Samara culture with Horse Sacrifice and Kurgan burials

7,500-year-old Horse Sacrifice (its origin?)

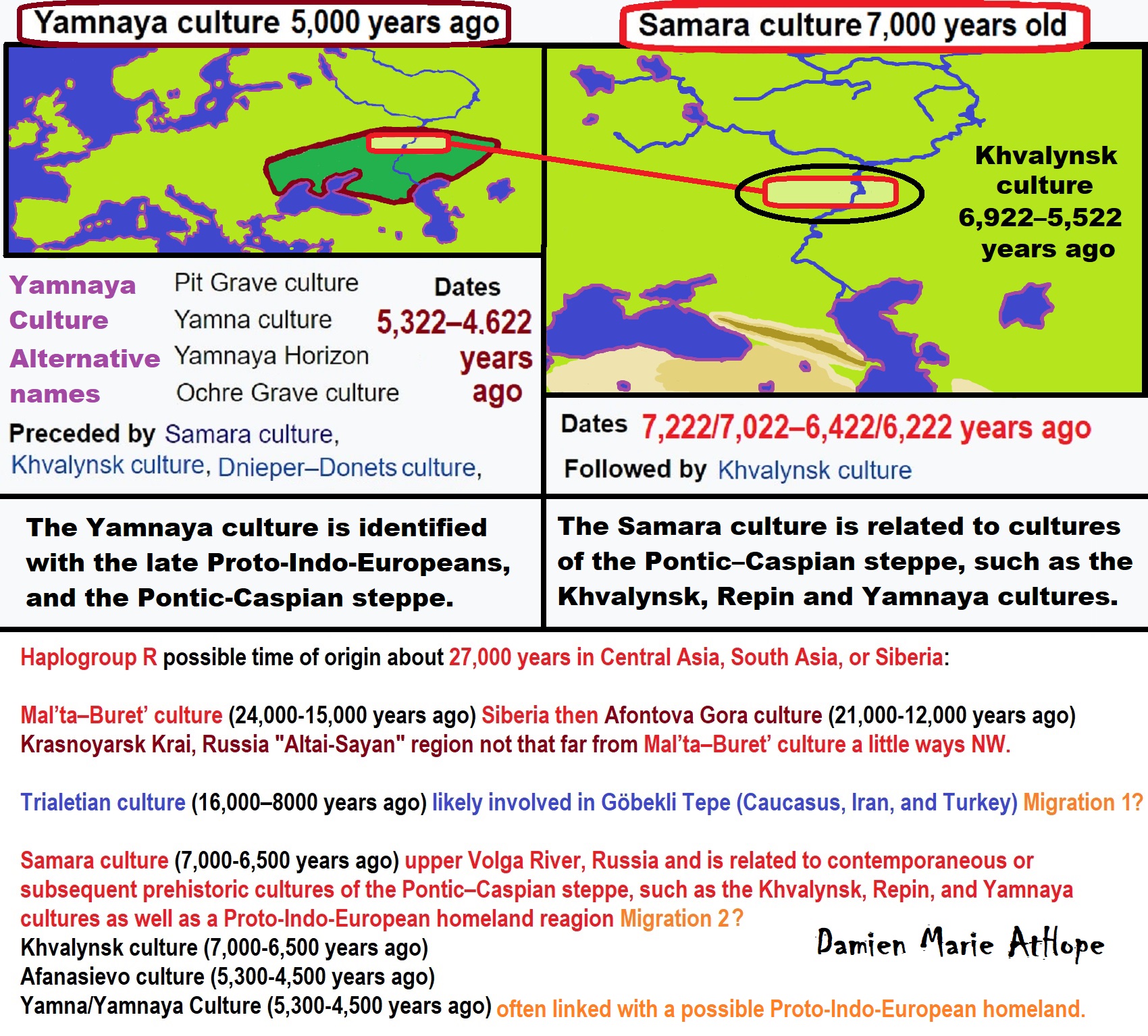

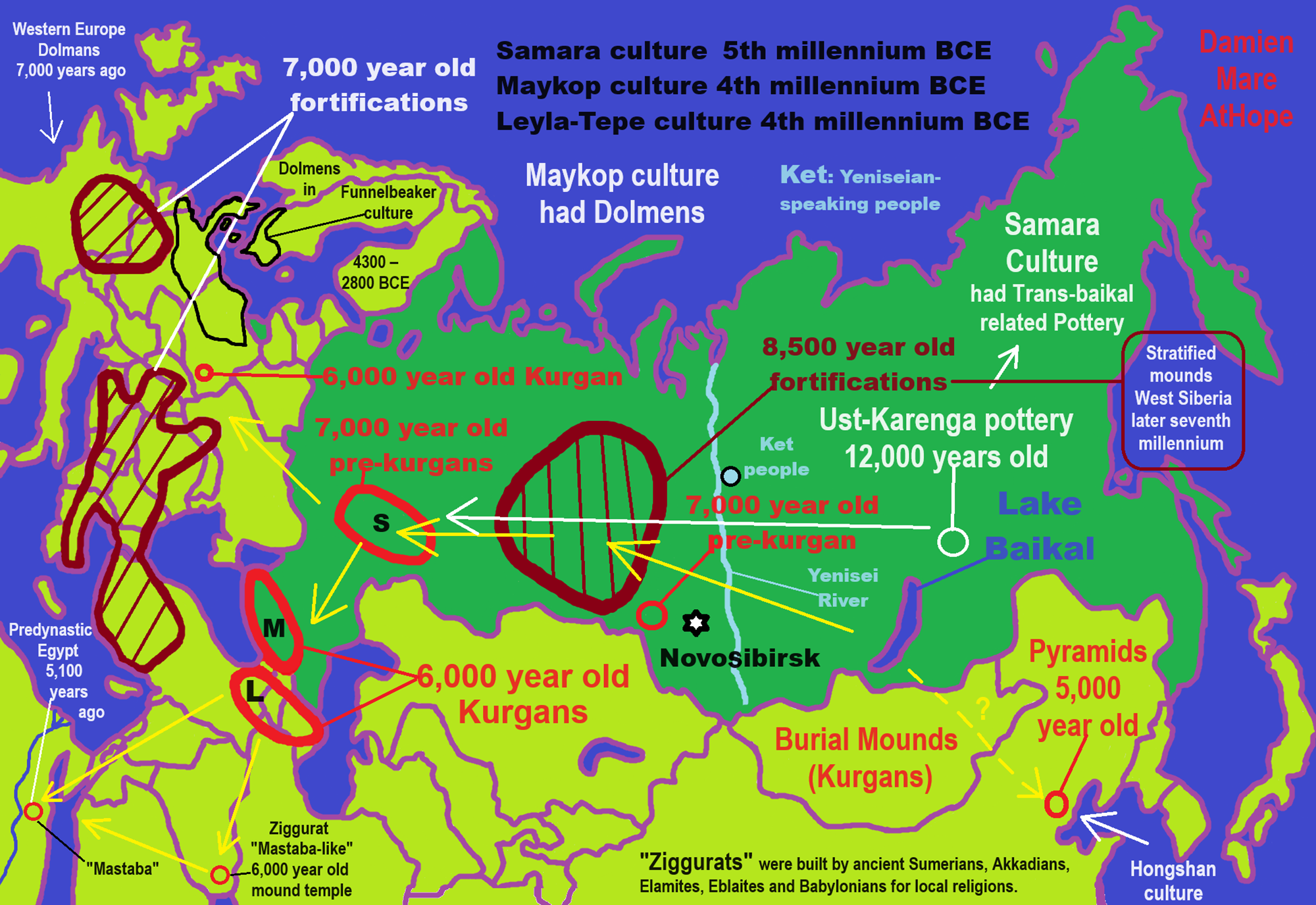

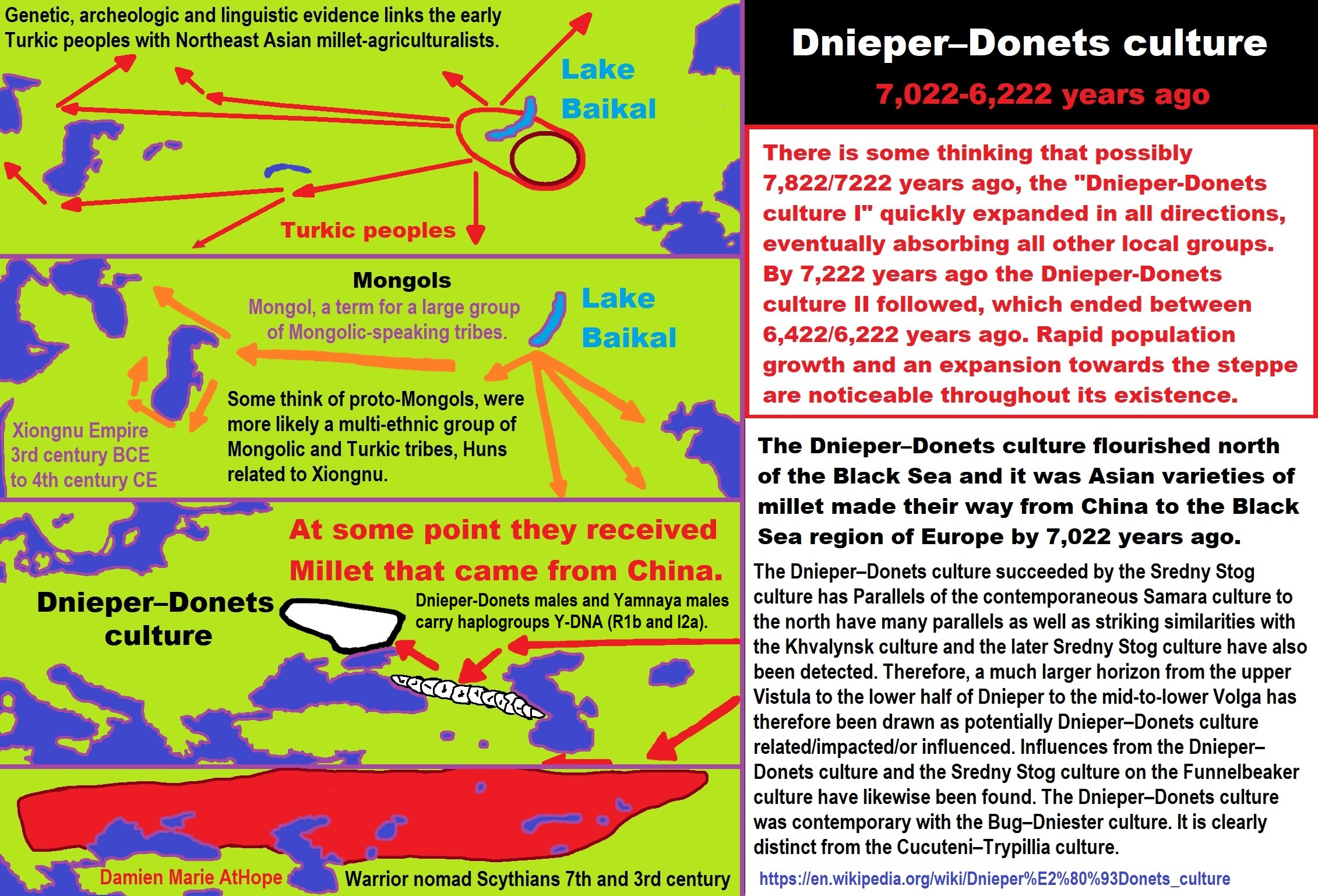

“The Samara culture is an Eneolithic (Copper Age) culture dating to 5500 BCE/7,500 years ago (to 6,000 years ago?), the turn of the 5th millennium BCE, at the Samara Bend of the Volga River (modern Russia). The Samara culture is regarded as related to contemporaneous or subsequent prehistoric cultures of the Pontic–Caspian steppe, such as the Khvalynsk, Repin, and Yamna (or Yamnaya) cultures. Genetic analyses of a male buried at Lebyazhinka, radiocarbon dated to 5640-5555 years ago, found that he belonged to a population often referred to as “Samara hunter-gatherers,” a group closely associated with Eastern Hunter-Gatherers. The male sample carried Y-haplogroup R1b1a1a and mitochondrial haplogroup U5a1d.” ref

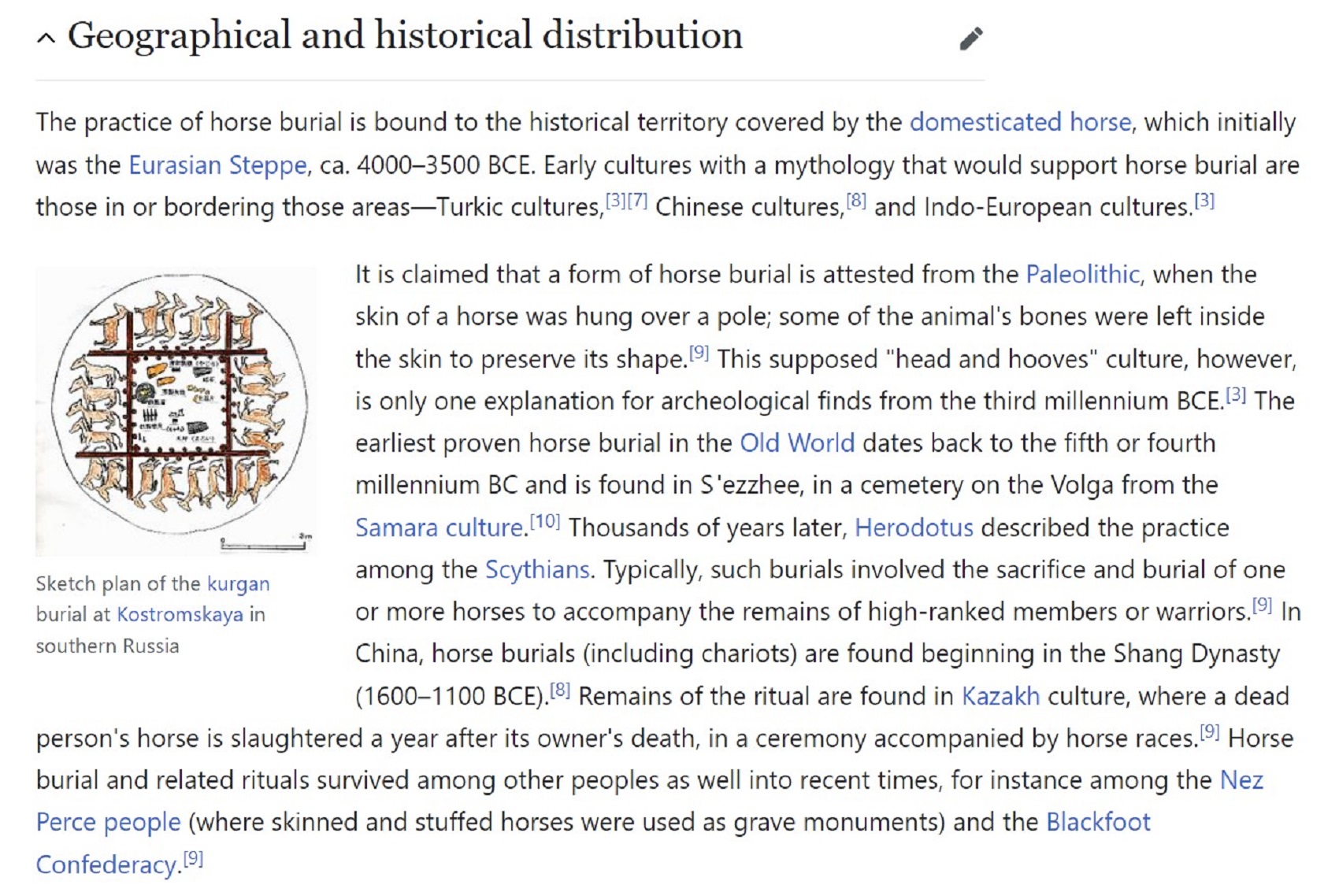

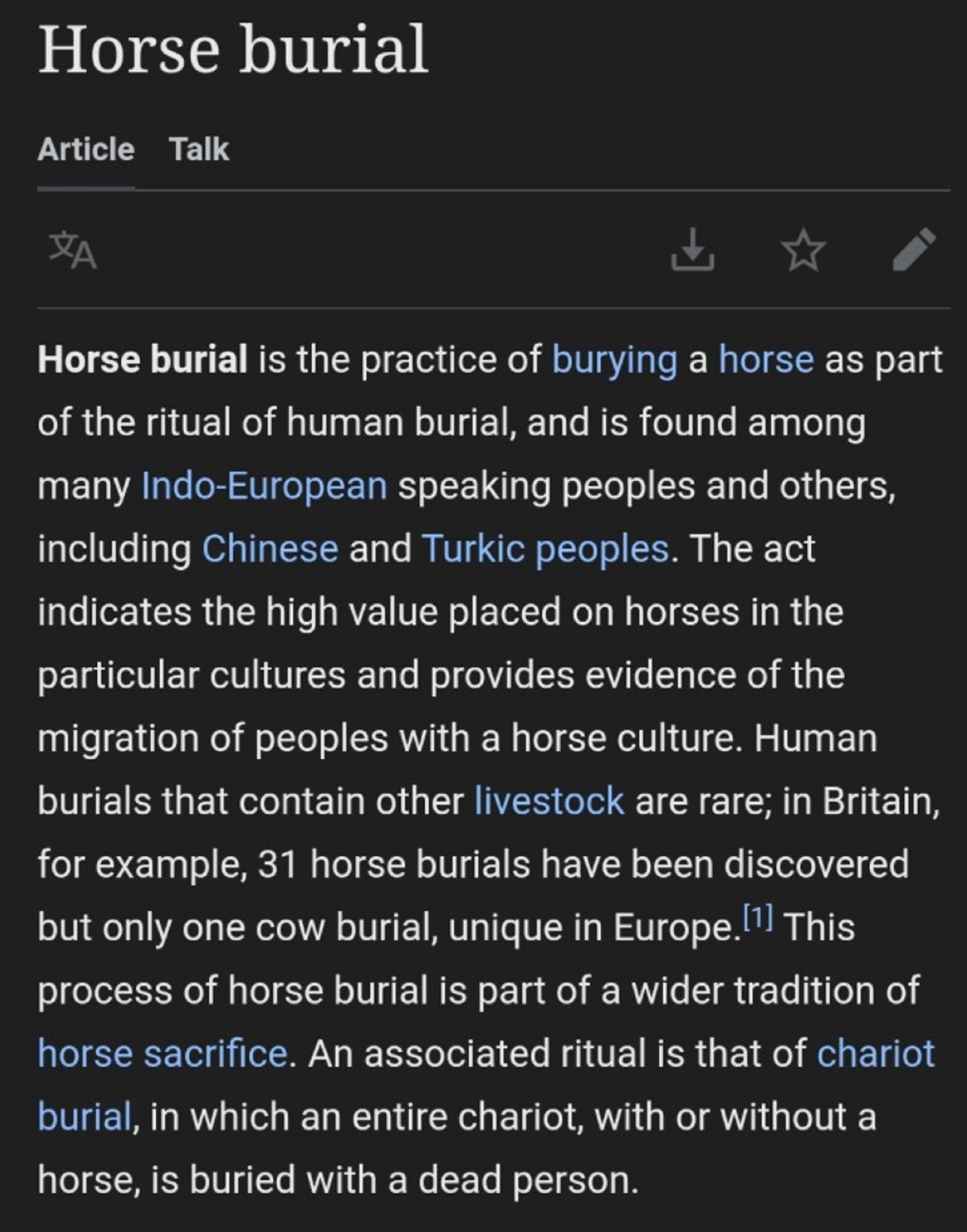

“The culture is characterized by the remains of animal sacrifice, which occur over most of the sites. There is no indisputable evidence of riding, but there were horse burials, the earliest in the Old World. Typically, the head and hooves of cattle, sheep, and horses are placed in shallow bowls over the human grave, smothered with ochre. Some have seen the beginning of the horse sacrifice in these remains, but this interpretation has not been more definitely substantiated. It is known that the Indo-Europeans sacrificed both animals and people, like many other cultures.” ref

“Some of the graves are covered with a stone cairn or a low earthen mound, the very first predecessor of the kurgan. The later, fully developed kurgan was a hill on which the deceased chief might ascend to the sky god, but whether these early mounds had that significance is unknown. Grave offerings included ornaments depicting horses. The graves also had an overburden of horse remains; it cannot yet be determined decisively if these horses were domesticated and ridden or not, but they were certainly used as a meat-animal. Most controversial are bone plaques of horses or double oxen heads, which were pierced.” ref

