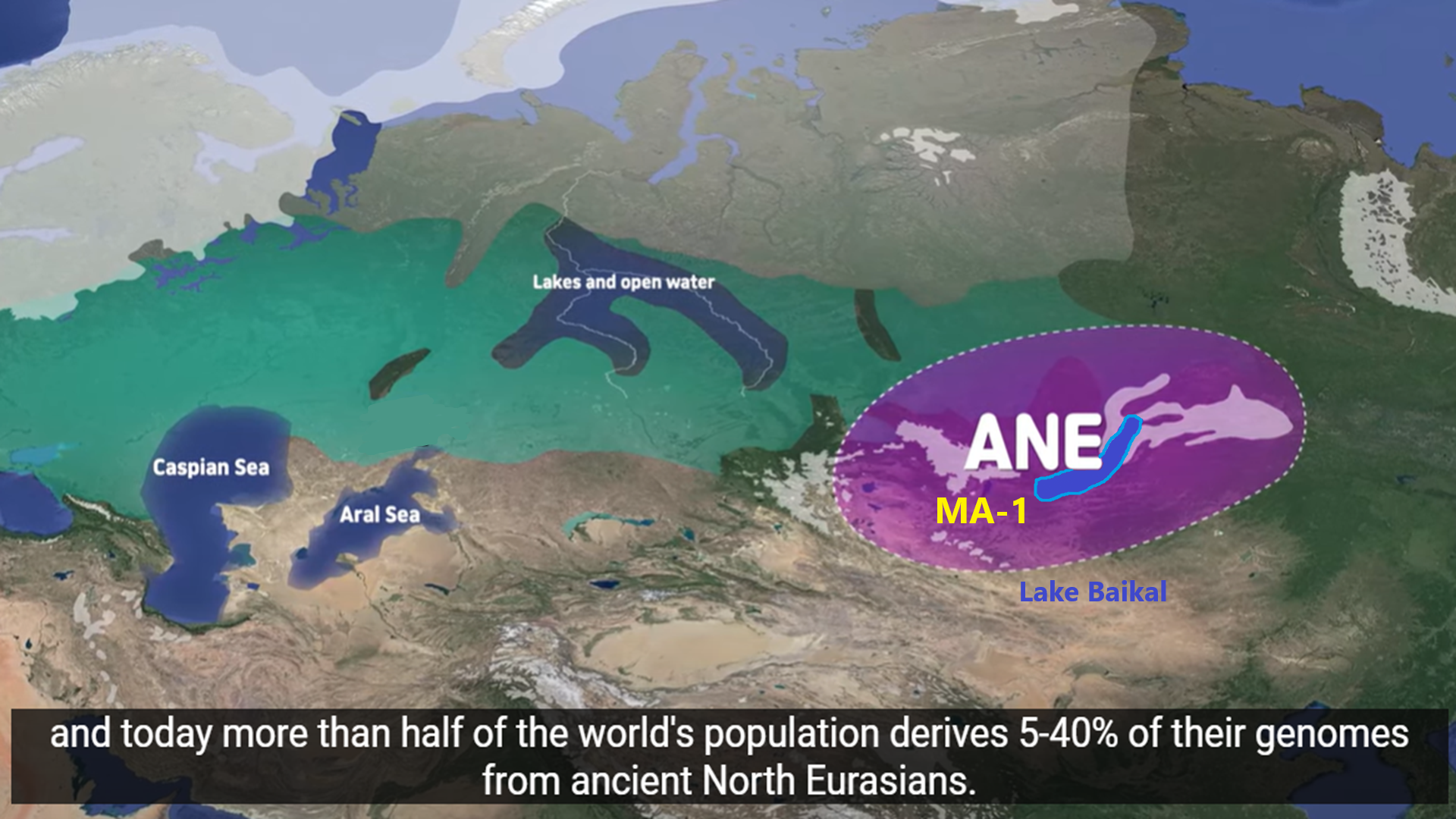

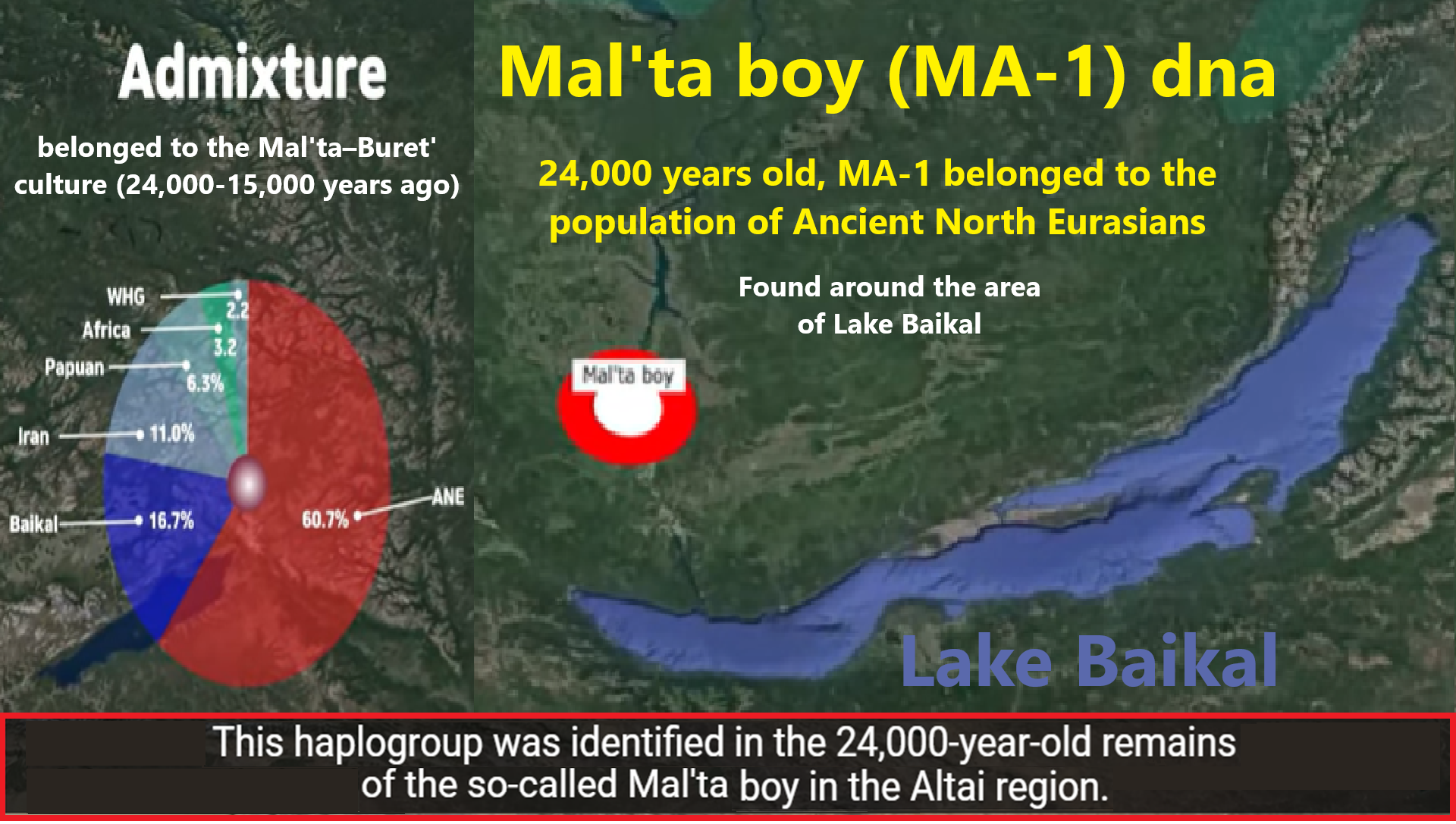

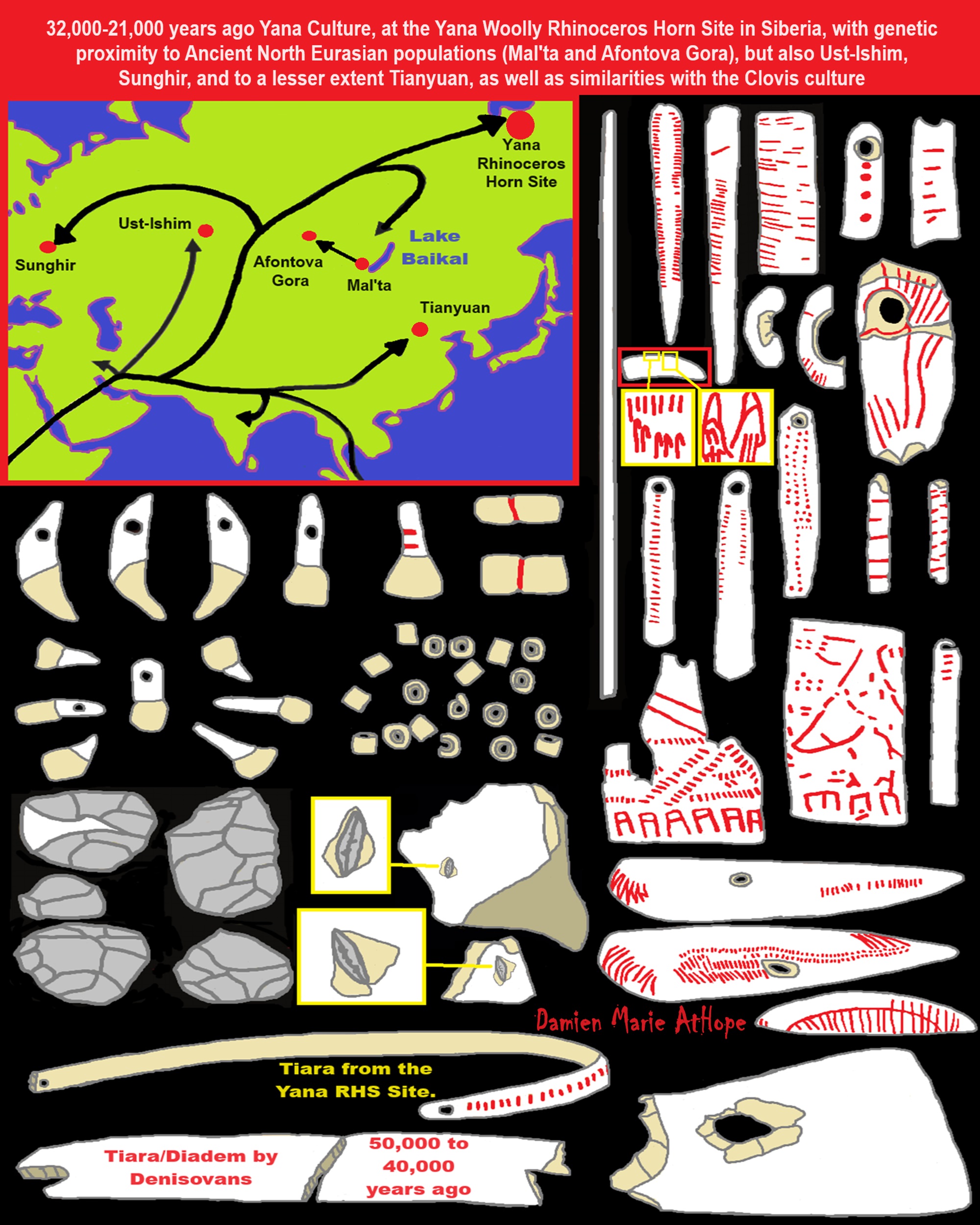

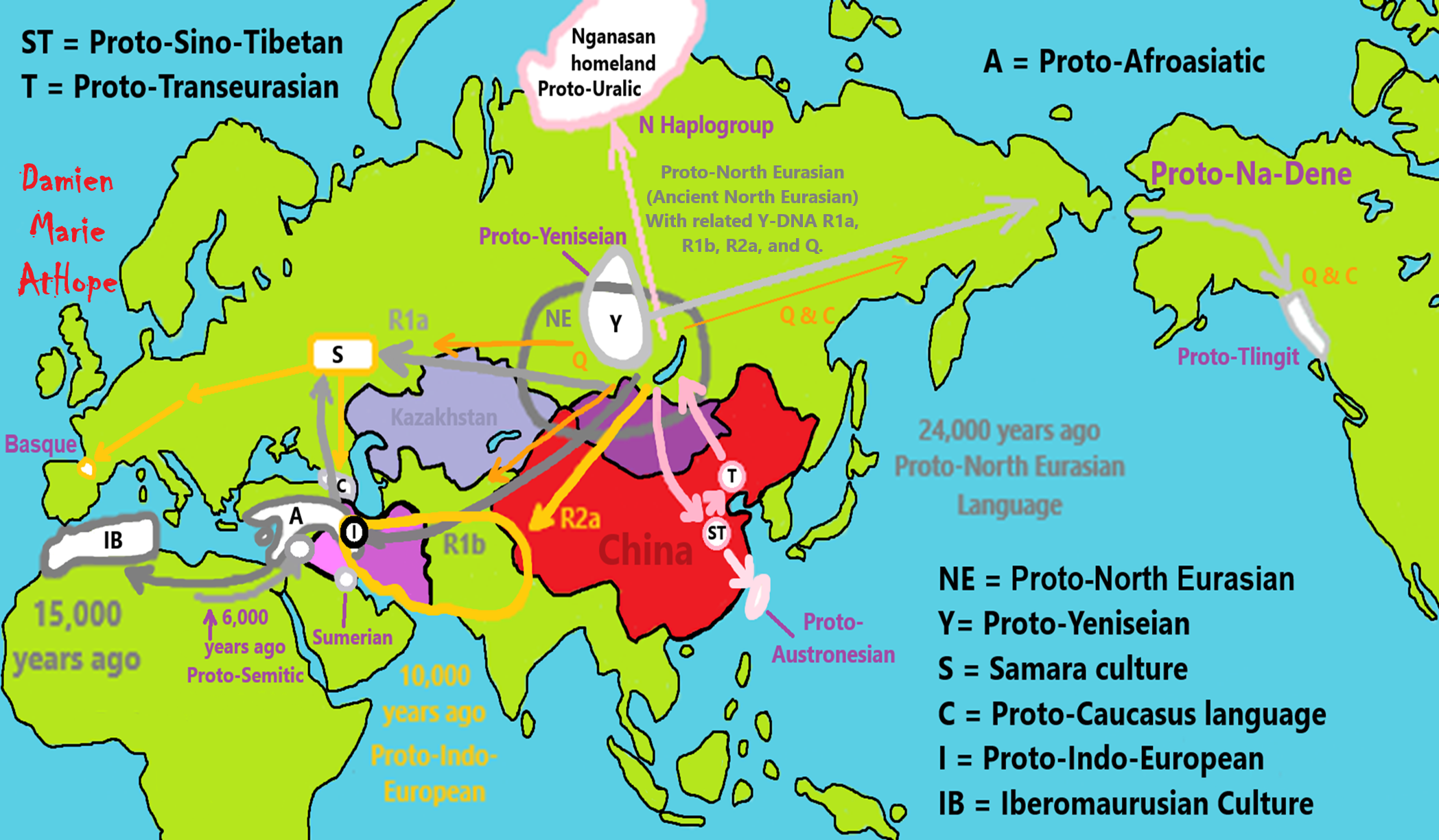

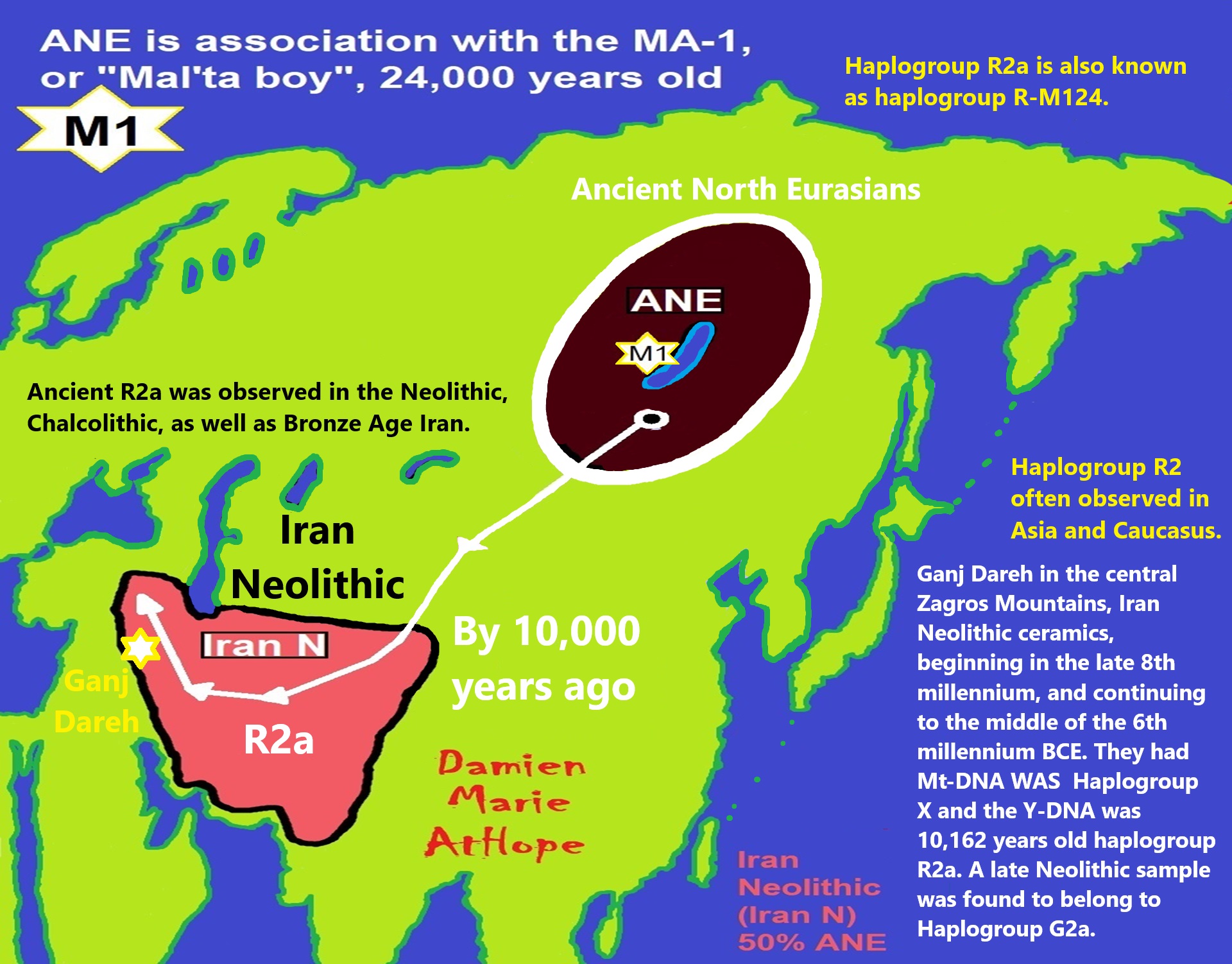

Ancient North Eurasian

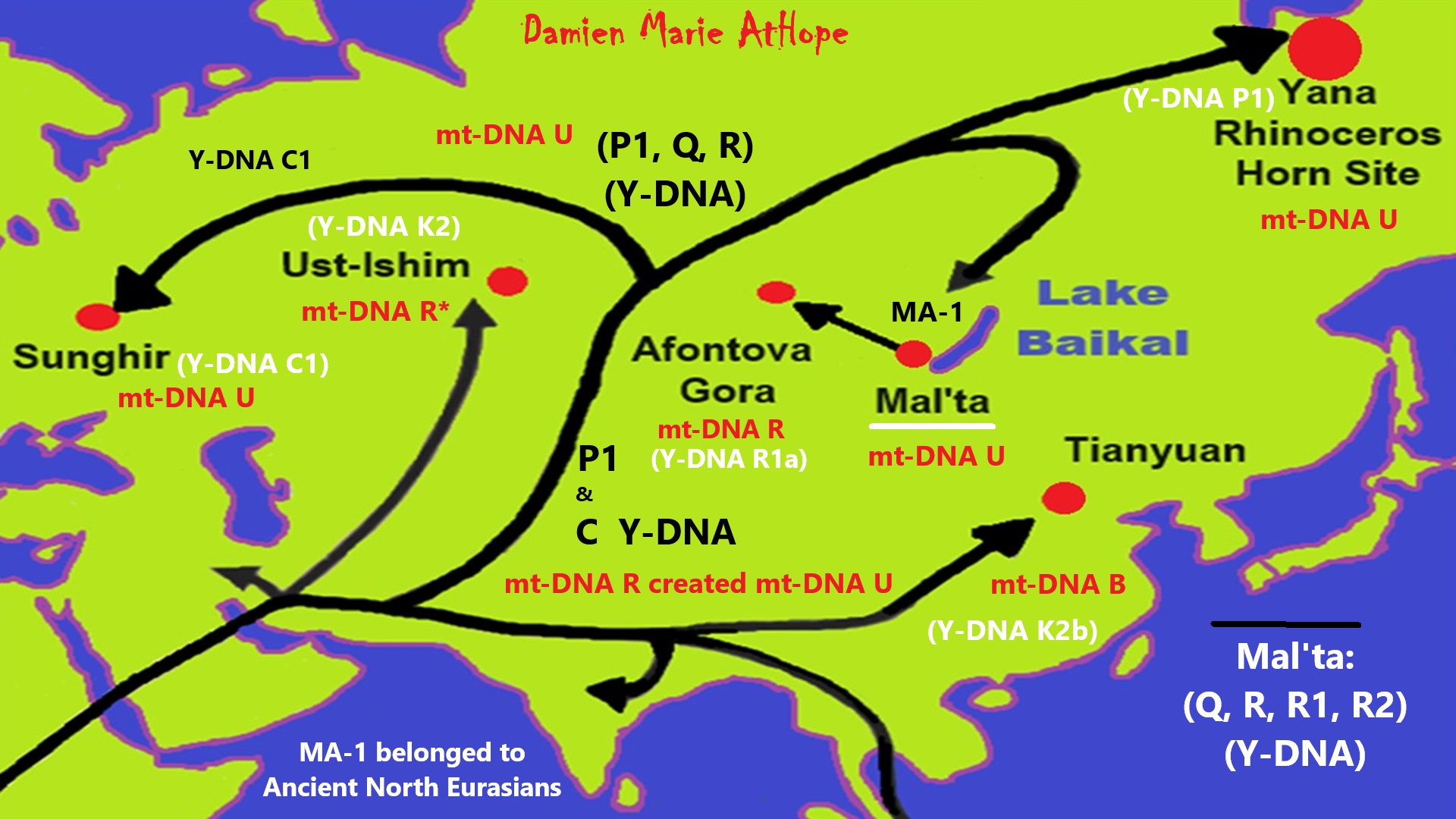

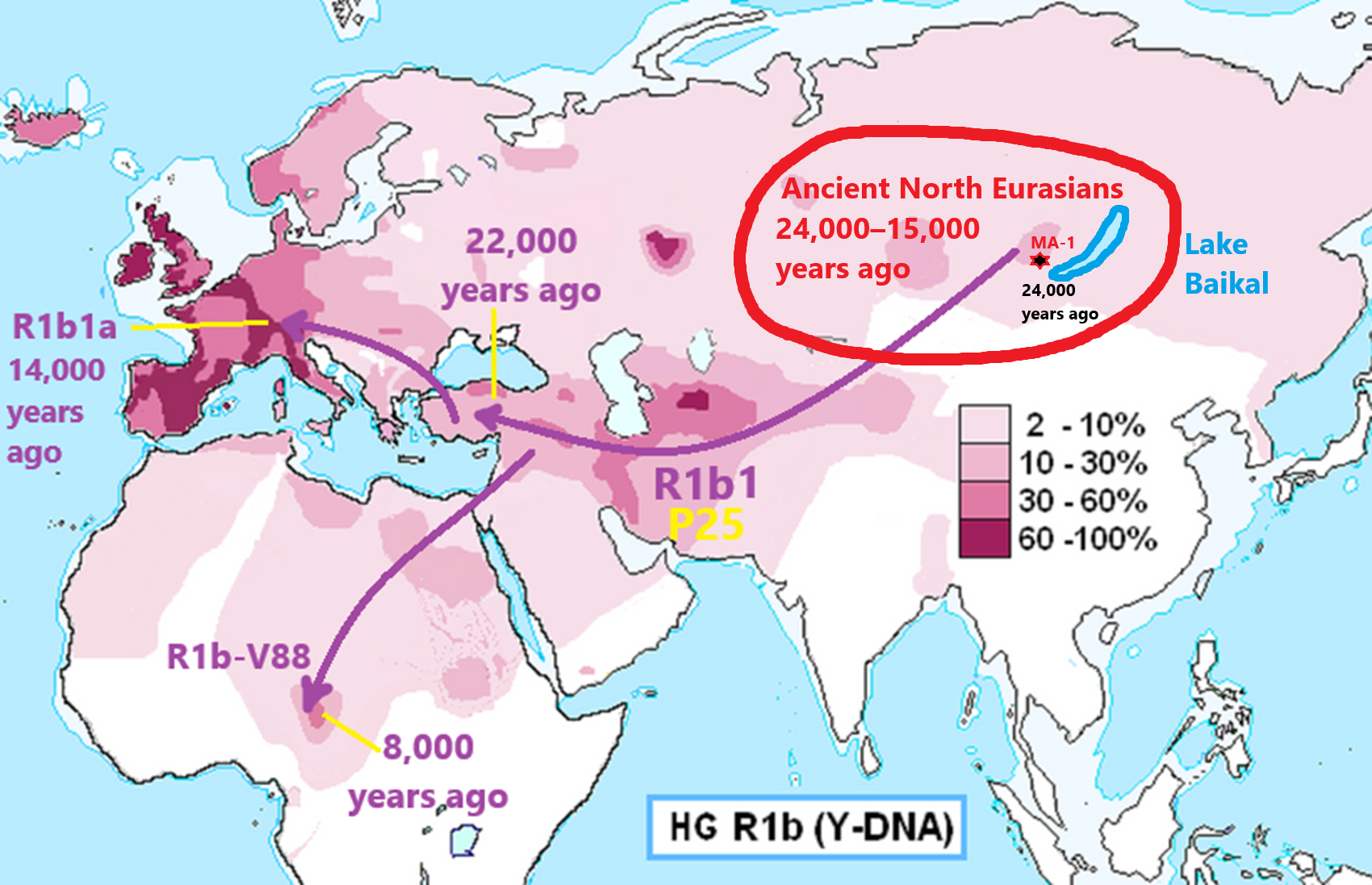

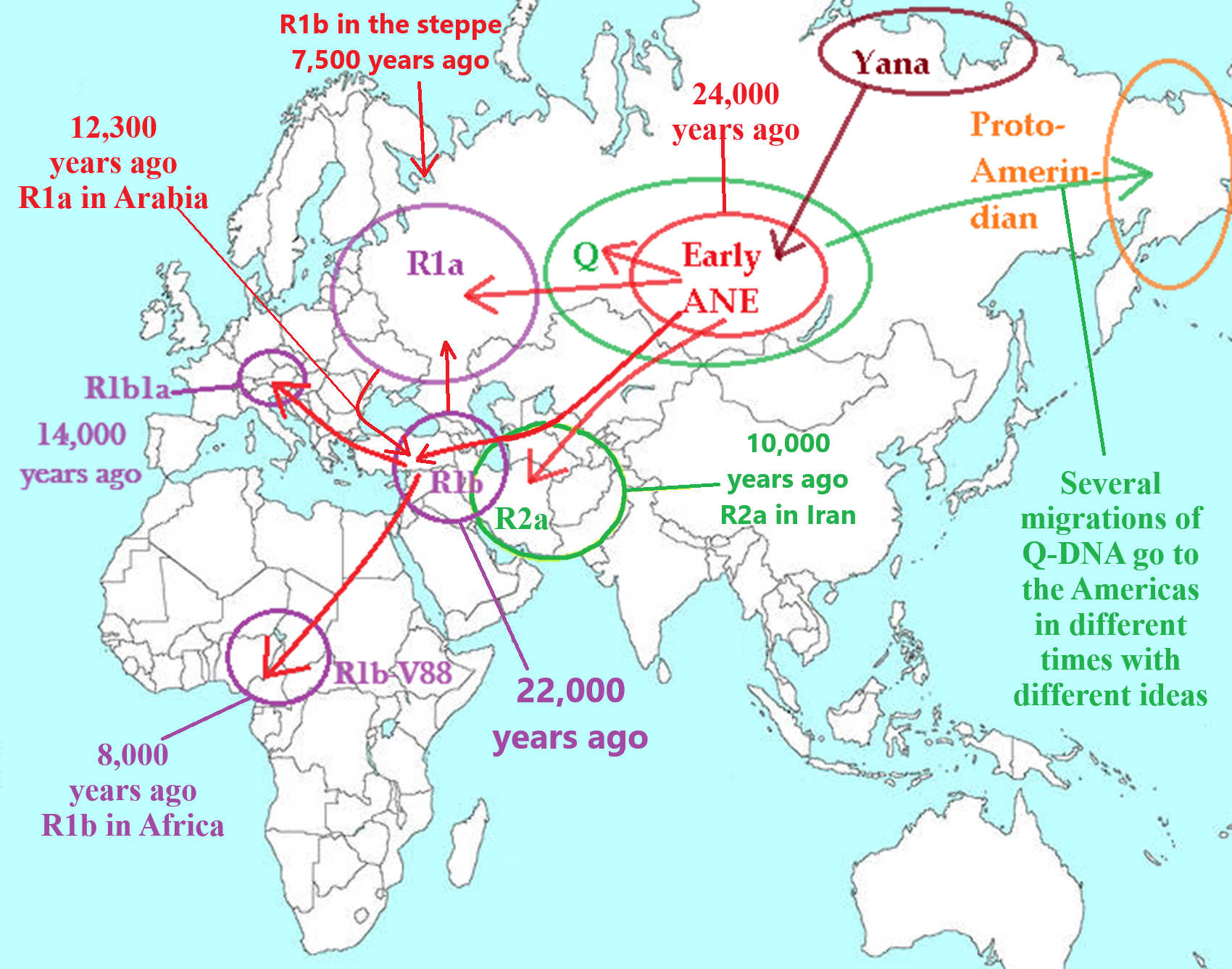

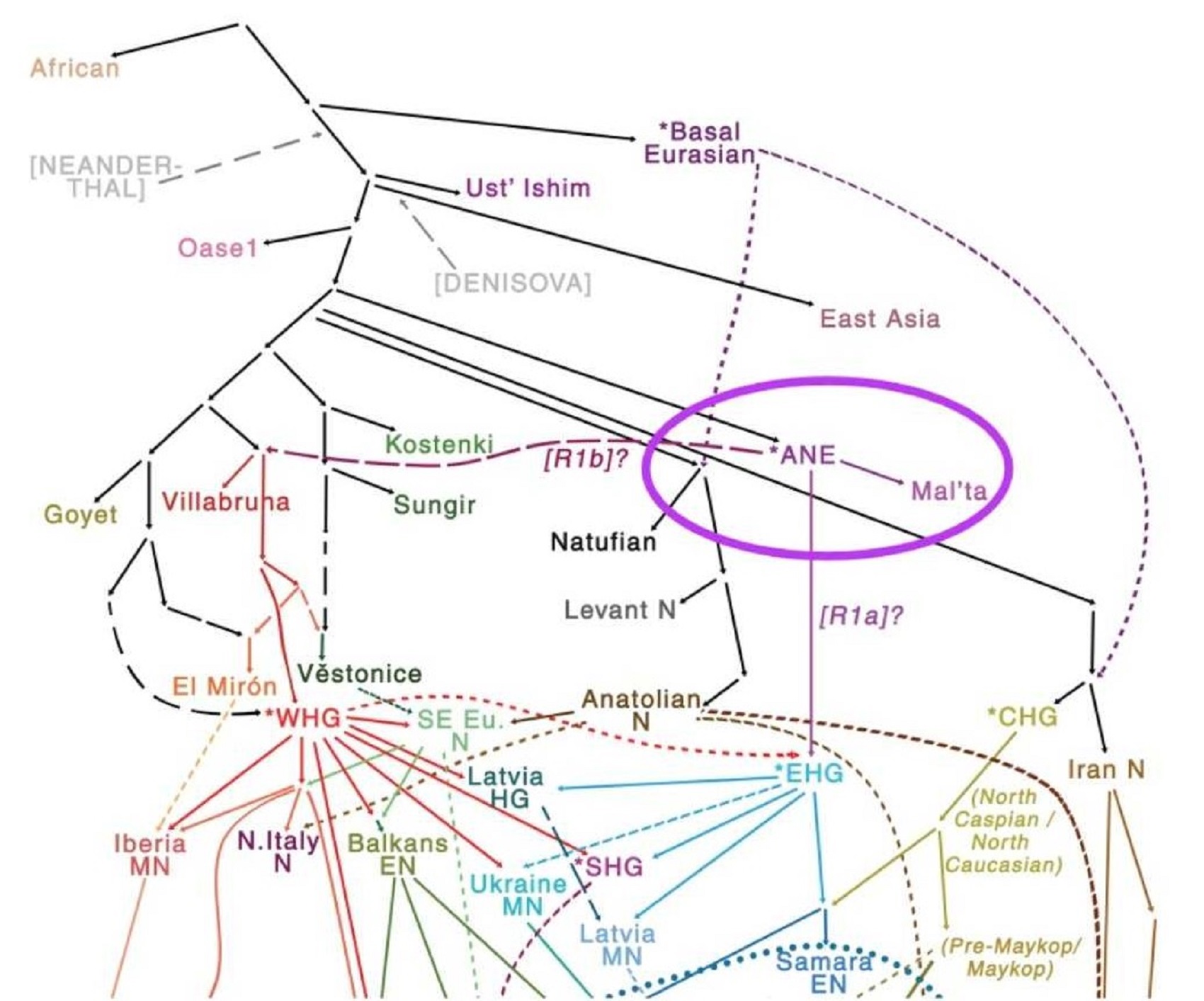

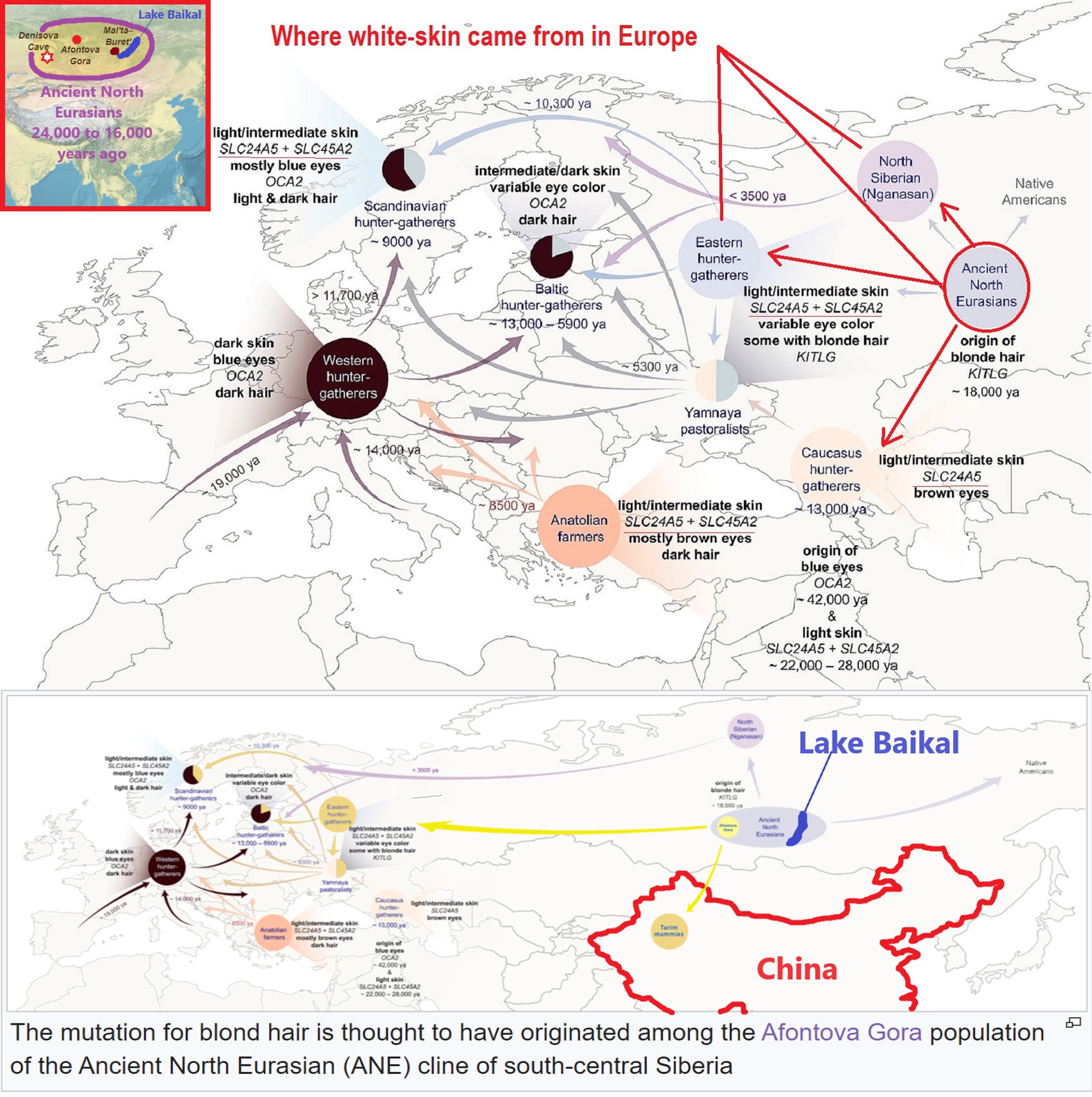

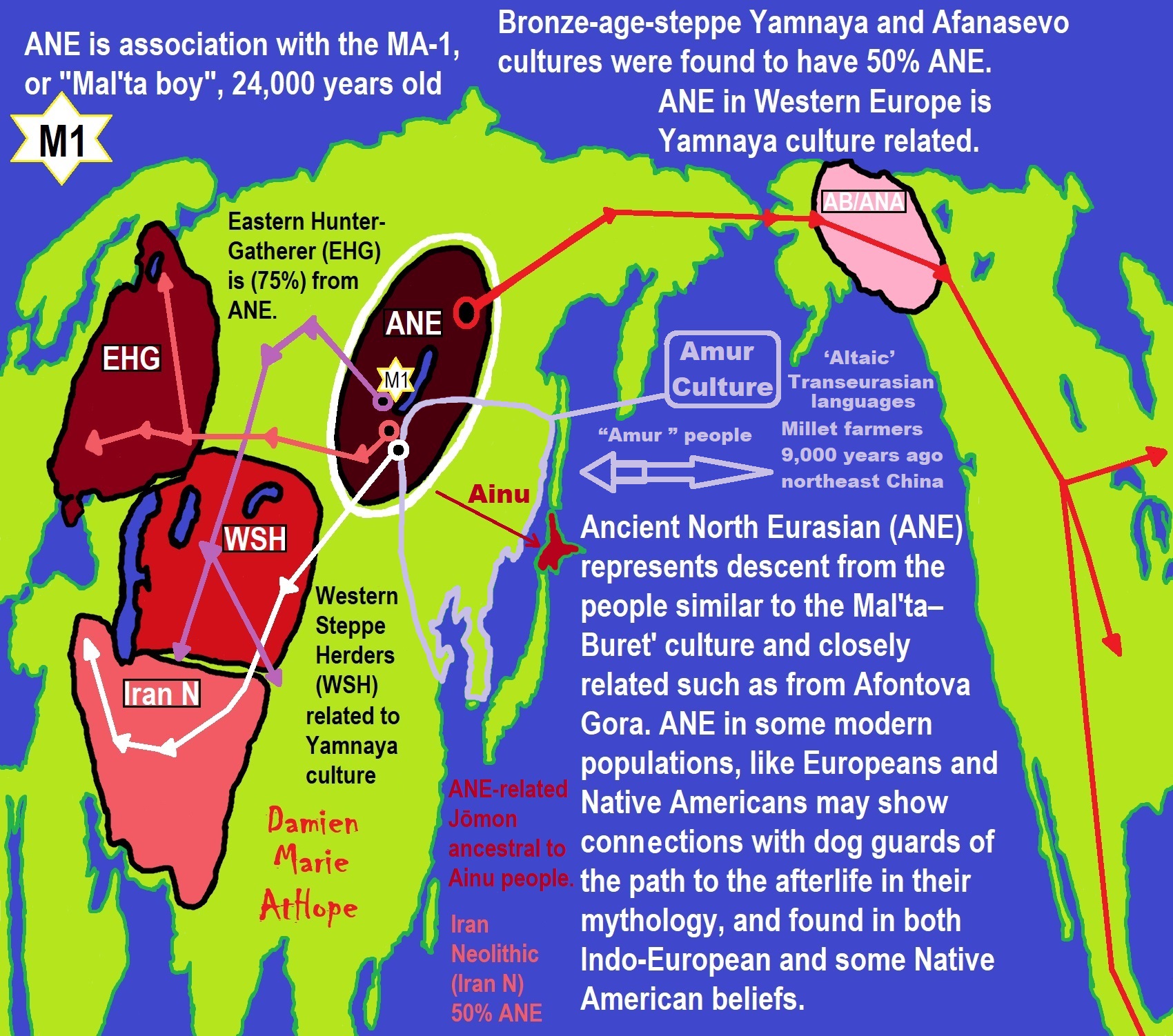

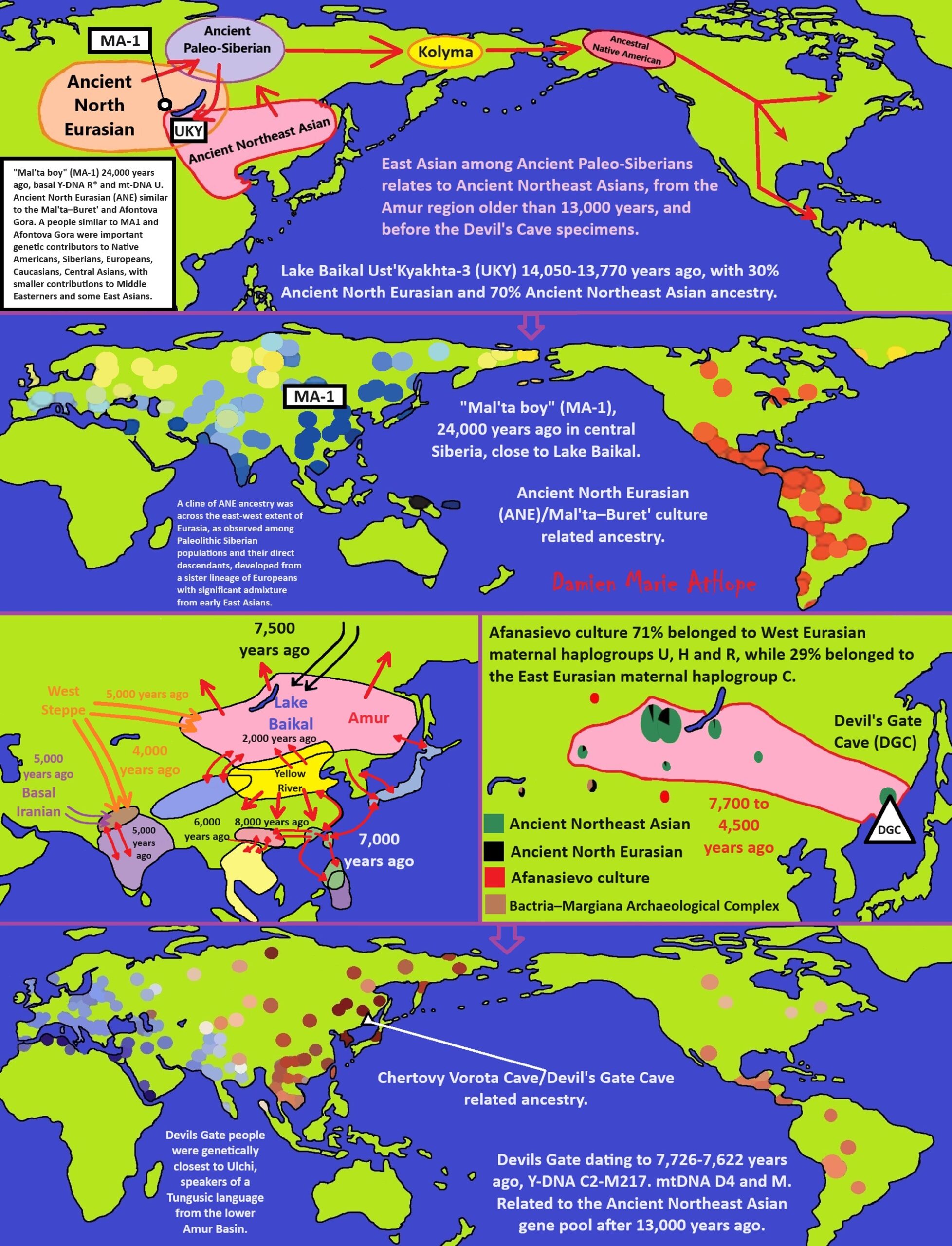

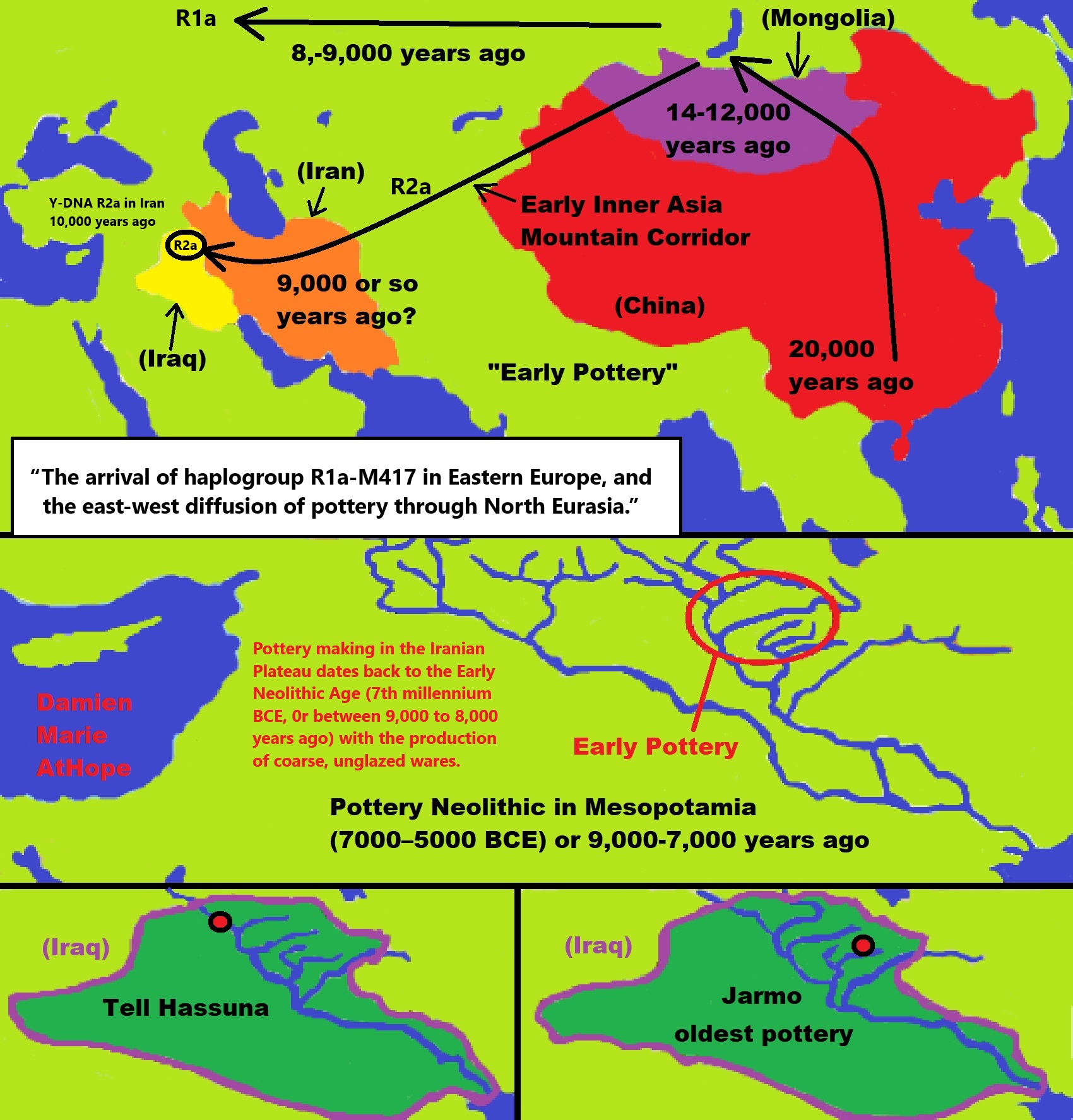

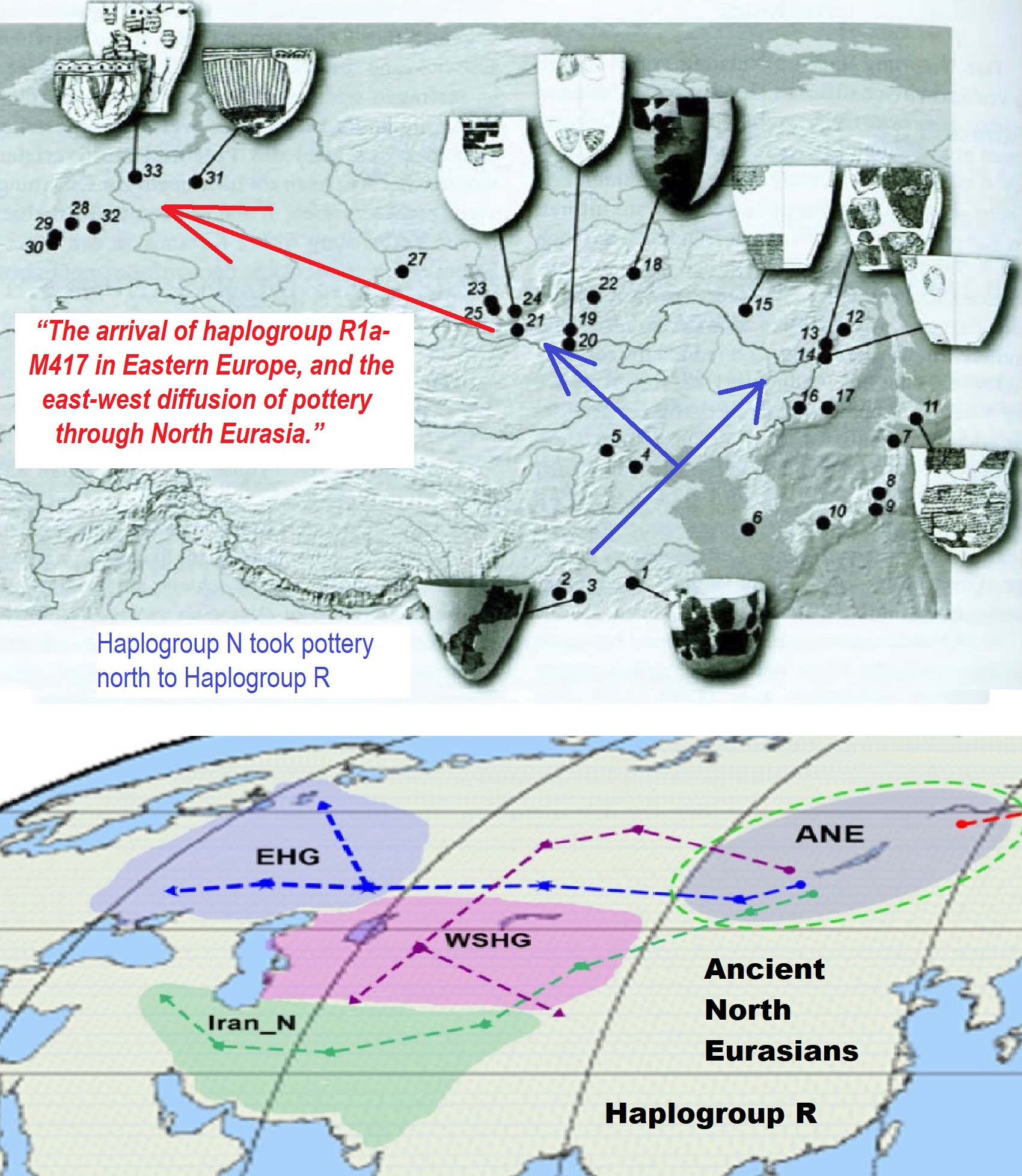

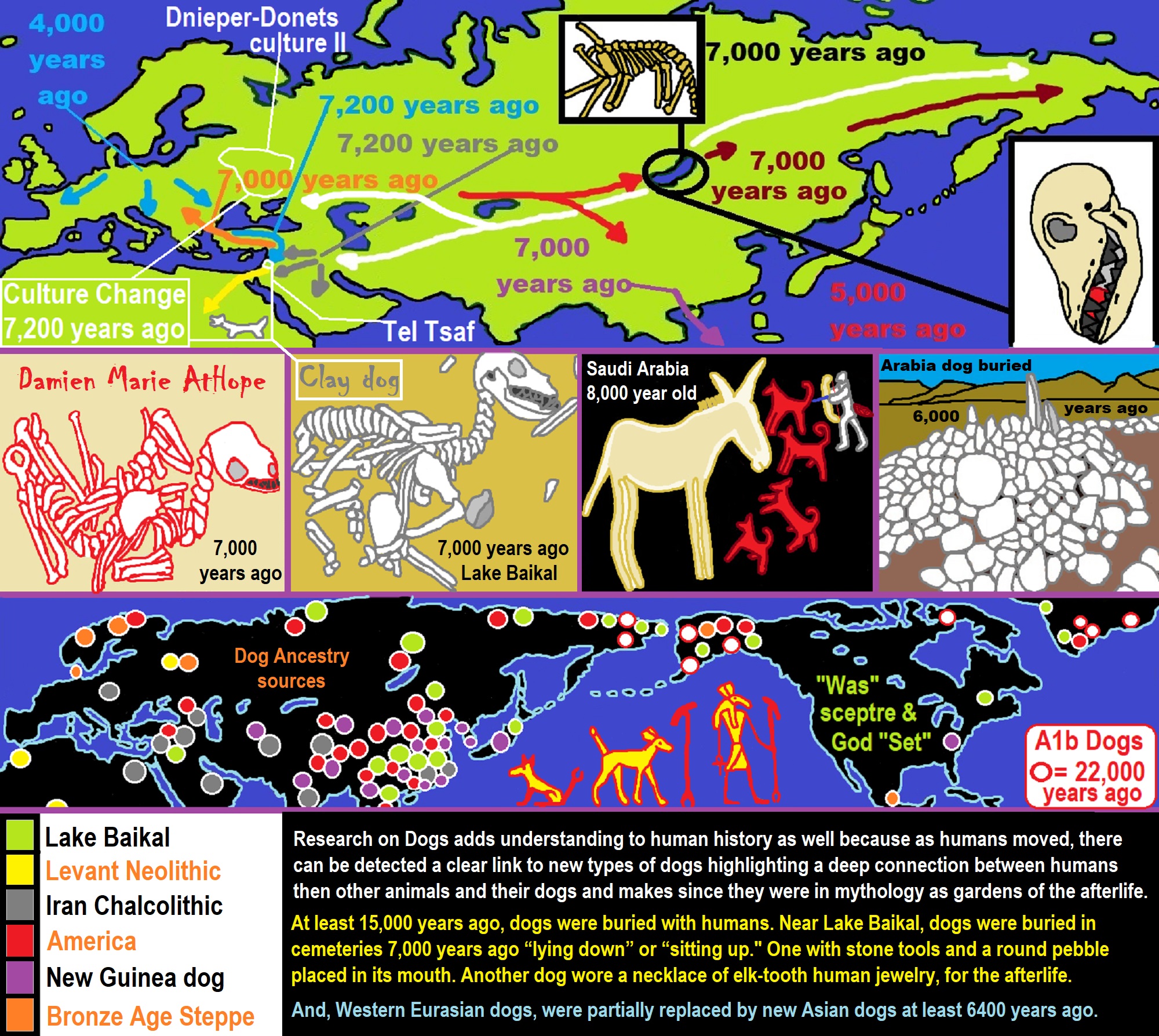