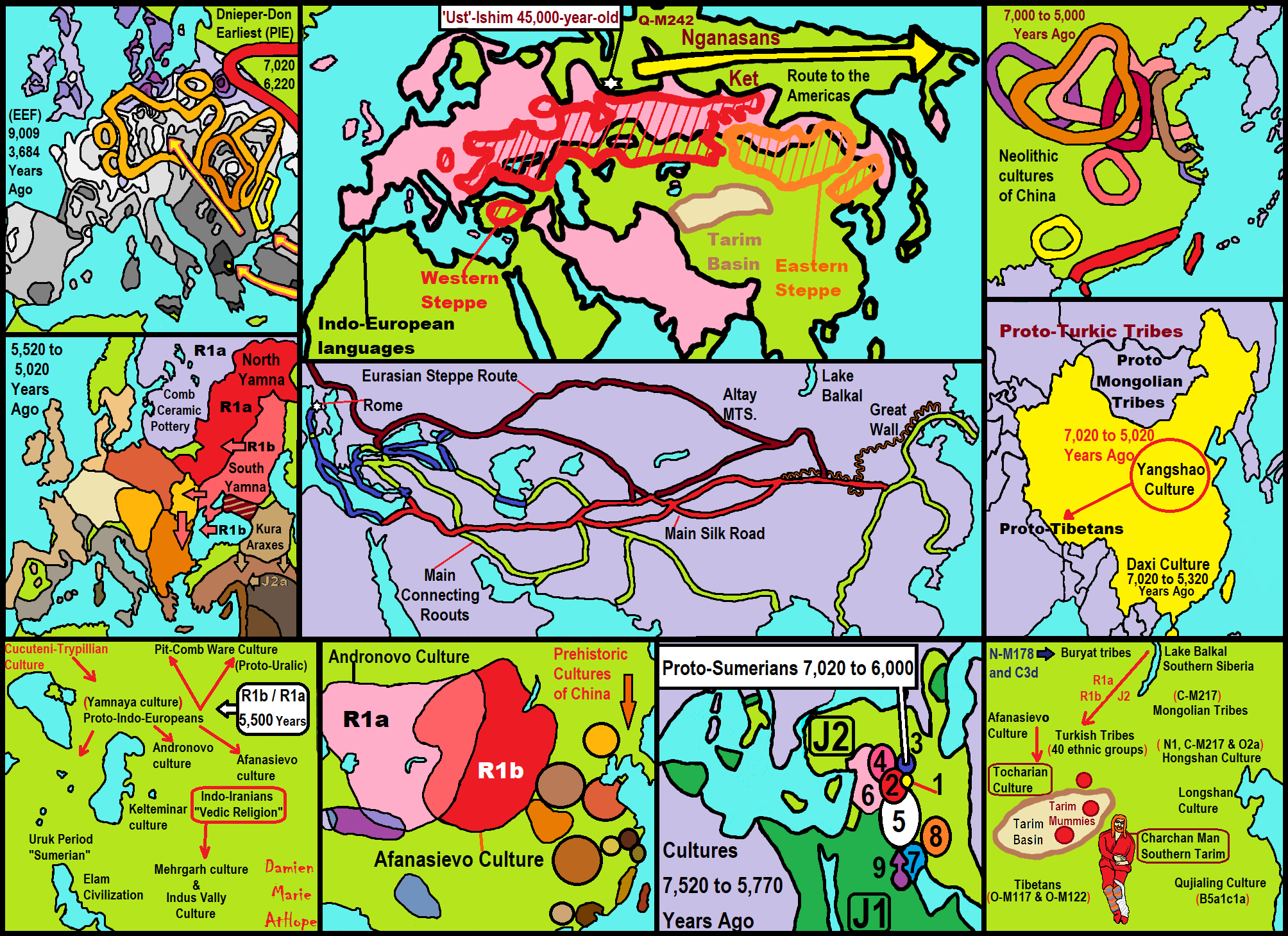

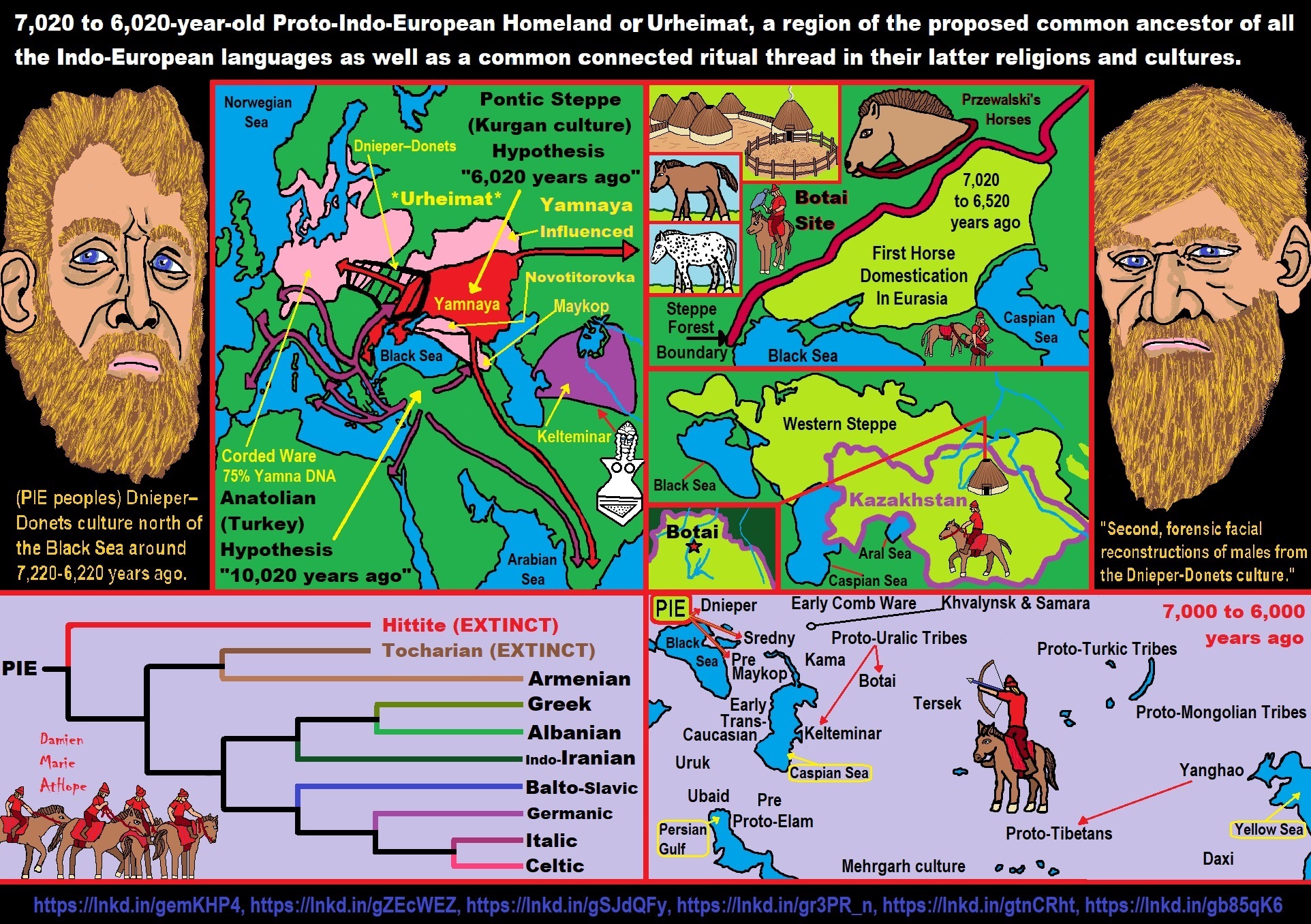

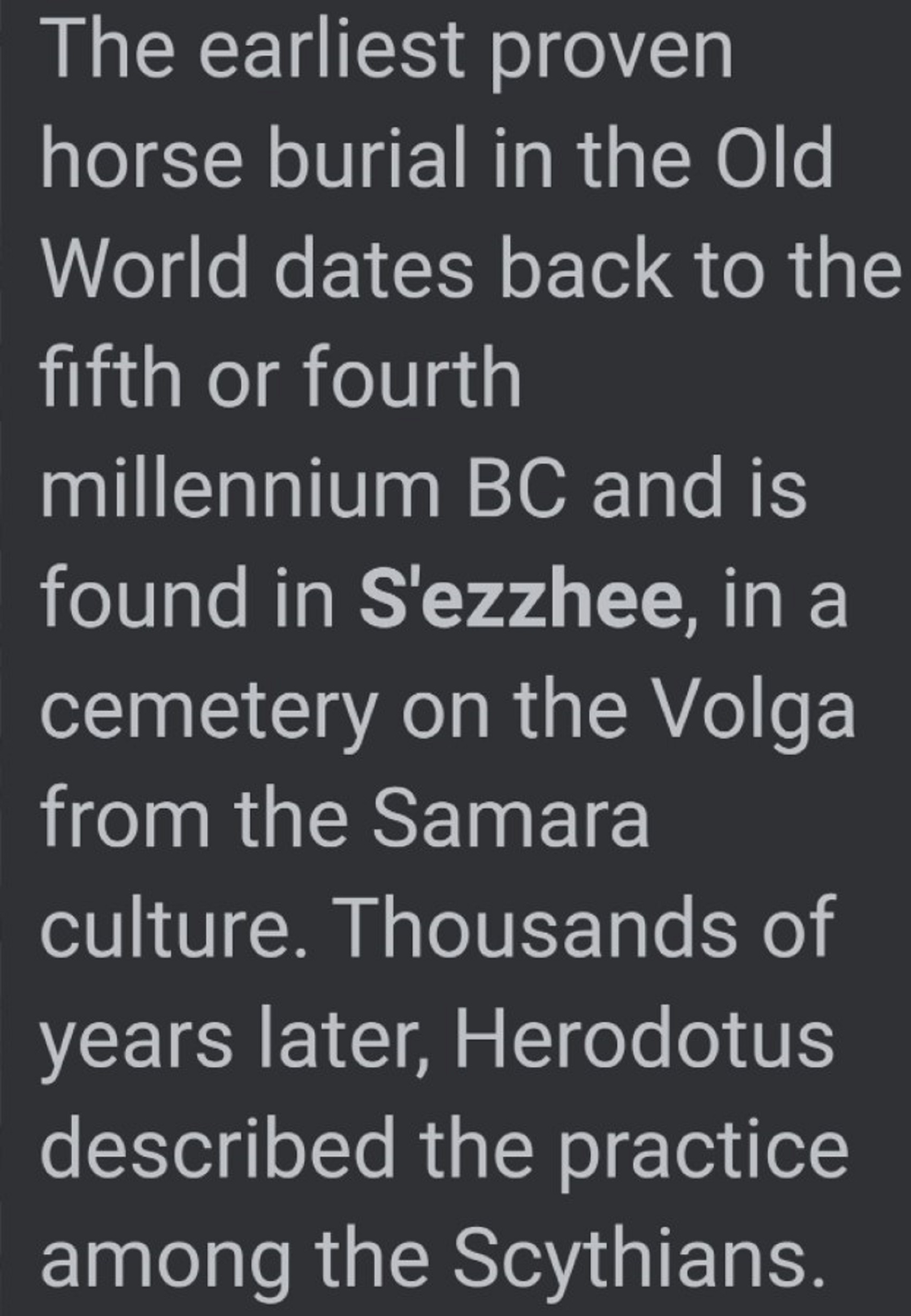

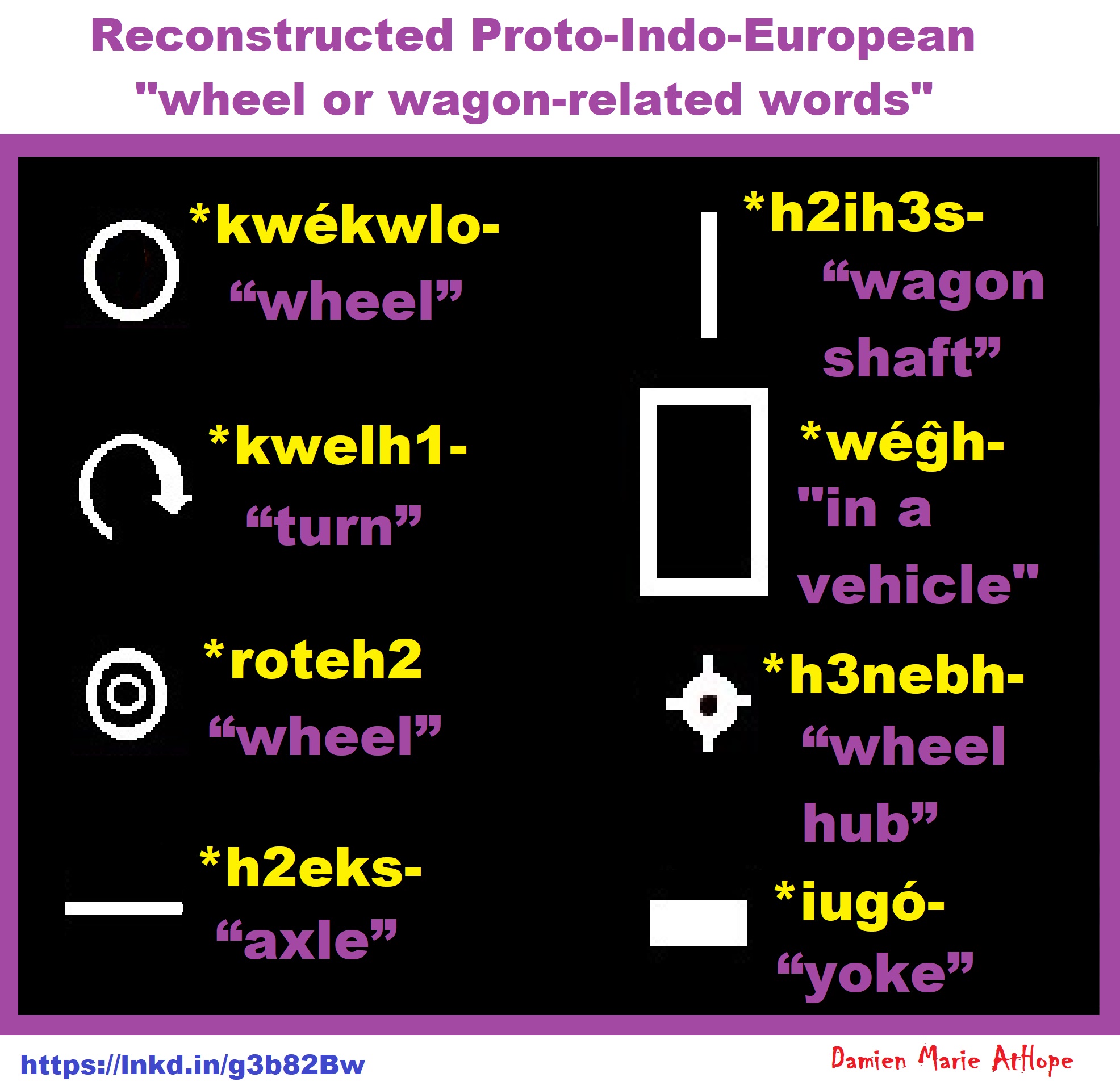

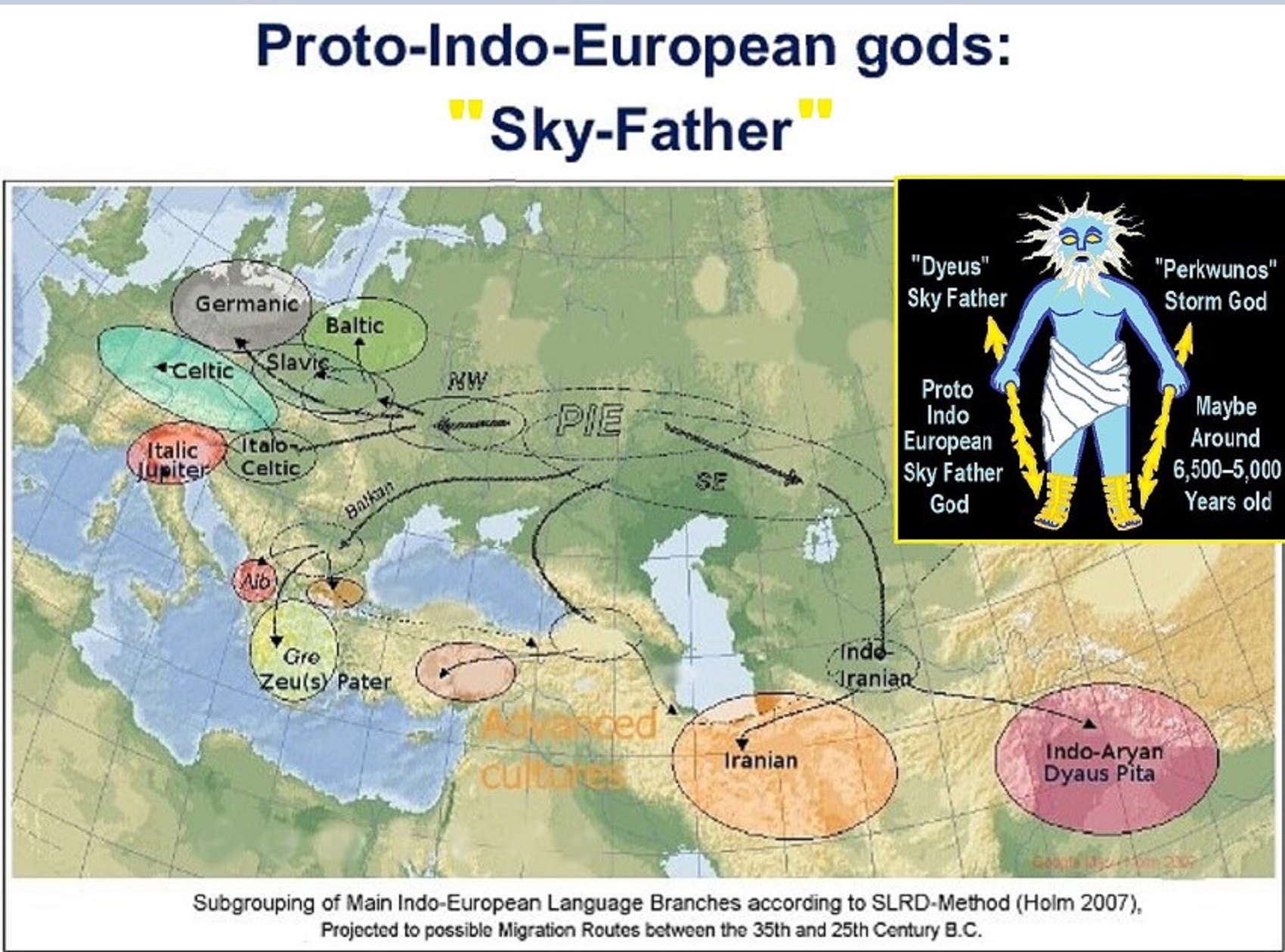

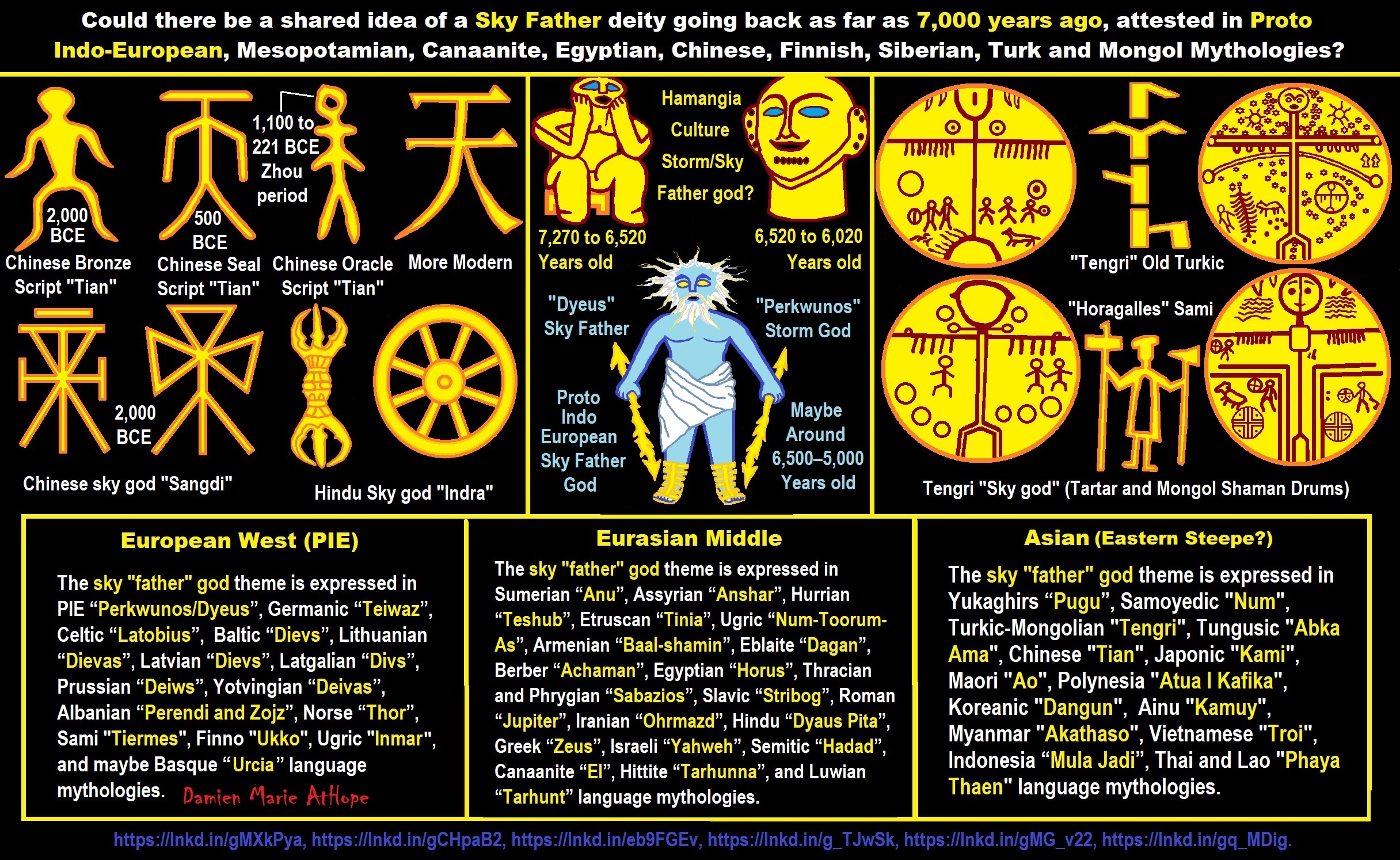

“From at least about 4500 BCE or around 6,500 years ago, a single dialect called Proto-Indo-European (PIE) existed as the forerunner of all modern Indo-European languages, but it left no written texts, and its structure is unknown.” ref

The prehistoric origins of the domestic horse and horseback riding

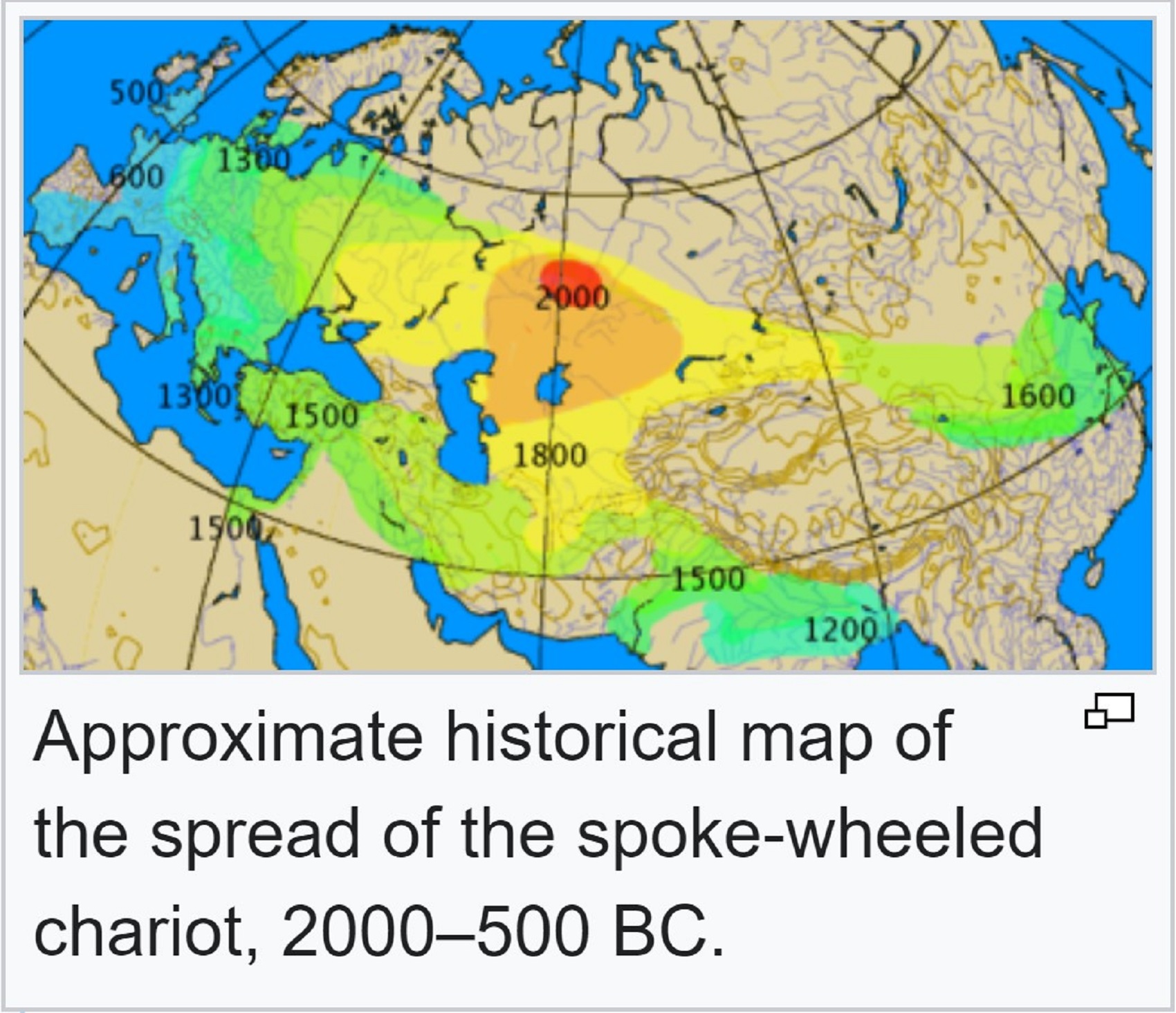

“The findings of Librado et al. (2021) show that modern domestic horses (DOM2) emerged in the lower Don-Volga region. They imply that horseback riding drove selection that resulted in these horses and fuelled their initial dispersal, and also that DOM2 horses replaced other horses because they were more suitable for riding due to their more docile temperaments and resilient backs. In this article, I argue that captive breeding of horses leading to their domestication began in about 4500-3000 BCE in the Pontic-Caspian steppe and made horseback riding necessary because managing horses, and especially moving them over long distances, required mounted herding. Horseback riding had been experimented with since the second half of the 5th millennium BCE, became common around 3100 BCE during the early stages of the Yamnaya culture, and necessary by the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE at the very latest. As horseback riding became more common, selection for malleable temperaments and resilient backs intensified, resulting in DOM2 horses by about 2300-2200 BCE in the lower Don-Volga region. The body size and weight-carrying ability of ancestral and early DOM2 horses were not limiting factors for horseback riding. The initial dispersal of DOM2 horses was facilitated by horseback riding and began by about 2300±150 BCE. Chariotry began to spread together with DOM2 horses after 2000 BC, but its high archaeological visibility may have inflated its importance, since chariots are of limited practical use for herding and other daily tasks.” ref

Khvalynsk culture with Horse Sacrifice and Kurgan burials

6,900-year-old Horse Sacrifice

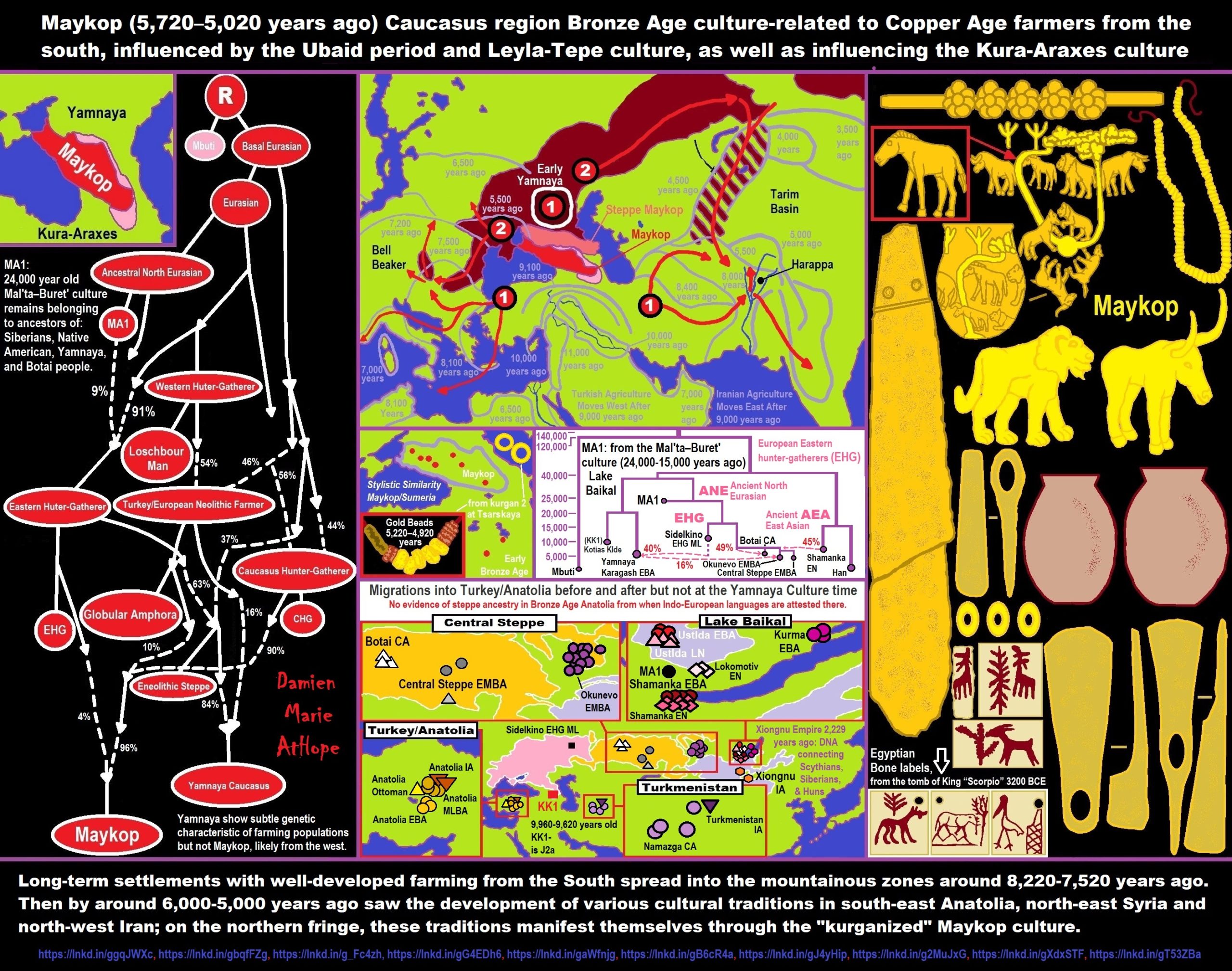

“The Khvalynsk culture is a Middle Copper Age Eneolithic culture (c. 4,900 – 3,500 BCE ) of the middle Volga region. It takes its name from Khvalynsk in Saratov Oblast. The Khvalynsk culture is found from the Samara Bend in the north (the location of some of the most important sites such as Krivoluchye) to the North Caucasus in the south, from the Sea of Azov in the west to the Ural River in the east. It was preceded by the Early Eneolithic Samara culture. Sacrificial areas were found similar to those at Samara, containing horse, cattle, and sheep remains. Khvalynsk evidences the further development of the kurgan. It began in the Samara with individual graves or small groups, sometimes under stone.” ref

“Nina Morgunova regards Khvalynsk I as Early Eneolithic, contemporary with the second stage of Samara culture called Ivanovka and Toksky stage, which pottery was influenced by Khvalynsk culture, as a calibrated period of this second stage of Samara culture is 4,850–3,640 BCE. After c. 4,500 BCE, Khvalynsk culture united the lower and middle Volga sites keeping domesticated sheep, goats, cattle, and maybe horses. The Krivoluchie grave, which Gimbutas viewed as that of a chief, contained a long flint dagger and tanged arrowheads, all carefully retouched on both faces. In addition, there is a porphyry axe-head with lugs and a haft hole. These artifacts are of types that not too long after appeared in metal.” ref

“Although there are disparities in the wealth of the grave goods, there seems to be no special marker for the chief. This deficit does not exclude the possibility of a chief. In the later kurgans, one finds that the kurgan is exclusively reserved for a chief and his retinue, with ordinary people excluded. This development suggests a growing disparity of wealth, which in turn implies a growth in the wealth of the whole community and an increase in population. The explosion of the kurgan culture out of its western steppe homeland must be associated with an expansion of population. The causes of this success and expansion remain obscure.” ref

“Early examination of physical remains of the Khvalynsk people determined that they were Caucasoid. A similar physical type prevails among the Sredny Stog culture and the Yamnaya culture, whose peoples were powerfully built. Khvalynsk people were, however, not as powerfully built as the Sredny Stog and Yamnaya. The people of the Dnieper-Donets culture further west on the other hand, were even more powerfully built than the Yamnaya.” ref

“Recent genetic studies have shown that males of the Khvalynsk culture carried primarily the paternal haplogroup R1b, although a few samples of R1a, I2a2, Q1a, and J have been detected. They belonged to the Western Steppe Herder (WSH) cluster, which is a mixture of Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) and Caucasian Hunter-Gatherer (CHG) ancestry. This admixture appears to have happened on the eastern Pontic–Caspian steppe starting around 5,000 BCE. Mathieson et al. (2015, 2018) found in three Eneolithic males buried near Khvalynsk between 5,200 BC and 4,000 BCE the Y-haplogroups R1b1a and R1a1, and the mt-haplogroups H2a1, U5a1i, and Q1a and a subclade of U4.” ref

“A male from the contemporary Sredny Stog culture was found to have 80% WSH ancestry of a similar type to the Khvalynsk people, and 20% Early European Farmer (EEF) ancestry. Among the later Yamnaya culture, males carry exclusively R1b and I2. A similar pattern is observable among males of the earlier Dnieper-Donets culture, who carried only R and I and whose ancestry was exclusively EHG with Western Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) admixture.” ref

“The presence of EEF and CHG mtDNA and exclusively EHG and WHG Y-DNA among the Yamnaya and related WSHs suggest that EEF and CHG admixture among them was the result of mixing between EHG and WHG males, and EEF and CHG females. This suggests that the leading clans among the Yamnaya were of EHG paternal origin. According to David W. Anthony, this implies that the Indo-European languages were the result of “a dominant language spoken by EHGs that absorbed Caucasus-like elements in phonology, morphology, and lexicon” (spoken by CHGs) Other studies have suggested that the Indo-European language family may have originated not in Eastern Europe, but among West Asian (CHG-like) populations south of the Caucasus.” ref

5,000-year-old Horseback Riding?

“Archaeologists have previously found evidence of people consuming horse milk in dental remains and indications of horses controlled by harnesses and bits dating back more than 5,000 years, but that does not necessarily indicate the horses were ridden.” ref

“Clear evidence related to the world’s first horseback rider from hallmark damage that horseback riding does to the body. To identify horsemanship syndrome in ancient remains, the researchers developed a list of six indicators. They then set out to seek these indicators in bodies buried in Yamnaya kurgans (tomb mounds) excavated in Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary, dating between 5,020 to 4,500 years ago. Altogether, they studied 24 skeletons – most Yamnaya – and some from other cultures in the vicinity. Among the six indicators cited for habitual horsemanship are stress signals in the pelvis and thigh bones, because riding, especially without a saddle and stirrups, involves the rider tightening the thighs and straining the lower body with each step the animal takes, lest they fall off.” ref

“Nine of the bodies evinced at least four of the six characteristics, marking them as likely horseback riders. Of these, five exhibited at least five of the six pathologies, while one person buried in Strejnicu, Romania, had all six. There are caveats. There is no archaeological benchmark for “damage caused by riding a horse” as opposed to other theoretical strains. Basket weaving could result in some similar indicators, they point out. Absent benchmarking, then, interpretations may vary and comparison with other nomadic pre-and-post-horse peoples could help. That has not been done yet. However, the researchers feel that, taken together, the six indicators do the job.” ref

“Indirect evidence of riding by the Yamnaya is the speed of their spread to Hungary in the west and Siberia in the northeast. “Considering the vast geographical distances of 4,500 kilometers (almost 2,800 miles) between the Tisza River [in Hungary] and the Altai Mountains [in Siberia], the absence of roads and the small overall population sizes, it is difficult to envision how this expansion could have taken place without improved means of transport,” they write. So in short, Yamnaya seem to have been the first horse riders, back in the Early Bronze Age. The authors add that 15 of their 24 bodies had three of the six telltale features. Not everybody who rides a horse will develop all six.” ref

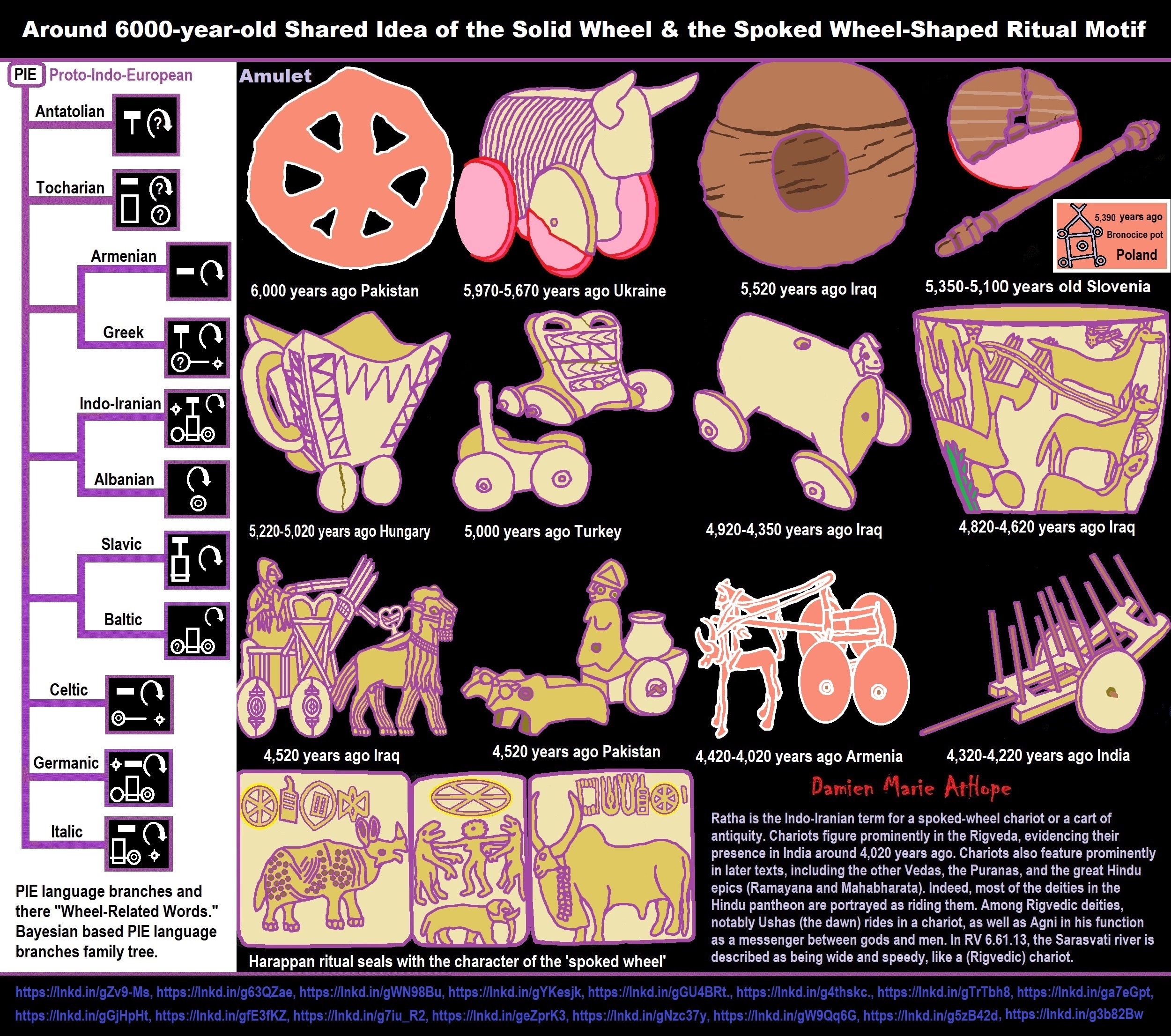

Yamnaya culture with Horse Sacrifice and Kurgan burials

- “Also known as the Yamnaya Culture, Pit Grave Culture or Ochre Grave Culture.

- Generally considered by linguists as the homeland of the Proto-Indo-European language.

- It probably originated between the Lower Don, the Lower Volga, and North Caucasus during the Chalcolithic, around what became the Novotitorovka culture (3300-2700 BCE) within the Yamna culture.

- Highly mobile steppe culture of pastoral nomads relying heavily on cattle (dairy farming). Sheep were also kept for their wool. Hunting, fishing, and sporadic agriculture were practiced near rivers.

- The first culture (along with Maykop) to make regular use of ox-drawn wheeled carts. Metal artifacts (tools, axes, tanged daggers) were mostly made of copper, with some arsenical bronze. Domesticated horses are used as pack animals and ridden to manage cattle herds.

- Coarse, flat-bottomed, egg-shaped pottery decorated with comb stamps and cord impressions.

- The dead were inhumed in pit graves inside kurgans (burial mounds). Bodies were placed in a supine position with bent knees and covered in ochre. Wagons/carts and sacrificed animals (cattle, horse, sheep) were present in graves, a trait typical of later Indo-European cultures.” ref

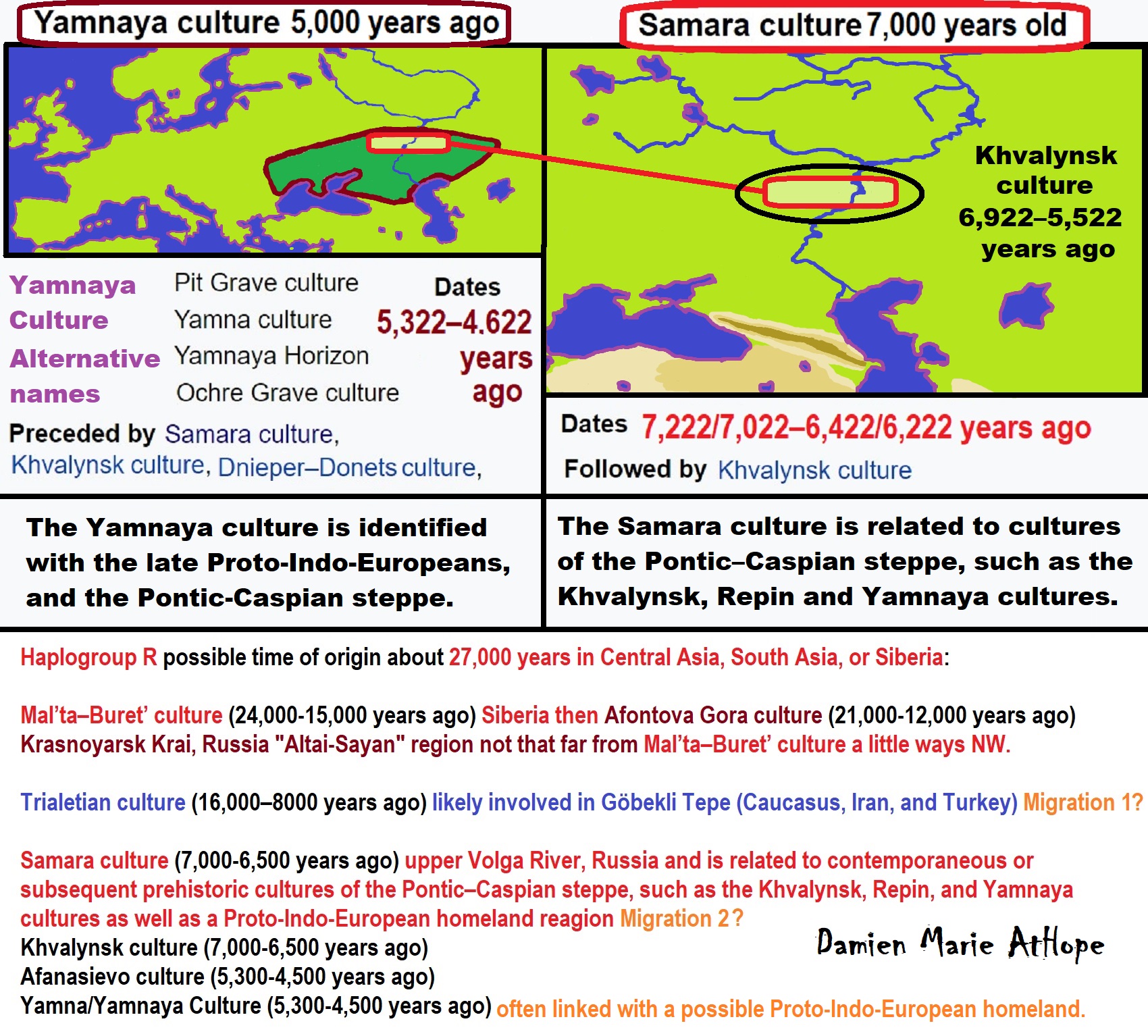

“The Yamnaya culture or the Yamna culture, also known as the Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, is a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archaeological culture of the region between the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Ural rivers (the Pontic–Caspian steppe), dating to 3300–2600 BCE. It was discovered by Vasily Gorodtsov following his archaeological excavations near the Donets River in 1901–1903. Its name derives from its characteristic burial tradition: Я́мная (romanization: yamnaya) is a Russian adjective that means ‘related to pits (yama)’, as these people used to bury their dead in tumuli (kurgans) containing simple pit chambers.” ref

“The Yamna DNA samples recovered from elite Kurgan graves in southern Russia belonged overwhelmingly to haplogroup R1b-Z2103, the essentially eastern branch of Indo-European R1b. The absence of other main R1b subclades is probably due to the dominance of a single royal or aristocratic lineage among the Yamnayan elite buried in Kurgans. Other R1b subclades did show up in Germany (DF27, U152) and Ireland (L21) when Steppe-derived people reached those regions between 2500 and 2000 BCE. The only non-R1b sample found in Yamna was an I2a2a-L699, a lineage descended from WHG tribes that migrated to Eastern Europe, but came back with the Indo-European migrations and is now found especially in Central and Western Europe.” ref

“The Yamnaya economy was based upon animal husbandry, fishing, and foraging, and the manufacture of ceramics, tools, and weapons. The people of the Yamnaya culture lived primarily as nomads, with a chiefdom system and wheeled carts and wagons that allowed them to manage large herds. They are also closely connected to Final Neolithic cultures, which later spread throughout Europe and Central Asia, especially the Corded Ware people and the Bell Beaker culture, as well as the peoples of the Sintashta, Andronovo, and Srubnaya cultures. Back migration from Corded Ware also contributed to Sintashta and Andronovo. In these groups, several aspects of the Yamnaya culture are present. Yamnaya material culture was very similar to the Afanasevo culture of South Siberia, and the populations of both cultures are genetically indistinguishable. This suggests that the Afanasevo culture may have originated from the migration of Yamnaya groups to the Altai region or, alternatively, that both cultures developed from an earlier shared cultural source.” ref

“Genetic studies have suggested that the people of the Yamnaya culture can be modeled as a genetic admixture between a population related to Eastern European Hunter-Gatherers (EHG) and people related to hunter-gatherers from the Caucasus (CHG) in roughly equal proportions, an ancestral component which is often named “Steppe ancestry”, with additional admixture from Anatolian, Levantine, or Early European farmers. Genetic studies also indicate that populations associated with the Corded Ware, Bell Beaker, Sintashta, and Andronovo cultures derived large parts of their ancestry from the Yamnaya or a closely related population. According to the widely-accepted Kurgan hypothesis, of Marija Gimbutas, the people that produced the Yamnaya culture spoke a stage of the Proto Indo-European language, which later spread eastwards and westwards as part of the Indo-European migrations.” ref

“The Yamnaya culture was defined by Vasily Gorodtsov in order to differentiate it from the Catacomb and Srubnaya cultures that existed in the area, but were considered to be of a later period. Due to the time interval to the Yamnaya culture, and the reliance on archaeological findings, debate as to its origin is ongoing. In 1996, Pavel Dolukhanov suggested that the emergence of the Pit-Grave culture represents a social development of various different local Bronze Age cultures, thus representing “an expression of social stratification and the emergence of chiefdom-type nomadic social structures” which in turn intensified inter-group contacts between essentially heterogeneous social groups.” ref

“The origin of the Yamnaya culture continues to be debated, with proposals for its origins pointing to both the Khvalynsk and Sredny Stog cultures. The Khvalynsk culture (4700–3800 BCE) (middle Volga) and the Don-based Repin culture (c. 3950–3300 BCE) in the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe, and the closely related Sredny Stog culture (c. 4500–3500 BCE) in the western Pontic-Caspian steppe, preceded the Yamnaya culture (3300–2500 BCE). The Yamnaya culture was succeeded in its western range by the Catacomb culture (2800–2200 BCE); in the east, by the Poltavka culture (2700–2100 BCE) at the middle Volga. These two cultures were followed by the Srubnaya culture (18th–12th century BCE).” ref

“Further efforts to pinpoint the location came from Anthony (2007), who suggested that the Yamnaya culture (3300–2600 BCE) originated in the Don–Volga area at c. 3400 BC, preceded by the middle Volga-based Khvalynsk culture and the Don-based Repin culture (c. 3950–3300 BCE), arguing that late pottery from these two cultures can barely be distinguished from early Yamnaya pottery. Earlier continuity from eneolithic but largely hunter-gatherer Samara culture and influences from the more agricultural Dnieper–Donets II are apparent.” ref

He argues that the early Yamnaya horizon spread quickly across the Pontic–Caspian steppes between c. 3400 and 3200 BCE: The spread of the Yamnaya horizon was the material expression of the spread of late Proto-Indo-European across the Pontic–Caspian steppes. […] The Yamnaya horizon is the visible archaeological expression of a social adjustment to high mobility – the invention of the political infrastructure to manage larger herds from mobile homes based in the steppes.” ref

“Alternatively, Parpola (2015) relates both the Corded ware culture and the Yamnaya culture to the late Trypillia (Tripolye) culture. He hypothesizes that “the Tripolye culture was taken over by PIE speakers by c. 4000 BCE,” and that in its final phase the Trypillian culture expanded to the steppes, morphing into various regional cultures which fused with the late Sredny Stog (Serednii Stih) pastoralist cultures, which, he suggests, gave rise to the Yamnaya culture. Dmytro Telegin viewed Sredny Stog and Yamna as one cultural continuum and considered Sredny Stog to be the genetic foundation of the Yamna.” ref

“The Yamnaya culture was nomadic or semi-nomadic, with some agriculture practiced near rivers, and a few fortified sites, the largest of which is Mikhaylivka. Characteristic for the culture are the burials in pit graves under kurgans (tumuli), often accompanied by animal offerings. Some graves contain large anthropomorphic stelae, with carved human heads, arms, hands, belts, and weapons. The dead bodies were placed in a supine position with bent knees and covered in ochre. Some kurgans contained “stratified sequences of graves.” Kurgan burials may have been rare, and were perhaps reserved for special adults, who were predominantly, but not necessarily, male. Status and gender are marked by grave goods and position, and in some areas, elite individuals are buried with complete wooden wagons. Grave goods are more common in eastern Yamnaya burials, which are also characterized by a higher proportion of male burials and more male-centred rituals than western areas.” ref

“The Yamnaya culture had and used two-wheeled carts and four-wheeled wagons, which are thought to have been oxen-drawn at this time, and there is evidence that they rode horses. For instance, several Yamnaya skeletons exhibit specific characteristics in their bone morphology that may have been caused by long-term horseriding. Metallurgists and other craftsmen are given a special status in Yamnaya society, and metal objects are sometimes found in large quantities in elite graves. New metalworking technologies and weapon designs are used.” ref

“Stable isotope ratios of Yamna individuals from the Dnipro Valley suggest the Yamnaya diet was terrestrial protein based with insignificant contribution from freshwater or aquatic resources. Anthony speculates that the Yamnaya ate meat, milk, yogurt, cheese, and soups made from seeds and wild vegetables, and probably consumed mead. Mallory and Adams suggest that Yamnaya society may have had a tripartite structure of three differentiated social classes, although the evidence available does not demonstrate the existence of specific classes such as priests, warriors, and farmers.” ref