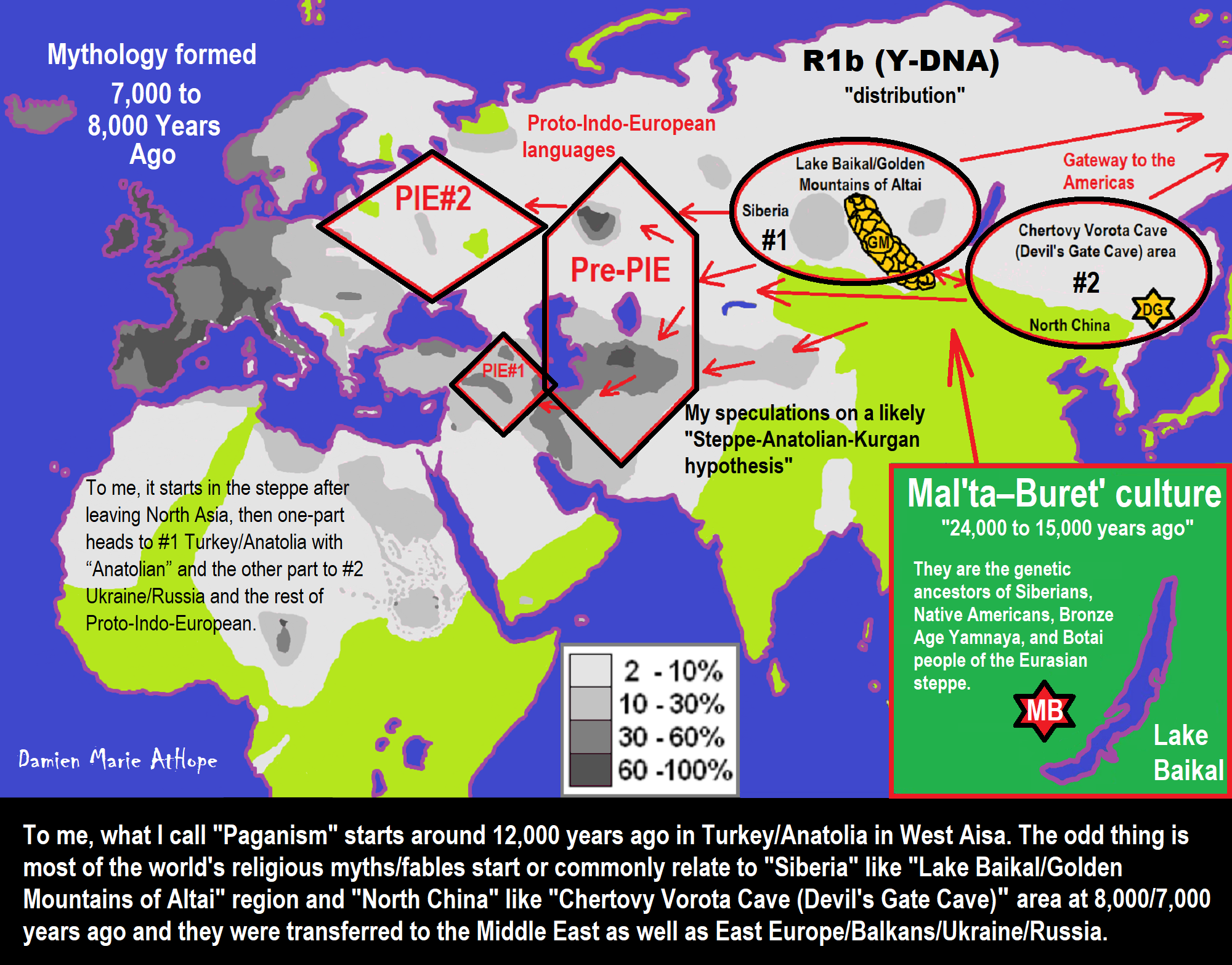

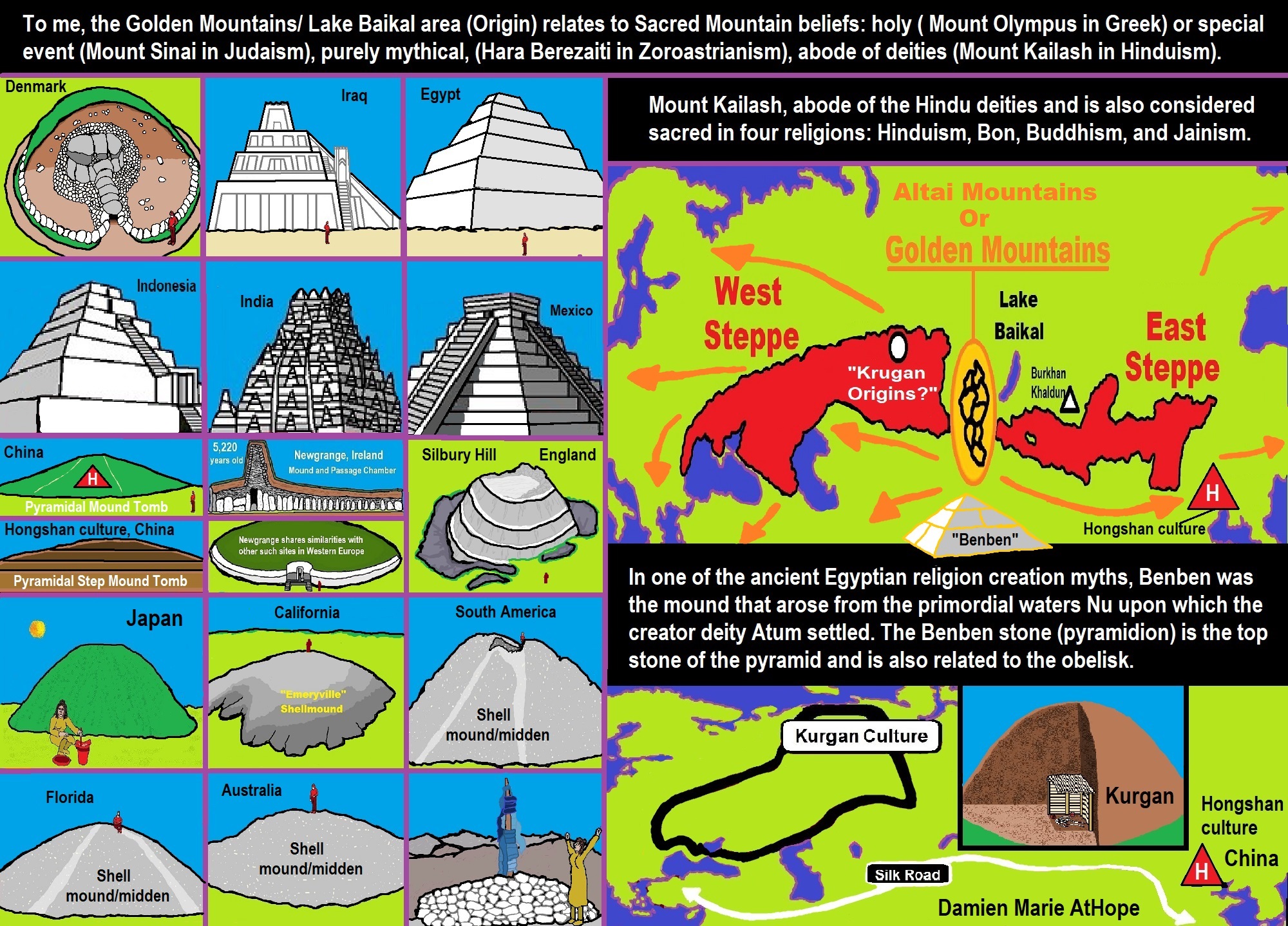

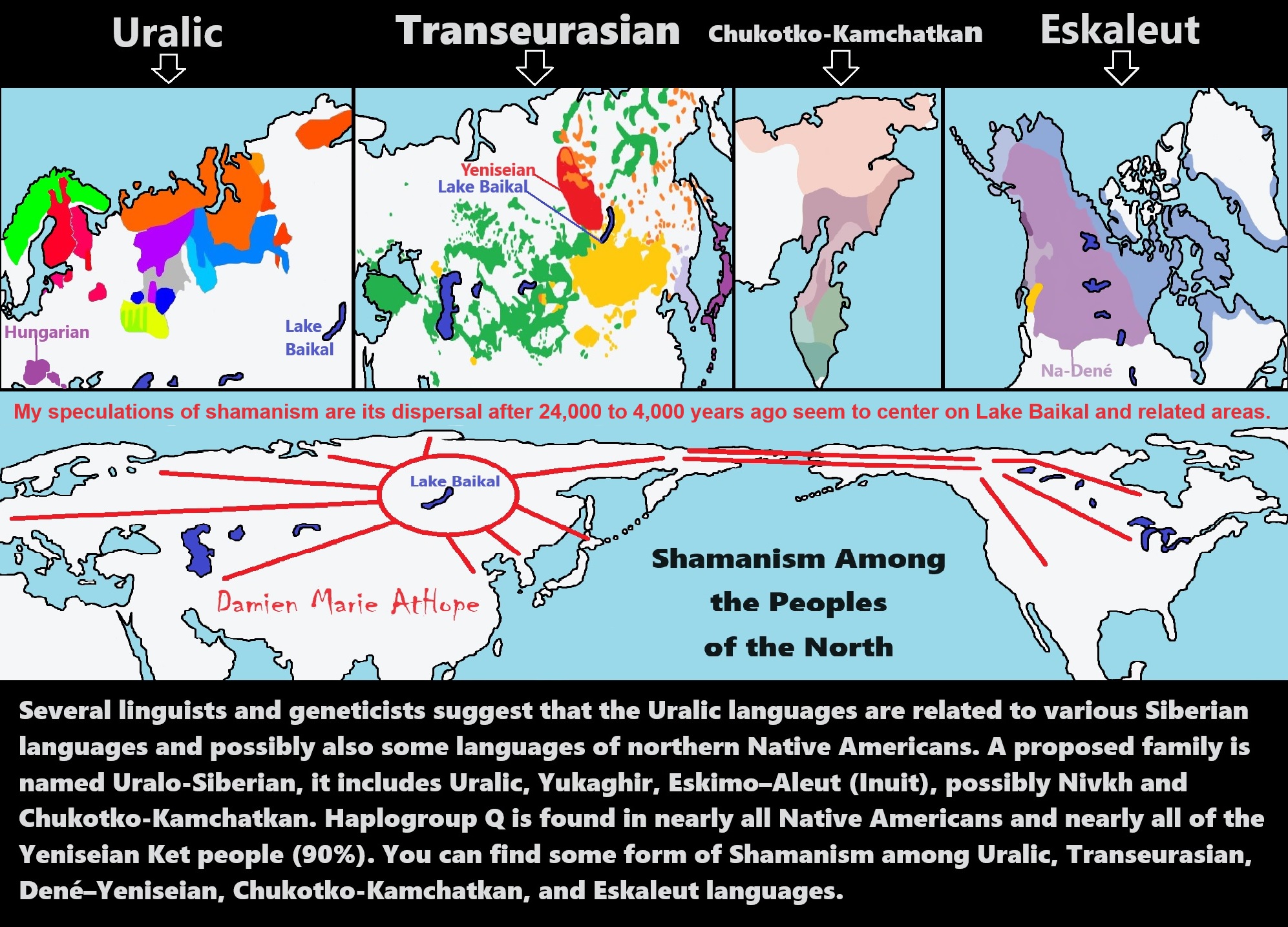

“In archaeogenetics, the term Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) is the name given to an ancestral component that represents the lineage of the people of the Mal’ta–Buret’ culture (c. 24,000 years ago) and populations closely related to them, such as the Upper Paleolithic individuals from Afontova Gora in Siberia. Genetic studies also revealed that the ANE are closely related to the remains of the preceding Yana Culture (c. 32,000 years ago), which were dubbed as ‘Ancient North Siberians‘ (ANS). Ancient North Eurasians are predominantly of West Eurasian ancestry (related to European Cro-Magnons and ancient and modern peoples in West Asia) who arrived in Siberia via the “northern route,” but also derive a significant amount of their ancestry (c. 1/3) from an East Eurasian source, having arrived to Siberia via the “southern route.” ref

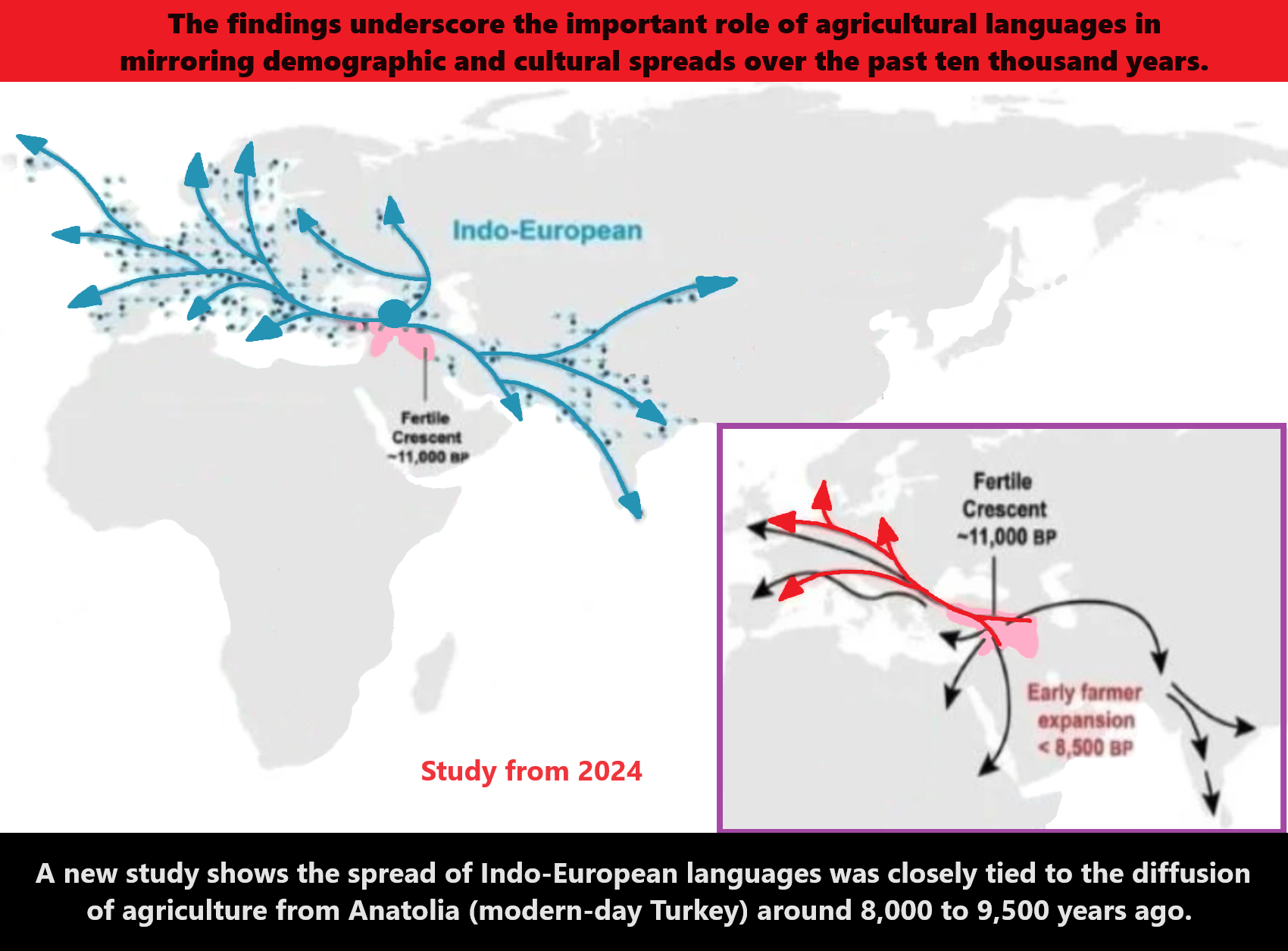

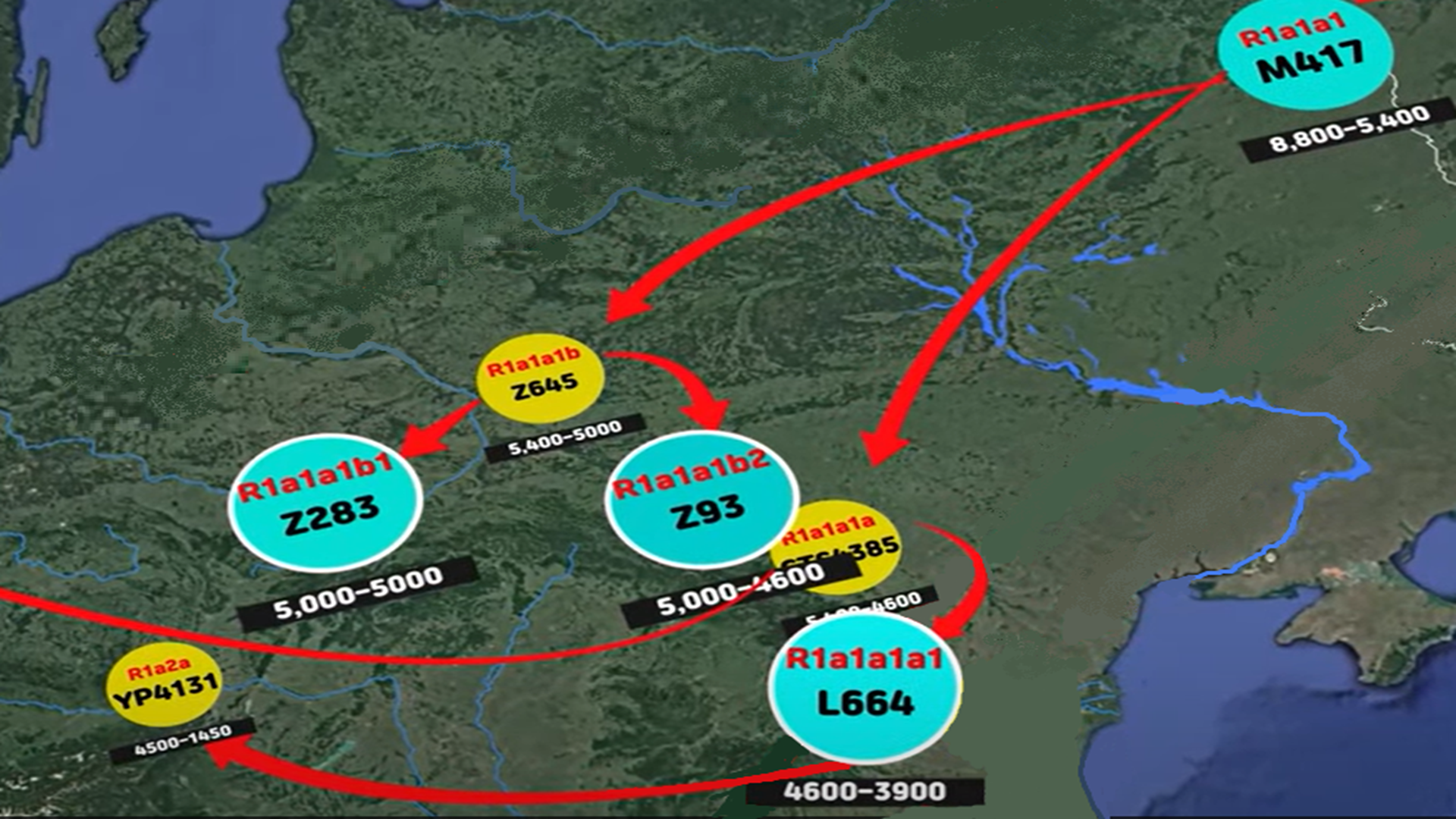

“Around 20,000 to 25,000 years ago, a branch of Ancient North Eurasian people mixed with Ancient East Asians, which led to the emergence of Ancestral Native American, Ancient Beringian, and Ancient Paleo-Siberian populations. It is unknown exactly where this population admixture took place, and two opposing theories have put forth different migratory scenarios that united the Ancient North Eurasians with ancient East Asian populations. Later, ANE populations migrated westward into Europe and admixed with European Western hunter-gatherer (WHG)-related groups to form the Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) group, which later admixed with Caucasus hunter-gatherers to form the Western Steppe Herder group, which became widely dispersed across Eurasia during the Bronze Age.” ref