“According to Jones et al. (2015) and Haak et al. (2015), autosomal tests indicate that the Yamnaya people were the result of a genetic admixture between two different hunter-gatherer populations: distinctive “Eastern Hunter-Gatherers” (EHG), from Eastern Europe, with high affinity to the Mal’ta–Buret’ culture or other, closely related people from Siberia and a population of “Caucasus hunter-gatherers” (CHG) who probably arrived from the Caucasus or Iran. Each of those two populations contributed about half the Yamnaya DNA. This admixture is referred to in archaeogenetics as Western Steppe Herder (WSH) ancestry.” ref

“Autosomal tests also indicate that the Yamnaya are the vector for “Ancient North Eurasian” admixture into Europe. “Ancient North Eurasian” is the name given in literature to a genetic component that represents descent from the people of the Mal’ta–Buret’ culture or a population closely related to them. That genetic component is visible in tests of the Yamnaya people as well as modern-day Europeans. Admixture between EHGs and CHGs is believed to have occurred on the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe starting around 5,000 BCE, while admixture with Early European Farmers (EEF) happened in the southern parts of the Pontic-Caspian steppe sometime later. More recent genetic studies have found that the Yamnaya were a mixture of EHGs, CHGs, and to a lesser degree Anatolian farmers and Levantine farmers, but not EEFs from Europe due to lack of WHG DNA in the Yamnaya. This occurred in two distinct admixture events from West Asia into the Pontic-Caspian steppe.” ref

“Haplogroup R1b, specifically the Z2103 subclade of R1b-L23, is the most common Y-DNA haplogroup found among the Yamnaya specimens. This haplogroup is rare in Western Europe and mainly exists in Southeastern Europe today. Additionally, a minority are found to belong to haplogroup I2. They are found to belong to a wider variety of West Eurasian mtDNA haplogroups, including U, T, and haplogroups associated with Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers and Early European Farmers. A small but significant number of Yamnaya kurgan specimens from Northern Ukraine carried the East Asian mtDNA haplogroup C4. People of the Yamnaya culture are believed to have mostly brown eye color, light to intermediate skin, and brown hair color, with some variation.” ref

“Some Yamnaya individuals are believed to have carried a mutation to the KITLG gene associated with blond hair, as several individuals with Steppe ancestry are later found to carry this mutation. The Ancient North Eurasian Afontova Gora group, who contributed significant ancestry to Western Steppe Herders, are believed to be the source of this mutation. A study in 2015 found that Yamnaya had the highest ever calculated genetic selection for height of any of the ancient populations tested. It has been hypothesized that an allele associated with lactase persistence (conferring lactose tolerance into adulthood) was brought to Europe from the steppe by Yamnaya-related migrations.” ref

“A 2022 study by Lazaridis et al. found that the typical phenotype among the Yamnaya population was brown eyes, brown hair, and intermediate skin color. None of their Yamnaya samples were predicted to have either blue eyes or blond hair, in contrast with later Steppe groups in Russia and Central Asia, as well as the Bell Beaker culture in Europe, who did carry these phenotypes in high proportions.” ref

The geneticist David Reich has argued that the genetic data supports the likelihood that the people of the Yamnaya culture were a “single, genetically coherent group” who were responsible for spreading many Indo-European languages. Reich’s group recently suggested that the source of Anatolian and Indo-European subfamilies of the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language may have been in west Asia, and the Yamna were responsible for the dissemination of the latter. Reich also argues that the genetic evidence shows that Yamnaya society was an oligarchy dominated by a small number of elite males.” ref

“The genetic evidence for the extent of the role of the Yamnaya culture in the spread of Indo-European languages has been questioned by Russian archaeologist Leo Klejn and Balanovsky et al., who note a lack of male haplogroup continuity between the people of the Yamnaya culture and the contemporary populations of Europe. Klejn has also suggested that the autosomal evidence does not support a Yamnaya migration, arguing that Western Steppe Herder ancestry in both contemporary and Bronze Age samples is lowest around the Danube in Hungary, near the western limits of the Yamnaya culture, and highest in Northern Europe, which Klejn argues is the opposite of what would be expected if the geneticists’ hypothesis is correct.” ref

“Marija Gimbutas identified the Yamnaya culture with the late Proto-Indo-Europeans (PIE) in her Kurgan hypothesis. In the view of David Anthony, the Pontic-Caspian steppe is the strongest candidate for the Urheimat (original homeland) of the Proto-Indo-European language, citing evidence from linguistics and genetics which suggests that the Yamnaya culture may be the homeland of the Indo-European languages, with the possible exception of the Anatolian languages. On the other hand, Colin Renfrew has argued for a Near Eastern origin of the earliest Indo-European speakers.” ref

“According to David W. Anthony, the genetic evidence suggests that the leading clans of the Yamnaya were of EHG (Eastern European hunter-gatherer) and WHG (Western European hunter-gatherer) paternal origin and implies that the Indo-European languages were the result of “a dominant language spoken by EHGs that absorbed Caucasus-like elements in phonology, morphology, and lexicon.” It has also been suggested that the PIE language evolved through trade interactions in the circum-Pontic area in the 4th millennium BCE, mediated by the Yamna predecessors in the North Pontic steppe.” ref

“Guus Kroonen et al. 2022 found that the “basal Indo-European stage”, also known as Indo-Anatolian or Pre-Proto-Indo-European language, largely but not totally, lacked agricultural-related vocabulary, and only the later “core Indo-European languages” saw an increase in agriculture-associated words. According to them, this fits a homeland of early core Indo-European within the westernmost Yamnaya horizon, around and west of the Dnieper, while its basal stage, Indo-Anatolian, may have originated in the Sredny Stog culture, as opposed to the eastern Yamnaya horizon.” ref

“The Corded Ware culture may have acted as major source for the spread of later Indo-European languages, including Indo-Iranian, while Tocharian languages may have been mediated via the Catacomb culture. They also argue that this new data contradicts a possible earlier origin of Pre-Proto-Indo-European among agricultural societies South of the Caucasus, rather “this may support a scenario of linguistic continuity of local non-mobile herders in the Lower Dnieper region and their genetic persistence after their integration into the successive and expansive Yamnaya horizon”. Furthermore the authors mention that this scenario can explain the difference in paternal haplogroup frequency between the Yamnaya and Corded Ware cultures, while both sharing similar autosomal DNA ancestry.” ref

In the Baltic, Jones et al. (2017) found that the Neolithic transition – the passage from a hunter-gatherer economy to a farming-based economy – coincided with the arrival en masse of individuals with Yamnaya-like ancestry. This is different from what happened in Western and Southern Europe, where the Neolithic transition was caused by a population that came from Anatolia, with Pontic steppe ancestry being detected from only the late Neolithic onward. Per Haak et al. (2015), the Yamnaya contribution in the modern populations of Eastern Europe ranges from 46.8% among Russians to 42.8% in Ukrainians. Finland has the highest Yamnaya contributions in all of Europe (50.4%).” ref

“Studies also point to the strong presence of Yamnaya descent in the current nations of South Asia, especially in groups that are referred to as Indo-Aryans. According to Pathak et al. (2018), the “North-Western Indian & Pakistani” populations (PNWI) showed significant Middle-Late Bronze Age Steppe (Steppe_MLBA) ancestry along with Yamnaya Early-Middle Bronze Age (Steppe_EMBA) ancestry, but the Indo-Europeans of Gangetic Plains and Dravidian people only showed significant Yamnaya (Steppe_EMBA) ancestry and no Steppe_MLBA. The study also noted that ancient south Asian samples had significantly higher Steppe_MLBA than Steppe_EMBA (or Yamnaya). The study identified the Rors and Jats as the population in South Asia with the highest proportion of Steppe ancestry.” ref

“Lazaridis et al. (2016) estimated (6.5–50.2 %) steppe-related admixture in South Asians, though the proportion of Steppe ancestry varies widely across ethnic groups. According to Narasimhan et al. (2019), the Yamnaya-related ancestry, termed Western_Steppe_EMBA, that reached central and south Asia was not the initial expansion from the steppe to the east, but a secondary expansion that involved a group possessing ~67% Western_Steppe_EMBA ancestry and ~33% ancestry from the European cline. This group included people similar to that of Corded Ware, Srubnaya, Petrovka, and Sintashta. Moving further east in the central steppe, it acquired ~9% ancestry from a group of people that possessed West Siberian Hunter Gatherer ancestry, thus forming the Central Steppe MLBA cluster, which is the primary source of steppe ancestry in South Asia, contributing up to 30% of the ancestry of the modern groups in the region.” ref

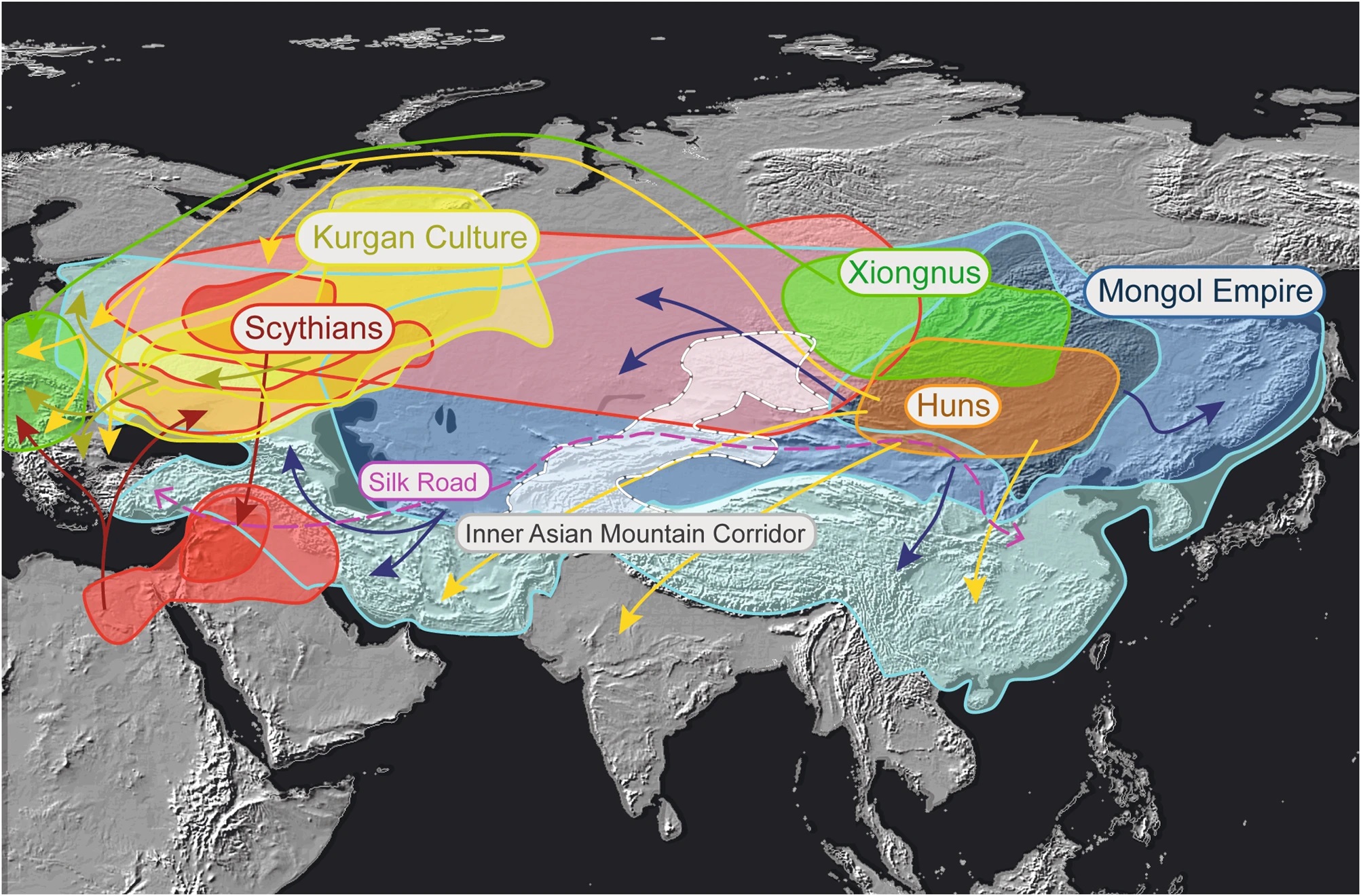

“According to Unterländer et al. (2017), all Iron Age Scythian Steppe nomads can best be described as a mixture of Yamnaya-related ancestry and an East Asian-related component, which most closely corresponds to the modern North Siberian Nganasan people of the lower Yenisey River, to varying degrees, but generally higher among Eastern Scythians.” ref

The Great Indo-European Horse Sacrifice

4000 Years of Cosmological Continuity from

Sintashta and the Steppe to Scandinavian Skeid

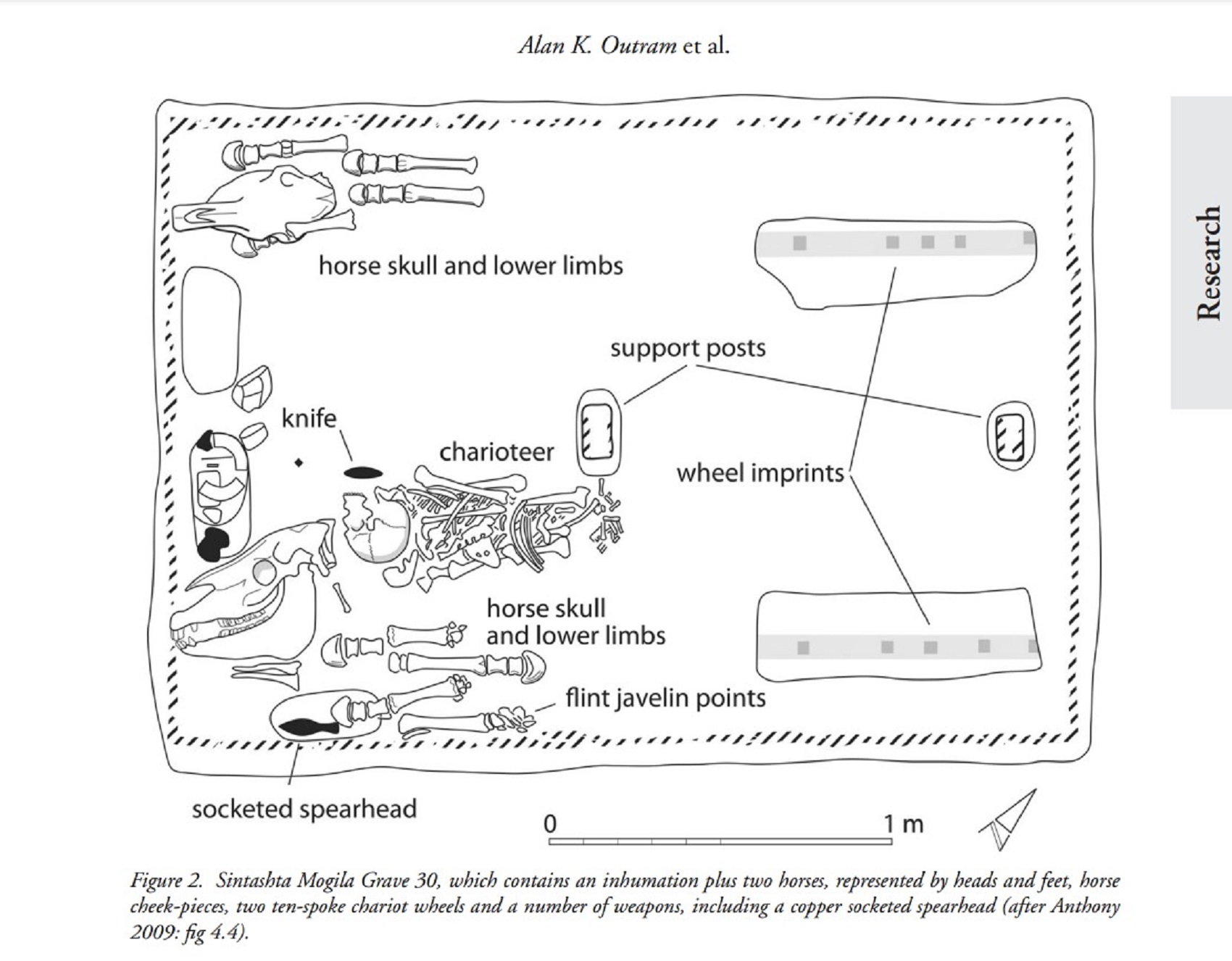

“The great Indo-European horse sacrifice is one of the most enduring and widespread traditions in world history. This study presents a historic overview of Indo-European studies and shows the cosmological continuity of the horse-sacrificial tradition based on specific cultural innovations and ecological adaptations over time. It also sheds new light on cultural history through in-depth analysis of horse sacrifice in culture and cosmology. From Sintashta in Russia and the steppes to the legendary ashwamedha ritual in India and horse sacrifices in Roman, Greek, and Irish traditions, the analysis

finds that horse sacrifice appears to have been most successful in Scandinavia, with classic sites and funerals such as Sagaholm, Kivik and Håga in the Bronze Age and Old Uppsala, Rakne, and Oseberg in the Iron Age. The horse-sacrifice tradition shows that these cosmological rituals were closely related to the region’s ecology, the weather, and the availability

of water that was required for a successful harvest. In the cold north, the sun was important for cultivation, but it was the relation between water and winter that defined the seasons and called for horse rituals, as recent skeid traditions show. Understanding horse sacrifice as an institution, therefore, provides new insights into prehistoric religion from the Bronze

Age to recent folklore in rural Scandinavia.” ref

“Indo-European horse-sacrifice is one of the world’s most ancient and widespread traditions. Researchers trace parts of the practice across large parts of Europe and Central Asia in the period ca. 2,100 BCE -1900 CE, albeit in culturally specific and changing forms. Moreover, the tradition also impacted social developments in many spheres, because this cosmogonic ritual embodied world views that affected most other spheres of lives and living.” ref

“First, traditions through time and the horse sacrifice as ‘ideal-type’. In a brief history of Indo-European studies on the great horse sacrifices, researchers will present Indian, Irish, Greek, and Roman sacrificial traditions and discuss how similarities across time and space have, for over a century, led different scholars to retrace these traditions to a common ‘protoIndo-European’ origin. This touches directly upon the many fundamental research challenges involved in analyzing such grand

rituals.” ref

“Second, creation of cosmos and world history. The great horse sacrifice was an act of cosmogony or the creation and maintenance of cosmos, which implies that, archaeologically, one has to address the relationship between myths and cosmology, on the one hand, and rituals and sacrifices, on the other hand. Apart from the fact that the creation of the cosmos is part of world history from a religious point of view, given the broad geographical and chronological spans, IndoEuropean studies are part of world history and global comparative archaeology. While there are many ways to write world history, this study places particular emphasis on Scandinavian archaeology and how Indo-European studies have been conducted and criticized until recently, as this is the region with the longest historical trajectories and continuity of the ancient horse rituals.” ref

“Third, ideal-types, theory, and method. Cross-cultural comparison in time and space has been widely criticized and has often been seen as a formal analogy. This brings us to current theoretical developments in archaeology: this study is situated in the broader field of interdisciplinary studies, combining ethnography and ethnology as the basis for developing ‘ideal-types’ for interpretative purposes. It also addresses the challenge of national archaeologies and nationalism, since the Indo-European question has defined history and heritage in various countries.” ref

Fourth, the meaning of the concept Indo-European – use and misuse. Coined in the 19th century, the concept of Indo-Europeanism has greatly contributed to disciplinary and interdisciplinary developments in academia. It was, however, also abused in 20th-century Europe, with grave consequences. It is important to be aware of the concept’s history and to critically identify intellectual and academic shortcomings in archaeological reasoning as nationalistic paradigms tend to resurface despite scientific progress. Given that the Indo-European concept was originally developed in relation to languages, it also examines the relation between language, culture, and cultural-historic processes.” ref

Fifth, the spread of Indo-Europeans, the clues of genetics, and a return to the classics. Thanks to the recent scientific revolution in aDNA analysis, many previous controversial interpretations about migration have now been validated. The new technology allows us to re-examine older excavations and recent archaeological finds to explore new connections and prehistoric realities. In this study, we will address the question of the Indo-European ‘homeland’ on the steppes north of the Black Sea. We will also address finds from the Sintashta site, east of the Ural Mountains in current-day Russia as well as other Asian contexts and their relation to the historic developments in India.” ref

Sixth, ashwamedha (Sanskrit for ‘horse sacrifice’). We will examine this Vedic prototype and the later Indian horse-sacrificing tradition in depth, as this ritual practice has been thoroughly documented and debated among Indologists and Indo-European scholars. The Vedic cosmogony and cosmology share many similarities with the Scandinavian Bronze-Age religion, with for instance the prominent role of the sun and its cyclic movement in relation to water. While the ashwamedha ritual is cultural history in itself, it may also help us understand older prototypes of the great Indo-European horse sacrifice and its associated rituals, the last traces of which we find in Scandinavia as late as the 19th century.” ref

Seventh, skeid – horse-fighting and horse-racing. The skeid tradition is documented in written sources, and the tradition can be traced back over the centuries. In Norway, the tradition survived until recently mainly in the most remote mountainous parts of the country, particularly in the form of horse racing and horse fighting. The stallions fought among themselves for a mare, which seems to be a relic of much older fertility rituals. However, in Sweden and large parts of Norway, the skeid tradition was mainly a horse race to St. Stephan’s well during Christmas, and most contemporary ethnographers and early scholars interpret this horse tradition as part of an earlier fertility and harvest cult. The Icelandic equivalent of skeid, described in medieval sources, is called Hestavíg. As in Norway, it consisted of a brutal and bloody

confrontation between two stallions, but the occasion was also used as an opportunity for courtship between young couples, to strengthen friendship or to settle issues among rivals.” ref

“Eight, Iron-Age horse sacrifices. The archaeological material and physical evidences of horse sacrifices are omnipresent in Norse cosmology. The Rakne Mound in Norway, the biggest grave mound in Scandinavia, can be interpreted in light of horse sacrifices. While the finds in Rakne are small, the Oseberg funeral includes numerous horse sacrifices. Analysis of some of the old material, also from Old Uppsala and other Iron Age sites in Sweden, may provide new insights into the

skeid tradition. While there are few written sources, they provide elaborate detail about issues such as the cult of volse. However, the iconography bears strong testimony to horse rituals; moreover, archaeological sites like Skedemose enable deeper insights into this ritual tradition. A close look at the variation in the archaeological material allows one to identify different sacrificial practices and how traditions changed over time, with direct continuities into the Bronze Age.” ref

“Ninth, Bronze-Age horse sacrifices. Great Bronze-Age graves such as Kivik, Sagaholm, and Håga can be better understood if the funerary and sacrificial remains and their cosmology are viewed through the Indo-European frame of great horse sacrifices. Many of the depictions on rock art can be understood in new ways, potentially opening up new entrances to understanding the role and relation between the sun, chariots, boats – and horses. Heaps of firecracked stones or burnt mounds may also be interpreted in this light, emphasising the sacrificial hierarchies in ritual practices. The most extensive and complicated Vedic fire sacrifice, Agnicayana, has been likened to the Scandinavian heaps of fire-cracked stones in other respects. Agnicayana is one of the Vedic ceremonies that form the basis of the horse sacrifice itself. The abundant presence of bones of animals other than horses in heaps of fire-cracked stones does not contradict the relationships. Although the horse is the main sacrificial animal, a great sacrifice and ritual may comprise of many minor sacrifices leading up to the main sacrifice. In one of the records describing the Vedic ashwamedha sacrifice, altogether 636 animals were sacrificed.” ref

“Tenth, the sun and its relation to water, weather, and winter. We will not only put forward new interpretations enriching the understanding of the prehistoric cosmology in Scandinavian Iron and Bronze Age, but also try to explain the reason for the strong prevalence of the great IndoEuropean horse sacrificial tradition in the north. In this cold region wealth and welfare is highly dependent on sunlight and the right combination of the sun and rain for a successful harvest during the short summer season. From an ecological perspective, one can identify a reversed rainmaking logic in fertility and harvest rituals. The horse sacrificing tradition was mainly a cosmic fertility ritual. In the cold north, the long winters form the greatest challenge: when will it come; how long will it last; and when will it end? While there were no summer

or winter gods or goddesses in Scandinavia, the winter was nevertheless ritually included in the overall cosmology.” ref

“Eleventh, cultural history and cosmology – Indo-European and Scandinavian traditions. Researchers aim to present ways to move from cross-cultural comparison to specific cultural-historic analyses and histories. Researchers relate our analysis to ongoing research traditions and explore how this approach may generate new knowledge on classical questions like Ragnarök and adaptation to climate change in time and space. As climate change implies changes in the relation between the sun (seasonality) and water (weather and winter), this was also a divine matter in prehistory because the gods controlled death and life-giving powers. We will also look at how particular cultural-historic processes may be studied independently of broader Indo-European formative forces, even though they are clearly Indo-European and can best be understood in this context in many cases. In short, studies of Scandinavian prehistory do not have to be Indo-European studies, although they are part of IndoEuropean processes.” ref

Predecessors to the Domestic Horse?

“A 2005 study analyzed the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of a worldwide range of equids, from 53,000-year-old fossils to contemporary horses. Their analysis placed all equids into a single clade, or group with a single common ancestor, consisting of three genetically divergent species: Hippidion, the New World stilt-legged horse, and equus, the true horse. The true horse included prehistoric horses and the Przewalski’s horse, as well as what is now the modern domestic horse, belonged to a single Holarctic species. The true horse migrated from the Americas to Eurasia via Beringia, becoming broadly distributed from North America to central Europe, north and south of Pleistocene ice sheets. It became extinct in Beringia around 14,200 years ago, and in the rest of the Americas around 10,000 years ago. This clade survived in Eurasia, however, and it is from these horses which all domestic horses appear to have descended. These horses showed little phylogeographic structure, probably reflecting their high degree of mobility and adaptability.” ref

“Therefore, the domestic horse today is classified as Equus ferus caballus. No genetic originals of native wild horses currently exist. The Przewalski diverged from the modern horse before domestication. It has 66 chromosomes, as opposed to 64 among modern domesticated horses, and their Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) forms a distinct cluster. Genetic evidence suggests that modern Przewalski’s horses are descended from a distinct regional gene pool in the eastern part of the Eurasian steppes, not from the same genetic group that gave rise to modern domesticated horses. Nevertheless, evidence such as the cave paintings of Lascaux suggests that the ancient wild horses that some researchers now label the “Tarpan subtype” probably resembled Przewalski horses in their general appearance: big heads, dun coloration, thick necks, stiff upright manes, and relatively short, stout legs.” ref

Shamanic horse tradition:

“The horse occupies a very special place in shamanic rituals and mythology. The horse – primarily a carrier of souls and a burial animal – is used by the shaman in various situations as a means of helping to achieve a state of ecstasy. It is known that the eight-legged horse is a typical shamanic attribute. Eight-hoofed or headless horses are recorded in mythology and rituals of Germanic and Japanese “male unions”. The horse is a mythical image of Death, it delivers the deceased to the other world, makes the transition from one world to another.” ref

“Throughout history, horses have been credited with the gift of clairvoyance, which allows them to see the invisible danger. Therefore, they are considered especially susceptible to witch conspiracies. In the old days, witches took them at night to go to the Sabbath, they rushed on them for a long time and returned at dawn exhausted and covered with sweat and foam. To thwart “witch racing”, witchcraft and the evil eye, horse owners put trinkets and amulets installs and attached copper bells to their reins. During the witch hunt, it was believed that the devil and the witch could turn into horses.” ref

Domestication of the horse

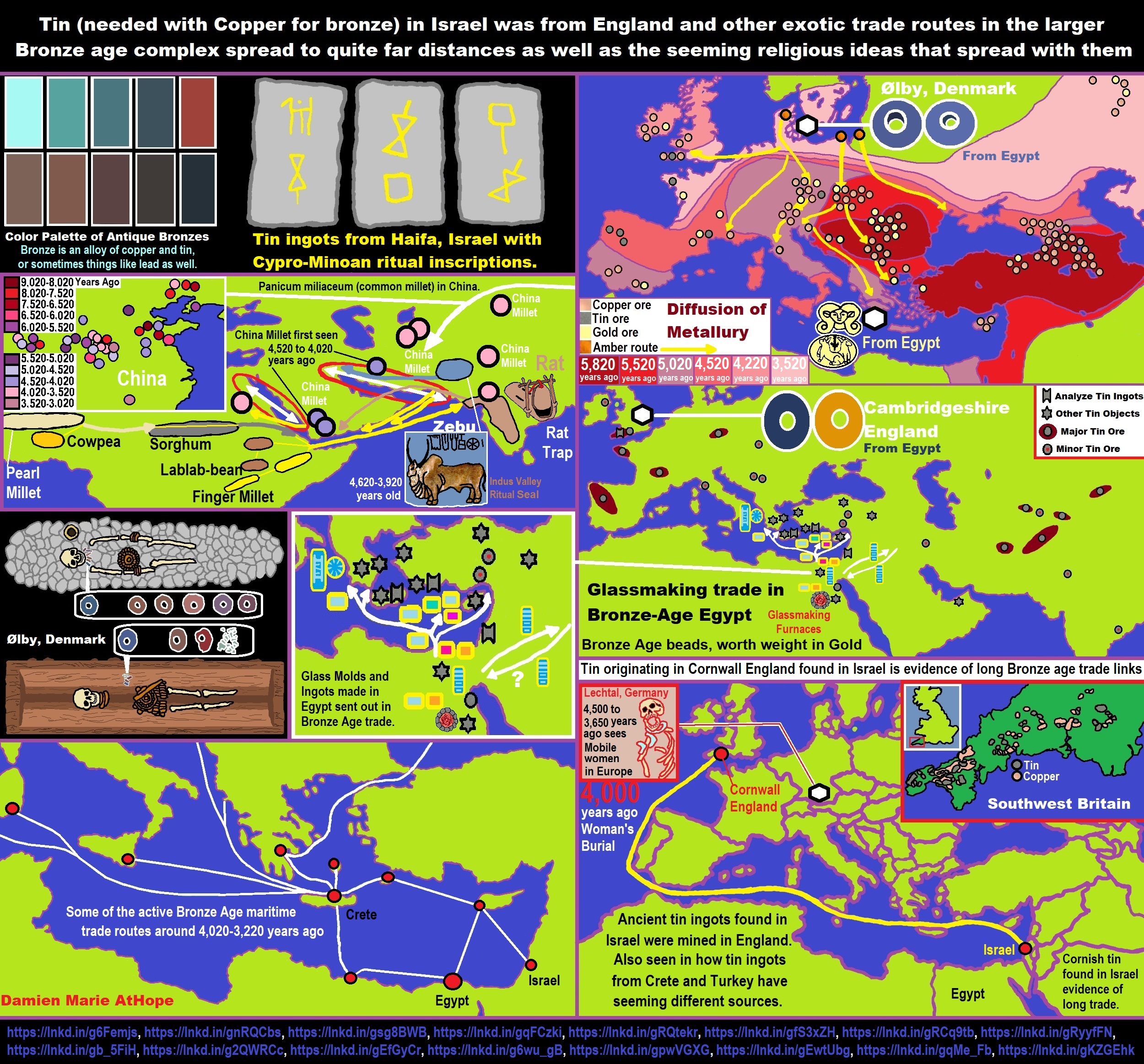

“A number of hypotheses exist on many of the key issues regarding the domestication of the horse. Although horses appeared in Paleolithic cave art as early as 30,000 BCE, these were wild horses and were probably hunted for meat. How and when horses became domesticated is disputed. The clearest evidence of early use of the horse as a means of transport is from chariot burials dated c. 2000 BCE. However, an increasing amount of evidence supports the hypothesis that horses were domesticated in the Eurasian Steppes approximately 3500 BCE or around 5,500 years ago or so; recent discoveries in the context of the Botai culture suggest that Botai settlements in the Akmola Province of Kazakhstan are the location of the earliest domestication of the horse. Use of horses spread across Eurasia for transportation, agricultural work, and warfare.” ref

“The date of the domestication of the horse depends to some degree upon the definition of “domestication”. Some zoologists define “domestication” as human control over breeding, which can be detected in ancient skeletal samples by changes in the size and variability of ancient horse populations. Other researchers look at the broader evidence, including skeletal and dental evidence of working activity; weapons, art, and spiritual artifacts; and lifestyle patterns of human cultures. There is also evidence that horses were kept as meat animals before they were trained as working animals.” ref

“Attempts to date domestication by genetic study or analysis of physical remains rests on the assumption that there was a separation of the genotypes of domesticated and wild populations. Such a separation appears to have taken place, but dates based on such methods can only produce an estimate of the latest possible date for domestication without excluding the possibility of an unknown period of earlier gene flow between wild and domestic populations (which will occur naturally as long as the domesticated population is kept within the habitat of the wild population). Further, all modern horse populations retain the ability to revert to a feral state, and all feral horses are of domestic types; that is, they descend from ancestors that escaped from captivity.” ref

“Whether one adopts the narrower zoological definition of domestication or the broader cultural definition that rests on an array of zoological and archaeological evidence affects the time frame chosen for the domestication of the horse. The date of 4000 BCE is based on evidence that includes the appearance of dental pathologies associated with bitting, changes in butchering practices, changes in human economies and settlement patterns, the depiction of horses as symbols of power in artifacts, and the appearance of horse bones in human graves. On the other hand, measurable changes in size and increases in variability associated with domestication occurred later, about 2500–2000 BCE, as seen in horse remains found at the site of Csepel-Haros in Hungary, a settlement of the Bell Beaker culture.” ref

“Use of horses spread across Eurasia for transportation, agricultural work, and warfare. Horses and mules in agriculture used a breastplate type harness or a yoke more suitable for oxen, which was not as efficient at utilizing the full strength of the animals as the later-invented padded horse collar that arose several millennia later.” ref

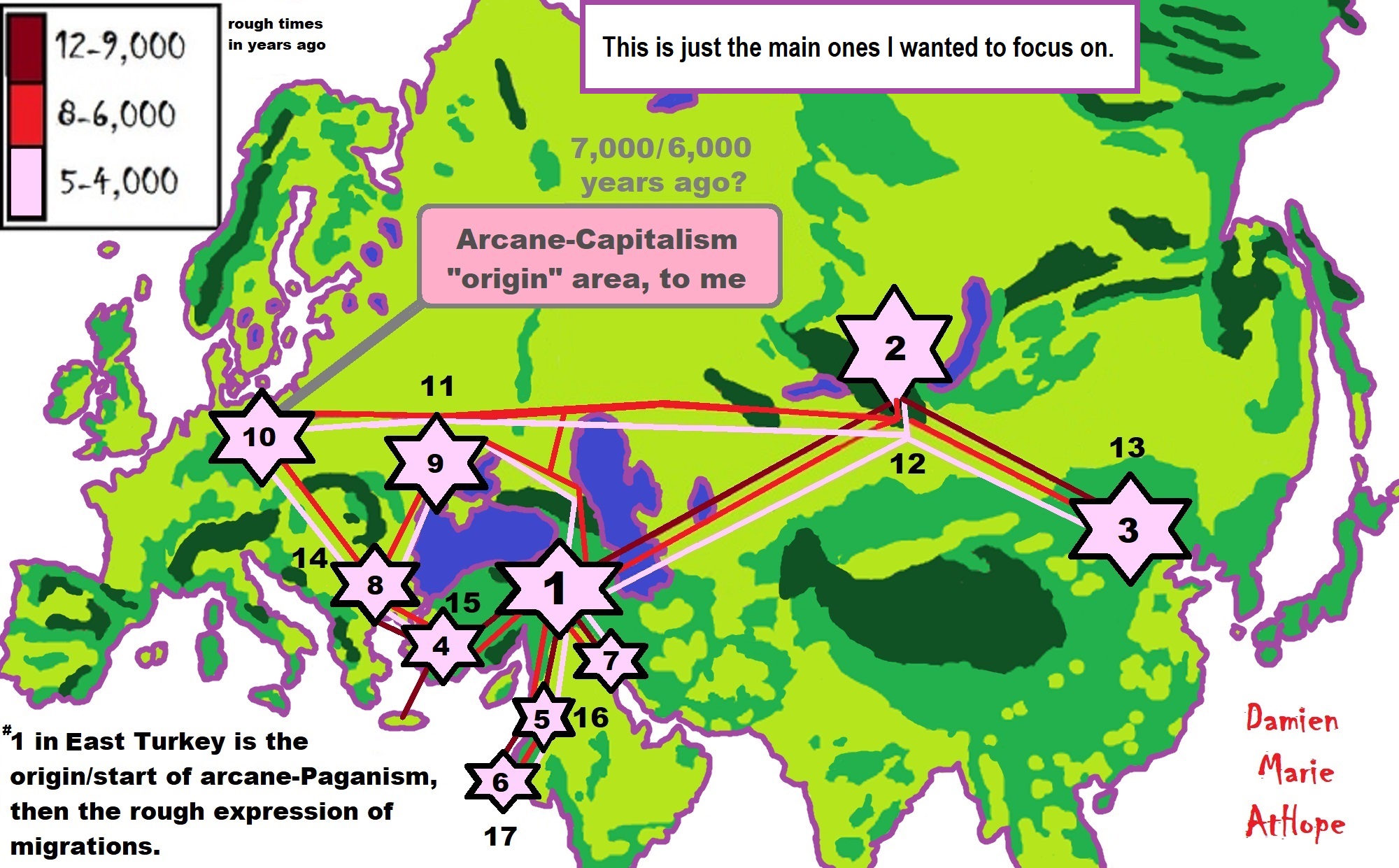

I think it possible that Proto-Indo-Europian language starts 7,022-6,022 and the time of kings could start around, an overlapping time, or with/reason-behind Horse burials that start as 6,022-5,522 years ago.

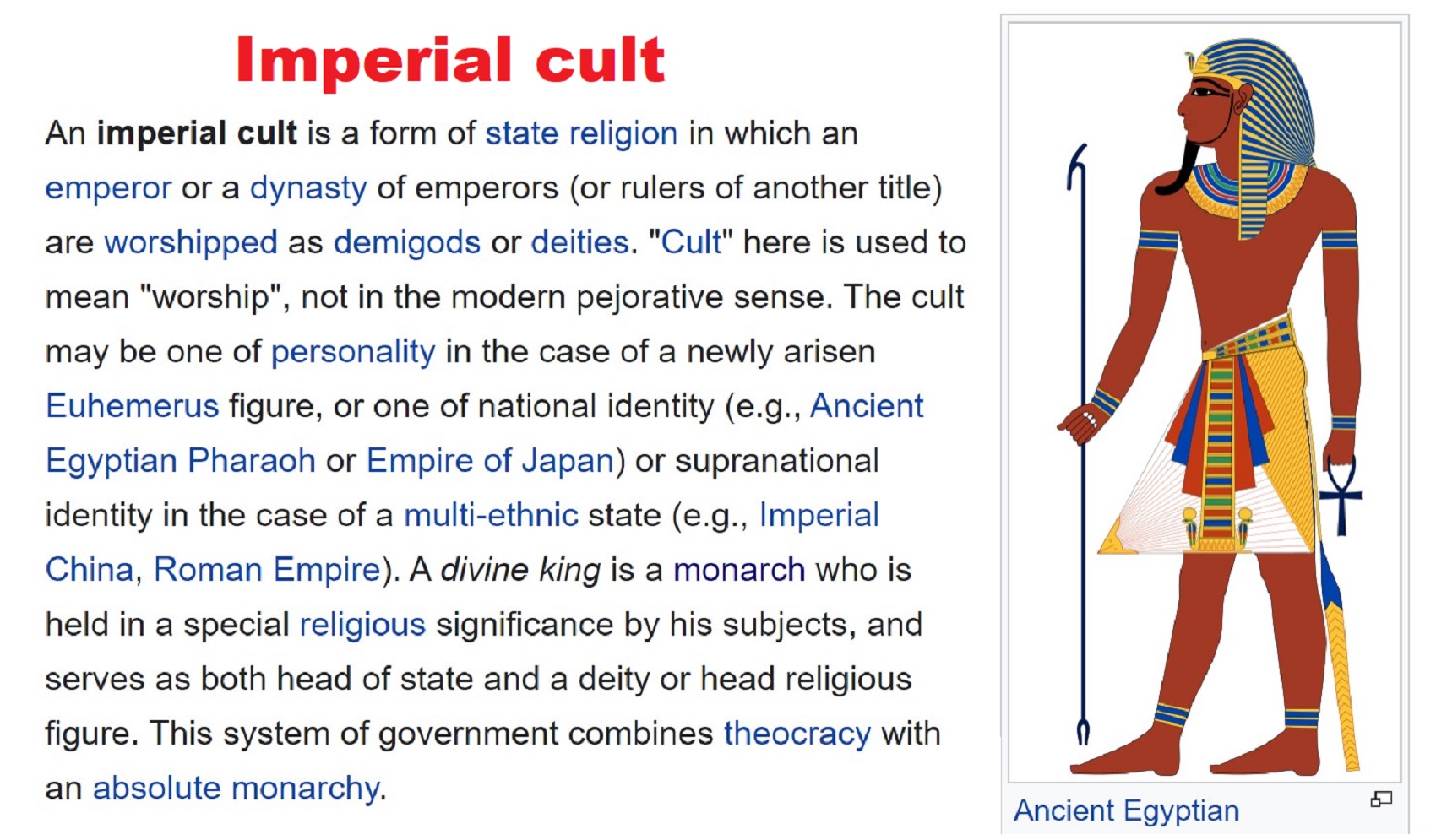

“A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy), to fully autocratic (absolute monarchy), and can expand across the domains of the executive, legislative, and judicial. Monarchs can carry various titles such as emperor, empress, king, queen, raja, khan, tsar, sultan, shah, or pharaoh. The succession of monarchs is in most cases hereditary, often building dynastic periods. However, elective and self-proclaimed monarchies are possible. Aristocrats, though not inherent to monarchies, often serve as the pool of persons to draw the monarch from and fill the constituting institutions (e.g. diet and court), giving many monarchies oligarchic elements.” ref

“Most historians have suggested that Sumer was first permanently settled between 5500 and 4000 BCE so 7,533-4,022 years ago by a West Asian people who spoke the Sumerian language (pointing to the names of cities, rivers, basic occupations, etc., as evidence), thought to be a non-Semitic and non-Indo-European agglutinative language isolate. In contrast to its Semitic neighbors, it was not an inflected language. However, Sumerian civilization took form in the Uruk period (4th millennium BCE 6,022-5,022 years ago), continuing into the Jemdet Nasr and Early Dynastic periods.” ref

“The word “monarch” (Late Latin: monarchia) comes from the Ancient Greek word μονάρχης (monárkhēs), derived from μόνος (mónos, “one, single”) and ἄρχω (árkhō, “to rule”): compare ἄρχων (árkhōn, “ruler, chief”). It referred to a single at least nominally absolute ruler. In current usage the word monarchy usually refers to a traditional system of hereditary rule, as elective monarchies are quite rare.” ref

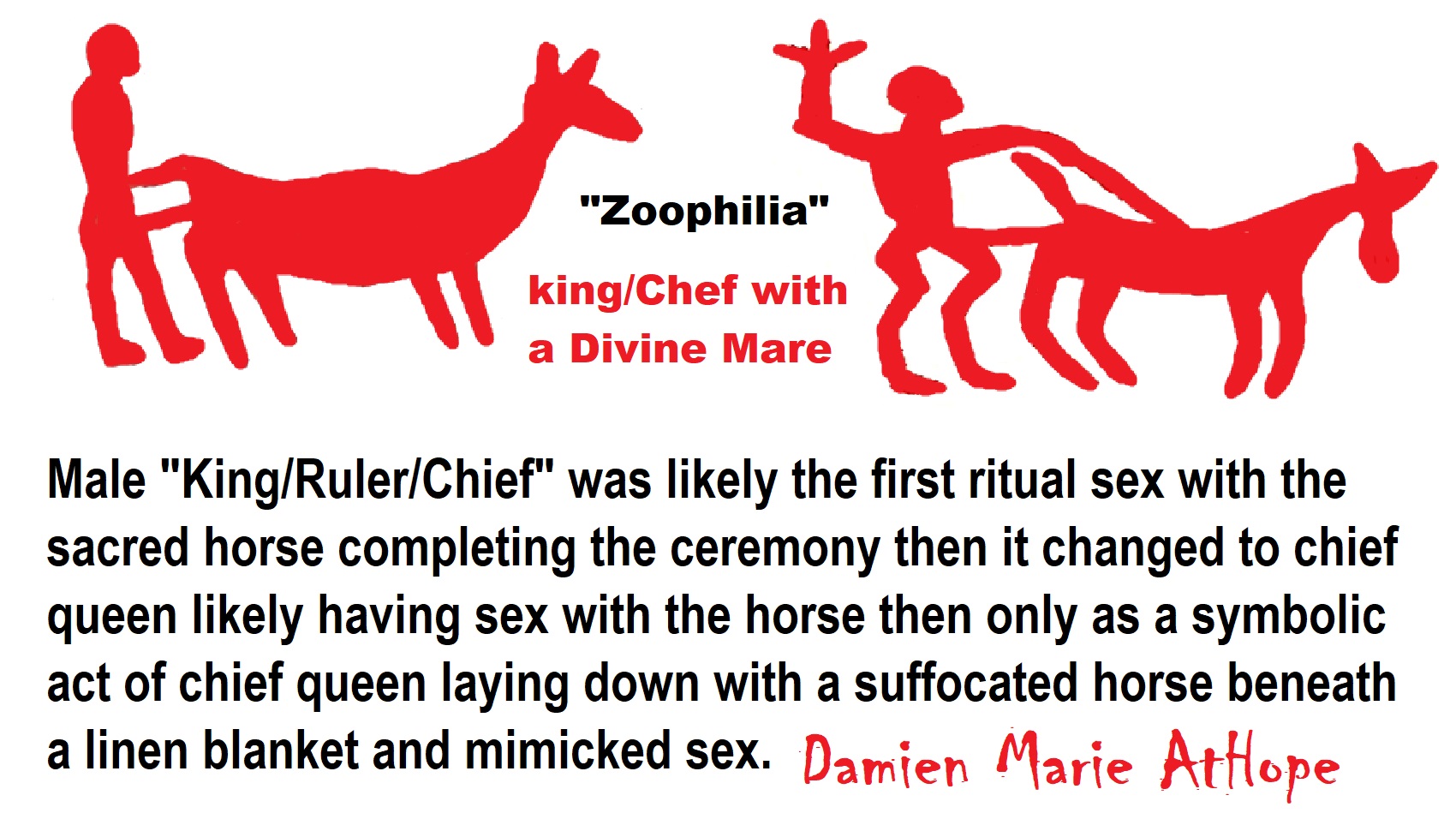

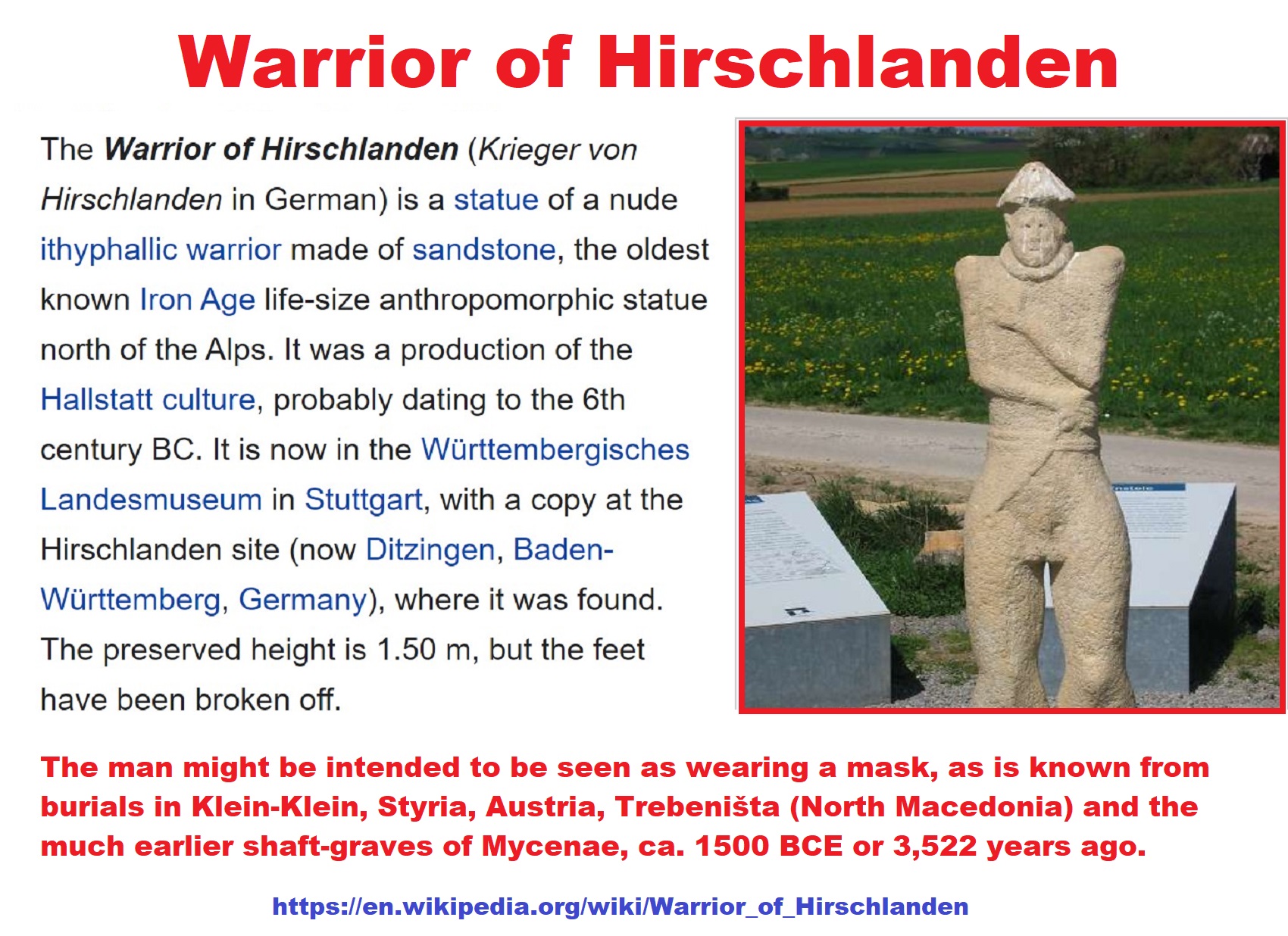

Male “King/Ruler/Chief” was likely the first ritual sex with the sacred horse completing the ceremony then it changed to chief queen likely having sex with the horse then only as a symbolic act of chief queen laying down with a suffocated horse beneath a linen blanket and mimicked sex.