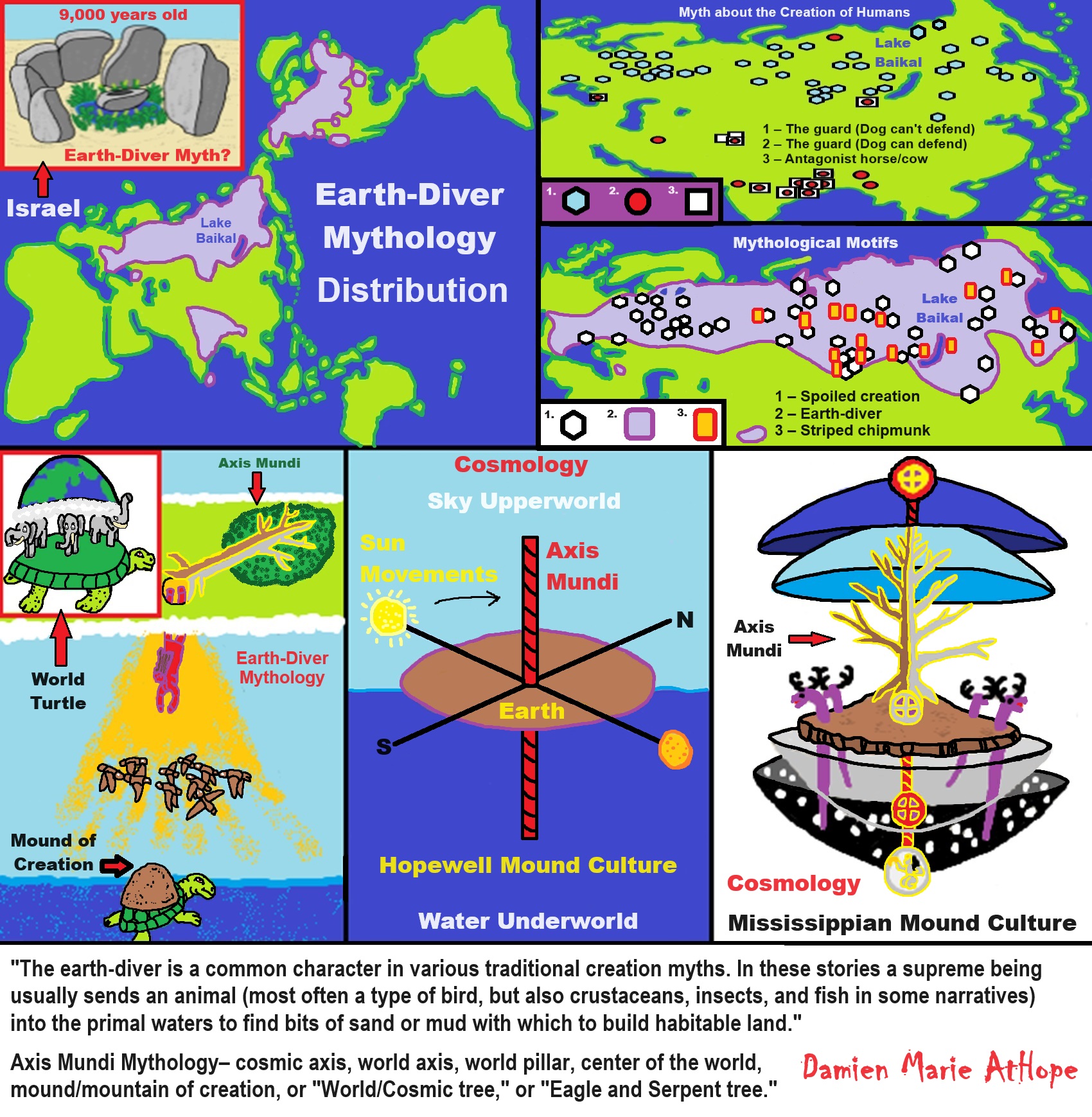

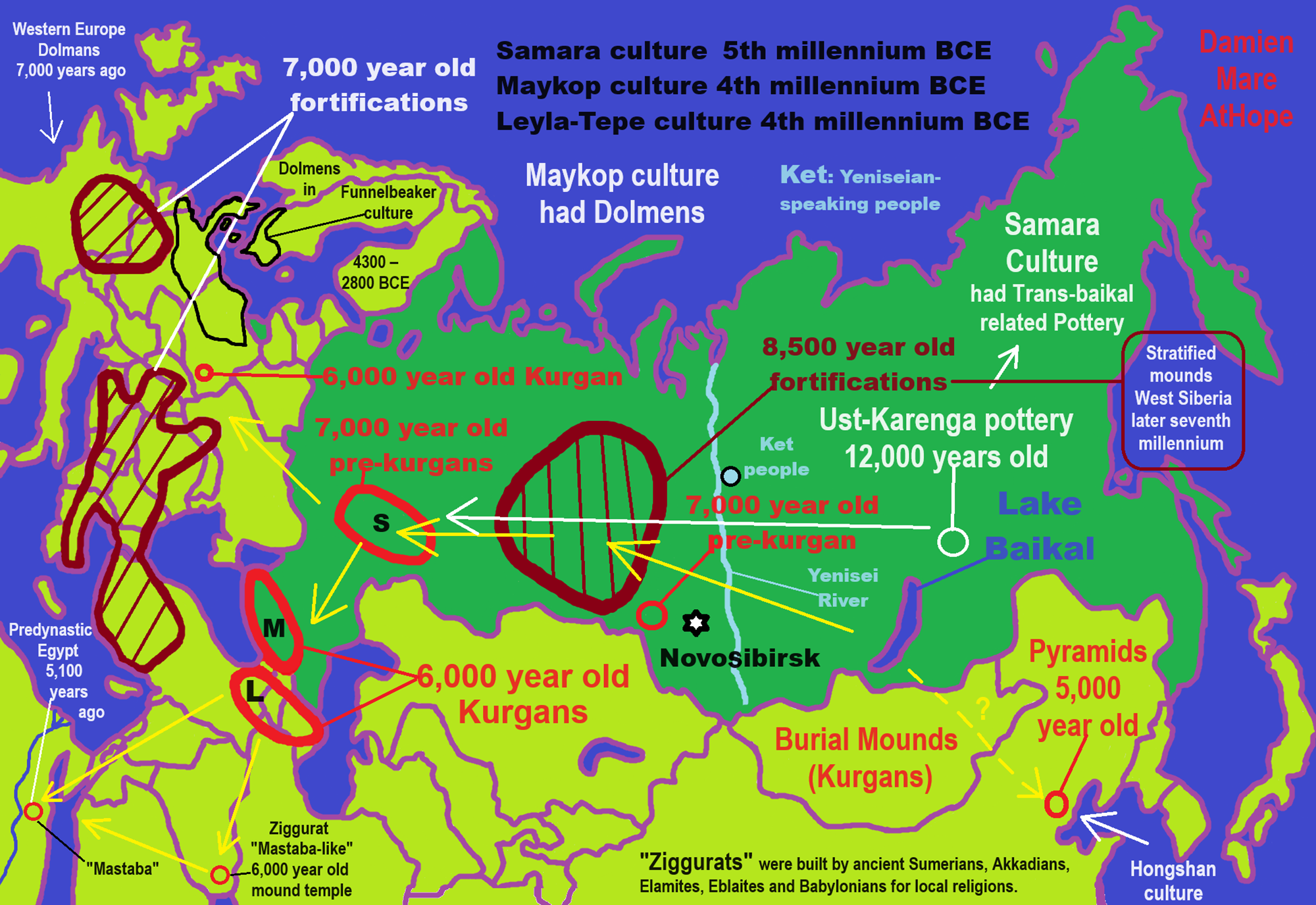

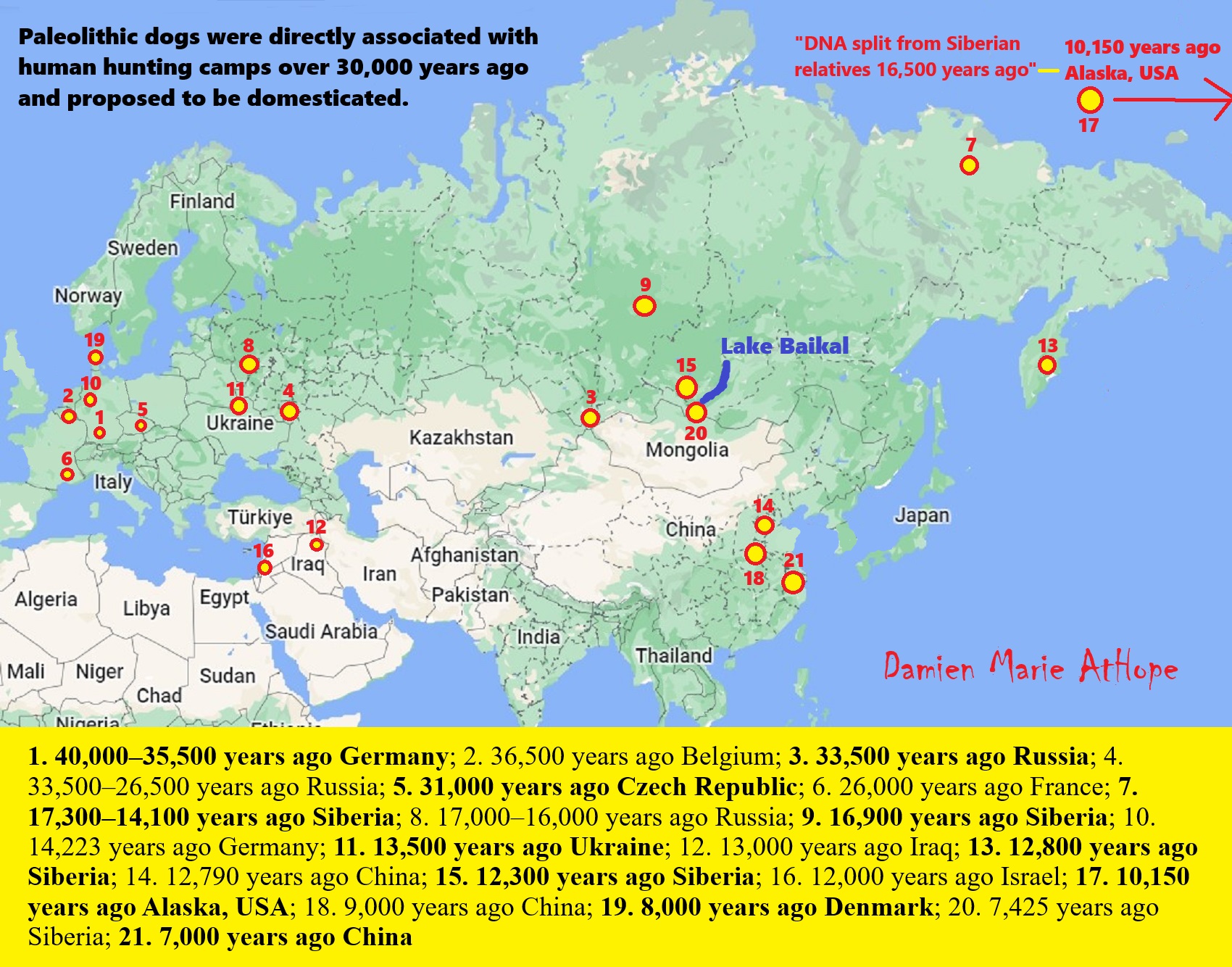

“ANE ancestry has spread throughout Eurasia and the Americas in various migrations since the Upper Paleolithic, and more than half of the world’s population today derives between 5 and 42% of their genomes from the Ancient North Eurasians. Significant ANE ancestry can be found in Native Americans, as well as in Europe, South Asia, Central Asia, and Siberia. It has been suggested that their mythology may have featured narratives shared by both Indo-European and some Native American cultures, such as the existence of a metaphysical world tree and a fable in which a dog guards the path to the afterlife.” ref

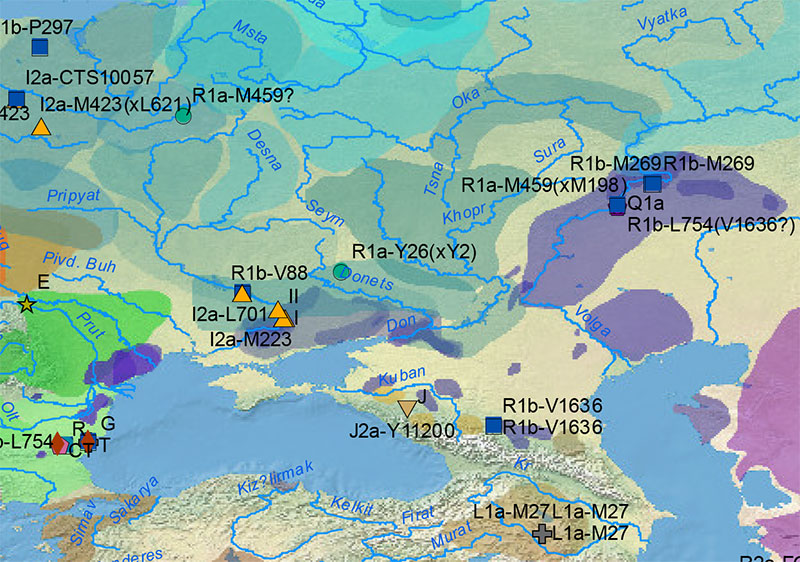

Eastern hunter-gatherer

“In archaeogenetics, eastern hunter-gatherer (EHG), sometimes east European hunter-gatherer or eastern European hunter-gatherer, is a distinct ancestral component that represents Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of Eastern Europe. The eastern hunter-gatherer genetic profile is mainly derived from Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) ancestry, which was introduced from Siberia, with a secondary and smaller admixture of European western hunter-gatherers (WHG). Still, the relationship between the ANE and EHG ancestral components is not yet well understood due to lack of samples that could bridge the spatiotemporal gap. During the Mesolithic, the EHGs inhabited an area stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Urals and downwards to the Pontic–Caspian steppe. Along with Scandinavian hunter-gatherers (SHG) and western hunter-gatherers (WHG), the EHGs constituted one of the three main genetic groups in the postglacial period of early Holocene Europe.” ref

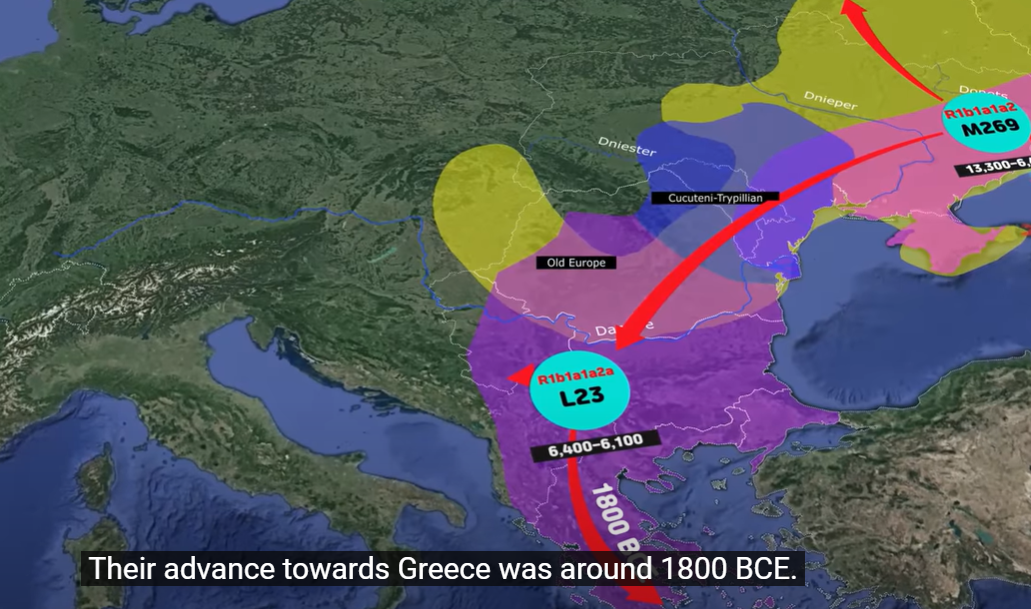

“The border between WHGs and EHGs ran roughly from the lower Danube, northward along the western forests of the Dnieper towards the western Baltic Sea. During the Neolithic and early Eneolithic, likely during the 4th millennium BC EHGs on the Pontic–Caspian steppe mixed with Caucasus hunter-gatherers (CHGs) with the resulting population, almost half-EHG and half-CHG, forming the genetic cluster known as Western Steppe Herder (WSH). WSH populations closely related to the people of the Yamnaya culture are supposed to have embarked on a massive migration leading to the spread of Indo-European languages throughout large parts of Eurasia.” ref

Caucasus hunter-gatherer

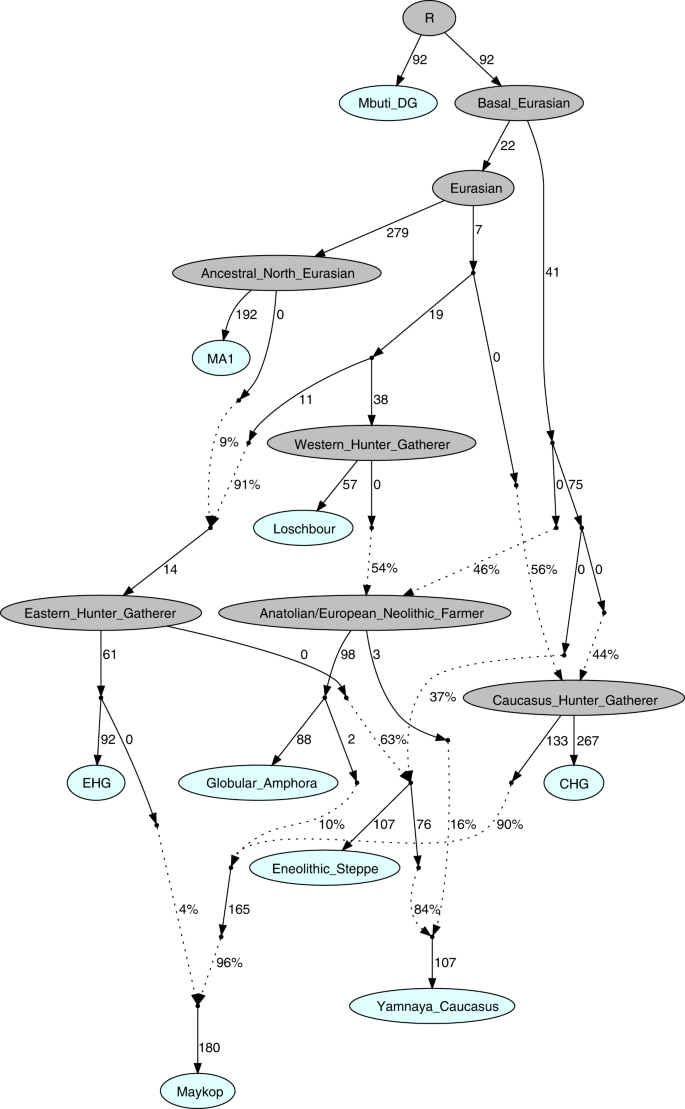

“Caucasus hunter-gatherer (CHG), also called Satsurblia cluster, is an anatomically modern human genetic lineage, first identified in a 2015 study, based on the population genetics of several modern Western Eurasian (European, Caucasian, and Near Eastern) populations. It represents an ancestry maximized in some Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic hunter-gatherer groups in the Caucasus. These groups are also very closely related to Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and Neolithic farmers in the Iranian Plateau, who are sometimes included within the CHG group. Ancestry that is closely related to CHG-Iranian Neolithic farmers is also known from further east, including from the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex and the Harappan/Indus Valley Civilisation. Caucasus hunter-gatherers and Eastern hunter-gatherers are ancestral in roughly equal proportions to the Western Steppe Herders (WSH), who were widely spread across Europe and Asia beginning during the Chalcolithic.” ref