“Man/god with horse-sized penis participating in royal/fertility ritual? Indo-European horse-sacrifice is one of the world’s most ancient and widespread traditions. The great Indo-European tradition of horse sacrifice in a 4000-year historic context, from the Sintashta culture in Russia in the east to historical Scandinavia in the west. In a brief history of Indo-European studies on the great horse sacrifices, we will present Indian, Irish, Greek, and Roman sacrificial traditions and

discuss how similarities across time and space have, for over a century, led different scholars to retrace these traditions to a common ‘Proto-Indo-European’ origin.” ref

Mythology: Horse worship and White horse (mythology)

“The reconstructed myth involves the coupling of a king with a divine mare which produced the divine twins. A related myth is that of a hero magically twinned with a horse foaled at the time of his birth (for example Cuchulainn, Pryderi), suggested to be fundamentally the same myth as that of the divine twin horsemen by the mytheme of a “mare-suckled” hero from Greek and medieval Serbian evidence, or mythical horses with human traits (Xanthos), suggesting totemic identity of the hero or king with the horse.” ref

Vedic (Indian): Ashvamedha

“Ashvamedha was a political ritual that was focused on the king’s right to rule. The horse had to be a stallion and it would be permitted to wander for a year, accompanied by people of the king. If the horse roamed off into lands of an enemy then that territory would be taken by the king, and if the horse’s attendants were killed in a fight by a challenger then the king would lose the right to rule. But if the horse stayed alive for a year then it was taken back to the king’s court where it was bathed, consecrated with butter, decorated with golden ornaments, and then sacrificed. After the completion of this ritual, the king would be considered as the undisputed ruler of the land which was covered by the horse.” ref

- “the sacrifice is connected with the elevation or inauguration of a member of the Kshatriya warrior caste

- the ceremony took place in spring or early summer

- the horse sacrificed was a stallion which won a race at the right side of the chariot

- the horse sacrificed was white-colored with dark circular spots, or with a dark front part, or with a tuft of dark blue hair

- it was bathed in water, in which mustard and sesame are mixed

- it was suffocated alongside a hornless ram and a he-goat, among other animals

- the chief queen lay down with the suffocated horse beneath a linen blanket and mimicked sexual intercourse with it, while the other queens perambulated the scene, slapping their thighs and fanning themselves

- the stallion was dissected along the “knife-paths” — with three knives made from gold, copper, and iron — and its portions awarded to various deities, symbolically invoking sky, atmosphere, and earth, while other priests started reciting the verses of Vedas, seeking healing and rejuvenation for the horse.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

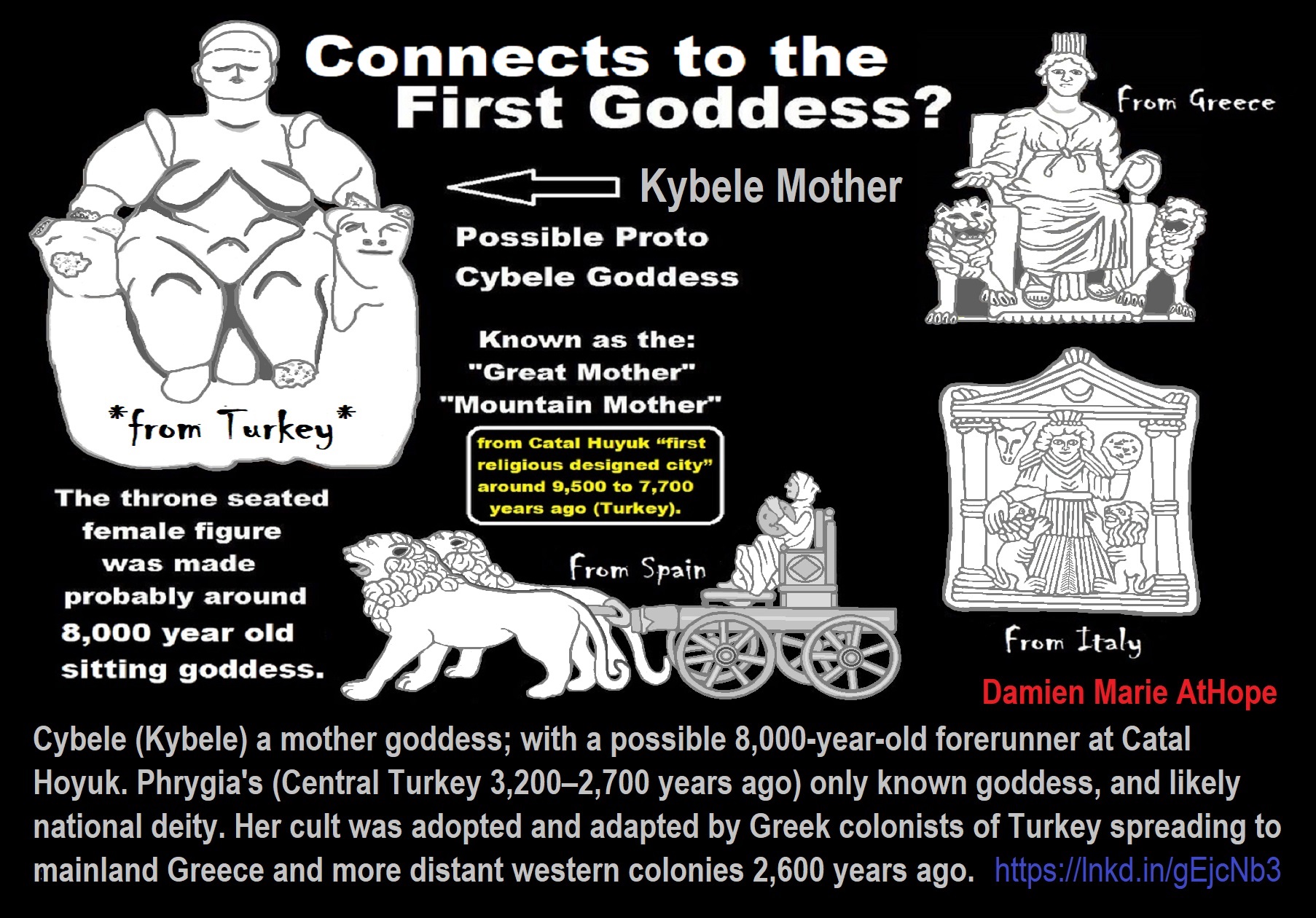

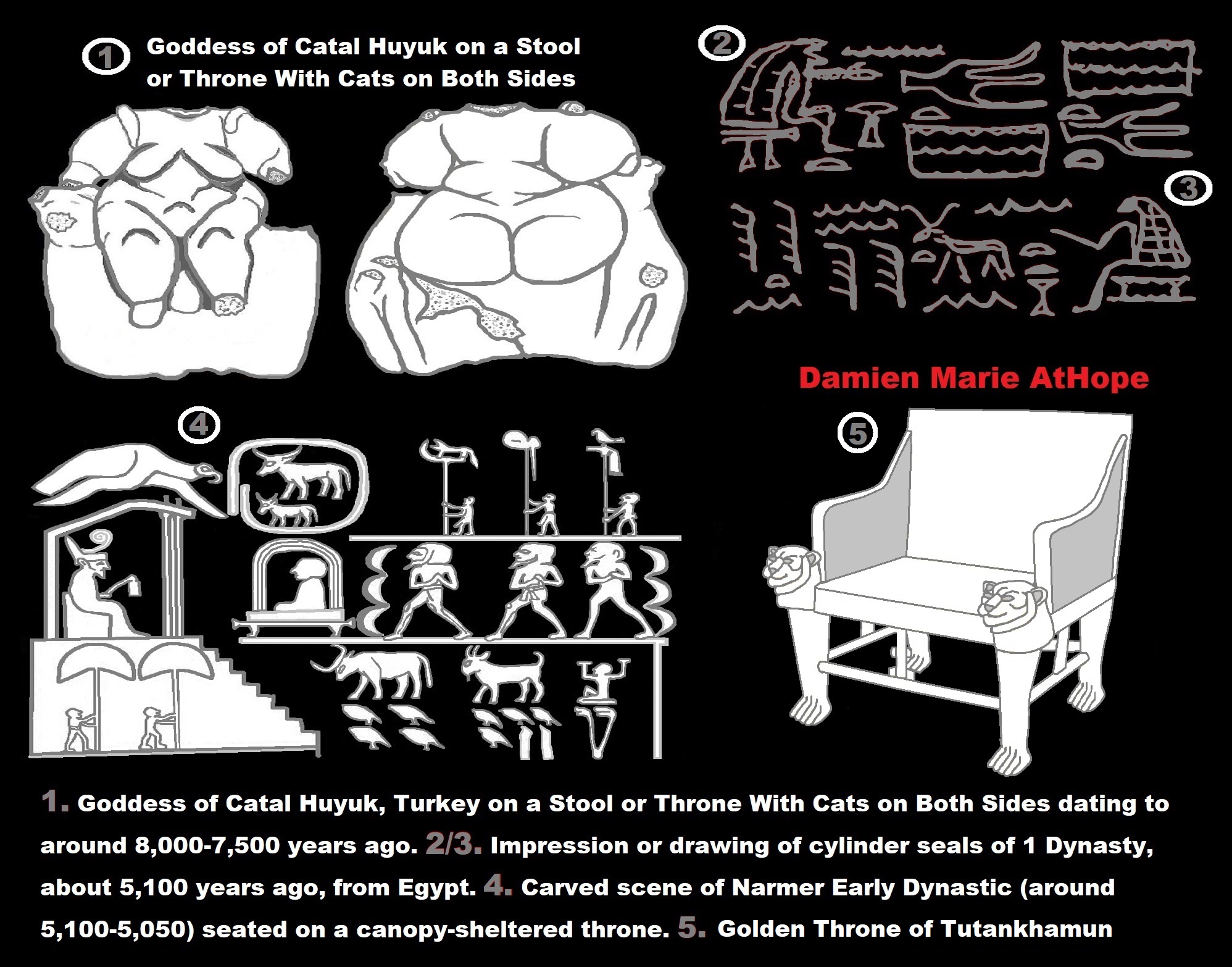

Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük

“The Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük (also Çatal Höyük) is a baked-clay, nude female form, seated between feline-headed arm-rests. It is generally thought to depict a corpulent and fertile Mother goddess in the process of giving birth while seated on her throne, which has two hand rests in the form of feline (lioness, leopard, or panther) heads in a Mistress of Animals motif. The statuette, one of several iconographically similar ones found at the site, is associated to other corpulent prehistoric goddess figures, of which the most famous is the Venus of Willendorf. It is a neolithic sculpture shaped by an unknown artist, and was completed in approximately 6000 BCE.” ref

Kubaba

“Kubaba is the only queen on the Sumerian King List, which states she reigned for 100 years – roughly in the Early Dynastic III period (ca. 2500–2330 BCE) of Sumerian history. A connection between her and a goddess known from Hurro–Hittite and later Luwian sources cannot be established on the account of spatial and temporal differences. Kubaba is one of very few women to have ever ruled in their own right in Mesopotamian history. Most versions of the king list place her alone in her own dynasty, the 3rd Dynasty of Kish, following the defeat of Sharrumiter of Mari, but other versions combine her with the 4th dynasty, that followed the primacy of the king of Akshak. Before becoming monarch, the king list says she was an alewife, brewess or brewster, terms for a woman who brewed alcohol.” ref

“Kubaba was a Syrian goddess associated particularly closely with Alalakh and Carchemish. She was adopted into the Hurrian and Hittite pantheons as well. After the fall of the Hittite empire, she continued to be venerated by Luwians. A connection between her and the similarly named legendary Sumerian queen Kubaba of Kish, while commonly proposed, cannot be established due to spatial and temporal differences. Emmanuel Laroche proposed in 1960 that Kubaba and Cybele were one and the same. This view is supported by Mark Munn, who argues that the Phrygian name Kybele developed from Lydian adjective kuvavli, first changed into kubabli and then simplified into kuballi, and finally kubelli. However, such an adjective is a purely speculative construction.” ref

Cybele

“Cybele (Phrygian: “Kubileya/Kubeleya Mother”, perhaps “Mountain Mother”) is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible forerunner in the earliest neolithic at Çatalhöyük, where statues of plump women, sometimes sitting, have been found in excavations. Phrygia‘s only known goddess, she was probably its national deity. Greek colonists in Asia Minor adopted and adapted her Phrygian cult and spread it to mainland Greece and to the more distant western Greek colonies around the 6th century BCE. In Greece, Cybele met with a mixed reception. She became partially assimilated to aspects of the Earth-goddess Gaia, of her possibly Minoan equivalent Rhea, and of the harvest–mother goddess Demeter. Some city-states, notably Athens, evoked her as a protector, but her most celebrated Greek rites and processions show her as an essentially foreign, exotic mystery-goddess who arrives in a lion-drawn chariot to the accompaniment of wild music, wine, and a disorderly, ecstatic following.” ref

“Uniquely in Greek religion, she had a eunuch mendicant priesthood. Many of her Greek cults included rites to a divine Phrygian castrate shepherd-consort Attis, who was probably a Greek invention. In Greece, Cybele became associated with mountains, town and city walls, fertile nature, and wild animals, especially lions. In Rome, Cybele became known as Magna Mater (“Great Mother”). The Roman State adopted and developed a particular form of her cult after the Sibylline oracle in 205 BCE recommended her conscription as a key religious ally in Rome’s second war against Carthage (218 to 201 BCE). Roman mythographers reinvented her as a Trojan goddess, and thus an ancestral goddess of the Roman people by way of the Trojan prince Aeneas. As Rome eventually established hegemony over the Mediterranean world, Romanized forms of Cybele’s cults spread throughout Rome’s empire. Greek and Roman writers debated and disputed the meaning and morality of her cults and priesthoods, which remain controversial subjects in modern scholarship.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

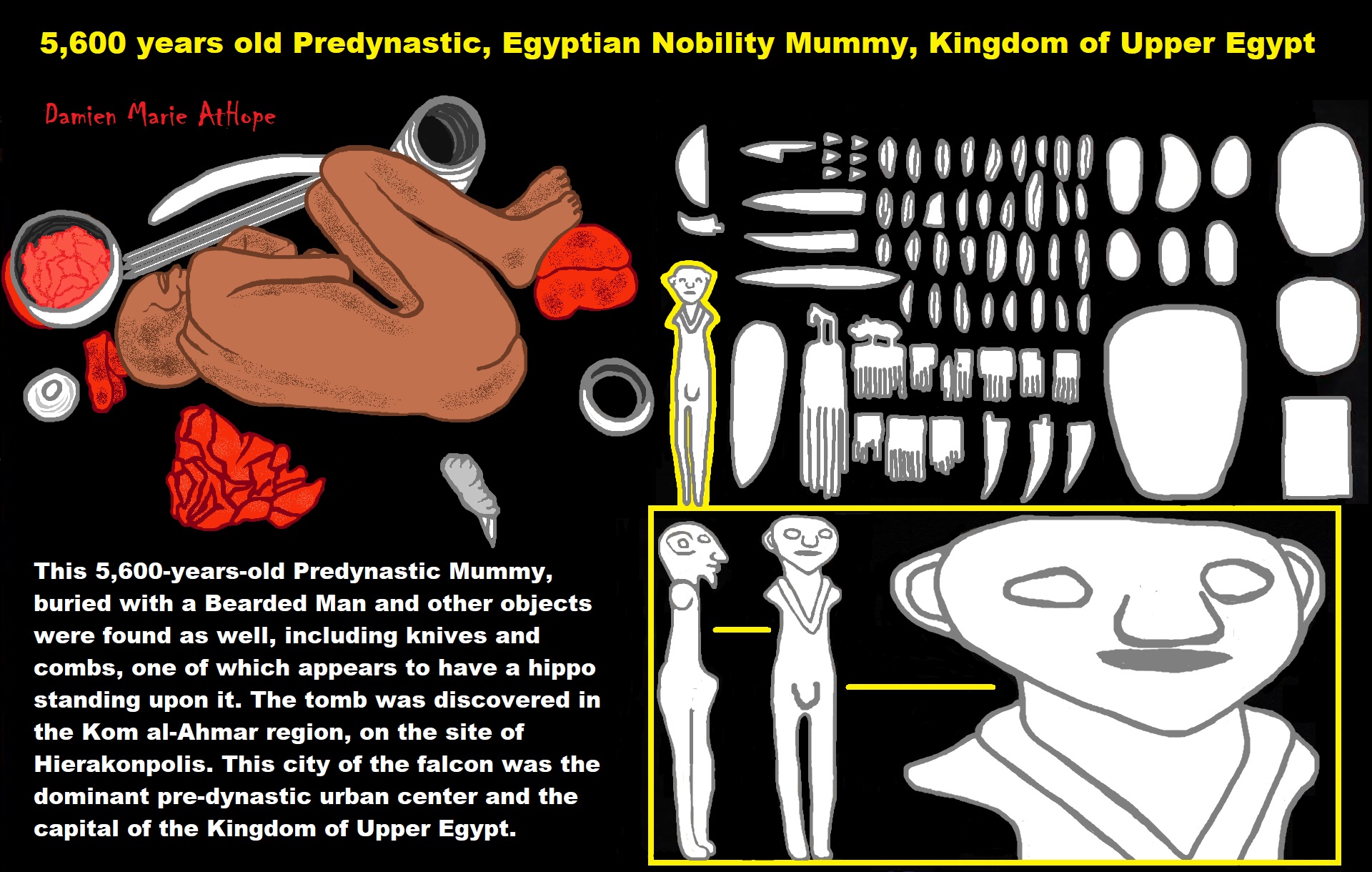

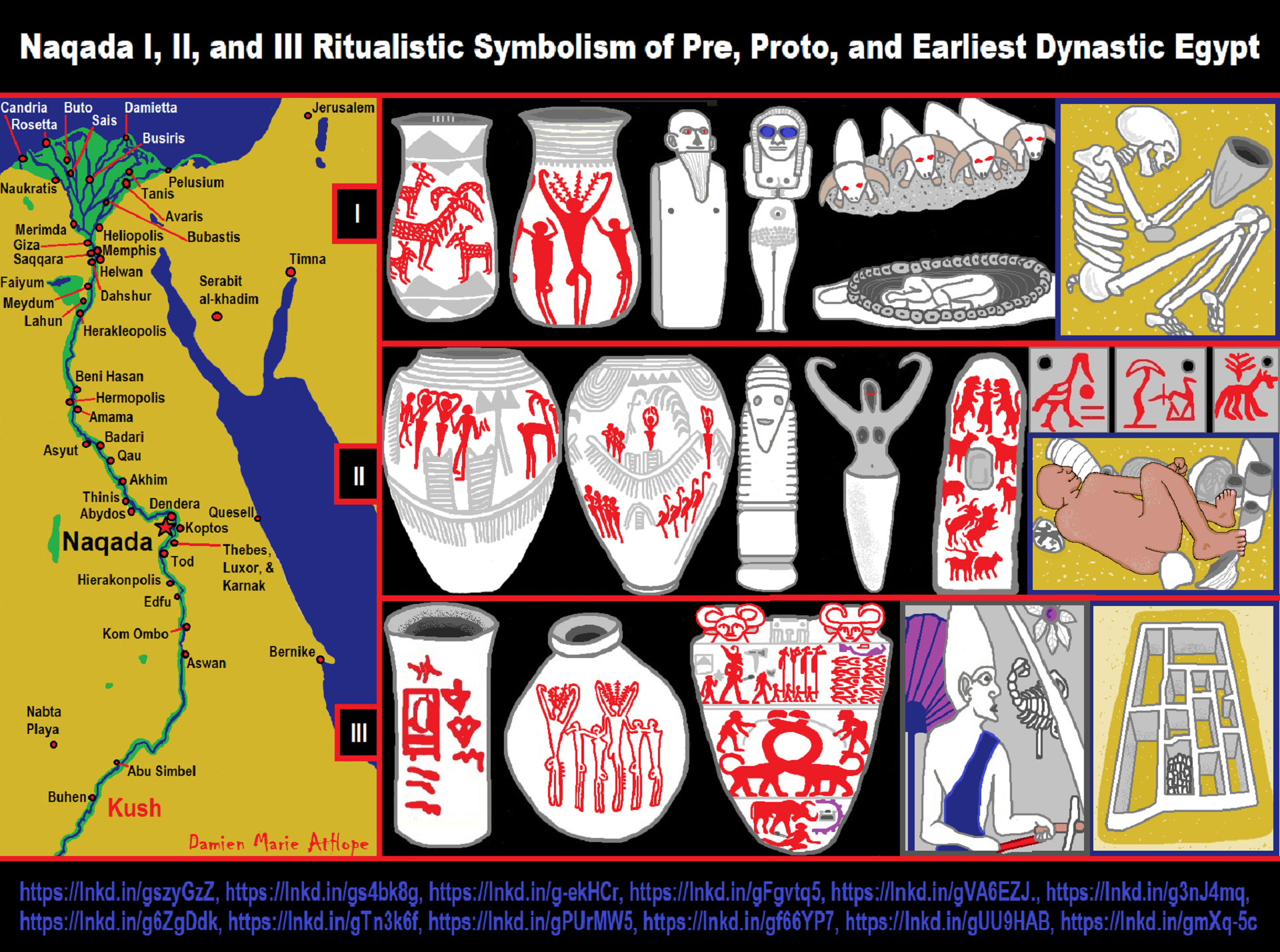

“Naqada stands near the site of a prehistoric Egyptian necropolis: The town was the center of the cult of Set and large tombs were built there c. 3500 BCE. The large quantity of remains from Naqada have enabled the dating of the entire archeological period throughout Egypt and environs, hence the town name Naqada is used for the pre-dynastic Naqada culture c. 4400–3000 BCE. Other Naqada culture archeological sites include el Badari, the Gerzeh culture, and Nekhen.” ref

“The Naqada culture is an archaeological culture of Chalcolithic Predynastic Egypt (c. 4000–3000 BCE), named for the town of Naqada, Qena Governorate. A 2013 Oxford University dating study of the Predynastic period suggests a beginning date sometime between 3,800 and 3,700 BCE. The final phase of the Naqada culture is Naqada III, which is coterminous with the Protodynastic Period (Early Bronze Age c. 3200–3000 BCE) in ancient Egypt.” ref

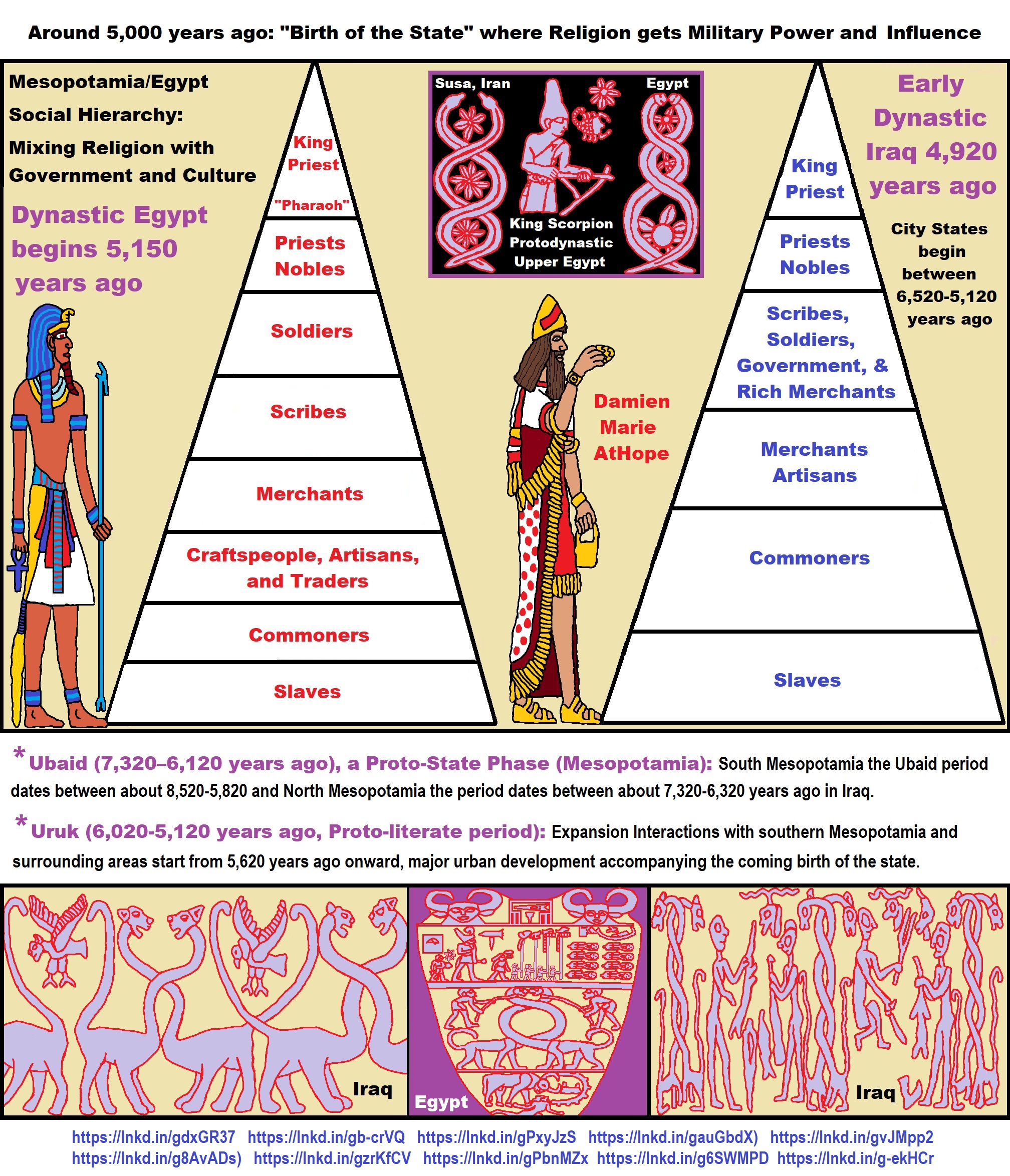

Ancient Egypt Monarch 3100 BCE or 5,122 years ago

“Monarchies are thought to be preceded by the similar form of prehistoric societal hierarchy known as chiefdom or tribal kingship. Chiefdoms are identified as having formed monarchic states, as in civilizations such as Mesopotamia, Ancient Egypt, and the Indus Valley Civilization. In some parts of the world, chiefdoms became monarchies. Some of the oldest recorded and evidenced monarchies were Narmer, Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt c. 3100 BCE, and Enmebaragesi, a Sumerian King of Kish c. 2600 BCE.” ref

“From earliest records, monarchs could be directly hereditary, while others were elected from among eligible members. With the Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Sudanic, reconstructed Proto-Indo-European religion, and others, the monarch held sacral functions directly connected to sacrifice and was sometimes identified with having divine ancestry, possibly establishing a notion of the divine right of kings.” ref

“Polybius identified monarchy as one of three “benign” basic forms of government (monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy), opposed to the three “malignant” basic forms of government (tyranny, oligarchy, and ochlocracy). The monarch in classical antiquity is often identified as “king” or “ruler” (translating archon, basileus, rex, tyrannos, etc.) or as “queen” (basilinna). Polybius originally understood monarchy as a component of republics, but since antiquity monarchy has contrasted with forms of republic, where executive power is wielded by free citizens and their assemblies. The 4th-century BCE Hindu text Arthasastra laid out the ethics of monarchism. In antiquity, some monarchies were abolished in favor of such assemblies in Rome (Roman Republic, 509 BCE), and Athens (Athenian democracy, 500 BCE).” ref

“By the 17th century, monarchy was challenged by evolving parliamentarism e.g. through regional assemblies (such as the Icelandic Commonwealth, the Swiss Landsgemeinde and later Tagsatzung, and the High Medieval communal movement linked to the rise of medieval town privileges) and by modern anti-monarchism e.g. of the temporary overthrow of the English monarchy by the Parliament of England in 1649, the American Revolution of 1776 and the French Revolution of 1789. One of many opponents of that trend was Elizabeth Dawbarn, whose anonymous Dialogue between Clara Neville and Louisa Mills, on Loyalty (1794) features “silly Louisa, who admires liberty, Tom Paine and the US, [who is] lectured by Clara on God’s approval of monarchy” and on the influence, women can exert on men.” ref

“Since then advocacy of the abolition of a monarchy or respectively of republics has been called republicanism, while the advocacy of monarchies is called monarchism. As such republics have become the opposing and alternative form of government to monarchy, despite some having seen infringements through lifelong or even hereditary heads of state.” ref

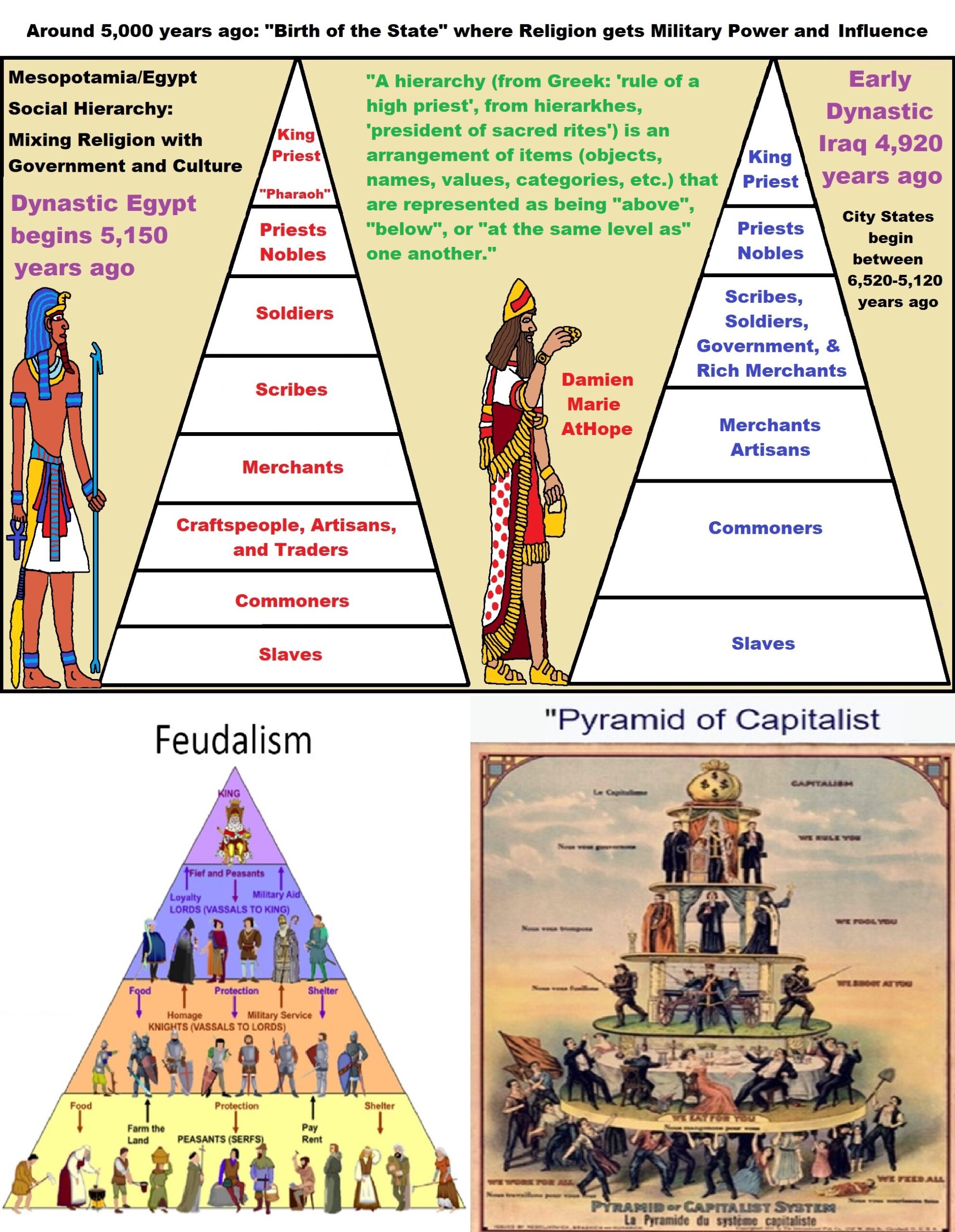

The Early Dynastic Period for Mesopotamia is around 2900–2350 BCE or 4,922-4,372 years ago

“The Early Dynastic period (abbreviated ED period or ED) is an archaeological culture in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) that is generally dated to c. 2900–2350 BCE and was preceded by the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods. It saw the development of writing and the formation of the first cities and states. The ED itself was characterized by the existence of multiple city-states: small states with a relatively simple structure that developed and solidified over time. This development ultimately led to the unification of much of Mesopotamia under the rule of Sargon, the first monarch of the Akkadian Empire. Despite this political fragmentation, the ED city-states shared a relatively homogeneous material culture. Sumerian cities such as Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Umma, and Nippur located in Lower Mesopotamia were very powerful and influential. To the north and west stretched states centered on cities such as Kish, Mari, Nagar, and Ebla.” ref

“The study of Central and Lower Mesopotamia has long been given priority over neighboring regions. Archaeological sites in Central and Lower Mesopotamia—notably Girsu but also Eshnunna, Khafajah, Ur, and many others—have been excavated since the 19th century. These excavations have yielded cuneiform texts and many other important artifacts. As a result, this area was better known than neighboring regions, but the excavation and publication of the archives of Ebla have changed this perspective by shedding more light on surrounding areas, such as Upper Mesopotamia, western Syria, and southwestern Iran. These new findings revealed that Lower Mesopotamia shared many socio-cultural developments with neighboring areas and that the entirety of the ancient Near East participated in an exchange network in which material goods and ideas were being circulated.” ref

I don’t agree with saying socialism is like the divine right to rule which relates to kings and elite along with horse burials, relating to 6,000 years old Proto-Indo-European religion.

“King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king. The term king may also refer to a king consort, a title that is sometimes given to the husband of a ruling queen, but the title of prince consort is more common. The English word is of Germanic origin, and historically refers to Germanic kingship, in the pre-Christian period a type of tribal kingship. The monarchies of Europe in the Christian Middle Ages derived their claim from Christianisation and the divine right of kings, partly influenced by the notion of sacral kingship inherited from Germanic antiquity.” ref

- “In the context of prehistory, antiquity, and contemporary indigenous peoples, the title may refer to tribal kingship. Germanic kingship is cognate with Indo-European traditions of tribal rulership (c.f. Indic rājan, Gothic reiks, and Old Irish rí, etc.).

- In the context of classical antiquity, king may translate in Latin as rex and in Greek as archon or basileus.

- In classical European feudalism, the title of king as the ruler of a kingdom is understood to be the highest rank in the feudal order, potentially subject, at least nominally, only to an emperor (harking back to the client kings of the Roman Republic and Roman Empire).

- In a modern context, the title may refer to the ruler of one of a number of modern monarchies (either absolute or constitutional). The title of king is used alongside other titles for monarchs: in the West, emperor, grand prince, prince, archduke, duke or grand duke, and in the Islamic world, malik, sultan, emir or hakim, etc.

- The city-states of the Aztec Empire had a Tlatoani, which were kings of pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica. The Huey Tlatoani was the emperor of the Aztecs.” ref

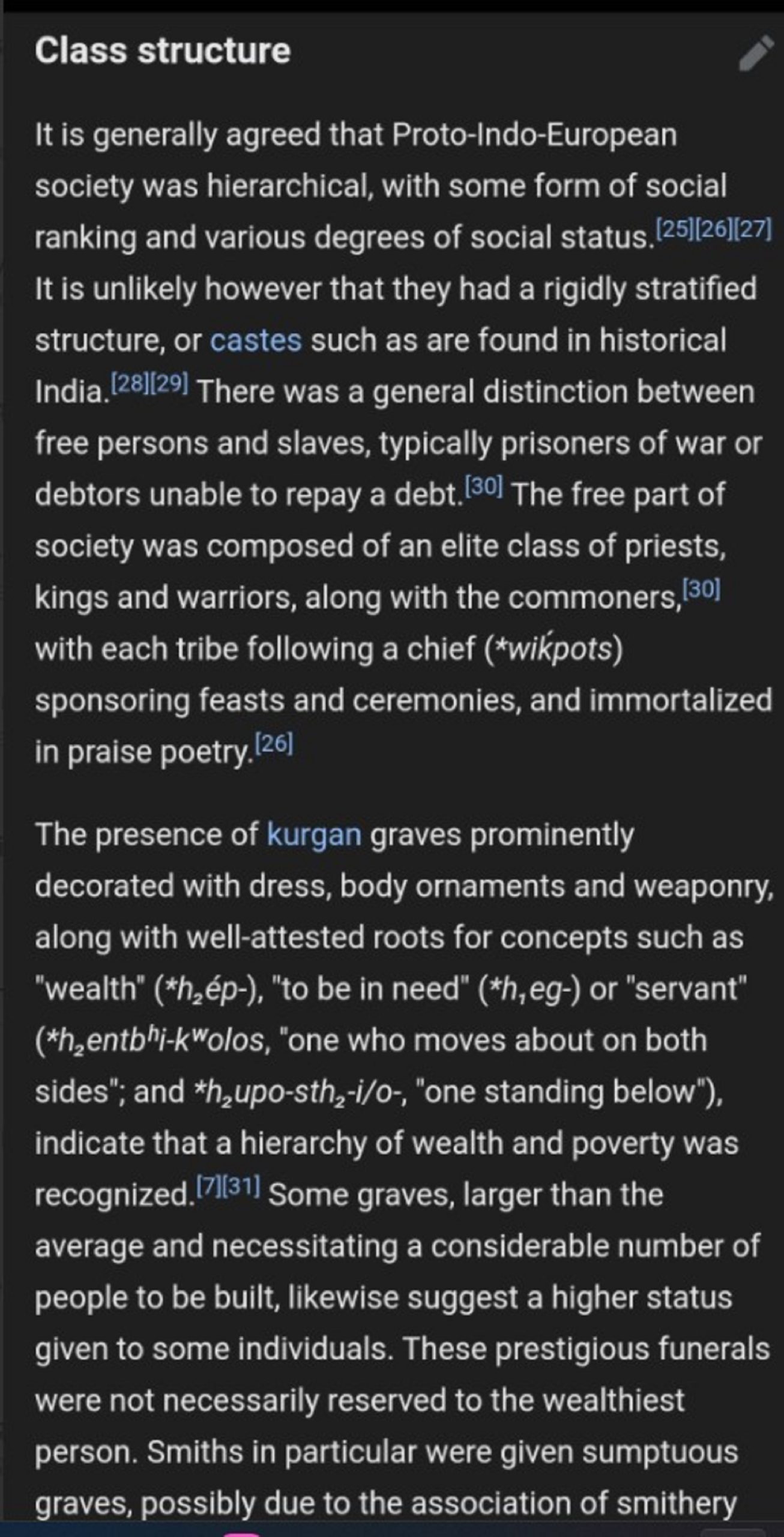

Proto-Indo-European class structure ref

Horse burial and kingship relate as well as the divine right to rule theme. ref

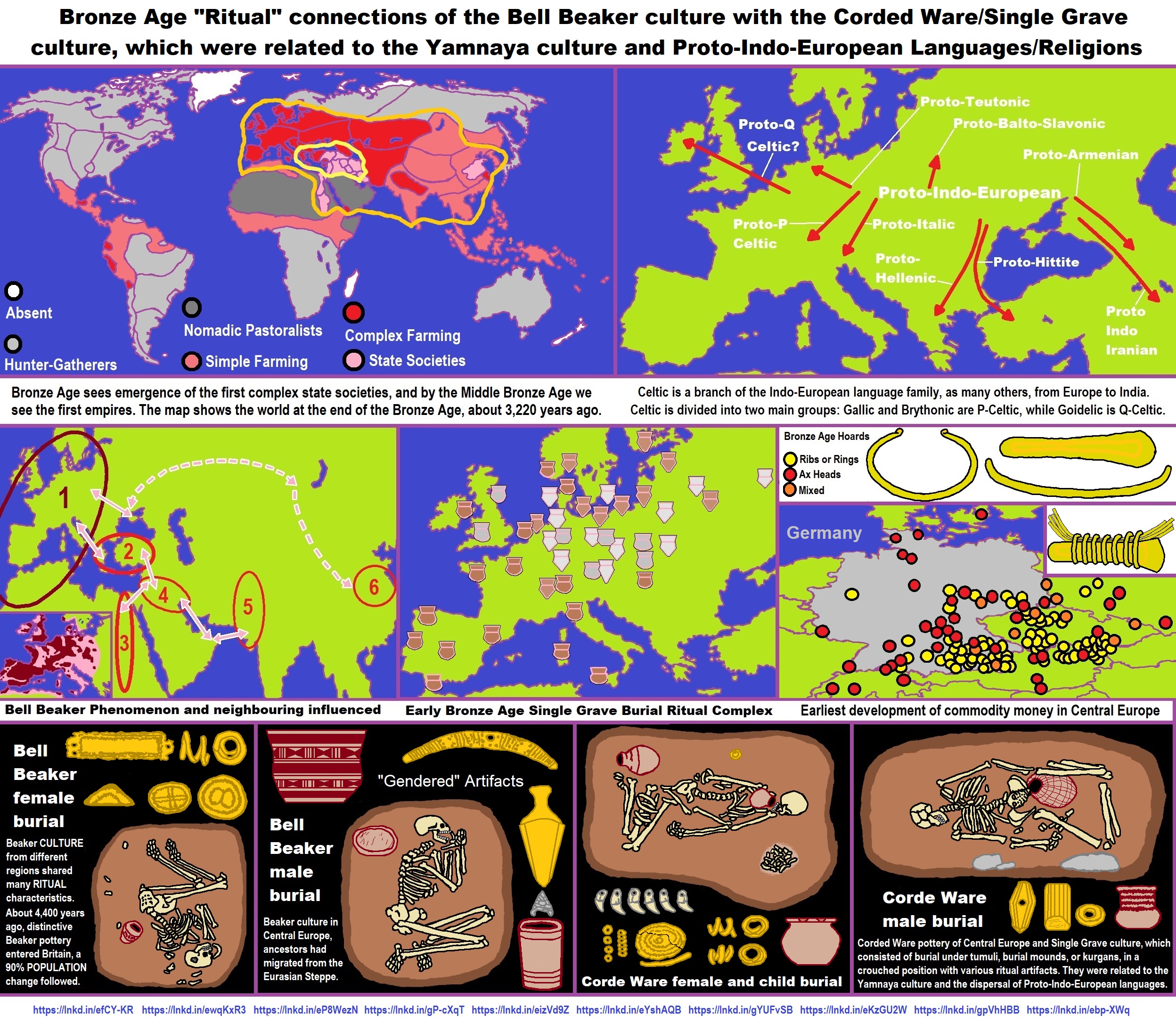

Horse burial: ref

Horse worship?

“Horse worship is a spiritual practice with archaeological evidence of its existence during the Iron Age and, in some places, as far back as the Bronze Age. The horse was seen as divine, as a sacred animal associated with a particular deity, or as a totem animal impersonating the king or warrior. Horse cults and horse sacrifice were originally a feature of Eurasian nomad cultures. While horse worship has been almost exclusively associated with Indo-European culture, by the Early Middle Ages it was also adopted by Turkic peoples. Horse worship still exists today in various regions of South Asia.” ref

Bronze Age

“The history of horse domestication is still a debated topic. The most widely accepted theory is that the horse was domesticated somewhere in the western Eurasian steppes. Various archaeological cultures including the Botai in Kazakhstan and Dereivka in Ukraine are proposed as possible candidates. However, widespread use of horses on the steppes is only noted from the late part of the third millennium BCE.” ref

Germanic

“Tacitus (Germania) mentions the use of white horses for divination by the Germanic tribes:

But to this nation it is peculiar, to learn presages and admonitions divine from horses also. These are nourished by the State in the same sacred woods and groves, all milk-white and employed in no earthly labor. These yoked in the holy chariot, are accompanied by the Priest and the King, or the Chief of the Community, who both carefully observed his actions and neighing. Nor in any sort of augury is more faith and assurance reposed, not by the populace only, but even by the nobles, even by the Priests. These account themselves the ministers of the Gods, and the horses privy to his will.” ref

India

“In India, horse worship in the form of worship of Hayagriva dates back to 2000 BCE, when the Indo-Aryan people started to migrate into the Indus valley. The Indo-Aryans worshipped the horse for its speed, strength, and intelligence. To this day, the worship of Hayagriva exists among the followers of Hinduism.” ref

Iron Age

“The Uffington White Horse in the United Kingdom, is dated to the Iron Age (800 BCE–CE 100) or the late Bronze Age (1000–700 BCE) in Britain; deposits of fine silt removed from the horse’s ‘beak’ were scientifically dated to the Late Bronze Age. The French archaeologist Patrice Méniel has demonstrated, based on examination of animal bones from many archaeological sites, a lack of hippophagy (horse eating) in ritual centers and burial sites in Gaul, although there is some evidence for hippophagy from earlier settlement sites in the same region. Horse oracles are also attested in later times (see Arkona below).” ref

“There is some reason to believe that Poseidon, like other water gods, was originally conceived under the form of a horse. In Greek art, Poseidon rides a chariot that was pulled by a hippocampus or by horses that could ride on the sea, and sailors sometimes drowned horses as a sacrifice to Poseidon to ensure a safe voyage. In the cave of Phigalia Demeter was, according to popular tradition, represented with the head and mane of a horse, possibly a relic of the time when a non-specialized corn-spirit bore this form. Her priests were called Poloi (Greek for “colts”) in Laconia.” ref

“This seems related to the archaic myth by which Poseidon once pursued Demeter; She spurned his advances, turning herself into a mare so that she could hide in a herd of horses; he saw through the deception and became a stallion and captured her. Their child was a horse, Arion, which was capable of human speech. This bears some resemblance to the Norse mythology reference to the gender-changing Loki having turned himself into a mare and given birth to Sleipnir, “the greatest of all horses.” ref

“In northern China, the Nanzhuangtou culture on the middle Yellow River around Hebei (c. 8500–7700 BCE) had grinding tools. The Xinglongwa culture in eastern Inner Mongolia (c. 6200–5400 BCE) ate millet, possibly from agriculture. The Dadiwan culture along the upper Yellow River (c. 5800–5400 BC) also ate millet. By the Yangshao culture (c. 5000–3000 BCE), the peoples of the Yellow River were growing millet extensively, along with some barley, rice, and vegetables; wove hemp and silk, which indicates some form of sericulture; but may have been limited to migratory slash and burn farming methods. The Longshan culture (c. 3000–2000 BCE) displays more advanced sericulture and definite cities.” ref

“In southern China, the Pengtoushan culture on the Yangtze River (c. 7500–6100 BCE) has left rice farming tools at some locations, though not at the type site. The Hemudu culture around Hangzhou Bay south of the Yangtze (c. 5000–4500 BCE) certainly cultivated rice. The various people (such as hundred viet tribal union) who succeeded in these areas were later conquered and culturally assimilated by the northern Chinese dynasties during the historical period.” ref