“The CHG lineage is suggested to have diverged from the ancestor of Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs) probably during the Last Glacial Maximum (sometime between 45,000 to 26,000 years ago). They further separated from the Anatolian hunter-gatherer (AHG) lineage later, suggested to around 25,000 years ago during the late LGM period. The Caucasus hunter-gatherers managed to survive in isolation since the late LGM period as a distinct population, and display high genetic affinities to Mesolithic and Neolithic populations on the Iranian plateau, such as Neolithic specimens found in Ganj Dareh. The CHG display higher genetic affinities to European and Anatolian groups than Iranian hunter-gatherers do, suggesting a possible cline and geneflow into the CHG and less into Mesolithic and Neolithic Iranian groups.” ref

“Lazaridis et. al (2016) models the CHG as a mixture of Neolithic Iranians, Western Hunter-Gatherers, and Eastern Hunter-Gatherers. In addition, the CHG cluster with early Iranian farmers, who significantly do not share alleles with early Levantine farmers. An alternative model without the need of significant amounts of ANE ancestry has been presented by Vallini et al. (2024), suggesting that the initial Iranian hunter-gatherer-like population, which is basal to the CHG formed primarily from a deep Ancient West Eurasian lineage (‘WEC2’, c. 72%), and from varying degrees of Ancient East Eurasian (c. 10%) and Basal Eurasian (c. 18%) components. The Ancient West Eurasian component associated with Iranian hunter-gatherers (WEC2) is inferred to have diverged from the West Eurasian Core lineage (represented by Kostenki-14; WEC), with the WEC2 component staying in the region of the Iranian Plateau, while the proper WEC component expanded into Europe.” ref

“Irving-Pease et. al (2024) models CHG as being derived from an Out of Africa population that split into basal Northern Europeans and West Asians. The latter was where CHG originated from. At the beginning of the Neolithic, at c. 8000 BC, they were probably distributed across western Iran and the Caucasus, and people similar to northern Caucasus and Iranian plateau hunter-gatherers arrived before 6000 BC in Pakistan and north-west India. A roughly equal merger between the CHG and Eastern Hunter-Gatherers in the Pontic–Caspian steppe resulted in the formation of the Western Steppe Herders (WSHs). The WSHs formed the Yamnaya culture and subsequently expanded massively throughout Europe during the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age c. 3000—2000 BCE. Caucasus hunter-gatherer/Iranian-like ancestry, was first reported as maximized in hunter-gatherers from the South Caucasus and early herders/farmers in northwestern Iran, particularly the Zagros, hence the label “CHG/Iranian.” ref

Epigravettian

“The Epigravettian (Greek: epi “above, on top of,” and Gravettian ) was one of the last archaeological industries and cultures of the European Upper Paleolithic . It emerged after the Last Glacial Maximum around ~21,000 years ago or 19,050 BCE. It succeeds the Gravettian culture in Italy. Initially named Tardigravettian (Late Gravettian) in 1964 by Georges Laplace in reference to several lithic industries found in Italy, it was later renamed in order to better emphasize its independent character. Three subphases, the Early Epigravettian (20,000 to 16,000 years ago), the Evolved Epigravettian (16,000 to 14,000 years ago), and the Final Epigravettian (14,000 to 8,000 years ago) have been established, which were further subdivided and reclassified. In this sense, the Epigravettian is simply the Gravettian after ~21,000 years ago, when the Solutrean had replaced the Gravettian in most of France and Spain. Epigravettian Venus like artifacts, maybe 24,000 – 18,000 years ago. An Epigravettian ceramic figurine of a horse or deer, Vela Spila, Croatia, is dated to 15,400-14,600 years ago.” ref

“Several Epigravettian cultural centers have developed contemporaneously after 22,000 years years ago in Europe. These range across southern, central, and most of eastern Europe, including southwestern France, Italy, Southeast Europe , the Caucasus, Ukraine, and Western Russia to the banks of the Volga River. Its lithic complex was first documented at numerous sites in Italy. Great geographical and local variability of the facies is present, however all sites are characterized by the predominance of microliths, such as backed blades, backed points, and bladelets with retouched end. The Epigravettian is the last stage of the Upper Paleolithic succeeded by Mesolithic cultures after 10,000 years ago. In a genetic study published in Nature in May 2016, the remains of an Epigravettian male from Ripari Villabruna in Italy were examined.” ref

“He carried the paternal haplogroup R1b1 and the maternal haplogroup U5b . An Epigravettian from the Satsurblia Cave in Georgia , who was examined in a previous study, has been found to be carrying the paternal haplogroup J1 and the maternal haplogroup K3. Analysis of Epigravettian producing individuals in Italy indicates that they not closely related to earlier Gravettian-producing populations of the peninsula, and instead belong to the Villabruna genetic cluster . This group is more closely related to ancient and modern peoples in the Middle East and the Caucasus than earlier European Cro-Magnons . Epigravettian peoples belonging to the Western Hunter Gatherer genetic cluster expanded across Western Europe at the end of the Pleistocene, largely replacing the producers of the Magdalenian culture that previously dominated the region.” ref

“Magdalenian cultures (Pre-R1b Y-DNA Europe) are later cultures of the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic in western Europe. They date from around 17,000 to 12,000 years ago. It is named after the type site of La Madeleine, a rock shelter located in the Vézère valley, commune of Tursac, in France’s Dordogne department. The Magdalenian is associated with reindeer hunters, although Magdalenian sites contain extensive evidence for the hunting of red deer, horses, and other large mammals present in Europe toward the end of the last glacial period. The culture was geographically widespread, and later Magdalenian sites stretched from Portugal in the west to Poland in the east, and as far north as France, the Channel Islands, England, and Wales. Besides La Madeleine, the chief stations of the Magdalenian are Les Eyzies, Laugerie-Basse, and Gorges d’Enfer in the Dordogne; Grotte du Placard in Charente and others in south-west France.” ref

“Magdalenian peoples produced a wide variety of art, including figurines and cave paintings. Evidence has been found suggesting that Magdalenian peoples regularly engaged in (probably ritualistic) cannibalism along with producing skull cups. Genetic studies indicate that the Magdalenian peoples were largely descended from earlier Western European Cro-Magnon groups like the Gravettians that were present in Western Europe over 30,000 years ago prior to the Last Glacial Maximum, who had retreated to southwestern Europe during the LGM. Madgalenian peoples were largely replaced and, in some areas, absorbed by Epigravettian producing groups of Villabruna/Western Hunter Gatherer ancestry at the end of the Pleistocene.” ref

“The genes of seven Magdalenians, the El Miron Cluster in Iberia, have shown a close relationship to a population who had lived in Northern Europe some 20,000 years previously. The analyses suggested that 70-80% of the ancestry of these individuals was from the population represented by Goyet Q116-1, associated with the Aurignacian culture of about 35,000 BP, from the Goyet Caves in modern Belgium. It has also been found that Magdalenians are also closely related to western Gravettians who inhabited France and Spain prior to the Last Glacial Maximum. The 15,000-year-old GoyetQ2 individual from Goyet Caves is often used as a proxy for Magdalenian ancestry.” ref

“Analysis of genomes of GoyetQ2-related Magdalenians suggest that, like earlier Cro-Magnon groups, they probably had a relatively dark skin tone compared to modern Europeans. A 2023 study proposed that relative to earlier Western European Cro-Magnon-related groups like Goyet Q116-1-related Aurignacian and the Western Gravettian-associated Fournol cluster, the Goyet-Q2-related Magdalenians appear to have carried significant (~30% ancestry) from the Villabruna cluster (thought to be of southeastern European origin, and sharing affinities to West Asian peoples not found in earlier European hunter-gatherers) associated with the Epigravettian.” ref

“The three samples of Y-DNA included two samples of haplogroup I and one sample of HIJK. All samples of mtDNA belonged to U, including five samples of U8b and one sample of U5b. Around 14-12,000 years ago, the Western Hunter-Gatherer cluster (which predominantly descended from the Villabruna cluster, with possible ancestry related to the Goyet-Q2 cluster), expanded northwards across the Alps, largely replacing the Goyet-Q2 cluster associated Magdalenian groups in Western Europe. In France and Spain, significant GoyetQ2-related ancestry persisted into the Mesolithic and Neolithic, with some Neolithic individuals in France and Spain largely of Early European Farmer descent showing significant GoyetQ2 ancestry.” ref

Western hunter-gatherer

“In archaeogenetics, western hunter-gatherer (WHG, also known as west European hunter-gatherer, western European hunter-gatherer or Oberkassel cluster) (c. 15,000~5,000 years ago) is a distinct ancestral component of modern Europeans, representing descent from a population of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who scattered over western, southern and central Europe, from the British Isles in the west to the Carpathians in the east, following the retreat of the ice sheet of the Last Glacial Maximum. It is closely associated and sometimes considered synonymous with the concept of the Villabruna cluster, named after Ripari Villabruna cave in Italy, known from the terminal Pleistocene of Europe, which is largely ancestral to later WHG populations.” ref

“WHGs share a closer genetic relationship to ancient and modern peoples in the Middle East and the Caucasus than earlier European hunter-gatherers. Their precise relationships to other groups are somewhat obscure, with their origin likely somewhere in southeast Europe or West Asia. They had expanded into the Italian and Iberian Peninsulas by approximately 19,000 years ago, and subsequently expanded across Western Europe at the end of the Pleistocene around 14-12,000 years ago, largely replacing the Magdalenians who previously dominated the region. The Magdalenians largely descended from earlier Western European Cro-Magnon groups that had arrived in the region over 30,000 years ago, prior to the Last Glacial Maximum.” ref

“WHGs constituted one of the main genetic groups in the postglacial period of early Holocene Europe, along with eastern hunter-gatherers (EHG) in Eastern Europe. The border between WHGs and EHGs ran roughly from the lower Danube, northward along the western forests of the Dnieper towards the western Baltic Sea. EHGs primarily consisted of a mixture of WHG-related and Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) ancestry. Scandinavia was inhabited by Scandinavian hunter-gatherers (SHGs), which were a mixture between WHG and EHG. In the Iberian Peninsula, early Holocene hunter-gathers consisted of a mixture of WHG and Magdalenian Cro-Magnon (GoyetQ2) ancestry.” ref

“Once the main population throughout Europe, the WHGs were largely replaced by successive expansions of Early European Farmers (EEFs) of Anatolian origin during the early Neolithic, who generally carried a minor amount of WHG ancestry due to admixture with WHG groups during their European expansion. Among modern-day populations, WHG ancestry is most common among populations of the eastern Baltic region. Western hunter-gatherers (WHG) are recognised as a distinct ancestral component contributing to the ancestry of most modern Europeans. Most Europeans can be modeled as a mixture of WHG, EEF, and WSH from the Pontic–Caspian steppe. WHGs also contributed ancestry to other ancient groups such as Early European Farmers (EEF), who were, however, mostly of Anatolian descent. With the Neolithic expansion, EEF came to dominate the gene pool in most parts of Europe, although WHG ancestry had a resurgence in Western Europe from the Early Neolithic to the Middle Neolithic.” ref

“WHGs represent a major population shift within Europe at the end of the Ice Age, probably a population expansion into continental Europe, from Southeastern European or West Asian refugia. It is thought that their ancestors separated from eastern Eurasians around 40,000 years ago, and from Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) prior to 24,000 years ago (the estimated age date of the Mal’ta boy). This date was subsequently put further back in time by the findings of the Yana Rhinoceros Horn Site to around 38,000 years ago, shortly after the divergence of West-Eurasian and East-Eurasian lineages. Vallini et al. 2022 argues that the dispersal and split patterns of West Eurasian lineages was not earlier than c. 38,000 years ago, with older Initial Upper Paleolithic European specimens, such as those found in the Zlaty Kun, Peștera cu Oase and Bacho Kiro caves, being unrelated to Western hunter-gatherers but closer to Ancient East Eurasians or basal to both.” ref

“The relationships of the WHG/Villabruna cluster to other Paleolithic human groups in Europe and West Asia are obscure and subject to conflicting intepretations. A 2022 study proposed that the WHG/Villabruna population genetically diverged from hunter-gatherers in the Middle East and the Caucasus around 26,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum. WHG genomes display higher affinity for ancient and modern Middle Eastern populations when compared against earlier Paleolithic Europeans such as Gravettians. The affinity for ancient Middle Eastern populations in Europe increased after the Last Glacial Maximum, correlating with the expansion of WHG (Villabruna or Oberkassel) ancestry. There is also evidence for bi-directional geneflow between WHG and Middle Eastern populations as early as 15,000 years ago.” ref

“WHG associated remains belonged primarily to the human Y-chromosome haplogroups I-M170 with a lower frequency of C-F3393 (specifically the clade C-V20/C1a2), which has been found commonly among earlier Paleolithic European remains such as Kostenki-14 and Sungir. The paternal haplogroup C-V20 can still be found in men living in modern Spain, attesting to this lineage’s longstanding presence in Western Europe. Their mitochondrial chromosomes belonged primarily to haplogroup U5. A 2023 study proposed that the Villabruna cluster emerged from the mixing in roughly equal proportions of a divergent West Eurasian ancestry with a West Eurasian ancestry closely related to the 35,000-year-old BK1653 individual from Bacho Kiro Cave in Bulgaria, with this BK1653-related ancestry also significantly (~59%) ancestral to the Věstonice cluster characteristic of eastern Gravettian producing Cro-Magnon groups, which may reflect shared ancestry in the Balkan region.” ref

“The earliest known individuals of predominantly WHG/Villabruna ancestry in Europe are known from Italy, dating to around 17,000 years ago, though an individual from El Mirón cave in northern Spain with 43% Villabruna ancestry is known from 19,000 years ago. Early WHG/Villabruna populations are associated with the Epigravettian archaeological culture, which largely replaced populations associated with the Magdalenian culture about 14,000 years ago (the ancestry of Magdalenian-associated Goyet-Q2 cluster primarily descended from the earlier Solutrean, and western Gravettian-producing groups in France and Spain). A 2023 study found that relative to earlier Western European Cro-Magnon populations like the Gravettians, that Magdalenian-associated Goyet-Q2 cluster carried significant (~30%) Villabruna ancestry even prior to the major expansion of WHG-related groups north of the Alps.” ref

“This study also found that relative to earlier members of the Villabruna cluster from Italy, WHG-related groups which appeared north of the Alps beginning around 14,000 years ago carried around 25% ancestry from the Goyet-Q2 cluster (or alternatively 10% from the western Gravettian associated Fournol cluster). This paper proposed that WHG should be named the Oberkassel cluster, after one of the oldest WHG individuals found north of the Alps. The study suggests that Oberkassel ancestry was mostly already formed before expanding, possibly around the west side of the Alps, to Western and Central Europe and Britain, where sampled WHG individuals are genetically homogeneous. This is in contrast to the arrival of Villabruna and Oberkassel ancestry to Iberia, which seems to have involved repeated admixture events with local populations carrying high levels of Goyet-Q2 ancestry. This, and the survival of specific Y-DNA haplogroup C1 clades previously observed among early European hunter-gatherers, suggests relatively higher genetic continuity in southwest Europe during this period.” ref

“The WHG were also found to have contributed ancestry to populations on the borders of Europe such as early Anatolian farmers and Ancient Northwestern Africans, as well as other European groups such as eastern hunter-gatherers. The relationship of WHGs to the EHGs remains inconclusive. EHGs are modeled to derive varying degrees of ancestry from a WHG-related lineage, ranging from merely 25% to up to 91%, with the remainder being linked to geneflow from Paleolithic Siberians (ANE) and perhaps Caucasus hunter-gatherers. Another lineage known as the Scandinavian hunter-gatherers (SHGs) were found to be a mix of EHGs and WHGs. In the Iberian Peninsula early Holocene hunter-gathers consisted of populations with a mixture of WHG and Magdalenian Cro-Magnon (GoyetQ2) ancestry.” ref

“People of the Mesolithic Kunda culture and the Narva culture of the eastern Baltic were a mix of WHG and EHG, showing the closest affinity with WHG. Samples from the Ukrainian Mesolithic and Neolithic were found to cluster tightly together between WHG and EHG, suggesting genetic continuity in the Dnieper Rapids for a period of 4,000 years. The Ukrainian samples belonged exclusively to the maternal haplogroup U, which is found in around 80% of all European hunter-gatherer samples. People of the Pit–Comb Ware culture (CCC) of the eastern Baltic were closely related to EHG. Unlike most WHGs, the WHGs of the eastern Baltic did not receive European farmer admixture during the Neolithic. Modern populations of the eastern Baltic thus harbor a larger amount of WHG ancestry than any other population in Europe.” ref

“SHGs have been found to contain a mix of WHG components who had likely migrated into Scandinavia from the south, and EHGs who had later migrated into Scandinavia from the northeast along the Norwegian coast. This hypothesis is supported by evidence that SHGs from western and northern Scandinavia had less WHG ancestry (ca 51%) than individuals from eastern Scandinavia (ca. 62%). The WHGs who entered Scandinavia are believed to have belonged to the Ahrensburg culture. EHGs and WHGs displayed lower allele frequencies of SLC45A2 and SLC24A5, which cause depigmentation, and OCA/Herc2, which causes light eye color, than SHGs.” ref

“The DNA of eleven WHGs from the Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic in Western Europe, Central Europe, and the Balkans was analyzed, with regards to their Y-DNA haplogroups and mtDNA haplogroups. The analysis suggested that WHGs were once widely distributed from the Atlantic coast in the West, to Sicily in the South, to the Balkans in the Southeast, for more than six thousand years. The study also included an analysis of a large number of individuals of prehistoric Eastern Europe. Thirty-seven samples were collected from Mesolithic and Neolithic Ukraine (9500-6000 BCE). These were determined to be an intermediate between EHG and SHG, although WHG ancestry in this population increased during the Neolithic. Samples of Y-DNA extracted from these individuals belonged exclusively to R haplotypes (particularly subclades of R1b1) and I haplotypes (particularly subclades of I2). mtDNA belonged almost exclusively to U (particularly subclades of U5 and U4).” ref

“A large number of individuals from the Zvejnieki burial ground, which mostly belonged to the Kunda culture and Narva culture in the eastern Baltic, were analyzed. These individuals were mostly of WHG descent in the earlier phases, but over time EHG ancestry became predominant. The Y-DNA of this site belonged almost exclusively to haplotypes of haplogroup R1b1a1a and I2a1. The mtDNA belonged exclusively to haplogroup U (particularly subclades of U2, U4 and U5). Forty individuals from three sites of the Iron Gates Mesolithic in the Balkans were also analyzed. These individuals were estimated to be of 85% WHG and 15% EHG descent. The males at these sites carried exclusively haplogroup R1b1a and I (mostly subclades of I2a) haplotypes. mtDNA belonged mostly to U (particularly subclades of U5 and U4). People of the Balkan Neolithic were found to harbor 98% Anatolian ancestry and 2% WHG ancestry. By the Chalcolithic, people of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture were found to harbor about 20% hunter-gatherer ancestry, which was intermediate between EHG and WHG. People of the Globular Amphora culture were found to harbor ca. 25% WHG ancestry, which is significantly higher than Middle Neolithic groups of Central Europe.” ref

Scandinavian hunter-gatherer

“In archaeogenetics, the term Scandinavian hunter-gatherer (SHG) is the name given to a distinct ancestral component that represents descent from Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of Scandinavia. Genetic studies suggest that the SHGs were a mix of western hunter-gatherers (WHGs) initially populating Scandinavia from the south during the Holocene, and eastern hunter-gatherers (EHGs), who later entered Scandinavia from the north along the Norwegian coast. During the Neolithic, they admixed further with Early European Farmers (EEFs) and Western Steppe Herders (WSHs). Genetic continuity has been detected between the SHGs and members of the Pitted Ware culture (PWC), and to a certain degree, between SHGs and modern northern Europeans. The Sámi, on the other hand, have been found to be completely unrelated to the PWC.” ref

“Scandinavian hunter-gatherers (SHG) were identified as a distinct ancestral component by Lazaridis et al. (2014). A number of remains examined at Motala, Sweden, and a separate group of remains from 5,000 year-old hunter-gatherers of the Pitted Ware culture (PWC), were identified as belonging to SHG. The study found that an SHG individual from Motala (‘Motala12’) could be successfully modelled as being of c. 81% western hunter-gatherer (WHG) ancestry, and c. 19% Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) ancestry. Haak et al. (2015) examined the remains of six SHGs buried at Motala between ca. 6000 BCE and 5700 BCE. Of the four males surveyed, three carried the paternal haplogroup I2a1 or various subclades of it, while the other carried I2c. With regard to mtDNA, four individuals carried subclades of U5a, while two carried U2e1.” ref

“The study found SHGs to constitute one of the three main hunter-gatherer populations of Europe during the Mesolithic. The two other groups were WHGs and eastern hunter-gatherers (EHG). EHGs were found to be an ANE-derived population with significant admixture from a WHG-like source. SHGs formed a distinct cluster between WHG and EHG, and the admixture model proposed by Lazaridis et al. could be successfully replaced with a model that takes EHG as the source population for the ANE-like ancestry, with an admixture ratio of ~65% (WHG): ~35% (EHG). SHGs living between 6000 BCE and 3000 BCE were found to be largely genetically homogeneous, with little admixture occurring among them during this period. EHGs were found to be more closely related to SHGs than WHGs.” ref

“Mathieson et al. (2015) subjected the six SHGs from Motala to further analysis. SHGs appeared to have persisted in Scandinavia until after 5,000 years ago. The Motala SHGs were found to be closely related to WHGs. Lazaridis et al. (2016) confirmed SHGs to be a mix of EHGs (~43%) and WHGs (~57%). WHGs were modeled as descendants of the Upper Paleolithic people (Cro-Magnon) of the Grotte du Bichon in Switzerland with minor additional EHG admixture (~7%). EHGs derived c. 75% of their ancestry from ANEs. Günther et al. (2018) examined the remains of seven SHGs. All three samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to subclades of I2. With respects to mtDNA, four samples belonged to U5a1 haplotypes, while three samples belonged U4a2 haplotypes. All samples from western and northern Scandinavia carried U5a1 haplotypes, while all the samples from eastern Scandinavia except from one carried U4a2 haplotypes.” ref

“The authors of the study suggested that SHGs were descended from a WHG population that had entered Scandinavia from the south, and an EHG population which had entered Scandinavia from the northeast along the coast. The WHGs who entered Scandinavia are believed to have belonged to the Ahrensburg culture. These WHGs and EHGs had subsequently mixed, and the SHGs gradually developed their distinct character. The SHGs from western and northern Scandinavia had more EHG ancestry (c. 49%) than individuals from eastern Scandinavia (c. 38%). The SHGs were found to have a genetic adaptation to high latitude environments, including high frequencies of low pigmentation variants and genes designed for adaptation to the cold and physical performance. SHGs displayed a high frequency of the depigmentation alleles SLC45A2 and SLC24A5, and the OCA/Herc2, which affects eye pigmentation. These genes were much less common among WHGs and EHGs. A surprising continuity was displayed between SHGs and modern populations of Northern Europe in certain respects. Most notably, the presence of the protein TMEM131 among SHGs and modern Northern Europeans was detected. This protein may be involved in long-term adaptation to the cold.” ref

“In a genetic study published in Nature Communications in January 2018, the remains of an SHG female at Motala, Sweden, between 5750 BCE and 5650 BCE was analyzed. She was found to be carrying U5a2d and “substantial ANE ancestry.” The study found that Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of the eastern Baltic also carried high frequencies of the HERC2 allele, and increased frequencies of the SLC45A2 and SLC24A5 alleles. They, however, harbored less EHG ancestry than SHGs. Genetic continuity between the SHGs and the Pitted Ware culture of the Neolithic was detected. The results further underpinned the previous suggestion that SHGs were descended from the northward migration of WHGs and a subsequent southward migration of EHGs. A certain degree of continuity between SHGs and northern Europeans was detected.” ref

“A study published in Nature in February 2018 included an analysis of a large number of individuals of prehistoric Eastern Europe. Thirty-seven samples were collected from Mesolithic and Neolithic Ukraine (9500–6000 BCE). These were determined to be an intermediate between EHG and SHG. Samples of Y-DNA extracted from these individuals belonged exclusively to R haplotypes (particularly subclades of R1b1 and R1a)) and I haplotypes (particularly subclades of I2). mtDNA belonged almost exclusively to U (particularly subclades of U5 and U4). According to Mathieson et al. (2015), 50% of Scandinavian Hunter Gatherers from Motala carried the derived variant of EDAR-V370A. This variant is typical of modern East Asian populations, and is known to affect dental morphology and hair texture, and also chin protrusion and ear morphology, as well as other facial features.” ref

“The authors did not detect East Asian ancestry in the Scandinavian Hunter Gatherers, and speculated that this gene might not have originated in East Asia, as is commonly believed. However, more recent research incorporating ancient Northeast Asian samples has confirmed that EDAR-V370A originated in Northeast Asia, and spread to West Eurasian populations such as Motala in the Holocene period. Mathieson et al. (2015) also reported: “A second surprise is that, unlike closely related western hunter-gatherers, the Motala samples have predominantly derived pigmentation alleles at SLC45A2 and SLC24A5. The study by Günther et al. (2018) further discovered that SHGs “show a combination of eye color varying from blue to light brown and light skin pigmentation. This is strikingly different from the WHGs—who have been suggested to have the specific combination of blue eyes and dark skin and EHGs—who have been suggested to be brown-eyed and light-skinned.” ref

“Four SHGs from the study yielded diverse eye and hair pigmentation predictions: one individual (SF12) was predicted to be most likely to have had dark hair and blue eyes; a second individual (Hum2) most likely had dark hair and brown eyes; a third (SF9) was predicted to have had light hair and brown eyes; and a fourth individual (SBj) was predicted to have had light hair, with the most likely hair colour being blonde, and blue eyes. Of the SHGs from Motala, four were probably dark-haired, and two others were probably light-haired, and may have been blond. In addition, all of the six SHGs from Motala had high probabilities of being blue-eyed. Both light and dark skin pigmentation alleles are found at intermediate frequencies in the Scandinavian Hunter Gatherers sampled, but only one individual had exclusively light-skin variants of two different SNPs.” ref

“The study found that depigmentation variants of genes for light skin pigmentation (SLC24A5, SLC45A2) and blue eye pigmentation (OCA2/HERC2) are found at high frequency in SHGs relative to WHGs and EHGs, which the study suggests cannot be explained simply as a result of the admixture of WHGs and EHGs. The study argues that these allele frequencies must have continued to increase in SHGs after admixture, which was probably caused by environmental adaptation to high latitudes. On the basis of archaeological and genetic evidence, the Swedish archaeologist Oscar D. Nilsson has made forensic reconstructions of both male and female SHGs.” ref

“Light skin is a human skin color that has a low level of eumelanin pigmentation as an adaptation to environments of low UV radiation. Due to the migrations of people in recent centuries, light-skinned populations today are found all over the world. Light skin is most commonly found amongst the native populations of Europe, East Asia, West Asia, Central Asia, Siberia, and North Africa as measured through skin reflectance. People with light skin pigmentation are often referred to as “white“ although these usages can be ambiguous in some countries where they are used to refer specifically to certain ethnic groups or populations.” ref

“Humans with light skin pigmentation have skin with low amounts of eumelanin, and possess fewer melanosomes than humans with dark skin pigmentation. Light skin provides better absorption qualities of ultraviolet radiation, which helps the body to synthesize higher amounts of vitamin D for bodily processes such as calcium development. On the other hand, light-skinned people who live near the equator, where there is abundant sunlight, are at an increased risk of folate depletion. As a consequence of folate depletion, they are at a higher risk of DNA damage, birth defects, and numerous types of cancers, especially skin cancer.” ref

“Humans with darker skin who live further from the tropics may have lower vitamin D levels, which can also lead to health complications, both physical and mental, including a greater risk of developing schizophrenia. These two observations form the “vitamin D–folate hypothesis,” which attempts to explain why populations that migrated away from the tropics into areas of low UV radiation evolved to have light skin pigmentation. The distribution of light-skinned populations is highly correlated with the low ultraviolet radiation levels of the regions inhabited by them. Historically, light-skinned populations almost exclusively lived far from the equator, in high-latitude areas with low sunlight intensity.” ref

“It is generally accepted that dark skin evolved as a protection against the effect of UV radiation; eumelanin protects against both folate depletion and direct damage to DNA. This accounts for the dark skin pigmentation of Homo sapiens during their development in Africa; the major migrations out of Africa to colonize the rest of the world were also dark-skinned. It is widely supposed that light skin pigmentation developed due to the importance of maintaining vitamin D3 production in the skin. Strong selective pressure would be expected for the evolution of light skin in areas of low UV radiation. After the ancestors of West Eurasians and East Eurasians diverged more than 40,000 years ago, lighter skin tones evolved independently in a subset of each of the two populations. In West Eurasians, the A111T allele of the rs1426654 polymorphism in the pigmentation gene SLC24A5 has the largest skin-lightening effect and is widespread in Europe, South Asia, Central Asia, the Near East, and North Africa.” ref

“In a 2013 study, Canfield et al. established that SLC24A5 sits in a block of haplotypes, one of which (C11) is shared by virtually all chromosomes that bear the A111T variant. This “equivalence” between C11 and A111T indicates that all people who carry this skin-lightening allele descend from a common origin: a single carrier who lived most likely “between the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent.” Canfield et al. attempted to date the A111T mutation but only constrained the age range to before the Neolithic. However, a second study from the same year (Basu Mallick et al.) estimated the coalescent age (split date) for this allele to be between ~28,000 and ~22,000 years ago.” ref

“The second most important skin-lightening factor in West Eurasians is the depigmenting allele F374 of the rs16891982 polymorphism located in the melanin-synthesis gene SLC45A2. From its low haplotype diversity, Yuasa et al. (2006) likewise concluded that this mutation (L374F) “occurred only once in the ancestry of Caucasians.” Summarising these studies, Hanel and Carlberg (2020) decided that the alleles of the two genes SLC24A5 and SLC45A2, which are most associated with lighter skin color in modern Europeans, originated in West Asia about 22,000 to 28,000 years ago and these two mutations each arose in a single carrier. This is consistent with Jones et al. (2015), who reconstructed the relationship between Near Eastern Neolithic farmers and Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers: two populations that carried the light-skin variant of SLC24A5.” ref

“Analyzing newly sequenced ancient genomes, Jones et al. estimated the split date at ~24,000 years ago and localized the separation to somewhere south of the Caucasus. However, a coalescent analysis of this allele by Crawford et al. (2017) gave a more narrowly constrained, and earlier, split date of ~29,000 years ago (with a 95% confidence window from 28,000 to 31,000 years ago). The light-skin variants of SLC24A5 and SLC45A2 were present in Anatolia by 9,000 years ago, where they became associated with the Neolithic Revolution. From here, their carriers spread Neolithic farming across Europe. Lighter skin and blond hair also evolved in the Ancient North Eurasian population.” ref

“A further wave of lighter-skinned populations across Europe (and elsewhere) is associated with the Yamnaya culture and the Indo-European migrations bearing Ancient North Eurasian ancestry and the KITLG allele for blond hair. Furthermore, the SLC24A5 gene linked with light pigmentation in Europeans was introduced into East Africa from Europe over five thousand years ago. These alleles can now be found in the San, Ethiopians, and Tanzanian populations with Afro-Asiatic ancestry. The SLC24A5 in Ethiopia maintains a substantial frequency with Semitic and Cushitic speaking populations, compared with Omotic, Nilotic, or Niger-Congo speaking groups. It is inferred that it may have arrived into the region via migration from the Levant, which is also supported by linguistic evidence. In the San people, it was acquired from interactions with Eastern African pastoralists. Meanwhile, in the case of East Asia and the Americas, a variation of the MFSD12 gene is responsible for lighter skin color. The modern association between skin tone and latitude is thus a relatively recent development.” ref

“According to Crawford et al. (2017), most of the genetic variants associated with light and dark pigmentation appear to have originated more than 300,000 years ago. African, South Asian, and Australo-Melanesian populations also carry derived alleles for dark skin pigmentation that are not found in Europeans or East Asians. Huang et al. (2021) found the existence of “selective pressure on light pigmentation in the ancestral population of Europeans and East Asians”, prior to their divergence from each other. Skin pigmentation was also found to be affected by directional selection towards darker skin among Africans, as well as lighter skin among Eurasians.” ref

“Crawford et al. (2017) similarly found evidence for selection towards light pigmentation prior to the divergence of West Eurasians and East Asians. The A111T mutation in the SLC24A5 gene predominates in populations with Western Eurasian ancestry. The geographical distribution shows that it is nearly fixed in all of Europe and most of the Middle East, extending east to some populations in present-day Pakistan and Northern India. It shows a latitudinal decline toward the Equator, with high frequencies in North Africa (80%), and intermediate (40−60%) in Ethiopia and Somalia.” ref

“Some authors have expressed caution regarding the skin pigmentation SNP predictions in early Paleolithic groups. According to Ju et al. (2021): “Relatively dark skin pigmentation in Early Upper Paleolithic Europe would be consistent with those populations being relatively poorly adapted to high-latitude conditions as a result of having recently migrated from lower latitudes. On the other hand, although we have shown that these populations carried few of the light pigmentation alleles that are segregating in present-day Europe, they may have carried different alleles that we cannot now detect. As an extreme example, Neanderthals and the Altai Denisovan individual show genetic scores that are in a similar range to Early Upper Paleolithic individuals, but it is highly plausible that these populations, who lived at high latitudes for hundreds of thousands of years, would have adapted independently to low UV levels. For this reason, we cannot confidently make statements about the skin pigmentation of ancient populations.” ref

“In 2015, it was discovered that 13,000-year-old samples of Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers (CHG) from Georgia carried the mutation and derived alleles for very fair-skinned pigmentation similar to Early Farmers (EF). This trait was said to have a relatively long history in Eurasia and risen to high frequency during the Neolithic expansion, with its origin probably predating the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM).” ref

“In the same year, a study found that genes contributing to fair skin were nearly fixed in the Anatolian Neolithic Farmers: “The second strongest signal in our analysis is at the derived allele of rs16891982 in SLC45A2, which contributes to light skin pigmentation and is almost fixed in present-day Europeans but occurred at much lower frequency in ancient populations. In contrast, the derived allele of SLC24A5 that is the other major determinant of light skin pigmentation in modern Europe, appears fixed in the Anatolian Neolithic, suggesting that its rapid increase in frequency to around 0.9 (90%) in Early Neolithic Europe was mostly due to migration.” ref

“In 2018, a study was released showing many late Mesolithic Scandinavians from 9,500 years ago in Northern Europe had blonde hair and light skin, which was in contrast to some of their contemporaries, the darker Western Hunter Gatherers (WHG). However, a 2024 paper found that phenotypically most of their studied WHG individuals carried the dark skin and blue eyes characteristic of WHGs, but some other WHGs in France they sequenced also had pale to intermediate skin pigmentation. Another entry in 2018, showed that the Eastern Hunter Gatherers (EHG), Scandinavian Hunter Gatherers (SHG), and the Baltic foragers, all had the derived alleles for light skin pigmentation.” ref

“A study on the populations of the Chalcolithic Levant (6,000-7,000 years ago), found that an allele rs1426654 in the SLC24A5 gene which is one of the most important determinants of light pigmentation in West Eurasians, was fixed for the derived variants in all Levant Chalcolithic samples, suggesting that the light skinned phenotype may have been common in the community. The individuals also had a high incidence of genomic markers associated with blue-eye color. A paper conducted by Fregel, Rosa et al. (2018) showed that in North Africa, Late Neolithic Moroccans had the European/Caucasus derived SLC24A5 mutation and other alleles and genes that predispose individuals to lighter skin and eye colours.” ref

Iberian hunter-gatherers

“The hunter-gatherers from the Iberian Peninsula carry a mix of two older types of genetic ancestry: one that dates back to the Last Glacial Maximum and was once maximized in individuals attributed to Magdalenian culture and another one that is found everywhere in western and central Europe and had replaced the Magdalenian lineage during the Early Holocene everywhere except the Iberian Peninsula,” explains Vanessa Villalba-Mouco of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, first author of the study. The researchers hope that ongoing efforts to decipher the genetic structure of late hunter-gatherer groups across Europe will help to even better understand Europe’s past and, in particular, the assimilation of a Neolithic way of life brought about by expanding farmers from the Near East during the Holocene.” ref

Ancient DNA from individuals spanning the last 8000 years helps clarify the history and prehistory of the Iberian Peninsula

“The paper published in Science focuses on slightly later time periods, and traces the population history of Iberia over the last 8000 years by analyzing ancient DNA from a huge number of individuals. The study, led by Harvard Medical School and the Broad Institute and including Haak and Villalba-Mouco, analyzed 271 ancient Iberians from the Mesolithic, Neolithic, Copper Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age, and historical periods. The large number of individuals allowed the team to make more detailed inferences about each time period than previously possible. The researchers found that during the transition to a sedentary farming life-style, hunter-gatherers in Iberia contributed subtly to the genetic make-up of newly arriving farmers from the Near East. “We can see that there must have been local mixture as the Iberian farmers also carry this dual signature of hunter-gatherer ancestry unique to Iberia,” explains Villalba-Mouco.” ref

“Between about 2500-2000 BCE, the researchers observed the replacement of 40% of Iberia’s ancestry and nearly 100% of its Y-chromosomes by people with ancestry from the Pontic Steppe, a region in what is today Ukraine and Russia. Interestingly, the findings show that in the Iron Age, “Steppe ancestry” had spread not only into Indo-European-speaking regions of Iberia but also into non-Indo-European-speaking ones, such as the region inhabited by the Basque. The researchers’ analysis suggests that present-day Basques most closely resemble a typical Iberian Iron Age population, including the influx of “Steppe ancestry,” but that they were not affected by subsequent genetic contributions that affected the rest of Iberia. This suggests that Basque speakers were equally affected genetically as other groups by the arrival of Steppe populations, but retained their language in any case. It was only after that time that they became relatively isolated genetically from the rest of the Iberian Peninsula.” ref

“Additionally, the researchers looked at historical periods, including times when Greek and later Roman settlements existed in Iberia. The researchers found that beginning at least in the Roman period, the ancestry of the peninsula was transformed by gene flow from North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean. They found that Greek and Roman settlements tended to be quite multiethnic, with individuals from the central and eastern Mediterranean and North Africa as well as locals, and that these interactions had lasting demographic as well as cultural impacts. “Beyond the specific insights about Iberia, this study serves as a model for how a high-resolution ancient DNA transect continuing into historical periods can be used to provide a detailed description of the formation of present-day populations,” explains Haak. “We hope that future use of similar strategies will provide equally valuable insights in other regions of the world.” ref

“An international team of researchers have analyzed ancient DNA from almost 300 individuals from the Iberian Peninsula, spanning more than 12,000 years, in two studies published concurrently in Current Biology and Science. The first study looked at hunter-gatherers and early farmers living in Iberia between 13,000 and 6000 years ago. The second looked at individuals from the region during all time periods over the last 8000 years. Together, the two papers greatly increase our knowledge about the population history of this unique region.” ref