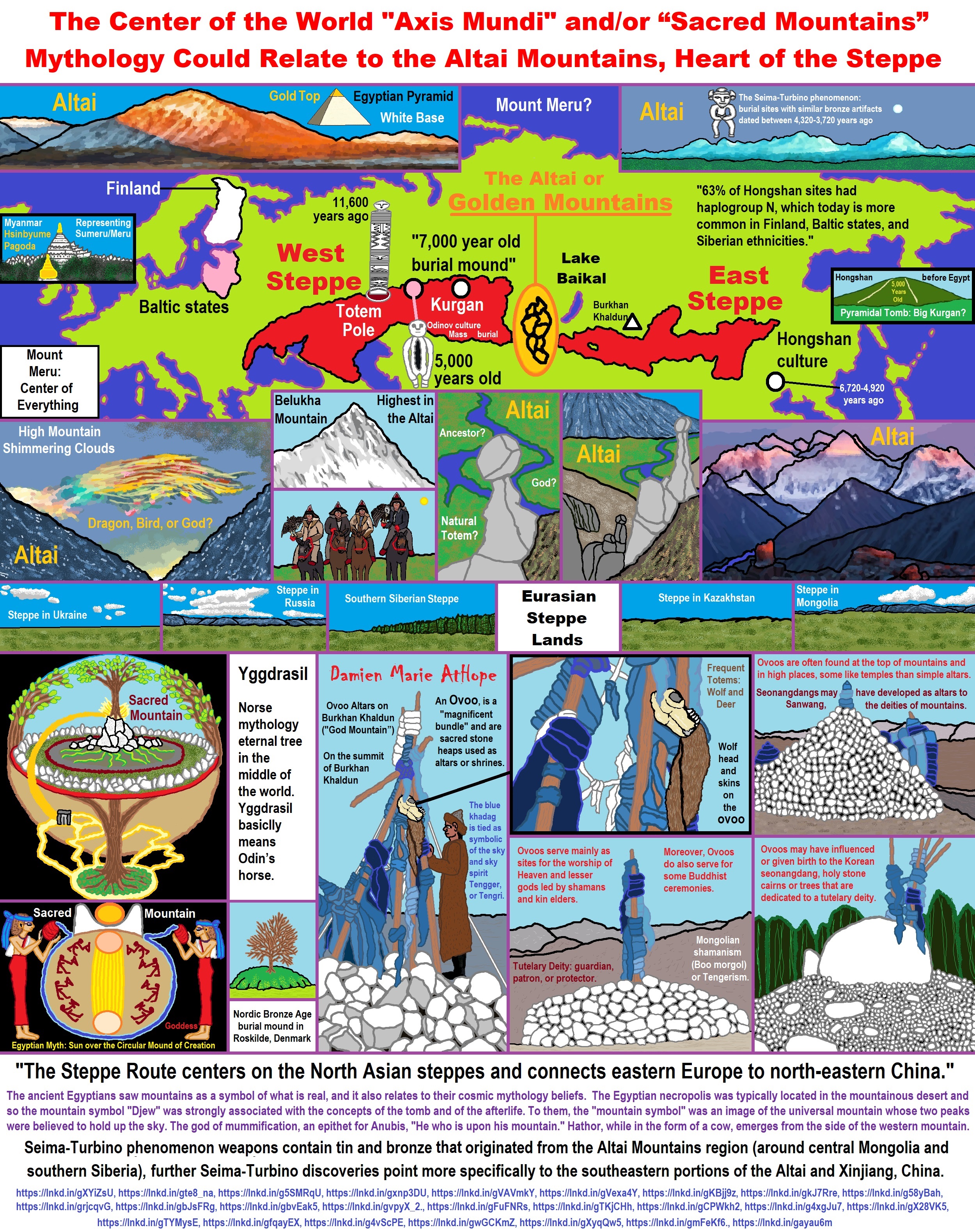

Inner Asia Mountain Corridor

“The Inner Asia Mountain Corridor (IAMC) was an ancient exchange route ranging from the Altai Mountains in Siberia to the Hindu Kush (present-day Afghanistan and northern Pakistan), which took shape in the 3rd millennium BCE. The expansion of the Indo-European Andronovo culture towards the Bactria-Margiana Culture in the second millennium BCE took place along the IAMC, giving way to the Indo-Aryan migration into South Asia.” ref

“By the fourth millennium BCE, or 6,022-5,022 years ago, a mobile pastoralist culture emerged at the Eurasian steppes. From the Pontic–Caspian steppe (present-day Ukraine and Russia), the Indo-European Yamna culture spread westwards toward the Great Hungarian Plain; and north-west it developed into the Corded Ware culture. Expanding eastward, Corded Ware eventually developed into the Sintashta culture, which further developed into the Andronovo culture. According to Narasimhan et al. (2018), the Andronovo-culture extended southwards via the IAMC, reaching into the Bactria-Margiana Culture, from where Indo-European language and culture reached South Asia.” ref

Eurasian Steppe Corridor

“The Steppe Route was an ancient overland route through the Eurasian Steppe that was an active precursor of the Silk Road. Silk and horses were traded as key commodities; secondary trade included furs, weapons, musical instruments, precious stones (turquoise, lapis lazuli, agate, nephrite), and jewels. This route extended for approximately 10,000 km (6,200 mi). Trans-Eurasian trade through the Steppe Route precedes the conventional date for the origins of the Silk Road by at least two millennia.” ref

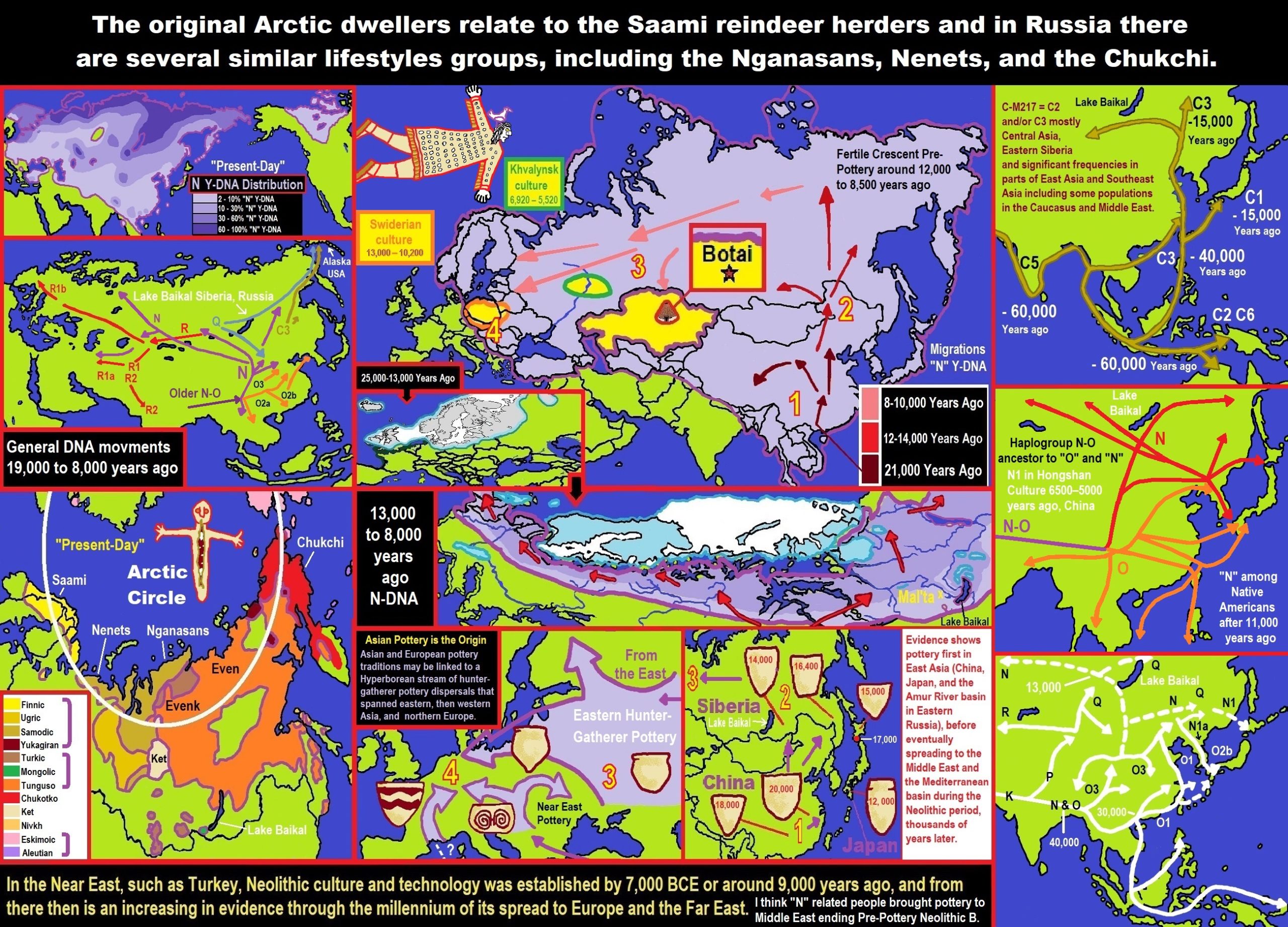

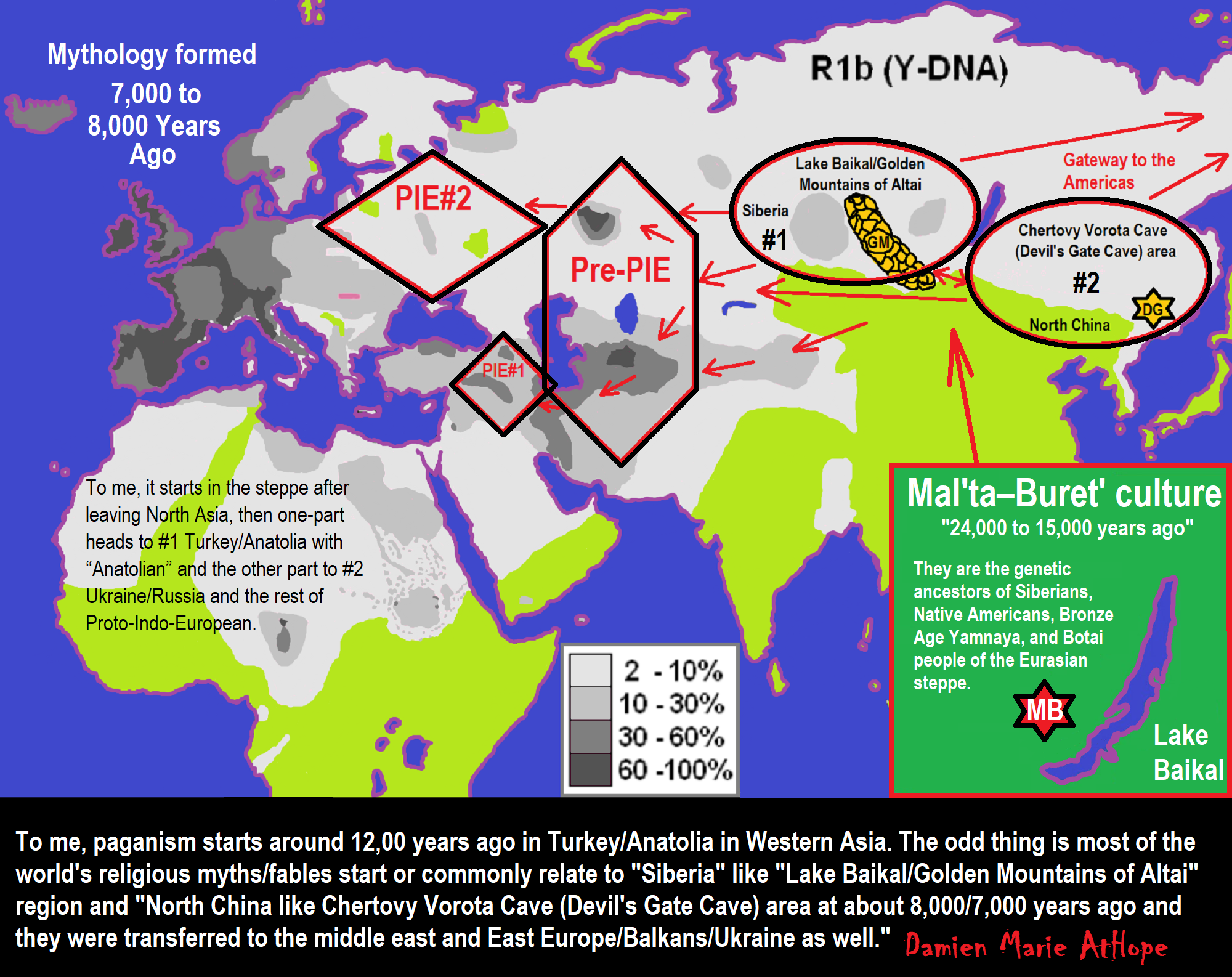

Mal’ta–Buret’ culture of Siberia and Basal Haplogroup R* or R-M207

“The Mal’ta–Buret‘ culture is an archaeological culture of the Upper Paleolithic (around 24,000 to 15,000 years ago) on the upper Angara River in the area west of Lake Baikal in the Irkutsk Oblast, Siberia, Russian Federation. The type sites are named for the villages of Mal’ta, Usolsky District and Buret’, Bokhansky District (both in Irkutsk Oblast).” ref

“The “Mal’ta Cluster” is composed of three individuals from the Glacial Maximum 24,000-17,000 years ago from the Lake Baikal region of Siberia.” ref

“MA-1 is the abbreviation of the male child remains found near Mal’ta dated to 24,000 years ago, who belonged to a population related to the genetic ancestors of Siberians, American Indians, and Bronze Age Yamnaya people of the Eurasian steppe. In particular, modern-day Native Americans, Kets, Mansi, Nganasans, and Yukaghirs were found to be harbor a lot of ancestries related to MA-1.” ref

Haplogroup R possible time of origin about 27,000 years in Central Asia, South Asia, or Siberia:

- Mal’ta–Buret’ culture (24,000-15,000 years ago)

- Afontova Gora culture (21,000-12,000 years ago)

- Trialetian culture (16,000–8000 years ago)

- Samara culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Khvalynsk culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Afanasievo culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Yamna/Yamnaya Culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Andronovo culture (4,000–2,900 years ago) ref

“The areas were people showed red hair matches at 1% and Germanic R1b S21 at 1-5%. But it didn’t explain the Finnish I1 subclades came before the bronze age over 4,022 years ago. This also means Finnish I1 in Sweden and Norway were very old and pre bronze age and pre Germanic. Probably, also means Scandinavian I1 arrived before Corded ware culture because of another groups of I1 subclades in continental Europe.” ref

“This also means continental (mainly central) European I1a1 M227, I1a3 Z58, I1a4 Z63, and I1b Z131 own another origin and I1 M253 line that goes back over 11,000 years. I1 M253 is a very old haplogroup, datable 15,000-20,000ybp in central Europe.” ref

“A 2014 study in Hungary uncovered remains of nine individuals from the Linear Pottery culture, one of whom was found to have carried the M253 SNP which defines Haplogroup I1. It is abbreviated as LBK (from German: Linearbandkeramik), and is also known as the Linear Band Ware, Linear Ware, Linear Ceramics, or Incised Ware culture, and falls within the Danubian I culture of V. Gordon Childe. This culture is thought to have been present between 6,500 to 7,500 years ago.” ref

“The densest evidence for the culture is on the middle Danube, the upper and middle Elbe, and the upper and middle Rhine. It represents a major event in the initial spread of agriculture in Europe. The pottery after which it was named consists of simple cups, bowls, vases, and jugs, without handles, but in a later phase with lugs or pierced lugs, bases, and necks.” ref

“Important sites include Nitra in Slovakia; Bylany in the Czech Republic; Langweiler and Zwenkau in Germany; Brunn am Gebirge in Austria; Elsloo, Sittard, Köln-Lindenthal, Aldenhoven, Flomborn, and Rixheim on the Rhine; Lautereck and Hienheim on the upper Danube; and Rössen and Sonderhausen on the middle Elbe.” ref

“Excavations at Oslonki in Poland revealed a large, fortified settlement (dating to 4300 BCE or 6,322 years ago, i. e., Late LBK), covering an area of 4,000 m². Nearly 30 trapezoidal longhouses and over 80 graves make it one of the richest such settlements in archaeological finds from all of central Europe. The rectangular longhouses were between 7 and 45 meters long and between 5 and 7 meters wide. They were built of massive timber posts chinked with wattle and daub mortar.” ref

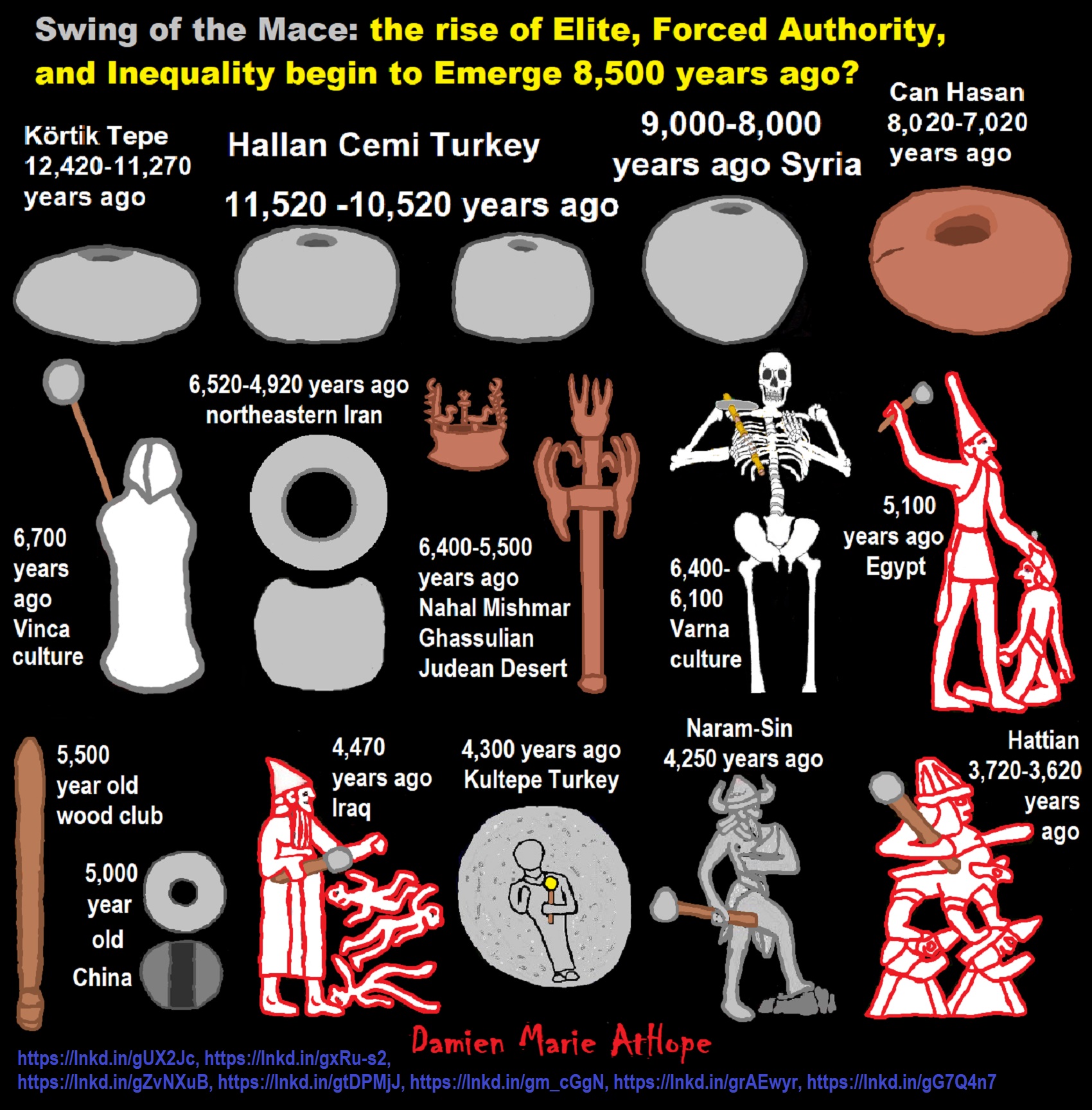

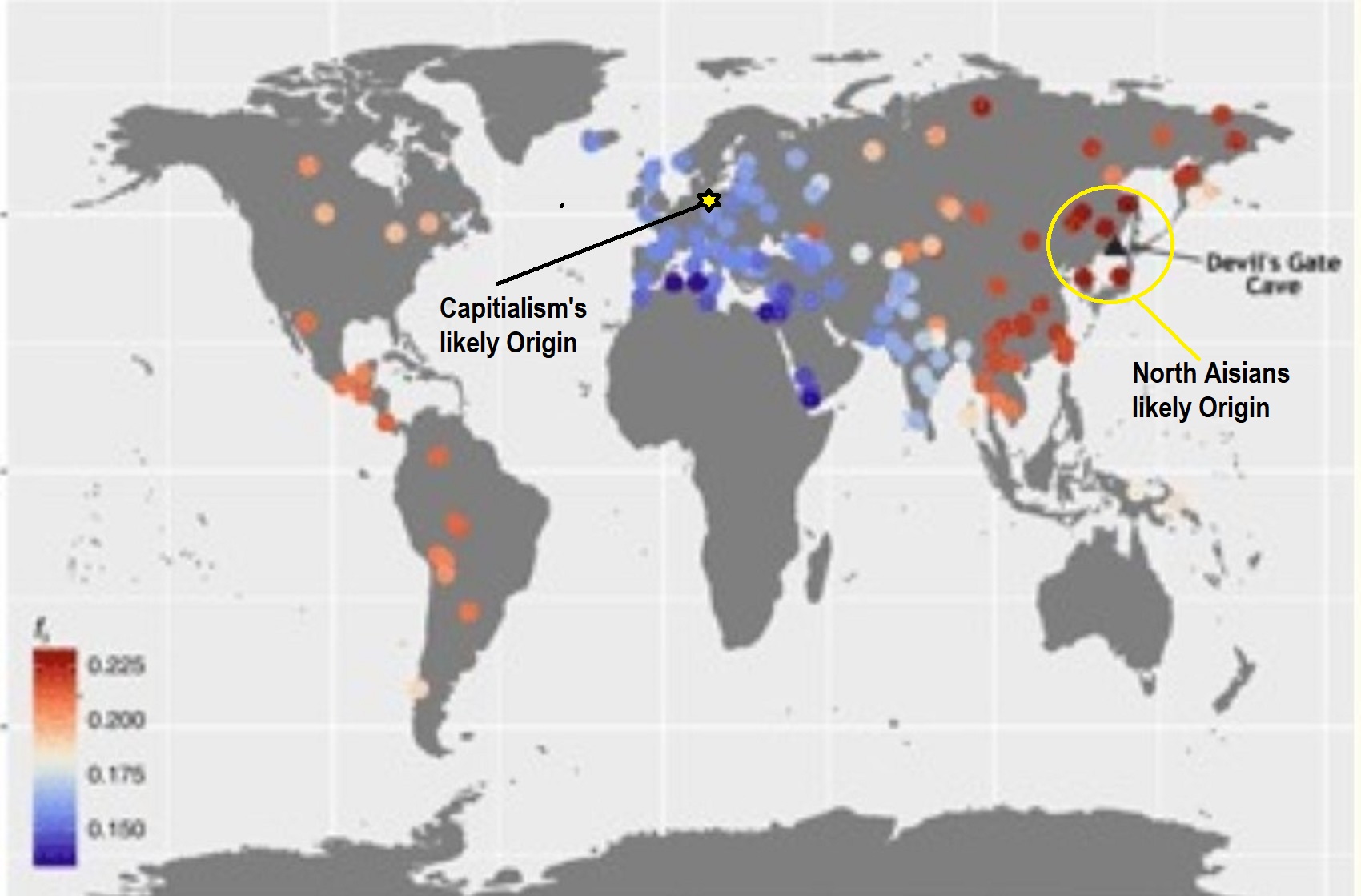

To me, in a big picture-related way, I surmise, likely, almost all clan or warrior “cult” talk, relates back to North Asia. That includes the Americas as well all people calling themselves or their clan/tribe/group “warriors”, relates back to North Aisa around 7,000 years ago.

“A warrior is a person specializing in combat or warfare as an institutionalized or professionalized career, especially within the context of a tribal or clan-based warrior culture society that recognizes a separate warrior aristocracies, class, or caste.” ref

“Warriors seem to have been present in the earliest pre-state societies. Most of the basic weapons used by warriors appeared before the rise of most hierarchical systems. Bows and arrows, clubs, spears, swords, and other edged weapons were in widespread use. However, with the new findings of metallurgy, the aforementioned weapons had grown in effectiveness.” ref

“When the first hierarchical systems evolved 5000 years ago, the gap between the rulers and the ruled had increased. Making war to extend the outreach of their territories, rulers often forced men from lower orders of society into the military role. This had been the first use of professional soldiers —a distinct difference from the warrior communities.” ref

“The warrior ethic in many societies later became the preserve of the ruling class. Egyptian pharaohs would depict themselves in war chariots, shooting at enemies, or smashing others with clubs. Fighting was considered a prestigious activity, but only when associated with status and power. European mounted knights would often feel contempt for the foot soldiers recruited from lower classes. In Mesoamerican societies of pre-Columbian America, the elite aristocratic soldiers remained separated from the lower classes of stone-throwers. The samurai were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of Japan from the 12th to the late 19th century.” ref