“The Iberian Peninsula has long been thought of as an outlier in the population history of Europe, due to its unique climate and position on the far western edge of the continent. During the last Ice Age, Iberia remained relatively warm, allowing plants and animals – and possibly people – who were forced to retreat from much of the rest of Europe to continue living there. Similarly, over the last 8000 years, Iberia’s geographic location, rugged terrain, position on the Mediterranean coast and proximity to North Africa made it unique in comparison to other parts of Europe in its interactions with other regions. Two new studies, published concurrently in Current Biology and Science, analyze a total of almost 300 individuals who lived from about 13,000 to 400 years ago to give unprecedented clarity on the unique population history of the Iberian Peninsula.” ref

Iberian hunter-gatherers show two ancient Paleolithic lineages

“For the paper in Current Biology, led by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, researchers analyzed 11 hunter-gatherers and Neolithic individuals from Iberia. The oldest newly analyzed individuals are approximately 12,000 years old and were recovered from Balma Guilanyà in Spain. Earlier evidence had shown that, after the end of the last Ice Age, western and central Europe were dominated by hunter-gatherers with ancestry associated with an approximately 14,000-year-old individual from Villabruna, Italy. Italy is thought to have been a potential refuge for humans during the last Ice Age, like Iberia. The Villabruna-related ancestry largely replaced earlier ancestry in western and central Europe related to 19,000-15,000-year-old individuals associated with what is known as the Magdalenian cultural complex.” ref

“Interestingly, the findings of the current study show that both lineages were present in Iberian individuals dating back as far as 19,000 years ago. “We can confirm the survival of an additional Paleolithic lineage that dates back to the Late Ice Age in Iberia,” says Wolfgang Haak of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, senior author of the study. “This confirms the role of the Iberian Peninsula as a refuge during the Last Glacial Maximum, not only for fauna and flora but also for human populations.” This suggests that, far from being replaced by Villabruna-related individuals after the last Ice Age, hunter-gatherers in Iberia in fact already had ancestry from Magdalenian- and Villabruna-related sources. The discovery suggests an early connection between two potential refugia, resulting in a genetic ancestry that survived in later Iberian hunter-gatherers.” ref

Goyet-Q2 ancestry

“One of the most notable examples occurred during the Late Glacial, between the end of the LGM (~23,400 years ago) and the start of the Holocene epoch (~11,700 years ago). This shift is reflected in the ancestries associated with the ~15,090-year-old (IntCal20) Goyet Q2 individual, Belgium, and the ~14,010-year-old (IntCal20) Villabruna individual, Italy, in post-LGM Europe. We use these individuals as shorthand for the ancestries associated with them throughout the text. ‘Goyet Q2’ ancestry, which has previously been defined by the ~18,770-year-old (IntCal20) ‘El Mirón’ individual from Spain, has been identified in individuals associated with the Magdalenian culture, dating from ~20,500 to 14,000 years ago. This Goyet Q2/El Mirón ancestry has been suggested to represent a post-LGM expansion from southwestern European glacial refugia.” ref

“The ‘Villabruna’ ancestry, also broadly known as Western hunter-gatherers or WHG, consists of individuals dated from ~14,000 to 7,000 years ago associated with Epigravettian, Azilian/Federmesser, Epipalaeolithic, and Mesolithic cultures. The Villabruna ancestry is also associated with the observation that from ~14,000 years ago, all European individuals show some level of genetic affinity to present-day Near Eastern populations. The expansion in the geographic distribution of this ancestry also correlates with a period of rapid climate warming of the Late Glacial Interstadial (considered broadly equivalent to the onset of Greenland Interstadial 1 (GI-1), ~14,650 years ago) as well as cultural transitions from the Magdalenian/Late Upper Palaeolithic to the Azilian/Federmesser-Gruppen/Final Palaeolithic and has therefore been suggested to represent the movement of people into northwestern Europe after the LGM.” ref

“Interestingly, however, individuals with a mixture of Goyet Q2 and Villabruna ancestry appear in southern Europe from at least ~18,700 years ago—with the individual from El Mirón being the earliest identified thus far. The presence of individuals with admixed Goyet Q2 and Villabruna ancestry in southern Europe from the LGM onwards raises questions related to the fragmentation of populations into isolated refugia during the last Ice Age. It appears that both cultural and gene flow continued across the continent—although the nature of these processes and the mechanisms involved remain unclear. However, the presence of individuals with un-admixed Goyet Q2 ancestry in northern Europe until ~14,000 years ago also suggests some degree of sustained isolation throughout the LGM and into the Late Glacial. There is evidence of populations living in ice-marginal environments within northern Europe at the LGM and of long-distance movement of people from east to west north of the Alps, which has also been linked to the expansion of Magdalenian cultural groups. This evidence raises suggestions of Magdalenian populations with Goyet Q2 ancestry—who appear to have been cold-adapted hunter gatherers—retreating to northern Europe, perhaps due to climatic warming and the movement of prey species such as reindeer and horse. Conversely, more southerly regions such as northern Spain and Italy, where temperate prey species such as red deer persisted throughout the LGM and Late Glacial, may have provided greater ecological opportunities for population admixture.” ref

“Britain lies at the extreme northwest corner of the post-LGM expansion. With approximately two-thirds of the landmass covered by ice at the LGM and rapid deglaciation thereafter, substantial ecological and environmental change took place in the post-LGM landscape. As such, Britain offers a unique environmental context through which Late Upper Palaeolithic populations can be considered. By ~19,000 years ago, the British–Irish Ice Sheet was undergoing widespread melt, and by ~16,000 years ago, ice was absent from virtually all of England and Wales. Reindeer were present in southwest England by ~17,000 years ago, and habitats were dominated by open steppe–tundra vegetation. However, detailed consideration of Late Upper Palaeolithic sites in the United Kingdom and a series of radiocarbon dating programmes suggest that there is no evidence for post-LGM human recolonization of southwestern Britain before ~15,500 years ago.” ref

“As such, some regions of Britain were colonized before the rapid climate warming at the start of the Late Glacial Interstadial (~14,650 years ago). Accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) dating indicates that Britain was probably recolonized at a slightly later date than adjacent regions such as the Paris Basin and the Belgian Ardennes—thereby suggesting an expansion of people across the European continent1. Interestingly, the British Magdalenian (known locally as the Creswellian) appears to be very similar (both in terms of chronology and cultural expression/typology) to the Classic Hamburgian, found in the northern Netherlands and the lowlands of northern Germany and Poland. However, understanding the expansion of post-LGM populations into and within the British Isles is hindered by a relative paucity of preserved archaeological remains suitable for dating. As such, the exact nature of human occupation of Late Upper Palaeolithic Britain remains unclear and we have relatively little knowledge of the earliest postglacial populations in Britain.” ref

“Whilst the genetics of Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Age individuals from Britain have recently been explored, no genetic data have yet been generated for British Palaeolithic individuals, due in part to the scarcity of human skeletal material available from Late Pleistocene Britain. To date, modern human skeletal remains have been recovered from only six Upper Palaeolithic sites. Nonetheless, these rare samples are crucial for our understanding of human populations across post-LGM Europe due to Britain’s location on the most northwesterly fringe of the European continent. Mesolithic British populations have been identified genetically as WHGs (Villabruna ancestry), indicating that this genetic ancestry spread to the most northwesterly area of early Holocene Europe by at least ~10,500 years ago.” ref

“What remains unclear, however, is when this ancestry first arrived in Britain and, additionally, what the genetic ancestry of Palaeolithic populations in Britain may have been. Given the previous association of Goyet Q2 ancestry with Magdalenian cultures across Europe and the similarities between the Creswellian and the Classic Hamburgian cultures, it could be hypothesized that British Late Upper Palaeolithic populations would also fall within the Goyet Q2 genetic cluster. To address these questions and expand our knowledge of the genetic makeup of Europe after the LGM, we investigate here the genetic characteristics of Late Upper Palaeolithic Britain through ancient DNA analyses of human remains from two archaeological sites in England and Wales.” ref

Anatolian hunter-gatherers

“Anatolian hunter-gatherer (AHG) is a distinct anatomically modern human archaeogenetic lineage, first identified in a 2019 study based on the remains of a single Epipaleolithic individual found in central Anatolia, radiocarbon dated to around 13,500 BCE. A population related to this individual was the main source of the ancestry of later Anatolian Neolithic Farmers (also known as Early European Farmers), who along with Western Hunter Gatherers (WHG) and Ancient North Eurasians (via Eastern Hunter Gatherers and or Western Steppe Herders) are one of the three currently known ancestral genetic contributors to present-day Europeans. The existence of this ancient population has been inferred through the genetic analysis of the remains of a man from the site of Pınarbaşı (37 ° 29’N, 33 ° 02’E), in central Anatolia, which has been dated at 13,642-13,073 cal BCE. This population is genetically differentiated from the rest of the known Pleistocene populations.” ref

“It has been discovered that populations of the Anatolian Neolithic (Anatolian Neolithic Farmers) derive most of their ancestry from the AHG, with minor gene flow from Iranian/Caucasus and Levantine sources, suggesting that agriculture was adopted in situ by these hunter-gatherers and not spread by demic diffusion into the region. The Anatolian hunter-gatherers began farming around 8300 BCE, at places such as Çayönü. Cows, sheep and goats may have been domesticated first in southern Turkey. These farmers moved into Thrace (now European Turkey) around 7000 BCE. At the autosomal level, in the Principal component analysis (PCA) the analyzed AHG individual turns out to be close to two later Anatolian populations, the Anatolian Aceramic Farmers (AAF) dating from 8300-7800 BCE, and the Anatolian Ceramic Farmers (ACF) dating from 7000-6000 BCE. The individual analyzed belongs to Y-chromosomal haplogroup C1a2 (C-V20), which has been found in some of the early WHGs, and mitochondrial haplogroup K2b. Both paternal and maternal lineages are rare in present-day Eurasian populations.” ref

“These early Anatolian farmers later replaced the European hunter-gatherer populations in Europe to a large extent, ultimately becoming the main genetic contribution to current European populations, especially those of the Mediterranean. In addition, their position in this analysis is intermediate between Natufian farmers and Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG). This last point is confirmed by the ADMIXTURE and qp-Adm analysis and confirms the presence of hunter-gatherers of both European and Near-Eastern origins in Central Anatolia in the late Pleistocene. Mesolithic individuals from the Balkans, known as Iron Gates Hunter-Gatherers, are the most genetically similar group to the Anatolian Hunter-Gatherer lineage. Feldman et al. suggest that this affinity is not due to a genetic flow from the AHG to the ancestors of the Villabruna cluster, but on the contrary: there was a genetic flow from the ancestors of the Villabruna cluster to the ancestors of the AHG. The AHG diverged from Caucasus hunter-gatherer around 25,000 years ago.” ref

Iranian hunter-gatherers

“Despite the localization of the southern Caucasus at the outskirt of the Fertile Crescent, the Neolithisation process started there only at the beginning of the sixth millennium with the Shomutepe-Shulaveri culture of yet unclear origins. We present here genomic data for three new individuals from Mentesh Tepe in Azerbaijan, dating back to the beginnings of the Shomutepe-Shulaveri culture. Researchers have evidence that two juveniles, buried embracing each other, were brothers. We show that the Mentesh Tepe Neolithic population is the product of a recent gene flow between the Anatolian farmer-related population and the Caucasus/Iranian population, demonstrating that population admixture was at the core of the development of agriculture in the South Caucasus. By comparing Bronze Age individuals from the South Caucasus with Neolithic individuals from the same region, including Mentesh Tepe, we evidence that gene flows between Pontic Steppe populations and Mentesh Tepe-related groups contributed to the makeup of the Late Bronze Age and modern Caucasian populations.” ref

“The researcher’s results show that the high cultural diversity during the Neolithic period of the South Caucasus deserves close genetic analysis. “In the Near East, the Neolithic way of life emerged between 9000 and 7000 BCE. Several centers of Neolithisation have been identified, such as the Levant or Southern China, from which the agropastoral way of life diffused to other regions. The mechanisms of this diffusion have attracted tremendous attention for the last few decades. In some places, the Neolithic gained ground through the acculturation of local hunter-gatherers (for instance, in Anatolia or Iran); but in most regions (Europe, South-East Asia), farmer populations spread, and assimilation processes took place with a degree of admixture.” ref

“The agricultural transition profoundly changed human societies. We sequenced and analyzed the first genome (1.39x) of an early Neolithic woman from Ganj Dareh in the Zagros Mountains of Iran, a site with early evidence for an economy based on goat herding, ca. 10,000 years ago. We show that Western Iran was inhabited by a population genetically most similar to hunter-gatherers from the Caucasus, but distinct from the Neolithic Anatolian people who later brought food production into Europe. The inhabitants of Ganj Dareh made little direct genetic contribution to modern European populations, suggesting those of the Central Zagros were somewhat isolated from other populations of the Fertile Crescent. Runs of homozygosity are of a similar length to those from Neolithic farmers and shorter than those of Caucasus and Western Hunter-Gatherers, suggesting that the inhabitants of Ganj Dareh did not undergo the large population bottleneck suffered by their northern neighbors. While some degree of cultural diffusion between Anatolia, Western Iran, and other neighboring regions is possible, the genetic dissimilarity between early Anatolian farmers and the inhabitants of Ganj Dareh supports a model in which Neolithic societies in these areas were distinct.” ref

“The mechanism of Neolithisation in the South Caucasus, a region located between the Black and Caspian Seas on the southern slope of the Greater Caucasus Mountains, remains poorly understood. Mesolithic sites are known at Damjili Cave, unit 5 (Western Azerbaijan), Kmlo-2 Rock Shelter (Western Armenia), and Kotias Klde Cave (Western Georgia). Paleogenetic analyses of human bones excavated from the Kotias Klde Cave showed a genetic continuity with earlier Upper Palaeolithic (post-Last Glacial Maximum/LGM) sites but a discontinuity with pre-LGM individuals. Their genetic ancestry shares, to a certain extent, a common origin with ancient Iranian populations and differs from that of Anatolian and Levant hunter-gatherer groups, demonstrating a high genetic differentiation at this time between geographically close populations. The first settlements attributed to the Early Neolithic period belong to an aceramic culture, evidenced in several places in Central Georgia, as at Nagutni, in Western Georgia, as at Paluri, and in Western Azerbaijan at Damjili Cave, unit 4.” ref

“However, evidence of agriculture and herding remains scarce, suggesting that these sites represent a transitional phase between the Mesolithic and the Neolithic. In this context, the Shomutepe-Shulaveri culture (SSC) is the most ancient Caucasus culture with a complete Neolithic package. Found in several clusters of settlements in the northern foothills of the Lesser Caucasus, the SSC is characterized by circular mud-brick houses, domestic animals and cereals, handmade pottery, sometimes with incised and relief decoration, and obsidian and bone industries. Variants, such as the Aratashen/Aknashen culture (Ararat Plain), and other Neolithic contemporaneous cultures like the Kültepe Culture (Nakhchivan region) are also found in the South Caucasus. The slightly later Kamiltepe culture (Mil steppe culture), which probably includes the site of Polutepe, differs by its architecture, the use of flint tools instead of obsidian, and pottery-painted patterns that are rather related to Northern Iran and the Zagros.” ref

“The origins of the SSC are still discussed. Due to the rapid transition from the aceramic stage to the SSC, population continuity during the Neolithisation process is possible. However, several cultural and biological features are nonlocal. Domesticated animals, such as cattle, pigs, or goats, originate from Eastern Anatolia and from the Zagros mountains. Similarly, the glume wheat and barley recovered in the SSC sites have been domesticated elsewhere in the Middle East, even if the ancestors of the naked wheat Aegilops tauschii are found in the Caucasus and may have been local. The material culture and architecture evidence technical transfers with neighboring regions such as Southern Anatolia, Pre-Halafian, and Halafian culture of Northern Mesopotamia and Zagros11. Taken together, these data suggest a strong cultural connection, and maybe a degree of admixture, with other groups from the Fertile Crescent. Indeed, the genome-wide data for one individual coming from the same collective grave at Mentesh Tepe as the samples we analyze here, and confirmed by that of other individuals from Polutepe in the Mughan steppe or from Aknashen and Masis Blur in Armenia already showed that southern Caucasian groups are part of a cline that connected Eastern Anatolian and Zagros populations and evidence a gene flow that began around 6500 years BCE.” ref

“One of the oldest sites of the SSC, Mentesh Tepe, is located in the Tovuz district of western Azerbaijan and has been excavated between 2007 and 2015 (Fig. 1a). Several occupations were revealed, the earliest dating back to the Neolithic SSC period. At this time, the botanical assemblage is dominated by cereals, especially barley, naked wheat, and emmer, a common association during the Neolithic Southern Caucasus. Animal remains consist largely of domesticated ones (ovicaprines, cattle, pigs, dogs), and wild animals are rare. The diet of the Neolithic individuals from Mentesh Tepe relied mainly on C3-plants, such as wheat, barley, and lentils, with some evidence of freshwater fishes; the consumption of animal proteins varies between individuals. The pottery differs from classical SSC sites by being vegetal-tempered, a characteristic shared with Kamiltepe or the first occupation of the Nakhchivan site of Kültepe. As observed in many SSC sites, houses are circular and made of mudbricks, with or without the addition of straw or other organic material. Two SSC occupation phases are represented, separated in some places by a thick layer of ashes.” ref

“In a context where Neolithic burials are rare, Mentesh Tepe is exceptional for the discovery of a collective burial containing around 30 individuals (Fig. 1b), which is associated with the end of the first phase of frequentation of the site. Archaeoanthropological analysis has shown that it was a complex funerary gesture with mostly simultaneous deposits and, in contrast, some successive deposits that permitted manipulations on not completely decomposed bodies. The number of individuals in the burial, as well as their sex and age bias, suggest a dramatic event such as an epidemic, a famine, or a sudden episode, but no trace of violence has been evidenced on the bones. There is no specific orientation or position of the corpses, but some intentional arrangements are visible.” ref

“The most striking is formed by two juveniles embracing each other (Fig. 1c). Such an arrangement is rare, but other examples have been found in Neolithic and Protohistoric times, such as in Diyarbakir (Turkey, 6100 BCE) or Valdaro (Italy, 3000 BCE). Double burials are often considered as a lover’s embrace, but arguments for this explanation are often elusive. To better understand the origin of the Shomu-Shulaveri population and the structuration of this community, we performed paleogenetic studies of some of the individuals found in the collective burial. The genetic data obtained are then compared to those of another individual from the structure already published and to contemporaneous southwestern Asian genomes.” ref

Genetic structure of the Neolithic South-Caucasus

“The researchers merged our genome-wide data with the Human Origins dataset (HO-dataset), as well as with 3529 previously unrelated published ancient genomes (Supplementary Data 2). To decipher the genetic relations between the new Mentesh Tepe individuals and other ancient populations from the Caucasus, Anatolia, the Near East, and the Middle East, we performed: (1) a PCA on the modern dataset on which the ancient genomes have been projected and (2) an unsupervised ADMIXTURE analysis with the HO and the ancient dataset (Fig. 2a, b, Supplementary Fig. 2). The PCA shows that the Mentesh individuals overlap with some other previously published Neolithic or Chalcolithic individuals from the South Caucasus, but the individual from Aknashen falls a bit closer to CHG than the main neolithic cluster (Fig. 2a), and fall intermediate between the Iran Neolithic cluster and the Neolithic Anatolian Farmer group. The ADMIXTURE analysis suggests that the Mentesh individuals carry three main components: i.e., ca. 30% Neolithic Iran (Iran_N; green), 15% Levant Neolithic (PPN; pale rose) and 55% blue and pink components shared with Anatolian or European Neolithic populations (Fig. 2b).” ref